User login

Severe obesity reduces responses to TNF inhibitors and non-TNF biologics to similar extent

There does not appear to be superiority of any type of biologic medication for patients with rheumatoid arthritis across different body mass index (BMI) groupings, with obesity and underweight both reducing the effects of the treatments after 6 months of use, according to findings from registry data on nearly 6,000 individuals.

Although interest in the precision use of biologics for RA is on the rise, few patient characteristics have been identified to inform therapeutic decisions, Joshua F. Baker, MD, of the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote.

Previous studies on the effect of obesity on RA treatments have been inconclusive, and a comparison of RA treatments across BMI categories would provide more definitive guidance, they said.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the researchers used the CorEvitas U.S. observational registry (formerly known as Corrona) to identify adults who initiated second- or third-line treatment for RA with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (n = 2,891) or non-TNFi biologics (n = 3,010) between 2001 and April 30, 2021.

The study population included adults diagnosed with RA; those with low disease activity or without a 6-month follow-up visit were excluded. BMI was categorized as underweight (less than 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5-25 kg/m2), overweight (25-30 kg/m2), obese (30-35 kg/m2), and severely obese (35 kg/m2 or higher). The three measures of response were the achievement of low disease activity (LDA), a change at least as large as the minimum clinically important difference (MCID), and the absolute change on the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) from baseline.

A total of 2,712 patients were obese or severely obese at the time of treatment initiation.

Overall, patients with severe obesity had significantly lower odds of achieving either LDA or a change at least as large as the MCID, as well as less improvement in CDAI score, compared with other BMI categories. However, in adjusted models, the differences in these outcomes for patients with severe obesity were no longer statistically significant, whereas underweight was associated with lower odds of achieving LDA (odds ratio, 0.32; P = .005) or a change at least as large as the MCID (OR, 0.40; P = .005). The adjusted model also showed lesser improvement on CDAI in underweight patients, compared with patients of normal weight (P = .006).

Stratification by TNFi and non-TNFi therapies showed no differences in clinical response rates across BMI categories.

The study represents the first evidence of a similar reduction in therapeutic response with both TNFi and non-TNFi in severely obese patients, with estimates for non-TNFi biologics that fit within the 95% confidence interval for TNFi biologics, the researchers wrote. “Our current study suggests that a lack of response among obese patients is not specific to TNFi therapies, suggesting that this phenomenon is not biologically specific to the TNF pathway.”

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the focus on patients who were not naive to biologic treatments and by the relatively small number of underweight patients (n = 57), the researchers noted. Other limitations include unaddressed mediators of the relationship between obesity and disease activity and lack of data on off-label dosing strategies.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, control for a range of confounding factors, and the direct comparison of RA therapies.

The researchers concluded that BMI should not influence the choice of TNF versus non-TNF therapy in terms of clinical efficacy.

The study was supported by the Corrona Research Foundation. Dr. Baker disclosed receiving support from a Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research and Development Merit Award and a Rehabilitation Research and Development Merit Award, and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, CorEvitas, and Burns-White. Two coauthors reported financial ties to CorEvitas.

There does not appear to be superiority of any type of biologic medication for patients with rheumatoid arthritis across different body mass index (BMI) groupings, with obesity and underweight both reducing the effects of the treatments after 6 months of use, according to findings from registry data on nearly 6,000 individuals.

Although interest in the precision use of biologics for RA is on the rise, few patient characteristics have been identified to inform therapeutic decisions, Joshua F. Baker, MD, of the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote.

Previous studies on the effect of obesity on RA treatments have been inconclusive, and a comparison of RA treatments across BMI categories would provide more definitive guidance, they said.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the researchers used the CorEvitas U.S. observational registry (formerly known as Corrona) to identify adults who initiated second- or third-line treatment for RA with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (n = 2,891) or non-TNFi biologics (n = 3,010) between 2001 and April 30, 2021.

The study population included adults diagnosed with RA; those with low disease activity or without a 6-month follow-up visit were excluded. BMI was categorized as underweight (less than 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5-25 kg/m2), overweight (25-30 kg/m2), obese (30-35 kg/m2), and severely obese (35 kg/m2 or higher). The three measures of response were the achievement of low disease activity (LDA), a change at least as large as the minimum clinically important difference (MCID), and the absolute change on the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) from baseline.

A total of 2,712 patients were obese or severely obese at the time of treatment initiation.

Overall, patients with severe obesity had significantly lower odds of achieving either LDA or a change at least as large as the MCID, as well as less improvement in CDAI score, compared with other BMI categories. However, in adjusted models, the differences in these outcomes for patients with severe obesity were no longer statistically significant, whereas underweight was associated with lower odds of achieving LDA (odds ratio, 0.32; P = .005) or a change at least as large as the MCID (OR, 0.40; P = .005). The adjusted model also showed lesser improvement on CDAI in underweight patients, compared with patients of normal weight (P = .006).

Stratification by TNFi and non-TNFi therapies showed no differences in clinical response rates across BMI categories.

The study represents the first evidence of a similar reduction in therapeutic response with both TNFi and non-TNFi in severely obese patients, with estimates for non-TNFi biologics that fit within the 95% confidence interval for TNFi biologics, the researchers wrote. “Our current study suggests that a lack of response among obese patients is not specific to TNFi therapies, suggesting that this phenomenon is not biologically specific to the TNF pathway.”

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the focus on patients who were not naive to biologic treatments and by the relatively small number of underweight patients (n = 57), the researchers noted. Other limitations include unaddressed mediators of the relationship between obesity and disease activity and lack of data on off-label dosing strategies.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, control for a range of confounding factors, and the direct comparison of RA therapies.

The researchers concluded that BMI should not influence the choice of TNF versus non-TNF therapy in terms of clinical efficacy.

The study was supported by the Corrona Research Foundation. Dr. Baker disclosed receiving support from a Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research and Development Merit Award and a Rehabilitation Research and Development Merit Award, and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, CorEvitas, and Burns-White. Two coauthors reported financial ties to CorEvitas.

There does not appear to be superiority of any type of biologic medication for patients with rheumatoid arthritis across different body mass index (BMI) groupings, with obesity and underweight both reducing the effects of the treatments after 6 months of use, according to findings from registry data on nearly 6,000 individuals.

Although interest in the precision use of biologics for RA is on the rise, few patient characteristics have been identified to inform therapeutic decisions, Joshua F. Baker, MD, of the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues wrote.

Previous studies on the effect of obesity on RA treatments have been inconclusive, and a comparison of RA treatments across BMI categories would provide more definitive guidance, they said.

In a study published in Arthritis Care & Research, the researchers used the CorEvitas U.S. observational registry (formerly known as Corrona) to identify adults who initiated second- or third-line treatment for RA with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (n = 2,891) or non-TNFi biologics (n = 3,010) between 2001 and April 30, 2021.

The study population included adults diagnosed with RA; those with low disease activity or without a 6-month follow-up visit were excluded. BMI was categorized as underweight (less than 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5-25 kg/m2), overweight (25-30 kg/m2), obese (30-35 kg/m2), and severely obese (35 kg/m2 or higher). The three measures of response were the achievement of low disease activity (LDA), a change at least as large as the minimum clinically important difference (MCID), and the absolute change on the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) from baseline.

A total of 2,712 patients were obese or severely obese at the time of treatment initiation.

Overall, patients with severe obesity had significantly lower odds of achieving either LDA or a change at least as large as the MCID, as well as less improvement in CDAI score, compared with other BMI categories. However, in adjusted models, the differences in these outcomes for patients with severe obesity were no longer statistically significant, whereas underweight was associated with lower odds of achieving LDA (odds ratio, 0.32; P = .005) or a change at least as large as the MCID (OR, 0.40; P = .005). The adjusted model also showed lesser improvement on CDAI in underweight patients, compared with patients of normal weight (P = .006).

Stratification by TNFi and non-TNFi therapies showed no differences in clinical response rates across BMI categories.

The study represents the first evidence of a similar reduction in therapeutic response with both TNFi and non-TNFi in severely obese patients, with estimates for non-TNFi biologics that fit within the 95% confidence interval for TNFi biologics, the researchers wrote. “Our current study suggests that a lack of response among obese patients is not specific to TNFi therapies, suggesting that this phenomenon is not biologically specific to the TNF pathway.”

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the focus on patients who were not naive to biologic treatments and by the relatively small number of underweight patients (n = 57), the researchers noted. Other limitations include unaddressed mediators of the relationship between obesity and disease activity and lack of data on off-label dosing strategies.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, control for a range of confounding factors, and the direct comparison of RA therapies.

The researchers concluded that BMI should not influence the choice of TNF versus non-TNF therapy in terms of clinical efficacy.

The study was supported by the Corrona Research Foundation. Dr. Baker disclosed receiving support from a Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research and Development Merit Award and a Rehabilitation Research and Development Merit Award, and consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, CorEvitas, and Burns-White. Two coauthors reported financial ties to CorEvitas.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

‘My boss is my son’s age’: Age differences in medical practices

Morton J, MD, a 68-year-old cardiologist based in the Midwest, saw things become dramatically worse when his nine-physician practice was taken over by a large health system.

“Everything changed. My partners and I lost a lot of autonomy. We had a say – but not the final say-so in who we hired as medical assistants or receptionists. We had to change how long we spent with patients and justify procedures or tests – not just to the insurance companies, which is an old story, but to our new employer,” said Dr. J, who asked to remain anonymous.

Worst of all, “I had to report to a kid – a doctor in his 30s, someone young enough to be my son, someone with a fraction of the clinical training and experience I had but who now got to tell me what to do and how to run my practice.”

The “final straw” for Dr. J came when the practice had to change to a new electronic health record (EHR) system. “Learning this new system was like pulling teeth,” he said. His youthful supervisor was “obviously impatient and irritated – his whole attitude and demeanor reflected a sense that he was saddled with a dinosaur.”

After much anguishing and soul-searching, Dr. J decided to retire. “I was already close to retirement age, and I thought it would be nice to spend more time with my grandchildren. Feeling so disrespected was simply the catalyst that brought the decision to a head a couple of years sooner than I had planned.”

Getting through a delicate discussion

This unfortunate situation could have been avoided had the younger supervisor shown more sensitivity, says otolaryngologist Mark Wallace, DO.

Dr. Wallace is speaking from personal experience. Early in his career, he was a younger physician who was forced to discuss a practice management issue with an older physician.

Dr. Wallace was a member of a committee that was responsible for “maximizing the efficiency of good care, while still being aware of cost issues.” When the committee “wanted one of the physicians in the group to change their behavior to improve cost savings, it was my job to discuss that with them.”

Dr. Wallace, who today is a locum tenens physician and a medical practice consultant to Physicians Thrive – an advisory group that helps physicians with financial and practice management problems – recalls feeling uncomfortable about broaching the subject to his supervisee. In this case, the older physician was prescribing name brand medications, and the committee that appointed Dr. Wallace wanted him to encourage the physician to prescribe a generic medication first and reserve brand prescriptions only for cases in which the generic was ineffective.

He acknowledges that he thought the generic was equivalent to the branded product in safety and efficacy.

“I always felt this to be a delicate discussion, whatever the age of the physician, because I didn’t like the idea of telling a doctor that they have to change how they practice so as to save money. I would never want anyone to feel they’re providing a lower level of care.”

The fact that this was an older physician – in his 60s – compounded his hesitancy. “Older physicians have a lot more experience than what I had in my 30s,” Dr. Wallace said. “I could talk to them about studies and outcomes and things like that, but a large part of medicine is the experience you gain over time.

“I presented it simply as a cost issue raised by the committee and asked him to consider experimenting with changing his prescribing behavior, while emphasizing that ultimately, it was his decision,” says Dr. Wallace.

The supervisee understood the concern and agreed to the experiment. He ended up prescribing the generic more frequently, although perhaps not as frequently as the committee would have liked.

, says Ted Epperly, MD, a family physician in Boise, Idaho, and president and CEO of Family Medicine Residency of Idaho.

Dr. Wallace said that older physicians, on coming out of training, felt more respected, were better paid, and didn’t have to continually adjust to new regulations and new complicated insurance requirements. Today’s young physicians coming out of training may not find the practice of medicine as enjoyable as their older counterparts did, but they are accustomed to increasingly complex rules and regulations, so it’s less of an adjustment. But many may not feel they want to work 80 hours per week, as their older counterparts did.

Challenges of technology

Technology is one of the most central areas where intergenerational differences play out, says Tracy Clarke, chief human resources officer at Kitsap Mental Health Services, a large nonprofit organization in Bremerton, Wash., that employs roughly 500 individuals. “The younger physicians in our practice are really prepared, already engaged in technology, and used to using technology for documentation, and it is already integrated into the way they do business in general and practice,” she said.

Dr. Epperly noted that Gen X-ers are typically comfortable with digital technology, although not quite as much as the following generation, the millennials, who have grown up with smartphones and computers quite literally at their fingertips from earliest childhood.

Dr. Epperly, now 67, described the experience of having his organization convert to a new EHR system. “Although the younger physicians were not my supervisors, the dynamic that occurred when we were switching to the new system is typical of what might happen in a more formal reporting structure of older ‘supervisee’ and younger supervisor,” he said. In fact, his experience was similar to that of Dr. J.

“Some of the millennials were so quick to learn the new system that they forgot to check in with the older ones about how they were doing, or they were frustrated with our slow pace of learning the new technology,” said Dr. Epperly. “In fact, I was struggling to master it, and so were many others of my generation, and I felt very dumb, slow, and vulnerable, even though I usually regard myself as a pretty bright guy.”

Dr. Epperly encourages younger physicians not to think, “He’s asked me five times how to do this – what’s his problem?” This impatience can be intuited by the older physician, who may take it personally and feel devalued and disrespected.

Joy Engblade, an internal medicine physician and CMO of Northern Inyo Hospital, Bishop, Calif., said that when her institution was transitioning to a new EHR system this past May, she was worried that the older physicians would have the most difficulty.

Ironically, that turned out not to be the case. In fact, the younger physicians struggled more because the older physicians recognized their limitations and “were willing to do whatever we asked them to do. They watched the tutorials about how to use the new EHR. They went to every class that was offered and did all the practice sessions.” By contrast, many of the younger ones thought, “I know how to work an EHR, I’ve been doing it for years, so how hard could it be?” By the time they needed to actually use it, the instructional resources and tutorials were no longer available.

Dr. Epperly’s experience is different. He noted that some older physicians may be embarrassed to acknowledge that they are technologically challenged and may say, “I got it, I understand,” when they are still struggling to master the new technology.

Ms. Clarke notes that the leadership in her organization is younger than many of the physicians who report to them. “For the leadership, the biggest challenge is that many older physicians are set in their ways, and they haven’t really seen a reason to change their practice or ways of doing things.” For example, some still prefer paper charting or making voice recordings of patient visits for other people to transcribe.

Ms. Clarke has some advice for younger leaders: “Really explore what the pain points are of these older physicians. Beyond their saying, ‘because I’ve always done it this way,’ what really is the advantage of, for example, paper charting when using the EHR is more efficient?”

Daniel DeBehnke, MD, is an emergency medicine physician and vice president and chief physician executive for Premier Inc., where he helps hospitals improve quality, safety, and financial performance. Before joining Premier, he was both a practicing physician and CEO of a health system consisting of more than 1,500 physicians.

“Having been on both sides of the spectrum as manager/leader within a physician group, some of whom are senior to me and some of whom are junior, I can tell you that I have never had any issues related to the age gap.” In fact, it is less about age per se and more about “the expertise that you, as a manager, bring to the table in understanding the nuances of the medical practice and for the individual being ‘managed.’ It is about trusting the expertise of the manager.”

Before and after hourly caps

Dr. Engblade regards “generational” issues to be less about age and birth year and more about the cap on hours worked during residency.

Dr. Engblade, who is 45 years old, said she did her internship year with no hourly restrictions. Such restrictions only went into effect during her second year of residency. “This created a paradigm shift in how much people wanted to work and created a consciousness of work-life balance that hadn’t been part of the conversation before,” she said.

When she interviews an older physician, a typical response is, “Of course I’ll be available any time,” whereas younger physicians, who went through residency after hourly restrictions had been established, are more likely to ask how many hours they will be on and how many they’ll be off.

Matt Lambert, MD, an independent emergency medicine physician and CMO of Curation Health, Washington, agreed, noting that differences in the cap on hours during training “can create a bit of an undertow, a tension between younger managers who are better adjusted in terms of work-life balance and older physicians being managed, who have a different work ethic and also might regard their managers as being less trained because they put in fewer hours during training.”

It is also important to be cognizant of differences in style and priorities that each generation brings to the table. Jaciel Keltgen, PhD, assistant professor of business administration, Augustana University, Sioux Falls, S.D., has heard older physicians say, “We did this the hard way, we sacrificed for our organization, and we expect the same values of younger physicians.” The younger ones tend to say, “We need to use all the tools at our disposal, and medicine doesn’t have to be practiced the way it’s always been.”

Dr. Keltgen, whose PhD is in political science and who has studied public administration, said that younger physicians may also question the mores and protocols that older physicians take for granted. For example, when her physician son was beginning his career, he was told by his senior supervisors that although he was “performing beautifully as a physician, he needed to shave more frequently, wear his white coat more often, and introduce himself as ‘Doctor’ rather than by his first name. Although he did wear his white coat more often, he didn’t change how he introduced himself to patients.”

Flexibility and mutual understanding of each generation’s needs, the type, structure, and amount of training they underwent, and the prevailing values will smooth supervisory interactions and optimize outcomes, experts agree.

Every generation’s No. 1 concern

For her dissertation, Dr. Keltgen used a large dataset of physicians and sought to draw a predictive model by generation and gender as to what physicians were seeking in order to be satisfied in their careers. One “overwhelming finding” of her research into generational differences in physicians is that “every single generation and gender is there to promote the health of their patients, and providing excellent care is their No. 1 concern. That is the common focus and the foundation that everyone can build on.”

Dr. J agreed. “Had I felt like a valued collaborator, I might have made a different decision.” He has begun to consider reentering clinical practice, perhaps as locum tenens or on a part-time basis. “I don’t want to feel that I’ve been driven out of a field that I love. I will see if I can find some type of context where my experience will be valued and learn to bring myself up to speed with technology if necessary. I believe I still have much to offer patients, and I would like to find a context to do so.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Morton J, MD, a 68-year-old cardiologist based in the Midwest, saw things become dramatically worse when his nine-physician practice was taken over by a large health system.

“Everything changed. My partners and I lost a lot of autonomy. We had a say – but not the final say-so in who we hired as medical assistants or receptionists. We had to change how long we spent with patients and justify procedures or tests – not just to the insurance companies, which is an old story, but to our new employer,” said Dr. J, who asked to remain anonymous.

Worst of all, “I had to report to a kid – a doctor in his 30s, someone young enough to be my son, someone with a fraction of the clinical training and experience I had but who now got to tell me what to do and how to run my practice.”

The “final straw” for Dr. J came when the practice had to change to a new electronic health record (EHR) system. “Learning this new system was like pulling teeth,” he said. His youthful supervisor was “obviously impatient and irritated – his whole attitude and demeanor reflected a sense that he was saddled with a dinosaur.”

After much anguishing and soul-searching, Dr. J decided to retire. “I was already close to retirement age, and I thought it would be nice to spend more time with my grandchildren. Feeling so disrespected was simply the catalyst that brought the decision to a head a couple of years sooner than I had planned.”

Getting through a delicate discussion

This unfortunate situation could have been avoided had the younger supervisor shown more sensitivity, says otolaryngologist Mark Wallace, DO.

Dr. Wallace is speaking from personal experience. Early in his career, he was a younger physician who was forced to discuss a practice management issue with an older physician.

Dr. Wallace was a member of a committee that was responsible for “maximizing the efficiency of good care, while still being aware of cost issues.” When the committee “wanted one of the physicians in the group to change their behavior to improve cost savings, it was my job to discuss that with them.”

Dr. Wallace, who today is a locum tenens physician and a medical practice consultant to Physicians Thrive – an advisory group that helps physicians with financial and practice management problems – recalls feeling uncomfortable about broaching the subject to his supervisee. In this case, the older physician was prescribing name brand medications, and the committee that appointed Dr. Wallace wanted him to encourage the physician to prescribe a generic medication first and reserve brand prescriptions only for cases in which the generic was ineffective.

He acknowledges that he thought the generic was equivalent to the branded product in safety and efficacy.

“I always felt this to be a delicate discussion, whatever the age of the physician, because I didn’t like the idea of telling a doctor that they have to change how they practice so as to save money. I would never want anyone to feel they’re providing a lower level of care.”

The fact that this was an older physician – in his 60s – compounded his hesitancy. “Older physicians have a lot more experience than what I had in my 30s,” Dr. Wallace said. “I could talk to them about studies and outcomes and things like that, but a large part of medicine is the experience you gain over time.

“I presented it simply as a cost issue raised by the committee and asked him to consider experimenting with changing his prescribing behavior, while emphasizing that ultimately, it was his decision,” says Dr. Wallace.

The supervisee understood the concern and agreed to the experiment. He ended up prescribing the generic more frequently, although perhaps not as frequently as the committee would have liked.

, says Ted Epperly, MD, a family physician in Boise, Idaho, and president and CEO of Family Medicine Residency of Idaho.

Dr. Wallace said that older physicians, on coming out of training, felt more respected, were better paid, and didn’t have to continually adjust to new regulations and new complicated insurance requirements. Today’s young physicians coming out of training may not find the practice of medicine as enjoyable as their older counterparts did, but they are accustomed to increasingly complex rules and regulations, so it’s less of an adjustment. But many may not feel they want to work 80 hours per week, as their older counterparts did.

Challenges of technology

Technology is one of the most central areas where intergenerational differences play out, says Tracy Clarke, chief human resources officer at Kitsap Mental Health Services, a large nonprofit organization in Bremerton, Wash., that employs roughly 500 individuals. “The younger physicians in our practice are really prepared, already engaged in technology, and used to using technology for documentation, and it is already integrated into the way they do business in general and practice,” she said.

Dr. Epperly noted that Gen X-ers are typically comfortable with digital technology, although not quite as much as the following generation, the millennials, who have grown up with smartphones and computers quite literally at their fingertips from earliest childhood.

Dr. Epperly, now 67, described the experience of having his organization convert to a new EHR system. “Although the younger physicians were not my supervisors, the dynamic that occurred when we were switching to the new system is typical of what might happen in a more formal reporting structure of older ‘supervisee’ and younger supervisor,” he said. In fact, his experience was similar to that of Dr. J.

“Some of the millennials were so quick to learn the new system that they forgot to check in with the older ones about how they were doing, or they were frustrated with our slow pace of learning the new technology,” said Dr. Epperly. “In fact, I was struggling to master it, and so were many others of my generation, and I felt very dumb, slow, and vulnerable, even though I usually regard myself as a pretty bright guy.”

Dr. Epperly encourages younger physicians not to think, “He’s asked me five times how to do this – what’s his problem?” This impatience can be intuited by the older physician, who may take it personally and feel devalued and disrespected.

Joy Engblade, an internal medicine physician and CMO of Northern Inyo Hospital, Bishop, Calif., said that when her institution was transitioning to a new EHR system this past May, she was worried that the older physicians would have the most difficulty.

Ironically, that turned out not to be the case. In fact, the younger physicians struggled more because the older physicians recognized their limitations and “were willing to do whatever we asked them to do. They watched the tutorials about how to use the new EHR. They went to every class that was offered and did all the practice sessions.” By contrast, many of the younger ones thought, “I know how to work an EHR, I’ve been doing it for years, so how hard could it be?” By the time they needed to actually use it, the instructional resources and tutorials were no longer available.

Dr. Epperly’s experience is different. He noted that some older physicians may be embarrassed to acknowledge that they are technologically challenged and may say, “I got it, I understand,” when they are still struggling to master the new technology.

Ms. Clarke notes that the leadership in her organization is younger than many of the physicians who report to them. “For the leadership, the biggest challenge is that many older physicians are set in their ways, and they haven’t really seen a reason to change their practice or ways of doing things.” For example, some still prefer paper charting or making voice recordings of patient visits for other people to transcribe.

Ms. Clarke has some advice for younger leaders: “Really explore what the pain points are of these older physicians. Beyond their saying, ‘because I’ve always done it this way,’ what really is the advantage of, for example, paper charting when using the EHR is more efficient?”

Daniel DeBehnke, MD, is an emergency medicine physician and vice president and chief physician executive for Premier Inc., where he helps hospitals improve quality, safety, and financial performance. Before joining Premier, he was both a practicing physician and CEO of a health system consisting of more than 1,500 physicians.

“Having been on both sides of the spectrum as manager/leader within a physician group, some of whom are senior to me and some of whom are junior, I can tell you that I have never had any issues related to the age gap.” In fact, it is less about age per se and more about “the expertise that you, as a manager, bring to the table in understanding the nuances of the medical practice and for the individual being ‘managed.’ It is about trusting the expertise of the manager.”

Before and after hourly caps

Dr. Engblade regards “generational” issues to be less about age and birth year and more about the cap on hours worked during residency.

Dr. Engblade, who is 45 years old, said she did her internship year with no hourly restrictions. Such restrictions only went into effect during her second year of residency. “This created a paradigm shift in how much people wanted to work and created a consciousness of work-life balance that hadn’t been part of the conversation before,” she said.

When she interviews an older physician, a typical response is, “Of course I’ll be available any time,” whereas younger physicians, who went through residency after hourly restrictions had been established, are more likely to ask how many hours they will be on and how many they’ll be off.

Matt Lambert, MD, an independent emergency medicine physician and CMO of Curation Health, Washington, agreed, noting that differences in the cap on hours during training “can create a bit of an undertow, a tension between younger managers who are better adjusted in terms of work-life balance and older physicians being managed, who have a different work ethic and also might regard their managers as being less trained because they put in fewer hours during training.”

It is also important to be cognizant of differences in style and priorities that each generation brings to the table. Jaciel Keltgen, PhD, assistant professor of business administration, Augustana University, Sioux Falls, S.D., has heard older physicians say, “We did this the hard way, we sacrificed for our organization, and we expect the same values of younger physicians.” The younger ones tend to say, “We need to use all the tools at our disposal, and medicine doesn’t have to be practiced the way it’s always been.”

Dr. Keltgen, whose PhD is in political science and who has studied public administration, said that younger physicians may also question the mores and protocols that older physicians take for granted. For example, when her physician son was beginning his career, he was told by his senior supervisors that although he was “performing beautifully as a physician, he needed to shave more frequently, wear his white coat more often, and introduce himself as ‘Doctor’ rather than by his first name. Although he did wear his white coat more often, he didn’t change how he introduced himself to patients.”

Flexibility and mutual understanding of each generation’s needs, the type, structure, and amount of training they underwent, and the prevailing values will smooth supervisory interactions and optimize outcomes, experts agree.

Every generation’s No. 1 concern

For her dissertation, Dr. Keltgen used a large dataset of physicians and sought to draw a predictive model by generation and gender as to what physicians were seeking in order to be satisfied in their careers. One “overwhelming finding” of her research into generational differences in physicians is that “every single generation and gender is there to promote the health of their patients, and providing excellent care is their No. 1 concern. That is the common focus and the foundation that everyone can build on.”

Dr. J agreed. “Had I felt like a valued collaborator, I might have made a different decision.” He has begun to consider reentering clinical practice, perhaps as locum tenens or on a part-time basis. “I don’t want to feel that I’ve been driven out of a field that I love. I will see if I can find some type of context where my experience will be valued and learn to bring myself up to speed with technology if necessary. I believe I still have much to offer patients, and I would like to find a context to do so.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Morton J, MD, a 68-year-old cardiologist based in the Midwest, saw things become dramatically worse when his nine-physician practice was taken over by a large health system.

“Everything changed. My partners and I lost a lot of autonomy. We had a say – but not the final say-so in who we hired as medical assistants or receptionists. We had to change how long we spent with patients and justify procedures or tests – not just to the insurance companies, which is an old story, but to our new employer,” said Dr. J, who asked to remain anonymous.

Worst of all, “I had to report to a kid – a doctor in his 30s, someone young enough to be my son, someone with a fraction of the clinical training and experience I had but who now got to tell me what to do and how to run my practice.”

The “final straw” for Dr. J came when the practice had to change to a new electronic health record (EHR) system. “Learning this new system was like pulling teeth,” he said. His youthful supervisor was “obviously impatient and irritated – his whole attitude and demeanor reflected a sense that he was saddled with a dinosaur.”

After much anguishing and soul-searching, Dr. J decided to retire. “I was already close to retirement age, and I thought it would be nice to spend more time with my grandchildren. Feeling so disrespected was simply the catalyst that brought the decision to a head a couple of years sooner than I had planned.”

Getting through a delicate discussion

This unfortunate situation could have been avoided had the younger supervisor shown more sensitivity, says otolaryngologist Mark Wallace, DO.

Dr. Wallace is speaking from personal experience. Early in his career, he was a younger physician who was forced to discuss a practice management issue with an older physician.

Dr. Wallace was a member of a committee that was responsible for “maximizing the efficiency of good care, while still being aware of cost issues.” When the committee “wanted one of the physicians in the group to change their behavior to improve cost savings, it was my job to discuss that with them.”

Dr. Wallace, who today is a locum tenens physician and a medical practice consultant to Physicians Thrive – an advisory group that helps physicians with financial and practice management problems – recalls feeling uncomfortable about broaching the subject to his supervisee. In this case, the older physician was prescribing name brand medications, and the committee that appointed Dr. Wallace wanted him to encourage the physician to prescribe a generic medication first and reserve brand prescriptions only for cases in which the generic was ineffective.

He acknowledges that he thought the generic was equivalent to the branded product in safety and efficacy.

“I always felt this to be a delicate discussion, whatever the age of the physician, because I didn’t like the idea of telling a doctor that they have to change how they practice so as to save money. I would never want anyone to feel they’re providing a lower level of care.”

The fact that this was an older physician – in his 60s – compounded his hesitancy. “Older physicians have a lot more experience than what I had in my 30s,” Dr. Wallace said. “I could talk to them about studies and outcomes and things like that, but a large part of medicine is the experience you gain over time.

“I presented it simply as a cost issue raised by the committee and asked him to consider experimenting with changing his prescribing behavior, while emphasizing that ultimately, it was his decision,” says Dr. Wallace.

The supervisee understood the concern and agreed to the experiment. He ended up prescribing the generic more frequently, although perhaps not as frequently as the committee would have liked.

, says Ted Epperly, MD, a family physician in Boise, Idaho, and president and CEO of Family Medicine Residency of Idaho.

Dr. Wallace said that older physicians, on coming out of training, felt more respected, were better paid, and didn’t have to continually adjust to new regulations and new complicated insurance requirements. Today’s young physicians coming out of training may not find the practice of medicine as enjoyable as their older counterparts did, but they are accustomed to increasingly complex rules and regulations, so it’s less of an adjustment. But many may not feel they want to work 80 hours per week, as their older counterparts did.

Challenges of technology

Technology is one of the most central areas where intergenerational differences play out, says Tracy Clarke, chief human resources officer at Kitsap Mental Health Services, a large nonprofit organization in Bremerton, Wash., that employs roughly 500 individuals. “The younger physicians in our practice are really prepared, already engaged in technology, and used to using technology for documentation, and it is already integrated into the way they do business in general and practice,” she said.

Dr. Epperly noted that Gen X-ers are typically comfortable with digital technology, although not quite as much as the following generation, the millennials, who have grown up with smartphones and computers quite literally at their fingertips from earliest childhood.

Dr. Epperly, now 67, described the experience of having his organization convert to a new EHR system. “Although the younger physicians were not my supervisors, the dynamic that occurred when we were switching to the new system is typical of what might happen in a more formal reporting structure of older ‘supervisee’ and younger supervisor,” he said. In fact, his experience was similar to that of Dr. J.

“Some of the millennials were so quick to learn the new system that they forgot to check in with the older ones about how they were doing, or they were frustrated with our slow pace of learning the new technology,” said Dr. Epperly. “In fact, I was struggling to master it, and so were many others of my generation, and I felt very dumb, slow, and vulnerable, even though I usually regard myself as a pretty bright guy.”

Dr. Epperly encourages younger physicians not to think, “He’s asked me five times how to do this – what’s his problem?” This impatience can be intuited by the older physician, who may take it personally and feel devalued and disrespected.

Joy Engblade, an internal medicine physician and CMO of Northern Inyo Hospital, Bishop, Calif., said that when her institution was transitioning to a new EHR system this past May, she was worried that the older physicians would have the most difficulty.

Ironically, that turned out not to be the case. In fact, the younger physicians struggled more because the older physicians recognized their limitations and “were willing to do whatever we asked them to do. They watched the tutorials about how to use the new EHR. They went to every class that was offered and did all the practice sessions.” By contrast, many of the younger ones thought, “I know how to work an EHR, I’ve been doing it for years, so how hard could it be?” By the time they needed to actually use it, the instructional resources and tutorials were no longer available.

Dr. Epperly’s experience is different. He noted that some older physicians may be embarrassed to acknowledge that they are technologically challenged and may say, “I got it, I understand,” when they are still struggling to master the new technology.

Ms. Clarke notes that the leadership in her organization is younger than many of the physicians who report to them. “For the leadership, the biggest challenge is that many older physicians are set in their ways, and they haven’t really seen a reason to change their practice or ways of doing things.” For example, some still prefer paper charting or making voice recordings of patient visits for other people to transcribe.

Ms. Clarke has some advice for younger leaders: “Really explore what the pain points are of these older physicians. Beyond their saying, ‘because I’ve always done it this way,’ what really is the advantage of, for example, paper charting when using the EHR is more efficient?”

Daniel DeBehnke, MD, is an emergency medicine physician and vice president and chief physician executive for Premier Inc., where he helps hospitals improve quality, safety, and financial performance. Before joining Premier, he was both a practicing physician and CEO of a health system consisting of more than 1,500 physicians.

“Having been on both sides of the spectrum as manager/leader within a physician group, some of whom are senior to me and some of whom are junior, I can tell you that I have never had any issues related to the age gap.” In fact, it is less about age per se and more about “the expertise that you, as a manager, bring to the table in understanding the nuances of the medical practice and for the individual being ‘managed.’ It is about trusting the expertise of the manager.”

Before and after hourly caps

Dr. Engblade regards “generational” issues to be less about age and birth year and more about the cap on hours worked during residency.

Dr. Engblade, who is 45 years old, said she did her internship year with no hourly restrictions. Such restrictions only went into effect during her second year of residency. “This created a paradigm shift in how much people wanted to work and created a consciousness of work-life balance that hadn’t been part of the conversation before,” she said.

When she interviews an older physician, a typical response is, “Of course I’ll be available any time,” whereas younger physicians, who went through residency after hourly restrictions had been established, are more likely to ask how many hours they will be on and how many they’ll be off.

Matt Lambert, MD, an independent emergency medicine physician and CMO of Curation Health, Washington, agreed, noting that differences in the cap on hours during training “can create a bit of an undertow, a tension between younger managers who are better adjusted in terms of work-life balance and older physicians being managed, who have a different work ethic and also might regard their managers as being less trained because they put in fewer hours during training.”

It is also important to be cognizant of differences in style and priorities that each generation brings to the table. Jaciel Keltgen, PhD, assistant professor of business administration, Augustana University, Sioux Falls, S.D., has heard older physicians say, “We did this the hard way, we sacrificed for our organization, and we expect the same values of younger physicians.” The younger ones tend to say, “We need to use all the tools at our disposal, and medicine doesn’t have to be practiced the way it’s always been.”

Dr. Keltgen, whose PhD is in political science and who has studied public administration, said that younger physicians may also question the mores and protocols that older physicians take for granted. For example, when her physician son was beginning his career, he was told by his senior supervisors that although he was “performing beautifully as a physician, he needed to shave more frequently, wear his white coat more often, and introduce himself as ‘Doctor’ rather than by his first name. Although he did wear his white coat more often, he didn’t change how he introduced himself to patients.”

Flexibility and mutual understanding of each generation’s needs, the type, structure, and amount of training they underwent, and the prevailing values will smooth supervisory interactions and optimize outcomes, experts agree.

Every generation’s No. 1 concern

For her dissertation, Dr. Keltgen used a large dataset of physicians and sought to draw a predictive model by generation and gender as to what physicians were seeking in order to be satisfied in their careers. One “overwhelming finding” of her research into generational differences in physicians is that “every single generation and gender is there to promote the health of their patients, and providing excellent care is their No. 1 concern. That is the common focus and the foundation that everyone can build on.”

Dr. J agreed. “Had I felt like a valued collaborator, I might have made a different decision.” He has begun to consider reentering clinical practice, perhaps as locum tenens or on a part-time basis. “I don’t want to feel that I’ve been driven out of a field that I love. I will see if I can find some type of context where my experience will be valued and learn to bring myself up to speed with technology if necessary. I believe I still have much to offer patients, and I would like to find a context to do so.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Schizophrenia risk lower for people with access to green space

The investigators, led by Martin Rotenberg, MD, of Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the University of Toronto, found individuals living in areas with the lowest levels of green space were 24% more likely to develop schizophrenia.

This study contributes to a growing body of evidence showing the importance of exposure to green space to mental health.

“These findings contribute to a growing evidence base that environmental factors may play a role in the etiology of schizophrenia,” the researchers write.

The study was published online Feb. 4 in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry.

Underlying mechanism unknown

For the study, researchers used a retrospective population-based cohort of 649,020 individuals between ages 14 and 40 years from different neighborhoods in Toronto.

Green space was calculated using geospatial data of all public parks and green spaces in the city; data were drawn from the Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response Tool.

Over a 10-year period, 4,841 participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Those who lived in neighborhoods with the least amount of green space were significantly more likely to develop schizophrenia than those who lived in areas with the most green space, even after adjusting for age, sex, and neighborhood-level marginalization (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-1.45).

Overall, schizophrenia risk was also elevated in men vs. women (adjusted IRR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.50-1.68). Those living in areas with moderate amounts of green space did not have an increased schizophrenia risk.

“We found that residing in an area with the lowest amount of green space was associated with an increased risk of developing schizophrenia, independent of other sociodemographic and socioenvironmental factors,” the researchers note. “The underlying mechanism at play is unknown and requires further study.”

One possibility, they added, is that exposure to green space may reduce the risk of air pollution, which other studies have suggested may be associated with increased schizophrenia risk.

The new study builds on a 2018 report from Denmark that showed a 52% increased risk of psychotic disorders in adulthood among people who spent their childhood in neighborhoods with little green space.

Important, longitudinal data

Commenting on the findings, John Torous, MD, director of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said the study provides important longitudinal data.

“The 10-year duration of the study and large sample size make the results very compelling and help confirm what has been thought about green space and risk of schizophrenia,” Dr. Torous said.

“Often, we think of green space at a very macro level,” he added. “This study is important because it shows us that green space matters on a block-by-block level just as much.”

The study was unfunded. The authors and Dr. Torous have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The investigators, led by Martin Rotenberg, MD, of Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the University of Toronto, found individuals living in areas with the lowest levels of green space were 24% more likely to develop schizophrenia.

This study contributes to a growing body of evidence showing the importance of exposure to green space to mental health.

“These findings contribute to a growing evidence base that environmental factors may play a role in the etiology of schizophrenia,” the researchers write.

The study was published online Feb. 4 in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry.

Underlying mechanism unknown

For the study, researchers used a retrospective population-based cohort of 649,020 individuals between ages 14 and 40 years from different neighborhoods in Toronto.

Green space was calculated using geospatial data of all public parks and green spaces in the city; data were drawn from the Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response Tool.

Over a 10-year period, 4,841 participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Those who lived in neighborhoods with the least amount of green space were significantly more likely to develop schizophrenia than those who lived in areas with the most green space, even after adjusting for age, sex, and neighborhood-level marginalization (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-1.45).

Overall, schizophrenia risk was also elevated in men vs. women (adjusted IRR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.50-1.68). Those living in areas with moderate amounts of green space did not have an increased schizophrenia risk.

“We found that residing in an area with the lowest amount of green space was associated with an increased risk of developing schizophrenia, independent of other sociodemographic and socioenvironmental factors,” the researchers note. “The underlying mechanism at play is unknown and requires further study.”

One possibility, they added, is that exposure to green space may reduce the risk of air pollution, which other studies have suggested may be associated with increased schizophrenia risk.

The new study builds on a 2018 report from Denmark that showed a 52% increased risk of psychotic disorders in adulthood among people who spent their childhood in neighborhoods with little green space.

Important, longitudinal data

Commenting on the findings, John Torous, MD, director of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said the study provides important longitudinal data.

“The 10-year duration of the study and large sample size make the results very compelling and help confirm what has been thought about green space and risk of schizophrenia,” Dr. Torous said.

“Often, we think of green space at a very macro level,” he added. “This study is important because it shows us that green space matters on a block-by-block level just as much.”

The study was unfunded. The authors and Dr. Torous have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The investigators, led by Martin Rotenberg, MD, of Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the University of Toronto, found individuals living in areas with the lowest levels of green space were 24% more likely to develop schizophrenia.

This study contributes to a growing body of evidence showing the importance of exposure to green space to mental health.

“These findings contribute to a growing evidence base that environmental factors may play a role in the etiology of schizophrenia,” the researchers write.

The study was published online Feb. 4 in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry.

Underlying mechanism unknown

For the study, researchers used a retrospective population-based cohort of 649,020 individuals between ages 14 and 40 years from different neighborhoods in Toronto.

Green space was calculated using geospatial data of all public parks and green spaces in the city; data were drawn from the Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response Tool.

Over a 10-year period, 4,841 participants were diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Those who lived in neighborhoods with the least amount of green space were significantly more likely to develop schizophrenia than those who lived in areas with the most green space, even after adjusting for age, sex, and neighborhood-level marginalization (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-1.45).

Overall, schizophrenia risk was also elevated in men vs. women (adjusted IRR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.50-1.68). Those living in areas with moderate amounts of green space did not have an increased schizophrenia risk.

“We found that residing in an area with the lowest amount of green space was associated with an increased risk of developing schizophrenia, independent of other sociodemographic and socioenvironmental factors,” the researchers note. “The underlying mechanism at play is unknown and requires further study.”

One possibility, they added, is that exposure to green space may reduce the risk of air pollution, which other studies have suggested may be associated with increased schizophrenia risk.

The new study builds on a 2018 report from Denmark that showed a 52% increased risk of psychotic disorders in adulthood among people who spent their childhood in neighborhoods with little green space.

Important, longitudinal data

Commenting on the findings, John Torous, MD, director of digital psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said the study provides important longitudinal data.

“The 10-year duration of the study and large sample size make the results very compelling and help confirm what has been thought about green space and risk of schizophrenia,” Dr. Torous said.

“Often, we think of green space at a very macro level,” he added. “This study is important because it shows us that green space matters on a block-by-block level just as much.”

The study was unfunded. The authors and Dr. Torous have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CANADIAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY

Few new cancer drugs replace current standards of care

, a new analysis shows.

Of more than 200 agents evaluated, most (42%) received approval as second-, third-, or later-line therapies.

“While there is justified enthusiasm for the high volume of new cancer drug approvals in oncology and malignant hematology, these approvals must be evaluated in the context of their use,” the authors note in a report published online March 15 in JAMA Network Open. Later-line drugs may, for instance, “benefit patients with few alternatives but also add to cost of care and further delay palliative and comfort services” compared to first-line therapies, which may alter “the treatment paradigm for a certain indication.”

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approves several new cancer drugs each month, but it’s not clear how many transform the treatment landscape.

To investigate, David Benjamin, MD, with the Division of Hematology and Oncology, University of California, Irvine, and colleagues evaluated all 207 cancer drugs approved in the U.S. between May 1, 2016 and May 31, 2021.

The researchers found that only 28 drugs (14%) displaced the prior first-line standard of care for an indication.

Examples of these cancer drugs include alectinib for anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement–positive metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), osimertinib for epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 deletion or exon 21 L858R substitution NSCLC, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab for unresectable or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma, and cabozantinib for advanced kidney cancer.

A total of 32 drugs (15%) were approved as first-line alternatives or new drugs. These drugs were approved for use in the first-line setting but did not necessarily replace the standard of care at the time of approval or were first-of-their-class therapies.

Examples of these drug approvals include apalutamide for nonmetastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer, tepotinib for metastatic MET exon 14-skipping NSCLC, and avapritinib for unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor with platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha exon 18 variant, including D842V variant.

A total of 61 drugs (29%) were approved as add-on therapies for use in combination with a previously approved therapy or in the adjuvant or maintenance settings. These drugs “can only increase the cost of care,” the study team says.

Most new approvals (n = 86) were for use in second-, third- or later-line settings, often for patients for whom other treatment options had been exhausted.

The authors highlight disparities among approvals based on tumor type. Lung-related tumors received the most approvals (n = 37), followed by genitourinary tumors (n = 28), leukemia (n = 25), lymphoma (n = 22), breast cancer (n = 19), and gastrointestinal cancers (n = 14).

The authors note that cancer drugs considered new standards of care or approved as first-line setting alternatives could “provide market competition and work to lower cancer drug prices.”

The study was funded by a grant from Arnold Ventures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new analysis shows.

Of more than 200 agents evaluated, most (42%) received approval as second-, third-, or later-line therapies.

“While there is justified enthusiasm for the high volume of new cancer drug approvals in oncology and malignant hematology, these approvals must be evaluated in the context of their use,” the authors note in a report published online March 15 in JAMA Network Open. Later-line drugs may, for instance, “benefit patients with few alternatives but also add to cost of care and further delay palliative and comfort services” compared to first-line therapies, which may alter “the treatment paradigm for a certain indication.”

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approves several new cancer drugs each month, but it’s not clear how many transform the treatment landscape.

To investigate, David Benjamin, MD, with the Division of Hematology and Oncology, University of California, Irvine, and colleagues evaluated all 207 cancer drugs approved in the U.S. between May 1, 2016 and May 31, 2021.

The researchers found that only 28 drugs (14%) displaced the prior first-line standard of care for an indication.

Examples of these cancer drugs include alectinib for anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement–positive metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), osimertinib for epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 deletion or exon 21 L858R substitution NSCLC, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab for unresectable or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma, and cabozantinib for advanced kidney cancer.

A total of 32 drugs (15%) were approved as first-line alternatives or new drugs. These drugs were approved for use in the first-line setting but did not necessarily replace the standard of care at the time of approval or were first-of-their-class therapies.

Examples of these drug approvals include apalutamide for nonmetastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer, tepotinib for metastatic MET exon 14-skipping NSCLC, and avapritinib for unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor with platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha exon 18 variant, including D842V variant.

A total of 61 drugs (29%) were approved as add-on therapies for use in combination with a previously approved therapy or in the adjuvant or maintenance settings. These drugs “can only increase the cost of care,” the study team says.

Most new approvals (n = 86) were for use in second-, third- or later-line settings, often for patients for whom other treatment options had been exhausted.

The authors highlight disparities among approvals based on tumor type. Lung-related tumors received the most approvals (n = 37), followed by genitourinary tumors (n = 28), leukemia (n = 25), lymphoma (n = 22), breast cancer (n = 19), and gastrointestinal cancers (n = 14).

The authors note that cancer drugs considered new standards of care or approved as first-line setting alternatives could “provide market competition and work to lower cancer drug prices.”

The study was funded by a grant from Arnold Ventures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new analysis shows.

Of more than 200 agents evaluated, most (42%) received approval as second-, third-, or later-line therapies.

“While there is justified enthusiasm for the high volume of new cancer drug approvals in oncology and malignant hematology, these approvals must be evaluated in the context of their use,” the authors note in a report published online March 15 in JAMA Network Open. Later-line drugs may, for instance, “benefit patients with few alternatives but also add to cost of care and further delay palliative and comfort services” compared to first-line therapies, which may alter “the treatment paradigm for a certain indication.”

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approves several new cancer drugs each month, but it’s not clear how many transform the treatment landscape.

To investigate, David Benjamin, MD, with the Division of Hematology and Oncology, University of California, Irvine, and colleagues evaluated all 207 cancer drugs approved in the U.S. between May 1, 2016 and May 31, 2021.

The researchers found that only 28 drugs (14%) displaced the prior first-line standard of care for an indication.

Examples of these cancer drugs include alectinib for anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement–positive metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), osimertinib for epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 deletion or exon 21 L858R substitution NSCLC, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab for unresectable or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma, and cabozantinib for advanced kidney cancer.

A total of 32 drugs (15%) were approved as first-line alternatives or new drugs. These drugs were approved for use in the first-line setting but did not necessarily replace the standard of care at the time of approval or were first-of-their-class therapies.

Examples of these drug approvals include apalutamide for nonmetastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer, tepotinib for metastatic MET exon 14-skipping NSCLC, and avapritinib for unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor with platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha exon 18 variant, including D842V variant.

A total of 61 drugs (29%) were approved as add-on therapies for use in combination with a previously approved therapy or in the adjuvant or maintenance settings. These drugs “can only increase the cost of care,” the study team says.

Most new approvals (n = 86) were for use in second-, third- or later-line settings, often for patients for whom other treatment options had been exhausted.

The authors highlight disparities among approvals based on tumor type. Lung-related tumors received the most approvals (n = 37), followed by genitourinary tumors (n = 28), leukemia (n = 25), lymphoma (n = 22), breast cancer (n = 19), and gastrointestinal cancers (n = 14).

The authors note that cancer drugs considered new standards of care or approved as first-line setting alternatives could “provide market competition and work to lower cancer drug prices.”

The study was funded by a grant from Arnold Ventures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

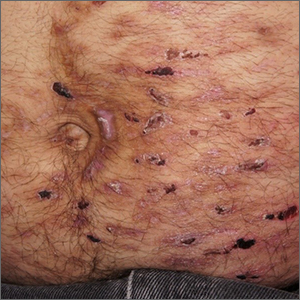

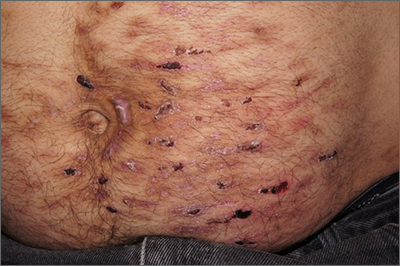

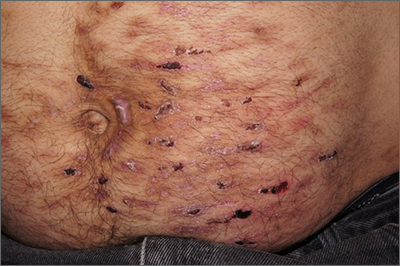

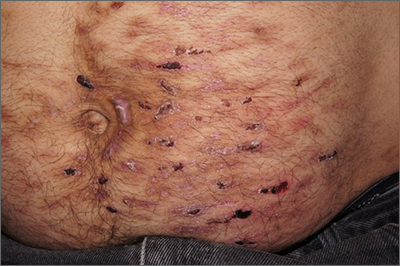

Abdominal rash

Despite his insistence that he was not scratching his abdomen, the lack of primary lesions and the appearance of horizontally oriented excoriations over the abdomen in multiple stages of healing were consistent with neurotic excoriations.

Neurotic excoriation is frequently associated with psychiatric disease, especially obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression.1 Stimulant-use, either by prescription or illicit, can lead to increased self-grooming behaviors, motor tics, and scratching. High doses of stimulants can trigger paranoia and tactile hallucinations.

In this case, the preponderance of skin lesions occurring on the left side of the patient’s abdomen fit with a right-handed individual, which the patient was. On his anterior lower legs, there were linear excoriations oriented vertically. Close observation of the patient during history taking revealed unconscious skin-picking behavior, and dead skin and debris could be noted under his fingernails. Two punch biopsies of active lesions were consistent with excoriations and excluded inflammatory causes of itching. (Careful evaluation for scabies, eczema, urticaria, and contact dermatitis was also performed.)

In this case, the patient’s psychiatrist reduced his dosage of lisdexamfetamine to a starting dose of 30 mg daily, which led to decreased skin scratching behavior. While the patient continued to have limited insight into the nature of his skin changes, progress was measured by a reduction in the number of active lesions.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

Despite his insistence that he was not scratching his abdomen, the lack of primary lesions and the appearance of horizontally oriented excoriations over the abdomen in multiple stages of healing were consistent with neurotic excoriations.

Neurotic excoriation is frequently associated with psychiatric disease, especially obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression.1 Stimulant-use, either by prescription or illicit, can lead to increased self-grooming behaviors, motor tics, and scratching. High doses of stimulants can trigger paranoia and tactile hallucinations.

In this case, the preponderance of skin lesions occurring on the left side of the patient’s abdomen fit with a right-handed individual, which the patient was. On his anterior lower legs, there were linear excoriations oriented vertically. Close observation of the patient during history taking revealed unconscious skin-picking behavior, and dead skin and debris could be noted under his fingernails. Two punch biopsies of active lesions were consistent with excoriations and excluded inflammatory causes of itching. (Careful evaluation for scabies, eczema, urticaria, and contact dermatitis was also performed.)

In this case, the patient’s psychiatrist reduced his dosage of lisdexamfetamine to a starting dose of 30 mg daily, which led to decreased skin scratching behavior. While the patient continued to have limited insight into the nature of his skin changes, progress was measured by a reduction in the number of active lesions.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Despite his insistence that he was not scratching his abdomen, the lack of primary lesions and the appearance of horizontally oriented excoriations over the abdomen in multiple stages of healing were consistent with neurotic excoriations.

Neurotic excoriation is frequently associated with psychiatric disease, especially obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression.1 Stimulant-use, either by prescription or illicit, can lead to increased self-grooming behaviors, motor tics, and scratching. High doses of stimulants can trigger paranoia and tactile hallucinations.

In this case, the preponderance of skin lesions occurring on the left side of the patient’s abdomen fit with a right-handed individual, which the patient was. On his anterior lower legs, there were linear excoriations oriented vertically. Close observation of the patient during history taking revealed unconscious skin-picking behavior, and dead skin and debris could be noted under his fingernails. Two punch biopsies of active lesions were consistent with excoriations and excluded inflammatory causes of itching. (Careful evaluation for scabies, eczema, urticaria, and contact dermatitis was also performed.)

In this case, the patient’s psychiatrist reduced his dosage of lisdexamfetamine to a starting dose of 30 mg daily, which led to decreased skin scratching behavior. While the patient continued to have limited insight into the nature of his skin changes, progress was measured by a reduction in the number of active lesions.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

1. Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

Boring is good. Boring is right. Boring is … interesting

Can you keep it down? I’m trying to be boring

He chides his friends for not looking both ways before crossing the road. He is never questioned by the police because they fall asleep listening to him talk. He has won the office’s coveted perfect attendance award 10 years running. Look out, Dos Equis guy, you’ve got some new competition. That’s right, it’s the most boring man in the world.

For this boring study (sorry, study on boredom) conducted by English researchers and published in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, people were surveyed on various jobs and hobbies, ranking them by how exciting or boring they are, as well as how competent someone with those jobs/hobbies would be, their willingness to avoid someone with those jobs/hobbies, and how much they’d need to be paid to spend time with someone who had an undesirable job/hobby.

According to the British public, the most boring person in the world is a religious data analyst who likes to sleep and lives in a small town. In fact, spending time with this person is almost a full-time job on its own: To make it worth their while, survey subjects wanted 35 pounds a day. The boring person also was viewed as less competent, as is anyone with a boring job.

Now, there probably aren’t a lot of religious data analysts out there, but don’t worry, there are plenty of other boring jobs – accounting, tax/insurance, cleaning, and banking rounded out the top five (apparently people don’t like finances) – and hobbies – watching TV, observing animals, and mathematics filled out the top five. In case you’re curious, performing artists, scientists, journalists, health professionals, and teachers were viewed as having exciting jobs; exciting hobbies included gaming, reading, domestic tasks (really?), gardening, and writing.

Lead researcher Wijnand Van Tilburg, PhD, made an excellent point about people with boring jobs: They “have power in society – perhaps we should try not to upset them and stereotype them as boring!”

We think they should lean into it and make The Most Boring Man in the World ads: “When I drive a car off the lot, its value increases because I used the correct lending association. Batman trusts me with his Batmobile insurance. I can make those Cuban cigars tax exempt. Stay financially solvent, my friends.”

Fungi, but make it fashion

Fashion is an expensive and costly industry to sustain. Cotton production takes a toll on the environment, leather production comes with environmental and ethical/moral conundrums, and thanks to fast fashion, about 85% of textiles are being thrown away in the United States.

Researchers at the University of Borås in Sweden, however, have found a newish solution to create leather, cotton, and other textiles. And as with so many of the finer things, it starts with unsold bread from the grocery store.

Akram Zamani, PhD, and her team take that bread and turn it into breadcrumbs, then combine it with water and Rhizopus delemar, a fungus typically found in decaying food. After a couple of days of feasting on the bread, the fungus produces natural fibers made of chitin and chitosan that accumulate in the cell walls. After proteins, lipids, and other byproducts are removed, the team is left with a jelly-like substance made of those fibrous cell walls that can be spun into a fabric.

The researchers started small with very thin nonpliable sheets, but with a little layering by using tree tannins for softness and alkali for strength, their fungal leather is more like real leather than competing fungal leathers. Not to mention its being able to be produced in a fraction of the time.

This new fungal leather is fast to produce, it’s biodegradable, and it uses only natural ingredients to treat the materials. It’s the ultimate environmental fashion statement.

Who’s afraid of cancer? Not C. elegans

And now, we bring you part 2 of our ongoing series: Creatures that can diagnose cancer. Last week, we discovered that ants are well on their way to replacing dogs in our medical labs and in our hearts. This week, we present the even-more-lovable nematode.