User login

Patients can safely receive less FVIII, study suggests

ORLANDO—It may be possible for hemophilia patients to receive less factor VIII (FVIII) without increasing their risk of bleeding, according to a study presented at the World Federation of Hemophilia 2016 World Congress.

The study1 showed that hemophilia A patients who received prophylactic FVIII from the home infusion provider Option Care received 6 fewer units of FVIII per week than patients receiving prophylactic FVIII from specialty pharmacies.

This translated to a cost savings of more than $20,000 per patient each year.

The home infusion patients also had a lower annual bleed rate (ABR) than what is typically observed with intensive prophylaxis protocols in hemophilia, according to previous studies.

“By working with prescribers to closely monitor bleeds and collaborate on clinically appropriate optimization of treatment dose, Option Care’s utilization of factor VIII is less than the average with excellent outcomes,” said Joan Couden, RN, national program director for Option Care’s Bleeding Disorders Program.

“Our findings show we can save payers, including Medicare, Medicaid, and managed care insurers, significant costs without negatively impacting annual bleed rates.”

For this study, Couden and her colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis using dispensing data records from Option Care spanning the period from July 2015 through December 2015. The team compared these data to aggregate specialty pharmacy records from November 2013 through March 2014, which were analyzed in a previous study.2

In both data sets, patients receiving any FVIII product for prophylactic therapy were included. Patients being treated episodically or for immune tolerance induction were excluded, as were patients with extremely abnormal weights (40% below the 5th percentile or 40% above the 95th percentile based on weight-for-age charts from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

The researchers calculated a patient’s weekly dose of FVIII by multiplying the prescribed infusion dose by the dose frequency and dividing the product by the patient’s weight. Patients with an overall mean weekly dose greater than 2 standard deviations from the mean were excluded.

There were 77 home infusion patients and 520 specialty pharmacy patients.

The home infusion patients had a mean FVIII dose of 102 units/kg/week, compared to a mean of 108 units/kg/week for the specialty pharmacy patients.

This difference translates to savings of $21,166 per patient per year among the home infusion patients.

Couden and her colleagues could not compare the ABR between the 2 data sets because the ABR was not measured in the specialty pharmacy patients. However, they said the ABR in the home infusion patients was favorable when compared to ABRs in published studies.

The mean ABR for the home infusion patients was 1.70. And, according to a recent review of research on hemophilia treatment strategies, mean ABRs range from 2 to 5 for intensive treatment protocols.3![]()

ORLANDO—It may be possible for hemophilia patients to receive less factor VIII (FVIII) without increasing their risk of bleeding, according to a study presented at the World Federation of Hemophilia 2016 World Congress.

The study1 showed that hemophilia A patients who received prophylactic FVIII from the home infusion provider Option Care received 6 fewer units of FVIII per week than patients receiving prophylactic FVIII from specialty pharmacies.

This translated to a cost savings of more than $20,000 per patient each year.

The home infusion patients also had a lower annual bleed rate (ABR) than what is typically observed with intensive prophylaxis protocols in hemophilia, according to previous studies.

“By working with prescribers to closely monitor bleeds and collaborate on clinically appropriate optimization of treatment dose, Option Care’s utilization of factor VIII is less than the average with excellent outcomes,” said Joan Couden, RN, national program director for Option Care’s Bleeding Disorders Program.

“Our findings show we can save payers, including Medicare, Medicaid, and managed care insurers, significant costs without negatively impacting annual bleed rates.”

For this study, Couden and her colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis using dispensing data records from Option Care spanning the period from July 2015 through December 2015. The team compared these data to aggregate specialty pharmacy records from November 2013 through March 2014, which were analyzed in a previous study.2

In both data sets, patients receiving any FVIII product for prophylactic therapy were included. Patients being treated episodically or for immune tolerance induction were excluded, as were patients with extremely abnormal weights (40% below the 5th percentile or 40% above the 95th percentile based on weight-for-age charts from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

The researchers calculated a patient’s weekly dose of FVIII by multiplying the prescribed infusion dose by the dose frequency and dividing the product by the patient’s weight. Patients with an overall mean weekly dose greater than 2 standard deviations from the mean were excluded.

There were 77 home infusion patients and 520 specialty pharmacy patients.

The home infusion patients had a mean FVIII dose of 102 units/kg/week, compared to a mean of 108 units/kg/week for the specialty pharmacy patients.

This difference translates to savings of $21,166 per patient per year among the home infusion patients.

Couden and her colleagues could not compare the ABR between the 2 data sets because the ABR was not measured in the specialty pharmacy patients. However, they said the ABR in the home infusion patients was favorable when compared to ABRs in published studies.

The mean ABR for the home infusion patients was 1.70. And, according to a recent review of research on hemophilia treatment strategies, mean ABRs range from 2 to 5 for intensive treatment protocols.3![]()

ORLANDO—It may be possible for hemophilia patients to receive less factor VIII (FVIII) without increasing their risk of bleeding, according to a study presented at the World Federation of Hemophilia 2016 World Congress.

The study1 showed that hemophilia A patients who received prophylactic FVIII from the home infusion provider Option Care received 6 fewer units of FVIII per week than patients receiving prophylactic FVIII from specialty pharmacies.

This translated to a cost savings of more than $20,000 per patient each year.

The home infusion patients also had a lower annual bleed rate (ABR) than what is typically observed with intensive prophylaxis protocols in hemophilia, according to previous studies.

“By working with prescribers to closely monitor bleeds and collaborate on clinically appropriate optimization of treatment dose, Option Care’s utilization of factor VIII is less than the average with excellent outcomes,” said Joan Couden, RN, national program director for Option Care’s Bleeding Disorders Program.

“Our findings show we can save payers, including Medicare, Medicaid, and managed care insurers, significant costs without negatively impacting annual bleed rates.”

For this study, Couden and her colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis using dispensing data records from Option Care spanning the period from July 2015 through December 2015. The team compared these data to aggregate specialty pharmacy records from November 2013 through March 2014, which were analyzed in a previous study.2

In both data sets, patients receiving any FVIII product for prophylactic therapy were included. Patients being treated episodically or for immune tolerance induction were excluded, as were patients with extremely abnormal weights (40% below the 5th percentile or 40% above the 95th percentile based on weight-for-age charts from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

The researchers calculated a patient’s weekly dose of FVIII by multiplying the prescribed infusion dose by the dose frequency and dividing the product by the patient’s weight. Patients with an overall mean weekly dose greater than 2 standard deviations from the mean were excluded.

There were 77 home infusion patients and 520 specialty pharmacy patients.

The home infusion patients had a mean FVIII dose of 102 units/kg/week, compared to a mean of 108 units/kg/week for the specialty pharmacy patients.

This difference translates to savings of $21,166 per patient per year among the home infusion patients.

Couden and her colleagues could not compare the ABR between the 2 data sets because the ABR was not measured in the specialty pharmacy patients. However, they said the ABR in the home infusion patients was favorable when compared to ABRs in published studies.

The mean ABR for the home infusion patients was 1.70. And, according to a recent review of research on hemophilia treatment strategies, mean ABRs range from 2 to 5 for intensive treatment protocols.3![]()

Therapy seems safe, effective in kids with hemophilia

Photo courtesy of Baxalta

ORLANDO—Results of a phase 3 study suggest the full-length recombinant factor VIII therapy Adynovate (BAX 855) can be safe and effective as twice-weekly prophylaxis and to control bleeding in children with hemophilia A.

None of the patients in this study developed inhibitory antibodies, and there were no product-related adverse events.

The median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) was 2.0, and nearly 40% of patients did not have any bleeding episodes.

These results were presented at the World Federation of Hemophilia 2016 World Congress.* The study was funded by Baxalta, now part of Shire.

The study enrolled previously treated children younger than 12 years of age with no history of factor VIII inhibitors. The patients received twice-weekly prophylaxis with Adynovate (50 ± 10 IU/kg) for at least 6 months or 50 exposure days, whichever occurred last.

There were 66 evaluable patients with a median age of 6 (range, 1-11). Overall, 4,467,796 IU of Adynovate were infused. The mean number of exposure days was 53.98 per patient.

Safety

There was no indication of persistent binding antibodies against factor VIII, and none of the patients developed antibodies to host cell (Chinese hamster ovary) proteins.

There were 156 adverse events in 43 patients (65.2%), but none were considered related to Adynovate.

There were 4 unrelated serious adverse events in 3 patients—febrile neutropenia, pancytopenia, acute gastritis, and abdominal pain.

Efficacy

Patients received a median dose of 51.3 IU/kg per prophylactic infusion at a median frequency of 1.9 infusions per week.

Ninety-one percent of patients did not require dose adjustments. Reasons for dose adjustment included factor VIII trough levels less than 1%, increased risk of bleeding, and bleeding episodes.

Thirty-eight percent of patients did not experience bleeding events, 73% did not experience hemarthroses, and 67% did not experience spontaneous bleeding events.

The mean ABR was 3.0, and the median was 2.0. The mean joint ABR was 1.1, and the median was 0. The mean spontaneous ABR was 1.2, and the median was 0. The mean interval between bleeding episodes was 2.4 months.

There were a total of 70 bleeding episodes in 34 patients. All of these episodes were minor or moderate. Ninety-one percent of treated bleeding events were treated with 1 or 2 infusions. And 90% of bleeding events received treatment ratings of “excellent” or “good.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of Baxalta

ORLANDO—Results of a phase 3 study suggest the full-length recombinant factor VIII therapy Adynovate (BAX 855) can be safe and effective as twice-weekly prophylaxis and to control bleeding in children with hemophilia A.

None of the patients in this study developed inhibitory antibodies, and there were no product-related adverse events.

The median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) was 2.0, and nearly 40% of patients did not have any bleeding episodes.

These results were presented at the World Federation of Hemophilia 2016 World Congress.* The study was funded by Baxalta, now part of Shire.

The study enrolled previously treated children younger than 12 years of age with no history of factor VIII inhibitors. The patients received twice-weekly prophylaxis with Adynovate (50 ± 10 IU/kg) for at least 6 months or 50 exposure days, whichever occurred last.

There were 66 evaluable patients with a median age of 6 (range, 1-11). Overall, 4,467,796 IU of Adynovate were infused. The mean number of exposure days was 53.98 per patient.

Safety

There was no indication of persistent binding antibodies against factor VIII, and none of the patients developed antibodies to host cell (Chinese hamster ovary) proteins.

There were 156 adverse events in 43 patients (65.2%), but none were considered related to Adynovate.

There were 4 unrelated serious adverse events in 3 patients—febrile neutropenia, pancytopenia, acute gastritis, and abdominal pain.

Efficacy

Patients received a median dose of 51.3 IU/kg per prophylactic infusion at a median frequency of 1.9 infusions per week.

Ninety-one percent of patients did not require dose adjustments. Reasons for dose adjustment included factor VIII trough levels less than 1%, increased risk of bleeding, and bleeding episodes.

Thirty-eight percent of patients did not experience bleeding events, 73% did not experience hemarthroses, and 67% did not experience spontaneous bleeding events.

The mean ABR was 3.0, and the median was 2.0. The mean joint ABR was 1.1, and the median was 0. The mean spontaneous ABR was 1.2, and the median was 0. The mean interval between bleeding episodes was 2.4 months.

There were a total of 70 bleeding episodes in 34 patients. All of these episodes were minor or moderate. Ninety-one percent of treated bleeding events were treated with 1 or 2 infusions. And 90% of bleeding events received treatment ratings of “excellent” or “good.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of Baxalta

ORLANDO—Results of a phase 3 study suggest the full-length recombinant factor VIII therapy Adynovate (BAX 855) can be safe and effective as twice-weekly prophylaxis and to control bleeding in children with hemophilia A.

None of the patients in this study developed inhibitory antibodies, and there were no product-related adverse events.

The median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) was 2.0, and nearly 40% of patients did not have any bleeding episodes.

These results were presented at the World Federation of Hemophilia 2016 World Congress.* The study was funded by Baxalta, now part of Shire.

The study enrolled previously treated children younger than 12 years of age with no history of factor VIII inhibitors. The patients received twice-weekly prophylaxis with Adynovate (50 ± 10 IU/kg) for at least 6 months or 50 exposure days, whichever occurred last.

There were 66 evaluable patients with a median age of 6 (range, 1-11). Overall, 4,467,796 IU of Adynovate were infused. The mean number of exposure days was 53.98 per patient.

Safety

There was no indication of persistent binding antibodies against factor VIII, and none of the patients developed antibodies to host cell (Chinese hamster ovary) proteins.

There were 156 adverse events in 43 patients (65.2%), but none were considered related to Adynovate.

There were 4 unrelated serious adverse events in 3 patients—febrile neutropenia, pancytopenia, acute gastritis, and abdominal pain.

Efficacy

Patients received a median dose of 51.3 IU/kg per prophylactic infusion at a median frequency of 1.9 infusions per week.

Ninety-one percent of patients did not require dose adjustments. Reasons for dose adjustment included factor VIII trough levels less than 1%, increased risk of bleeding, and bleeding episodes.

Thirty-eight percent of patients did not experience bleeding events, 73% did not experience hemarthroses, and 67% did not experience spontaneous bleeding events.

The mean ABR was 3.0, and the median was 2.0. The mean joint ABR was 1.1, and the median was 0. The mean spontaneous ABR was 1.2, and the median was 0. The mean interval between bleeding episodes was 2.4 months.

There were a total of 70 bleeding episodes in 34 patients. All of these episodes were minor or moderate. Ninety-one percent of treated bleeding events were treated with 1 or 2 infusions. And 90% of bleeding events received treatment ratings of “excellent” or “good.” ![]()

Team identifies mutations contributing to APL

Image from the Armed Forces

Institute of Pathology

Researchers have identified genetic mutations that contribute to the onset of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), according to a paper published in Leukemia.

The team analyzed patient samples to identify somatic mutations that cooperate with the PML-RARA fusion gene in the pathogenesis of APL.

They performed whole-exome and targeted sequencing on 242 samples from APL patients, 165 who were newly diagnosed and 77 who had relapsed.

Samples from patients with newly diagnosed APL had recurrent mutations in FLT3, WT1, NRAS, and KRAS but rarely had mutations in other genes commonly mutated in myeloid leukemia.

The newly diagnosed samples also had loss-of-function mutations in ARID1A and ARID1B (members of a chromatin remodeling complex), which had not previously been identified in APL.

The researchers said the ARID1A and ARID1B mutations indicate dysregulation of epigenetic machinery in APL, and the mutations provide a subset of previously uncharacterized genes in leukemogenesis.

The team also found that knocking down ARID1B in the APL cell line NB4 resulted in large-scale activation of gene expression and reduced in vitro differentiation potential.

In the relapsed APL samples, the researchers discovered a set of mutations that were not observed in the newly diagnosed samples. Most prominently, mutations in RARA and PML were found to be exclusive to relapsed samples.

The team also found these mutations were largely acquired in 2 distinct patient groups—those treated at initial diagnosis with all-trans retinoic acid and those treated with arsenic trioxide.

“Our comprehensive study on the mutational landscape in a large cohort of primary and relapsed APL cases has enabled us to establish the molecular roadmap for APL, which is distinct from other subtypes of [acute myeloid leukemia],” said study author H. Phillip Koeffler, MD, of the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore.

“With an enhanced knowledge of the disease biology, we will be conducting further research to uncover the consequences of the novel mutations discovered, with an eventual goal of developing improved and targeted therapeutics.” ![]()

Image from the Armed Forces

Institute of Pathology

Researchers have identified genetic mutations that contribute to the onset of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), according to a paper published in Leukemia.

The team analyzed patient samples to identify somatic mutations that cooperate with the PML-RARA fusion gene in the pathogenesis of APL.

They performed whole-exome and targeted sequencing on 242 samples from APL patients, 165 who were newly diagnosed and 77 who had relapsed.

Samples from patients with newly diagnosed APL had recurrent mutations in FLT3, WT1, NRAS, and KRAS but rarely had mutations in other genes commonly mutated in myeloid leukemia.

The newly diagnosed samples also had loss-of-function mutations in ARID1A and ARID1B (members of a chromatin remodeling complex), which had not previously been identified in APL.

The researchers said the ARID1A and ARID1B mutations indicate dysregulation of epigenetic machinery in APL, and the mutations provide a subset of previously uncharacterized genes in leukemogenesis.

The team also found that knocking down ARID1B in the APL cell line NB4 resulted in large-scale activation of gene expression and reduced in vitro differentiation potential.

In the relapsed APL samples, the researchers discovered a set of mutations that were not observed in the newly diagnosed samples. Most prominently, mutations in RARA and PML were found to be exclusive to relapsed samples.

The team also found these mutations were largely acquired in 2 distinct patient groups—those treated at initial diagnosis with all-trans retinoic acid and those treated with arsenic trioxide.

“Our comprehensive study on the mutational landscape in a large cohort of primary and relapsed APL cases has enabled us to establish the molecular roadmap for APL, which is distinct from other subtypes of [acute myeloid leukemia],” said study author H. Phillip Koeffler, MD, of the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore.

“With an enhanced knowledge of the disease biology, we will be conducting further research to uncover the consequences of the novel mutations discovered, with an eventual goal of developing improved and targeted therapeutics.” ![]()

Image from the Armed Forces

Institute of Pathology

Researchers have identified genetic mutations that contribute to the onset of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), according to a paper published in Leukemia.

The team analyzed patient samples to identify somatic mutations that cooperate with the PML-RARA fusion gene in the pathogenesis of APL.

They performed whole-exome and targeted sequencing on 242 samples from APL patients, 165 who were newly diagnosed and 77 who had relapsed.

Samples from patients with newly diagnosed APL had recurrent mutations in FLT3, WT1, NRAS, and KRAS but rarely had mutations in other genes commonly mutated in myeloid leukemia.

The newly diagnosed samples also had loss-of-function mutations in ARID1A and ARID1B (members of a chromatin remodeling complex), which had not previously been identified in APL.

The researchers said the ARID1A and ARID1B mutations indicate dysregulation of epigenetic machinery in APL, and the mutations provide a subset of previously uncharacterized genes in leukemogenesis.

The team also found that knocking down ARID1B in the APL cell line NB4 resulted in large-scale activation of gene expression and reduced in vitro differentiation potential.

In the relapsed APL samples, the researchers discovered a set of mutations that were not observed in the newly diagnosed samples. Most prominently, mutations in RARA and PML were found to be exclusive to relapsed samples.

The team also found these mutations were largely acquired in 2 distinct patient groups—those treated at initial diagnosis with all-trans retinoic acid and those treated with arsenic trioxide.

“Our comprehensive study on the mutational landscape in a large cohort of primary and relapsed APL cases has enabled us to establish the molecular roadmap for APL, which is distinct from other subtypes of [acute myeloid leukemia],” said study author H. Phillip Koeffler, MD, of the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore.

“With an enhanced knowledge of the disease biology, we will be conducting further research to uncover the consequences of the novel mutations discovered, with an eventual goal of developing improved and targeted therapeutics.” ![]()

Long-term outcomes with CBT better than with MUD

Photo courtesy of NHS

A single-center study suggests that long-term outcomes may be better among patients who receive a double cord blood transplant (CBT) than those who receive a peripheral blood stem cell transplant from a matched, unrelated donor (MUD).

At 3-years post-transplant, the incidence of chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) was significantly lower among the CBT recipients studied.

In addition, patients who received CBTs were less likely to be re-hospitalized and more likely to discontinue immunosuppressive therapy.

However, there was no significant difference in relapse, transplant-related mortality, or overall survival between CBT recipients and patients who received MUD transplants.

These results were published in Bone Marrow Transplantation.

“Historically, doctors have reserved cord blood for patients without a match,” said study author Jonathan Gutman, MD, of the University of Colorado Denver in Aurora, Colorado.

“A lot of centers reserved cord blood transplants for their worst cases, and so it got an early reputation for being less successful. It also costs a bit more; it takes cord blood cells a little longer to get going, and so patients need to be supported a little longer. However, when you look past the first 100 days—a point at which many centers stop collecting data—there is clear evidence that cord blood outperforms cells from matched, unrelated donors.”

To uncover such evidence, Dr Gutman and his colleagues analyzed adult patients with hematologic malignancies who underwent transplants at the University of Colorado Denver from 2009 to 2014. The team compared 51 consecutive patients receiving double CBT with 57 consecutive patients receiving MUD transplants.

At 3 years post-transplant, the overall rates of cGVHD were 68% following MUD and 32% following CBT (P=0.0017). The rates of severe cGVHD were 44% and 8%, respectively (P=0.0006).

CBT recipients had been off immunosuppression since a median of 268 days from transplant, while patients who received MUD transplants had not ceased immunosuppression to a degree that allowed researchers to determine the median (P<0.0001).

Late hospitalization was significantly reduced among CBT recipients, and there was a trend toward fewer late infections for these patients.

Excluding patients who died during the follow-up period, the relative risk of late infection episode on a per-infection level was 0.77 (P=0.10), and the relative risk of late hospitalization was 0.74 (P<0.001).

The 3-year relapse, transplant-related mortality, and overall survival rates were similar following CBT and MUD transplant.

The cumulative incidence of relapse was 22% for CBT and 24% for MUD (P=0.86). Transplant-related mortality was 25% for CBT and 24% for MUD (P=0.73). And overall survival was 54% for CBT and 52% for MUD (P=0.68).

Dr Gutman said that, due to these results, the University of Colorado Denver has chosen to use cord blood as the first choice for transplant cases where a matched, related donor is unavailable. ![]()

Photo courtesy of NHS

A single-center study suggests that long-term outcomes may be better among patients who receive a double cord blood transplant (CBT) than those who receive a peripheral blood stem cell transplant from a matched, unrelated donor (MUD).

At 3-years post-transplant, the incidence of chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) was significantly lower among the CBT recipients studied.

In addition, patients who received CBTs were less likely to be re-hospitalized and more likely to discontinue immunosuppressive therapy.

However, there was no significant difference in relapse, transplant-related mortality, or overall survival between CBT recipients and patients who received MUD transplants.

These results were published in Bone Marrow Transplantation.

“Historically, doctors have reserved cord blood for patients without a match,” said study author Jonathan Gutman, MD, of the University of Colorado Denver in Aurora, Colorado.

“A lot of centers reserved cord blood transplants for their worst cases, and so it got an early reputation for being less successful. It also costs a bit more; it takes cord blood cells a little longer to get going, and so patients need to be supported a little longer. However, when you look past the first 100 days—a point at which many centers stop collecting data—there is clear evidence that cord blood outperforms cells from matched, unrelated donors.”

To uncover such evidence, Dr Gutman and his colleagues analyzed adult patients with hematologic malignancies who underwent transplants at the University of Colorado Denver from 2009 to 2014. The team compared 51 consecutive patients receiving double CBT with 57 consecutive patients receiving MUD transplants.

At 3 years post-transplant, the overall rates of cGVHD were 68% following MUD and 32% following CBT (P=0.0017). The rates of severe cGVHD were 44% and 8%, respectively (P=0.0006).

CBT recipients had been off immunosuppression since a median of 268 days from transplant, while patients who received MUD transplants had not ceased immunosuppression to a degree that allowed researchers to determine the median (P<0.0001).

Late hospitalization was significantly reduced among CBT recipients, and there was a trend toward fewer late infections for these patients.

Excluding patients who died during the follow-up period, the relative risk of late infection episode on a per-infection level was 0.77 (P=0.10), and the relative risk of late hospitalization was 0.74 (P<0.001).

The 3-year relapse, transplant-related mortality, and overall survival rates were similar following CBT and MUD transplant.

The cumulative incidence of relapse was 22% for CBT and 24% for MUD (P=0.86). Transplant-related mortality was 25% for CBT and 24% for MUD (P=0.73). And overall survival was 54% for CBT and 52% for MUD (P=0.68).

Dr Gutman said that, due to these results, the University of Colorado Denver has chosen to use cord blood as the first choice for transplant cases where a matched, related donor is unavailable. ![]()

Photo courtesy of NHS

A single-center study suggests that long-term outcomes may be better among patients who receive a double cord blood transplant (CBT) than those who receive a peripheral blood stem cell transplant from a matched, unrelated donor (MUD).

At 3-years post-transplant, the incidence of chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) was significantly lower among the CBT recipients studied.

In addition, patients who received CBTs were less likely to be re-hospitalized and more likely to discontinue immunosuppressive therapy.

However, there was no significant difference in relapse, transplant-related mortality, or overall survival between CBT recipients and patients who received MUD transplants.

These results were published in Bone Marrow Transplantation.

“Historically, doctors have reserved cord blood for patients without a match,” said study author Jonathan Gutman, MD, of the University of Colorado Denver in Aurora, Colorado.

“A lot of centers reserved cord blood transplants for their worst cases, and so it got an early reputation for being less successful. It also costs a bit more; it takes cord blood cells a little longer to get going, and so patients need to be supported a little longer. However, when you look past the first 100 days—a point at which many centers stop collecting data—there is clear evidence that cord blood outperforms cells from matched, unrelated donors.”

To uncover such evidence, Dr Gutman and his colleagues analyzed adult patients with hematologic malignancies who underwent transplants at the University of Colorado Denver from 2009 to 2014. The team compared 51 consecutive patients receiving double CBT with 57 consecutive patients receiving MUD transplants.

At 3 years post-transplant, the overall rates of cGVHD were 68% following MUD and 32% following CBT (P=0.0017). The rates of severe cGVHD were 44% and 8%, respectively (P=0.0006).

CBT recipients had been off immunosuppression since a median of 268 days from transplant, while patients who received MUD transplants had not ceased immunosuppression to a degree that allowed researchers to determine the median (P<0.0001).

Late hospitalization was significantly reduced among CBT recipients, and there was a trend toward fewer late infections for these patients.

Excluding patients who died during the follow-up period, the relative risk of late infection episode on a per-infection level was 0.77 (P=0.10), and the relative risk of late hospitalization was 0.74 (P<0.001).

The 3-year relapse, transplant-related mortality, and overall survival rates were similar following CBT and MUD transplant.

The cumulative incidence of relapse was 22% for CBT and 24% for MUD (P=0.86). Transplant-related mortality was 25% for CBT and 24% for MUD (P=0.73). And overall survival was 54% for CBT and 52% for MUD (P=0.68).

Dr Gutman said that, due to these results, the University of Colorado Denver has chosen to use cord blood as the first choice for transplant cases where a matched, related donor is unavailable. ![]()

To Cut or Not to Cut? Evaluating Surgical Criteria for Benign & Nondiagnostic Thyroid Nodules

A new-onset thyroid nodule, found on exam or incidentally on imaging, is a common presentation at primary care and specialist clinics. Palpable nodules are present in 4% to 7% of the population.1 However, more sensitive evaluation with thyroid ultrasound (US) suggests an incidence as high as 70%.2

According to the American Cancer Society, in 2015, there were approximately 62,450 new cases of thyroid cancer in the United States (with 2.5 times as many occurring in women as in men).3 In fact, thyroid cancer is the most rapidly increasing cancer in the United States—attributable in part to the increased use of thyroid US and incidental detection.3

The high prevalence of thyroid nodules makes appropriate evaluation and treatment crucial. This article, through a case study, explores the evaluation of a thyroid nodule and the recommendation for and against thyroidectomy.

Felicia, 49, presents to the endocrine clinic as a new patient with questions about multinodular goiter (MNG). She has been advised by ENT to have a left-sided dominant nodule surgically removed while under anesthesia during her upcoming chronic sinusitis surgery. Felicia would like to avoid thyroid surgery, if possible. Her most recent thyroid US, performed three months ago, showed a right lobe with multiple colloid nodules with inspissated colloid, the largest of which is 1.5 cm, and a 4-cm complex, solid, cystic nodule with inspissated colloid in the cystic spaces replacing the entire left thyroid lobe.

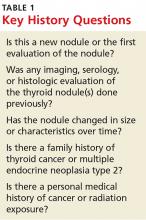

HistoryThe first step is establishing a history of the nodule(s) in question. Key questions are listed in Table 1. The onset and progression of a thyroid nodule must be determined; ideally, the provider should review any previous studies related to the thyroid gland. This will help determine if the nodule is new, if it has been evaluated in the past, and if it has changed significantly.

A thorough history can identify risk factors for malignancy, which include a personal history of cancer or radiation exposure, as well as a family history of thyroid cancer or malignant endocrine syndromes.

Felicia denies any family or personal medical history concerning for malignancy. She notes that she has two sisters with MNG. She denies any neck pain, compressive/obstructive symptoms, and hypo- or hyperthyroid symptoms.

She reports that she was found to have a goiter on exam and was subsequently diagnosed with MNG in 2008. Thyroid US showed a 2.3-cm complex, largely solid mass in the right mid-pole and a 3.3-cm largely cystic lesion in the left mid-pole. She was referred for right-sided fine-needle aspiration (FNA); results were consistent with benign colloid nodule. The left-sided nodule was not biopsied at that time, due to a largely cystic component.

Felicia underwent a follow-up US in 2011; it showed a 1.6-cm right mid-pole nodule with multiple nonspecific echogenic areas; a 1-cm benign-appearing nodule; and a 3.7-cm highly vascular heterogeneous mass with some colloid components with indeterminate component in the left lower and mid-pole. She reports that she did not follow up in 2011. Her next evaluation was the current thyroid US. She has never had FNA of the left-sided dominant nodule.

Continue for symptomatic vs asymptomatic thyroid nodules >>

Symptomatic vs Asymptomatic Thyroid NodulesEvaluation of a symptomatic thyroid nodule can help to determine the need for surgery, as well as assess the level of interference with a patient’s activities of daily living and the potential for functional abnormalities. However, both local neck and constitutional symptoms may be nonspecific and unrelated to the thyroid gland’s structure or function. Therefore, the provider should exercise caution in making recommendations based on reported symptoms alone.

Symptoms indicative of the need for surgical intervention include neck pain, increased neck pressure, foreign body sensation, dysphonia, dyspnea, and dysphagia. However, it is essential to determine if these symptoms are likely due to a thyroid nodule or if they can be attributed to a secondary cause (eg, postnasal drip, vocal cord dysfunction, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or esophageal stricture).

If the findings are inconsistent with the clinical picture, secondary evaluation is prudent to avoid an unnecessary procedure.

Physical ExamPalpation of a thyroid nodule is an unreliable indicator of risk for malignancy. Palpation alone does not allow for detection of all nodules, particularly smaller ones, and specific characteristics are not discernible. Imaging studies are required to accurately evaluate a thyroid nodule and determine the most appropriate course of action.

Palpation can be used to evaluate for a larger and/or fixed nodule, thyroid gland/nodule tenderness, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Physical exam can also assess for signs of hypo- or hyperthyroidism, including abnormal pulse rate or blood pressure, tremor, hypo- or hyperreflexia, and integumentary abnormalities (eg, hair loss, abnormal skin temperature, and nail changes).

Continue for serologic evaluation >>

Serologic Evaluation

If a thyroid nodule is suspected on exam or found on imaging, assessment of thyroid function, via thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) measurement, is the recommended first step. If TSH is elevated, further evaluation for hypothyroidism is recommended, with testing for free thyroxine (T4) and antithyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies.4 If TSH is suppressed, further evaluation with free T4 and assessment for underlying causes of hyperthyroidism are indicated, including work-up for toxic nodular goiter.

Routine monitoring of serum calcitonin level is not recommended. However, if there is suspicion for medullary thyroid cancer—based on either US findings or family history—serologic screening for abnormal calcitonin level may be indicated.4,5

Felicia’s lab results include a TSH of 1.30 µIU/mL (reference range, 0.30-3.00 µIU/mL). Based on this finding, what (if any) further serologic testing is recommended? None: With normal TSH and no concerning family or personal history, additional laboratory evaluation is not indicated.

Imaging a Thyroid Nodule

Thyroid US is the most sensitive imaging study for evaluating thyroid nodule characteristics. Thyroid uptake and scan is not indicated unless TSH is suppressed and evaluation for toxic nodular goiter is needed. Additional imaging studies, such as CT or MRI, are not recommended for thyroid nodule evaluation.

Based on the thyroid US, what characteristics of Felicia’s nodule are suggestive of a benign nodule? Of a malignant nodule? (See Table 2.)

FNA of the left-sided dominant nodule is indicated, based on the US findings of a partially solid component and size > 1 cm. Unfortunately, FNA is nondiagnostic, because it yielded cystic fluid only with scant follicular cells for evaluation.

Continue to now what? >>

Now What?

While FNA most definitively distinguishes between benign and malignant nodules, the test is limited. An indeterminate, or nondiagnostic, finding occurs in 10% to 15% of cases and is more likely in nodules with a large cystic component.1

Even a benign finding on FNA of a larger nodule should be viewed with caution, since aspiration is unlikely to pinpoint small insidious malignant cells nestled among a larger collection of benign tissue.3 In many situations, a patient receives FNA results and asks, “What should we do now?”

Nondiagnostic nodules

When FNA is indeterminate, the next step depends on the characteristics of the nodule. For a solid nodule, repeat FNA is recommended.4,5 For nodules with repeatedly nondiagnostic FNAs, the American Academy of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association recommend that a solid nodule be considered for surgical removal unless the nodule has “clearly favorable clinical and US features.”4,5

Surgical excision should be considered for cysts that recur, those that are larger (> 4 cm), and those that are repeatedly nondiagnostic on FNA. Personal and family history should be taken into account when nodules that are nondiagnostic on FNA demonstrate suspicious characteristics on US.6

An analysis by Renshaw determined that risk for malignancy in a nodule with a single nondiagnostic FNA was about 20%. For nodules that underwent repeat FNA, the risk was 0% for those that were again nondiagnostic. This significant difference led the author to conclude that “patients with two sequential nondiagnostic thyroid aspirates have a very low risk of malignancy.”7

Consider the time commitment, financial burden, and emotional cost for the patient of repeated evaluation with thyroid US and possibly FNA. In recurrent cases, the risks associated with surgery begin to be outweighed by the cost and burden of prolonged observation.

Benign nodules

With a biopsy-proven benign nodule, observation is recommended unless certain criteria are present: local neck compressive/obstructive symptoms that can be confidently attributed to a thyroid nodule; patient preference (eg, due to anxiety or aesthetics); or higher index of suspicion (eg, history of previous radiation exposure, progressive nodule growth, or suspicious characteristics on US).4,5

If surgical removal of a benign thyroid nodule is recommended, it is imperative to discuss the risks with patients. In addition to traditional surgery risks, thyroidectomy is associated with transient or permanent postoperative hypoparathyroidism, as well as vocal hoarseness or changes in vocal quality due to the proximity of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Additionally, patients should be advised of the potential for surgical hypothyroidism with hemithyroidectomy and certain irreversible hypothyroidism with total thyroidectomy.

After a discussion of the risks and cost of observation versus surgery, an informed decision between provider and patient can ultimately be reached.

Would thyroidectomy be recommended for Felicia? After a thorough discussion, it is decided that surgery is not indicated at this time. Relevant factors include the benign thyroid US characteristics, lack of clinical neck compressive symptoms, and patient preference.

According to the American Thyroid Association guidelines, Felicia’s risk for malignancy for the nodule in question is < 3%, since it is a partially cystic nodule without any suspicious sonographic features. By foregoing surgery, Felicia will need repeated imaging studies and possibly repeat serologic studies and FNA in the future.

References

1. Stang MT, Carty SE. Recent developments in predicting thyroid malignancy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;21(1):11-17.

2. Hambleton C, Kandil E. Appropriate and accurate diagnosis of thyroid nodules: a review of thyroid fine-needle aspiration. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2013;6(6):413-422.

3. American Cancer Society. Thyroid cancer (2014). www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003144-pdf.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2016.

4. Gharib H, Papini E, Garber J, et al; AACE/AME/ETA Task Force on Thyroid Nodules. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Associazione Medici Endocrinologi, and European Thyroid Association medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules—2016 Update. Endocrine Pract. 2016;22(suppl 1):1-60.

5. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016; 26(1):1-133.

6. Yeung MJ, Serpell JW. Management of the solitary thyroid nodule. Oncologist. 2008; 13(2):105-112.

7. Renshaw A. Significance of repeatedly nondiagnostic thyroid fine-needle aspirations. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135(5):750-752.

A new-onset thyroid nodule, found on exam or incidentally on imaging, is a common presentation at primary care and specialist clinics. Palpable nodules are present in 4% to 7% of the population.1 However, more sensitive evaluation with thyroid ultrasound (US) suggests an incidence as high as 70%.2

According to the American Cancer Society, in 2015, there were approximately 62,450 new cases of thyroid cancer in the United States (with 2.5 times as many occurring in women as in men).3 In fact, thyroid cancer is the most rapidly increasing cancer in the United States—attributable in part to the increased use of thyroid US and incidental detection.3

The high prevalence of thyroid nodules makes appropriate evaluation and treatment crucial. This article, through a case study, explores the evaluation of a thyroid nodule and the recommendation for and against thyroidectomy.

Felicia, 49, presents to the endocrine clinic as a new patient with questions about multinodular goiter (MNG). She has been advised by ENT to have a left-sided dominant nodule surgically removed while under anesthesia during her upcoming chronic sinusitis surgery. Felicia would like to avoid thyroid surgery, if possible. Her most recent thyroid US, performed three months ago, showed a right lobe with multiple colloid nodules with inspissated colloid, the largest of which is 1.5 cm, and a 4-cm complex, solid, cystic nodule with inspissated colloid in the cystic spaces replacing the entire left thyroid lobe.

HistoryThe first step is establishing a history of the nodule(s) in question. Key questions are listed in Table 1. The onset and progression of a thyroid nodule must be determined; ideally, the provider should review any previous studies related to the thyroid gland. This will help determine if the nodule is new, if it has been evaluated in the past, and if it has changed significantly.

A thorough history can identify risk factors for malignancy, which include a personal history of cancer or radiation exposure, as well as a family history of thyroid cancer or malignant endocrine syndromes.

Felicia denies any family or personal medical history concerning for malignancy. She notes that she has two sisters with MNG. She denies any neck pain, compressive/obstructive symptoms, and hypo- or hyperthyroid symptoms.

She reports that she was found to have a goiter on exam and was subsequently diagnosed with MNG in 2008. Thyroid US showed a 2.3-cm complex, largely solid mass in the right mid-pole and a 3.3-cm largely cystic lesion in the left mid-pole. She was referred for right-sided fine-needle aspiration (FNA); results were consistent with benign colloid nodule. The left-sided nodule was not biopsied at that time, due to a largely cystic component.

Felicia underwent a follow-up US in 2011; it showed a 1.6-cm right mid-pole nodule with multiple nonspecific echogenic areas; a 1-cm benign-appearing nodule; and a 3.7-cm highly vascular heterogeneous mass with some colloid components with indeterminate component in the left lower and mid-pole. She reports that she did not follow up in 2011. Her next evaluation was the current thyroid US. She has never had FNA of the left-sided dominant nodule.

Continue for symptomatic vs asymptomatic thyroid nodules >>

Symptomatic vs Asymptomatic Thyroid NodulesEvaluation of a symptomatic thyroid nodule can help to determine the need for surgery, as well as assess the level of interference with a patient’s activities of daily living and the potential for functional abnormalities. However, both local neck and constitutional symptoms may be nonspecific and unrelated to the thyroid gland’s structure or function. Therefore, the provider should exercise caution in making recommendations based on reported symptoms alone.

Symptoms indicative of the need for surgical intervention include neck pain, increased neck pressure, foreign body sensation, dysphonia, dyspnea, and dysphagia. However, it is essential to determine if these symptoms are likely due to a thyroid nodule or if they can be attributed to a secondary cause (eg, postnasal drip, vocal cord dysfunction, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or esophageal stricture).

If the findings are inconsistent with the clinical picture, secondary evaluation is prudent to avoid an unnecessary procedure.

Physical ExamPalpation of a thyroid nodule is an unreliable indicator of risk for malignancy. Palpation alone does not allow for detection of all nodules, particularly smaller ones, and specific characteristics are not discernible. Imaging studies are required to accurately evaluate a thyroid nodule and determine the most appropriate course of action.

Palpation can be used to evaluate for a larger and/or fixed nodule, thyroid gland/nodule tenderness, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Physical exam can also assess for signs of hypo- or hyperthyroidism, including abnormal pulse rate or blood pressure, tremor, hypo- or hyperreflexia, and integumentary abnormalities (eg, hair loss, abnormal skin temperature, and nail changes).

Continue for serologic evaluation >>

Serologic Evaluation

If a thyroid nodule is suspected on exam or found on imaging, assessment of thyroid function, via thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) measurement, is the recommended first step. If TSH is elevated, further evaluation for hypothyroidism is recommended, with testing for free thyroxine (T4) and antithyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies.4 If TSH is suppressed, further evaluation with free T4 and assessment for underlying causes of hyperthyroidism are indicated, including work-up for toxic nodular goiter.

Routine monitoring of serum calcitonin level is not recommended. However, if there is suspicion for medullary thyroid cancer—based on either US findings or family history—serologic screening for abnormal calcitonin level may be indicated.4,5

Felicia’s lab results include a TSH of 1.30 µIU/mL (reference range, 0.30-3.00 µIU/mL). Based on this finding, what (if any) further serologic testing is recommended? None: With normal TSH and no concerning family or personal history, additional laboratory evaluation is not indicated.

Imaging a Thyroid Nodule

Thyroid US is the most sensitive imaging study for evaluating thyroid nodule characteristics. Thyroid uptake and scan is not indicated unless TSH is suppressed and evaluation for toxic nodular goiter is needed. Additional imaging studies, such as CT or MRI, are not recommended for thyroid nodule evaluation.

Based on the thyroid US, what characteristics of Felicia’s nodule are suggestive of a benign nodule? Of a malignant nodule? (See Table 2.)

FNA of the left-sided dominant nodule is indicated, based on the US findings of a partially solid component and size > 1 cm. Unfortunately, FNA is nondiagnostic, because it yielded cystic fluid only with scant follicular cells for evaluation.

Continue to now what? >>

Now What?

While FNA most definitively distinguishes between benign and malignant nodules, the test is limited. An indeterminate, or nondiagnostic, finding occurs in 10% to 15% of cases and is more likely in nodules with a large cystic component.1

Even a benign finding on FNA of a larger nodule should be viewed with caution, since aspiration is unlikely to pinpoint small insidious malignant cells nestled among a larger collection of benign tissue.3 In many situations, a patient receives FNA results and asks, “What should we do now?”

Nondiagnostic nodules

When FNA is indeterminate, the next step depends on the characteristics of the nodule. For a solid nodule, repeat FNA is recommended.4,5 For nodules with repeatedly nondiagnostic FNAs, the American Academy of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association recommend that a solid nodule be considered for surgical removal unless the nodule has “clearly favorable clinical and US features.”4,5

Surgical excision should be considered for cysts that recur, those that are larger (> 4 cm), and those that are repeatedly nondiagnostic on FNA. Personal and family history should be taken into account when nodules that are nondiagnostic on FNA demonstrate suspicious characteristics on US.6

An analysis by Renshaw determined that risk for malignancy in a nodule with a single nondiagnostic FNA was about 20%. For nodules that underwent repeat FNA, the risk was 0% for those that were again nondiagnostic. This significant difference led the author to conclude that “patients with two sequential nondiagnostic thyroid aspirates have a very low risk of malignancy.”7

Consider the time commitment, financial burden, and emotional cost for the patient of repeated evaluation with thyroid US and possibly FNA. In recurrent cases, the risks associated with surgery begin to be outweighed by the cost and burden of prolonged observation.

Benign nodules

With a biopsy-proven benign nodule, observation is recommended unless certain criteria are present: local neck compressive/obstructive symptoms that can be confidently attributed to a thyroid nodule; patient preference (eg, due to anxiety or aesthetics); or higher index of suspicion (eg, history of previous radiation exposure, progressive nodule growth, or suspicious characteristics on US).4,5

If surgical removal of a benign thyroid nodule is recommended, it is imperative to discuss the risks with patients. In addition to traditional surgery risks, thyroidectomy is associated with transient or permanent postoperative hypoparathyroidism, as well as vocal hoarseness or changes in vocal quality due to the proximity of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Additionally, patients should be advised of the potential for surgical hypothyroidism with hemithyroidectomy and certain irreversible hypothyroidism with total thyroidectomy.

After a discussion of the risks and cost of observation versus surgery, an informed decision between provider and patient can ultimately be reached.

Would thyroidectomy be recommended for Felicia? After a thorough discussion, it is decided that surgery is not indicated at this time. Relevant factors include the benign thyroid US characteristics, lack of clinical neck compressive symptoms, and patient preference.

According to the American Thyroid Association guidelines, Felicia’s risk for malignancy for the nodule in question is < 3%, since it is a partially cystic nodule without any suspicious sonographic features. By foregoing surgery, Felicia will need repeated imaging studies and possibly repeat serologic studies and FNA in the future.

References

1. Stang MT, Carty SE. Recent developments in predicting thyroid malignancy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;21(1):11-17.

2. Hambleton C, Kandil E. Appropriate and accurate diagnosis of thyroid nodules: a review of thyroid fine-needle aspiration. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2013;6(6):413-422.

3. American Cancer Society. Thyroid cancer (2014). www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003144-pdf.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2016.

4. Gharib H, Papini E, Garber J, et al; AACE/AME/ETA Task Force on Thyroid Nodules. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Associazione Medici Endocrinologi, and European Thyroid Association medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules—2016 Update. Endocrine Pract. 2016;22(suppl 1):1-60.

5. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016; 26(1):1-133.

6. Yeung MJ, Serpell JW. Management of the solitary thyroid nodule. Oncologist. 2008; 13(2):105-112.

7. Renshaw A. Significance of repeatedly nondiagnostic thyroid fine-needle aspirations. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135(5):750-752.

A new-onset thyroid nodule, found on exam or incidentally on imaging, is a common presentation at primary care and specialist clinics. Palpable nodules are present in 4% to 7% of the population.1 However, more sensitive evaluation with thyroid ultrasound (US) suggests an incidence as high as 70%.2

According to the American Cancer Society, in 2015, there were approximately 62,450 new cases of thyroid cancer in the United States (with 2.5 times as many occurring in women as in men).3 In fact, thyroid cancer is the most rapidly increasing cancer in the United States—attributable in part to the increased use of thyroid US and incidental detection.3

The high prevalence of thyroid nodules makes appropriate evaluation and treatment crucial. This article, through a case study, explores the evaluation of a thyroid nodule and the recommendation for and against thyroidectomy.

Felicia, 49, presents to the endocrine clinic as a new patient with questions about multinodular goiter (MNG). She has been advised by ENT to have a left-sided dominant nodule surgically removed while under anesthesia during her upcoming chronic sinusitis surgery. Felicia would like to avoid thyroid surgery, if possible. Her most recent thyroid US, performed three months ago, showed a right lobe with multiple colloid nodules with inspissated colloid, the largest of which is 1.5 cm, and a 4-cm complex, solid, cystic nodule with inspissated colloid in the cystic spaces replacing the entire left thyroid lobe.

HistoryThe first step is establishing a history of the nodule(s) in question. Key questions are listed in Table 1. The onset and progression of a thyroid nodule must be determined; ideally, the provider should review any previous studies related to the thyroid gland. This will help determine if the nodule is new, if it has been evaluated in the past, and if it has changed significantly.

A thorough history can identify risk factors for malignancy, which include a personal history of cancer or radiation exposure, as well as a family history of thyroid cancer or malignant endocrine syndromes.

Felicia denies any family or personal medical history concerning for malignancy. She notes that she has two sisters with MNG. She denies any neck pain, compressive/obstructive symptoms, and hypo- or hyperthyroid symptoms.

She reports that she was found to have a goiter on exam and was subsequently diagnosed with MNG in 2008. Thyroid US showed a 2.3-cm complex, largely solid mass in the right mid-pole and a 3.3-cm largely cystic lesion in the left mid-pole. She was referred for right-sided fine-needle aspiration (FNA); results were consistent with benign colloid nodule. The left-sided nodule was not biopsied at that time, due to a largely cystic component.

Felicia underwent a follow-up US in 2011; it showed a 1.6-cm right mid-pole nodule with multiple nonspecific echogenic areas; a 1-cm benign-appearing nodule; and a 3.7-cm highly vascular heterogeneous mass with some colloid components with indeterminate component in the left lower and mid-pole. She reports that she did not follow up in 2011. Her next evaluation was the current thyroid US. She has never had FNA of the left-sided dominant nodule.

Continue for symptomatic vs asymptomatic thyroid nodules >>

Symptomatic vs Asymptomatic Thyroid NodulesEvaluation of a symptomatic thyroid nodule can help to determine the need for surgery, as well as assess the level of interference with a patient’s activities of daily living and the potential for functional abnormalities. However, both local neck and constitutional symptoms may be nonspecific and unrelated to the thyroid gland’s structure or function. Therefore, the provider should exercise caution in making recommendations based on reported symptoms alone.

Symptoms indicative of the need for surgical intervention include neck pain, increased neck pressure, foreign body sensation, dysphonia, dyspnea, and dysphagia. However, it is essential to determine if these symptoms are likely due to a thyroid nodule or if they can be attributed to a secondary cause (eg, postnasal drip, vocal cord dysfunction, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or esophageal stricture).

If the findings are inconsistent with the clinical picture, secondary evaluation is prudent to avoid an unnecessary procedure.

Physical ExamPalpation of a thyroid nodule is an unreliable indicator of risk for malignancy. Palpation alone does not allow for detection of all nodules, particularly smaller ones, and specific characteristics are not discernible. Imaging studies are required to accurately evaluate a thyroid nodule and determine the most appropriate course of action.

Palpation can be used to evaluate for a larger and/or fixed nodule, thyroid gland/nodule tenderness, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Physical exam can also assess for signs of hypo- or hyperthyroidism, including abnormal pulse rate or blood pressure, tremor, hypo- or hyperreflexia, and integumentary abnormalities (eg, hair loss, abnormal skin temperature, and nail changes).

Continue for serologic evaluation >>

Serologic Evaluation

If a thyroid nodule is suspected on exam or found on imaging, assessment of thyroid function, via thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) measurement, is the recommended first step. If TSH is elevated, further evaluation for hypothyroidism is recommended, with testing for free thyroxine (T4) and antithyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies.4 If TSH is suppressed, further evaluation with free T4 and assessment for underlying causes of hyperthyroidism are indicated, including work-up for toxic nodular goiter.

Routine monitoring of serum calcitonin level is not recommended. However, if there is suspicion for medullary thyroid cancer—based on either US findings or family history—serologic screening for abnormal calcitonin level may be indicated.4,5

Felicia’s lab results include a TSH of 1.30 µIU/mL (reference range, 0.30-3.00 µIU/mL). Based on this finding, what (if any) further serologic testing is recommended? None: With normal TSH and no concerning family or personal history, additional laboratory evaluation is not indicated.

Imaging a Thyroid Nodule

Thyroid US is the most sensitive imaging study for evaluating thyroid nodule characteristics. Thyroid uptake and scan is not indicated unless TSH is suppressed and evaluation for toxic nodular goiter is needed. Additional imaging studies, such as CT or MRI, are not recommended for thyroid nodule evaluation.

Based on the thyroid US, what characteristics of Felicia’s nodule are suggestive of a benign nodule? Of a malignant nodule? (See Table 2.)

FNA of the left-sided dominant nodule is indicated, based on the US findings of a partially solid component and size > 1 cm. Unfortunately, FNA is nondiagnostic, because it yielded cystic fluid only with scant follicular cells for evaluation.

Continue to now what? >>

Now What?

While FNA most definitively distinguishes between benign and malignant nodules, the test is limited. An indeterminate, or nondiagnostic, finding occurs in 10% to 15% of cases and is more likely in nodules with a large cystic component.1

Even a benign finding on FNA of a larger nodule should be viewed with caution, since aspiration is unlikely to pinpoint small insidious malignant cells nestled among a larger collection of benign tissue.3 In many situations, a patient receives FNA results and asks, “What should we do now?”

Nondiagnostic nodules

When FNA is indeterminate, the next step depends on the characteristics of the nodule. For a solid nodule, repeat FNA is recommended.4,5 For nodules with repeatedly nondiagnostic FNAs, the American Academy of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association recommend that a solid nodule be considered for surgical removal unless the nodule has “clearly favorable clinical and US features.”4,5

Surgical excision should be considered for cysts that recur, those that are larger (> 4 cm), and those that are repeatedly nondiagnostic on FNA. Personal and family history should be taken into account when nodules that are nondiagnostic on FNA demonstrate suspicious characteristics on US.6

An analysis by Renshaw determined that risk for malignancy in a nodule with a single nondiagnostic FNA was about 20%. For nodules that underwent repeat FNA, the risk was 0% for those that were again nondiagnostic. This significant difference led the author to conclude that “patients with two sequential nondiagnostic thyroid aspirates have a very low risk of malignancy.”7

Consider the time commitment, financial burden, and emotional cost for the patient of repeated evaluation with thyroid US and possibly FNA. In recurrent cases, the risks associated with surgery begin to be outweighed by the cost and burden of prolonged observation.

Benign nodules

With a biopsy-proven benign nodule, observation is recommended unless certain criteria are present: local neck compressive/obstructive symptoms that can be confidently attributed to a thyroid nodule; patient preference (eg, due to anxiety or aesthetics); or higher index of suspicion (eg, history of previous radiation exposure, progressive nodule growth, or suspicious characteristics on US).4,5

If surgical removal of a benign thyroid nodule is recommended, it is imperative to discuss the risks with patients. In addition to traditional surgery risks, thyroidectomy is associated with transient or permanent postoperative hypoparathyroidism, as well as vocal hoarseness or changes in vocal quality due to the proximity of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Additionally, patients should be advised of the potential for surgical hypothyroidism with hemithyroidectomy and certain irreversible hypothyroidism with total thyroidectomy.

After a discussion of the risks and cost of observation versus surgery, an informed decision between provider and patient can ultimately be reached.

Would thyroidectomy be recommended for Felicia? After a thorough discussion, it is decided that surgery is not indicated at this time. Relevant factors include the benign thyroid US characteristics, lack of clinical neck compressive symptoms, and patient preference.

According to the American Thyroid Association guidelines, Felicia’s risk for malignancy for the nodule in question is < 3%, since it is a partially cystic nodule without any suspicious sonographic features. By foregoing surgery, Felicia will need repeated imaging studies and possibly repeat serologic studies and FNA in the future.

References

1. Stang MT, Carty SE. Recent developments in predicting thyroid malignancy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;21(1):11-17.

2. Hambleton C, Kandil E. Appropriate and accurate diagnosis of thyroid nodules: a review of thyroid fine-needle aspiration. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2013;6(6):413-422.

3. American Cancer Society. Thyroid cancer (2014). www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003144-pdf.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2016.

4. Gharib H, Papini E, Garber J, et al; AACE/AME/ETA Task Force on Thyroid Nodules. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Associazione Medici Endocrinologi, and European Thyroid Association medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules—2016 Update. Endocrine Pract. 2016;22(suppl 1):1-60.

5. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016; 26(1):1-133.

6. Yeung MJ, Serpell JW. Management of the solitary thyroid nodule. Oncologist. 2008; 13(2):105-112.

7. Renshaw A. Significance of repeatedly nondiagnostic thyroid fine-needle aspirations. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135(5):750-752.

An Alarming Slip of the Hip

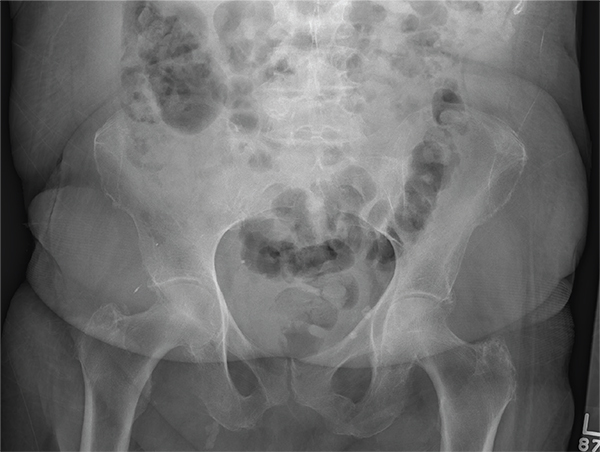

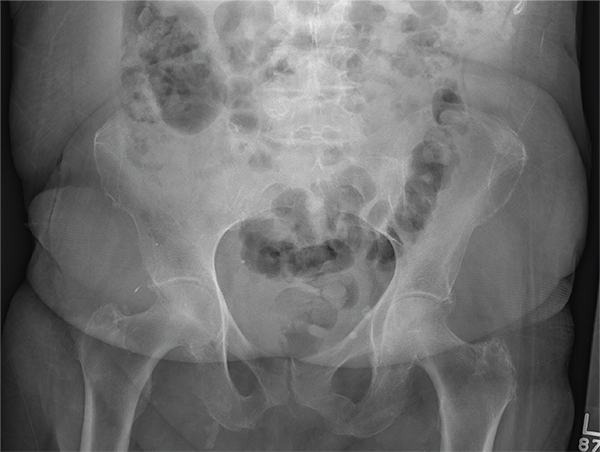

After a fall, an 80-year-old woman is brought to the emergency department for evaluation of hip pain. She was getting out of bed when she slipped, fell, and landed on her right hip; bearing weight now is painful. She denies hitting her head. The patient’s vital signs are normal. Her medical history is significant for hypertension and diabetes. Inspection of the hip reveals no obvious deformity or shortening. The right lateral aspect of the hip exhibits mild swelling and decreased range of motion secondary to the pain. You order a pelvic radiograph, which is shown. What is your impression?

Risk of Zika virus remains low at Olympics

People attending the 2016 Summer Olympic games in Rio de Janeiro stand a low risk of contracting or spreading the Zika virus, says a new report in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Attendance at the Rio Olympics is estimated to be between 350,000 and 500,000, according to the report – written by Albert I. Ko, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn. and his colleagues – and in the worst-case scenario, the projected likelihood of infection will be between 1 in 56,300 and 1 in 6,200. This means that, at most, 80 people attending the games will contract the Zika virus (95% confidence interval, 63-98), while the lower bound of the estimate is a mere 6 individuals (95% CI, 2-12). Furthermore, only 1-16 individuals (95% CI, 0-4 and 9-24, respectively) of infected individuals are expected to be symptomatic (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jul 26. doi: 10.7326/M16-1628).

Data from the 2014 FIFA World Cup tournament – which also took place in Brazil – estimates that 53.3% of attendees will come from one of eight countries or regions: United States, Canada, Europe, Oceania, Japan, South Korea, and Israel, all of which are locations where mosquito-borne disease transmission rates are expected to be low. Individuals who contract Zika virus and take it back home with them are expected to number between 3 (95% CI, 0-7) and 37 (95% CI, 25-49), mainly because the Zika virus is only expected to take 9.9 days to naturally clear any infected individual.

“Most of the remaining travelers (30.2% of the total) are expected to return to Latin American countries already experiencing autochthonous ZIKV transmission, contributing 9.0 (0.0 to 29.7) to 116.0 (59.4 to 188.1) additional person-days of viremia,” the report states. “This effect is negligible relative to prevalent infections caused by ongoing transmission in these countries.”

Recently, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also announced that chances of acquiring the Zika virus are low for those attending the 2016 Summer Olympics, and that only individuals from a small number of countries have any real danger of introducing the disease into a previously unaffected and potentially dangerous climate.

Sexual transmission of Zika virus remains a risk, however, the Annals report notes. People are urged to use condoms or abstain from sex during the Olympics in order to mitigate the risk of spreading the disease. Additionally, women who attend the games are best advised to delay getting pregnant for several weeks, if not months, after returning home. Women who are already pregnant should not attend the games, and everyone who attends the Olympics should wear mosquito repellent, long-sleeve shirts and pants, and use either a fan or a mosquito net in their hotel rooms to avoid getting bitten.

Dr. Ko and his coauthors declared no conflicts of interest.

People attending the 2016 Summer Olympic games in Rio de Janeiro stand a low risk of contracting or spreading the Zika virus, says a new report in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Attendance at the Rio Olympics is estimated to be between 350,000 and 500,000, according to the report – written by Albert I. Ko, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn. and his colleagues – and in the worst-case scenario, the projected likelihood of infection will be between 1 in 56,300 and 1 in 6,200. This means that, at most, 80 people attending the games will contract the Zika virus (95% confidence interval, 63-98), while the lower bound of the estimate is a mere 6 individuals (95% CI, 2-12). Furthermore, only 1-16 individuals (95% CI, 0-4 and 9-24, respectively) of infected individuals are expected to be symptomatic (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jul 26. doi: 10.7326/M16-1628).

Data from the 2014 FIFA World Cup tournament – which also took place in Brazil – estimates that 53.3% of attendees will come from one of eight countries or regions: United States, Canada, Europe, Oceania, Japan, South Korea, and Israel, all of which are locations where mosquito-borne disease transmission rates are expected to be low. Individuals who contract Zika virus and take it back home with them are expected to number between 3 (95% CI, 0-7) and 37 (95% CI, 25-49), mainly because the Zika virus is only expected to take 9.9 days to naturally clear any infected individual.

“Most of the remaining travelers (30.2% of the total) are expected to return to Latin American countries already experiencing autochthonous ZIKV transmission, contributing 9.0 (0.0 to 29.7) to 116.0 (59.4 to 188.1) additional person-days of viremia,” the report states. “This effect is negligible relative to prevalent infections caused by ongoing transmission in these countries.”

Recently, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also announced that chances of acquiring the Zika virus are low for those attending the 2016 Summer Olympics, and that only individuals from a small number of countries have any real danger of introducing the disease into a previously unaffected and potentially dangerous climate.

Sexual transmission of Zika virus remains a risk, however, the Annals report notes. People are urged to use condoms or abstain from sex during the Olympics in order to mitigate the risk of spreading the disease. Additionally, women who attend the games are best advised to delay getting pregnant for several weeks, if not months, after returning home. Women who are already pregnant should not attend the games, and everyone who attends the Olympics should wear mosquito repellent, long-sleeve shirts and pants, and use either a fan or a mosquito net in their hotel rooms to avoid getting bitten.

Dr. Ko and his coauthors declared no conflicts of interest.

People attending the 2016 Summer Olympic games in Rio de Janeiro stand a low risk of contracting or spreading the Zika virus, says a new report in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Attendance at the Rio Olympics is estimated to be between 350,000 and 500,000, according to the report – written by Albert I. Ko, MD, of Yale University in New Haven, Conn. and his colleagues – and in the worst-case scenario, the projected likelihood of infection will be between 1 in 56,300 and 1 in 6,200. This means that, at most, 80 people attending the games will contract the Zika virus (95% confidence interval, 63-98), while the lower bound of the estimate is a mere 6 individuals (95% CI, 2-12). Furthermore, only 1-16 individuals (95% CI, 0-4 and 9-24, respectively) of infected individuals are expected to be symptomatic (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jul 26. doi: 10.7326/M16-1628).

Data from the 2014 FIFA World Cup tournament – which also took place in Brazil – estimates that 53.3% of attendees will come from one of eight countries or regions: United States, Canada, Europe, Oceania, Japan, South Korea, and Israel, all of which are locations where mosquito-borne disease transmission rates are expected to be low. Individuals who contract Zika virus and take it back home with them are expected to number between 3 (95% CI, 0-7) and 37 (95% CI, 25-49), mainly because the Zika virus is only expected to take 9.9 days to naturally clear any infected individual.

“Most of the remaining travelers (30.2% of the total) are expected to return to Latin American countries already experiencing autochthonous ZIKV transmission, contributing 9.0 (0.0 to 29.7) to 116.0 (59.4 to 188.1) additional person-days of viremia,” the report states. “This effect is negligible relative to prevalent infections caused by ongoing transmission in these countries.”

Recently, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also announced that chances of acquiring the Zika virus are low for those attending the 2016 Summer Olympics, and that only individuals from a small number of countries have any real danger of introducing the disease into a previously unaffected and potentially dangerous climate.

Sexual transmission of Zika virus remains a risk, however, the Annals report notes. People are urged to use condoms or abstain from sex during the Olympics in order to mitigate the risk of spreading the disease. Additionally, women who attend the games are best advised to delay getting pregnant for several weeks, if not months, after returning home. Women who are already pregnant should not attend the games, and everyone who attends the Olympics should wear mosquito repellent, long-sleeve shirts and pants, and use either a fan or a mosquito net in their hotel rooms to avoid getting bitten.

Dr. Ko and his coauthors declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Hemophilia guideline recommends integrated care model

ORLANDO – An integrated care model that includes a hematologist, a specialized hematology nurse, a physical therapist, a social worker, and 24/7 access to a specialized coagulation laboratory is recommended in a new hemophilia care guideline jointly developed by the National Hemophilia Foundation and McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario.

The guideline has been formally accepted for inclusion in the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC), the National Hemophilia Foundation announced at its annual meeting, held immediately before the World Hemophilia Foundation World Congress here.

“The integrated care model, as is utilized within the U.S. federally funded network of hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs), should be advocated for optimal care of persons with hemophilia,” wrote guideline coauthors Steven W. Pipe, MD, from the University of Michigan School of Medicine in Ann Arbor, and Craig M. Kessler, MD, from Georgetown University in Washington, in an introduction to the guideline, published in the journal Hemophilia.