User login

Neurology Reviews covers innovative and emerging news in neurology and neuroscience every month, with a focus on practical approaches to treating Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, headache, stroke, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, and other neurologic disorders.

PML

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Rituxan

The leading independent newspaper covering neurology news and commentary.

HIIT May Best Moderate Exercise for Poststroke Fitness

, according to a multicenter randomized controlled trial.

“We hoped that we would see improvements in cardiovascular fitness after HIIT and anticipated that these improvements would be greater than in the moderate-intensity group, but we were pleasantly surprised by the degree of improvement we observed,” said Ada Tang, PT, PhD, associate professor of health sciences at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. “The improvements seen in the HIIT group were twofold higher than in the other group.”

The results were published in Stroke.

Clinically Meaningful

Researchers compared the effects of 12 weeks of short-interval HIIT with those of moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) on peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak), cardiovascular risk factors, and mobility outcomes after stroke.

They randomly assigned participants to receive 3 days per week of HIIT or traditional moderate exercise sessions for 12 weeks. Participants’ mean age was 65 years, and 39% were women. They enrolled at a mean age of 1.8 years after sustaining a mild stroke.

A total of 42 participants were randomized to HIIT and 40 to MICT. There were no significant differences between the groups at baseline, and both groups exercised on adaptive recumbent steppers, which are suitable for stroke survivors with varying abilities.

The short-interval HIIT protocol involved 10 1-minute intervals of high-intensity exercise, interspersed with nine 1-minute low-intensity intervals, for a total of 19 minutes. HIIT intervals targeted 80% heart rate reserve (HRR) and progressed by 10% every 4 weeks up to 100% HRR. The low-intensity intervals targeted 30% HRR.

The traditional MICT protocol for stroke rehabilitation targeted 40% HRR for 20 minutes and progressed by 10% HRR and 5 minutes every 4 weeks, up to 60% HRR for 30 minutes.

The HIIT group’s cardiorespiratory fitness levels (VO2peak) improved twice as much as those of the MICT group: 3.5 mL of oxygen consumed in 1 minute per kg of body weight (mL/kg/min) compared with 1.8 mL/kg/min.

Of note, changes in VO2peak from baseline remained above the clinically important threshold of 1.0 mL/kg/min at 8-week follow-up in the HIIT group (1.71 mL/kg/min) but not in the MICT group (0.67 mL/kg/min).

Both groups increased their 6-minute walk test distances by 8.8 m at 12 weeks and by 18.5 m at 20 weeks. No between-group differences were found for cardiovascular risk or mobility outcomes, and no adverse events occurred in either group.

On average, the HIIT group spent 36% of total training time exercising at intensities above 80% HRR throughout the intervention, while the MICT group spent 42% of time at intensities of 40%-59% HRR.

The study was limited by a small sample size of high-functioning individuals who sustained a mild stroke. Enrollment was halted for 2 years due to the COVID-19 lockdowns, limiting the study’s statistical power.

Nevertheless, the authors concluded, “Given that a lack of time is a significant barrier to the implementation of aerobic exercise in stroke clinical practice, our findings suggest that short-interval HIIT may be an effective alternative to traditional MICT for improving VO2peak after stroke, with potential clinically meaningful benefits sustained in the short-term.”

“Our findings show that a short HIIT protocol is possible in people with stroke, which is exciting to see,” said Tang. “But there are different factors that clinicians should consider before recommending this training for their patients, such as their health status and their physical status. Stroke rehabilitation specialists, including stroke physical therapists, can advise on how to proceed to ensure the safety and effectiveness of HIIT.”

Selected Patients May Benefit

“Broad implementation of this intervention may be premature without further research,” said Ryan Glatt, CPT, senior brain health coach and director of the FitBrain Program at Pacific Neuroscience Institute in Santa Monica, California. “The study focused on relatively high-functioning stroke survivors, which raises questions about the applicability of the results to those with more severe impairments.” Mr. Glatt did not participate in the research.

“Additional studies are needed to confirm whether these findings are applicable to more diverse and severely affected populations and to assess the long-term sustainability of the benefits observed,” he said. “Also, the lack of significant improvements in other critical outcomes, such as mobility, suggests limitations in the broader application of HIIT for stroke rehabilitation.”

“While HIIT shows potential, it should be approached with caution,” Mr. Glatt continued. “It may benefit select patients, but replacing traditional exercise protocols with HIIT should not be done in all cases. More robust evidence and careful consideration of individual patient needs are essential.”

This study was funded by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Tang reported grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Physiotherapy Foundation of Canada, and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Mr. Glatt declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a multicenter randomized controlled trial.

“We hoped that we would see improvements in cardiovascular fitness after HIIT and anticipated that these improvements would be greater than in the moderate-intensity group, but we were pleasantly surprised by the degree of improvement we observed,” said Ada Tang, PT, PhD, associate professor of health sciences at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. “The improvements seen in the HIIT group were twofold higher than in the other group.”

The results were published in Stroke.

Clinically Meaningful

Researchers compared the effects of 12 weeks of short-interval HIIT with those of moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) on peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak), cardiovascular risk factors, and mobility outcomes after stroke.

They randomly assigned participants to receive 3 days per week of HIIT or traditional moderate exercise sessions for 12 weeks. Participants’ mean age was 65 years, and 39% were women. They enrolled at a mean age of 1.8 years after sustaining a mild stroke.

A total of 42 participants were randomized to HIIT and 40 to MICT. There were no significant differences between the groups at baseline, and both groups exercised on adaptive recumbent steppers, which are suitable for stroke survivors with varying abilities.

The short-interval HIIT protocol involved 10 1-minute intervals of high-intensity exercise, interspersed with nine 1-minute low-intensity intervals, for a total of 19 minutes. HIIT intervals targeted 80% heart rate reserve (HRR) and progressed by 10% every 4 weeks up to 100% HRR. The low-intensity intervals targeted 30% HRR.

The traditional MICT protocol for stroke rehabilitation targeted 40% HRR for 20 minutes and progressed by 10% HRR and 5 minutes every 4 weeks, up to 60% HRR for 30 minutes.

The HIIT group’s cardiorespiratory fitness levels (VO2peak) improved twice as much as those of the MICT group: 3.5 mL of oxygen consumed in 1 minute per kg of body weight (mL/kg/min) compared with 1.8 mL/kg/min.

Of note, changes in VO2peak from baseline remained above the clinically important threshold of 1.0 mL/kg/min at 8-week follow-up in the HIIT group (1.71 mL/kg/min) but not in the MICT group (0.67 mL/kg/min).

Both groups increased their 6-minute walk test distances by 8.8 m at 12 weeks and by 18.5 m at 20 weeks. No between-group differences were found for cardiovascular risk or mobility outcomes, and no adverse events occurred in either group.

On average, the HIIT group spent 36% of total training time exercising at intensities above 80% HRR throughout the intervention, while the MICT group spent 42% of time at intensities of 40%-59% HRR.

The study was limited by a small sample size of high-functioning individuals who sustained a mild stroke. Enrollment was halted for 2 years due to the COVID-19 lockdowns, limiting the study’s statistical power.

Nevertheless, the authors concluded, “Given that a lack of time is a significant barrier to the implementation of aerobic exercise in stroke clinical practice, our findings suggest that short-interval HIIT may be an effective alternative to traditional MICT for improving VO2peak after stroke, with potential clinically meaningful benefits sustained in the short-term.”

“Our findings show that a short HIIT protocol is possible in people with stroke, which is exciting to see,” said Tang. “But there are different factors that clinicians should consider before recommending this training for their patients, such as their health status and their physical status. Stroke rehabilitation specialists, including stroke physical therapists, can advise on how to proceed to ensure the safety and effectiveness of HIIT.”

Selected Patients May Benefit

“Broad implementation of this intervention may be premature without further research,” said Ryan Glatt, CPT, senior brain health coach and director of the FitBrain Program at Pacific Neuroscience Institute in Santa Monica, California. “The study focused on relatively high-functioning stroke survivors, which raises questions about the applicability of the results to those with more severe impairments.” Mr. Glatt did not participate in the research.

“Additional studies are needed to confirm whether these findings are applicable to more diverse and severely affected populations and to assess the long-term sustainability of the benefits observed,” he said. “Also, the lack of significant improvements in other critical outcomes, such as mobility, suggests limitations in the broader application of HIIT for stroke rehabilitation.”

“While HIIT shows potential, it should be approached with caution,” Mr. Glatt continued. “It may benefit select patients, but replacing traditional exercise protocols with HIIT should not be done in all cases. More robust evidence and careful consideration of individual patient needs are essential.”

This study was funded by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Tang reported grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Physiotherapy Foundation of Canada, and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Mr. Glatt declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a multicenter randomized controlled trial.

“We hoped that we would see improvements in cardiovascular fitness after HIIT and anticipated that these improvements would be greater than in the moderate-intensity group, but we were pleasantly surprised by the degree of improvement we observed,” said Ada Tang, PT, PhD, associate professor of health sciences at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. “The improvements seen in the HIIT group were twofold higher than in the other group.”

The results were published in Stroke.

Clinically Meaningful

Researchers compared the effects of 12 weeks of short-interval HIIT with those of moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) on peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak), cardiovascular risk factors, and mobility outcomes after stroke.

They randomly assigned participants to receive 3 days per week of HIIT or traditional moderate exercise sessions for 12 weeks. Participants’ mean age was 65 years, and 39% were women. They enrolled at a mean age of 1.8 years after sustaining a mild stroke.

A total of 42 participants were randomized to HIIT and 40 to MICT. There were no significant differences between the groups at baseline, and both groups exercised on adaptive recumbent steppers, which are suitable for stroke survivors with varying abilities.

The short-interval HIIT protocol involved 10 1-minute intervals of high-intensity exercise, interspersed with nine 1-minute low-intensity intervals, for a total of 19 minutes. HIIT intervals targeted 80% heart rate reserve (HRR) and progressed by 10% every 4 weeks up to 100% HRR. The low-intensity intervals targeted 30% HRR.

The traditional MICT protocol for stroke rehabilitation targeted 40% HRR for 20 minutes and progressed by 10% HRR and 5 minutes every 4 weeks, up to 60% HRR for 30 minutes.

The HIIT group’s cardiorespiratory fitness levels (VO2peak) improved twice as much as those of the MICT group: 3.5 mL of oxygen consumed in 1 minute per kg of body weight (mL/kg/min) compared with 1.8 mL/kg/min.

Of note, changes in VO2peak from baseline remained above the clinically important threshold of 1.0 mL/kg/min at 8-week follow-up in the HIIT group (1.71 mL/kg/min) but not in the MICT group (0.67 mL/kg/min).

Both groups increased their 6-minute walk test distances by 8.8 m at 12 weeks and by 18.5 m at 20 weeks. No between-group differences were found for cardiovascular risk or mobility outcomes, and no adverse events occurred in either group.

On average, the HIIT group spent 36% of total training time exercising at intensities above 80% HRR throughout the intervention, while the MICT group spent 42% of time at intensities of 40%-59% HRR.

The study was limited by a small sample size of high-functioning individuals who sustained a mild stroke. Enrollment was halted for 2 years due to the COVID-19 lockdowns, limiting the study’s statistical power.

Nevertheless, the authors concluded, “Given that a lack of time is a significant barrier to the implementation of aerobic exercise in stroke clinical practice, our findings suggest that short-interval HIIT may be an effective alternative to traditional MICT for improving VO2peak after stroke, with potential clinically meaningful benefits sustained in the short-term.”

“Our findings show that a short HIIT protocol is possible in people with stroke, which is exciting to see,” said Tang. “But there are different factors that clinicians should consider before recommending this training for their patients, such as their health status and their physical status. Stroke rehabilitation specialists, including stroke physical therapists, can advise on how to proceed to ensure the safety and effectiveness of HIIT.”

Selected Patients May Benefit

“Broad implementation of this intervention may be premature without further research,” said Ryan Glatt, CPT, senior brain health coach and director of the FitBrain Program at Pacific Neuroscience Institute in Santa Monica, California. “The study focused on relatively high-functioning stroke survivors, which raises questions about the applicability of the results to those with more severe impairments.” Mr. Glatt did not participate in the research.

“Additional studies are needed to confirm whether these findings are applicable to more diverse and severely affected populations and to assess the long-term sustainability of the benefits observed,” he said. “Also, the lack of significant improvements in other critical outcomes, such as mobility, suggests limitations in the broader application of HIIT for stroke rehabilitation.”

“While HIIT shows potential, it should be approached with caution,” Mr. Glatt continued. “It may benefit select patients, but replacing traditional exercise protocols with HIIT should not be done in all cases. More robust evidence and careful consideration of individual patient needs are essential.”

This study was funded by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Tang reported grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Physiotherapy Foundation of Canada, and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Mr. Glatt declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Just A Single Night of Poor Sleep May Change Serum Proteins

wrote Alvhild Alette Bjørkum, MD, of Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen, and colleagues.

In a pilot study published in Sleep Advances, the researchers recruited eight healthy adult women aged 22-57 years with no history of neurologic or psychiatric problems to participate in a study of the effect of compromised sleep on protein profiles, with implications for effects on cells, tissues, and organ systems. Each of the participants served as their own controls, and blood samples were taken after 6 hours of sleep at night, and again after 6 hours of sleep deprivation the following night.

The researchers identified analyzed 494 proteins using mass spectrometry. Of these, 66 were differentially expressed after 6 hours of sleep deprivation. The top enriched biologic processes of these significantly changed proteins were protein activation cascade, platelet degranulation, blood coagulation, and hemostasis.

Further analysis using gene ontology showed changes in response to sleep deprivation in biologic process, molecular function, and immune system process categories, including specific associations related to wound healing, cholesterol transport, high-density lipoprotein particle receptor binding, and granulocyte chemotaxis.

The findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size, inclusion only of adult females, and the use of data from only 1 night of sleep deprivation, the researchers noted. However, the results support previous studies showing a negative impact of sleep deprivation on biologic functions, they said.

“Our study was able to reveal another set of human serum proteins that were altered by sleep deprivation and could connect similar biological processes to sleep deprivation that have been identified before with slightly different methods,” the researchers concluded. The study findings add to the knowledge base for the protein profiling of sleep deprivation, which may inform the development of tools to manage lack of sleep and mistimed sleep, particularly in shift workers.

Too Soon for Clinical Implications

“The adverse impact of poor sleep across many organ systems is gaining recognition, but the mechanisms underlying sleep-related pathology are not well understood,” Evan L. Brittain, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, said in an interview. “Studies like this begin to shed light on the mechanisms by which poor or reduced sleep affects specific bodily functions,” added Dr. Brittain, who was not involved in the study.

“The effects of other acute physiologic stressor such as exercise on the circulating proteome are well described. In that regard, it is not surprising that a brief episode of sleep deprivation would lead to detectable changes in the circulation,” Dr. Brittain said.

However, the specific changes reported in this study are difficult to interpret because of methodological and analytical concerns, particularly the small sample size, lack of an external validation cohort, and absence of appropriate statistical adjustments in the results, Dr. Brittain noted. These limitations prevent consideration of clinical implications without further study.

The study received no outside funding. Neither the researchers nor Dr. Brittain disclosed any conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

wrote Alvhild Alette Bjørkum, MD, of Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen, and colleagues.

In a pilot study published in Sleep Advances, the researchers recruited eight healthy adult women aged 22-57 years with no history of neurologic or psychiatric problems to participate in a study of the effect of compromised sleep on protein profiles, with implications for effects on cells, tissues, and organ systems. Each of the participants served as their own controls, and blood samples were taken after 6 hours of sleep at night, and again after 6 hours of sleep deprivation the following night.

The researchers identified analyzed 494 proteins using mass spectrometry. Of these, 66 were differentially expressed after 6 hours of sleep deprivation. The top enriched biologic processes of these significantly changed proteins were protein activation cascade, platelet degranulation, blood coagulation, and hemostasis.

Further analysis using gene ontology showed changes in response to sleep deprivation in biologic process, molecular function, and immune system process categories, including specific associations related to wound healing, cholesterol transport, high-density lipoprotein particle receptor binding, and granulocyte chemotaxis.

The findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size, inclusion only of adult females, and the use of data from only 1 night of sleep deprivation, the researchers noted. However, the results support previous studies showing a negative impact of sleep deprivation on biologic functions, they said.

“Our study was able to reveal another set of human serum proteins that were altered by sleep deprivation and could connect similar biological processes to sleep deprivation that have been identified before with slightly different methods,” the researchers concluded. The study findings add to the knowledge base for the protein profiling of sleep deprivation, which may inform the development of tools to manage lack of sleep and mistimed sleep, particularly in shift workers.

Too Soon for Clinical Implications

“The adverse impact of poor sleep across many organ systems is gaining recognition, but the mechanisms underlying sleep-related pathology are not well understood,” Evan L. Brittain, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, said in an interview. “Studies like this begin to shed light on the mechanisms by which poor or reduced sleep affects specific bodily functions,” added Dr. Brittain, who was not involved in the study.

“The effects of other acute physiologic stressor such as exercise on the circulating proteome are well described. In that regard, it is not surprising that a brief episode of sleep deprivation would lead to detectable changes in the circulation,” Dr. Brittain said.

However, the specific changes reported in this study are difficult to interpret because of methodological and analytical concerns, particularly the small sample size, lack of an external validation cohort, and absence of appropriate statistical adjustments in the results, Dr. Brittain noted. These limitations prevent consideration of clinical implications without further study.

The study received no outside funding. Neither the researchers nor Dr. Brittain disclosed any conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

wrote Alvhild Alette Bjørkum, MD, of Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen, and colleagues.

In a pilot study published in Sleep Advances, the researchers recruited eight healthy adult women aged 22-57 years with no history of neurologic or psychiatric problems to participate in a study of the effect of compromised sleep on protein profiles, with implications for effects on cells, tissues, and organ systems. Each of the participants served as their own controls, and blood samples were taken after 6 hours of sleep at night, and again after 6 hours of sleep deprivation the following night.

The researchers identified analyzed 494 proteins using mass spectrometry. Of these, 66 were differentially expressed after 6 hours of sleep deprivation. The top enriched biologic processes of these significantly changed proteins were protein activation cascade, platelet degranulation, blood coagulation, and hemostasis.

Further analysis using gene ontology showed changes in response to sleep deprivation in biologic process, molecular function, and immune system process categories, including specific associations related to wound healing, cholesterol transport, high-density lipoprotein particle receptor binding, and granulocyte chemotaxis.

The findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size, inclusion only of adult females, and the use of data from only 1 night of sleep deprivation, the researchers noted. However, the results support previous studies showing a negative impact of sleep deprivation on biologic functions, they said.

“Our study was able to reveal another set of human serum proteins that were altered by sleep deprivation and could connect similar biological processes to sleep deprivation that have been identified before with slightly different methods,” the researchers concluded. The study findings add to the knowledge base for the protein profiling of sleep deprivation, which may inform the development of tools to manage lack of sleep and mistimed sleep, particularly in shift workers.

Too Soon for Clinical Implications

“The adverse impact of poor sleep across many organ systems is gaining recognition, but the mechanisms underlying sleep-related pathology are not well understood,” Evan L. Brittain, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, said in an interview. “Studies like this begin to shed light on the mechanisms by which poor or reduced sleep affects specific bodily functions,” added Dr. Brittain, who was not involved in the study.

“The effects of other acute physiologic stressor such as exercise on the circulating proteome are well described. In that regard, it is not surprising that a brief episode of sleep deprivation would lead to detectable changes in the circulation,” Dr. Brittain said.

However, the specific changes reported in this study are difficult to interpret because of methodological and analytical concerns, particularly the small sample size, lack of an external validation cohort, and absence of appropriate statistical adjustments in the results, Dr. Brittain noted. These limitations prevent consideration of clinical implications without further study.

The study received no outside funding. Neither the researchers nor Dr. Brittain disclosed any conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SLEEP ADVANCES

No Surprises Act: Private Equity Scores Big in Arbitrations

Four organizations owned by private equity firms — including two provider groups — dominated the No Surprises Act’s disputed bill arbitration process in its first year, filing about 70% of 657,040 cases against insurers in 2023, a new report finds.

The findings, recently published in Health Affairs, suggest that private equity–owned organizations are forcefully challenging insurers about payments for certain kinds of out-of-network care.

Their fighting stance has paid off: The percentage of resolved arbitration cases won by providers jumped from 72% in the first quarter of 2023 to 85% in the last quarter, and they were awarded a median of more than 300% the contracted in-network rates for the services in question.

With many more out-of-network bills disputed by providers than expected, “the system is not working exactly the way it was anticipated when this law was written,” lead author Jack Hoadley, PhD, a research professor emeritus at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, Washington, DC, told this news organization.

And, he said, the public and the federal government may end up paying a price.

Congress passed the No Surprises Act in 2020 and then-President Donald Trump signed it. The landmark bill, which went into effect in 2022, was designed to protect patients from unexpected and often exorbitant “surprise” bills after they received some kinds of out-of-network care.

Now, many types of providers are forbidden from billing patients beyond normal in-network costs. In these cases, health plans and out-of-network providers — who don’t have mutual agreements — must wrangle over payment amounts, which are intended to not exceed inflation-adjusted 2019 median levels.

A binding arbitration process kicks in when a provider and a health plan fail to agree about how much the plan will pay for a service. Then, a third-party arbitrator is called in to make a ruling that’s binding. The process is controversial, and a flurry of lawsuits from providers have challenged it.

The new report, which updates an earlier analysis, examines data about disputed cases from all of 2023.

Of the 657,040 new cases filed in 2023, about 70% came from four private equity-funded organizations: Team Health, SCP Health, Radiology Partners, and Envision, which each provide physician services.

About half of the 2023 cases were from just four states: Texas, Florida, Tennessee, and Georgia. The report says the four organizations are especially active in those states. In contrast, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Washington state each had just 1500 or fewer cases filed last year.

Health plans challenged a third of cases as ineligible, and 22% of all resolved cases were deemed ineligible.

Providers won 80% of resolved challenges in 2023, although it’s not clear how much money they reaped. Still, it’s clear that “in the vast majority of the cases, insurers have to pay larger amounts to the provider,” Dr. Hoadley said.

Radiologists made a median of at least 500% of the in-network rate in their cases. Surgeons and neurologists made even more money — a median of at least 800% of the in-network rate. Overall, providers made 322%-350% of in-network rates, depending on the quarter.

Dr. Hoadley cautioned that only a small percentage of medical payments are disputed. In those cases, “the amount that the insurer offers is accepted, and that’s the end of the story.”

Why are the providers often reaping much more than typical payments for in-network services? It’s “really hard to know,” Dr. Hoadley said. But one factor, he said, may be the fact that providers are able to offer evidence challenging that amounts that insurers say they paid previously: “Hey, when we were in network, we were paid this much.”

It’s not clear whether the dispute-and-arbitration system will cost insurers — and patients — more in the long run. The Congressional Budget Office actually thought the No Surprises Act might lower the growth of premiums slightly and save the federal government money, Dr. Hoadley said, but that could potentially not happen. The flood of litigation also contributes to uncertainty, he said.

Alan Sager, PhD, professor of Health Law, Policy, and Management at Boston University School of Public Health, told this news organization that premiums are bound to rise as insurers react to higher costs. He also expects that providers will question the value of being in-network. “If you’re out-of-network and can obtain much higher payments, why would any doctor or hospital remain in-network, especially since they don’t lose out on patient volume?”

Why are provider groups owned by private equity firms so aggressive at challenging health plans? Loren Adler, a fellow and associate director of the Brookings Institution’s Center on Health Policy, told this news organization that these companies play large roles in fields affected by the No Surprises Act. These include emergency medicine, radiology, and anesthesiology, said Mr. Adler, who’s also studied the No Surprises Act’s dispute/arbitration system.

Mr. Adler added that larger companies “are better suited to deal with technical complexities of this process and spend the sort of upfront money to go through it.”

In the big picture, Mr. Adler said, the new study “raises question of whether Congress at some point wants to try to basically bring prices from the arbitration process back in line with average in-network prices.”

The study was funded by the Commonwealth Fund and Arnold Ventures. Dr. Hoadley, Dr. Sager, and Mr. Adler had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Four organizations owned by private equity firms — including two provider groups — dominated the No Surprises Act’s disputed bill arbitration process in its first year, filing about 70% of 657,040 cases against insurers in 2023, a new report finds.

The findings, recently published in Health Affairs, suggest that private equity–owned organizations are forcefully challenging insurers about payments for certain kinds of out-of-network care.

Their fighting stance has paid off: The percentage of resolved arbitration cases won by providers jumped from 72% in the first quarter of 2023 to 85% in the last quarter, and they were awarded a median of more than 300% the contracted in-network rates for the services in question.

With many more out-of-network bills disputed by providers than expected, “the system is not working exactly the way it was anticipated when this law was written,” lead author Jack Hoadley, PhD, a research professor emeritus at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, Washington, DC, told this news organization.

And, he said, the public and the federal government may end up paying a price.

Congress passed the No Surprises Act in 2020 and then-President Donald Trump signed it. The landmark bill, which went into effect in 2022, was designed to protect patients from unexpected and often exorbitant “surprise” bills after they received some kinds of out-of-network care.

Now, many types of providers are forbidden from billing patients beyond normal in-network costs. In these cases, health plans and out-of-network providers — who don’t have mutual agreements — must wrangle over payment amounts, which are intended to not exceed inflation-adjusted 2019 median levels.

A binding arbitration process kicks in when a provider and a health plan fail to agree about how much the plan will pay for a service. Then, a third-party arbitrator is called in to make a ruling that’s binding. The process is controversial, and a flurry of lawsuits from providers have challenged it.

The new report, which updates an earlier analysis, examines data about disputed cases from all of 2023.

Of the 657,040 new cases filed in 2023, about 70% came from four private equity-funded organizations: Team Health, SCP Health, Radiology Partners, and Envision, which each provide physician services.

About half of the 2023 cases were from just four states: Texas, Florida, Tennessee, and Georgia. The report says the four organizations are especially active in those states. In contrast, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Washington state each had just 1500 or fewer cases filed last year.

Health plans challenged a third of cases as ineligible, and 22% of all resolved cases were deemed ineligible.

Providers won 80% of resolved challenges in 2023, although it’s not clear how much money they reaped. Still, it’s clear that “in the vast majority of the cases, insurers have to pay larger amounts to the provider,” Dr. Hoadley said.

Radiologists made a median of at least 500% of the in-network rate in their cases. Surgeons and neurologists made even more money — a median of at least 800% of the in-network rate. Overall, providers made 322%-350% of in-network rates, depending on the quarter.

Dr. Hoadley cautioned that only a small percentage of medical payments are disputed. In those cases, “the amount that the insurer offers is accepted, and that’s the end of the story.”

Why are the providers often reaping much more than typical payments for in-network services? It’s “really hard to know,” Dr. Hoadley said. But one factor, he said, may be the fact that providers are able to offer evidence challenging that amounts that insurers say they paid previously: “Hey, when we were in network, we were paid this much.”

It’s not clear whether the dispute-and-arbitration system will cost insurers — and patients — more in the long run. The Congressional Budget Office actually thought the No Surprises Act might lower the growth of premiums slightly and save the federal government money, Dr. Hoadley said, but that could potentially not happen. The flood of litigation also contributes to uncertainty, he said.

Alan Sager, PhD, professor of Health Law, Policy, and Management at Boston University School of Public Health, told this news organization that premiums are bound to rise as insurers react to higher costs. He also expects that providers will question the value of being in-network. “If you’re out-of-network and can obtain much higher payments, why would any doctor or hospital remain in-network, especially since they don’t lose out on patient volume?”

Why are provider groups owned by private equity firms so aggressive at challenging health plans? Loren Adler, a fellow and associate director of the Brookings Institution’s Center on Health Policy, told this news organization that these companies play large roles in fields affected by the No Surprises Act. These include emergency medicine, radiology, and anesthesiology, said Mr. Adler, who’s also studied the No Surprises Act’s dispute/arbitration system.

Mr. Adler added that larger companies “are better suited to deal with technical complexities of this process and spend the sort of upfront money to go through it.”

In the big picture, Mr. Adler said, the new study “raises question of whether Congress at some point wants to try to basically bring prices from the arbitration process back in line with average in-network prices.”

The study was funded by the Commonwealth Fund and Arnold Ventures. Dr. Hoadley, Dr. Sager, and Mr. Adler had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Four organizations owned by private equity firms — including two provider groups — dominated the No Surprises Act’s disputed bill arbitration process in its first year, filing about 70% of 657,040 cases against insurers in 2023, a new report finds.

The findings, recently published in Health Affairs, suggest that private equity–owned organizations are forcefully challenging insurers about payments for certain kinds of out-of-network care.

Their fighting stance has paid off: The percentage of resolved arbitration cases won by providers jumped from 72% in the first quarter of 2023 to 85% in the last quarter, and they were awarded a median of more than 300% the contracted in-network rates for the services in question.

With many more out-of-network bills disputed by providers than expected, “the system is not working exactly the way it was anticipated when this law was written,” lead author Jack Hoadley, PhD, a research professor emeritus at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, Washington, DC, told this news organization.

And, he said, the public and the federal government may end up paying a price.

Congress passed the No Surprises Act in 2020 and then-President Donald Trump signed it. The landmark bill, which went into effect in 2022, was designed to protect patients from unexpected and often exorbitant “surprise” bills after they received some kinds of out-of-network care.

Now, many types of providers are forbidden from billing patients beyond normal in-network costs. In these cases, health plans and out-of-network providers — who don’t have mutual agreements — must wrangle over payment amounts, which are intended to not exceed inflation-adjusted 2019 median levels.

A binding arbitration process kicks in when a provider and a health plan fail to agree about how much the plan will pay for a service. Then, a third-party arbitrator is called in to make a ruling that’s binding. The process is controversial, and a flurry of lawsuits from providers have challenged it.

The new report, which updates an earlier analysis, examines data about disputed cases from all of 2023.

Of the 657,040 new cases filed in 2023, about 70% came from four private equity-funded organizations: Team Health, SCP Health, Radiology Partners, and Envision, which each provide physician services.

About half of the 2023 cases were from just four states: Texas, Florida, Tennessee, and Georgia. The report says the four organizations are especially active in those states. In contrast, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Washington state each had just 1500 or fewer cases filed last year.

Health plans challenged a third of cases as ineligible, and 22% of all resolved cases were deemed ineligible.

Providers won 80% of resolved challenges in 2023, although it’s not clear how much money they reaped. Still, it’s clear that “in the vast majority of the cases, insurers have to pay larger amounts to the provider,” Dr. Hoadley said.

Radiologists made a median of at least 500% of the in-network rate in their cases. Surgeons and neurologists made even more money — a median of at least 800% of the in-network rate. Overall, providers made 322%-350% of in-network rates, depending on the quarter.

Dr. Hoadley cautioned that only a small percentage of medical payments are disputed. In those cases, “the amount that the insurer offers is accepted, and that’s the end of the story.”

Why are the providers often reaping much more than typical payments for in-network services? It’s “really hard to know,” Dr. Hoadley said. But one factor, he said, may be the fact that providers are able to offer evidence challenging that amounts that insurers say they paid previously: “Hey, when we were in network, we were paid this much.”

It’s not clear whether the dispute-and-arbitration system will cost insurers — and patients — more in the long run. The Congressional Budget Office actually thought the No Surprises Act might lower the growth of premiums slightly and save the federal government money, Dr. Hoadley said, but that could potentially not happen. The flood of litigation also contributes to uncertainty, he said.

Alan Sager, PhD, professor of Health Law, Policy, and Management at Boston University School of Public Health, told this news organization that premiums are bound to rise as insurers react to higher costs. He also expects that providers will question the value of being in-network. “If you’re out-of-network and can obtain much higher payments, why would any doctor or hospital remain in-network, especially since they don’t lose out on patient volume?”

Why are provider groups owned by private equity firms so aggressive at challenging health plans? Loren Adler, a fellow and associate director of the Brookings Institution’s Center on Health Policy, told this news organization that these companies play large roles in fields affected by the No Surprises Act. These include emergency medicine, radiology, and anesthesiology, said Mr. Adler, who’s also studied the No Surprises Act’s dispute/arbitration system.

Mr. Adler added that larger companies “are better suited to deal with technical complexities of this process and spend the sort of upfront money to go through it.”

In the big picture, Mr. Adler said, the new study “raises question of whether Congress at some point wants to try to basically bring prices from the arbitration process back in line with average in-network prices.”

The study was funded by the Commonwealth Fund and Arnold Ventures. Dr. Hoadley, Dr. Sager, and Mr. Adler had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Untreated Hypertension Tied to Alzheimer’s Disease Risk

TOPLINE:

Older adults with untreated hypertension have a 36% increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) compared with those without hypertension and a 42% increased risk for AD compared with those with treated hypertension.

METHODOLOGY:

- In this meta-analysis, researchers analyzed the data of 31,250 participants aged 60 years or older (mean age, 72.1 years; 41% men) from 14 community-based studies across 14 countries.

- Mean follow-up was 4.2 years, and blood pressure measurements, hypertension diagnosis, and antihypertensive medication use were recorded.

- Overall, 35.9% had no history of hypertension or antihypertensive medication use, 50.7% had a history of hypertension with antihypertensive medication use, and 9.4% had a history of hypertension without antihypertensive medication use.

- The main outcomes were AD and non-AD dementia.

TAKEAWAY:

- In total, 1415 participants developed AD, and 681 developed non-AD dementia.

- Participants with untreated hypertension had a 36% increased risk for AD compared with healthy controls (hazard ratio [HR], 1.36; P = .041) and a 42% increased risk for AD (HR, 1.42; P = .013) compared with those with treated hypertension.

- Compared with healthy controls, patients with treated hypertension did not show an elevated risk for AD (HR, 0.961; P = .6644).

- Patients with both treated (HR, 1.285; P = .027) and untreated (HR, 1.693; P = .003) hypertension had an increased risk for non-AD dementia compared with healthy controls. Patients with treated and untreated hypertension had a similar risk for non-AD dementia.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results suggest that treating high blood pressure as a person ages continues to be a crucial factor in reducing their risk of Alzheimer’s disease,” the lead author Matthew J. Lennon, MD, PhD, said in a press release.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Matthew J. Lennon, MD, PhD, School of Clinical Medicine, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia. It was published online in Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

Varied definitions for hypertension across different locations might have led to discrepancies in diagnosis. Additionally, the study did not account for potential confounders such as stroke, transient ischemic attack, and heart disease, which may act as mediators rather than covariates. Furthermore, the study did not report mortality data, which may have affected the interpretation of dementia risk.

DISCLOSURES:

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Some authors reported ties with several institutions and pharmaceutical companies outside this work. Full disclosures are available in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Older adults with untreated hypertension have a 36% increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) compared with those without hypertension and a 42% increased risk for AD compared with those with treated hypertension.

METHODOLOGY:

- In this meta-analysis, researchers analyzed the data of 31,250 participants aged 60 years or older (mean age, 72.1 years; 41% men) from 14 community-based studies across 14 countries.

- Mean follow-up was 4.2 years, and blood pressure measurements, hypertension diagnosis, and antihypertensive medication use were recorded.

- Overall, 35.9% had no history of hypertension or antihypertensive medication use, 50.7% had a history of hypertension with antihypertensive medication use, and 9.4% had a history of hypertension without antihypertensive medication use.

- The main outcomes were AD and non-AD dementia.

TAKEAWAY:

- In total, 1415 participants developed AD, and 681 developed non-AD dementia.

- Participants with untreated hypertension had a 36% increased risk for AD compared with healthy controls (hazard ratio [HR], 1.36; P = .041) and a 42% increased risk for AD (HR, 1.42; P = .013) compared with those with treated hypertension.

- Compared with healthy controls, patients with treated hypertension did not show an elevated risk for AD (HR, 0.961; P = .6644).

- Patients with both treated (HR, 1.285; P = .027) and untreated (HR, 1.693; P = .003) hypertension had an increased risk for non-AD dementia compared with healthy controls. Patients with treated and untreated hypertension had a similar risk for non-AD dementia.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results suggest that treating high blood pressure as a person ages continues to be a crucial factor in reducing their risk of Alzheimer’s disease,” the lead author Matthew J. Lennon, MD, PhD, said in a press release.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Matthew J. Lennon, MD, PhD, School of Clinical Medicine, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia. It was published online in Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

Varied definitions for hypertension across different locations might have led to discrepancies in diagnosis. Additionally, the study did not account for potential confounders such as stroke, transient ischemic attack, and heart disease, which may act as mediators rather than covariates. Furthermore, the study did not report mortality data, which may have affected the interpretation of dementia risk.

DISCLOSURES:

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Some authors reported ties with several institutions and pharmaceutical companies outside this work. Full disclosures are available in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Older adults with untreated hypertension have a 36% increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) compared with those without hypertension and a 42% increased risk for AD compared with those with treated hypertension.

METHODOLOGY:

- In this meta-analysis, researchers analyzed the data of 31,250 participants aged 60 years or older (mean age, 72.1 years; 41% men) from 14 community-based studies across 14 countries.

- Mean follow-up was 4.2 years, and blood pressure measurements, hypertension diagnosis, and antihypertensive medication use were recorded.

- Overall, 35.9% had no history of hypertension or antihypertensive medication use, 50.7% had a history of hypertension with antihypertensive medication use, and 9.4% had a history of hypertension without antihypertensive medication use.

- The main outcomes were AD and non-AD dementia.

TAKEAWAY:

- In total, 1415 participants developed AD, and 681 developed non-AD dementia.

- Participants with untreated hypertension had a 36% increased risk for AD compared with healthy controls (hazard ratio [HR], 1.36; P = .041) and a 42% increased risk for AD (HR, 1.42; P = .013) compared with those with treated hypertension.

- Compared with healthy controls, patients with treated hypertension did not show an elevated risk for AD (HR, 0.961; P = .6644).

- Patients with both treated (HR, 1.285; P = .027) and untreated (HR, 1.693; P = .003) hypertension had an increased risk for non-AD dementia compared with healthy controls. Patients with treated and untreated hypertension had a similar risk for non-AD dementia.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results suggest that treating high blood pressure as a person ages continues to be a crucial factor in reducing their risk of Alzheimer’s disease,” the lead author Matthew J. Lennon, MD, PhD, said in a press release.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Matthew J. Lennon, MD, PhD, School of Clinical Medicine, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia. It was published online in Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

Varied definitions for hypertension across different locations might have led to discrepancies in diagnosis. Additionally, the study did not account for potential confounders such as stroke, transient ischemic attack, and heart disease, which may act as mediators rather than covariates. Furthermore, the study did not report mortality data, which may have affected the interpretation of dementia risk.

DISCLOSURES:

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Some authors reported ties with several institutions and pharmaceutical companies outside this work. Full disclosures are available in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Veterans Found Relief From Chronic Pain Through Telehealth Mindfulness

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a randomized clinical trial of 811 veterans who had moderate to severe chronic pain and were recruited from three Veterans Affairs facilities in the United States.

- Participants were divided into three groups: Group MBI (270), self-paced MBI (271), and usual care (270), with interventions lasting 8 weeks.

- The primary outcome was pain-related function measured using a scale on interference from pain in areas like mood, walking, work, relationships, and sleep at 10 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year.

- Secondary outcomes included pain intensity, anxiety, fatigue, sleep disturbance, participation in social roles and activities, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

TAKEAWAY:

- Pain-related function significantly improved in participants in both the MBI groups versus usual care group, with a mean difference of −0.4 (95% CI, −0.7 to −0.2) for group MBI and −0.7 (95% CI, −1.0 to −0.4) for self-paced MBI (P < .001).

- Compared with the usual care group, both the MBI groups had significantly improved secondary outcomes, including pain intensity, depression, and PTSD.

- The probability of achieving 30% improvement in pain-related function was higher for group MBI at 10 weeks and 6 months and for self-paced MBI at all three timepoints.

- No significant differences were found between the MBI groups for primary and secondary outcomes.

IN PRACTICE:

“The viability and similarity of both these approaches for delivering MBIs increase patient options for meeting their individual needs and could help accelerate and improve the implementation of nonpharmacological pain treatment in health care systems,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Diana J. Burgess, PhD, of the Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research, VA Health Systems Research in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

The trial was not designed to compare less resource-intensive MBIs with more intensive mindfulness-based stress reduction programs or in-person MBIs. The study did not address cost-effectiveness or control for time, attention, and other contextual factors. The high nonresponse rate (81%) to initial recruitment may have affected the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Pain Management Collaboratory–Pragmatic Clinical Trials Demonstration. Various authors reported grants from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health and the National Institute of Nursing Research.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a randomized clinical trial of 811 veterans who had moderate to severe chronic pain and were recruited from three Veterans Affairs facilities in the United States.

- Participants were divided into three groups: Group MBI (270), self-paced MBI (271), and usual care (270), with interventions lasting 8 weeks.

- The primary outcome was pain-related function measured using a scale on interference from pain in areas like mood, walking, work, relationships, and sleep at 10 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year.

- Secondary outcomes included pain intensity, anxiety, fatigue, sleep disturbance, participation in social roles and activities, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

TAKEAWAY:

- Pain-related function significantly improved in participants in both the MBI groups versus usual care group, with a mean difference of −0.4 (95% CI, −0.7 to −0.2) for group MBI and −0.7 (95% CI, −1.0 to −0.4) for self-paced MBI (P < .001).

- Compared with the usual care group, both the MBI groups had significantly improved secondary outcomes, including pain intensity, depression, and PTSD.

- The probability of achieving 30% improvement in pain-related function was higher for group MBI at 10 weeks and 6 months and for self-paced MBI at all three timepoints.

- No significant differences were found between the MBI groups for primary and secondary outcomes.

IN PRACTICE:

“The viability and similarity of both these approaches for delivering MBIs increase patient options for meeting their individual needs and could help accelerate and improve the implementation of nonpharmacological pain treatment in health care systems,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Diana J. Burgess, PhD, of the Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research, VA Health Systems Research in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

The trial was not designed to compare less resource-intensive MBIs with more intensive mindfulness-based stress reduction programs or in-person MBIs. The study did not address cost-effectiveness or control for time, attention, and other contextual factors. The high nonresponse rate (81%) to initial recruitment may have affected the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Pain Management Collaboratory–Pragmatic Clinical Trials Demonstration. Various authors reported grants from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health and the National Institute of Nursing Research.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a randomized clinical trial of 811 veterans who had moderate to severe chronic pain and were recruited from three Veterans Affairs facilities in the United States.

- Participants were divided into three groups: Group MBI (270), self-paced MBI (271), and usual care (270), with interventions lasting 8 weeks.

- The primary outcome was pain-related function measured using a scale on interference from pain in areas like mood, walking, work, relationships, and sleep at 10 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year.

- Secondary outcomes included pain intensity, anxiety, fatigue, sleep disturbance, participation in social roles and activities, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

TAKEAWAY:

- Pain-related function significantly improved in participants in both the MBI groups versus usual care group, with a mean difference of −0.4 (95% CI, −0.7 to −0.2) for group MBI and −0.7 (95% CI, −1.0 to −0.4) for self-paced MBI (P < .001).

- Compared with the usual care group, both the MBI groups had significantly improved secondary outcomes, including pain intensity, depression, and PTSD.

- The probability of achieving 30% improvement in pain-related function was higher for group MBI at 10 weeks and 6 months and for self-paced MBI at all three timepoints.

- No significant differences were found between the MBI groups for primary and secondary outcomes.

IN PRACTICE:

“The viability and similarity of both these approaches for delivering MBIs increase patient options for meeting their individual needs and could help accelerate and improve the implementation of nonpharmacological pain treatment in health care systems,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Diana J. Burgess, PhD, of the Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research, VA Health Systems Research in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

The trial was not designed to compare less resource-intensive MBIs with more intensive mindfulness-based stress reduction programs or in-person MBIs. The study did not address cost-effectiveness or control for time, attention, and other contextual factors. The high nonresponse rate (81%) to initial recruitment may have affected the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Pain Management Collaboratory–Pragmatic Clinical Trials Demonstration. Various authors reported grants from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health and the National Institute of Nursing Research.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer Treatment 101: A Primer for Non-Oncologists

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

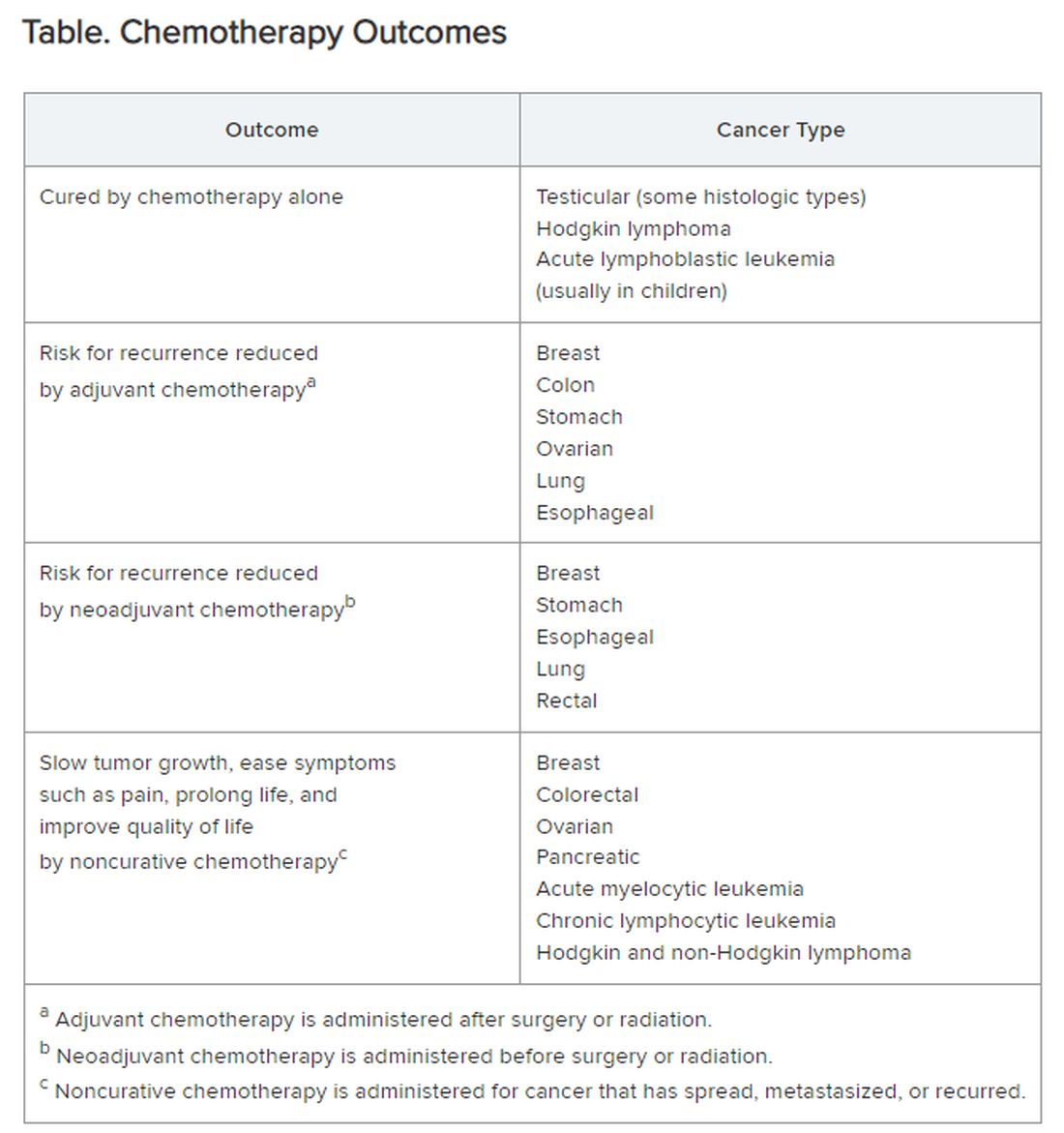

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.