User login

The Official Newspaper of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery

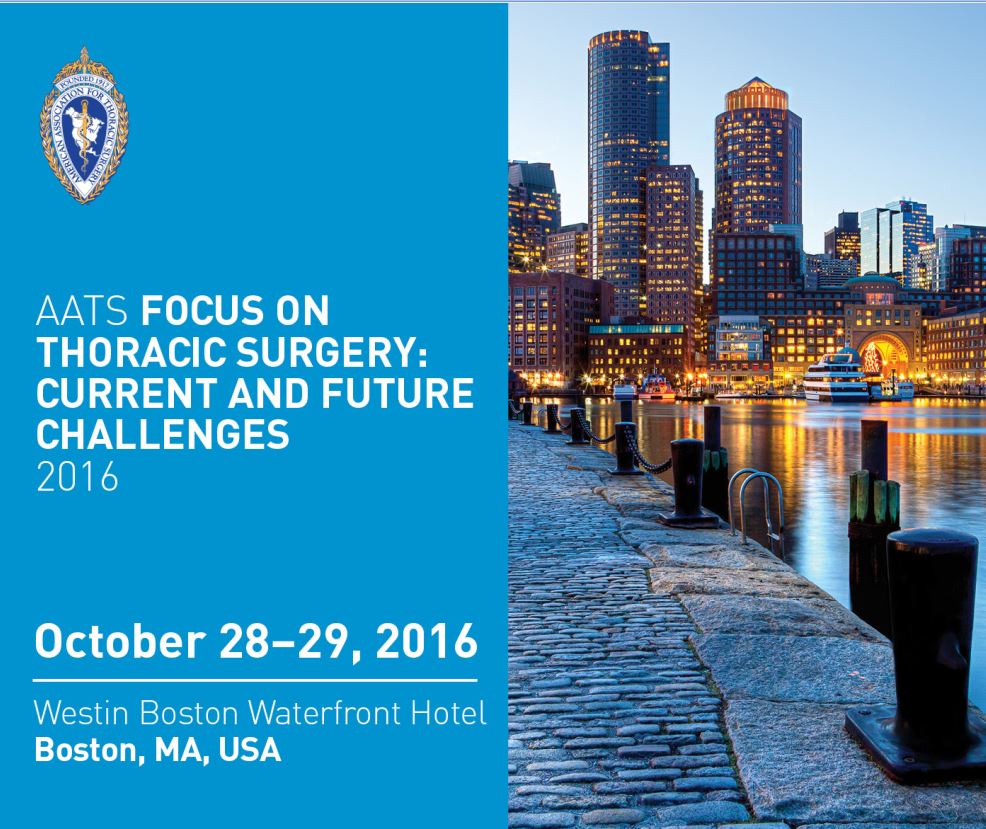

AATS Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Current and Future Challenges

The preliminary program and registration information is now available for AATS Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Current and Future Challenges.

October 28-29, 2016

Westin Boston Waterfront Hotel, Boston, MA

Program Directors

G. Alexander Patterson

David J. Sugarbaker

Program Committee

Thomas A. D’Amico

Shaf Keshavjee

James D. Luketich

Bryan F. Meyers

Scott J. Swanson

Overview

Currently practicing surgeons will be able to improve patient outcomes by enriching their knowledge and technical skills in the definition, diagnosis and resolution of thoracic surgical difficulties and post-operative complications. Expert faculty will provide state-of-the-art solutions to challenges in the field. Attendees will augment their overall understanding of thoracic diseases, upgrade their competency and ability to formulate new clinical strategies, and enhance their diagnosis and surgical treatment of thoracic diseases.

More information: http://aats.org/focus/

The preliminary program and registration information is now available for AATS Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Current and Future Challenges.

October 28-29, 2016

Westin Boston Waterfront Hotel, Boston, MA

Program Directors

G. Alexander Patterson

David J. Sugarbaker

Program Committee

Thomas A. D’Amico

Shaf Keshavjee

James D. Luketich

Bryan F. Meyers

Scott J. Swanson

Overview

Currently practicing surgeons will be able to improve patient outcomes by enriching their knowledge and technical skills in the definition, diagnosis and resolution of thoracic surgical difficulties and post-operative complications. Expert faculty will provide state-of-the-art solutions to challenges in the field. Attendees will augment their overall understanding of thoracic diseases, upgrade their competency and ability to formulate new clinical strategies, and enhance their diagnosis and surgical treatment of thoracic diseases.

More information: http://aats.org/focus/

The preliminary program and registration information is now available for AATS Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Current and Future Challenges.

October 28-29, 2016

Westin Boston Waterfront Hotel, Boston, MA

Program Directors

G. Alexander Patterson

David J. Sugarbaker

Program Committee

Thomas A. D’Amico

Shaf Keshavjee

James D. Luketich

Bryan F. Meyers

Scott J. Swanson

Overview

Currently practicing surgeons will be able to improve patient outcomes by enriching their knowledge and technical skills in the definition, diagnosis and resolution of thoracic surgical difficulties and post-operative complications. Expert faculty will provide state-of-the-art solutions to challenges in the field. Attendees will augment their overall understanding of thoracic diseases, upgrade their competency and ability to formulate new clinical strategies, and enhance their diagnosis and surgical treatment of thoracic diseases.

More information: http://aats.org/focus/

AATS Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Current and Future Challenges

The preliminary program and registration information is now available for AATS Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Current and Future Challenges.

October 28-29, 2016

Westin Boston Waterfront Hotel

Boston, MA

Program Directors

G. Alexander Patterson

David J. Sugarbaker

Program Committee

Thomas A. D’Amico

Shaf Keshavjee

James D. Luketich

Bryan F. Meyers

Scott J. Swanson

Overview

Currently practicing surgeons will be able to improve patient outcomes by enriching their knowledge and technical skills in the definition, diagnosis and resolution of thoracic surgical difficulties and post-operative complications. Expert faculty will provide state-of-the-art solutions to challenges in the field. Attendees will augment their overall understanding of thoracic diseases, upgrade their competency and ability to formulate new clinical strategies, and enhance their diagnosis and surgical treatment of thoracic diseases.

The preliminary program and registration information is now available for AATS Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Current and Future Challenges.

October 28-29, 2016

Westin Boston Waterfront Hotel

Boston, MA

Program Directors

G. Alexander Patterson

David J. Sugarbaker

Program Committee

Thomas A. D’Amico

Shaf Keshavjee

James D. Luketich

Bryan F. Meyers

Scott J. Swanson

Overview

Currently practicing surgeons will be able to improve patient outcomes by enriching their knowledge and technical skills in the definition, diagnosis and resolution of thoracic surgical difficulties and post-operative complications. Expert faculty will provide state-of-the-art solutions to challenges in the field. Attendees will augment their overall understanding of thoracic diseases, upgrade their competency and ability to formulate new clinical strategies, and enhance their diagnosis and surgical treatment of thoracic diseases.

The preliminary program and registration information is now available for AATS Focus on Thoracic Surgery: Current and Future Challenges.

October 28-29, 2016

Westin Boston Waterfront Hotel

Boston, MA

Program Directors

G. Alexander Patterson

David J. Sugarbaker

Program Committee

Thomas A. D’Amico

Shaf Keshavjee

James D. Luketich

Bryan F. Meyers

Scott J. Swanson

Overview

Currently practicing surgeons will be able to improve patient outcomes by enriching their knowledge and technical skills in the definition, diagnosis and resolution of thoracic surgical difficulties and post-operative complications. Expert faculty will provide state-of-the-art solutions to challenges in the field. Attendees will augment their overall understanding of thoracic diseases, upgrade their competency and ability to formulate new clinical strategies, and enhance their diagnosis and surgical treatment of thoracic diseases.

Elusive evidence pervades ESC’s 2016 heart failure guidelines

FLORENCE, ITALY – The 2016 revision of the European Society of Cardiology’s guidelines for diagnosing and treating acute and chronic heart failure highlights the extent to which thinking in the field has changed during the past 4 years, since the prior edition in 2012.

The new European guidelines, unveiled by the ESC’s Heart Failure Association during the group’s annual meeting, also underscore the great dependence that many new approaches have on expert opinion rather than what’s become the keystone of guidelines writing, evidence-based medicine. Frequent reliance on consensus decisions rather than indisputable proof from controlled trials defines what some U.S. specialists see as a divide as wide as the Atlantic between the European and U.S. approaches to guideline writing.

“The guidelines from the ESC are articulated very well; they made their recommendations very clear. But a lot is consensus driven, without new data,” said Dr. Mariell L. Jessup, who serves as both vice chair of the panel currently revising the U.S. heart failure guidelines – expected out later in 2016 – and was also the sole American representative on the panel that produced the ESC guidelines. “The ESC guidelines make clear all the things that need to happen to patients. I hope it will result in better patient care. We are clearly not doing a good job in heart failure. We not only don’t have evidence-based treatments, but people often don’t do a good job [caring for heart failure patients] and they die in the hospital all the time.”

Dr. Javed Butler, another member of the U.S. guidelines panel and professor and chief of cardiology at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University, called the U.S. and European divide a “philosophical perspective of evidence-based medicine.

“U.S. physicians should read the ESC guidelines and make up their own minds. The ESC guidelines are excellent and give you perspective. But U.S. regulatory and payment issues will be driven by U.S. guidelines,” Dr. Butler said in an interview.

But despite their limitations and the limited weight that the ESC guidelines carry for U.S. practice, they have many redeeming features, noted Dr. Mandeep R. Mehra, medical director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. The 2016 ESC guidelines “are extraordinarily clear, very practical, and very concise. They are very usable, and provide a fantastic algorithm for managing patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction [HFrEF],” he said while discussing the guidelines during the meeting.

U.S. and Europe largely agree on sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine

Clearly the greatest area of U.S. and European agreement was in the adoption by both guidelines groups of sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) and ivabradine (Corlanor) as important new components of the basic drug formula for treating patients with HFrEF. In fact, the U.S. guideline writers saw these two additions as so important and timely that they issued a “focused update” in May to the existing, 2013 U.S. heart failure guidelines, and timed release of this update to occur on May 20, 2016, a day before release of the ESC guidelines. But as Dr. Butler noted, this was more of a temporal harmonization than a substantive one, because even here, in a very evidence-based change, the U.S. guidelines for using sacubitril/valsartan differed subtly but importantly from the ESC version.

The U.S. focused update says that treatment of patients with stage C (symptomatic heart failure with structural heart disease) HFrEF should receive treatment with sacubitril/valsartan (also know as an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, or ARNI), an ACE inhibitor, or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), as well as evidence-based treatment with a beta-blocker and with a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA). A subsequent recommendation in the U.S. focused update said that HFrEF patients with chronic symptoms and New York Heart Association class II or III disease should switch from a stable, tolerated regimen with either an ACE inhibitor or ARB to treatment with sacubitril/valsartan.

In contrast, the new European guideline for sacubitril/valsartan recommends starting patients on this combination formulation only after first demonstrating that patients tolerated treatment with an ACE inhibitor or ARB for at least 30 days and determining that patients remained symptomatic while on one of these treatments. In short, the U.S. guideline gives a green light to starting patients with newly diagnosed, symptomatic HFrEF on sacubitril/valsartan immediately, while the European guideline only sanctions sacubitril/valsartan to start after a patient has spent at least 30 days settling into a multidrug regimen featuring an ACE inhibitor or an ARB when an ACE inhibitor isn’t well tolerated.

“The European guidelines are closely related to the study population enrolled in the PARADIGM-HF trial,” the pivotal trial that showed superiority of sacubitril/valsartan to an ACE inhibitor (N Engl J Med. 2014;371:993-1004), noted Dr. Butler in an interview. “The U.S. guidelines interpreted [the PARADIGM-HF] results in the best interests of a larger patient population. The European guidelines are far more proscriptive in replicating the clinical criteria of the trial. In some patients the sequence of starting a MRA and sacubitril/valsartan matters, but in other patients it is less important.”

Dr. Frank Ruschitzka, a coauthor of the ESC guidelines, said that the reason for the more cautious ESC approach was lack of widespread familiarity with sacubitril/valsartan treatment among cardiologists.

The ESC guidelines on using sacubitril/valsartan “replicated the PARADIGM-HF trial. We have no data right now that it is justifiable to put a [treatment-naive] patient on sacubitril/valsartan to begin with. Another difference between the U.S. and ESC guidelines is when to start a MRA,” said Dr. Ruschitzka, professor and head of cardiology at the Heart Center of the University Hospital in Zurich. “It makes a lot of sense to me to start sacubitril/valsartan early. The PARADIGM trial was positive, but no one has a feel for how to use sacubitril/valsartan. Should we give it to everyone? We said replicate the trial, and gain experience using the drug. We want to bring a life-saving drug to patients, but this is the approach we took. We need more data.”

Dr. Jessup noted that a lot of uncertainty also exists among U.S. clinicians about when to start sacubitril/valsartan. “It’s not been clear which patients to put on sacubitril/valsartan. No guidelines had been out on using it” until mid-May, and “the cost of sacubitril/valsartan is daunting. I have received calls from many people who ask whom am I supposed to use sacubitril/valsartan on? It took years and years to get people to [routinely] start patients on an ACE inhibitor and a beta-blocker, and now we’re telling them to do something else. In my practice it’s a 30-minute conversation with each patient that you need to first stop your ACE inhibitor, and then they often get denied coverage by their insurer,” said Dr. Jessup, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. She expressed hope that coverage issues will diminish now that clear guidelines are out endorsing a key role for sacubitril/valsartan.

“We now all have started sacubitril/valsartan on patients” without first starting them on an ACE inhibitor, “but we all need to get a sense of what we can get away with” when using this drug, noted Dr. JoAnn Lindenfeld, professor and director of heart failure and transplant at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

At least one European cardiologist was skeptical of just how proscriptive the ESC guideline for sacubitril/valsartan will be in actual practice.

“The best treatment [for symptomatic HFrEF] is sacubitril/valsartan, a beta-blocker, and a MRA,” said Dr. John J.V. McMurray, professor of cardiology at Glasgow University and lead investigator for the PARADIGM-HF pivotal trial for sacubitril/valsartan. “The treatment sequence advocated in the guidelines – treat with an ACE inhibitor first and if patients remain symptomatic change to sacubitril/valsartan – is evidence-based medicine. As a guidelines writer and as a promoter of evidence-based medicine, this is absolutely the correct approach. But as a practicing physician I’d go straight for sacubitril/valsartan. Otherwise you’re wasting everybody’s time starting with an ACE inhibitor and then waiting a month to switch,” Dr. McMurray said in an interview.

“It’s pointless to wait. We saw results within 30 days of starting sacubitril/valsartan, so it’s a theoretical risk to wait. Very few patients will become completely asymptomatic on an ACE inhibitor. Everyone who entered PARADIGM-HF was at New York Heart Association class II or higher, and at the time of randomization only a handful of patients were in New York Heart Association class I. Very few patients get to class I. That tells you it’s pretty uncommon for a heart failure patient to become truly asymptomatic with ACE inhibitor treatment. The main problem is that you are inconveniencing everybody with more blood tests and more clinic visits by waiting to start sacubitril/valsartan, said Dr. McMurray, who was not a member of the panel that wrote the new ESC guidelines.

Even less separates the new U.S. focused update and the ESC guidelines for using ivabradine. Both agree on starting the drug on HFrEF patients who remain symptomatic and with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less despite being on guideline-directed therapy including titration to a maximum beta-blocker dosage and with a persistent heart rate of at least 70 beats/min. The goal of ivabradine treatment is to further reduce heart rate beyond what’s achieved by a maximal beta-blocker dosage.

Perhaps the biggest questions about ivabradine have been why it took so long to enter the U.S. guidelines, and why it is listed in both the U.S. and ESC guidelines as a level II recommendation. Results from the pivotal trial that supported ivabradine’s use in HFrEF patients, SHIFT, first appeared in 2010 (Lancet. 2010 Sep 11;376[9744]:875-95).

Dr. Butler chalked up the drug’s slow entry into U.S. guidelines as the result of a lack of initiative by ivabradine’s initial developer, Servier. “SHIFT did not have any U.S. sites, and Servier never sought Food and Drug Administration approval,” he noted. “Amgen acquired the U.S. rights to ivabradine in 2013,” and the drug received FDA approval in April 2015, Dr. Butler noted, in explaining the drug’s U.S. timeline. As to why its use is a level II recommendation, he noted that the evidence for efficacy came only from the SHIFT trial, questions exist whether the beta-blocker dosages were fully optimized in all patients in this trial, and the benefit was limited to a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations but not in mortality. “I think that patients with persistent heart failure symptoms [and a persistently elevated heart rate] should get ivabradine,” but these caveats limit it to a class II level recommendation, Dr. Butler said.

“There were questions about ivabradine’s benefit in reducing heart failure hospitalization but not mortality, and questions about whether it would benefit patients if their beta-blocker dosage was adequately up titrated. There were also questions about which heart failure patients to use it on,” noted Dr. Lindenfeld, a member of the panel that wrote the U.S. focused update. These concerns in part help explain the delay to integrating ivabradine into U.S. practice guidelines, she said in an interview, but added that additional data and analysis published during the past 3 or so years have clarified ivabradine’s potentially useful role in treating selected HFrEF patients.

New ESC guidelines based on expert opinion

The sections on sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine occupy a mere 2 pages among more than 55 pages of text and charts that spell out the ESC’s current vision of how physicians should diagnose and manage heart failure patients. While much of what carried over from prior editions of the guidelines is rooted in evidence, many of the new approaches advocated rely on expert opinion or new interpretations of existing data. Here are some of the notable changes and highlights of the 2016 ESC recommendations:

• Heart failure diagnosis. The new ESC guidelines streamline the diagnostic process, which now focuses on five key elements: The patient’s history, physical examination, ECG, serum level of either brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal(NT)-proBNP, and echocardiography. The guidelines specify threshold levels of BNP and NT-proBNP that can effectively rule out heart failure, a BNP level of at least 35 pg/mL or a NT-proBNP level of at least 125 pg/mL.

“The diagnostic minimum levels of BNP and NT-proBNP were designed to rule out heart failure. They both have a high negative predictive value, but at these levels their positive predictive value is low,” explained Dr. Adriaan A. Voors, cochair of the ESC’s guideline-writing panel and professor of cardiology at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands.

But while these levels might be effective for reliable rule out of heart failure, they could mean a large number of patients would qualify for an echocardiographic assessment.

“If we used the ESC’s natriuretic peptide cutoffs, there would be a clear concern about overuse of echo. It’s a cost-effectiveness issue. You wind up doing a lot of echos that will be normal. Echocardiography is very safe, but each echo costs about $400-$500,” commented Dr. Butler.

“The results from the STOP-HF and PONTIAC studies showed that BNP levels can identify people at increased risk for developing heart failure who need more intensive assessment and could also potentially benefit from more attention to heart failure prevention. I suspect the full U.S. guideline update will address this issue, but we have not yet finalized our decisions,” he added.

• Heart failure classification. The new ESC guidelines created a new heart failure category, midrange ejection fraction, that the writing panel positioned squarely between the two more classic heart failure subgroups, HFrEF and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). The definition of each of the three subgroups depends on left ventricular ejection fraction as determined by echocardiography: A LVEF of less than 40% defined HFrEF, a LVEF of 40%-49% defined heart failure with midrange ejection fraction (HFmrEF), and a LVEF of 50% or higher defined HFpEF. Diagnostic confirmation of both HFmrEF and HFpEF also requires that patients fulfill certain criteria of structural or functional heart abnormalities.

The category of HFmrEF was created “to stimulate research into how to best manage these patients,” explained Dr. Piotr Ponikowski, chair of the ESC guidelines writing panel. For the time being, it remains a category with only theoretical importance as nothing is known to suggest that management of patients with HFmrEF should in any way differ from patients with HFpEF.

• Acute heart failure. Perhaps the most revolutionary element of the new guidelines is the detailed map they provide to managing patients who present with acute decompensated heart failure and the underlying principles cited to justify this radically different approach.

“The acute heart failure section was completely rewritten,” noted Dr. Ponikowski, professor of heart diseases at the Medical University in Wroclaw, Poland. “We don’t yet have evidence-based treatments” to apply to acute heart failure patients, he admitted, “however we strongly recommend the concept that the shorter the better. Shorten the time of diagnosis and for therapeutic decisions. We have borrowed from acute coronary syndrome. Don’t keep patients in the emergency department for another couple of hours just to see if they will respond. We must be aware that we need to do our best to shorten diagnosis and treatment decisions. Time is an issue. Manage a patient’s congestion and impaired peripheral perfusion within a time frame of 1-2 hours.”

The concept that acute heart failure must be quickly managed as an emergency condition similar to acute coronary syndrome first appeared as a European practice recommendation in 2015, a consensus statement from the European Heart Failure Association and two other collaborating organizations (Eur Heart J. 2015 Aug 7;36[30]:1958-66).

“In 2015, the consensus paper talked about how to handle acute heart failure patients in the emergency department. Now, we have focused on defining the patients’ phenotype and how to categorize their treatment options. We built on the 2015 statement, but the algorithms we now have are original to 2016; they were not in the 2015 paper,” said Dr. Veli-Pekka Harjola, a member of the 2015 consensus group and 2016 guidelines panel who spearheaded writing the acute heart failure section of the new ESC guidelines.

An additional new and notable feature of this section in the 2016 guidelines is its creation of an acronym, CHAMP, designed to guide the management of patients with acute heart failure. CHAMP stands for acute Coronary syndrome, Hypertension emergency, Arrhythmia, acute Mechanical cause, and Pulmonary embolism. The CHAMP acronym’s purpose is to “focus attention on these five specific, potential causes of acute heart failure, life-threatening conditions that need immediate treatment,” explained Dr. Ponikowski.

“CHAMP emphasizes the most critical causes of acute heart failure,” added Dr. Harjola, a cardiologist at Helsinki University Central Hospital. “We created this new acronym” to help clinicians keep in mind what to look for in a patient presenting with acute heart failure.

U.S. cardiologists find things to like in what the Europeans say about managing acute heart failure, as well as aspects to question.

“It makes no sense not to aggressively treat a patient who arrives at an emergency department with acute heart failure. But there is a difference between acute MI or stroke and acute heart failure,” said Dr. Butler. “In acute MI there is the ruptured plaque and thrombus that blocks a coronary artery. In stroke there is a thrombus. These are diseases with a specific onset and treatment target. But with acute heart failure we don’t have a thrombus to treat; we don’t have a specific target. What we’ve learned from studying implanted devices [such as CardioMems] is that the congestion that causes acute heart failure can start 2-3 weeks before a patient develops acute decompensated heart failure and goes to the hospital. We have not found a specific pathophysiologic abnormality in the patient with acute heart failure that is any different from chronic heart failure. This begs the question: If a patient who presents with acute heart failure has a congestion process that’s been going on for 2 or 3 weeks what difference will another 3 hours make? Do we need to replicate the concept of an acute stroke team or acute MI response for acute heart failure?”

Dr. Butler stressed that additional data are expected soon that may help clarify this issue.

“Some large outcome trials in patients with acute heart failure are now underway, one testing serelaxin treatment, another testing ularitide treatment, that are also testing the hypothesis that rapid treatment with these drugs can produce more end-organ protection, stop damage to the heart, kidney and liver, and lead to better long-term outcomes. Until we have those data, the jury is still out” on the benefit patients gain from rapid treatment of acute heart failure. “Until then, it’s not that the data say don’t treat acute heart failure patients aggressively. But we have not yet proven it is similar to treating an acute MI or stroke,” said Dr. Butler.

“U.S. guidelines have tended to stay away from areas where there are no evidence-based data. To their credit, the Europeans will take on something like acute heart failure where we don’t have an adequate evidence base. Despite that, they provide guidelines, which is important because clinicians need guidance even when the evidence is not very good, when the guideline is based mostly on experience and expert consensus.” commented Dr. William T. Abraham, professor and director of cardiovascular medicine at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus.

“It’s absolutely appropriate to think of acute heart failure as an emergency situation. We know from high-sensitivity troponin assays that troponin levels are increased in 90% of patients who present with acute decompensated heart failure. So most acute heart failure patients are losing heart muscle cells and we should treat them like we treat acute coronary syndrome. Time matters in acute heart failure; time is heart muscle. Treatment needs to break the hemodynamic and neurohormonal storm of acute decompensated heart failure; get the patient stabilized; improve vital organ perfusion, including within the heart; and shift the myocardial oxygen supply and demand equation so myocardial necrosis stops. All of this is important, and study results suggest it’s the correct approach. I’m not sure study results prove it, but studies that have looked at the time course of treatment for acute heart failure showed that early initiation of treatment – within the first 6 hours of onset – compared with 12-24 hours of onset makes a difference in outcomes,” Dr. Abraham said in an interview.

But a major limitation to the potential efficacy of a rapidly initiated management strategy is that few interventions currently exist with proven benefits for acute heart failure patients.

For the time being, rapid intervention means using diuretics relatively quickly and, if there is an indication for treating with a vasoactive medication, using that quickly too. “The rapid approach is really more relevant to the future; it’s relevant to the design of future acute heart failure treatment trials. That is where this early treatment paradigm is important,” as it could potentially apply to new, more effective treatments of the future rather than to the marginally effective treatments now available, Dr. Abraham said.

“For a long we time haven’t pushed how quickly we should act when implementing guideline-directed treatment” for patients with acute heart failure, noted Dr. Mehra. “The CHAMP approach is interesting, and the ESC guidelines are a very interesting move in the direction” of faster action. “They speak to the period of time during which one should act. Hopefully this will help the science of acute decompensated heart failure move forward.”

But for other U.S. experts the issue again pivots on the lack of evidence.

“There is nothing new” about managing acute heart failure, said Dr. Jessup. “The ESC guideline was articulated very well; they made their recommendations very clear. But a lot is consensus driven. There are no new data. The problem with acute heart failure is that the recommendations are what we think clinicians should do. CHAMP is a nice acronym; it’s packaged better, but there are not any new data.”

Comorbidities

A dramatic contrast distinguishes the extent to which the ESC guidelines highlight comorbidities, compared with prevailing U.S. guidelines. The new ESC guidelines highlight and discuss with some detail 16 distinct comorbidities for clinicians to keep in mind when managing heart failure patients, compared with three comorbidities (atrial fibrillation, anemia, and depression) discussed with similar detail in the 2013 U.S. guidelines.

“We are targeting comorbidities to personalize medicine, by subgrouping [heart failure] patients into groups that need to receive special attention,” explained Dr. Stefan D. Anker, a coauthor on the ESC guidelines. “We care about comorbidities because they make the diagnosis of heart failure difficult. They aggravate symptoms and contribute to additional hospitalizations. They interfere with [heart failure] treatment, and because comorbidities have led to exclusions of heart failure patients from trials, we lack evidence of treatment efficacy in patients with certain comorbidities,” said Dr. Anker, a professor of innovative clinical trials at the Medical University in Göttingen, Germany.

“The comorbidity discussion in the ESC guidelines is extremely important,” commented Dr. Abraham. “It supports the need for a multidimensional approach to heart failure patients. A cardiologist may not have all the resources to manage all the comorbidities [a heart failure patient might have]. This is why having a sleep medicine specialist, a diabetes specialist, a nephrologist, etc., involved as part of a heart failure management team can be very valuable. We need to involve subspecialists in managing the comorbidities of heart failure because they clearly have an impact on patient outcome.”

But Dr. Butler had a somewhat different take on how comorbidity management fits into the broader picture of heart failure management.

“There is no doubt that heart failure worsens other comorbidities and other comorbidities worsen heart failure. The relationship is bidirectional between heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver disease, depression, sleep apnea, renal disease, lung disease, diabetes, etc. The problem is that treating a comorbidity does not necessarily translate into improved heart failure outcomes. Comorbidities are important for heart failure patients and worsen their heart failure outcomes. However, management of a comorbidity should be done primarily for the sake of improving the comorbidity. If you treat depression, for example, and it does not improve a patient’s heart failure, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have treated the depression. It just means that we don’t have good data that it will improve heart failure.”

Another limitation from a U.S. perspective is what role treatment of various comorbidities can play in benefiting heart failure patients and how compelling the evidence is for this. Dr. Butler gave as an example the problem with treating iron deficiency in heart failure patients who do not have anemia, a strategy endorsed in the ESC guidelines as a level IIa recommendation.

“The data regarding improved exercise capacity from treatment with intravenous ferric carboxymaltose is pretty convincing,” he said. But patients have benefited from this treatment only with improved function and quality of life, and not with improved survival or fewer hospitalizations.

“Is treating patients to improve their function and help them feel better enough?” Dr. Butler asked. “In other diseases it is. In gastrointestinal disease, if a drug helps patients feel better you approve the drug. We value improved functional capacity for patients with pulmonary hypertension, angina, and peripheral vascular disease. All these indications have drugs approved for improving functional capacity and quality of life. But for heart failure the bar has been set higher. There is a lot of interest in changing this” for heart failure.

“There is interest in running a study of ferric carboxymaltose for heart failure with a mortality endpoint. In the meantime, the impact on improving functional capacity is compelling, and it will be interesting to see what happens in the U.S. guidelines. Currently, in U.S. practice if a heart failure patient has iron-deficiency anemia you treat with intravenous iron replacement and the treatment gets reimbursed without a problem. But if the heart failure patient has iron deficiency without anemia then reimbursement for the cost of iron supplementation can be a problem,” Dr. Butler noted. This may change only if the experts who write the next U.S. heart failure guidelines decide to change the rules of what constitutes a useful heart failure treatment, he said.

Dr. Butler has been a consultant to Novartis and Amgen and several other companies. Dr. Jessup had no disclosures. Dr. Mehra has been a consultant to Teva, Johnson & Johnson, Boston Scientific, and St. Jude. Dr. Ruschitzka has been a consultant to Novartis, Servier, Sanofi, Cardiorentis, Heartware, and St. Jude. Dr. McMurray has received research support from Novartis and Amgen. Dr. Lindenfeld has been a consultant to Novartis, Abbott, Janssen, Relypsa, and Resmed. Dr. Voors has been a consultant to Novartis, Amgen, Servier, and several other drug companies. Dr. Ponikowski has been a consultant to Amgen, Novartis, Servier, and several other drug companies. Dr. Harjola has been a consultant to Novartis, Servier, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Resmed. Dr. Abraham has been a consultant to Amgen, Novartis, and several device companies. Dr. Anker has been a consultant to Novartis, Servier, and several other companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

FLORENCE, ITALY – The 2016 revision of the European Society of Cardiology’s guidelines for diagnosing and treating acute and chronic heart failure highlights the extent to which thinking in the field has changed during the past 4 years, since the prior edition in 2012.

The new European guidelines, unveiled by the ESC’s Heart Failure Association during the group’s annual meeting, also underscore the great dependence that many new approaches have on expert opinion rather than what’s become the keystone of guidelines writing, evidence-based medicine. Frequent reliance on consensus decisions rather than indisputable proof from controlled trials defines what some U.S. specialists see as a divide as wide as the Atlantic between the European and U.S. approaches to guideline writing.

“The guidelines from the ESC are articulated very well; they made their recommendations very clear. But a lot is consensus driven, without new data,” said Dr. Mariell L. Jessup, who serves as both vice chair of the panel currently revising the U.S. heart failure guidelines – expected out later in 2016 – and was also the sole American representative on the panel that produced the ESC guidelines. “The ESC guidelines make clear all the things that need to happen to patients. I hope it will result in better patient care. We are clearly not doing a good job in heart failure. We not only don’t have evidence-based treatments, but people often don’t do a good job [caring for heart failure patients] and they die in the hospital all the time.”

Dr. Javed Butler, another member of the U.S. guidelines panel and professor and chief of cardiology at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University, called the U.S. and European divide a “philosophical perspective of evidence-based medicine.

“U.S. physicians should read the ESC guidelines and make up their own minds. The ESC guidelines are excellent and give you perspective. But U.S. regulatory and payment issues will be driven by U.S. guidelines,” Dr. Butler said in an interview.

But despite their limitations and the limited weight that the ESC guidelines carry for U.S. practice, they have many redeeming features, noted Dr. Mandeep R. Mehra, medical director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. The 2016 ESC guidelines “are extraordinarily clear, very practical, and very concise. They are very usable, and provide a fantastic algorithm for managing patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction [HFrEF],” he said while discussing the guidelines during the meeting.

U.S. and Europe largely agree on sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine

Clearly the greatest area of U.S. and European agreement was in the adoption by both guidelines groups of sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) and ivabradine (Corlanor) as important new components of the basic drug formula for treating patients with HFrEF. In fact, the U.S. guideline writers saw these two additions as so important and timely that they issued a “focused update” in May to the existing, 2013 U.S. heart failure guidelines, and timed release of this update to occur on May 20, 2016, a day before release of the ESC guidelines. But as Dr. Butler noted, this was more of a temporal harmonization than a substantive one, because even here, in a very evidence-based change, the U.S. guidelines for using sacubitril/valsartan differed subtly but importantly from the ESC version.

The U.S. focused update says that treatment of patients with stage C (symptomatic heart failure with structural heart disease) HFrEF should receive treatment with sacubitril/valsartan (also know as an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, or ARNI), an ACE inhibitor, or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), as well as evidence-based treatment with a beta-blocker and with a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA). A subsequent recommendation in the U.S. focused update said that HFrEF patients with chronic symptoms and New York Heart Association class II or III disease should switch from a stable, tolerated regimen with either an ACE inhibitor or ARB to treatment with sacubitril/valsartan.

In contrast, the new European guideline for sacubitril/valsartan recommends starting patients on this combination formulation only after first demonstrating that patients tolerated treatment with an ACE inhibitor or ARB for at least 30 days and determining that patients remained symptomatic while on one of these treatments. In short, the U.S. guideline gives a green light to starting patients with newly diagnosed, symptomatic HFrEF on sacubitril/valsartan immediately, while the European guideline only sanctions sacubitril/valsartan to start after a patient has spent at least 30 days settling into a multidrug regimen featuring an ACE inhibitor or an ARB when an ACE inhibitor isn’t well tolerated.

“The European guidelines are closely related to the study population enrolled in the PARADIGM-HF trial,” the pivotal trial that showed superiority of sacubitril/valsartan to an ACE inhibitor (N Engl J Med. 2014;371:993-1004), noted Dr. Butler in an interview. “The U.S. guidelines interpreted [the PARADIGM-HF] results in the best interests of a larger patient population. The European guidelines are far more proscriptive in replicating the clinical criteria of the trial. In some patients the sequence of starting a MRA and sacubitril/valsartan matters, but in other patients it is less important.”

Dr. Frank Ruschitzka, a coauthor of the ESC guidelines, said that the reason for the more cautious ESC approach was lack of widespread familiarity with sacubitril/valsartan treatment among cardiologists.

The ESC guidelines on using sacubitril/valsartan “replicated the PARADIGM-HF trial. We have no data right now that it is justifiable to put a [treatment-naive] patient on sacubitril/valsartan to begin with. Another difference between the U.S. and ESC guidelines is when to start a MRA,” said Dr. Ruschitzka, professor and head of cardiology at the Heart Center of the University Hospital in Zurich. “It makes a lot of sense to me to start sacubitril/valsartan early. The PARADIGM trial was positive, but no one has a feel for how to use sacubitril/valsartan. Should we give it to everyone? We said replicate the trial, and gain experience using the drug. We want to bring a life-saving drug to patients, but this is the approach we took. We need more data.”

Dr. Jessup noted that a lot of uncertainty also exists among U.S. clinicians about when to start sacubitril/valsartan. “It’s not been clear which patients to put on sacubitril/valsartan. No guidelines had been out on using it” until mid-May, and “the cost of sacubitril/valsartan is daunting. I have received calls from many people who ask whom am I supposed to use sacubitril/valsartan on? It took years and years to get people to [routinely] start patients on an ACE inhibitor and a beta-blocker, and now we’re telling them to do something else. In my practice it’s a 30-minute conversation with each patient that you need to first stop your ACE inhibitor, and then they often get denied coverage by their insurer,” said Dr. Jessup, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. She expressed hope that coverage issues will diminish now that clear guidelines are out endorsing a key role for sacubitril/valsartan.

“We now all have started sacubitril/valsartan on patients” without first starting them on an ACE inhibitor, “but we all need to get a sense of what we can get away with” when using this drug, noted Dr. JoAnn Lindenfeld, professor and director of heart failure and transplant at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

At least one European cardiologist was skeptical of just how proscriptive the ESC guideline for sacubitril/valsartan will be in actual practice.

“The best treatment [for symptomatic HFrEF] is sacubitril/valsartan, a beta-blocker, and a MRA,” said Dr. John J.V. McMurray, professor of cardiology at Glasgow University and lead investigator for the PARADIGM-HF pivotal trial for sacubitril/valsartan. “The treatment sequence advocated in the guidelines – treat with an ACE inhibitor first and if patients remain symptomatic change to sacubitril/valsartan – is evidence-based medicine. As a guidelines writer and as a promoter of evidence-based medicine, this is absolutely the correct approach. But as a practicing physician I’d go straight for sacubitril/valsartan. Otherwise you’re wasting everybody’s time starting with an ACE inhibitor and then waiting a month to switch,” Dr. McMurray said in an interview.

“It’s pointless to wait. We saw results within 30 days of starting sacubitril/valsartan, so it’s a theoretical risk to wait. Very few patients will become completely asymptomatic on an ACE inhibitor. Everyone who entered PARADIGM-HF was at New York Heart Association class II or higher, and at the time of randomization only a handful of patients were in New York Heart Association class I. Very few patients get to class I. That tells you it’s pretty uncommon for a heart failure patient to become truly asymptomatic with ACE inhibitor treatment. The main problem is that you are inconveniencing everybody with more blood tests and more clinic visits by waiting to start sacubitril/valsartan, said Dr. McMurray, who was not a member of the panel that wrote the new ESC guidelines.

Even less separates the new U.S. focused update and the ESC guidelines for using ivabradine. Both agree on starting the drug on HFrEF patients who remain symptomatic and with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less despite being on guideline-directed therapy including titration to a maximum beta-blocker dosage and with a persistent heart rate of at least 70 beats/min. The goal of ivabradine treatment is to further reduce heart rate beyond what’s achieved by a maximal beta-blocker dosage.

Perhaps the biggest questions about ivabradine have been why it took so long to enter the U.S. guidelines, and why it is listed in both the U.S. and ESC guidelines as a level II recommendation. Results from the pivotal trial that supported ivabradine’s use in HFrEF patients, SHIFT, first appeared in 2010 (Lancet. 2010 Sep 11;376[9744]:875-95).

Dr. Butler chalked up the drug’s slow entry into U.S. guidelines as the result of a lack of initiative by ivabradine’s initial developer, Servier. “SHIFT did not have any U.S. sites, and Servier never sought Food and Drug Administration approval,” he noted. “Amgen acquired the U.S. rights to ivabradine in 2013,” and the drug received FDA approval in April 2015, Dr. Butler noted, in explaining the drug’s U.S. timeline. As to why its use is a level II recommendation, he noted that the evidence for efficacy came only from the SHIFT trial, questions exist whether the beta-blocker dosages were fully optimized in all patients in this trial, and the benefit was limited to a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations but not in mortality. “I think that patients with persistent heart failure symptoms [and a persistently elevated heart rate] should get ivabradine,” but these caveats limit it to a class II level recommendation, Dr. Butler said.

“There were questions about ivabradine’s benefit in reducing heart failure hospitalization but not mortality, and questions about whether it would benefit patients if their beta-blocker dosage was adequately up titrated. There were also questions about which heart failure patients to use it on,” noted Dr. Lindenfeld, a member of the panel that wrote the U.S. focused update. These concerns in part help explain the delay to integrating ivabradine into U.S. practice guidelines, she said in an interview, but added that additional data and analysis published during the past 3 or so years have clarified ivabradine’s potentially useful role in treating selected HFrEF patients.

New ESC guidelines based on expert opinion

The sections on sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine occupy a mere 2 pages among more than 55 pages of text and charts that spell out the ESC’s current vision of how physicians should diagnose and manage heart failure patients. While much of what carried over from prior editions of the guidelines is rooted in evidence, many of the new approaches advocated rely on expert opinion or new interpretations of existing data. Here are some of the notable changes and highlights of the 2016 ESC recommendations:

• Heart failure diagnosis. The new ESC guidelines streamline the diagnostic process, which now focuses on five key elements: The patient’s history, physical examination, ECG, serum level of either brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal(NT)-proBNP, and echocardiography. The guidelines specify threshold levels of BNP and NT-proBNP that can effectively rule out heart failure, a BNP level of at least 35 pg/mL or a NT-proBNP level of at least 125 pg/mL.

“The diagnostic minimum levels of BNP and NT-proBNP were designed to rule out heart failure. They both have a high negative predictive value, but at these levels their positive predictive value is low,” explained Dr. Adriaan A. Voors, cochair of the ESC’s guideline-writing panel and professor of cardiology at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands.

But while these levels might be effective for reliable rule out of heart failure, they could mean a large number of patients would qualify for an echocardiographic assessment.

“If we used the ESC’s natriuretic peptide cutoffs, there would be a clear concern about overuse of echo. It’s a cost-effectiveness issue. You wind up doing a lot of echos that will be normal. Echocardiography is very safe, but each echo costs about $400-$500,” commented Dr. Butler.

“The results from the STOP-HF and PONTIAC studies showed that BNP levels can identify people at increased risk for developing heart failure who need more intensive assessment and could also potentially benefit from more attention to heart failure prevention. I suspect the full U.S. guideline update will address this issue, but we have not yet finalized our decisions,” he added.

• Heart failure classification. The new ESC guidelines created a new heart failure category, midrange ejection fraction, that the writing panel positioned squarely between the two more classic heart failure subgroups, HFrEF and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). The definition of each of the three subgroups depends on left ventricular ejection fraction as determined by echocardiography: A LVEF of less than 40% defined HFrEF, a LVEF of 40%-49% defined heart failure with midrange ejection fraction (HFmrEF), and a LVEF of 50% or higher defined HFpEF. Diagnostic confirmation of both HFmrEF and HFpEF also requires that patients fulfill certain criteria of structural or functional heart abnormalities.

The category of HFmrEF was created “to stimulate research into how to best manage these patients,” explained Dr. Piotr Ponikowski, chair of the ESC guidelines writing panel. For the time being, it remains a category with only theoretical importance as nothing is known to suggest that management of patients with HFmrEF should in any way differ from patients with HFpEF.

• Acute heart failure. Perhaps the most revolutionary element of the new guidelines is the detailed map they provide to managing patients who present with acute decompensated heart failure and the underlying principles cited to justify this radically different approach.

“The acute heart failure section was completely rewritten,” noted Dr. Ponikowski, professor of heart diseases at the Medical University in Wroclaw, Poland. “We don’t yet have evidence-based treatments” to apply to acute heart failure patients, he admitted, “however we strongly recommend the concept that the shorter the better. Shorten the time of diagnosis and for therapeutic decisions. We have borrowed from acute coronary syndrome. Don’t keep patients in the emergency department for another couple of hours just to see if they will respond. We must be aware that we need to do our best to shorten diagnosis and treatment decisions. Time is an issue. Manage a patient’s congestion and impaired peripheral perfusion within a time frame of 1-2 hours.”

The concept that acute heart failure must be quickly managed as an emergency condition similar to acute coronary syndrome first appeared as a European practice recommendation in 2015, a consensus statement from the European Heart Failure Association and two other collaborating organizations (Eur Heart J. 2015 Aug 7;36[30]:1958-66).

“In 2015, the consensus paper talked about how to handle acute heart failure patients in the emergency department. Now, we have focused on defining the patients’ phenotype and how to categorize their treatment options. We built on the 2015 statement, but the algorithms we now have are original to 2016; they were not in the 2015 paper,” said Dr. Veli-Pekka Harjola, a member of the 2015 consensus group and 2016 guidelines panel who spearheaded writing the acute heart failure section of the new ESC guidelines.

An additional new and notable feature of this section in the 2016 guidelines is its creation of an acronym, CHAMP, designed to guide the management of patients with acute heart failure. CHAMP stands for acute Coronary syndrome, Hypertension emergency, Arrhythmia, acute Mechanical cause, and Pulmonary embolism. The CHAMP acronym’s purpose is to “focus attention on these five specific, potential causes of acute heart failure, life-threatening conditions that need immediate treatment,” explained Dr. Ponikowski.

“CHAMP emphasizes the most critical causes of acute heart failure,” added Dr. Harjola, a cardiologist at Helsinki University Central Hospital. “We created this new acronym” to help clinicians keep in mind what to look for in a patient presenting with acute heart failure.

U.S. cardiologists find things to like in what the Europeans say about managing acute heart failure, as well as aspects to question.

“It makes no sense not to aggressively treat a patient who arrives at an emergency department with acute heart failure. But there is a difference between acute MI or stroke and acute heart failure,” said Dr. Butler. “In acute MI there is the ruptured plaque and thrombus that blocks a coronary artery. In stroke there is a thrombus. These are diseases with a specific onset and treatment target. But with acute heart failure we don’t have a thrombus to treat; we don’t have a specific target. What we’ve learned from studying implanted devices [such as CardioMems] is that the congestion that causes acute heart failure can start 2-3 weeks before a patient develops acute decompensated heart failure and goes to the hospital. We have not found a specific pathophysiologic abnormality in the patient with acute heart failure that is any different from chronic heart failure. This begs the question: If a patient who presents with acute heart failure has a congestion process that’s been going on for 2 or 3 weeks what difference will another 3 hours make? Do we need to replicate the concept of an acute stroke team or acute MI response for acute heart failure?”

Dr. Butler stressed that additional data are expected soon that may help clarify this issue.

“Some large outcome trials in patients with acute heart failure are now underway, one testing serelaxin treatment, another testing ularitide treatment, that are also testing the hypothesis that rapid treatment with these drugs can produce more end-organ protection, stop damage to the heart, kidney and liver, and lead to better long-term outcomes. Until we have those data, the jury is still out” on the benefit patients gain from rapid treatment of acute heart failure. “Until then, it’s not that the data say don’t treat acute heart failure patients aggressively. But we have not yet proven it is similar to treating an acute MI or stroke,” said Dr. Butler.

“U.S. guidelines have tended to stay away from areas where there are no evidence-based data. To their credit, the Europeans will take on something like acute heart failure where we don’t have an adequate evidence base. Despite that, they provide guidelines, which is important because clinicians need guidance even when the evidence is not very good, when the guideline is based mostly on experience and expert consensus.” commented Dr. William T. Abraham, professor and director of cardiovascular medicine at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus.

“It’s absolutely appropriate to think of acute heart failure as an emergency situation. We know from high-sensitivity troponin assays that troponin levels are increased in 90% of patients who present with acute decompensated heart failure. So most acute heart failure patients are losing heart muscle cells and we should treat them like we treat acute coronary syndrome. Time matters in acute heart failure; time is heart muscle. Treatment needs to break the hemodynamic and neurohormonal storm of acute decompensated heart failure; get the patient stabilized; improve vital organ perfusion, including within the heart; and shift the myocardial oxygen supply and demand equation so myocardial necrosis stops. All of this is important, and study results suggest it’s the correct approach. I’m not sure study results prove it, but studies that have looked at the time course of treatment for acute heart failure showed that early initiation of treatment – within the first 6 hours of onset – compared with 12-24 hours of onset makes a difference in outcomes,” Dr. Abraham said in an interview.

But a major limitation to the potential efficacy of a rapidly initiated management strategy is that few interventions currently exist with proven benefits for acute heart failure patients.

For the time being, rapid intervention means using diuretics relatively quickly and, if there is an indication for treating with a vasoactive medication, using that quickly too. “The rapid approach is really more relevant to the future; it’s relevant to the design of future acute heart failure treatment trials. That is where this early treatment paradigm is important,” as it could potentially apply to new, more effective treatments of the future rather than to the marginally effective treatments now available, Dr. Abraham said.

“For a long we time haven’t pushed how quickly we should act when implementing guideline-directed treatment” for patients with acute heart failure, noted Dr. Mehra. “The CHAMP approach is interesting, and the ESC guidelines are a very interesting move in the direction” of faster action. “They speak to the period of time during which one should act. Hopefully this will help the science of acute decompensated heart failure move forward.”

But for other U.S. experts the issue again pivots on the lack of evidence.

“There is nothing new” about managing acute heart failure, said Dr. Jessup. “The ESC guideline was articulated very well; they made their recommendations very clear. But a lot is consensus driven. There are no new data. The problem with acute heart failure is that the recommendations are what we think clinicians should do. CHAMP is a nice acronym; it’s packaged better, but there are not any new data.”

Comorbidities

A dramatic contrast distinguishes the extent to which the ESC guidelines highlight comorbidities, compared with prevailing U.S. guidelines. The new ESC guidelines highlight and discuss with some detail 16 distinct comorbidities for clinicians to keep in mind when managing heart failure patients, compared with three comorbidities (atrial fibrillation, anemia, and depression) discussed with similar detail in the 2013 U.S. guidelines.

“We are targeting comorbidities to personalize medicine, by subgrouping [heart failure] patients into groups that need to receive special attention,” explained Dr. Stefan D. Anker, a coauthor on the ESC guidelines. “We care about comorbidities because they make the diagnosis of heart failure difficult. They aggravate symptoms and contribute to additional hospitalizations. They interfere with [heart failure] treatment, and because comorbidities have led to exclusions of heart failure patients from trials, we lack evidence of treatment efficacy in patients with certain comorbidities,” said Dr. Anker, a professor of innovative clinical trials at the Medical University in Göttingen, Germany.

“The comorbidity discussion in the ESC guidelines is extremely important,” commented Dr. Abraham. “It supports the need for a multidimensional approach to heart failure patients. A cardiologist may not have all the resources to manage all the comorbidities [a heart failure patient might have]. This is why having a sleep medicine specialist, a diabetes specialist, a nephrologist, etc., involved as part of a heart failure management team can be very valuable. We need to involve subspecialists in managing the comorbidities of heart failure because they clearly have an impact on patient outcome.”

But Dr. Butler had a somewhat different take on how comorbidity management fits into the broader picture of heart failure management.

“There is no doubt that heart failure worsens other comorbidities and other comorbidities worsen heart failure. The relationship is bidirectional between heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver disease, depression, sleep apnea, renal disease, lung disease, diabetes, etc. The problem is that treating a comorbidity does not necessarily translate into improved heart failure outcomes. Comorbidities are important for heart failure patients and worsen their heart failure outcomes. However, management of a comorbidity should be done primarily for the sake of improving the comorbidity. If you treat depression, for example, and it does not improve a patient’s heart failure, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have treated the depression. It just means that we don’t have good data that it will improve heart failure.”

Another limitation from a U.S. perspective is what role treatment of various comorbidities can play in benefiting heart failure patients and how compelling the evidence is for this. Dr. Butler gave as an example the problem with treating iron deficiency in heart failure patients who do not have anemia, a strategy endorsed in the ESC guidelines as a level IIa recommendation.

“The data regarding improved exercise capacity from treatment with intravenous ferric carboxymaltose is pretty convincing,” he said. But patients have benefited from this treatment only with improved function and quality of life, and not with improved survival or fewer hospitalizations.

“Is treating patients to improve their function and help them feel better enough?” Dr. Butler asked. “In other diseases it is. In gastrointestinal disease, if a drug helps patients feel better you approve the drug. We value improved functional capacity for patients with pulmonary hypertension, angina, and peripheral vascular disease. All these indications have drugs approved for improving functional capacity and quality of life. But for heart failure the bar has been set higher. There is a lot of interest in changing this” for heart failure.

“There is interest in running a study of ferric carboxymaltose for heart failure with a mortality endpoint. In the meantime, the impact on improving functional capacity is compelling, and it will be interesting to see what happens in the U.S. guidelines. Currently, in U.S. practice if a heart failure patient has iron-deficiency anemia you treat with intravenous iron replacement and the treatment gets reimbursed without a problem. But if the heart failure patient has iron deficiency without anemia then reimbursement for the cost of iron supplementation can be a problem,” Dr. Butler noted. This may change only if the experts who write the next U.S. heart failure guidelines decide to change the rules of what constitutes a useful heart failure treatment, he said.

Dr. Butler has been a consultant to Novartis and Amgen and several other companies. Dr. Jessup had no disclosures. Dr. Mehra has been a consultant to Teva, Johnson & Johnson, Boston Scientific, and St. Jude. Dr. Ruschitzka has been a consultant to Novartis, Servier, Sanofi, Cardiorentis, Heartware, and St. Jude. Dr. McMurray has received research support from Novartis and Amgen. Dr. Lindenfeld has been a consultant to Novartis, Abbott, Janssen, Relypsa, and Resmed. Dr. Voors has been a consultant to Novartis, Amgen, Servier, and several other drug companies. Dr. Ponikowski has been a consultant to Amgen, Novartis, Servier, and several other drug companies. Dr. Harjola has been a consultant to Novartis, Servier, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Resmed. Dr. Abraham has been a consultant to Amgen, Novartis, and several device companies. Dr. Anker has been a consultant to Novartis, Servier, and several other companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

FLORENCE, ITALY – The 2016 revision of the European Society of Cardiology’s guidelines for diagnosing and treating acute and chronic heart failure highlights the extent to which thinking in the field has changed during the past 4 years, since the prior edition in 2012.

The new European guidelines, unveiled by the ESC’s Heart Failure Association during the group’s annual meeting, also underscore the great dependence that many new approaches have on expert opinion rather than what’s become the keystone of guidelines writing, evidence-based medicine. Frequent reliance on consensus decisions rather than indisputable proof from controlled trials defines what some U.S. specialists see as a divide as wide as the Atlantic between the European and U.S. approaches to guideline writing.

“The guidelines from the ESC are articulated very well; they made their recommendations very clear. But a lot is consensus driven, without new data,” said Dr. Mariell L. Jessup, who serves as both vice chair of the panel currently revising the U.S. heart failure guidelines – expected out later in 2016 – and was also the sole American representative on the panel that produced the ESC guidelines. “The ESC guidelines make clear all the things that need to happen to patients. I hope it will result in better patient care. We are clearly not doing a good job in heart failure. We not only don’t have evidence-based treatments, but people often don’t do a good job [caring for heart failure patients] and they die in the hospital all the time.”

Dr. Javed Butler, another member of the U.S. guidelines panel and professor and chief of cardiology at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University, called the U.S. and European divide a “philosophical perspective of evidence-based medicine.

“U.S. physicians should read the ESC guidelines and make up their own minds. The ESC guidelines are excellent and give you perspective. But U.S. regulatory and payment issues will be driven by U.S. guidelines,” Dr. Butler said in an interview.

But despite their limitations and the limited weight that the ESC guidelines carry for U.S. practice, they have many redeeming features, noted Dr. Mandeep R. Mehra, medical director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. The 2016 ESC guidelines “are extraordinarily clear, very practical, and very concise. They are very usable, and provide a fantastic algorithm for managing patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction [HFrEF],” he said while discussing the guidelines during the meeting.

U.S. and Europe largely agree on sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine

Clearly the greatest area of U.S. and European agreement was in the adoption by both guidelines groups of sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) and ivabradine (Corlanor) as important new components of the basic drug formula for treating patients with HFrEF. In fact, the U.S. guideline writers saw these two additions as so important and timely that they issued a “focused update” in May to the existing, 2013 U.S. heart failure guidelines, and timed release of this update to occur on May 20, 2016, a day before release of the ESC guidelines. But as Dr. Butler noted, this was more of a temporal harmonization than a substantive one, because even here, in a very evidence-based change, the U.S. guidelines for using sacubitril/valsartan differed subtly but importantly from the ESC version.

The U.S. focused update says that treatment of patients with stage C (symptomatic heart failure with structural heart disease) HFrEF should receive treatment with sacubitril/valsartan (also know as an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, or ARNI), an ACE inhibitor, or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), as well as evidence-based treatment with a beta-blocker and with a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA). A subsequent recommendation in the U.S. focused update said that HFrEF patients with chronic symptoms and New York Heart Association class II or III disease should switch from a stable, tolerated regimen with either an ACE inhibitor or ARB to treatment with sacubitril/valsartan.

In contrast, the new European guideline for sacubitril/valsartan recommends starting patients on this combination formulation only after first demonstrating that patients tolerated treatment with an ACE inhibitor or ARB for at least 30 days and determining that patients remained symptomatic while on one of these treatments. In short, the U.S. guideline gives a green light to starting patients with newly diagnosed, symptomatic HFrEF on sacubitril/valsartan immediately, while the European guideline only sanctions sacubitril/valsartan to start after a patient has spent at least 30 days settling into a multidrug regimen featuring an ACE inhibitor or an ARB when an ACE inhibitor isn’t well tolerated.

“The European guidelines are closely related to the study population enrolled in the PARADIGM-HF trial,” the pivotal trial that showed superiority of sacubitril/valsartan to an ACE inhibitor (N Engl J Med. 2014;371:993-1004), noted Dr. Butler in an interview. “The U.S. guidelines interpreted [the PARADIGM-HF] results in the best interests of a larger patient population. The European guidelines are far more proscriptive in replicating the clinical criteria of the trial. In some patients the sequence of starting a MRA and sacubitril/valsartan matters, but in other patients it is less important.”

Dr. Frank Ruschitzka, a coauthor of the ESC guidelines, said that the reason for the more cautious ESC approach was lack of widespread familiarity with sacubitril/valsartan treatment among cardiologists.

The ESC guidelines on using sacubitril/valsartan “replicated the PARADIGM-HF trial. We have no data right now that it is justifiable to put a [treatment-naive] patient on sacubitril/valsartan to begin with. Another difference between the U.S. and ESC guidelines is when to start a MRA,” said Dr. Ruschitzka, professor and head of cardiology at the Heart Center of the University Hospital in Zurich. “It makes a lot of sense to me to start sacubitril/valsartan early. The PARADIGM trial was positive, but no one has a feel for how to use sacubitril/valsartan. Should we give it to everyone? We said replicate the trial, and gain experience using the drug. We want to bring a life-saving drug to patients, but this is the approach we took. We need more data.”

Dr. Jessup noted that a lot of uncertainty also exists among U.S. clinicians about when to start sacubitril/valsartan. “It’s not been clear which patients to put on sacubitril/valsartan. No guidelines had been out on using it” until mid-May, and “the cost of sacubitril/valsartan is daunting. I have received calls from many people who ask whom am I supposed to use sacubitril/valsartan on? It took years and years to get people to [routinely] start patients on an ACE inhibitor and a beta-blocker, and now we’re telling them to do something else. In my practice it’s a 30-minute conversation with each patient that you need to first stop your ACE inhibitor, and then they often get denied coverage by their insurer,” said Dr. Jessup, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. She expressed hope that coverage issues will diminish now that clear guidelines are out endorsing a key role for sacubitril/valsartan.

“We now all have started sacubitril/valsartan on patients” without first starting them on an ACE inhibitor, “but we all need to get a sense of what we can get away with” when using this drug, noted Dr. JoAnn Lindenfeld, professor and director of heart failure and transplant at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

At least one European cardiologist was skeptical of just how proscriptive the ESC guideline for sacubitril/valsartan will be in actual practice.

“The best treatment [for symptomatic HFrEF] is sacubitril/valsartan, a beta-blocker, and a MRA,” said Dr. John J.V. McMurray, professor of cardiology at Glasgow University and lead investigator for the PARADIGM-HF pivotal trial for sacubitril/valsartan. “The treatment sequence advocated in the guidelines – treat with an ACE inhibitor first and if patients remain symptomatic change to sacubitril/valsartan – is evidence-based medicine. As a guidelines writer and as a promoter of evidence-based medicine, this is absolutely the correct approach. But as a practicing physician I’d go straight for sacubitril/valsartan. Otherwise you’re wasting everybody’s time starting with an ACE inhibitor and then waiting a month to switch,” Dr. McMurray said in an interview.

“It’s pointless to wait. We saw results within 30 days of starting sacubitril/valsartan, so it’s a theoretical risk to wait. Very few patients will become completely asymptomatic on an ACE inhibitor. Everyone who entered PARADIGM-HF was at New York Heart Association class II or higher, and at the time of randomization only a handful of patients were in New York Heart Association class I. Very few patients get to class I. That tells you it’s pretty uncommon for a heart failure patient to become truly asymptomatic with ACE inhibitor treatment. The main problem is that you are inconveniencing everybody with more blood tests and more clinic visits by waiting to start sacubitril/valsartan, said Dr. McMurray, who was not a member of the panel that wrote the new ESC guidelines.

Even less separates the new U.S. focused update and the ESC guidelines for using ivabradine. Both agree on starting the drug on HFrEF patients who remain symptomatic and with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less despite being on guideline-directed therapy including titration to a maximum beta-blocker dosage and with a persistent heart rate of at least 70 beats/min. The goal of ivabradine treatment is to further reduce heart rate beyond what’s achieved by a maximal beta-blocker dosage.

Perhaps the biggest questions about ivabradine have been why it took so long to enter the U.S. guidelines, and why it is listed in both the U.S. and ESC guidelines as a level II recommendation. Results from the pivotal trial that supported ivabradine’s use in HFrEF patients, SHIFT, first appeared in 2010 (Lancet. 2010 Sep 11;376[9744]:875-95).

Dr. Butler chalked up the drug’s slow entry into U.S. guidelines as the result of a lack of initiative by ivabradine’s initial developer, Servier. “SHIFT did not have any U.S. sites, and Servier never sought Food and Drug Administration approval,” he noted. “Amgen acquired the U.S. rights to ivabradine in 2013,” and the drug received FDA approval in April 2015, Dr. Butler noted, in explaining the drug’s U.S. timeline. As to why its use is a level II recommendation, he noted that the evidence for efficacy came only from the SHIFT trial, questions exist whether the beta-blocker dosages were fully optimized in all patients in this trial, and the benefit was limited to a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations but not in mortality. “I think that patients with persistent heart failure symptoms [and a persistently elevated heart rate] should get ivabradine,” but these caveats limit it to a class II level recommendation, Dr. Butler said.

“There were questions about ivabradine’s benefit in reducing heart failure hospitalization but not mortality, and questions about whether it would benefit patients if their beta-blocker dosage was adequately up titrated. There were also questions about which heart failure patients to use it on,” noted Dr. Lindenfeld, a member of the panel that wrote the U.S. focused update. These concerns in part help explain the delay to integrating ivabradine into U.S. practice guidelines, she said in an interview, but added that additional data and analysis published during the past 3 or so years have clarified ivabradine’s potentially useful role in treating selected HFrEF patients.

New ESC guidelines based on expert opinion

The sections on sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine occupy a mere 2 pages among more than 55 pages of text and charts that spell out the ESC’s current vision of how physicians should diagnose and manage heart failure patients. While much of what carried over from prior editions of the guidelines is rooted in evidence, many of the new approaches advocated rely on expert opinion or new interpretations of existing data. Here are some of the notable changes and highlights of the 2016 ESC recommendations:

• Heart failure diagnosis. The new ESC guidelines streamline the diagnostic process, which now focuses on five key elements: The patient’s history, physical examination, ECG, serum level of either brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal(NT)-proBNP, and echocardiography. The guidelines specify threshold levels of BNP and NT-proBNP that can effectively rule out heart failure, a BNP level of at least 35 pg/mL or a NT-proBNP level of at least 125 pg/mL.

“The diagnostic minimum levels of BNP and NT-proBNP were designed to rule out heart failure. They both have a high negative predictive value, but at these levels their positive predictive value is low,” explained Dr. Adriaan A. Voors, cochair of the ESC’s guideline-writing panel and professor of cardiology at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands.

But while these levels might be effective for reliable rule out of heart failure, they could mean a large number of patients would qualify for an echocardiographic assessment.

“If we used the ESC’s natriuretic peptide cutoffs, there would be a clear concern about overuse of echo. It’s a cost-effectiveness issue. You wind up doing a lot of echos that will be normal. Echocardiography is very safe, but each echo costs about $400-$500,” commented Dr. Butler.

“The results from the STOP-HF and PONTIAC studies showed that BNP levels can identify people at increased risk for developing heart failure who need more intensive assessment and could also potentially benefit from more attention to heart failure prevention. I suspect the full U.S. guideline update will address this issue, but we have not yet finalized our decisions,” he added.

• Heart failure classification. The new ESC guidelines created a new heart failure category, midrange ejection fraction, that the writing panel positioned squarely between the two more classic heart failure subgroups, HFrEF and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). The definition of each of the three subgroups depends on left ventricular ejection fraction as determined by echocardiography: A LVEF of less than 40% defined HFrEF, a LVEF of 40%-49% defined heart failure with midrange ejection fraction (HFmrEF), and a LVEF of 50% or higher defined HFpEF. Diagnostic confirmation of both HFmrEF and HFpEF also requires that patients fulfill certain criteria of structural or functional heart abnormalities.

The category of HFmrEF was created “to stimulate research into how to best manage these patients,” explained Dr. Piotr Ponikowski, chair of the ESC guidelines writing panel. For the time being, it remains a category with only theoretical importance as nothing is known to suggest that management of patients with HFmrEF should in any way differ from patients with HFpEF.