User login

Neurology Reviews covers innovative and emerging news in neurology and neuroscience every month, with a focus on practical approaches to treating Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, headache, stroke, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, and other neurologic disorders.

PML

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Rituxan

The leading independent newspaper covering neurology news and commentary.

For many, long COVID’s impacts go on and on, major study says

in the same time frame, a large study out of Scotland found.

Multiple studies are evaluating people with long COVID in the hopes of figuring out why some people experience debilitating symptoms long after their primary infection ends and others either do not or recover more quickly.

This current study is notable for its large size – 96,238 people. Researchers checked in with participants at 6, 12, and 18 months, and included a group of people never infected with the coronavirus to help investigators make a stronger case.

“A lot of the symptoms of long COVID are nonspecific and therefore can occur in people never infected,” says senior study author Jill P. Pell, MD, head of the School of Health and Wellbeing at the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

Ruling out coincidence

This study shows that people experienced a wide range of symptoms after becoming infected with COVID-19 at a significantly higher rate than those who were never infected, “thereby confirming that they were genuinely associated with COVID and not merely a coincidence,” she said.

Among 21,525 people who had COVID-19 and had symptoms, tiredness, headache and muscle aches or muscle weakness were the most common ongoing symptoms.

Loss of smell was almost nine times more likely in this group compared to the never-infected group in one analysis where researchers controlled for other possible factors. The risk for loss of taste was almost six times greater, followed by risk of breathlessness at three times higher.

Long COVID risk was highest after a severe original infection and among older people, women, Black, and South Asian populations, people with socioeconomic disadvantages, and those with more than one underlying health condition.

Adding up the 6% with no recovery after 18 months and 42% with partial recovery means that between 6 and 18 months following symptomatic coronavirus infection, almost half of those infected still experience persistent symptoms.

Vaccination validated

On the plus side, people vaccinated against COVID-19 before getting infected had a lower risk for some persistent symptoms. In addition, Dr. Pell and colleagues found no evidence that people who experienced asymptomatic infection were likely to experience long COVID symptoms or challenges with activities of daily living.

The findings of the Long-COVID in Scotland Study (Long-CISS) were published in the journal Nature Communications.

‘More long COVID than ever before’

“Unfortunately, these long COVID symptoms are not getting better as the cases of COVID get milder,” said Thomas Gut, DO, medical director for the post-COVID recovery program at Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital. “Quite the opposite – this infection has become so common in a community because it’s so mild and spreading so rapidly that we’re seeing more long COVID symptoms than ever before.”

Although most patients he sees with long COVID resolve their symptoms within 3-6 months, “We do see some patients who require short-term disability because their symptoms continue past 6 months and out to 2 years,” said Dr. Gut, a hospitalist at Staten Island University Hospital, a member hospital of Northwell Health.

Patients with fatigue and neurocognitive symptoms “have a very tough time going back to work. Short-term disability gives them the time and finances to pursue specialty care with cardiology, pulmonary, and neurocognitive testing,” he said.

Support the whole person

The burden of living with long COVID goes beyond the persistent symptoms. “Long COVID can have wide-ranging impacts – not only on health but also quality of life and activities of daily living [including] work, mobility, self-care and more,” Dr. Pell said. “So, people with long COVID need support relevant to their individual needs and this may extend beyond the health care sector, for example including social services, school or workplace.”

Still, Lisa Penziner, RN, founder of the COVID Long Haulers Support Group in Westchester and Long Island, N.Y., said while people with the most severe cases of COVID-19 tended to have the worst long COVID symptoms, they’re not the only ones.

“We saw many post-COVID members who had mild cases and their long-haul symptoms were worse weeks later than the virus itself,” said Md. Penziner.

She estimates that 80%-90% of her support group members recover within 6 months. “However, there are others who were experiencing symptoms for much longer.”

Respiratory treatment, physical therapy, and other follow-up doctor visits are common after 6 months, for example.

“Additionally, there is a mental health component to recovery as well, meaning that the patient must learn to live while experiencing lingering, long-haul COVID symptoms in work and daily life,” said Ms. Penziner, director of special projects at North Westchester Restorative Therapy & Nursing.

In addition to ongoing medical care, people with long COVID need understanding, she said.

“While long-haul symptoms do not happen to everyone, it is proven that many do experience long-haul symptoms, and the support of the community in understanding is important.”

Limitations of the study

Dr. Pell and colleagues noted some strengths and weaknesses to their study. For example, “as a general population study, our findings provide a better indication of the overall risk and burden of long COVID than hospitalized cohorts,” they noted.

Also, the Scottish population is 96% White, so other long COVID studies with more diverse participants are warranted.

Another potential weakness is the response rate of 16% among those invited to participate in the study, which Dr. Pell and colleagues addressed: “Our cohort included a large sample (33,281) of people previously infected and the response rate of 16% overall and 20% among people who had symptomatic infection was consistent with previous studies that have used SMS text invitations as the sole method of recruitment.”

“We tell patients this should last 3-6 months, but some patients have longer recovery periods,” Dr. Gut said. “We’re here for them. We have a lot of services available to help get them through the recovery process, and we have a lot of options to help support them.”

“What we found most helpful is when there is peer-to-peer support, reaffirming to the member that they are not alone in the long-haul battle, which has been a major benefit of the support group,” Ms. Penziner said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

in the same time frame, a large study out of Scotland found.

Multiple studies are evaluating people with long COVID in the hopes of figuring out why some people experience debilitating symptoms long after their primary infection ends and others either do not or recover more quickly.

This current study is notable for its large size – 96,238 people. Researchers checked in with participants at 6, 12, and 18 months, and included a group of people never infected with the coronavirus to help investigators make a stronger case.

“A lot of the symptoms of long COVID are nonspecific and therefore can occur in people never infected,” says senior study author Jill P. Pell, MD, head of the School of Health and Wellbeing at the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

Ruling out coincidence

This study shows that people experienced a wide range of symptoms after becoming infected with COVID-19 at a significantly higher rate than those who were never infected, “thereby confirming that they were genuinely associated with COVID and not merely a coincidence,” she said.

Among 21,525 people who had COVID-19 and had symptoms, tiredness, headache and muscle aches or muscle weakness were the most common ongoing symptoms.

Loss of smell was almost nine times more likely in this group compared to the never-infected group in one analysis where researchers controlled for other possible factors. The risk for loss of taste was almost six times greater, followed by risk of breathlessness at three times higher.

Long COVID risk was highest after a severe original infection and among older people, women, Black, and South Asian populations, people with socioeconomic disadvantages, and those with more than one underlying health condition.

Adding up the 6% with no recovery after 18 months and 42% with partial recovery means that between 6 and 18 months following symptomatic coronavirus infection, almost half of those infected still experience persistent symptoms.

Vaccination validated

On the plus side, people vaccinated against COVID-19 before getting infected had a lower risk for some persistent symptoms. In addition, Dr. Pell and colleagues found no evidence that people who experienced asymptomatic infection were likely to experience long COVID symptoms or challenges with activities of daily living.

The findings of the Long-COVID in Scotland Study (Long-CISS) were published in the journal Nature Communications.

‘More long COVID than ever before’

“Unfortunately, these long COVID symptoms are not getting better as the cases of COVID get milder,” said Thomas Gut, DO, medical director for the post-COVID recovery program at Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital. “Quite the opposite – this infection has become so common in a community because it’s so mild and spreading so rapidly that we’re seeing more long COVID symptoms than ever before.”

Although most patients he sees with long COVID resolve their symptoms within 3-6 months, “We do see some patients who require short-term disability because their symptoms continue past 6 months and out to 2 years,” said Dr. Gut, a hospitalist at Staten Island University Hospital, a member hospital of Northwell Health.

Patients with fatigue and neurocognitive symptoms “have a very tough time going back to work. Short-term disability gives them the time and finances to pursue specialty care with cardiology, pulmonary, and neurocognitive testing,” he said.

Support the whole person

The burden of living with long COVID goes beyond the persistent symptoms. “Long COVID can have wide-ranging impacts – not only on health but also quality of life and activities of daily living [including] work, mobility, self-care and more,” Dr. Pell said. “So, people with long COVID need support relevant to their individual needs and this may extend beyond the health care sector, for example including social services, school or workplace.”

Still, Lisa Penziner, RN, founder of the COVID Long Haulers Support Group in Westchester and Long Island, N.Y., said while people with the most severe cases of COVID-19 tended to have the worst long COVID symptoms, they’re not the only ones.

“We saw many post-COVID members who had mild cases and their long-haul symptoms were worse weeks later than the virus itself,” said Md. Penziner.

She estimates that 80%-90% of her support group members recover within 6 months. “However, there are others who were experiencing symptoms for much longer.”

Respiratory treatment, physical therapy, and other follow-up doctor visits are common after 6 months, for example.

“Additionally, there is a mental health component to recovery as well, meaning that the patient must learn to live while experiencing lingering, long-haul COVID symptoms in work and daily life,” said Ms. Penziner, director of special projects at North Westchester Restorative Therapy & Nursing.

In addition to ongoing medical care, people with long COVID need understanding, she said.

“While long-haul symptoms do not happen to everyone, it is proven that many do experience long-haul symptoms, and the support of the community in understanding is important.”

Limitations of the study

Dr. Pell and colleagues noted some strengths and weaknesses to their study. For example, “as a general population study, our findings provide a better indication of the overall risk and burden of long COVID than hospitalized cohorts,” they noted.

Also, the Scottish population is 96% White, so other long COVID studies with more diverse participants are warranted.

Another potential weakness is the response rate of 16% among those invited to participate in the study, which Dr. Pell and colleagues addressed: “Our cohort included a large sample (33,281) of people previously infected and the response rate of 16% overall and 20% among people who had symptomatic infection was consistent with previous studies that have used SMS text invitations as the sole method of recruitment.”

“We tell patients this should last 3-6 months, but some patients have longer recovery periods,” Dr. Gut said. “We’re here for them. We have a lot of services available to help get them through the recovery process, and we have a lot of options to help support them.”

“What we found most helpful is when there is peer-to-peer support, reaffirming to the member that they are not alone in the long-haul battle, which has been a major benefit of the support group,” Ms. Penziner said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

in the same time frame, a large study out of Scotland found.

Multiple studies are evaluating people with long COVID in the hopes of figuring out why some people experience debilitating symptoms long after their primary infection ends and others either do not or recover more quickly.

This current study is notable for its large size – 96,238 people. Researchers checked in with participants at 6, 12, and 18 months, and included a group of people never infected with the coronavirus to help investigators make a stronger case.

“A lot of the symptoms of long COVID are nonspecific and therefore can occur in people never infected,” says senior study author Jill P. Pell, MD, head of the School of Health and Wellbeing at the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

Ruling out coincidence

This study shows that people experienced a wide range of symptoms after becoming infected with COVID-19 at a significantly higher rate than those who were never infected, “thereby confirming that they were genuinely associated with COVID and not merely a coincidence,” she said.

Among 21,525 people who had COVID-19 and had symptoms, tiredness, headache and muscle aches or muscle weakness were the most common ongoing symptoms.

Loss of smell was almost nine times more likely in this group compared to the never-infected group in one analysis where researchers controlled for other possible factors. The risk for loss of taste was almost six times greater, followed by risk of breathlessness at three times higher.

Long COVID risk was highest after a severe original infection and among older people, women, Black, and South Asian populations, people with socioeconomic disadvantages, and those with more than one underlying health condition.

Adding up the 6% with no recovery after 18 months and 42% with partial recovery means that between 6 and 18 months following symptomatic coronavirus infection, almost half of those infected still experience persistent symptoms.

Vaccination validated

On the plus side, people vaccinated against COVID-19 before getting infected had a lower risk for some persistent symptoms. In addition, Dr. Pell and colleagues found no evidence that people who experienced asymptomatic infection were likely to experience long COVID symptoms or challenges with activities of daily living.

The findings of the Long-COVID in Scotland Study (Long-CISS) were published in the journal Nature Communications.

‘More long COVID than ever before’

“Unfortunately, these long COVID symptoms are not getting better as the cases of COVID get milder,” said Thomas Gut, DO, medical director for the post-COVID recovery program at Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital. “Quite the opposite – this infection has become so common in a community because it’s so mild and spreading so rapidly that we’re seeing more long COVID symptoms than ever before.”

Although most patients he sees with long COVID resolve their symptoms within 3-6 months, “We do see some patients who require short-term disability because their symptoms continue past 6 months and out to 2 years,” said Dr. Gut, a hospitalist at Staten Island University Hospital, a member hospital of Northwell Health.

Patients with fatigue and neurocognitive symptoms “have a very tough time going back to work. Short-term disability gives them the time and finances to pursue specialty care with cardiology, pulmonary, and neurocognitive testing,” he said.

Support the whole person

The burden of living with long COVID goes beyond the persistent symptoms. “Long COVID can have wide-ranging impacts – not only on health but also quality of life and activities of daily living [including] work, mobility, self-care and more,” Dr. Pell said. “So, people with long COVID need support relevant to their individual needs and this may extend beyond the health care sector, for example including social services, school or workplace.”

Still, Lisa Penziner, RN, founder of the COVID Long Haulers Support Group in Westchester and Long Island, N.Y., said while people with the most severe cases of COVID-19 tended to have the worst long COVID symptoms, they’re not the only ones.

“We saw many post-COVID members who had mild cases and their long-haul symptoms were worse weeks later than the virus itself,” said Md. Penziner.

She estimates that 80%-90% of her support group members recover within 6 months. “However, there are others who were experiencing symptoms for much longer.”

Respiratory treatment, physical therapy, and other follow-up doctor visits are common after 6 months, for example.

“Additionally, there is a mental health component to recovery as well, meaning that the patient must learn to live while experiencing lingering, long-haul COVID symptoms in work and daily life,” said Ms. Penziner, director of special projects at North Westchester Restorative Therapy & Nursing.

In addition to ongoing medical care, people with long COVID need understanding, she said.

“While long-haul symptoms do not happen to everyone, it is proven that many do experience long-haul symptoms, and the support of the community in understanding is important.”

Limitations of the study

Dr. Pell and colleagues noted some strengths and weaknesses to their study. For example, “as a general population study, our findings provide a better indication of the overall risk and burden of long COVID than hospitalized cohorts,” they noted.

Also, the Scottish population is 96% White, so other long COVID studies with more diverse participants are warranted.

Another potential weakness is the response rate of 16% among those invited to participate in the study, which Dr. Pell and colleagues addressed: “Our cohort included a large sample (33,281) of people previously infected and the response rate of 16% overall and 20% among people who had symptomatic infection was consistent with previous studies that have used SMS text invitations as the sole method of recruitment.”

“We tell patients this should last 3-6 months, but some patients have longer recovery periods,” Dr. Gut said. “We’re here for them. We have a lot of services available to help get them through the recovery process, and we have a lot of options to help support them.”

“What we found most helpful is when there is peer-to-peer support, reaffirming to the member that they are not alone in the long-haul battle, which has been a major benefit of the support group,” Ms. Penziner said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM NATURE COMMUNICATIONS

Keep menstrual cramps away the dietary prevention way

Foods for thought: Menstrual cramp prevention

For those who menstruate, it’s typical for that time of the month to bring cravings for things that may give a serotonin boost that eases the rise in stress hormones. Chocolate and other foods high in sugar fall into that category, but they could actually be adding to the problem.

About 90% of adolescent girls have menstrual pain, and it’s the leading cause of school absences for the demographic. Muscle relaxers and PMS pills are usually the recommended solution to alleviating menstrual cramps, but what if the patient doesn’t want to take any medicine?

Serah Sannoh of Rutgers University wanted to find another way to relieve her menstrual pains. The literature review she presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society found multiple studies that examined dietary patterns that resulted in menstrual pain.

In Ms. Sannoh’s analysis, she looked at how certain foods have an effect on cramps. Do they contribute to the pain or reduce it? Diets high in processed foods, oils, sugars, salt, and omega-6 fatty acids promote inflammation in the muscles around the uterus. Thus, cramps.

The answer, sometimes, is not to add a medicine but to change our daily practices, she suggested. Foods high in omega-3 fatty acids helped reduce pain, and those who practiced a vegan diet had the lowest muscle inflammation rates. So more salmon and fewer Swedish Fish.

Stage 1 of the robot apocalypse is already upon us

The mere mention of a robot apocalypse is enough to conjure images of terrifying robot soldiers with Austrian accents harvesting and killing humanity while the survivors live blissfully in a simulation and do low-gravity kung fu with high-profile Hollywood actors. They’ll even take over the navy.

Reality is often less exciting than the movies, but rest assured, the robots will not be denied their dominion of Earth. Our future robot overlords are simply taking a more subtle, less dramatic route toward their ultimate subjugation of mankind: They’re making us all sad and burned out.

The research pulls from work conducted in multiple countries to paint a picture of a humanity filled with anxiety about jobs as robotic automation grows more common. In India, a survey of automobile manufacturing works showed that working alongside industrial robots was linked with greater reports of burnout and workplace incivility. In Singapore, a group of college students randomly assigned to read one of three articles – one about the use of robots in business, a generic article about robots, or an article unrelated to robots – were then surveyed about their job security concerns. Three guesses as to which group was most worried.

In addition, the researchers analyzed 185 U.S. metropolitan areas for robot prevalence alongside use of job-recruiting websites and found that the more robots a city used, the more common job searches were. Unemployment rates weren’t affected, suggesting people had job insecurity because of robots. Sure, there could be other, nonrobotic reasons for this, but that’s no fun. We’re here because we fear our future android rulers.

It’s not all doom and gloom, fortunately. In an online experiment, the study authors found that self-affirmation exercises, such as writing down characteristics or values important to us, can overcome the existential fears and lessen concern about robots in the workplace. One of the authors noted that, while some fear is justified, “media reports on new technologies like robots and algorithms tend to be apocalyptic in nature, so people may develop an irrational fear about them.”

Oops. Our bad.

Apocalypse, stage 2: Leaping oral superorganisms

The terms of our secret agreement with the shadowy-but-powerful dental-industrial complex stipulate that LOTME can only cover tooth-related news once a year. This is that once a year.

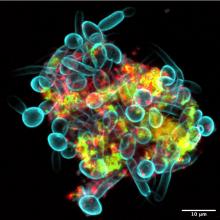

Since we’ve already dealt with a robot apocalypse, how about a sci-fi horror story? A story with a “cross-kingdom partnership” in which assemblages of bacteria and fungi perform feats greater than either could achieve on its own. A story in which new microscopy technologies allow “scientists to visualize the behavior of living microbes in real time,” according to a statement from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

While looking at saliva samples from toddlers with severe tooth decay, lead author Zhi Ren and associates “noticed the bacteria and fungi forming these assemblages and developing motions we never thought they would possess: a ‘walking-like’ and ‘leaping-like’ mobility. … It’s almost like a new organism – a superorganism – with new functions,” said senior author Hyun Koo, DDS, PhD, of Penn Dental Medicine.

Did he say “mobility”? He did, didn’t he?

To study these alleged superorganisms, they set up a laboratory system “using the bacteria, fungi, and a tooth-like material, all incubated in human saliva,” the university explained.

“Incubated in human saliva.” There’s a phrase you don’t see every day.

It only took a few hours for the investigators to observe the bacterial/fungal assemblages making leaps of more than 100 microns across the tooth-like material. “That is more than 200 times their own body length,” Dr. Ren said, “making them even better than most vertebrates, relative to body size. For example, tree frogs and grasshoppers can leap forward about 50 times and 20 times their own body length, respectively.”

So, will it be the robots or the evil superorganisms? Let us give you a word of advice: Always bet on bacteria.

Foods for thought: Menstrual cramp prevention

For those who menstruate, it’s typical for that time of the month to bring cravings for things that may give a serotonin boost that eases the rise in stress hormones. Chocolate and other foods high in sugar fall into that category, but they could actually be adding to the problem.

About 90% of adolescent girls have menstrual pain, and it’s the leading cause of school absences for the demographic. Muscle relaxers and PMS pills are usually the recommended solution to alleviating menstrual cramps, but what if the patient doesn’t want to take any medicine?

Serah Sannoh of Rutgers University wanted to find another way to relieve her menstrual pains. The literature review she presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society found multiple studies that examined dietary patterns that resulted in menstrual pain.

In Ms. Sannoh’s analysis, she looked at how certain foods have an effect on cramps. Do they contribute to the pain or reduce it? Diets high in processed foods, oils, sugars, salt, and omega-6 fatty acids promote inflammation in the muscles around the uterus. Thus, cramps.

The answer, sometimes, is not to add a medicine but to change our daily practices, she suggested. Foods high in omega-3 fatty acids helped reduce pain, and those who practiced a vegan diet had the lowest muscle inflammation rates. So more salmon and fewer Swedish Fish.

Stage 1 of the robot apocalypse is already upon us

The mere mention of a robot apocalypse is enough to conjure images of terrifying robot soldiers with Austrian accents harvesting and killing humanity while the survivors live blissfully in a simulation and do low-gravity kung fu with high-profile Hollywood actors. They’ll even take over the navy.

Reality is often less exciting than the movies, but rest assured, the robots will not be denied their dominion of Earth. Our future robot overlords are simply taking a more subtle, less dramatic route toward their ultimate subjugation of mankind: They’re making us all sad and burned out.

The research pulls from work conducted in multiple countries to paint a picture of a humanity filled with anxiety about jobs as robotic automation grows more common. In India, a survey of automobile manufacturing works showed that working alongside industrial robots was linked with greater reports of burnout and workplace incivility. In Singapore, a group of college students randomly assigned to read one of three articles – one about the use of robots in business, a generic article about robots, or an article unrelated to robots – were then surveyed about their job security concerns. Three guesses as to which group was most worried.

In addition, the researchers analyzed 185 U.S. metropolitan areas for robot prevalence alongside use of job-recruiting websites and found that the more robots a city used, the more common job searches were. Unemployment rates weren’t affected, suggesting people had job insecurity because of robots. Sure, there could be other, nonrobotic reasons for this, but that’s no fun. We’re here because we fear our future android rulers.

It’s not all doom and gloom, fortunately. In an online experiment, the study authors found that self-affirmation exercises, such as writing down characteristics or values important to us, can overcome the existential fears and lessen concern about robots in the workplace. One of the authors noted that, while some fear is justified, “media reports on new technologies like robots and algorithms tend to be apocalyptic in nature, so people may develop an irrational fear about them.”

Oops. Our bad.

Apocalypse, stage 2: Leaping oral superorganisms

The terms of our secret agreement with the shadowy-but-powerful dental-industrial complex stipulate that LOTME can only cover tooth-related news once a year. This is that once a year.

Since we’ve already dealt with a robot apocalypse, how about a sci-fi horror story? A story with a “cross-kingdom partnership” in which assemblages of bacteria and fungi perform feats greater than either could achieve on its own. A story in which new microscopy technologies allow “scientists to visualize the behavior of living microbes in real time,” according to a statement from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

While looking at saliva samples from toddlers with severe tooth decay, lead author Zhi Ren and associates “noticed the bacteria and fungi forming these assemblages and developing motions we never thought they would possess: a ‘walking-like’ and ‘leaping-like’ mobility. … It’s almost like a new organism – a superorganism – with new functions,” said senior author Hyun Koo, DDS, PhD, of Penn Dental Medicine.

Did he say “mobility”? He did, didn’t he?

To study these alleged superorganisms, they set up a laboratory system “using the bacteria, fungi, and a tooth-like material, all incubated in human saliva,” the university explained.

“Incubated in human saliva.” There’s a phrase you don’t see every day.

It only took a few hours for the investigators to observe the bacterial/fungal assemblages making leaps of more than 100 microns across the tooth-like material. “That is more than 200 times their own body length,” Dr. Ren said, “making them even better than most vertebrates, relative to body size. For example, tree frogs and grasshoppers can leap forward about 50 times and 20 times their own body length, respectively.”

So, will it be the robots or the evil superorganisms? Let us give you a word of advice: Always bet on bacteria.

Foods for thought: Menstrual cramp prevention

For those who menstruate, it’s typical for that time of the month to bring cravings for things that may give a serotonin boost that eases the rise in stress hormones. Chocolate and other foods high in sugar fall into that category, but they could actually be adding to the problem.

About 90% of adolescent girls have menstrual pain, and it’s the leading cause of school absences for the demographic. Muscle relaxers and PMS pills are usually the recommended solution to alleviating menstrual cramps, but what if the patient doesn’t want to take any medicine?

Serah Sannoh of Rutgers University wanted to find another way to relieve her menstrual pains. The literature review she presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society found multiple studies that examined dietary patterns that resulted in menstrual pain.

In Ms. Sannoh’s analysis, she looked at how certain foods have an effect on cramps. Do they contribute to the pain or reduce it? Diets high in processed foods, oils, sugars, salt, and omega-6 fatty acids promote inflammation in the muscles around the uterus. Thus, cramps.

The answer, sometimes, is not to add a medicine but to change our daily practices, she suggested. Foods high in omega-3 fatty acids helped reduce pain, and those who practiced a vegan diet had the lowest muscle inflammation rates. So more salmon and fewer Swedish Fish.

Stage 1 of the robot apocalypse is already upon us

The mere mention of a robot apocalypse is enough to conjure images of terrifying robot soldiers with Austrian accents harvesting and killing humanity while the survivors live blissfully in a simulation and do low-gravity kung fu with high-profile Hollywood actors. They’ll even take over the navy.

Reality is often less exciting than the movies, but rest assured, the robots will not be denied their dominion of Earth. Our future robot overlords are simply taking a more subtle, less dramatic route toward their ultimate subjugation of mankind: They’re making us all sad and burned out.

The research pulls from work conducted in multiple countries to paint a picture of a humanity filled with anxiety about jobs as robotic automation grows more common. In India, a survey of automobile manufacturing works showed that working alongside industrial robots was linked with greater reports of burnout and workplace incivility. In Singapore, a group of college students randomly assigned to read one of three articles – one about the use of robots in business, a generic article about robots, or an article unrelated to robots – were then surveyed about their job security concerns. Three guesses as to which group was most worried.

In addition, the researchers analyzed 185 U.S. metropolitan areas for robot prevalence alongside use of job-recruiting websites and found that the more robots a city used, the more common job searches were. Unemployment rates weren’t affected, suggesting people had job insecurity because of robots. Sure, there could be other, nonrobotic reasons for this, but that’s no fun. We’re here because we fear our future android rulers.

It’s not all doom and gloom, fortunately. In an online experiment, the study authors found that self-affirmation exercises, such as writing down characteristics or values important to us, can overcome the existential fears and lessen concern about robots in the workplace. One of the authors noted that, while some fear is justified, “media reports on new technologies like robots and algorithms tend to be apocalyptic in nature, so people may develop an irrational fear about them.”

Oops. Our bad.

Apocalypse, stage 2: Leaping oral superorganisms

The terms of our secret agreement with the shadowy-but-powerful dental-industrial complex stipulate that LOTME can only cover tooth-related news once a year. This is that once a year.

Since we’ve already dealt with a robot apocalypse, how about a sci-fi horror story? A story with a “cross-kingdom partnership” in which assemblages of bacteria and fungi perform feats greater than either could achieve on its own. A story in which new microscopy technologies allow “scientists to visualize the behavior of living microbes in real time,” according to a statement from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

While looking at saliva samples from toddlers with severe tooth decay, lead author Zhi Ren and associates “noticed the bacteria and fungi forming these assemblages and developing motions we never thought they would possess: a ‘walking-like’ and ‘leaping-like’ mobility. … It’s almost like a new organism – a superorganism – with new functions,” said senior author Hyun Koo, DDS, PhD, of Penn Dental Medicine.

Did he say “mobility”? He did, didn’t he?

To study these alleged superorganisms, they set up a laboratory system “using the bacteria, fungi, and a tooth-like material, all incubated in human saliva,” the university explained.

“Incubated in human saliva.” There’s a phrase you don’t see every day.

It only took a few hours for the investigators to observe the bacterial/fungal assemblages making leaps of more than 100 microns across the tooth-like material. “That is more than 200 times their own body length,” Dr. Ren said, “making them even better than most vertebrates, relative to body size. For example, tree frogs and grasshoppers can leap forward about 50 times and 20 times their own body length, respectively.”

So, will it be the robots or the evil superorganisms? Let us give you a word of advice: Always bet on bacteria.

Pediatricians urged to check for vision problems after concussion

Pediatricians should consider screening children suspected of having a concussion for resulting vision problems that are often overlooked, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Christina Master, MD, a pediatrician and sports medicine specialist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said many doctors don’t think of vision problems when examining children who’ve experienced a head injury. But the issues are common and can significantly affect a child’s performance in school and sports, and disrupt daily life.

Dr. Master led a team of sports medicine and vision specialists who wrote an AAP policy statement on vision and concussion. She summarized the new recommendations during a plenary session Oct. 9 at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

Dr. Master told this news organization that the vast majority of the estimated 1.4 million U.S. children and adolescents who have concussions annually are treated in pediatricians’ offices.

Up to 40% of young patients experience symptoms such as blurred vision, light sensitivity, and double vision following a concussion, the panel said. In addition, children with vision problems are more likely to have prolonged recoveries and delays in returning to school than children who have concussions but don’t have similar eyesight issues.

Concussions affect neurologic pathways of the visual system and disturb basic functions such as the ability of the eyes to change focus from a distant object to a near one.

Dr. Master said most pediatricians do not routinely check for vision problems following a concussion, and children themselves may not recognize that they have vision deficits “unless you ask them very specifically.”

In addition to asking children about their vision, the policy statement recommends pediatricians conduct a thorough exam to assess ocular alignment, the ability to track a moving object, and the ability to maintain focus on an image while moving.

Dr. Master said that an assessment of vision and balance, which is described in an accompanying clinical report, lasts about 5 minutes and is easy for pediatricians to learn.

Managing vision problems

Pediatricians can guide parents in talking to their child’s school about accommodations such as extra time on classroom tasks, creating materials with enlarged fonts, and using preprinted or audio notes, the statement said.

At school, vision deficits can interfere with reading by causing children to skip words, lose their place, become fatigued, or lose interest, according to the statement.

Children can also take breaks from visual stressors such as bright lights and screens, and use prescription glasses temporarily to correct blurred vision, the panel noted.

Although most children will recover from a concussion on their own within 4 weeks, up to one-third will have persistent symptoms and may benefit from seeing a specialist who can provide treatment such as rehabilitative exercises. While evidence suggests that referring some children to specialty care within a week of a concussion improves outcomes, the signs of who would benefit are not always clear, according to the panel.

Specialties such as sports medicine, neurology, physiatry, otorhinolaryngology, and occupational therapy may provide care for prolonged symptoms, Dr. Master said.

The panel noted that more study is needed on treatment options such as rehabilitation exercises, which have been shown to help with balance and dizziness.

Dr. Master said the panel did not recommend that pediatricians provide a home exercise program to treat concussion, as she does in her practice, explaining that “it’s not clear that it’s necessary for all kids.”

One author of the policy statement, Ankoor Shah, MD, PhD, reported an intellectual property relationship with Rebion involving a patent application for a pediatric vision screener. Others, including Dr. Master, reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatricians should consider screening children suspected of having a concussion for resulting vision problems that are often overlooked, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Christina Master, MD, a pediatrician and sports medicine specialist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said many doctors don’t think of vision problems when examining children who’ve experienced a head injury. But the issues are common and can significantly affect a child’s performance in school and sports, and disrupt daily life.

Dr. Master led a team of sports medicine and vision specialists who wrote an AAP policy statement on vision and concussion. She summarized the new recommendations during a plenary session Oct. 9 at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

Dr. Master told this news organization that the vast majority of the estimated 1.4 million U.S. children and adolescents who have concussions annually are treated in pediatricians’ offices.

Up to 40% of young patients experience symptoms such as blurred vision, light sensitivity, and double vision following a concussion, the panel said. In addition, children with vision problems are more likely to have prolonged recoveries and delays in returning to school than children who have concussions but don’t have similar eyesight issues.

Concussions affect neurologic pathways of the visual system and disturb basic functions such as the ability of the eyes to change focus from a distant object to a near one.

Dr. Master said most pediatricians do not routinely check for vision problems following a concussion, and children themselves may not recognize that they have vision deficits “unless you ask them very specifically.”

In addition to asking children about their vision, the policy statement recommends pediatricians conduct a thorough exam to assess ocular alignment, the ability to track a moving object, and the ability to maintain focus on an image while moving.

Dr. Master said that an assessment of vision and balance, which is described in an accompanying clinical report, lasts about 5 minutes and is easy for pediatricians to learn.

Managing vision problems

Pediatricians can guide parents in talking to their child’s school about accommodations such as extra time on classroom tasks, creating materials with enlarged fonts, and using preprinted or audio notes, the statement said.

At school, vision deficits can interfere with reading by causing children to skip words, lose their place, become fatigued, or lose interest, according to the statement.

Children can also take breaks from visual stressors such as bright lights and screens, and use prescription glasses temporarily to correct blurred vision, the panel noted.

Although most children will recover from a concussion on their own within 4 weeks, up to one-third will have persistent symptoms and may benefit from seeing a specialist who can provide treatment such as rehabilitative exercises. While evidence suggests that referring some children to specialty care within a week of a concussion improves outcomes, the signs of who would benefit are not always clear, according to the panel.

Specialties such as sports medicine, neurology, physiatry, otorhinolaryngology, and occupational therapy may provide care for prolonged symptoms, Dr. Master said.

The panel noted that more study is needed on treatment options such as rehabilitation exercises, which have been shown to help with balance and dizziness.

Dr. Master said the panel did not recommend that pediatricians provide a home exercise program to treat concussion, as she does in her practice, explaining that “it’s not clear that it’s necessary for all kids.”

One author of the policy statement, Ankoor Shah, MD, PhD, reported an intellectual property relationship with Rebion involving a patent application for a pediatric vision screener. Others, including Dr. Master, reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatricians should consider screening children suspected of having a concussion for resulting vision problems that are often overlooked, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Christina Master, MD, a pediatrician and sports medicine specialist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said many doctors don’t think of vision problems when examining children who’ve experienced a head injury. But the issues are common and can significantly affect a child’s performance in school and sports, and disrupt daily life.

Dr. Master led a team of sports medicine and vision specialists who wrote an AAP policy statement on vision and concussion. She summarized the new recommendations during a plenary session Oct. 9 at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

Dr. Master told this news organization that the vast majority of the estimated 1.4 million U.S. children and adolescents who have concussions annually are treated in pediatricians’ offices.

Up to 40% of young patients experience symptoms such as blurred vision, light sensitivity, and double vision following a concussion, the panel said. In addition, children with vision problems are more likely to have prolonged recoveries and delays in returning to school than children who have concussions but don’t have similar eyesight issues.

Concussions affect neurologic pathways of the visual system and disturb basic functions such as the ability of the eyes to change focus from a distant object to a near one.

Dr. Master said most pediatricians do not routinely check for vision problems following a concussion, and children themselves may not recognize that they have vision deficits “unless you ask them very specifically.”

In addition to asking children about their vision, the policy statement recommends pediatricians conduct a thorough exam to assess ocular alignment, the ability to track a moving object, and the ability to maintain focus on an image while moving.

Dr. Master said that an assessment of vision and balance, which is described in an accompanying clinical report, lasts about 5 minutes and is easy for pediatricians to learn.

Managing vision problems

Pediatricians can guide parents in talking to their child’s school about accommodations such as extra time on classroom tasks, creating materials with enlarged fonts, and using preprinted or audio notes, the statement said.

At school, vision deficits can interfere with reading by causing children to skip words, lose their place, become fatigued, or lose interest, according to the statement.

Children can also take breaks from visual stressors such as bright lights and screens, and use prescription glasses temporarily to correct blurred vision, the panel noted.

Although most children will recover from a concussion on their own within 4 weeks, up to one-third will have persistent symptoms and may benefit from seeing a specialist who can provide treatment such as rehabilitative exercises. While evidence suggests that referring some children to specialty care within a week of a concussion improves outcomes, the signs of who would benefit are not always clear, according to the panel.

Specialties such as sports medicine, neurology, physiatry, otorhinolaryngology, and occupational therapy may provide care for prolonged symptoms, Dr. Master said.

The panel noted that more study is needed on treatment options such as rehabilitation exercises, which have been shown to help with balance and dizziness.

Dr. Master said the panel did not recommend that pediatricians provide a home exercise program to treat concussion, as she does in her practice, explaining that “it’s not clear that it’s necessary for all kids.”

One author of the policy statement, Ankoor Shah, MD, PhD, reported an intellectual property relationship with Rebion involving a patent application for a pediatric vision screener. Others, including Dr. Master, reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAP 2022

63% of long COVID patients are women, study says

according to a new study published in JAMA.

The global study also found that about 6% of people with symptomatic infections had long COVID in 2020 and 2021. The risk for long COVID seemed to be greater among those who needed hospitalization, especially those who needed intensive care.

“Quantifying the number of individuals with long COVID may help policy makers ensure adequate access to services to guide people toward recovery, return to the workplace or school, and restore their mental health and social life,” the researchers wrote.

The study team, which included dozens of researchers across nearly every continent, analyzed data from 54 studies and two databases for more than 1 million patients in 22 countries who had symptomatic COVID infections in 2020 and 2021. They looked at three long COVID symptom types: persistent fatigue with bodily pain or mood swings, ongoing respiratory problems, and cognitive issues. The study included people aged 4-66.

Overall, 6.2% of people reported one of the long COVID symptom types, including 3.7% with ongoing respiratory problems, 3.2% with persistent fatigue and bodily pain or mood swings, and 2.2% with cognitive problems. Among those with long COVID, 38% of people reported more than one symptom cluster.

At 3 months after infection, long COVID symptoms were nearly twice as common in women who were at least 20 years old at 10.6%, compared with men who were at least 20 years old at 5.4%.

Children and teens appeared to have lower risks of long COVID. About 2.8% of patients under age 20 with symptomatic infection developed long-term issues.

The estimated average duration of long COVID symptoms was 9 months among hospitalized patients and 4 months among those who weren’t hospitalized. About 15% of people with long COVID symptoms 3 months after the initial infection continued to have symptoms at 12 months.

The study was largely based on detailed data from ongoing COVID-19 studies in the United States, Austria, the Faroe Islands, Germany, Iran, Italy, the Netherlands, Russia, Sweden, and Switzerland, according to UPI. It was supplemented by published data and research conducted as part of the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study. The dozens of researchers are referred to as “Global Burden of Disease Long COVID Collaborators.”

The study had limitations, the researchers said, including the assumption that long COVID follows a similar course in all countries. Additional studies may show how long COVID symptoms and severity may vary in different countries and continents.

Ultimately, ongoing studies of large numbers of people with long COVID could help scientists and public health officials understand risk factors and ways to treat the debilitating condition, the study authors wrote, noting that “postinfection fatigue syndrome” has been reported before, namely during the 1918 flu pandemic, after the SARS outbreak in 2003, and after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014.

“Similar symptoms have been reported after other viral infections, including the Epstein-Barr virus, mononucleosis, and dengue, as well as after nonviral infections such as Q fever, Lyme disease and giardiasis,” they wrote.

Several study investigators reported receiving grants and personal fees from a variety of sources.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new study published in JAMA.

The global study also found that about 6% of people with symptomatic infections had long COVID in 2020 and 2021. The risk for long COVID seemed to be greater among those who needed hospitalization, especially those who needed intensive care.

“Quantifying the number of individuals with long COVID may help policy makers ensure adequate access to services to guide people toward recovery, return to the workplace or school, and restore their mental health and social life,” the researchers wrote.

The study team, which included dozens of researchers across nearly every continent, analyzed data from 54 studies and two databases for more than 1 million patients in 22 countries who had symptomatic COVID infections in 2020 and 2021. They looked at three long COVID symptom types: persistent fatigue with bodily pain or mood swings, ongoing respiratory problems, and cognitive issues. The study included people aged 4-66.

Overall, 6.2% of people reported one of the long COVID symptom types, including 3.7% with ongoing respiratory problems, 3.2% with persistent fatigue and bodily pain or mood swings, and 2.2% with cognitive problems. Among those with long COVID, 38% of people reported more than one symptom cluster.

At 3 months after infection, long COVID symptoms were nearly twice as common in women who were at least 20 years old at 10.6%, compared with men who were at least 20 years old at 5.4%.

Children and teens appeared to have lower risks of long COVID. About 2.8% of patients under age 20 with symptomatic infection developed long-term issues.

The estimated average duration of long COVID symptoms was 9 months among hospitalized patients and 4 months among those who weren’t hospitalized. About 15% of people with long COVID symptoms 3 months after the initial infection continued to have symptoms at 12 months.

The study was largely based on detailed data from ongoing COVID-19 studies in the United States, Austria, the Faroe Islands, Germany, Iran, Italy, the Netherlands, Russia, Sweden, and Switzerland, according to UPI. It was supplemented by published data and research conducted as part of the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study. The dozens of researchers are referred to as “Global Burden of Disease Long COVID Collaborators.”

The study had limitations, the researchers said, including the assumption that long COVID follows a similar course in all countries. Additional studies may show how long COVID symptoms and severity may vary in different countries and continents.

Ultimately, ongoing studies of large numbers of people with long COVID could help scientists and public health officials understand risk factors and ways to treat the debilitating condition, the study authors wrote, noting that “postinfection fatigue syndrome” has been reported before, namely during the 1918 flu pandemic, after the SARS outbreak in 2003, and after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014.

“Similar symptoms have been reported after other viral infections, including the Epstein-Barr virus, mononucleosis, and dengue, as well as after nonviral infections such as Q fever, Lyme disease and giardiasis,” they wrote.

Several study investigators reported receiving grants and personal fees from a variety of sources.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new study published in JAMA.

The global study also found that about 6% of people with symptomatic infections had long COVID in 2020 and 2021. The risk for long COVID seemed to be greater among those who needed hospitalization, especially those who needed intensive care.

“Quantifying the number of individuals with long COVID may help policy makers ensure adequate access to services to guide people toward recovery, return to the workplace or school, and restore their mental health and social life,” the researchers wrote.

The study team, which included dozens of researchers across nearly every continent, analyzed data from 54 studies and two databases for more than 1 million patients in 22 countries who had symptomatic COVID infections in 2020 and 2021. They looked at three long COVID symptom types: persistent fatigue with bodily pain or mood swings, ongoing respiratory problems, and cognitive issues. The study included people aged 4-66.

Overall, 6.2% of people reported one of the long COVID symptom types, including 3.7% with ongoing respiratory problems, 3.2% with persistent fatigue and bodily pain or mood swings, and 2.2% with cognitive problems. Among those with long COVID, 38% of people reported more than one symptom cluster.

At 3 months after infection, long COVID symptoms were nearly twice as common in women who were at least 20 years old at 10.6%, compared with men who were at least 20 years old at 5.4%.

Children and teens appeared to have lower risks of long COVID. About 2.8% of patients under age 20 with symptomatic infection developed long-term issues.

The estimated average duration of long COVID symptoms was 9 months among hospitalized patients and 4 months among those who weren’t hospitalized. About 15% of people with long COVID symptoms 3 months after the initial infection continued to have symptoms at 12 months.

The study was largely based on detailed data from ongoing COVID-19 studies in the United States, Austria, the Faroe Islands, Germany, Iran, Italy, the Netherlands, Russia, Sweden, and Switzerland, according to UPI. It was supplemented by published data and research conducted as part of the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study. The dozens of researchers are referred to as “Global Burden of Disease Long COVID Collaborators.”

The study had limitations, the researchers said, including the assumption that long COVID follows a similar course in all countries. Additional studies may show how long COVID symptoms and severity may vary in different countries and continents.

Ultimately, ongoing studies of large numbers of people with long COVID could help scientists and public health officials understand risk factors and ways to treat the debilitating condition, the study authors wrote, noting that “postinfection fatigue syndrome” has been reported before, namely during the 1918 flu pandemic, after the SARS outbreak in 2003, and after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014.

“Similar symptoms have been reported after other viral infections, including the Epstein-Barr virus, mononucleosis, and dengue, as well as after nonviral infections such as Q fever, Lyme disease and giardiasis,” they wrote.

Several study investigators reported receiving grants and personal fees from a variety of sources.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

Epidemic of brain fog? Long COVID’s effects worry experts

Weeks after Jeannie Volpe caught COVID-19 in November 2020, she could no longer do her job running sexual assault support groups in Anniston, Ala., because she kept forgetting the details that survivors had shared with her. “People were telling me they were having to revisit their traumatic memories, which isn’t fair to anybody,” the 47-year-old says.

Ms. Volpe has been diagnosed with long-COVID autonomic dysfunction, which includes severe muscle pain, depression, anxiety, and a loss of thinking skills. Some of her symptoms are more commonly known as brain fog, and they’re among the most frequent problems reported by people who have long-term issues after a bout of COVID-19.

Many experts and medical professionals say they haven’t even begun to scratch the surface of what impact this will have in years to come.

“I’m very worried that we have an epidemic of neurologic dysfunction coming down the pike,” says Pamela Davis, MD, PhD, a research professor at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

In the 2 years Ms. Volpe has been living with long COVID, her executive function – the mental processes that enable people to focus attention, retain information, and multitask – has been so diminished that she had to relearn to drive. One of the various doctors assessing her has suggested speech therapy to help Ms. Volpe relearn how to form words. “I can see the words I want to say in my mind, but I can’t make them come out of my mouth,” she says in a sluggish voice that gives away her condition.

All of those symptoms make it difficult for her to care for herself. Without a job and health insurance, Ms. Volpe says she’s researched assisted suicide in the states that allow it but has ultimately decided she wants to live.

“People tell you things like you should be grateful you survived it, and you should; but you shouldn’t expect somebody to not grieve after losing their autonomy, their career, their finances.”

The findings of researchers studying the brain effects of COVID-19 reinforce what people with long COVID have been dealing with from the start. Their experiences aren’t imaginary; they’re consistent with neurological disorders – including myalgic encephalomyelitis, also known as chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME/CFS – which carry much more weight in the public imagination than the term brain fog, which can often be used dismissively.

Studies have found that COVID-19 is linked to conditions such as strokes; seizures; and mood, memory, and movement disorders.

While there are still a lot of unanswered questions about exactly how COVID-19 affects the brain and what the long-term effects are, there’s enough reason to suggest people should be trying to avoid both infection and reinfection until researchers get more answers.

Worldwide, it’s estimated that COVID-19 has contributed to more than 40 million new cases of neurological disorders, says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, a clinical epidemiologist and long COVID researcher at Washington University in St. Louis. In his latest study of 14 million medical records of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the country’s largest integrated health care system, researchers found that regardless of age, gender, race, and lifestyle,

He noted that some of the conditions, such as headaches and mild decline in memory and sharpness, may improve and go away over time. But others that showed up, such as stroke, encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), and Guillain-Barré syndrome (a rare disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks the nerves), often lead to lasting damage. Dr. Al-Aly’s team found that neurological conditions were 7% more likely in those who had COVID-19 than in those who had never been infected.

What’s more, researchers noticed that compared with control groups, the risk of post-COVID thinking problems was more pronounced in people in their 30s, 40s, and 50s – a group that usually would be very unlikely to have these problems. For those over the age of 60, the risks stood out less because at that stage of life, such thinking problems aren’t as rare.

Another study of the veterans system last year showed that COVID-19 survivors were at a 46% higher risk of considering suicide after 1 year.

“We need to be paying attention to this,” says Dr. Al-Aly. “What we’ve seen is really the tip of the iceberg.” He worries that millions of people, including youths, will lose out on employment and education while dealing with long-term disabilities – and the economic and societal implications of such a fallout. “What we will all be left with is the aftermath of sheer devastation in some people’s lives,” he says.

Igor Koralnik, MD, chief of neuro-infectious disease and global neurology at Northwestern University, Chicago, has been running a specialized long COVID clinic. His team published a paper in March 2021 detailing what they saw in their first 100 patients. “About half the population in the study missed at least 10 days of work. This is going to have persistent impact on the workforce,” Dr. Koralnik said in a podcast posted on the Northwestern website. “We have seen that not only [do] patients have symptoms, but they have decreased quality of life.”

For older people and their caregivers, the risk of potential neurodegenerative diseases that the virus has shown to accelerate, such as dementia, is also a big concern. Alzheimer’s is already the fifth leading cause of death for people 65 and older.

In a recent study of more than 6 million people over the age of 65, Dr. Davis and her team at Case Western found the risk of Alzheimer’s in the year after COVID-19 increased by 50%-80%. The chances were especially high for women older than 85.

To date, there are no good treatments for Alzheimer’s, yet total health care costs for long-term care and hospice services for people with dementia topped $300 billion in 2020. That doesn’t even include the related costs to families.

“The downstream effect of having someone with Alzheimer’s being taken care of by a family member can be devastating on everyone,” she says. “Sometimes the caregivers don’t weather that very well.”

When Dr. Davis’s own father got Alzheimer’s at age 86, her mother took care of him until she had a stroke one morning while making breakfast. Dr. Davis attributes the stroke to the stress of caregiving. That left Dr. Davis no choice but to seek housing where both her parents could get care.

Looking at the broader picture, Dr. Davis believes widespread isolation, loneliness, and grief during the pandemic, and the disease of COVID-19 itself, will continue to have a profound impact on psychiatric diagnoses. This in turn could trigger a wave of new substance abuse as a result of unchecked mental health problems.

Still, not all brain experts are jumping to worst-case scenarios, with a lot yet to be understood before sounding the alarm. Joanna Hellmuth, MD, a neurologist and researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, cautions against reading too much into early data, including any assumptions that COVID-19 causes neurodegeneration or irreversible damage in the brain.

Even with before-and-after brain scans by University of Oxford, England, researchers that show structural changes to the brain after infection, she points out that they didn’t actually study the clinical symptoms of the people in the study, so it’s too soon to reach conclusions about associated cognitive problems.

“It’s an important piece of the puzzle, but we don’t know how that fits together with everything else,” says Dr. Hellmuth. “Some of my patients get better. … I haven’t seen a single person get worse since the pandemic started, and so I’m hopeful.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Weeks after Jeannie Volpe caught COVID-19 in November 2020, she could no longer do her job running sexual assault support groups in Anniston, Ala., because she kept forgetting the details that survivors had shared with her. “People were telling me they were having to revisit their traumatic memories, which isn’t fair to anybody,” the 47-year-old says.

Ms. Volpe has been diagnosed with long-COVID autonomic dysfunction, which includes severe muscle pain, depression, anxiety, and a loss of thinking skills. Some of her symptoms are more commonly known as brain fog, and they’re among the most frequent problems reported by people who have long-term issues after a bout of COVID-19.

Many experts and medical professionals say they haven’t even begun to scratch the surface of what impact this will have in years to come.

“I’m very worried that we have an epidemic of neurologic dysfunction coming down the pike,” says Pamela Davis, MD, PhD, a research professor at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

In the 2 years Ms. Volpe has been living with long COVID, her executive function – the mental processes that enable people to focus attention, retain information, and multitask – has been so diminished that she had to relearn to drive. One of the various doctors assessing her has suggested speech therapy to help Ms. Volpe relearn how to form words. “I can see the words I want to say in my mind, but I can’t make them come out of my mouth,” she says in a sluggish voice that gives away her condition.

All of those symptoms make it difficult for her to care for herself. Without a job and health insurance, Ms. Volpe says she’s researched assisted suicide in the states that allow it but has ultimately decided she wants to live.

“People tell you things like you should be grateful you survived it, and you should; but you shouldn’t expect somebody to not grieve after losing their autonomy, their career, their finances.”

The findings of researchers studying the brain effects of COVID-19 reinforce what people with long COVID have been dealing with from the start. Their experiences aren’t imaginary; they’re consistent with neurological disorders – including myalgic encephalomyelitis, also known as chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME/CFS – which carry much more weight in the public imagination than the term brain fog, which can often be used dismissively.

Studies have found that COVID-19 is linked to conditions such as strokes; seizures; and mood, memory, and movement disorders.

While there are still a lot of unanswered questions about exactly how COVID-19 affects the brain and what the long-term effects are, there’s enough reason to suggest people should be trying to avoid both infection and reinfection until researchers get more answers.

Worldwide, it’s estimated that COVID-19 has contributed to more than 40 million new cases of neurological disorders, says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, a clinical epidemiologist and long COVID researcher at Washington University in St. Louis. In his latest study of 14 million medical records of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the country’s largest integrated health care system, researchers found that regardless of age, gender, race, and lifestyle,

He noted that some of the conditions, such as headaches and mild decline in memory and sharpness, may improve and go away over time. But others that showed up, such as stroke, encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), and Guillain-Barré syndrome (a rare disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks the nerves), often lead to lasting damage. Dr. Al-Aly’s team found that neurological conditions were 7% more likely in those who had COVID-19 than in those who had never been infected.

What’s more, researchers noticed that compared with control groups, the risk of post-COVID thinking problems was more pronounced in people in their 30s, 40s, and 50s – a group that usually would be very unlikely to have these problems. For those over the age of 60, the risks stood out less because at that stage of life, such thinking problems aren’t as rare.

Another study of the veterans system last year showed that COVID-19 survivors were at a 46% higher risk of considering suicide after 1 year.

“We need to be paying attention to this,” says Dr. Al-Aly. “What we’ve seen is really the tip of the iceberg.” He worries that millions of people, including youths, will lose out on employment and education while dealing with long-term disabilities – and the economic and societal implications of such a fallout. “What we will all be left with is the aftermath of sheer devastation in some people’s lives,” he says.

Igor Koralnik, MD, chief of neuro-infectious disease and global neurology at Northwestern University, Chicago, has been running a specialized long COVID clinic. His team published a paper in March 2021 detailing what they saw in their first 100 patients. “About half the population in the study missed at least 10 days of work. This is going to have persistent impact on the workforce,” Dr. Koralnik said in a podcast posted on the Northwestern website. “We have seen that not only [do] patients have symptoms, but they have decreased quality of life.”

For older people and their caregivers, the risk of potential neurodegenerative diseases that the virus has shown to accelerate, such as dementia, is also a big concern. Alzheimer’s is already the fifth leading cause of death for people 65 and older.

In a recent study of more than 6 million people over the age of 65, Dr. Davis and her team at Case Western found the risk of Alzheimer’s in the year after COVID-19 increased by 50%-80%. The chances were especially high for women older than 85.

To date, there are no good treatments for Alzheimer’s, yet total health care costs for long-term care and hospice services for people with dementia topped $300 billion in 2020. That doesn’t even include the related costs to families.

“The downstream effect of having someone with Alzheimer’s being taken care of by a family member can be devastating on everyone,” she says. “Sometimes the caregivers don’t weather that very well.”

When Dr. Davis’s own father got Alzheimer’s at age 86, her mother took care of him until she had a stroke one morning while making breakfast. Dr. Davis attributes the stroke to the stress of caregiving. That left Dr. Davis no choice but to seek housing where both her parents could get care.

Looking at the broader picture, Dr. Davis believes widespread isolation, loneliness, and grief during the pandemic, and the disease of COVID-19 itself, will continue to have a profound impact on psychiatric diagnoses. This in turn could trigger a wave of new substance abuse as a result of unchecked mental health problems.

Still, not all brain experts are jumping to worst-case scenarios, with a lot yet to be understood before sounding the alarm. Joanna Hellmuth, MD, a neurologist and researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, cautions against reading too much into early data, including any assumptions that COVID-19 causes neurodegeneration or irreversible damage in the brain.

Even with before-and-after brain scans by University of Oxford, England, researchers that show structural changes to the brain after infection, she points out that they didn’t actually study the clinical symptoms of the people in the study, so it’s too soon to reach conclusions about associated cognitive problems.

“It’s an important piece of the puzzle, but we don’t know how that fits together with everything else,” says Dr. Hellmuth. “Some of my patients get better. … I haven’t seen a single person get worse since the pandemic started, and so I’m hopeful.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Weeks after Jeannie Volpe caught COVID-19 in November 2020, she could no longer do her job running sexual assault support groups in Anniston, Ala., because she kept forgetting the details that survivors had shared with her. “People were telling me they were having to revisit their traumatic memories, which isn’t fair to anybody,” the 47-year-old says.

Ms. Volpe has been diagnosed with long-COVID autonomic dysfunction, which includes severe muscle pain, depression, anxiety, and a loss of thinking skills. Some of her symptoms are more commonly known as brain fog, and they’re among the most frequent problems reported by people who have long-term issues after a bout of COVID-19.

Many experts and medical professionals say they haven’t even begun to scratch the surface of what impact this will have in years to come.

“I’m very worried that we have an epidemic of neurologic dysfunction coming down the pike,” says Pamela Davis, MD, PhD, a research professor at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

In the 2 years Ms. Volpe has been living with long COVID, her executive function – the mental processes that enable people to focus attention, retain information, and multitask – has been so diminished that she had to relearn to drive. One of the various doctors assessing her has suggested speech therapy to help Ms. Volpe relearn how to form words. “I can see the words I want to say in my mind, but I can’t make them come out of my mouth,” she says in a sluggish voice that gives away her condition.

All of those symptoms make it difficult for her to care for herself. Without a job and health insurance, Ms. Volpe says she’s researched assisted suicide in the states that allow it but has ultimately decided she wants to live.

“People tell you things like you should be grateful you survived it, and you should; but you shouldn’t expect somebody to not grieve after losing their autonomy, their career, their finances.”

The findings of researchers studying the brain effects of COVID-19 reinforce what people with long COVID have been dealing with from the start. Their experiences aren’t imaginary; they’re consistent with neurological disorders – including myalgic encephalomyelitis, also known as chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME/CFS – which carry much more weight in the public imagination than the term brain fog, which can often be used dismissively.

Studies have found that COVID-19 is linked to conditions such as strokes; seizures; and mood, memory, and movement disorders.

While there are still a lot of unanswered questions about exactly how COVID-19 affects the brain and what the long-term effects are, there’s enough reason to suggest people should be trying to avoid both infection and reinfection until researchers get more answers.

Worldwide, it’s estimated that COVID-19 has contributed to more than 40 million new cases of neurological disorders, says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, a clinical epidemiologist and long COVID researcher at Washington University in St. Louis. In his latest study of 14 million medical records of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the country’s largest integrated health care system, researchers found that regardless of age, gender, race, and lifestyle,

He noted that some of the conditions, such as headaches and mild decline in memory and sharpness, may improve and go away over time. But others that showed up, such as stroke, encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), and Guillain-Barré syndrome (a rare disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks the nerves), often lead to lasting damage. Dr. Al-Aly’s team found that neurological conditions were 7% more likely in those who had COVID-19 than in those who had never been infected.