User login

PPIs, H2RAs in infants raise later allergy risk

Children prescribed histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), or antibiotics during the first 6 months of life may be at greater risk of developing allergic disease, research suggests.

A retrospective cohort study looked at the incidence of subsequent allergic disease in 792,130 children, 7.6% of whom were prescribed an H2RA, 1.7% were prescribed a PPI, and 16.6% were prescribed an antibiotic during the first 6 months of life.

Children who were prescribed a H2RA or a PPI had a greater than twofold higher incidence of food allergy (adjusted hazard ratios 2.18 and 2.59, respectively), reported Edward Mitre, MD, of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and his coauthors, reported in the April 2 online edition of JAMA Pediatrics.

In particular, the use of acid-suppressing medications was associated with a 2.4-fold increase in the risk of being diagnosed with cow’s milk allergy, while the risk of egg allergy was 74% higher in children prescribed an H2RA and 35% higher in children prescribed a PPI. In children prescribed an H2RA, the risk of peanut allergy was 21% higher, and in children prescribed a PPI, it was 27% higher.

There also was a dose-dependent interaction between the duration of medication and risk of food allergy. Children who were prescribed more than 60 days of PPIs had a 52% higher risk than did those who were prescribed 1-60 days, and a similar but slightly lower increased risk was seen in those prescribed more than 60 days of H2RAs (hazard ratio, 1.32).

Acid-suppressing medication use also was associated with an increased risk of nonfood allergies, in particular medication allergy (adjusted HR, 1.70 for H2RAs and 1.84 for PPIs), allergic rhinitis (aHR, 1.50 for H2RAs and 1.44 for PPIs), anaphylaxis (aHR, 1.51 for H2RAs and 1.45 for PPIs).

Infants prescribed acid-suppressing medication also showed higher rates of asthma, allergic conjunctivitis, and urticaria during childhood.

The use of antibiotics in the first 6 months of life was associated with a 14% higher incidence of food allergy but with a 24% higher risk of cow’s milk allergy and egg allergy. Children prescribed antibiotics also had a twofold greater risk of asthma, a 51% higher risk of anaphylaxis, 42% higher risk of allergic conjunctivitis, and a 34% higher risk of medication allergy.

“This study adds to the mounting evidence that agents that disrupt the normal intestinal microbiome during infancy may increase the development of allergic disease,” said Dr. Mitre and his coauthors. “Thus, this study provides further impetus that antibiotics and acid-suppressive medications should be used during infancy only in situations of clear clinical benefit.”

No funding source or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Mitre E et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315.

Children prescribed histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), or antibiotics during the first 6 months of life may be at greater risk of developing allergic disease, research suggests.

A retrospective cohort study looked at the incidence of subsequent allergic disease in 792,130 children, 7.6% of whom were prescribed an H2RA, 1.7% were prescribed a PPI, and 16.6% were prescribed an antibiotic during the first 6 months of life.

Children who were prescribed a H2RA or a PPI had a greater than twofold higher incidence of food allergy (adjusted hazard ratios 2.18 and 2.59, respectively), reported Edward Mitre, MD, of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and his coauthors, reported in the April 2 online edition of JAMA Pediatrics.

In particular, the use of acid-suppressing medications was associated with a 2.4-fold increase in the risk of being diagnosed with cow’s milk allergy, while the risk of egg allergy was 74% higher in children prescribed an H2RA and 35% higher in children prescribed a PPI. In children prescribed an H2RA, the risk of peanut allergy was 21% higher, and in children prescribed a PPI, it was 27% higher.

There also was a dose-dependent interaction between the duration of medication and risk of food allergy. Children who were prescribed more than 60 days of PPIs had a 52% higher risk than did those who were prescribed 1-60 days, and a similar but slightly lower increased risk was seen in those prescribed more than 60 days of H2RAs (hazard ratio, 1.32).

Acid-suppressing medication use also was associated with an increased risk of nonfood allergies, in particular medication allergy (adjusted HR, 1.70 for H2RAs and 1.84 for PPIs), allergic rhinitis (aHR, 1.50 for H2RAs and 1.44 for PPIs), anaphylaxis (aHR, 1.51 for H2RAs and 1.45 for PPIs).

Infants prescribed acid-suppressing medication also showed higher rates of asthma, allergic conjunctivitis, and urticaria during childhood.

The use of antibiotics in the first 6 months of life was associated with a 14% higher incidence of food allergy but with a 24% higher risk of cow’s milk allergy and egg allergy. Children prescribed antibiotics also had a twofold greater risk of asthma, a 51% higher risk of anaphylaxis, 42% higher risk of allergic conjunctivitis, and a 34% higher risk of medication allergy.

“This study adds to the mounting evidence that agents that disrupt the normal intestinal microbiome during infancy may increase the development of allergic disease,” said Dr. Mitre and his coauthors. “Thus, this study provides further impetus that antibiotics and acid-suppressive medications should be used during infancy only in situations of clear clinical benefit.”

No funding source or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Mitre E et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315.

Children prescribed histamine2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), or antibiotics during the first 6 months of life may be at greater risk of developing allergic disease, research suggests.

A retrospective cohort study looked at the incidence of subsequent allergic disease in 792,130 children, 7.6% of whom were prescribed an H2RA, 1.7% were prescribed a PPI, and 16.6% were prescribed an antibiotic during the first 6 months of life.

Children who were prescribed a H2RA or a PPI had a greater than twofold higher incidence of food allergy (adjusted hazard ratios 2.18 and 2.59, respectively), reported Edward Mitre, MD, of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and his coauthors, reported in the April 2 online edition of JAMA Pediatrics.

In particular, the use of acid-suppressing medications was associated with a 2.4-fold increase in the risk of being diagnosed with cow’s milk allergy, while the risk of egg allergy was 74% higher in children prescribed an H2RA and 35% higher in children prescribed a PPI. In children prescribed an H2RA, the risk of peanut allergy was 21% higher, and in children prescribed a PPI, it was 27% higher.

There also was a dose-dependent interaction between the duration of medication and risk of food allergy. Children who were prescribed more than 60 days of PPIs had a 52% higher risk than did those who were prescribed 1-60 days, and a similar but slightly lower increased risk was seen in those prescribed more than 60 days of H2RAs (hazard ratio, 1.32).

Acid-suppressing medication use also was associated with an increased risk of nonfood allergies, in particular medication allergy (adjusted HR, 1.70 for H2RAs and 1.84 for PPIs), allergic rhinitis (aHR, 1.50 for H2RAs and 1.44 for PPIs), anaphylaxis (aHR, 1.51 for H2RAs and 1.45 for PPIs).

Infants prescribed acid-suppressing medication also showed higher rates of asthma, allergic conjunctivitis, and urticaria during childhood.

The use of antibiotics in the first 6 months of life was associated with a 14% higher incidence of food allergy but with a 24% higher risk of cow’s milk allergy and egg allergy. Children prescribed antibiotics also had a twofold greater risk of asthma, a 51% higher risk of anaphylaxis, 42% higher risk of allergic conjunctivitis, and a 34% higher risk of medication allergy.

“This study adds to the mounting evidence that agents that disrupt the normal intestinal microbiome during infancy may increase the development of allergic disease,” said Dr. Mitre and his coauthors. “Thus, this study provides further impetus that antibiotics and acid-suppressive medications should be used during infancy only in situations of clear clinical benefit.”

No funding source or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Mitre E et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Children prescribed acid-suppressing medications before 6 months had a greater than twofold higher incidence of food allergy.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study in 792,130 children between Oct. 1, 2001, and Sept. 30, 2013.

Disclosures: No funding source or conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Mitre E et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315.

Neurology faculty gender gap confirmed, but explanations remain scant

Despite a wide gap between male and female neurologists, both in terms of academic faculty rank and number of publications, there may be some good news for women in this medical field.

A recent study of the 1,712 academic neurologists across 29 top-ranked neurology programs revealed that 1,184 (69%) were men and 528 (31%) were women, and men outnumbered women in all academic faculty ranks with a gap that increased as the rank advanced. For example, at the rank of instructor/lecturer, the male-to-female ratio was 59% to 41%. The gap only widens from there: assistant professor (57% male), associate professor (70%), and professor (86%).

Additionally, unadjusted analyses showed that men had significantly more publications listed in PubMed than women at the positions of assistant professor, associate professor, and full professor.

The investigators compiled their list of programs and faculty members by combining the top 20 programs listed on either the 2016 or 2017 Doximity Residency Navigator tool with the top 20 programs listed in the U.S. News and World Report ranking of Best Graduate Schools and a search of the programs’ departmental websites between December 1, 2015, and April 30, 2016.

The study was not able to account for many potential explanations for the gender gap, suggesting that the findings may not necessarily be indicative of bad news.

The results “can be viewed as either disappointing or encouraging, depending on whether they reflect persistent barriers to women trying to achieve similar goals as men, or whether they reflect a system that supports women with different goals altogether,” Dr. McDermott and her colleagues wrote.

For example, the authors note that there are a variety of explanations for the gender gap in both rank and publication, including asymmetric home or childcare responsibilities, cultural stereotypes, professional isolation, and different career motivations, though the study was not able to account for those variables.

“Compared with men, women may be more likely to be recruited for employment positions that emphasize teaching and mentoring rather than research, or women may be more inclined to choose such positions,” the authors noted, adding that academic institutions are moving beyond traditional measures of academic productivity (publication rate, publication impact, and grant support) to recognize other factors, such as the quality and quantity of teaching, the development of educational resources, and administrative effectiveness.

If the numbers reflect persistent barriers to women, “it will be important to develop programs to heighten awareness of diversity in academic neurology,” the authors stated. On the flip side, if the numbers reflect a system that is supporting different goals, “academic neurology departments should be encouraged to foster a variety of career paths and expectations for all faculty.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Jerry Isler Neuromuscular Fund.

SOURCE: McDermott M et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0275.

While there may be positive ways to interpret the data, challenges remain for women who want to pursue a career path that features more traditional ways of being recognized. These include ensuring that career paths that require protected time for research and depend on publication and grant support are carefully monitored; and determining that barriers do not hinder women from advancing.

Training programs also must be revisited to ensure that parity across the wider spectrum of careers in neurology is maintained and opportunities continue to exist for both men and women as the specialty continues to grow.

Frances Jensen, MD , is with the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Her remarks are derived from an editorial accompanying the report by Dr. McDermott and colleagues (JAMA Neurol. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0300). She reported no disclosures.

While there may be positive ways to interpret the data, challenges remain for women who want to pursue a career path that features more traditional ways of being recognized. These include ensuring that career paths that require protected time for research and depend on publication and grant support are carefully monitored; and determining that barriers do not hinder women from advancing.

Training programs also must be revisited to ensure that parity across the wider spectrum of careers in neurology is maintained and opportunities continue to exist for both men and women as the specialty continues to grow.

Frances Jensen, MD , is with the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Her remarks are derived from an editorial accompanying the report by Dr. McDermott and colleagues (JAMA Neurol. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0300). She reported no disclosures.

While there may be positive ways to interpret the data, challenges remain for women who want to pursue a career path that features more traditional ways of being recognized. These include ensuring that career paths that require protected time for research and depend on publication and grant support are carefully monitored; and determining that barriers do not hinder women from advancing.

Training programs also must be revisited to ensure that parity across the wider spectrum of careers in neurology is maintained and opportunities continue to exist for both men and women as the specialty continues to grow.

Frances Jensen, MD , is with the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Her remarks are derived from an editorial accompanying the report by Dr. McDermott and colleagues (JAMA Neurol. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0300). She reported no disclosures.

Despite a wide gap between male and female neurologists, both in terms of academic faculty rank and number of publications, there may be some good news for women in this medical field.

A recent study of the 1,712 academic neurologists across 29 top-ranked neurology programs revealed that 1,184 (69%) were men and 528 (31%) were women, and men outnumbered women in all academic faculty ranks with a gap that increased as the rank advanced. For example, at the rank of instructor/lecturer, the male-to-female ratio was 59% to 41%. The gap only widens from there: assistant professor (57% male), associate professor (70%), and professor (86%).

Additionally, unadjusted analyses showed that men had significantly more publications listed in PubMed than women at the positions of assistant professor, associate professor, and full professor.

The investigators compiled their list of programs and faculty members by combining the top 20 programs listed on either the 2016 or 2017 Doximity Residency Navigator tool with the top 20 programs listed in the U.S. News and World Report ranking of Best Graduate Schools and a search of the programs’ departmental websites between December 1, 2015, and April 30, 2016.

The study was not able to account for many potential explanations for the gender gap, suggesting that the findings may not necessarily be indicative of bad news.

The results “can be viewed as either disappointing or encouraging, depending on whether they reflect persistent barriers to women trying to achieve similar goals as men, or whether they reflect a system that supports women with different goals altogether,” Dr. McDermott and her colleagues wrote.

For example, the authors note that there are a variety of explanations for the gender gap in both rank and publication, including asymmetric home or childcare responsibilities, cultural stereotypes, professional isolation, and different career motivations, though the study was not able to account for those variables.

“Compared with men, women may be more likely to be recruited for employment positions that emphasize teaching and mentoring rather than research, or women may be more inclined to choose such positions,” the authors noted, adding that academic institutions are moving beyond traditional measures of academic productivity (publication rate, publication impact, and grant support) to recognize other factors, such as the quality and quantity of teaching, the development of educational resources, and administrative effectiveness.

If the numbers reflect persistent barriers to women, “it will be important to develop programs to heighten awareness of diversity in academic neurology,” the authors stated. On the flip side, if the numbers reflect a system that is supporting different goals, “academic neurology departments should be encouraged to foster a variety of career paths and expectations for all faculty.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Jerry Isler Neuromuscular Fund.

SOURCE: McDermott M et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0275.

Despite a wide gap between male and female neurologists, both in terms of academic faculty rank and number of publications, there may be some good news for women in this medical field.

A recent study of the 1,712 academic neurologists across 29 top-ranked neurology programs revealed that 1,184 (69%) were men and 528 (31%) were women, and men outnumbered women in all academic faculty ranks with a gap that increased as the rank advanced. For example, at the rank of instructor/lecturer, the male-to-female ratio was 59% to 41%. The gap only widens from there: assistant professor (57% male), associate professor (70%), and professor (86%).

Additionally, unadjusted analyses showed that men had significantly more publications listed in PubMed than women at the positions of assistant professor, associate professor, and full professor.

The investigators compiled their list of programs and faculty members by combining the top 20 programs listed on either the 2016 or 2017 Doximity Residency Navigator tool with the top 20 programs listed in the U.S. News and World Report ranking of Best Graduate Schools and a search of the programs’ departmental websites between December 1, 2015, and April 30, 2016.

The study was not able to account for many potential explanations for the gender gap, suggesting that the findings may not necessarily be indicative of bad news.

The results “can be viewed as either disappointing or encouraging, depending on whether they reflect persistent barriers to women trying to achieve similar goals as men, or whether they reflect a system that supports women with different goals altogether,” Dr. McDermott and her colleagues wrote.

For example, the authors note that there are a variety of explanations for the gender gap in both rank and publication, including asymmetric home or childcare responsibilities, cultural stereotypes, professional isolation, and different career motivations, though the study was not able to account for those variables.

“Compared with men, women may be more likely to be recruited for employment positions that emphasize teaching and mentoring rather than research, or women may be more inclined to choose such positions,” the authors noted, adding that academic institutions are moving beyond traditional measures of academic productivity (publication rate, publication impact, and grant support) to recognize other factors, such as the quality and quantity of teaching, the development of educational resources, and administrative effectiveness.

If the numbers reflect persistent barriers to women, “it will be important to develop programs to heighten awareness of diversity in academic neurology,” the authors stated. On the flip side, if the numbers reflect a system that is supporting different goals, “academic neurology departments should be encouraged to foster a variety of career paths and expectations for all faculty.”

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Jerry Isler Neuromuscular Fund.

SOURCE: McDermott M et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0275.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Major finding: Male-to-female ratio widens as rank advances, from 59% male at instructor/lecturer to 86% male at full professor.

Study details: An examination of 1,712 academic neurologists across 29 top-ranked academic institutions.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Jerry Isler Neuromuscular Fund.

Source: McDermott M et al. JAMA Neurol. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0275.

Pot legalization tied to drop in opioid prescribing rates

Laws covering medical or recreational use of marijuana are associated with reduced rates of opioid prescribing among federal health care program enrollees, results of two recently published investigations show.

In one study, researchers investigated whether medical cannabis access affected opioid prescribing in Medicare Part D, the federal program that subsidizes cost of prescription drugs and drug insurance premiums.

“Medical cannabis policies may be one mechanism that can encourage lower prescription opioid use and serve as a harm abatement tool in the opioid crisis,” Ms. Bradford and her coauthors wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Medical marijuana laws were associated with a decrease of 2.11 million daily opioid doses yearly from an average of 23.08 million doses yearly in the Medicare Part D population, according to results of the longitudinal analysis daily opioids doses filled in Medicare Part D from 2010 through 2015.

In a second study, medical marijuana laws were associated with lower opioid prescribing rates among Medicaid enrollees.

That finding was consistent with earlier studies looking more broadly at pain prescriptions covered by Medicaid that also showed a reduction, researchers Hefei Wen, PhD, and Jason M. Hockenberry, PhD, wrote in their JAMA Internal Medicine article.

However, adult-use marijuana laws were associated with “even-lower” opioid prescribing rates, something that had not been investigated previously, according to Dr. Wen, who is with the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and Dr. Hockenberry of Emory University, Atlanta.

“Medical and adult-use marijuana laws have the potential to lower opioid prescribing for Medicaid enrollees, a high-risk population for chronic pain, opioid use disorder, and opioid overdose,” Dr. Wen and Dr. Hockenberry wrote in their report on the study, a cross-sectional analysis including all Medicaid fee-for-service and managed care enrollees during 2011-2016.

The rate of opioid prescribing in the study was –5.88% lower (95% confidence interval, –11.55% to approximately –0.21%) in association with medical marijuana laws, and –6.38% lower (95% CI, –12.20% to approximately –0.56%) for adult-use laws, they reported.

Based on those findings, policy discussions about the opioid epidemic should include the potential for liberalization of marijuana policies to reduce prescription opioid use and consequences in Medicaid enrollees, Dr. Wen and Dr. Hockenberry concluded.

However, legal marijuana alone won’t solve the opioid epidemic, they cautioned.

“As with other policies evaluated in the previous literature, marijuana liberalization is but one potential aspect of a comprehensive package to tackle the epidemic,” they said in the article.

None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Bradford AC et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0266; Wen H, Hockenberry JM. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1007.

Results of these two investigations suggest that the legalization of marijuana may help combat the opioid crisis, but more rigorous investigations are needed, according to Kevin P. Hill, MD, and Andrew J. Saxon, MD.

The new studies show an association between state marijuana laws and fewer opioid prescriptions in Medicare and Medicaid populations.

Those findings do support previous investigations of administrative data sets suggesting that cannabis legalization policies are associated with reductions in opioid use and mortality, Dr. Hill and Dr. Saxon said in an editorial.

However, not all studies suggest that cannabis replaces opioid use, according to the authors, who cited a study suggesting an association between illicit cannabis use and subsequent cannabis use.

“The association between illicit cannabis use and opioid use may be different than the association of legalized cannabis use and opioids,” the editorial authors wrote. “Nevertheless, the findings demonstrating that cannabis use is associated with initiation of or increase in opioid use underscores the fact that rigorous scientific studies are needed.”

Those studies should focus not only analysis of policies on legal medical and recreational cannabis but also on clinical trials of cannabis and cannabinoids for chronic pain and other conditions where opioids are used, they added.

One limitation of the studies is that , according to the authors.

Nevertheless, the authors wrote, a decrease tied to legal marijuana availability would “dovetail” with preclinical evidence that cannabinoid and opioid receptor systems mediate signaling pathways involved in tolerance, dependence, and addiction.

“These concepts support anecdotal evidence from patients who describe a decreased need for opioids to treat chronic pain after initiation of medical cannabis pharmacotherapy,” the authors wrote.

Kevin P. Hill, MD, is with the division of addiction psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston. Andrew J. Saxon, MD, is with the Center of Excellence in Substance Abuse Treatment and Education at the VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, and the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at University of Washington, both in Seattle. These comments are derived from their editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0254). The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Results of these two investigations suggest that the legalization of marijuana may help combat the opioid crisis, but more rigorous investigations are needed, according to Kevin P. Hill, MD, and Andrew J. Saxon, MD.

The new studies show an association between state marijuana laws and fewer opioid prescriptions in Medicare and Medicaid populations.

Those findings do support previous investigations of administrative data sets suggesting that cannabis legalization policies are associated with reductions in opioid use and mortality, Dr. Hill and Dr. Saxon said in an editorial.

However, not all studies suggest that cannabis replaces opioid use, according to the authors, who cited a study suggesting an association between illicit cannabis use and subsequent cannabis use.

“The association between illicit cannabis use and opioid use may be different than the association of legalized cannabis use and opioids,” the editorial authors wrote. “Nevertheless, the findings demonstrating that cannabis use is associated with initiation of or increase in opioid use underscores the fact that rigorous scientific studies are needed.”

Those studies should focus not only analysis of policies on legal medical and recreational cannabis but also on clinical trials of cannabis and cannabinoids for chronic pain and other conditions where opioids are used, they added.

One limitation of the studies is that , according to the authors.

Nevertheless, the authors wrote, a decrease tied to legal marijuana availability would “dovetail” with preclinical evidence that cannabinoid and opioid receptor systems mediate signaling pathways involved in tolerance, dependence, and addiction.

“These concepts support anecdotal evidence from patients who describe a decreased need for opioids to treat chronic pain after initiation of medical cannabis pharmacotherapy,” the authors wrote.

Kevin P. Hill, MD, is with the division of addiction psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston. Andrew J. Saxon, MD, is with the Center of Excellence in Substance Abuse Treatment and Education at the VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, and the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at University of Washington, both in Seattle. These comments are derived from their editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0254). The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Results of these two investigations suggest that the legalization of marijuana may help combat the opioid crisis, but more rigorous investigations are needed, according to Kevin P. Hill, MD, and Andrew J. Saxon, MD.

The new studies show an association between state marijuana laws and fewer opioid prescriptions in Medicare and Medicaid populations.

Those findings do support previous investigations of administrative data sets suggesting that cannabis legalization policies are associated with reductions in opioid use and mortality, Dr. Hill and Dr. Saxon said in an editorial.

However, not all studies suggest that cannabis replaces opioid use, according to the authors, who cited a study suggesting an association between illicit cannabis use and subsequent cannabis use.

“The association between illicit cannabis use and opioid use may be different than the association of legalized cannabis use and opioids,” the editorial authors wrote. “Nevertheless, the findings demonstrating that cannabis use is associated with initiation of or increase in opioid use underscores the fact that rigorous scientific studies are needed.”

Those studies should focus not only analysis of policies on legal medical and recreational cannabis but also on clinical trials of cannabis and cannabinoids for chronic pain and other conditions where opioids are used, they added.

One limitation of the studies is that , according to the authors.

Nevertheless, the authors wrote, a decrease tied to legal marijuana availability would “dovetail” with preclinical evidence that cannabinoid and opioid receptor systems mediate signaling pathways involved in tolerance, dependence, and addiction.

“These concepts support anecdotal evidence from patients who describe a decreased need for opioids to treat chronic pain after initiation of medical cannabis pharmacotherapy,” the authors wrote.

Kevin P. Hill, MD, is with the division of addiction psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston. Andrew J. Saxon, MD, is with the Center of Excellence in Substance Abuse Treatment and Education at the VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, and the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at University of Washington, both in Seattle. These comments are derived from their editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0254). The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Laws covering medical or recreational use of marijuana are associated with reduced rates of opioid prescribing among federal health care program enrollees, results of two recently published investigations show.

In one study, researchers investigated whether medical cannabis access affected opioid prescribing in Medicare Part D, the federal program that subsidizes cost of prescription drugs and drug insurance premiums.

“Medical cannabis policies may be one mechanism that can encourage lower prescription opioid use and serve as a harm abatement tool in the opioid crisis,” Ms. Bradford and her coauthors wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Medical marijuana laws were associated with a decrease of 2.11 million daily opioid doses yearly from an average of 23.08 million doses yearly in the Medicare Part D population, according to results of the longitudinal analysis daily opioids doses filled in Medicare Part D from 2010 through 2015.

In a second study, medical marijuana laws were associated with lower opioid prescribing rates among Medicaid enrollees.

That finding was consistent with earlier studies looking more broadly at pain prescriptions covered by Medicaid that also showed a reduction, researchers Hefei Wen, PhD, and Jason M. Hockenberry, PhD, wrote in their JAMA Internal Medicine article.

However, adult-use marijuana laws were associated with “even-lower” opioid prescribing rates, something that had not been investigated previously, according to Dr. Wen, who is with the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and Dr. Hockenberry of Emory University, Atlanta.

“Medical and adult-use marijuana laws have the potential to lower opioid prescribing for Medicaid enrollees, a high-risk population for chronic pain, opioid use disorder, and opioid overdose,” Dr. Wen and Dr. Hockenberry wrote in their report on the study, a cross-sectional analysis including all Medicaid fee-for-service and managed care enrollees during 2011-2016.

The rate of opioid prescribing in the study was –5.88% lower (95% confidence interval, –11.55% to approximately –0.21%) in association with medical marijuana laws, and –6.38% lower (95% CI, –12.20% to approximately –0.56%) for adult-use laws, they reported.

Based on those findings, policy discussions about the opioid epidemic should include the potential for liberalization of marijuana policies to reduce prescription opioid use and consequences in Medicaid enrollees, Dr. Wen and Dr. Hockenberry concluded.

However, legal marijuana alone won’t solve the opioid epidemic, they cautioned.

“As with other policies evaluated in the previous literature, marijuana liberalization is but one potential aspect of a comprehensive package to tackle the epidemic,” they said in the article.

None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Bradford AC et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0266; Wen H, Hockenberry JM. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1007.

Laws covering medical or recreational use of marijuana are associated with reduced rates of opioid prescribing among federal health care program enrollees, results of two recently published investigations show.

In one study, researchers investigated whether medical cannabis access affected opioid prescribing in Medicare Part D, the federal program that subsidizes cost of prescription drugs and drug insurance premiums.

“Medical cannabis policies may be one mechanism that can encourage lower prescription opioid use and serve as a harm abatement tool in the opioid crisis,” Ms. Bradford and her coauthors wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Medical marijuana laws were associated with a decrease of 2.11 million daily opioid doses yearly from an average of 23.08 million doses yearly in the Medicare Part D population, according to results of the longitudinal analysis daily opioids doses filled in Medicare Part D from 2010 through 2015.

In a second study, medical marijuana laws were associated with lower opioid prescribing rates among Medicaid enrollees.

That finding was consistent with earlier studies looking more broadly at pain prescriptions covered by Medicaid that also showed a reduction, researchers Hefei Wen, PhD, and Jason M. Hockenberry, PhD, wrote in their JAMA Internal Medicine article.

However, adult-use marijuana laws were associated with “even-lower” opioid prescribing rates, something that had not been investigated previously, according to Dr. Wen, who is with the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and Dr. Hockenberry of Emory University, Atlanta.

“Medical and adult-use marijuana laws have the potential to lower opioid prescribing for Medicaid enrollees, a high-risk population for chronic pain, opioid use disorder, and opioid overdose,” Dr. Wen and Dr. Hockenberry wrote in their report on the study, a cross-sectional analysis including all Medicaid fee-for-service and managed care enrollees during 2011-2016.

The rate of opioid prescribing in the study was –5.88% lower (95% confidence interval, –11.55% to approximately –0.21%) in association with medical marijuana laws, and –6.38% lower (95% CI, –12.20% to approximately –0.56%) for adult-use laws, they reported.

Based on those findings, policy discussions about the opioid epidemic should include the potential for liberalization of marijuana policies to reduce prescription opioid use and consequences in Medicaid enrollees, Dr. Wen and Dr. Hockenberry concluded.

However, legal marijuana alone won’t solve the opioid epidemic, they cautioned.

“As with other policies evaluated in the previous literature, marijuana liberalization is but one potential aspect of a comprehensive package to tackle the epidemic,” they said in the article.

None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Bradford AC et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0266; Wen H, Hockenberry JM. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1007.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: State laws governing medical and adult use of marijuana may lower prescription opioid use in Medicaid enrollees – a population at high risk for chronic pain and opioid overdose – and in the Medicare Part D population.

Major finding: Medical and adult-use marijuana laws were associated with lower opioid prescribing rates in Medicaid prescription data (–5.88% and –6.38%, respectively). Medical marijuana laws were associated with a decrease of 2.11 million daily doses yearly from an average of 23.08 million doses yearly in the Medicare Part D population.

Study details: A cross-sectional, quasiexperimental study of opioid prescribing trends between 2011 and 2016 for all Medicaid fee-for-service and managed care enrollees, and a longitudinal analysis daily opioids doses filled in Medicare Part D from 2010 through 2015.

Disclosures: None of the study authors reported conflicts of interest.

Sources: Bradford AC et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 2. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0266; Wen H, Hockenberry JM. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 2. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1007.

Alopecia areata has female predominance, more severe types common in boys

reported Iris Wohlmuth-Wieser, MD, of the department of dermatology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and her associates, who conducted a large review of U.S. registry data.

Although it is the third most common dermatosis in children, there are not much data on AA in children, so the researchers used information from the National Alopecia Areata Registry, which was established in 2000. First, interested patients and parents were contacted and asked to fill out a web-based screening questionnaire. In the second phase, they were asked to fill out a more extensive survey and visit one of five U.S. sites for a clinical exam by a dermatologist.

Of the 2,218 children and teens who completed the initial questionnaire, the mean age at the time of the survey was 10 years, and their mean age of onset of AA was 6 years. The female to male ratio was 1.5:1; boys were significantly more likely to have severe types of AA (P = .009). Most patients (70%) were white, followed by mixed ethnicity (11%), Hispanic (3%), and then other ethnicities. About 3% of patients said they had a sibling with AA, 14% said that another first-degree relative had AA, and 8% said that at least three first-degree relatives had AA.

In terms of the degree of hair loss, 45% lost all scalp hair, 31% lost all body hair, and 14% lost all nails.

Concomitant diseases were reported by 47% of the responders, with atopic dermatitis, asthma, hay fever, and allergies the most common.

Of the 643 children and teens who completed a more detailed questionnaire and underwent clinical examination, 63% were female; 26% had at least one relative with AA and 8% had at least three first-degree relatives with AA. Almost 4% had congenital AA.

At the physical exam, there were data on the amount of hair loss in 617 children: Of these children, 37% had lost all scalp hair and 19% had lost up to three-quarters of their scalp hair. In 618 children (in whom information on body hair loss was obtained at the physical exam), 72% lost all or some of their body hair. Information on nails was available in 609 children; in this group, 44% had some nail involvement. More detailed information was available in 290 children; in this group, findings included pitting in 86%, dystrophy in 10%, onycholysis in 2%, ridging in 1%, and onychomycosis in 1%.

Commenting on the 25 children who presented with congenital AA, the authors wrote that this is “an extremely rare and infrequently reported form of AA.

“This is an interesting and important finding, because AA has traditionally been described as an acquired disease,” they added.

In their cohort overall, 25% had a family history of AA, with 8% having more than three first-degree relatives with AA. The researchers said that the percentage of children with AA and a positive family history ranges from 8% to 52% in the literature.

“The predominant presentation of AA types in our cohort (61.4%) was severe hair loss (76%-100% of scalp hair loss). This is comparable with a European study reporting a prevalence of 65%. Other studies on childhood AA conducted in Asian and Arab populations observed mainly mild cases,” they wrote.

Nail involvement, often reported with AA, was evident in 39% of patients who completed the questionnaire online and in 44% on physical exam. This agreed with the 26%-40% involvement reported in the literature.

There were no conflicts of interest or funding information reported.

SOURCE: Wohlmuth-Wieser I et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan 15. doi: 10.1111/pde.13387.

reported Iris Wohlmuth-Wieser, MD, of the department of dermatology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and her associates, who conducted a large review of U.S. registry data.

Although it is the third most common dermatosis in children, there are not much data on AA in children, so the researchers used information from the National Alopecia Areata Registry, which was established in 2000. First, interested patients and parents were contacted and asked to fill out a web-based screening questionnaire. In the second phase, they were asked to fill out a more extensive survey and visit one of five U.S. sites for a clinical exam by a dermatologist.

Of the 2,218 children and teens who completed the initial questionnaire, the mean age at the time of the survey was 10 years, and their mean age of onset of AA was 6 years. The female to male ratio was 1.5:1; boys were significantly more likely to have severe types of AA (P = .009). Most patients (70%) were white, followed by mixed ethnicity (11%), Hispanic (3%), and then other ethnicities. About 3% of patients said they had a sibling with AA, 14% said that another first-degree relative had AA, and 8% said that at least three first-degree relatives had AA.

In terms of the degree of hair loss, 45% lost all scalp hair, 31% lost all body hair, and 14% lost all nails.

Concomitant diseases were reported by 47% of the responders, with atopic dermatitis, asthma, hay fever, and allergies the most common.

Of the 643 children and teens who completed a more detailed questionnaire and underwent clinical examination, 63% were female; 26% had at least one relative with AA and 8% had at least three first-degree relatives with AA. Almost 4% had congenital AA.

At the physical exam, there were data on the amount of hair loss in 617 children: Of these children, 37% had lost all scalp hair and 19% had lost up to three-quarters of their scalp hair. In 618 children (in whom information on body hair loss was obtained at the physical exam), 72% lost all or some of their body hair. Information on nails was available in 609 children; in this group, 44% had some nail involvement. More detailed information was available in 290 children; in this group, findings included pitting in 86%, dystrophy in 10%, onycholysis in 2%, ridging in 1%, and onychomycosis in 1%.

Commenting on the 25 children who presented with congenital AA, the authors wrote that this is “an extremely rare and infrequently reported form of AA.

“This is an interesting and important finding, because AA has traditionally been described as an acquired disease,” they added.

In their cohort overall, 25% had a family history of AA, with 8% having more than three first-degree relatives with AA. The researchers said that the percentage of children with AA and a positive family history ranges from 8% to 52% in the literature.

“The predominant presentation of AA types in our cohort (61.4%) was severe hair loss (76%-100% of scalp hair loss). This is comparable with a European study reporting a prevalence of 65%. Other studies on childhood AA conducted in Asian and Arab populations observed mainly mild cases,” they wrote.

Nail involvement, often reported with AA, was evident in 39% of patients who completed the questionnaire online and in 44% on physical exam. This agreed with the 26%-40% involvement reported in the literature.

There were no conflicts of interest or funding information reported.

SOURCE: Wohlmuth-Wieser I et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan 15. doi: 10.1111/pde.13387.

reported Iris Wohlmuth-Wieser, MD, of the department of dermatology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and her associates, who conducted a large review of U.S. registry data.

Although it is the third most common dermatosis in children, there are not much data on AA in children, so the researchers used information from the National Alopecia Areata Registry, which was established in 2000. First, interested patients and parents were contacted and asked to fill out a web-based screening questionnaire. In the second phase, they were asked to fill out a more extensive survey and visit one of five U.S. sites for a clinical exam by a dermatologist.

Of the 2,218 children and teens who completed the initial questionnaire, the mean age at the time of the survey was 10 years, and their mean age of onset of AA was 6 years. The female to male ratio was 1.5:1; boys were significantly more likely to have severe types of AA (P = .009). Most patients (70%) were white, followed by mixed ethnicity (11%), Hispanic (3%), and then other ethnicities. About 3% of patients said they had a sibling with AA, 14% said that another first-degree relative had AA, and 8% said that at least three first-degree relatives had AA.

In terms of the degree of hair loss, 45% lost all scalp hair, 31% lost all body hair, and 14% lost all nails.

Concomitant diseases were reported by 47% of the responders, with atopic dermatitis, asthma, hay fever, and allergies the most common.

Of the 643 children and teens who completed a more detailed questionnaire and underwent clinical examination, 63% were female; 26% had at least one relative with AA and 8% had at least three first-degree relatives with AA. Almost 4% had congenital AA.

At the physical exam, there were data on the amount of hair loss in 617 children: Of these children, 37% had lost all scalp hair and 19% had lost up to three-quarters of their scalp hair. In 618 children (in whom information on body hair loss was obtained at the physical exam), 72% lost all or some of their body hair. Information on nails was available in 609 children; in this group, 44% had some nail involvement. More detailed information was available in 290 children; in this group, findings included pitting in 86%, dystrophy in 10%, onycholysis in 2%, ridging in 1%, and onychomycosis in 1%.

Commenting on the 25 children who presented with congenital AA, the authors wrote that this is “an extremely rare and infrequently reported form of AA.

“This is an interesting and important finding, because AA has traditionally been described as an acquired disease,” they added.

In their cohort overall, 25% had a family history of AA, with 8% having more than three first-degree relatives with AA. The researchers said that the percentage of children with AA and a positive family history ranges from 8% to 52% in the literature.

“The predominant presentation of AA types in our cohort (61.4%) was severe hair loss (76%-100% of scalp hair loss). This is comparable with a European study reporting a prevalence of 65%. Other studies on childhood AA conducted in Asian and Arab populations observed mainly mild cases,” they wrote.

Nail involvement, often reported with AA, was evident in 39% of patients who completed the questionnaire online and in 44% on physical exam. This agreed with the 26%-40% involvement reported in the literature.

There were no conflicts of interest or funding information reported.

SOURCE: Wohlmuth-Wieser I et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan 15. doi: 10.1111/pde.13387.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The predominant presentation is total hair loss and nail involvement is common.

Major finding: The female to male ratio was 1.5:1; the boys were significantly more likely to have severe types of AA (P = .009).

Study details: National Alopecia Areata Registry registrants under age 18 years were asked to complete a survey.

Disclosures: There were no conflicts of interest or funding information reported.

Source: Wohlmuth-Wieser I et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018. doi: 10.1111/pde.13387.

Pilot study: Topical anticholinergic improved axillary hyperhidrosis in teens, young adults

Nicholas V. Nguyen, MD, of the division of dermatology, Akron Children’s Hospital, Ohio, and his associates reported.

Ten patients aged 13-24 years with moderate to severe axillary hyperhidrosis started the study and were treated with 1 g of oxybutynin 3% gel applied to each axilla every morning for 4 weeks. Of the seven patients who completed the study, four had a two-point reduction in the Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS) at week 1 and all seven achieved that endpoint at week 4. Of the five patients who also had hyperhidrosis of the palms, four had a two-point reduction in the HDSS at weeks 1 and 4; the remaining patient reported no change. Of the five patients who also had plantar hyperhidrosis, two reported a reduction at weeks 1 and 4, two reported no change, and one had no change at week 1 and experienced worse hyperhidrosis at week 4.

Safety data were available in the seven patients who completed the study and in two others, one lost to follow-up after the first week, and one patient who dropped out of the study because of a severe adverse event. Three patients reported application site irritation, but it was mild to moderate and did not require any intervention. Two patients reported xerostomia, which resolved by itself, and one reported constipation and blurry vision unrelated to the study drug.

One patient developed pyelonephritis on the sixth day of treatment, possibly related to the study drug. “This patient had a history of kidney transplantation, immunosuppression, and recurrent urinary tract infections. For these reasons, the drug should be used with caution in patients with a history of urinary retention or recurrent urinary tract infections,” Dr. Nguyen and his colleagues said.

The manufacturer discontinued the 3% formulation during enrollment, because of business reasons. A large, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial to address unanswered questions is warranted, the researchers noted. Oxybutynin 10% gel, approved for treating overactive bladder, is still commercially available.

The study was supported by a Society for Pediatric Dermatology pilot project grant and a Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute grant.

SOURCE: Nguyen NV et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan 15. doi: 10.1111/pde.13404.

Nicholas V. Nguyen, MD, of the division of dermatology, Akron Children’s Hospital, Ohio, and his associates reported.

Ten patients aged 13-24 years with moderate to severe axillary hyperhidrosis started the study and were treated with 1 g of oxybutynin 3% gel applied to each axilla every morning for 4 weeks. Of the seven patients who completed the study, four had a two-point reduction in the Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS) at week 1 and all seven achieved that endpoint at week 4. Of the five patients who also had hyperhidrosis of the palms, four had a two-point reduction in the HDSS at weeks 1 and 4; the remaining patient reported no change. Of the five patients who also had plantar hyperhidrosis, two reported a reduction at weeks 1 and 4, two reported no change, and one had no change at week 1 and experienced worse hyperhidrosis at week 4.

Safety data were available in the seven patients who completed the study and in two others, one lost to follow-up after the first week, and one patient who dropped out of the study because of a severe adverse event. Three patients reported application site irritation, but it was mild to moderate and did not require any intervention. Two patients reported xerostomia, which resolved by itself, and one reported constipation and blurry vision unrelated to the study drug.

One patient developed pyelonephritis on the sixth day of treatment, possibly related to the study drug. “This patient had a history of kidney transplantation, immunosuppression, and recurrent urinary tract infections. For these reasons, the drug should be used with caution in patients with a history of urinary retention or recurrent urinary tract infections,” Dr. Nguyen and his colleagues said.

The manufacturer discontinued the 3% formulation during enrollment, because of business reasons. A large, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial to address unanswered questions is warranted, the researchers noted. Oxybutynin 10% gel, approved for treating overactive bladder, is still commercially available.

The study was supported by a Society for Pediatric Dermatology pilot project grant and a Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute grant.

SOURCE: Nguyen NV et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan 15. doi: 10.1111/pde.13404.

Nicholas V. Nguyen, MD, of the division of dermatology, Akron Children’s Hospital, Ohio, and his associates reported.

Ten patients aged 13-24 years with moderate to severe axillary hyperhidrosis started the study and were treated with 1 g of oxybutynin 3% gel applied to each axilla every morning for 4 weeks. Of the seven patients who completed the study, four had a two-point reduction in the Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS) at week 1 and all seven achieved that endpoint at week 4. Of the five patients who also had hyperhidrosis of the palms, four had a two-point reduction in the HDSS at weeks 1 and 4; the remaining patient reported no change. Of the five patients who also had plantar hyperhidrosis, two reported a reduction at weeks 1 and 4, two reported no change, and one had no change at week 1 and experienced worse hyperhidrosis at week 4.

Safety data were available in the seven patients who completed the study and in two others, one lost to follow-up after the first week, and one patient who dropped out of the study because of a severe adverse event. Three patients reported application site irritation, but it was mild to moderate and did not require any intervention. Two patients reported xerostomia, which resolved by itself, and one reported constipation and blurry vision unrelated to the study drug.

One patient developed pyelonephritis on the sixth day of treatment, possibly related to the study drug. “This patient had a history of kidney transplantation, immunosuppression, and recurrent urinary tract infections. For these reasons, the drug should be used with caution in patients with a history of urinary retention or recurrent urinary tract infections,” Dr. Nguyen and his colleagues said.

The manufacturer discontinued the 3% formulation during enrollment, because of business reasons. A large, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial to address unanswered questions is warranted, the researchers noted. Oxybutynin 10% gel, approved for treating overactive bladder, is still commercially available.

The study was supported by a Society for Pediatric Dermatology pilot project grant and a Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute grant.

SOURCE: Nguyen NV et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan 15. doi: 10.1111/pde.13404.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Gastrointestinal cancers: new standards of care from landmark trials

DR HENRY I am Dr David Henry, the Editor-in-Chief of

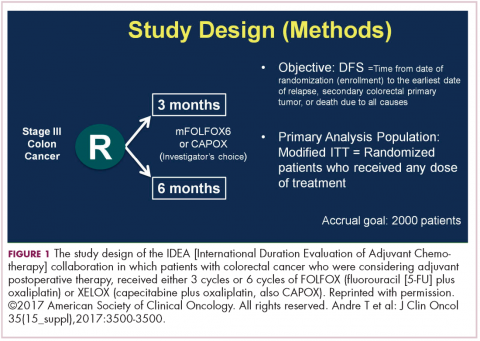

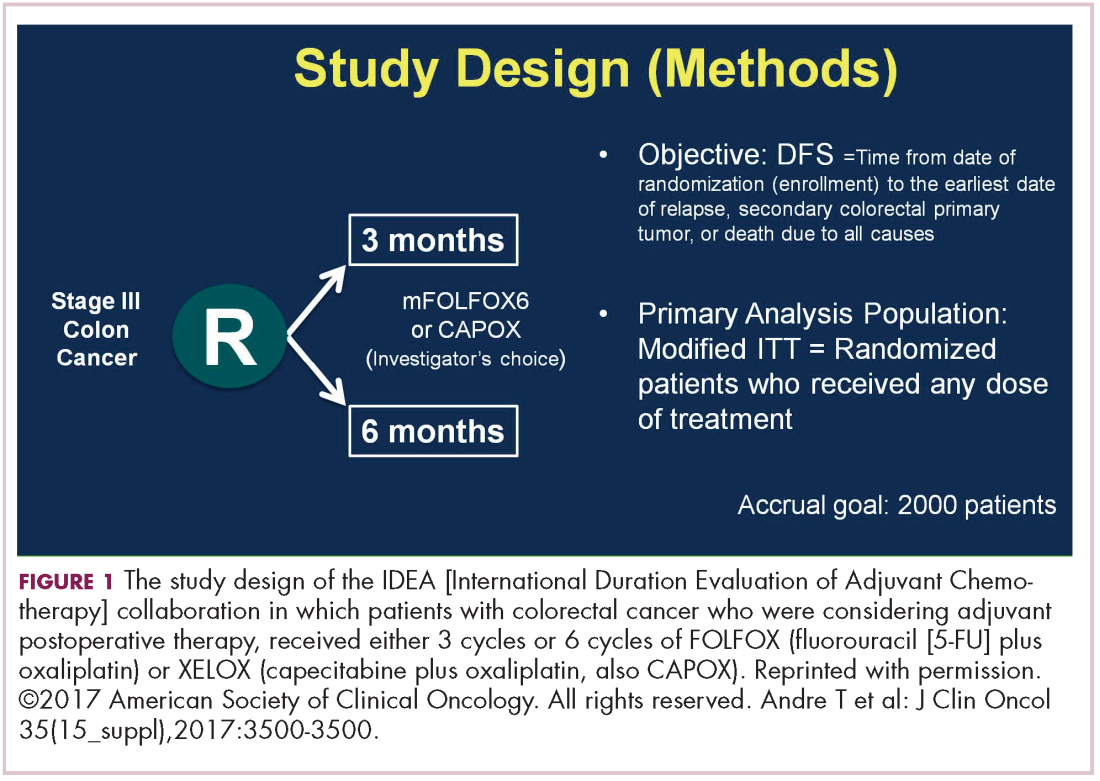

DR HALLER The IDEA collaboration was the brainchild of the late Dan Sargent, a biostatistician who was at the Mayo Clinic. It was his idea, since 6 international groups were all testing the same question of 3 months for oxaliplatin to 6 months of oxaliplatin, to combine the data in an individual patient database – which is the best way to do it – so there were these six trials that were all completed.

Three of them were individually reported at ASCO this year, and then the totality was presented at the plenary session – the first time in 12 years that a gastrointestinal (GI) cancer trial made the plenary session. The whole point, obviously, is neuropathy. With 6 months of FOLFOX or XELOX, about 13% or more patients will develop grade 3 neuropathy, even if people stop short of the full-cycle length, and that is a big deal for the 50,000 patients or so who get adjuvant therapy. At the plenary session, the data were presented and the next day three individual trials were presented and discussed by Jeff Meyerhardt (of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston).

There were 6 different trials: a few included rectum, some included stage II, some used CAPOX and FOLFOX-4 or 6. The only trial that used only FOLFOX was the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) trial in the United States (US). There was a lot of heterogeneity, but when Dan was around, I asked him whether that was a problem, and he said on the contrary, was a better thing because it allowed for real-life practice.

The primary endpoint of the study was to look for noninferiority of 3 months versus 6 months of treatment. The noninferiority margin was at a hazard ratio of 1.12, so they were willing to barter down a few percentage points from benefit. If you looked at the primary disease-free survival analysis, the hazard ratio was 1.07, which was an absolute difference of 0.9%, favoring 3 months of therapy. But because the hazard ratio crossed the 1.12 boundary, it was considered inconclusive and not proven.

If you looked at the regimens, CAPOX outperformed FOLFOX. That’s a regimen we don’t do much in the US. We tend to use more FOLFOX, but CAPOX looked better. What they then did was look at the different subsets of patients, and the subsets that it was obviously as good in was the group that had T1-3N1 disease, where 3 months of therapy was clearly just as good as 6 months of therapy, with only a 3% risk of grade 3 neuropathy.

DR HENRY That would be one to three nodes?

DR HALLER Exactly. That’s about 50% of patients. In the T4N2 patients, neither regimen did very well and the 3-year disease-free survival was in the range of 50%, which is clearly unacceptable. Jeff discussed two things. Why could CAPOX be better? If you do the math, when you do CAPOX, you get more oxaliplatin during the first few months of therapy, because it’s 130 mg every 3 weeks, rather than 85 mg every 2 weeks. His conclusion was, “for my next patient who has T4N2 disease, I’ll offer 6 months of FOLFOX.” The study that really need

He discussed the two new trials. One is a study called ARGO, which is being done by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project, where people get standard adjuvant chemotherapy, and they’re then randomized to either 24 months of regorafenib 120 mg per day or a placebo. This is an attempt to recreate the transient benefit from bevacizumab in the NSABP C-08 trial. It’s accruing slowly because regorafenib has some toxicity associated with it, but it probably will be completed. Will it continue the benefit as seen in the 12 months of bevacizumab and C-08? We’ll see.

The other, more interesting study is being done in the cooperative groups looking at FOLFOX plus atezolizumab, one of the checkpoint inhibitors. The difficulty here is that only 15% of people with stage III disease have microsatellite instability (MSI)-high tumors, but it’s certainly compelling. This is a straight up comparison. It’s 6 months of FOLFOX in the control arm, or 6 months of FOLFOX plus atezolizumab concurrently for 6 months, and then an additional 6 months of atezolizumab. These are both very fascinating ideas.

DR HENRY To go back to one of your original points, this 3 versus 6 months: the neuropathy is significantly less in those getting the 3 months?

DR HALLER It went to 3%.

DR HENRY We all see that is very bothersome to patients. Before we leave colorectal, I must ask about the right-sided versus left-sided colorectal cancer that we hear a lot about now. Could you comment on how right-sided is worse than left-sided, and do we understand why?

DR HALLER There are two things to consider. If you look back even to simple trials of 5-FU or biochemical modulated 5-FU from 20 years ago, there were clear differences showing worse prognosis in patients with right-sided tumors, so that’s one point to be made. It’s been consistently seen but never acted upon. Then, the explanation for it, possibly, is that the right colon and left colon are two biologically different organs – and they are. Embryologically, the right colon comes from the midgut and the left colon comes from the hindgut, and there were several presentations at ASCO and at prior meetings showing that when you look at different mutations, they differ between the right and left colons. The right-sided tumors are more MSI-high and more BRAF-mutated, left-sided mutations less so.

Then, people started analyzing many of the very large colon cancer trials, including the US trial CALB/SWOG C80405 and the FIRE-3 trials in Europe, where backbone chemotherapy of FOLFIRI or FOLFOX was given with either cetuximab or bevacizumab in RAS wild-type patients. For one study, C80405, they saw that for cetuximab, on the right side, the median survival was 16.7 months and on the left side, it’s 36 months – a 20-month difference. In fact, if you look at the totality of the data, 16.7 almost looks like cetuximab is harming them, as if you were giving it to a RAS-mutated patient, but they were not. They were all RAS wild-type.

For bevacizumab, the right side was 24 months; the left side was 31.4 months. If you look at the left, cetuximab was 36 months and bevacizumab was 31.4 months, so it appears left-sided tumors should get more cetuximab than they are now getting in the US with a 5-month difference, but that decrement is much different on the right, where there’s an 8-month benefit for bevacizumab compared with cetuximab. There is a very good review by Dirk Arnold, who looked at a totality of 6 studies to really examine this more carefully.2

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has chimed in on this, and is suggesting that for the 25% of people who have right-sided tumors, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) agents not be considered in first-line therapy. NCCN did not go as far to say that EGFR agents should be given on the left side. As I said, the differences are much more impressive in the right, so this is a real sea change for people to consider which side of the tumor affects outcome.

Deb Schrag (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) presented data at last year’s ASCO not only for stage IV disease showing the same thing, but also stage III disease where there are also right-versus-left differences in terms of recurrence, with a hazard ratio on the right side of about 1.4 compared with the left-sided tumors. Maybe it should be true that 3 months is especially good if you’re treating left-sided tumors, and maybe the right-sided tumor needs to be also calculated with the factors we just talked about. These are two big changes in an area in which we literally haven’t made any change since FOLFOX was introduced a decade ago.

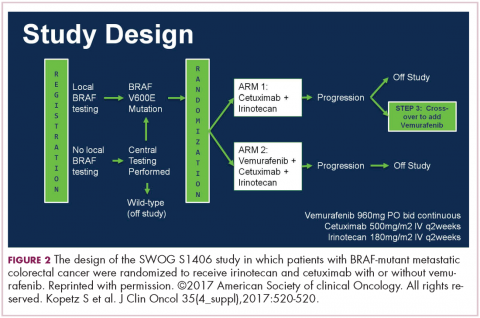

DR HENRY That’s really fascinating, and if not practice changing, then practice challenging. Staying with the mutations idea, in my patients, I’m checking the RAS family and the BRAF mutation, where I’ve learned that’s a particularly bad mutation. I wonder if you might comment on the Kopetz trial, which took a cohort of BRAF mutants and treated them (Figure 2).3 How did that turn out?

DR HALLER It turned out well. We’re turning colon cancer into non–small cell lung cancer in that we’re getting small groups of patients who now have very dedicated care. The backstory here is that there was some thought that you should be treating mutations, not tumor sites. Drugs such as vemurafenib, for example, which is a BRAF inhibitor, worked well in melanoma for the same mutation that’s in colon cancer, V600E. But when vemurafenib was used in the BRAF-mutant patients – these are 10% of the population – median survivorship was one-third that of the rest of the patients, so roughly 12 months. People looked like they were doing worse when vemurafenib was used. They had no benefit.

Scott Kopetz at MD Anderson (Houston, Texas) is a very good bench-to-bed-and-back sort of doc. He looked at this in cell lines and found that when you give a BRAF inhibitor, you upregulate EGFR so you add an EGFR inhibitor. He did a phase 1 and 1B study, and then in the co-operative groups, a study was done – a randomized phase 2 trial for people who had the BRAF-V600E mutation failing first-line therapy, and then went on to receive either irinotecan single agent or irinotecan plus cetuximab or a triple arm of irinotecan, cetuximab, and vemurafenib. There was a crossover, and so the primary endpoint was progression-free survival. It accrued rapidly.

Again, small study, about 100 patients, but for the double-agent arm, or cetuximab–irinotecan, the median survivorship was 2 months. It was 4.4 months for the combination, so more than double. The response rate quadrupled from 4% to 16%, and the people who had disease control tripled, from 22% to 67%. Many of these patients had bulky disease, BRAF mutations. They need response, so this is a very important endpoint.

Overall survival was not different, in part because it was a crossover, and the crossover patients did pretty well. This is going to move more toward first-line therapy, because we don’t talk about fourth- and fifth-line therapies, TAS-102 or regorafenib. These patients don’t make it to even third line. We’re chipping away at what we think is a very homogenous group of peoples’ metastatic disease. They’re obviously not.

DR HENRY In the BRAF-mutant patient, the vemurafenib might drive them toward EGFR, and then the cetuximab could come in and handle that diversion of the pathway. Fascinating.

DR HALLER The preferred regimen in first-line therapy for a BRAF mutant might be FOLFIRI, cetuximab, and vemurafenib, especially on the left side.

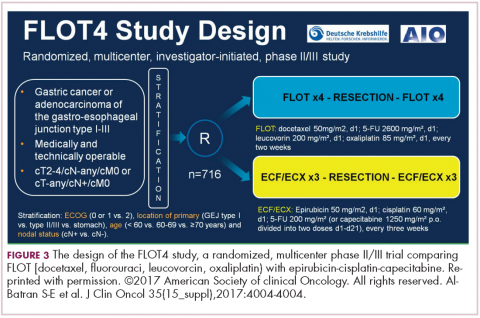

DR HENRY Certainly makes sense. We’ll continue the theme at ASCO of “new standard of care.” Let’s move to gastroesophageal junction. There was a so-called FLOT (5-FU, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, Taxotere) presentation in the neoadjuvant/adjuvant setting, 4 cycles preoperatively and 4 cycles postoperatively. Could you comment on that study?

DR HALLER Gastric cancer for metastatic disease has a very large buffet of treatment regimens, and some just become entrenched, like the ECF regimen with epirubicin (epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU), where most people don’t exactly know what the contribution of that drug is, and so some people use EOX (epirubicin, oxaliplatin, capecitabine), some people use FOLFOX, some people use FOLFIRI. It gets a little bit confusing as to whether you use taxanes, platinums, or 5-FU or capecitabine.

The Germans came up with a regimen called FLOT – it’s sort of like FOLFOX with Taxotere attached. They did a very large study comparing it with ECF or ECX (epirubicin, cisplatin, capecitabine; Figure 3).4 The overall endpoint with over 700 patients was survival. This is an adjuvant regimen. Only 37% of people got ECF or ECX postoperatively, and 50% of the FLOT patients got the regimens postoperatively.

One of the reasons FLOT might be more beneficial is that more people were given postoperative treatment, and it’s one reason why many adjuvant regimens are being moved completely preoperatively, because so few people get the planned treatment. The FLOT regimen improved overall survival with a P value of .0112 and a hazard ratio of 0.77. The difference was 35 months versus 50 months. With the uncertainty as to what epirubicin actually does and the fact that it’s been around for a while and that fewer people receive postoperative treatment, with that 15-month benefit, if you’re using chemotherapy alone, and there’s no radiotherapy component for true gastric cancer, this is a new standard of care.

DR HENRY I struggle with this in my patients as well. This concept of getting more therapy preoperatively to those who can’t get it postoperatively certainly resonates with most of us in practice.

DR HALLER If I were redesigning the trial, I would probably say just give 4-6 cycles of treatment, and give it all preoperatively. In rectal cancer, there’s the total neoadjuvant approach, where it’s being tested in people who get all their chemotherapy first, then chemoradiotherapy, then surgery, and you’re done.

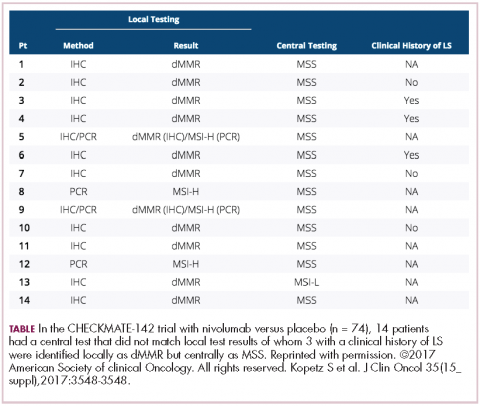

DR HENRY Yes, right. Thank you for mentioning that. Staying with the gastric GE junction, you couldn’t get away from ASCO this year without hearing about the checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapies in this population. In the CHECKMATE-142 trial with nivolumab versus placebo, response rates were good, especially in the MSI-high (microsatellite instability). Could you comment on that study?

DR HALLER We already know that in May and July 2017, pembrolizumab and nivolumab were both approved for any MSI-high solid tumor based on phase 2 data only, and based on response. That’s the first time we’ve seen that happen. It’s remarkable. For nivolumab, the approval was based on 53 patients with MSI-high metastatic colon cancer. So these were people who failed standard therapy and got nivolumab by standard infusion every 2 weeks. The overall response rate was almost 30% in this population, which is typically quite resistant to any treatment, so one expects much lower response rates with anything in that setting – chemotherapy, TAS-102, regorafenib, et cetera (Table).5

More importantly, as we’re seeing with Jimmy Carter with checkpoint treatment (for melanoma that had metastasized to the brain), responses lasted for more than 6 months in about two-thirds of patients, even a complete response, so this is just off the wall. I mean, this is not what you would expect with almost any other treatment. The data are the same for atezolizumab and for pembrolizumab. What seems to be true is that in the GI tumors and colon cancer, MSI-high seems more important than expression of PD-1 or PD-L1 (programmed cell death protein-1 or programmed cell death protein-ligand 1).

In different tumor sites, PD-1 or PD-L1 measurement may be important, but in these tumors, and in colorectal cancer, it looks as if MSI-high is the preferred measurement. Recently ASCO, together with the American Society for Clinical Pathology, College of American Pathologists, and Association for Molecular Pathology, came out with guidelines on what you should measure in colorectal cancer specimens. Obviously, one is extended RAS. They say you should get BRAF for prognosis, but it may also be a prognostic factor that leads you to treat, which ultimately makes it a predictive factor, so the data from Kopetz might suggest that will move up to something you also must measure. If patients have the BRAF mutation, it’s important they know that it’s a poor prognostic sign. But if they come in with literature saying they might live 36 months when their actual outcome is about a third of that, you need to frame your discussion in that regard and make sure they understand it.

The guidelines also suggested getting MSI-high, and certainly prognostically in early-stage disease, but now it’s going to be a predictive factor, so in the month in which these recommendations are made, two of them are already out of date. They also didn’t include human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and what we’ve heard from the HERACLES (HER2 Amplification for Colorectal Cancer Enhanced Stratification) trial is that for those patients who got the trastuzumab and pertuzumab combination – and this is another 5% of patients – almost the same data was seen as in the MSI-high patients with checkpoint inhibitors. That is double-digit response rates and durable responses. As I said, we’re very much nearing in colorectal cancer what’s now being done in non-small cell lung cancer.

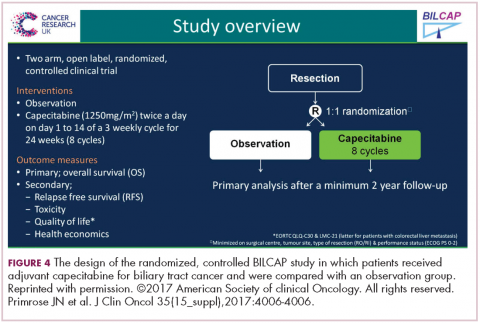

DR HENRY Indeed. Could you comment on the BILCAP study and adjuvant capecitabine for biliary tract cancer?

DR HALLER There are large meta-analyses looking at adjuvant therapy for biliary tract cancers typically from fairly small, fairly old studies that all suggest that in certain stages of resected biliary tumors, either bile duct or gall bladder, adjuvant treatment works, and typically either chemotherapy and radiotherapy, or chemotherapy alone, but not radiotherapy alone.

Capecitabine has been used for metastatic disease for years, mostly by default, and because most GI tumors have some response to fluoropyridines. But we’re finally able now to do large trials in biliary tumors, so this trial was a very large study with almost 450 patients from the United Kingdom over an 8-year period. About 20% were gallbladder, so the R0 surgery was about 60%, R1 at about 40% (Figure 4).6

The endpoint of the study was survival advantage, and when they did the protocol analysis, the survival for the treated population was 53 months and for the observation arm, 36 months, so that was a hazard ratio of 0.75, which is acceptable in an adjuvant study. It’s simple drug to give, and usually tolerable, so this will represent a new standard of care. Of course, in the advanced disease setting, the gemcitabine–cisplatin combination is the standard of care for metastatic disease. It’s a little more toxic combination, but we know that’s standard. There’s an ongoing study in Europe called the ACTICCA-1 trial, and this is gemcitabine–cisplatin for 6 months versus not capecitabine, but a control arm. My guess is if the capecitabine study was positive, that this also will be a positive trial, because gemcitabine–cisplatin is probably more active. Then, we’ll have 2 standards, and I don’t think anyone is going to compare capecitabine with gemcitabine–cisplatin.

What you’ll have are two regimens for two different populations of patients. Perhaps for the elderly and people who have renal problems, capecitabine alone will give them benefit, and then you’ll have gemcitabine–cisplatin, which may be just a more toxic regimen, but also more effective for the younger, healthier people with fewer comorbidities.

DR HENRY Great data and a small population, but a population in need. That moves us on to pancreatic cancer, and I don’t know if this is happening nationwide, but in my practice, I’m seeing more. These patients tend to present beyond surgery, so they have metastatic or advanced pancreatic cancer. Any comment on where you think this field is going?

DR HALLER We were a bit bereft of new pancreatic cancer studies at ASCO this year. We’re certainly looking more at neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer, primarily because of ease of administration and the increased ability to tolerate treatments in the preoperative setting. There aren’t many people that get downstaged, but some are. Unfortunately, even in the MSI-high pancreas, which is a small subset, they don’t seem to get as big a bang out of the checkpoint inhibitors as in other tumor sites, so I’m afraid I didn’t come home with much new about this subset of patients.

DR HENRY We’ve covered a nice group of studies and practice-changing new standard-of-care comments from ASCO and other studies. Thank Dr Dan Haller for being with us and commenting. This podcast and discussion are brought to you from

1. Andre T, Bonnetain F, Mineur L, et al. Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy for patients with stage III colon cancer: disease free survival results of the three versus six months adjuvant IDEA France trial. Abstract presented at: 2017 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 2-6, 2017; Chicago, IL. Abstract 3500.

2. Arnold D, Lueza B, Douillard JY, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of primary tumour side in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy and EGFR directed antibodies in six randomized trials. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1713-1729.

3. Kopetz S, McDonough SL, Lenz H-J, et al. Randomized trial of irinotecan and cetuximab with or without vemurafenib in BRAF-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer (SWOG S1406). Abstract presented at: 2017 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 2-6, 2017; Chicago, IL. Abstract 3505.