User login

Should metformin be used in every patient with type 2 diabetes?

Most patients should receive it, with exceptions as noted below. Metformin is the cornerstone of diabetes therapy and should be considered in all patients with type 2 diabetes. Both the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE)1,2 recommend it as first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes. It lowers blood glucose levels by inhibiting hepatic glucose production, and it does not tend to cause hypoglycemia.

However, metformin is underused. A 2012 study showed that only 50% to 70% of patients with type 2 diabetes treated with a sulfonylurea, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, thiazolidinedione, or glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue also received metformin.3 This occurred despite guidelines recommending continuing metformin when starting other diabetes drugs.4

EVIDENCE METFORMIN IS EFFECTIVE

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)5 found that metformin significantly reduced the incidence of:

- Any diabetes-related end point (hazard ratio [HR] 0.68, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.53–0.87)

- Myocardial infarction (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.41–0.89)

- Diabetes-related death (HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.37–0.91)

- All-cause mortality (HR 0.64; 95% CI 0.45–0.91).

The Hyperinsulinemia: Outcomes of Its Metabolic Effects (HOME) trial,6 a multicenter trial conducted in the Netherlands, evaluated the effect of adding metformin (vs placebo) to existing insulin regimens. Metformin recipients had a significantly lower rate of macrovascular mortality (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.40–0.94, P = .02), but not of the primary end point, an aggregate of microvascular and macrovascular morbidity and mortality.

The Study on the Prognosis and Effect of Antidiabetic Drugs on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus With Coronary Artery Disease trial,7 a multicenter trial conducted in China, compared the effects of metformin vs glipizide on cardiovascular outcomes. At about 3 years of treatment, the metformin group had a significantly lower rate of the composite primary end point of recurrent cardiovascular events (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.30–0.90). This end point included nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, arterial revascularization by percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty or by coronary artery bypass graft, death from a cardiovascular cause, and death from any cause.

These studies prompted the ADA to emphasize that metformin can reduce the risk of cardiovascular events or death. Metformin also has been shown to be weight-neutral or to induce slight weight loss. Furthermore, it is inexpensive.

WHAT ABOUT THE RENAL EFFECTS?

Because metformin is renally cleared, it has caused some concern about nephrotoxicity, especially lactic acidosis, in patients with impaired renal function. But the most recent guidelines have relaxed the criteria for metformin use in this patient population.

Revised labeling

Metformin’s labeling,8 revised in 2016, states the following:

- If the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, metformin is contraindicated

- If the eGFR is between 30 and 45 mL/min/1.73 m2, metformin is not recommended

- If the eGFR is below 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 in a patient taking metformin, the risks and benefits of continuing treatment should be assessed, the dosage may need to be adjusted, and renal function should be monitored more frequently.8

These labeling revisions were based on a systematic review by Inzucchi et al9 that found metformin is not associated with increased rates of lactic acidosis in patients with mild to moderate kidney disease. Subsequently, an observational study published in 2018 by Lazarus et al10 showed that metformin increases the risk of acidosis only at eGFR levels below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Also, a Cochrane review published in 2003 did not find a single case of lactic acidosis in 347 trials with 70,490 patient-years of metformin treatment.11

Previous guidelines used serum creatinine levels, with metformin contraindicated at levels of 1.5 mg/dL or above for men and 1.4 mg/dL for women, or with abnormal creatinine clearance. The ADA and the AACE now use the eGFR1,2 instead of the serum creatinine level to measure kidney function because it better accounts for factors such as the patient’s age, sex, race, and weight.

Despite the evidence, the common patient perception is that metformin is nephrotoxic, and it is important for practitioners to dispel this myth during clinic visits.

What about metformin use with contrast agents?

Labeling has a precautionary note stating that metformin should be held at the time of, or prior to, any imaging procedure involving iodinated contrast agents in patients with an eGFR between 30 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2; in patients with a history of hepatic impairment, alcoholism, or heart failure; or in patients who will receive intra-arterial iodinated contrast. The eGFR should be reevaluated 48 hours after the imaging procedure.8

Additionally, if the iodinated contrast agent causes acute kidney injury, metformin could accumulate, with resultant lactate accumulation.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) has proposed less stringent guidelines for metformin during radiocontrast imaging studies. This change is based on evidence that lactic acidosis is rare—about 10 cases per 100,000 patient-years—and that there are no reports of lactic acidosis after intravenously administered iodinated contrast in properly selected patients.12,13

The ACR divides patients taking metformin into 2 categories:

- No evidence of acute kidney injury and eGFR greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2

- Either acute kidney injury or chronic kidney disease with eGFR below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 or undergoing arterial catheter studies with a high chance of embolization to the renal arteries.14

For the first group, they recommend against discontinuing metformin before or after giving iodinated contrast or checking kidney function after the procedure.

For the second group, they recommend holding metformin before and 48 hours after the procedure. It should not be restarted until renal function is confirmed to be normal.

METFORMIN AND INSULIN

The ADA recommends1 continuing metformin after initiating insulin. However, in clinical practice, it is often not done.

Clinical trials have shown that combining metformin with insulin significantly improves glycemic control, prevents weight gain, and decreases insulin requirements.15,16 One trial16 also looked at cardiovascular end points during a 4-year follow-up period; combining metformin with insulin decreased the macrovascular disease-related event rate compared with insulin alone.

In the HOME trial,6 which added metformin to the existing insulin regimen, both groups gained weight, but the metformin group had gained about 3 kg less than the placebo group at the end of the 4.3-year trial. Metformin did not increase the risk of hypoglycemia, but it also did not reduce the risk of microvascular disease.

Concomitant metformin reduces costs

These days, practitioners can choose from a large selection of diabetes drugs. These include insulins with better pharmacokinetic profiles, as well as newer classes of noninsulin agents such as sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues.

Metformin is less expensive than these newer drugs, and using it concomitantly with other diabetes drugs can decrease their dosage requirements, which in turn decreases their monthly costs.

GASTROINTESTINAL EFFECTS

Metformin’s gastrointestinal adverse effects such as diarrhea, flatulence, nausea, and vomiting are a barrier to its use. The actual incidence rate of diarrhea varies widely in randomized trials and observational studies, and gastrointestinal effects are worse in metformin-naive patients, as well as those who have chronic gastritis or Helicobacter pylori infection.17

We have found that starting metformin at a low dose and up-titrating it over several weeks increases tolerability. We often start patients at 500 mg/day and increase the dosage by 1 500-mg tablet every 1 to 2 weeks. Also, we have noticed that intolerance is more likely in patients who eat a high-carbohydrate diet, but there is no high-level evidence to back this up because patients in clinical trials all undergo nutrition counseling and are therefore more likely to adhere to the low-carbohydrate diet.

Also, the extended-release formulation is more tolerable than the immediate-release formulation and has similar glycemic efficacy. It may be an option as first-line therapy or for patients who have significant adverse effects from immediate-release metformin.18 For patients on the immediate-release formulation, taking it with meals helps lessen some gastrointestinal effects, and this should be emphasized at every visit.

Finally, we limit the metformin dose to 2,000 mg/day, rather than the 2,550 mg/day allowed on labeling. Garber et al19 found that the lower dosage still provides the maximum clinical efficacy.

OTHER CAUTIONS

Metformin should be avoided in patients with acute or unstable heart failure because of the increased risk of lactic acidosis.

It also should be avoided in patients with hepatic impairment, according to the labeling. But this remains controversial in practice. Zhang et al20 showed that continuing metformin in patients with diabetes and cirrhosis decreases the mortality risk by 57% compared with those taken off metformin.

Diet and lifestyle measures need to be emphasized at each visit. Wing et al21 showed that calorie restriction regardless of weight loss is beneficial for glycemic control and insulin sensitivity in obese patients with diabetes.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

Metformin improves glycemic control without tending to cause weight gain or hypoglycemia. It may also have cardiovascular benefits. Metformin is an inexpensive agent that should be continued, if tolerated, in those who need additional agents for glycemic control. It should be considered in all adult patients with type 2 diabetes.

- American Diabetes Association. 8. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care 2018; 41(suppl 1):S73–S85. doi:10.2337/dc18-S008

- Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2018 executive summary. Endocr Pract 2018; 24(1):91–120. doi:10.4158/CS-2017-0153

- Hampp C, Borders-Hemphill V, Moeny DG, Wysowski DK. Use of antidiabetic drugs in the US, 2003–2012. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(5):1367–1374. doi:10.2337/dc13-2289

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012; 35(6):1364–1379. doi:10.2337/dc12-0413

- Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet 1998; 352(9131):854–865. pmid:9742977

- Kooy A, de Jager J, Lehert P, et al. Long-term effects of metformin on metabolism and microvascular and macrovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(6):616–625. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.20

- Hong J, Zhang Y, Lai S, et al; SPREAD-DIMCAD Investigators. Effects of metformin versus glipizide on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. Diabetes Care 2013; 36(5):1304–1311. doi:10.2337/dc12-0719

- Glucophage (metformin hydrochloride) and Glucophage XR (extended-release) [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/020357s034,021202s018lbl.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2018.

- Inzucchi SE, Lipska KJ, Mayo H, Bailey CJ, McGuire DK. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease: a systematic review. JAMA 2014; 312(24):2668–2675. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.15298

- Lazarus B, Wu A, Shin JI, et al. Association of metformin use with risk of lactic acidosis across the range of kidney function: a community-based cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178(7):903–910. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0292

- Salpeter S, Greyber E, Pasternak G, Salpeter E. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; (2):CD002967. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002967

- Eppenga WL, Lalmohamed A, Geerts AF, et al. Risk of lactic acidosis or elevated lactate concentrations in metformin users with renal impairment: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(8):2218–2224. doi:10.2337/dc13-3023

- Richy FF, Sabidó-Espin M, Guedes S, Corvino FA, Gottwald-Hostalek U. Incidence of lactic acidosis in patients with type 2 diabetes with and without renal impairment treated with metformin: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(8):2291–2295. doi:10.2337/dc14-0464

- American College of Radiology (ACR). Manual on Contrast Media. Version 10.3. www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Contrast-Manual. Accessed December 5, 2018.

- Wulffele MG, Kooy A, Lehert P, et al. Combination of insulin and metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002; 25(12):2133–2140. pmid:12453950

- Kooy A, de Jager J, Lehert P, et al. Long-term effects of metformin on metabolism and microvascular and macrovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(6):616–625. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.20

- Bonnet F, Scheen A. Understanding and overcoming metformin gastrointestinal intolerance, Diabetes Obes Metab 2017; 19(4):473–481. doi:10.1111/dom.12854

- Jabbour S, Ziring B. Advantages of extended-release metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Postgrad Med 2011; 123(1):15–23. doi:10.3810/pgm.2011.01.2241

- Garber AJ, Duncan TG, Goodman AM, Mills DJ, Rohlf JL. Efficacy of metformin in type II diabetes: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response trial. Am J Med 1997; 103(6):491–497. pmid:9428832

- Zhang X, Harmsen WS, Mettler TA, et al. Continuation of metformin use after a diagnosis of cirrhosis significantly improves survival of patients with diabetes. Hepatology 2014; 60(6):2008–2016. doi:10.1002/hep.27199

- Wing RR, Blair EH, Bononi P, Marcus MD, Watanabe R, Bergman RN. Caloric restriction per se is a significant factor in improvements in glycemic control and insulin sensitivity during weight loss in obese NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care 1994; 17(1):30–36. pmid:8112186

Most patients should receive it, with exceptions as noted below. Metformin is the cornerstone of diabetes therapy and should be considered in all patients with type 2 diabetes. Both the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE)1,2 recommend it as first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes. It lowers blood glucose levels by inhibiting hepatic glucose production, and it does not tend to cause hypoglycemia.

However, metformin is underused. A 2012 study showed that only 50% to 70% of patients with type 2 diabetes treated with a sulfonylurea, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, thiazolidinedione, or glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue also received metformin.3 This occurred despite guidelines recommending continuing metformin when starting other diabetes drugs.4

EVIDENCE METFORMIN IS EFFECTIVE

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)5 found that metformin significantly reduced the incidence of:

- Any diabetes-related end point (hazard ratio [HR] 0.68, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.53–0.87)

- Myocardial infarction (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.41–0.89)

- Diabetes-related death (HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.37–0.91)

- All-cause mortality (HR 0.64; 95% CI 0.45–0.91).

The Hyperinsulinemia: Outcomes of Its Metabolic Effects (HOME) trial,6 a multicenter trial conducted in the Netherlands, evaluated the effect of adding metformin (vs placebo) to existing insulin regimens. Metformin recipients had a significantly lower rate of macrovascular mortality (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.40–0.94, P = .02), but not of the primary end point, an aggregate of microvascular and macrovascular morbidity and mortality.

The Study on the Prognosis and Effect of Antidiabetic Drugs on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus With Coronary Artery Disease trial,7 a multicenter trial conducted in China, compared the effects of metformin vs glipizide on cardiovascular outcomes. At about 3 years of treatment, the metformin group had a significantly lower rate of the composite primary end point of recurrent cardiovascular events (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.30–0.90). This end point included nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, arterial revascularization by percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty or by coronary artery bypass graft, death from a cardiovascular cause, and death from any cause.

These studies prompted the ADA to emphasize that metformin can reduce the risk of cardiovascular events or death. Metformin also has been shown to be weight-neutral or to induce slight weight loss. Furthermore, it is inexpensive.

WHAT ABOUT THE RENAL EFFECTS?

Because metformin is renally cleared, it has caused some concern about nephrotoxicity, especially lactic acidosis, in patients with impaired renal function. But the most recent guidelines have relaxed the criteria for metformin use in this patient population.

Revised labeling

Metformin’s labeling,8 revised in 2016, states the following:

- If the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, metformin is contraindicated

- If the eGFR is between 30 and 45 mL/min/1.73 m2, metformin is not recommended

- If the eGFR is below 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 in a patient taking metformin, the risks and benefits of continuing treatment should be assessed, the dosage may need to be adjusted, and renal function should be monitored more frequently.8

These labeling revisions were based on a systematic review by Inzucchi et al9 that found metformin is not associated with increased rates of lactic acidosis in patients with mild to moderate kidney disease. Subsequently, an observational study published in 2018 by Lazarus et al10 showed that metformin increases the risk of acidosis only at eGFR levels below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Also, a Cochrane review published in 2003 did not find a single case of lactic acidosis in 347 trials with 70,490 patient-years of metformin treatment.11

Previous guidelines used serum creatinine levels, with metformin contraindicated at levels of 1.5 mg/dL or above for men and 1.4 mg/dL for women, or with abnormal creatinine clearance. The ADA and the AACE now use the eGFR1,2 instead of the serum creatinine level to measure kidney function because it better accounts for factors such as the patient’s age, sex, race, and weight.

Despite the evidence, the common patient perception is that metformin is nephrotoxic, and it is important for practitioners to dispel this myth during clinic visits.

What about metformin use with contrast agents?

Labeling has a precautionary note stating that metformin should be held at the time of, or prior to, any imaging procedure involving iodinated contrast agents in patients with an eGFR between 30 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2; in patients with a history of hepatic impairment, alcoholism, or heart failure; or in patients who will receive intra-arterial iodinated contrast. The eGFR should be reevaluated 48 hours after the imaging procedure.8

Additionally, if the iodinated contrast agent causes acute kidney injury, metformin could accumulate, with resultant lactate accumulation.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) has proposed less stringent guidelines for metformin during radiocontrast imaging studies. This change is based on evidence that lactic acidosis is rare—about 10 cases per 100,000 patient-years—and that there are no reports of lactic acidosis after intravenously administered iodinated contrast in properly selected patients.12,13

The ACR divides patients taking metformin into 2 categories:

- No evidence of acute kidney injury and eGFR greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2

- Either acute kidney injury or chronic kidney disease with eGFR below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 or undergoing arterial catheter studies with a high chance of embolization to the renal arteries.14

For the first group, they recommend against discontinuing metformin before or after giving iodinated contrast or checking kidney function after the procedure.

For the second group, they recommend holding metformin before and 48 hours after the procedure. It should not be restarted until renal function is confirmed to be normal.

METFORMIN AND INSULIN

The ADA recommends1 continuing metformin after initiating insulin. However, in clinical practice, it is often not done.

Clinical trials have shown that combining metformin with insulin significantly improves glycemic control, prevents weight gain, and decreases insulin requirements.15,16 One trial16 also looked at cardiovascular end points during a 4-year follow-up period; combining metformin with insulin decreased the macrovascular disease-related event rate compared with insulin alone.

In the HOME trial,6 which added metformin to the existing insulin regimen, both groups gained weight, but the metformin group had gained about 3 kg less than the placebo group at the end of the 4.3-year trial. Metformin did not increase the risk of hypoglycemia, but it also did not reduce the risk of microvascular disease.

Concomitant metformin reduces costs

These days, practitioners can choose from a large selection of diabetes drugs. These include insulins with better pharmacokinetic profiles, as well as newer classes of noninsulin agents such as sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues.

Metformin is less expensive than these newer drugs, and using it concomitantly with other diabetes drugs can decrease their dosage requirements, which in turn decreases their monthly costs.

GASTROINTESTINAL EFFECTS

Metformin’s gastrointestinal adverse effects such as diarrhea, flatulence, nausea, and vomiting are a barrier to its use. The actual incidence rate of diarrhea varies widely in randomized trials and observational studies, and gastrointestinal effects are worse in metformin-naive patients, as well as those who have chronic gastritis or Helicobacter pylori infection.17

We have found that starting metformin at a low dose and up-titrating it over several weeks increases tolerability. We often start patients at 500 mg/day and increase the dosage by 1 500-mg tablet every 1 to 2 weeks. Also, we have noticed that intolerance is more likely in patients who eat a high-carbohydrate diet, but there is no high-level evidence to back this up because patients in clinical trials all undergo nutrition counseling and are therefore more likely to adhere to the low-carbohydrate diet.

Also, the extended-release formulation is more tolerable than the immediate-release formulation and has similar glycemic efficacy. It may be an option as first-line therapy or for patients who have significant adverse effects from immediate-release metformin.18 For patients on the immediate-release formulation, taking it with meals helps lessen some gastrointestinal effects, and this should be emphasized at every visit.

Finally, we limit the metformin dose to 2,000 mg/day, rather than the 2,550 mg/day allowed on labeling. Garber et al19 found that the lower dosage still provides the maximum clinical efficacy.

OTHER CAUTIONS

Metformin should be avoided in patients with acute or unstable heart failure because of the increased risk of lactic acidosis.

It also should be avoided in patients with hepatic impairment, according to the labeling. But this remains controversial in practice. Zhang et al20 showed that continuing metformin in patients with diabetes and cirrhosis decreases the mortality risk by 57% compared with those taken off metformin.

Diet and lifestyle measures need to be emphasized at each visit. Wing et al21 showed that calorie restriction regardless of weight loss is beneficial for glycemic control and insulin sensitivity in obese patients with diabetes.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

Metformin improves glycemic control without tending to cause weight gain or hypoglycemia. It may also have cardiovascular benefits. Metformin is an inexpensive agent that should be continued, if tolerated, in those who need additional agents for glycemic control. It should be considered in all adult patients with type 2 diabetes.

Most patients should receive it, with exceptions as noted below. Metformin is the cornerstone of diabetes therapy and should be considered in all patients with type 2 diabetes. Both the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE)1,2 recommend it as first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes. It lowers blood glucose levels by inhibiting hepatic glucose production, and it does not tend to cause hypoglycemia.

However, metformin is underused. A 2012 study showed that only 50% to 70% of patients with type 2 diabetes treated with a sulfonylurea, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, thiazolidinedione, or glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue also received metformin.3 This occurred despite guidelines recommending continuing metformin when starting other diabetes drugs.4

EVIDENCE METFORMIN IS EFFECTIVE

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)5 found that metformin significantly reduced the incidence of:

- Any diabetes-related end point (hazard ratio [HR] 0.68, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.53–0.87)

- Myocardial infarction (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.41–0.89)

- Diabetes-related death (HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.37–0.91)

- All-cause mortality (HR 0.64; 95% CI 0.45–0.91).

The Hyperinsulinemia: Outcomes of Its Metabolic Effects (HOME) trial,6 a multicenter trial conducted in the Netherlands, evaluated the effect of adding metformin (vs placebo) to existing insulin regimens. Metformin recipients had a significantly lower rate of macrovascular mortality (HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.40–0.94, P = .02), but not of the primary end point, an aggregate of microvascular and macrovascular morbidity and mortality.

The Study on the Prognosis and Effect of Antidiabetic Drugs on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus With Coronary Artery Disease trial,7 a multicenter trial conducted in China, compared the effects of metformin vs glipizide on cardiovascular outcomes. At about 3 years of treatment, the metformin group had a significantly lower rate of the composite primary end point of recurrent cardiovascular events (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.30–0.90). This end point included nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, arterial revascularization by percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty or by coronary artery bypass graft, death from a cardiovascular cause, and death from any cause.

These studies prompted the ADA to emphasize that metformin can reduce the risk of cardiovascular events or death. Metformin also has been shown to be weight-neutral or to induce slight weight loss. Furthermore, it is inexpensive.

WHAT ABOUT THE RENAL EFFECTS?

Because metformin is renally cleared, it has caused some concern about nephrotoxicity, especially lactic acidosis, in patients with impaired renal function. But the most recent guidelines have relaxed the criteria for metformin use in this patient population.

Revised labeling

Metformin’s labeling,8 revised in 2016, states the following:

- If the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, metformin is contraindicated

- If the eGFR is between 30 and 45 mL/min/1.73 m2, metformin is not recommended

- If the eGFR is below 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 in a patient taking metformin, the risks and benefits of continuing treatment should be assessed, the dosage may need to be adjusted, and renal function should be monitored more frequently.8

These labeling revisions were based on a systematic review by Inzucchi et al9 that found metformin is not associated with increased rates of lactic acidosis in patients with mild to moderate kidney disease. Subsequently, an observational study published in 2018 by Lazarus et al10 showed that metformin increases the risk of acidosis only at eGFR levels below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Also, a Cochrane review published in 2003 did not find a single case of lactic acidosis in 347 trials with 70,490 patient-years of metformin treatment.11

Previous guidelines used serum creatinine levels, with metformin contraindicated at levels of 1.5 mg/dL or above for men and 1.4 mg/dL for women, or with abnormal creatinine clearance. The ADA and the AACE now use the eGFR1,2 instead of the serum creatinine level to measure kidney function because it better accounts for factors such as the patient’s age, sex, race, and weight.

Despite the evidence, the common patient perception is that metformin is nephrotoxic, and it is important for practitioners to dispel this myth during clinic visits.

What about metformin use with contrast agents?

Labeling has a precautionary note stating that metformin should be held at the time of, or prior to, any imaging procedure involving iodinated contrast agents in patients with an eGFR between 30 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2; in patients with a history of hepatic impairment, alcoholism, or heart failure; or in patients who will receive intra-arterial iodinated contrast. The eGFR should be reevaluated 48 hours after the imaging procedure.8

Additionally, if the iodinated contrast agent causes acute kidney injury, metformin could accumulate, with resultant lactate accumulation.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) has proposed less stringent guidelines for metformin during radiocontrast imaging studies. This change is based on evidence that lactic acidosis is rare—about 10 cases per 100,000 patient-years—and that there are no reports of lactic acidosis after intravenously administered iodinated contrast in properly selected patients.12,13

The ACR divides patients taking metformin into 2 categories:

- No evidence of acute kidney injury and eGFR greater than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2

- Either acute kidney injury or chronic kidney disease with eGFR below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 or undergoing arterial catheter studies with a high chance of embolization to the renal arteries.14

For the first group, they recommend against discontinuing metformin before or after giving iodinated contrast or checking kidney function after the procedure.

For the second group, they recommend holding metformin before and 48 hours after the procedure. It should not be restarted until renal function is confirmed to be normal.

METFORMIN AND INSULIN

The ADA recommends1 continuing metformin after initiating insulin. However, in clinical practice, it is often not done.

Clinical trials have shown that combining metformin with insulin significantly improves glycemic control, prevents weight gain, and decreases insulin requirements.15,16 One trial16 also looked at cardiovascular end points during a 4-year follow-up period; combining metformin with insulin decreased the macrovascular disease-related event rate compared with insulin alone.

In the HOME trial,6 which added metformin to the existing insulin regimen, both groups gained weight, but the metformin group had gained about 3 kg less than the placebo group at the end of the 4.3-year trial. Metformin did not increase the risk of hypoglycemia, but it also did not reduce the risk of microvascular disease.

Concomitant metformin reduces costs

These days, practitioners can choose from a large selection of diabetes drugs. These include insulins with better pharmacokinetic profiles, as well as newer classes of noninsulin agents such as sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues.

Metformin is less expensive than these newer drugs, and using it concomitantly with other diabetes drugs can decrease their dosage requirements, which in turn decreases their monthly costs.

GASTROINTESTINAL EFFECTS

Metformin’s gastrointestinal adverse effects such as diarrhea, flatulence, nausea, and vomiting are a barrier to its use. The actual incidence rate of diarrhea varies widely in randomized trials and observational studies, and gastrointestinal effects are worse in metformin-naive patients, as well as those who have chronic gastritis or Helicobacter pylori infection.17

We have found that starting metformin at a low dose and up-titrating it over several weeks increases tolerability. We often start patients at 500 mg/day and increase the dosage by 1 500-mg tablet every 1 to 2 weeks. Also, we have noticed that intolerance is more likely in patients who eat a high-carbohydrate diet, but there is no high-level evidence to back this up because patients in clinical trials all undergo nutrition counseling and are therefore more likely to adhere to the low-carbohydrate diet.

Also, the extended-release formulation is more tolerable than the immediate-release formulation and has similar glycemic efficacy. It may be an option as first-line therapy or for patients who have significant adverse effects from immediate-release metformin.18 For patients on the immediate-release formulation, taking it with meals helps lessen some gastrointestinal effects, and this should be emphasized at every visit.

Finally, we limit the metformin dose to 2,000 mg/day, rather than the 2,550 mg/day allowed on labeling. Garber et al19 found that the lower dosage still provides the maximum clinical efficacy.

OTHER CAUTIONS

Metformin should be avoided in patients with acute or unstable heart failure because of the increased risk of lactic acidosis.

It also should be avoided in patients with hepatic impairment, according to the labeling. But this remains controversial in practice. Zhang et al20 showed that continuing metformin in patients with diabetes and cirrhosis decreases the mortality risk by 57% compared with those taken off metformin.

Diet and lifestyle measures need to be emphasized at each visit. Wing et al21 showed that calorie restriction regardless of weight loss is beneficial for glycemic control and insulin sensitivity in obese patients with diabetes.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

Metformin improves glycemic control without tending to cause weight gain or hypoglycemia. It may also have cardiovascular benefits. Metformin is an inexpensive agent that should be continued, if tolerated, in those who need additional agents for glycemic control. It should be considered in all adult patients with type 2 diabetes.

- American Diabetes Association. 8. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care 2018; 41(suppl 1):S73–S85. doi:10.2337/dc18-S008

- Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2018 executive summary. Endocr Pract 2018; 24(1):91–120. doi:10.4158/CS-2017-0153

- Hampp C, Borders-Hemphill V, Moeny DG, Wysowski DK. Use of antidiabetic drugs in the US, 2003–2012. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(5):1367–1374. doi:10.2337/dc13-2289

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012; 35(6):1364–1379. doi:10.2337/dc12-0413

- Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet 1998; 352(9131):854–865. pmid:9742977

- Kooy A, de Jager J, Lehert P, et al. Long-term effects of metformin on metabolism and microvascular and macrovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(6):616–625. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.20

- Hong J, Zhang Y, Lai S, et al; SPREAD-DIMCAD Investigators. Effects of metformin versus glipizide on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. Diabetes Care 2013; 36(5):1304–1311. doi:10.2337/dc12-0719

- Glucophage (metformin hydrochloride) and Glucophage XR (extended-release) [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/020357s034,021202s018lbl.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2018.

- Inzucchi SE, Lipska KJ, Mayo H, Bailey CJ, McGuire DK. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease: a systematic review. JAMA 2014; 312(24):2668–2675. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.15298

- Lazarus B, Wu A, Shin JI, et al. Association of metformin use with risk of lactic acidosis across the range of kidney function: a community-based cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178(7):903–910. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0292

- Salpeter S, Greyber E, Pasternak G, Salpeter E. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; (2):CD002967. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002967

- Eppenga WL, Lalmohamed A, Geerts AF, et al. Risk of lactic acidosis or elevated lactate concentrations in metformin users with renal impairment: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(8):2218–2224. doi:10.2337/dc13-3023

- Richy FF, Sabidó-Espin M, Guedes S, Corvino FA, Gottwald-Hostalek U. Incidence of lactic acidosis in patients with type 2 diabetes with and without renal impairment treated with metformin: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(8):2291–2295. doi:10.2337/dc14-0464

- American College of Radiology (ACR). Manual on Contrast Media. Version 10.3. www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Contrast-Manual. Accessed December 5, 2018.

- Wulffele MG, Kooy A, Lehert P, et al. Combination of insulin and metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002; 25(12):2133–2140. pmid:12453950

- Kooy A, de Jager J, Lehert P, et al. Long-term effects of metformin on metabolism and microvascular and macrovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(6):616–625. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.20

- Bonnet F, Scheen A. Understanding and overcoming metformin gastrointestinal intolerance, Diabetes Obes Metab 2017; 19(4):473–481. doi:10.1111/dom.12854

- Jabbour S, Ziring B. Advantages of extended-release metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Postgrad Med 2011; 123(1):15–23. doi:10.3810/pgm.2011.01.2241

- Garber AJ, Duncan TG, Goodman AM, Mills DJ, Rohlf JL. Efficacy of metformin in type II diabetes: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response trial. Am J Med 1997; 103(6):491–497. pmid:9428832

- Zhang X, Harmsen WS, Mettler TA, et al. Continuation of metformin use after a diagnosis of cirrhosis significantly improves survival of patients with diabetes. Hepatology 2014; 60(6):2008–2016. doi:10.1002/hep.27199

- Wing RR, Blair EH, Bononi P, Marcus MD, Watanabe R, Bergman RN. Caloric restriction per se is a significant factor in improvements in glycemic control and insulin sensitivity during weight loss in obese NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care 1994; 17(1):30–36. pmid:8112186

- American Diabetes Association. 8. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care 2018; 41(suppl 1):S73–S85. doi:10.2337/dc18-S008

- Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2018 executive summary. Endocr Pract 2018; 24(1):91–120. doi:10.4158/CS-2017-0153

- Hampp C, Borders-Hemphill V, Moeny DG, Wysowski DK. Use of antidiabetic drugs in the US, 2003–2012. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(5):1367–1374. doi:10.2337/dc13-2289

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012; 35(6):1364–1379. doi:10.2337/dc12-0413

- Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet 1998; 352(9131):854–865. pmid:9742977

- Kooy A, de Jager J, Lehert P, et al. Long-term effects of metformin on metabolism and microvascular and macrovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(6):616–625. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.20

- Hong J, Zhang Y, Lai S, et al; SPREAD-DIMCAD Investigators. Effects of metformin versus glipizide on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. Diabetes Care 2013; 36(5):1304–1311. doi:10.2337/dc12-0719

- Glucophage (metformin hydrochloride) and Glucophage XR (extended-release) [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/020357s034,021202s018lbl.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2018.

- Inzucchi SE, Lipska KJ, Mayo H, Bailey CJ, McGuire DK. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease: a systematic review. JAMA 2014; 312(24):2668–2675. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.15298

- Lazarus B, Wu A, Shin JI, et al. Association of metformin use with risk of lactic acidosis across the range of kidney function: a community-based cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178(7):903–910. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0292

- Salpeter S, Greyber E, Pasternak G, Salpeter E. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; (2):CD002967. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002967

- Eppenga WL, Lalmohamed A, Geerts AF, et al. Risk of lactic acidosis or elevated lactate concentrations in metformin users with renal impairment: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(8):2218–2224. doi:10.2337/dc13-3023

- Richy FF, Sabidó-Espin M, Guedes S, Corvino FA, Gottwald-Hostalek U. Incidence of lactic acidosis in patients with type 2 diabetes with and without renal impairment treated with metformin: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(8):2291–2295. doi:10.2337/dc14-0464

- American College of Radiology (ACR). Manual on Contrast Media. Version 10.3. www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Contrast-Manual. Accessed December 5, 2018.

- Wulffele MG, Kooy A, Lehert P, et al. Combination of insulin and metformin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002; 25(12):2133–2140. pmid:12453950

- Kooy A, de Jager J, Lehert P, et al. Long-term effects of metformin on metabolism and microvascular and macrovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(6):616–625. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.20

- Bonnet F, Scheen A. Understanding and overcoming metformin gastrointestinal intolerance, Diabetes Obes Metab 2017; 19(4):473–481. doi:10.1111/dom.12854

- Jabbour S, Ziring B. Advantages of extended-release metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Postgrad Med 2011; 123(1):15–23. doi:10.3810/pgm.2011.01.2241

- Garber AJ, Duncan TG, Goodman AM, Mills DJ, Rohlf JL. Efficacy of metformin in type II diabetes: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response trial. Am J Med 1997; 103(6):491–497. pmid:9428832

- Zhang X, Harmsen WS, Mettler TA, et al. Continuation of metformin use after a diagnosis of cirrhosis significantly improves survival of patients with diabetes. Hepatology 2014; 60(6):2008–2016. doi:10.1002/hep.27199

- Wing RR, Blair EH, Bononi P, Marcus MD, Watanabe R, Bergman RN. Caloric restriction per se is a significant factor in improvements in glycemic control and insulin sensitivity during weight loss in obese NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care 1994; 17(1):30–36. pmid:8112186

Rapidly progressive pleural effusion

A 33-year-old male nonsmoker with no significant medical history presented to the pulmonary clinic with severe left-sided pleuritic chest pain and mild breathlessness for the past 5 days. He denied fever, chills, cough, phlegm, runny nose, or congestion.

Five days before this visit, he had been seen in the emergency department with mild left-sided pleuritic chest pain. His vital signs at that time had been as follows:

- Blood pressure 141/77 mm Hg

- Heart rate 77 beats/minute

- Respiratory rate 17 breaths/minute

- Temperature 36.8°C (98.2°F)

- Oxygen saturation 98% on room air.

- White blood cell count 6.89 × 109/L (reference range 3.70–11.00)

- Neutrophils 58% (40%–70%)

- Lymphocytes 29.6% (22%–44%)

- Monocytes 10.7% (0–11%)

- Eosinophils 1% (0–4%)

- Basophils 0.6% (0–1%)

- Troponin T and D-dimer levels normal.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF PLEURITIC CHEST PAIN

1. What is the most likely cause of his pleuritic chest pain?

- Pleuritis

- Pneumonia

- Pulmonary embolism

- Malignancy

The differential diagnosis of pleuritic chest pain is broad.

The patient’s symptoms at presentation to the emergency department did not suggest an infectious process. There was no fever, cough, or phlegm, and his white blood cell count was normal. Nonetheless, pneumonia could not be ruled out, as the lung parenchyma was not normal on radiography, and the findings could have been consistent with an early or resolving infectious process.

Pulmonary embolism was a possibility, but his normal D-dimer level argued against it. Further, the patient subsequently underwent CT angiography, which ruled out pulmonary embolism.

Malignancy was unlikely in a young nonsmoker, but follow-up imaging would be needed to ensure resolution and rule this out.

The emergency department physician diagnosed inflammatory pleuritis and discharged him home on a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

CLINIC VISIT 5 DAYS LATER

At his pulmonary clinic visit 5 days later, the patient reported persistent but stable left-sided pleuritic chest pain and mild breathlessness on exertion. His blood pressure was 137/81 mm Hg, heart rate 109 beats per minute, temperature 37.1°C (98.8°F), and oxygen saturation 97% on room air.

Auscultation of the lungs revealed rales and slightly decreased breath sounds at the left base. No dullness to percussion could be detected.

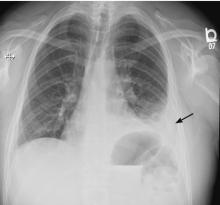

Because the patient had developed mild tachycardia and breathlessness along with clinical signs that suggested worsening infiltrates, consolidation, or the development of pleural effusion, he underwent further investigation with chest radiography, a complete blood cell count, and measurement of serum inflammatory markers.

- White blood cell count 13.08 × 109/L

- Neutrophils 81%

- Lymphocytes 7.4%

- Monocytes 7.2%

- Eeosinophils 0.2%

- Basophils 0.2%

- Procalcitonin 0.34 µg/L (reference range < 0.09).

Bedside ultrasonography to assess the effusion’s size and characteristics and the need for thoracentesis indicated that the effusion was too small to tap, and there were no fibrinous strands or loculations to suggest empyema.

FURTHER TREATMENT

2. What was the best management strategy for this patient at this time?

- Admit to the hospital for thoracentesis and intravenous antibiotics

- Give oral antibiotics with close follow-up

- Perform thoracentesis on an outpatient basis and give oral antibiotics

- Repeat chest CT

The patient had worsening pleuritic pain with development of a small left pleural effusion. His symptoms had not improved on a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. He now had an elevated white blood cell count with a “left shift” (ie, an increase in neutrophils, indicating more immature cells in circulation) and elevated procalcitonin. The most likely diagnosis was pneumonia with a resulting pleural effusion, ie, parapneumonic effusion, requiring appropriate antibiotic therapy. Ideally, the pleural effusion should be sampled by thoracentesis, with management on an outpatient or inpatient basis.

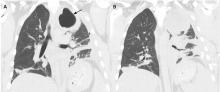

5 DAYS LATER, THE EFFUSION HAD BECOME MASSIVE

On follow-up 5 days later, the patient’s chest pain was better, but he was significantly more short of breath. His blood pressure was 137/90 mm Hg, heart rate 117 beats/minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths/minute, oxygen saturation 97% on room air, and temperature 36.9°C (98.4°F). Chest auscultation revealed decreased breath sounds over the left hemithorax, with dullness to percussion and decreased fremitus.

RAPIDLY PROGRESSIVE PLEURAL EFFUSIONS

A rapidly progressive pleural effusion in a healthy patient suggests parapneumonic effusion. The most likely organism is streptococcal.2

Explosive pleuritis is defined as a pleural effusion that increases in size in less than 24 hours. It was first described by Braman and Donat3 in 1986 as an effusion that develops within hours of admission. In 2001, Sharma and Marrie4 refined the definition as rapid development of pleural effusion involving more than 90% of the hemithorax within 24 hours, causing compression of pulmonary tissue and a mediastinal shift. It is a medical emergency that requires prompt investigation and treatment with drainage and antibiotics. All reported cases of explosive pleuritis have been parapneumonic effusion.

The organisms implicated in explosive pleuritis include gram-positive cocci such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, S pyogenes, other streptococci, staphylococci, and gram-negative cocci such as Neisseria meningitidis and Moraxella catarrhalis. Gram-negative bacilli include Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas species, Escherichia coli, Proteus species, Enterobacter species, Bacteroides species, and Legionella species.4,5 However, malignancy is the most common cause of massive pleural effusion, accounting for 54% of cases; 17% of cases are idiopathic, 13% are parapneumonic, and 12% are hydrothorax related to liver cirrhosis.6

CASE CONTINUED

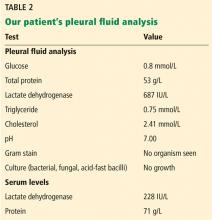

Our patient’s massive effusion needed drainage, and he was admitted to the hospital for further management. Samples of blood and sputum were sent for culture. Intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam was started, and an intercostal chest tube was inserted into the pleural cavity under ultrasonographic guidance to drain turbid fluid.

Multiple pleural fluid samples sent for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli culture were negative. Blood and sputum cultures also showed no growth. The administration of oral antibiotics for 5 days on an outpatient basis before pleural fluid culture could have led to sterility of all cultures.

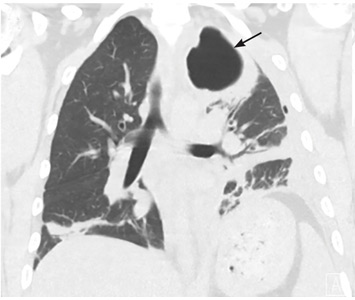

Our patient had inadequate pleural fluid output through his chest tube, and radiography showed that the pleural collections failed to clear. In fact, an apical locule did not appear to be connecting with the lower aspect of the pleural collection. In such cases, instillation of intrapleural agents through the chest tube has become common practice in an attempt to lyse adhesions, to connect various locules or pockets of pleural fluid, and to improve drainage.

LOCULATED EMPYEMA: MANAGEMENT

3. What was the best management strategy for this loculated empyema?

- Continue intravenous antibiotics and existing chest tube drainage for 5 to 7 days, then reassess

- Continue intravenous antibiotics and instill intrapleural fibrinolytics (eg, tissue plasminogen activator [tPA]) through the existing chest tube

- Continue intravenous antibiotics and instill intrapleural fibrinolytics with deoxyribonuclease (DNase) into the existing chest tube

- Continue intravenous antibiotics, insert a second chest tube into the apical pocket under imaging guidance, and instill tPA and DNase

- Surgical decortication

Continuing antibiotics with existing chest tube drainage and the two options of using single-agent intrapleural fibrinolytics have been shown to be less effective than combining tPA and DNase when managing a loculated empyema. As such, surgical decortication, attempting intrapleural instillation of fibrinolytics and DNase (with or without further chest tube insertion into noncommunicating locules), or both were the most appropriate options at this stage.

MANAGEMENT OF PARAPNEUMONIC PLEURAL EFFUSION IN ADULTS

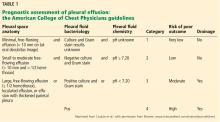

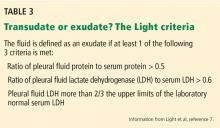

There are several options for managing parapneumonic effusion, and clinicians can use the classification system in Table 1 to assess the risk of a poor outcome and to plan the management. Based on radiographic findings and pleural fluid sampling, a pleural effusion can be either observed or drained.

Options for drainage of the pleural space include repeat thoracentesis, surgical insertion of a chest tube, or image-guided insertion of a small-bore catheter. Although no randomized trial has been done to compare tube sizes, a large retrospective series showed that small-bore tubes (< 14 F) perform similarly to standard large-bore tubes.8 However, in another study, Keeling et al9 reported higher failure rates when tubes smaller than 12 F were used. Regular flushing of the chest tube (ideally twice a day) is recommended to keep it patent, particularly with small-bore tubes. Multiloculated empyema may require multiple intercostal chest tubes to drain completely, and therefore small-bore tubes are recommended.

In cases that do not improve radiographically and clinically, one must consider whether the antibiotic choice is adequate, review the position of the chest tube, and assess for loculations. As such, repeating chest CT within 24 to 48 hours of tube insertion and drainage is recommended to confirm adequate tube positioning, assess effective drainage, look for different locules and pockets, and determine the degree of communication between them.

The largest well-powered randomized controlled trials of intrapleural agents in the management of pleural infection, the Multicentre Intrapleural Sepsis Trial (MIST1)10 and MIST2,11 clearly demonstrated that intrapleural fibrinolytics were not beneficial when used alone compared with placebo. However, in MIST2, the combination of tPA and DNase led to clinically significant benefits including radiologic improvement, shorter hospital stay, and less need for surgical decortication.

At our hospital, we follow the MIST2 protocol using a combination of tPA and DNase given intrapleurally twice daily for 3 days. In our patient, we inserted a chest tube into the apical pocket under ultrasonographic guidance, as 2 instillations of intrapleural tPA and DNase did not result in drainage of the apical locule.

Success rates with intrapleural tPA-DNase for complicated pleural effusion and empyema range from 68% to 92%.12–15 Pleural thickening and necrotizing pneumonia and abscess are important predictors of failure of tPA-DNase therapy and of the need for surgery.13,14

Early surgical intervention was another reasonable option in this case. The decision to proceed with surgery is based on need to debride multiloculated empyemas or uniloculated empyemas that fail to resolve with antibiotics and tube thoracostomy drainage. Nonetheless, the decision must be individualized and based on factors such as the patient’s risks vs possible benefit from a surgical procedure under general anesthesia, the patient’s ability to tolerate multiple thoracentesis procedures and chest tubes for a potentially lengthy period, the patient’s pain threshold, the patient’s wishes to avoid a surgical procedure balanced against a longer hospital stay, and cultural norms and beliefs.

Surgical options include video-assisted thoracoscopy, thoracotomy, and open drainage. Decortication can be considered early to control pleural sepsis, or late (after 3 to 6 months) if the lung does not expand. Debate continues on the optimal timing for video-assisted thoracoscopy, with data suggesting that when the procedure is performed later in the course of the disease there is a greater chance of complications and of the need to convert to thoracotomy.

A 2017 Cochrane review16 of surgical vs nonsurgical management of empyema identified 8 randomized trials, 6 in children and 2 in adults, with a total of 391 patients. The authors compared video-assisted thoracoscopy vs tube thoracotomy, with and without intrapleural fibrinolytics. They noted no difference in rates of mortality or procedural complications. However, the mean length of hospital stay was shorter with video-assisted thoracoscopy than with tube thoracotomy (5.9 vs 15.4 days). They could not assess the impact of fibrinolytic therapy on total cost of treatment in the 2 groups.

A randomized trial is planned to compare early video-assisted thoracoscopy vs treatment with chest tube drainage and t-PA-DNase.17

At our institution, we use a multidisciplinary approach, discussing cases at weekly meetings with thoracic surgeons, pulmonologists, infectious disease specialists, and interventional radiologists. We generally try conservative management first, with chest tube drainage and intrapleural agents for 5 to 7 days, before considering surgery if the response is unsatisfactory.

THE PATIENT RECOVERED

In our patient, the multiloculated empyema was successfully cleared after intrapleural instillation of 4 doses of tPA and DNAse over 3 days and insertion of a second intercostal chest tube into the noncommunicating apical locule. He completed 14 days of intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam treatment and, after discharge home, completed another 4 weeks of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate. He made a full recovery and was back at work 2 weeks after discharge. Chest radiography 10 weeks after discharge showed normal results.

- Colice GL, Curtis A, Deslauriers J, et al. Medical and surgical treatment of parapneumonic effusions: an evidence-based guideline. Chest 2000; 118(4):1158–1171. pmid:11035692

- Bryant RE, Salmon CJ. Pleural empyema. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 22(5):747–762. pmid:8722927

- Braman SS, Donat WE. Explosive pleuritis. Manifestation of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection. Am J Med 1986; 81(4):723–726. pmid:3532794

- Sharma JK, Marrie TJ. Explosive pleuritis. Can J Infect Dis 2001; 12(2):104–107. pmid:18159325

- Johnson JL. Pleurisy, fever, and rapidly progressive pleural effusion in a healthy, 29-year-old physician. Chest 2001; 119(4):1266–1269. pmid:11296198

- Jimenez D, Diaz G, Gil D, et al. Etiology and prognostic significance of massive pleural effusions. Respir Med 2005; 99(9):1183–1187. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2005.02.022

- Light RW, MacGregor MI, Luchsinger PC, Ball WC Jr. Pleural effusions: the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates. Ann Intern Med 1972; 77:507–513. pmid:4642731

- Rahman NM, Maskell NA, Davies CW, et al. The relationship between chest tube size and clinical outcome in pleural infection. Chest 2010; 137(3):536–543. doi:10.1378/chest.09-1044

- Keeling AN, Leong S, Logan PM, Lee MJ. Empyema and effusion: outcome of image-guided small-bore catheter drainage. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2008; 31(1):135–141. doi:10.1007/s00270-007-9197-0

- Maskell NA, Davies CW, Nunn AJ, et al. UK controlled trial of intrapleural streptokinase for pleural infection. N Engl J Med 2005; 352(9):865–874. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa042473

- Rahman NM, Maskell NA, West A, et al. Intrapleural use of tissue plasminogen activator and DNase in pleural infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 365(6):518–526. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1012740

- Piccolo F, Pitman N, Bhatnagar R, et al. Intrapleural tissue plasminogen activator and deoxyribonuclease for pleural infection. An effective and safe alternative to surgery. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014; 11(9):1419–1425. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201407-329OC

- Khemasuwan D, Sorensen J, Griffin DC. Predictive variables for failure in administration of intrapleural tissue plasminogen activator/deoxyribonuclease in patients with complicated parapneumonic effusions/empyema. Chest 2018; 154(3):550–556. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.037

- Abu-Daff S, Maziak DE, Alshehab D, et al. Intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy (IPFT) in loculated pleural effusions—analysis of predictors for failure of therapy and bleeding: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2013; 3(2):e001887. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001887

- Bishwakarma R, Shah S, Frank L, Zhang W, Sharma G, Nishi SP. Mixing it up: coadministration of tPA/DNase in complicated parapneumonic pleural effusions and empyema. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2017; 24(1):40–47. doi:10.1097/LBR.0000000000000334

- Redden MD, Chin TY, van Driel ML. Surgical versus non-surgical management for pleural empyema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 3:CD010651. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010651.pub2

- Feller-Kopman D, Light R. Pleural disease. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(8):740–751. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1403503

A 33-year-old male nonsmoker with no significant medical history presented to the pulmonary clinic with severe left-sided pleuritic chest pain and mild breathlessness for the past 5 days. He denied fever, chills, cough, phlegm, runny nose, or congestion.

Five days before this visit, he had been seen in the emergency department with mild left-sided pleuritic chest pain. His vital signs at that time had been as follows:

- Blood pressure 141/77 mm Hg

- Heart rate 77 beats/minute

- Respiratory rate 17 breaths/minute

- Temperature 36.8°C (98.2°F)

- Oxygen saturation 98% on room air.

- White blood cell count 6.89 × 109/L (reference range 3.70–11.00)

- Neutrophils 58% (40%–70%)

- Lymphocytes 29.6% (22%–44%)

- Monocytes 10.7% (0–11%)

- Eosinophils 1% (0–4%)

- Basophils 0.6% (0–1%)

- Troponin T and D-dimer levels normal.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF PLEURITIC CHEST PAIN

1. What is the most likely cause of his pleuritic chest pain?

- Pleuritis

- Pneumonia

- Pulmonary embolism

- Malignancy

The differential diagnosis of pleuritic chest pain is broad.

The patient’s symptoms at presentation to the emergency department did not suggest an infectious process. There was no fever, cough, or phlegm, and his white blood cell count was normal. Nonetheless, pneumonia could not be ruled out, as the lung parenchyma was not normal on radiography, and the findings could have been consistent with an early or resolving infectious process.

Pulmonary embolism was a possibility, but his normal D-dimer level argued against it. Further, the patient subsequently underwent CT angiography, which ruled out pulmonary embolism.

Malignancy was unlikely in a young nonsmoker, but follow-up imaging would be needed to ensure resolution and rule this out.

The emergency department physician diagnosed inflammatory pleuritis and discharged him home on a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

CLINIC VISIT 5 DAYS LATER

At his pulmonary clinic visit 5 days later, the patient reported persistent but stable left-sided pleuritic chest pain and mild breathlessness on exertion. His blood pressure was 137/81 mm Hg, heart rate 109 beats per minute, temperature 37.1°C (98.8°F), and oxygen saturation 97% on room air.

Auscultation of the lungs revealed rales and slightly decreased breath sounds at the left base. No dullness to percussion could be detected.

Because the patient had developed mild tachycardia and breathlessness along with clinical signs that suggested worsening infiltrates, consolidation, or the development of pleural effusion, he underwent further investigation with chest radiography, a complete blood cell count, and measurement of serum inflammatory markers.

- White blood cell count 13.08 × 109/L

- Neutrophils 81%

- Lymphocytes 7.4%

- Monocytes 7.2%

- Eeosinophils 0.2%

- Basophils 0.2%

- Procalcitonin 0.34 µg/L (reference range < 0.09).

Bedside ultrasonography to assess the effusion’s size and characteristics and the need for thoracentesis indicated that the effusion was too small to tap, and there were no fibrinous strands or loculations to suggest empyema.

FURTHER TREATMENT

2. What was the best management strategy for this patient at this time?

- Admit to the hospital for thoracentesis and intravenous antibiotics

- Give oral antibiotics with close follow-up

- Perform thoracentesis on an outpatient basis and give oral antibiotics

- Repeat chest CT

The patient had worsening pleuritic pain with development of a small left pleural effusion. His symptoms had not improved on a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. He now had an elevated white blood cell count with a “left shift” (ie, an increase in neutrophils, indicating more immature cells in circulation) and elevated procalcitonin. The most likely diagnosis was pneumonia with a resulting pleural effusion, ie, parapneumonic effusion, requiring appropriate antibiotic therapy. Ideally, the pleural effusion should be sampled by thoracentesis, with management on an outpatient or inpatient basis.

5 DAYS LATER, THE EFFUSION HAD BECOME MASSIVE

On follow-up 5 days later, the patient’s chest pain was better, but he was significantly more short of breath. His blood pressure was 137/90 mm Hg, heart rate 117 beats/minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths/minute, oxygen saturation 97% on room air, and temperature 36.9°C (98.4°F). Chest auscultation revealed decreased breath sounds over the left hemithorax, with dullness to percussion and decreased fremitus.

RAPIDLY PROGRESSIVE PLEURAL EFFUSIONS

A rapidly progressive pleural effusion in a healthy patient suggests parapneumonic effusion. The most likely organism is streptococcal.2

Explosive pleuritis is defined as a pleural effusion that increases in size in less than 24 hours. It was first described by Braman and Donat3 in 1986 as an effusion that develops within hours of admission. In 2001, Sharma and Marrie4 refined the definition as rapid development of pleural effusion involving more than 90% of the hemithorax within 24 hours, causing compression of pulmonary tissue and a mediastinal shift. It is a medical emergency that requires prompt investigation and treatment with drainage and antibiotics. All reported cases of explosive pleuritis have been parapneumonic effusion.

The organisms implicated in explosive pleuritis include gram-positive cocci such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, S pyogenes, other streptococci, staphylococci, and gram-negative cocci such as Neisseria meningitidis and Moraxella catarrhalis. Gram-negative bacilli include Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas species, Escherichia coli, Proteus species, Enterobacter species, Bacteroides species, and Legionella species.4,5 However, malignancy is the most common cause of massive pleural effusion, accounting for 54% of cases; 17% of cases are idiopathic, 13% are parapneumonic, and 12% are hydrothorax related to liver cirrhosis.6

CASE CONTINUED

Our patient’s massive effusion needed drainage, and he was admitted to the hospital for further management. Samples of blood and sputum were sent for culture. Intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam was started, and an intercostal chest tube was inserted into the pleural cavity under ultrasonographic guidance to drain turbid fluid.

Multiple pleural fluid samples sent for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli culture were negative. Blood and sputum cultures also showed no growth. The administration of oral antibiotics for 5 days on an outpatient basis before pleural fluid culture could have led to sterility of all cultures.

Our patient had inadequate pleural fluid output through his chest tube, and radiography showed that the pleural collections failed to clear. In fact, an apical locule did not appear to be connecting with the lower aspect of the pleural collection. In such cases, instillation of intrapleural agents through the chest tube has become common practice in an attempt to lyse adhesions, to connect various locules or pockets of pleural fluid, and to improve drainage.

LOCULATED EMPYEMA: MANAGEMENT

3. What was the best management strategy for this loculated empyema?

- Continue intravenous antibiotics and existing chest tube drainage for 5 to 7 days, then reassess

- Continue intravenous antibiotics and instill intrapleural fibrinolytics (eg, tissue plasminogen activator [tPA]) through the existing chest tube

- Continue intravenous antibiotics and instill intrapleural fibrinolytics with deoxyribonuclease (DNase) into the existing chest tube

- Continue intravenous antibiotics, insert a second chest tube into the apical pocket under imaging guidance, and instill tPA and DNase

- Surgical decortication

Continuing antibiotics with existing chest tube drainage and the two options of using single-agent intrapleural fibrinolytics have been shown to be less effective than combining tPA and DNase when managing a loculated empyema. As such, surgical decortication, attempting intrapleural instillation of fibrinolytics and DNase (with or without further chest tube insertion into noncommunicating locules), or both were the most appropriate options at this stage.

MANAGEMENT OF PARAPNEUMONIC PLEURAL EFFUSION IN ADULTS

There are several options for managing parapneumonic effusion, and clinicians can use the classification system in Table 1 to assess the risk of a poor outcome and to plan the management. Based on radiographic findings and pleural fluid sampling, a pleural effusion can be either observed or drained.

Options for drainage of the pleural space include repeat thoracentesis, surgical insertion of a chest tube, or image-guided insertion of a small-bore catheter. Although no randomized trial has been done to compare tube sizes, a large retrospective series showed that small-bore tubes (< 14 F) perform similarly to standard large-bore tubes.8 However, in another study, Keeling et al9 reported higher failure rates when tubes smaller than 12 F were used. Regular flushing of the chest tube (ideally twice a day) is recommended to keep it patent, particularly with small-bore tubes. Multiloculated empyema may require multiple intercostal chest tubes to drain completely, and therefore small-bore tubes are recommended.

In cases that do not improve radiographically and clinically, one must consider whether the antibiotic choice is adequate, review the position of the chest tube, and assess for loculations. As such, repeating chest CT within 24 to 48 hours of tube insertion and drainage is recommended to confirm adequate tube positioning, assess effective drainage, look for different locules and pockets, and determine the degree of communication between them.

The largest well-powered randomized controlled trials of intrapleural agents in the management of pleural infection, the Multicentre Intrapleural Sepsis Trial (MIST1)10 and MIST2,11 clearly demonstrated that intrapleural fibrinolytics were not beneficial when used alone compared with placebo. However, in MIST2, the combination of tPA and DNase led to clinically significant benefits including radiologic improvement, shorter hospital stay, and less need for surgical decortication.

At our hospital, we follow the MIST2 protocol using a combination of tPA and DNase given intrapleurally twice daily for 3 days. In our patient, we inserted a chest tube into the apical pocket under ultrasonographic guidance, as 2 instillations of intrapleural tPA and DNase did not result in drainage of the apical locule.

Success rates with intrapleural tPA-DNase for complicated pleural effusion and empyema range from 68% to 92%.12–15 Pleural thickening and necrotizing pneumonia and abscess are important predictors of failure of tPA-DNase therapy and of the need for surgery.13,14

Early surgical intervention was another reasonable option in this case. The decision to proceed with surgery is based on need to debride multiloculated empyemas or uniloculated empyemas that fail to resolve with antibiotics and tube thoracostomy drainage. Nonetheless, the decision must be individualized and based on factors such as the patient’s risks vs possible benefit from a surgical procedure under general anesthesia, the patient’s ability to tolerate multiple thoracentesis procedures and chest tubes for a potentially lengthy period, the patient’s pain threshold, the patient’s wishes to avoid a surgical procedure balanced against a longer hospital stay, and cultural norms and beliefs.

Surgical options include video-assisted thoracoscopy, thoracotomy, and open drainage. Decortication can be considered early to control pleural sepsis, or late (after 3 to 6 months) if the lung does not expand. Debate continues on the optimal timing for video-assisted thoracoscopy, with data suggesting that when the procedure is performed later in the course of the disease there is a greater chance of complications and of the need to convert to thoracotomy.

A 2017 Cochrane review16 of surgical vs nonsurgical management of empyema identified 8 randomized trials, 6 in children and 2 in adults, with a total of 391 patients. The authors compared video-assisted thoracoscopy vs tube thoracotomy, with and without intrapleural fibrinolytics. They noted no difference in rates of mortality or procedural complications. However, the mean length of hospital stay was shorter with video-assisted thoracoscopy than with tube thoracotomy (5.9 vs 15.4 days). They could not assess the impact of fibrinolytic therapy on total cost of treatment in the 2 groups.

A randomized trial is planned to compare early video-assisted thoracoscopy vs treatment with chest tube drainage and t-PA-DNase.17

At our institution, we use a multidisciplinary approach, discussing cases at weekly meetings with thoracic surgeons, pulmonologists, infectious disease specialists, and interventional radiologists. We generally try conservative management first, with chest tube drainage and intrapleural agents for 5 to 7 days, before considering surgery if the response is unsatisfactory.

THE PATIENT RECOVERED

In our patient, the multiloculated empyema was successfully cleared after intrapleural instillation of 4 doses of tPA and DNAse over 3 days and insertion of a second intercostal chest tube into the noncommunicating apical locule. He completed 14 days of intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam treatment and, after discharge home, completed another 4 weeks of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate. He made a full recovery and was back at work 2 weeks after discharge. Chest radiography 10 weeks after discharge showed normal results.

A 33-year-old male nonsmoker with no significant medical history presented to the pulmonary clinic with severe left-sided pleuritic chest pain and mild breathlessness for the past 5 days. He denied fever, chills, cough, phlegm, runny nose, or congestion.

Five days before this visit, he had been seen in the emergency department with mild left-sided pleuritic chest pain. His vital signs at that time had been as follows:

- Blood pressure 141/77 mm Hg

- Heart rate 77 beats/minute

- Respiratory rate 17 breaths/minute

- Temperature 36.8°C (98.2°F)

- Oxygen saturation 98% on room air.

- White blood cell count 6.89 × 109/L (reference range 3.70–11.00)

- Neutrophils 58% (40%–70%)

- Lymphocytes 29.6% (22%–44%)

- Monocytes 10.7% (0–11%)

- Eosinophils 1% (0–4%)

- Basophils 0.6% (0–1%)

- Troponin T and D-dimer levels normal.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF PLEURITIC CHEST PAIN

1. What is the most likely cause of his pleuritic chest pain?

- Pleuritis

- Pneumonia

- Pulmonary embolism

- Malignancy

The differential diagnosis of pleuritic chest pain is broad.

The patient’s symptoms at presentation to the emergency department did not suggest an infectious process. There was no fever, cough, or phlegm, and his white blood cell count was normal. Nonetheless, pneumonia could not be ruled out, as the lung parenchyma was not normal on radiography, and the findings could have been consistent with an early or resolving infectious process.

Pulmonary embolism was a possibility, but his normal D-dimer level argued against it. Further, the patient subsequently underwent CT angiography, which ruled out pulmonary embolism.

Malignancy was unlikely in a young nonsmoker, but follow-up imaging would be needed to ensure resolution and rule this out.

The emergency department physician diagnosed inflammatory pleuritis and discharged him home on a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

CLINIC VISIT 5 DAYS LATER

At his pulmonary clinic visit 5 days later, the patient reported persistent but stable left-sided pleuritic chest pain and mild breathlessness on exertion. His blood pressure was 137/81 mm Hg, heart rate 109 beats per minute, temperature 37.1°C (98.8°F), and oxygen saturation 97% on room air.

Auscultation of the lungs revealed rales and slightly decreased breath sounds at the left base. No dullness to percussion could be detected.

Because the patient had developed mild tachycardia and breathlessness along with clinical signs that suggested worsening infiltrates, consolidation, or the development of pleural effusion, he underwent further investigation with chest radiography, a complete blood cell count, and measurement of serum inflammatory markers.

- White blood cell count 13.08 × 109/L

- Neutrophils 81%

- Lymphocytes 7.4%

- Monocytes 7.2%

- Eeosinophils 0.2%

- Basophils 0.2%

- Procalcitonin 0.34 µg/L (reference range < 0.09).

Bedside ultrasonography to assess the effusion’s size and characteristics and the need for thoracentesis indicated that the effusion was too small to tap, and there were no fibrinous strands or loculations to suggest empyema.

FURTHER TREATMENT

2. What was the best management strategy for this patient at this time?

- Admit to the hospital for thoracentesis and intravenous antibiotics

- Give oral antibiotics with close follow-up

- Perform thoracentesis on an outpatient basis and give oral antibiotics