User login

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: CML November 2021

In the new era of the COVID-19 pandemic, patients and physicians still struggle to see how different hematologic conditions may be affected by this viral infection. Although it has been well reported that COVID-19 may not be as lethal in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) as other malignancies, patients still may be at risk of bad outcomes. A recent publication by Breccia et al1 collected retrospective information on more than 8000 CML patients followed at different institutions in Italy up to January 2021. The authors recorded 217 patients (2.5%) who were SARS-CO-V2 (COVID-19) positive. More than half of the patients had concomitant comorbidities. Almost 80% were quarantined while the rest required hospitalization, although only 3.6 required intensive care unit care. Twelve patients died, which represents 0.13% of the whole cohort. The main predisposing factors were age > 65 years and cardiovascular disorders, similar to that the general population. Most of patients continue tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy during the infection.

While the introduction of TKI for the treatment of CML make the number of allogenic transplants decrease significantly due the high mortality in comparison with TKI therapy, it is still an option for certain patients who failed multiple TKI treatments or progressed to more advanced phases of the disease. Although it has already been described that the introduction of imatinib did not affect outcomes for patients that require this therapeutic option, there was not much data about the effect of second generation TKIs. In a publication by Masouridi-Levrat S et al2 the authors examine the effect of second generation TKIs in a prospective non-interventional study performed by the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation on 383 consecutive CML patients previously treated with dasatinib or nilotinib undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT) from 2009 to 2013. Less than 40% of patients received the transplant in the chronic phase while the rest were in accelerated or blast phase. With a median follow-up of 37 months, 8% of patients developed either primary or secondary graft failure, 34% acute graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), and 60% chronic GvHD. The non-relapse mortality was 18% and 24% at 12 months and at 5 years, respectively. Relapse incidence was 36%, overall survival 56%, and relapse-free survival 40% at 5 years. All these data showed the feasibility of this procedure in patients treated with second generation TKIs with similar post-transplant complications in TKI naive patients or patients treated with imatinib.

Patients under therapy with TKIs may frequently present with elevations of creatine kinase (CK), thought to be in some cases related with the classical associations with muscle and joint pain that is also a common side effect. However the long run effect on treatment outcomes has not been well studied. Bankar A et al.3 recently reported on the relation between CK elevations and overall survival (OS) and event free survival (EFS). Interestingly CK elevations secondary to first or second generation TKIs were associated with a better OS and EFS. As expected, high Sokal score patients had a worse OS and EFS.

References

- Breccia M et al. COVID-19 infection in chronic myeloid leukaemia after one year of the pandemic in Italy. A Campus CML report. Br J Haematol. 2021 Oct 11.

- Masouridi-Levrat S et al. Outcomes and toxicity of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in chronic myeloid leukemia patients previously treated with second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a prospective non-interventional study from the Chronic Malignancy Working Party of the EBMT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021 Oct 1.

- Bankar A, Lipton JH. Association of creatine kinase elevation with clinical outcomes in chronic myeloid leukemia: a retrospective cohort study Leuk Lymphoma. 2021 Sep 8.

In the new era of the COVID-19 pandemic, patients and physicians still struggle to see how different hematologic conditions may be affected by this viral infection. Although it has been well reported that COVID-19 may not be as lethal in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) as other malignancies, patients still may be at risk of bad outcomes. A recent publication by Breccia et al1 collected retrospective information on more than 8000 CML patients followed at different institutions in Italy up to January 2021. The authors recorded 217 patients (2.5%) who were SARS-CO-V2 (COVID-19) positive. More than half of the patients had concomitant comorbidities. Almost 80% were quarantined while the rest required hospitalization, although only 3.6 required intensive care unit care. Twelve patients died, which represents 0.13% of the whole cohort. The main predisposing factors were age > 65 years and cardiovascular disorders, similar to that the general population. Most of patients continue tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy during the infection.

While the introduction of TKI for the treatment of CML make the number of allogenic transplants decrease significantly due the high mortality in comparison with TKI therapy, it is still an option for certain patients who failed multiple TKI treatments or progressed to more advanced phases of the disease. Although it has already been described that the introduction of imatinib did not affect outcomes for patients that require this therapeutic option, there was not much data about the effect of second generation TKIs. In a publication by Masouridi-Levrat S et al2 the authors examine the effect of second generation TKIs in a prospective non-interventional study performed by the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation on 383 consecutive CML patients previously treated with dasatinib or nilotinib undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT) from 2009 to 2013. Less than 40% of patients received the transplant in the chronic phase while the rest were in accelerated or blast phase. With a median follow-up of 37 months, 8% of patients developed either primary or secondary graft failure, 34% acute graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), and 60% chronic GvHD. The non-relapse mortality was 18% and 24% at 12 months and at 5 years, respectively. Relapse incidence was 36%, overall survival 56%, and relapse-free survival 40% at 5 years. All these data showed the feasibility of this procedure in patients treated with second generation TKIs with similar post-transplant complications in TKI naive patients or patients treated with imatinib.

Patients under therapy with TKIs may frequently present with elevations of creatine kinase (CK), thought to be in some cases related with the classical associations with muscle and joint pain that is also a common side effect. However the long run effect on treatment outcomes has not been well studied. Bankar A et al.3 recently reported on the relation between CK elevations and overall survival (OS) and event free survival (EFS). Interestingly CK elevations secondary to first or second generation TKIs were associated with a better OS and EFS. As expected, high Sokal score patients had a worse OS and EFS.

References

- Breccia M et al. COVID-19 infection in chronic myeloid leukaemia after one year of the pandemic in Italy. A Campus CML report. Br J Haematol. 2021 Oct 11.

- Masouridi-Levrat S et al. Outcomes and toxicity of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in chronic myeloid leukemia patients previously treated with second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a prospective non-interventional study from the Chronic Malignancy Working Party of the EBMT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021 Oct 1.

- Bankar A, Lipton JH. Association of creatine kinase elevation with clinical outcomes in chronic myeloid leukemia: a retrospective cohort study Leuk Lymphoma. 2021 Sep 8.

In the new era of the COVID-19 pandemic, patients and physicians still struggle to see how different hematologic conditions may be affected by this viral infection. Although it has been well reported that COVID-19 may not be as lethal in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) as other malignancies, patients still may be at risk of bad outcomes. A recent publication by Breccia et al1 collected retrospective information on more than 8000 CML patients followed at different institutions in Italy up to January 2021. The authors recorded 217 patients (2.5%) who were SARS-CO-V2 (COVID-19) positive. More than half of the patients had concomitant comorbidities. Almost 80% were quarantined while the rest required hospitalization, although only 3.6 required intensive care unit care. Twelve patients died, which represents 0.13% of the whole cohort. The main predisposing factors were age > 65 years and cardiovascular disorders, similar to that the general population. Most of patients continue tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy during the infection.

While the introduction of TKI for the treatment of CML make the number of allogenic transplants decrease significantly due the high mortality in comparison with TKI therapy, it is still an option for certain patients who failed multiple TKI treatments or progressed to more advanced phases of the disease. Although it has already been described that the introduction of imatinib did not affect outcomes for patients that require this therapeutic option, there was not much data about the effect of second generation TKIs. In a publication by Masouridi-Levrat S et al2 the authors examine the effect of second generation TKIs in a prospective non-interventional study performed by the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation on 383 consecutive CML patients previously treated with dasatinib or nilotinib undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT) from 2009 to 2013. Less than 40% of patients received the transplant in the chronic phase while the rest were in accelerated or blast phase. With a median follow-up of 37 months, 8% of patients developed either primary or secondary graft failure, 34% acute graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), and 60% chronic GvHD. The non-relapse mortality was 18% and 24% at 12 months and at 5 years, respectively. Relapse incidence was 36%, overall survival 56%, and relapse-free survival 40% at 5 years. All these data showed the feasibility of this procedure in patients treated with second generation TKIs with similar post-transplant complications in TKI naive patients or patients treated with imatinib.

Patients under therapy with TKIs may frequently present with elevations of creatine kinase (CK), thought to be in some cases related with the classical associations with muscle and joint pain that is also a common side effect. However the long run effect on treatment outcomes has not been well studied. Bankar A et al.3 recently reported on the relation between CK elevations and overall survival (OS) and event free survival (EFS). Interestingly CK elevations secondary to first or second generation TKIs were associated with a better OS and EFS. As expected, high Sokal score patients had a worse OS and EFS.

References

- Breccia M et al. COVID-19 infection in chronic myeloid leukaemia after one year of the pandemic in Italy. A Campus CML report. Br J Haematol. 2021 Oct 11.

- Masouridi-Levrat S et al. Outcomes and toxicity of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in chronic myeloid leukemia patients previously treated with second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a prospective non-interventional study from the Chronic Malignancy Working Party of the EBMT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021 Oct 1.

- Bankar A, Lipton JH. Association of creatine kinase elevation with clinical outcomes in chronic myeloid leukemia: a retrospective cohort study Leuk Lymphoma. 2021 Sep 8.

Serotonin-mediated anxiety: How to recognize and treat it

Sara R. Abell, MD, and Rif S. El-Mallakh, MD

Individuals with anxiety will experience frequent or chronic excessive worry, nervousness, a sense of unease, a feeling of being unfocused, and distress, which result in functional impairment.1 Frequently, anxiety is accompanied by restlessness or muscle tension. Generalized anxiety disorder is one of the most common psychiatric diagnoses in the United States and has a prevalence of 2% to 6% globally.2 Although research has been conducted regarding anxiety’s pathogenesis, to date a firm consensus on its etiology has not been reached.3 It is likely multifactorial, with environmental and biologic components.

One area of focus has been neurotransmitters and the possible role they play in the pathogenesis of anxiety. Specifically, the monoamine neurotransmitters have been implicated in the clinical manifestations of anxiety. Among the amines, normal roles include stimulating the autonomic nervous system and regulating numerous cognitive phenomena, such as volition and emotion. Many psychiatric medications modify aminergic transmission, and many current anxiety medications target amine neurotransmitters. Medications that target histamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine all play a role in treating anxiety.

In this article, we focus on serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) as a mediator of anxiety and on excessive synaptic 5-HT as the cause of anxiety. We discuss how 5-HT–mediated anxiety can be identified and offer some solutions for its treatment.

The amine neurotransmitters

There are 6 amine neurotransmitters in the CNS. These are derived from tyrosine (dopamine [DA], norepinephrine [NE], and epinephrine), histidine (histamine), and tryptophan (serotonin [5-HT] and melatonin). In addition to their physiologic actions, amines have been implicated in both acute and chronic anxiety. Excessive DA stimulation has been linked with fear4,5; NE elevations are central to hypervigilance and hyperarousal of posttraumatic stress disorder6; and histamine may mediate emotional memories involved in fear and anxiety.7 Understanding the normal function of 5-HT will aid in understanding its potential problematic role (Box,8-18page 38).

How serotonin-mediated anxiety presents

“Anxiety” is a collection of signs and symptoms that likely represent multiple processes and have the common characteristic of being subjectively unpleasant, with a subjective wish for the feeling to end. The expression of anxiety disorders is quite diverse and ranges from brief episodes such as panic attacks (which may be mediated, in part, by epinephrine/NE19) to lifelong stereotypic obsessions and compulsions (which may be mediated, in part, by DA and modified by 5-HT20,21). Biochemical separation of the anxiety disorders is key to achieving tailored treatment.6 Towards this end, it is important to investigate the phenomenon of serotonin-mediated anxiety.

Because clinicians are familiar with reductions of anxiety as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) increase 5-HT levels in the synapse, it is difficult to conceptualize serotonin-mediated anxiety. However, many of the effects at postsynaptic 5-HT receptors may be biphasic.15-18 Serotonin-mediated anxiety appears to occur when levels of 5-HT (or stimulation of 5-HT receptors) are particularly high. This is most frequently seen in patients who genetically have high synaptic 5-HT (by virtue of the short form of the 5-HT transporter),22 whose synaptic 5-HT is further increased by treatment with an SSRI,23 and who are experiencing a stressor that yet further increases their synaptic 5-HT.24 However, it may occur in some individuals with only 2 of these 3 conditions.Clinically, individuals with serotonin-mediated anxiety will usually appear calm. The anxiety they are experiencing is not exhibited in any way in the motor system (ie, they do not appear restless, do not pace, muscle tone is not increased, etc.). However, they will generally complain of an internal agitation, a sense of a negative internal energy. Frequently, they will use descriptions such as “I feel I could jump out of my skin.” As previously mentioned, this is usually in the setting of some environmental stress, in addition to either a pharmacologic (SSRI) or genetic (short form of the 5-HT transporter) reason for increasing synaptic 5-HT, or both.

Almost always, interventions that block multiple postsynaptic 5-HT receptors or discontinuation of the SSRI (if applicable) will alleviate the anxiety, quickly or more slowly, respectively. Sublingual asenapine, which at low doses can block 5-HT2C (Ki = 0.03 nM), 5-HT2A (Ki = 0.07 nM), 5-HT7 (Ki = 0.11 nM), 5-HT2B (Ki = 0.18 nM), and 5-HT6 (Ki = 0.25 nM),25,26 and which will produce peak plasma levels within 10 minutes,27 usually is quite effective.

Box

Serotonin (5-HT) arises from neurons in the raphe nuclei of the rostral pons and projects superiorly to the cerebral cortex and inferiorly to the spinal cord.8 It works in an inhibitory or excitatory manner depending on which receptors are activated. In the periphery, 5-HT influences intestinal peristalsis, sensory modulation, gland function, thermoregulation, blood pressure, platelet aggregation, and sexual behavior,9 all actions that produce potential adverse effects of serotonin reuptake– inhibiting antidepressants. In the CNS, 5-HT plays a role in attention bias; decision-making; sleep and wakefulness; and mood regulation. In short, serotonin can be viewed as mediating emotional motivation.10

Serotonin alters neuroplasticity. During development, 5-HT stimulates creation of new synapses and increases the density of synaptic webs. It has a direct stimulatory effect on the length of dendrites, their branching, and their myelination.11 In the CNS, it plays a role in dendritic arborization. Animal studies with rats have shown that lesioning highly concentrated 5-HT areas at early ages resulted in an adult brain with a lower number of neurons and a less complex web of dendrites.12,13 In situations of emotional stress, it is theorized that low levels of 5-HT lead to a reduced ability to deal with emotional stressors due to lower levels of complexity in synaptic connections.

Serotonin has also been implicated in mediating some aspects of dopamine-related actions, such as locomotion, reward, and threat avoidance. This is believed to contribute to the beneficial effect of 5-HT2A blockade by secondgeneration antipsychotics (SGAs).14 Blockade of other 5-HT receptors, such as 5-HT1A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7, may also contribute to the antipsychotic action of SGAs.14

Serotonin receptors are found throughout the body, and 14 subtypes have been identified.9 Excitatory and inhibitory action of 5-HT depends on the receptor, and the actions of 5-HT can differ with the same receptor at different concentrations. This is because serotonin’s effects are biphasic and concentration-dependent, meaning that levels of 5-HT in the synapse will dictate the downstream effect of receptor agonism or antagonism. Animal models have shown that low-dose agonism of 5-HT receptors causes vasoconstriction of the coronary arteries, and high doses cause relaxation. This response has also been demonstrated in the vasculature of the kidneys and the smooth muscle of the trachea. Additionally, 5-HT works in conjunction with histamine to produce a biphasic response in the colonic arteries and veins in situations of endothelial damage.15

Most relevant to this discussion are 5-HT’s actions in mood regulation and behavior. Low 5-HT states result in less behavioral inhibition, leading to higher impulse control failures and aggression. Experiments in mice with deficient serotonergic brain regions show hypoactivity, extended daytime sleep, anxiety, and depressive behaviors.13 Serotonin’s behavioral effects are also biphasic. For example, lowdose antagonism with trazodone of 5-HT receptors demonstrated a pro-aggressive behavioral effect, while high-dose antagonism is anti-aggressive.15 Similar biphasic effects may result in either induction or reduction of anxiety with agents that block or excite certain 5-HT receptors.16-18

Continue to: A key difference: No motor system involvement...

A key difference: No motor system involvement

What distinguishes 5-HT from the other amine transmitters as a mediator of anxiety is the lack of involvement of the motor system. Multiple studies in rats illustrate that exogenously augmenting 5-HT has no effect on levels of locomotor activity. Dopamine depletion is well-characterized in the motor dysfunction of Parkinson’s disease, and DA excess can cause repetitive, stereotyped movements, such as seen in tardive dyskinesia or Huntington’s disease.8 In humans, serotonin-mediated anxiety is usually without a motoric component; patients appear calm but complain of extreme anxiety or agitation. Agitation has been reported after initiation of an SSRI,29 and is more likely to occur in patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter.30 Motoric activation has been reported in some of these studies, but does not seem to cluster with the complaint of agitation.29 The reduced number of available transporters means a chronic steady-state elevation of serotonin, because less serotonin is being removed from the synapse after it is released. This is one of the reasons patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter may be more susceptible to serotonin-mediated anxiety.

What you need to keep in mind

Pharmacologic treatment of anxiety begins with an SSRI, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), or buspirone. Second-line treatments include hydroxyzine, gabapentin, pregabalin, and quetiapine.3,31 However, clinicians need to be aware that a fraction of their patients will report anxiety that will not have any external manifestations, but will be experienced as an unpleasant internal energy. These patients may report an increase in their anxiety levels when started on an SSRI or SNRI.29,30 This anxiety is most likely mediated by increases of synaptic 5-HT. This occurs because many serotonergic receptors may have a biphasic response, so that too much stimulation is experienced as excessive internal energy.16-18 In such patients, blockade of key 5-HT receptors may reduce that internal agitation. The advantage of recognizing serotonin-mediated anxiety is that one can specifically tailor treatment to address the patient’s specific physiology.

It is important to note that the anxiolytic effect of asenapine is specific to patients with serotonin-mediated anxiety. Unlike quetiapine, which is effective as augmentation therapy in generalized anxiety disorder,31 asenapine does not appear to reduce anxiety in patients with schizophrenia32 or borderline personality disorder33 when administered for other reasons. However, it may reduce anxiety in patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter.30,34

Bottom Line

Serotonin-mediated anxiety occurs when levels of synaptic serotonin (5-HT) are high. Patients with serotonin-mediated anxiety appear calm but will report experiencing an unpleasant internal energy. Interventions that block multiple postsynaptic 5-HT receptors or discontinuation of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (if applicable) will alleviate the anxiety.

Related Resource

• Bhatt NV. Anxiety disorders. https://emedicine.medscape. com/article/286227-overview

Drug Brand Names

Asenapine • Saphris, Secuado

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Pregabalin • Lyrica

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Trazodone • Oleptro

1. Shelton CI. Diagnosis and management of anxiety disorders. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2004;104(3 Suppl 3):S2-S5.

2. Ruscio AM, Hallion LS, Lim CCW, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the epidemiology of DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder across the globe. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):465-475.

3. Locke AB, Kirst N, Shultz CG. Diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(9):617-624.

4. Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, et al. Dextroamphetamine modulates the response of the human amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(6):1036-1040.

5. Colombo AC, de Oliveira AR, Reimer AE, et al. Dopaminergic mechanisms underlying catalepsy, fear and anxiety: do they interact? Behav Brain Res. 2013;257:201-207.

6. Togay B, El-Mallakh RS. Posttraumatic stress disorder: from pathophysiology to pharmacology. Curr Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):33-39.

7. Provensi G, Passani MB, Costa A, et al. Neuronal histamine and the memory of emotionally salient events. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(3):557-569.

8. Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al (eds). Neuroscience. 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates; 2001.

9. Pytliak M, Vargová V, Mechírová V, et al. Serotonin receptors – from molecular biology to clinical applications. Physiol Res. 2011;60(1):15-25.

10. Meneses A, Liy-Salmeron G. Serotonin and emotion, learning and memory. Rev Neurosci. 2012;23(5-6):543-553.

11. Whitaker-Azmitia PM. Serotonin and brain development: role in human developmental diseases. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56(5):479-485.

12. Towle AC, Breese GR, Mueller RA, et al. Early postnatal administration of 5,7-DHT: effects on serotonergic neurons and terminals. Brain Res. 1984;310(1):67-75.

13. Rok-Bujko P, Krzs´cik P, Szyndler J, et al. The influence of neonatal serotonin depletion on emotional and exploratory behaviours in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2012;226(1):87-95.

14. Meltzer HY. The role of serotonin in antipsychotic drug action. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(2 Suppl):106S-115S.

15. Calabrese EJ. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin): biphasic dose responses. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2001;31(4-5):553-561.

16. Zuardi AW. 5-HT-related drugs and human experimental anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1990;14(4):507-510.

17. Sánchez C, Meier E. Behavioral profiles of SSRIs in animal models of depression, anxiety and aggression. Are they all alike? Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1997;129(3):197-205.

18. Koek W, Mitchell NC, Daws LC. Biphasic effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on anxiety: rapid reversal of escitalopram’s anxiogenic effects in the novelty-induced hypophagia test in mice? Behav Pharmacol. 2018;29(4):365-369.

19. van Zijderveld GA, Veltman DJ, van Dyck R, et al. Epinephrine-induced panic attacks and hyperventilation. J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33(1):73-78.

20. Ho EV, Thompson SL, Katzka WR, et al. Clinically effective OCD treatment prevents 5-HT1B receptor-induced repetitive behavior and striatal activation. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(1):57-70.

21. Stein DJ, Costa DLC, Lochner C, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):52.

22. Luddington NS, Mandadapu A, Husk M, et al. Clinical implications of genetic variation in the serotonin transporter promoter region: a review. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(3):93-102.

23. Stahl SM. Mechanism of action of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors. Serotonin receptors and pathways mediate therapeutic effects and side effects. J Affect Disord. 1998;51(3):215-235.

24. Chaouloff F, Berton O, Mormède P. Serotonin and stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(2 Suppl):28S-32S.

25. Siafis S, Tzachanis D, Samara M, et al. Antipsychotic drugs: From receptor-binding profiles to metabolic side effects. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16(8):1210-1223.

26. Carrithers B, El-Mallakh RS. Transdermal asenapine in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:1541-1551.

27. Citrome L. Asenapine review, part I: chemistry, receptor affinity profile, pharmacokinetics and metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10(6):893-903.

28. Pratts M, Citrome L, Grant W, et al. A single-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sublingual asenapine for acute agitation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(1):61-68.

29. Biswas AB, Bhaumik S, Branford D. Treatment-emergent behavioural side effects with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in adults with learning disabilities. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(2):133-137.

30. Perlis RH, Mischoulon D, Smoller JW, et al. Serotonin transporter polymorphisms and adverse effects with fluoxetine treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(9):879-883.

31. Ipser JC, Carey P, Dhansay Y, et al. Pharmacotherapy augmentation strategies in treatment-resistant anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD005473.

32. Kane JM, Mackle M, Snow-Adami L, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of asenapine for the prevention of relapse of schizophrenia after long-term treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):349-355.

33. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819.

34. El-Mallakh RS, Nuss S, Gao D, et al. Asenapine in the treatment of bipolar depression. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2020;50(1):8-18.

Sara R. Abell, MD, and Rif S. El-Mallakh, MD

Individuals with anxiety will experience frequent or chronic excessive worry, nervousness, a sense of unease, a feeling of being unfocused, and distress, which result in functional impairment.1 Frequently, anxiety is accompanied by restlessness or muscle tension. Generalized anxiety disorder is one of the most common psychiatric diagnoses in the United States and has a prevalence of 2% to 6% globally.2 Although research has been conducted regarding anxiety’s pathogenesis, to date a firm consensus on its etiology has not been reached.3 It is likely multifactorial, with environmental and biologic components.

One area of focus has been neurotransmitters and the possible role they play in the pathogenesis of anxiety. Specifically, the monoamine neurotransmitters have been implicated in the clinical manifestations of anxiety. Among the amines, normal roles include stimulating the autonomic nervous system and regulating numerous cognitive phenomena, such as volition and emotion. Many psychiatric medications modify aminergic transmission, and many current anxiety medications target amine neurotransmitters. Medications that target histamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine all play a role in treating anxiety.

In this article, we focus on serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) as a mediator of anxiety and on excessive synaptic 5-HT as the cause of anxiety. We discuss how 5-HT–mediated anxiety can be identified and offer some solutions for its treatment.

The amine neurotransmitters

There are 6 amine neurotransmitters in the CNS. These are derived from tyrosine (dopamine [DA], norepinephrine [NE], and epinephrine), histidine (histamine), and tryptophan (serotonin [5-HT] and melatonin). In addition to their physiologic actions, amines have been implicated in both acute and chronic anxiety. Excessive DA stimulation has been linked with fear4,5; NE elevations are central to hypervigilance and hyperarousal of posttraumatic stress disorder6; and histamine may mediate emotional memories involved in fear and anxiety.7 Understanding the normal function of 5-HT will aid in understanding its potential problematic role (Box,8-18page 38).

How serotonin-mediated anxiety presents

“Anxiety” is a collection of signs and symptoms that likely represent multiple processes and have the common characteristic of being subjectively unpleasant, with a subjective wish for the feeling to end. The expression of anxiety disorders is quite diverse and ranges from brief episodes such as panic attacks (which may be mediated, in part, by epinephrine/NE19) to lifelong stereotypic obsessions and compulsions (which may be mediated, in part, by DA and modified by 5-HT20,21). Biochemical separation of the anxiety disorders is key to achieving tailored treatment.6 Towards this end, it is important to investigate the phenomenon of serotonin-mediated anxiety.

Because clinicians are familiar with reductions of anxiety as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) increase 5-HT levels in the synapse, it is difficult to conceptualize serotonin-mediated anxiety. However, many of the effects at postsynaptic 5-HT receptors may be biphasic.15-18 Serotonin-mediated anxiety appears to occur when levels of 5-HT (or stimulation of 5-HT receptors) are particularly high. This is most frequently seen in patients who genetically have high synaptic 5-HT (by virtue of the short form of the 5-HT transporter),22 whose synaptic 5-HT is further increased by treatment with an SSRI,23 and who are experiencing a stressor that yet further increases their synaptic 5-HT.24 However, it may occur in some individuals with only 2 of these 3 conditions.Clinically, individuals with serotonin-mediated anxiety will usually appear calm. The anxiety they are experiencing is not exhibited in any way in the motor system (ie, they do not appear restless, do not pace, muscle tone is not increased, etc.). However, they will generally complain of an internal agitation, a sense of a negative internal energy. Frequently, they will use descriptions such as “I feel I could jump out of my skin.” As previously mentioned, this is usually in the setting of some environmental stress, in addition to either a pharmacologic (SSRI) or genetic (short form of the 5-HT transporter) reason for increasing synaptic 5-HT, or both.

Almost always, interventions that block multiple postsynaptic 5-HT receptors or discontinuation of the SSRI (if applicable) will alleviate the anxiety, quickly or more slowly, respectively. Sublingual asenapine, which at low doses can block 5-HT2C (Ki = 0.03 nM), 5-HT2A (Ki = 0.07 nM), 5-HT7 (Ki = 0.11 nM), 5-HT2B (Ki = 0.18 nM), and 5-HT6 (Ki = 0.25 nM),25,26 and which will produce peak plasma levels within 10 minutes,27 usually is quite effective.

Box

Serotonin (5-HT) arises from neurons in the raphe nuclei of the rostral pons and projects superiorly to the cerebral cortex and inferiorly to the spinal cord.8 It works in an inhibitory or excitatory manner depending on which receptors are activated. In the periphery, 5-HT influences intestinal peristalsis, sensory modulation, gland function, thermoregulation, blood pressure, platelet aggregation, and sexual behavior,9 all actions that produce potential adverse effects of serotonin reuptake– inhibiting antidepressants. In the CNS, 5-HT plays a role in attention bias; decision-making; sleep and wakefulness; and mood regulation. In short, serotonin can be viewed as mediating emotional motivation.10

Serotonin alters neuroplasticity. During development, 5-HT stimulates creation of new synapses and increases the density of synaptic webs. It has a direct stimulatory effect on the length of dendrites, their branching, and their myelination.11 In the CNS, it plays a role in dendritic arborization. Animal studies with rats have shown that lesioning highly concentrated 5-HT areas at early ages resulted in an adult brain with a lower number of neurons and a less complex web of dendrites.12,13 In situations of emotional stress, it is theorized that low levels of 5-HT lead to a reduced ability to deal with emotional stressors due to lower levels of complexity in synaptic connections.

Serotonin has also been implicated in mediating some aspects of dopamine-related actions, such as locomotion, reward, and threat avoidance. This is believed to contribute to the beneficial effect of 5-HT2A blockade by secondgeneration antipsychotics (SGAs).14 Blockade of other 5-HT receptors, such as 5-HT1A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7, may also contribute to the antipsychotic action of SGAs.14

Serotonin receptors are found throughout the body, and 14 subtypes have been identified.9 Excitatory and inhibitory action of 5-HT depends on the receptor, and the actions of 5-HT can differ with the same receptor at different concentrations. This is because serotonin’s effects are biphasic and concentration-dependent, meaning that levels of 5-HT in the synapse will dictate the downstream effect of receptor agonism or antagonism. Animal models have shown that low-dose agonism of 5-HT receptors causes vasoconstriction of the coronary arteries, and high doses cause relaxation. This response has also been demonstrated in the vasculature of the kidneys and the smooth muscle of the trachea. Additionally, 5-HT works in conjunction with histamine to produce a biphasic response in the colonic arteries and veins in situations of endothelial damage.15

Most relevant to this discussion are 5-HT’s actions in mood regulation and behavior. Low 5-HT states result in less behavioral inhibition, leading to higher impulse control failures and aggression. Experiments in mice with deficient serotonergic brain regions show hypoactivity, extended daytime sleep, anxiety, and depressive behaviors.13 Serotonin’s behavioral effects are also biphasic. For example, lowdose antagonism with trazodone of 5-HT receptors demonstrated a pro-aggressive behavioral effect, while high-dose antagonism is anti-aggressive.15 Similar biphasic effects may result in either induction or reduction of anxiety with agents that block or excite certain 5-HT receptors.16-18

Continue to: A key difference: No motor system involvement...

A key difference: No motor system involvement

What distinguishes 5-HT from the other amine transmitters as a mediator of anxiety is the lack of involvement of the motor system. Multiple studies in rats illustrate that exogenously augmenting 5-HT has no effect on levels of locomotor activity. Dopamine depletion is well-characterized in the motor dysfunction of Parkinson’s disease, and DA excess can cause repetitive, stereotyped movements, such as seen in tardive dyskinesia or Huntington’s disease.8 In humans, serotonin-mediated anxiety is usually without a motoric component; patients appear calm but complain of extreme anxiety or agitation. Agitation has been reported after initiation of an SSRI,29 and is more likely to occur in patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter.30 Motoric activation has been reported in some of these studies, but does not seem to cluster with the complaint of agitation.29 The reduced number of available transporters means a chronic steady-state elevation of serotonin, because less serotonin is being removed from the synapse after it is released. This is one of the reasons patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter may be more susceptible to serotonin-mediated anxiety.

What you need to keep in mind

Pharmacologic treatment of anxiety begins with an SSRI, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), or buspirone. Second-line treatments include hydroxyzine, gabapentin, pregabalin, and quetiapine.3,31 However, clinicians need to be aware that a fraction of their patients will report anxiety that will not have any external manifestations, but will be experienced as an unpleasant internal energy. These patients may report an increase in their anxiety levels when started on an SSRI or SNRI.29,30 This anxiety is most likely mediated by increases of synaptic 5-HT. This occurs because many serotonergic receptors may have a biphasic response, so that too much stimulation is experienced as excessive internal energy.16-18 In such patients, blockade of key 5-HT receptors may reduce that internal agitation. The advantage of recognizing serotonin-mediated anxiety is that one can specifically tailor treatment to address the patient’s specific physiology.

It is important to note that the anxiolytic effect of asenapine is specific to patients with serotonin-mediated anxiety. Unlike quetiapine, which is effective as augmentation therapy in generalized anxiety disorder,31 asenapine does not appear to reduce anxiety in patients with schizophrenia32 or borderline personality disorder33 when administered for other reasons. However, it may reduce anxiety in patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter.30,34

Bottom Line

Serotonin-mediated anxiety occurs when levels of synaptic serotonin (5-HT) are high. Patients with serotonin-mediated anxiety appear calm but will report experiencing an unpleasant internal energy. Interventions that block multiple postsynaptic 5-HT receptors or discontinuation of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (if applicable) will alleviate the anxiety.

Related Resource

• Bhatt NV. Anxiety disorders. https://emedicine.medscape. com/article/286227-overview

Drug Brand Names

Asenapine • Saphris, Secuado

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Pregabalin • Lyrica

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Trazodone • Oleptro

Sara R. Abell, MD, and Rif S. El-Mallakh, MD

Individuals with anxiety will experience frequent or chronic excessive worry, nervousness, a sense of unease, a feeling of being unfocused, and distress, which result in functional impairment.1 Frequently, anxiety is accompanied by restlessness or muscle tension. Generalized anxiety disorder is one of the most common psychiatric diagnoses in the United States and has a prevalence of 2% to 6% globally.2 Although research has been conducted regarding anxiety’s pathogenesis, to date a firm consensus on its etiology has not been reached.3 It is likely multifactorial, with environmental and biologic components.

One area of focus has been neurotransmitters and the possible role they play in the pathogenesis of anxiety. Specifically, the monoamine neurotransmitters have been implicated in the clinical manifestations of anxiety. Among the amines, normal roles include stimulating the autonomic nervous system and regulating numerous cognitive phenomena, such as volition and emotion. Many psychiatric medications modify aminergic transmission, and many current anxiety medications target amine neurotransmitters. Medications that target histamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine all play a role in treating anxiety.

In this article, we focus on serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) as a mediator of anxiety and on excessive synaptic 5-HT as the cause of anxiety. We discuss how 5-HT–mediated anxiety can be identified and offer some solutions for its treatment.

The amine neurotransmitters

There are 6 amine neurotransmitters in the CNS. These are derived from tyrosine (dopamine [DA], norepinephrine [NE], and epinephrine), histidine (histamine), and tryptophan (serotonin [5-HT] and melatonin). In addition to their physiologic actions, amines have been implicated in both acute and chronic anxiety. Excessive DA stimulation has been linked with fear4,5; NE elevations are central to hypervigilance and hyperarousal of posttraumatic stress disorder6; and histamine may mediate emotional memories involved in fear and anxiety.7 Understanding the normal function of 5-HT will aid in understanding its potential problematic role (Box,8-18page 38).

How serotonin-mediated anxiety presents

“Anxiety” is a collection of signs and symptoms that likely represent multiple processes and have the common characteristic of being subjectively unpleasant, with a subjective wish for the feeling to end. The expression of anxiety disorders is quite diverse and ranges from brief episodes such as panic attacks (which may be mediated, in part, by epinephrine/NE19) to lifelong stereotypic obsessions and compulsions (which may be mediated, in part, by DA and modified by 5-HT20,21). Biochemical separation of the anxiety disorders is key to achieving tailored treatment.6 Towards this end, it is important to investigate the phenomenon of serotonin-mediated anxiety.

Because clinicians are familiar with reductions of anxiety as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) increase 5-HT levels in the synapse, it is difficult to conceptualize serotonin-mediated anxiety. However, many of the effects at postsynaptic 5-HT receptors may be biphasic.15-18 Serotonin-mediated anxiety appears to occur when levels of 5-HT (or stimulation of 5-HT receptors) are particularly high. This is most frequently seen in patients who genetically have high synaptic 5-HT (by virtue of the short form of the 5-HT transporter),22 whose synaptic 5-HT is further increased by treatment with an SSRI,23 and who are experiencing a stressor that yet further increases their synaptic 5-HT.24 However, it may occur in some individuals with only 2 of these 3 conditions.Clinically, individuals with serotonin-mediated anxiety will usually appear calm. The anxiety they are experiencing is not exhibited in any way in the motor system (ie, they do not appear restless, do not pace, muscle tone is not increased, etc.). However, they will generally complain of an internal agitation, a sense of a negative internal energy. Frequently, they will use descriptions such as “I feel I could jump out of my skin.” As previously mentioned, this is usually in the setting of some environmental stress, in addition to either a pharmacologic (SSRI) or genetic (short form of the 5-HT transporter) reason for increasing synaptic 5-HT, or both.

Almost always, interventions that block multiple postsynaptic 5-HT receptors or discontinuation of the SSRI (if applicable) will alleviate the anxiety, quickly or more slowly, respectively. Sublingual asenapine, which at low doses can block 5-HT2C (Ki = 0.03 nM), 5-HT2A (Ki = 0.07 nM), 5-HT7 (Ki = 0.11 nM), 5-HT2B (Ki = 0.18 nM), and 5-HT6 (Ki = 0.25 nM),25,26 and which will produce peak plasma levels within 10 minutes,27 usually is quite effective.

Box

Serotonin (5-HT) arises from neurons in the raphe nuclei of the rostral pons and projects superiorly to the cerebral cortex and inferiorly to the spinal cord.8 It works in an inhibitory or excitatory manner depending on which receptors are activated. In the periphery, 5-HT influences intestinal peristalsis, sensory modulation, gland function, thermoregulation, blood pressure, platelet aggregation, and sexual behavior,9 all actions that produce potential adverse effects of serotonin reuptake– inhibiting antidepressants. In the CNS, 5-HT plays a role in attention bias; decision-making; sleep and wakefulness; and mood regulation. In short, serotonin can be viewed as mediating emotional motivation.10

Serotonin alters neuroplasticity. During development, 5-HT stimulates creation of new synapses and increases the density of synaptic webs. It has a direct stimulatory effect on the length of dendrites, their branching, and their myelination.11 In the CNS, it plays a role in dendritic arborization. Animal studies with rats have shown that lesioning highly concentrated 5-HT areas at early ages resulted in an adult brain with a lower number of neurons and a less complex web of dendrites.12,13 In situations of emotional stress, it is theorized that low levels of 5-HT lead to a reduced ability to deal with emotional stressors due to lower levels of complexity in synaptic connections.

Serotonin has also been implicated in mediating some aspects of dopamine-related actions, such as locomotion, reward, and threat avoidance. This is believed to contribute to the beneficial effect of 5-HT2A blockade by secondgeneration antipsychotics (SGAs).14 Blockade of other 5-HT receptors, such as 5-HT1A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7, may also contribute to the antipsychotic action of SGAs.14

Serotonin receptors are found throughout the body, and 14 subtypes have been identified.9 Excitatory and inhibitory action of 5-HT depends on the receptor, and the actions of 5-HT can differ with the same receptor at different concentrations. This is because serotonin’s effects are biphasic and concentration-dependent, meaning that levels of 5-HT in the synapse will dictate the downstream effect of receptor agonism or antagonism. Animal models have shown that low-dose agonism of 5-HT receptors causes vasoconstriction of the coronary arteries, and high doses cause relaxation. This response has also been demonstrated in the vasculature of the kidneys and the smooth muscle of the trachea. Additionally, 5-HT works in conjunction with histamine to produce a biphasic response in the colonic arteries and veins in situations of endothelial damage.15

Most relevant to this discussion are 5-HT’s actions in mood regulation and behavior. Low 5-HT states result in less behavioral inhibition, leading to higher impulse control failures and aggression. Experiments in mice with deficient serotonergic brain regions show hypoactivity, extended daytime sleep, anxiety, and depressive behaviors.13 Serotonin’s behavioral effects are also biphasic. For example, lowdose antagonism with trazodone of 5-HT receptors demonstrated a pro-aggressive behavioral effect, while high-dose antagonism is anti-aggressive.15 Similar biphasic effects may result in either induction or reduction of anxiety with agents that block or excite certain 5-HT receptors.16-18

Continue to: A key difference: No motor system involvement...

A key difference: No motor system involvement

What distinguishes 5-HT from the other amine transmitters as a mediator of anxiety is the lack of involvement of the motor system. Multiple studies in rats illustrate that exogenously augmenting 5-HT has no effect on levels of locomotor activity. Dopamine depletion is well-characterized in the motor dysfunction of Parkinson’s disease, and DA excess can cause repetitive, stereotyped movements, such as seen in tardive dyskinesia or Huntington’s disease.8 In humans, serotonin-mediated anxiety is usually without a motoric component; patients appear calm but complain of extreme anxiety or agitation. Agitation has been reported after initiation of an SSRI,29 and is more likely to occur in patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter.30 Motoric activation has been reported in some of these studies, but does not seem to cluster with the complaint of agitation.29 The reduced number of available transporters means a chronic steady-state elevation of serotonin, because less serotonin is being removed from the synapse after it is released. This is one of the reasons patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter may be more susceptible to serotonin-mediated anxiety.

What you need to keep in mind

Pharmacologic treatment of anxiety begins with an SSRI, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), or buspirone. Second-line treatments include hydroxyzine, gabapentin, pregabalin, and quetiapine.3,31 However, clinicians need to be aware that a fraction of their patients will report anxiety that will not have any external manifestations, but will be experienced as an unpleasant internal energy. These patients may report an increase in their anxiety levels when started on an SSRI or SNRI.29,30 This anxiety is most likely mediated by increases of synaptic 5-HT. This occurs because many serotonergic receptors may have a biphasic response, so that too much stimulation is experienced as excessive internal energy.16-18 In such patients, blockade of key 5-HT receptors may reduce that internal agitation. The advantage of recognizing serotonin-mediated anxiety is that one can specifically tailor treatment to address the patient’s specific physiology.

It is important to note that the anxiolytic effect of asenapine is specific to patients with serotonin-mediated anxiety. Unlike quetiapine, which is effective as augmentation therapy in generalized anxiety disorder,31 asenapine does not appear to reduce anxiety in patients with schizophrenia32 or borderline personality disorder33 when administered for other reasons. However, it may reduce anxiety in patients with the short form of the 5-HT transporter.30,34

Bottom Line

Serotonin-mediated anxiety occurs when levels of synaptic serotonin (5-HT) are high. Patients with serotonin-mediated anxiety appear calm but will report experiencing an unpleasant internal energy. Interventions that block multiple postsynaptic 5-HT receptors or discontinuation of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (if applicable) will alleviate the anxiety.

Related Resource

• Bhatt NV. Anxiety disorders. https://emedicine.medscape. com/article/286227-overview

Drug Brand Names

Asenapine • Saphris, Secuado

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Pregabalin • Lyrica

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Trazodone • Oleptro

1. Shelton CI. Diagnosis and management of anxiety disorders. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2004;104(3 Suppl 3):S2-S5.

2. Ruscio AM, Hallion LS, Lim CCW, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the epidemiology of DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder across the globe. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):465-475.

3. Locke AB, Kirst N, Shultz CG. Diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(9):617-624.

4. Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, et al. Dextroamphetamine modulates the response of the human amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(6):1036-1040.

5. Colombo AC, de Oliveira AR, Reimer AE, et al. Dopaminergic mechanisms underlying catalepsy, fear and anxiety: do they interact? Behav Brain Res. 2013;257:201-207.

6. Togay B, El-Mallakh RS. Posttraumatic stress disorder: from pathophysiology to pharmacology. Curr Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):33-39.

7. Provensi G, Passani MB, Costa A, et al. Neuronal histamine and the memory of emotionally salient events. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(3):557-569.

8. Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al (eds). Neuroscience. 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates; 2001.

9. Pytliak M, Vargová V, Mechírová V, et al. Serotonin receptors – from molecular biology to clinical applications. Physiol Res. 2011;60(1):15-25.

10. Meneses A, Liy-Salmeron G. Serotonin and emotion, learning and memory. Rev Neurosci. 2012;23(5-6):543-553.

11. Whitaker-Azmitia PM. Serotonin and brain development: role in human developmental diseases. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56(5):479-485.

12. Towle AC, Breese GR, Mueller RA, et al. Early postnatal administration of 5,7-DHT: effects on serotonergic neurons and terminals. Brain Res. 1984;310(1):67-75.

13. Rok-Bujko P, Krzs´cik P, Szyndler J, et al. The influence of neonatal serotonin depletion on emotional and exploratory behaviours in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2012;226(1):87-95.

14. Meltzer HY. The role of serotonin in antipsychotic drug action. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(2 Suppl):106S-115S.

15. Calabrese EJ. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin): biphasic dose responses. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2001;31(4-5):553-561.

16. Zuardi AW. 5-HT-related drugs and human experimental anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1990;14(4):507-510.

17. Sánchez C, Meier E. Behavioral profiles of SSRIs in animal models of depression, anxiety and aggression. Are they all alike? Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1997;129(3):197-205.

18. Koek W, Mitchell NC, Daws LC. Biphasic effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on anxiety: rapid reversal of escitalopram’s anxiogenic effects in the novelty-induced hypophagia test in mice? Behav Pharmacol. 2018;29(4):365-369.

19. van Zijderveld GA, Veltman DJ, van Dyck R, et al. Epinephrine-induced panic attacks and hyperventilation. J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33(1):73-78.

20. Ho EV, Thompson SL, Katzka WR, et al. Clinically effective OCD treatment prevents 5-HT1B receptor-induced repetitive behavior and striatal activation. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(1):57-70.

21. Stein DJ, Costa DLC, Lochner C, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):52.

22. Luddington NS, Mandadapu A, Husk M, et al. Clinical implications of genetic variation in the serotonin transporter promoter region: a review. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(3):93-102.

23. Stahl SM. Mechanism of action of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors. Serotonin receptors and pathways mediate therapeutic effects and side effects. J Affect Disord. 1998;51(3):215-235.

24. Chaouloff F, Berton O, Mormède P. Serotonin and stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(2 Suppl):28S-32S.

25. Siafis S, Tzachanis D, Samara M, et al. Antipsychotic drugs: From receptor-binding profiles to metabolic side effects. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16(8):1210-1223.

26. Carrithers B, El-Mallakh RS. Transdermal asenapine in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:1541-1551.

27. Citrome L. Asenapine review, part I: chemistry, receptor affinity profile, pharmacokinetics and metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10(6):893-903.

28. Pratts M, Citrome L, Grant W, et al. A single-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sublingual asenapine for acute agitation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(1):61-68.

29. Biswas AB, Bhaumik S, Branford D. Treatment-emergent behavioural side effects with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in adults with learning disabilities. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(2):133-137.

30. Perlis RH, Mischoulon D, Smoller JW, et al. Serotonin transporter polymorphisms and adverse effects with fluoxetine treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(9):879-883.

31. Ipser JC, Carey P, Dhansay Y, et al. Pharmacotherapy augmentation strategies in treatment-resistant anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD005473.

32. Kane JM, Mackle M, Snow-Adami L, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of asenapine for the prevention of relapse of schizophrenia after long-term treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):349-355.

33. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819.

34. El-Mallakh RS, Nuss S, Gao D, et al. Asenapine in the treatment of bipolar depression. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2020;50(1):8-18.

1. Shelton CI. Diagnosis and management of anxiety disorders. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2004;104(3 Suppl 3):S2-S5.

2. Ruscio AM, Hallion LS, Lim CCW, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the epidemiology of DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder across the globe. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):465-475.

3. Locke AB, Kirst N, Shultz CG. Diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(9):617-624.

4. Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, et al. Dextroamphetamine modulates the response of the human amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(6):1036-1040.

5. Colombo AC, de Oliveira AR, Reimer AE, et al. Dopaminergic mechanisms underlying catalepsy, fear and anxiety: do they interact? Behav Brain Res. 2013;257:201-207.

6. Togay B, El-Mallakh RS. Posttraumatic stress disorder: from pathophysiology to pharmacology. Curr Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):33-39.

7. Provensi G, Passani MB, Costa A, et al. Neuronal histamine and the memory of emotionally salient events. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(3):557-569.

8. Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al (eds). Neuroscience. 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates; 2001.

9. Pytliak M, Vargová V, Mechírová V, et al. Serotonin receptors – from molecular biology to clinical applications. Physiol Res. 2011;60(1):15-25.

10. Meneses A, Liy-Salmeron G. Serotonin and emotion, learning and memory. Rev Neurosci. 2012;23(5-6):543-553.

11. Whitaker-Azmitia PM. Serotonin and brain development: role in human developmental diseases. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56(5):479-485.

12. Towle AC, Breese GR, Mueller RA, et al. Early postnatal administration of 5,7-DHT: effects on serotonergic neurons and terminals. Brain Res. 1984;310(1):67-75.

13. Rok-Bujko P, Krzs´cik P, Szyndler J, et al. The influence of neonatal serotonin depletion on emotional and exploratory behaviours in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2012;226(1):87-95.

14. Meltzer HY. The role of serotonin in antipsychotic drug action. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(2 Suppl):106S-115S.

15. Calabrese EJ. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin): biphasic dose responses. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2001;31(4-5):553-561.

16. Zuardi AW. 5-HT-related drugs and human experimental anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1990;14(4):507-510.

17. Sánchez C, Meier E. Behavioral profiles of SSRIs in animal models of depression, anxiety and aggression. Are they all alike? Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1997;129(3):197-205.

18. Koek W, Mitchell NC, Daws LC. Biphasic effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on anxiety: rapid reversal of escitalopram’s anxiogenic effects in the novelty-induced hypophagia test in mice? Behav Pharmacol. 2018;29(4):365-369.

19. van Zijderveld GA, Veltman DJ, van Dyck R, et al. Epinephrine-induced panic attacks and hyperventilation. J Psychiatr Res. 1999;33(1):73-78.

20. Ho EV, Thompson SL, Katzka WR, et al. Clinically effective OCD treatment prevents 5-HT1B receptor-induced repetitive behavior and striatal activation. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(1):57-70.

21. Stein DJ, Costa DLC, Lochner C, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):52.

22. Luddington NS, Mandadapu A, Husk M, et al. Clinical implications of genetic variation in the serotonin transporter promoter region: a review. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(3):93-102.

23. Stahl SM. Mechanism of action of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors. Serotonin receptors and pathways mediate therapeutic effects and side effects. J Affect Disord. 1998;51(3):215-235.

24. Chaouloff F, Berton O, Mormède P. Serotonin and stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(2 Suppl):28S-32S.

25. Siafis S, Tzachanis D, Samara M, et al. Antipsychotic drugs: From receptor-binding profiles to metabolic side effects. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16(8):1210-1223.

26. Carrithers B, El-Mallakh RS. Transdermal asenapine in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:1541-1551.

27. Citrome L. Asenapine review, part I: chemistry, receptor affinity profile, pharmacokinetics and metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10(6):893-903.

28. Pratts M, Citrome L, Grant W, et al. A single-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sublingual asenapine for acute agitation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(1):61-68.

29. Biswas AB, Bhaumik S, Branford D. Treatment-emergent behavioural side effects with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in adults with learning disabilities. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(2):133-137.

30. Perlis RH, Mischoulon D, Smoller JW, et al. Serotonin transporter polymorphisms and adverse effects with fluoxetine treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(9):879-883.

31. Ipser JC, Carey P, Dhansay Y, et al. Pharmacotherapy augmentation strategies in treatment-resistant anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD005473.

32. Kane JM, Mackle M, Snow-Adami L, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of asenapine for the prevention of relapse of schizophrenia after long-term treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):349-355.

33. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819.

34. El-Mallakh RS, Nuss S, Gao D, et al. Asenapine in the treatment of bipolar depression. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2020;50(1):8-18.

Dealing with a difficult boss: A ‘bossectomy’ is rarely the cure

Ms. D is a 48-year-old administrative assistant and married mother of 2 teenagers with a history of adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood. She presents with increasing anxiety, poor sleep, irritability, and occasional feelings of hopelessness in the context of feeling stuck in a “dead-end job.” She describes her main issue as having an uncaring boss with unrealistic expectations. Clearly exasperated, she tells you, “If only I could get rid of my boss, everything would be just fine.”

Ms. D’s situation is common. When confronted with overbearing and demanding supervisors, the natural inclination for some employees is to flee. Symptoms of burnout (eg, emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased personal accomplishment) often occur, sometimes with more serious symptoms of adjustment disorder or even major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder. To help patients such as Ms. D who are experiencing difficulties with their boss, you can use a simple approach aimed at helping them make the decision to stay at the job or leave for other opportunities, while supporting them along the way.

Clarify, then support and explore

A critical addition to the typical evaluation is a full social history, including prior employment and formative relationships, that may inform current workplace dynamics. Does the patient have a pattern of similar circumstances, or is this unusual for her? How does she view the supervisor-employee relationship, and how do power differentials, potential job loss, and subsequent financial impacts further amplify emotional friction?

Once the dynamics are clarified, support and validate her emotional reaction before exploring potential cognitive distortions and her own contributions to the relationship dysfunction. If her tendency is to lash out in anger, she could fan the flames and risk being fired. If her tendency is to cower or freeze, you can help to gradually empower her. Regardless of relationship dynamics, be careful not to medicalize what may simply be a difficult situation.1 Perhaps she is a perfectionist and minimizes her supervisor’s behaviors that affirm her work and value as a person. In such cases, you can use cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques to help her consider different points of view and nuance. Rarely are people all good or all bad.

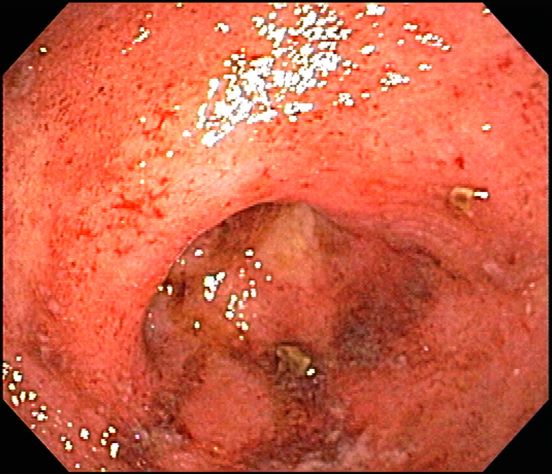

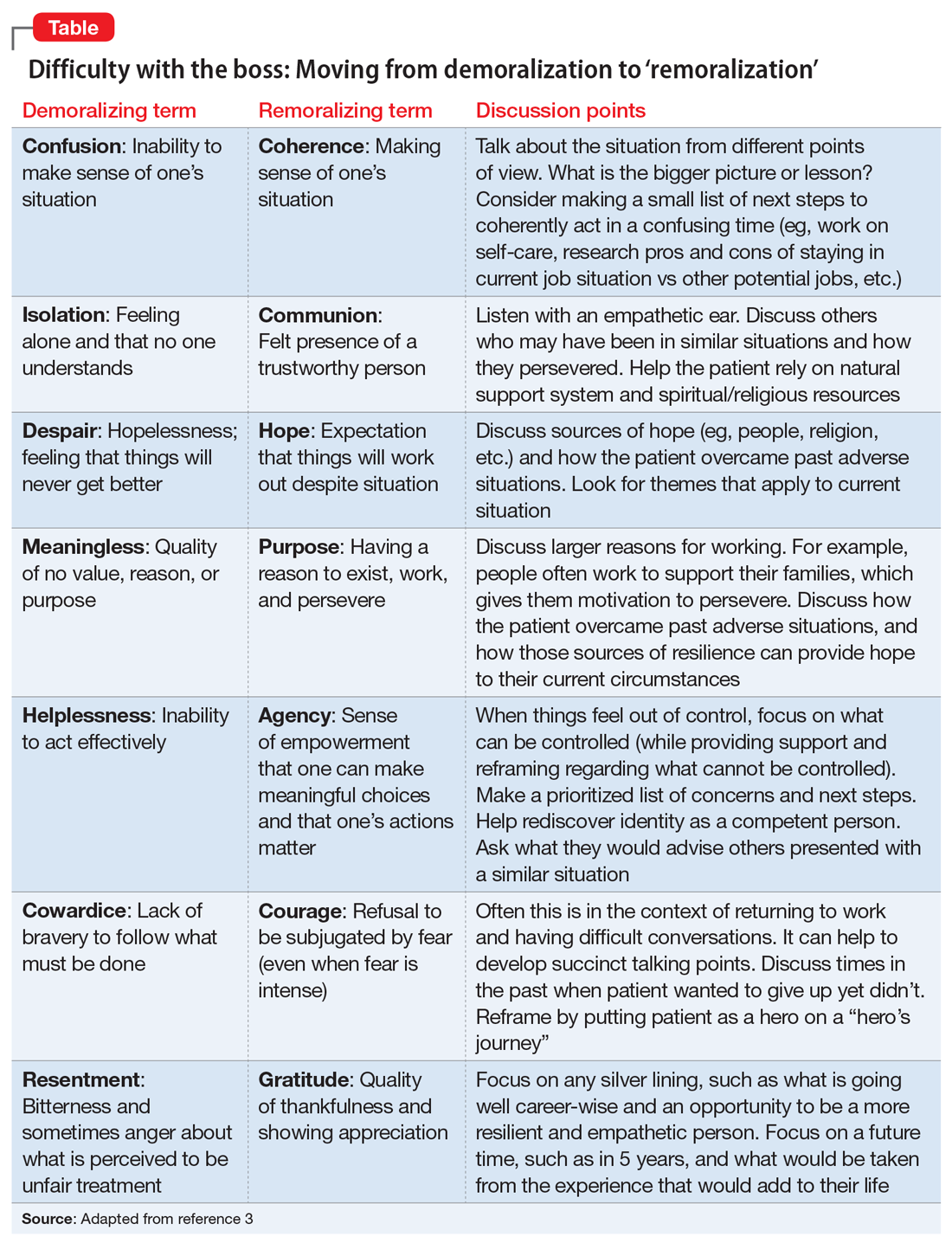

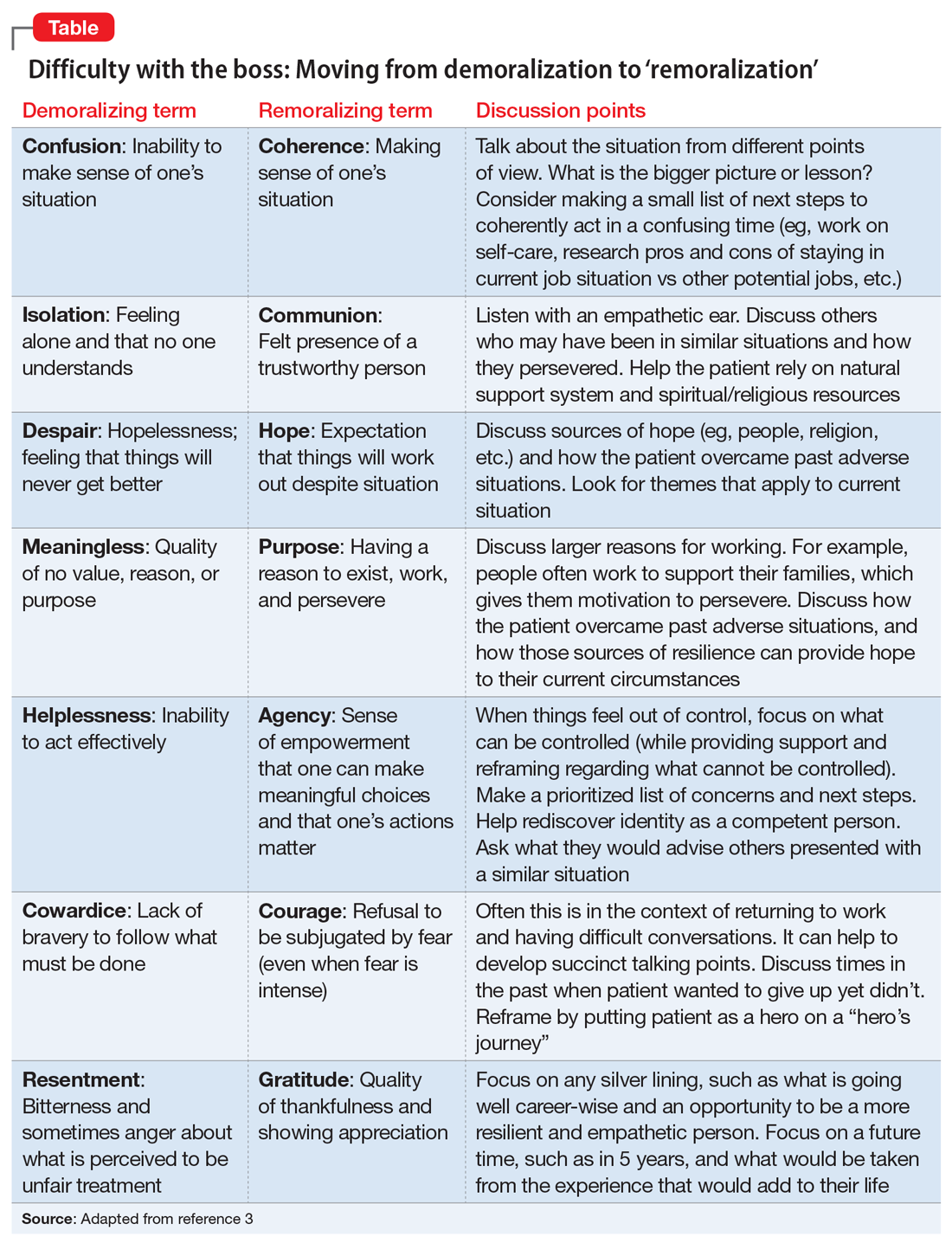

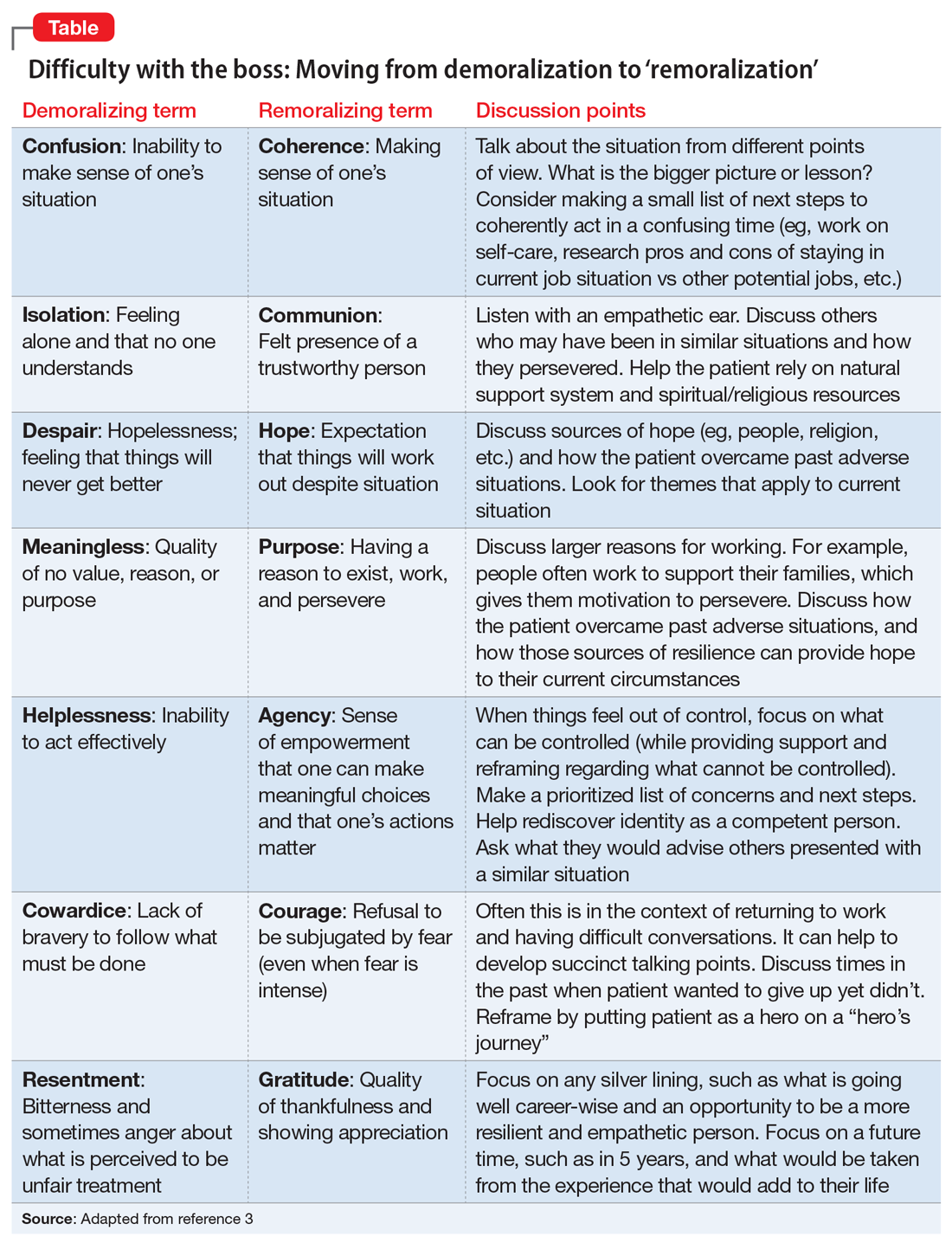

Perhaps her perceptions are accurate, and her boss really is a jerk. If this is the case, she likely feels unfairly and helplessly persecuted. She may be suffering from demoralization, or feelings of impotence, isolation, and despair in which her self-esteem is damaged and she feels rejected because of her failure to meet her boss’s and her own expectations.2 In cases of demoralization, oddly enough, hospice literature lends some tools to help her. The Table3 provides some common terms associated with demoralization and discussion points you can use to help her move toward “remoralization.”

Regardless of the full story, it’s common for people to externalize uncomfortable emotions and attribute symptoms to an external cause. Help her develop self-efficacy by realizing she is in control of how she responds to her emotions. Have her focus on her role in the relationship with her supervisor, looking for common ground and brainstorming practical solutions. Ultimately you can help her realize that she always has choices about whether to stay at the job or look for work elsewhere. Your role is to support her regardless of her decision.

CASE CONTINUED

Over several visits, Ms. D begins to view the relationship with her supervisor in a different light. She has a conversation with him about what she needs to do personally and what she needs professionally from him to be successful at work. Her supervisor acknowledges he has been demanding and could be more supportive. Together they vow to communicate more clearly and regularly assess progress, including celebrating clear victories. Ms. D ultimately decides to stay at the job, and her symptoms resolve without a “bossectomy.”

1. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(6):e125-e131.

2. Frank JD. Psychotherapy: the restoration of morale. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131(3):271-274.

3. Griffith JL, Gaby L. Brief psychotherapy at the bedside: countering demoralization from medical illness. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(2):109-116.

Ms. D is a 48-year-old administrative assistant and married mother of 2 teenagers with a history of adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood. She presents with increasing anxiety, poor sleep, irritability, and occasional feelings of hopelessness in the context of feeling stuck in a “dead-end job.” She describes her main issue as having an uncaring boss with unrealistic expectations. Clearly exasperated, she tells you, “If only I could get rid of my boss, everything would be just fine.”

Ms. D’s situation is common. When confronted with overbearing and demanding supervisors, the natural inclination for some employees is to flee. Symptoms of burnout (eg, emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased personal accomplishment) often occur, sometimes with more serious symptoms of adjustment disorder or even major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder. To help patients such as Ms. D who are experiencing difficulties with their boss, you can use a simple approach aimed at helping them make the decision to stay at the job or leave for other opportunities, while supporting them along the way.

Clarify, then support and explore

A critical addition to the typical evaluation is a full social history, including prior employment and formative relationships, that may inform current workplace dynamics. Does the patient have a pattern of similar circumstances, or is this unusual for her? How does she view the supervisor-employee relationship, and how do power differentials, potential job loss, and subsequent financial impacts further amplify emotional friction?

Once the dynamics are clarified, support and validate her emotional reaction before exploring potential cognitive distortions and her own contributions to the relationship dysfunction. If her tendency is to lash out in anger, she could fan the flames and risk being fired. If her tendency is to cower or freeze, you can help to gradually empower her. Regardless of relationship dynamics, be careful not to medicalize what may simply be a difficult situation.1 Perhaps she is a perfectionist and minimizes her supervisor’s behaviors that affirm her work and value as a person. In such cases, you can use cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques to help her consider different points of view and nuance. Rarely are people all good or all bad.

Perhaps her perceptions are accurate, and her boss really is a jerk. If this is the case, she likely feels unfairly and helplessly persecuted. She may be suffering from demoralization, or feelings of impotence, isolation, and despair in which her self-esteem is damaged and she feels rejected because of her failure to meet her boss’s and her own expectations.2 In cases of demoralization, oddly enough, hospice literature lends some tools to help her. The Table3 provides some common terms associated with demoralization and discussion points you can use to help her move toward “remoralization.”

Regardless of the full story, it’s common for people to externalize uncomfortable emotions and attribute symptoms to an external cause. Help her develop self-efficacy by realizing she is in control of how she responds to her emotions. Have her focus on her role in the relationship with her supervisor, looking for common ground and brainstorming practical solutions. Ultimately you can help her realize that she always has choices about whether to stay at the job or look for work elsewhere. Your role is to support her regardless of her decision.

CASE CONTINUED

Over several visits, Ms. D begins to view the relationship with her supervisor in a different light. She has a conversation with him about what she needs to do personally and what she needs professionally from him to be successful at work. Her supervisor acknowledges he has been demanding and could be more supportive. Together they vow to communicate more clearly and regularly assess progress, including celebrating clear victories. Ms. D ultimately decides to stay at the job, and her symptoms resolve without a “bossectomy.”

Ms. D is a 48-year-old administrative assistant and married mother of 2 teenagers with a history of adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood. She presents with increasing anxiety, poor sleep, irritability, and occasional feelings of hopelessness in the context of feeling stuck in a “dead-end job.” She describes her main issue as having an uncaring boss with unrealistic expectations. Clearly exasperated, she tells you, “If only I could get rid of my boss, everything would be just fine.”

Ms. D’s situation is common. When confronted with overbearing and demanding supervisors, the natural inclination for some employees is to flee. Symptoms of burnout (eg, emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased personal accomplishment) often occur, sometimes with more serious symptoms of adjustment disorder or even major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder. To help patients such as Ms. D who are experiencing difficulties with their boss, you can use a simple approach aimed at helping them make the decision to stay at the job or leave for other opportunities, while supporting them along the way.

Clarify, then support and explore

A critical addition to the typical evaluation is a full social history, including prior employment and formative relationships, that may inform current workplace dynamics. Does the patient have a pattern of similar circumstances, or is this unusual for her? How does she view the supervisor-employee relationship, and how do power differentials, potential job loss, and subsequent financial impacts further amplify emotional friction?

Once the dynamics are clarified, support and validate her emotional reaction before exploring potential cognitive distortions and her own contributions to the relationship dysfunction. If her tendency is to lash out in anger, she could fan the flames and risk being fired. If her tendency is to cower or freeze, you can help to gradually empower her. Regardless of relationship dynamics, be careful not to medicalize what may simply be a difficult situation.1 Perhaps she is a perfectionist and minimizes her supervisor’s behaviors that affirm her work and value as a person. In such cases, you can use cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques to help her consider different points of view and nuance. Rarely are people all good or all bad.

Perhaps her perceptions are accurate, and her boss really is a jerk. If this is the case, she likely feels unfairly and helplessly persecuted. She may be suffering from demoralization, or feelings of impotence, isolation, and despair in which her self-esteem is damaged and she feels rejected because of her failure to meet her boss’s and her own expectations.2 In cases of demoralization, oddly enough, hospice literature lends some tools to help her. The Table3 provides some common terms associated with demoralization and discussion points you can use to help her move toward “remoralization.”

Regardless of the full story, it’s common for people to externalize uncomfortable emotions and attribute symptoms to an external cause. Help her develop self-efficacy by realizing she is in control of how she responds to her emotions. Have her focus on her role in the relationship with her supervisor, looking for common ground and brainstorming practical solutions. Ultimately you can help her realize that she always has choices about whether to stay at the job or look for work elsewhere. Your role is to support her regardless of her decision.

CASE CONTINUED

Over several visits, Ms. D begins to view the relationship with her supervisor in a different light. She has a conversation with him about what she needs to do personally and what she needs professionally from him to be successful at work. Her supervisor acknowledges he has been demanding and could be more supportive. Together they vow to communicate more clearly and regularly assess progress, including celebrating clear victories. Ms. D ultimately decides to stay at the job, and her symptoms resolve without a “bossectomy.”

1. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(6):e125-e131.

2. Frank JD. Psychotherapy: the restoration of morale. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131(3):271-274.

3. Griffith JL, Gaby L. Brief psychotherapy at the bedside: countering demoralization from medical illness. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(2):109-116.

1. Jurisic M, Bean M, Harbaugh J, et al. The personal physician’s role in helping patients with medical conditions stay at work or return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(6):e125-e131.

2. Frank JD. Psychotherapy: the restoration of morale. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131(3):271-274.

3. Griffith JL, Gaby L. Brief psychotherapy at the bedside: countering demoralization from medical illness. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(2):109-116.

The impact of modifiable risk factors such as diet and obesity in Pediatric MS patients

James Nicholas Brenton, M.D., is the director of the University of Virginia’s Pediatric and Young Adult MS and Related Disorders Clinic. He is also associate professor of neurology and pediatrics for clinical research and performs collaborative clinical research within the field of pediatric MS. His research focuses on pediatric demyelinating disease and autoimmune epilepsies.

As the director of a clinic focusing on pediatric and young adults MS and related disorders, how do modifiable risk factors such as obesity, smoking, et cetera, increase the risk of MS in general?

Dr. Brenton: There are several risk factors for pediatric-onset MS. When I say pediatric-onset, I'm referring to patients with clinical onset of MS prior to the age of 18 years. Some MS risk factors are not considered “modifiable,” such as genetic risks. The greatest genetic risk for MS is related to specific haplotypes in the HLA-DRB1 gene. Another risk factor that is less amenable to modification is early exposure to certain viruses, like the Epstein-Barr virus (Makhani, et al 2016).

On the other hand, there are several potentially modifiable risk factors for MS. This includes smoking - either first or second-hand smoke. In the case of pediatric MS patients, it is most often related to second-hand (or passive) smoke exposure (Lavery, et al 2019). Another example of a modifiable MS risk factor is vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D levels are influenced significantly by duration and intensity of direct exposure to sunlight, which depends (in part) on the geographic location of where you grow up. For example, those who live at higher latitudes (e.g. live further away from the equator) have less exposure to direct sunlight than a child who lives at lower latitudes (e.g. closer to the equator) (Banwell, et al 2011).

Obesity during childhood or adolescence is another modifiable risk factor for MS. Obesity’s risk for MS (like smoking) is dose-dependent – meaning, the more obese that you are, the higher your overall risk for future development of MS. In fact, the BMI in children with MS is markedly higher than their non-MS peers, and begins in early childhood, years before the clinical onset of the disease (Brenton, et al 2019).