User login

Impressive bleeding profile with factor XI inhibitor in AFib: AZALEA

; the risk of stroke was moderate to high.

The trial was stopped earlier this year because of an “overwhelming” reduction in bleeding with abelacimab in comparison to rivaroxaban. Abelacimab is a monoclonal antibody given by subcutaneous injection once a month.

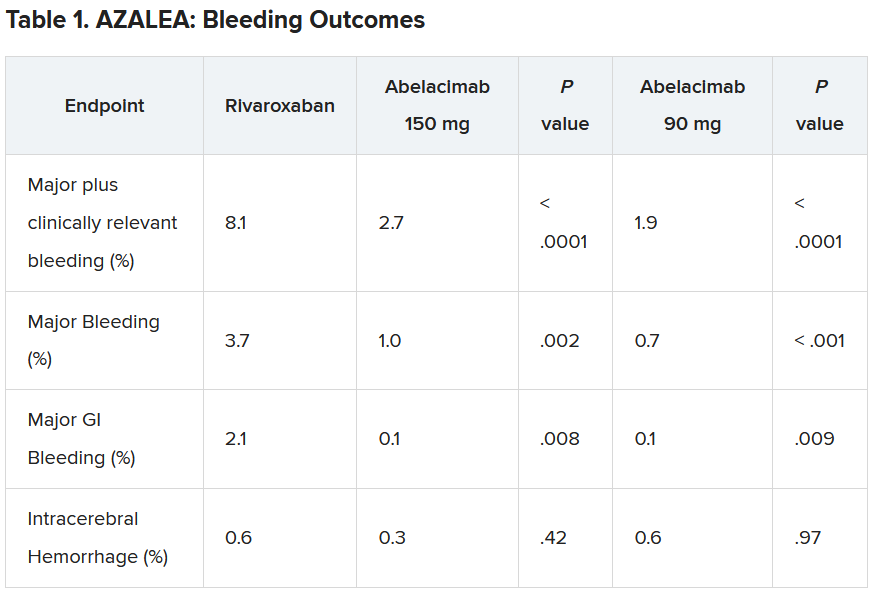

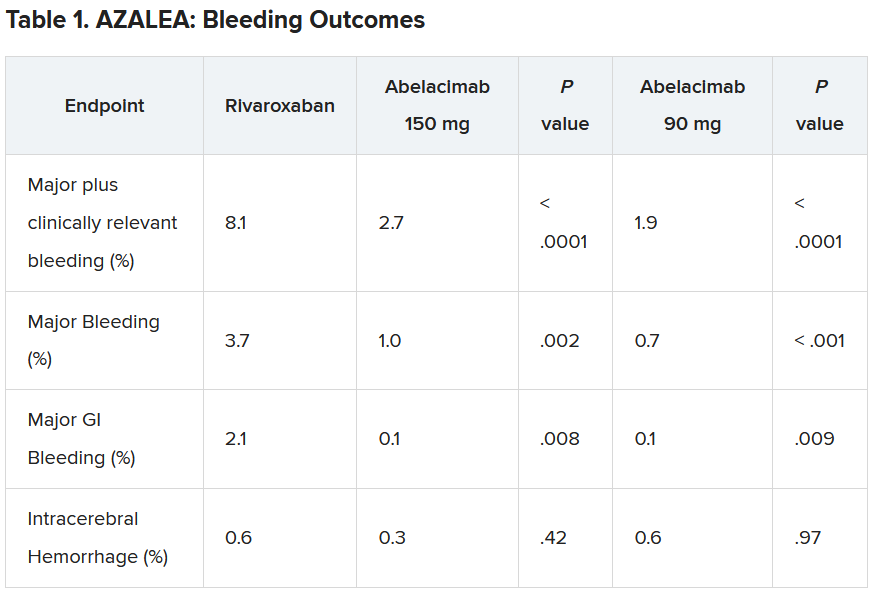

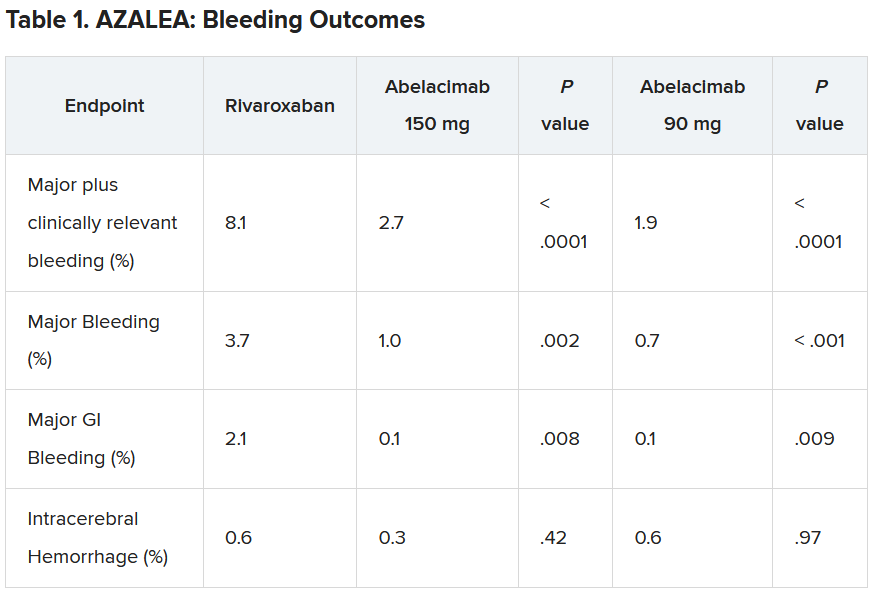

“Details of the bleeding results have now shown that the 150-mg dose of abelacimab, which is the dose being carried forward to phase 3 trials, was associated with a 67% reduction in major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, the primary endpoint of the study.”

In addition, major bleeding was reduced by 74%, and major gastrointestinal bleeding was reduced by 93%.

“We are seeing really profound reductions in bleeding with this agent vs. a NOAC [novel oral anticoagulant],” lead AZALEA investigator Christian Ruff, MD, professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“Major bleeding – effectively the type of bleeding that results in hospitalization – is reduced by more than two-thirds, and major GI bleeding – which is the most common type of bleeding experienced by AF patients on anticoagulants – is almost eliminated. This gives us real hope that we have finally found an anticoagulant that is remarkably safe and will allow us to use anticoagulation in our most vulnerable patients,” he said.

Dr. Ruff presented the full results from the AZALEA trial at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He noted that AFib is one of the most common medical conditions in the world and that it confers an increased risk of stroke. Anticoagulants reduce this risk very effectively, and while the NOACS, such as apixaban and rivaroxaban, are safer than warfarin, significant bleeding still occurs, and “shockingly,” he said, between 30% and 60% of patients are not prescribed an anticoagulant or discontinue treatment because of bleeding concerns.

“Clearly, we need safer anticoagulants to protect these patients. Factor XI inhibitors, of which abelacimab is one, have emerged as the most promising agents, as they are thought to provide precision anticoagulation,” Dr. Ruff said.

He explained that factor XI appears to be involved in the formation of thrombus, which blocks arteries and causes strokes and myocardial infarction (thrombosis), but not in the healing process of blood vessels after injury (hemostasis). So, it is believed that inhibiting factor XI should reduce thrombotic events without causing excess bleeding.

AZALEA, which is the largest and longest trial of a factor XI inhibitor to date, enrolled 1,287 adults with AF who were at moderate to high risk of stroke.

They were randomly assigned to receive one of three treatments: oral rivaroxaban 20 mg daily; abelacimab 90 mg; or abelacimab 150 mg. Abelacimab was given monthly by injection.

Both doses of abelacimab inhibited factor XI almost completely; 97% inhibition was achieved with the 90-mg dose, and 99% inhibition was achieved with the 150-mg dose.

Results showed that after a median follow-up of 1.8 years, there was a clear reduction in all bleeding endpoints with both doses of abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban.

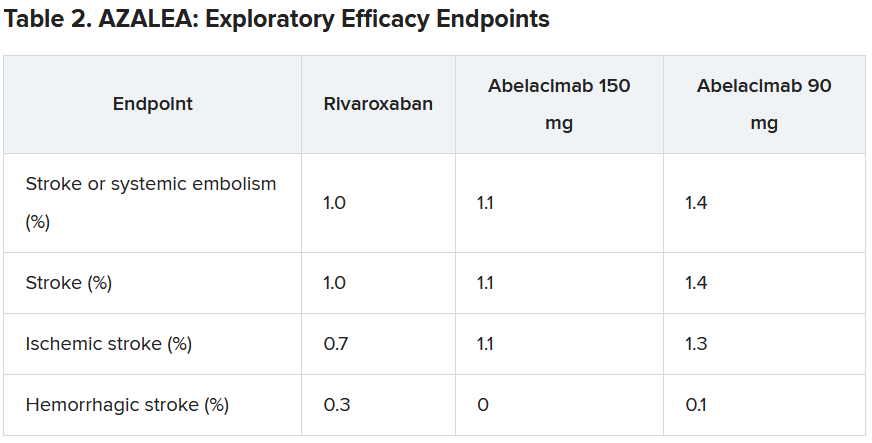

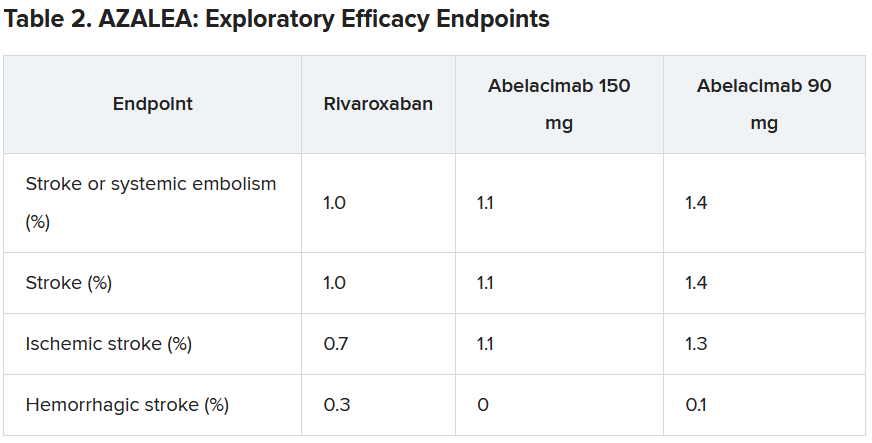

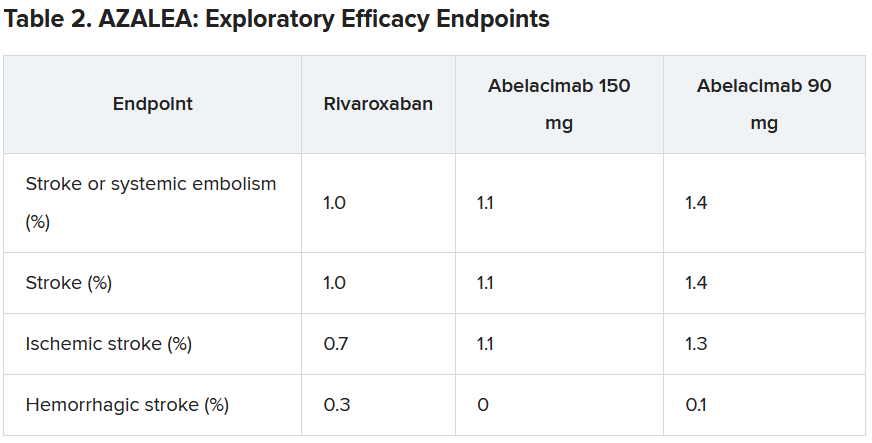

Dr. Ruff explained that the trial was powered to detect differences in bleeding, not stroke, but the investigators approached this in an exploratory way.

“As expected, the numbers were low, with just 25 strokes (23 ischemic strokes) across all three groups in the trial. So, because of this very low rate, we are really not able to compare how abelacimab compares with rivaroxaban in reducing stroke,” he commented.

He did, however, suggest that the low stroke rate in the study was encouraging.

“If we look at the same population without anticoagulation, the stroke rate would be about 7% per year. And we see here in this trial that in all three arms, the stroke rate was just above 1% per year. I think this shows that all the patients in the trial were getting highly effective anticoagulation,” he said.

“But what this trial doesn’t answer – because the numbers are so low – is exactly how effective factor XI inhibition with abelacimab is, compared to NOACs in reducing stroke rates. That requires dedicated phase 3 trials.”

Dr. Ruff pointed out that there are some reassuring data from phase 2 trials in venous thromboembolism (VTE), in which the 150-mg dose of abelacimab was associated with an 80% reduction in VTE, compared with enoxaparin. “Historically in the development of anticoagulants, efficacy in VTE has translated into efficacy in stroke prevention, so that is very encouraging,” he commented.

“So, I think our results along with the VTE results are encouraging, but the precision regarding the relative efficacy compared to NOACs is still an open question that needs to be clarified in phase 3 trials,” he concluded.

Several phase 3 trials are now underway with abelacimab and two other small-molecule orally available factor XI inhibitors, milvexian (BMS/Janssen) and asundexian (Bayer).

The designated discussant of the AZALEA study at the AHA meeting, Manesh Patel. MD, Duke University, Durham, N.C., described the results as “an important step forward.”

“This trial, with the prior data in this field, show that factor XI inhibition as a target is biologically possible (studies showing > 95% inhibition), significantly less bleeding than NOACS. We await the phase 3 studies, but having significantly less bleeding and similar or less stroke would be a substantial step forward for the field,” he said.

John Alexander, MD, also from Duke University, said: “There were clinically important reductions in bleeding with both doses of abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban. This is consistent to what we’ve seen with comparisons between other factor XI inhibitors and other factor Xa inhibitors.”

On the exploratory efficacy results, Dr. Alexander agreed with Dr. Ruff that it was not possible to get any idea of how abelacimab compared with rivaroxaban in reducing stroke. “The hazard ratio and confidence intervals comparing abelacimab and rivaroxaban include substantial lower rates, no difference, and substantially higher rates,” he noted.

“We need to wait for the results of phase 3 trials, with abelacimab and other factor XI inhibitors, to understand how well factor XI inhibition prevents stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation,” Dr. Alexander added. “These trials are ongoing.”

Dr. Ruff concluded: “Assuming the data from ongoing phase 3 trials confirm the benefit of factor XI inhibitors for stroke prevention in people with AF, it will really be transformative for the field of cardiology.

“Our first mission in treating people with AF is to prevent stroke, and our ability to do this with a remarkably safe anticoagulant such as abelacimab would be an incredible advance,” he concluded.

Dr. Ruff receives research funding from Anthos for abelacimab trials, is on an AF executive committee for BMS/Janssen (milvexian), and has been on an advisory board for Bayer (asundexian). Dr. Patel has received grants from and acts as an advisor to Bayer and Janssen. Dr. Alexander receives research funding from Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

; the risk of stroke was moderate to high.

The trial was stopped earlier this year because of an “overwhelming” reduction in bleeding with abelacimab in comparison to rivaroxaban. Abelacimab is a monoclonal antibody given by subcutaneous injection once a month.

“Details of the bleeding results have now shown that the 150-mg dose of abelacimab, which is the dose being carried forward to phase 3 trials, was associated with a 67% reduction in major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, the primary endpoint of the study.”

In addition, major bleeding was reduced by 74%, and major gastrointestinal bleeding was reduced by 93%.

“We are seeing really profound reductions in bleeding with this agent vs. a NOAC [novel oral anticoagulant],” lead AZALEA investigator Christian Ruff, MD, professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“Major bleeding – effectively the type of bleeding that results in hospitalization – is reduced by more than two-thirds, and major GI bleeding – which is the most common type of bleeding experienced by AF patients on anticoagulants – is almost eliminated. This gives us real hope that we have finally found an anticoagulant that is remarkably safe and will allow us to use anticoagulation in our most vulnerable patients,” he said.

Dr. Ruff presented the full results from the AZALEA trial at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He noted that AFib is one of the most common medical conditions in the world and that it confers an increased risk of stroke. Anticoagulants reduce this risk very effectively, and while the NOACS, such as apixaban and rivaroxaban, are safer than warfarin, significant bleeding still occurs, and “shockingly,” he said, between 30% and 60% of patients are not prescribed an anticoagulant or discontinue treatment because of bleeding concerns.

“Clearly, we need safer anticoagulants to protect these patients. Factor XI inhibitors, of which abelacimab is one, have emerged as the most promising agents, as they are thought to provide precision anticoagulation,” Dr. Ruff said.

He explained that factor XI appears to be involved in the formation of thrombus, which blocks arteries and causes strokes and myocardial infarction (thrombosis), but not in the healing process of blood vessels after injury (hemostasis). So, it is believed that inhibiting factor XI should reduce thrombotic events without causing excess bleeding.

AZALEA, which is the largest and longest trial of a factor XI inhibitor to date, enrolled 1,287 adults with AF who were at moderate to high risk of stroke.

They were randomly assigned to receive one of three treatments: oral rivaroxaban 20 mg daily; abelacimab 90 mg; or abelacimab 150 mg. Abelacimab was given monthly by injection.

Both doses of abelacimab inhibited factor XI almost completely; 97% inhibition was achieved with the 90-mg dose, and 99% inhibition was achieved with the 150-mg dose.

Results showed that after a median follow-up of 1.8 years, there was a clear reduction in all bleeding endpoints with both doses of abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban.

Dr. Ruff explained that the trial was powered to detect differences in bleeding, not stroke, but the investigators approached this in an exploratory way.

“As expected, the numbers were low, with just 25 strokes (23 ischemic strokes) across all three groups in the trial. So, because of this very low rate, we are really not able to compare how abelacimab compares with rivaroxaban in reducing stroke,” he commented.

He did, however, suggest that the low stroke rate in the study was encouraging.

“If we look at the same population without anticoagulation, the stroke rate would be about 7% per year. And we see here in this trial that in all three arms, the stroke rate was just above 1% per year. I think this shows that all the patients in the trial were getting highly effective anticoagulation,” he said.

“But what this trial doesn’t answer – because the numbers are so low – is exactly how effective factor XI inhibition with abelacimab is, compared to NOACs in reducing stroke rates. That requires dedicated phase 3 trials.”

Dr. Ruff pointed out that there are some reassuring data from phase 2 trials in venous thromboembolism (VTE), in which the 150-mg dose of abelacimab was associated with an 80% reduction in VTE, compared with enoxaparin. “Historically in the development of anticoagulants, efficacy in VTE has translated into efficacy in stroke prevention, so that is very encouraging,” he commented.

“So, I think our results along with the VTE results are encouraging, but the precision regarding the relative efficacy compared to NOACs is still an open question that needs to be clarified in phase 3 trials,” he concluded.

Several phase 3 trials are now underway with abelacimab and two other small-molecule orally available factor XI inhibitors, milvexian (BMS/Janssen) and asundexian (Bayer).

The designated discussant of the AZALEA study at the AHA meeting, Manesh Patel. MD, Duke University, Durham, N.C., described the results as “an important step forward.”

“This trial, with the prior data in this field, show that factor XI inhibition as a target is biologically possible (studies showing > 95% inhibition), significantly less bleeding than NOACS. We await the phase 3 studies, but having significantly less bleeding and similar or less stroke would be a substantial step forward for the field,” he said.

John Alexander, MD, also from Duke University, said: “There were clinically important reductions in bleeding with both doses of abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban. This is consistent to what we’ve seen with comparisons between other factor XI inhibitors and other factor Xa inhibitors.”

On the exploratory efficacy results, Dr. Alexander agreed with Dr. Ruff that it was not possible to get any idea of how abelacimab compared with rivaroxaban in reducing stroke. “The hazard ratio and confidence intervals comparing abelacimab and rivaroxaban include substantial lower rates, no difference, and substantially higher rates,” he noted.

“We need to wait for the results of phase 3 trials, with abelacimab and other factor XI inhibitors, to understand how well factor XI inhibition prevents stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation,” Dr. Alexander added. “These trials are ongoing.”

Dr. Ruff concluded: “Assuming the data from ongoing phase 3 trials confirm the benefit of factor XI inhibitors for stroke prevention in people with AF, it will really be transformative for the field of cardiology.

“Our first mission in treating people with AF is to prevent stroke, and our ability to do this with a remarkably safe anticoagulant such as abelacimab would be an incredible advance,” he concluded.

Dr. Ruff receives research funding from Anthos for abelacimab trials, is on an AF executive committee for BMS/Janssen (milvexian), and has been on an advisory board for Bayer (asundexian). Dr. Patel has received grants from and acts as an advisor to Bayer and Janssen. Dr. Alexander receives research funding from Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

; the risk of stroke was moderate to high.

The trial was stopped earlier this year because of an “overwhelming” reduction in bleeding with abelacimab in comparison to rivaroxaban. Abelacimab is a monoclonal antibody given by subcutaneous injection once a month.

“Details of the bleeding results have now shown that the 150-mg dose of abelacimab, which is the dose being carried forward to phase 3 trials, was associated with a 67% reduction in major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, the primary endpoint of the study.”

In addition, major bleeding was reduced by 74%, and major gastrointestinal bleeding was reduced by 93%.

“We are seeing really profound reductions in bleeding with this agent vs. a NOAC [novel oral anticoagulant],” lead AZALEA investigator Christian Ruff, MD, professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“Major bleeding – effectively the type of bleeding that results in hospitalization – is reduced by more than two-thirds, and major GI bleeding – which is the most common type of bleeding experienced by AF patients on anticoagulants – is almost eliminated. This gives us real hope that we have finally found an anticoagulant that is remarkably safe and will allow us to use anticoagulation in our most vulnerable patients,” he said.

Dr. Ruff presented the full results from the AZALEA trial at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He noted that AFib is one of the most common medical conditions in the world and that it confers an increased risk of stroke. Anticoagulants reduce this risk very effectively, and while the NOACS, such as apixaban and rivaroxaban, are safer than warfarin, significant bleeding still occurs, and “shockingly,” he said, between 30% and 60% of patients are not prescribed an anticoagulant or discontinue treatment because of bleeding concerns.

“Clearly, we need safer anticoagulants to protect these patients. Factor XI inhibitors, of which abelacimab is one, have emerged as the most promising agents, as they are thought to provide precision anticoagulation,” Dr. Ruff said.

He explained that factor XI appears to be involved in the formation of thrombus, which blocks arteries and causes strokes and myocardial infarction (thrombosis), but not in the healing process of blood vessels after injury (hemostasis). So, it is believed that inhibiting factor XI should reduce thrombotic events without causing excess bleeding.

AZALEA, which is the largest and longest trial of a factor XI inhibitor to date, enrolled 1,287 adults with AF who were at moderate to high risk of stroke.

They were randomly assigned to receive one of three treatments: oral rivaroxaban 20 mg daily; abelacimab 90 mg; or abelacimab 150 mg. Abelacimab was given monthly by injection.

Both doses of abelacimab inhibited factor XI almost completely; 97% inhibition was achieved with the 90-mg dose, and 99% inhibition was achieved with the 150-mg dose.

Results showed that after a median follow-up of 1.8 years, there was a clear reduction in all bleeding endpoints with both doses of abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban.

Dr. Ruff explained that the trial was powered to detect differences in bleeding, not stroke, but the investigators approached this in an exploratory way.

“As expected, the numbers were low, with just 25 strokes (23 ischemic strokes) across all three groups in the trial. So, because of this very low rate, we are really not able to compare how abelacimab compares with rivaroxaban in reducing stroke,” he commented.

He did, however, suggest that the low stroke rate in the study was encouraging.

“If we look at the same population without anticoagulation, the stroke rate would be about 7% per year. And we see here in this trial that in all three arms, the stroke rate was just above 1% per year. I think this shows that all the patients in the trial were getting highly effective anticoagulation,” he said.

“But what this trial doesn’t answer – because the numbers are so low – is exactly how effective factor XI inhibition with abelacimab is, compared to NOACs in reducing stroke rates. That requires dedicated phase 3 trials.”

Dr. Ruff pointed out that there are some reassuring data from phase 2 trials in venous thromboembolism (VTE), in which the 150-mg dose of abelacimab was associated with an 80% reduction in VTE, compared with enoxaparin. “Historically in the development of anticoagulants, efficacy in VTE has translated into efficacy in stroke prevention, so that is very encouraging,” he commented.

“So, I think our results along with the VTE results are encouraging, but the precision regarding the relative efficacy compared to NOACs is still an open question that needs to be clarified in phase 3 trials,” he concluded.

Several phase 3 trials are now underway with abelacimab and two other small-molecule orally available factor XI inhibitors, milvexian (BMS/Janssen) and asundexian (Bayer).

The designated discussant of the AZALEA study at the AHA meeting, Manesh Patel. MD, Duke University, Durham, N.C., described the results as “an important step forward.”

“This trial, with the prior data in this field, show that factor XI inhibition as a target is biologically possible (studies showing > 95% inhibition), significantly less bleeding than NOACS. We await the phase 3 studies, but having significantly less bleeding and similar or less stroke would be a substantial step forward for the field,” he said.

John Alexander, MD, also from Duke University, said: “There were clinically important reductions in bleeding with both doses of abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban. This is consistent to what we’ve seen with comparisons between other factor XI inhibitors and other factor Xa inhibitors.”

On the exploratory efficacy results, Dr. Alexander agreed with Dr. Ruff that it was not possible to get any idea of how abelacimab compared with rivaroxaban in reducing stroke. “The hazard ratio and confidence intervals comparing abelacimab and rivaroxaban include substantial lower rates, no difference, and substantially higher rates,” he noted.

“We need to wait for the results of phase 3 trials, with abelacimab and other factor XI inhibitors, to understand how well factor XI inhibition prevents stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation,” Dr. Alexander added. “These trials are ongoing.”

Dr. Ruff concluded: “Assuming the data from ongoing phase 3 trials confirm the benefit of factor XI inhibitors for stroke prevention in people with AF, it will really be transformative for the field of cardiology.

“Our first mission in treating people with AF is to prevent stroke, and our ability to do this with a remarkably safe anticoagulant such as abelacimab would be an incredible advance,” he concluded.

Dr. Ruff receives research funding from Anthos for abelacimab trials, is on an AF executive committee for BMS/Janssen (milvexian), and has been on an advisory board for Bayer (asundexian). Dr. Patel has received grants from and acts as an advisor to Bayer and Janssen. Dr. Alexander receives research funding from Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AHA 2023

Most effective meds for alcohol use disorder flagged

TOPLINE:

In conjunction with psychosocial interventions, oral naltrexone and acamprosate are both effective first-line drug therapies for alcohol use disorder (AUD), results of a systematic review and meta-analysis found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated efficacy and comparative efficacy of three therapies for AUD that are approved in the United States (acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram) and six that are commonly used off-label (baclofen, gabapentin, varenicline, topiramate, prazosin, and ondansetron).

- Data came from 118 randomized clinical trials lasting at least 12 weeks with 20,976 participants.

- 74% of these studies included psychosocial co-interventions, and the primary outcome was alcohol consumption.

- Numbers needed to treat (NNT) were calculated for medications with at least moderate strength of evidence for benefit.

TAKEAWAY:

- Acamprosate (NNT = 11) and naltrexone (50 mg/day; NNT = 18) had the highest strength of evidence and were both associated with statistically significant improvement in drinking outcomes.

- Oral naltrexone but not acamprosate was also associated with lower rates of return to heavy drinking (NNT = 11), compared with placebo.

- Injectable naltrexone was not associated with return to any or heavy drinking but was associated with fewer drinking days over the 30-day treatment period (weighted mean difference, –4.99 days).

- The four trials that directly compared acamprosate with oral naltrexone did not consistently establish superiority of either medication for alcohol use outcomes, and among off-label drugs, only topiramate had moderate strength of evidence for benefit.

IN PRACTICE:

“Alcohol use disorder affects more than 28.3 million people in the United States and is associated with increased rates of morbidity and mortality. In conjunction with psychosocial interventions, these findings support the use of oral naltrexone, 50 mg/day, and acamprosate as first-line pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorder,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Melissa McPheeters, PhD, MPH, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, was published online in JAMA.

LIMITATIONS:

Most study participants had moderate to severe AUD, and the applicability of the findings to people with mild AUD is uncertain. The mean age of participants was typically between ages 40 and 49 years, and it’s unclear whether the medications have similar efficacy for older or younger age groups. Information on adverse effects was limited.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The authors have disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In conjunction with psychosocial interventions, oral naltrexone and acamprosate are both effective first-line drug therapies for alcohol use disorder (AUD), results of a systematic review and meta-analysis found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated efficacy and comparative efficacy of three therapies for AUD that are approved in the United States (acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram) and six that are commonly used off-label (baclofen, gabapentin, varenicline, topiramate, prazosin, and ondansetron).

- Data came from 118 randomized clinical trials lasting at least 12 weeks with 20,976 participants.

- 74% of these studies included psychosocial co-interventions, and the primary outcome was alcohol consumption.

- Numbers needed to treat (NNT) were calculated for medications with at least moderate strength of evidence for benefit.

TAKEAWAY:

- Acamprosate (NNT = 11) and naltrexone (50 mg/day; NNT = 18) had the highest strength of evidence and were both associated with statistically significant improvement in drinking outcomes.

- Oral naltrexone but not acamprosate was also associated with lower rates of return to heavy drinking (NNT = 11), compared with placebo.

- Injectable naltrexone was not associated with return to any or heavy drinking but was associated with fewer drinking days over the 30-day treatment period (weighted mean difference, –4.99 days).

- The four trials that directly compared acamprosate with oral naltrexone did not consistently establish superiority of either medication for alcohol use outcomes, and among off-label drugs, only topiramate had moderate strength of evidence for benefit.

IN PRACTICE:

“Alcohol use disorder affects more than 28.3 million people in the United States and is associated with increased rates of morbidity and mortality. In conjunction with psychosocial interventions, these findings support the use of oral naltrexone, 50 mg/day, and acamprosate as first-line pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorder,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Melissa McPheeters, PhD, MPH, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, was published online in JAMA.

LIMITATIONS:

Most study participants had moderate to severe AUD, and the applicability of the findings to people with mild AUD is uncertain. The mean age of participants was typically between ages 40 and 49 years, and it’s unclear whether the medications have similar efficacy for older or younger age groups. Information on adverse effects was limited.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The authors have disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In conjunction with psychosocial interventions, oral naltrexone and acamprosate are both effective first-line drug therapies for alcohol use disorder (AUD), results of a systematic review and meta-analysis found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated efficacy and comparative efficacy of three therapies for AUD that are approved in the United States (acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram) and six that are commonly used off-label (baclofen, gabapentin, varenicline, topiramate, prazosin, and ondansetron).

- Data came from 118 randomized clinical trials lasting at least 12 weeks with 20,976 participants.

- 74% of these studies included psychosocial co-interventions, and the primary outcome was alcohol consumption.

- Numbers needed to treat (NNT) were calculated for medications with at least moderate strength of evidence for benefit.

TAKEAWAY:

- Acamprosate (NNT = 11) and naltrexone (50 mg/day; NNT = 18) had the highest strength of evidence and were both associated with statistically significant improvement in drinking outcomes.

- Oral naltrexone but not acamprosate was also associated with lower rates of return to heavy drinking (NNT = 11), compared with placebo.

- Injectable naltrexone was not associated with return to any or heavy drinking but was associated with fewer drinking days over the 30-day treatment period (weighted mean difference, –4.99 days).

- The four trials that directly compared acamprosate with oral naltrexone did not consistently establish superiority of either medication for alcohol use outcomes, and among off-label drugs, only topiramate had moderate strength of evidence for benefit.

IN PRACTICE:

“Alcohol use disorder affects more than 28.3 million people in the United States and is associated with increased rates of morbidity and mortality. In conjunction with psychosocial interventions, these findings support the use of oral naltrexone, 50 mg/day, and acamprosate as first-line pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorder,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Melissa McPheeters, PhD, MPH, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, was published online in JAMA.

LIMITATIONS:

Most study participants had moderate to severe AUD, and the applicability of the findings to people with mild AUD is uncertain. The mean age of participants was typically between ages 40 and 49 years, and it’s unclear whether the medications have similar efficacy for older or younger age groups. Information on adverse effects was limited.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The authors have disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Atrial fibrillation linked to dementia, especially when diagnosed before age 65 years

TOPLINE:

Adults with atrial fibrillation (AFib) are at increased risk for dementia, especially when AFib occurs before age 65 years, new research shows. Investigators note the findings highlight the importance of monitoring cognitive function in adults with AF.

METHODOLOGY:

- This prospective, population-based cohort study leveraged data from 433,746 UK Biobank participants (55% women), including 30,601 with AFib, who were followed for a median of 12.6 years

- Incident cases of dementia were determined through linkage from multiple databases.

- Cox proportional hazards models and propensity score matching were used to estimate the association between age at onset of AFib and incident dementia.

TAKEAWAY:

- During follow-up, new-onset dementia occurred in 5,898 participants (2,546 with Alzheimer’s disease [AD] and 1,211 with vascular dementia [VD]), of which, 1,031 had AFib (350 with AD; 320 with VD).

- Compared with participants without AFib, those with AFib had a 42% higher risk for all-cause dementia (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.42; P < .001) and more than double the risk for VD (aHR, 2.06; P < .001), but no significantly higher risk for AD.

- Younger age at AFib onset was associated with higher risks for all-cause dementia, AD and VD, with aHRs per 10-year decrease of 1.23, 1.27, and 1.35, respectively (P < .001 for all).

- After propensity score matching, AFib onset before age 65 years had the highest risk for all-cause dementia (aHR, 1.82; P < .001), followed by AF onset at age 65-74 years (aHR, 1.47; P < .001). Similar results were seen in AD and VD.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings indicate that careful monitoring of cognitive function for patients with a younger [AFib] onset age, particularly those diagnosed with [AFib] before age 65 years, is important to attenuate the risk of subsequent dementia,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Wenya Zhang, with the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Because the study was observational, a cause-effect relationship cannot be established. Despite the adjustment for many underlying confounders, residual unidentified confounders may still exist. The vast majority of participants were White. The analyses did not consider the potential impact of effective treatment of AFib on dementia risk.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no commercial funding. The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adults with atrial fibrillation (AFib) are at increased risk for dementia, especially when AFib occurs before age 65 years, new research shows. Investigators note the findings highlight the importance of monitoring cognitive function in adults with AF.

METHODOLOGY:

- This prospective, population-based cohort study leveraged data from 433,746 UK Biobank participants (55% women), including 30,601 with AFib, who were followed for a median of 12.6 years

- Incident cases of dementia were determined through linkage from multiple databases.

- Cox proportional hazards models and propensity score matching were used to estimate the association between age at onset of AFib and incident dementia.

TAKEAWAY:

- During follow-up, new-onset dementia occurred in 5,898 participants (2,546 with Alzheimer’s disease [AD] and 1,211 with vascular dementia [VD]), of which, 1,031 had AFib (350 with AD; 320 with VD).

- Compared with participants without AFib, those with AFib had a 42% higher risk for all-cause dementia (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.42; P < .001) and more than double the risk for VD (aHR, 2.06; P < .001), but no significantly higher risk for AD.

- Younger age at AFib onset was associated with higher risks for all-cause dementia, AD and VD, with aHRs per 10-year decrease of 1.23, 1.27, and 1.35, respectively (P < .001 for all).

- After propensity score matching, AFib onset before age 65 years had the highest risk for all-cause dementia (aHR, 1.82; P < .001), followed by AF onset at age 65-74 years (aHR, 1.47; P < .001). Similar results were seen in AD and VD.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings indicate that careful monitoring of cognitive function for patients with a younger [AFib] onset age, particularly those diagnosed with [AFib] before age 65 years, is important to attenuate the risk of subsequent dementia,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Wenya Zhang, with the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Because the study was observational, a cause-effect relationship cannot be established. Despite the adjustment for many underlying confounders, residual unidentified confounders may still exist. The vast majority of participants were White. The analyses did not consider the potential impact of effective treatment of AFib on dementia risk.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no commercial funding. The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adults with atrial fibrillation (AFib) are at increased risk for dementia, especially when AFib occurs before age 65 years, new research shows. Investigators note the findings highlight the importance of monitoring cognitive function in adults with AF.

METHODOLOGY:

- This prospective, population-based cohort study leveraged data from 433,746 UK Biobank participants (55% women), including 30,601 with AFib, who were followed for a median of 12.6 years

- Incident cases of dementia were determined through linkage from multiple databases.

- Cox proportional hazards models and propensity score matching were used to estimate the association between age at onset of AFib and incident dementia.

TAKEAWAY:

- During follow-up, new-onset dementia occurred in 5,898 participants (2,546 with Alzheimer’s disease [AD] and 1,211 with vascular dementia [VD]), of which, 1,031 had AFib (350 with AD; 320 with VD).

- Compared with participants without AFib, those with AFib had a 42% higher risk for all-cause dementia (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.42; P < .001) and more than double the risk for VD (aHR, 2.06; P < .001), but no significantly higher risk for AD.

- Younger age at AFib onset was associated with higher risks for all-cause dementia, AD and VD, with aHRs per 10-year decrease of 1.23, 1.27, and 1.35, respectively (P < .001 for all).

- After propensity score matching, AFib onset before age 65 years had the highest risk for all-cause dementia (aHR, 1.82; P < .001), followed by AF onset at age 65-74 years (aHR, 1.47; P < .001). Similar results were seen in AD and VD.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings indicate that careful monitoring of cognitive function for patients with a younger [AFib] onset age, particularly those diagnosed with [AFib] before age 65 years, is important to attenuate the risk of subsequent dementia,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Wenya Zhang, with the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Because the study was observational, a cause-effect relationship cannot be established. Despite the adjustment for many underlying confounders, residual unidentified confounders may still exist. The vast majority of participants were White. The analyses did not consider the potential impact of effective treatment of AFib on dementia risk.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no commercial funding. The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Breakthroughs in the prevention of RSV disease among infants

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a negative-sense, single-stranded, ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus that is a member of Pneumoviridae family. Two subtypes, A and B, and multiple genotypes circulate during fall and winter seasonal outbreaks of RSV.1 RSV can cause severe lower respiratory tract disease including bronchiolitis, pneumonia, respiratory failure, and death. Each year, RSV disease causes the hospitalization of 1.5% to 2% of children younger than 6 months of age, resulting in 100 to 300 deaths.2 For infants younger than 1 year, RSV infection is the leading cause of hospitalization.3 In 2023, two new treatments have become available to prevent RSV disease: nirsevimab and RSVPreF vaccine.

Nirsevimab

Nirsevimab is an antibody to an RSV antigen. It has a long half-life and is approved for administration to infants, providing passive immunization. In contrast, administration of the RSVPreF vaccine to pregnant persons elicits active maternal immunity, resulting in the production of anti-RSV antibodies that are transferred to the fetus, resulting in passive immunity in the infant. Seasonal administration of nirsevimab and the RSV vaccine maximizes benefit to the infant and conserves limited health care resources. In temperate regions in the United States, the RSV infection season typically begins in October and peaks in December through mid-February and ends in April or May.4,5 In southern Florida, the RSV season often begins in August to September, peaks in November through December, and ends in March.4,5

This editorial reviews 3 strategies for prevention of RSV infection in infants, including:

- universal treatment of newborns with nirsevimab

- immunization of pregnant persons with an RSVpreF vaccine in the third trimester appropriately timed to occur just before the beginning or during RSV infection season

- prioritizing universal maternal RSV vaccination with reflex administration of nirsevimab to newborns when the pregnant person was not vaccinated.6

Of note, there are no studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of combining RSVpreF vaccine and nirsevimab. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not recommend combining both RSV vaccination of pregnant persons plus nirsevimab treatment of the infant, except in limited circumstances, such as for immunocompromised pregnant people with limited antibody production or newborns who have a massive transfusion, which dilutes antibody titres.6

RSV prevention strategy 1

Universal treatment of newborns and infants with nirsevimab

Nirsevimab (Beyfortus, Sanofi and AstraZeneca) is an IgG 1-kappa monoclonal antibody with a long half-life that targets the prefusion conformation of the RSV F-protein, resulting in passive immunity to infection.7 Passive immunization results in rapid protection against infection because it does not require activation of the immune system. Nirsevimab is long acting due to amino acid substitutions in the Fc region, increasing binding to the neonatal Fc receptor, which protects IgG antibodies from degradation, thereby extending the antibody half-life. The terminal halflife of nirsevimab is 71 days, and the duration of protection following a single dose is at least 5 months.

Nirsevimab is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for all neonates and infants born or entering their first RSV infection season and for children up to 24 months of age who are vulnerable to severe RSV during their second RSV infection season. For infants born outside the RSV infection season, nirsevimab should be administered once prior to the start of the next RSV infection season.7 Nirsevimab is administered as a single intramuscular injection at a dose of 50 mg for neonates and infants < 5 kg in weight and a dose of 100 mg for neonates and infants ≥ 5 kg in weight.7 The list average wholesale price for both doses is $594.8 Nirsevimab is contraindicated for patients with a serious hypersensitivity reaction to nirsevimab or its excipients.7 In clinical trials, adverse reactions including rash and injection site reaction were reported in 1.2% of participants.7 Some RSV variants may be resistant to neutralization with nirsevimab.7,9

In a randomized clinical trial, 1,490 infants born ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation, the rates of medically-attended RSV lower respiratory tract disease (MA RSV LRTD) through 150 days of follow-up in the placebo and nirsevimab groups were 5.0% and 1.2%, respectively (P < .001).7,10 Compared with placebo, nirsevimab reduced hospitalizations due to RSV LRTD by 60% through 150 days of follow up. In a randomized clinical trial enrolling 1,453 infants born between 29 weeks’ and < 35 weeks’ gestation, the rates of MA RSV LRTD through 150 days of follow up in the placebo and nirsevimab groups were 9.5% and 2.6%, respectively (P < .001). In this study of infants born preterm, compared with placebo, nirsevimab reduced hospitalization due to RSV LRTD by 70% through 150 days of follow up.7 Nirsevimab is thought to be cost-effective at the current price per dose, but more data are needed to precisely define the magnitude of the health care savings associated with universal nirsevimab administration.11-13 The CDC reports that the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) of nirsevimab administration to infants is approximately $250,000, given an estimated cost of $500 for one dose of vaccine.14

Universal passive vaccination of newborns is recommended by many state departments of public health, which can provide the vaccine without cost to clinicians and health care facilities participating in the children’s vaccination program.

Continue to: RSV prevention strategy 2...

RSV prevention strategy 2

Universal RSV vaccination of pregnant persons from September through January

The RSVpreF vaccine (Abryvso, Pfizer) is approved by the FDA for the active immunization of pregnant persons between 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation for the prevention of RSV LRTD in infants from birth through 6 months of age.15 Administration of the RSVpreF vaccine to pregnant people elicits the formation of antiRSV antibodies that are transferred transplacentally to the fetus, resulting in the protection of the infant from RSV during the first 6 months of life. The RSVpreF vaccine also is approved to prevent RSV LRTD in people aged ≥ 60 years.

The RSVpreF vaccine contains the prefusion form of the RSV fusion (F) protein responsible for viral entry into host cells. The vaccine contains 60 µg of both RSV preF A and preF B recombinant proteins. The vaccine is administered as a single intramuscular dose in a volume of 0.5 mL. The vaccine is provided in a vial in a lyophilized form and must be reconstituted prior to administration. The average wholesale price of RSVPreF vaccine is $354.16 The vaccine is contraindicated for people who have had an allergic reaction to any component of the vaccine. The most commonly reported adverse reaction is injection site pain (41%).15 The FDA reports a “numerical imbalance in preterm births in Abrysvo recipients compared to placebo recipients” (5.7% vs 4.7%), and “available data are insufficient to establish or exclude a causal relationship between preterm birth and Abrysvo.”15 In rabbits there is no evidence of developmental toxicity and congenital anomalies associated with the RSVpreF vaccine. In human studies, no differences in the rate of congenital anomalies or fetal deaths were noted between RSVpreF vaccine and placebo.

In a clinical trial, 6,975 pregnant participants 24 through 36 weeks’ gestation were randomly assigned to receive a placebo or the RSVpreF vaccine.15,17 After birth, follow-up of infants at 180 days, showed that the rates of MA RSV LRTD among the infants in the placebo and RSVpreF vaccine groups were 3.4% and 1.6%, respectively. At 180 days, the reported rates of severe RSV LRTD in the placebo and RSVpreF vaccine groups were 1.8% and 0.5%, respectively. In this study, among the subset of pregnant participants who received the RSVpreF vaccine (n = 1,572) or placebo (n = 1,539) at 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation, the rates of MA RSV LRTD among the infants in the placebo and RSVpreF vaccine groups were 3.6% and 1.5%, respectively. In the subset of pregnant participants vaccinated at 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation, at 180 days postvaccination, the reported rates of severe RSV LRTD in the placebo and RSVpreF vaccine groups were 1.6% and 0.4%, respectively.15

The CDC has recommended that the RSVpreF vaccine be administered to pregnant people 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation from September through the end of January in most of the continental United States to reduce the rate of RSV LRTD in infants.6 September was selected because it is 1 to 2 months before the start of the RSV season, and it takes at least 14 days for maternal vaccination to result in transplacental transfer of protective antibodies to the fetus. January was selected because it is 2 to 3 months before the anticipated end of the RSV season.6 The CDC also noted that, for regions with a different pattern of RSV seasonality, clinicians should follow the guidance of local public health officials. This applies to the states of Alaska, southern Florida, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.6 The CDC recommended that infants born < 34 weeks’ gestation should receive nirsevimab.6

Maternal RSV vaccination is thought to be cost-effective for reducing RSV LRTD in infants. However, the cost-effectiveness analyses are sensitive to the pricing of the two main options: maternal RSV vaccination and nirsevimab.

It is estimated that nirsevimab may provide greater protection than maternal RSV vaccination from RSV LRTD, but the maternal RSVpreF vaccine is priced lower than nirsevimab.18 Focusing administration of RSVpreF vaccine from September through January of the RSV infection season is thought to maximize benefits to infants and reduce total cost of the vaccination program.19 With year-round RSVpreF vaccine dosing, the estimated ICER per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) is approximately $400,000, whereas seasonal dosing reduces the cost to approximately $170,000.19

RSV prevention strategy 3

Vaccinate pregnant persons; reflex to newborn treatment with nirsevimab if maternal RSV vaccination did not occur

RSVpreF vaccination to all pregnant persons 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation during RSV infection season is not likely to result in 100% adherence. For instance, in a CDC-conducted survey only 47% of pregnant persons received an influenza vaccine.2 Newborns whose mothers did not receive an RSVpreF vaccine will need to be considered for treatment with nirsevimab. Collaboration and communication among obstetricians and pediatricians will be needed to avoid miscommunication and missed opportunities to treat newborns during the birth hospitalization. Enhancements in electronic health records, linking the mother’s vaccination record with the newborn’s medical record plus an added feature of electronic alerts when the mother did not receive an appropriately timed RSVpreF vaccine would improve the communication of important clinical information to the pediatrician.

Next steps for the upcoming peak RSV season

We are currently in the 2023–2024 RSV infection season and can expect a peak in cases of RSV between December 2023 and February 2024. The CDC recommends protecting all infants against RSV-associated LRTD. The options are to administer the maternal RSVpreF vaccine to pregnant persons or treating the infant with nirsevimab. The vaccine is just now becoming available for administration in regional pharmacies, physician practices, and health systems. Obstetrician-gynecologists should follow the recommendation of their state department of public health. As noted above, many state departments of public health are recommending that all newborns receive nirsevimab. For clinicians in those states, RSVPreF vaccination of pregnant persons is not a priority. ●

- Tramuto F, Massimo Maida C, Mazzucco W, et al. Molecular epidemiology and genetic diversity of human respiratory syncytial virus in Sicily during pre- and post-COVID-19 surveillance season. Pathogens. 2023;12:1099.

- Boudreau M, Vadlamudi NK, Bastien N, et al. Pediatric RSV-associated hospitalizations before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2336863.

- Leader S, Kohlhase K. Recent trends in severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) among US infants, 1997 to 2000. J Pediatr. 2003;143(5 Suppl):S127-132.

- Hamid S, Winn A, Parikh R, et al. Seasonality of respiratory syncytial virus-United States 2017-2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:355-361.

- Rose EB, Wheatley A, Langley G, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus seasonality-United States 2014-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:71-76.

- Fleming-Dutra KE, Jones JM, Roper LE, et al. Use of Pfizer respiratory syncytial virus vaccine during pregnancy for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus associated lower respiratory tract disease in infants: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices- United States 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. October 6, 2023. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr /mm7241e1.htm#print

- FDA package insert for Beyfortus. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov /drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/761328s000lbl.pdf

- Lexicomp. Nirsevimab: Drug information – UpToDate. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://www. wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/lexicomp

- Ahani B, Tuffy KM, Aksyuk A, et al. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of RSV infections in infants during two nirsevimab randomized clinical trials. Nat Commun. 2023;14:4347.

- Hammitt LL, Dagan R, Yuan Y, et al. Nirsevimab for prevention of RSV in late-preterm and term infants. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:837-846.

- Li X, Bilcke J, Vazquez-Fernandez L, et al. Costeffectiveness of respiratory syncytial virus disease protection strategies: maternal vaccine versus seasonal or year-round monoclonal antibody program in Norwegian children. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(Suppl 1):S95-S101.

- Hodgson D, Koltai M, Krauer F, et al. Optimal respiratory syncytial virus intervention programmes using nirsevimab in England and Wales. Vaccine. 2022;40:7151-7157.

- Yu T, Padula WV, Yieh L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of nirsevimab and palivizumab for respiratory syncytial virus prophylaxis in preterm infants 29-34 6/7 weeks’ gestation in the United States. Pediatr Neonatal. 2023;04:015.

- Jones J. Evidence to recommendations framework: nirsevimab in infants. Accessed October 27, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meet ings/downloads/slides-2023-02/slides-02-23/rsv -pediatric-04-jones-508.pdf

- Abrysvo [package insert]. Pfizer; New York, New York. August 2023.

- Lexicomp. Recombinant respiratory syncytial virus vaccine (RSVPreF) (Abrysvo): Drug information - UpToDate. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions /lexicomp

- Kampmann B, Madhi SA, Munjal I, et al. Bivalent prefusion F vaccine in pregnancy to prevent RSV illness in infants. N Engl J Med. 2023;388: 1451-1464.

- Baral R, Higgins D, Regan K, et al. Impact and costeffectiveness of potential interventions against infant respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in 131 lowincome and middle-income countries using a static cohort model. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046563.

- Fleming-Dutra KE. Evidence to recommendations framework updates: Pfizer maternal RSVpreF vaccine. June 22, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2023. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip /meetings/downloads/slides-2023-06-21-23/03 -RSV-Mat-Ped-Fleming-Dutra-508.pdf

- Razzaghi H, Kahn KE, Calhoun K, et al. Influenza, Tdap and COVID-19 vaccination coverage and hesitancy among pregnant women-United States, April 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a negative-sense, single-stranded, ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus that is a member of Pneumoviridae family. Two subtypes, A and B, and multiple genotypes circulate during fall and winter seasonal outbreaks of RSV.1 RSV can cause severe lower respiratory tract disease including bronchiolitis, pneumonia, respiratory failure, and death. Each year, RSV disease causes the hospitalization of 1.5% to 2% of children younger than 6 months of age, resulting in 100 to 300 deaths.2 For infants younger than 1 year, RSV infection is the leading cause of hospitalization.3 In 2023, two new treatments have become available to prevent RSV disease: nirsevimab and RSVPreF vaccine.

Nirsevimab

Nirsevimab is an antibody to an RSV antigen. It has a long half-life and is approved for administration to infants, providing passive immunization. In contrast, administration of the RSVPreF vaccine to pregnant persons elicits active maternal immunity, resulting in the production of anti-RSV antibodies that are transferred to the fetus, resulting in passive immunity in the infant. Seasonal administration of nirsevimab and the RSV vaccine maximizes benefit to the infant and conserves limited health care resources. In temperate regions in the United States, the RSV infection season typically begins in October and peaks in December through mid-February and ends in April or May.4,5 In southern Florida, the RSV season often begins in August to September, peaks in November through December, and ends in March.4,5

This editorial reviews 3 strategies for prevention of RSV infection in infants, including:

- universal treatment of newborns with nirsevimab

- immunization of pregnant persons with an RSVpreF vaccine in the third trimester appropriately timed to occur just before the beginning or during RSV infection season

- prioritizing universal maternal RSV vaccination with reflex administration of nirsevimab to newborns when the pregnant person was not vaccinated.6

Of note, there are no studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of combining RSVpreF vaccine and nirsevimab. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not recommend combining both RSV vaccination of pregnant persons plus nirsevimab treatment of the infant, except in limited circumstances, such as for immunocompromised pregnant people with limited antibody production or newborns who have a massive transfusion, which dilutes antibody titres.6

RSV prevention strategy 1

Universal treatment of newborns and infants with nirsevimab

Nirsevimab (Beyfortus, Sanofi and AstraZeneca) is an IgG 1-kappa monoclonal antibody with a long half-life that targets the prefusion conformation of the RSV F-protein, resulting in passive immunity to infection.7 Passive immunization results in rapid protection against infection because it does not require activation of the immune system. Nirsevimab is long acting due to amino acid substitutions in the Fc region, increasing binding to the neonatal Fc receptor, which protects IgG antibodies from degradation, thereby extending the antibody half-life. The terminal halflife of nirsevimab is 71 days, and the duration of protection following a single dose is at least 5 months.

Nirsevimab is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for all neonates and infants born or entering their first RSV infection season and for children up to 24 months of age who are vulnerable to severe RSV during their second RSV infection season. For infants born outside the RSV infection season, nirsevimab should be administered once prior to the start of the next RSV infection season.7 Nirsevimab is administered as a single intramuscular injection at a dose of 50 mg for neonates and infants < 5 kg in weight and a dose of 100 mg for neonates and infants ≥ 5 kg in weight.7 The list average wholesale price for both doses is $594.8 Nirsevimab is contraindicated for patients with a serious hypersensitivity reaction to nirsevimab or its excipients.7 In clinical trials, adverse reactions including rash and injection site reaction were reported in 1.2% of participants.7 Some RSV variants may be resistant to neutralization with nirsevimab.7,9

In a randomized clinical trial, 1,490 infants born ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation, the rates of medically-attended RSV lower respiratory tract disease (MA RSV LRTD) through 150 days of follow-up in the placebo and nirsevimab groups were 5.0% and 1.2%, respectively (P < .001).7,10 Compared with placebo, nirsevimab reduced hospitalizations due to RSV LRTD by 60% through 150 days of follow up. In a randomized clinical trial enrolling 1,453 infants born between 29 weeks’ and < 35 weeks’ gestation, the rates of MA RSV LRTD through 150 days of follow up in the placebo and nirsevimab groups were 9.5% and 2.6%, respectively (P < .001). In this study of infants born preterm, compared with placebo, nirsevimab reduced hospitalization due to RSV LRTD by 70% through 150 days of follow up.7 Nirsevimab is thought to be cost-effective at the current price per dose, but more data are needed to precisely define the magnitude of the health care savings associated with universal nirsevimab administration.11-13 The CDC reports that the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) of nirsevimab administration to infants is approximately $250,000, given an estimated cost of $500 for one dose of vaccine.14

Universal passive vaccination of newborns is recommended by many state departments of public health, which can provide the vaccine without cost to clinicians and health care facilities participating in the children’s vaccination program.

Continue to: RSV prevention strategy 2...

RSV prevention strategy 2

Universal RSV vaccination of pregnant persons from September through January

The RSVpreF vaccine (Abryvso, Pfizer) is approved by the FDA for the active immunization of pregnant persons between 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation for the prevention of RSV LRTD in infants from birth through 6 months of age.15 Administration of the RSVpreF vaccine to pregnant people elicits the formation of antiRSV antibodies that are transferred transplacentally to the fetus, resulting in the protection of the infant from RSV during the first 6 months of life. The RSVpreF vaccine also is approved to prevent RSV LRTD in people aged ≥ 60 years.

The RSVpreF vaccine contains the prefusion form of the RSV fusion (F) protein responsible for viral entry into host cells. The vaccine contains 60 µg of both RSV preF A and preF B recombinant proteins. The vaccine is administered as a single intramuscular dose in a volume of 0.5 mL. The vaccine is provided in a vial in a lyophilized form and must be reconstituted prior to administration. The average wholesale price of RSVPreF vaccine is $354.16 The vaccine is contraindicated for people who have had an allergic reaction to any component of the vaccine. The most commonly reported adverse reaction is injection site pain (41%).15 The FDA reports a “numerical imbalance in preterm births in Abrysvo recipients compared to placebo recipients” (5.7% vs 4.7%), and “available data are insufficient to establish or exclude a causal relationship between preterm birth and Abrysvo.”15 In rabbits there is no evidence of developmental toxicity and congenital anomalies associated with the RSVpreF vaccine. In human studies, no differences in the rate of congenital anomalies or fetal deaths were noted between RSVpreF vaccine and placebo.

In a clinical trial, 6,975 pregnant participants 24 through 36 weeks’ gestation were randomly assigned to receive a placebo or the RSVpreF vaccine.15,17 After birth, follow-up of infants at 180 days, showed that the rates of MA RSV LRTD among the infants in the placebo and RSVpreF vaccine groups were 3.4% and 1.6%, respectively. At 180 days, the reported rates of severe RSV LRTD in the placebo and RSVpreF vaccine groups were 1.8% and 0.5%, respectively. In this study, among the subset of pregnant participants who received the RSVpreF vaccine (n = 1,572) or placebo (n = 1,539) at 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation, the rates of MA RSV LRTD among the infants in the placebo and RSVpreF vaccine groups were 3.6% and 1.5%, respectively. In the subset of pregnant participants vaccinated at 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation, at 180 days postvaccination, the reported rates of severe RSV LRTD in the placebo and RSVpreF vaccine groups were 1.6% and 0.4%, respectively.15

The CDC has recommended that the RSVpreF vaccine be administered to pregnant people 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation from September through the end of January in most of the continental United States to reduce the rate of RSV LRTD in infants.6 September was selected because it is 1 to 2 months before the start of the RSV season, and it takes at least 14 days for maternal vaccination to result in transplacental transfer of protective antibodies to the fetus. January was selected because it is 2 to 3 months before the anticipated end of the RSV season.6 The CDC also noted that, for regions with a different pattern of RSV seasonality, clinicians should follow the guidance of local public health officials. This applies to the states of Alaska, southern Florida, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.6 The CDC recommended that infants born < 34 weeks’ gestation should receive nirsevimab.6

Maternal RSV vaccination is thought to be cost-effective for reducing RSV LRTD in infants. However, the cost-effectiveness analyses are sensitive to the pricing of the two main options: maternal RSV vaccination and nirsevimab.

It is estimated that nirsevimab may provide greater protection than maternal RSV vaccination from RSV LRTD, but the maternal RSVpreF vaccine is priced lower than nirsevimab.18 Focusing administration of RSVpreF vaccine from September through January of the RSV infection season is thought to maximize benefits to infants and reduce total cost of the vaccination program.19 With year-round RSVpreF vaccine dosing, the estimated ICER per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) is approximately $400,000, whereas seasonal dosing reduces the cost to approximately $170,000.19

RSV prevention strategy 3

Vaccinate pregnant persons; reflex to newborn treatment with nirsevimab if maternal RSV vaccination did not occur

RSVpreF vaccination to all pregnant persons 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation during RSV infection season is not likely to result in 100% adherence. For instance, in a CDC-conducted survey only 47% of pregnant persons received an influenza vaccine.2 Newborns whose mothers did not receive an RSVpreF vaccine will need to be considered for treatment with nirsevimab. Collaboration and communication among obstetricians and pediatricians will be needed to avoid miscommunication and missed opportunities to treat newborns during the birth hospitalization. Enhancements in electronic health records, linking the mother’s vaccination record with the newborn’s medical record plus an added feature of electronic alerts when the mother did not receive an appropriately timed RSVpreF vaccine would improve the communication of important clinical information to the pediatrician.

Next steps for the upcoming peak RSV season

We are currently in the 2023–2024 RSV infection season and can expect a peak in cases of RSV between December 2023 and February 2024. The CDC recommends protecting all infants against RSV-associated LRTD. The options are to administer the maternal RSVpreF vaccine to pregnant persons or treating the infant with nirsevimab. The vaccine is just now becoming available for administration in regional pharmacies, physician practices, and health systems. Obstetrician-gynecologists should follow the recommendation of their state department of public health. As noted above, many state departments of public health are recommending that all newborns receive nirsevimab. For clinicians in those states, RSVPreF vaccination of pregnant persons is not a priority. ●

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a negative-sense, single-stranded, ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus that is a member of Pneumoviridae family. Two subtypes, A and B, and multiple genotypes circulate during fall and winter seasonal outbreaks of RSV.1 RSV can cause severe lower respiratory tract disease including bronchiolitis, pneumonia, respiratory failure, and death. Each year, RSV disease causes the hospitalization of 1.5% to 2% of children younger than 6 months of age, resulting in 100 to 300 deaths.2 For infants younger than 1 year, RSV infection is the leading cause of hospitalization.3 In 2023, two new treatments have become available to prevent RSV disease: nirsevimab and RSVPreF vaccine.

Nirsevimab

Nirsevimab is an antibody to an RSV antigen. It has a long half-life and is approved for administration to infants, providing passive immunization. In contrast, administration of the RSVPreF vaccine to pregnant persons elicits active maternal immunity, resulting in the production of anti-RSV antibodies that are transferred to the fetus, resulting in passive immunity in the infant. Seasonal administration of nirsevimab and the RSV vaccine maximizes benefit to the infant and conserves limited health care resources. In temperate regions in the United States, the RSV infection season typically begins in October and peaks in December through mid-February and ends in April or May.4,5 In southern Florida, the RSV season often begins in August to September, peaks in November through December, and ends in March.4,5

This editorial reviews 3 strategies for prevention of RSV infection in infants, including:

- universal treatment of newborns with nirsevimab

- immunization of pregnant persons with an RSVpreF vaccine in the third trimester appropriately timed to occur just before the beginning or during RSV infection season

- prioritizing universal maternal RSV vaccination with reflex administration of nirsevimab to newborns when the pregnant person was not vaccinated.6

Of note, there are no studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of combining RSVpreF vaccine and nirsevimab. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not recommend combining both RSV vaccination of pregnant persons plus nirsevimab treatment of the infant, except in limited circumstances, such as for immunocompromised pregnant people with limited antibody production or newborns who have a massive transfusion, which dilutes antibody titres.6

RSV prevention strategy 1

Universal treatment of newborns and infants with nirsevimab

Nirsevimab (Beyfortus, Sanofi and AstraZeneca) is an IgG 1-kappa monoclonal antibody with a long half-life that targets the prefusion conformation of the RSV F-protein, resulting in passive immunity to infection.7 Passive immunization results in rapid protection against infection because it does not require activation of the immune system. Nirsevimab is long acting due to amino acid substitutions in the Fc region, increasing binding to the neonatal Fc receptor, which protects IgG antibodies from degradation, thereby extending the antibody half-life. The terminal halflife of nirsevimab is 71 days, and the duration of protection following a single dose is at least 5 months.

Nirsevimab is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for all neonates and infants born or entering their first RSV infection season and for children up to 24 months of age who are vulnerable to severe RSV during their second RSV infection season. For infants born outside the RSV infection season, nirsevimab should be administered once prior to the start of the next RSV infection season.7 Nirsevimab is administered as a single intramuscular injection at a dose of 50 mg for neonates and infants < 5 kg in weight and a dose of 100 mg for neonates and infants ≥ 5 kg in weight.7 The list average wholesale price for both doses is $594.8 Nirsevimab is contraindicated for patients with a serious hypersensitivity reaction to nirsevimab or its excipients.7 In clinical trials, adverse reactions including rash and injection site reaction were reported in 1.2% of participants.7 Some RSV variants may be resistant to neutralization with nirsevimab.7,9

In a randomized clinical trial, 1,490 infants born ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation, the rates of medically-attended RSV lower respiratory tract disease (MA RSV LRTD) through 150 days of follow-up in the placebo and nirsevimab groups were 5.0% and 1.2%, respectively (P < .001).7,10 Compared with placebo, nirsevimab reduced hospitalizations due to RSV LRTD by 60% through 150 days of follow up. In a randomized clinical trial enrolling 1,453 infants born between 29 weeks’ and < 35 weeks’ gestation, the rates of MA RSV LRTD through 150 days of follow up in the placebo and nirsevimab groups were 9.5% and 2.6%, respectively (P < .001). In this study of infants born preterm, compared with placebo, nirsevimab reduced hospitalization due to RSV LRTD by 70% through 150 days of follow up.7 Nirsevimab is thought to be cost-effective at the current price per dose, but more data are needed to precisely define the magnitude of the health care savings associated with universal nirsevimab administration.11-13 The CDC reports that the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) of nirsevimab administration to infants is approximately $250,000, given an estimated cost of $500 for one dose of vaccine.14

Universal passive vaccination of newborns is recommended by many state departments of public health, which can provide the vaccine without cost to clinicians and health care facilities participating in the children’s vaccination program.

Continue to: RSV prevention strategy 2...

RSV prevention strategy 2

Universal RSV vaccination of pregnant persons from September through January

The RSVpreF vaccine (Abryvso, Pfizer) is approved by the FDA for the active immunization of pregnant persons between 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation for the prevention of RSV LRTD in infants from birth through 6 months of age.15 Administration of the RSVpreF vaccine to pregnant people elicits the formation of antiRSV antibodies that are transferred transplacentally to the fetus, resulting in the protection of the infant from RSV during the first 6 months of life. The RSVpreF vaccine also is approved to prevent RSV LRTD in people aged ≥ 60 years.

The RSVpreF vaccine contains the prefusion form of the RSV fusion (F) protein responsible for viral entry into host cells. The vaccine contains 60 µg of both RSV preF A and preF B recombinant proteins. The vaccine is administered as a single intramuscular dose in a volume of 0.5 mL. The vaccine is provided in a vial in a lyophilized form and must be reconstituted prior to administration. The average wholesale price of RSVPreF vaccine is $354.16 The vaccine is contraindicated for people who have had an allergic reaction to any component of the vaccine. The most commonly reported adverse reaction is injection site pain (41%).15 The FDA reports a “numerical imbalance in preterm births in Abrysvo recipients compared to placebo recipients” (5.7% vs 4.7%), and “available data are insufficient to establish or exclude a causal relationship between preterm birth and Abrysvo.”15 In rabbits there is no evidence of developmental toxicity and congenital anomalies associated with the RSVpreF vaccine. In human studies, no differences in the rate of congenital anomalies or fetal deaths were noted between RSVpreF vaccine and placebo.

In a clinical trial, 6,975 pregnant participants 24 through 36 weeks’ gestation were randomly assigned to receive a placebo or the RSVpreF vaccine.15,17 After birth, follow-up of infants at 180 days, showed that the rates of MA RSV LRTD among the infants in the placebo and RSVpreF vaccine groups were 3.4% and 1.6%, respectively. At 180 days, the reported rates of severe RSV LRTD in the placebo and RSVpreF vaccine groups were 1.8% and 0.5%, respectively. In this study, among the subset of pregnant participants who received the RSVpreF vaccine (n = 1,572) or placebo (n = 1,539) at 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation, the rates of MA RSV LRTD among the infants in the placebo and RSVpreF vaccine groups were 3.6% and 1.5%, respectively. In the subset of pregnant participants vaccinated at 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation, at 180 days postvaccination, the reported rates of severe RSV LRTD in the placebo and RSVpreF vaccine groups were 1.6% and 0.4%, respectively.15

The CDC has recommended that the RSVpreF vaccine be administered to pregnant people 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation from September through the end of January in most of the continental United States to reduce the rate of RSV LRTD in infants.6 September was selected because it is 1 to 2 months before the start of the RSV season, and it takes at least 14 days for maternal vaccination to result in transplacental transfer of protective antibodies to the fetus. January was selected because it is 2 to 3 months before the anticipated end of the RSV season.6 The CDC also noted that, for regions with a different pattern of RSV seasonality, clinicians should follow the guidance of local public health officials. This applies to the states of Alaska, southern Florida, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.6 The CDC recommended that infants born < 34 weeks’ gestation should receive nirsevimab.6

Maternal RSV vaccination is thought to be cost-effective for reducing RSV LRTD in infants. However, the cost-effectiveness analyses are sensitive to the pricing of the two main options: maternal RSV vaccination and nirsevimab.

It is estimated that nirsevimab may provide greater protection than maternal RSV vaccination from RSV LRTD, but the maternal RSVpreF vaccine is priced lower than nirsevimab.18 Focusing administration of RSVpreF vaccine from September through January of the RSV infection season is thought to maximize benefits to infants and reduce total cost of the vaccination program.19 With year-round RSVpreF vaccine dosing, the estimated ICER per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) is approximately $400,000, whereas seasonal dosing reduces the cost to approximately $170,000.19

RSV prevention strategy 3

Vaccinate pregnant persons; reflex to newborn treatment with nirsevimab if maternal RSV vaccination did not occur

RSVpreF vaccination to all pregnant persons 32 through 36 weeks’ gestation during RSV infection season is not likely to result in 100% adherence. For instance, in a CDC-conducted survey only 47% of pregnant persons received an influenza vaccine.2 Newborns whose mothers did not receive an RSVpreF vaccine will need to be considered for treatment with nirsevimab. Collaboration and communication among obstetricians and pediatricians will be needed to avoid miscommunication and missed opportunities to treat newborns during the birth hospitalization. Enhancements in electronic health records, linking the mother’s vaccination record with the newborn’s medical record plus an added feature of electronic alerts when the mother did not receive an appropriately timed RSVpreF vaccine would improve the communication of important clinical information to the pediatrician.

Next steps for the upcoming peak RSV season

We are currently in the 2023–2024 RSV infection season and can expect a peak in cases of RSV between December 2023 and February 2024. The CDC recommends protecting all infants against RSV-associated LRTD. The options are to administer the maternal RSVpreF vaccine to pregnant persons or treating the infant with nirsevimab. The vaccine is just now becoming available for administration in regional pharmacies, physician practices, and health systems. Obstetrician-gynecologists should follow the recommendation of their state department of public health. As noted above, many state departments of public health are recommending that all newborns receive nirsevimab. For clinicians in those states, RSVPreF vaccination of pregnant persons is not a priority. ●

- Tramuto F, Massimo Maida C, Mazzucco W, et al. Molecular epidemiology and genetic diversity of human respiratory syncytial virus in Sicily during pre- and post-COVID-19 surveillance season. Pathogens. 2023;12:1099.

- Boudreau M, Vadlamudi NK, Bastien N, et al. Pediatric RSV-associated hospitalizations before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2336863.

- Leader S, Kohlhase K. Recent trends in severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) among US infants, 1997 to 2000. J Pediatr. 2003;143(5 Suppl):S127-132.

- Hamid S, Winn A, Parikh R, et al. Seasonality of respiratory syncytial virus-United States 2017-2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:355-361.