User login

CDC: New botulism guidelines focus on mass casualty events

Botulinum toxin is said to be the most lethal substance known. Inhaling just 1-3 nanograms of toxin per kilogram of body mass constitutes a lethal dose.

The CDC has been working on these guidelines since 2015, initially establishing a technical development group and steering committee to prioritize topics for review and make recommendations. Since then, the agency published 15 systematic reviews in Clinical Infectious Diseases early in 2018. The reviews addressed the recognition of botulism clinically, treatment with botulinum antitoxin, and complications from that treatment. They also looked at the epidemiology of botulism outbreaks and botulism in the special populations of vulnerable pediatric and pregnant patients.

In 2016, the CDC held two extended forums and convened a workshop with 72 experts. In addition to the more standard topics of diagnosis and treatment, attention was given to crisis standards of care, caring for multiple patients at once, and ethical considerations in management.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, said in an interview that the new guidance “was really specific [and] was meant to address the gap in guidance for mass casualty settings.”

While clinicians are used to focusing on an individual patient, in times of crises, with multiple patients from a food-borne outbreak or a bioterrorism attack, the focus must shift to the population rather than the individual. The workshop explored issues of triaging, adding beds, and caring for patients when a hospital is overwhelmed with an acute influx of severely ill patients.

Such a mass casualty event is similar to the stress encountered this past year with COVID-19 patients swamping the hospitals, which had too little oxygen, too few ventilators, and too few staff members to care for the sudden influx of critically ill patients.

Diagnosis

Leslie Edwards, MHS, BSN, a CDC epidemiologist and botulism expert, said that “botulism is rare and [so] could be difficult to diagnose.” The CDC “wanted to highlight some of those key clinical factors” to speed recognition.

Hospitals and health officials are being urged to develop crisis protocols as part of emergency preparedness plans. And clinicians should be able to recognize four major syndromes: botulism from food, wounds, and inhalation, as well as iatrogenic botulism (from exposure via injection of the neurotoxin).

Botulism has a characteristic and unusual pattern of symptoms, which begin with cranial nerve palsies. Then there is typically a descending, symmetric flaccid paralysis. Symptoms might progress to respiratory failure and death. Other critical clues that implicate botulism include a lack of sensory deficits and the absence of pain.

Symptoms are most likely to be mistaken for myasthenia gravis or Guillain-Barré syndrome, but the latter has an ascending paralysis. Cranial nerve involvement can present as blurred vision, ptosis (drooping lid), diplopia (double vision), ophthalmoplegia (weak eye muscles), or difficulty with speech and swallowing. Shortness of breath and abdominal discomfort can also occur. Respiratory failure may occur from weakness or paralysis of cranial nerves. Cranial nerve signs and symptoms in the absence of fever, along with a descending paralysis, should strongly suggest the diagnosis.

With food-borne botulism, vomiting occurs in half the patients. Improperly sterilized home-canned food is the major risk factor. While the toxin is rapidly destroyed by heat, the bacterial spores are not. Wound botulism is most commonly associated with the injection of drugs, particularly black tar heroin.

Dr. Edwards stressed that “time is of the essence when it comes to botulism diagnostics and treating. Timely administration of the botulism antitoxin early in the course of illness can arrest the progression of paralysis and possibly avert the need for intubation or ventilation.”

It’s essential to note that botulism is an urgent diagnosis that has to be made on clinical grounds. Lab assays for botulinum neurotoxins take too long and are only conducted in public health laboratories. The decision to use antitoxin must not be delayed to wait for confirmation.

Clinicians should immediately contact the local or state health department’s emergency on-call team if botulism is suspected. They will arrange for expert consultation.

Treatment

Botulinum antitoxin is the only specific therapy for this infection. If given early – preferably within 24-48 hours of symptom onset – it can stop the progression of paralysis. But antitoxin will not reverse existing paralysis. If paralysis is still progressing outside of that 24- to 48-hour window, the antitoxin should still provide benefit. The antitoxin is available only through state health departments and a request to the CDC.

Botulism antitoxin is made from horse serum and therefore may cause a variety of allergic reactions. The risk for anaphylaxis is less than 2%, far lower than the mortality from untreated botulism.

While these guidelines have an important focus on triaging and treating mass casualties from botulism, it’s important to note that food-borne outbreaks and prevention issues are covered elsewhere on the CDC site.

Dr. Edwards has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adalja is a consultant for Emergent BioSolutions, which makes the heptavalent botulism antitoxin.

Dr. Stone is an infectious disease specialist and author of “Resilience: One Family’s Story of Hope and Triumph Over Evil” and of “Conducting Clinical Research,” the essential guide to the topic. You can find her at drjudystone.com or on Twitter @drjudystone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Botulinum toxin is said to be the most lethal substance known. Inhaling just 1-3 nanograms of toxin per kilogram of body mass constitutes a lethal dose.

The CDC has been working on these guidelines since 2015, initially establishing a technical development group and steering committee to prioritize topics for review and make recommendations. Since then, the agency published 15 systematic reviews in Clinical Infectious Diseases early in 2018. The reviews addressed the recognition of botulism clinically, treatment with botulinum antitoxin, and complications from that treatment. They also looked at the epidemiology of botulism outbreaks and botulism in the special populations of vulnerable pediatric and pregnant patients.

In 2016, the CDC held two extended forums and convened a workshop with 72 experts. In addition to the more standard topics of diagnosis and treatment, attention was given to crisis standards of care, caring for multiple patients at once, and ethical considerations in management.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, said in an interview that the new guidance “was really specific [and] was meant to address the gap in guidance for mass casualty settings.”

While clinicians are used to focusing on an individual patient, in times of crises, with multiple patients from a food-borne outbreak or a bioterrorism attack, the focus must shift to the population rather than the individual. The workshop explored issues of triaging, adding beds, and caring for patients when a hospital is overwhelmed with an acute influx of severely ill patients.

Such a mass casualty event is similar to the stress encountered this past year with COVID-19 patients swamping the hospitals, which had too little oxygen, too few ventilators, and too few staff members to care for the sudden influx of critically ill patients.

Diagnosis

Leslie Edwards, MHS, BSN, a CDC epidemiologist and botulism expert, said that “botulism is rare and [so] could be difficult to diagnose.” The CDC “wanted to highlight some of those key clinical factors” to speed recognition.

Hospitals and health officials are being urged to develop crisis protocols as part of emergency preparedness plans. And clinicians should be able to recognize four major syndromes: botulism from food, wounds, and inhalation, as well as iatrogenic botulism (from exposure via injection of the neurotoxin).

Botulism has a characteristic and unusual pattern of symptoms, which begin with cranial nerve palsies. Then there is typically a descending, symmetric flaccid paralysis. Symptoms might progress to respiratory failure and death. Other critical clues that implicate botulism include a lack of sensory deficits and the absence of pain.

Symptoms are most likely to be mistaken for myasthenia gravis or Guillain-Barré syndrome, but the latter has an ascending paralysis. Cranial nerve involvement can present as blurred vision, ptosis (drooping lid), diplopia (double vision), ophthalmoplegia (weak eye muscles), or difficulty with speech and swallowing. Shortness of breath and abdominal discomfort can also occur. Respiratory failure may occur from weakness or paralysis of cranial nerves. Cranial nerve signs and symptoms in the absence of fever, along with a descending paralysis, should strongly suggest the diagnosis.

With food-borne botulism, vomiting occurs in half the patients. Improperly sterilized home-canned food is the major risk factor. While the toxin is rapidly destroyed by heat, the bacterial spores are not. Wound botulism is most commonly associated with the injection of drugs, particularly black tar heroin.

Dr. Edwards stressed that “time is of the essence when it comes to botulism diagnostics and treating. Timely administration of the botulism antitoxin early in the course of illness can arrest the progression of paralysis and possibly avert the need for intubation or ventilation.”

It’s essential to note that botulism is an urgent diagnosis that has to be made on clinical grounds. Lab assays for botulinum neurotoxins take too long and are only conducted in public health laboratories. The decision to use antitoxin must not be delayed to wait for confirmation.

Clinicians should immediately contact the local or state health department’s emergency on-call team if botulism is suspected. They will arrange for expert consultation.

Treatment

Botulinum antitoxin is the only specific therapy for this infection. If given early – preferably within 24-48 hours of symptom onset – it can stop the progression of paralysis. But antitoxin will not reverse existing paralysis. If paralysis is still progressing outside of that 24- to 48-hour window, the antitoxin should still provide benefit. The antitoxin is available only through state health departments and a request to the CDC.

Botulism antitoxin is made from horse serum and therefore may cause a variety of allergic reactions. The risk for anaphylaxis is less than 2%, far lower than the mortality from untreated botulism.

While these guidelines have an important focus on triaging and treating mass casualties from botulism, it’s important to note that food-borne outbreaks and prevention issues are covered elsewhere on the CDC site.

Dr. Edwards has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adalja is a consultant for Emergent BioSolutions, which makes the heptavalent botulism antitoxin.

Dr. Stone is an infectious disease specialist and author of “Resilience: One Family’s Story of Hope and Triumph Over Evil” and of “Conducting Clinical Research,” the essential guide to the topic. You can find her at drjudystone.com or on Twitter @drjudystone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Botulinum toxin is said to be the most lethal substance known. Inhaling just 1-3 nanograms of toxin per kilogram of body mass constitutes a lethal dose.

The CDC has been working on these guidelines since 2015, initially establishing a technical development group and steering committee to prioritize topics for review and make recommendations. Since then, the agency published 15 systematic reviews in Clinical Infectious Diseases early in 2018. The reviews addressed the recognition of botulism clinically, treatment with botulinum antitoxin, and complications from that treatment. They also looked at the epidemiology of botulism outbreaks and botulism in the special populations of vulnerable pediatric and pregnant patients.

In 2016, the CDC held two extended forums and convened a workshop with 72 experts. In addition to the more standard topics of diagnosis and treatment, attention was given to crisis standards of care, caring for multiple patients at once, and ethical considerations in management.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, said in an interview that the new guidance “was really specific [and] was meant to address the gap in guidance for mass casualty settings.”

While clinicians are used to focusing on an individual patient, in times of crises, with multiple patients from a food-borne outbreak or a bioterrorism attack, the focus must shift to the population rather than the individual. The workshop explored issues of triaging, adding beds, and caring for patients when a hospital is overwhelmed with an acute influx of severely ill patients.

Such a mass casualty event is similar to the stress encountered this past year with COVID-19 patients swamping the hospitals, which had too little oxygen, too few ventilators, and too few staff members to care for the sudden influx of critically ill patients.

Diagnosis

Leslie Edwards, MHS, BSN, a CDC epidemiologist and botulism expert, said that “botulism is rare and [so] could be difficult to diagnose.” The CDC “wanted to highlight some of those key clinical factors” to speed recognition.

Hospitals and health officials are being urged to develop crisis protocols as part of emergency preparedness plans. And clinicians should be able to recognize four major syndromes: botulism from food, wounds, and inhalation, as well as iatrogenic botulism (from exposure via injection of the neurotoxin).

Botulism has a characteristic and unusual pattern of symptoms, which begin with cranial nerve palsies. Then there is typically a descending, symmetric flaccid paralysis. Symptoms might progress to respiratory failure and death. Other critical clues that implicate botulism include a lack of sensory deficits and the absence of pain.

Symptoms are most likely to be mistaken for myasthenia gravis or Guillain-Barré syndrome, but the latter has an ascending paralysis. Cranial nerve involvement can present as blurred vision, ptosis (drooping lid), diplopia (double vision), ophthalmoplegia (weak eye muscles), or difficulty with speech and swallowing. Shortness of breath and abdominal discomfort can also occur. Respiratory failure may occur from weakness or paralysis of cranial nerves. Cranial nerve signs and symptoms in the absence of fever, along with a descending paralysis, should strongly suggest the diagnosis.

With food-borne botulism, vomiting occurs in half the patients. Improperly sterilized home-canned food is the major risk factor. While the toxin is rapidly destroyed by heat, the bacterial spores are not. Wound botulism is most commonly associated with the injection of drugs, particularly black tar heroin.

Dr. Edwards stressed that “time is of the essence when it comes to botulism diagnostics and treating. Timely administration of the botulism antitoxin early in the course of illness can arrest the progression of paralysis and possibly avert the need for intubation or ventilation.”

It’s essential to note that botulism is an urgent diagnosis that has to be made on clinical grounds. Lab assays for botulinum neurotoxins take too long and are only conducted in public health laboratories. The decision to use antitoxin must not be delayed to wait for confirmation.

Clinicians should immediately contact the local or state health department’s emergency on-call team if botulism is suspected. They will arrange for expert consultation.

Treatment

Botulinum antitoxin is the only specific therapy for this infection. If given early – preferably within 24-48 hours of symptom onset – it can stop the progression of paralysis. But antitoxin will not reverse existing paralysis. If paralysis is still progressing outside of that 24- to 48-hour window, the antitoxin should still provide benefit. The antitoxin is available only through state health departments and a request to the CDC.

Botulism antitoxin is made from horse serum and therefore may cause a variety of allergic reactions. The risk for anaphylaxis is less than 2%, far lower than the mortality from untreated botulism.

While these guidelines have an important focus on triaging and treating mass casualties from botulism, it’s important to note that food-borne outbreaks and prevention issues are covered elsewhere on the CDC site.

Dr. Edwards has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adalja is a consultant for Emergent BioSolutions, which makes the heptavalent botulism antitoxin.

Dr. Stone is an infectious disease specialist and author of “Resilience: One Family’s Story of Hope and Triumph Over Evil” and of “Conducting Clinical Research,” the essential guide to the topic. You can find her at drjudystone.com or on Twitter @drjudystone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prediabetes linked to higher CVD and CKD rates

in a study of nearly 337,000 people included in the UK Biobank database.

The findings suggest that people with prediabetes have “heightened risk even without progression to type 2 diabetes,” Michael C. Honigberg, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

“Hemoglobin A1c may be better considered as a continuous measure of risk rather than dichotomized” as either less than 6.5%, or 6.5% or higher, the usual threshold defining people with type 2 diabetes, said Dr. Honigberg, a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

‘Prediabetes is not a benign entity’

“Our findings reinforce the notion that A1c represents a continuum of risk, with elevated risks observed, especially for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [ASCVD], at levels where some clinicians wouldn’t think twice about them. Prediabetes is not a benign entity in the middle-aged population we studied,” Dr. Honigberg said in an interview. “Risks are higher in individuals with type 2 diabetes,” he stressed, “however, prediabetes is so much more common that it appears to confer similar cardio, renal, and metabolic risks at a population level.”

Results from prior observational studies also showed elevated incidence rate of cardiovascular disease events in people with prediabetes, including a 2010 report based on data from about 11,000 U.S. residents, and in a more recent meta-analysis of 129 studies involving more than 10 million people. The new report by Dr. Honigberg “is the first to comprehensively evaluate diverse cardio-renal-metabolic outcomes across a range of A1c levels using a very large, contemporary database,” he noted. In addition, most prior reports did not include chronic kidney disease as an examined outcome.

The primary endpoint examined in the new analysis was the combined incidence during a median follow-up of just over 11 years of ASCVD events (coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, or peripheral artery disease), CKD, or heart failure among 336,709 adults in the UK Biobank who at baseline had none of these conditions nor type 1 diabetes.

The vast majority, 82%, were normoglycemic at baseline, based on having an A1c of less than 5.7%; 14% had prediabetes, with an A1c of 5.7%-6.4%; and 4% had type 2 diabetes based on an A1c of at least 6.5% or on insulin treatment. Patients averaged about 57 years of age, slightly more than half were women, and average body mass index was in the overweight category except for those with type 2 diabetes.

The primary endpoint, the combined incidence of ASCVD, CKD, and heart failure, was 24% among those with type 2 diabetes, 14% in those with prediabetes, and 8% in those who were normoglycemic at entry. Concurrently with the report, the results appeared online. Most of these events involved ASCVD, which occurred in 11% of those in the prediabetes subgroup (roughly four-fifths of the events in this subgroup), and in 17% of those with type 2 diabetes (nearly three-quarters of the events in this subgroup).

In an analysis that adjusted for more than a dozen demographic and clinical factors, the presence of prediabetes linked with significant increases in the incidence rate of all three outcomes compared with people who were normoglycemic at baseline. The analysis also identified an A1c level of 5.0% as linked with the lowest incidence of each of the three adverse outcomes. And a very granular analysis suggested that a significantly elevated risk for ASCVD first appeared when A1c levels were in the range of 5.4%-5.7%; a significantly increased incidence of CKD became apparent once A1c was in the range of 6.2%-6.5%; and a significantly increased incidence of heart failure began to manifest once A1c levels reached at least 7.0%.

Need for comprehensive cardiometabolic risk management

The findings “highlight the importance of identifying and comprehensively managing cardiometabolic risk in people with prediabetes, including dietary modification, exercise, weight loss and obesity management, smoking cessation, and attention to hypertension and hypercholesterolemia,” Dr. Honigberg said. While these data cannot address the appropriateness of using novel drug interventions in people with prediabetes, they suggest that people with prediabetes should be the focus of future prevention trials testing agents such as sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

“These data help us discuss risk with patients [with prediabetes], and reemphasize the importance of guideline-directed preventive care,” said Vijay Nambi, MD, PhD, a preventive cardiologist and lipid specialist at Baylor College of Medicine and the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, who was not involved with the study.

An additional analysis reported by Dr. Honigberg examined the risk among people with prediabetes who also were current or former smokers and in the top tertile of the prediabetes study population for systolic blood pressure, high non-HDL cholesterol, and C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation). This very high-risk subgroup of people with prediabetes had incidence rates for ASCVD events and for heart failure that tracked identically to those with type 2 diabetes. However. the incidence rate for CKD in these high-risk people with prediabetes remained below that of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Dr. Honigberg had no disclosures. Dr. Nambi has received research funding from Amgen, Merck, and Roche.

in a study of nearly 337,000 people included in the UK Biobank database.

The findings suggest that people with prediabetes have “heightened risk even without progression to type 2 diabetes,” Michael C. Honigberg, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

“Hemoglobin A1c may be better considered as a continuous measure of risk rather than dichotomized” as either less than 6.5%, or 6.5% or higher, the usual threshold defining people with type 2 diabetes, said Dr. Honigberg, a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

‘Prediabetes is not a benign entity’

“Our findings reinforce the notion that A1c represents a continuum of risk, with elevated risks observed, especially for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [ASCVD], at levels where some clinicians wouldn’t think twice about them. Prediabetes is not a benign entity in the middle-aged population we studied,” Dr. Honigberg said in an interview. “Risks are higher in individuals with type 2 diabetes,” he stressed, “however, prediabetes is so much more common that it appears to confer similar cardio, renal, and metabolic risks at a population level.”

Results from prior observational studies also showed elevated incidence rate of cardiovascular disease events in people with prediabetes, including a 2010 report based on data from about 11,000 U.S. residents, and in a more recent meta-analysis of 129 studies involving more than 10 million people. The new report by Dr. Honigberg “is the first to comprehensively evaluate diverse cardio-renal-metabolic outcomes across a range of A1c levels using a very large, contemporary database,” he noted. In addition, most prior reports did not include chronic kidney disease as an examined outcome.

The primary endpoint examined in the new analysis was the combined incidence during a median follow-up of just over 11 years of ASCVD events (coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, or peripheral artery disease), CKD, or heart failure among 336,709 adults in the UK Biobank who at baseline had none of these conditions nor type 1 diabetes.

The vast majority, 82%, were normoglycemic at baseline, based on having an A1c of less than 5.7%; 14% had prediabetes, with an A1c of 5.7%-6.4%; and 4% had type 2 diabetes based on an A1c of at least 6.5% or on insulin treatment. Patients averaged about 57 years of age, slightly more than half were women, and average body mass index was in the overweight category except for those with type 2 diabetes.

The primary endpoint, the combined incidence of ASCVD, CKD, and heart failure, was 24% among those with type 2 diabetes, 14% in those with prediabetes, and 8% in those who were normoglycemic at entry. Concurrently with the report, the results appeared online. Most of these events involved ASCVD, which occurred in 11% of those in the prediabetes subgroup (roughly four-fifths of the events in this subgroup), and in 17% of those with type 2 diabetes (nearly three-quarters of the events in this subgroup).

In an analysis that adjusted for more than a dozen demographic and clinical factors, the presence of prediabetes linked with significant increases in the incidence rate of all three outcomes compared with people who were normoglycemic at baseline. The analysis also identified an A1c level of 5.0% as linked with the lowest incidence of each of the three adverse outcomes. And a very granular analysis suggested that a significantly elevated risk for ASCVD first appeared when A1c levels were in the range of 5.4%-5.7%; a significantly increased incidence of CKD became apparent once A1c was in the range of 6.2%-6.5%; and a significantly increased incidence of heart failure began to manifest once A1c levels reached at least 7.0%.

Need for comprehensive cardiometabolic risk management

The findings “highlight the importance of identifying and comprehensively managing cardiometabolic risk in people with prediabetes, including dietary modification, exercise, weight loss and obesity management, smoking cessation, and attention to hypertension and hypercholesterolemia,” Dr. Honigberg said. While these data cannot address the appropriateness of using novel drug interventions in people with prediabetes, they suggest that people with prediabetes should be the focus of future prevention trials testing agents such as sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

“These data help us discuss risk with patients [with prediabetes], and reemphasize the importance of guideline-directed preventive care,” said Vijay Nambi, MD, PhD, a preventive cardiologist and lipid specialist at Baylor College of Medicine and the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, who was not involved with the study.

An additional analysis reported by Dr. Honigberg examined the risk among people with prediabetes who also were current or former smokers and in the top tertile of the prediabetes study population for systolic blood pressure, high non-HDL cholesterol, and C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation). This very high-risk subgroup of people with prediabetes had incidence rates for ASCVD events and for heart failure that tracked identically to those with type 2 diabetes. However. the incidence rate for CKD in these high-risk people with prediabetes remained below that of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Dr. Honigberg had no disclosures. Dr. Nambi has received research funding from Amgen, Merck, and Roche.

in a study of nearly 337,000 people included in the UK Biobank database.

The findings suggest that people with prediabetes have “heightened risk even without progression to type 2 diabetes,” Michael C. Honigberg, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

“Hemoglobin A1c may be better considered as a continuous measure of risk rather than dichotomized” as either less than 6.5%, or 6.5% or higher, the usual threshold defining people with type 2 diabetes, said Dr. Honigberg, a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

‘Prediabetes is not a benign entity’

“Our findings reinforce the notion that A1c represents a continuum of risk, with elevated risks observed, especially for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [ASCVD], at levels where some clinicians wouldn’t think twice about them. Prediabetes is not a benign entity in the middle-aged population we studied,” Dr. Honigberg said in an interview. “Risks are higher in individuals with type 2 diabetes,” he stressed, “however, prediabetes is so much more common that it appears to confer similar cardio, renal, and metabolic risks at a population level.”

Results from prior observational studies also showed elevated incidence rate of cardiovascular disease events in people with prediabetes, including a 2010 report based on data from about 11,000 U.S. residents, and in a more recent meta-analysis of 129 studies involving more than 10 million people. The new report by Dr. Honigberg “is the first to comprehensively evaluate diverse cardio-renal-metabolic outcomes across a range of A1c levels using a very large, contemporary database,” he noted. In addition, most prior reports did not include chronic kidney disease as an examined outcome.

The primary endpoint examined in the new analysis was the combined incidence during a median follow-up of just over 11 years of ASCVD events (coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, or peripheral artery disease), CKD, or heart failure among 336,709 adults in the UK Biobank who at baseline had none of these conditions nor type 1 diabetes.

The vast majority, 82%, were normoglycemic at baseline, based on having an A1c of less than 5.7%; 14% had prediabetes, with an A1c of 5.7%-6.4%; and 4% had type 2 diabetes based on an A1c of at least 6.5% or on insulin treatment. Patients averaged about 57 years of age, slightly more than half were women, and average body mass index was in the overweight category except for those with type 2 diabetes.

The primary endpoint, the combined incidence of ASCVD, CKD, and heart failure, was 24% among those with type 2 diabetes, 14% in those with prediabetes, and 8% in those who were normoglycemic at entry. Concurrently with the report, the results appeared online. Most of these events involved ASCVD, which occurred in 11% of those in the prediabetes subgroup (roughly four-fifths of the events in this subgroup), and in 17% of those with type 2 diabetes (nearly three-quarters of the events in this subgroup).

In an analysis that adjusted for more than a dozen demographic and clinical factors, the presence of prediabetes linked with significant increases in the incidence rate of all three outcomes compared with people who were normoglycemic at baseline. The analysis also identified an A1c level of 5.0% as linked with the lowest incidence of each of the three adverse outcomes. And a very granular analysis suggested that a significantly elevated risk for ASCVD first appeared when A1c levels were in the range of 5.4%-5.7%; a significantly increased incidence of CKD became apparent once A1c was in the range of 6.2%-6.5%; and a significantly increased incidence of heart failure began to manifest once A1c levels reached at least 7.0%.

Need for comprehensive cardiometabolic risk management

The findings “highlight the importance of identifying and comprehensively managing cardiometabolic risk in people with prediabetes, including dietary modification, exercise, weight loss and obesity management, smoking cessation, and attention to hypertension and hypercholesterolemia,” Dr. Honigberg said. While these data cannot address the appropriateness of using novel drug interventions in people with prediabetes, they suggest that people with prediabetes should be the focus of future prevention trials testing agents such as sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

“These data help us discuss risk with patients [with prediabetes], and reemphasize the importance of guideline-directed preventive care,” said Vijay Nambi, MD, PhD, a preventive cardiologist and lipid specialist at Baylor College of Medicine and the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, who was not involved with the study.

An additional analysis reported by Dr. Honigberg examined the risk among people with prediabetes who also were current or former smokers and in the top tertile of the prediabetes study population for systolic blood pressure, high non-HDL cholesterol, and C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation). This very high-risk subgroup of people with prediabetes had incidence rates for ASCVD events and for heart failure that tracked identically to those with type 2 diabetes. However. the incidence rate for CKD in these high-risk people with prediabetes remained below that of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Dr. Honigberg had no disclosures. Dr. Nambi has received research funding from Amgen, Merck, and Roche.

FROM ACC 2021

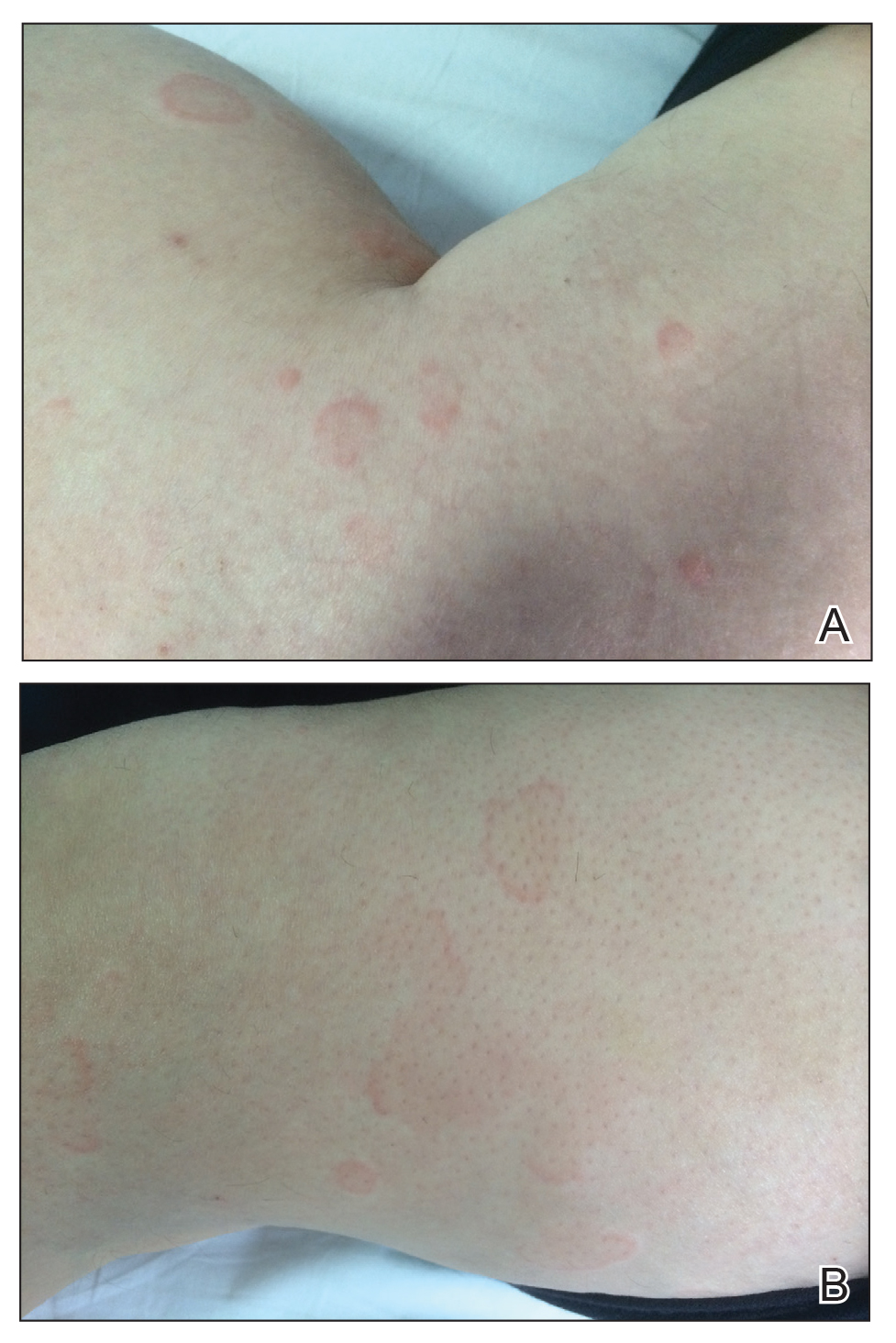

Mohs surgery favorable as monotherapy for early Merkel cell carcinomas

Pittsburgh.

The results compare favorably with the standard treatment approach, wide local excision with or without radiation, which has a local recurrence rate of 4.2%-31.7% because of incomplete excision or false negative margins, said Vitaly Terushkin, MD, a Mohs surgeon who presented the findings of the study, a retrospective chart review, at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Mohs surgery as monotherapy offered “survival at least as good as historical controls treated with wide local excision plus radiation therapy, and because of the superior local control, Mohs surgery may obviate the need for adjuvant radiation and decrease the chance for additional surgery for the treatment of local recurrence,” said Dr. Terushkin, now in practice in the New York City area.

“We hope this data fuel additional studies with larger cohorts to continue to explore the value of Mohs for Merkel cell carcinoma,” he said.

The findings add to a growing body of literature supporting Mohs for many types of rare tumors. “Micrographic surgery or complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin analysis has been shown to be superior to wide local excision in a variety of tumors and clinical scenarios,” said Vishal Patel, MD, assistant professor of dermatology and director of the cutaneous oncology program at George Washington University, Washington.

“When the entire margin is able to be evaluated over random bread-loafed sections, there is growing evidence that this leads to superior outcomes and disease specific mortality,” he said when asked for comment on the study results.

In all, 56 primary Merkel cell carcinomas were treated in the 53 patients from 2001 to 2019; about two-thirds of the patients had stage 1 tumors and the rest stage 2a.

They were treated with Mohs alone, without radiation. Average follow up was 4.6 years, with about a third of patients followed for 5 or more years.

The average age of the patients was 78 years, and just over half were men. In more than half the cases, tumors were located on the head and neck (62.5%), and the mean tumor size was 1.7 cm. Patients were negative for lymphadenopathy and declined lymph node biopsy.

Although there was no local recurrence, defined as tumor reemerging within or adjacent to the surgery site, 7 patients (12.7%) developed in-transit metastases, 13 (23.6%) developed nodal metastases, and 3 developed distant metastases.

The 5-year disease-specific survival rate was 91.2% for stage 1 and 68.6% for stage 2a patients, which compared favorably with historical controls treated with wide local excision with or without radiation, with reported 5-year disease-specific survival rates of 81%-87% for stage 1 disease and 63%-67% for stage 2. Although radiation wasn’t used in the study, Dr. Patel noted that more investigation is needed about the role of adjuvant radiation therapy after Mohs surgery “given recent publications showing improved outcomes in patients with narrow margin excision and postoperative radiation therapy.”

No external funding of the study was reported. Dr. Terushkin had no disclosures. Dr. Patel is a consultant for Sanofi, Regeneron, and Almirall.

Pittsburgh.

The results compare favorably with the standard treatment approach, wide local excision with or without radiation, which has a local recurrence rate of 4.2%-31.7% because of incomplete excision or false negative margins, said Vitaly Terushkin, MD, a Mohs surgeon who presented the findings of the study, a retrospective chart review, at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Mohs surgery as monotherapy offered “survival at least as good as historical controls treated with wide local excision plus radiation therapy, and because of the superior local control, Mohs surgery may obviate the need for adjuvant radiation and decrease the chance for additional surgery for the treatment of local recurrence,” said Dr. Terushkin, now in practice in the New York City area.

“We hope this data fuel additional studies with larger cohorts to continue to explore the value of Mohs for Merkel cell carcinoma,” he said.

The findings add to a growing body of literature supporting Mohs for many types of rare tumors. “Micrographic surgery or complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin analysis has been shown to be superior to wide local excision in a variety of tumors and clinical scenarios,” said Vishal Patel, MD, assistant professor of dermatology and director of the cutaneous oncology program at George Washington University, Washington.

“When the entire margin is able to be evaluated over random bread-loafed sections, there is growing evidence that this leads to superior outcomes and disease specific mortality,” he said when asked for comment on the study results.

In all, 56 primary Merkel cell carcinomas were treated in the 53 patients from 2001 to 2019; about two-thirds of the patients had stage 1 tumors and the rest stage 2a.

They were treated with Mohs alone, without radiation. Average follow up was 4.6 years, with about a third of patients followed for 5 or more years.

The average age of the patients was 78 years, and just over half were men. In more than half the cases, tumors were located on the head and neck (62.5%), and the mean tumor size was 1.7 cm. Patients were negative for lymphadenopathy and declined lymph node biopsy.

Although there was no local recurrence, defined as tumor reemerging within or adjacent to the surgery site, 7 patients (12.7%) developed in-transit metastases, 13 (23.6%) developed nodal metastases, and 3 developed distant metastases.

The 5-year disease-specific survival rate was 91.2% for stage 1 and 68.6% for stage 2a patients, which compared favorably with historical controls treated with wide local excision with or without radiation, with reported 5-year disease-specific survival rates of 81%-87% for stage 1 disease and 63%-67% for stage 2. Although radiation wasn’t used in the study, Dr. Patel noted that more investigation is needed about the role of adjuvant radiation therapy after Mohs surgery “given recent publications showing improved outcomes in patients with narrow margin excision and postoperative radiation therapy.”

No external funding of the study was reported. Dr. Terushkin had no disclosures. Dr. Patel is a consultant for Sanofi, Regeneron, and Almirall.

Pittsburgh.

The results compare favorably with the standard treatment approach, wide local excision with or without radiation, which has a local recurrence rate of 4.2%-31.7% because of incomplete excision or false negative margins, said Vitaly Terushkin, MD, a Mohs surgeon who presented the findings of the study, a retrospective chart review, at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Mohs surgery as monotherapy offered “survival at least as good as historical controls treated with wide local excision plus radiation therapy, and because of the superior local control, Mohs surgery may obviate the need for adjuvant radiation and decrease the chance for additional surgery for the treatment of local recurrence,” said Dr. Terushkin, now in practice in the New York City area.

“We hope this data fuel additional studies with larger cohorts to continue to explore the value of Mohs for Merkel cell carcinoma,” he said.

The findings add to a growing body of literature supporting Mohs for many types of rare tumors. “Micrographic surgery or complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin analysis has been shown to be superior to wide local excision in a variety of tumors and clinical scenarios,” said Vishal Patel, MD, assistant professor of dermatology and director of the cutaneous oncology program at George Washington University, Washington.

“When the entire margin is able to be evaluated over random bread-loafed sections, there is growing evidence that this leads to superior outcomes and disease specific mortality,” he said when asked for comment on the study results.

In all, 56 primary Merkel cell carcinomas were treated in the 53 patients from 2001 to 2019; about two-thirds of the patients had stage 1 tumors and the rest stage 2a.

They were treated with Mohs alone, without radiation. Average follow up was 4.6 years, with about a third of patients followed for 5 or more years.

The average age of the patients was 78 years, and just over half were men. In more than half the cases, tumors were located on the head and neck (62.5%), and the mean tumor size was 1.7 cm. Patients were negative for lymphadenopathy and declined lymph node biopsy.

Although there was no local recurrence, defined as tumor reemerging within or adjacent to the surgery site, 7 patients (12.7%) developed in-transit metastases, 13 (23.6%) developed nodal metastases, and 3 developed distant metastases.

The 5-year disease-specific survival rate was 91.2% for stage 1 and 68.6% for stage 2a patients, which compared favorably with historical controls treated with wide local excision with or without radiation, with reported 5-year disease-specific survival rates of 81%-87% for stage 1 disease and 63%-67% for stage 2. Although radiation wasn’t used in the study, Dr. Patel noted that more investigation is needed about the role of adjuvant radiation therapy after Mohs surgery “given recent publications showing improved outcomes in patients with narrow margin excision and postoperative radiation therapy.”

No external funding of the study was reported. Dr. Terushkin had no disclosures. Dr. Patel is a consultant for Sanofi, Regeneron, and Almirall.

FROM ACMS 2021

Noses can be electronic, and toilets can be smart

Cancer loses … by a nose

Since the human nose is unpredictable at best, we’ve learned to rely on animals for our detailed nozzle needs. But researchers have found the next best thing to man’s best friend to accurately identify cancers.

A team at the University of Pennsylvania has developed an electronic olfaction, or “e-nose,” that has a 95% accuracy rate in distinguishing benign and malignant pancreatic and ovarian cancer cells from a single blood sample. How?

The e-nose system is equipped with nanosensors that are able to detect the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by cells in a blood sample. Not only does this create an opportunity for an easier, noninvasive screening practice, but it’s fast. The e-nose can distinguish VOCs from healthy to cancerous blood cells in 20 minutes or less and is just as effective in picking up on early- and late-stage cancers.

The investigators hope that this innovative technology can pave the way for similar devices with other uses. Thanks to the e-nose, a handheld device is in development that may be able to sniff out the signature odor of people with COVID-19.

That’s one smart schnoz.

Do you think this is a (food) game?

Dieting and eating healthy is tough, even during the best of times, and it has not been the best of times. With all respect to Charles Dickens, it’s been the worst of times, full stop. Millions of people have spent the past year sitting around their homes doing nothing, and it’s only natural that many would let their discipline slide.

Naturally, the solution to unhealthy eating habits is to sit down and play with your phone. No, that’s not the joke, the Food Trainer app, available on all cellular devices near you, is designed to encourage healthy eating by turning it into a game of sorts. When users open the app, they’re presented with images of food, and they’re trained to tap on images of healthy food and pass on images of unhealthy ones. The process takes less than 5 minutes.

It sounds really simple, but in a study of more than 1,000 people, consumption of junk food fell by 1 point on an 8-point scale (ranging from four times per day to zero to one time per month), participants lost about half a kilogram (a little over one pound), and more healthy food was eaten. Those who used the app more regularly, along the lines of 10 times per month or more, saw greater benefits.

The authors did acknowledge that those who used the app more may have been more motivated to lose weight anyway, which perhaps limits the overall benefit, but reviews on Google Play were overall quite positive, and if there’s one great truth in this world, it’s that Internet reviewers are almost impossible to please. So perhaps this app is worth looking into if you’re like the LOTME staff and you’re up at the top end of that 8-point scale. What, pizza is delicious, who wouldn’t eat it four times a day? And you can also get it from your phone!

It’s time for a little mass kickin’

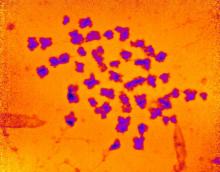

The universe, scientists tell us, is a big place. Really big. Chromosomes, scientists tell us, are small. Really small. But despite this very fundamental difference, the universe and chromosomes share a deep, dark secret: unexplained mass.

This being a medical publication, we’ll start with chromosomes. A group of researchers measured their mass with x-rays for the first time and found that “the 46 chromosomes in each of our cells weigh 242 picograms (trillionths of a gram). This is heavier than we would expect, and, if replicated, points to unexplained excess mass in chromosomes,” Ian K. Robinson, PhD, said in a written statement.

We’re not just talking about a bit of a beer belly here. “The chromosomes were about 20 times heavier than the DNA they contained,” according to the investigators.

Now to the universe. Here’s what CERN, the European Council for Nuclear Research, has to say about the mass of the universe: “Galaxies in our universe … are rotating with such speed that the gravity generated by their observable matter could not possibly hold them together. … which leads scientists to believe that something we cannot see is at work. They think something we have yet to detect directly is giving these galaxies extra mass.”

But wait, there’s more! “The matter we know and that makes up all stars and galaxies only accounts for 5% of the content of the universe!”

So chromosomes are about 20 times heavier than the DNA they contain, and the universe is about 20 times heavier than the matter that can be seen. Interesting.

We are, of course, happy to share this news with our readers, but there is one catch: Don’t tell Neil deGrasse Tyson. He’ll want to reclassify our genetic solar system into 45 chromosomes and one dwarf chromosome.

A photo finish for the Smart Toilet

We know that poop can tell us a lot about our health, but new research by scientists at Duke University is really on a roll. Their Smart Toilet has been created to help people keep an eye on their bowel health. The device takes pictures of poop after it is flushed and can tell whether the consistency is loose, bloody, or normal.

The Smart Toilet can really help people with issues such as irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease by helping them, and their doctors, keep tabs on their poop. “Typically, gastroenterologists have to rely on patient self-reported information about their stool to help determine the cause of their gastrointestinal health issues, which can be very unreliable,” study lead author Deborah Fisher said.

Not many people look too closely at their poop before it’s flushed, so the fecal photos can make a big difference. The Smart Toilet is installed into the pipes of a toilet and does its thing when the toilet is flushed, so there doesn’t seem to be much work on the patient’s end. Other than the, um, you know, usual work from the patient’s end.

Cancer loses … by a nose

Since the human nose is unpredictable at best, we’ve learned to rely on animals for our detailed nozzle needs. But researchers have found the next best thing to man’s best friend to accurately identify cancers.

A team at the University of Pennsylvania has developed an electronic olfaction, or “e-nose,” that has a 95% accuracy rate in distinguishing benign and malignant pancreatic and ovarian cancer cells from a single blood sample. How?

The e-nose system is equipped with nanosensors that are able to detect the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by cells in a blood sample. Not only does this create an opportunity for an easier, noninvasive screening practice, but it’s fast. The e-nose can distinguish VOCs from healthy to cancerous blood cells in 20 minutes or less and is just as effective in picking up on early- and late-stage cancers.

The investigators hope that this innovative technology can pave the way for similar devices with other uses. Thanks to the e-nose, a handheld device is in development that may be able to sniff out the signature odor of people with COVID-19.

That’s one smart schnoz.

Do you think this is a (food) game?

Dieting and eating healthy is tough, even during the best of times, and it has not been the best of times. With all respect to Charles Dickens, it’s been the worst of times, full stop. Millions of people have spent the past year sitting around their homes doing nothing, and it’s only natural that many would let their discipline slide.

Naturally, the solution to unhealthy eating habits is to sit down and play with your phone. No, that’s not the joke, the Food Trainer app, available on all cellular devices near you, is designed to encourage healthy eating by turning it into a game of sorts. When users open the app, they’re presented with images of food, and they’re trained to tap on images of healthy food and pass on images of unhealthy ones. The process takes less than 5 minutes.

It sounds really simple, but in a study of more than 1,000 people, consumption of junk food fell by 1 point on an 8-point scale (ranging from four times per day to zero to one time per month), participants lost about half a kilogram (a little over one pound), and more healthy food was eaten. Those who used the app more regularly, along the lines of 10 times per month or more, saw greater benefits.

The authors did acknowledge that those who used the app more may have been more motivated to lose weight anyway, which perhaps limits the overall benefit, but reviews on Google Play were overall quite positive, and if there’s one great truth in this world, it’s that Internet reviewers are almost impossible to please. So perhaps this app is worth looking into if you’re like the LOTME staff and you’re up at the top end of that 8-point scale. What, pizza is delicious, who wouldn’t eat it four times a day? And you can also get it from your phone!

It’s time for a little mass kickin’

The universe, scientists tell us, is a big place. Really big. Chromosomes, scientists tell us, are small. Really small. But despite this very fundamental difference, the universe and chromosomes share a deep, dark secret: unexplained mass.

This being a medical publication, we’ll start with chromosomes. A group of researchers measured their mass with x-rays for the first time and found that “the 46 chromosomes in each of our cells weigh 242 picograms (trillionths of a gram). This is heavier than we would expect, and, if replicated, points to unexplained excess mass in chromosomes,” Ian K. Robinson, PhD, said in a written statement.

We’re not just talking about a bit of a beer belly here. “The chromosomes were about 20 times heavier than the DNA they contained,” according to the investigators.

Now to the universe. Here’s what CERN, the European Council for Nuclear Research, has to say about the mass of the universe: “Galaxies in our universe … are rotating with such speed that the gravity generated by their observable matter could not possibly hold them together. … which leads scientists to believe that something we cannot see is at work. They think something we have yet to detect directly is giving these galaxies extra mass.”

But wait, there’s more! “The matter we know and that makes up all stars and galaxies only accounts for 5% of the content of the universe!”

So chromosomes are about 20 times heavier than the DNA they contain, and the universe is about 20 times heavier than the matter that can be seen. Interesting.

We are, of course, happy to share this news with our readers, but there is one catch: Don’t tell Neil deGrasse Tyson. He’ll want to reclassify our genetic solar system into 45 chromosomes and one dwarf chromosome.

A photo finish for the Smart Toilet

We know that poop can tell us a lot about our health, but new research by scientists at Duke University is really on a roll. Their Smart Toilet has been created to help people keep an eye on their bowel health. The device takes pictures of poop after it is flushed and can tell whether the consistency is loose, bloody, or normal.

The Smart Toilet can really help people with issues such as irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease by helping them, and their doctors, keep tabs on their poop. “Typically, gastroenterologists have to rely on patient self-reported information about their stool to help determine the cause of their gastrointestinal health issues, which can be very unreliable,” study lead author Deborah Fisher said.

Not many people look too closely at their poop before it’s flushed, so the fecal photos can make a big difference. The Smart Toilet is installed into the pipes of a toilet and does its thing when the toilet is flushed, so there doesn’t seem to be much work on the patient’s end. Other than the, um, you know, usual work from the patient’s end.

Cancer loses … by a nose

Since the human nose is unpredictable at best, we’ve learned to rely on animals for our detailed nozzle needs. But researchers have found the next best thing to man’s best friend to accurately identify cancers.

A team at the University of Pennsylvania has developed an electronic olfaction, or “e-nose,” that has a 95% accuracy rate in distinguishing benign and malignant pancreatic and ovarian cancer cells from a single blood sample. How?

The e-nose system is equipped with nanosensors that are able to detect the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by cells in a blood sample. Not only does this create an opportunity for an easier, noninvasive screening practice, but it’s fast. The e-nose can distinguish VOCs from healthy to cancerous blood cells in 20 minutes or less and is just as effective in picking up on early- and late-stage cancers.

The investigators hope that this innovative technology can pave the way for similar devices with other uses. Thanks to the e-nose, a handheld device is in development that may be able to sniff out the signature odor of people with COVID-19.

That’s one smart schnoz.

Do you think this is a (food) game?

Dieting and eating healthy is tough, even during the best of times, and it has not been the best of times. With all respect to Charles Dickens, it’s been the worst of times, full stop. Millions of people have spent the past year sitting around their homes doing nothing, and it’s only natural that many would let their discipline slide.

Naturally, the solution to unhealthy eating habits is to sit down and play with your phone. No, that’s not the joke, the Food Trainer app, available on all cellular devices near you, is designed to encourage healthy eating by turning it into a game of sorts. When users open the app, they’re presented with images of food, and they’re trained to tap on images of healthy food and pass on images of unhealthy ones. The process takes less than 5 minutes.

It sounds really simple, but in a study of more than 1,000 people, consumption of junk food fell by 1 point on an 8-point scale (ranging from four times per day to zero to one time per month), participants lost about half a kilogram (a little over one pound), and more healthy food was eaten. Those who used the app more regularly, along the lines of 10 times per month or more, saw greater benefits.

The authors did acknowledge that those who used the app more may have been more motivated to lose weight anyway, which perhaps limits the overall benefit, but reviews on Google Play were overall quite positive, and if there’s one great truth in this world, it’s that Internet reviewers are almost impossible to please. So perhaps this app is worth looking into if you’re like the LOTME staff and you’re up at the top end of that 8-point scale. What, pizza is delicious, who wouldn’t eat it four times a day? And you can also get it from your phone!

It’s time for a little mass kickin’

The universe, scientists tell us, is a big place. Really big. Chromosomes, scientists tell us, are small. Really small. But despite this very fundamental difference, the universe and chromosomes share a deep, dark secret: unexplained mass.

This being a medical publication, we’ll start with chromosomes. A group of researchers measured their mass with x-rays for the first time and found that “the 46 chromosomes in each of our cells weigh 242 picograms (trillionths of a gram). This is heavier than we would expect, and, if replicated, points to unexplained excess mass in chromosomes,” Ian K. Robinson, PhD, said in a written statement.

We’re not just talking about a bit of a beer belly here. “The chromosomes were about 20 times heavier than the DNA they contained,” according to the investigators.

Now to the universe. Here’s what CERN, the European Council for Nuclear Research, has to say about the mass of the universe: “Galaxies in our universe … are rotating with such speed that the gravity generated by their observable matter could not possibly hold them together. … which leads scientists to believe that something we cannot see is at work. They think something we have yet to detect directly is giving these galaxies extra mass.”

But wait, there’s more! “The matter we know and that makes up all stars and galaxies only accounts for 5% of the content of the universe!”

So chromosomes are about 20 times heavier than the DNA they contain, and the universe is about 20 times heavier than the matter that can be seen. Interesting.

We are, of course, happy to share this news with our readers, but there is one catch: Don’t tell Neil deGrasse Tyson. He’ll want to reclassify our genetic solar system into 45 chromosomes and one dwarf chromosome.

A photo finish for the Smart Toilet

We know that poop can tell us a lot about our health, but new research by scientists at Duke University is really on a roll. Their Smart Toilet has been created to help people keep an eye on their bowel health. The device takes pictures of poop after it is flushed and can tell whether the consistency is loose, bloody, or normal.

The Smart Toilet can really help people with issues such as irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease by helping them, and their doctors, keep tabs on their poop. “Typically, gastroenterologists have to rely on patient self-reported information about their stool to help determine the cause of their gastrointestinal health issues, which can be very unreliable,” study lead author Deborah Fisher said.

Not many people look too closely at their poop before it’s flushed, so the fecal photos can make a big difference. The Smart Toilet is installed into the pipes of a toilet and does its thing when the toilet is flushed, so there doesn’t seem to be much work on the patient’s end. Other than the, um, you know, usual work from the patient’s end.

Naomi Osaka withdraws from the French Open: When athletes struggle

In 2018, when Naomi Osaka won the U.S. Open by defeating Serena Williams, the trophy ceremony was painful to watch.

Ms. Williams had argued with an umpire over a controversial call, and the ceremony began with the crowd booing. Ms. Osaka, the victor, cried while Ms. Williams comforted her and quietly assured Ms. Osaka that the crowd was not booing at her. When asked how her dream of playing against Ms. Williams compared with the reality, the new champion, looking anything but victorious, responded: “Umm, I’m gonna sort of defer from your question, I’m sorry. I know that everyone was cheering for her, and I’m sorry it had to end like this.”

It was hardly the joyous moment it should have been in this young tennis player’s life.

Ms. Osaka, now 23, entered this year’s French Open as the Women’s Tennis Association’s second-ranked player and as the highest-paid female athlete of all time. She is known for her support of Black Lives Matter. Ms. Osaka announced that she would not be attending press conferences in an Instagram post days before the competition began. “If the organizations think they can keep saying, ‘do press or you’re going to get fined,’ and continue to ignore the mental health of the athletes that are the centerpiece of their cooperation then I just gotta laugh,” Ms. Osaka posted.

She was fined $15,000 on Sunday, May 30, when she did not appear at a press conference after winning her first match. Officials noted that she would be subjected to higher fines and expulsion from the tournament if she did not attend the mandatory media briefings. On June 1, Ms. Osaka withdrew from the French Open and explained her reasons on Instagram in a post where she announced that she has been struggling with depression and social anxiety and did not mean to become a distraction for the competition.

Psychiatrists weigh in

Sue Kim, MD, a psychiatrist who both plays and watches tennis, brought up Ms. Osaka’s resignation for discussion on the Maryland Psychiatric Society’s listserv. “[Ms.] Osaka put out on social media her depression and wanted to have rules reviewed and revised by the governing body of tennis, for future occasions. I feel it is so unfortunate and unfair and I am interested in hearing your opinions.”

Yusuke Sagawa, MD, a psychiatrist and tennis fan, wrote in: “During the COVID-19 pandemic, I rekindled my interest in tennis and I followed what transpired this past weekend. Naomi Osaka is an exceptionally shy and introverted person. I have noted that her speech is somewhat akin to (for lack of a better term) ‘Valley Girl’ talk, and from reading comments on tennis-related blogs, it appears she has garnered a significant amount of hatred as a result. Most of it is along the lines of people feeling her shyness and modesty is simply a masquerade.

“I have also seen YouTube videos of her signing autographs for fans. She is cooperative and pleasant, but clearly uncomfortable around large groups of people.

“Having seen many press conferences after a match,” Dr. Sagawa continued, “tennis journalists have a penchant for asking questions that are either personal or seemingly an attempt to stir up acrimony amongst players. Whatever the case, I truly do believe that this is not some sort of ruse on her part, and I hope that people come to her defense. It is disturbing to hear the comments already coming out from the ‘big names’ in the sport that have mostly been nonsupportive. Fortunately, there have also been a number of her contemporaries who have expressed this support for her.”

In the days following Ms. Osaka’s departure from the French Open, the situation has become more complex. as it is used in these types of communications.

Maryland psychiatrist Erik Roskes, MD, wrote: “I have followed this story from a distance and what strikes me is the intermixing of athleticism – which is presumably why we watch sports – and entertainment, the money-making part of it. The athletes are both athletes and entertainers, and [Ms.] Osaka seems to be unable to fully fulfill the latter part due to her unique traits. But like many, I wonder what if this had been Michael Phelps? Is there a gender issue at play?”

Stephanie Durruthy, MD, added: “[Ms.] Osaka brings complexity to the mental health conversations. There is no one answer to her current plight, but her being a person of color cannot be minimized. She magnified the race conversation in tennis to a higher level.

“When she was new to the Grand Slam scene, her Haitian, Japanese, and Black heritage became an issue with unending curiosity.

“[Ms.] Osaka used her platform during the 2020 U.S. Open to single-handedly highlight Black Lives Matter,” Dr. Durruthy continued. “Afterward, the tennis fans could not avoid seeing her face mask. In each match, she displayed another mask depicting the name of those killed. She described on social media her fears of being a Black person in America. The biases of gender and race are well described in the sports world.”

Lindsay Crouse wrote June 1 in the New York Times: “When Naomi Osaka dropped out of the French Open, after declining to attend media interviews that she said could trigger her anxiety, she wasn’t just protecting her mental health. She was sending a message to the establishment of one of the world’s most elite sports: I will not be controlled. This was a power move – and it packed more punch coming from a young woman of color. When the system hasn’t historically stood for you, why sacrifice yourself to uphold it? Especially when you have the power to change it instead.”

Professional sports are grueling on athletes, both physically and mentally. People will speculate about Ms. Osaka’s motives for refusing to participate in the media briefings that are mandated by her contract. Some will see it as manipulative, others as the desire of a young woman struggling with anxiety and depression to push back against a system that makes few allowances for those who suffer. As psychiatrists, we see how crippling these illnesses can be and admire those who achieve at these superhuman levels, often at the expense of their own well-being.

Dr. Kim, who started the MPS listserv discussion, ended it with: “I feel bad if Naomi Osaka needs to play a mental ‘illness’ card, as opposed to mental ‘wellness’ card.”

Let’s hope that Ms. Osaka’s withdrawal from the French Open sparks more conversation about how to accommodate athletes as they endeavor to meet both the demands of their contracts and when it might be more appropriate to be flexible for those with individual struggles.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “ Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care ” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore.

In 2018, when Naomi Osaka won the U.S. Open by defeating Serena Williams, the trophy ceremony was painful to watch.

Ms. Williams had argued with an umpire over a controversial call, and the ceremony began with the crowd booing. Ms. Osaka, the victor, cried while Ms. Williams comforted her and quietly assured Ms. Osaka that the crowd was not booing at her. When asked how her dream of playing against Ms. Williams compared with the reality, the new champion, looking anything but victorious, responded: “Umm, I’m gonna sort of defer from your question, I’m sorry. I know that everyone was cheering for her, and I’m sorry it had to end like this.”

It was hardly the joyous moment it should have been in this young tennis player’s life.

Ms. Osaka, now 23, entered this year’s French Open as the Women’s Tennis Association’s second-ranked player and as the highest-paid female athlete of all time. She is known for her support of Black Lives Matter. Ms. Osaka announced that she would not be attending press conferences in an Instagram post days before the competition began. “If the organizations think they can keep saying, ‘do press or you’re going to get fined,’ and continue to ignore the mental health of the athletes that are the centerpiece of their cooperation then I just gotta laugh,” Ms. Osaka posted.

She was fined $15,000 on Sunday, May 30, when she did not appear at a press conference after winning her first match. Officials noted that she would be subjected to higher fines and expulsion from the tournament if she did not attend the mandatory media briefings. On June 1, Ms. Osaka withdrew from the French Open and explained her reasons on Instagram in a post where she announced that she has been struggling with depression and social anxiety and did not mean to become a distraction for the competition.

Psychiatrists weigh in

Sue Kim, MD, a psychiatrist who both plays and watches tennis, brought up Ms. Osaka’s resignation for discussion on the Maryland Psychiatric Society’s listserv. “[Ms.] Osaka put out on social media her depression and wanted to have rules reviewed and revised by the governing body of tennis, for future occasions. I feel it is so unfortunate and unfair and I am interested in hearing your opinions.”

Yusuke Sagawa, MD, a psychiatrist and tennis fan, wrote in: “During the COVID-19 pandemic, I rekindled my interest in tennis and I followed what transpired this past weekend. Naomi Osaka is an exceptionally shy and introverted person. I have noted that her speech is somewhat akin to (for lack of a better term) ‘Valley Girl’ talk, and from reading comments on tennis-related blogs, it appears she has garnered a significant amount of hatred as a result. Most of it is along the lines of people feeling her shyness and modesty is simply a masquerade.

“I have also seen YouTube videos of her signing autographs for fans. She is cooperative and pleasant, but clearly uncomfortable around large groups of people.

“Having seen many press conferences after a match,” Dr. Sagawa continued, “tennis journalists have a penchant for asking questions that are either personal or seemingly an attempt to stir up acrimony amongst players. Whatever the case, I truly do believe that this is not some sort of ruse on her part, and I hope that people come to her defense. It is disturbing to hear the comments already coming out from the ‘big names’ in the sport that have mostly been nonsupportive. Fortunately, there have also been a number of her contemporaries who have expressed this support for her.”

In the days following Ms. Osaka’s departure from the French Open, the situation has become more complex. as it is used in these types of communications.

Maryland psychiatrist Erik Roskes, MD, wrote: “I have followed this story from a distance and what strikes me is the intermixing of athleticism – which is presumably why we watch sports – and entertainment, the money-making part of it. The athletes are both athletes and entertainers, and [Ms.] Osaka seems to be unable to fully fulfill the latter part due to her unique traits. But like many, I wonder what if this had been Michael Phelps? Is there a gender issue at play?”

Stephanie Durruthy, MD, added: “[Ms.] Osaka brings complexity to the mental health conversations. There is no one answer to her current plight, but her being a person of color cannot be minimized. She magnified the race conversation in tennis to a higher level.

“When she was new to the Grand Slam scene, her Haitian, Japanese, and Black heritage became an issue with unending curiosity.

“[Ms.] Osaka used her platform during the 2020 U.S. Open to single-handedly highlight Black Lives Matter,” Dr. Durruthy continued. “Afterward, the tennis fans could not avoid seeing her face mask. In each match, she displayed another mask depicting the name of those killed. She described on social media her fears of being a Black person in America. The biases of gender and race are well described in the sports world.”

Lindsay Crouse wrote June 1 in the New York Times: “When Naomi Osaka dropped out of the French Open, after declining to attend media interviews that she said could trigger her anxiety, she wasn’t just protecting her mental health. She was sending a message to the establishment of one of the world’s most elite sports: I will not be controlled. This was a power move – and it packed more punch coming from a young woman of color. When the system hasn’t historically stood for you, why sacrifice yourself to uphold it? Especially when you have the power to change it instead.”

Professional sports are grueling on athletes, both physically and mentally. People will speculate about Ms. Osaka’s motives for refusing to participate in the media briefings that are mandated by her contract. Some will see it as manipulative, others as the desire of a young woman struggling with anxiety and depression to push back against a system that makes few allowances for those who suffer. As psychiatrists, we see how crippling these illnesses can be and admire those who achieve at these superhuman levels, often at the expense of their own well-being.

Dr. Kim, who started the MPS listserv discussion, ended it with: “I feel bad if Naomi Osaka needs to play a mental ‘illness’ card, as opposed to mental ‘wellness’ card.”

Let’s hope that Ms. Osaka’s withdrawal from the French Open sparks more conversation about how to accommodate athletes as they endeavor to meet both the demands of their contracts and when it might be more appropriate to be flexible for those with individual struggles.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “ Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care ” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore.

In 2018, when Naomi Osaka won the U.S. Open by defeating Serena Williams, the trophy ceremony was painful to watch.

Ms. Williams had argued with an umpire over a controversial call, and the ceremony began with the crowd booing. Ms. Osaka, the victor, cried while Ms. Williams comforted her and quietly assured Ms. Osaka that the crowd was not booing at her. When asked how her dream of playing against Ms. Williams compared with the reality, the new champion, looking anything but victorious, responded: “Umm, I’m gonna sort of defer from your question, I’m sorry. I know that everyone was cheering for her, and I’m sorry it had to end like this.”

It was hardly the joyous moment it should have been in this young tennis player’s life.

Ms. Osaka, now 23, entered this year’s French Open as the Women’s Tennis Association’s second-ranked player and as the highest-paid female athlete of all time. She is known for her support of Black Lives Matter. Ms. Osaka announced that she would not be attending press conferences in an Instagram post days before the competition began. “If the organizations think they can keep saying, ‘do press or you’re going to get fined,’ and continue to ignore the mental health of the athletes that are the centerpiece of their cooperation then I just gotta laugh,” Ms. Osaka posted.

She was fined $15,000 on Sunday, May 30, when she did not appear at a press conference after winning her first match. Officials noted that she would be subjected to higher fines and expulsion from the tournament if she did not attend the mandatory media briefings. On June 1, Ms. Osaka withdrew from the French Open and explained her reasons on Instagram in a post where she announced that she has been struggling with depression and social anxiety and did not mean to become a distraction for the competition.

Psychiatrists weigh in

Sue Kim, MD, a psychiatrist who both plays and watches tennis, brought up Ms. Osaka’s resignation for discussion on the Maryland Psychiatric Society’s listserv. “[Ms.] Osaka put out on social media her depression and wanted to have rules reviewed and revised by the governing body of tennis, for future occasions. I feel it is so unfortunate and unfair and I am interested in hearing your opinions.”

Yusuke Sagawa, MD, a psychiatrist and tennis fan, wrote in: “During the COVID-19 pandemic, I rekindled my interest in tennis and I followed what transpired this past weekend. Naomi Osaka is an exceptionally shy and introverted person. I have noted that her speech is somewhat akin to (for lack of a better term) ‘Valley Girl’ talk, and from reading comments on tennis-related blogs, it appears she has garnered a significant amount of hatred as a result. Most of it is along the lines of people feeling her shyness and modesty is simply a masquerade.

“I have also seen YouTube videos of her signing autographs for fans. She is cooperative and pleasant, but clearly uncomfortable around large groups of people.

“Having seen many press conferences after a match,” Dr. Sagawa continued, “tennis journalists have a penchant for asking questions that are either personal or seemingly an attempt to stir up acrimony amongst players. Whatever the case, I truly do believe that this is not some sort of ruse on her part, and I hope that people come to her defense. It is disturbing to hear the comments already coming out from the ‘big names’ in the sport that have mostly been nonsupportive. Fortunately, there have also been a number of her contemporaries who have expressed this support for her.”

In the days following Ms. Osaka’s departure from the French Open, the situation has become more complex. as it is used in these types of communications.