User login

Recurrence of a small gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor with high mitotic index

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract, usually arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal or similar cells in the outer wall of the gastrointestinal tract.1,2 Most GISTs have an activating mutation in KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Tumor size, mitotic rate, and anatomic site are the most common pathological features used to risk stratify GIST tumors.3-10 It is important to note when using such risk calculators that preoperative imatinib before determining tumor characteristics (such as mitoses per 50 high-power fields [hpf]) often changes the relevant parameters so that the same risk calculations may not apply. Tumors with a mitotic rate ≤5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size ≤5 cm in greatest dimension have a lower recurrence rate after resection than tumors with a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size >10 cm, and larger tumors can have a recurrence rate of up to 86%.11,12 Findings from a large observational study have suggested that the prognosis of gastric GIST in Korea and Japan may be more favorable compared with that in Western countries.13

The primary treatment of a localized primary GIST is surgical excision, but a cure is limited by recurrence.14,15 Imatinib is useful in the treatment of metastatic or recurrent GIST, and adjuvant treatment with imatinib after surgery has been shown to improve progression-free and overall survival in some cases.3,16-18 Responses to adjuvant imatinib depend on tumor sensitivity to the drug and the risk of recurrence. Drug sensitivity is largely dependent on the presence of mutations in KIT or PDGFRA.3,18 Recurrence risk is highly dependent on tumor size, tumor site, tumor rupture, and mitotic index.1,3,5,6,8,9,18,19 Findings on the use of gene expression patterns to predict recurrence risk have also been reported.20-27 However, recurrence risk is poorly understood for categories in which there are few cases with known outcomes, such as very small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index. For example, few cases of gastric GIST have been reported with a tumor size ≤2 cm, a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf, and adequate clinical follow-up. In such cases, it is difficult to assess the risk of recurrence.6 We report here the long-term outcome of a patient with a 1.8 cm gastric GIST with a mitotic index of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf and a KIT exon 11 mutation.

Case presentation and summary

A 69-year-old man presented with periumbilical and epigastric pain of 6-month duration. His medical history was notable for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary angioplasty, and spinal surgery. He had a 40 pack-year smoking history and consumed 2 to 4 alcoholic drinks per day. The results of a physical examination were unremarkable. A computedtomographic (CT) scan showed no abnormalities. An esophagoduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed gastric ulcers. He was treated successfully with omeprazole 20 mg by mouth daily.

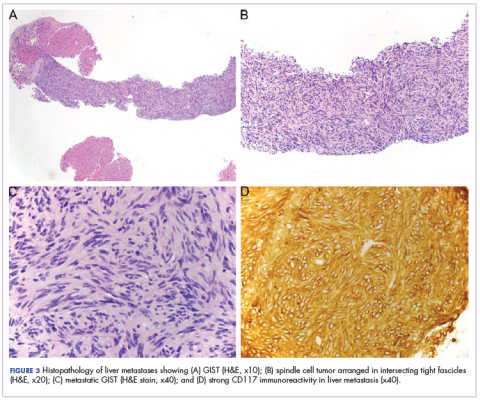

A month later, a follow-up EGD revealed a 1.8 × 1.5 cm submucosal mass 3 cm from the gastroesophageal junction. The patient underwent a fundus wedge resection, and a submucosal mass 1.8 cm in greatest dimension was removed. Pathologic examination revealed a GIST, spindle cell type, with a mitotic rate of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf with negative margins. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD117. An exon 11 deletion (KVV558-560NV) was present in KIT. The patient’s risk of recurrence was unclear, and his follow-up included CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis every 3 to 4 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for the next 2.5 years.

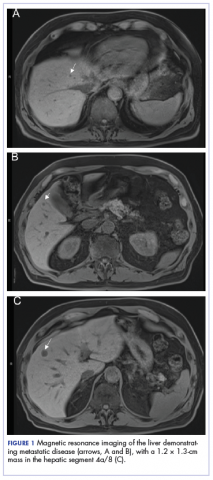

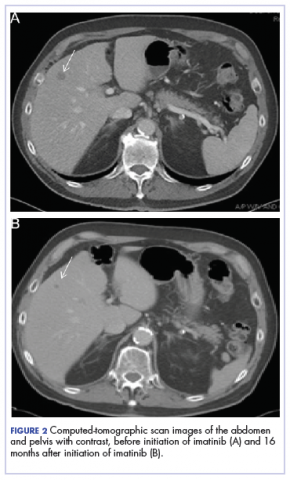

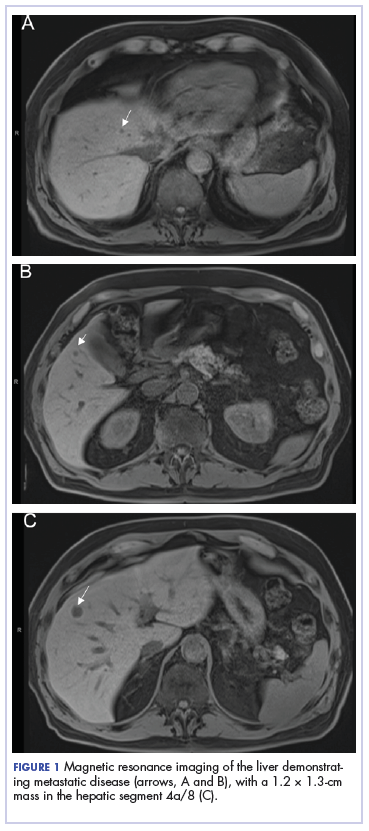

A CT scan about 3.5 years after primary resection revealed small nonspecific liver hypodensities that became more prominent during the next year. About 5 years after primary resection, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed several liver lesions, the largest of which measured at 1.3 cm in greatest dimension. The patient’s liver metastases were readily identified by MRI (Figure 1) and CT imaging (Figure 2A).

Discussion

Small gastric GISTs are sometimes found by endoscopy performed for unrelated reasons. Recent data suggest that the incidence of gastric GIST may be higher than previously thought. In a Japanese study of patients with gastric cancer in which 100 stomachs were systematically examined pathologically, 50 microscopic GISTs were found in 35 patients.28 Most small gastric GISTs have a low mitotic index. Few cases have been described with a high mitotic index. In a study of 1765 cases of GIST of the stomach, 8 patients had a tumor size less than 2 cm and a mitotic index greater than 5. Of those, only 6 patients had long-term follow-up, and 3 were alive without disease at 2, 17, and 20 years of follow-up.7 These limited data make it impossible to predict outcomes in patients with small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index.

For patients who are at high risk of recurrence after surgery, 3 years of adjuvant imatinib treatment compared with 1 year has been shown to improve overall survival and is the current standard of care.10,17 A study comparing 5 and 3 years of imatinib is ongoing to establish whether a longer period of adjuvant treatment is warranted. In patients with metastatic GIST, lifelong imatinib until lack of benefit is considered optimal treatment.10 All patients should undergo KIT mutation analysis. Those with the PDGFRA D842V mutation, SDH (succinate dehydrogenase) deficiency, or neurofibromatosis-related GIST should not receive adjuvant imatinib.

This case has several unusual features. The small tumor size with a very high mitotic rate is rare. Such cases have not been reported in large numbers and have therefore not been reliably incorporated into risk prediction algorithms. In addition, despite a high mitotic index, the tumor was not FDG avid on PET imaging. The diagnosis of GIST is strongly supported by the KIT mutation and response to imatinib. This particular KIT mutation in larger GISTs is associated with aggressive disease. The present case adds to the data on the biology of small gastric GISTs with a high mitotic index and suggests the mitotic index in these tumors may be a more important predictor than size.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Michael Franklin, MS, for editorial assistance, and Sabrina Porter for media edits.

1. Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):865-878.

2. Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(5350):577-580.

3. Corless CL, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Pathologic and molecular features correlate with long-term outcome after adjuvant therapy of resected primary GI stromal tumor: the ACOSOG Z9001 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1563-1570.

4. Huang J, Zheng DL, Qin FS, et al. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of SCARA5 may contribute to human hepatocellular carcinoma by activating FAK signaling. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(1):223-241.

5. Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimaki J, et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):265-274.

6. Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(10):1466-1478.

7. Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(1):52-68.

8. Patel S. Navigating risk stratification systems for the management of patients with GIST. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1698-1704.

9. Rossi S, Miceli R, Messerini L, et al. Natural history of imatinib-naive GISTs: a retrospective analysis of 929 cases with long-term follow-up and development of a survival nomogram based on mitotic index and size as continuous variables. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(11):1646-1656.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Sarcoma. https://www.nccn.org. Accessed March 27, 2018.

11. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10(2):81-89.

12. Huang HY, Li CF, Huang WW, et al. A modification of NIH consensus criteria to better distinguish the highly lethal subset of primary localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a subdivision of the original high-risk group on the basis of outcome. Surgery. 2007;141(6):748-756.

13. Kim MC, Yook JH, Yang HK, et al. Long-term surgical outcome of 1057 gastric GISTs according to 7th UICC/AJCC TNM system: multicenter observational study From Korea and Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(41):e1526.

14. Casali PG, Blay JY; ESMO/CONTICANET/EUROBONET Consensus Panel of experts. Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v198-v203.

15. Joensuu H, DeMatteo RP. The management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a model for targeted and multidisciplinary therapy of malignancy. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:247-258.

16. Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1097-1104.

17. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, et al. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(12):1265-1272.

18. Joensuu H, Rutkowski P, Nishida T, et al. KIT and PDGFRA mutations and the risk of GI stromal tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):634-642.

19. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):459-465.

20. Antonescu CR, Viale A, Sarran L, et al. Gene expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumors is distinguished by KIT genotype and anatomic site. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3282-3290.

21. Arne G, Kristiansson E, Nerman O, et al. Expression profiling of GIST: CD133 is associated with KIT exon 11 mutations, gastric location and poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(5):1149-1161.

22. Bertucci F, Finetti P, Ostrowski J, et al. Genomic Grade Index predicts postoperative clinical outcome of GIST. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(8):1433-1441.

23. Koon N, Schneider-Stock R, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Molecular targets for tumour progression in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Gut. 2004;53(2):235-240.

24. Lagarde P, Perot G, Kauffmann A, et al. Mitotic checkpoints and chromosome instability are strong predictors of clinical outcome in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):826-838.

25. Skubitz KM, Geschwind K, Xu WW, Koopmeiners JS, Skubitz AP. Gene expression identifies heterogeneity of metastatic behavior among gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Transl Med. 2016;14:51.

26. Yamaguchi U, Nakayama R, Honda K, et al. Distinct gene expression-defined classes of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4100-4108.

27. Ylipaa A, Hunt KK, Yang J, et al. Integrative genomic characterization and a genomic staging system for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer. 2011;117(2):380-389.

28. Kawanowa K, Sakuma Y, Sakurai S, et al. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(12):1527-1535.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract, usually arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal or similar cells in the outer wall of the gastrointestinal tract.1,2 Most GISTs have an activating mutation in KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Tumor size, mitotic rate, and anatomic site are the most common pathological features used to risk stratify GIST tumors.3-10 It is important to note when using such risk calculators that preoperative imatinib before determining tumor characteristics (such as mitoses per 50 high-power fields [hpf]) often changes the relevant parameters so that the same risk calculations may not apply. Tumors with a mitotic rate ≤5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size ≤5 cm in greatest dimension have a lower recurrence rate after resection than tumors with a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size >10 cm, and larger tumors can have a recurrence rate of up to 86%.11,12 Findings from a large observational study have suggested that the prognosis of gastric GIST in Korea and Japan may be more favorable compared with that in Western countries.13

The primary treatment of a localized primary GIST is surgical excision, but a cure is limited by recurrence.14,15 Imatinib is useful in the treatment of metastatic or recurrent GIST, and adjuvant treatment with imatinib after surgery has been shown to improve progression-free and overall survival in some cases.3,16-18 Responses to adjuvant imatinib depend on tumor sensitivity to the drug and the risk of recurrence. Drug sensitivity is largely dependent on the presence of mutations in KIT or PDGFRA.3,18 Recurrence risk is highly dependent on tumor size, tumor site, tumor rupture, and mitotic index.1,3,5,6,8,9,18,19 Findings on the use of gene expression patterns to predict recurrence risk have also been reported.20-27 However, recurrence risk is poorly understood for categories in which there are few cases with known outcomes, such as very small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index. For example, few cases of gastric GIST have been reported with a tumor size ≤2 cm, a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf, and adequate clinical follow-up. In such cases, it is difficult to assess the risk of recurrence.6 We report here the long-term outcome of a patient with a 1.8 cm gastric GIST with a mitotic index of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf and a KIT exon 11 mutation.

Case presentation and summary

A 69-year-old man presented with periumbilical and epigastric pain of 6-month duration. His medical history was notable for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary angioplasty, and spinal surgery. He had a 40 pack-year smoking history and consumed 2 to 4 alcoholic drinks per day. The results of a physical examination were unremarkable. A computedtomographic (CT) scan showed no abnormalities. An esophagoduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed gastric ulcers. He was treated successfully with omeprazole 20 mg by mouth daily.

A month later, a follow-up EGD revealed a 1.8 × 1.5 cm submucosal mass 3 cm from the gastroesophageal junction. The patient underwent a fundus wedge resection, and a submucosal mass 1.8 cm in greatest dimension was removed. Pathologic examination revealed a GIST, spindle cell type, with a mitotic rate of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf with negative margins. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD117. An exon 11 deletion (KVV558-560NV) was present in KIT. The patient’s risk of recurrence was unclear, and his follow-up included CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis every 3 to 4 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for the next 2.5 years.

A CT scan about 3.5 years after primary resection revealed small nonspecific liver hypodensities that became more prominent during the next year. About 5 years after primary resection, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed several liver lesions, the largest of which measured at 1.3 cm in greatest dimension. The patient’s liver metastases were readily identified by MRI (Figure 1) and CT imaging (Figure 2A).

Discussion

Small gastric GISTs are sometimes found by endoscopy performed for unrelated reasons. Recent data suggest that the incidence of gastric GIST may be higher than previously thought. In a Japanese study of patients with gastric cancer in which 100 stomachs were systematically examined pathologically, 50 microscopic GISTs were found in 35 patients.28 Most small gastric GISTs have a low mitotic index. Few cases have been described with a high mitotic index. In a study of 1765 cases of GIST of the stomach, 8 patients had a tumor size less than 2 cm and a mitotic index greater than 5. Of those, only 6 patients had long-term follow-up, and 3 were alive without disease at 2, 17, and 20 years of follow-up.7 These limited data make it impossible to predict outcomes in patients with small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index.

For patients who are at high risk of recurrence after surgery, 3 years of adjuvant imatinib treatment compared with 1 year has been shown to improve overall survival and is the current standard of care.10,17 A study comparing 5 and 3 years of imatinib is ongoing to establish whether a longer period of adjuvant treatment is warranted. In patients with metastatic GIST, lifelong imatinib until lack of benefit is considered optimal treatment.10 All patients should undergo KIT mutation analysis. Those with the PDGFRA D842V mutation, SDH (succinate dehydrogenase) deficiency, or neurofibromatosis-related GIST should not receive adjuvant imatinib.

This case has several unusual features. The small tumor size with a very high mitotic rate is rare. Such cases have not been reported in large numbers and have therefore not been reliably incorporated into risk prediction algorithms. In addition, despite a high mitotic index, the tumor was not FDG avid on PET imaging. The diagnosis of GIST is strongly supported by the KIT mutation and response to imatinib. This particular KIT mutation in larger GISTs is associated with aggressive disease. The present case adds to the data on the biology of small gastric GISTs with a high mitotic index and suggests the mitotic index in these tumors may be a more important predictor than size.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Michael Franklin, MS, for editorial assistance, and Sabrina Porter for media edits.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract, usually arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal or similar cells in the outer wall of the gastrointestinal tract.1,2 Most GISTs have an activating mutation in KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Tumor size, mitotic rate, and anatomic site are the most common pathological features used to risk stratify GIST tumors.3-10 It is important to note when using such risk calculators that preoperative imatinib before determining tumor characteristics (such as mitoses per 50 high-power fields [hpf]) often changes the relevant parameters so that the same risk calculations may not apply. Tumors with a mitotic rate ≤5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size ≤5 cm in greatest dimension have a lower recurrence rate after resection than tumors with a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size >10 cm, and larger tumors can have a recurrence rate of up to 86%.11,12 Findings from a large observational study have suggested that the prognosis of gastric GIST in Korea and Japan may be more favorable compared with that in Western countries.13

The primary treatment of a localized primary GIST is surgical excision, but a cure is limited by recurrence.14,15 Imatinib is useful in the treatment of metastatic or recurrent GIST, and adjuvant treatment with imatinib after surgery has been shown to improve progression-free and overall survival in some cases.3,16-18 Responses to adjuvant imatinib depend on tumor sensitivity to the drug and the risk of recurrence. Drug sensitivity is largely dependent on the presence of mutations in KIT or PDGFRA.3,18 Recurrence risk is highly dependent on tumor size, tumor site, tumor rupture, and mitotic index.1,3,5,6,8,9,18,19 Findings on the use of gene expression patterns to predict recurrence risk have also been reported.20-27 However, recurrence risk is poorly understood for categories in which there are few cases with known outcomes, such as very small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index. For example, few cases of gastric GIST have been reported with a tumor size ≤2 cm, a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf, and adequate clinical follow-up. In such cases, it is difficult to assess the risk of recurrence.6 We report here the long-term outcome of a patient with a 1.8 cm gastric GIST with a mitotic index of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf and a KIT exon 11 mutation.

Case presentation and summary

A 69-year-old man presented with periumbilical and epigastric pain of 6-month duration. His medical history was notable for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary angioplasty, and spinal surgery. He had a 40 pack-year smoking history and consumed 2 to 4 alcoholic drinks per day. The results of a physical examination were unremarkable. A computedtomographic (CT) scan showed no abnormalities. An esophagoduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed gastric ulcers. He was treated successfully with omeprazole 20 mg by mouth daily.

A month later, a follow-up EGD revealed a 1.8 × 1.5 cm submucosal mass 3 cm from the gastroesophageal junction. The patient underwent a fundus wedge resection, and a submucosal mass 1.8 cm in greatest dimension was removed. Pathologic examination revealed a GIST, spindle cell type, with a mitotic rate of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf with negative margins. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD117. An exon 11 deletion (KVV558-560NV) was present in KIT. The patient’s risk of recurrence was unclear, and his follow-up included CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis every 3 to 4 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for the next 2.5 years.

A CT scan about 3.5 years after primary resection revealed small nonspecific liver hypodensities that became more prominent during the next year. About 5 years after primary resection, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed several liver lesions, the largest of which measured at 1.3 cm in greatest dimension. The patient’s liver metastases were readily identified by MRI (Figure 1) and CT imaging (Figure 2A).

Discussion

Small gastric GISTs are sometimes found by endoscopy performed for unrelated reasons. Recent data suggest that the incidence of gastric GIST may be higher than previously thought. In a Japanese study of patients with gastric cancer in which 100 stomachs were systematically examined pathologically, 50 microscopic GISTs were found in 35 patients.28 Most small gastric GISTs have a low mitotic index. Few cases have been described with a high mitotic index. In a study of 1765 cases of GIST of the stomach, 8 patients had a tumor size less than 2 cm and a mitotic index greater than 5. Of those, only 6 patients had long-term follow-up, and 3 were alive without disease at 2, 17, and 20 years of follow-up.7 These limited data make it impossible to predict outcomes in patients with small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index.

For patients who are at high risk of recurrence after surgery, 3 years of adjuvant imatinib treatment compared with 1 year has been shown to improve overall survival and is the current standard of care.10,17 A study comparing 5 and 3 years of imatinib is ongoing to establish whether a longer period of adjuvant treatment is warranted. In patients with metastatic GIST, lifelong imatinib until lack of benefit is considered optimal treatment.10 All patients should undergo KIT mutation analysis. Those with the PDGFRA D842V mutation, SDH (succinate dehydrogenase) deficiency, or neurofibromatosis-related GIST should not receive adjuvant imatinib.

This case has several unusual features. The small tumor size with a very high mitotic rate is rare. Such cases have not been reported in large numbers and have therefore not been reliably incorporated into risk prediction algorithms. In addition, despite a high mitotic index, the tumor was not FDG avid on PET imaging. The diagnosis of GIST is strongly supported by the KIT mutation and response to imatinib. This particular KIT mutation in larger GISTs is associated with aggressive disease. The present case adds to the data on the biology of small gastric GISTs with a high mitotic index and suggests the mitotic index in these tumors may be a more important predictor than size.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Michael Franklin, MS, for editorial assistance, and Sabrina Porter for media edits.

1. Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):865-878.

2. Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(5350):577-580.

3. Corless CL, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Pathologic and molecular features correlate with long-term outcome after adjuvant therapy of resected primary GI stromal tumor: the ACOSOG Z9001 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1563-1570.

4. Huang J, Zheng DL, Qin FS, et al. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of SCARA5 may contribute to human hepatocellular carcinoma by activating FAK signaling. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(1):223-241.

5. Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimaki J, et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):265-274.

6. Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(10):1466-1478.

7. Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(1):52-68.

8. Patel S. Navigating risk stratification systems for the management of patients with GIST. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1698-1704.

9. Rossi S, Miceli R, Messerini L, et al. Natural history of imatinib-naive GISTs: a retrospective analysis of 929 cases with long-term follow-up and development of a survival nomogram based on mitotic index and size as continuous variables. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(11):1646-1656.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Sarcoma. https://www.nccn.org. Accessed March 27, 2018.

11. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10(2):81-89.

12. Huang HY, Li CF, Huang WW, et al. A modification of NIH consensus criteria to better distinguish the highly lethal subset of primary localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a subdivision of the original high-risk group on the basis of outcome. Surgery. 2007;141(6):748-756.

13. Kim MC, Yook JH, Yang HK, et al. Long-term surgical outcome of 1057 gastric GISTs according to 7th UICC/AJCC TNM system: multicenter observational study From Korea and Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(41):e1526.

14. Casali PG, Blay JY; ESMO/CONTICANET/EUROBONET Consensus Panel of experts. Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v198-v203.

15. Joensuu H, DeMatteo RP. The management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a model for targeted and multidisciplinary therapy of malignancy. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:247-258.

16. Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1097-1104.

17. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, et al. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(12):1265-1272.

18. Joensuu H, Rutkowski P, Nishida T, et al. KIT and PDGFRA mutations and the risk of GI stromal tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):634-642.

19. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):459-465.

20. Antonescu CR, Viale A, Sarran L, et al. Gene expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumors is distinguished by KIT genotype and anatomic site. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3282-3290.

21. Arne G, Kristiansson E, Nerman O, et al. Expression profiling of GIST: CD133 is associated with KIT exon 11 mutations, gastric location and poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(5):1149-1161.

22. Bertucci F, Finetti P, Ostrowski J, et al. Genomic Grade Index predicts postoperative clinical outcome of GIST. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(8):1433-1441.

23. Koon N, Schneider-Stock R, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Molecular targets for tumour progression in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Gut. 2004;53(2):235-240.

24. Lagarde P, Perot G, Kauffmann A, et al. Mitotic checkpoints and chromosome instability are strong predictors of clinical outcome in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):826-838.

25. Skubitz KM, Geschwind K, Xu WW, Koopmeiners JS, Skubitz AP. Gene expression identifies heterogeneity of metastatic behavior among gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Transl Med. 2016;14:51.

26. Yamaguchi U, Nakayama R, Honda K, et al. Distinct gene expression-defined classes of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4100-4108.

27. Ylipaa A, Hunt KK, Yang J, et al. Integrative genomic characterization and a genomic staging system for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer. 2011;117(2):380-389.

28. Kawanowa K, Sakuma Y, Sakurai S, et al. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(12):1527-1535.

1. Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):865-878.

2. Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(5350):577-580.

3. Corless CL, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Pathologic and molecular features correlate with long-term outcome after adjuvant therapy of resected primary GI stromal tumor: the ACOSOG Z9001 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1563-1570.

4. Huang J, Zheng DL, Qin FS, et al. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of SCARA5 may contribute to human hepatocellular carcinoma by activating FAK signaling. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(1):223-241.

5. Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimaki J, et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):265-274.

6. Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(10):1466-1478.

7. Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(1):52-68.

8. Patel S. Navigating risk stratification systems for the management of patients with GIST. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1698-1704.

9. Rossi S, Miceli R, Messerini L, et al. Natural history of imatinib-naive GISTs: a retrospective analysis of 929 cases with long-term follow-up and development of a survival nomogram based on mitotic index and size as continuous variables. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(11):1646-1656.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Sarcoma. https://www.nccn.org. Accessed March 27, 2018.

11. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10(2):81-89.

12. Huang HY, Li CF, Huang WW, et al. A modification of NIH consensus criteria to better distinguish the highly lethal subset of primary localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a subdivision of the original high-risk group on the basis of outcome. Surgery. 2007;141(6):748-756.

13. Kim MC, Yook JH, Yang HK, et al. Long-term surgical outcome of 1057 gastric GISTs according to 7th UICC/AJCC TNM system: multicenter observational study From Korea and Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(41):e1526.

14. Casali PG, Blay JY; ESMO/CONTICANET/EUROBONET Consensus Panel of experts. Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v198-v203.

15. Joensuu H, DeMatteo RP. The management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a model for targeted and multidisciplinary therapy of malignancy. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:247-258.

16. Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1097-1104.

17. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, et al. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(12):1265-1272.

18. Joensuu H, Rutkowski P, Nishida T, et al. KIT and PDGFRA mutations and the risk of GI stromal tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):634-642.

19. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):459-465.

20. Antonescu CR, Viale A, Sarran L, et al. Gene expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumors is distinguished by KIT genotype and anatomic site. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3282-3290.

21. Arne G, Kristiansson E, Nerman O, et al. Expression profiling of GIST: CD133 is associated with KIT exon 11 mutations, gastric location and poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(5):1149-1161.

22. Bertucci F, Finetti P, Ostrowski J, et al. Genomic Grade Index predicts postoperative clinical outcome of GIST. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(8):1433-1441.

23. Koon N, Schneider-Stock R, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Molecular targets for tumour progression in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Gut. 2004;53(2):235-240.

24. Lagarde P, Perot G, Kauffmann A, et al. Mitotic checkpoints and chromosome instability are strong predictors of clinical outcome in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):826-838.

25. Skubitz KM, Geschwind K, Xu WW, Koopmeiners JS, Skubitz AP. Gene expression identifies heterogeneity of metastatic behavior among gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Transl Med. 2016;14:51.

26. Yamaguchi U, Nakayama R, Honda K, et al. Distinct gene expression-defined classes of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4100-4108.

27. Ylipaa A, Hunt KK, Yang J, et al. Integrative genomic characterization and a genomic staging system for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer. 2011;117(2):380-389.

28. Kawanowa K, Sakuma Y, Sakurai S, et al. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(12):1527-1535.

Striking rash in a patient with lung cancer on a checkpoint inhibitor

Lung cancer remains the most common cause of cancer death in the United States and worldwide.1 Despite advances in the treatment of the disease and development of targeted therapy, the 5-year overall survival in stage IV non–small-cell lung cancer remains poor, ranging from 6% to 10%.2 More recently, checkpoint inhibitors have had a major impact on the treatment of lung cancer. Nivolumab was the first program cell death protein-1 (PD-1) inhibitor approved for malignant melanoma.3 In July 2015, it was approved as a second-line treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung.4 Since then, the use of nivolumab has extended to other malignancies such as head and neck cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and the list continues to expand. In lung cancer, it demonstrated superior overall survival of 9 months, compared with 6 months with docetaxel.4 Other checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab5 and atezolizumab6 were subsequently developed, and are also used in the treatment of lung cancer.

Serious potential autoimmune complications arise in up to 30% of patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors. Dermatologic toxicity is the most common immune-related adverse event in these patients. In addition to vitiligo, most common is a reticular maculopapular rash on the trunk and extremities. Other adverse events, such as photosensitivity, alopecia, xerosis, and hair color changes, are reported less frequently.7 We report here a case of rash at an unusual location (auricular and periauricular) with skin exfoliation mimicking other common skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis.

Case presentation and summary

A 57-year-old woman with a history of cerebrovascular accident with residual left lower-leg paresis presented for acute onset expressive aphasia in the absence of other constitutional or neurological findings. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed a posterior, left parietal lobe lesion of 1.6 cm with intralesional hemorrhage and surrounding edema suggestive of brain metastasis. The patient had a 35 pack-year history of smoking. A staging work-up with computed-tomographic (CT) scans showed a spiculated enhancing nodule in the superior segment of the right lower lobe plus mediastinal adenopathy.

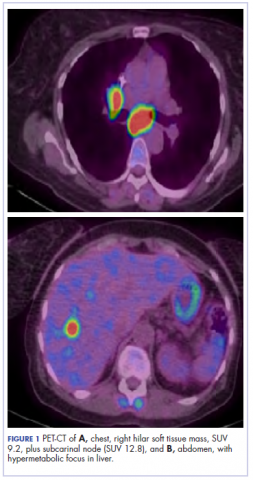

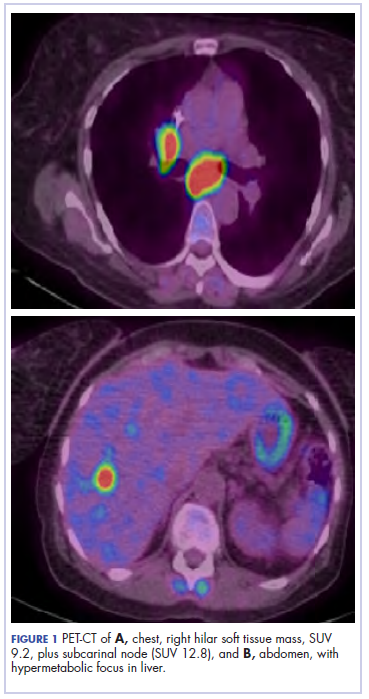

The patient underwent a CT-guided core biopsy of the spiculated nodule, which was found to be consistent with adenocarcinoma of the lung. It was negative for EGFR mutation or ALK rearrangement. She received stereotactic radiosurgery to the left posterior parietal lesion, and after completion of radiation, was started on systemic chemotherapy with cisplatin plus pemetrexed for adenocarcinoma of the lung. She received 4 cycles of chemotherapy. Repeat imaging with a PET-CT showed interval increase of the mediastinal hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy with new hypermetabolic pretracheal lymph nodes and interval development of multiple liver metastases in the right and left lobes of the liver (Figure 1). She was started on second-line therapy with nivolumab at a dose of 240 mg every 2 weeks. The treatment was complicated initially by new onset grade 2 papular pruritic rash after cycle 2 of therapy. The rash involved the upper and lower extremities, sparing the palms, soles, trunk, abdomen, and the back. It resolved with treatment delay and topical steroids.

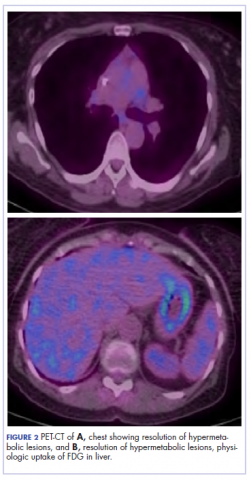

The patient resumed treatment with nivolumab after complete resolution of the rash. However, she developed grade 2 nephritis after cycle 5 with a creatinine level of 1.98 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6-1.2 mg/ dL). This was resolved after treatment with oral prednisone, at a starting dose of 1 mg/kg and tapered over 4 weeks. PET CT scans obtained after cycles 5 and 11 showed no metabolic activity in the mediastinum or the liver and markedly decreased uptake in the right lower lobe nodule, down to an SUV of 1.7 with no new nodules. An MRI of the brain was stable (Figure 2).

After cycle 16 of nivolumab, the patient developed a severe eczematous rash with excoriations at the base of both ears involving the periauricular and auricular areas bilaterally (Figure 3).

She completed 4 weeks of steroid therapy on a tapering schedule. Treatment with nivolumab was resumed afterward with no adverse autoimmune complications. At her last visit (25 months after initiating a PD-1 inhibitor), there was no clinical or radiologic evidence of lung cancer nor any of autoimmune adverse effects.

Discussion

Among multiple autoimmune complications, dermatologic toxicity is the most common immune-related adverse event, occuring in about 30% to 40% of patients7,8 and with an average onset of 3-4 weeks after initiating treatment with checkpoint inhibitors.9 In addition to vitiligo, the most common type of rash described is a reticular maculopapular rash on the trunk and extremities.10 Other findings, such as photosensitivity, alopecia, xerosis, and hair color changes, have been reported in smaller numbers. Skin exfoliation, as seen in the present case, has been reported in fewer than 1% of the cases.4 Perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates extending deep into the dermis are most likely to be seen if the lesions are biopsied. Both the location of the rash in our patient and its relapsing nature are rare and make it more interesting as it presents a diagnostic dilemma for treating physicians. Ear, nose, and throat surgeons are more likely to encounter such a complication with the expanded use of PD-1 and PD-ligand 1 inhibitors in advanced head and neck cancers. The differential diagnosis includes localized eczema, psoriatic rash, skin infection, or an autoimmune phenomenon.

The location of the rash was also of concern because there have been reports of autoimmune inner-ear disease related to immunotherapy.11 After the failure of treatment with empiric antibiotics and topical steroids, in addition to the development of a new rash on her abdomen, we concluded that this case might represent an unusual autoimmune skin complication. The resolution of the skin lesions in both locations (the ears and the abdomen) with the oral steroid therapy, supported our suspected diagnosis of autoimmune dermatitis.

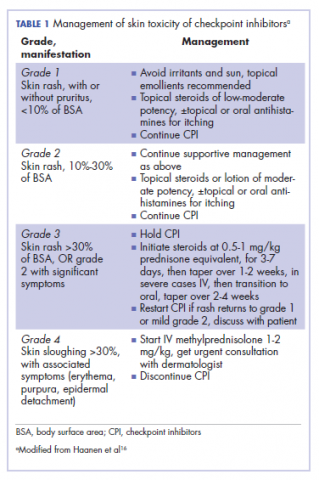

It is essential that these complications are detected early and misdiagnosis is avoided because timely treatment with steroids will prevent progression to more severe problems such as Steven-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis,12 or extension into the inner ear.11This case is part of a growing spectrum of other unusual cases seen with immunotherapy treatment, such as erythema nodosum-like reactions,13 bullous dermatitis,14 and psoriasiform eruptions.15 It highlights the need for an awareness of expanding dermatologic complications from immunotherapy beyond the reported common manifestations. Established guidelines and algorithms for the management of immune-related dermatologic toxicity are available to assist the physician in treatment (Table 1).16 Skin biopsy should be considered if the diagnosis remains uncertain, although starting empiric treatment with steroids is a widely acceptable approach. Reassessing the skin rash in 48 hours to 1 week after treatment initiation is crucial because steroid-refractory cases will need additional immunosuppression. Early termination of steroids is associated with higher recurrence rate, therefore tapering steroids over 4 weeks is highly recommended before resuming treatment with checkpoint inhibitors.

In summary, increased awareness among health care professionals of the common and unusual complications of immunotherapy agents is important and essential in patient care. In addition to oncologists, head and neck surgeons, pulmonologists, urologists, dermatologists, and general internists will encounter patients with immunotherapy-related complications. Patient education should be emphasized to ensure prompt investigation and treatment of complications. Finally, it is not yet clear whether the development of autoimmune reactions predicts disease response to treatment. In a series of 134 patients with lung cancer, the occurrence of autoimmune adverse events correlated with improved survival.17 More research is needed to identify prognostic and predictive biomarkers for response to immunotherapy.

Conclusion

This pattern of autoimmune dermatitis localizing to the ears is rare (<1% of cases of dermatitis). Nevertheless, it raises the awareness for dermatologic complications of immunotherapy beyond the classical reported manifestations. Prompt diagnosis and treatment is essential to avoid serious complications such as Steven-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and potentially damage to the inner ear.

1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87-108.

2. Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (Eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:39-51.

3. Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320-330.

4. Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123-135.

5. Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemo-therapy for PD- L1- positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823- 1833.

6. Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:255-265.

7. Collins LK, Chapman MS, Carter JB, Samie FH. Cutaneous adverse events of the immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Prob Cancer. 2017;41:125-128.

8. Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(12):2375.

9. Weber JS, Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2691-2697.

10. Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25.

11. Zibelman M, Pollak N, Olszanski AJ. Autoimmune inner ear disease in a melanoma patient treated with pembrolizumab. J Immunother Cancer. 2016;4:8.

12. Nayar N, Briscoe K, Penas PF. Toxic epidermal necrolysis-like reaction with severe satellite cell necrosis associated with nivolumab in a patient with ipilimumab refractory metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2016;39(3):149-152.

13. Tetzlaff MT, Jazaeri AA, Torres-Cabala CA, et al. Erythema nodosum-like panniculitis mimicking disease recurrence: a novel toxicity from immune checkpoint blockade therapy - report of 2 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44(12):1080-1086.

14. Naidoo J, Schindler K, Querfeld C, et al. Autoimmune bullous skin disorders with immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 and PD-L1. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(5):383-389.

15. Ohtsuka M, Miura T, Mori T, Ishikawa M, Yamamoto T. Occurrence of psoriasiform eruption during nivolumab therapy for primary oral mucosal melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(7):797-799.

16. Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl 4):iv119-iv142.

17. Haratani K, Hayashi H, Chiba Y, et al. Association of immune-related adverse events with nivolumab efficacy in non-small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):374-378.

Lung cancer remains the most common cause of cancer death in the United States and worldwide.1 Despite advances in the treatment of the disease and development of targeted therapy, the 5-year overall survival in stage IV non–small-cell lung cancer remains poor, ranging from 6% to 10%.2 More recently, checkpoint inhibitors have had a major impact on the treatment of lung cancer. Nivolumab was the first program cell death protein-1 (PD-1) inhibitor approved for malignant melanoma.3 In July 2015, it was approved as a second-line treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung.4 Since then, the use of nivolumab has extended to other malignancies such as head and neck cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and the list continues to expand. In lung cancer, it demonstrated superior overall survival of 9 months, compared with 6 months with docetaxel.4 Other checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab5 and atezolizumab6 were subsequently developed, and are also used in the treatment of lung cancer.

Serious potential autoimmune complications arise in up to 30% of patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors. Dermatologic toxicity is the most common immune-related adverse event in these patients. In addition to vitiligo, most common is a reticular maculopapular rash on the trunk and extremities. Other adverse events, such as photosensitivity, alopecia, xerosis, and hair color changes, are reported less frequently.7 We report here a case of rash at an unusual location (auricular and periauricular) with skin exfoliation mimicking other common skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis.

Case presentation and summary

A 57-year-old woman with a history of cerebrovascular accident with residual left lower-leg paresis presented for acute onset expressive aphasia in the absence of other constitutional or neurological findings. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed a posterior, left parietal lobe lesion of 1.6 cm with intralesional hemorrhage and surrounding edema suggestive of brain metastasis. The patient had a 35 pack-year history of smoking. A staging work-up with computed-tomographic (CT) scans showed a spiculated enhancing nodule in the superior segment of the right lower lobe plus mediastinal adenopathy.

The patient underwent a CT-guided core biopsy of the spiculated nodule, which was found to be consistent with adenocarcinoma of the lung. It was negative for EGFR mutation or ALK rearrangement. She received stereotactic radiosurgery to the left posterior parietal lesion, and after completion of radiation, was started on systemic chemotherapy with cisplatin plus pemetrexed for adenocarcinoma of the lung. She received 4 cycles of chemotherapy. Repeat imaging with a PET-CT showed interval increase of the mediastinal hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy with new hypermetabolic pretracheal lymph nodes and interval development of multiple liver metastases in the right and left lobes of the liver (Figure 1). She was started on second-line therapy with nivolumab at a dose of 240 mg every 2 weeks. The treatment was complicated initially by new onset grade 2 papular pruritic rash after cycle 2 of therapy. The rash involved the upper and lower extremities, sparing the palms, soles, trunk, abdomen, and the back. It resolved with treatment delay and topical steroids.

The patient resumed treatment with nivolumab after complete resolution of the rash. However, she developed grade 2 nephritis after cycle 5 with a creatinine level of 1.98 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6-1.2 mg/ dL). This was resolved after treatment with oral prednisone, at a starting dose of 1 mg/kg and tapered over 4 weeks. PET CT scans obtained after cycles 5 and 11 showed no metabolic activity in the mediastinum or the liver and markedly decreased uptake in the right lower lobe nodule, down to an SUV of 1.7 with no new nodules. An MRI of the brain was stable (Figure 2).

After cycle 16 of nivolumab, the patient developed a severe eczematous rash with excoriations at the base of both ears involving the periauricular and auricular areas bilaterally (Figure 3).

She completed 4 weeks of steroid therapy on a tapering schedule. Treatment with nivolumab was resumed afterward with no adverse autoimmune complications. At her last visit (25 months after initiating a PD-1 inhibitor), there was no clinical or radiologic evidence of lung cancer nor any of autoimmune adverse effects.

Discussion

Among multiple autoimmune complications, dermatologic toxicity is the most common immune-related adverse event, occuring in about 30% to 40% of patients7,8 and with an average onset of 3-4 weeks after initiating treatment with checkpoint inhibitors.9 In addition to vitiligo, the most common type of rash described is a reticular maculopapular rash on the trunk and extremities.10 Other findings, such as photosensitivity, alopecia, xerosis, and hair color changes, have been reported in smaller numbers. Skin exfoliation, as seen in the present case, has been reported in fewer than 1% of the cases.4 Perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates extending deep into the dermis are most likely to be seen if the lesions are biopsied. Both the location of the rash in our patient and its relapsing nature are rare and make it more interesting as it presents a diagnostic dilemma for treating physicians. Ear, nose, and throat surgeons are more likely to encounter such a complication with the expanded use of PD-1 and PD-ligand 1 inhibitors in advanced head and neck cancers. The differential diagnosis includes localized eczema, psoriatic rash, skin infection, or an autoimmune phenomenon.

The location of the rash was also of concern because there have been reports of autoimmune inner-ear disease related to immunotherapy.11 After the failure of treatment with empiric antibiotics and topical steroids, in addition to the development of a new rash on her abdomen, we concluded that this case might represent an unusual autoimmune skin complication. The resolution of the skin lesions in both locations (the ears and the abdomen) with the oral steroid therapy, supported our suspected diagnosis of autoimmune dermatitis.

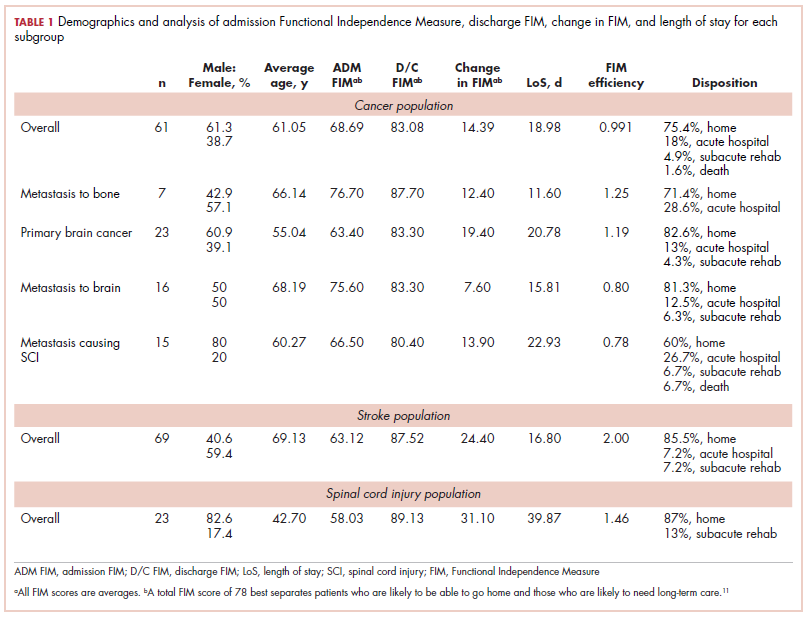

It is essential that these complications are detected early and misdiagnosis is avoided because timely treatment with steroids will prevent progression to more severe problems such as Steven-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis,12 or extension into the inner ear.11This case is part of a growing spectrum of other unusual cases seen with immunotherapy treatment, such as erythema nodosum-like reactions,13 bullous dermatitis,14 and psoriasiform eruptions.15 It highlights the need for an awareness of expanding dermatologic complications from immunotherapy beyond the reported common manifestations. Established guidelines and algorithms for the management of immune-related dermatologic toxicity are available to assist the physician in treatment (Table 1).16 Skin biopsy should be considered if the diagnosis remains uncertain, although starting empiric treatment with steroids is a widely acceptable approach. Reassessing the skin rash in 48 hours to 1 week after treatment initiation is crucial because steroid-refractory cases will need additional immunosuppression. Early termination of steroids is associated with higher recurrence rate, therefore tapering steroids over 4 weeks is highly recommended before resuming treatment with checkpoint inhibitors.

In summary, increased awareness among health care professionals of the common and unusual complications of immunotherapy agents is important and essential in patient care. In addition to oncologists, head and neck surgeons, pulmonologists, urologists, dermatologists, and general internists will encounter patients with immunotherapy-related complications. Patient education should be emphasized to ensure prompt investigation and treatment of complications. Finally, it is not yet clear whether the development of autoimmune reactions predicts disease response to treatment. In a series of 134 patients with lung cancer, the occurrence of autoimmune adverse events correlated with improved survival.17 More research is needed to identify prognostic and predictive biomarkers for response to immunotherapy.

Conclusion

This pattern of autoimmune dermatitis localizing to the ears is rare (<1% of cases of dermatitis). Nevertheless, it raises the awareness for dermatologic complications of immunotherapy beyond the classical reported manifestations. Prompt diagnosis and treatment is essential to avoid serious complications such as Steven-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and potentially damage to the inner ear.

Lung cancer remains the most common cause of cancer death in the United States and worldwide.1 Despite advances in the treatment of the disease and development of targeted therapy, the 5-year overall survival in stage IV non–small-cell lung cancer remains poor, ranging from 6% to 10%.2 More recently, checkpoint inhibitors have had a major impact on the treatment of lung cancer. Nivolumab was the first program cell death protein-1 (PD-1) inhibitor approved for malignant melanoma.3 In July 2015, it was approved as a second-line treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung.4 Since then, the use of nivolumab has extended to other malignancies such as head and neck cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and the list continues to expand. In lung cancer, it demonstrated superior overall survival of 9 months, compared with 6 months with docetaxel.4 Other checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab5 and atezolizumab6 were subsequently developed, and are also used in the treatment of lung cancer.

Serious potential autoimmune complications arise in up to 30% of patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors. Dermatologic toxicity is the most common immune-related adverse event in these patients. In addition to vitiligo, most common is a reticular maculopapular rash on the trunk and extremities. Other adverse events, such as photosensitivity, alopecia, xerosis, and hair color changes, are reported less frequently.7 We report here a case of rash at an unusual location (auricular and periauricular) with skin exfoliation mimicking other common skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis.

Case presentation and summary

A 57-year-old woman with a history of cerebrovascular accident with residual left lower-leg paresis presented for acute onset expressive aphasia in the absence of other constitutional or neurological findings. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed a posterior, left parietal lobe lesion of 1.6 cm with intralesional hemorrhage and surrounding edema suggestive of brain metastasis. The patient had a 35 pack-year history of smoking. A staging work-up with computed-tomographic (CT) scans showed a spiculated enhancing nodule in the superior segment of the right lower lobe plus mediastinal adenopathy.

The patient underwent a CT-guided core biopsy of the spiculated nodule, which was found to be consistent with adenocarcinoma of the lung. It was negative for EGFR mutation or ALK rearrangement. She received stereotactic radiosurgery to the left posterior parietal lesion, and after completion of radiation, was started on systemic chemotherapy with cisplatin plus pemetrexed for adenocarcinoma of the lung. She received 4 cycles of chemotherapy. Repeat imaging with a PET-CT showed interval increase of the mediastinal hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy with new hypermetabolic pretracheal lymph nodes and interval development of multiple liver metastases in the right and left lobes of the liver (Figure 1). She was started on second-line therapy with nivolumab at a dose of 240 mg every 2 weeks. The treatment was complicated initially by new onset grade 2 papular pruritic rash after cycle 2 of therapy. The rash involved the upper and lower extremities, sparing the palms, soles, trunk, abdomen, and the back. It resolved with treatment delay and topical steroids.

The patient resumed treatment with nivolumab after complete resolution of the rash. However, she developed grade 2 nephritis after cycle 5 with a creatinine level of 1.98 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6-1.2 mg/ dL). This was resolved after treatment with oral prednisone, at a starting dose of 1 mg/kg and tapered over 4 weeks. PET CT scans obtained after cycles 5 and 11 showed no metabolic activity in the mediastinum or the liver and markedly decreased uptake in the right lower lobe nodule, down to an SUV of 1.7 with no new nodules. An MRI of the brain was stable (Figure 2).

After cycle 16 of nivolumab, the patient developed a severe eczematous rash with excoriations at the base of both ears involving the periauricular and auricular areas bilaterally (Figure 3).

She completed 4 weeks of steroid therapy on a tapering schedule. Treatment with nivolumab was resumed afterward with no adverse autoimmune complications. At her last visit (25 months after initiating a PD-1 inhibitor), there was no clinical or radiologic evidence of lung cancer nor any of autoimmune adverse effects.

Discussion

Among multiple autoimmune complications, dermatologic toxicity is the most common immune-related adverse event, occuring in about 30% to 40% of patients7,8 and with an average onset of 3-4 weeks after initiating treatment with checkpoint inhibitors.9 In addition to vitiligo, the most common type of rash described is a reticular maculopapular rash on the trunk and extremities.10 Other findings, such as photosensitivity, alopecia, xerosis, and hair color changes, have been reported in smaller numbers. Skin exfoliation, as seen in the present case, has been reported in fewer than 1% of the cases.4 Perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates extending deep into the dermis are most likely to be seen if the lesions are biopsied. Both the location of the rash in our patient and its relapsing nature are rare and make it more interesting as it presents a diagnostic dilemma for treating physicians. Ear, nose, and throat surgeons are more likely to encounter such a complication with the expanded use of PD-1 and PD-ligand 1 inhibitors in advanced head and neck cancers. The differential diagnosis includes localized eczema, psoriatic rash, skin infection, or an autoimmune phenomenon.

The location of the rash was also of concern because there have been reports of autoimmune inner-ear disease related to immunotherapy.11 After the failure of treatment with empiric antibiotics and topical steroids, in addition to the development of a new rash on her abdomen, we concluded that this case might represent an unusual autoimmune skin complication. The resolution of the skin lesions in both locations (the ears and the abdomen) with the oral steroid therapy, supported our suspected diagnosis of autoimmune dermatitis.

It is essential that these complications are detected early and misdiagnosis is avoided because timely treatment with steroids will prevent progression to more severe problems such as Steven-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis,12 or extension into the inner ear.11This case is part of a growing spectrum of other unusual cases seen with immunotherapy treatment, such as erythema nodosum-like reactions,13 bullous dermatitis,14 and psoriasiform eruptions.15 It highlights the need for an awareness of expanding dermatologic complications from immunotherapy beyond the reported common manifestations. Established guidelines and algorithms for the management of immune-related dermatologic toxicity are available to assist the physician in treatment (Table 1).16 Skin biopsy should be considered if the diagnosis remains uncertain, although starting empiric treatment with steroids is a widely acceptable approach. Reassessing the skin rash in 48 hours to 1 week after treatment initiation is crucial because steroid-refractory cases will need additional immunosuppression. Early termination of steroids is associated with higher recurrence rate, therefore tapering steroids over 4 weeks is highly recommended before resuming treatment with checkpoint inhibitors.

In summary, increased awareness among health care professionals of the common and unusual complications of immunotherapy agents is important and essential in patient care. In addition to oncologists, head and neck surgeons, pulmonologists, urologists, dermatologists, and general internists will encounter patients with immunotherapy-related complications. Patient education should be emphasized to ensure prompt investigation and treatment of complications. Finally, it is not yet clear whether the development of autoimmune reactions predicts disease response to treatment. In a series of 134 patients with lung cancer, the occurrence of autoimmune adverse events correlated with improved survival.17 More research is needed to identify prognostic and predictive biomarkers for response to immunotherapy.

Conclusion

This pattern of autoimmune dermatitis localizing to the ears is rare (<1% of cases of dermatitis). Nevertheless, it raises the awareness for dermatologic complications of immunotherapy beyond the classical reported manifestations. Prompt diagnosis and treatment is essential to avoid serious complications such as Steven-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and potentially damage to the inner ear.

1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87-108.

2. Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (Eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:39-51.

3. Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320-330.

4. Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123-135.

5. Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemo-therapy for PD- L1- positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823- 1833.

6. Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:255-265.

7. Collins LK, Chapman MS, Carter JB, Samie FH. Cutaneous adverse events of the immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Prob Cancer. 2017;41:125-128.

8. Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(12):2375.

9. Weber JS, Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2691-2697.

10. Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25.

11. Zibelman M, Pollak N, Olszanski AJ. Autoimmune inner ear disease in a melanoma patient treated with pembrolizumab. J Immunother Cancer. 2016;4:8.

12. Nayar N, Briscoe K, Penas PF. Toxic epidermal necrolysis-like reaction with severe satellite cell necrosis associated with nivolumab in a patient with ipilimumab refractory metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2016;39(3):149-152.

13. Tetzlaff MT, Jazaeri AA, Torres-Cabala CA, et al. Erythema nodosum-like panniculitis mimicking disease recurrence: a novel toxicity from immune checkpoint blockade therapy - report of 2 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44(12):1080-1086.

14. Naidoo J, Schindler K, Querfeld C, et al. Autoimmune bullous skin disorders with immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 and PD-L1. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(5):383-389.

15. Ohtsuka M, Miura T, Mori T, Ishikawa M, Yamamoto T. Occurrence of psoriasiform eruption during nivolumab therapy for primary oral mucosal melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(7):797-799.

16. Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl 4):iv119-iv142.

17. Haratani K, Hayashi H, Chiba Y, et al. Association of immune-related adverse events with nivolumab efficacy in non-small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):374-378.

1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87-108.

2. Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (Eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:39-51.

3. Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320-330.

4. Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123-135.

5. Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemo-therapy for PD- L1- positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823- 1833.

6. Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:255-265.

7. Collins LK, Chapman MS, Carter JB, Samie FH. Cutaneous adverse events of the immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Prob Cancer. 2017;41:125-128.

8. Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(12):2375.

9. Weber JS, Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2691-2697.

10. Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25.

11. Zibelman M, Pollak N, Olszanski AJ. Autoimmune inner ear disease in a melanoma patient treated with pembrolizumab. J Immunother Cancer. 2016;4:8.

12. Nayar N, Briscoe K, Penas PF. Toxic epidermal necrolysis-like reaction with severe satellite cell necrosis associated with nivolumab in a patient with ipilimumab refractory metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2016;39(3):149-152.

13. Tetzlaff MT, Jazaeri AA, Torres-Cabala CA, et al. Erythema nodosum-like panniculitis mimicking disease recurrence: a novel toxicity from immune checkpoint blockade therapy - report of 2 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44(12):1080-1086.

14. Naidoo J, Schindler K, Querfeld C, et al. Autoimmune bullous skin disorders with immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 and PD-L1. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(5):383-389.

15. Ohtsuka M, Miura T, Mori T, Ishikawa M, Yamamoto T. Occurrence of psoriasiform eruption during nivolumab therapy for primary oral mucosal melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(7):797-799.

16. Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl 4):iv119-iv142.

17. Haratani K, Hayashi H, Chiba Y, et al. Association of immune-related adverse events with nivolumab efficacy in non-small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):374-378.

Effective management of severe radiation dermatitis after head and neck radiotherapy

Head and neck cancer is among the most prevalent cancers in developing countries.1 Most of the patients in developing countries present in locally advanced stages, and radical radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy is the standard treatment.1 Radiation therapy is associated with radiation dermatitis, which causes severe symptoms in the patient and can lead to disruption of treatment, diminished rates of disease control rates, and impaired patient quality of life.2 The management of advanced radiation dermatitis is difficult and can cause consequential late morbidity to patients.2 We report here the rare case of a patient with locally advanced tonsil carcinoma who developed grade 3 radiation dermatitis while receiving radical chemoradiation. The patient’s radiation dermatitis was effectively managed with the use of a silver-containing antimicrobial dressing that yielded remarkable results, so the patient was able to resume and complete radiation therapy.

Case presentation and summary

A 48-year-old man was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the right tonsil, with bilateral neck nodes (Stage T4a N2c M0; The American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual, 7th edition). In view of the locally advanced status of his disease, the patient was scheduled for radical radiation therapy at 70 Gy in 35 fractions over 7 weeks along with weekly chemotherapy (cisplatin 40 mg/m2). During the course of radiation therapy, the patient was monitored twice a week, and symptomatic care was done for radiation-therapy–induced toxicities.

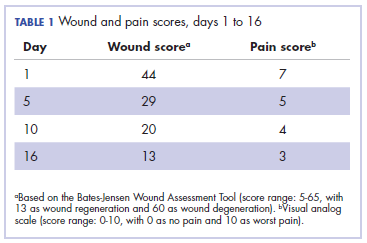

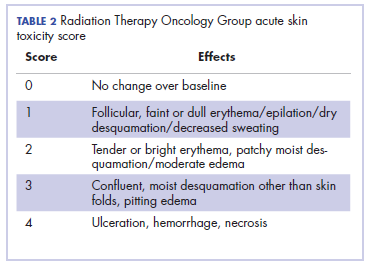

The patient presented with grade 3 radiation dermatitis after receiving 58 Gy in 29 fractions over 5 weeks (grade 0, no change; grades 3 and 4, severe change). The radiation dermatitis involved the anterior and bilateral neck with moist desquamation of the skin (Figure 1).

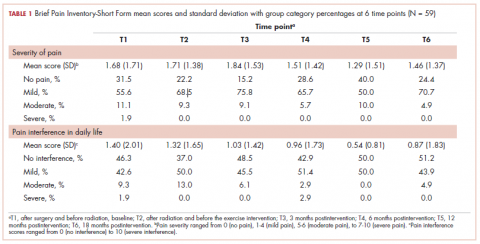

It was associated with severe pain, difficulty in swallowing, and oral mucositis. The patient was subsequently admitted to the hospital; radiation therapy was stopped, and treatment was initiated to ease the effects of the radiation dermatitis. Analgesics were administered for the pain, and adequate hydration and nutritional support was administered through a nasogastric tube. The patient’s score on the Bates-Jensen Wound Assessment Tool (BWAT) for monitoring wound status was 44, which falls in extreme severity status.

In view of the extreme severity status of the radiation dermatitis, after cleaning the wound with sterile water, we covered it with an antimicrobial dressing that contained silver salt (Mepilex AG; Mölnlycke Health Care, Norcross, GA). The dressing was changed regularly every 4 days. There was a gradual improvement in the radiation dermatitis (Figure 2).

Discussion

Head and neck cancer is one of the most common cancers in developing countries.1 Most patients present with locally advanced disease, so chemoradiation is the standard treatment in these patents. Radiation therapy is associated with acute and chronic toxicities. The common radiation therapy toxicities are directed at skin and mucosa, which leads to radiation dermatitis and radiation mucositis, respectively.2 These toxicities are graded as per the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) criteria (Table 2).3

Acute radiation dermatitis is radiation therapy dose-dependent and manifests within a few days to weeks after starting external beam radiation therapy. Its presentation varies in severity and gradually manifests as erythema, dry or moist desquamation, and ulceration when severe. These can cause severe symptoms in the patient, leading to frequent breaks in treatment, decreased rates of disease control, and impaired patient quality of life.2 Apart from RTOG grading, radiation dermatitis can also be scored using the BWAT. This tool has been validated across many studies to score initial wound status and monitor the subsequent status numerically.4 The radiation dermatitis of the index case was scored and monitored with both RTOG and BWAT scores.The management of advanced radiation dermatitis is difficult, and it causes consequential late morbidity in patients. A range of topical agents and dressings are used to treat radiation dermatitis, but there is minimal evidence to support their use.5 The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer treatment guidelines for prevention and treatment of radiation dermatitis have also concluded that there is a lack of sufficient evidence in the literature to support the superiority for any specific intervention.6 Management of radiation dermatitis varies among practitioners because of the inconclusive evidence for available treatment options.

The use of silver-based antimicrobial dressings has been reported in the literature in the prevention and treatment of radiation dermatitis, but with mixed results.7 Such dressings absorb exudate, maintain a moist environment that promotes wound healing, fight infection, and minimize the risk for maceration, according to the product information sheet.8 Clinical study findings have shown silver to be effective in fighting many different types of pathogens, including Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other drug-resistant bacteria.

Aquino-Parsons and colleagues studied 196 patients with breast cancer who were undergoing whole-breast radiation therapy.9 They showed that there was no benefit of silver-containing foam dressings for the prevention of acute grade 3 radiation dermatitis compared with patients who received standard skin care (with moisturizing cream, topical steroids, saline compress, and silver sulfadiazine cream). However, the incidence of itching in the last week of radiation and 1 week after treatment completion was lower among the patients who used the dressings.

Diggelmann and colleagues studied 24 patients with breast cancer who were undergoing radiation therapy.10 Each of the erythematous areas (n = 34) was randomly divided into 2 groups; 1 group was treated with Mepilex Lite dressing and the other with standard aqueous cream. There was a significant reduction in the severity of acute radiation dermatitis in the areas on which Mepilex Lite dressings were used compared with the areas on which standard aqueous cream was used.

The patient in the present case had severe grade 3 acute radiation dermatitis with a BWAT score indicative of extreme severity. After cleaning the wound with sterile water, instead of using the standard aqueous cream on the wounds, we used Mepilex AG, an antimicrobial dressing that contains silver salt. The results were remarkable (Figure 2 and Table 2). The patient was able to restart radiation therapy, and he completed his scheduled doses.

This case highlights the effectiveness of a silver-based antimicrobial dressing in the management of advanced and severe radiation dermatitis. Further large and randomized studies are needed to test the routine use of the dressing in the management of radiation dermatitis.

1. Simard EP, Torre LA, Jemal A. International trends in head and neck cancer incidence rates: differences by country, sex and anatomic site. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(5):387-403.

2. Hymes SR, Strom EA, Fife C. Radiation dermatitis: clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and treatment 2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(1):28-46.

3. Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(5):1341-1346.

4. Harris C, Bates-Jensen B, Parslow N, Raizman R, Singh M, Ketchen R. Bates‐Jensen wound assessment tool: pictorial guide validation project. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010;37(3):253-259.

5. Lucey P, Zouzias C, Franco L, Chennupati SK, Kalnicki S, McLellan BN. Practice patterns for the prophylaxis and treatment of acute radiation dermatitis in the United States. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(9):2857-2862.

6. Wong RK, Bensadoun RJ, Boers-Doets CB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of acute and late radiation reactions from the MASCC Skin Toxicity Study Group. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(10):2933-2948.

7. Vavassis P, Gelinas M, Chabot Tr J, Nguyen-Tân PF. Phase 2 study of silver leaf dressing for treatment of radiation-induced dermatitis in patients receiving radiotherapy to the head and neck. J Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 2008;37(1):124-129.

8. Mepilex Ag product information. Mölnlycke Health Care website. http://www.molnlycke.us/advanced-wound-care-products/antimicrobial-products/mepilex-ag/#confirm. Accessed May 3, 2018.