User login

Congress has appropriated an additional $414 million for research into Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias – the full increase requested by the National Institutes of Health for fiscal year 2018. The boost brings the total AD funding available this year to $1.8 billion.

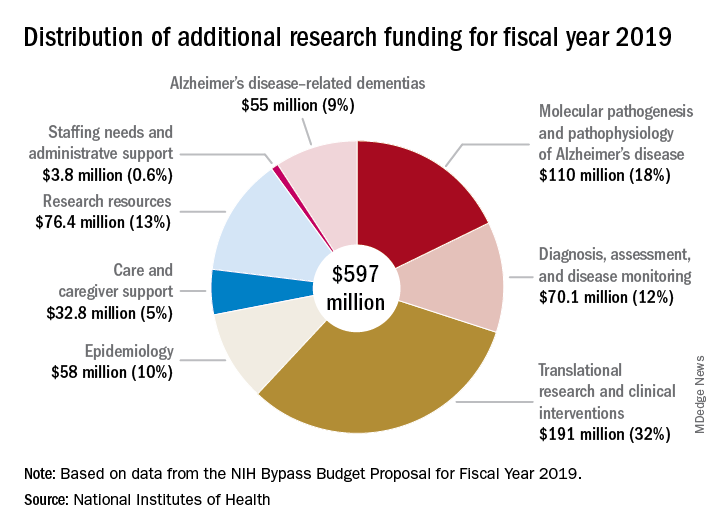

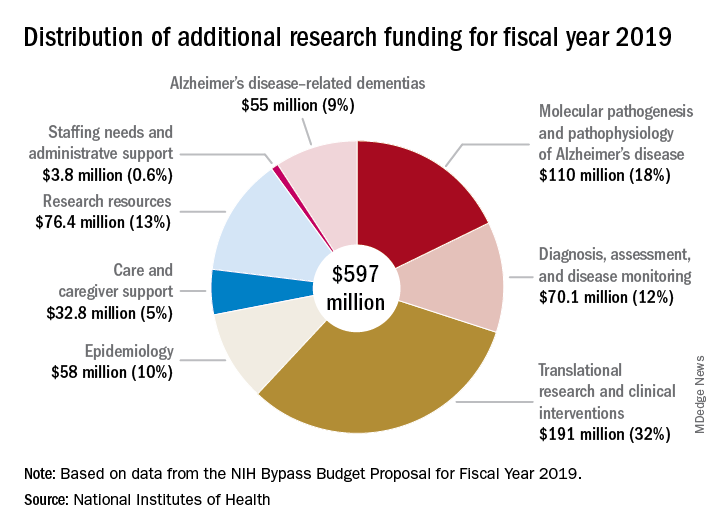

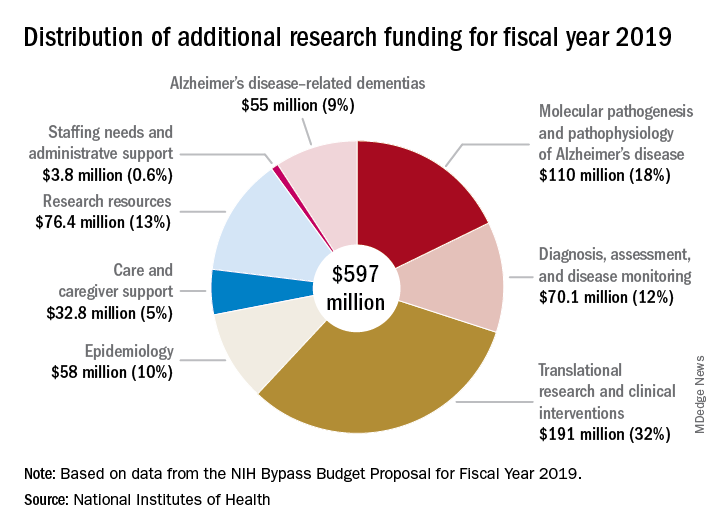

Bolstered by the mandate of the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease, to prevent or treat AD by 2025, the NIH is aiming higher still. Its draft FY2019 AD appropriation asks for another $597 million; if passed, nearly $2.4 billion could be available for AD research as soon as next October.

“For the third consecutive fiscal year, Congress has approved the Alzheimer’s Association’s appeal for a historic funding increase for Alzheimer’s and dementia research at the NIH,” Alzheimer’s Association president Harry Johns said in a press statement. “This decision demonstrates that Congress is deeply committed to providing the Alzheimer’s and dementia science community with the resources needed to move research forward.”

Several members of Congress championed the AD funding request, including Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), Patty Murray (D-Wash.), Nita Lowey (D-N.Y.), and Tom Cole (R-Okla.).

The forward momentum is on pace to continue into FY2019, according to Robert Egge, chief public policy officer and executive vice president of governmental affairs for the association. The NIH Bypass Budget, an estimate of how much additional funding is necessary to reach the 2025 goal, contains an additional $597 million appropriation for AD and other dementias.

“This is what we need to fund scientific projects that are meritorious and ready to go,” Mr. Egge said in an interview. “Congress has the assurance that this request is scientifically driven and that NIH is already thinking about how the money will be used.”

While a record-setting amount in the AD research world, this year’s $1.8 billion appropriation is a fraction of what other costly diseases receive. By comparison, the budget granted the National Cancer Institute $5.7 billion for its research programs.

“Compared to what the cost of the disease brings to Americans in terms of Medicare, Medicaid, and out of pocket expenses, it’s not that much,” Mr. Egge said. “But we have the opportunity to use this money to change these huge numbers that we’re facing.”

A 2013 report by the Rand Corporation found that, although Alzheimer’s affects fewer people than cancer or heart disease, the cost of treating and caring for those patients far outstrips spending in either of those other categories. The conclusions were perhaps even more startling, considering that it looked only at costs related solely to Alzheimer’s, not the cost of treating comorbid illnesses.

Long-term care was a key driver of the total cost in 2013, and remains the bulk of expenses today, Mr. Egge said. Transitions – going from home to nursing home to hospital – are terribly expensive, he noted. And although the Rand report didn’t include it, managing comorbid illnesses in Alzheimer’s is an enormous money drain. “Diabetes is just one example. It costs 80% more to manage diabetes in a patient with AD than in one without AD.”

The Facts and Figures report notes that the average 2017 per-person payout for Medicare beneficiaries was more than three times higher in AD patients than in those without the disease ($48,028 vs. $13,705). These are the kinds of numbers it takes to put partisan bickering on hold and grapple with tough decisions, Mr. Egge said.

“The fiscal argument is one thing that really impressed Congress. They do know how worried Americans are about this disease and how tough it is on families, but the growing fiscal impact has really focused them on addressing it.”

Congress has appropriated an additional $414 million for research into Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias – the full increase requested by the National Institutes of Health for fiscal year 2018. The boost brings the total AD funding available this year to $1.8 billion.

Bolstered by the mandate of the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease, to prevent or treat AD by 2025, the NIH is aiming higher still. Its draft FY2019 AD appropriation asks for another $597 million; if passed, nearly $2.4 billion could be available for AD research as soon as next October.

“For the third consecutive fiscal year, Congress has approved the Alzheimer’s Association’s appeal for a historic funding increase for Alzheimer’s and dementia research at the NIH,” Alzheimer’s Association president Harry Johns said in a press statement. “This decision demonstrates that Congress is deeply committed to providing the Alzheimer’s and dementia science community with the resources needed to move research forward.”

Several members of Congress championed the AD funding request, including Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), Patty Murray (D-Wash.), Nita Lowey (D-N.Y.), and Tom Cole (R-Okla.).

The forward momentum is on pace to continue into FY2019, according to Robert Egge, chief public policy officer and executive vice president of governmental affairs for the association. The NIH Bypass Budget, an estimate of how much additional funding is necessary to reach the 2025 goal, contains an additional $597 million appropriation for AD and other dementias.

“This is what we need to fund scientific projects that are meritorious and ready to go,” Mr. Egge said in an interview. “Congress has the assurance that this request is scientifically driven and that NIH is already thinking about how the money will be used.”

While a record-setting amount in the AD research world, this year’s $1.8 billion appropriation is a fraction of what other costly diseases receive. By comparison, the budget granted the National Cancer Institute $5.7 billion for its research programs.

“Compared to what the cost of the disease brings to Americans in terms of Medicare, Medicaid, and out of pocket expenses, it’s not that much,” Mr. Egge said. “But we have the opportunity to use this money to change these huge numbers that we’re facing.”

A 2013 report by the Rand Corporation found that, although Alzheimer’s affects fewer people than cancer or heart disease, the cost of treating and caring for those patients far outstrips spending in either of those other categories. The conclusions were perhaps even more startling, considering that it looked only at costs related solely to Alzheimer’s, not the cost of treating comorbid illnesses.

Long-term care was a key driver of the total cost in 2013, and remains the bulk of expenses today, Mr. Egge said. Transitions – going from home to nursing home to hospital – are terribly expensive, he noted. And although the Rand report didn’t include it, managing comorbid illnesses in Alzheimer’s is an enormous money drain. “Diabetes is just one example. It costs 80% more to manage diabetes in a patient with AD than in one without AD.”

The Facts and Figures report notes that the average 2017 per-person payout for Medicare beneficiaries was more than three times higher in AD patients than in those without the disease ($48,028 vs. $13,705). These are the kinds of numbers it takes to put partisan bickering on hold and grapple with tough decisions, Mr. Egge said.

“The fiscal argument is one thing that really impressed Congress. They do know how worried Americans are about this disease and how tough it is on families, but the growing fiscal impact has really focused them on addressing it.”

Congress has appropriated an additional $414 million for research into Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias – the full increase requested by the National Institutes of Health for fiscal year 2018. The boost brings the total AD funding available this year to $1.8 billion.

Bolstered by the mandate of the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease, to prevent or treat AD by 2025, the NIH is aiming higher still. Its draft FY2019 AD appropriation asks for another $597 million; if passed, nearly $2.4 billion could be available for AD research as soon as next October.

“For the third consecutive fiscal year, Congress has approved the Alzheimer’s Association’s appeal for a historic funding increase for Alzheimer’s and dementia research at the NIH,” Alzheimer’s Association president Harry Johns said in a press statement. “This decision demonstrates that Congress is deeply committed to providing the Alzheimer’s and dementia science community with the resources needed to move research forward.”

Several members of Congress championed the AD funding request, including Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), Patty Murray (D-Wash.), Nita Lowey (D-N.Y.), and Tom Cole (R-Okla.).

The forward momentum is on pace to continue into FY2019, according to Robert Egge, chief public policy officer and executive vice president of governmental affairs for the association. The NIH Bypass Budget, an estimate of how much additional funding is necessary to reach the 2025 goal, contains an additional $597 million appropriation for AD and other dementias.

“This is what we need to fund scientific projects that are meritorious and ready to go,” Mr. Egge said in an interview. “Congress has the assurance that this request is scientifically driven and that NIH is already thinking about how the money will be used.”

While a record-setting amount in the AD research world, this year’s $1.8 billion appropriation is a fraction of what other costly diseases receive. By comparison, the budget granted the National Cancer Institute $5.7 billion for its research programs.

“Compared to what the cost of the disease brings to Americans in terms of Medicare, Medicaid, and out of pocket expenses, it’s not that much,” Mr. Egge said. “But we have the opportunity to use this money to change these huge numbers that we’re facing.”

A 2013 report by the Rand Corporation found that, although Alzheimer’s affects fewer people than cancer or heart disease, the cost of treating and caring for those patients far outstrips spending in either of those other categories. The conclusions were perhaps even more startling, considering that it looked only at costs related solely to Alzheimer’s, not the cost of treating comorbid illnesses.

Long-term care was a key driver of the total cost in 2013, and remains the bulk of expenses today, Mr. Egge said. Transitions – going from home to nursing home to hospital – are terribly expensive, he noted. And although the Rand report didn’t include it, managing comorbid illnesses in Alzheimer’s is an enormous money drain. “Diabetes is just one example. It costs 80% more to manage diabetes in a patient with AD than in one without AD.”

The Facts and Figures report notes that the average 2017 per-person payout for Medicare beneficiaries was more than three times higher in AD patients than in those without the disease ($48,028 vs. $13,705). These are the kinds of numbers it takes to put partisan bickering on hold and grapple with tough decisions, Mr. Egge said.

“The fiscal argument is one thing that really impressed Congress. They do know how worried Americans are about this disease and how tough it is on families, but the growing fiscal impact has really focused them on addressing it.”