User login

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography basics

Ultrasonography has been used to evaluate musculoskeletal problems for decades but has only recently become more widely available in the United States. Advances in technology and physician familiarity are increasing its role in orthopedic imaging.

No single imaging method can yield all musculoskeletal diagnoses. Like any imaging technique, ultrasonography has strengths and weaknesses specific to orthopedics. Radiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) play important roles for investigating musculoskeletal problems and are complementary to each other and to ultrasonography.

To help clinicians make informed decisions about ordering musculoskeletal ultrasonography, this article reviews the basic physics underlying ultrasonography, its advantages and disadvantages compared with other imaging methods, and common clinical applications.

CLASSIC TECHNOLOGY MAKING A RESURGENCE

The first reports of the use of musculoskeletal ultrasonography appeared in the 1970s for investigating the rotator cuff,1–3 actually preceding reports of its use in obstetrics and gynecology.4 In the 1980s, reports emerged for evaluating the Achilles tendon.5,6 After that, its popularity in the United States plateaued, likely because of the advent of MRI, lower reimbursement and greater variability in interpretation compared with MRI, as well as a lack of physicians and sonographers trained in its use.7,8

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is currently experiencing a resurgence. Although it remains a specialized service more commonly available in large hospitals, its use is increasing rapidly, and it will likely become more widely available.

SPECIAL TRAINING REQUIRED

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is simply an ultrasonographic examination of part of the musculoskeletal system. But because not all ultrasonographic transducers offer sufficient resolution for musculoskeletal evaluation and not all sonographers and imaging physicians are familiar with the specialized techniques, musculoskeletal ultrasonography often has a separate designation (eg, “MSKUS,” “MSUS”). At Cleveland Clinic, it is offered through the department of musculoskeletal imaging by subspecialty-trained musculoskeletal radiologists and specially trained musculoskeletal ultrasonographers with 4 to 5 years of training in the technique.

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is also performed by physician groups with specialized training, including sports medicine physicians, rheumatologists, physiatrists, neurologists, and orthopedic surgeons. The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine offers voluntary accreditation for practice groups using musculoskeletal ultrasonography. Certification in musculoskeletal radiology is offered to sonographers through the American Registry for Diagnostic Medical Sonography.

SONOGRAPHY HAS UNIQUE QUALITIES

Ultrasonography uses high-frequency sound waves to generate images. The transducer (or probe) emits sound from the many piezoelectric elements at its surface, and the sound waves travel through and react with tissues. Sound reflected by tissues is detected by the transducer and converted to an image. Objects that reflect sound appear hyperechoic (brighter), whereas tissues that reflect little or no sound appear hypoechoic.

High-resolution imaging of superficial structures

(B, arrow).

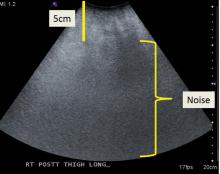

Ultrasonography involves a fundamental trade-off between image resolution and imaging depth. Higher-frequency sound waves do not penetrate far into tissues but generate a higher-resolution image; lower-frequency sound waves can penetrate much further but yield a lower-resolution image. Although high-resolution imaging of deep structures with ultrasonography is not possible (Figure 1), many musculoskeletal structures are located superficially and are amenable to ultrasonographic evaluation.

Be aware of artifacts

Some materials attenuate sound very little, such as simple fluid. Low attenuation results in artifacts on ultrasonography, making tissues behind the simple fluid appear brighter than neighboring tissues. These artifacts may be reported as “increased through transmission” or “posterior acoustic enhancement.” Conversely, metal and bone reflect all sound waves that reach them, rendering any structures beyond them invisible. This “shadowing” creates a problem for imaging of structures in or near bone. Subcutaneous fat also attenuates sound waves, limiting the use of ultrasonography for patients with obesity (Figure 2).

High-frequency linear transducer sharpens images

High-frequency linear transducers reduce anisotropy because their flat surface keeps sound waves more uniformly perpendicular to the structure of interest.4,7 Their development has allowed imaging of superficial structures that is superior to that of MRI. A high-frequency linear transducer offers more than twice the spatial resolution of a typical 1.5T MRI examination of superficial tissue.12,13

Operator experience is critical

Ultrasonography examinations, more than other imaging tests, are dependent on operator experience. A solid understanding of musculoskeletal anatomy is imperative. Because the probe images only a thin section of tissue (about the thickness of a credit card), referencing adjacent structures for orientation is more difficult with ultrasonography than with CT or MRI.

The accuracy of ultrasonography is highly dependent on acquiring and interpreting images, whereas the accuracy of MRI is dependent primarily on image interpretation.7 Interpreting physicians must check that sonographers capture relevant targets.

STRENGTHS OF MUSCULOSKELETAL ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Ultrasonography has multiple advantages:

No ionizing radiation exposure.

Portability. Unlike CT or MRI, ultrasonography equipment is portable.

Increased patient comfort. Patient positioning for an ultrasonography examination is more flexible than for MRI or CT,14 and the examination does not induce claustrophobia.8

High-resolution imaging. Ultrasonography provides very-high-resolution imaging of superficial soft tissues—in some cases, higher than MRI or CT.

Real-time dynamic examinations are possible with ultrasonography, unlike with CT or MRI, and may increase test sensitivity.4,15–18

Implanted hardware is less of a problem. Although ultrasonography cannot image beyond implanted orthopedic metallic hardware, the hardware does not obscure surrounding soft tissues as it does on CT and MRI.6,19,20 Also, ultrasonography is safe for patients with a pacemaker.8

WEAKNESSES

The main disadvantages of musculoskeletal ultrasonography are inherent to its limited field of view, making it inappropriate for a survey examination (eg, for ankle pain, knee pain, hip pain).4 Unlike CT and MRI, ultrasonography does not provide a “bird’s-eye view,” and important abnormalities can be missed during evaluation of large areas (Figure 4).

Ultrasonography also cannot evaluate bone or intra-articular structures such as cartilage, bone marrow, labrum, and intra-articular ligaments; MRI is the standard for evaluating these structures.21

Ultrasonography is time-consuming. To perform a detailed examination of the anterior, posterior, medial, and lateral aspects of the hip, knee, or ankle would require 1.5 to 2 hours of scanning time and an additional 10 to 25 minutes of image checking and interpretation.

CURRENT CLINICAL INDICATIONS

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is best used for clinical questions regarding limited, superficial musculoskeletal problems.

Fluid collections

Ultrasonography can help evaluate small fluid collections in soft tissue. As is true for a lung opacity on chest radiography, soft-tissue fluid detected on ultrasonography is nonspecific, and results must be correlated with the clinical picture to narrow the differential diagnosis.

Fluid collections can be classified as loculated or nonloculated.

Nonloculated fluid involves more fluid than is simply interposed between tissue planes and has no wall or defined margins. It can be simple or complex in appearance: simple fluid is anechoic, and complex fluid appears more heterogeneous and may contain septations or debris.

Subcutaneous edema, which may occur postoperatively or from trauma, venous insufficiency, or inflammatory or infectious processes, appears on ultrasonography as nonloculated fluid interspersed between subcutaneous fat lobules.

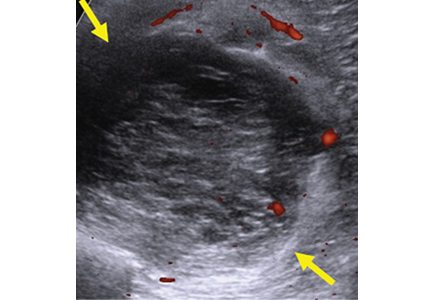

Loculated fluid collections have well-defined margins or a discrete wall that does not follow normal tissue planes. They can also be simple or complex and can be caused by hematoma, abscess, or ganglion. Less commonly, neoplasms can mimic a loculated fluid collection (Figure 4).

A ganglion is a specific type of loculated fluid collection containing synovial fluid arising from a joint or tendon sheath. It tends to occur in specific locations, most commonly around the wrist, most often arising from the dorsal scapholunate ligament and volar wrist between the radial artery and flexor carpi radialis.22 On MRI, it can be difficult to distinguish between small vascular structures and a small ganglion, especially in the hands and feet.23

Ultrasonography can also help identify a Baker cyst, a specific fluid collection arising from the semimembranosus bursa between the medial head of the gastrocnemius tendon and the semimembranosus tendon. Ultrasonography can also detect inflammation, rupture, or leaking associated with a Baker cyst.24

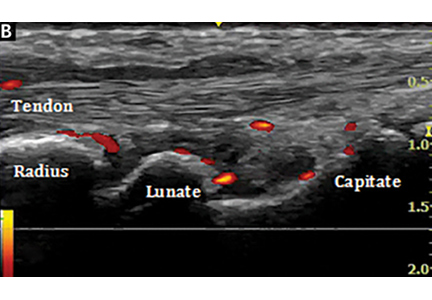

Power Doppler is an ultrasonographic examination that can detect increased blood flow surrounding a fluid collection and determine the likelihood of an acute inflammatory or infectious cause.25

Joint effusion and synovitis

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography can help evaluate joints for effusion and synovitis. It is highly sensitive (94%) and specific (95%) for synovitis, making it superior to contrast-enhanced MRI.26,27 The area of concern should be limited to 1 quadrant of a joint (anterior, posterior, medial, or lateral); for problems beyond that, MRI should be considered.

A joint effusion appears as a distended joint capsule containing hypoechoic (complex) or anechoic (simple) joint fluid.

Complex joint fluid may contain debris and occurs with hemarthrosis, infection, and inflammation.23 Hypertrophied synovium is hypoechoic and can mimic complex joint fluid.

Power Doppler evaluation can help distinguish synovitis from joint fluid by demonstrating blood flow, a feature of synovitis but not of simple joint fluid. Power Doppler is the most sensitive means of detecting blood flow, although it does not show direction of flow.28

Using ultrasonography can help to improve disease control and minimize disabling changes by monitoring synovitis therapy. In addition, subclinical synovitis and enthesitis (inflammation of insertion sites of tendons or ligaments into bone) detected by ultrasonography may predict future disease and disease flares.29–31

Ultrasonographic guidance for a wide range of procedures is increasing rapidly.32–36 Multiple studies have shown the advantage of ultrasonography-guided aspiration and injection compared with techniques without imaging guidance.37,38

Soft-tissue masses

Accurately diagnosing soft-tissue masses can be difficult. A mass may remain indeterminate even after multiple imaging studies, requiring biopsy or surgical referral. However, for a few specific masses, ultrasonography is highly accurate and can eliminate the need for further imaging.

Ultrasonography can help evaluate soft- tissue masses no larger than 5 cm in diameter and no deeper than superficial muscular fascia. If the mass is larger or deeper than that, ultrasonography is less reliable for showing the margins of the mass and its relationship to adjacent structures (Figure 5). Further imaging by MRI may be recommended in such cases.

Fortunately, many of the most common soft-tissue masses can be accurately diagnosed with ultrasonography, including lipomas, ganglion cysts, foreign bodies, and simple fluid collections.4,39 Nerve-sheath tumors can also be diagnosed with ultrasonography if the lesion clearly arises from a nerve. Other soft-tissue masses are likely to be indeterminate with ultrasonography, requiring follow-up with MRI with contrast.

Tendons

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography can be effective for evaluating tendons around joints, especially 1 or a small number of nearby superficial tendons. Tendons particularly well suited for ultrasonographic examination include:

- Upper-extremity tendons located in the rotator cuff or around the elbow, and flexor and extensor tendons of the hands; ultrasonographic evaluation of the rotator cuff is highly accurate, equivalent to that of MRI for partial-thickness and full-thickness tearing40–43

- Lower-extremity tendons of the extensor mechanism of the knee, distal hamstring tendons, tendons around the ankle,44–46 and flexor and extensor tendons of the foot.

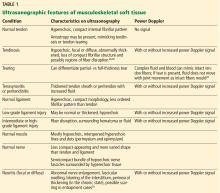

Ultrasonography can help diagnose a variety of tendon abnormalities (Table 1),48,49 including tearing, for which a dynamic examination can be performed.

Many tendons have a tendon sheath containing tenosynovium, while others have surrounding peritenon only; either can become thickened and inflamed. Tenosynovitis is a nonspecific finding and may be inflammatory, infectious, or posttraumatic. The presence of tendon sheath fluid alone on ultrasonography can be a normal finding, and some tendon sheaths that communicate with adjacent joints (eg, the long head biceps tendon, the flexor hallucis longus tendon) commonly contain simple fluid.6 A dynamic examination with ultrasonography can help diagnose snapping related to abnormal tendon movement, for example, in the case of intra-sheath and extra-sheath subluxation of the peroneal tendons.45,50,51

Ligaments

Ultrasonography can detect abnormalities in many superficial ligaments (Table 1).

Ankle. Ankle ligaments are superficial and can be clearly visualized. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for tearing of the anterior talofibular ligament may be as high as 100%.50,52,53

Elbow and thumb. The larger of the collateral ligaments of the elbow, especially the ulnar collateral ligament, and the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb can be effectively evaluated with ultrasonography.54,55

Knee. The collateral ligaments of the knee can be seen with ultrasonography, but injuries of the external ligaments of the knee are often associated with intrinsic derangements that cannot be evaluated with ultrasonography.56,57 Intra-articular ligaments such as the anterior cruciate ligament are also not amenable to ultrasonography.

Dynamic examination of a ligament with ultrasonography can help determine the grade of the injury.

Deeply located ligaments (eg, around the hip) and ligaments surrounded by bone, such as the Lisfranc ligament, cannot be completely seen on ultrasonography.

Muscle

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is useful for small areas of concern within a muscle (Table 1). It can detect muscle strains and tears, intramuscular collections or lesions, and fascial scarring or fascial injuries such as superficial muscle herniation. Although ultrasonography may yield a definitive diagnosis for a muscle problem, further imaging may be needed.

Nerves

Ultrasonography is useful for peripheral nerve investigation but requires a steep learning curve for sonographers and interpreting physicians.58,59 It is best suited for directed questions regarding focal abnormal nerve findings on physical examination.

Ultrasonography can help identify areas of nerve entrapment caused by a mass or dynamic compression. It can detect neuritis (Table 1), lesions of peripheral nerves (eg, nerve-sheath tumors), and neuromas (eg, Morton neuroma of the intermetatarsal space). In a large meta-analysis, ultrasonography and MRI were found to be equally accurate for detecting Morton neuroma.60 Even for nerve-sheath tumors located deep to the muscular fascia, ultrasonography can confirm the diagnosis because of the characteristic appearance of the nerves. Ultrasonography can also demonstrate a large extent of the course of superficial peripheral nerves while keeping the imaging plane appropriately oriented to the nerves.

Acknowledgment: We would like to sincerely thank Megan Griffiths, MA, for her help in the preparation and submission of this manuscript.

- Hamilton JV, Flinn G Jr, Haynie CC, Cefalo RC. Diagnosis of rectus sheath hematoma by B-mode ultrasound: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1976; 125(4):562–565. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(76)90379-3

- Zweymüller VK, Kratochwil A. Ultrasound diagnosis of bone and soft tissue tumours. Wien Klin Wochenschr 1975; 87(12):397–398. German.

- Mayer V. Ultrasonography of the rotator cuff. J Ultrasound Med 1985; 4(11):608, 607. doi:10.7863/jum.1985.4.11.608

- McNally EG. The development and clinical applications of musculoskeletal ultrasound. Skeletal Radiol 2011; 40(9):1223–1231. doi:10.1007/s00256-011-1220-5

- Ignashin NS, Girshin SG, Tsypin IS. Ultrasonic scanning in subcutaneous rupture of the Achilles tendon. Vestn Khir Im I I Grek 1981; 127(9):82–85. Russian.

- Robinson P. Sonography of common tendon injuries. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 193(3):607–618. doi:10.2214/AJR.09.2808

- Jacobson JA. Musculoskeletal ultrasound: focused impact on MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 193(3):619–627. doi:10.2214/AJR.09.2841

- Nazarian LN. The top 10 reasons musculoskeletal sonography is an important complementary or alternative technique to MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 190(6):1621–1626. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.3385

- AIUM technical bulletin. Transducer manipulation. American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. J Ultrasound Med 1999; 18(2):169–175. doi:10.7863/jum.1999.18.2.169

- Connolly DJ, Berman L, McNally EG. The use of beam angulation to overcome anisotropy when viewing human tendon with high frequency linear array ultrasound. Br J Radiol 2001; 74 (878):183–185. doi:10.1259/bjr.74.878.740183

- Crass JR, van de Vegte GL, Harkavy LA. Tendon echogenicity: ex vivo study. Radiology 1988; 167(2):499–501. doi:10.1148/radiology.167.2.3282264

- Erickson SJ. High-resolution imaging of the musculoskeletal system. Radiology 1997; 205(3):593–618. doi:10.1148/radiology.205.3.9393511

- Link TM, Majumdar S, Peterfy C, et al. High resolution MRI of small joints: impact of spatial resolution on diagnostic performance and SNR. Magn Reson Imaging 1998; 16(2):147–155. doi:10.1016/S0730-725X(97)00244-0

- Middleton WD, Payne WT, Teefey SA, Hildebolt CF, Rubin DA, Yamaguchi K. Sonography and MRI of the shoulder: comparison of patient satisfaction. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 183(5):1449–1452. doi:10.2214/ajr.183.5.1831449

- Khoury V, Cardinal E, Bureau NJ. Musculoskeletal sonography: a dynamic tool for usual and unusual disorders. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 188(1):W63–W73. doi:10.2214/AJR.06.0579

- Farin PU, Jaroma H, Harju A, Soimakallio S. Medial displacement of the biceps brachii tendon: evaluation with dynamic sonography during maximal external shoulder rotation. Radiology 1995; 195(3):845–848. doi:10.1148/radiology.195.3.7754019

- Miller TT, Adler RS, Friedman L. Sonography of injury of the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow-initial experience. Skeletal Radiol 2004; 33(7):386–391. doi:10.1007/s00256-004-0788-4

- Nazarian LN, McShane JM, Ciccotti MG, O’Kane PL, Harwood MI. Dynamic US of the anterior band of the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow in asymptomatic major league baseball pitchers. Radiology 2003; 227(1):149–154. doi:10.1148/radiol.2271020288

- Jacobson JA, Lax MJ. Musculoskeletal sonography of the postoperative orthopedic patient. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2002; 6(1):67–77. doi:10.1055/s-2002-23165

- Sofka CM, Adler RS. Original report. Sonographic evaluation of shoulder arthroplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 180(4):1117–1120. doi:10.2214/ajr.180.4.1801117

- Silvestri E, Martinoli C, Derchi LE, Bertolotto M, Chiaramondia M, Rosenberg I. Echotexture of peripheral nerves: correlation between US and histologic findings and criteria to differentiate tendons. Radiology 1995; 197(1):291–296. doi:10.1148/radiology.197.1.7568840

- Cardinal E, Buckwalter KA, Braunstein EM, Mih AD. Occult dorsal carpal ganglion: comparison of US and MR imaging. Radiology 1994; 193(1):259–262. doi:10.1148/radiology.193.1.8090903

- Jacobson JA. Musculoskeletal ultrasound and MRI: which do I choose? Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2005; 9(2):135–149. doi:10.1055/s-2005-872339

- Ward EE, Jacobson JA, Fessell DP, Hayes CW, van Holsbeeck M. Sonographic detection of Baker’s cysts: comparison with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 176(2):373–380. doi:10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760373

- Bhasin S, Cheung PP. The role of power Doppler ultrasonography as disease activity marker in rheumatoid arthritis. Dis Markers 2015; 2015:325909. doi:10.1155/2015/325909

- Fukuba E, Yoshizako T, Kitagaki H, Murakawa Y, Kondo M, Uchida N. Power Doppler ultrasonography for assessment of rheumatoid synovitis: comparison with dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Imaging 2013; 37(1):134–137. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2012.02.008

- Takase-Minegishi K, Horita N, Kobayashi K, et al. Diagnostic test accuracy of ultrasound for synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018; 57(1):49–58. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kex036

- Klareskog L, Catrina AI, Paget S. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2009; 373(9664):659–672. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60008-8

- Ash ZR, Tinazzi I, Gallego CC, et al. Psoriasis patients with nail disease have a greater magnitude of underlying systemic subclinical enthesopathy than those with normal nails. Ann Rheum Dis 2012; 71(4):553–556. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200478

- Han J, Geng Y, Deng X, Zhang Z. Subclinical synovitis assessed by ultrasound predicts flare and progressive bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis patients with clinical remission: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol 2016; 43(11):2010–2018. doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.160193

- Iagnocco A, Finucci A, Ceccarelli F, Perricone C, Iorgoveanu V, Valesini G. Power Doppler ultrasound monitoring of response to anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015; 54(10):1890–1896. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kev211

- Henning PT. Ultrasound-guided foot and ankle procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2016; 27(3):649–671. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.005

- Lueders DR, Smith J, Sellon JL. Ultrasound-guided knee procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 2016; 27(3):631–648. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.010

- Payne JM. Ultrasound-guided hip procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 2016; 27(3):607–629. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.004

- Strakowski JA. Ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 2016; 27(3):687–715. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.006

- Sussman WI, Williams CJ, Mautner K. Ultrasound-guided elbow procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 2016; 27(3):573–587. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.002

- Finnoff JT. The evolution of diagnostic and interventional ultrasound in sports medicine. PM R 2016; 8(suppl 3):S133–S138. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.09.022

- Wu T, Dong Y, Song H, Fu Y, Li JH. Ultrasound-guided versus landmark in knee arthrocentesis: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016; 45(5):627–632. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.10.011

- Failla JM, van Holsbeeck M, Vanderschueren G. Detection of a 0.5-mm-thick thorn using ultrasound: a case report. J Hand Surg Am 1995; 20(3):456–457.

- Teefey SA, Hasan SA, Middleton WD, Patel M, Wright RW, Yamaguchi K. Ultrasonography of the rotator cuff. A comparison of ultrasonographic and arthroscopic findings in one hundred consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82(4):498–504.

- van Holsbeeck MT, Kolowich PA, Eyler WR, et al. US depiction of partial-thickness tear of the rotator cuff. Radiology 1995; 197(2):443–446. doi:10.1148/radiology.197.2.7480690

- Balich SM, Sheley RC, Brown TR, Sauser DD, Quinn SF. MR imaging of the rotator cuff tendon: interobserver agreement and analysis of interpretive errors. Radiology 1997; 204(1):191–194. doi:10.1148/radiology.204.1.9205245

- Dinnes J, Loveman E, McIntyre L, Waugh N. The effectiveness of diagnostic tests for the assessment of shoulder pain due to soft tissue disorders: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2003; 7(29):1–166. doi:10.3310/hta7290

- Rockett MS, Waitches G, Sudakoff G, Brage M. Use of ultrasonography versus magnetic resonance imaging for tendon abnormalities around the ankle. Foot Ankle Int 1998; 19(9):604–612.

- Grant TH, Kelikian AS, Jereb SE, McCarthy RJ. Ultrasound diagnosis of peroneal tendon tears. A surgical correlation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87(8):1788–1794. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.02450

- Hartgerink P, Fessell DP, Jacobson JA, van Holsbeeck MT. Full- versus partial-thickness Achilles tendon tears: sonographic accuracy and characterization in 26 cases with surgical correlation. Radiology 2001; 220(2):406–412. doi:10.1148/radiology.220.2.r01au41406

- Cho KH, Park BH, Yeon KM. Ultrasound of the adult hip. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2000; 21(3):214–230.

- Adler RS, Finzel KC. The complementary roles of MR imaging and ultrasound of tendons. Radiol Clin North Am 2005; 43(4):771–807. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2005.02.011

- Martinoli C, Bianchi S, Derchi LE. Tendon and nerve sonography. Radiol Clin North Am 1999; 37(4):691–711. doi:10.1016/S0033-8389(05)70124-X

- Fessell DP, Vanderschueren GM, Jacobson JA, et al. US of the ankle: technique, anatomy, and diagnosis of pathologic conditions. Radiographics 1998; 18(2):325–340. doi:10.1148/radiographics.18.2.9536481

- Neustadter J, Raikin SM, Nazarian LN. Dynamic sonographic evaluation of peroneal tendon subluxation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 183(4):985–988. doi:10.2214/ajr.183.4.1830985

- Verhaven EF, Shahabpour M, Handelberg FW, Vaes PH, Opdecam PJ. The accuracy of three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of ruptures of the lateral ligaments of the ankle. Am J Sports Med 1991; 19(6):583–587. doi:10.1177/036354659101900605

- Milz P, Milz S, Steinborn M, Mittlmeier T, Putz R, Reiser M. Lateral ankle ligaments and tibiofibular syndesmosis. 13-MHz high-frequency sonography and MRI compared in 20 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 1998; 69(1):51–55.

- De Smet AA, Winter TC, Best TM, Bernhardt DT. Dynamic sonography with valgus stress to assess elbow ulnar collateral ligament injury in baseball pitchers. Skeletal Radiol 2002; 31(11):671–676. doi:10.1007/s00256-002-0558-0

- Melville DM, Jacobson JA, Fessell DP. Ultrasound of the thumb ulnar collateral ligament: technique and pathology. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014; 202(2):W168. doi:10.2214/AJR.13.11335

- Court-Payen M. Sonography of the knee: intra-articular pathology. J Clin Ultrasound 2004; 32(9):481–490. doi:10.1002/jcu.20069

- Azzoni R, Cabitza P. Is there a role for sonography in the diagnosis of tears of the knee menisci? J Clin Ultrasound 2002; 30(8):472–476. doi:10.1002/jcu.10106

- Jacobson JA, Wilson TJ, Yang LJ. Sonography of common peripheral nerve disorders with clinical correlation. J Ultrasound Med 2016; 35(4):683–693. doi:10.7863/ultra.15.05061

- Ali ZS, Pisapia JM, Ma TS, Zager EL, Heuer GG, Khoury V. Ultrasonographic evaluation of peripheral nerves. World Neurosurg 2016; 85(1):333–339. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2015.10.005

- Bignotti B, Signori A, Sormani MP, Molfetta L, Martinoli C, Tagliafico A. Ultrasound versus magnetic resonance imaging for Morton neuroma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 2015; 25(8):2254–2262. doi:10.1007/s00330-015-3633-3

Ultrasonography has been used to evaluate musculoskeletal problems for decades but has only recently become more widely available in the United States. Advances in technology and physician familiarity are increasing its role in orthopedic imaging.

No single imaging method can yield all musculoskeletal diagnoses. Like any imaging technique, ultrasonography has strengths and weaknesses specific to orthopedics. Radiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) play important roles for investigating musculoskeletal problems and are complementary to each other and to ultrasonography.

To help clinicians make informed decisions about ordering musculoskeletal ultrasonography, this article reviews the basic physics underlying ultrasonography, its advantages and disadvantages compared with other imaging methods, and common clinical applications.

CLASSIC TECHNOLOGY MAKING A RESURGENCE

The first reports of the use of musculoskeletal ultrasonography appeared in the 1970s for investigating the rotator cuff,1–3 actually preceding reports of its use in obstetrics and gynecology.4 In the 1980s, reports emerged for evaluating the Achilles tendon.5,6 After that, its popularity in the United States plateaued, likely because of the advent of MRI, lower reimbursement and greater variability in interpretation compared with MRI, as well as a lack of physicians and sonographers trained in its use.7,8

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is currently experiencing a resurgence. Although it remains a specialized service more commonly available in large hospitals, its use is increasing rapidly, and it will likely become more widely available.

SPECIAL TRAINING REQUIRED

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is simply an ultrasonographic examination of part of the musculoskeletal system. But because not all ultrasonographic transducers offer sufficient resolution for musculoskeletal evaluation and not all sonographers and imaging physicians are familiar with the specialized techniques, musculoskeletal ultrasonography often has a separate designation (eg, “MSKUS,” “MSUS”). At Cleveland Clinic, it is offered through the department of musculoskeletal imaging by subspecialty-trained musculoskeletal radiologists and specially trained musculoskeletal ultrasonographers with 4 to 5 years of training in the technique.

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is also performed by physician groups with specialized training, including sports medicine physicians, rheumatologists, physiatrists, neurologists, and orthopedic surgeons. The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine offers voluntary accreditation for practice groups using musculoskeletal ultrasonography. Certification in musculoskeletal radiology is offered to sonographers through the American Registry for Diagnostic Medical Sonography.

SONOGRAPHY HAS UNIQUE QUALITIES

Ultrasonography uses high-frequency sound waves to generate images. The transducer (or probe) emits sound from the many piezoelectric elements at its surface, and the sound waves travel through and react with tissues. Sound reflected by tissues is detected by the transducer and converted to an image. Objects that reflect sound appear hyperechoic (brighter), whereas tissues that reflect little or no sound appear hypoechoic.

High-resolution imaging of superficial structures

(B, arrow).

Ultrasonography involves a fundamental trade-off between image resolution and imaging depth. Higher-frequency sound waves do not penetrate far into tissues but generate a higher-resolution image; lower-frequency sound waves can penetrate much further but yield a lower-resolution image. Although high-resolution imaging of deep structures with ultrasonography is not possible (Figure 1), many musculoskeletal structures are located superficially and are amenable to ultrasonographic evaluation.

Be aware of artifacts

Some materials attenuate sound very little, such as simple fluid. Low attenuation results in artifacts on ultrasonography, making tissues behind the simple fluid appear brighter than neighboring tissues. These artifacts may be reported as “increased through transmission” or “posterior acoustic enhancement.” Conversely, metal and bone reflect all sound waves that reach them, rendering any structures beyond them invisible. This “shadowing” creates a problem for imaging of structures in or near bone. Subcutaneous fat also attenuates sound waves, limiting the use of ultrasonography for patients with obesity (Figure 2).

High-frequency linear transducer sharpens images

High-frequency linear transducers reduce anisotropy because their flat surface keeps sound waves more uniformly perpendicular to the structure of interest.4,7 Their development has allowed imaging of superficial structures that is superior to that of MRI. A high-frequency linear transducer offers more than twice the spatial resolution of a typical 1.5T MRI examination of superficial tissue.12,13

Operator experience is critical

Ultrasonography examinations, more than other imaging tests, are dependent on operator experience. A solid understanding of musculoskeletal anatomy is imperative. Because the probe images only a thin section of tissue (about the thickness of a credit card), referencing adjacent structures for orientation is more difficult with ultrasonography than with CT or MRI.

The accuracy of ultrasonography is highly dependent on acquiring and interpreting images, whereas the accuracy of MRI is dependent primarily on image interpretation.7 Interpreting physicians must check that sonographers capture relevant targets.

STRENGTHS OF MUSCULOSKELETAL ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Ultrasonography has multiple advantages:

No ionizing radiation exposure.

Portability. Unlike CT or MRI, ultrasonography equipment is portable.

Increased patient comfort. Patient positioning for an ultrasonography examination is more flexible than for MRI or CT,14 and the examination does not induce claustrophobia.8

High-resolution imaging. Ultrasonography provides very-high-resolution imaging of superficial soft tissues—in some cases, higher than MRI or CT.

Real-time dynamic examinations are possible with ultrasonography, unlike with CT or MRI, and may increase test sensitivity.4,15–18

Implanted hardware is less of a problem. Although ultrasonography cannot image beyond implanted orthopedic metallic hardware, the hardware does not obscure surrounding soft tissues as it does on CT and MRI.6,19,20 Also, ultrasonography is safe for patients with a pacemaker.8

WEAKNESSES

The main disadvantages of musculoskeletal ultrasonography are inherent to its limited field of view, making it inappropriate for a survey examination (eg, for ankle pain, knee pain, hip pain).4 Unlike CT and MRI, ultrasonography does not provide a “bird’s-eye view,” and important abnormalities can be missed during evaluation of large areas (Figure 4).

Ultrasonography also cannot evaluate bone or intra-articular structures such as cartilage, bone marrow, labrum, and intra-articular ligaments; MRI is the standard for evaluating these structures.21

Ultrasonography is time-consuming. To perform a detailed examination of the anterior, posterior, medial, and lateral aspects of the hip, knee, or ankle would require 1.5 to 2 hours of scanning time and an additional 10 to 25 minutes of image checking and interpretation.

CURRENT CLINICAL INDICATIONS

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is best used for clinical questions regarding limited, superficial musculoskeletal problems.

Fluid collections

Ultrasonography can help evaluate small fluid collections in soft tissue. As is true for a lung opacity on chest radiography, soft-tissue fluid detected on ultrasonography is nonspecific, and results must be correlated with the clinical picture to narrow the differential diagnosis.

Fluid collections can be classified as loculated or nonloculated.

Nonloculated fluid involves more fluid than is simply interposed between tissue planes and has no wall or defined margins. It can be simple or complex in appearance: simple fluid is anechoic, and complex fluid appears more heterogeneous and may contain septations or debris.

Subcutaneous edema, which may occur postoperatively or from trauma, venous insufficiency, or inflammatory or infectious processes, appears on ultrasonography as nonloculated fluid interspersed between subcutaneous fat lobules.

Loculated fluid collections have well-defined margins or a discrete wall that does not follow normal tissue planes. They can also be simple or complex and can be caused by hematoma, abscess, or ganglion. Less commonly, neoplasms can mimic a loculated fluid collection (Figure 4).

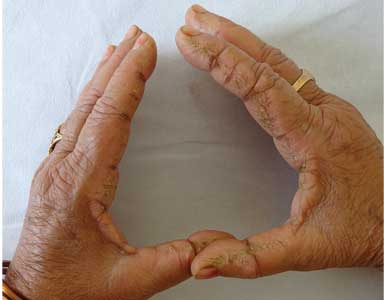

A ganglion is a specific type of loculated fluid collection containing synovial fluid arising from a joint or tendon sheath. It tends to occur in specific locations, most commonly around the wrist, most often arising from the dorsal scapholunate ligament and volar wrist between the radial artery and flexor carpi radialis.22 On MRI, it can be difficult to distinguish between small vascular structures and a small ganglion, especially in the hands and feet.23

Ultrasonography can also help identify a Baker cyst, a specific fluid collection arising from the semimembranosus bursa between the medial head of the gastrocnemius tendon and the semimembranosus tendon. Ultrasonography can also detect inflammation, rupture, or leaking associated with a Baker cyst.24

Power Doppler is an ultrasonographic examination that can detect increased blood flow surrounding a fluid collection and determine the likelihood of an acute inflammatory or infectious cause.25

Joint effusion and synovitis

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography can help evaluate joints for effusion and synovitis. It is highly sensitive (94%) and specific (95%) for synovitis, making it superior to contrast-enhanced MRI.26,27 The area of concern should be limited to 1 quadrant of a joint (anterior, posterior, medial, or lateral); for problems beyond that, MRI should be considered.

A joint effusion appears as a distended joint capsule containing hypoechoic (complex) or anechoic (simple) joint fluid.

Complex joint fluid may contain debris and occurs with hemarthrosis, infection, and inflammation.23 Hypertrophied synovium is hypoechoic and can mimic complex joint fluid.

Power Doppler evaluation can help distinguish synovitis from joint fluid by demonstrating blood flow, a feature of synovitis but not of simple joint fluid. Power Doppler is the most sensitive means of detecting blood flow, although it does not show direction of flow.28

Using ultrasonography can help to improve disease control and minimize disabling changes by monitoring synovitis therapy. In addition, subclinical synovitis and enthesitis (inflammation of insertion sites of tendons or ligaments into bone) detected by ultrasonography may predict future disease and disease flares.29–31

Ultrasonographic guidance for a wide range of procedures is increasing rapidly.32–36 Multiple studies have shown the advantage of ultrasonography-guided aspiration and injection compared with techniques without imaging guidance.37,38

Soft-tissue masses

Accurately diagnosing soft-tissue masses can be difficult. A mass may remain indeterminate even after multiple imaging studies, requiring biopsy or surgical referral. However, for a few specific masses, ultrasonography is highly accurate and can eliminate the need for further imaging.

Ultrasonography can help evaluate soft- tissue masses no larger than 5 cm in diameter and no deeper than superficial muscular fascia. If the mass is larger or deeper than that, ultrasonography is less reliable for showing the margins of the mass and its relationship to adjacent structures (Figure 5). Further imaging by MRI may be recommended in such cases.

Fortunately, many of the most common soft-tissue masses can be accurately diagnosed with ultrasonography, including lipomas, ganglion cysts, foreign bodies, and simple fluid collections.4,39 Nerve-sheath tumors can also be diagnosed with ultrasonography if the lesion clearly arises from a nerve. Other soft-tissue masses are likely to be indeterminate with ultrasonography, requiring follow-up with MRI with contrast.

Tendons

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography can be effective for evaluating tendons around joints, especially 1 or a small number of nearby superficial tendons. Tendons particularly well suited for ultrasonographic examination include:

- Upper-extremity tendons located in the rotator cuff or around the elbow, and flexor and extensor tendons of the hands; ultrasonographic evaluation of the rotator cuff is highly accurate, equivalent to that of MRI for partial-thickness and full-thickness tearing40–43

- Lower-extremity tendons of the extensor mechanism of the knee, distal hamstring tendons, tendons around the ankle,44–46 and flexor and extensor tendons of the foot.

Ultrasonography can help diagnose a variety of tendon abnormalities (Table 1),48,49 including tearing, for which a dynamic examination can be performed.

Many tendons have a tendon sheath containing tenosynovium, while others have surrounding peritenon only; either can become thickened and inflamed. Tenosynovitis is a nonspecific finding and may be inflammatory, infectious, or posttraumatic. The presence of tendon sheath fluid alone on ultrasonography can be a normal finding, and some tendon sheaths that communicate with adjacent joints (eg, the long head biceps tendon, the flexor hallucis longus tendon) commonly contain simple fluid.6 A dynamic examination with ultrasonography can help diagnose snapping related to abnormal tendon movement, for example, in the case of intra-sheath and extra-sheath subluxation of the peroneal tendons.45,50,51

Ligaments

Ultrasonography can detect abnormalities in many superficial ligaments (Table 1).

Ankle. Ankle ligaments are superficial and can be clearly visualized. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for tearing of the anterior talofibular ligament may be as high as 100%.50,52,53

Elbow and thumb. The larger of the collateral ligaments of the elbow, especially the ulnar collateral ligament, and the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb can be effectively evaluated with ultrasonography.54,55

Knee. The collateral ligaments of the knee can be seen with ultrasonography, but injuries of the external ligaments of the knee are often associated with intrinsic derangements that cannot be evaluated with ultrasonography.56,57 Intra-articular ligaments such as the anterior cruciate ligament are also not amenable to ultrasonography.

Dynamic examination of a ligament with ultrasonography can help determine the grade of the injury.

Deeply located ligaments (eg, around the hip) and ligaments surrounded by bone, such as the Lisfranc ligament, cannot be completely seen on ultrasonography.

Muscle

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is useful for small areas of concern within a muscle (Table 1). It can detect muscle strains and tears, intramuscular collections or lesions, and fascial scarring or fascial injuries such as superficial muscle herniation. Although ultrasonography may yield a definitive diagnosis for a muscle problem, further imaging may be needed.

Nerves

Ultrasonography is useful for peripheral nerve investigation but requires a steep learning curve for sonographers and interpreting physicians.58,59 It is best suited for directed questions regarding focal abnormal nerve findings on physical examination.

Ultrasonography can help identify areas of nerve entrapment caused by a mass or dynamic compression. It can detect neuritis (Table 1), lesions of peripheral nerves (eg, nerve-sheath tumors), and neuromas (eg, Morton neuroma of the intermetatarsal space). In a large meta-analysis, ultrasonography and MRI were found to be equally accurate for detecting Morton neuroma.60 Even for nerve-sheath tumors located deep to the muscular fascia, ultrasonography can confirm the diagnosis because of the characteristic appearance of the nerves. Ultrasonography can also demonstrate a large extent of the course of superficial peripheral nerves while keeping the imaging plane appropriately oriented to the nerves.

Acknowledgment: We would like to sincerely thank Megan Griffiths, MA, for her help in the preparation and submission of this manuscript.

Ultrasonography has been used to evaluate musculoskeletal problems for decades but has only recently become more widely available in the United States. Advances in technology and physician familiarity are increasing its role in orthopedic imaging.

No single imaging method can yield all musculoskeletal diagnoses. Like any imaging technique, ultrasonography has strengths and weaknesses specific to orthopedics. Radiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) play important roles for investigating musculoskeletal problems and are complementary to each other and to ultrasonography.

To help clinicians make informed decisions about ordering musculoskeletal ultrasonography, this article reviews the basic physics underlying ultrasonography, its advantages and disadvantages compared with other imaging methods, and common clinical applications.

CLASSIC TECHNOLOGY MAKING A RESURGENCE

The first reports of the use of musculoskeletal ultrasonography appeared in the 1970s for investigating the rotator cuff,1–3 actually preceding reports of its use in obstetrics and gynecology.4 In the 1980s, reports emerged for evaluating the Achilles tendon.5,6 After that, its popularity in the United States plateaued, likely because of the advent of MRI, lower reimbursement and greater variability in interpretation compared with MRI, as well as a lack of physicians and sonographers trained in its use.7,8

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is currently experiencing a resurgence. Although it remains a specialized service more commonly available in large hospitals, its use is increasing rapidly, and it will likely become more widely available.

SPECIAL TRAINING REQUIRED

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is simply an ultrasonographic examination of part of the musculoskeletal system. But because not all ultrasonographic transducers offer sufficient resolution for musculoskeletal evaluation and not all sonographers and imaging physicians are familiar with the specialized techniques, musculoskeletal ultrasonography often has a separate designation (eg, “MSKUS,” “MSUS”). At Cleveland Clinic, it is offered through the department of musculoskeletal imaging by subspecialty-trained musculoskeletal radiologists and specially trained musculoskeletal ultrasonographers with 4 to 5 years of training in the technique.

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is also performed by physician groups with specialized training, including sports medicine physicians, rheumatologists, physiatrists, neurologists, and orthopedic surgeons. The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine offers voluntary accreditation for practice groups using musculoskeletal ultrasonography. Certification in musculoskeletal radiology is offered to sonographers through the American Registry for Diagnostic Medical Sonography.

SONOGRAPHY HAS UNIQUE QUALITIES

Ultrasonography uses high-frequency sound waves to generate images. The transducer (or probe) emits sound from the many piezoelectric elements at its surface, and the sound waves travel through and react with tissues. Sound reflected by tissues is detected by the transducer and converted to an image. Objects that reflect sound appear hyperechoic (brighter), whereas tissues that reflect little or no sound appear hypoechoic.

High-resolution imaging of superficial structures

(B, arrow).

Ultrasonography involves a fundamental trade-off between image resolution and imaging depth. Higher-frequency sound waves do not penetrate far into tissues but generate a higher-resolution image; lower-frequency sound waves can penetrate much further but yield a lower-resolution image. Although high-resolution imaging of deep structures with ultrasonography is not possible (Figure 1), many musculoskeletal structures are located superficially and are amenable to ultrasonographic evaluation.

Be aware of artifacts

Some materials attenuate sound very little, such as simple fluid. Low attenuation results in artifacts on ultrasonography, making tissues behind the simple fluid appear brighter than neighboring tissues. These artifacts may be reported as “increased through transmission” or “posterior acoustic enhancement.” Conversely, metal and bone reflect all sound waves that reach them, rendering any structures beyond them invisible. This “shadowing” creates a problem for imaging of structures in or near bone. Subcutaneous fat also attenuates sound waves, limiting the use of ultrasonography for patients with obesity (Figure 2).

High-frequency linear transducer sharpens images

High-frequency linear transducers reduce anisotropy because their flat surface keeps sound waves more uniformly perpendicular to the structure of interest.4,7 Their development has allowed imaging of superficial structures that is superior to that of MRI. A high-frequency linear transducer offers more than twice the spatial resolution of a typical 1.5T MRI examination of superficial tissue.12,13

Operator experience is critical

Ultrasonography examinations, more than other imaging tests, are dependent on operator experience. A solid understanding of musculoskeletal anatomy is imperative. Because the probe images only a thin section of tissue (about the thickness of a credit card), referencing adjacent structures for orientation is more difficult with ultrasonography than with CT or MRI.

The accuracy of ultrasonography is highly dependent on acquiring and interpreting images, whereas the accuracy of MRI is dependent primarily on image interpretation.7 Interpreting physicians must check that sonographers capture relevant targets.

STRENGTHS OF MUSCULOSKELETAL ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Ultrasonography has multiple advantages:

No ionizing radiation exposure.

Portability. Unlike CT or MRI, ultrasonography equipment is portable.

Increased patient comfort. Patient positioning for an ultrasonography examination is more flexible than for MRI or CT,14 and the examination does not induce claustrophobia.8

High-resolution imaging. Ultrasonography provides very-high-resolution imaging of superficial soft tissues—in some cases, higher than MRI or CT.

Real-time dynamic examinations are possible with ultrasonography, unlike with CT or MRI, and may increase test sensitivity.4,15–18

Implanted hardware is less of a problem. Although ultrasonography cannot image beyond implanted orthopedic metallic hardware, the hardware does not obscure surrounding soft tissues as it does on CT and MRI.6,19,20 Also, ultrasonography is safe for patients with a pacemaker.8

WEAKNESSES

The main disadvantages of musculoskeletal ultrasonography are inherent to its limited field of view, making it inappropriate for a survey examination (eg, for ankle pain, knee pain, hip pain).4 Unlike CT and MRI, ultrasonography does not provide a “bird’s-eye view,” and important abnormalities can be missed during evaluation of large areas (Figure 4).

Ultrasonography also cannot evaluate bone or intra-articular structures such as cartilage, bone marrow, labrum, and intra-articular ligaments; MRI is the standard for evaluating these structures.21

Ultrasonography is time-consuming. To perform a detailed examination of the anterior, posterior, medial, and lateral aspects of the hip, knee, or ankle would require 1.5 to 2 hours of scanning time and an additional 10 to 25 minutes of image checking and interpretation.

CURRENT CLINICAL INDICATIONS

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is best used for clinical questions regarding limited, superficial musculoskeletal problems.

Fluid collections

Ultrasonography can help evaluate small fluid collections in soft tissue. As is true for a lung opacity on chest radiography, soft-tissue fluid detected on ultrasonography is nonspecific, and results must be correlated with the clinical picture to narrow the differential diagnosis.

Fluid collections can be classified as loculated or nonloculated.

Nonloculated fluid involves more fluid than is simply interposed between tissue planes and has no wall or defined margins. It can be simple or complex in appearance: simple fluid is anechoic, and complex fluid appears more heterogeneous and may contain septations or debris.

Subcutaneous edema, which may occur postoperatively or from trauma, venous insufficiency, or inflammatory or infectious processes, appears on ultrasonography as nonloculated fluid interspersed between subcutaneous fat lobules.

Loculated fluid collections have well-defined margins or a discrete wall that does not follow normal tissue planes. They can also be simple or complex and can be caused by hematoma, abscess, or ganglion. Less commonly, neoplasms can mimic a loculated fluid collection (Figure 4).

A ganglion is a specific type of loculated fluid collection containing synovial fluid arising from a joint or tendon sheath. It tends to occur in specific locations, most commonly around the wrist, most often arising from the dorsal scapholunate ligament and volar wrist between the radial artery and flexor carpi radialis.22 On MRI, it can be difficult to distinguish between small vascular structures and a small ganglion, especially in the hands and feet.23

Ultrasonography can also help identify a Baker cyst, a specific fluid collection arising from the semimembranosus bursa between the medial head of the gastrocnemius tendon and the semimembranosus tendon. Ultrasonography can also detect inflammation, rupture, or leaking associated with a Baker cyst.24

Power Doppler is an ultrasonographic examination that can detect increased blood flow surrounding a fluid collection and determine the likelihood of an acute inflammatory or infectious cause.25

Joint effusion and synovitis

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography can help evaluate joints for effusion and synovitis. It is highly sensitive (94%) and specific (95%) for synovitis, making it superior to contrast-enhanced MRI.26,27 The area of concern should be limited to 1 quadrant of a joint (anterior, posterior, medial, or lateral); for problems beyond that, MRI should be considered.

A joint effusion appears as a distended joint capsule containing hypoechoic (complex) or anechoic (simple) joint fluid.

Complex joint fluid may contain debris and occurs with hemarthrosis, infection, and inflammation.23 Hypertrophied synovium is hypoechoic and can mimic complex joint fluid.

Power Doppler evaluation can help distinguish synovitis from joint fluid by demonstrating blood flow, a feature of synovitis but not of simple joint fluid. Power Doppler is the most sensitive means of detecting blood flow, although it does not show direction of flow.28

Using ultrasonography can help to improve disease control and minimize disabling changes by monitoring synovitis therapy. In addition, subclinical synovitis and enthesitis (inflammation of insertion sites of tendons or ligaments into bone) detected by ultrasonography may predict future disease and disease flares.29–31

Ultrasonographic guidance for a wide range of procedures is increasing rapidly.32–36 Multiple studies have shown the advantage of ultrasonography-guided aspiration and injection compared with techniques without imaging guidance.37,38

Soft-tissue masses

Accurately diagnosing soft-tissue masses can be difficult. A mass may remain indeterminate even after multiple imaging studies, requiring biopsy or surgical referral. However, for a few specific masses, ultrasonography is highly accurate and can eliminate the need for further imaging.

Ultrasonography can help evaluate soft- tissue masses no larger than 5 cm in diameter and no deeper than superficial muscular fascia. If the mass is larger or deeper than that, ultrasonography is less reliable for showing the margins of the mass and its relationship to adjacent structures (Figure 5). Further imaging by MRI may be recommended in such cases.

Fortunately, many of the most common soft-tissue masses can be accurately diagnosed with ultrasonography, including lipomas, ganglion cysts, foreign bodies, and simple fluid collections.4,39 Nerve-sheath tumors can also be diagnosed with ultrasonography if the lesion clearly arises from a nerve. Other soft-tissue masses are likely to be indeterminate with ultrasonography, requiring follow-up with MRI with contrast.

Tendons

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography can be effective for evaluating tendons around joints, especially 1 or a small number of nearby superficial tendons. Tendons particularly well suited for ultrasonographic examination include:

- Upper-extremity tendons located in the rotator cuff or around the elbow, and flexor and extensor tendons of the hands; ultrasonographic evaluation of the rotator cuff is highly accurate, equivalent to that of MRI for partial-thickness and full-thickness tearing40–43

- Lower-extremity tendons of the extensor mechanism of the knee, distal hamstring tendons, tendons around the ankle,44–46 and flexor and extensor tendons of the foot.

Ultrasonography can help diagnose a variety of tendon abnormalities (Table 1),48,49 including tearing, for which a dynamic examination can be performed.

Many tendons have a tendon sheath containing tenosynovium, while others have surrounding peritenon only; either can become thickened and inflamed. Tenosynovitis is a nonspecific finding and may be inflammatory, infectious, or posttraumatic. The presence of tendon sheath fluid alone on ultrasonography can be a normal finding, and some tendon sheaths that communicate with adjacent joints (eg, the long head biceps tendon, the flexor hallucis longus tendon) commonly contain simple fluid.6 A dynamic examination with ultrasonography can help diagnose snapping related to abnormal tendon movement, for example, in the case of intra-sheath and extra-sheath subluxation of the peroneal tendons.45,50,51

Ligaments

Ultrasonography can detect abnormalities in many superficial ligaments (Table 1).

Ankle. Ankle ligaments are superficial and can be clearly visualized. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for tearing of the anterior talofibular ligament may be as high as 100%.50,52,53

Elbow and thumb. The larger of the collateral ligaments of the elbow, especially the ulnar collateral ligament, and the ulnar collateral ligament of the thumb can be effectively evaluated with ultrasonography.54,55

Knee. The collateral ligaments of the knee can be seen with ultrasonography, but injuries of the external ligaments of the knee are often associated with intrinsic derangements that cannot be evaluated with ultrasonography.56,57 Intra-articular ligaments such as the anterior cruciate ligament are also not amenable to ultrasonography.

Dynamic examination of a ligament with ultrasonography can help determine the grade of the injury.

Deeply located ligaments (eg, around the hip) and ligaments surrounded by bone, such as the Lisfranc ligament, cannot be completely seen on ultrasonography.

Muscle

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is useful for small areas of concern within a muscle (Table 1). It can detect muscle strains and tears, intramuscular collections or lesions, and fascial scarring or fascial injuries such as superficial muscle herniation. Although ultrasonography may yield a definitive diagnosis for a muscle problem, further imaging may be needed.

Nerves

Ultrasonography is useful for peripheral nerve investigation but requires a steep learning curve for sonographers and interpreting physicians.58,59 It is best suited for directed questions regarding focal abnormal nerve findings on physical examination.

Ultrasonography can help identify areas of nerve entrapment caused by a mass or dynamic compression. It can detect neuritis (Table 1), lesions of peripheral nerves (eg, nerve-sheath tumors), and neuromas (eg, Morton neuroma of the intermetatarsal space). In a large meta-analysis, ultrasonography and MRI were found to be equally accurate for detecting Morton neuroma.60 Even for nerve-sheath tumors located deep to the muscular fascia, ultrasonography can confirm the diagnosis because of the characteristic appearance of the nerves. Ultrasonography can also demonstrate a large extent of the course of superficial peripheral nerves while keeping the imaging plane appropriately oriented to the nerves.

Acknowledgment: We would like to sincerely thank Megan Griffiths, MA, for her help in the preparation and submission of this manuscript.

- Hamilton JV, Flinn G Jr, Haynie CC, Cefalo RC. Diagnosis of rectus sheath hematoma by B-mode ultrasound: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1976; 125(4):562–565. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(76)90379-3

- Zweymüller VK, Kratochwil A. Ultrasound diagnosis of bone and soft tissue tumours. Wien Klin Wochenschr 1975; 87(12):397–398. German.

- Mayer V. Ultrasonography of the rotator cuff. J Ultrasound Med 1985; 4(11):608, 607. doi:10.7863/jum.1985.4.11.608

- McNally EG. The development and clinical applications of musculoskeletal ultrasound. Skeletal Radiol 2011; 40(9):1223–1231. doi:10.1007/s00256-011-1220-5

- Ignashin NS, Girshin SG, Tsypin IS. Ultrasonic scanning in subcutaneous rupture of the Achilles tendon. Vestn Khir Im I I Grek 1981; 127(9):82–85. Russian.

- Robinson P. Sonography of common tendon injuries. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 193(3):607–618. doi:10.2214/AJR.09.2808

- Jacobson JA. Musculoskeletal ultrasound: focused impact on MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 193(3):619–627. doi:10.2214/AJR.09.2841

- Nazarian LN. The top 10 reasons musculoskeletal sonography is an important complementary or alternative technique to MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 190(6):1621–1626. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.3385

- AIUM technical bulletin. Transducer manipulation. American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. J Ultrasound Med 1999; 18(2):169–175. doi:10.7863/jum.1999.18.2.169

- Connolly DJ, Berman L, McNally EG. The use of beam angulation to overcome anisotropy when viewing human tendon with high frequency linear array ultrasound. Br J Radiol 2001; 74 (878):183–185. doi:10.1259/bjr.74.878.740183

- Crass JR, van de Vegte GL, Harkavy LA. Tendon echogenicity: ex vivo study. Radiology 1988; 167(2):499–501. doi:10.1148/radiology.167.2.3282264

- Erickson SJ. High-resolution imaging of the musculoskeletal system. Radiology 1997; 205(3):593–618. doi:10.1148/radiology.205.3.9393511

- Link TM, Majumdar S, Peterfy C, et al. High resolution MRI of small joints: impact of spatial resolution on diagnostic performance and SNR. Magn Reson Imaging 1998; 16(2):147–155. doi:10.1016/S0730-725X(97)00244-0

- Middleton WD, Payne WT, Teefey SA, Hildebolt CF, Rubin DA, Yamaguchi K. Sonography and MRI of the shoulder: comparison of patient satisfaction. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 183(5):1449–1452. doi:10.2214/ajr.183.5.1831449

- Khoury V, Cardinal E, Bureau NJ. Musculoskeletal sonography: a dynamic tool for usual and unusual disorders. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 188(1):W63–W73. doi:10.2214/AJR.06.0579

- Farin PU, Jaroma H, Harju A, Soimakallio S. Medial displacement of the biceps brachii tendon: evaluation with dynamic sonography during maximal external shoulder rotation. Radiology 1995; 195(3):845–848. doi:10.1148/radiology.195.3.7754019

- Miller TT, Adler RS, Friedman L. Sonography of injury of the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow-initial experience. Skeletal Radiol 2004; 33(7):386–391. doi:10.1007/s00256-004-0788-4

- Nazarian LN, McShane JM, Ciccotti MG, O’Kane PL, Harwood MI. Dynamic US of the anterior band of the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow in asymptomatic major league baseball pitchers. Radiology 2003; 227(1):149–154. doi:10.1148/radiol.2271020288

- Jacobson JA, Lax MJ. Musculoskeletal sonography of the postoperative orthopedic patient. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2002; 6(1):67–77. doi:10.1055/s-2002-23165

- Sofka CM, Adler RS. Original report. Sonographic evaluation of shoulder arthroplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 180(4):1117–1120. doi:10.2214/ajr.180.4.1801117

- Silvestri E, Martinoli C, Derchi LE, Bertolotto M, Chiaramondia M, Rosenberg I. Echotexture of peripheral nerves: correlation between US and histologic findings and criteria to differentiate tendons. Radiology 1995; 197(1):291–296. doi:10.1148/radiology.197.1.7568840

- Cardinal E, Buckwalter KA, Braunstein EM, Mih AD. Occult dorsal carpal ganglion: comparison of US and MR imaging. Radiology 1994; 193(1):259–262. doi:10.1148/radiology.193.1.8090903

- Jacobson JA. Musculoskeletal ultrasound and MRI: which do I choose? Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2005; 9(2):135–149. doi:10.1055/s-2005-872339

- Ward EE, Jacobson JA, Fessell DP, Hayes CW, van Holsbeeck M. Sonographic detection of Baker’s cysts: comparison with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 176(2):373–380. doi:10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760373

- Bhasin S, Cheung PP. The role of power Doppler ultrasonography as disease activity marker in rheumatoid arthritis. Dis Markers 2015; 2015:325909. doi:10.1155/2015/325909

- Fukuba E, Yoshizako T, Kitagaki H, Murakawa Y, Kondo M, Uchida N. Power Doppler ultrasonography for assessment of rheumatoid synovitis: comparison with dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Imaging 2013; 37(1):134–137. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2012.02.008

- Takase-Minegishi K, Horita N, Kobayashi K, et al. Diagnostic test accuracy of ultrasound for synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018; 57(1):49–58. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kex036

- Klareskog L, Catrina AI, Paget S. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2009; 373(9664):659–672. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60008-8

- Ash ZR, Tinazzi I, Gallego CC, et al. Psoriasis patients with nail disease have a greater magnitude of underlying systemic subclinical enthesopathy than those with normal nails. Ann Rheum Dis 2012; 71(4):553–556. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200478

- Han J, Geng Y, Deng X, Zhang Z. Subclinical synovitis assessed by ultrasound predicts flare and progressive bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis patients with clinical remission: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol 2016; 43(11):2010–2018. doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.160193

- Iagnocco A, Finucci A, Ceccarelli F, Perricone C, Iorgoveanu V, Valesini G. Power Doppler ultrasound monitoring of response to anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015; 54(10):1890–1896. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kev211

- Henning PT. Ultrasound-guided foot and ankle procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2016; 27(3):649–671. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.005

- Lueders DR, Smith J, Sellon JL. Ultrasound-guided knee procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 2016; 27(3):631–648. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.010

- Payne JM. Ultrasound-guided hip procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 2016; 27(3):607–629. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.004

- Strakowski JA. Ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 2016; 27(3):687–715. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.006

- Sussman WI, Williams CJ, Mautner K. Ultrasound-guided elbow procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 2016; 27(3):573–587. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.002

- Finnoff JT. The evolution of diagnostic and interventional ultrasound in sports medicine. PM R 2016; 8(suppl 3):S133–S138. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.09.022

- Wu T, Dong Y, Song H, Fu Y, Li JH. Ultrasound-guided versus landmark in knee arthrocentesis: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016; 45(5):627–632. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.10.011

- Failla JM, van Holsbeeck M, Vanderschueren G. Detection of a 0.5-mm-thick thorn using ultrasound: a case report. J Hand Surg Am 1995; 20(3):456–457.

- Teefey SA, Hasan SA, Middleton WD, Patel M, Wright RW, Yamaguchi K. Ultrasonography of the rotator cuff. A comparison of ultrasonographic and arthroscopic findings in one hundred consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82(4):498–504.

- van Holsbeeck MT, Kolowich PA, Eyler WR, et al. US depiction of partial-thickness tear of the rotator cuff. Radiology 1995; 197(2):443–446. doi:10.1148/radiology.197.2.7480690

- Balich SM, Sheley RC, Brown TR, Sauser DD, Quinn SF. MR imaging of the rotator cuff tendon: interobserver agreement and analysis of interpretive errors. Radiology 1997; 204(1):191–194. doi:10.1148/radiology.204.1.9205245

- Dinnes J, Loveman E, McIntyre L, Waugh N. The effectiveness of diagnostic tests for the assessment of shoulder pain due to soft tissue disorders: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2003; 7(29):1–166. doi:10.3310/hta7290

- Rockett MS, Waitches G, Sudakoff G, Brage M. Use of ultrasonography versus magnetic resonance imaging for tendon abnormalities around the ankle. Foot Ankle Int 1998; 19(9):604–612.

- Grant TH, Kelikian AS, Jereb SE, McCarthy RJ. Ultrasound diagnosis of peroneal tendon tears. A surgical correlation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87(8):1788–1794. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.02450

- Hartgerink P, Fessell DP, Jacobson JA, van Holsbeeck MT. Full- versus partial-thickness Achilles tendon tears: sonographic accuracy and characterization in 26 cases with surgical correlation. Radiology 2001; 220(2):406–412. doi:10.1148/radiology.220.2.r01au41406

- Cho KH, Park BH, Yeon KM. Ultrasound of the adult hip. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2000; 21(3):214–230.

- Adler RS, Finzel KC. The complementary roles of MR imaging and ultrasound of tendons. Radiol Clin North Am 2005; 43(4):771–807. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2005.02.011

- Martinoli C, Bianchi S, Derchi LE. Tendon and nerve sonography. Radiol Clin North Am 1999; 37(4):691–711. doi:10.1016/S0033-8389(05)70124-X

- Fessell DP, Vanderschueren GM, Jacobson JA, et al. US of the ankle: technique, anatomy, and diagnosis of pathologic conditions. Radiographics 1998; 18(2):325–340. doi:10.1148/radiographics.18.2.9536481

- Neustadter J, Raikin SM, Nazarian LN. Dynamic sonographic evaluation of peroneal tendon subluxation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 183(4):985–988. doi:10.2214/ajr.183.4.1830985

- Verhaven EF, Shahabpour M, Handelberg FW, Vaes PH, Opdecam PJ. The accuracy of three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of ruptures of the lateral ligaments of the ankle. Am J Sports Med 1991; 19(6):583–587. doi:10.1177/036354659101900605

- Milz P, Milz S, Steinborn M, Mittlmeier T, Putz R, Reiser M. Lateral ankle ligaments and tibiofibular syndesmosis. 13-MHz high-frequency sonography and MRI compared in 20 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 1998; 69(1):51–55.

- De Smet AA, Winter TC, Best TM, Bernhardt DT. Dynamic sonography with valgus stress to assess elbow ulnar collateral ligament injury in baseball pitchers. Skeletal Radiol 2002; 31(11):671–676. doi:10.1007/s00256-002-0558-0

- Melville DM, Jacobson JA, Fessell DP. Ultrasound of the thumb ulnar collateral ligament: technique and pathology. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014; 202(2):W168. doi:10.2214/AJR.13.11335

- Court-Payen M. Sonography of the knee: intra-articular pathology. J Clin Ultrasound 2004; 32(9):481–490. doi:10.1002/jcu.20069

- Azzoni R, Cabitza P. Is there a role for sonography in the diagnosis of tears of the knee menisci? J Clin Ultrasound 2002; 30(8):472–476. doi:10.1002/jcu.10106

- Jacobson JA, Wilson TJ, Yang LJ. Sonography of common peripheral nerve disorders with clinical correlation. J Ultrasound Med 2016; 35(4):683–693. doi:10.7863/ultra.15.05061

- Ali ZS, Pisapia JM, Ma TS, Zager EL, Heuer GG, Khoury V. Ultrasonographic evaluation of peripheral nerves. World Neurosurg 2016; 85(1):333–339. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2015.10.005

- Bignotti B, Signori A, Sormani MP, Molfetta L, Martinoli C, Tagliafico A. Ultrasound versus magnetic resonance imaging for Morton neuroma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 2015; 25(8):2254–2262. doi:10.1007/s00330-015-3633-3

- Hamilton JV, Flinn G Jr, Haynie CC, Cefalo RC. Diagnosis of rectus sheath hematoma by B-mode ultrasound: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1976; 125(4):562–565. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(76)90379-3

- Zweymüller VK, Kratochwil A. Ultrasound diagnosis of bone and soft tissue tumours. Wien Klin Wochenschr 1975; 87(12):397–398. German.

- Mayer V. Ultrasonography of the rotator cuff. J Ultrasound Med 1985; 4(11):608, 607. doi:10.7863/jum.1985.4.11.608

- McNally EG. The development and clinical applications of musculoskeletal ultrasound. Skeletal Radiol 2011; 40(9):1223–1231. doi:10.1007/s00256-011-1220-5

- Ignashin NS, Girshin SG, Tsypin IS. Ultrasonic scanning in subcutaneous rupture of the Achilles tendon. Vestn Khir Im I I Grek 1981; 127(9):82–85. Russian.

- Robinson P. Sonography of common tendon injuries. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 193(3):607–618. doi:10.2214/AJR.09.2808

- Jacobson JA. Musculoskeletal ultrasound: focused impact on MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 193(3):619–627. doi:10.2214/AJR.09.2841

- Nazarian LN. The top 10 reasons musculoskeletal sonography is an important complementary or alternative technique to MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 190(6):1621–1626. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.3385

- AIUM technical bulletin. Transducer manipulation. American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. J Ultrasound Med 1999; 18(2):169–175. doi:10.7863/jum.1999.18.2.169

- Connolly DJ, Berman L, McNally EG. The use of beam angulation to overcome anisotropy when viewing human tendon with high frequency linear array ultrasound. Br J Radiol 2001; 74 (878):183–185. doi:10.1259/bjr.74.878.740183

- Crass JR, van de Vegte GL, Harkavy LA. Tendon echogenicity: ex vivo study. Radiology 1988; 167(2):499–501. doi:10.1148/radiology.167.2.3282264

- Erickson SJ. High-resolution imaging of the musculoskeletal system. Radiology 1997; 205(3):593–618. doi:10.1148/radiology.205.3.9393511

- Link TM, Majumdar S, Peterfy C, et al. High resolution MRI of small joints: impact of spatial resolution on diagnostic performance and SNR. Magn Reson Imaging 1998; 16(2):147–155. doi:10.1016/S0730-725X(97)00244-0

- Middleton WD, Payne WT, Teefey SA, Hildebolt CF, Rubin DA, Yamaguchi K. Sonography and MRI of the shoulder: comparison of patient satisfaction. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004; 183(5):1449–1452. doi:10.2214/ajr.183.5.1831449

- Khoury V, Cardinal E, Bureau NJ. Musculoskeletal sonography: a dynamic tool for usual and unusual disorders. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 188(1):W63–W73. doi:10.2214/AJR.06.0579

- Farin PU, Jaroma H, Harju A, Soimakallio S. Medial displacement of the biceps brachii tendon: evaluation with dynamic sonography during maximal external shoulder rotation. Radiology 1995; 195(3):845–848. doi:10.1148/radiology.195.3.7754019

- Miller TT, Adler RS, Friedman L. Sonography of injury of the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow-initial experience. Skeletal Radiol 2004; 33(7):386–391. doi:10.1007/s00256-004-0788-4

- Nazarian LN, McShane JM, Ciccotti MG, O’Kane PL, Harwood MI. Dynamic US of the anterior band of the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow in asymptomatic major league baseball pitchers. Radiology 2003; 227(1):149–154. doi:10.1148/radiol.2271020288

- Jacobson JA, Lax MJ. Musculoskeletal sonography of the postoperative orthopedic patient. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2002; 6(1):67–77. doi:10.1055/s-2002-23165

- Sofka CM, Adler RS. Original report. Sonographic evaluation of shoulder arthroplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 180(4):1117–1120. doi:10.2214/ajr.180.4.1801117

- Silvestri E, Martinoli C, Derchi LE, Bertolotto M, Chiaramondia M, Rosenberg I. Echotexture of peripheral nerves: correlation between US and histologic findings and criteria to differentiate tendons. Radiology 1995; 197(1):291–296. doi:10.1148/radiology.197.1.7568840

- Cardinal E, Buckwalter KA, Braunstein EM, Mih AD. Occult dorsal carpal ganglion: comparison of US and MR imaging. Radiology 1994; 193(1):259–262. doi:10.1148/radiology.193.1.8090903

- Jacobson JA. Musculoskeletal ultrasound and MRI: which do I choose? Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2005; 9(2):135–149. doi:10.1055/s-2005-872339

- Ward EE, Jacobson JA, Fessell DP, Hayes CW, van Holsbeeck M. Sonographic detection of Baker’s cysts: comparison with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 176(2):373–380. doi:10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760373

- Bhasin S, Cheung PP. The role of power Doppler ultrasonography as disease activity marker in rheumatoid arthritis. Dis Markers 2015; 2015:325909. doi:10.1155/2015/325909

- Fukuba E, Yoshizako T, Kitagaki H, Murakawa Y, Kondo M, Uchida N. Power Doppler ultrasonography for assessment of rheumatoid synovitis: comparison with dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Imaging 2013; 37(1):134–137. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2012.02.008

- Takase-Minegishi K, Horita N, Kobayashi K, et al. Diagnostic test accuracy of ultrasound for synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018; 57(1):49–58. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kex036

- Klareskog L, Catrina AI, Paget S. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2009; 373(9664):659–672. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60008-8

- Ash ZR, Tinazzi I, Gallego CC, et al. Psoriasis patients with nail disease have a greater magnitude of underlying systemic subclinical enthesopathy than those with normal nails. Ann Rheum Dis 2012; 71(4):553–556. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200478

- Han J, Geng Y, Deng X, Zhang Z. Subclinical synovitis assessed by ultrasound predicts flare and progressive bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis patients with clinical remission: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol 2016; 43(11):2010–2018. doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.160193

- Iagnocco A, Finucci A, Ceccarelli F, Perricone C, Iorgoveanu V, Valesini G. Power Doppler ultrasound monitoring of response to anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015; 54(10):1890–1896. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kev211

- Henning PT. Ultrasound-guided foot and ankle procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2016; 27(3):649–671. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.005

- Lueders DR, Smith J, Sellon JL. Ultrasound-guided knee procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 2016; 27(3):631–648. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.010

- Payne JM. Ultrasound-guided hip procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 2016; 27(3):607–629. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.004

- Strakowski JA. Ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 2016; 27(3):687–715. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.006

- Sussman WI, Williams CJ, Mautner K. Ultrasound-guided elbow procedures. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am 2016; 27(3):573–587. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2016.04.002