User login

PHM virtual conference promises practical pearls, plus Dr. Fauci

The Pediatric Hospital Medicine annual conference, though virtual in 2021, promises to retain its role as the premier educational event for pediatric hospitalists and other clinicians involved in treating pediatric patients.

The “can’t-miss” session, on August 5, at 6:30 p.m. ET, is a one-on-one discussion between Anthony S. Fauci, MD, and Lee Savio Beers, MD, president of the American Academic of Pediatrics, according to members of the meeting planning committee.

In addition to the conversation between Dr. Beers and Dr. Fauci, this year’s meeting offers a mix of workshops with pointers and pearls to improve practice, keynote and plenary sessions to inform and inspire, and abstract presentations of new research. Three members of the PHM Planning Committee shared their insights on the hot topics, advice for new clinicians, and tips for making the most of this year’s meeting.

Workshops worth watching

“The keynote plenary sessions by Julie Silver, MD, on ‘Accelerating Patient Care and Healthcare Workforce Diversity and Inclusion,’ and by Ilan Alhadeff, MD, on ‘Leading through Adversity’ should inspire even the least enthusiastic among us,” Mirna Giordano, MD, FHM, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, said in an interview. A talk by Nathan T. Chomilo, MD, “will likely prompt reflection on how George Floyd’s death changed us, and how we practice medicine forever.” In addition, “PHM Stories are not to be missed, they are voices that speak loud and move mountains.”

The PHM Stories are concise, narrative talks with minimal use of slides; each PHM Stories session includes three distinct talks and a 15-minute question and answer session. PHM Stories sessions are scheduled for each day of the conference, and topics include “Practicing Medicine While Human: The Secrets Physicians Keep,” by Uchenna Ewulonu, MD; “Finding the Power of the Imposter: How I Learned to Be Exactly the Color I Am, Everywhere I Go,” by Alexandra Coria, MD; and “Purple Butterflies: A Reflection on Why I’m a Pediatric Hospitalist,” by Joanne Mendoza, MD.

“The PHM community has been through a lot in the aftermath of the pandemic,” said Dr. Giordano. “The mini-plenary session on the mental health needs of our patients, and clinical quick-hit sessions on verbal deescalation of the agitated patients and cardiac effects of COVID-19 will likely be not only very popular, but also useful in clinical endeavors. The workshop on how to navigate the adult issues in hospitalized patients will provide the Med-Peds pearls we all wish we heard earlier.”

Although a 75-minute workshop session may seem long, “the workshop choices will offer something for everyone’s taste: education, research, clinical topics, diversity, and advocacy,” Dr. Giordano said. “I suggest that attendees check in advance which sessions will be available after the meeting, so that they prioritize highly interactive sessions like workshops, and that they experience, even if virtual, small group/room gatherings and networking.” There will be time for fun, too, she emphasized, with social sessions “that we hope will break the screen monotony and bring smiles to everyone’s faces.”

For younger clinicians relatively new to practice, Dr. Giordano recommended several workshops for a wealth of advice and guidance, including “New Kids on the Block: Thriving in your First Faculty Position,” “Channeling Your Inner Coach: Techniques to Enhance Clinical Teaching & Feedback,” “Palliative Care Pearls for the Pediatric Hospitalist,” “Perioperative Medicine for Medically Complex Children: Case Studies in Programmatic Approaches,” “The Bare Necessities: Social Determinant of Health Screening for the Hospitalist,” and “Mentorship, Autonomy, and Supervising a PHM Fellow.”

Classic topics and new concepts

“We are so excited to be able to offer a full spectrum of offerings at this year’s virtual meeting,” Yemisi Jones, MD, FHM, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, said in an interview. “We are covering some classic topics that we can’t do without at PHM, such as clinical updates in the management of sick and well newborns; workshops on best practices for educators; as well as the latest in PHM scholarship.” Sessions include “timely topics such as equity for women in medicine with one of our plenary speakers, Julie Silver, MD, and new febrile infant guidelines,” she added.

In particular, the COVID-19 and mental health session will help address clinicians’ evolving understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on hospitalized children, said Dr. Jones. “Attendees can expect practical, timely updates on the current state of the science and ways to improve their practice to provide the best care for our patients.”

Attendees will be able to maximize the virtual conference format by accessing archived recordings, including clinical quick hits, mini-plenaries, and PHM Stories, which can be viewed during the scheduled meeting time or after, Dr. Jones said. “Workshops and abstract presentations will involve real-time interaction with presenters, so would be highest yield to attend during the live meeting. We also encourage all participants to take full advantage of the platform and the various networking opportunities to engage with others in our PHM community.”

For residents and new fellows, Dr. Jones advised making the workshop, “A Whole New World: Tips and Tools to Soar Into Your First Year of Fellowship,” a priority. “For early-career faculty, the ‘New Kids on the Block: Thriving in your First Faculty Position workshop will be a valuable resource.”

Make the meeting content a priority

This year’s conference has an exceptional slate of plenary speakers, Michelle Marks, DO, SFHM, of the Cleveland Clinic said in an interview. In addition to the much-anticipated session on vaccinations, school guidelines, and other topics with Dr. Fauci and Dr. Beers, the sessions on leading through adversity and workforce diversity and inclusion are “important topics to the PHM community and to our greater communities as a whole.”

Dr. Marks also highlighted the value of the COVID-19 and mental health session, as the long-term impact of COVID-19 on mental health of children and adults continues to grab headlines. “From this session specifically, I hope the attendees will gain awareness of the special mental health needs for child during a global disaster like a pandemic, which can be generalized to other situations and gain skills and resources to help meet and advocate for children’s mental health needs.”

For clinicians attending the virtual conference, “The most important strategy is to schedule time off of clinical work for the virtual meeting if you can so you can focus on the content,” said Dr. Marks. “For the longer sessions, it would be very important to block time in your day to fully attend the session, attend in a private space if possible since there will be breakouts with discussion, have your camera on, and engage with the workshop group as much as possible. The virtual format can be challenging because of all the external distractions, so intentional focus is necessary,” to get the most out of the experience.

The mini-plenary session on “The New AAP Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Febrile Infants 8-60 Days Old,” is an important session for all attendees, Dr. Marks said. She also recommended the Clinical Quick Hits sessions for anyone seeking “a diverse array of practical knowledge which can be easily applied to everyday practice.” The Clinical Quick Hits are designed as 35-minute, rapid-fire presentations focused on clinical knowledge. Each of these presentations will focus on the latest updates or evolutions in clinical practice in one area. Some key topics include counseling parents when a child has an abnormal exam finding, assessing pelvic pain in adolescent girls, and preventing venous thromboembolism in the inpatient setting.

“I would also recommend that younger clinicians take in at least one or two workshops or sessions on nonclinical topics to see the breath of content at the meeting and to develop a niche interest for themselves outside of clinical work,” Dr. Marks noted.

Nonclinical sessions at PHM 2021 include workshops on a pilot for a comprehensive LGBTQ+ curriculum, using media tools for public health messaging, and practicing health literacy.

To register for the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2021 virtual conference, visit https://apaevents.regfox.com/phm21-virtual-conference.

Dr. Giordano, Dr. Jones, and Dr. Marks are members of the PHM conference planning committee and had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

The Pediatric Hospital Medicine annual conference, though virtual in 2021, promises to retain its role as the premier educational event for pediatric hospitalists and other clinicians involved in treating pediatric patients.

The “can’t-miss” session, on August 5, at 6:30 p.m. ET, is a one-on-one discussion between Anthony S. Fauci, MD, and Lee Savio Beers, MD, president of the American Academic of Pediatrics, according to members of the meeting planning committee.

In addition to the conversation between Dr. Beers and Dr. Fauci, this year’s meeting offers a mix of workshops with pointers and pearls to improve practice, keynote and plenary sessions to inform and inspire, and abstract presentations of new research. Three members of the PHM Planning Committee shared their insights on the hot topics, advice for new clinicians, and tips for making the most of this year’s meeting.

Workshops worth watching

“The keynote plenary sessions by Julie Silver, MD, on ‘Accelerating Patient Care and Healthcare Workforce Diversity and Inclusion,’ and by Ilan Alhadeff, MD, on ‘Leading through Adversity’ should inspire even the least enthusiastic among us,” Mirna Giordano, MD, FHM, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, said in an interview. A talk by Nathan T. Chomilo, MD, “will likely prompt reflection on how George Floyd’s death changed us, and how we practice medicine forever.” In addition, “PHM Stories are not to be missed, they are voices that speak loud and move mountains.”

The PHM Stories are concise, narrative talks with minimal use of slides; each PHM Stories session includes three distinct talks and a 15-minute question and answer session. PHM Stories sessions are scheduled for each day of the conference, and topics include “Practicing Medicine While Human: The Secrets Physicians Keep,” by Uchenna Ewulonu, MD; “Finding the Power of the Imposter: How I Learned to Be Exactly the Color I Am, Everywhere I Go,” by Alexandra Coria, MD; and “Purple Butterflies: A Reflection on Why I’m a Pediatric Hospitalist,” by Joanne Mendoza, MD.

“The PHM community has been through a lot in the aftermath of the pandemic,” said Dr. Giordano. “The mini-plenary session on the mental health needs of our patients, and clinical quick-hit sessions on verbal deescalation of the agitated patients and cardiac effects of COVID-19 will likely be not only very popular, but also useful in clinical endeavors. The workshop on how to navigate the adult issues in hospitalized patients will provide the Med-Peds pearls we all wish we heard earlier.”

Although a 75-minute workshop session may seem long, “the workshop choices will offer something for everyone’s taste: education, research, clinical topics, diversity, and advocacy,” Dr. Giordano said. “I suggest that attendees check in advance which sessions will be available after the meeting, so that they prioritize highly interactive sessions like workshops, and that they experience, even if virtual, small group/room gatherings and networking.” There will be time for fun, too, she emphasized, with social sessions “that we hope will break the screen monotony and bring smiles to everyone’s faces.”

For younger clinicians relatively new to practice, Dr. Giordano recommended several workshops for a wealth of advice and guidance, including “New Kids on the Block: Thriving in your First Faculty Position,” “Channeling Your Inner Coach: Techniques to Enhance Clinical Teaching & Feedback,” “Palliative Care Pearls for the Pediatric Hospitalist,” “Perioperative Medicine for Medically Complex Children: Case Studies in Programmatic Approaches,” “The Bare Necessities: Social Determinant of Health Screening for the Hospitalist,” and “Mentorship, Autonomy, and Supervising a PHM Fellow.”

Classic topics and new concepts

“We are so excited to be able to offer a full spectrum of offerings at this year’s virtual meeting,” Yemisi Jones, MD, FHM, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, said in an interview. “We are covering some classic topics that we can’t do without at PHM, such as clinical updates in the management of sick and well newborns; workshops on best practices for educators; as well as the latest in PHM scholarship.” Sessions include “timely topics such as equity for women in medicine with one of our plenary speakers, Julie Silver, MD, and new febrile infant guidelines,” she added.

In particular, the COVID-19 and mental health session will help address clinicians’ evolving understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on hospitalized children, said Dr. Jones. “Attendees can expect practical, timely updates on the current state of the science and ways to improve their practice to provide the best care for our patients.”

Attendees will be able to maximize the virtual conference format by accessing archived recordings, including clinical quick hits, mini-plenaries, and PHM Stories, which can be viewed during the scheduled meeting time or after, Dr. Jones said. “Workshops and abstract presentations will involve real-time interaction with presenters, so would be highest yield to attend during the live meeting. We also encourage all participants to take full advantage of the platform and the various networking opportunities to engage with others in our PHM community.”

For residents and new fellows, Dr. Jones advised making the workshop, “A Whole New World: Tips and Tools to Soar Into Your First Year of Fellowship,” a priority. “For early-career faculty, the ‘New Kids on the Block: Thriving in your First Faculty Position workshop will be a valuable resource.”

Make the meeting content a priority

This year’s conference has an exceptional slate of plenary speakers, Michelle Marks, DO, SFHM, of the Cleveland Clinic said in an interview. In addition to the much-anticipated session on vaccinations, school guidelines, and other topics with Dr. Fauci and Dr. Beers, the sessions on leading through adversity and workforce diversity and inclusion are “important topics to the PHM community and to our greater communities as a whole.”

Dr. Marks also highlighted the value of the COVID-19 and mental health session, as the long-term impact of COVID-19 on mental health of children and adults continues to grab headlines. “From this session specifically, I hope the attendees will gain awareness of the special mental health needs for child during a global disaster like a pandemic, which can be generalized to other situations and gain skills and resources to help meet and advocate for children’s mental health needs.”

For clinicians attending the virtual conference, “The most important strategy is to schedule time off of clinical work for the virtual meeting if you can so you can focus on the content,” said Dr. Marks. “For the longer sessions, it would be very important to block time in your day to fully attend the session, attend in a private space if possible since there will be breakouts with discussion, have your camera on, and engage with the workshop group as much as possible. The virtual format can be challenging because of all the external distractions, so intentional focus is necessary,” to get the most out of the experience.

The mini-plenary session on “The New AAP Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Febrile Infants 8-60 Days Old,” is an important session for all attendees, Dr. Marks said. She also recommended the Clinical Quick Hits sessions for anyone seeking “a diverse array of practical knowledge which can be easily applied to everyday practice.” The Clinical Quick Hits are designed as 35-minute, rapid-fire presentations focused on clinical knowledge. Each of these presentations will focus on the latest updates or evolutions in clinical practice in one area. Some key topics include counseling parents when a child has an abnormal exam finding, assessing pelvic pain in adolescent girls, and preventing venous thromboembolism in the inpatient setting.

“I would also recommend that younger clinicians take in at least one or two workshops or sessions on nonclinical topics to see the breath of content at the meeting and to develop a niche interest for themselves outside of clinical work,” Dr. Marks noted.

Nonclinical sessions at PHM 2021 include workshops on a pilot for a comprehensive LGBTQ+ curriculum, using media tools for public health messaging, and practicing health literacy.

To register for the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2021 virtual conference, visit https://apaevents.regfox.com/phm21-virtual-conference.

Dr. Giordano, Dr. Jones, and Dr. Marks are members of the PHM conference planning committee and had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

The Pediatric Hospital Medicine annual conference, though virtual in 2021, promises to retain its role as the premier educational event for pediatric hospitalists and other clinicians involved in treating pediatric patients.

The “can’t-miss” session, on August 5, at 6:30 p.m. ET, is a one-on-one discussion between Anthony S. Fauci, MD, and Lee Savio Beers, MD, president of the American Academic of Pediatrics, according to members of the meeting planning committee.

In addition to the conversation between Dr. Beers and Dr. Fauci, this year’s meeting offers a mix of workshops with pointers and pearls to improve practice, keynote and plenary sessions to inform and inspire, and abstract presentations of new research. Three members of the PHM Planning Committee shared their insights on the hot topics, advice for new clinicians, and tips for making the most of this year’s meeting.

Workshops worth watching

“The keynote plenary sessions by Julie Silver, MD, on ‘Accelerating Patient Care and Healthcare Workforce Diversity and Inclusion,’ and by Ilan Alhadeff, MD, on ‘Leading through Adversity’ should inspire even the least enthusiastic among us,” Mirna Giordano, MD, FHM, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, said in an interview. A talk by Nathan T. Chomilo, MD, “will likely prompt reflection on how George Floyd’s death changed us, and how we practice medicine forever.” In addition, “PHM Stories are not to be missed, they are voices that speak loud and move mountains.”

The PHM Stories are concise, narrative talks with minimal use of slides; each PHM Stories session includes three distinct talks and a 15-minute question and answer session. PHM Stories sessions are scheduled for each day of the conference, and topics include “Practicing Medicine While Human: The Secrets Physicians Keep,” by Uchenna Ewulonu, MD; “Finding the Power of the Imposter: How I Learned to Be Exactly the Color I Am, Everywhere I Go,” by Alexandra Coria, MD; and “Purple Butterflies: A Reflection on Why I’m a Pediatric Hospitalist,” by Joanne Mendoza, MD.

“The PHM community has been through a lot in the aftermath of the pandemic,” said Dr. Giordano. “The mini-plenary session on the mental health needs of our patients, and clinical quick-hit sessions on verbal deescalation of the agitated patients and cardiac effects of COVID-19 will likely be not only very popular, but also useful in clinical endeavors. The workshop on how to navigate the adult issues in hospitalized patients will provide the Med-Peds pearls we all wish we heard earlier.”

Although a 75-minute workshop session may seem long, “the workshop choices will offer something for everyone’s taste: education, research, clinical topics, diversity, and advocacy,” Dr. Giordano said. “I suggest that attendees check in advance which sessions will be available after the meeting, so that they prioritize highly interactive sessions like workshops, and that they experience, even if virtual, small group/room gatherings and networking.” There will be time for fun, too, she emphasized, with social sessions “that we hope will break the screen monotony and bring smiles to everyone’s faces.”

For younger clinicians relatively new to practice, Dr. Giordano recommended several workshops for a wealth of advice and guidance, including “New Kids on the Block: Thriving in your First Faculty Position,” “Channeling Your Inner Coach: Techniques to Enhance Clinical Teaching & Feedback,” “Palliative Care Pearls for the Pediatric Hospitalist,” “Perioperative Medicine for Medically Complex Children: Case Studies in Programmatic Approaches,” “The Bare Necessities: Social Determinant of Health Screening for the Hospitalist,” and “Mentorship, Autonomy, and Supervising a PHM Fellow.”

Classic topics and new concepts

“We are so excited to be able to offer a full spectrum of offerings at this year’s virtual meeting,” Yemisi Jones, MD, FHM, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, said in an interview. “We are covering some classic topics that we can’t do without at PHM, such as clinical updates in the management of sick and well newborns; workshops on best practices for educators; as well as the latest in PHM scholarship.” Sessions include “timely topics such as equity for women in medicine with one of our plenary speakers, Julie Silver, MD, and new febrile infant guidelines,” she added.

In particular, the COVID-19 and mental health session will help address clinicians’ evolving understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on hospitalized children, said Dr. Jones. “Attendees can expect practical, timely updates on the current state of the science and ways to improve their practice to provide the best care for our patients.”

Attendees will be able to maximize the virtual conference format by accessing archived recordings, including clinical quick hits, mini-plenaries, and PHM Stories, which can be viewed during the scheduled meeting time or after, Dr. Jones said. “Workshops and abstract presentations will involve real-time interaction with presenters, so would be highest yield to attend during the live meeting. We also encourage all participants to take full advantage of the platform and the various networking opportunities to engage with others in our PHM community.”

For residents and new fellows, Dr. Jones advised making the workshop, “A Whole New World: Tips and Tools to Soar Into Your First Year of Fellowship,” a priority. “For early-career faculty, the ‘New Kids on the Block: Thriving in your First Faculty Position workshop will be a valuable resource.”

Make the meeting content a priority

This year’s conference has an exceptional slate of plenary speakers, Michelle Marks, DO, SFHM, of the Cleveland Clinic said in an interview. In addition to the much-anticipated session on vaccinations, school guidelines, and other topics with Dr. Fauci and Dr. Beers, the sessions on leading through adversity and workforce diversity and inclusion are “important topics to the PHM community and to our greater communities as a whole.”

Dr. Marks also highlighted the value of the COVID-19 and mental health session, as the long-term impact of COVID-19 on mental health of children and adults continues to grab headlines. “From this session specifically, I hope the attendees will gain awareness of the special mental health needs for child during a global disaster like a pandemic, which can be generalized to other situations and gain skills and resources to help meet and advocate for children’s mental health needs.”

For clinicians attending the virtual conference, “The most important strategy is to schedule time off of clinical work for the virtual meeting if you can so you can focus on the content,” said Dr. Marks. “For the longer sessions, it would be very important to block time in your day to fully attend the session, attend in a private space if possible since there will be breakouts with discussion, have your camera on, and engage with the workshop group as much as possible. The virtual format can be challenging because of all the external distractions, so intentional focus is necessary,” to get the most out of the experience.

The mini-plenary session on “The New AAP Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Febrile Infants 8-60 Days Old,” is an important session for all attendees, Dr. Marks said. She also recommended the Clinical Quick Hits sessions for anyone seeking “a diverse array of practical knowledge which can be easily applied to everyday practice.” The Clinical Quick Hits are designed as 35-minute, rapid-fire presentations focused on clinical knowledge. Each of these presentations will focus on the latest updates or evolutions in clinical practice in one area. Some key topics include counseling parents when a child has an abnormal exam finding, assessing pelvic pain in adolescent girls, and preventing venous thromboembolism in the inpatient setting.

“I would also recommend that younger clinicians take in at least one or two workshops or sessions on nonclinical topics to see the breath of content at the meeting and to develop a niche interest for themselves outside of clinical work,” Dr. Marks noted.

Nonclinical sessions at PHM 2021 include workshops on a pilot for a comprehensive LGBTQ+ curriculum, using media tools for public health messaging, and practicing health literacy.

To register for the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2021 virtual conference, visit https://apaevents.regfox.com/phm21-virtual-conference.

Dr. Giordano, Dr. Jones, and Dr. Marks are members of the PHM conference planning committee and had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Advice on biopsies, workups, and referrals

Over the next 2 months we will dedicate this column to some general tips and pearls from the perspective of a gynecologic oncologist to guide general obstetrician gynecologists in the workup and management of preinvasive or invasive gynecologic diseases. The goal of these recommendations is to minimize misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis and avoid unnecessary or untimely referrals.

Perform biopsy, not Pap smears, on visible cervical and vaginal lesions

The purpose of the Pap smear is to screen asymptomatic patients for cervical dysplasia or microscopic invasive disease. Cytology is an unreliable diagnostic tool for visible, symptomatic lesions in large part because of sampling errors, and the lack of architectural information in cytologic versus histopathologic specimens. Invasive lesions can be mischaracterized as preinvasive on a Pap smear. This can result in delayed diagnosis and unnecessary diagnostic procedures. For example, if a visible, abnormal-appearing, cervical lesion is seen during a routine visit and a Pap smear is performed (rather than a biopsy of the mass), the patient may receive an incorrect preliminary diagnosis of “high-grade dysplasia, carcinoma in situ” as it can be difficult to distinguish invasive carcinoma from carcinoma in situ on cytology. If the patient and provider do not understand the limitations of Pap smears in diagnosing invasive cancers, they may be falsely reassured and possibly delay or abstain from follow-up for an excisional procedure. If she does return for the loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), there might still be unnecessary delays in making referrals and definitive treatment while waiting for results. Radical hysterectomy may not promptly follow because, if performed within 6 weeks of an excisional procedure, it is associated with a significantly higher risk for perioperative complication, and therefore, if the excisional procedure was unnecessary to begin with, there may be additional time lost that need not be.1

Some clinicians avoid biopsy of visible lesions because they are concerned about bleeding complications that might arise in the office. Straightforward strategies to control bleeding are readily available in most gynecology offices, especially those already equipped for procedures such as LEEP and colposcopy. Prior to performing the biopsy, clinicians should ensure that they have supplies such as gauze sponges and ring forceps or packing forceps, silver nitrate, and ferric subsulfate solution (“Monsel’s solution”) close at hand. In the vast majority of cases, direct pressure for 5 minutes with gauze sponges and ferric subsulfate is highly effective at resolving most bleeding from a cervical or vaginal biopsy site. If this does not bring hemostasis, cautery devices or suture can be employed. If all else fails, be prepared to place vaginal packing (always with the insertion of a urinary Foley catheter to prevent urinary retention). In my experience, this is rarely needed.

Wherever possible, visible cervical or vaginal (or vulvar, see below) lesions should be biopsied for histopathology, sampling representative areas of the most concerning portion, in order to minimize misdiagnosis and expedite referral and definitive treatment. For necrotic-appearing lesions I recommend taking multiple samples of the tumor, as necrotic, nonviable tissue can prevent accurate diagnosis of a cancer. In general, Pap smears should be reserved as screening tests for asymptomatic women without visible pathology.

Don’t treat or refer low-grade dysplasia, even if persistent

Increasingly we are understanding that low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract (CIN I, VAIN I, VIN I) is less a precursor for cancer, and more a phenomenon of benign HPV-associated changes.2 This HPV change may be chronically persistent, may require years of observation and serial Pap smears, and may be a general nuisance for the patient. However, current guidelines do not recommend intervention for low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract.2 Interventions to resect these lesions can result in morbidity, including perineal pain, vaginal scarring, and cervical stenosis or insufficiency. Given the extremely low risk for progression to cancer, these morbidities do not outweigh any small potential benefit.

When I am conferring with patients who have chronic low-grade dysplasia I spend a great deal of time exploring their understanding of the diagnosis and its pathophysiology, their fears, and their expectation regarding “success” of treatment. I spend the time educating them that this is a sequela of chronic viral infection that will not be eradicated with local surgical excisions, that their cancer risk and need for surveillance would persist even if surgical intervention were offered, and that the side effects of treatment would outweigh any benefit from the small risk of cancer or high-grade dysplasia.

In summary, the treatment of choice for persistent low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract is comprehensive patient education, not surgical resection or referral to gynecologic oncology.

Repeat sampling if there’s a discordance between imaging and biopsy results

Delay in cancer diagnosis is one of the greatest concerns for front-line gynecology providers. One of the more modifiable strategies to avoid missed or delayed diagnosis is to ensure that there is concordance between clinical findings and testing results. Otherwise said: The results and findings should make sense in aggregate. An example was cited above in which a visible cervical mass demonstrated CIN III on cytologic testing. Another common example is a biopsy result of “scant benign endometrium” in a patient with postmenopausal bleeding and thickened endometrial stripe on ultrasound. In both of these cases there is clear discordance between physical findings and the results of pathology sampling. A pathology report, in all of its black and white certitude, seems like the most reliable source of information. However, always trust your clinical judgment. If the clinical picture is suggesting something far worse than these limited, often random or blind samplings, I recommend repeated or more extensive sampling (for example, dilation and curettage). At the very least, schedule close follow-up with repeated sampling if the symptom or finding persists. The emphasis here is on scheduled follow-up, rather than “p.r.n.,” because a patient who was given a “normal” pathology result to explain her abnormal symptoms may not volunteer that those symptoms are persistent as she may feel that anything sinister was already ruled out. Make certain that you explain the potential for misdiagnosis as the reason for why you would like to see her back shortly to ensure the issue has resolved.

Biopsy vulvar lesions, minimize empiric treatment

Vulvar cancer is notoriously associated with delayed diagnosis. Unfortunately, it is commonplace for gynecologic oncologists to see women who have vulvar cancers that have been empirically treated, sometimes for months or years, with steroids or other topical agents. If a lesion on the vulva is characteristically benign in appearance (such as condyloma or lichen sclerosis), it may be reasonable to start empiric treatment. However, all patients who are treated without biopsy should be rescheduled for a planned follow-up appointment in 2-3 months. If the lesion/area remains unchanged, or worse, the lesion should be biopsied before proceeding with a change in therapy or continued therapy. Once again, don’t rely on patients to return for evaluation if the lesion doesn’t improve. Many patients assume that our first empiric diagnosis is “gospel,” and therefore may not return if the treatment doesn’t work. Meanwhile, providers may assume that patients will know that there is uncertainty in our interpretation and that they will know to report if the initial treatment didn’t work. These assumptions are the recipe for delayed diagnosis. If there is too great a burden on the patient to schedule a return visit because of social or financial reasons then the patient should have a biopsy prior to initiation of treatment. As a rule, empiric treatment is not a good strategy for patients without good access to follow-up.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Sullivan S. et al Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Feb;144(2):294-8.

2. Perkins R .et al J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020 Apr;24(2):102-31.

Over the next 2 months we will dedicate this column to some general tips and pearls from the perspective of a gynecologic oncologist to guide general obstetrician gynecologists in the workup and management of preinvasive or invasive gynecologic diseases. The goal of these recommendations is to minimize misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis and avoid unnecessary or untimely referrals.

Perform biopsy, not Pap smears, on visible cervical and vaginal lesions

The purpose of the Pap smear is to screen asymptomatic patients for cervical dysplasia or microscopic invasive disease. Cytology is an unreliable diagnostic tool for visible, symptomatic lesions in large part because of sampling errors, and the lack of architectural information in cytologic versus histopathologic specimens. Invasive lesions can be mischaracterized as preinvasive on a Pap smear. This can result in delayed diagnosis and unnecessary diagnostic procedures. For example, if a visible, abnormal-appearing, cervical lesion is seen during a routine visit and a Pap smear is performed (rather than a biopsy of the mass), the patient may receive an incorrect preliminary diagnosis of “high-grade dysplasia, carcinoma in situ” as it can be difficult to distinguish invasive carcinoma from carcinoma in situ on cytology. If the patient and provider do not understand the limitations of Pap smears in diagnosing invasive cancers, they may be falsely reassured and possibly delay or abstain from follow-up for an excisional procedure. If she does return for the loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), there might still be unnecessary delays in making referrals and definitive treatment while waiting for results. Radical hysterectomy may not promptly follow because, if performed within 6 weeks of an excisional procedure, it is associated with a significantly higher risk for perioperative complication, and therefore, if the excisional procedure was unnecessary to begin with, there may be additional time lost that need not be.1

Some clinicians avoid biopsy of visible lesions because they are concerned about bleeding complications that might arise in the office. Straightforward strategies to control bleeding are readily available in most gynecology offices, especially those already equipped for procedures such as LEEP and colposcopy. Prior to performing the biopsy, clinicians should ensure that they have supplies such as gauze sponges and ring forceps or packing forceps, silver nitrate, and ferric subsulfate solution (“Monsel’s solution”) close at hand. In the vast majority of cases, direct pressure for 5 minutes with gauze sponges and ferric subsulfate is highly effective at resolving most bleeding from a cervical or vaginal biopsy site. If this does not bring hemostasis, cautery devices or suture can be employed. If all else fails, be prepared to place vaginal packing (always with the insertion of a urinary Foley catheter to prevent urinary retention). In my experience, this is rarely needed.

Wherever possible, visible cervical or vaginal (or vulvar, see below) lesions should be biopsied for histopathology, sampling representative areas of the most concerning portion, in order to minimize misdiagnosis and expedite referral and definitive treatment. For necrotic-appearing lesions I recommend taking multiple samples of the tumor, as necrotic, nonviable tissue can prevent accurate diagnosis of a cancer. In general, Pap smears should be reserved as screening tests for asymptomatic women without visible pathology.

Don’t treat or refer low-grade dysplasia, even if persistent

Increasingly we are understanding that low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract (CIN I, VAIN I, VIN I) is less a precursor for cancer, and more a phenomenon of benign HPV-associated changes.2 This HPV change may be chronically persistent, may require years of observation and serial Pap smears, and may be a general nuisance for the patient. However, current guidelines do not recommend intervention for low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract.2 Interventions to resect these lesions can result in morbidity, including perineal pain, vaginal scarring, and cervical stenosis or insufficiency. Given the extremely low risk for progression to cancer, these morbidities do not outweigh any small potential benefit.

When I am conferring with patients who have chronic low-grade dysplasia I spend a great deal of time exploring their understanding of the diagnosis and its pathophysiology, their fears, and their expectation regarding “success” of treatment. I spend the time educating them that this is a sequela of chronic viral infection that will not be eradicated with local surgical excisions, that their cancer risk and need for surveillance would persist even if surgical intervention were offered, and that the side effects of treatment would outweigh any benefit from the small risk of cancer or high-grade dysplasia.

In summary, the treatment of choice for persistent low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract is comprehensive patient education, not surgical resection or referral to gynecologic oncology.

Repeat sampling if there’s a discordance between imaging and biopsy results

Delay in cancer diagnosis is one of the greatest concerns for front-line gynecology providers. One of the more modifiable strategies to avoid missed or delayed diagnosis is to ensure that there is concordance between clinical findings and testing results. Otherwise said: The results and findings should make sense in aggregate. An example was cited above in which a visible cervical mass demonstrated CIN III on cytologic testing. Another common example is a biopsy result of “scant benign endometrium” in a patient with postmenopausal bleeding and thickened endometrial stripe on ultrasound. In both of these cases there is clear discordance between physical findings and the results of pathology sampling. A pathology report, in all of its black and white certitude, seems like the most reliable source of information. However, always trust your clinical judgment. If the clinical picture is suggesting something far worse than these limited, often random or blind samplings, I recommend repeated or more extensive sampling (for example, dilation and curettage). At the very least, schedule close follow-up with repeated sampling if the symptom or finding persists. The emphasis here is on scheduled follow-up, rather than “p.r.n.,” because a patient who was given a “normal” pathology result to explain her abnormal symptoms may not volunteer that those symptoms are persistent as she may feel that anything sinister was already ruled out. Make certain that you explain the potential for misdiagnosis as the reason for why you would like to see her back shortly to ensure the issue has resolved.

Biopsy vulvar lesions, minimize empiric treatment

Vulvar cancer is notoriously associated with delayed diagnosis. Unfortunately, it is commonplace for gynecologic oncologists to see women who have vulvar cancers that have been empirically treated, sometimes for months or years, with steroids or other topical agents. If a lesion on the vulva is characteristically benign in appearance (such as condyloma or lichen sclerosis), it may be reasonable to start empiric treatment. However, all patients who are treated without biopsy should be rescheduled for a planned follow-up appointment in 2-3 months. If the lesion/area remains unchanged, or worse, the lesion should be biopsied before proceeding with a change in therapy or continued therapy. Once again, don’t rely on patients to return for evaluation if the lesion doesn’t improve. Many patients assume that our first empiric diagnosis is “gospel,” and therefore may not return if the treatment doesn’t work. Meanwhile, providers may assume that patients will know that there is uncertainty in our interpretation and that they will know to report if the initial treatment didn’t work. These assumptions are the recipe for delayed diagnosis. If there is too great a burden on the patient to schedule a return visit because of social or financial reasons then the patient should have a biopsy prior to initiation of treatment. As a rule, empiric treatment is not a good strategy for patients without good access to follow-up.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Sullivan S. et al Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Feb;144(2):294-8.

2. Perkins R .et al J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020 Apr;24(2):102-31.

Over the next 2 months we will dedicate this column to some general tips and pearls from the perspective of a gynecologic oncologist to guide general obstetrician gynecologists in the workup and management of preinvasive or invasive gynecologic diseases. The goal of these recommendations is to minimize misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis and avoid unnecessary or untimely referrals.

Perform biopsy, not Pap smears, on visible cervical and vaginal lesions

The purpose of the Pap smear is to screen asymptomatic patients for cervical dysplasia or microscopic invasive disease. Cytology is an unreliable diagnostic tool for visible, symptomatic lesions in large part because of sampling errors, and the lack of architectural information in cytologic versus histopathologic specimens. Invasive lesions can be mischaracterized as preinvasive on a Pap smear. This can result in delayed diagnosis and unnecessary diagnostic procedures. For example, if a visible, abnormal-appearing, cervical lesion is seen during a routine visit and a Pap smear is performed (rather than a biopsy of the mass), the patient may receive an incorrect preliminary diagnosis of “high-grade dysplasia, carcinoma in situ” as it can be difficult to distinguish invasive carcinoma from carcinoma in situ on cytology. If the patient and provider do not understand the limitations of Pap smears in diagnosing invasive cancers, they may be falsely reassured and possibly delay or abstain from follow-up for an excisional procedure. If she does return for the loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), there might still be unnecessary delays in making referrals and definitive treatment while waiting for results. Radical hysterectomy may not promptly follow because, if performed within 6 weeks of an excisional procedure, it is associated with a significantly higher risk for perioperative complication, and therefore, if the excisional procedure was unnecessary to begin with, there may be additional time lost that need not be.1

Some clinicians avoid biopsy of visible lesions because they are concerned about bleeding complications that might arise in the office. Straightforward strategies to control bleeding are readily available in most gynecology offices, especially those already equipped for procedures such as LEEP and colposcopy. Prior to performing the biopsy, clinicians should ensure that they have supplies such as gauze sponges and ring forceps or packing forceps, silver nitrate, and ferric subsulfate solution (“Monsel’s solution”) close at hand. In the vast majority of cases, direct pressure for 5 minutes with gauze sponges and ferric subsulfate is highly effective at resolving most bleeding from a cervical or vaginal biopsy site. If this does not bring hemostasis, cautery devices or suture can be employed. If all else fails, be prepared to place vaginal packing (always with the insertion of a urinary Foley catheter to prevent urinary retention). In my experience, this is rarely needed.

Wherever possible, visible cervical or vaginal (or vulvar, see below) lesions should be biopsied for histopathology, sampling representative areas of the most concerning portion, in order to minimize misdiagnosis and expedite referral and definitive treatment. For necrotic-appearing lesions I recommend taking multiple samples of the tumor, as necrotic, nonviable tissue can prevent accurate diagnosis of a cancer. In general, Pap smears should be reserved as screening tests for asymptomatic women without visible pathology.

Don’t treat or refer low-grade dysplasia, even if persistent

Increasingly we are understanding that low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract (CIN I, VAIN I, VIN I) is less a precursor for cancer, and more a phenomenon of benign HPV-associated changes.2 This HPV change may be chronically persistent, may require years of observation and serial Pap smears, and may be a general nuisance for the patient. However, current guidelines do not recommend intervention for low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract.2 Interventions to resect these lesions can result in morbidity, including perineal pain, vaginal scarring, and cervical stenosis or insufficiency. Given the extremely low risk for progression to cancer, these morbidities do not outweigh any small potential benefit.

When I am conferring with patients who have chronic low-grade dysplasia I spend a great deal of time exploring their understanding of the diagnosis and its pathophysiology, their fears, and their expectation regarding “success” of treatment. I spend the time educating them that this is a sequela of chronic viral infection that will not be eradicated with local surgical excisions, that their cancer risk and need for surveillance would persist even if surgical intervention were offered, and that the side effects of treatment would outweigh any benefit from the small risk of cancer or high-grade dysplasia.

In summary, the treatment of choice for persistent low-grade dysplasia of the lower genital tract is comprehensive patient education, not surgical resection or referral to gynecologic oncology.

Repeat sampling if there’s a discordance between imaging and biopsy results

Delay in cancer diagnosis is one of the greatest concerns for front-line gynecology providers. One of the more modifiable strategies to avoid missed or delayed diagnosis is to ensure that there is concordance between clinical findings and testing results. Otherwise said: The results and findings should make sense in aggregate. An example was cited above in which a visible cervical mass demonstrated CIN III on cytologic testing. Another common example is a biopsy result of “scant benign endometrium” in a patient with postmenopausal bleeding and thickened endometrial stripe on ultrasound. In both of these cases there is clear discordance between physical findings and the results of pathology sampling. A pathology report, in all of its black and white certitude, seems like the most reliable source of information. However, always trust your clinical judgment. If the clinical picture is suggesting something far worse than these limited, often random or blind samplings, I recommend repeated or more extensive sampling (for example, dilation and curettage). At the very least, schedule close follow-up with repeated sampling if the symptom or finding persists. The emphasis here is on scheduled follow-up, rather than “p.r.n.,” because a patient who was given a “normal” pathology result to explain her abnormal symptoms may not volunteer that those symptoms are persistent as she may feel that anything sinister was already ruled out. Make certain that you explain the potential for misdiagnosis as the reason for why you would like to see her back shortly to ensure the issue has resolved.

Biopsy vulvar lesions, minimize empiric treatment

Vulvar cancer is notoriously associated with delayed diagnosis. Unfortunately, it is commonplace for gynecologic oncologists to see women who have vulvar cancers that have been empirically treated, sometimes for months or years, with steroids or other topical agents. If a lesion on the vulva is characteristically benign in appearance (such as condyloma or lichen sclerosis), it may be reasonable to start empiric treatment. However, all patients who are treated without biopsy should be rescheduled for a planned follow-up appointment in 2-3 months. If the lesion/area remains unchanged, or worse, the lesion should be biopsied before proceeding with a change in therapy or continued therapy. Once again, don’t rely on patients to return for evaluation if the lesion doesn’t improve. Many patients assume that our first empiric diagnosis is “gospel,” and therefore may not return if the treatment doesn’t work. Meanwhile, providers may assume that patients will know that there is uncertainty in our interpretation and that they will know to report if the initial treatment didn’t work. These assumptions are the recipe for delayed diagnosis. If there is too great a burden on the patient to schedule a return visit because of social or financial reasons then the patient should have a biopsy prior to initiation of treatment. As a rule, empiric treatment is not a good strategy for patients without good access to follow-up.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Sullivan S. et al Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Feb;144(2):294-8.

2. Perkins R .et al J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020 Apr;24(2):102-31.

Combination atezolizumab and bevacizumab succeeds in real-world setting

Key clinical point: In the real-world setting, patients with unresectable HCC who did not meet clinical trial criteria had similar responses to the treatment combination as those who met clinical trial criteria.

Major finding: The objective response rates and disease control rates of 5.2% and 82.8% at 6 weeks and 10.0% and 84.0% at 12 weeks, respectively, were similar between patients who met and did not meet the IMbrave150 clinical trial criteria, as were safety profiles.

Study details: The data come from a multicenter study of 64 adults with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma, including 46 who did not meet the study criteria. All patients were treated with a combination of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab. Treatment response and safety issues were assessed at 6 weeks and 12 weeks.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Sho T et al. Hepatol Res. 2021 Jul 10. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13693.

Key clinical point: In the real-world setting, patients with unresectable HCC who did not meet clinical trial criteria had similar responses to the treatment combination as those who met clinical trial criteria.

Major finding: The objective response rates and disease control rates of 5.2% and 82.8% at 6 weeks and 10.0% and 84.0% at 12 weeks, respectively, were similar between patients who met and did not meet the IMbrave150 clinical trial criteria, as were safety profiles.

Study details: The data come from a multicenter study of 64 adults with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma, including 46 who did not meet the study criteria. All patients were treated with a combination of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab. Treatment response and safety issues were assessed at 6 weeks and 12 weeks.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Sho T et al. Hepatol Res. 2021 Jul 10. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13693.

Key clinical point: In the real-world setting, patients with unresectable HCC who did not meet clinical trial criteria had similar responses to the treatment combination as those who met clinical trial criteria.

Major finding: The objective response rates and disease control rates of 5.2% and 82.8% at 6 weeks and 10.0% and 84.0% at 12 weeks, respectively, were similar between patients who met and did not meet the IMbrave150 clinical trial criteria, as were safety profiles.

Study details: The data come from a multicenter study of 64 adults with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma, including 46 who did not meet the study criteria. All patients were treated with a combination of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab. Treatment response and safety issues were assessed at 6 weeks and 12 weeks.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Sho T et al. Hepatol Res. 2021 Jul 10. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13693.

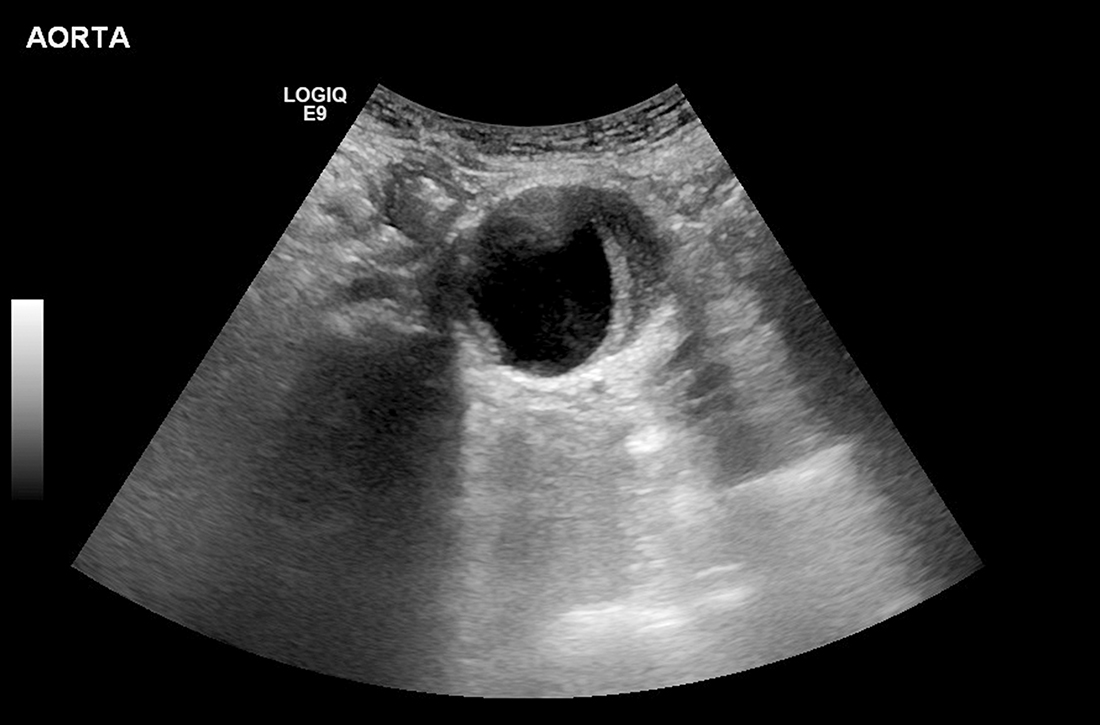

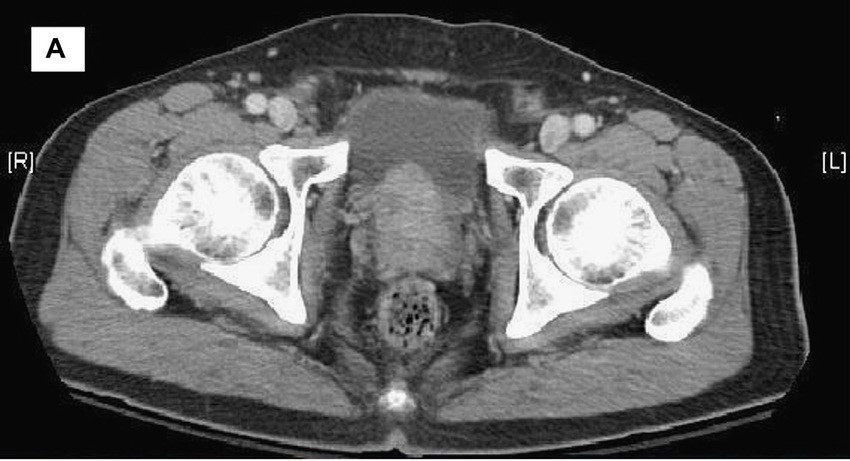

Can family physicians accurately screen for AAA with point-of-care ultrasound?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Meta-analysis demonstrates accuracy of nonradiologist providers with POCUS

A systematic review and meta-analysis (11 studies; 946 exams) compared nonradiologist-performed AAA screening with POCUS vs radiologist-performed aortic imaging as a gold standard. Eight trials involved emergency medicine physicians (718 exams); 1 trial, surgical residents (104 exams); 1 trial, primary care internal medicine physicians (79 exams); and 1 trial, rural family physicians (45 exams). The majority of studies were conducted in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada, with 4 trials performed in the United States.1

Researchers compared all POCUS exam findings with radiologist-performed imaging (using ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or angiography) and with operative findings or pathology where available. There were 193 true positives, 8 false-positives, 740 true negatives, and 5 false-negatives. Primary care physicians identified 6 patients with AAA, with no false-positives or false-negatives. Overall, POCUS demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.975 (95% CI, 0.942 to 0.992) and a specificity of 0.989 (95% CI, 0.979 to 0.995).1

Nonradiologist providers received POCUS training as follows: emergency medicine residents, 5 hours to 3 days; emergency medicine physicians, 4 to 24 hours of didactics, 50 AAA scans, or American College of Emergency Medicine certification; and primary care physicians, 2.3 hours or 50 AAA scans. Information on training for surgical residents was not supplied. The authors rated the studies for quality (10-14 points on the 14-point QUADA quality score) and heterogeneity (I2 = 0 for sensitivity and I2 = .38 for specificity).1

European studies support FPs’ ability to diagnose AAA with POCUS

Two subsequent prospective diagnostic accuracy studies both found that POCUS performed by family physicians had 100% concordance with radiologist overread. The first study (in Spain) included 106 men (ages 50 and older; mean, 69 years) with chronic hypertension or a history of tobacco use. One family physician underwent training (duration not reported) by a radiologist, including experience measuring standard cross-sections of the aorta. Radiologists reviewed all POCUS images, which identified 6 patients with AAA (confirmed by CT scan). The concordance between the family physician and the radiologists was absolute (kappa = 1.0; sensitivity and specificity, 100%; positive and negative predictive values, both 1.0).2

The second study (in Denmark) compared 29 POCUS screenings for AAA performed by 5 family physicians vs a gold standard of a radiologist-performed abdominal ultrasound blinded to previous ultrasound findings. Four of the family physicians were board certified and 1 was a final-year resident in training. They all underwent a 3-day ultrasonography course that included initial e-learning followed by 2 days of hands-on training; all passed a final certification exam. The family physicians identified 1 patient with AAA. Radiologists overread all the scans and found 100% agreement with the 1 positive AAA and the 28 negative scans.3

Recommendations from others

In 2019, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) offered a Grade “B” (moderate net benefit) recommendation for screening with ultrasonography for AAA in men ages 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked, and a Grade “C” recommendation (small net benefit) for screening men ages 65 to 75 years who have never smoked.4 In 2017, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care recommended screening all men ages 65 to 80 years with 1 ultrasound exam for AAA (weak recommendation; moderate-quality evidence). The Canadian Task Force also noted that, with adequate training, AAA screening could be performed in a family practice setting.5

Editor’s takeaway

While these studies evaluating POCUS performed by nonradiologists included a small number of family physicians, their finding that all participants (attending physicians and residents) demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity for AAA detection with relatively limited training bodes well for more widespread use of the technology. Offering POCUS to detect AAAs in family physician offices has the potential to dramatically improve access to USPSTF-recommended screening.

1. Concannon E, McHugh S, Healy DA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of non-radiologist performed ultrasound for abdominal aortic aneurysm: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;9:1122-1129. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12453

2. Sisó-Almirall A, Gilabert Solé R, Bru Saumell C, et al. Feasibility of hand-held-ultrasonography in the screening of abdominal aortic aneurysms and abdominal aortic atherosclerosis [article in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2013;141:417-422. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2013.02.038

3. Lindgaard K, Riisgaard L. ‘Validation of ultrasound examinations performed by general practitioners’. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2017;3:256-261. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2017.1358437

4. US Preventive Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322:2211-2218. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.18928

5. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in primary care. CMAJ. 2017;189:E1137-E1145. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170118

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Meta-analysis demonstrates accuracy of nonradiologist providers with POCUS

A systematic review and meta-analysis (11 studies; 946 exams) compared nonradiologist-performed AAA screening with POCUS vs radiologist-performed aortic imaging as a gold standard. Eight trials involved emergency medicine physicians (718 exams); 1 trial, surgical residents (104 exams); 1 trial, primary care internal medicine physicians (79 exams); and 1 trial, rural family physicians (45 exams). The majority of studies were conducted in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada, with 4 trials performed in the United States.1

Researchers compared all POCUS exam findings with radiologist-performed imaging (using ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or angiography) and with operative findings or pathology where available. There were 193 true positives, 8 false-positives, 740 true negatives, and 5 false-negatives. Primary care physicians identified 6 patients with AAA, with no false-positives or false-negatives. Overall, POCUS demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.975 (95% CI, 0.942 to 0.992) and a specificity of 0.989 (95% CI, 0.979 to 0.995).1

Nonradiologist providers received POCUS training as follows: emergency medicine residents, 5 hours to 3 days; emergency medicine physicians, 4 to 24 hours of didactics, 50 AAA scans, or American College of Emergency Medicine certification; and primary care physicians, 2.3 hours or 50 AAA scans. Information on training for surgical residents was not supplied. The authors rated the studies for quality (10-14 points on the 14-point QUADA quality score) and heterogeneity (I2 = 0 for sensitivity and I2 = .38 for specificity).1

European studies support FPs’ ability to diagnose AAA with POCUS

Two subsequent prospective diagnostic accuracy studies both found that POCUS performed by family physicians had 100% concordance with radiologist overread. The first study (in Spain) included 106 men (ages 50 and older; mean, 69 years) with chronic hypertension or a history of tobacco use. One family physician underwent training (duration not reported) by a radiologist, including experience measuring standard cross-sections of the aorta. Radiologists reviewed all POCUS images, which identified 6 patients with AAA (confirmed by CT scan). The concordance between the family physician and the radiologists was absolute (kappa = 1.0; sensitivity and specificity, 100%; positive and negative predictive values, both 1.0).2

The second study (in Denmark) compared 29 POCUS screenings for AAA performed by 5 family physicians vs a gold standard of a radiologist-performed abdominal ultrasound blinded to previous ultrasound findings. Four of the family physicians were board certified and 1 was a final-year resident in training. They all underwent a 3-day ultrasonography course that included initial e-learning followed by 2 days of hands-on training; all passed a final certification exam. The family physicians identified 1 patient with AAA. Radiologists overread all the scans and found 100% agreement with the 1 positive AAA and the 28 negative scans.3

Recommendations from others

In 2019, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) offered a Grade “B” (moderate net benefit) recommendation for screening with ultrasonography for AAA in men ages 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked, and a Grade “C” recommendation (small net benefit) for screening men ages 65 to 75 years who have never smoked.4 In 2017, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care recommended screening all men ages 65 to 80 years with 1 ultrasound exam for AAA (weak recommendation; moderate-quality evidence). The Canadian Task Force also noted that, with adequate training, AAA screening could be performed in a family practice setting.5

Editor’s takeaway

While these studies evaluating POCUS performed by nonradiologists included a small number of family physicians, their finding that all participants (attending physicians and residents) demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity for AAA detection with relatively limited training bodes well for more widespread use of the technology. Offering POCUS to detect AAAs in family physician offices has the potential to dramatically improve access to USPSTF-recommended screening.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Meta-analysis demonstrates accuracy of nonradiologist providers with POCUS

A systematic review and meta-analysis (11 studies; 946 exams) compared nonradiologist-performed AAA screening with POCUS vs radiologist-performed aortic imaging as a gold standard. Eight trials involved emergency medicine physicians (718 exams); 1 trial, surgical residents (104 exams); 1 trial, primary care internal medicine physicians (79 exams); and 1 trial, rural family physicians (45 exams). The majority of studies were conducted in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada, with 4 trials performed in the United States.1

Researchers compared all POCUS exam findings with radiologist-performed imaging (using ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or angiography) and with operative findings or pathology where available. There were 193 true positives, 8 false-positives, 740 true negatives, and 5 false-negatives. Primary care physicians identified 6 patients with AAA, with no false-positives or false-negatives. Overall, POCUS demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.975 (95% CI, 0.942 to 0.992) and a specificity of 0.989 (95% CI, 0.979 to 0.995).1

Nonradiologist providers received POCUS training as follows: emergency medicine residents, 5 hours to 3 days; emergency medicine physicians, 4 to 24 hours of didactics, 50 AAA scans, or American College of Emergency Medicine certification; and primary care physicians, 2.3 hours or 50 AAA scans. Information on training for surgical residents was not supplied. The authors rated the studies for quality (10-14 points on the 14-point QUADA quality score) and heterogeneity (I2 = 0 for sensitivity and I2 = .38 for specificity).1

European studies support FPs’ ability to diagnose AAA with POCUS

Two subsequent prospective diagnostic accuracy studies both found that POCUS performed by family physicians had 100% concordance with radiologist overread. The first study (in Spain) included 106 men (ages 50 and older; mean, 69 years) with chronic hypertension or a history of tobacco use. One family physician underwent training (duration not reported) by a radiologist, including experience measuring standard cross-sections of the aorta. Radiologists reviewed all POCUS images, which identified 6 patients with AAA (confirmed by CT scan). The concordance between the family physician and the radiologists was absolute (kappa = 1.0; sensitivity and specificity, 100%; positive and negative predictive values, both 1.0).2

The second study (in Denmark) compared 29 POCUS screenings for AAA performed by 5 family physicians vs a gold standard of a radiologist-performed abdominal ultrasound blinded to previous ultrasound findings. Four of the family physicians were board certified and 1 was a final-year resident in training. They all underwent a 3-day ultrasonography course that included initial e-learning followed by 2 days of hands-on training; all passed a final certification exam. The family physicians identified 1 patient with AAA. Radiologists overread all the scans and found 100% agreement with the 1 positive AAA and the 28 negative scans.3

Recommendations from others

In 2019, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) offered a Grade “B” (moderate net benefit) recommendation for screening with ultrasonography for AAA in men ages 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked, and a Grade “C” recommendation (small net benefit) for screening men ages 65 to 75 years who have never smoked.4 In 2017, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care recommended screening all men ages 65 to 80 years with 1 ultrasound exam for AAA (weak recommendation; moderate-quality evidence). The Canadian Task Force also noted that, with adequate training, AAA screening could be performed in a family practice setting.5

Editor’s takeaway

While these studies evaluating POCUS performed by nonradiologists included a small number of family physicians, their finding that all participants (attending physicians and residents) demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity for AAA detection with relatively limited training bodes well for more widespread use of the technology. Offering POCUS to detect AAAs in family physician offices has the potential to dramatically improve access to USPSTF-recommended screening.

1. Concannon E, McHugh S, Healy DA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of non-radiologist performed ultrasound for abdominal aortic aneurysm: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;9:1122-1129. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12453

2. Sisó-Almirall A, Gilabert Solé R, Bru Saumell C, et al. Feasibility of hand-held-ultrasonography in the screening of abdominal aortic aneurysms and abdominal aortic atherosclerosis [article in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2013;141:417-422. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2013.02.038

3. Lindgaard K, Riisgaard L. ‘Validation of ultrasound examinations performed by general practitioners’. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2017;3:256-261. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2017.1358437

4. US Preventive Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322:2211-2218. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.18928

5. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in primary care. CMAJ. 2017;189:E1137-E1145. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170118

1. Concannon E, McHugh S, Healy DA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of non-radiologist performed ultrasound for abdominal aortic aneurysm: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;9:1122-1129. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12453

2. Sisó-Almirall A, Gilabert Solé R, Bru Saumell C, et al. Feasibility of hand-held-ultrasonography in the screening of abdominal aortic aneurysms and abdominal aortic atherosclerosis [article in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2013;141:417-422. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2013.02.038

3. Lindgaard K, Riisgaard L. ‘Validation of ultrasound examinations performed by general practitioners’. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2017;3:256-261. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2017.1358437

4. US Preventive Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322:2211-2218. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.18928

5. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in primary care. CMAJ. 2017;189:E1137-E1145. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170118

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Likely yes. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) by nonradiologist physicians is 98% sensitive and 99% specific, compared with imaging performed by radiologists (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies mostly involving emergency medicine physicians). European family physicians demonstrated 100% concordance with radiologist readings (SOR: C, very small subsequent diagnostic accuracy studies).

‘Gold cards’ allow Texas docs to skip prior authorizations

In what could be a model for other states, Texas has become the first state to exempt physicians from prior authorizations for meeting insurer benchmarks.

The law was passed in June and will take effect in September. It excuses physicians from having to obtain prior authorization if, during the previous 6 months, 90% of their treatments met medical necessity criteria by the health insurer. Through this law, doctors in the state will spend less time getting approvals for treatments for their patients.

Automatic approval of authorizations for treatments – or what the Texas Medical Association calls a “gold card” – “allows patients to get the care they need in a more timely fashion,” says Debra Patt, MD, an Austin, Tex.–based oncologist and former chair of the council on legislation for the TMA.

About 87% of Texas physicians reported a “drastic increase over the past 5 years in the burden of prior authorization on their patients and their practices,” per a 2020 survey by the TMA. Nearly half (48%) of Texas physicians have hired staff whose work focuses on processing requests for prior authorization, according to the survey.

Jack Resneck Jr., MD, a San Francisco–based dermatologist and president-elect of the American Medical Association, said other states have investigated ways to ease the impact of prior authorizations on physicians, but no other state has passed such a law.

Administrative burdens plague physicians around the country. The Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2021 found that physicians spend on average 15.6 hours per week on paperwork and administrative duties.

Better outcomes, less anxiety for patients

Dr. Patt, who testified in support of the law’s passage in the Texas legislature, says automatic approval of authorizations “is better for patients because it reduces their anxiety about whether they’re able to get the treatments they need now, and they will have better outcomes if they’re able to receive more timely care.”

Recently, a chemotherapy treatment Dr. Patt prescribed for one of her patients was not authorized by an insurer. The result is “a lot of anxiety and potentially health problems” for the patient.

She expects that automatic approval for treatments will be based on prescribing patterns during the preceding 6 months. “It means that when I order a test today, the [health insurer] looks back at my record 6 months previously,” she said. Still, Dr. Patt awaits guidance from the Texas Department of Insurance, which regulates health insurers in the state, regarding the law.

Dr. Resneck said the pharmacy counter is where most patients encounter prior authorization delays. “That’s when the pharmacist looks at them and says: ‘Actually, this isn’t covered by your health insurer’s formulary,’ or it isn’t covered fully on their formulary.”

One of Dr. Resneck’s patients had a life-altering case of eczema that lasted many years. Because of the condition, the patient couldn’t work or maintain meaningful bonds with family members. A biologic treatment transformed his patient’s life. The patient was able to return to work and to reengage with family, said Dr. Resneck. But a year after his patient started the treatment, the health insurer wouldn’t authorize the treatment because the patient wasn’t experiencing the same symptoms.

The patient didn’t have the same symptoms because the biologic treatment worked, said Dr. Resneck.

Kristine Grow, a spokesperson for America’s Health Insurance Plans, a national association for health insurers, said: “The use of prior authorization is relatively small – typically, less than 15% – and can help ensure safer opioid prescribing, help prevent dangerous drug interactions, and help protect patients from unnecessary exposure to potentially harmful radiation for inappropriate diagnostic imaging. Numerous studies show that Americans frequently receive inappropriate care, and 25% of unnecessary treatments are associated with complications or adverse events.”

Medical management tools, such as prior authorization, are “an important way” to deliver “safe, high-quality care” to patients, she added.

Potential for harm?

Sadeea Abbasi, MD, a practicing physician at Cedars-Sinai in the gastroenterology clinical office in Santa Monica, Calif., can attest that these practices are harmful for her patients.

“Prior authorization requirements have been on the rise across various medical specialties. For GI, we have seen an increase of required approvals for procedures like upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, and wireless capsule endoscopy and in medications prescribed, including biologic infusions for inflammatory bowel disease.”

Dr. Abbasi added: “One of the largest concerns I have with this growing ‘cost-savings’ trend is the impact it has on clinical outcomes. I have seen patients suffer with symptoms while waiting for a decision on a prior authorization for a medication. My patients have endured confusion and chaos when arriving for imaging appointments, only to learn the insurance has not reached a decision on whether the study is approved. When patients learn their procedure has been delayed, they have to reschedule the appointment, take another day off work, coordinate transportation and most importantly, postpone subsequent treatments to alleviate symptoms.”

According to an AMA survey, almost all physicians (94%) said prior authorization delays care and 79% percent have had patients abandon their recommended treatment because of issues related to prior authorization. This delay causes potentially irreversible damage to patients’ digestive system and increases the likelihood of hospitalization. This is a huge issue for America’s seniors: Medicare Advantage (MA) plans, which represent 24.1 million of the 62 million Medicare beneficiaries, the increase in prior authorization requests has been substantial.

State and federal efforts to curb prior authorization

In addition to efforts to curb prior authorization in other states, the AMA and nearly 300 other stakeholders, including the American Gastroenterological Association, support the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R. 3173). The legislation includes a provision related to “gold carding,” said Robert Mills, an AMA spokesperson.

The bill aims to establish transparency requirements and standards for prior authorization processes related to MA plans. The requirements and standards for MA plans include the following:

- Establishing an electronic prior authorization program that meets specific standards, such as the ability to provide real-time decisions in response to requests for items and services that are routinely approved.

- Publishing on an annual basis specific prior authorization information, including the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Ensuring prior authorization requests are reviewed by qualified medical personnel.

- Meeting standards set by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services related to the quality and timeliness of prior authorization determinations.