User login

Check all components in cases of suspected shoe allergy

according to a retrospective study of more than 30,000 patients.

Contact allergy to shoes remains a common but difficult problem for many reasons, including the limited information from shoe manufacturers, differences in shoe manufacturing processes, and changes in shoe trends, said Raina Bembry, MD, a dermatitis research fellow at Duke University, Durham, N.C., in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Contact Dermatitis Society.

The North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) published data on shoe allergens from 2001-2004 in a 2007 review. To update this information to reflect changes in shoe manufacturing and trends, she and her coinvestigators characterized demographics, clinical characteristics, patch test results, and occupational data for NACDG patients with shoe contact allergy. They identified 33,661 patients who were patch tested with the standard series with or without a supplemental allergen between 2005 and 2018; over half were over aged 40.

The primary focus was individuals with a confirmed shoe (defined as shoes, boots, sandals, or slippers) as the source of a screening allergen or supplemental allergen, a positive patch test, and the foot as one of three sites of involvement. A total of 352 individuals met these criteria and had a confirmed final diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, Dr. Bembry said. Compared with individuals who had positive patch tests without a confirmed diagnosis, those with confirmed allergic dermatitis were significantly more likely to be male (odds ratio, 3.36) and less likely to be over aged 40 years (OR, 0.49).

The most common NACDG screening allergen, potassium dichromate, was found in 29.8% of the study population, followed by p-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin in 20.1%, thiuram mix (13.3%), mixed dialkyl thioureas (12.6%) and carba mix (12%).

Notably, 29.8% of the patients showed positive patch test reactions to supplemental allergens, and 12.2% only reacted to supplemental allergens, Dr. Bembry said.

The results were limited by several factors, including referral selection bias, reliance on clinical judgment for patch test interpretations, and lack of data on the specifics of the supplemental allergens other than the source code, she said. In addition, the study does not identify nonshoe sources of foot contact allergy, and six screening allergens were not testing during this study period.

Overall, the findings were similar to those from previous studies in that patients affected with contact dermatitis from shoe allergens tended to be younger and male, with no occupational relevance to the reaction, said Dr. Bembry.

The finding that almost 20% of allergens were not found with the screening series emphasizes the value of testing not only relevant supplemental allergens, but also patient products and shoe components, she concluded.

Dr. Bembry had no financial conflicts to disclose. Coauthor Amber Atwater, MD, the immediate past president of the ACDS, and associate professor of dermatology at Duke University, disclosed receiving the Pfizer Independent Grant for Learning & Change and consulting for Henkel.

according to a retrospective study of more than 30,000 patients.

Contact allergy to shoes remains a common but difficult problem for many reasons, including the limited information from shoe manufacturers, differences in shoe manufacturing processes, and changes in shoe trends, said Raina Bembry, MD, a dermatitis research fellow at Duke University, Durham, N.C., in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Contact Dermatitis Society.

The North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) published data on shoe allergens from 2001-2004 in a 2007 review. To update this information to reflect changes in shoe manufacturing and trends, she and her coinvestigators characterized demographics, clinical characteristics, patch test results, and occupational data for NACDG patients with shoe contact allergy. They identified 33,661 patients who were patch tested with the standard series with or without a supplemental allergen between 2005 and 2018; over half were over aged 40.

The primary focus was individuals with a confirmed shoe (defined as shoes, boots, sandals, or slippers) as the source of a screening allergen or supplemental allergen, a positive patch test, and the foot as one of three sites of involvement. A total of 352 individuals met these criteria and had a confirmed final diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, Dr. Bembry said. Compared with individuals who had positive patch tests without a confirmed diagnosis, those with confirmed allergic dermatitis were significantly more likely to be male (odds ratio, 3.36) and less likely to be over aged 40 years (OR, 0.49).

The most common NACDG screening allergen, potassium dichromate, was found in 29.8% of the study population, followed by p-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin in 20.1%, thiuram mix (13.3%), mixed dialkyl thioureas (12.6%) and carba mix (12%).

Notably, 29.8% of the patients showed positive patch test reactions to supplemental allergens, and 12.2% only reacted to supplemental allergens, Dr. Bembry said.

The results were limited by several factors, including referral selection bias, reliance on clinical judgment for patch test interpretations, and lack of data on the specifics of the supplemental allergens other than the source code, she said. In addition, the study does not identify nonshoe sources of foot contact allergy, and six screening allergens were not testing during this study period.

Overall, the findings were similar to those from previous studies in that patients affected with contact dermatitis from shoe allergens tended to be younger and male, with no occupational relevance to the reaction, said Dr. Bembry.

The finding that almost 20% of allergens were not found with the screening series emphasizes the value of testing not only relevant supplemental allergens, but also patient products and shoe components, she concluded.

Dr. Bembry had no financial conflicts to disclose. Coauthor Amber Atwater, MD, the immediate past president of the ACDS, and associate professor of dermatology at Duke University, disclosed receiving the Pfizer Independent Grant for Learning & Change and consulting for Henkel.

according to a retrospective study of more than 30,000 patients.

Contact allergy to shoes remains a common but difficult problem for many reasons, including the limited information from shoe manufacturers, differences in shoe manufacturing processes, and changes in shoe trends, said Raina Bembry, MD, a dermatitis research fellow at Duke University, Durham, N.C., in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Contact Dermatitis Society.

The North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) published data on shoe allergens from 2001-2004 in a 2007 review. To update this information to reflect changes in shoe manufacturing and trends, she and her coinvestigators characterized demographics, clinical characteristics, patch test results, and occupational data for NACDG patients with shoe contact allergy. They identified 33,661 patients who were patch tested with the standard series with or without a supplemental allergen between 2005 and 2018; over half were over aged 40.

The primary focus was individuals with a confirmed shoe (defined as shoes, boots, sandals, or slippers) as the source of a screening allergen or supplemental allergen, a positive patch test, and the foot as one of three sites of involvement. A total of 352 individuals met these criteria and had a confirmed final diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, Dr. Bembry said. Compared with individuals who had positive patch tests without a confirmed diagnosis, those with confirmed allergic dermatitis were significantly more likely to be male (odds ratio, 3.36) and less likely to be over aged 40 years (OR, 0.49).

The most common NACDG screening allergen, potassium dichromate, was found in 29.8% of the study population, followed by p-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin in 20.1%, thiuram mix (13.3%), mixed dialkyl thioureas (12.6%) and carba mix (12%).

Notably, 29.8% of the patients showed positive patch test reactions to supplemental allergens, and 12.2% only reacted to supplemental allergens, Dr. Bembry said.

The results were limited by several factors, including referral selection bias, reliance on clinical judgment for patch test interpretations, and lack of data on the specifics of the supplemental allergens other than the source code, she said. In addition, the study does not identify nonshoe sources of foot contact allergy, and six screening allergens were not testing during this study period.

Overall, the findings were similar to those from previous studies in that patients affected with contact dermatitis from shoe allergens tended to be younger and male, with no occupational relevance to the reaction, said Dr. Bembry.

The finding that almost 20% of allergens were not found with the screening series emphasizes the value of testing not only relevant supplemental allergens, but also patient products and shoe components, she concluded.

Dr. Bembry had no financial conflicts to disclose. Coauthor Amber Atwater, MD, the immediate past president of the ACDS, and associate professor of dermatology at Duke University, disclosed receiving the Pfizer Independent Grant for Learning & Change and consulting for Henkel.

FROM ACDS 2021

Febuxostat, allopurinol real-world cardiovascular risk appears equal

Febuxostat (Uloric) was not associated with increased cardiovascular risk in patients with gout when compared to those who used allopurinol, in an analysis of new users of the drugs in Medicare fee-for-service claims data from the period of 2008-2016.

The findings, published March 25 in the Journal of the American Heart Association, update and echo the results from a similar previous study by the same Brigham and Women’s Hospital research group that covered 2008-2013 Medicare claims data. That original claims data study from 2018 sought to confirm the findings of the postmarketing surveillance CARES (Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat and Allopurinol in Patients With Gout and Cardiovascular Morbidities) trial that led to a boxed warning for increased risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality vs. allopurinol. The trial, however, did not show a higher rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) overall with febuxostat.

The recency of the new data with more febuxostat-exposed patients overall provides greater reassurance on the safety of the drug, corresponding author Seoyoung C. Kim, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “We also were able to get data on cause of death, which we did not have before when we conducted our first paper.”

Dr. Kim said she was not surprised by any of the findings, which were consistent with the results of her earlier work. “Our result on CV death also was consistent and reassuring,” she noted.

The newest Medicare claims study also corroborates results from FAST (Febuxostat Versus Allopurinol Streamlined Trial), a separate postmarketing surveillance study that was ordered by the European Medicines Agency after febuxostat’s approval in 2009. It showed that the two drugs were noninferior to each other for the risk of all-cause mortality or a composite cardiovascular outcome (hospitalization for nonfatal myocardial infarction, biomarker-positive acute coronary syndrome, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death).

“While CARES showed higher CV death and all-cause death rates in febuxostat compared to allopurinol, FAST did not,” Dr. Kim noted. “Our study of more than 111,000 older gout patients treated with either febuxostat or allopurinol in real-world settings also did not find a difference in the risk of MACE, CV mortality, or all-cause mortality,” she added. “Taking these data all together, I think we can be more certain about the CV safety of febuxostat when its use is clinically indicated or needed,” she said.

Study details

Dr. Kim, first author Ajinkya Pawar, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s, and colleagues identified 467,461 people with gout aged 65 years and older who had been enrolled in Medicare for at least a year. They then used propensity-score matching to compare 27,881 first-time users of febuxostat with 83,643 first-time users of allopurinol on the primary outcome of the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as the first occurrence of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular mortality.

In the updated study, the mean follow‐up periods for febuxostat and allopurinol were 284 days and 339 days, respectively. Overall, febuxostat was noninferior to allopurinol with regard to MACE (hazard ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.05), and the results were consistent among patients with baseline CVD (HR, 0.94). In addition, rates of secondary outcomes of MI, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality were not significantly different between febuxostat and allopurinol patients, except for all-cause mortality (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.87-0.98).

The study findings were limited mainly by the potential bias caused by nonadherence to medications, and potential for residual confounding and misclassification bias, the researchers noted.

However, the study was strengthened by its incident new-user design that allowed only patients with no use of either medication for a year before the first dispensing and its active comparator design, and the data are generalizable to the greater population of older gout patients, they said.

Consequently, the data from this large, real-world study support the safety of febuxostat with regard to cardiovascular risk in gout patients, including those with baseline cardiovascular disease, they concluded.

The study was supported by the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Kim disclosed research grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Roche, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb for unrelated studies. Another author reported serving as the principal investigator with research grants from Vertex, Bayer, and Novartis to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for unrelated projects.

Febuxostat (Uloric) was not associated with increased cardiovascular risk in patients with gout when compared to those who used allopurinol, in an analysis of new users of the drugs in Medicare fee-for-service claims data from the period of 2008-2016.

The findings, published March 25 in the Journal of the American Heart Association, update and echo the results from a similar previous study by the same Brigham and Women’s Hospital research group that covered 2008-2013 Medicare claims data. That original claims data study from 2018 sought to confirm the findings of the postmarketing surveillance CARES (Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat and Allopurinol in Patients With Gout and Cardiovascular Morbidities) trial that led to a boxed warning for increased risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality vs. allopurinol. The trial, however, did not show a higher rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) overall with febuxostat.

The recency of the new data with more febuxostat-exposed patients overall provides greater reassurance on the safety of the drug, corresponding author Seoyoung C. Kim, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “We also were able to get data on cause of death, which we did not have before when we conducted our first paper.”

Dr. Kim said she was not surprised by any of the findings, which were consistent with the results of her earlier work. “Our result on CV death also was consistent and reassuring,” she noted.

The newest Medicare claims study also corroborates results from FAST (Febuxostat Versus Allopurinol Streamlined Trial), a separate postmarketing surveillance study that was ordered by the European Medicines Agency after febuxostat’s approval in 2009. It showed that the two drugs were noninferior to each other for the risk of all-cause mortality or a composite cardiovascular outcome (hospitalization for nonfatal myocardial infarction, biomarker-positive acute coronary syndrome, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death).

“While CARES showed higher CV death and all-cause death rates in febuxostat compared to allopurinol, FAST did not,” Dr. Kim noted. “Our study of more than 111,000 older gout patients treated with either febuxostat or allopurinol in real-world settings also did not find a difference in the risk of MACE, CV mortality, or all-cause mortality,” she added. “Taking these data all together, I think we can be more certain about the CV safety of febuxostat when its use is clinically indicated or needed,” she said.

Study details

Dr. Kim, first author Ajinkya Pawar, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s, and colleagues identified 467,461 people with gout aged 65 years and older who had been enrolled in Medicare for at least a year. They then used propensity-score matching to compare 27,881 first-time users of febuxostat with 83,643 first-time users of allopurinol on the primary outcome of the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as the first occurrence of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular mortality.

In the updated study, the mean follow‐up periods for febuxostat and allopurinol were 284 days and 339 days, respectively. Overall, febuxostat was noninferior to allopurinol with regard to MACE (hazard ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.05), and the results were consistent among patients with baseline CVD (HR, 0.94). In addition, rates of secondary outcomes of MI, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality were not significantly different between febuxostat and allopurinol patients, except for all-cause mortality (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.87-0.98).

The study findings were limited mainly by the potential bias caused by nonadherence to medications, and potential for residual confounding and misclassification bias, the researchers noted.

However, the study was strengthened by its incident new-user design that allowed only patients with no use of either medication for a year before the first dispensing and its active comparator design, and the data are generalizable to the greater population of older gout patients, they said.

Consequently, the data from this large, real-world study support the safety of febuxostat with regard to cardiovascular risk in gout patients, including those with baseline cardiovascular disease, they concluded.

The study was supported by the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Kim disclosed research grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Roche, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb for unrelated studies. Another author reported serving as the principal investigator with research grants from Vertex, Bayer, and Novartis to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for unrelated projects.

Febuxostat (Uloric) was not associated with increased cardiovascular risk in patients with gout when compared to those who used allopurinol, in an analysis of new users of the drugs in Medicare fee-for-service claims data from the period of 2008-2016.

The findings, published March 25 in the Journal of the American Heart Association, update and echo the results from a similar previous study by the same Brigham and Women’s Hospital research group that covered 2008-2013 Medicare claims data. That original claims data study from 2018 sought to confirm the findings of the postmarketing surveillance CARES (Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat and Allopurinol in Patients With Gout and Cardiovascular Morbidities) trial that led to a boxed warning for increased risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality vs. allopurinol. The trial, however, did not show a higher rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) overall with febuxostat.

The recency of the new data with more febuxostat-exposed patients overall provides greater reassurance on the safety of the drug, corresponding author Seoyoung C. Kim, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “We also were able to get data on cause of death, which we did not have before when we conducted our first paper.”

Dr. Kim said she was not surprised by any of the findings, which were consistent with the results of her earlier work. “Our result on CV death also was consistent and reassuring,” she noted.

The newest Medicare claims study also corroborates results from FAST (Febuxostat Versus Allopurinol Streamlined Trial), a separate postmarketing surveillance study that was ordered by the European Medicines Agency after febuxostat’s approval in 2009. It showed that the two drugs were noninferior to each other for the risk of all-cause mortality or a composite cardiovascular outcome (hospitalization for nonfatal myocardial infarction, biomarker-positive acute coronary syndrome, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death).

“While CARES showed higher CV death and all-cause death rates in febuxostat compared to allopurinol, FAST did not,” Dr. Kim noted. “Our study of more than 111,000 older gout patients treated with either febuxostat or allopurinol in real-world settings also did not find a difference in the risk of MACE, CV mortality, or all-cause mortality,” she added. “Taking these data all together, I think we can be more certain about the CV safety of febuxostat when its use is clinically indicated or needed,” she said.

Study details

Dr. Kim, first author Ajinkya Pawar, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s, and colleagues identified 467,461 people with gout aged 65 years and older who had been enrolled in Medicare for at least a year. They then used propensity-score matching to compare 27,881 first-time users of febuxostat with 83,643 first-time users of allopurinol on the primary outcome of the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as the first occurrence of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular mortality.

In the updated study, the mean follow‐up periods for febuxostat and allopurinol were 284 days and 339 days, respectively. Overall, febuxostat was noninferior to allopurinol with regard to MACE (hazard ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.05), and the results were consistent among patients with baseline CVD (HR, 0.94). In addition, rates of secondary outcomes of MI, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality were not significantly different between febuxostat and allopurinol patients, except for all-cause mortality (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.87-0.98).

The study findings were limited mainly by the potential bias caused by nonadherence to medications, and potential for residual confounding and misclassification bias, the researchers noted.

However, the study was strengthened by its incident new-user design that allowed only patients with no use of either medication for a year before the first dispensing and its active comparator design, and the data are generalizable to the greater population of older gout patients, they said.

Consequently, the data from this large, real-world study support the safety of febuxostat with regard to cardiovascular risk in gout patients, including those with baseline cardiovascular disease, they concluded.

The study was supported by the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Kim disclosed research grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Roche, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb for unrelated studies. Another author reported serving as the principal investigator with research grants from Vertex, Bayer, and Novartis to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for unrelated projects.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

FDA approves mirabegron to treat pediatric NDO

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for mirabegron (Myrbetriq/Myrbetriq Granules) to treat neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO), a bladder dysfunction related to neurologic impairment, in children aged 3 years and older.

This comes 1 year after the FDA approved solifenacin succinate, the first treatment of NDO in pediatric patients aged 2 years and older.

The approval of the drug for these new indications is a “positive step” for the treatment of NDO in young patients, Christine P. Nguyen, MD, director of the FDA’s Division of Urology, Obstetrics, and Gynecology, said in an FDA statement.

“Mirabegron, the active ingredient in Myrbetriq and Myrbetriq Granules, works by a different mechanism of action from the currently approved treatments, providing a new treatment option for these young patients. We remain committed to facilitating the development and approval of safe and effective therapies for pediatric NDO patients,” Dr. Nguyen said.

NDO is a bladder dysfunction that frequently occurs in patients with congenital conditions, such as spina bifida. It also occurs in people who suffer from other diseases or injuries of the nervous system, such as multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury. Symptoms of the condition include urinary frequency and incontinence.

The condition is characterized by the overactivity of the bladder wall muscle, which is normally relaxed to allow storage of urine. Irregular bladder muscle contraction increases storage pressure and decreases the amount of urine the bladder can hold. This can also put the upper urinary tract at risk for deterioration and cause permanent damage to the kidneys.

The effectiveness of Myrbetriq and Myrbetriq Granules for pediatric NDO was determined in a study of 86 children and adolescents aged 3-17 years. The researchers found that after 24 weeks of treatment, the drug improved the patients’ bladder capacity, reduced the number of bladder wall muscle contractions, and improved the volume of urine that could be held. It also reduced the daily number of episodes of leakage.

Side effects of Myrbetriq and Myrbetriq Granules include urinary tract infection, cold symptoms, angioedema, constipation, and headache. The FDA said the drug may also increase blood pressure and may worsen blood pressure in patients who have a history of hypertension.

The FDA approved mirabegron in 2012 to treat overactive bladder in adults.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for mirabegron (Myrbetriq/Myrbetriq Granules) to treat neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO), a bladder dysfunction related to neurologic impairment, in children aged 3 years and older.

This comes 1 year after the FDA approved solifenacin succinate, the first treatment of NDO in pediatric patients aged 2 years and older.

The approval of the drug for these new indications is a “positive step” for the treatment of NDO in young patients, Christine P. Nguyen, MD, director of the FDA’s Division of Urology, Obstetrics, and Gynecology, said in an FDA statement.

“Mirabegron, the active ingredient in Myrbetriq and Myrbetriq Granules, works by a different mechanism of action from the currently approved treatments, providing a new treatment option for these young patients. We remain committed to facilitating the development and approval of safe and effective therapies for pediatric NDO patients,” Dr. Nguyen said.

NDO is a bladder dysfunction that frequently occurs in patients with congenital conditions, such as spina bifida. It also occurs in people who suffer from other diseases or injuries of the nervous system, such as multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury. Symptoms of the condition include urinary frequency and incontinence.

The condition is characterized by the overactivity of the bladder wall muscle, which is normally relaxed to allow storage of urine. Irregular bladder muscle contraction increases storage pressure and decreases the amount of urine the bladder can hold. This can also put the upper urinary tract at risk for deterioration and cause permanent damage to the kidneys.

The effectiveness of Myrbetriq and Myrbetriq Granules for pediatric NDO was determined in a study of 86 children and adolescents aged 3-17 years. The researchers found that after 24 weeks of treatment, the drug improved the patients’ bladder capacity, reduced the number of bladder wall muscle contractions, and improved the volume of urine that could be held. It also reduced the daily number of episodes of leakage.

Side effects of Myrbetriq and Myrbetriq Granules include urinary tract infection, cold symptoms, angioedema, constipation, and headache. The FDA said the drug may also increase blood pressure and may worsen blood pressure in patients who have a history of hypertension.

The FDA approved mirabegron in 2012 to treat overactive bladder in adults.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication for mirabegron (Myrbetriq/Myrbetriq Granules) to treat neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO), a bladder dysfunction related to neurologic impairment, in children aged 3 years and older.

This comes 1 year after the FDA approved solifenacin succinate, the first treatment of NDO in pediatric patients aged 2 years and older.

The approval of the drug for these new indications is a “positive step” for the treatment of NDO in young patients, Christine P. Nguyen, MD, director of the FDA’s Division of Urology, Obstetrics, and Gynecology, said in an FDA statement.

“Mirabegron, the active ingredient in Myrbetriq and Myrbetriq Granules, works by a different mechanism of action from the currently approved treatments, providing a new treatment option for these young patients. We remain committed to facilitating the development and approval of safe and effective therapies for pediatric NDO patients,” Dr. Nguyen said.

NDO is a bladder dysfunction that frequently occurs in patients with congenital conditions, such as spina bifida. It also occurs in people who suffer from other diseases or injuries of the nervous system, such as multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury. Symptoms of the condition include urinary frequency and incontinence.

The condition is characterized by the overactivity of the bladder wall muscle, which is normally relaxed to allow storage of urine. Irregular bladder muscle contraction increases storage pressure and decreases the amount of urine the bladder can hold. This can also put the upper urinary tract at risk for deterioration and cause permanent damage to the kidneys.

The effectiveness of Myrbetriq and Myrbetriq Granules for pediatric NDO was determined in a study of 86 children and adolescents aged 3-17 years. The researchers found that after 24 weeks of treatment, the drug improved the patients’ bladder capacity, reduced the number of bladder wall muscle contractions, and improved the volume of urine that could be held. It also reduced the daily number of episodes of leakage.

Side effects of Myrbetriq and Myrbetriq Granules include urinary tract infection, cold symptoms, angioedema, constipation, and headache. The FDA said the drug may also increase blood pressure and may worsen blood pressure in patients who have a history of hypertension.

The FDA approved mirabegron in 2012 to treat overactive bladder in adults.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Asymptomatic Discolored Lesions on the Groin

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pigmentosus-Inversus

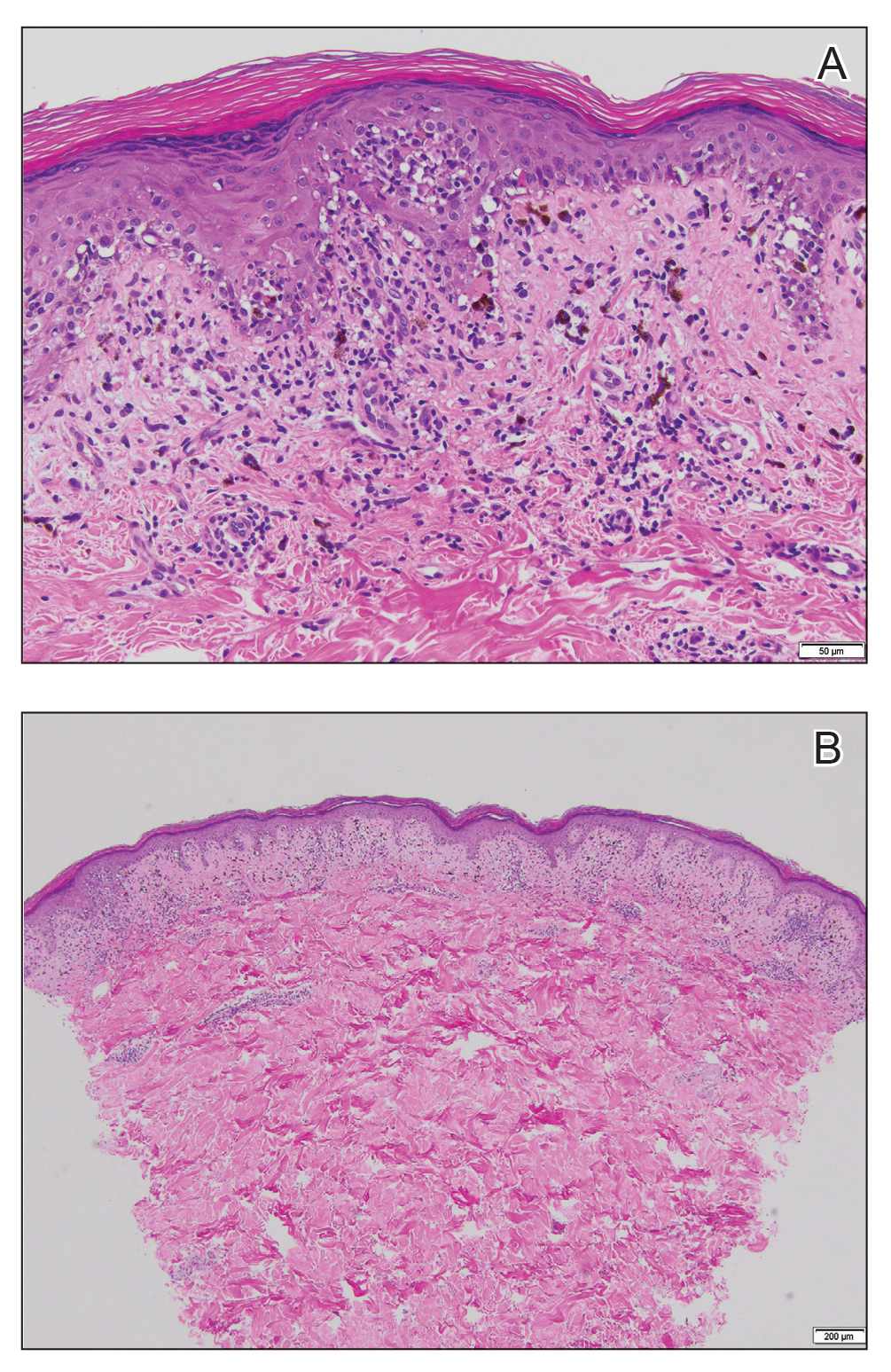

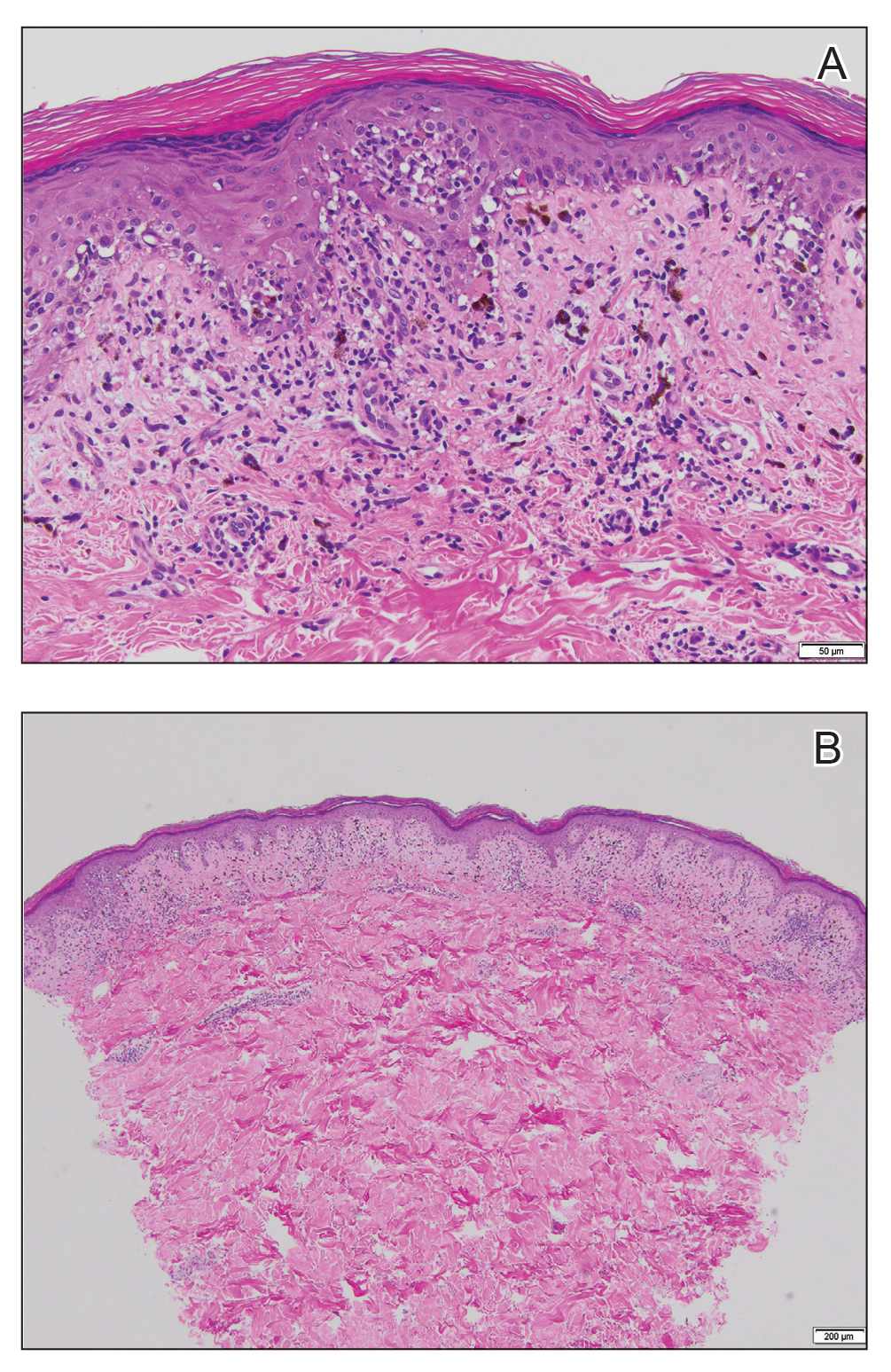

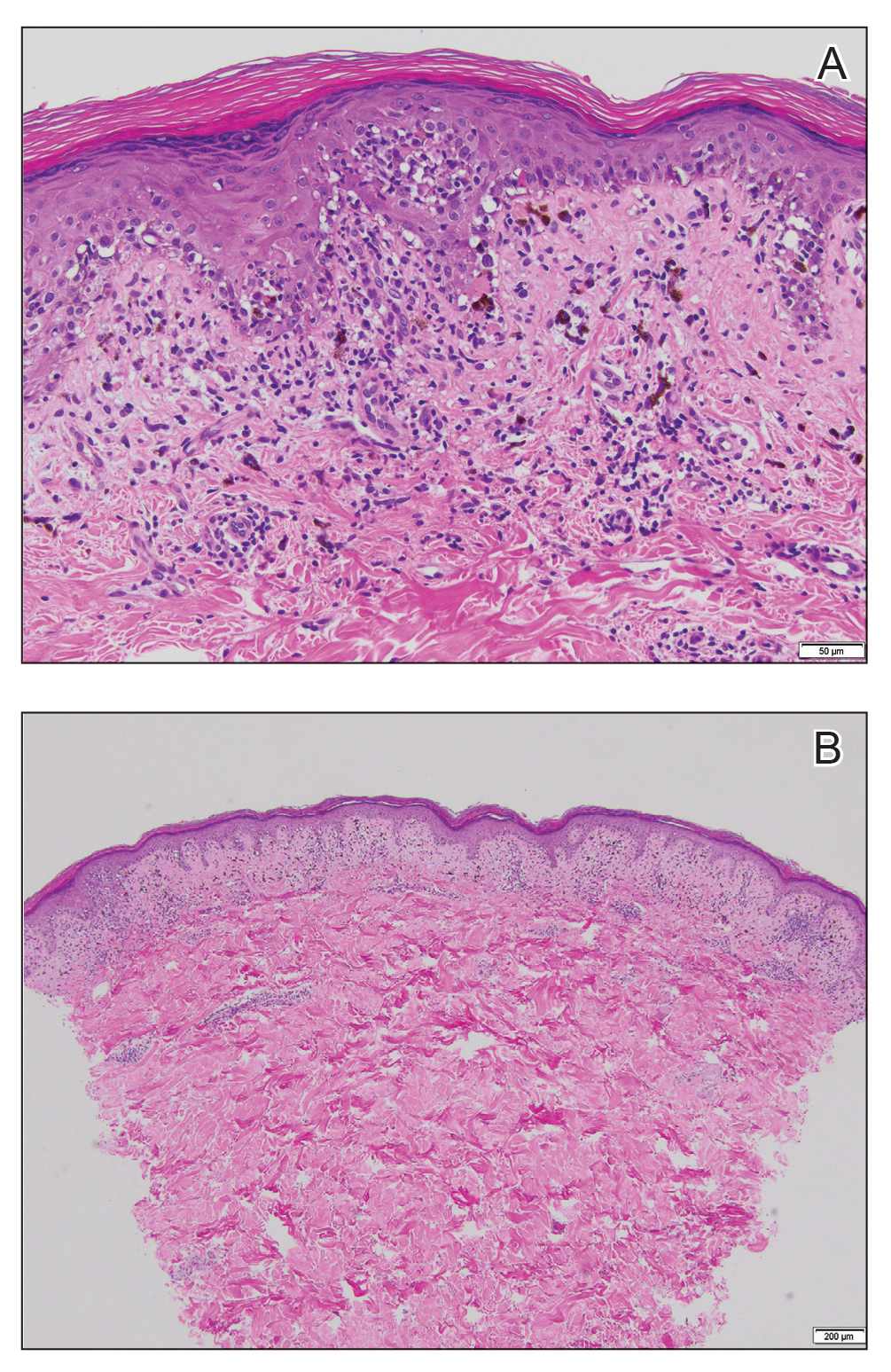

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis with dense, bandlike, lymphocytic inflammation at the dermoepidermal junction with associated melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The physical examination and histopathology were consistent with a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPPI). Treatment was discussed with the patient, with options including phototherapy, tacrolimus, or a high-dose steroid. Given that the lesions were asymptomatic and not bothersome, the patient denied treatment and agreed to routine follow-up.

The first case of LPPI was reported in 20011; since then, approximately 100 cases have been reported in the literature.2 A rare variant of lichen planus, LPPI predominantly occurs in middle-aged women.2,3 Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus is characterized by well-circumscribed, brown macules confined to non-sun-exposed intertriginous areas such as the axillae and groin.2 Although the rash remains localized, multiple lesions could arise in the same area, such as the groin as seen in our patient (Figure 2). Unlike in lichen planus, the oral mucosa, nails, and scalp are not affected. Furthermore, pruritus typically is absent in most cases of LPPI.2,4 Histopathologic findings include an atrophic epidermis with lichenoid infiltrates of lymphocytes and histocytes as well as substantial pigmentary incontinence with melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis.4,5

Given the gender, age, and clinical features of our patient, this case represents a classic scenario of LPPI. It currently is unknown if ethnicity plays a role in the disorder. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus initially was thought to be more prevalent in White patients; however, studies have been reported in individuals with darker skin.1,2

The main differential diagnosis includes erythema dyschromicum perstans, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and lichen planus. Although erythema dyschromicum perstans develops in individuals with darker skin, lesions are restricted to the upper torso and limbs.2-4 In both lichen planus and lichen actinicus, skin findings primarily develop in sun-exposed areas, such as the face, neck, and hands.4,6 Given the negative history of trauma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was unlikely in our patient. Furthermore, a distinguishing characteristic of LPPI is the deposition of melanin deep within the dermal layer.3

Lesions developing in nonexposed intertriginous skin makes LPPI unique and distinguishes it from other more common conditions. The lesions commonly are hyperpigmented and are not as pruritic as other lichen-associated conditions. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus often persists for months, and the rash generally is resistant to treatment.2,5 Topical tacrolimus and high-dose steroids may improve symptoms, though results have varied substantially. In addition, some cases have resolved spontaneously.1,4,6,7 Because LPPI is asymptomatic and benign, spontaneous resolution and routine care is a reasonable treatment strategy. Some cases have supported this strategy as safe and high-value care.2

- Mohamed M, Korbi M, Hammedi F, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus: a series of 10 Tunisian patients. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1088-1091.

- Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a rare variant of lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(suppl 1):AB239. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.959

- Chen S, Sun W, Zhou G, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: report of three Chinese cases and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2015;42:77-80.

- Tabanlıoǧlu-Onan D, Íncel-Uysal P, Öktem A, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a peculiar variant of lichen planus. Dermatologica Sinica. 2017;35:210-212.

- Barros HR, Almeida JR, Mattos e Dinato SL, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):146-149.

- Bennàssar A, Mas A, Julià M, et al. Annular plaques in the skin folds: 4 cases of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:602-605.

- Ghorbel HH, Badri T, Ben Brahim E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:580.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pigmentosus-Inversus

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis with dense, bandlike, lymphocytic inflammation at the dermoepidermal junction with associated melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The physical examination and histopathology were consistent with a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPPI). Treatment was discussed with the patient, with options including phototherapy, tacrolimus, or a high-dose steroid. Given that the lesions were asymptomatic and not bothersome, the patient denied treatment and agreed to routine follow-up.

The first case of LPPI was reported in 20011; since then, approximately 100 cases have been reported in the literature.2 A rare variant of lichen planus, LPPI predominantly occurs in middle-aged women.2,3 Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus is characterized by well-circumscribed, brown macules confined to non-sun-exposed intertriginous areas such as the axillae and groin.2 Although the rash remains localized, multiple lesions could arise in the same area, such as the groin as seen in our patient (Figure 2). Unlike in lichen planus, the oral mucosa, nails, and scalp are not affected. Furthermore, pruritus typically is absent in most cases of LPPI.2,4 Histopathologic findings include an atrophic epidermis with lichenoid infiltrates of lymphocytes and histocytes as well as substantial pigmentary incontinence with melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis.4,5

Given the gender, age, and clinical features of our patient, this case represents a classic scenario of LPPI. It currently is unknown if ethnicity plays a role in the disorder. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus initially was thought to be more prevalent in White patients; however, studies have been reported in individuals with darker skin.1,2

The main differential diagnosis includes erythema dyschromicum perstans, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and lichen planus. Although erythema dyschromicum perstans develops in individuals with darker skin, lesions are restricted to the upper torso and limbs.2-4 In both lichen planus and lichen actinicus, skin findings primarily develop in sun-exposed areas, such as the face, neck, and hands.4,6 Given the negative history of trauma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was unlikely in our patient. Furthermore, a distinguishing characteristic of LPPI is the deposition of melanin deep within the dermal layer.3

Lesions developing in nonexposed intertriginous skin makes LPPI unique and distinguishes it from other more common conditions. The lesions commonly are hyperpigmented and are not as pruritic as other lichen-associated conditions. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus often persists for months, and the rash generally is resistant to treatment.2,5 Topical tacrolimus and high-dose steroids may improve symptoms, though results have varied substantially. In addition, some cases have resolved spontaneously.1,4,6,7 Because LPPI is asymptomatic and benign, spontaneous resolution and routine care is a reasonable treatment strategy. Some cases have supported this strategy as safe and high-value care.2

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pigmentosus-Inversus

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis with dense, bandlike, lymphocytic inflammation at the dermoepidermal junction with associated melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis (Figure 1). The physical examination and histopathology were consistent with a diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus (LPPI). Treatment was discussed with the patient, with options including phototherapy, tacrolimus, or a high-dose steroid. Given that the lesions were asymptomatic and not bothersome, the patient denied treatment and agreed to routine follow-up.

The first case of LPPI was reported in 20011; since then, approximately 100 cases have been reported in the literature.2 A rare variant of lichen planus, LPPI predominantly occurs in middle-aged women.2,3 Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus is characterized by well-circumscribed, brown macules confined to non-sun-exposed intertriginous areas such as the axillae and groin.2 Although the rash remains localized, multiple lesions could arise in the same area, such as the groin as seen in our patient (Figure 2). Unlike in lichen planus, the oral mucosa, nails, and scalp are not affected. Furthermore, pruritus typically is absent in most cases of LPPI.2,4 Histopathologic findings include an atrophic epidermis with lichenoid infiltrates of lymphocytes and histocytes as well as substantial pigmentary incontinence with melanin-containing macrophages in the papillary dermis.4,5

Given the gender, age, and clinical features of our patient, this case represents a classic scenario of LPPI. It currently is unknown if ethnicity plays a role in the disorder. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus initially was thought to be more prevalent in White patients; however, studies have been reported in individuals with darker skin.1,2

The main differential diagnosis includes erythema dyschromicum perstans, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and lichen planus. Although erythema dyschromicum perstans develops in individuals with darker skin, lesions are restricted to the upper torso and limbs.2-4 In both lichen planus and lichen actinicus, skin findings primarily develop in sun-exposed areas, such as the face, neck, and hands.4,6 Given the negative history of trauma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was unlikely in our patient. Furthermore, a distinguishing characteristic of LPPI is the deposition of melanin deep within the dermal layer.3

Lesions developing in nonexposed intertriginous skin makes LPPI unique and distinguishes it from other more common conditions. The lesions commonly are hyperpigmented and are not as pruritic as other lichen-associated conditions. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus often persists for months, and the rash generally is resistant to treatment.2,5 Topical tacrolimus and high-dose steroids may improve symptoms, though results have varied substantially. In addition, some cases have resolved spontaneously.1,4,6,7 Because LPPI is asymptomatic and benign, spontaneous resolution and routine care is a reasonable treatment strategy. Some cases have supported this strategy as safe and high-value care.2

- Mohamed M, Korbi M, Hammedi F, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus: a series of 10 Tunisian patients. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1088-1091.

- Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a rare variant of lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(suppl 1):AB239. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.959

- Chen S, Sun W, Zhou G, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: report of three Chinese cases and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2015;42:77-80.

- Tabanlıoǧlu-Onan D, Íncel-Uysal P, Öktem A, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a peculiar variant of lichen planus. Dermatologica Sinica. 2017;35:210-212.

- Barros HR, Almeida JR, Mattos e Dinato SL, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):146-149.

- Bennàssar A, Mas A, Julià M, et al. Annular plaques in the skin folds: 4 cases of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:602-605.

- Ghorbel HH, Badri T, Ben Brahim E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:580.

- Mohamed M, Korbi M, Hammedi F, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus: a series of 10 Tunisian patients. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1088-1091.

- Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a rare variant of lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(suppl 1):AB239. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.959

- Chen S, Sun W, Zhou G, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: report of three Chinese cases and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2015;42:77-80.

- Tabanlıoǧlu-Onan D, Íncel-Uysal P, Öktem A, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus: a peculiar variant of lichen planus. Dermatologica Sinica. 2017;35:210-212.

- Barros HR, Almeida JR, Mattos e Dinato SL, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):146-149.

- Bennàssar A, Mas A, Julià M, et al. Annular plaques in the skin folds: 4 cases of lichen planus pigmentosus-inversus [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:602-605.

- Ghorbel HH, Badri T, Ben Brahim E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus inversus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:580.

A 45-year-old African American woman presented with an asymptomatic rash that had worsened over the month prior to presentation. It initially began on the upper thighs and then spread to the abdomen, groin, and buttocks. The rash was mildly pruritic and had grown both in size and number of lesions. She had not tried any new over-the-counter medications. Her medical history was notable for late-stage breast cancer diagnosed 4 years prior that was treated with radiation and neoadjuvant NeoPACT—carboplatin, docetaxel, and pembrolizumab. One year prior to presentation, she underwent a lumpectomy that was complicated by gas gangrene of the finger. She has been in remission since the surgery. Physical examination at the current presentation was remarkable for multiple well-circumscribed, hyperpigmented macules on the medial thighs, lower abdomen, and buttocks. Syphilis antibody screening was negative.

It’s time to retire the president question

The president question – “Who’s the current president?” – has been a standard one of basic neurology assessments for years, probably since the answer was Ulysses S. Grant. It’s routinely asked by doctors, nurses, EEG techs, medical students, and pretty much anyone else trying to figure out someone’s mental status.

When I first began doing this, the answer was “George Bush” (at that time there’d only been one president by that name, so clarification wasn’t needed). Back then people answered the question (right or wrong) and we moved on. I don’t recall ever getting a dirty look, political lecture, or eye roll as a response.

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple anymore. As people have become increasingly polarized, it’s become seemingly impossible to get a response without a statement of support or anger. At best I get a straight answer. At worst I get a lecture on the “perils of a non-White society” (that was last week). Then they want my opinion, and years of practice have taught me to never discuss politics with patients, regardless of which side they’re on.

I don’t recall this being a problem until the late ‘90s, when the answer was “Clinton.” Occasionally I’d get a sarcastic comment referring to the Lewinsky affair, but that was about it.

Since then it’s gradually escalated, to where the question has become worthless. I don’t have time to hear a political diatribe from either side. This is a doctor appointment, not a debate club. The insistence by some that Trump won leaves me guessing if the person is stubborn or serious, and either way it shouldn’t be my job to figure that out. I take your appointment seriously, so the least you can do is the same.

So I’ve ditched the question for good. The current date, the location of my office, and other less controversial things will have to do. I’m here to take care of you, not have you try to pick a fight or make a political statement.

You’d think such a simple, time-honored, assessment question wouldn’t become such a problem. But

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The president question – “Who’s the current president?” – has been a standard one of basic neurology assessments for years, probably since the answer was Ulysses S. Grant. It’s routinely asked by doctors, nurses, EEG techs, medical students, and pretty much anyone else trying to figure out someone’s mental status.

When I first began doing this, the answer was “George Bush” (at that time there’d only been one president by that name, so clarification wasn’t needed). Back then people answered the question (right or wrong) and we moved on. I don’t recall ever getting a dirty look, political lecture, or eye roll as a response.

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple anymore. As people have become increasingly polarized, it’s become seemingly impossible to get a response without a statement of support or anger. At best I get a straight answer. At worst I get a lecture on the “perils of a non-White society” (that was last week). Then they want my opinion, and years of practice have taught me to never discuss politics with patients, regardless of which side they’re on.

I don’t recall this being a problem until the late ‘90s, when the answer was “Clinton.” Occasionally I’d get a sarcastic comment referring to the Lewinsky affair, but that was about it.

Since then it’s gradually escalated, to where the question has become worthless. I don’t have time to hear a political diatribe from either side. This is a doctor appointment, not a debate club. The insistence by some that Trump won leaves me guessing if the person is stubborn or serious, and either way it shouldn’t be my job to figure that out. I take your appointment seriously, so the least you can do is the same.

So I’ve ditched the question for good. The current date, the location of my office, and other less controversial things will have to do. I’m here to take care of you, not have you try to pick a fight or make a political statement.

You’d think such a simple, time-honored, assessment question wouldn’t become such a problem. But

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The president question – “Who’s the current president?” – has been a standard one of basic neurology assessments for years, probably since the answer was Ulysses S. Grant. It’s routinely asked by doctors, nurses, EEG techs, medical students, and pretty much anyone else trying to figure out someone’s mental status.

When I first began doing this, the answer was “George Bush” (at that time there’d only been one president by that name, so clarification wasn’t needed). Back then people answered the question (right or wrong) and we moved on. I don’t recall ever getting a dirty look, political lecture, or eye roll as a response.

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple anymore. As people have become increasingly polarized, it’s become seemingly impossible to get a response without a statement of support or anger. At best I get a straight answer. At worst I get a lecture on the “perils of a non-White society” (that was last week). Then they want my opinion, and years of practice have taught me to never discuss politics with patients, regardless of which side they’re on.

I don’t recall this being a problem until the late ‘90s, when the answer was “Clinton.” Occasionally I’d get a sarcastic comment referring to the Lewinsky affair, but that was about it.

Since then it’s gradually escalated, to where the question has become worthless. I don’t have time to hear a political diatribe from either side. This is a doctor appointment, not a debate club. The insistence by some that Trump won leaves me guessing if the person is stubborn or serious, and either way it shouldn’t be my job to figure that out. I take your appointment seriously, so the least you can do is the same.

So I’ve ditched the question for good. The current date, the location of my office, and other less controversial things will have to do. I’m here to take care of you, not have you try to pick a fight or make a political statement.

You’d think such a simple, time-honored, assessment question wouldn’t become such a problem. But

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

First CAR T-cell therapy for multiple myeloma: Abecma

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, described as a “living drug,” is now available for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who have been treated with four or more prior lines of therapy.

The Food and Drug Administration said these patients represent an “unmet medical need” when it granted approval for the new product – idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel; Abecma), developed by bluebird bio and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Ide-cel is the first CAR T-cell therapy to gain approval for use in multiple myeloma. It is also the first CAR T-cell therapy to target B-cell maturation antigen.

Previously approved CAR T-cell products target CD19 and have been approved for use in certain types of leukemia and lymphoma.

All the CAR T-cell therapies are customized treatments that are created specifically for each individual patient from their own blood. The patient’s own T cells are removed from the blood, are genetically modified and expanded, and are then infused back into the patient. These modified T cells then seek out and destroy blood cancer cells, and they continue to do so long term.

In some patients, this has led to eradication of disease that had previously progressed with every other treatment that had been tried – results that have been described as “absolutely remarkable” and “one-shot therapy that looks to be curative.”

However, this cell therapy comes with serious adverse effects, including neurologic toxicity and cytokine release syndrome (CRS), which can be life threatening. For this reason, all these products have a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy, and the use of CAR T-cell therapies is limited to designated centers.

In addition, these CAR T-cells products are phenomenally expensive; hospitals have reported heavy financial losses with their use, and patients have turned to crowdfunding to pay for these therapies.

‘Phenomenal’ results in MM

The FDA noted that approval of ide-cel for multiple myeloma is based on data from a multicenter study that involved 127 patients with relapsed/refractory disease who had received at least three prior lines of treatment.

The results from this trial were published Feb. 25 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An expert not involved in the trial described the results as “phenomenal.”

Krina Patel, MD, an associate professor in the department of lymphoma/myeloma at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said that “the response rate of 73% in a patient population with a median of six lines of therapy, and with one-third of those patients achieving a deep response of complete response or better, is phenomenal.

“We are very excited as a myeloma community for this study of idecabtagene vicleucel for relapsed/refractory patients,” Dr. Patel told this news organization at the time.

The lead investigator of the study, Nikhil Munshi, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, commented:

Both experts highlighted the poor prognosis for patients with relapsed/refractory disease. Recent decades have seen a flurry of new agents for myeloma, and there are now three main classes of agents: immunomodulatory agents, proteasome inhibitors, and anti-CD38 antibodies.

Nevertheless, in some patients, the disease continues to progress. For patients for whom treatments with all three classes of drugs have failed, the median progression-free survival is 3-4 months, and the median overall survival is 9 months.

In contrast, the results reported in the NEJM article showed that overall median progression-free survival was 8.8 months, but it was more than double that (20.2 months) for patients who achieved a complete or stringent complete response.

Estimated median overall survival was 19.4 months, and the overall survival was 78% at 12 months. The authors note that overall survival data are not yet mature.

The patients who were enrolled in the CAR T-cell trial had undergone many previous treatments. They had undergone a median of six prior drug therapies (range, 3-16), and most of the patients (120, 94%) had also undergone autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

In addition, the majority of patients (84%) had disease that was triple refractory (to an immunomodulatory agent, a proteasome inhibitor, and an anti-CD38 antibody), 60% had disease that was penta-exposed (to bortezomib, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and daratumumab), and 26% had disease that was penta-refractory.

In the NEJM article, the authors report that about a third of patients had a complete response to CAR T-cell therapy.

At a median follow-up of 13.3 months, 94 of 128 patients (73%) showed a response to therapy (P < .001); 42 (33%) showed a complete or stringent complete response; and 67 patients (52%) showed a “very good partial response or better,” they write.

In the FDA announcement of the product approval, the figures for complete response were slightly lower. “Of those studied, 28% of patients showed complete response – or disappearance of all signs of multiple myeloma – to Abecma, and 65% of this group remained in complete response to the treatment for at least 12 months,” the agency noted.

The FDA also noted that treatment with Abecma can cause severe side effects. The label carries a boxed warning regarding CRS, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome, neurologic toxicity, and prolonged cytopenia, all of which can be fatal or life threatening.

The most common side effects of Abecma are CRS, infections, fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and a weakened immune system. Side effects from treatment usually appear within the first 1-2 weeks after treatment, but some side effects may occur later.

The agency also noted that, to further evaluate the long-term safety of the drug, it is requiring the manufacturer to conduct a postmarketing observational study.

“The FDA remains committed to advancing novel treatment options for areas of unmet patient need,” said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

“While there is no cure for multiple myeloma, the long-term outlook can vary based on the individual’s age and the stage of the condition at the time of diagnosis. Today’s approval provides a new treatment option for patients who have this uncommon type of cancer.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, described as a “living drug,” is now available for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who have been treated with four or more prior lines of therapy.

The Food and Drug Administration said these patients represent an “unmet medical need” when it granted approval for the new product – idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel; Abecma), developed by bluebird bio and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Ide-cel is the first CAR T-cell therapy to gain approval for use in multiple myeloma. It is also the first CAR T-cell therapy to target B-cell maturation antigen.

Previously approved CAR T-cell products target CD19 and have been approved for use in certain types of leukemia and lymphoma.

All the CAR T-cell therapies are customized treatments that are created specifically for each individual patient from their own blood. The patient’s own T cells are removed from the blood, are genetically modified and expanded, and are then infused back into the patient. These modified T cells then seek out and destroy blood cancer cells, and they continue to do so long term.

In some patients, this has led to eradication of disease that had previously progressed with every other treatment that had been tried – results that have been described as “absolutely remarkable” and “one-shot therapy that looks to be curative.”

However, this cell therapy comes with serious adverse effects, including neurologic toxicity and cytokine release syndrome (CRS), which can be life threatening. For this reason, all these products have a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy, and the use of CAR T-cell therapies is limited to designated centers.

In addition, these CAR T-cells products are phenomenally expensive; hospitals have reported heavy financial losses with their use, and patients have turned to crowdfunding to pay for these therapies.

‘Phenomenal’ results in MM

The FDA noted that approval of ide-cel for multiple myeloma is based on data from a multicenter study that involved 127 patients with relapsed/refractory disease who had received at least three prior lines of treatment.

The results from this trial were published Feb. 25 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An expert not involved in the trial described the results as “phenomenal.”

Krina Patel, MD, an associate professor in the department of lymphoma/myeloma at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said that “the response rate of 73% in a patient population with a median of six lines of therapy, and with one-third of those patients achieving a deep response of complete response or better, is phenomenal.

“We are very excited as a myeloma community for this study of idecabtagene vicleucel for relapsed/refractory patients,” Dr. Patel told this news organization at the time.

The lead investigator of the study, Nikhil Munshi, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, commented:

Both experts highlighted the poor prognosis for patients with relapsed/refractory disease. Recent decades have seen a flurry of new agents for myeloma, and there are now three main classes of agents: immunomodulatory agents, proteasome inhibitors, and anti-CD38 antibodies.

Nevertheless, in some patients, the disease continues to progress. For patients for whom treatments with all three classes of drugs have failed, the median progression-free survival is 3-4 months, and the median overall survival is 9 months.

In contrast, the results reported in the NEJM article showed that overall median progression-free survival was 8.8 months, but it was more than double that (20.2 months) for patients who achieved a complete or stringent complete response.

Estimated median overall survival was 19.4 months, and the overall survival was 78% at 12 months. The authors note that overall survival data are not yet mature.

The patients who were enrolled in the CAR T-cell trial had undergone many previous treatments. They had undergone a median of six prior drug therapies (range, 3-16), and most of the patients (120, 94%) had also undergone autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

In addition, the majority of patients (84%) had disease that was triple refractory (to an immunomodulatory agent, a proteasome inhibitor, and an anti-CD38 antibody), 60% had disease that was penta-exposed (to bortezomib, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and daratumumab), and 26% had disease that was penta-refractory.

In the NEJM article, the authors report that about a third of patients had a complete response to CAR T-cell therapy.

At a median follow-up of 13.3 months, 94 of 128 patients (73%) showed a response to therapy (P < .001); 42 (33%) showed a complete or stringent complete response; and 67 patients (52%) showed a “very good partial response or better,” they write.

In the FDA announcement of the product approval, the figures for complete response were slightly lower. “Of those studied, 28% of patients showed complete response – or disappearance of all signs of multiple myeloma – to Abecma, and 65% of this group remained in complete response to the treatment for at least 12 months,” the agency noted.

The FDA also noted that treatment with Abecma can cause severe side effects. The label carries a boxed warning regarding CRS, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome, neurologic toxicity, and prolonged cytopenia, all of which can be fatal or life threatening.

The most common side effects of Abecma are CRS, infections, fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and a weakened immune system. Side effects from treatment usually appear within the first 1-2 weeks after treatment, but some side effects may occur later.

The agency also noted that, to further evaluate the long-term safety of the drug, it is requiring the manufacturer to conduct a postmarketing observational study.

“The FDA remains committed to advancing novel treatment options for areas of unmet patient need,” said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

“While there is no cure for multiple myeloma, the long-term outlook can vary based on the individual’s age and the stage of the condition at the time of diagnosis. Today’s approval provides a new treatment option for patients who have this uncommon type of cancer.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, described as a “living drug,” is now available for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who have been treated with four or more prior lines of therapy.

The Food and Drug Administration said these patients represent an “unmet medical need” when it granted approval for the new product – idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel; Abecma), developed by bluebird bio and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Ide-cel is the first CAR T-cell therapy to gain approval for use in multiple myeloma. It is also the first CAR T-cell therapy to target B-cell maturation antigen.

Previously approved CAR T-cell products target CD19 and have been approved for use in certain types of leukemia and lymphoma.

All the CAR T-cell therapies are customized treatments that are created specifically for each individual patient from their own blood. The patient’s own T cells are removed from the blood, are genetically modified and expanded, and are then infused back into the patient. These modified T cells then seek out and destroy blood cancer cells, and they continue to do so long term.

In some patients, this has led to eradication of disease that had previously progressed with every other treatment that had been tried – results that have been described as “absolutely remarkable” and “one-shot therapy that looks to be curative.”

However, this cell therapy comes with serious adverse effects, including neurologic toxicity and cytokine release syndrome (CRS), which can be life threatening. For this reason, all these products have a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy, and the use of CAR T-cell therapies is limited to designated centers.

In addition, these CAR T-cells products are phenomenally expensive; hospitals have reported heavy financial losses with their use, and patients have turned to crowdfunding to pay for these therapies.

‘Phenomenal’ results in MM

The FDA noted that approval of ide-cel for multiple myeloma is based on data from a multicenter study that involved 127 patients with relapsed/refractory disease who had received at least three prior lines of treatment.

The results from this trial were published Feb. 25 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

An expert not involved in the trial described the results as “phenomenal.”

Krina Patel, MD, an associate professor in the department of lymphoma/myeloma at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said that “the response rate of 73% in a patient population with a median of six lines of therapy, and with one-third of those patients achieving a deep response of complete response or better, is phenomenal.

“We are very excited as a myeloma community for this study of idecabtagene vicleucel for relapsed/refractory patients,” Dr. Patel told this news organization at the time.

The lead investigator of the study, Nikhil Munshi, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, commented:

Both experts highlighted the poor prognosis for patients with relapsed/refractory disease. Recent decades have seen a flurry of new agents for myeloma, and there are now three main classes of agents: immunomodulatory agents, proteasome inhibitors, and anti-CD38 antibodies.

Nevertheless, in some patients, the disease continues to progress. For patients for whom treatments with all three classes of drugs have failed, the median progression-free survival is 3-4 months, and the median overall survival is 9 months.

In contrast, the results reported in the NEJM article showed that overall median progression-free survival was 8.8 months, but it was more than double that (20.2 months) for patients who achieved a complete or stringent complete response.

Estimated median overall survival was 19.4 months, and the overall survival was 78% at 12 months. The authors note that overall survival data are not yet mature.

The patients who were enrolled in the CAR T-cell trial had undergone many previous treatments. They had undergone a median of six prior drug therapies (range, 3-16), and most of the patients (120, 94%) had also undergone autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

In addition, the majority of patients (84%) had disease that was triple refractory (to an immunomodulatory agent, a proteasome inhibitor, and an anti-CD38 antibody), 60% had disease that was penta-exposed (to bortezomib, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and daratumumab), and 26% had disease that was penta-refractory.

In the NEJM article, the authors report that about a third of patients had a complete response to CAR T-cell therapy.

At a median follow-up of 13.3 months, 94 of 128 patients (73%) showed a response to therapy (P < .001); 42 (33%) showed a complete or stringent complete response; and 67 patients (52%) showed a “very good partial response or better,” they write.

In the FDA announcement of the product approval, the figures for complete response were slightly lower. “Of those studied, 28% of patients showed complete response – or disappearance of all signs of multiple myeloma – to Abecma, and 65% of this group remained in complete response to the treatment for at least 12 months,” the agency noted.

The FDA also noted that treatment with Abecma can cause severe side effects. The label carries a boxed warning regarding CRS, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome, neurologic toxicity, and prolonged cytopenia, all of which can be fatal or life threatening.

The most common side effects of Abecma are CRS, infections, fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, and a weakened immune system. Side effects from treatment usually appear within the first 1-2 weeks after treatment, but some side effects may occur later.

The agency also noted that, to further evaluate the long-term safety of the drug, it is requiring the manufacturer to conduct a postmarketing observational study.

“The FDA remains committed to advancing novel treatment options for areas of unmet patient need,” said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

“While there is no cure for multiple myeloma, the long-term outlook can vary based on the individual’s age and the stage of the condition at the time of diagnosis. Today’s approval provides a new treatment option for patients who have this uncommon type of cancer.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Call to eradicate all types of HPV cancers, not just cervical

The World Health Organization’s call for the elimination of cervical cancer worldwide is a laudable goal and one that many organizations across the globe have endorsed.

Yet some would say that this goal goes only halfway, and that the real finish line should be to eliminate all vaccine-type HPV infections that cause multiple cancers, in men as well as women.

One proponent of sweeping HPV prevention is Mark Jit, PhD, from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

In the long run, the WHO’s call to eliminate cervical cancer is “insufficiently ambitious” he writes in a special issue of Preventive Medicine.

“The point is, if you are trying to eliminate cervical cancer, you’ve run part of the race,” he said.

“But why not run that extra third and get rid of the virus, then you never have to worry about it again,” Dr. Jit elaborated in an interview.

Winning that race, however, is dependent on a gender-neutral HPV vaccination policy, he pointed out.

At present, the WHO advocates only for female vaccination and screening.

Some countries have already taken the matter into their own hands. As of May 2020, 33 countries and four territories have gender-neutral vaccination schedules.

Others are also calling for gender-neutral HPV vaccination to achieve a far wider public health good.

“I completely agree that our ultimate goal should be the elimination of all HPV-related cancers – but we will require gender-neutral vaccination to do it,” says Anna Giuliano, PhD, professor and director, Center for Immunization and Infection Research in Cancer, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa.

“The reason why WHO started with cervical cancer elimination is that it is likely to be the first cancer that we can achieve this with, and if you look internationally, cervical cancer has the highest burden,” Dr. Giuliano told this news organization.

“But it’s important to understand that it’s not just females who are at risk for HPV disease, men have serious consequences from HPV infection, too,” she said.

In fact, rates of HPV-related cancers and mortality in men exceed those for women in countries that have effective cervical cancer screening programs, she points out in an editorial in the same issue of Preventive Medicine.

Rates in men are driven largely by HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer, but not only, Dr. Giuliano noted in an interview.

Rates of anal cancer among men who have sex with men (MSM) are at least as high as rates of cervical cancer among women living in the poorest countries of the world, where 85% of cervical cancer deaths now occur, she noted. If MSM are HIV positive, rates of anal cancer are even higher.

Unethical to leave males out?

Arguments in favor of gender-neutral HPV vaccination abound, but the most compelling among them is that society really should give males an opportunity to receive direct protection against all types of HPV infection, Dr. Giuliano commented.

Indeed, in the U.K., experts argue that it is unethical to leave males out of achieving direct protection against HPV infection, she noted.

With a female-only vaccination strategy, “males are only protected if they stay in a population where there are high female vaccination rates – and very few countries have achieved high rates of vaccine dissemination and have sustained it,” she pointed out. But that applies only to heterosexual men, who develop some herd immunity from exposure to vaccinated females; this is not the case for MSM.

On a pragmatic note, a vaccine program that targets a larger number of people against HPV infection – which would be achieved with gender-neutral vaccination – is going to be more resilient against temporary changes in vaccine uptake, such as what has happened over the past year.

“During the pandemic, people may have had virtual clinic visits, but they haven’t had in-person visits, which is what you need for vaccination,” Dr. Giuliano pointed out. “So over the past year, there has been a major drop in vaccination rates,” she said.

Eliminating cervical cancer

Currently, the WHO plans for eliminating cervical cancer involve a strategy of vaccinating 90% of girls by the age of 15, screening 70% of women with a high performance test by the age of 35 and again at 45, and treating 90% of women with cervical disease – the so-called “90-70-90” strategy.

Dr. Jit agrees that very high levels of vaccine coverage would eradicate the HPV types causing almost all cases of cervical cancer. The same strategy would also sharply reduce the need for preventive measures in the future.

However, as Dr. Jit argues, 90% female-only coverage will not be sufficient to eliminate HPV 16 transmission, although 90% coverage in both males and females – namely a gender-neutral strategy – might. To show this, Dr. Jit and colleagues used the HPV-ADVISE transmission model in India.

Results from this modeling exercise suggest that 90% coverage of both sexes would bring the prevalence of HPV 16 close to elimination, defined as reducing the prevalence of HPV 16 to below 10 per 100,000 in the population.

In addition, because even at this low level, HPV transmission can be sustained in a small group of sex workers and their clients, achieving 95% coverage of 10-year-old girls who might become female sex workers in the future will likely achieve the goal of HPV 16 elimination, as Dr. Jit suggests.

OPSCC elimination

Elimination of another HPV-related cancer, oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCCs), is discussed in another paper in the same journal.

HPV-related OPSCCs are mostly associated specifically with HPV 16.

There is currently an epidemic of this cancer among middle-aged men in the Nordic countries of Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden; incidence rates have tripled over the past 30 years, note Tuomas Lehtinen, PhD, FICAN-MID, Tampere, Finland and colleagues.

They propose a two-step action plan – gender-neutral vaccination in adolescent boys and girls, and a screening program for adults born in 1995 or earlier.

The first step is already underway, and the recent implementation of school-based HPV vaccination programs in the Nordic countries is predicted to gradually decrease the incidence of HPV-related OPSCCs, they write.

“Even if HPV vaccination does not cure established infections, it can prevent re-infection/recurrence of associated lesions in 45% to 65% of individuals with anal or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia,” the authors write, “and there is high VE (vaccine efficacy) against oropharyngeal HPV infections as well.”

Furthermore, there is a tenfold relative risk of tonsillar and base of tongue cancers in spouses of women diagnosed with invasive anogenital cancer, researchers also point out. “This underlines the importance of breaking genito-oral transmission chains.”

The screening of adults born in 1995 for HPV-related OPSCC is still at a planning stage.

In a proof-of-concept study for the stepwise prevention of OPSCC, the authors suggest that target birth cohorts first be stratified and then randomized into serological HPV 16 E6 antibody screening or no screening. HPV 16 antibody-positive women and their spouses then could be invited for HPV vaccination followed by 2 HPV DNA tests.

Unscreened women and their spouses would serve as population-based controls. “Even if gender-neutral vaccination results in rapid elimination of HPV circulation, the effects of persistent, [prevalent] HPV infections on the most HPV-associated tonsillar cancer will continue for decades after HPV circulation has stopped,” the authors predict.