User login

VRIC Abstract Submission Site Now Open

The Vascular Research Initiatives Conference emphasizes emerging vascular science and encourages interactive participation of attendees. Scheduled the day before Vascular Discovery Scientific Sessions, VRIC is considered a key event for connecting with vascular researchers. Join us for the 2020 program "VRIC Chicago 2020: From Discovery to Translation." The SVS is now accepting abstracts for the program and will continue through January 7. Submit your abstract now and be a part of this important event for vascular researchers.

The Vascular Research Initiatives Conference emphasizes emerging vascular science and encourages interactive participation of attendees. Scheduled the day before Vascular Discovery Scientific Sessions, VRIC is considered a key event for connecting with vascular researchers. Join us for the 2020 program "VRIC Chicago 2020: From Discovery to Translation." The SVS is now accepting abstracts for the program and will continue through January 7. Submit your abstract now and be a part of this important event for vascular researchers.

The Vascular Research Initiatives Conference emphasizes emerging vascular science and encourages interactive participation of attendees. Scheduled the day before Vascular Discovery Scientific Sessions, VRIC is considered a key event for connecting with vascular researchers. Join us for the 2020 program "VRIC Chicago 2020: From Discovery to Translation." The SVS is now accepting abstracts for the program and will continue through January 7. Submit your abstract now and be a part of this important event for vascular researchers.

CVD risk in black SLE patients 18 times higher than in whites

ATLANTA – Black race was the single greatest predictor of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in systemic lupus erythematosus, with black patients having an 18-fold higher risk than white patients from 2 years before to 8 years after diagnosis, according to a review of 336 patients in the Georgia Lupus Registry that was presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The greatest risk was in the first 2 years after diagnosis, which has been reported before in white patients, but not before in a mostly (75%) black cohort.

Lupus is known to strike earlier and be more aggressive in black patients, so “we were expecting racial disparities in incident CVD, but” the magnitude of the increased risk “was very surprising. This study [identifies] a population that needs more attention, more targeted CVD prevention. We have to intervene early and be on top of everything,” especially for black patients, said lead investigator Shivani Garg, MD, an assistant professor of rheumatology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Lipids, blood pressure, and the other usual CVD risk factors, as well as lupus itself, have to be optimally controlled; glucocorticoid use limited as much as possible; and there needs to be improved adherence to hydroxychloroquine, which has been shown to reduce CVD events in lupus patients, she said in an interview.

The 336 patients, mostly women (87%) from the Atlanta area, were diagnosed during 2002-2004 at a mean age of 40 years. Dr. Garg and associates reviewed CVD events – ischemic heart disease, stroke, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral vascular disease – and death over 16 years, beginning 2 years before diagnosis.

About 22% of subjects had a CVD event, most commonly within 2 years after diagnosis. The risk was 500% higher in black patients overall (adjusted hazard ratio, 6.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.4-17.5; P = .0003), and markedly higher in the first 10 years (aHR, 18; 95% CI, 2.2-141; P less than .0001). The findings were not adjusted for socioeconomic factors.

In the first 12 years of the study, the mean age at lupus diagnosis was 46 years and the first CVD event occurred at an average of 48 years. From 12 to 16 years follow-up, the mean age of diagnosis was 38 years, and the first CVD event occurred at 52 years.

Age older than 65 years (aHR, 7.9; 95% CI, 2.2-29) and the presence of disease-associated antibodies (aHR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.01-4.4) increased CVD risk, which wasn’t surprising, but another predictor – discoid lupus – was unexpected (aHR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.5-6.8). “A lot of times, we’ve considered discoid rash to be a milder form, but these patients have some kind of chronic, smoldering inflammation that is leading to atherosclerosis,” Dr. Garg said.

At diagnosis, 84% of the subjects had lupus hematologic disorders, 69% immunologic disorders, and 14% a discoid rash. CVD risk factor data were not collected.

There was no external funding, and the investigators reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Garg S et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 805.

ATLANTA – Black race was the single greatest predictor of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in systemic lupus erythematosus, with black patients having an 18-fold higher risk than white patients from 2 years before to 8 years after diagnosis, according to a review of 336 patients in the Georgia Lupus Registry that was presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The greatest risk was in the first 2 years after diagnosis, which has been reported before in white patients, but not before in a mostly (75%) black cohort.

Lupus is known to strike earlier and be more aggressive in black patients, so “we were expecting racial disparities in incident CVD, but” the magnitude of the increased risk “was very surprising. This study [identifies] a population that needs more attention, more targeted CVD prevention. We have to intervene early and be on top of everything,” especially for black patients, said lead investigator Shivani Garg, MD, an assistant professor of rheumatology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Lipids, blood pressure, and the other usual CVD risk factors, as well as lupus itself, have to be optimally controlled; glucocorticoid use limited as much as possible; and there needs to be improved adherence to hydroxychloroquine, which has been shown to reduce CVD events in lupus patients, she said in an interview.

The 336 patients, mostly women (87%) from the Atlanta area, were diagnosed during 2002-2004 at a mean age of 40 years. Dr. Garg and associates reviewed CVD events – ischemic heart disease, stroke, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral vascular disease – and death over 16 years, beginning 2 years before diagnosis.

About 22% of subjects had a CVD event, most commonly within 2 years after diagnosis. The risk was 500% higher in black patients overall (adjusted hazard ratio, 6.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.4-17.5; P = .0003), and markedly higher in the first 10 years (aHR, 18; 95% CI, 2.2-141; P less than .0001). The findings were not adjusted for socioeconomic factors.

In the first 12 years of the study, the mean age at lupus diagnosis was 46 years and the first CVD event occurred at an average of 48 years. From 12 to 16 years follow-up, the mean age of diagnosis was 38 years, and the first CVD event occurred at 52 years.

Age older than 65 years (aHR, 7.9; 95% CI, 2.2-29) and the presence of disease-associated antibodies (aHR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.01-4.4) increased CVD risk, which wasn’t surprising, but another predictor – discoid lupus – was unexpected (aHR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.5-6.8). “A lot of times, we’ve considered discoid rash to be a milder form, but these patients have some kind of chronic, smoldering inflammation that is leading to atherosclerosis,” Dr. Garg said.

At diagnosis, 84% of the subjects had lupus hematologic disorders, 69% immunologic disorders, and 14% a discoid rash. CVD risk factor data were not collected.

There was no external funding, and the investigators reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Garg S et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 805.

ATLANTA – Black race was the single greatest predictor of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in systemic lupus erythematosus, with black patients having an 18-fold higher risk than white patients from 2 years before to 8 years after diagnosis, according to a review of 336 patients in the Georgia Lupus Registry that was presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The greatest risk was in the first 2 years after diagnosis, which has been reported before in white patients, but not before in a mostly (75%) black cohort.

Lupus is known to strike earlier and be more aggressive in black patients, so “we were expecting racial disparities in incident CVD, but” the magnitude of the increased risk “was very surprising. This study [identifies] a population that needs more attention, more targeted CVD prevention. We have to intervene early and be on top of everything,” especially for black patients, said lead investigator Shivani Garg, MD, an assistant professor of rheumatology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Lipids, blood pressure, and the other usual CVD risk factors, as well as lupus itself, have to be optimally controlled; glucocorticoid use limited as much as possible; and there needs to be improved adherence to hydroxychloroquine, which has been shown to reduce CVD events in lupus patients, she said in an interview.

The 336 patients, mostly women (87%) from the Atlanta area, were diagnosed during 2002-2004 at a mean age of 40 years. Dr. Garg and associates reviewed CVD events – ischemic heart disease, stroke, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral vascular disease – and death over 16 years, beginning 2 years before diagnosis.

About 22% of subjects had a CVD event, most commonly within 2 years after diagnosis. The risk was 500% higher in black patients overall (adjusted hazard ratio, 6.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.4-17.5; P = .0003), and markedly higher in the first 10 years (aHR, 18; 95% CI, 2.2-141; P less than .0001). The findings were not adjusted for socioeconomic factors.

In the first 12 years of the study, the mean age at lupus diagnosis was 46 years and the first CVD event occurred at an average of 48 years. From 12 to 16 years follow-up, the mean age of diagnosis was 38 years, and the first CVD event occurred at 52 years.

Age older than 65 years (aHR, 7.9; 95% CI, 2.2-29) and the presence of disease-associated antibodies (aHR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.01-4.4) increased CVD risk, which wasn’t surprising, but another predictor – discoid lupus – was unexpected (aHR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.5-6.8). “A lot of times, we’ve considered discoid rash to be a milder form, but these patients have some kind of chronic, smoldering inflammation that is leading to atherosclerosis,” Dr. Garg said.

At diagnosis, 84% of the subjects had lupus hematologic disorders, 69% immunologic disorders, and 14% a discoid rash. CVD risk factor data were not collected.

There was no external funding, and the investigators reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Garg S et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 805.

REPORTING FROM ACR 2019

Blood-brain barrier imaging could predict disease progression in bipolar

Blood-brain barrier imaging can serve as a biomarker for progression of disease in adults with bipolar disorder, results from a small study suggest.

“While the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder remains poorly understood, converging evidence points to the presence of neuroinflammation in bipolar patients,” wrote Lyna Kamintsky, a PhD candidate at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and colleagues.

The researchers examined MRI data from 36 patients with bipolar disorder and compared them with 14 matched controls. The average age of the patients was 49 years and the average duration of illness was 28 years. The study was published in NeuroImage: Clinical (2019 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102049).

“Leakage rates were considered pathological when exceeding 0.02, the 95th percentile of all values in a cohort of control subjects,” the researchers said. Overall, 10 subjects (all patients with bipolar disorder) met criteria for “extensive blood-brain barrier leakage.” The researchers found that those patients also had higher rates of chronic illness, more frequent and/or severe manic episodes, and more severe anxiety, depression, and social/occupational dysfunction, compared with those without blood-brain barrier leakage.

The patients with extensive blood-brain barrier leakage also had higher body mass indexes, greater risk of cardiovascular disease, and advanced heart age. In addition, all patients in this group had comorbid insulin resistance.

The study findings were limited by the small sample size, but , the researchers said.

The study was supported by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program, the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation, Brain Canada, and the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. The researchers disclosed having no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Kamintsky L et al. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2019 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102049.

Blood-brain barrier imaging can serve as a biomarker for progression of disease in adults with bipolar disorder, results from a small study suggest.

“While the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder remains poorly understood, converging evidence points to the presence of neuroinflammation in bipolar patients,” wrote Lyna Kamintsky, a PhD candidate at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and colleagues.

The researchers examined MRI data from 36 patients with bipolar disorder and compared them with 14 matched controls. The average age of the patients was 49 years and the average duration of illness was 28 years. The study was published in NeuroImage: Clinical (2019 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102049).

“Leakage rates were considered pathological when exceeding 0.02, the 95th percentile of all values in a cohort of control subjects,” the researchers said. Overall, 10 subjects (all patients with bipolar disorder) met criteria for “extensive blood-brain barrier leakage.” The researchers found that those patients also had higher rates of chronic illness, more frequent and/or severe manic episodes, and more severe anxiety, depression, and social/occupational dysfunction, compared with those without blood-brain barrier leakage.

The patients with extensive blood-brain barrier leakage also had higher body mass indexes, greater risk of cardiovascular disease, and advanced heart age. In addition, all patients in this group had comorbid insulin resistance.

The study findings were limited by the small sample size, but , the researchers said.

The study was supported by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program, the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation, Brain Canada, and the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. The researchers disclosed having no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Kamintsky L et al. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2019 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102049.

Blood-brain barrier imaging can serve as a biomarker for progression of disease in adults with bipolar disorder, results from a small study suggest.

“While the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder remains poorly understood, converging evidence points to the presence of neuroinflammation in bipolar patients,” wrote Lyna Kamintsky, a PhD candidate at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and colleagues.

The researchers examined MRI data from 36 patients with bipolar disorder and compared them with 14 matched controls. The average age of the patients was 49 years and the average duration of illness was 28 years. The study was published in NeuroImage: Clinical (2019 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102049).

“Leakage rates were considered pathological when exceeding 0.02, the 95th percentile of all values in a cohort of control subjects,” the researchers said. Overall, 10 subjects (all patients with bipolar disorder) met criteria for “extensive blood-brain barrier leakage.” The researchers found that those patients also had higher rates of chronic illness, more frequent and/or severe manic episodes, and more severe anxiety, depression, and social/occupational dysfunction, compared with those without blood-brain barrier leakage.

The patients with extensive blood-brain barrier leakage also had higher body mass indexes, greater risk of cardiovascular disease, and advanced heart age. In addition, all patients in this group had comorbid insulin resistance.

The study findings were limited by the small sample size, but , the researchers said.

The study was supported by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program, the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation, Brain Canada, and the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. The researchers disclosed having no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Kamintsky L et al. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2019 Oct 22. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102049.

FROM NEUROIMAGE: CLINICAL

Product News November 2019

Aklief Cream Topical Retinoid Approved for Acne Vulgaris

Galderma Laboratories, LP, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Aklief (trifarotene) Cream 0.005% for the treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 9 years and older. Trifarotene is a retinoid that selectively targets retinoic acid receptor γ. Aklief Cream treats both facial and truncal acne. Aklief Cream is expected to be available in the United States in November 2019 in a 45-g pump. For more information, visit www.galderma.com.

Altreno Lotion Now Available in a 20-g Tube for Dermatologist Dispensing

Ortho Dermatologics launches a 20-g tube of Altreno (tretinoin) Lotion 0.05% for dermatologists to dispense in their offices. Offering the product in the physician’s office helps ensure that patients will be ready to begin their acne regimen, increasing patient compliance. Altreno Lotion is approved for the treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 9 years and older. It provides efficacy and tolerability in a once-daily dosing regimen. For more information, visit www.altrenohcp.com.

Amzeeq Topical Minocycline Approved for Acne

Foamix Pharmaceuticals Ltd receives US Food and Drug Administration approval of Amzeeq (minocycline) Foam 4% for the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris in patients 9 years and older. Foamix’s proprietary Molecule Stabilizing Technology is used to effectively deliver minocycline—a broad-spectrum antibiotic—in a foam-based vehicle for once-daily application. Amzeeq is expected to be available for prescribing in January 2020. For more information, visit www.foamix.com.

FDA Clears Protego Antimicrobial Wound Dressing

Turn Therapeutics, Inc, receives US Food and Drug Administration clearance of Protego antimicrobial wound dressing for acute and chronic wound management. Protego wound dressings are single-use, sterile, antimicrobial gauze dressings impregnated with Hexagen, a proprietary petrolatum-based wound care emulsion. Protego offers patients the utility of traditional petrolatum-saturated gauze dressings with the added benefit of broad-spectrum antimicrobial protection against bacteria, fungi, and yeasts. For more information, visit www.turntherapeutics.com.

Skin Cancer Foundation Champions for Change Gala Raises More Than $700,000

The Skin Cancer Foundation held its 23rd annual Champions for Change Gala on October 17, 2019. The foundation’s signature fundraising event raised more than $700,000 to support educational campaigns, community programs, and research initiatives. More than 400 guests attended the event at The Plaza Hotel in New York, New York. The event was emceed by comedian Tom Kelly, and President Dr. Deborah S. Sarnoff reflected on the 40th birthday of the foundation, reinforcing the goal “to change behaviors and save lives.” For more information, visit www.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Aklief Cream Topical Retinoid Approved for Acne Vulgaris

Galderma Laboratories, LP, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Aklief (trifarotene) Cream 0.005% for the treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 9 years and older. Trifarotene is a retinoid that selectively targets retinoic acid receptor γ. Aklief Cream treats both facial and truncal acne. Aklief Cream is expected to be available in the United States in November 2019 in a 45-g pump. For more information, visit www.galderma.com.

Altreno Lotion Now Available in a 20-g Tube for Dermatologist Dispensing

Ortho Dermatologics launches a 20-g tube of Altreno (tretinoin) Lotion 0.05% for dermatologists to dispense in their offices. Offering the product in the physician’s office helps ensure that patients will be ready to begin their acne regimen, increasing patient compliance. Altreno Lotion is approved for the treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 9 years and older. It provides efficacy and tolerability in a once-daily dosing regimen. For more information, visit www.altrenohcp.com.

Amzeeq Topical Minocycline Approved for Acne

Foamix Pharmaceuticals Ltd receives US Food and Drug Administration approval of Amzeeq (minocycline) Foam 4% for the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris in patients 9 years and older. Foamix’s proprietary Molecule Stabilizing Technology is used to effectively deliver minocycline—a broad-spectrum antibiotic—in a foam-based vehicle for once-daily application. Amzeeq is expected to be available for prescribing in January 2020. For more information, visit www.foamix.com.

FDA Clears Protego Antimicrobial Wound Dressing

Turn Therapeutics, Inc, receives US Food and Drug Administration clearance of Protego antimicrobial wound dressing for acute and chronic wound management. Protego wound dressings are single-use, sterile, antimicrobial gauze dressings impregnated with Hexagen, a proprietary petrolatum-based wound care emulsion. Protego offers patients the utility of traditional petrolatum-saturated gauze dressings with the added benefit of broad-spectrum antimicrobial protection against bacteria, fungi, and yeasts. For more information, visit www.turntherapeutics.com.

Skin Cancer Foundation Champions for Change Gala Raises More Than $700,000

The Skin Cancer Foundation held its 23rd annual Champions for Change Gala on October 17, 2019. The foundation’s signature fundraising event raised more than $700,000 to support educational campaigns, community programs, and research initiatives. More than 400 guests attended the event at The Plaza Hotel in New York, New York. The event was emceed by comedian Tom Kelly, and President Dr. Deborah S. Sarnoff reflected on the 40th birthday of the foundation, reinforcing the goal “to change behaviors and save lives.” For more information, visit www.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Aklief Cream Topical Retinoid Approved for Acne Vulgaris

Galderma Laboratories, LP, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Aklief (trifarotene) Cream 0.005% for the treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 9 years and older. Trifarotene is a retinoid that selectively targets retinoic acid receptor γ. Aklief Cream treats both facial and truncal acne. Aklief Cream is expected to be available in the United States in November 2019 in a 45-g pump. For more information, visit www.galderma.com.

Altreno Lotion Now Available in a 20-g Tube for Dermatologist Dispensing

Ortho Dermatologics launches a 20-g tube of Altreno (tretinoin) Lotion 0.05% for dermatologists to dispense in their offices. Offering the product in the physician’s office helps ensure that patients will be ready to begin their acne regimen, increasing patient compliance. Altreno Lotion is approved for the treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 9 years and older. It provides efficacy and tolerability in a once-daily dosing regimen. For more information, visit www.altrenohcp.com.

Amzeeq Topical Minocycline Approved for Acne

Foamix Pharmaceuticals Ltd receives US Food and Drug Administration approval of Amzeeq (minocycline) Foam 4% for the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris in patients 9 years and older. Foamix’s proprietary Molecule Stabilizing Technology is used to effectively deliver minocycline—a broad-spectrum antibiotic—in a foam-based vehicle for once-daily application. Amzeeq is expected to be available for prescribing in January 2020. For more information, visit www.foamix.com.

FDA Clears Protego Antimicrobial Wound Dressing

Turn Therapeutics, Inc, receives US Food and Drug Administration clearance of Protego antimicrobial wound dressing for acute and chronic wound management. Protego wound dressings are single-use, sterile, antimicrobial gauze dressings impregnated with Hexagen, a proprietary petrolatum-based wound care emulsion. Protego offers patients the utility of traditional petrolatum-saturated gauze dressings with the added benefit of broad-spectrum antimicrobial protection against bacteria, fungi, and yeasts. For more information, visit www.turntherapeutics.com.

Skin Cancer Foundation Champions for Change Gala Raises More Than $700,000

The Skin Cancer Foundation held its 23rd annual Champions for Change Gala on October 17, 2019. The foundation’s signature fundraising event raised more than $700,000 to support educational campaigns, community programs, and research initiatives. More than 400 guests attended the event at The Plaza Hotel in New York, New York. The event was emceed by comedian Tom Kelly, and President Dr. Deborah S. Sarnoff reflected on the 40th birthday of the foundation, reinforcing the goal “to change behaviors and save lives.” For more information, visit www.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

How I became a better doctor

I became a better doctor on the day I became a cardiac patient. On that day, I experienced the helpless, vulnerable, and needy feelings of a patient’s dependency and blind trust of a physician whom I did not know. I suddenly realized how it feels to be a patient.

My entire life, I had always been an athlete in excellent shape. My 7-day-a-week daily schedule included seeing patients, being an expert psychiatric witness for disability cases, playing 2 hours of tennis, walking/running for 1 hour, and ending the night with 1 hour on a stationary bike.

I get to see my children all the time. I am so fortunate to get to travel with them and play national father-son and father-daughter tennis tournaments. We have been ranked No. 1 in the country many times. I have won 16 gold balls in these tournaments, each symbolic of a U.S. championship.

As a busy board-certified psychiatrist, I had been featured in an article, “Well being: Tennis is doctor’s favorite medicine,” by Art Carey, in the Philadelphia Inquirer, posted May 2, 2011. The author discussed my diet and exercise regime, and how I used exercise to stay healthy and to deal with the stress of being a physician.

‘Take me to the hospital’

At the end of 2018, I had a complete blood count performed, and the results indicated that I had a lipid panel of a healthy 30-year-old; however, my delusional bubble burst in March 2019. I was the No. 1 seed in a National Father-Daughter Tennis Tournament in Chicago. We were in the semifinal match, we had won the first set, and we were up 3-0. I fell, hit my head on the net post, and was feeling nauseated. I checked for bleeding and continued playing, though I was not feeling well. Five minutes later, I experienced symptoms of very extreme gastrointestinal pain and nausea. I ran off the tennis court wanting to vomit and get rid of the symptom so I could go back and finish the match. I wanted to play in the finals the following day and try to win the tournament.

The kind, competent, compassionate, and warm tournament director said I looked gray – and he promptly called 911. The paramedics came and said they thought I may be having a heart attack. I was in denial since I had no chest pain and I thought I was super healthy; therefore, I could not be experiencing an acute myocardial infarction. I finally agreed to let technicians perform an EKG, and they told me that I had ST elevation. Reality finally set in and I realized I was having a heart attack. “Take me to the hospital,” I said.

At the Chicago hospital where I was taken, I told doctors and staff I was a physician. To my surprise, they did not care. I was not going to get any prioritized treatment. Despite all of my devotion to medicine, I was not even getting their top physician to treat me. I was being evaluated by a resident. I felt even more deflated.

They performed a cardiac catheterization and put in one stent in one vessel in the right cardiac vessel. I had many questions to ask, but everyone seemed very impatient and abrupt with me, acting like this was just a very routine procedure. No one ever adequately answered my questions. I was very disillusioned, and I felt very insignificant, scared, and invisible.

I was discharged a few days later and was told my heart problem was fixed. I was instructed to follow up with a cardiologist in Philadelphia when I got home.

The first night home, I experienced chest pain. I was alarmed and thought my stent may have collapsed, so I went to the emergency room of the Philadelphia area hospital I knew had the best cardiac staff. After another blood test, indicating raised troponin levels, I was informed they needed to perform another cardiac catheterization. I learned I had two more coronary artery blockages, each 95%-99%, in the left ventricle.

I was shocked. How could the doctor in Chicago have made such a significant mistake? What happened? I would never know.

The interventional cardiologist in Philadelphia was able to repair one coronary artery, but the other blockage in the LED vessel (yes, the widow maker) had calcified too much for a stent. I would need cardiac bypass surgery. This was very unbelievable to me, and furthermore, I would have to wait 2 long weeks for the anticoagulant effect of the Brilinta to wear off before I could undergo bypass surgery.

While I anxiously waited for the big day, I was calling either my cardiologist, surgeon, or his nurse practitioner almost daily with questions and concerns; after all, this was a life-threatening and momentous event. Thankfully, I was met with great patience, understanding, and promptness of detailed answers and explanations by all involved with my cardiac care. The reactions of the staff made me mindful of the importance of really hearing my patients’ concerns and addressing their issues in a prompt, nonjudgmental, patient, and genuine manner. I am grateful that my robotic cardiac bypass surgery on March 26, 2019, went very well, and I am now back to work, playing tennis, jogging slowly, and riding my stationery bike.

Changed perspective on practice

I had always thought of myself as a warm, caring, and empathic psychiatrist, but my experience as a cardiac patient made me realize that there is always room for improvement in treating my patients.

Remember, every doctor will become a patient one day, and the reality of illness, injury, and mortality may really hit you hard, as it did me. You may not receive any prioritized treatment and you will know what it feels like to be helpless, vulnerable, and at the mercy of a physician while you regress in the service of the ego and become a patient.

You can be a better doctor now if you are mindful that whatever the physical, emotional, or mental issue facing your patients, the problem may be catastrophic to them. They need your undivided attention. Any problem is a significant event to your presenting patient. Really listen to his or her concerns or questions, and address every one with patience, understanding, and accurate information. If you follow these lessons, which I learned the hard way, you can become a better doctor.

I followed my doctor’s instructions and I started hitting tennis balls gradually. I worked myself back into shape and with my daughter Julia Cohen, and we won the USTA National Father Daughter Clay Court Championship in Florida 6 months after I had the heart attack during a national tennis tournament. This is the comeback of the year in tennis!

Dr. Cohen has had a private practice in psychiatry for more than 35 years. He is a former professor of psychiatry, family medicine, and otolaryngology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. Dr. Cohen has been a nationally ranked tennis player from age 12 to the present, served as captain of the University of Pennsylvania tennis team, and ranked No. 1 in tennis in the middle states section and in the country in various categories and times. He was inducted into the Philadelphia Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 2012.

I became a better doctor on the day I became a cardiac patient. On that day, I experienced the helpless, vulnerable, and needy feelings of a patient’s dependency and blind trust of a physician whom I did not know. I suddenly realized how it feels to be a patient.

My entire life, I had always been an athlete in excellent shape. My 7-day-a-week daily schedule included seeing patients, being an expert psychiatric witness for disability cases, playing 2 hours of tennis, walking/running for 1 hour, and ending the night with 1 hour on a stationary bike.

I get to see my children all the time. I am so fortunate to get to travel with them and play national father-son and father-daughter tennis tournaments. We have been ranked No. 1 in the country many times. I have won 16 gold balls in these tournaments, each symbolic of a U.S. championship.

As a busy board-certified psychiatrist, I had been featured in an article, “Well being: Tennis is doctor’s favorite medicine,” by Art Carey, in the Philadelphia Inquirer, posted May 2, 2011. The author discussed my diet and exercise regime, and how I used exercise to stay healthy and to deal with the stress of being a physician.

‘Take me to the hospital’

At the end of 2018, I had a complete blood count performed, and the results indicated that I had a lipid panel of a healthy 30-year-old; however, my delusional bubble burst in March 2019. I was the No. 1 seed in a National Father-Daughter Tennis Tournament in Chicago. We were in the semifinal match, we had won the first set, and we were up 3-0. I fell, hit my head on the net post, and was feeling nauseated. I checked for bleeding and continued playing, though I was not feeling well. Five minutes later, I experienced symptoms of very extreme gastrointestinal pain and nausea. I ran off the tennis court wanting to vomit and get rid of the symptom so I could go back and finish the match. I wanted to play in the finals the following day and try to win the tournament.

The kind, competent, compassionate, and warm tournament director said I looked gray – and he promptly called 911. The paramedics came and said they thought I may be having a heart attack. I was in denial since I had no chest pain and I thought I was super healthy; therefore, I could not be experiencing an acute myocardial infarction. I finally agreed to let technicians perform an EKG, and they told me that I had ST elevation. Reality finally set in and I realized I was having a heart attack. “Take me to the hospital,” I said.

At the Chicago hospital where I was taken, I told doctors and staff I was a physician. To my surprise, they did not care. I was not going to get any prioritized treatment. Despite all of my devotion to medicine, I was not even getting their top physician to treat me. I was being evaluated by a resident. I felt even more deflated.

They performed a cardiac catheterization and put in one stent in one vessel in the right cardiac vessel. I had many questions to ask, but everyone seemed very impatient and abrupt with me, acting like this was just a very routine procedure. No one ever adequately answered my questions. I was very disillusioned, and I felt very insignificant, scared, and invisible.

I was discharged a few days later and was told my heart problem was fixed. I was instructed to follow up with a cardiologist in Philadelphia when I got home.

The first night home, I experienced chest pain. I was alarmed and thought my stent may have collapsed, so I went to the emergency room of the Philadelphia area hospital I knew had the best cardiac staff. After another blood test, indicating raised troponin levels, I was informed they needed to perform another cardiac catheterization. I learned I had two more coronary artery blockages, each 95%-99%, in the left ventricle.

I was shocked. How could the doctor in Chicago have made such a significant mistake? What happened? I would never know.

The interventional cardiologist in Philadelphia was able to repair one coronary artery, but the other blockage in the LED vessel (yes, the widow maker) had calcified too much for a stent. I would need cardiac bypass surgery. This was very unbelievable to me, and furthermore, I would have to wait 2 long weeks for the anticoagulant effect of the Brilinta to wear off before I could undergo bypass surgery.

While I anxiously waited for the big day, I was calling either my cardiologist, surgeon, or his nurse practitioner almost daily with questions and concerns; after all, this was a life-threatening and momentous event. Thankfully, I was met with great patience, understanding, and promptness of detailed answers and explanations by all involved with my cardiac care. The reactions of the staff made me mindful of the importance of really hearing my patients’ concerns and addressing their issues in a prompt, nonjudgmental, patient, and genuine manner. I am grateful that my robotic cardiac bypass surgery on March 26, 2019, went very well, and I am now back to work, playing tennis, jogging slowly, and riding my stationery bike.

Changed perspective on practice

I had always thought of myself as a warm, caring, and empathic psychiatrist, but my experience as a cardiac patient made me realize that there is always room for improvement in treating my patients.

Remember, every doctor will become a patient one day, and the reality of illness, injury, and mortality may really hit you hard, as it did me. You may not receive any prioritized treatment and you will know what it feels like to be helpless, vulnerable, and at the mercy of a physician while you regress in the service of the ego and become a patient.

You can be a better doctor now if you are mindful that whatever the physical, emotional, or mental issue facing your patients, the problem may be catastrophic to them. They need your undivided attention. Any problem is a significant event to your presenting patient. Really listen to his or her concerns or questions, and address every one with patience, understanding, and accurate information. If you follow these lessons, which I learned the hard way, you can become a better doctor.

I followed my doctor’s instructions and I started hitting tennis balls gradually. I worked myself back into shape and with my daughter Julia Cohen, and we won the USTA National Father Daughter Clay Court Championship in Florida 6 months after I had the heart attack during a national tennis tournament. This is the comeback of the year in tennis!

Dr. Cohen has had a private practice in psychiatry for more than 35 years. He is a former professor of psychiatry, family medicine, and otolaryngology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. Dr. Cohen has been a nationally ranked tennis player from age 12 to the present, served as captain of the University of Pennsylvania tennis team, and ranked No. 1 in tennis in the middle states section and in the country in various categories and times. He was inducted into the Philadelphia Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 2012.

I became a better doctor on the day I became a cardiac patient. On that day, I experienced the helpless, vulnerable, and needy feelings of a patient’s dependency and blind trust of a physician whom I did not know. I suddenly realized how it feels to be a patient.

My entire life, I had always been an athlete in excellent shape. My 7-day-a-week daily schedule included seeing patients, being an expert psychiatric witness for disability cases, playing 2 hours of tennis, walking/running for 1 hour, and ending the night with 1 hour on a stationary bike.

I get to see my children all the time. I am so fortunate to get to travel with them and play national father-son and father-daughter tennis tournaments. We have been ranked No. 1 in the country many times. I have won 16 gold balls in these tournaments, each symbolic of a U.S. championship.

As a busy board-certified psychiatrist, I had been featured in an article, “Well being: Tennis is doctor’s favorite medicine,” by Art Carey, in the Philadelphia Inquirer, posted May 2, 2011. The author discussed my diet and exercise regime, and how I used exercise to stay healthy and to deal with the stress of being a physician.

‘Take me to the hospital’

At the end of 2018, I had a complete blood count performed, and the results indicated that I had a lipid panel of a healthy 30-year-old; however, my delusional bubble burst in March 2019. I was the No. 1 seed in a National Father-Daughter Tennis Tournament in Chicago. We were in the semifinal match, we had won the first set, and we were up 3-0. I fell, hit my head on the net post, and was feeling nauseated. I checked for bleeding and continued playing, though I was not feeling well. Five minutes later, I experienced symptoms of very extreme gastrointestinal pain and nausea. I ran off the tennis court wanting to vomit and get rid of the symptom so I could go back and finish the match. I wanted to play in the finals the following day and try to win the tournament.

The kind, competent, compassionate, and warm tournament director said I looked gray – and he promptly called 911. The paramedics came and said they thought I may be having a heart attack. I was in denial since I had no chest pain and I thought I was super healthy; therefore, I could not be experiencing an acute myocardial infarction. I finally agreed to let technicians perform an EKG, and they told me that I had ST elevation. Reality finally set in and I realized I was having a heart attack. “Take me to the hospital,” I said.

At the Chicago hospital where I was taken, I told doctors and staff I was a physician. To my surprise, they did not care. I was not going to get any prioritized treatment. Despite all of my devotion to medicine, I was not even getting their top physician to treat me. I was being evaluated by a resident. I felt even more deflated.

They performed a cardiac catheterization and put in one stent in one vessel in the right cardiac vessel. I had many questions to ask, but everyone seemed very impatient and abrupt with me, acting like this was just a very routine procedure. No one ever adequately answered my questions. I was very disillusioned, and I felt very insignificant, scared, and invisible.

I was discharged a few days later and was told my heart problem was fixed. I was instructed to follow up with a cardiologist in Philadelphia when I got home.

The first night home, I experienced chest pain. I was alarmed and thought my stent may have collapsed, so I went to the emergency room of the Philadelphia area hospital I knew had the best cardiac staff. After another blood test, indicating raised troponin levels, I was informed they needed to perform another cardiac catheterization. I learned I had two more coronary artery blockages, each 95%-99%, in the left ventricle.

I was shocked. How could the doctor in Chicago have made such a significant mistake? What happened? I would never know.

The interventional cardiologist in Philadelphia was able to repair one coronary artery, but the other blockage in the LED vessel (yes, the widow maker) had calcified too much for a stent. I would need cardiac bypass surgery. This was very unbelievable to me, and furthermore, I would have to wait 2 long weeks for the anticoagulant effect of the Brilinta to wear off before I could undergo bypass surgery.

While I anxiously waited for the big day, I was calling either my cardiologist, surgeon, or his nurse practitioner almost daily with questions and concerns; after all, this was a life-threatening and momentous event. Thankfully, I was met with great patience, understanding, and promptness of detailed answers and explanations by all involved with my cardiac care. The reactions of the staff made me mindful of the importance of really hearing my patients’ concerns and addressing their issues in a prompt, nonjudgmental, patient, and genuine manner. I am grateful that my robotic cardiac bypass surgery on March 26, 2019, went very well, and I am now back to work, playing tennis, jogging slowly, and riding my stationery bike.

Changed perspective on practice

I had always thought of myself as a warm, caring, and empathic psychiatrist, but my experience as a cardiac patient made me realize that there is always room for improvement in treating my patients.

Remember, every doctor will become a patient one day, and the reality of illness, injury, and mortality may really hit you hard, as it did me. You may not receive any prioritized treatment and you will know what it feels like to be helpless, vulnerable, and at the mercy of a physician while you regress in the service of the ego and become a patient.

You can be a better doctor now if you are mindful that whatever the physical, emotional, or mental issue facing your patients, the problem may be catastrophic to them. They need your undivided attention. Any problem is a significant event to your presenting patient. Really listen to his or her concerns or questions, and address every one with patience, understanding, and accurate information. If you follow these lessons, which I learned the hard way, you can become a better doctor.

I followed my doctor’s instructions and I started hitting tennis balls gradually. I worked myself back into shape and with my daughter Julia Cohen, and we won the USTA National Father Daughter Clay Court Championship in Florida 6 months after I had the heart attack during a national tennis tournament. This is the comeback of the year in tennis!

Dr. Cohen has had a private practice in psychiatry for more than 35 years. He is a former professor of psychiatry, family medicine, and otolaryngology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. Dr. Cohen has been a nationally ranked tennis player from age 12 to the present, served as captain of the University of Pennsylvania tennis team, and ranked No. 1 in tennis in the middle states section and in the country in various categories and times. He was inducted into the Philadelphia Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 2012.

Guselkumab improves psoriatic arthritis regardless of prior TNFi use

ATLANTA – Guselkumab improved outcomes in psoriatic arthritis patients regardless of past treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in the phase 3 DISCOVER-1 trial.

The anti-interleukin-23p19 monoclonal antibody is approved in the United States for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (PsO).

Benefits in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) were seen in both biologic-naive and tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi)–treated patients and occurred with both 4- and 8-week dosing regimens, Atul Deodhar, MD, reported during a plenary session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

For example, the primary endpoint of ACR 20 response at 24 weeks was achieved in 58.6% and 52.8% of patients randomized to receive 100 mg of guselkumab delivered subcutaneously either at baseline and every 4 weeks or at baseline, week 4, and then every 8 weeks, respectively, compared with 22.2% of those randomized to receive placebo, said Dr. Deodhar, professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

Greater proportions of patients in the guselkumab groups achieved ACR 20 response at week 16; ACR 50 response at weeks 16 and 24; ACR 70 response at week 24; Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 75, 90, and 100 responses at week 24; and minimal disease activity response at week 24, he said, adding that improvements were also seen with guselkumab versus placebo for the controlled major secondary endpoints of change from baseline in Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index score, Short Form 36 Health Survey score, and investigator global assessment (IGA) of PsO response.

The response rates with guselkumab versus placebo were seen regardless of prior TNFi use, he said.

The study included 381 patients with active PsA, defined as three or more swollen joints, three or more tender joints, and C-reactive protein of 0.3 mg/dL or greater despite standard therapies. About 30% were exposed to up to two TNFi therapies and 10% were nonresponders or inadequate responders to those therapies.

Concomitant use of select nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, oral corticosteroids, and NSAIDs was allowed, and patients with less than 5% improvement in tender plus swollen joints at week 16 could initiate or increase the dose of the permitted medications while continuing study treatment, Dr. Deodhar said.

The mean body surface area with PsO involvement was 13.4%; 42.5% of patients had an IGA of 3-4 for skin involvement. Mean swollen and tender joint counts were 9.8 and 19.3, respectively, indicating a population with moderate to severe disease, he added.

Serious adverse events, serious infections, and death occurred in 2.4%, 0.5%, and 0.3% of patients, respectively.

“Both guselkumab regimens were safe and well tolerated through week 24,” Dr. Deodhar said, noting that the safety profile was consistent with that established in the treatment of PsO and described in the label.

DISCOVER-1 was funded by Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Deodhar reported relationships (advisory board activity, consulting, and/or research grant funding) with several pharmaceutical companies including Janssen. Several coauthors are employees of Janssen.

SOURCE: Deodhar A et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 807.

ATLANTA – Guselkumab improved outcomes in psoriatic arthritis patients regardless of past treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in the phase 3 DISCOVER-1 trial.

The anti-interleukin-23p19 monoclonal antibody is approved in the United States for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (PsO).

Benefits in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) were seen in both biologic-naive and tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi)–treated patients and occurred with both 4- and 8-week dosing regimens, Atul Deodhar, MD, reported during a plenary session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

For example, the primary endpoint of ACR 20 response at 24 weeks was achieved in 58.6% and 52.8% of patients randomized to receive 100 mg of guselkumab delivered subcutaneously either at baseline and every 4 weeks or at baseline, week 4, and then every 8 weeks, respectively, compared with 22.2% of those randomized to receive placebo, said Dr. Deodhar, professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

Greater proportions of patients in the guselkumab groups achieved ACR 20 response at week 16; ACR 50 response at weeks 16 and 24; ACR 70 response at week 24; Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 75, 90, and 100 responses at week 24; and minimal disease activity response at week 24, he said, adding that improvements were also seen with guselkumab versus placebo for the controlled major secondary endpoints of change from baseline in Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index score, Short Form 36 Health Survey score, and investigator global assessment (IGA) of PsO response.

The response rates with guselkumab versus placebo were seen regardless of prior TNFi use, he said.

The study included 381 patients with active PsA, defined as three or more swollen joints, three or more tender joints, and C-reactive protein of 0.3 mg/dL or greater despite standard therapies. About 30% were exposed to up to two TNFi therapies and 10% were nonresponders or inadequate responders to those therapies.

Concomitant use of select nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, oral corticosteroids, and NSAIDs was allowed, and patients with less than 5% improvement in tender plus swollen joints at week 16 could initiate or increase the dose of the permitted medications while continuing study treatment, Dr. Deodhar said.

The mean body surface area with PsO involvement was 13.4%; 42.5% of patients had an IGA of 3-4 for skin involvement. Mean swollen and tender joint counts were 9.8 and 19.3, respectively, indicating a population with moderate to severe disease, he added.

Serious adverse events, serious infections, and death occurred in 2.4%, 0.5%, and 0.3% of patients, respectively.

“Both guselkumab regimens were safe and well tolerated through week 24,” Dr. Deodhar said, noting that the safety profile was consistent with that established in the treatment of PsO and described in the label.

DISCOVER-1 was funded by Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Deodhar reported relationships (advisory board activity, consulting, and/or research grant funding) with several pharmaceutical companies including Janssen. Several coauthors are employees of Janssen.

SOURCE: Deodhar A et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 807.

ATLANTA – Guselkumab improved outcomes in psoriatic arthritis patients regardless of past treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in the phase 3 DISCOVER-1 trial.

The anti-interleukin-23p19 monoclonal antibody is approved in the United States for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (PsO).

Benefits in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) were seen in both biologic-naive and tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi)–treated patients and occurred with both 4- and 8-week dosing regimens, Atul Deodhar, MD, reported during a plenary session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

For example, the primary endpoint of ACR 20 response at 24 weeks was achieved in 58.6% and 52.8% of patients randomized to receive 100 mg of guselkumab delivered subcutaneously either at baseline and every 4 weeks or at baseline, week 4, and then every 8 weeks, respectively, compared with 22.2% of those randomized to receive placebo, said Dr. Deodhar, professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

Greater proportions of patients in the guselkumab groups achieved ACR 20 response at week 16; ACR 50 response at weeks 16 and 24; ACR 70 response at week 24; Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 75, 90, and 100 responses at week 24; and minimal disease activity response at week 24, he said, adding that improvements were also seen with guselkumab versus placebo for the controlled major secondary endpoints of change from baseline in Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index score, Short Form 36 Health Survey score, and investigator global assessment (IGA) of PsO response.

The response rates with guselkumab versus placebo were seen regardless of prior TNFi use, he said.

The study included 381 patients with active PsA, defined as three or more swollen joints, three or more tender joints, and C-reactive protein of 0.3 mg/dL or greater despite standard therapies. About 30% were exposed to up to two TNFi therapies and 10% were nonresponders or inadequate responders to those therapies.

Concomitant use of select nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, oral corticosteroids, and NSAIDs was allowed, and patients with less than 5% improvement in tender plus swollen joints at week 16 could initiate or increase the dose of the permitted medications while continuing study treatment, Dr. Deodhar said.

The mean body surface area with PsO involvement was 13.4%; 42.5% of patients had an IGA of 3-4 for skin involvement. Mean swollen and tender joint counts were 9.8 and 19.3, respectively, indicating a population with moderate to severe disease, he added.

Serious adverse events, serious infections, and death occurred in 2.4%, 0.5%, and 0.3% of patients, respectively.

“Both guselkumab regimens were safe and well tolerated through week 24,” Dr. Deodhar said, noting that the safety profile was consistent with that established in the treatment of PsO and described in the label.

DISCOVER-1 was funded by Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Deodhar reported relationships (advisory board activity, consulting, and/or research grant funding) with several pharmaceutical companies including Janssen. Several coauthors are employees of Janssen.

SOURCE: Deodhar A et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 807.

A New Valve—and a Change of Heart?

ANSWER

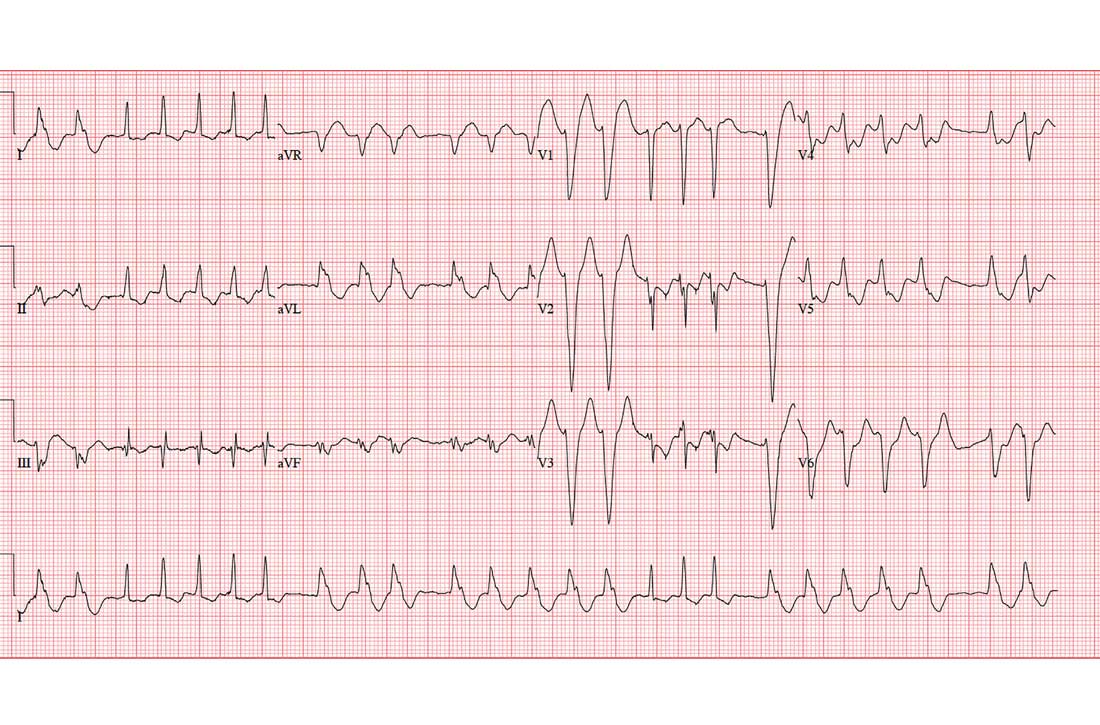

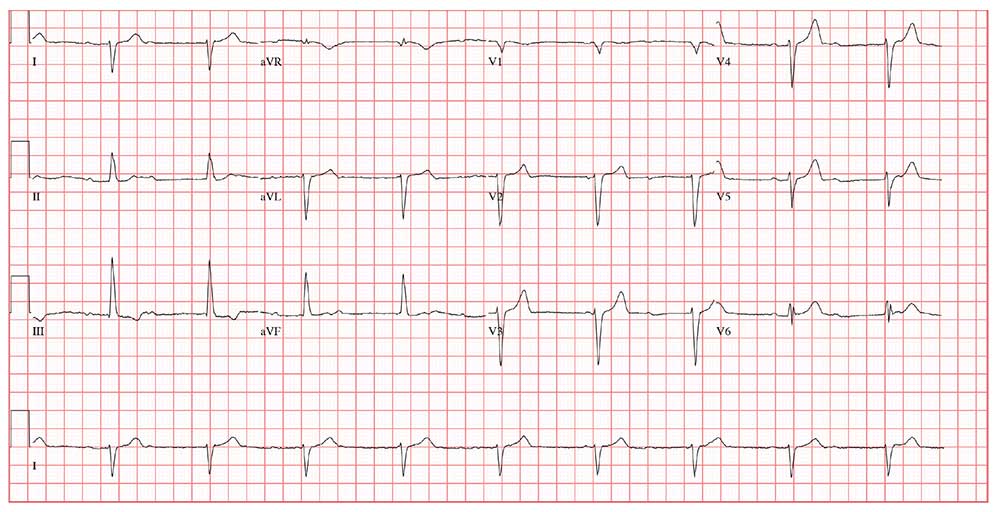

This ECG shows sinus rhythm with complete heart block and a junctional rhythm with a right-axis deviation. Additionally, ventricular depolarization in the precordial leads is suggestive of an anterior myocardial infarction.

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the regular, steady progression of P waves with a P-P interval of about 90 beats/min. Complete atrioventricular dissociation indicates complete heart block.

A normal QRS duration of 106 ms at a rate of 56 beats/min supports the diagnosis of a junctional escape rhythm. Right-axis deviation is evidenced by an R axis of 120°.

Finally, poor R-wave progression with deep S waves in leads V1 through V5 is suggestive of an anterior myocardial infarction. However, in this case, there is no evidence of ischemia or history of infarction—so these are thought to be early postoperative findings.

ANSWER

This ECG shows sinus rhythm with complete heart block and a junctional rhythm with a right-axis deviation. Additionally, ventricular depolarization in the precordial leads is suggestive of an anterior myocardial infarction.

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the regular, steady progression of P waves with a P-P interval of about 90 beats/min. Complete atrioventricular dissociation indicates complete heart block.

A normal QRS duration of 106 ms at a rate of 56 beats/min supports the diagnosis of a junctional escape rhythm. Right-axis deviation is evidenced by an R axis of 120°.

Finally, poor R-wave progression with deep S waves in leads V1 through V5 is suggestive of an anterior myocardial infarction. However, in this case, there is no evidence of ischemia or history of infarction—so these are thought to be early postoperative findings.

ANSWER

This ECG shows sinus rhythm with complete heart block and a junctional rhythm with a right-axis deviation. Additionally, ventricular depolarization in the precordial leads is suggestive of an anterior myocardial infarction.

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the regular, steady progression of P waves with a P-P interval of about 90 beats/min. Complete atrioventricular dissociation indicates complete heart block.

A normal QRS duration of 106 ms at a rate of 56 beats/min supports the diagnosis of a junctional escape rhythm. Right-axis deviation is evidenced by an R axis of 120°.

Finally, poor R-wave progression with deep S waves in leads V1 through V5 is suggestive of an anterior myocardial infarction. However, in this case, there is no evidence of ischemia or history of infarction—so these are thought to be early postoperative findings.

Three days ago, a 64-year-old man underwent a tricuspid valve replacement for severe tricuspid regurgitation of unknown etiology. The surgical procedure included implantation of a 29-mm porcine valve and 2 epicardial right ventricular epicardial pacing leads.

The patient’s preoperative echocardiogram had shown severe tricuspid regurgitation with anterior leaflet prolapse and severe right atrial and ventricular enlargement. Preoperatively, the peak velocity of the tricuspid valve was 3.4 m/s, and the right ventricular systolic pressure was measured at 55 mm Hg. There was no mitral valvular disease or evidence of ischemia, and the overall left ventricular function was preserved, with a normal ejection fraction.

Preoperative history included 3-year progression of shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, and bilateral lower extremity edema. Over the past 2 months, he has had signs of hepatic congestion, including elevated serum transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, and direct bilirubin levels. A physical exam had revealed an enlarged liver that was tender to deep palpation. Social and family histories are noncontributory to the case as presented.

This morning, the patient is in no distress, sitting comfortably in a chair, and is alert and cooperative. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 118/64 mm Hg; pulse, 60 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; and temperature, 96.4°F.

The surgical incision is clean, dry, and well approximated, and the patient is back to his preoperative weight. Pulmonary exam reveals clear breath sounds, with the exception of the left base, which demonstrates crackles that change with coughing. There are no wheezes. The cardiac exam reveals a regular rhythm at a rate of 60 beats/min, with a soft grade II/VI systolic murmur at the left lower sternal border. A late systolic friction rub is also evident. The abdomen is soft and nontender, with good bowel sounds and no organomegaly. Peripheral pulses are strong bilaterally, and there is trace pitting edema in both lower extremities. Neurologic exam is normal.

This morning’s ECG reveals a ventricular rate of 56 beats/min; PR interval, unmeasurable; QRS duration, 106 ms; QT/QTc interval, 400/386 ms; P axis, 36°; R axis, 120°; and T axis, 7°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Yellow-Brown Ulcerated Papule in a Newborn

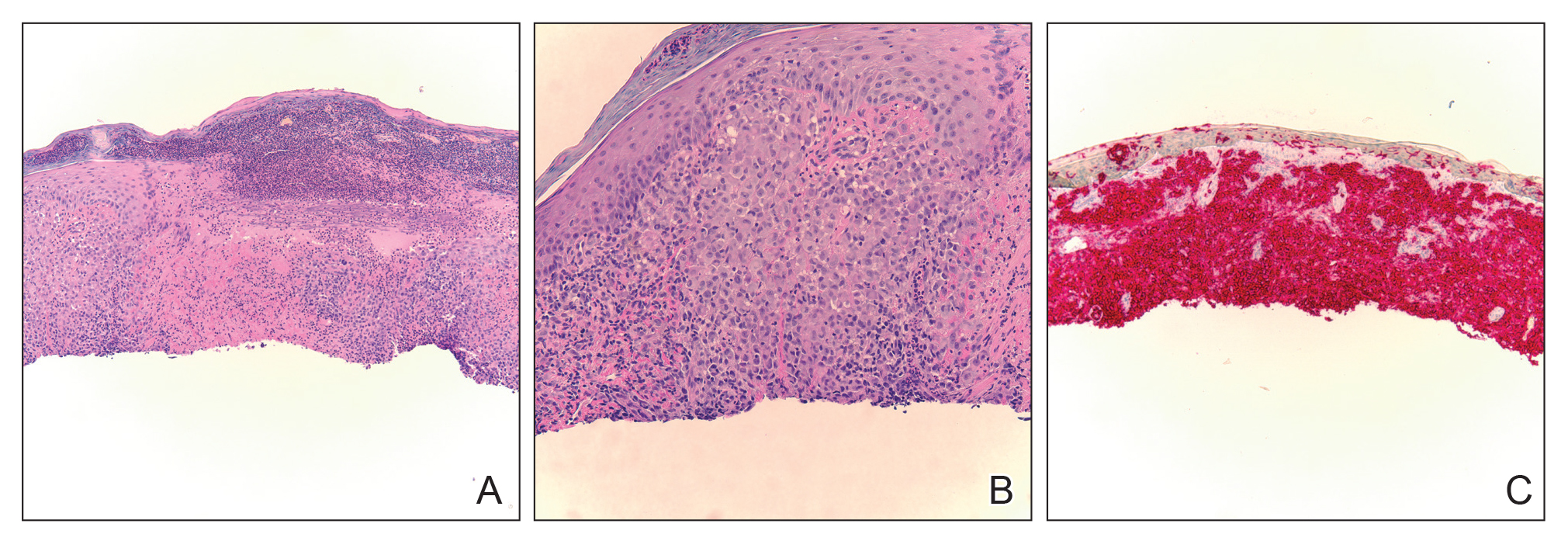

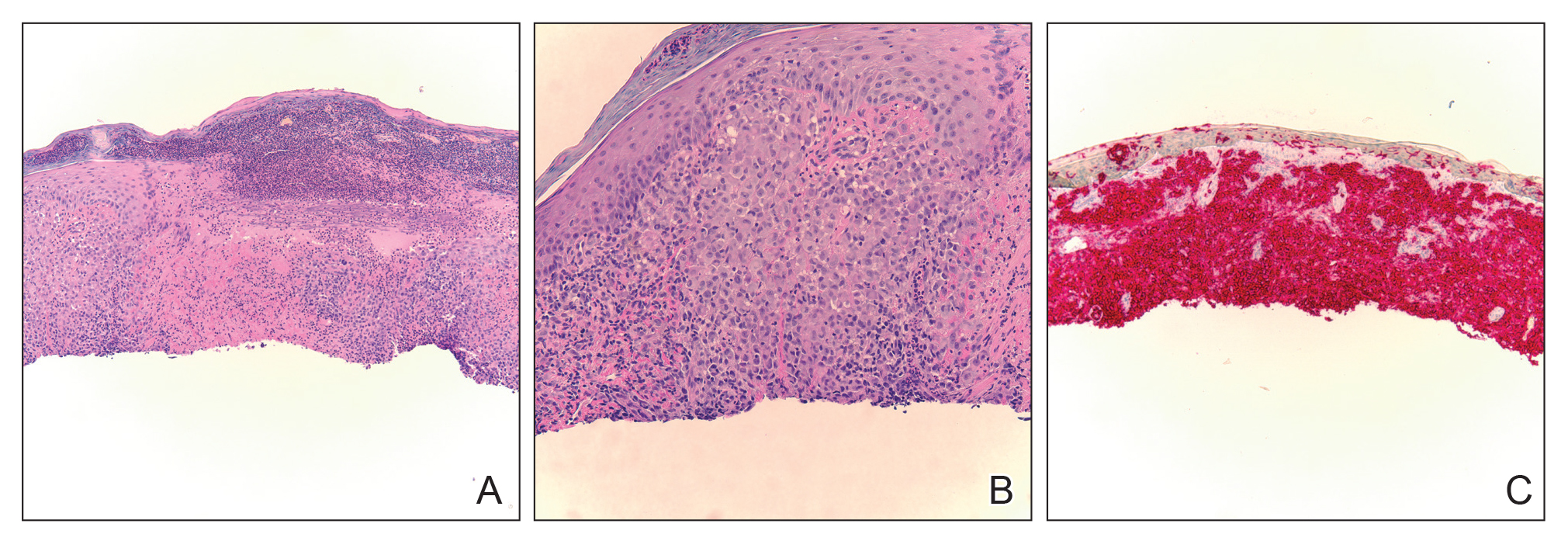

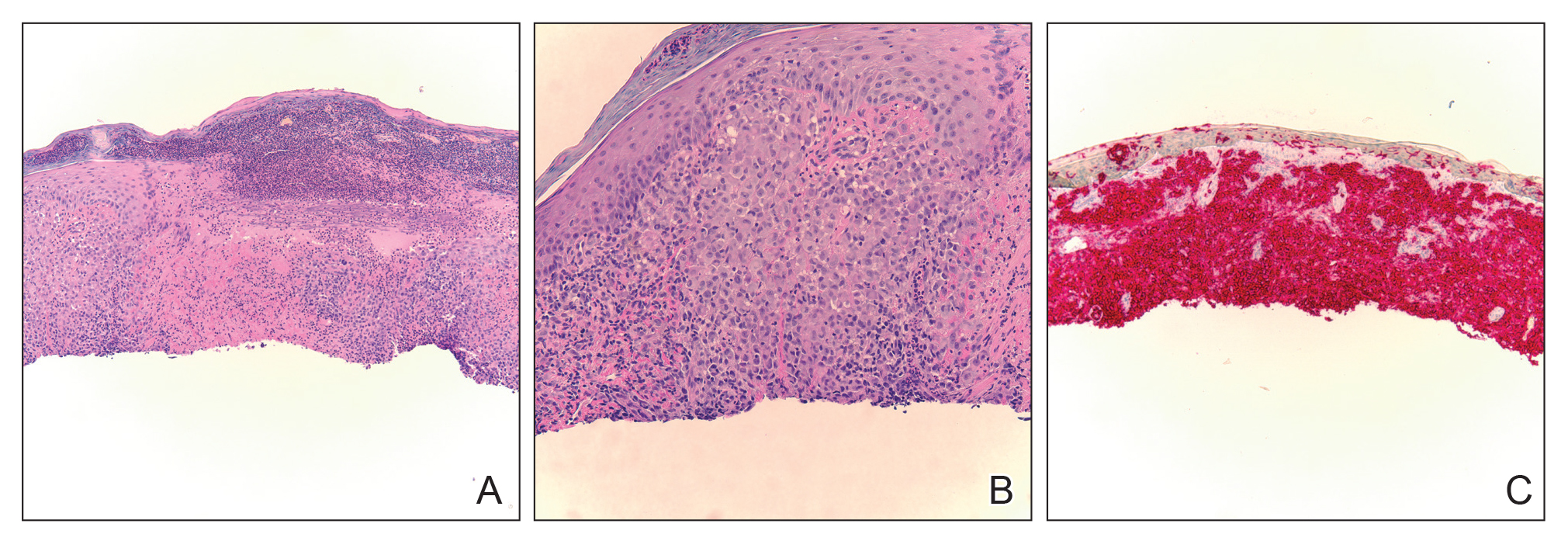

The Diagnosis: Congenital Self-healing Reticulohistiocytosis

Biopsy of a representative lesion from this patient was consistent with congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, as shown in the Figure. Characteristic Langerhans cells were present in the dermis that stained CD1a positive, S-100 positive, and CD68 negative to confirm the diagnosis.

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, or Hashimoto-Pritzker syndrome, is a rare benign form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It is twice as common in males than females and typically noted at birth or early during the neonatal period. Lesions may present as pink, firm, asymptomatic papulonodular lesions that often ulcerate with possible residual hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation.1 The differential diagnosis includes congenital infectious and hematologic diseases typically associated with blueberry muffin baby. Thus, varicella, cytomegalovirus, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, neuroblastoma, leukemia cutis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis, among others, may be considered. Juvenile xanthogranuloma or urticaria pigmentosa also enter the differential diagnosis given the yellow-brown appearance. As a clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells, pathology reveals lesions that stain positive for CD1a and S-100.2

Although typically absent, evaluation for systemic involvement is warranted, which may be an early presentation of multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Continued monitoring is recommended given the risk of relapse and associated mortality. Our patient continues to do well. He will continue to be followed by our team and hematology/oncology during early childhood.

The treatment of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis may include conservative monitoring, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, tacrolimus, or psoralen plus UVA.3 Surgical excision may be considered for large lesions.

- Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555.

- Chen AJ, Jarrett P, Macfarlane S. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: the need for investigation. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:76-77.

- Gothwal S, Gupta AK, Choudhary R. Congenital self healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:316-317.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Self-healing Reticulohistiocytosis

Biopsy of a representative lesion from this patient was consistent with congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, as shown in the Figure. Characteristic Langerhans cells were present in the dermis that stained CD1a positive, S-100 positive, and CD68 negative to confirm the diagnosis.

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, or Hashimoto-Pritzker syndrome, is a rare benign form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It is twice as common in males than females and typically noted at birth or early during the neonatal period. Lesions may present as pink, firm, asymptomatic papulonodular lesions that often ulcerate with possible residual hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation.1 The differential diagnosis includes congenital infectious and hematologic diseases typically associated with blueberry muffin baby. Thus, varicella, cytomegalovirus, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, neuroblastoma, leukemia cutis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis, among others, may be considered. Juvenile xanthogranuloma or urticaria pigmentosa also enter the differential diagnosis given the yellow-brown appearance. As a clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells, pathology reveals lesions that stain positive for CD1a and S-100.2

Although typically absent, evaluation for systemic involvement is warranted, which may be an early presentation of multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Continued monitoring is recommended given the risk of relapse and associated mortality. Our patient continues to do well. He will continue to be followed by our team and hematology/oncology during early childhood.

The treatment of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis may include conservative monitoring, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, tacrolimus, or psoralen plus UVA.3 Surgical excision may be considered for large lesions.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Self-healing Reticulohistiocytosis

Biopsy of a representative lesion from this patient was consistent with congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, as shown in the Figure. Characteristic Langerhans cells were present in the dermis that stained CD1a positive, S-100 positive, and CD68 negative to confirm the diagnosis.

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, or Hashimoto-Pritzker syndrome, is a rare benign form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It is twice as common in males than females and typically noted at birth or early during the neonatal period. Lesions may present as pink, firm, asymptomatic papulonodular lesions that often ulcerate with possible residual hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation.1 The differential diagnosis includes congenital infectious and hematologic diseases typically associated with blueberry muffin baby. Thus, varicella, cytomegalovirus, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, neuroblastoma, leukemia cutis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis, among others, may be considered. Juvenile xanthogranuloma or urticaria pigmentosa also enter the differential diagnosis given the yellow-brown appearance. As a clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells, pathology reveals lesions that stain positive for CD1a and S-100.2

Although typically absent, evaluation for systemic involvement is warranted, which may be an early presentation of multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Continued monitoring is recommended given the risk of relapse and associated mortality. Our patient continues to do well. He will continue to be followed by our team and hematology/oncology during early childhood.

The treatment of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis may include conservative monitoring, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, tacrolimus, or psoralen plus UVA.3 Surgical excision may be considered for large lesions.

- Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555.

- Chen AJ, Jarrett P, Macfarlane S. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: the need for investigation. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:76-77.

- Gothwal S, Gupta AK, Choudhary R. Congenital self healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:316-317.

- Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555.

- Chen AJ, Jarrett P, Macfarlane S. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: the need for investigation. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:76-77.

- Gothwal S, Gupta AK, Choudhary R. Congenital self healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:316-317.

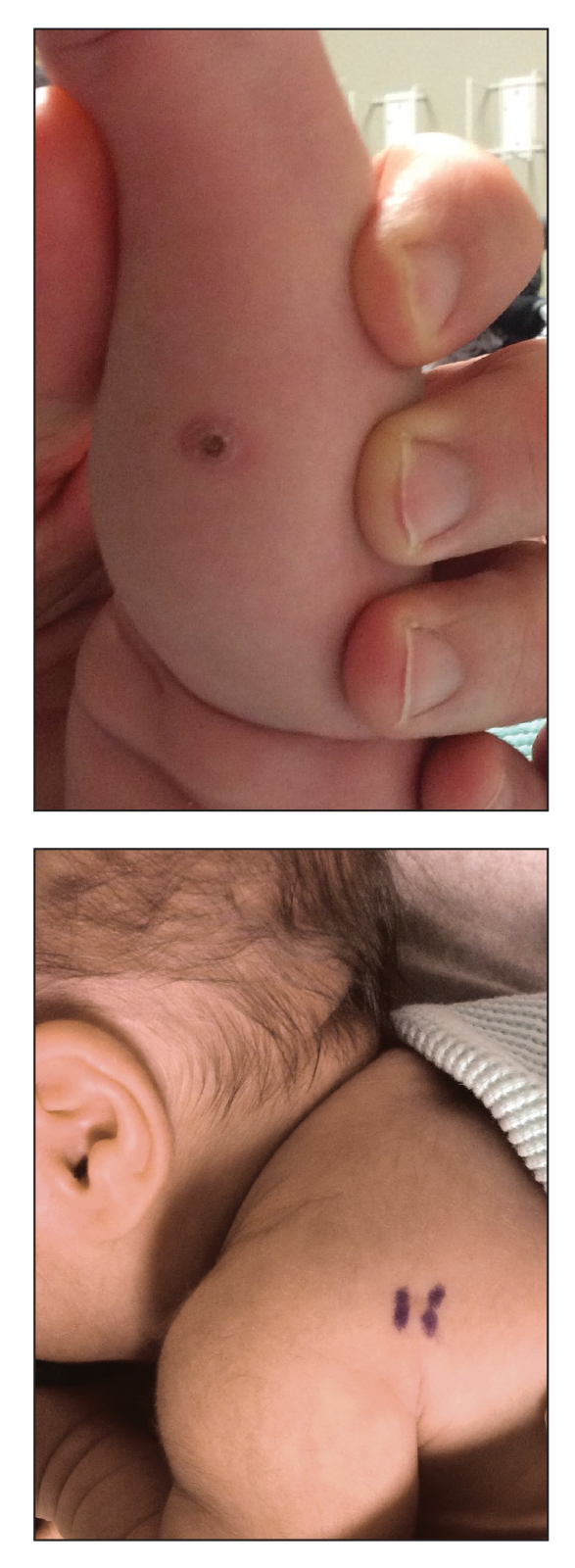

An 18-day-old infant boy presented with yellow-brown ulcerated papules on the left posterior leg (top) and left posterior shoulder (bottom). He was born via spontaneous vaginal delivery at 33 1/7 weeks' gestation complicated by preeclampsia. The lesions were unchanged during the infant's stay in the neonatal intensive care unit. However, his mother noted that one lesion crusted once home without an increase in size. His fraternal twin sister did not have any similar lesions. Jaundice and hepatosplenomegaly were absent. He was referred to hematology/oncology. A complete blood cell count revealed nonconcerning slight anemia. Liver function tests, coagulation studies, a chest radiograph, and a skeletal survey were ordered.

Patients taking TNF inhibitors can safely receive Zostavax

ATLANTA – A group of patients using a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor safely received the live-attenuated varicella vaccine Zostavax without any cases of herpes zoster in the first 6 weeks after vaccination in the blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled Varicella Zoster Vaccine (VERVE) trial .

According to guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, there is a theoretical concern that patients using a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) and other biologic therapies who receive a live-attenuated version of the varicella vaccine (Zostavax) could become infected with varicella from the vaccine. Patients with RA and psoriatic arthritis as well as other autoimmune and inflammatory conditions who are likely to receive TNFi therapy are also at risk for herpes zoster reactivation, Jeffrey Curtis, MD, professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in his presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. There also exists a risk for patients receiving low-dose glucocorticoids.

“The challenge, of course, is there’s not a great definition and there certainly is not a well-standardized assay for how immunocompromised someone is, and so that led to the uncertainty in this patient population for this and other live-virus vaccines,” Dr. Curtis said.

Dr. Curtis and colleagues enrolled 627 participants from 33 centers into the VERVE trial. Participants were aged at least 50 years, were taking a TNFi, and had not previously received Zostavax.

Patients in both groups had a mean age of about 63 years and about two-thirds were women. The most common indications for TNFi use in the Zostavax group and the placebo group were RA (59.2% vs. 56.0%, respectively), psoriatic arthritis (24.3% vs. 23.9%), and ankylosing spondylitis (7.2% vs. 8.5%), while the anti-TNF agents used were adalimumab (38.1% vs. 27.4%), infliximab (28.4% vs. 34.2%), etanercept (19.0% vs. 23.5%), golimumab (10.0% vs. 8.1%), and certolizumab pegol (4.5% vs. 6.8%). In addition, some patients in the Zostavax and placebo groups were also taking concomitant therapies with TNFi, such as oral glucocorticoids (9.7% vs. 11.4%).

The researchers randomized participants to receive Zostavax or placebo (saline) and then followed them for 6 weeks, and looked for signs of wild-type or vaccine-strain varicella infection. If participants were suspected to have varicella, they were assessed clinically, underwent polymerase chain reaction testing, and rashes were photographed. At baseline and at 6 weeks, the researchers collected serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells to determine patient immunity to varicella. After 6 months, participants were unmasked to the treatment arm of the study.

Dr. Curtis and colleagues found no confirmed varicella infection cases at 6 weeks. “To the extent that 0 cases out of 317 vaccinated people is reassuring, there were no cases, so that was exceedingly heartening as a result,” he said.

Out of 20 serious adverse events total in the groups, 15 events occurred before 6 months, including 8 suspected varicella cases in the Zostavax group and 7 in the placebo group. However, there were no positive cases of varicella – either wild type or vaccine type – after polymerase chain reaction tests. Overall, there were 268 adverse events in 195 participants, with 73 events (27.2%) consisting of injection-site reactions. The researchers also found no difference in the rate of disease flares, and found no differences in adverse reactions between groups, apart from a higher rate of injection-site reactions in the varicella group (19.4% vs. 4.2%).

With regard to immunogenicity, the humoral immune response was measured through IgG, which showed an immune response in the varicella group at 6 weeks (geometric mean fold ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.18-1.51), compared with the placebo group (GMFR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.91-1.14); cell-mediated immune response was measured by interferon-gamma, which also showed an immune response in the live-vaccine group (GMFR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.14-1.94), compared with participants who received placebo (GMFR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.87-1.48). In preliminary 1-year data, IgG immune response was elevated in the varicella group (GMFR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.08-1.99), but there was no elevated immune response for interferon-gamma (GMFR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.49-1.25).

“I think the trial is encouraging not only for its result with the live zoster vaccine and TNF-treated patients, but also challenge the notion that, if you need to, a live-virus vaccine may in fact be able to be safely given to people with autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, even those treated with biologics like tumor necrosis factor inhibitors,” Dr. Curtis said.

As patients in VERVE consented to long-term follow-up in health plan claims and EHR data, it will be possible to follow these patients in the future to assess herpes zoster reactivation. Dr. Curtis also noted that a new trial involving the recombinant, adjuvanted zoster vaccine (Shingrix) is currently in development and should begin next year.

The VERVE trial was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Curtis reported serving as a current member of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Herpes Zoster Work Group. He and some of the other authors reported financial relationships with many pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Curtis J et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 824.

ATLANTA – A group of patients using a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor safely received the live-attenuated varicella vaccine Zostavax without any cases of herpes zoster in the first 6 weeks after vaccination in the blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled Varicella Zoster Vaccine (VERVE) trial .

According to guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, there is a theoretical concern that patients using a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) and other biologic therapies who receive a live-attenuated version of the varicella vaccine (Zostavax) could become infected with varicella from the vaccine. Patients with RA and psoriatic arthritis as well as other autoimmune and inflammatory conditions who are likely to receive TNFi therapy are also at risk for herpes zoster reactivation, Jeffrey Curtis, MD, professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in his presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. There also exists a risk for patients receiving low-dose glucocorticoids.

“The challenge, of course, is there’s not a great definition and there certainly is not a well-standardized assay for how immunocompromised someone is, and so that led to the uncertainty in this patient population for this and other live-virus vaccines,” Dr. Curtis said.

Dr. Curtis and colleagues enrolled 627 participants from 33 centers into the VERVE trial. Participants were aged at least 50 years, were taking a TNFi, and had not previously received Zostavax.

Patients in both groups had a mean age of about 63 years and about two-thirds were women. The most common indications for TNFi use in the Zostavax group and the placebo group were RA (59.2% vs. 56.0%, respectively), psoriatic arthritis (24.3% vs. 23.9%), and ankylosing spondylitis (7.2% vs. 8.5%), while the anti-TNF agents used were adalimumab (38.1% vs. 27.4%), infliximab (28.4% vs. 34.2%), etanercept (19.0% vs. 23.5%), golimumab (10.0% vs. 8.1%), and certolizumab pegol (4.5% vs. 6.8%). In addition, some patients in the Zostavax and placebo groups were also taking concomitant therapies with TNFi, such as oral glucocorticoids (9.7% vs. 11.4%).

The researchers randomized participants to receive Zostavax or placebo (saline) and then followed them for 6 weeks, and looked for signs of wild-type or vaccine-strain varicella infection. If participants were suspected to have varicella, they were assessed clinically, underwent polymerase chain reaction testing, and rashes were photographed. At baseline and at 6 weeks, the researchers collected serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells to determine patient immunity to varicella. After 6 months, participants were unmasked to the treatment arm of the study.

Dr. Curtis and colleagues found no confirmed varicella infection cases at 6 weeks. “To the extent that 0 cases out of 317 vaccinated people is reassuring, there were no cases, so that was exceedingly heartening as a result,” he said.