User login

Exuberant Lymphomatoid Papulosis of the Head and Upper Trunk

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is a chronic, recurring, self-healing, primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. This disease affects patients of all ages but most commonly presents in the fifth decade with a slight male predominance.1 The estimated worldwide incidence is 1.2 to 1.9 cases per 1,000,000 individuals, and the 10-year survival rate is close to 100%.1 Clinically, LyP presents as a few to more than 100 red-brown papules or nodules, some with hemorrhagic crust or central necrosis, often occurring in crops and in various stages of evolution. They most commonly are distributed on the trunk and extremities; however, the face, scalp, and oral mucosa rarely may be involved. Each lesion may last on average 3 to 8 weeks, with residual hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation of the skin or superficial varioliform scars. The clinical characteristic of spontaneous regression is crucial for distinguishing LyP from other forms of cutaneous lymphoma.2 The disease course is variable, lasting anywhere from a few months to decades. Histopathologically, LyP consists of a frequently CD30+ lymphocytic proliferation in multiple described patterns.1 We report a case of LyP in a patient who initially presented with pink edematous papules and vesicles that progressed to crusted ulcerations, nodules, and deep necrotic eschars on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk. Multiple biopsies and T-cell gene rearrangement studies were necessary to make the diagnosis.

A 73-year-old man presented with edematous crusted papules and nodules as well as scarring with serous drainage on the scalp and upper trunk of several months’ duration. He also reported pain and pruritus. He had a medical history of B-cell CD20− chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) that was treated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, and intravenous immunoglobulin approximately one year prior and currently was in remission; prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy; hypertension; and type 2 diabetes mellitus. His medications included metoprolol, valsartan, and glipizide.

Histopathology revealed a hypersensitivity reaction, and the clinicopathologic correlation was believed to represent an exuberant arthropod bite reaction in the setting of CLL. The eruption responded well to oral prednisone and topical corticosteroids but recurred when the medications were withdrawn. A repeat biopsy resulted in a diagnosis of atypical eosinophil-predominant Sweet syndrome. The condition resolved.

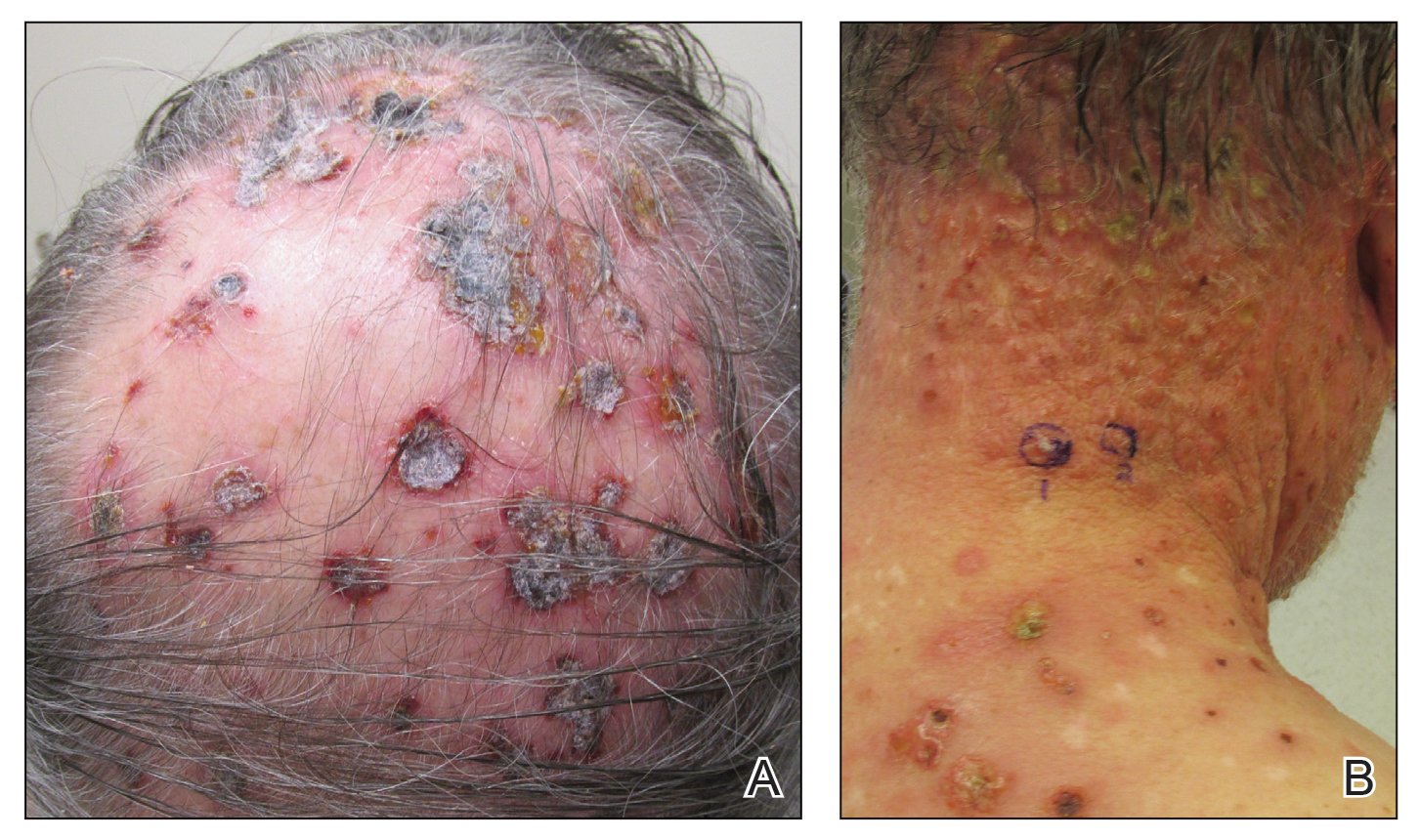

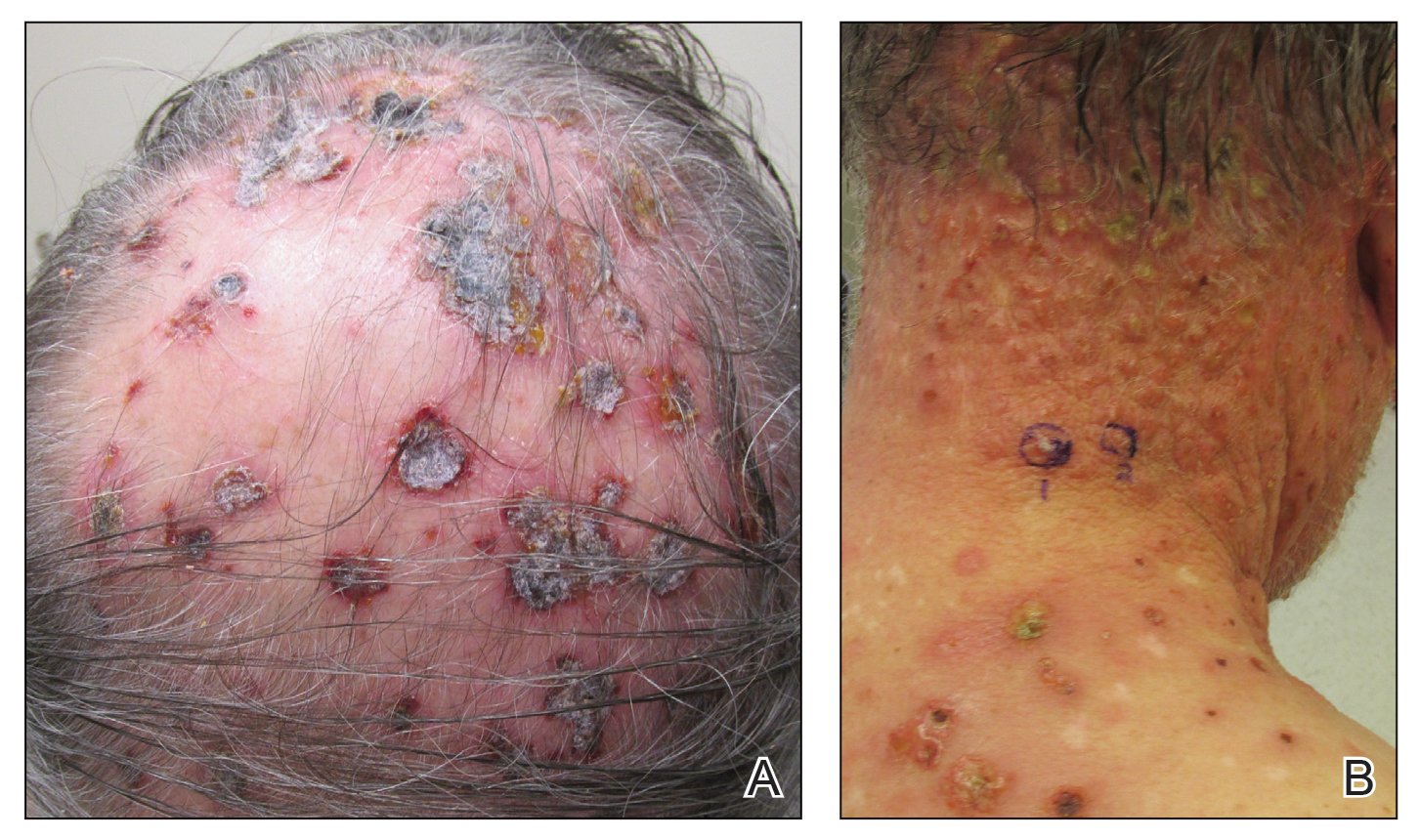

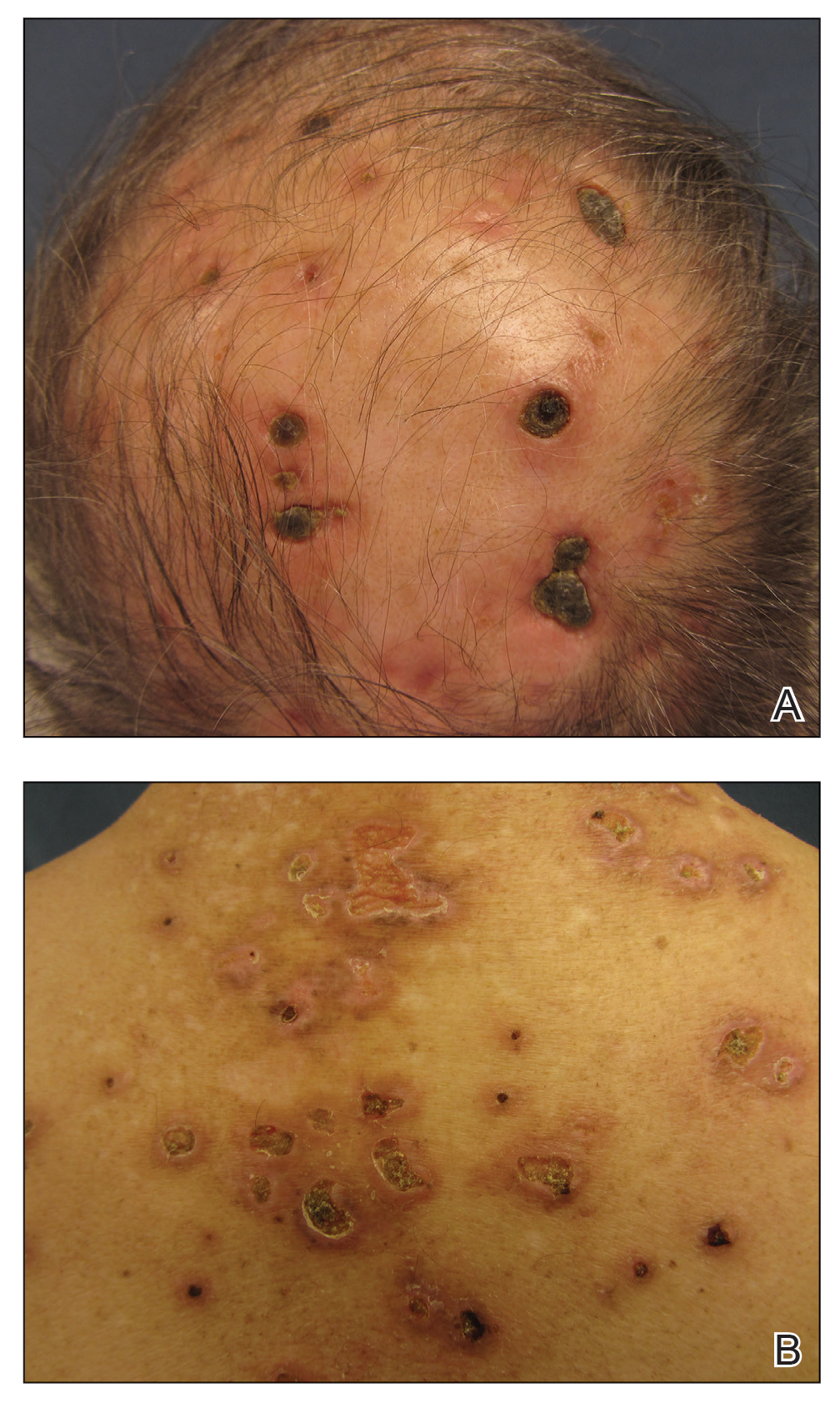

Three years later he developed multiple honey-crusted, superficial ulcers as well as serous, fluid-filled vesiculobullae on the head. A tissue culture revealed Proteus mirabilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecalis, and was negative for acid-fast bacteria and fungus. Biopsy of these lesions revealed dermal ulceration with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and numerous eosinophils as well as a few clustered CD30+ cells; direct immunofluorescence was negative. An extensive laboratory workup including bullous pemphigoid antigens, C-reactive protein, antinuclear antibodies comprehensive profile, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, serum protein electrophoresis, lactate dehydrogenase, complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic profile, thyroid-stimulating hormone, uric acid, C3, C4, immunoglobulin profile, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, and urinalysis was unremarkable. He improved with courses of minocycline, prednisone, and topical clobetasol, but he had periodic and progressive flares over several months with punched-out crusted ulcerations developing on the scalp (Figure 1A) and neck (Figure 1B). The oral and ocular mucosae were uninvolved, but the nasal mucosa had some involvement.

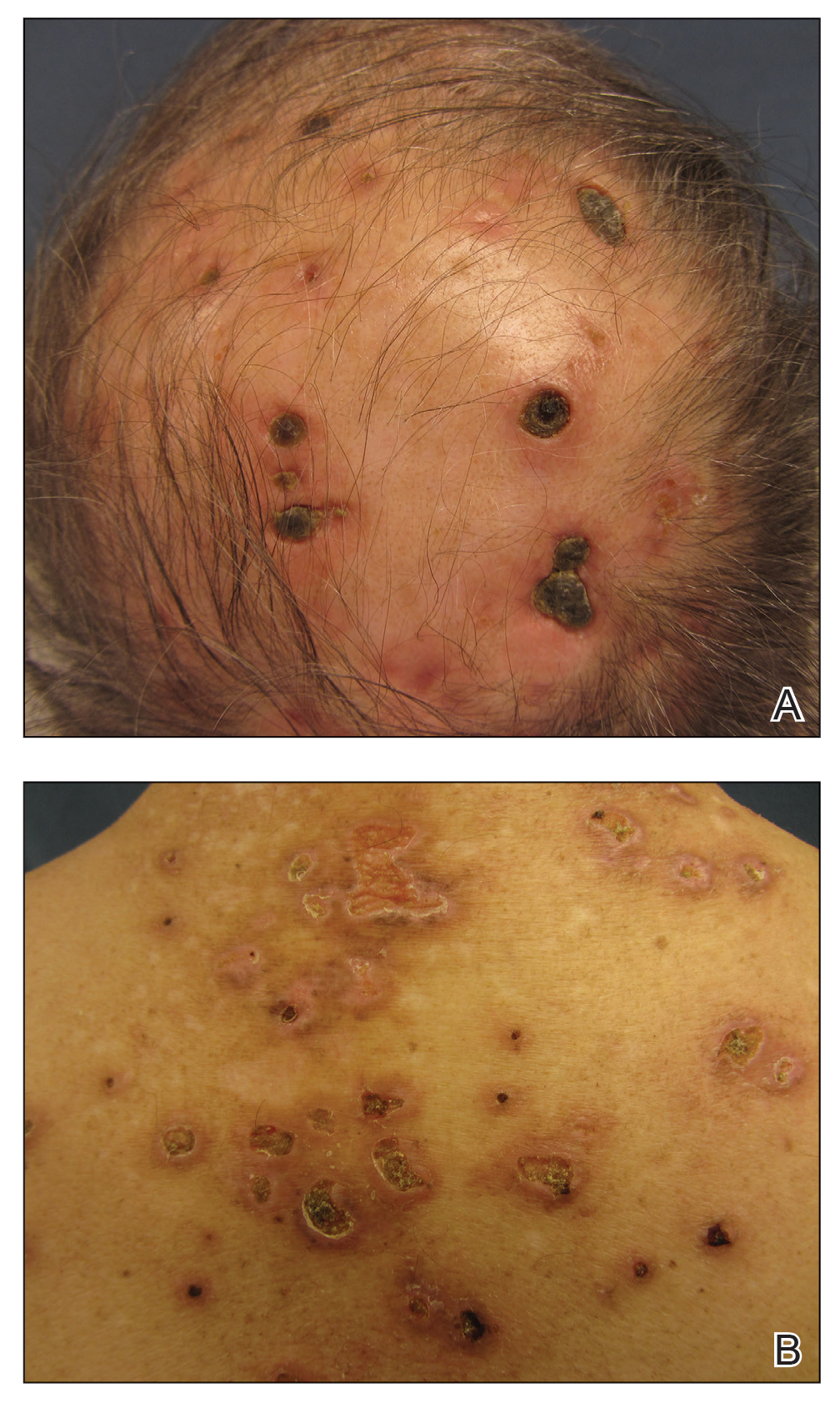

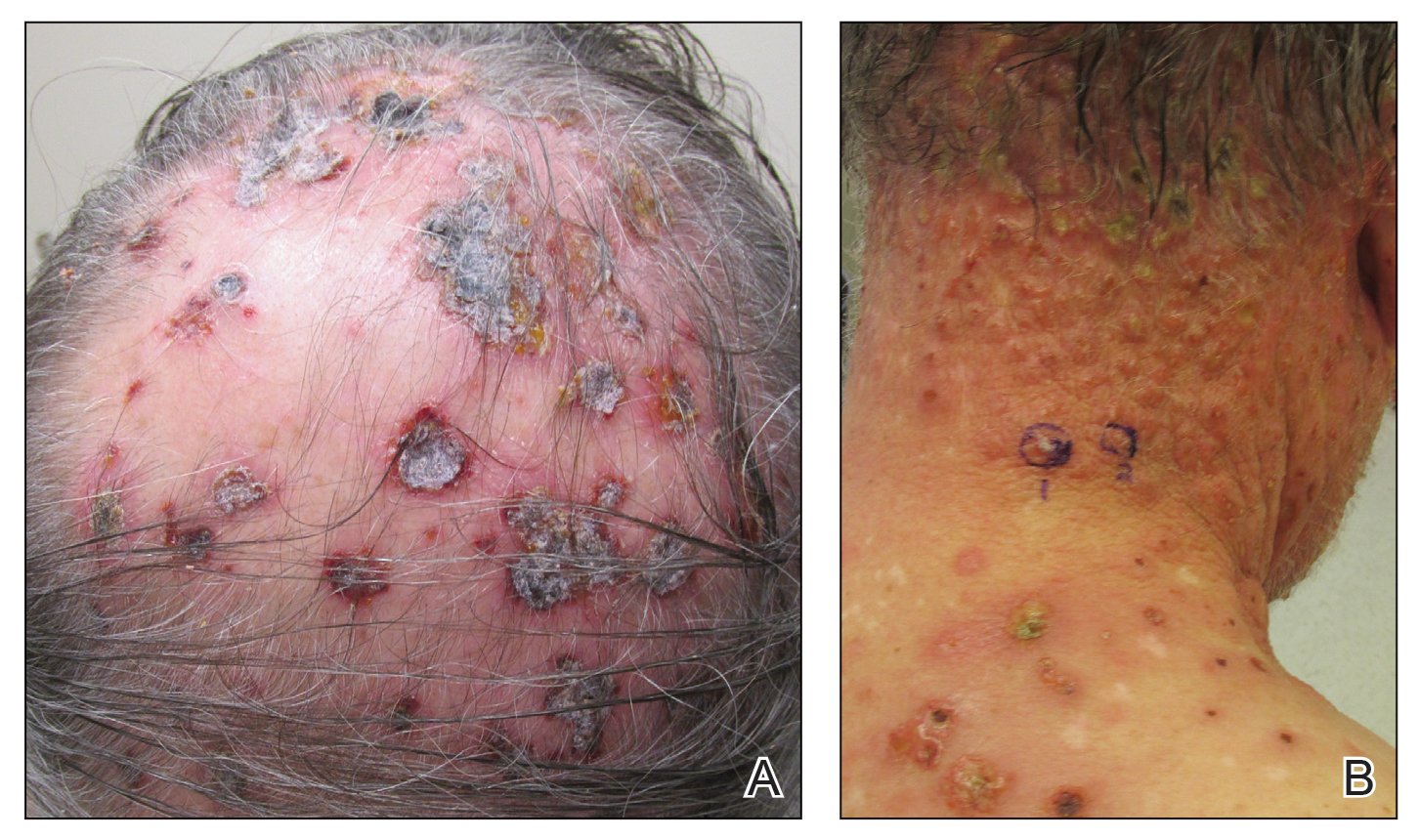

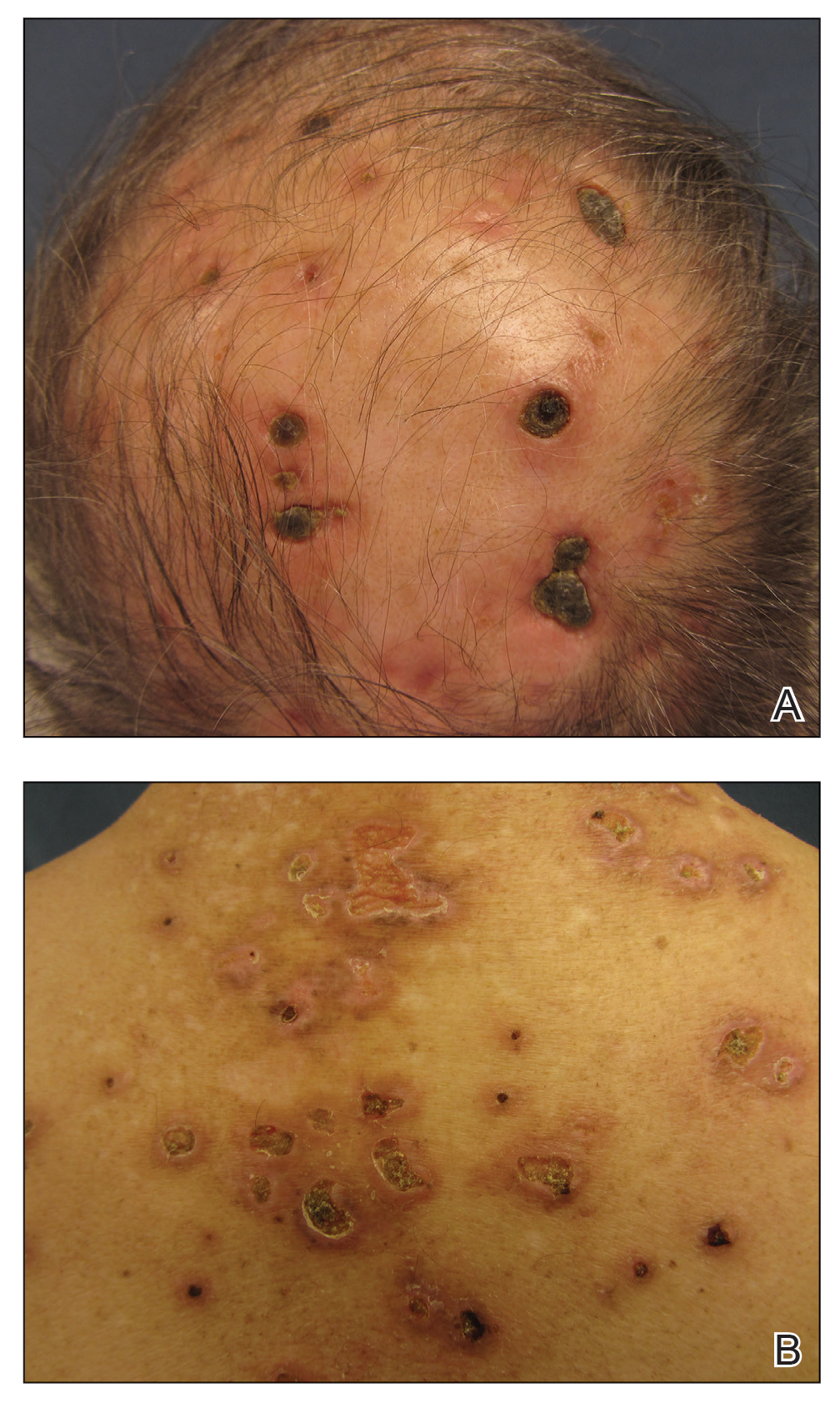

A repeat biopsy demonstrated an atypical CD30+ lymphoid infiltrate favoring LyP. T-cell clonality performed on this specimen and the prior biopsy demonstrated identical T-cell receptor β and γ clones. CD3, CD5, CD7, and CD4 immunostains highlighted the perivascular, perifollicular, and folliculotropic lymphocytic infiltrate. CD8 highlighted occasional background small T cells with only a few folliculotropic forms. A CD30 study revealed several scattered enlarged lymphocytes, and CD20 displayed a few dispersed B cells. A repeat perilesional direct immunofluorescence study was again negative. With treatment, he later formed multiple dry punched-out ulcers with dark eschars on the scalp, posterior neck, and upper back. There were multiple scars on the head, chest, and back, and no vesicles or bullae were present (Figure 2). The patient was presented at a meeting of the Philadelphia Dermatological Society and a consensus diagnosis of LyP was reached. The patient has continued to improve with oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily, topical clobetasol, and topical mupirocin.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is an indolent cutaneous lymphoma; however, it is associated with the potential development of a second hematologic malignancy, with some disagreement in the literature concerning the exact percentage.3 In some studies, lymphoma has been estimated to occur in less than 20% of cases.4,5 Wieser et al1 reported a retrospective analysis of 180 patients with LyP that revealed a secondary malignancy in 52% of patients. They also reported that the number of lesions and the symptom severity were not associated with lymphoma development.1 Similarly, Cordel et al6 reported a diagnosis of lymphoma in 41% of 106 patients. These analyses reveal that the association with lymphoma may be higher than previously thought, but referral bias may be a confounding factor in these numbers.1,5,6 Associated malignancies may occur prior to, concomitantly, or years after the diagnosis of LyP. The most frequently reported malignancies include mycosis fungoides, Hodgkin lymphoma, and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma.1,4

Nicolaou et al3 indicated that head involvement was more likely associated with lymphoma. Our patient had a history of CLL prior to the development of LyP, and it continues to be in remission. The incidence of CLL in patients with LyP is reported to be 0.8%.4 Our patient had an exuberant case of LyP predominantly involving the head, neck, and upper torso, which is an unusual distribution. Vesiculobullous lesions also are uncharacteristic of LyP and may have represented concomitant bullous impetigo, but bullous variants of LyP also have been reported.7 Due to the unique distribution and characteristic scarring, Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid also was considered in the clinical differential diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of LyP associated with malignancy is not definitively known. Theories propose that progression to a malignant clonal T-cell population may come from cytogenetic events, inadequate host response, or persistent antigenic or viral stimulation.4 Studies have demonstrated overlapping T-cell receptor gene rearrangement clones in lesions in patients with both LyP and mycosis fungoides, suggesting a common origin between the diseases.8 Other theories suggest that LyP may arise from an early, reactive, polyclonal lymphoid expansion that evolves into a clonal neoplastic process.4 Interestingly, LyP is a clonal T-cell disorder, while Hodgkin lymphoma and CLL are B-cell disorders. Thus, reports of CLL occurring with LyP, as in our patient, may support the theory that LyP arises from an early stem-cell or precursor-cell defect.4

There is no cure for LyP and data regarding the potential of aggressive therapy on the prevention of secondary lymphomas is lacking. Wieser et al1 reported that treatment did not prevent the progression to lymphoma in their retrospective analysis of 180 patients. The number of lesions, frequency of outbreaks, and extent of the scarring can dictate the treatment approach for LyP. Conservative topical therapies include corticosteroids, bexarotene, and imiquimod. Mupirocin may help to prevent infection of ulcerated lesions.1,2 Low-dose methotrexate has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment in reducing the number of lesions, particularly for scarring or cosmetically sensitive areas. Oral methotrexate at a dosage of 10 mg to 25 mg weekly tapered to the lowest effective dose may suppress outbreaks of LyP lesions.1,2 Other therapies include psoralen plus UVA, UVB, interferon alfa-2a, oral bexarotene, oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, etretinate, mycophenolic acid, photodynamic therapy, oral antibiotics, excision, and radiotherapy.1,2 Systemic chemotherapy and total-skin electron beam therapy have shown efficacy in clearing the lesions; however, the disease recurs after discontinuation of therapy.2 Systemic chemotherapy is not recommended for the treatment of LyP, as risks outweigh the benefits and it does not reduce the risk for developing lymphoma.1 The prognosis generally is good, though long-term follow-up is imperative to monitor for the development of other lymphomas.

Our patient presented with LyP a few months after completing chemotherapy for his CLL. It is unknown if he developed LyP just before the time of presentation, or if he may have developed it at the same time as his CLL by a common inciting event. In the latter case, it is speculative that the LyP may have been controlled by chemotherapy for his CLL, only to become clinically apparent after discontinuation, then naturally remit for a longer period. Case reports such as ours with unusual clinical presentations, B-cell lymphoma associations, and unique timing of lymphoma onset may help to provide insight into the pathogenesis of this disease.

We highlighted an unusual case of LyP that presented clinically with crusted ulcerations as well as vesiculobullous and edematous papules that progressed into deep punched-out ulcers with eschars, nodules, and scarring on the head and upper trunk. Lymphomatoid papulosis can be difficult to diagnose histopathologically at the early stages, and multiple repeat biopsies may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. T-cell gene rearrangement and immunohistochemistry studies are helpful along with clinical correlation to establish a diagnosis in these cases. We recommend that physicians keep LyP on the differential diagnosis for patients with similar clinical presentations and remain vigilant in monitoring for the development of secondary lymphoma.

- Wieser I, Oh C, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67.

- Duvic M. CD30+ neoplasms of the skin. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2011;6:245-250.

- Nicolaou V, Papadavid E, Ekonomise A, et al. Association of clinicopathological characteristics with secondary neoplastic lymphoproliferative disorders in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1303-1307.

- Ahn C, Orscheln C, Huang W. Lymphomatoid papulosis as a harbinger of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1923-1925.

- Kunishige J, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-5781.

- Cordelet al. Frequency and risk factors for associated lymphomas in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. Oncologist. 2016;21:76-83.

- Sureda N, Thomas L, Bathelier E, et al. Bullous lymphomatoid papulosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:800-801.

- de la Garza Bravo M, Patel KP, Loghavi S, et al. Shared clonality in distinctive lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and mycosis fungoides occurring in the same patients suggests a common origin. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:558-569.

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is a chronic, recurring, self-healing, primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. This disease affects patients of all ages but most commonly presents in the fifth decade with a slight male predominance.1 The estimated worldwide incidence is 1.2 to 1.9 cases per 1,000,000 individuals, and the 10-year survival rate is close to 100%.1 Clinically, LyP presents as a few to more than 100 red-brown papules or nodules, some with hemorrhagic crust or central necrosis, often occurring in crops and in various stages of evolution. They most commonly are distributed on the trunk and extremities; however, the face, scalp, and oral mucosa rarely may be involved. Each lesion may last on average 3 to 8 weeks, with residual hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation of the skin or superficial varioliform scars. The clinical characteristic of spontaneous regression is crucial for distinguishing LyP from other forms of cutaneous lymphoma.2 The disease course is variable, lasting anywhere from a few months to decades. Histopathologically, LyP consists of a frequently CD30+ lymphocytic proliferation in multiple described patterns.1 We report a case of LyP in a patient who initially presented with pink edematous papules and vesicles that progressed to crusted ulcerations, nodules, and deep necrotic eschars on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk. Multiple biopsies and T-cell gene rearrangement studies were necessary to make the diagnosis.

A 73-year-old man presented with edematous crusted papules and nodules as well as scarring with serous drainage on the scalp and upper trunk of several months’ duration. He also reported pain and pruritus. He had a medical history of B-cell CD20− chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) that was treated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, and intravenous immunoglobulin approximately one year prior and currently was in remission; prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy; hypertension; and type 2 diabetes mellitus. His medications included metoprolol, valsartan, and glipizide.

Histopathology revealed a hypersensitivity reaction, and the clinicopathologic correlation was believed to represent an exuberant arthropod bite reaction in the setting of CLL. The eruption responded well to oral prednisone and topical corticosteroids but recurred when the medications were withdrawn. A repeat biopsy resulted in a diagnosis of atypical eosinophil-predominant Sweet syndrome. The condition resolved.

Three years later he developed multiple honey-crusted, superficial ulcers as well as serous, fluid-filled vesiculobullae on the head. A tissue culture revealed Proteus mirabilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecalis, and was negative for acid-fast bacteria and fungus. Biopsy of these lesions revealed dermal ulceration with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and numerous eosinophils as well as a few clustered CD30+ cells; direct immunofluorescence was negative. An extensive laboratory workup including bullous pemphigoid antigens, C-reactive protein, antinuclear antibodies comprehensive profile, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, serum protein electrophoresis, lactate dehydrogenase, complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic profile, thyroid-stimulating hormone, uric acid, C3, C4, immunoglobulin profile, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, and urinalysis was unremarkable. He improved with courses of minocycline, prednisone, and topical clobetasol, but he had periodic and progressive flares over several months with punched-out crusted ulcerations developing on the scalp (Figure 1A) and neck (Figure 1B). The oral and ocular mucosae were uninvolved, but the nasal mucosa had some involvement.

A repeat biopsy demonstrated an atypical CD30+ lymphoid infiltrate favoring LyP. T-cell clonality performed on this specimen and the prior biopsy demonstrated identical T-cell receptor β and γ clones. CD3, CD5, CD7, and CD4 immunostains highlighted the perivascular, perifollicular, and folliculotropic lymphocytic infiltrate. CD8 highlighted occasional background small T cells with only a few folliculotropic forms. A CD30 study revealed several scattered enlarged lymphocytes, and CD20 displayed a few dispersed B cells. A repeat perilesional direct immunofluorescence study was again negative. With treatment, he later formed multiple dry punched-out ulcers with dark eschars on the scalp, posterior neck, and upper back. There were multiple scars on the head, chest, and back, and no vesicles or bullae were present (Figure 2). The patient was presented at a meeting of the Philadelphia Dermatological Society and a consensus diagnosis of LyP was reached. The patient has continued to improve with oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily, topical clobetasol, and topical mupirocin.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is an indolent cutaneous lymphoma; however, it is associated with the potential development of a second hematologic malignancy, with some disagreement in the literature concerning the exact percentage.3 In some studies, lymphoma has been estimated to occur in less than 20% of cases.4,5 Wieser et al1 reported a retrospective analysis of 180 patients with LyP that revealed a secondary malignancy in 52% of patients. They also reported that the number of lesions and the symptom severity were not associated with lymphoma development.1 Similarly, Cordel et al6 reported a diagnosis of lymphoma in 41% of 106 patients. These analyses reveal that the association with lymphoma may be higher than previously thought, but referral bias may be a confounding factor in these numbers.1,5,6 Associated malignancies may occur prior to, concomitantly, or years after the diagnosis of LyP. The most frequently reported malignancies include mycosis fungoides, Hodgkin lymphoma, and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma.1,4

Nicolaou et al3 indicated that head involvement was more likely associated with lymphoma. Our patient had a history of CLL prior to the development of LyP, and it continues to be in remission. The incidence of CLL in patients with LyP is reported to be 0.8%.4 Our patient had an exuberant case of LyP predominantly involving the head, neck, and upper torso, which is an unusual distribution. Vesiculobullous lesions also are uncharacteristic of LyP and may have represented concomitant bullous impetigo, but bullous variants of LyP also have been reported.7 Due to the unique distribution and characteristic scarring, Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid also was considered in the clinical differential diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of LyP associated with malignancy is not definitively known. Theories propose that progression to a malignant clonal T-cell population may come from cytogenetic events, inadequate host response, or persistent antigenic or viral stimulation.4 Studies have demonstrated overlapping T-cell receptor gene rearrangement clones in lesions in patients with both LyP and mycosis fungoides, suggesting a common origin between the diseases.8 Other theories suggest that LyP may arise from an early, reactive, polyclonal lymphoid expansion that evolves into a clonal neoplastic process.4 Interestingly, LyP is a clonal T-cell disorder, while Hodgkin lymphoma and CLL are B-cell disorders. Thus, reports of CLL occurring with LyP, as in our patient, may support the theory that LyP arises from an early stem-cell or precursor-cell defect.4

There is no cure for LyP and data regarding the potential of aggressive therapy on the prevention of secondary lymphomas is lacking. Wieser et al1 reported that treatment did not prevent the progression to lymphoma in their retrospective analysis of 180 patients. The number of lesions, frequency of outbreaks, and extent of the scarring can dictate the treatment approach for LyP. Conservative topical therapies include corticosteroids, bexarotene, and imiquimod. Mupirocin may help to prevent infection of ulcerated lesions.1,2 Low-dose methotrexate has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment in reducing the number of lesions, particularly for scarring or cosmetically sensitive areas. Oral methotrexate at a dosage of 10 mg to 25 mg weekly tapered to the lowest effective dose may suppress outbreaks of LyP lesions.1,2 Other therapies include psoralen plus UVA, UVB, interferon alfa-2a, oral bexarotene, oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, etretinate, mycophenolic acid, photodynamic therapy, oral antibiotics, excision, and radiotherapy.1,2 Systemic chemotherapy and total-skin electron beam therapy have shown efficacy in clearing the lesions; however, the disease recurs after discontinuation of therapy.2 Systemic chemotherapy is not recommended for the treatment of LyP, as risks outweigh the benefits and it does not reduce the risk for developing lymphoma.1 The prognosis generally is good, though long-term follow-up is imperative to monitor for the development of other lymphomas.

Our patient presented with LyP a few months after completing chemotherapy for his CLL. It is unknown if he developed LyP just before the time of presentation, or if he may have developed it at the same time as his CLL by a common inciting event. In the latter case, it is speculative that the LyP may have been controlled by chemotherapy for his CLL, only to become clinically apparent after discontinuation, then naturally remit for a longer period. Case reports such as ours with unusual clinical presentations, B-cell lymphoma associations, and unique timing of lymphoma onset may help to provide insight into the pathogenesis of this disease.

We highlighted an unusual case of LyP that presented clinically with crusted ulcerations as well as vesiculobullous and edematous papules that progressed into deep punched-out ulcers with eschars, nodules, and scarring on the head and upper trunk. Lymphomatoid papulosis can be difficult to diagnose histopathologically at the early stages, and multiple repeat biopsies may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. T-cell gene rearrangement and immunohistochemistry studies are helpful along with clinical correlation to establish a diagnosis in these cases. We recommend that physicians keep LyP on the differential diagnosis for patients with similar clinical presentations and remain vigilant in monitoring for the development of secondary lymphoma.

To the Editor:

Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is a chronic, recurring, self-healing, primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. This disease affects patients of all ages but most commonly presents in the fifth decade with a slight male predominance.1 The estimated worldwide incidence is 1.2 to 1.9 cases per 1,000,000 individuals, and the 10-year survival rate is close to 100%.1 Clinically, LyP presents as a few to more than 100 red-brown papules or nodules, some with hemorrhagic crust or central necrosis, often occurring in crops and in various stages of evolution. They most commonly are distributed on the trunk and extremities; however, the face, scalp, and oral mucosa rarely may be involved. Each lesion may last on average 3 to 8 weeks, with residual hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation of the skin or superficial varioliform scars. The clinical characteristic of spontaneous regression is crucial for distinguishing LyP from other forms of cutaneous lymphoma.2 The disease course is variable, lasting anywhere from a few months to decades. Histopathologically, LyP consists of a frequently CD30+ lymphocytic proliferation in multiple described patterns.1 We report a case of LyP in a patient who initially presented with pink edematous papules and vesicles that progressed to crusted ulcerations, nodules, and deep necrotic eschars on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk. Multiple biopsies and T-cell gene rearrangement studies were necessary to make the diagnosis.

A 73-year-old man presented with edematous crusted papules and nodules as well as scarring with serous drainage on the scalp and upper trunk of several months’ duration. He also reported pain and pruritus. He had a medical history of B-cell CD20− chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) that was treated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, and intravenous immunoglobulin approximately one year prior and currently was in remission; prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy; hypertension; and type 2 diabetes mellitus. His medications included metoprolol, valsartan, and glipizide.

Histopathology revealed a hypersensitivity reaction, and the clinicopathologic correlation was believed to represent an exuberant arthropod bite reaction in the setting of CLL. The eruption responded well to oral prednisone and topical corticosteroids but recurred when the medications were withdrawn. A repeat biopsy resulted in a diagnosis of atypical eosinophil-predominant Sweet syndrome. The condition resolved.

Three years later he developed multiple honey-crusted, superficial ulcers as well as serous, fluid-filled vesiculobullae on the head. A tissue culture revealed Proteus mirabilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecalis, and was negative for acid-fast bacteria and fungus. Biopsy of these lesions revealed dermal ulceration with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and numerous eosinophils as well as a few clustered CD30+ cells; direct immunofluorescence was negative. An extensive laboratory workup including bullous pemphigoid antigens, C-reactive protein, antinuclear antibodies comprehensive profile, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, serum protein electrophoresis, lactate dehydrogenase, complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic profile, thyroid-stimulating hormone, uric acid, C3, C4, immunoglobulin profile, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, and urinalysis was unremarkable. He improved with courses of minocycline, prednisone, and topical clobetasol, but he had periodic and progressive flares over several months with punched-out crusted ulcerations developing on the scalp (Figure 1A) and neck (Figure 1B). The oral and ocular mucosae were uninvolved, but the nasal mucosa had some involvement.

A repeat biopsy demonstrated an atypical CD30+ lymphoid infiltrate favoring LyP. T-cell clonality performed on this specimen and the prior biopsy demonstrated identical T-cell receptor β and γ clones. CD3, CD5, CD7, and CD4 immunostains highlighted the perivascular, perifollicular, and folliculotropic lymphocytic infiltrate. CD8 highlighted occasional background small T cells with only a few folliculotropic forms. A CD30 study revealed several scattered enlarged lymphocytes, and CD20 displayed a few dispersed B cells. A repeat perilesional direct immunofluorescence study was again negative. With treatment, he later formed multiple dry punched-out ulcers with dark eschars on the scalp, posterior neck, and upper back. There were multiple scars on the head, chest, and back, and no vesicles or bullae were present (Figure 2). The patient was presented at a meeting of the Philadelphia Dermatological Society and a consensus diagnosis of LyP was reached. The patient has continued to improve with oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily, topical clobetasol, and topical mupirocin.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is an indolent cutaneous lymphoma; however, it is associated with the potential development of a second hematologic malignancy, with some disagreement in the literature concerning the exact percentage.3 In some studies, lymphoma has been estimated to occur in less than 20% of cases.4,5 Wieser et al1 reported a retrospective analysis of 180 patients with LyP that revealed a secondary malignancy in 52% of patients. They also reported that the number of lesions and the symptom severity were not associated with lymphoma development.1 Similarly, Cordel et al6 reported a diagnosis of lymphoma in 41% of 106 patients. These analyses reveal that the association with lymphoma may be higher than previously thought, but referral bias may be a confounding factor in these numbers.1,5,6 Associated malignancies may occur prior to, concomitantly, or years after the diagnosis of LyP. The most frequently reported malignancies include mycosis fungoides, Hodgkin lymphoma, and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma.1,4

Nicolaou et al3 indicated that head involvement was more likely associated with lymphoma. Our patient had a history of CLL prior to the development of LyP, and it continues to be in remission. The incidence of CLL in patients with LyP is reported to be 0.8%.4 Our patient had an exuberant case of LyP predominantly involving the head, neck, and upper torso, which is an unusual distribution. Vesiculobullous lesions also are uncharacteristic of LyP and may have represented concomitant bullous impetigo, but bullous variants of LyP also have been reported.7 Due to the unique distribution and characteristic scarring, Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid also was considered in the clinical differential diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of LyP associated with malignancy is not definitively known. Theories propose that progression to a malignant clonal T-cell population may come from cytogenetic events, inadequate host response, or persistent antigenic or viral stimulation.4 Studies have demonstrated overlapping T-cell receptor gene rearrangement clones in lesions in patients with both LyP and mycosis fungoides, suggesting a common origin between the diseases.8 Other theories suggest that LyP may arise from an early, reactive, polyclonal lymphoid expansion that evolves into a clonal neoplastic process.4 Interestingly, LyP is a clonal T-cell disorder, while Hodgkin lymphoma and CLL are B-cell disorders. Thus, reports of CLL occurring with LyP, as in our patient, may support the theory that LyP arises from an early stem-cell or precursor-cell defect.4

There is no cure for LyP and data regarding the potential of aggressive therapy on the prevention of secondary lymphomas is lacking. Wieser et al1 reported that treatment did not prevent the progression to lymphoma in their retrospective analysis of 180 patients. The number of lesions, frequency of outbreaks, and extent of the scarring can dictate the treatment approach for LyP. Conservative topical therapies include corticosteroids, bexarotene, and imiquimod. Mupirocin may help to prevent infection of ulcerated lesions.1,2 Low-dose methotrexate has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment in reducing the number of lesions, particularly for scarring or cosmetically sensitive areas. Oral methotrexate at a dosage of 10 mg to 25 mg weekly tapered to the lowest effective dose may suppress outbreaks of LyP lesions.1,2 Other therapies include psoralen plus UVA, UVB, interferon alfa-2a, oral bexarotene, oral acyclovir or valacyclovir, etretinate, mycophenolic acid, photodynamic therapy, oral antibiotics, excision, and radiotherapy.1,2 Systemic chemotherapy and total-skin electron beam therapy have shown efficacy in clearing the lesions; however, the disease recurs after discontinuation of therapy.2 Systemic chemotherapy is not recommended for the treatment of LyP, as risks outweigh the benefits and it does not reduce the risk for developing lymphoma.1 The prognosis generally is good, though long-term follow-up is imperative to monitor for the development of other lymphomas.

Our patient presented with LyP a few months after completing chemotherapy for his CLL. It is unknown if he developed LyP just before the time of presentation, or if he may have developed it at the same time as his CLL by a common inciting event. In the latter case, it is speculative that the LyP may have been controlled by chemotherapy for his CLL, only to become clinically apparent after discontinuation, then naturally remit for a longer period. Case reports such as ours with unusual clinical presentations, B-cell lymphoma associations, and unique timing of lymphoma onset may help to provide insight into the pathogenesis of this disease.

We highlighted an unusual case of LyP that presented clinically with crusted ulcerations as well as vesiculobullous and edematous papules that progressed into deep punched-out ulcers with eschars, nodules, and scarring on the head and upper trunk. Lymphomatoid papulosis can be difficult to diagnose histopathologically at the early stages, and multiple repeat biopsies may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. T-cell gene rearrangement and immunohistochemistry studies are helpful along with clinical correlation to establish a diagnosis in these cases. We recommend that physicians keep LyP on the differential diagnosis for patients with similar clinical presentations and remain vigilant in monitoring for the development of secondary lymphoma.

- Wieser I, Oh C, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67.

- Duvic M. CD30+ neoplasms of the skin. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2011;6:245-250.

- Nicolaou V, Papadavid E, Ekonomise A, et al. Association of clinicopathological characteristics with secondary neoplastic lymphoproliferative disorders in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1303-1307.

- Ahn C, Orscheln C, Huang W. Lymphomatoid papulosis as a harbinger of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1923-1925.

- Kunishige J, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-5781.

- Cordelet al. Frequency and risk factors for associated lymphomas in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. Oncologist. 2016;21:76-83.

- Sureda N, Thomas L, Bathelier E, et al. Bullous lymphomatoid papulosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:800-801.

- de la Garza Bravo M, Patel KP, Loghavi S, et al. Shared clonality in distinctive lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and mycosis fungoides occurring in the same patients suggests a common origin. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:558-569.

- Wieser I, Oh C, Talpur R, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: treatment response and associated lymphomas in a study of 180 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:59-67.

- Duvic M. CD30+ neoplasms of the skin. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2011;6:245-250.

- Nicolaou V, Papadavid E, Ekonomise A, et al. Association of clinicopathological characteristics with secondary neoplastic lymphoproliferative disorders in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1303-1307.

- Ahn C, Orscheln C, Huang W. Lymphomatoid papulosis as a harbinger of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1923-1925.

- Kunishige J, McDonald H, Alvarez G, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis and associated lymphomas: a retrospective case series of 84 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:576-5781.

- Cordelet al. Frequency and risk factors for associated lymphomas in patients with lymphomatoid papulosis. Oncologist. 2016;21:76-83.

- Sureda N, Thomas L, Bathelier E, et al. Bullous lymphomatoid papulosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:800-801.

- de la Garza Bravo M, Patel KP, Loghavi S, et al. Shared clonality in distinctive lesions of lymphomatoid papulosis and mycosis fungoides occurring in the same patients suggests a common origin. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:558-569.

Practice Points

- Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) is a chronic, recurring, self-healing, primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by red-brown papules or nodules, some with hemorrhagic crust or central necrosis, often occurring in crops and in various stages of evolution.

- Histopathologically, LyP consists of a frequently CD30Mathematical Pi LT Std+ lymphocytic proliferation in multiple described patterns.

- Lymphomatoid papulosis is an indolent cutaneous lymphoma; however, it is associated with the potential development of a second hematologic malignancy.

Dynamic ultrasonography: An idea whose time has come (videos)

VIDEO 1A Liberal use of your nonscanning hand on dynamic scanning shows “wiggling” of debris classic of a hemorrhagic corpus luteum

--

VIDEO 1B Liberal use of your nonscanning hand helps identify a small postmenopausal ovary

--

VIDEO 2A Dynamic scanning can give the correct diagnosis even though clips were used! This clip appears to show a relatively normal uterus

--

VIDEO 2B Dynamic scanning can give the correct diagnosis even though clips were used! Same patient as in Video 2A showing what appears to be a solid adnexal mass

--

VIDEO 2C Dynamic scan clearly shows the “mass” to be a pedunculated fibroid

--

VIDEO 3A Video clip of a classic endometrioma

--

VIDEO 3B Classic endometrioma showing no Doppler flow internally

--

VIDEO 4A Video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

--

VIDEO 4B Another example of video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

--

VIDEO 4C Another example of video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

--

VIDEO 5A Sliding organ sign with normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5B Sliding sign showing adherent ovary (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5C Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5D Left ovary: Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5E Right ovary: Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5F Normal mobility even with a classic endometrioma (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5G Adherent ovary (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 6A Dynamic scanning shows the ovary to be “stuck” in the cul-de-sac in a patient with endometriosis

--

VIDEO 6B Dynamic scanning in another patient with endometriosis showing markedly retroverted uterus with adherent bowel posteriorly

--

VIDEO 6C Dynamic scanning in another patient with endometriosis showing markedly retroverted uterus with adherent bowel posteriorly

--

VIDEO 7 Cystocele or urethral lengthening are key elements for the diagnosis of incontinence with or without pelvic relaxation

--

VIDEO 8 Urethral lengthening is a key element for the diagnosis of incontinence with or without pelvic relaxation

VIDEO 1A Liberal use of your nonscanning hand on dynamic scanning shows “wiggling” of debris classic of a hemorrhagic corpus luteum

--

VIDEO 1B Liberal use of your nonscanning hand helps identify a small postmenopausal ovary

--

VIDEO 2A Dynamic scanning can give the correct diagnosis even though clips were used! This clip appears to show a relatively normal uterus

--

VIDEO 2B Dynamic scanning can give the correct diagnosis even though clips were used! Same patient as in Video 2A showing what appears to be a solid adnexal mass

--

VIDEO 2C Dynamic scan clearly shows the “mass” to be a pedunculated fibroid

--

VIDEO 3A Video clip of a classic endometrioma

--

VIDEO 3B Classic endometrioma showing no Doppler flow internally

--

VIDEO 4A Video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

--

VIDEO 4B Another example of video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

--

VIDEO 4C Another example of video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

--

VIDEO 5A Sliding organ sign with normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5B Sliding sign showing adherent ovary (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5C Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5D Left ovary: Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5E Right ovary: Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5F Normal mobility even with a classic endometrioma (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5G Adherent ovary (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 6A Dynamic scanning shows the ovary to be “stuck” in the cul-de-sac in a patient with endometriosis

--

VIDEO 6B Dynamic scanning in another patient with endometriosis showing markedly retroverted uterus with adherent bowel posteriorly

--

VIDEO 6C Dynamic scanning in another patient with endometriosis showing markedly retroverted uterus with adherent bowel posteriorly

--

VIDEO 7 Cystocele or urethral lengthening are key elements for the diagnosis of incontinence with or without pelvic relaxation

--

VIDEO 8 Urethral lengthening is a key element for the diagnosis of incontinence with or without pelvic relaxation

VIDEO 1A Liberal use of your nonscanning hand on dynamic scanning shows “wiggling” of debris classic of a hemorrhagic corpus luteum

--

VIDEO 1B Liberal use of your nonscanning hand helps identify a small postmenopausal ovary

--

VIDEO 2A Dynamic scanning can give the correct diagnosis even though clips were used! This clip appears to show a relatively normal uterus

--

VIDEO 2B Dynamic scanning can give the correct diagnosis even though clips were used! Same patient as in Video 2A showing what appears to be a solid adnexal mass

--

VIDEO 2C Dynamic scan clearly shows the “mass” to be a pedunculated fibroid

--

VIDEO 3A Video clip of a classic endometrioma

--

VIDEO 3B Classic endometrioma showing no Doppler flow internally

--

VIDEO 4A Video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

--

VIDEO 4B Another example of video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

--

VIDEO 4C Another example of video of dynamic assessment in a patient with pain symptoms with a hydrosalpinx

--

VIDEO 5A Sliding organ sign with normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5B Sliding sign showing adherent ovary (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5C Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5D Left ovary: Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5E Right ovary: Normal mobility (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5F Normal mobility even with a classic endometrioma (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 5G Adherent ovary (Courtesy of Dr. Ilan Timor-Tritsch)

--

VIDEO 6A Dynamic scanning shows the ovary to be “stuck” in the cul-de-sac in a patient with endometriosis

--

VIDEO 6B Dynamic scanning in another patient with endometriosis showing markedly retroverted uterus with adherent bowel posteriorly

--

VIDEO 6C Dynamic scanning in another patient with endometriosis showing markedly retroverted uterus with adherent bowel posteriorly

--

VIDEO 7 Cystocele or urethral lengthening are key elements for the diagnosis of incontinence with or without pelvic relaxation

--

VIDEO 8 Urethral lengthening is a key element for the diagnosis of incontinence with or without pelvic relaxation

IBD rates rising among Medicare patients

The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease increased significantly among Americans aged 67 years and older from 2001 to 2018, based on data from more than 25 million Medicare beneficiaries.

The worldwide prevalence – or rate of existing cases – of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) increased from 3.7 million in 1990 to 6.8 million in 2017, wrote Fang Xu, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues. “As the prevalence increases with age group, it is important to understand the disease epidemiology among the older population,” they said.

In a study published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the researchers reviewed 2018 Medicare data for 25.1 million beneficiaries aged 67 years and older to assess prevalence trends overall and by race and ethnicity. Over the study period, the study population ranged from 23.7 million persons in 2009 to 25.6 million persons in 2018. The incidence – or rate of new cases – of IBD peaks at 15-29 years of age, but approximately 10%-15% of new cases develop in adults aged 60 years and older, so the prevalence of IBD overall is expected to increase over time with the aging of the U.S. population, the researchers said.

In this population of beneficiaries, 0.40% overall had a Crohn’s disease diagnosis and 0.64% had an ulcerative colitis diagnosis. The prevalence for both diseases was consistently highest among non-Hispanic Whites, the researchers noted. In addition, the prevalence of Crohn’s disease was highest among younger beneficiaries, while the prevalence of ulcerative colitis was highest among those aged 75-84 years. Other factors associated with higher IBD prevalence were female gender and residence in large fringe metropolitan counties.

The overall age-adjusted prevalence of Crohn’s disease increased over time with an annual percentage change (APC) of 3.4%, and the overall age-adjusted prevalence of ulcerative colitis increased with an APC of 2.8%. When the researchers examined subgroups of race and ethnicity, the annual increases were higher for non-Hispanic Blacks for both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, with APCs of 5.0% and 3.5%, respectively. “The potential rapid increase of disease prevalence in certain racial and ethnic minority groups indicates the need for tailored disease management strategies in these populations,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of socioeconomic data, the potential for coding errors related to Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, and the lack of generalizability to all older adults in the United States, the researchers noted. However, “Medicare data are a useful resource to monitor prevalence of IBD over time, understand its prevalence among older adults, assess differences by demographic and geographic characteristics, and have rich information to study health care use,” they concluded.

Consider the younger population

The data from the study need to be considered in the context of an accumulation of patients with IBD, and the distinction between incidence and prevalence, Stephen B. Hanauer, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview.

The overall incidence of IBD is much greater in younger individuals (approximately ages 15-29 years) compared with older adults, he said. Patients with IBD don’t die of it; they grow old with it. Consequently, the prevalence in the Medicare population increases over time, he explained.

The data may be of interest to the practicing clinician, but would be most useful to hospital and Medicare administrators in terms of planning for an increase in the number of older adults surviving into older adulthood with IBD who will require care, he noted.

The researchers and Dr. Hanauer had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Help your patients better understand their IBD treatment options by sharing AGA’s patient education, “Living with IBD,” in the AGA GI Patient Center at www.gastro.org/IBD.

The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease increased significantly among Americans aged 67 years and older from 2001 to 2018, based on data from more than 25 million Medicare beneficiaries.

The worldwide prevalence – or rate of existing cases – of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) increased from 3.7 million in 1990 to 6.8 million in 2017, wrote Fang Xu, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues. “As the prevalence increases with age group, it is important to understand the disease epidemiology among the older population,” they said.

In a study published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the researchers reviewed 2018 Medicare data for 25.1 million beneficiaries aged 67 years and older to assess prevalence trends overall and by race and ethnicity. Over the study period, the study population ranged from 23.7 million persons in 2009 to 25.6 million persons in 2018. The incidence – or rate of new cases – of IBD peaks at 15-29 years of age, but approximately 10%-15% of new cases develop in adults aged 60 years and older, so the prevalence of IBD overall is expected to increase over time with the aging of the U.S. population, the researchers said.

In this population of beneficiaries, 0.40% overall had a Crohn’s disease diagnosis and 0.64% had an ulcerative colitis diagnosis. The prevalence for both diseases was consistently highest among non-Hispanic Whites, the researchers noted. In addition, the prevalence of Crohn’s disease was highest among younger beneficiaries, while the prevalence of ulcerative colitis was highest among those aged 75-84 years. Other factors associated with higher IBD prevalence were female gender and residence in large fringe metropolitan counties.

The overall age-adjusted prevalence of Crohn’s disease increased over time with an annual percentage change (APC) of 3.4%, and the overall age-adjusted prevalence of ulcerative colitis increased with an APC of 2.8%. When the researchers examined subgroups of race and ethnicity, the annual increases were higher for non-Hispanic Blacks for both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, with APCs of 5.0% and 3.5%, respectively. “The potential rapid increase of disease prevalence in certain racial and ethnic minority groups indicates the need for tailored disease management strategies in these populations,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of socioeconomic data, the potential for coding errors related to Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, and the lack of generalizability to all older adults in the United States, the researchers noted. However, “Medicare data are a useful resource to monitor prevalence of IBD over time, understand its prevalence among older adults, assess differences by demographic and geographic characteristics, and have rich information to study health care use,” they concluded.

Consider the younger population

The data from the study need to be considered in the context of an accumulation of patients with IBD, and the distinction between incidence and prevalence, Stephen B. Hanauer, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview.

The overall incidence of IBD is much greater in younger individuals (approximately ages 15-29 years) compared with older adults, he said. Patients with IBD don’t die of it; they grow old with it. Consequently, the prevalence in the Medicare population increases over time, he explained.

The data may be of interest to the practicing clinician, but would be most useful to hospital and Medicare administrators in terms of planning for an increase in the number of older adults surviving into older adulthood with IBD who will require care, he noted.

The researchers and Dr. Hanauer had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Help your patients better understand their IBD treatment options by sharing AGA’s patient education, “Living with IBD,” in the AGA GI Patient Center at www.gastro.org/IBD.

The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease increased significantly among Americans aged 67 years and older from 2001 to 2018, based on data from more than 25 million Medicare beneficiaries.

The worldwide prevalence – or rate of existing cases – of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) increased from 3.7 million in 1990 to 6.8 million in 2017, wrote Fang Xu, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues. “As the prevalence increases with age group, it is important to understand the disease epidemiology among the older population,” they said.

In a study published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the researchers reviewed 2018 Medicare data for 25.1 million beneficiaries aged 67 years and older to assess prevalence trends overall and by race and ethnicity. Over the study period, the study population ranged from 23.7 million persons in 2009 to 25.6 million persons in 2018. The incidence – or rate of new cases – of IBD peaks at 15-29 years of age, but approximately 10%-15% of new cases develop in adults aged 60 years and older, so the prevalence of IBD overall is expected to increase over time with the aging of the U.S. population, the researchers said.

In this population of beneficiaries, 0.40% overall had a Crohn’s disease diagnosis and 0.64% had an ulcerative colitis diagnosis. The prevalence for both diseases was consistently highest among non-Hispanic Whites, the researchers noted. In addition, the prevalence of Crohn’s disease was highest among younger beneficiaries, while the prevalence of ulcerative colitis was highest among those aged 75-84 years. Other factors associated with higher IBD prevalence were female gender and residence in large fringe metropolitan counties.

The overall age-adjusted prevalence of Crohn’s disease increased over time with an annual percentage change (APC) of 3.4%, and the overall age-adjusted prevalence of ulcerative colitis increased with an APC of 2.8%. When the researchers examined subgroups of race and ethnicity, the annual increases were higher for non-Hispanic Blacks for both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, with APCs of 5.0% and 3.5%, respectively. “The potential rapid increase of disease prevalence in certain racial and ethnic minority groups indicates the need for tailored disease management strategies in these populations,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of socioeconomic data, the potential for coding errors related to Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, and the lack of generalizability to all older adults in the United States, the researchers noted. However, “Medicare data are a useful resource to monitor prevalence of IBD over time, understand its prevalence among older adults, assess differences by demographic and geographic characteristics, and have rich information to study health care use,” they concluded.

Consider the younger population

The data from the study need to be considered in the context of an accumulation of patients with IBD, and the distinction between incidence and prevalence, Stephen B. Hanauer, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview.

The overall incidence of IBD is much greater in younger individuals (approximately ages 15-29 years) compared with older adults, he said. Patients with IBD don’t die of it; they grow old with it. Consequently, the prevalence in the Medicare population increases over time, he explained.

The data may be of interest to the practicing clinician, but would be most useful to hospital and Medicare administrators in terms of planning for an increase in the number of older adults surviving into older adulthood with IBD who will require care, he noted.

The researchers and Dr. Hanauer had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Help your patients better understand their IBD treatment options by sharing AGA’s patient education, “Living with IBD,” in the AGA GI Patient Center at www.gastro.org/IBD.

FROM MMWR

PIVKA-II shows promise as HCC biomarker

Key clinical point: Increased levels of prothrombin induced by vitamin K deficiency or antagonist- II (PIVKA-II) identified patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Median PIVKA-II serum levels were significantly higher in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (181.50 mAU/mL) vs patients with benign (noncancerous) liver disease (28.60 mAU/mL) or healthy controls (21.82 mAU/mL; both P less than .0001). When comparing HCC patients and healthy controls, PIVKA-II was markedly more sensitive than AFP (83.9% vs 64.3%, respectively), and somewhat more specific (91.5% vs 84.7%). Compared with measuring AFP alone, measuring both PIVKA-II and AFP demonstrated much greater sensitivity (81.95%) and slightly greater specificity (89.3%).

Study details: The researchers used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) to measure serum PIVKA-II levels in 168 patients with HCC, 150 patients with benign liver disease, and 153 healthy controls.

Disclosures: Funding sources were described as inapplicable. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Feng H et al. BMC Cancer. 2021 Apr 13. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08138-3

Key clinical point: Increased levels of prothrombin induced by vitamin K deficiency or antagonist- II (PIVKA-II) identified patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Median PIVKA-II serum levels were significantly higher in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (181.50 mAU/mL) vs patients with benign (noncancerous) liver disease (28.60 mAU/mL) or healthy controls (21.82 mAU/mL; both P less than .0001). When comparing HCC patients and healthy controls, PIVKA-II was markedly more sensitive than AFP (83.9% vs 64.3%, respectively), and somewhat more specific (91.5% vs 84.7%). Compared with measuring AFP alone, measuring both PIVKA-II and AFP demonstrated much greater sensitivity (81.95%) and slightly greater specificity (89.3%).

Study details: The researchers used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) to measure serum PIVKA-II levels in 168 patients with HCC, 150 patients with benign liver disease, and 153 healthy controls.

Disclosures: Funding sources were described as inapplicable. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Feng H et al. BMC Cancer. 2021 Apr 13. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08138-3

Key clinical point: Increased levels of prothrombin induced by vitamin K deficiency or antagonist- II (PIVKA-II) identified patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Median PIVKA-II serum levels were significantly higher in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (181.50 mAU/mL) vs patients with benign (noncancerous) liver disease (28.60 mAU/mL) or healthy controls (21.82 mAU/mL; both P less than .0001). When comparing HCC patients and healthy controls, PIVKA-II was markedly more sensitive than AFP (83.9% vs 64.3%, respectively), and somewhat more specific (91.5% vs 84.7%). Compared with measuring AFP alone, measuring both PIVKA-II and AFP demonstrated much greater sensitivity (81.95%) and slightly greater specificity (89.3%).

Study details: The researchers used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) to measure serum PIVKA-II levels in 168 patients with HCC, 150 patients with benign liver disease, and 153 healthy controls.

Disclosures: Funding sources were described as inapplicable. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Feng H et al. BMC Cancer. 2021 Apr 13. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08138-3

Spleen stiffness tied to HCC after HCV treatment

Key clinical point: Spleen stiffness, a measure of portal hypertension, was a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) among patients with advanced liver disease whose chronic hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) was successfully treated with direct-acting antivirals (DAA).

Major finding: The incidence of HCC was 14% over a median of 41.5 months of follow-up. Six months after successful DAA treatment, spleen stiffness greater than 42 kPa was associated with a small but statistically significant increase in risk for HCC (hazard ratio, 1.025). Among patients whose liver stiffness exceeded 10 kPa, increased spleen stiffness was a risk factor for HCC, but any additional increase in liver stiffness (10-20 kPa vs >20 kPa) was not.

Study details: This was a single-center retrospective study of 140 patients with advanced chronic liver disease whose HCV was successfully treated with DAA. Liver and spleen stiffness were measured at baseline and 6 months after end of treatment.

Disclosures: The researchers reported receiving no funding for the study and stated that they had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Dajti E et al. JHEP Rep. 2021 Apr 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100289

Key clinical point: Spleen stiffness, a measure of portal hypertension, was a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) among patients with advanced liver disease whose chronic hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) was successfully treated with direct-acting antivirals (DAA).

Major finding: The incidence of HCC was 14% over a median of 41.5 months of follow-up. Six months after successful DAA treatment, spleen stiffness greater than 42 kPa was associated with a small but statistically significant increase in risk for HCC (hazard ratio, 1.025). Among patients whose liver stiffness exceeded 10 kPa, increased spleen stiffness was a risk factor for HCC, but any additional increase in liver stiffness (10-20 kPa vs >20 kPa) was not.

Study details: This was a single-center retrospective study of 140 patients with advanced chronic liver disease whose HCV was successfully treated with DAA. Liver and spleen stiffness were measured at baseline and 6 months after end of treatment.

Disclosures: The researchers reported receiving no funding for the study and stated that they had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Dajti E et al. JHEP Rep. 2021 Apr 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100289

Key clinical point: Spleen stiffness, a measure of portal hypertension, was a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) among patients with advanced liver disease whose chronic hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) was successfully treated with direct-acting antivirals (DAA).

Major finding: The incidence of HCC was 14% over a median of 41.5 months of follow-up. Six months after successful DAA treatment, spleen stiffness greater than 42 kPa was associated with a small but statistically significant increase in risk for HCC (hazard ratio, 1.025). Among patients whose liver stiffness exceeded 10 kPa, increased spleen stiffness was a risk factor for HCC, but any additional increase in liver stiffness (10-20 kPa vs >20 kPa) was not.

Study details: This was a single-center retrospective study of 140 patients with advanced chronic liver disease whose HCV was successfully treated with DAA. Liver and spleen stiffness were measured at baseline and 6 months after end of treatment.

Disclosures: The researchers reported receiving no funding for the study and stated that they had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Dajti E et al. JHEP Rep. 2021 Apr 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100289

Hepatis D virus linked to liver cancer in patients with chronic HBV

Key clinical point: Consider testing for hepatitis D virus in patients receiving nucleoside/nucleotide analogues (NA) for chronic hepatitis B virus infection (HBV).

Major finding: Prevalences of anti-HDV and HDV RNA positivity were 2.3% and 1.0%, respectively. Five-year cumulative rates of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were 22.2% among patients with detectable HDV RNA vs 7.3% among patients with undetectable HDV RNA (P = .01).

Study details: This was a single-center retrospective study of 1,349 patients receiving NA for chronic HBV.

Disclosures: The Center for Liquid Biopsy, Center for Cancer Research, Cohort Research Center, Kaohsiung Medical University, and Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital provided funding. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Abbott, BMS, Gilead, Merck, AbbVie, Roche, and IPSEN. The other investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Jang T-Y et al. Sci Rep. 2021 Apr 14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87679-w

Key clinical point: Consider testing for hepatitis D virus in patients receiving nucleoside/nucleotide analogues (NA) for chronic hepatitis B virus infection (HBV).

Major finding: Prevalences of anti-HDV and HDV RNA positivity were 2.3% and 1.0%, respectively. Five-year cumulative rates of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were 22.2% among patients with detectable HDV RNA vs 7.3% among patients with undetectable HDV RNA (P = .01).

Study details: This was a single-center retrospective study of 1,349 patients receiving NA for chronic HBV.

Disclosures: The Center for Liquid Biopsy, Center for Cancer Research, Cohort Research Center, Kaohsiung Medical University, and Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital provided funding. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Abbott, BMS, Gilead, Merck, AbbVie, Roche, and IPSEN. The other investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Jang T-Y et al. Sci Rep. 2021 Apr 14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87679-w

Key clinical point: Consider testing for hepatitis D virus in patients receiving nucleoside/nucleotide analogues (NA) for chronic hepatitis B virus infection (HBV).

Major finding: Prevalences of anti-HDV and HDV RNA positivity were 2.3% and 1.0%, respectively. Five-year cumulative rates of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were 22.2% among patients with detectable HDV RNA vs 7.3% among patients with undetectable HDV RNA (P = .01).

Study details: This was a single-center retrospective study of 1,349 patients receiving NA for chronic HBV.

Disclosures: The Center for Liquid Biopsy, Center for Cancer Research, Cohort Research Center, Kaohsiung Medical University, and Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital provided funding. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to Abbott, BMS, Gilead, Merck, AbbVie, Roche, and IPSEN. The other investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Jang T-Y et al. Sci Rep. 2021 Apr 14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87679-w

GINS4 oncogene linked to higher-grade liver cancer, worse survival

Key clinical point: GINS complex subunit 4 (GINS4) is a prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: GINS4 was overexpressed in HCC. Higher GINS4 expression correlated with higher TNM stage and histologic grade (P less than .0001). Kaplan-Meier survival curves linked higher GINS4 expression with worse overall survival (hazard ratio for death, 1.84; P = .004).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study of 1,084 patients with HCC, as well as patients with hepatic cirrhosis and healthy controls. GINS4 was analyzed by using existing publicly available databases and immunohistochemistry of specimens from 35 of the HCC patients.

Disclosures: The National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Hunan Province Science and Technology plan provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zhang Z et al. Front Oncol. 2021 Mar 25. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.654185

Key clinical point: GINS complex subunit 4 (GINS4) is a prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: GINS4 was overexpressed in HCC. Higher GINS4 expression correlated with higher TNM stage and histologic grade (P less than .0001). Kaplan-Meier survival curves linked higher GINS4 expression with worse overall survival (hazard ratio for death, 1.84; P = .004).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study of 1,084 patients with HCC, as well as patients with hepatic cirrhosis and healthy controls. GINS4 was analyzed by using existing publicly available databases and immunohistochemistry of specimens from 35 of the HCC patients.

Disclosures: The National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Hunan Province Science and Technology plan provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zhang Z et al. Front Oncol. 2021 Mar 25. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.654185

Key clinical point: GINS complex subunit 4 (GINS4) is a prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: GINS4 was overexpressed in HCC. Higher GINS4 expression correlated with higher TNM stage and histologic grade (P less than .0001). Kaplan-Meier survival curves linked higher GINS4 expression with worse overall survival (hazard ratio for death, 1.84; P = .004).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study of 1,084 patients with HCC, as well as patients with hepatic cirrhosis and healthy controls. GINS4 was analyzed by using existing publicly available databases and immunohistochemistry of specimens from 35 of the HCC patients.

Disclosures: The National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Hunan Province Science and Technology plan provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zhang Z et al. Front Oncol. 2021 Mar 25. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.654185

Study eyes lenvatinib combination in unresectable liver cancer

Key clinical point: Compared with lenvatinib alone, triple combination therapy with lenvatinib, toripalimab, and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy appeared to demonstrate acceptable safety and improved survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Median progression-free survival was 11.1 months with triple combination therapy vs 5.1 months with lenvatinib alone (hazard ratio, 0.48; P less than .001). Compared with lenvatinib alone, triple combination therapy was associated with a significantly higher rate of grade 3-4 neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and nausea.

Study details: Findings come from a retrospective study of 157 patients with unresectable HCC, of whom 86 received lenvatinib and 71 received lenvatinib, toripalimab, and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFAX (oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-fluorouracil).

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, National Natural Science Foundation of China, and National Science and Technology Major Project of China. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: He M-K et al. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021 Mar 25. doi: 10.1177/17588359211002720

Key clinical point: Compared with lenvatinib alone, triple combination therapy with lenvatinib, toripalimab, and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy appeared to demonstrate acceptable safety and improved survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Median progression-free survival was 11.1 months with triple combination therapy vs 5.1 months with lenvatinib alone (hazard ratio, 0.48; P less than .001). Compared with lenvatinib alone, triple combination therapy was associated with a significantly higher rate of grade 3-4 neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and nausea.

Study details: Findings come from a retrospective study of 157 patients with unresectable HCC, of whom 86 received lenvatinib and 71 received lenvatinib, toripalimab, and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFAX (oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-fluorouracil).

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, National Natural Science Foundation of China, and National Science and Technology Major Project of China. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: He M-K et al. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021 Mar 25. doi: 10.1177/17588359211002720

Key clinical point: Compared with lenvatinib alone, triple combination therapy with lenvatinib, toripalimab, and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy appeared to demonstrate acceptable safety and improved survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Median progression-free survival was 11.1 months with triple combination therapy vs 5.1 months with lenvatinib alone (hazard ratio, 0.48; P less than .001). Compared with lenvatinib alone, triple combination therapy was associated with a significantly higher rate of grade 3-4 neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and nausea.

Study details: Findings come from a retrospective study of 157 patients with unresectable HCC, of whom 86 received lenvatinib and 71 received lenvatinib, toripalimab, and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFAX (oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-fluorouracil).

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China, National Natural Science Foundation of China, and National Science and Technology Major Project of China. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: He M-K et al. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021 Mar 25. doi: 10.1177/17588359211002720

Physicians’ trust in health care leadership drops in pandemic

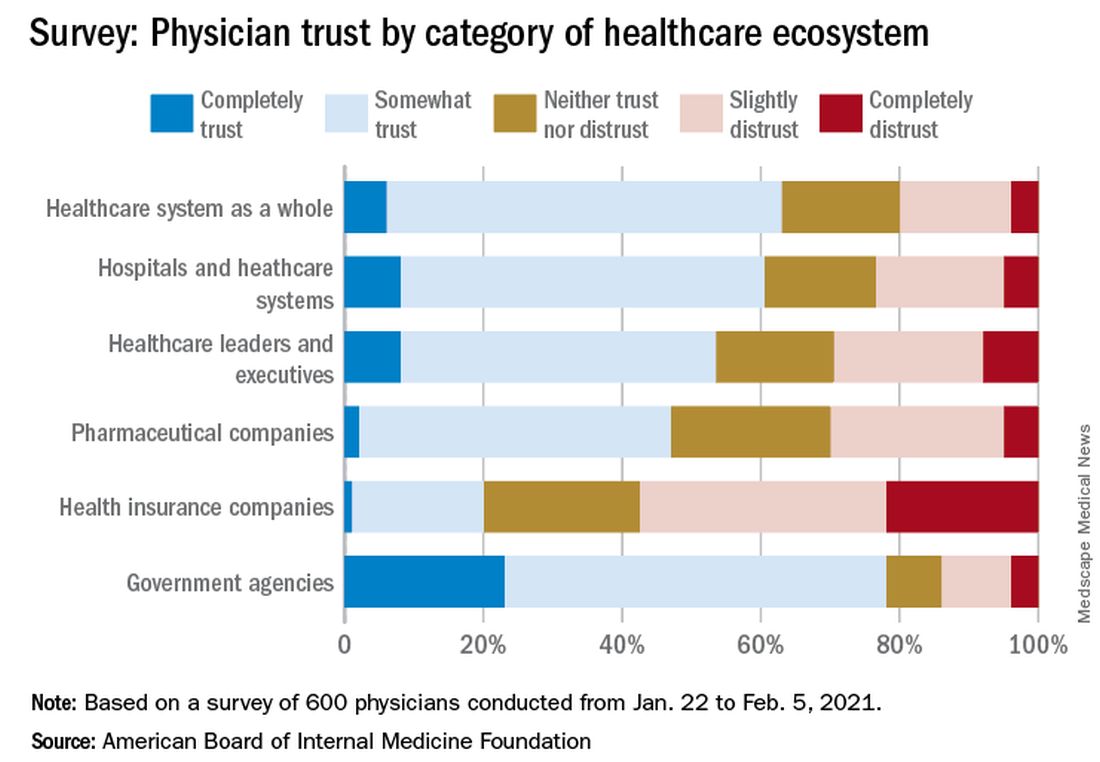

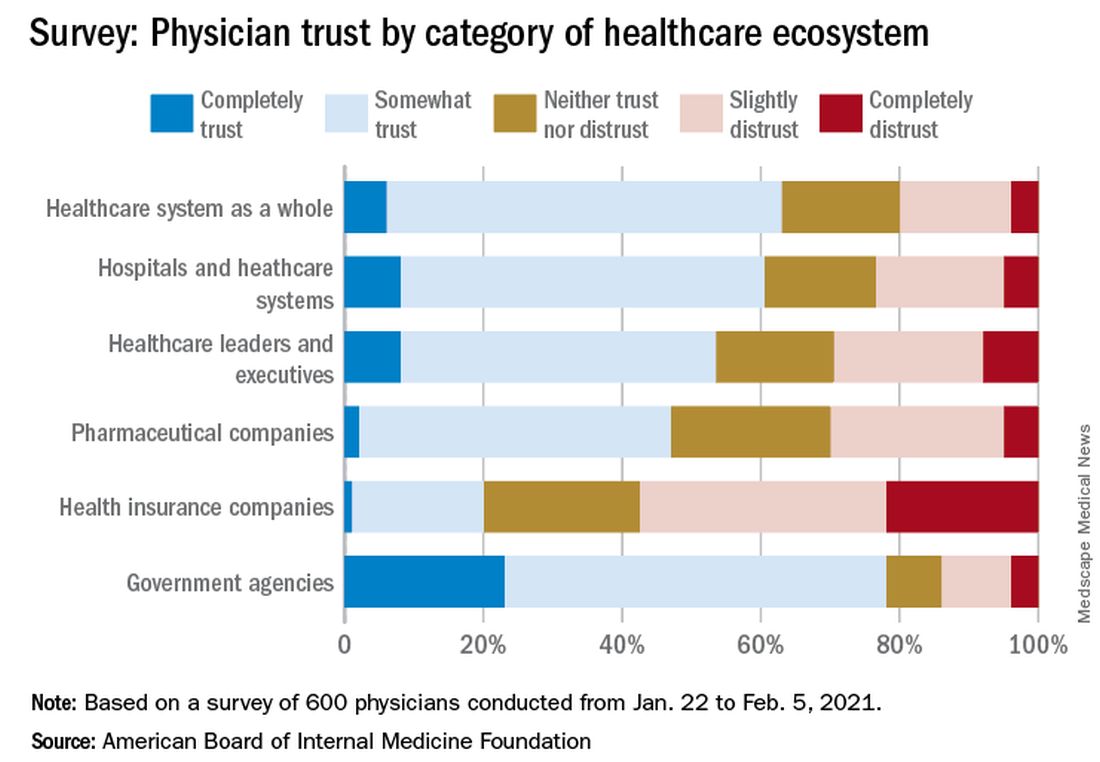

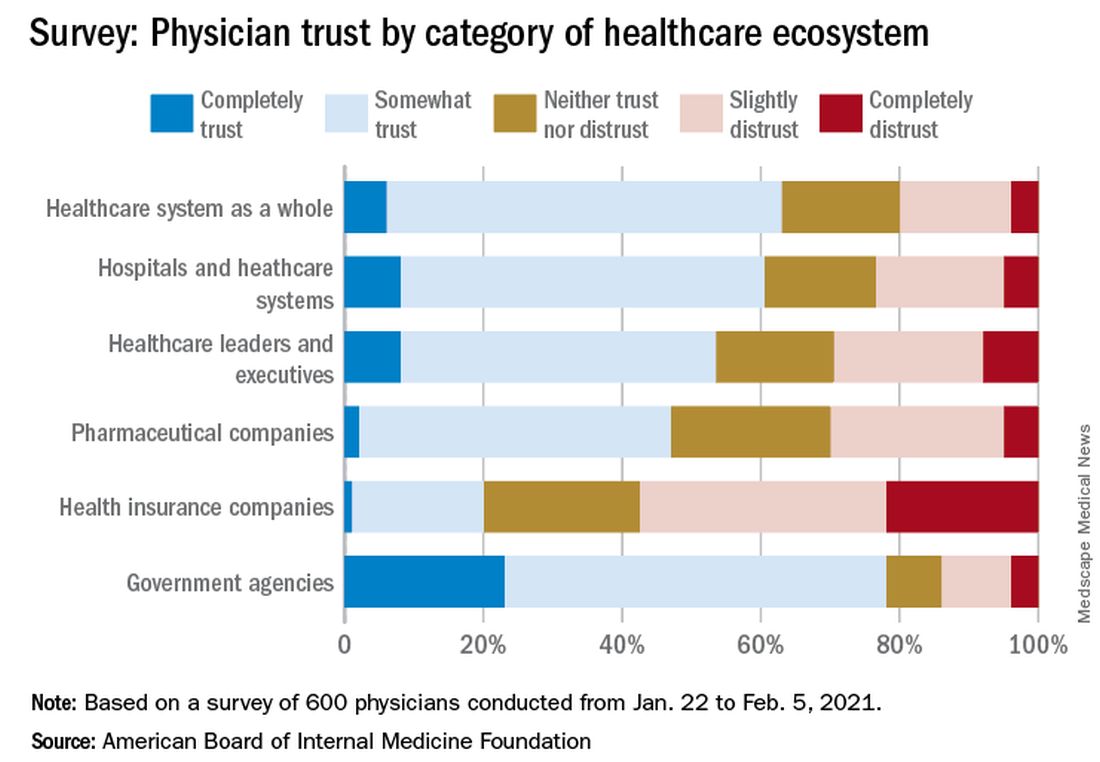

according to a survey conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago on behalf of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation.

Survey results, released May 21, indicate that 30% of physicians say their trust in the U.S. health care system and health care leadership has decreased during the pandemic. Only 18% reported an increase in trust.

Physicians, however, have great trust in their fellow clinicians.

In the survey of 600 physicians, 94% said they trust doctors within their practice; 85% trusted doctors outside of their practice; and 89% trusted nurses. That trust increased during the pandemic, with 41% saying their trust in fellow physicians rose and 37% saying their trust in nurses did.

In a separate survey, NORC asked patients about their trust in various aspects of health care. Among 2,069 respondents, a wide majority reported that they trust doctors (84%) and nurses (85%), but only 64% trusted the health care system as a whole. One in three consumers (32%) said their trust in the health care system decreased during the pandemic, compared with 11% who said their trust increased.

The ABIM Foundation released the research findings on May 21 as part of Building Trust, a national campaign that aims to boost trust among patients, clinicians, system leaders, researchers, and others.

Richard J. Baron, MD, president and chief executive officer of the ABIM Foundation, said in an interview, “Clearly there’s lower trust in health care organization leaders and executives, and that’s troubling.

“Science by itself is not enough,” he said. “Becoming trustworthy has to be a core project of everybody in health care.”

Deterioration in physicians’ trust during the pandemic comes in part from failed promises of adequate personal protective equipment and some physicians’ loss of income as a result of the crisis, Dr. Baron said.

He added that the vaccine rollout was very uneven and that policies as to which elective procedures could be performed were handled differently in different parts of the country.

He also noted that, early on, transparency was lacking as to how many COVID patients hospitals were treating, which may have contributed to the decrease in trust in the system.

Fear of being known as ‘the COVID hospital’

Hospitals were afraid of being known as “the COVID hospital” and losing patients who were afraid to come there, Dr. Baron said.

He said the COVID-19 epidemic exacerbated problems regarding trust, but that trust has been declining for some time. The Building Trust campaign will focus on solutions in breaches of trust as physicians move increasingly toward being employees of huge systems, according to Dr. Baron.

However, trust works both ways, Dr. Baron notes. Physicians can be champions for their health care system or “throw the system under the bus,” he said.

For example, if a patient complains about the appointment system, clinicians who trust their institutions may say the system usually works and that they will try to make sure the patient has a better experience next time. Clinicians without trust may say they agree that the health care system doesn’t know what it is doing, and patients may further lose confidence when physicians validate their complaint, and patients may then go elsewhere.

78% of patients trust primary care doctor

When asked whether they trust their primary care physician, 78% of patients said yes. However, trust in doctors was higher among people who were older (90%), White (82%), or had high income (89%). Among people reporting lower trust, 25% said their physician spends too little time with them, and 14% said their doctor does not know or listen to them.

The survey shows that government agencies have work to do to earn trust. Responses indicate that 43% of physicians said they have “complete trust” in government health care agencies, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is substantially higher than other parts of the health care system. However, trust in agencies declined for 43% of physician respondents and increased for 21%.

Dhruv Khullar, MD, MPP, of the department of health policy and economics at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, told this news organization the survey results match what he sees anecdotally in medicine – that physicians have been losing trust in the system but not in their colleagues.

He said the sample size of 600 is enough to be influential, though he said he would like to know the response rate, which was not calculated for this survey.

He added that, in large part, physicians’ lack of trust in their systems may come from generally being asked to see more patients and to meet more metrics during the same or shorter periods.

Physicians’ lack of trust in the system can have significant consequences, he said. It can lead to burnout, which has been linked with poorer quality of care and physician turnover, he noted.

COVID-19 led some physicians to wonder whether their system had their best interests at heart, insofar as access to adequate medicines and supplies as well as emotional support were inconsistent, Dr. Khullar said.

He said that to regain trust health care systems need to ask themselves questions in three areas. The first is whether their goals are focused on the best interest of the organization or the best interest of the patient.

“Next is competency,” Dr. Khullar said. “Maybe your motives are right, but are you able to deliver? Are you delivering a good product, whether clinical services or something else?”

The third area is transparency, he said. “Are you going to be honest and forthright in what we’re doing and where we’re going?”

Caroline Pearson, senior vice president of health care strategy for NORC, said the emailed survey was conducted between Dec. 29, 2020, and Feb. 5, 2021, with a health care survey partner that maintains a nationwide panel of physicians across specialties.

She said this report is fairly novel insofar as surveys are more typically conducted regarding patients’ trust of their doctors or of the health care system.

Ms. Pearson said because health care is delivered in teams, understanding the level of trust among the entities helps ensure that care will be delivered effectively and seamlessly with high quality.

“We want our patients to trust our doctors, but we really want doctors to trust each other and trust the hospitals and systems in which they’re working,” she said.

Dr. Baron, Ms. Pearson, and Dr. Khullar report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a survey conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago on behalf of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation.

Survey results, released May 21, indicate that 30% of physicians say their trust in the U.S. health care system and health care leadership has decreased during the pandemic. Only 18% reported an increase in trust.

Physicians, however, have great trust in their fellow clinicians.