User login

Focus Smoke-Free Home, Car Efforts on Parents of Young Children

DENVER – Parents who smoke are more likely to ban smoking at home if they have a child younger than age 10 years, if they don’t allow smoking in the car, if there’s just one or two smokers in their house, and if only the father smokes, according to a survey study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The findings "suggest opportunities for intervention with smoking households. Some things that come to mind are [if you are caring for] a child who is on the younger side, maybe you’ll have increased traction for [advocating] a smoke-free home. Maybe you want to work on [encouraging a] smoke-free car and smoke-free home synergistically" because the two seem to correlate, said senior author Dr. Jonathan P. Winickoff of the department of pediatrics at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Because homes are where children are most exposed to secondhand smoke, he and his colleagues wanted to see what factors were associated with a home-smoking ban in order to help clinicians know where to focus their efforts.

"We thought that if we could identify what some of these associated factors were, it might give us some clues about how best to intervene," Dr. Winickoff said.

They surveyed 661 smoking parents in seven pediatric practices. Half were white, 22% were black, 18% Hispanic, and 10% other. About half reported that "no one is allowed to smoke anywhere in the house," and that no one had smoked at home in the past 3 months.

Odds ratios in the study were all statistically significant. For example, if there was a child younger than age 5 years at home, the adjusted OR for a smoke-free home was 3.17; for a child aged 6-10 years old, the OR was 2.01. The OR for a smoke-free home was 2.21 if there was just one or two smokers living in the house, and 2.45 if only the father smoked. If parents banned smoking in the car, the OR for a smoke-free home was 4.13.

Other factors made a home-smoking ban less likely. If parents came to the practice for a sick-child visit, the adjusted OR for a smoke-free home was 0.46, which makes sense, Dr. Winickoff said, because smoking parents are more likely to have sicker children.

Being on Medicaid rather than private insurance also made a smoke-free home less likely (OR, 0.46), as did being black (OR, 0.47) or having a parent who smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day (OR, 0.46).

However, because the results were based on parents’ self-reports, they may have underestimated the exposure of children to smoking in the home. "Who wants to admit to their [infant’s] being exposed to secondhand smoke?" Dr. Winickoff asked.

Dr. Winickoff said he had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

DENVER – Parents who smoke are more likely to ban smoking at home if they have a child younger than age 10 years, if they don’t allow smoking in the car, if there’s just one or two smokers in their house, and if only the father smokes, according to a survey study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The findings "suggest opportunities for intervention with smoking households. Some things that come to mind are [if you are caring for] a child who is on the younger side, maybe you’ll have increased traction for [advocating] a smoke-free home. Maybe you want to work on [encouraging a] smoke-free car and smoke-free home synergistically" because the two seem to correlate, said senior author Dr. Jonathan P. Winickoff of the department of pediatrics at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Because homes are where children are most exposed to secondhand smoke, he and his colleagues wanted to see what factors were associated with a home-smoking ban in order to help clinicians know where to focus their efforts.

"We thought that if we could identify what some of these associated factors were, it might give us some clues about how best to intervene," Dr. Winickoff said.

They surveyed 661 smoking parents in seven pediatric practices. Half were white, 22% were black, 18% Hispanic, and 10% other. About half reported that "no one is allowed to smoke anywhere in the house," and that no one had smoked at home in the past 3 months.

Odds ratios in the study were all statistically significant. For example, if there was a child younger than age 5 years at home, the adjusted OR for a smoke-free home was 3.17; for a child aged 6-10 years old, the OR was 2.01. The OR for a smoke-free home was 2.21 if there was just one or two smokers living in the house, and 2.45 if only the father smoked. If parents banned smoking in the car, the OR for a smoke-free home was 4.13.

Other factors made a home-smoking ban less likely. If parents came to the practice for a sick-child visit, the adjusted OR for a smoke-free home was 0.46, which makes sense, Dr. Winickoff said, because smoking parents are more likely to have sicker children.

Being on Medicaid rather than private insurance also made a smoke-free home less likely (OR, 0.46), as did being black (OR, 0.47) or having a parent who smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day (OR, 0.46).

However, because the results were based on parents’ self-reports, they may have underestimated the exposure of children to smoking in the home. "Who wants to admit to their [infant’s] being exposed to secondhand smoke?" Dr. Winickoff asked.

Dr. Winickoff said he had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

DENVER – Parents who smoke are more likely to ban smoking at home if they have a child younger than age 10 years, if they don’t allow smoking in the car, if there’s just one or two smokers in their house, and if only the father smokes, according to a survey study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The findings "suggest opportunities for intervention with smoking households. Some things that come to mind are [if you are caring for] a child who is on the younger side, maybe you’ll have increased traction for [advocating] a smoke-free home. Maybe you want to work on [encouraging a] smoke-free car and smoke-free home synergistically" because the two seem to correlate, said senior author Dr. Jonathan P. Winickoff of the department of pediatrics at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Because homes are where children are most exposed to secondhand smoke, he and his colleagues wanted to see what factors were associated with a home-smoking ban in order to help clinicians know where to focus their efforts.

"We thought that if we could identify what some of these associated factors were, it might give us some clues about how best to intervene," Dr. Winickoff said.

They surveyed 661 smoking parents in seven pediatric practices. Half were white, 22% were black, 18% Hispanic, and 10% other. About half reported that "no one is allowed to smoke anywhere in the house," and that no one had smoked at home in the past 3 months.

Odds ratios in the study were all statistically significant. For example, if there was a child younger than age 5 years at home, the adjusted OR for a smoke-free home was 3.17; for a child aged 6-10 years old, the OR was 2.01. The OR for a smoke-free home was 2.21 if there was just one or two smokers living in the house, and 2.45 if only the father smoked. If parents banned smoking in the car, the OR for a smoke-free home was 4.13.

Other factors made a home-smoking ban less likely. If parents came to the practice for a sick-child visit, the adjusted OR for a smoke-free home was 0.46, which makes sense, Dr. Winickoff said, because smoking parents are more likely to have sicker children.

Being on Medicaid rather than private insurance also made a smoke-free home less likely (OR, 0.46), as did being black (OR, 0.47) or having a parent who smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day (OR, 0.46).

However, because the results were based on parents’ self-reports, they may have underestimated the exposure of children to smoking in the home. "Who wants to admit to their [infant’s] being exposed to secondhand smoke?" Dr. Winickoff asked.

Dr. Winickoff said he had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Major Finding: If smoking parents had a child younger than age 5 years, the adjusted odds ratio for a smoke-free home was 3.17, and if parents banned smoking in the car, the OR for a smoke-free home was 4.13. Both ORs were statistically significant.

Data Source: A survey study of 661 parents in seven pediatric practices.

Disclosures: Dr. Winickoff said he had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Hospitalists Provide Higher Quality of Care in Bronchiolitis

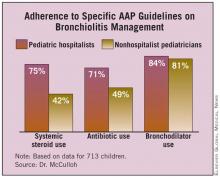

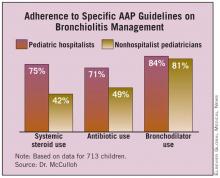

DENVER – Pediatric hospitalists adhere more closely to bronchiolitis management guidelines than do nonhospitalist pediatricians, according to a multicenter chart review.

The implication is that hospitalists therefore provide a higher quality of care. This notion is supported by the study finding that hospitalist-managed patients were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. On the other hand, neither overall length of stay nor rates of rehospitalization within 4 weeks were significantly different for pediatric hospitalist- and nonhospitalist-managed patients with bronchiolitis, Dr. Russell McCulloh reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Prior attempts to compare the quality of care provided by pediatric hospitalists and nonhospitalists have generally relied upon self-reported rates of guideline adherence obtained in physician surveys. To generate more objective data, Dr. McCulloh and coworkers at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., analyzed the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

The investigators selected bronchiolitis as the index diagnosis for their quality-of-care study because it is the No. 1 cause of hospital admission in children. The quality standard against which physician management was measured was the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for bronchiolitis diagnosis and management (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93).

Reviewers focused on three quality indicators contained in the guidelines. First, the AAP guidelines recommend that corticosteroids shouldn’t be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis. Pediatric hospitalists were clearly more in step with this guidance. The review showed that they discontinued systemic steroids when no indication existed 75% of the time, compared with 42% for nonhospitalists, according to Dr. McCulloh.

Second, hospitalists similarly discontinued antibiotics in the absence of specific indications of a coexistent bacterial infection 71% of the time. Nonhospitalist pediatricians were in step with this AAP recommendation only 49% of the time.

Third, regarding the discontinuation of bronchodilators in the absence of a documented, objective, positive clinical response, both types of physicians showed room for improvement. Hospitalists stopped albuterol in only 84% of cases when it had been proved ineffective; nonhospitalist pediatricians did so 81% of the time. Those rates of guideline adherence are insufficient, Dr. McCulloh commented.

On the other hand, hospitalists discontinued unneeded racemic epinephrine 93% of the time, as did nonhospitalists in 91% of cases in which it was appropriate to do so.

Rehospitalization within 4 weeks occurred in 4.6% of pediatric hospitalist–managed patients and in 7.2% of those managed by nonhospitalist pediatricians, a nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 10.9% ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Dr. McCulloh declared having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Pediatric hospitalists adhere more closely to bronchiolitis management guidelines than do nonhospitalist pediatricians, according to a multicenter chart review.

The implication is that hospitalists therefore provide a higher quality of care. This notion is supported by the study finding that hospitalist-managed patients were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. On the other hand, neither overall length of stay nor rates of rehospitalization within 4 weeks were significantly different for pediatric hospitalist- and nonhospitalist-managed patients with bronchiolitis, Dr. Russell McCulloh reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Prior attempts to compare the quality of care provided by pediatric hospitalists and nonhospitalists have generally relied upon self-reported rates of guideline adherence obtained in physician surveys. To generate more objective data, Dr. McCulloh and coworkers at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., analyzed the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

The investigators selected bronchiolitis as the index diagnosis for their quality-of-care study because it is the No. 1 cause of hospital admission in children. The quality standard against which physician management was measured was the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for bronchiolitis diagnosis and management (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93).

Reviewers focused on three quality indicators contained in the guidelines. First, the AAP guidelines recommend that corticosteroids shouldn’t be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis. Pediatric hospitalists were clearly more in step with this guidance. The review showed that they discontinued systemic steroids when no indication existed 75% of the time, compared with 42% for nonhospitalists, according to Dr. McCulloh.

Second, hospitalists similarly discontinued antibiotics in the absence of specific indications of a coexistent bacterial infection 71% of the time. Nonhospitalist pediatricians were in step with this AAP recommendation only 49% of the time.

Third, regarding the discontinuation of bronchodilators in the absence of a documented, objective, positive clinical response, both types of physicians showed room for improvement. Hospitalists stopped albuterol in only 84% of cases when it had been proved ineffective; nonhospitalist pediatricians did so 81% of the time. Those rates of guideline adherence are insufficient, Dr. McCulloh commented.

On the other hand, hospitalists discontinued unneeded racemic epinephrine 93% of the time, as did nonhospitalists in 91% of cases in which it was appropriate to do so.

Rehospitalization within 4 weeks occurred in 4.6% of pediatric hospitalist–managed patients and in 7.2% of those managed by nonhospitalist pediatricians, a nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 10.9% ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Dr. McCulloh declared having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Pediatric hospitalists adhere more closely to bronchiolitis management guidelines than do nonhospitalist pediatricians, according to a multicenter chart review.

The implication is that hospitalists therefore provide a higher quality of care. This notion is supported by the study finding that hospitalist-managed patients were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. On the other hand, neither overall length of stay nor rates of rehospitalization within 4 weeks were significantly different for pediatric hospitalist- and nonhospitalist-managed patients with bronchiolitis, Dr. Russell McCulloh reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Prior attempts to compare the quality of care provided by pediatric hospitalists and nonhospitalists have generally relied upon self-reported rates of guideline adherence obtained in physician surveys. To generate more objective data, Dr. McCulloh and coworkers at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., analyzed the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

The investigators selected bronchiolitis as the index diagnosis for their quality-of-care study because it is the No. 1 cause of hospital admission in children. The quality standard against which physician management was measured was the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for bronchiolitis diagnosis and management (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93).

Reviewers focused on three quality indicators contained in the guidelines. First, the AAP guidelines recommend that corticosteroids shouldn’t be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis. Pediatric hospitalists were clearly more in step with this guidance. The review showed that they discontinued systemic steroids when no indication existed 75% of the time, compared with 42% for nonhospitalists, according to Dr. McCulloh.

Second, hospitalists similarly discontinued antibiotics in the absence of specific indications of a coexistent bacterial infection 71% of the time. Nonhospitalist pediatricians were in step with this AAP recommendation only 49% of the time.

Third, regarding the discontinuation of bronchodilators in the absence of a documented, objective, positive clinical response, both types of physicians showed room for improvement. Hospitalists stopped albuterol in only 84% of cases when it had been proved ineffective; nonhospitalist pediatricians did so 81% of the time. Those rates of guideline adherence are insufficient, Dr. McCulloh commented.

On the other hand, hospitalists discontinued unneeded racemic epinephrine 93% of the time, as did nonhospitalists in 91% of cases in which it was appropriate to do so.

Rehospitalization within 4 weeks occurred in 4.6% of pediatric hospitalist–managed patients and in 7.2% of those managed by nonhospitalist pediatricians, a nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 10.9% ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Dr. McCulloh declared having no financial conflicts.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Major Finding: The ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was 10.9%, significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Data Source: An analysis of the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

Disclosures: The researcher reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Hospitalists Provide Higher Quality of Care in Bronchiolitis

DENVER – Pediatric hospitalists adhere more closely to bronchiolitis management guidelines than do nonhospitalist pediatricians, according to a multicenter chart review.

The implication is that hospitalists therefore provide a higher quality of care. This notion is supported by the study finding that hospitalist-managed patients were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. On the other hand, neither overall length of stay nor rates of rehospitalization within 4 weeks were significantly different for pediatric hospitalist- and nonhospitalist-managed patients with bronchiolitis, Dr. Russell McCulloh reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Prior attempts to compare the quality of care provided by pediatric hospitalists and nonhospitalists have generally relied upon self-reported rates of guideline adherence obtained in physician surveys. To generate more objective data, Dr. McCulloh and coworkers at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., analyzed the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

The investigators selected bronchiolitis as the index diagnosis for their quality-of-care study because it is the No. 1 cause of hospital admission in children. The quality standard against which physician management was measured was the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for bronchiolitis diagnosis and management (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93).

Reviewers focused on three quality indicators contained in the guidelines. First, the AAP guidelines recommend that corticosteroids shouldn’t be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis. Pediatric hospitalists were clearly more in step with this guidance. The review showed that they discontinued systemic steroids when no indication existed 75% of the time, compared with 42% for nonhospitalists, according to Dr. McCulloh.

Second, hospitalists similarly discontinued antibiotics in the absence of specific indications of a coexistent bacterial infection 71% of the time. Nonhospitalist pediatricians were in step with this AAP recommendation only 49% of the time.

Third, regarding the discontinuation of bronchodilators in the absence of a documented, objective, positive clinical response, both types of physicians showed room for improvement. Hospitalists stopped albuterol in only 84% of cases when it had been proved ineffective; nonhospitalist pediatricians did so 81% of the time. Those rates of guideline adherence are insufficient, Dr. McCulloh commented.

On the other hand, hospitalists discontinued unneeded racemic epinephrine 93% of the time, as did nonhospitalists in 91% of cases in which it was appropriate to do so.

Rehospitalization within 4 weeks occurred in 4.6% of pediatric hospitalist–managed patients and in 7.2% of those managed by nonhospitalist pediatricians, a nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 10.9% ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Dr. McCulloh declared having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Pediatric hospitalists adhere more closely to bronchiolitis management guidelines than do nonhospitalist pediatricians, according to a multicenter chart review.

The implication is that hospitalists therefore provide a higher quality of care. This notion is supported by the study finding that hospitalist-managed patients were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. On the other hand, neither overall length of stay nor rates of rehospitalization within 4 weeks were significantly different for pediatric hospitalist- and nonhospitalist-managed patients with bronchiolitis, Dr. Russell McCulloh reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Prior attempts to compare the quality of care provided by pediatric hospitalists and nonhospitalists have generally relied upon self-reported rates of guideline adherence obtained in physician surveys. To generate more objective data, Dr. McCulloh and coworkers at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., analyzed the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

The investigators selected bronchiolitis as the index diagnosis for their quality-of-care study because it is the No. 1 cause of hospital admission in children. The quality standard against which physician management was measured was the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for bronchiolitis diagnosis and management (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93).

Reviewers focused on three quality indicators contained in the guidelines. First, the AAP guidelines recommend that corticosteroids shouldn’t be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis. Pediatric hospitalists were clearly more in step with this guidance. The review showed that they discontinued systemic steroids when no indication existed 75% of the time, compared with 42% for nonhospitalists, according to Dr. McCulloh.

Second, hospitalists similarly discontinued antibiotics in the absence of specific indications of a coexistent bacterial infection 71% of the time. Nonhospitalist pediatricians were in step with this AAP recommendation only 49% of the time.

Third, regarding the discontinuation of bronchodilators in the absence of a documented, objective, positive clinical response, both types of physicians showed room for improvement. Hospitalists stopped albuterol in only 84% of cases when it had been proved ineffective; nonhospitalist pediatricians did so 81% of the time. Those rates of guideline adherence are insufficient, Dr. McCulloh commented.

On the other hand, hospitalists discontinued unneeded racemic epinephrine 93% of the time, as did nonhospitalists in 91% of cases in which it was appropriate to do so.

Rehospitalization within 4 weeks occurred in 4.6% of pediatric hospitalist–managed patients and in 7.2% of those managed by nonhospitalist pediatricians, a nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 10.9% ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Dr. McCulloh declared having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Pediatric hospitalists adhere more closely to bronchiolitis management guidelines than do nonhospitalist pediatricians, according to a multicenter chart review.

The implication is that hospitalists therefore provide a higher quality of care. This notion is supported by the study finding that hospitalist-managed patients were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. On the other hand, neither overall length of stay nor rates of rehospitalization within 4 weeks were significantly different for pediatric hospitalist- and nonhospitalist-managed patients with bronchiolitis, Dr. Russell McCulloh reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Prior attempts to compare the quality of care provided by pediatric hospitalists and nonhospitalists have generally relied upon self-reported rates of guideline adherence obtained in physician surveys. To generate more objective data, Dr. McCulloh and coworkers at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., analyzed the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

The investigators selected bronchiolitis as the index diagnosis for their quality-of-care study because it is the No. 1 cause of hospital admission in children. The quality standard against which physician management was measured was the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for bronchiolitis diagnosis and management (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93).

Reviewers focused on three quality indicators contained in the guidelines. First, the AAP guidelines recommend that corticosteroids shouldn’t be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis. Pediatric hospitalists were clearly more in step with this guidance. The review showed that they discontinued systemic steroids when no indication existed 75% of the time, compared with 42% for nonhospitalists, according to Dr. McCulloh.

Second, hospitalists similarly discontinued antibiotics in the absence of specific indications of a coexistent bacterial infection 71% of the time. Nonhospitalist pediatricians were in step with this AAP recommendation only 49% of the time.

Third, regarding the discontinuation of bronchodilators in the absence of a documented, objective, positive clinical response, both types of physicians showed room for improvement. Hospitalists stopped albuterol in only 84% of cases when it had been proved ineffective; nonhospitalist pediatricians did so 81% of the time. Those rates of guideline adherence are insufficient, Dr. McCulloh commented.

On the other hand, hospitalists discontinued unneeded racemic epinephrine 93% of the time, as did nonhospitalists in 91% of cases in which it was appropriate to do so.

Rehospitalization within 4 weeks occurred in 4.6% of pediatric hospitalist–managed patients and in 7.2% of those managed by nonhospitalist pediatricians, a nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 10.9% ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Dr. McCulloh declared having no financial conflicts.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Major Finding: The ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was 10.9%, significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Data Source: An analysis of the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

Disclosures: The researcher reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Hospitalists Provide Higher Quality of Care in Bronchiolitis

Subspecialty May Be on the Horizon

DENVER – Pediatric hospitalists adhere more closely to bronchiolitis management guidelines than do nonhospitalist pediatricians, according to a multicenter chart review.

The implication is that hospitalists therefore provide a higher quality of care. This notion is supported by the study finding that hospitalist-managed patients were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. On the other hand, neither overall length of stay nor rates of rehospitalization within 4 weeks were significantly different for pediatric hospitalist- and nonhospitalist-managed patients with bronchiolitis, Dr. Russell McCulloh reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Prior attempts to compare the quality of care provided by pediatric hospitalists and nonhospitalists have generally relied upon self-reported rates of guideline adherence obtained in physician surveys. To generate more objective data, Dr. McCulloh and coworkers at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., analyzed the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

The investigators selected bronchiolitis as the index diagnosis for their quality-of-care study because it is the No. 1 cause of hospital admission in children. The quality standard against which physician management was measured was the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for bronchiolitis diagnosis and management (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93).

Reviewers focused on three quality indicators contained in the guidelines. First, the AAP guidelines recommend that corticosteroids shouldn’t be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis. Pediatric hospitalists were clearly more in step with this guidance. The review showed that they discontinued systemic steroids when no indication existed 75% of the time, compared with 42% for nonhospitalists, according to Dr. McCulloh.

Second, hospitalists similarly discontinued antibiotics in the absence of specific indications of a coexistent bacterial infection 71% of the time. Nonhospitalist pediatricians were in step with this AAP recommendation only 49% of the time.

Third, regarding the discontinuation of bronchodilators in the absence of a documented, objective, positive clinical response, both types of physicians showed room for improvement. Hospitalists stopped albuterol in only 84% of cases when it had been proved ineffective; nonhospitalist pediatricians did so 81% of the time. Those rates of guideline adherence are insufficient, Dr. McCulloh commented.

On the other hand, hospitalists discontinued unneeded racemic epinephrine 93% of the time, as did nonhospitalists in 91% of cases in which it was appropriate to do so.

Rehospitalization within 4 weeks occurred in 4.6% of pediatric hospitalist–managed patients and in 7.2% of those managed by nonhospitalist pediatricians, a nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 10.9% ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Dr. McCulloh declared having no financial conflicts.

Medical knowledge

is too vast to be mastered by an individual. The location in which medical care

is delivered, rather than the organ system involved, has become a common

paradigm for delineating subspecialization.

The PICU, NICU and ED have

all become boarded pediatric subspecialties. Pediatric inpatient medicine

continues to evolve and has yet to determine whether to adopt a traditional

board format (3-year fellowship with a research requirement), follow adult

hospitalists with a focused practice certification (after 3 years of real-world

and real-income experience), or to become a separate track within a 3-year pediatric

residency program. As an already large and the fastest-growing subspecialty,

hospitalists may break those molds and establish their own accreditation

format. Committees are examining these options, each sparking debate at the

annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

Requiring less start up

time than an outpatient practice, for the past decade hospital positions have

been attractive to those seeking a temporary position after residency. But as these

numbers show, the vast and growing majority of hospitalists are adopting

inpatient medicine as an exciting career path. As a lifestyle choice, it is

also more amenable to part-time positions, shift work such as nocturnists, and

extended leaves of absence.

Intellectually, hospital

medicine demands different knowledge and skills than outpatient medicine. These

include the treatment of diseases in seriously ill children, coordinating care

for technology-dependent children, and providing procedural sedation.

More recently, the

emphasis of hospital medicine has focused on systemic issues, such as reducing

errors and other quality improvement programs. In the near future, providing

cost-effective care will gain importance.

Kevin Powell, M.D., Ph.D.,

is associate professor of pediatrics at St. Louis

University and a pediatric hospitalist

at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical

Center in St. Louis. He has no relevant disclosures nor

conflicts of interest to report.

Medical knowledge

is too vast to be mastered by an individual. The location in which medical care

is delivered, rather than the organ system involved, has become a common

paradigm for delineating subspecialization.

The PICU, NICU and ED have

all become boarded pediatric subspecialties. Pediatric inpatient medicine

continues to evolve and has yet to determine whether to adopt a traditional

board format (3-year fellowship with a research requirement), follow adult

hospitalists with a focused practice certification (after 3 years of real-world

and real-income experience), or to become a separate track within a 3-year pediatric

residency program. As an already large and the fastest-growing subspecialty,

hospitalists may break those molds and establish their own accreditation

format. Committees are examining these options, each sparking debate at the

annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

Requiring less start up

time than an outpatient practice, for the past decade hospital positions have

been attractive to those seeking a temporary position after residency. But as these

numbers show, the vast and growing majority of hospitalists are adopting

inpatient medicine as an exciting career path. As a lifestyle choice, it is

also more amenable to part-time positions, shift work such as nocturnists, and

extended leaves of absence.

Intellectually, hospital

medicine demands different knowledge and skills than outpatient medicine. These

include the treatment of diseases in seriously ill children, coordinating care

for technology-dependent children, and providing procedural sedation.

More recently, the

emphasis of hospital medicine has focused on systemic issues, such as reducing

errors and other quality improvement programs. In the near future, providing

cost-effective care will gain importance.

Kevin Powell, M.D., Ph.D.,

is associate professor of pediatrics at St. Louis

University and a pediatric hospitalist

at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical

Center in St. Louis. He has no relevant disclosures nor

conflicts of interest to report.

Medical knowledge

is too vast to be mastered by an individual. The location in which medical care

is delivered, rather than the organ system involved, has become a common

paradigm for delineating subspecialization.

The PICU, NICU and ED have

all become boarded pediatric subspecialties. Pediatric inpatient medicine

continues to evolve and has yet to determine whether to adopt a traditional

board format (3-year fellowship with a research requirement), follow adult

hospitalists with a focused practice certification (after 3 years of real-world

and real-income experience), or to become a separate track within a 3-year pediatric

residency program. As an already large and the fastest-growing subspecialty,

hospitalists may break those molds and establish their own accreditation

format. Committees are examining these options, each sparking debate at the

annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

Requiring less start up

time than an outpatient practice, for the past decade hospital positions have

been attractive to those seeking a temporary position after residency. But as these

numbers show, the vast and growing majority of hospitalists are adopting

inpatient medicine as an exciting career path. As a lifestyle choice, it is

also more amenable to part-time positions, shift work such as nocturnists, and

extended leaves of absence.

Intellectually, hospital

medicine demands different knowledge and skills than outpatient medicine. These

include the treatment of diseases in seriously ill children, coordinating care

for technology-dependent children, and providing procedural sedation.

More recently, the

emphasis of hospital medicine has focused on systemic issues, such as reducing

errors and other quality improvement programs. In the near future, providing

cost-effective care will gain importance.

Kevin Powell, M.D., Ph.D.,

is associate professor of pediatrics at St. Louis

University and a pediatric hospitalist

at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical

Center in St. Louis. He has no relevant disclosures nor

conflicts of interest to report.

Subspecialty May Be on the Horizon

Subspecialty May Be on the Horizon

DENVER – Pediatric hospitalists adhere more closely to bronchiolitis management guidelines than do nonhospitalist pediatricians, according to a multicenter chart review.

The implication is that hospitalists therefore provide a higher quality of care. This notion is supported by the study finding that hospitalist-managed patients were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. On the other hand, neither overall length of stay nor rates of rehospitalization within 4 weeks were significantly different for pediatric hospitalist- and nonhospitalist-managed patients with bronchiolitis, Dr. Russell McCulloh reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Prior attempts to compare the quality of care provided by pediatric hospitalists and nonhospitalists have generally relied upon self-reported rates of guideline adherence obtained in physician surveys. To generate more objective data, Dr. McCulloh and coworkers at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., analyzed the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

The investigators selected bronchiolitis as the index diagnosis for their quality-of-care study because it is the No. 1 cause of hospital admission in children. The quality standard against which physician management was measured was the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for bronchiolitis diagnosis and management (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93).

Reviewers focused on three quality indicators contained in the guidelines. First, the AAP guidelines recommend that corticosteroids shouldn’t be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis. Pediatric hospitalists were clearly more in step with this guidance. The review showed that they discontinued systemic steroids when no indication existed 75% of the time, compared with 42% for nonhospitalists, according to Dr. McCulloh.

Second, hospitalists similarly discontinued antibiotics in the absence of specific indications of a coexistent bacterial infection 71% of the time. Nonhospitalist pediatricians were in step with this AAP recommendation only 49% of the time.

Third, regarding the discontinuation of bronchodilators in the absence of a documented, objective, positive clinical response, both types of physicians showed room for improvement. Hospitalists stopped albuterol in only 84% of cases when it had been proved ineffective; nonhospitalist pediatricians did so 81% of the time. Those rates of guideline adherence are insufficient, Dr. McCulloh commented.

On the other hand, hospitalists discontinued unneeded racemic epinephrine 93% of the time, as did nonhospitalists in 91% of cases in which it was appropriate to do so.

Rehospitalization within 4 weeks occurred in 4.6% of pediatric hospitalist–managed patients and in 7.2% of those managed by nonhospitalist pediatricians, a nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 10.9% ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Dr. McCulloh declared having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Pediatric hospitalists adhere more closely to bronchiolitis management guidelines than do nonhospitalist pediatricians, according to a multicenter chart review.

The implication is that hospitalists therefore provide a higher quality of care. This notion is supported by the study finding that hospitalist-managed patients were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. On the other hand, neither overall length of stay nor rates of rehospitalization within 4 weeks were significantly different for pediatric hospitalist- and nonhospitalist-managed patients with bronchiolitis, Dr. Russell McCulloh reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Prior attempts to compare the quality of care provided by pediatric hospitalists and nonhospitalists have generally relied upon self-reported rates of guideline adherence obtained in physician surveys. To generate more objective data, Dr. McCulloh and coworkers at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., analyzed the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

The investigators selected bronchiolitis as the index diagnosis for their quality-of-care study because it is the No. 1 cause of hospital admission in children. The quality standard against which physician management was measured was the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for bronchiolitis diagnosis and management (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93).

Reviewers focused on three quality indicators contained in the guidelines. First, the AAP guidelines recommend that corticosteroids shouldn’t be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis. Pediatric hospitalists were clearly more in step with this guidance. The review showed that they discontinued systemic steroids when no indication existed 75% of the time, compared with 42% for nonhospitalists, according to Dr. McCulloh.

Second, hospitalists similarly discontinued antibiotics in the absence of specific indications of a coexistent bacterial infection 71% of the time. Nonhospitalist pediatricians were in step with this AAP recommendation only 49% of the time.

Third, regarding the discontinuation of bronchodilators in the absence of a documented, objective, positive clinical response, both types of physicians showed room for improvement. Hospitalists stopped albuterol in only 84% of cases when it had been proved ineffective; nonhospitalist pediatricians did so 81% of the time. Those rates of guideline adherence are insufficient, Dr. McCulloh commented.

On the other hand, hospitalists discontinued unneeded racemic epinephrine 93% of the time, as did nonhospitalists in 91% of cases in which it was appropriate to do so.

Rehospitalization within 4 weeks occurred in 4.6% of pediatric hospitalist–managed patients and in 7.2% of those managed by nonhospitalist pediatricians, a nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 10.9% ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Dr. McCulloh declared having no financial conflicts.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Pediatric Residency Graduates Find Hospitalist Practice Increasingly Irresistible

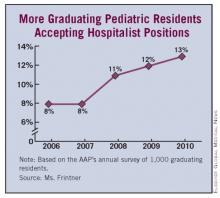

DENVER – Last year, roughly one in eight graduating pediatric residents accepted a hospitalist position.

These new pediatricians aren’t merely using the job as a stepping stone, either. Fully 84% of those who took a hospitalist position straight out of residency in 2010 say that being a hospitalist is their long-term career goal, Mary Pat Frintner said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

She presented highlights from the past 5 years of the American Academy of Pediatrics annual survey of graduating residents, administered to a random sample of 1,000 new graduates each year.

The proportion of graduating pediatric residents accepting a hospitalist position rose steadily from 8% in 2006 to 13% last year. Few of them reported any substantial difficulty in their job search: 45% indicated they experienced no difficulty at all in landing their position, and only 14% reported moderate and 3% considerable difficulty, according to Ms. Frintner of the department of research at AAP headquarters in Elk Grove Village, Ill.

Fifty-eight percent of the new pediatric hospitalists took a position in the same city as their residency. Two-thirds stayed in the same state.

The average full-time starting salary over the 5-year study period for residents taking a hospitalist position was $122,000 per year, with no significant increase over the years. Fifteen percent of 2010 grads who took a hospitalist position accepted a part-time, reduced-hours position.

Fifty-eight percent of the new pediatric hospitalists indicated that they will be working in a medical school or teaching hospital, and 36% in a community hospital. Community hospitals paid better.

Significant predictors of acceptance of a hospitalist position were having graduated from a residency training program with 60 or more residents, an educational debt of $120,000 or more, age less than 31 years, being nonmarried, and having gone to a U.S. medical school. Each of these predictors was only modest in power. Neither gender nor having children was significantly associated with taking a hospitalist position.

Across the full 5-year study span, 73% of those who took a pediatric hospitalist position upon graduation had hospitalist practice as their long-term goal. Twelve percent were aimed towards subspecialty practice, 10% had primary care pediatrics as their career goal, and 4% looked to a future involving a combined primary care/subspecialty practice.

Audience members commented that this AAP-funded study provides persuasive evidence in support of recognizing hospitalist practice as a pediatric subspecialty.

"With 13% of residents in 2010 going into it, if it were to be a pediatric subspecialty it would be the biggest subspecialty," one physician observed.

Of the roughly 30,000 hospitalists practicing today, only about 10% are believed to be pediatricians, Ms. Frintner noted.

Medical knowledge is too vast to be mastered by an individual. The location in which medical care is delivered, rather than the organ system involved, has become a common paradigm for delineating subspecialization.

The PICU, NICU and ED have all become boarded pediatric subspecialties. Pediatric inpatient medicine continues to evolve and has yet to determine whether to adopt a traditional board format (3-year fellowship with a research requirement), follow adult hospitalists with a focused practice certification (after 3 years of real-world and real-income experience), or to become a separate track within a 3-year pediatric residency program. As an already large and the fastest-growing subspecialty, hospitalists may break those molds and establish their own accreditation format. Committees are examining these options, each sparking debate at the annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

Requiring less start up time than an outpatient practice, for the past decade hospital positions have been attractive to those seeking a temporary position after residency. But as these numbers show, the vast and growing majority of hospitalists are adopting inpatient medicine as an exciting career path. As a lifestyle choice, it is also more amenable to part-time positions, shift work such as nocturnists, and extended leaves of absence.

Intellectually, hospital medicine demands different knowledge and skills than outpatient medicine. These include the treatment of diseases in seriously ill children, coordinating care for technology-dependent children, and providing procedural sedation.

More recently, the emphasis of hospital medicine has focused on systemic issues, such as reducing errors and other quality improvement programs. In the near future, providing cost-effective care will gain importance.

KEVIN POWELL, M.D., PH.D., is associate professor of pediatrics at St. Louis University and a pediatric hospitalist at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center in St. Louis. He has no relevant disclosures nor conflicts of interest to report.

Medical knowledge is too vast to be mastered by an individual. The location in which medical care is delivered, rather than the organ system involved, has become a common paradigm for delineating subspecialization.

The PICU, NICU and ED have all become boarded pediatric subspecialties. Pediatric inpatient medicine continues to evolve and has yet to determine whether to adopt a traditional board format (3-year fellowship with a research requirement), follow adult hospitalists with a focused practice certification (after 3 years of real-world and real-income experience), or to become a separate track within a 3-year pediatric residency program. As an already large and the fastest-growing subspecialty, hospitalists may break those molds and establish their own accreditation format. Committees are examining these options, each sparking debate at the annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

Requiring less start up time than an outpatient practice, for the past decade hospital positions have been attractive to those seeking a temporary position after residency. But as these numbers show, the vast and growing majority of hospitalists are adopting inpatient medicine as an exciting career path. As a lifestyle choice, it is also more amenable to part-time positions, shift work such as nocturnists, and extended leaves of absence.

Intellectually, hospital medicine demands different knowledge and skills than outpatient medicine. These include the treatment of diseases in seriously ill children, coordinating care for technology-dependent children, and providing procedural sedation.

More recently, the emphasis of hospital medicine has focused on systemic issues, such as reducing errors and other quality improvement programs. In the near future, providing cost-effective care will gain importance.

KEVIN POWELL, M.D., PH.D., is associate professor of pediatrics at St. Louis University and a pediatric hospitalist at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center in St. Louis. He has no relevant disclosures nor conflicts of interest to report.

Medical knowledge is too vast to be mastered by an individual. The location in which medical care is delivered, rather than the organ system involved, has become a common paradigm for delineating subspecialization.

The PICU, NICU and ED have all become boarded pediatric subspecialties. Pediatric inpatient medicine continues to evolve and has yet to determine whether to adopt a traditional board format (3-year fellowship with a research requirement), follow adult hospitalists with a focused practice certification (after 3 years of real-world and real-income experience), or to become a separate track within a 3-year pediatric residency program. As an already large and the fastest-growing subspecialty, hospitalists may break those molds and establish their own accreditation format. Committees are examining these options, each sparking debate at the annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

Requiring less start up time than an outpatient practice, for the past decade hospital positions have been attractive to those seeking a temporary position after residency. But as these numbers show, the vast and growing majority of hospitalists are adopting inpatient medicine as an exciting career path. As a lifestyle choice, it is also more amenable to part-time positions, shift work such as nocturnists, and extended leaves of absence.

Intellectually, hospital medicine demands different knowledge and skills than outpatient medicine. These include the treatment of diseases in seriously ill children, coordinating care for technology-dependent children, and providing procedural sedation.

More recently, the emphasis of hospital medicine has focused on systemic issues, such as reducing errors and other quality improvement programs. In the near future, providing cost-effective care will gain importance.

KEVIN POWELL, M.D., PH.D., is associate professor of pediatrics at St. Louis University and a pediatric hospitalist at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center in St. Louis. He has no relevant disclosures nor conflicts of interest to report.

DENVER – Last year, roughly one in eight graduating pediatric residents accepted a hospitalist position.

These new pediatricians aren’t merely using the job as a stepping stone, either. Fully 84% of those who took a hospitalist position straight out of residency in 2010 say that being a hospitalist is their long-term career goal, Mary Pat Frintner said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

She presented highlights from the past 5 years of the American Academy of Pediatrics annual survey of graduating residents, administered to a random sample of 1,000 new graduates each year.

The proportion of graduating pediatric residents accepting a hospitalist position rose steadily from 8% in 2006 to 13% last year. Few of them reported any substantial difficulty in their job search: 45% indicated they experienced no difficulty at all in landing their position, and only 14% reported moderate and 3% considerable difficulty, according to Ms. Frintner of the department of research at AAP headquarters in Elk Grove Village, Ill.

Fifty-eight percent of the new pediatric hospitalists took a position in the same city as their residency. Two-thirds stayed in the same state.

The average full-time starting salary over the 5-year study period for residents taking a hospitalist position was $122,000 per year, with no significant increase over the years. Fifteen percent of 2010 grads who took a hospitalist position accepted a part-time, reduced-hours position.

Fifty-eight percent of the new pediatric hospitalists indicated that they will be working in a medical school or teaching hospital, and 36% in a community hospital. Community hospitals paid better.

Significant predictors of acceptance of a hospitalist position were having graduated from a residency training program with 60 or more residents, an educational debt of $120,000 or more, age less than 31 years, being nonmarried, and having gone to a U.S. medical school. Each of these predictors was only modest in power. Neither gender nor having children was significantly associated with taking a hospitalist position.

Across the full 5-year study span, 73% of those who took a pediatric hospitalist position upon graduation had hospitalist practice as their long-term goal. Twelve percent were aimed towards subspecialty practice, 10% had primary care pediatrics as their career goal, and 4% looked to a future involving a combined primary care/subspecialty practice.

Audience members commented that this AAP-funded study provides persuasive evidence in support of recognizing hospitalist practice as a pediatric subspecialty.

"With 13% of residents in 2010 going into it, if it were to be a pediatric subspecialty it would be the biggest subspecialty," one physician observed.

Of the roughly 30,000 hospitalists practicing today, only about 10% are believed to be pediatricians, Ms. Frintner noted.

DENVER – Last year, roughly one in eight graduating pediatric residents accepted a hospitalist position.

These new pediatricians aren’t merely using the job as a stepping stone, either. Fully 84% of those who took a hospitalist position straight out of residency in 2010 say that being a hospitalist is their long-term career goal, Mary Pat Frintner said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

She presented highlights from the past 5 years of the American Academy of Pediatrics annual survey of graduating residents, administered to a random sample of 1,000 new graduates each year.

The proportion of graduating pediatric residents accepting a hospitalist position rose steadily from 8% in 2006 to 13% last year. Few of them reported any substantial difficulty in their job search: 45% indicated they experienced no difficulty at all in landing their position, and only 14% reported moderate and 3% considerable difficulty, according to Ms. Frintner of the department of research at AAP headquarters in Elk Grove Village, Ill.

Fifty-eight percent of the new pediatric hospitalists took a position in the same city as their residency. Two-thirds stayed in the same state.

The average full-time starting salary over the 5-year study period for residents taking a hospitalist position was $122,000 per year, with no significant increase over the years. Fifteen percent of 2010 grads who took a hospitalist position accepted a part-time, reduced-hours position.

Fifty-eight percent of the new pediatric hospitalists indicated that they will be working in a medical school or teaching hospital, and 36% in a community hospital. Community hospitals paid better.

Significant predictors of acceptance of a hospitalist position were having graduated from a residency training program with 60 or more residents, an educational debt of $120,000 or more, age less than 31 years, being nonmarried, and having gone to a U.S. medical school. Each of these predictors was only modest in power. Neither gender nor having children was significantly associated with taking a hospitalist position.

Across the full 5-year study span, 73% of those who took a pediatric hospitalist position upon graduation had hospitalist practice as their long-term goal. Twelve percent were aimed towards subspecialty practice, 10% had primary care pediatrics as their career goal, and 4% looked to a future involving a combined primary care/subspecialty practice.

Audience members commented that this AAP-funded study provides persuasive evidence in support of recognizing hospitalist practice as a pediatric subspecialty.

"With 13% of residents in 2010 going into it, if it were to be a pediatric subspecialty it would be the biggest subspecialty," one physician observed.

Of the roughly 30,000 hospitalists practicing today, only about 10% are believed to be pediatricians, Ms. Frintner noted.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

ADHD Stimulants Do Not Appear to Postpone Male Puberty

DENVER – Although some studies show a delay in growth among boys taking stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, a new study appears to clear the medications of postponing pubertal onset.

"Given that growth has been associated with pubertal onset, one might hypothesize that stimulant medication might affect the onset of puberty," Jennifer M. Steffes said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. "Few data exist, however, as to the potential association."

Ms. Steffes and her colleagues studied a multiethnic cohort of 3,868 boys who were seen at 141 clinical practices in the SSCIB (Secondary Sexual Characteristics in Boys) study. In all, 277 (7%) were taking stimulant medication. Clinicians received standardized training and evaluated genital development, pubic hair growth, and testicular volume for these boys (aged 6-16 years).

There were no significant differences between medicated and nonmedicated participants. Mean onset of genital growth (Tanner stage II) in the stimulant group was 9.84 years vs. 9.85 years in the nonstimulant group. Mean onset of pubic hair (Tanner stage II) in the stimulant group was 11.49 years vs. 11.14 years, and testicular volume of 3 mL or greater was observed in the stimulant group at a median 10.11 years, compared with 9.80 years among those who were not taking stimulant medication.

"Our results suggest that there is no difference in age of pubertal onset between boys taking stimulant medication and their nonmedicated counterparts," Ms. Steffes said.

"For clinicians, our research should be used as reassurance to parents – should stimulant medication be recommended – that the use of these stimulants will not delay pubertal maturation," said Ms. Steffes, an investigator for the PROS (Pediatric Research in Office Settings) research network at the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In addition, there were no significant differences in age of pubertal onset by race or ethnicity. The study included 1,979 white, 963 black, and 926 Hispanic children. Consecutive children and adolescents who were seen for well-child visits in 2005-2010 in 41 states were recruited through practices that participated in PROS, the Academic Pediatric Association’s CORNET (Continuity Research Network), and the NMA PedsNet (National Medical Association’s Pediatric Research Network).

Participants in the stimulant cohort took the medications regularly for 3 consecutive months within the past year. Testicular volume measurements were standardized via a modified Prader orchidometer.

Rigorous clinician training, use of the orchidometer, and inclusion of a broadly-representative geographic sample of children are among the strengths of the study, Ms. Steffes said. Limitations include its cross-sectional design; she noted that a randomized sample and/or longitudinal study design might have been more rigorous. Also, stimulant use was reported from multiple sources (chart review and self- or parent-report).

A meeting attendee asked about the science behind the evidence pointing to delayed growth with stimulant medications. Ms. Steffes deferred to a study coauthor in the audience.

"There [are some] data for a number of psychoactive medications possibly altering growth hormone release," Dr. Steven A. Dowshen said. "The problem with the studies is ... there really is inconsistency in terms of effects [of stimulants] on linear growth, although those [children] who show it tend to show a slowing of linear growth. The commonly accepted end point, though, is that eventually those kids catch up.

"That brings up the possibility, certainly to an endocrinologist, that the effects on growth might be mediated by delayed puberty. So in essence, the drug might be creating a constitutional growth delay," added Dr. Dowshen, a private practice pediatric endocrinologist in Wilmington, Del. "One of the reasons we were interested in looking at the data from PROS was to [to test] that hypothesis. And that wasn’t the case."

Ms. Steffes disclosed that she received a research grant from Pfizer to fund this project.

DENVER – Although some studies show a delay in growth among boys taking stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, a new study appears to clear the medications of postponing pubertal onset.

"Given that growth has been associated with pubertal onset, one might hypothesize that stimulant medication might affect the onset of puberty," Jennifer M. Steffes said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. "Few data exist, however, as to the potential association."

Ms. Steffes and her colleagues studied a multiethnic cohort of 3,868 boys who were seen at 141 clinical practices in the SSCIB (Secondary Sexual Characteristics in Boys) study. In all, 277 (7%) were taking stimulant medication. Clinicians received standardized training and evaluated genital development, pubic hair growth, and testicular volume for these boys (aged 6-16 years).

There were no significant differences between medicated and nonmedicated participants. Mean onset of genital growth (Tanner stage II) in the stimulant group was 9.84 years vs. 9.85 years in the nonstimulant group. Mean onset of pubic hair (Tanner stage II) in the stimulant group was 11.49 years vs. 11.14 years, and testicular volume of 3 mL or greater was observed in the stimulant group at a median 10.11 years, compared with 9.80 years among those who were not taking stimulant medication.

"Our results suggest that there is no difference in age of pubertal onset between boys taking stimulant medication and their nonmedicated counterparts," Ms. Steffes said.

"For clinicians, our research should be used as reassurance to parents – should stimulant medication be recommended – that the use of these stimulants will not delay pubertal maturation," said Ms. Steffes, an investigator for the PROS (Pediatric Research in Office Settings) research network at the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In addition, there were no significant differences in age of pubertal onset by race or ethnicity. The study included 1,979 white, 963 black, and 926 Hispanic children. Consecutive children and adolescents who were seen for well-child visits in 2005-2010 in 41 states were recruited through practices that participated in PROS, the Academic Pediatric Association’s CORNET (Continuity Research Network), and the NMA PedsNet (National Medical Association’s Pediatric Research Network).

Participants in the stimulant cohort took the medications regularly for 3 consecutive months within the past year. Testicular volume measurements were standardized via a modified Prader orchidometer.

Rigorous clinician training, use of the orchidometer, and inclusion of a broadly-representative geographic sample of children are among the strengths of the study, Ms. Steffes said. Limitations include its cross-sectional design; she noted that a randomized sample and/or longitudinal study design might have been more rigorous. Also, stimulant use was reported from multiple sources (chart review and self- or parent-report).

A meeting attendee asked about the science behind the evidence pointing to delayed growth with stimulant medications. Ms. Steffes deferred to a study coauthor in the audience.

"There [are some] data for a number of psychoactive medications possibly altering growth hormone release," Dr. Steven A. Dowshen said. "The problem with the studies is ... there really is inconsistency in terms of effects [of stimulants] on linear growth, although those [children] who show it tend to show a slowing of linear growth. The commonly accepted end point, though, is that eventually those kids catch up.

"That brings up the possibility, certainly to an endocrinologist, that the effects on growth might be mediated by delayed puberty. So in essence, the drug might be creating a constitutional growth delay," added Dr. Dowshen, a private practice pediatric endocrinologist in Wilmington, Del. "One of the reasons we were interested in looking at the data from PROS was to [to test] that hypothesis. And that wasn’t the case."

Ms. Steffes disclosed that she received a research grant from Pfizer to fund this project.

DENVER – Although some studies show a delay in growth among boys taking stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, a new study appears to clear the medications of postponing pubertal onset.

"Given that growth has been associated with pubertal onset, one might hypothesize that stimulant medication might affect the onset of puberty," Jennifer M. Steffes said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. "Few data exist, however, as to the potential association."

Ms. Steffes and her colleagues studied a multiethnic cohort of 3,868 boys who were seen at 141 clinical practices in the SSCIB (Secondary Sexual Characteristics in Boys) study. In all, 277 (7%) were taking stimulant medication. Clinicians received standardized training and evaluated genital development, pubic hair growth, and testicular volume for these boys (aged 6-16 years).

There were no significant differences between medicated and nonmedicated participants. Mean onset of genital growth (Tanner stage II) in the stimulant group was 9.84 years vs. 9.85 years in the nonstimulant group. Mean onset of pubic hair (Tanner stage II) in the stimulant group was 11.49 years vs. 11.14 years, and testicular volume of 3 mL or greater was observed in the stimulant group at a median 10.11 years, compared with 9.80 years among those who were not taking stimulant medication.

"Our results suggest that there is no difference in age of pubertal onset between boys taking stimulant medication and their nonmedicated counterparts," Ms. Steffes said.

"For clinicians, our research should be used as reassurance to parents – should stimulant medication be recommended – that the use of these stimulants will not delay pubertal maturation," said Ms. Steffes, an investigator for the PROS (Pediatric Research in Office Settings) research network at the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In addition, there were no significant differences in age of pubertal onset by race or ethnicity. The study included 1,979 white, 963 black, and 926 Hispanic children. Consecutive children and adolescents who were seen for well-child visits in 2005-2010 in 41 states were recruited through practices that participated in PROS, the Academic Pediatric Association’s CORNET (Continuity Research Network), and the NMA PedsNet (National Medical Association’s Pediatric Research Network).

Participants in the stimulant cohort took the medications regularly for 3 consecutive months within the past year. Testicular volume measurements were standardized via a modified Prader orchidometer.

Rigorous clinician training, use of the orchidometer, and inclusion of a broadly-representative geographic sample of children are among the strengths of the study, Ms. Steffes said. Limitations include its cross-sectional design; she noted that a randomized sample and/or longitudinal study design might have been more rigorous. Also, stimulant use was reported from multiple sources (chart review and self- or parent-report).

A meeting attendee asked about the science behind the evidence pointing to delayed growth with stimulant medications. Ms. Steffes deferred to a study coauthor in the audience.

"There [are some] data for a number of psychoactive medications possibly altering growth hormone release," Dr. Steven A. Dowshen said. "The problem with the studies is ... there really is inconsistency in terms of effects [of stimulants] on linear growth, although those [children] who show it tend to show a slowing of linear growth. The commonly accepted end point, though, is that eventually those kids catch up.

"That brings up the possibility, certainly to an endocrinologist, that the effects on growth might be mediated by delayed puberty. So in essence, the drug might be creating a constitutional growth delay," added Dr. Dowshen, a private practice pediatric endocrinologist in Wilmington, Del. "One of the reasons we were interested in looking at the data from PROS was to [to test] that hypothesis. And that wasn’t the case."

Ms. Steffes disclosed that she received a research grant from Pfizer to fund this project.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Major Finding: Mean onset of genital growth (Tanner stage 2) in the stimulant group was 9.84 years versus 9.85 years in the non-stimulant group, and Mean onset of pubic hair Tanner stage 2 in the stimulant group was 11.49 years versus 11.14 years – both nonsignificant differences.

Data Source: A multiethnic cohort of 3,868 boys seen at 141 clinical practices in the Secondary Sexual Characteristics in Boys (SSCIB) study in which 7% were taking stimulant medications regularly for 3 consecutive months within the past year.

Disclosures: Ms. Steffes disclosed that she received a research grant from Pfizer to fund this project.

ADHD Stimulants Do Not Appear to Postpone Male Puberty

DENVER – Although some studies show a delay in growth among boys taking stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, a new study appears to clear the medications of postponing pubertal onset.

"Given that growth has been associated with pubertal onset, one might hypothesize that stimulant medication might affect the onset of puberty," Jennifer M. Steffes said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. "Few data exist, however, as to the potential association."

Ms. Steffes and her colleagues studied a multiethnic cohort of 3,868 boys who were seen at 141 clinical practices in the SSCIB (Secondary Sexual Characteristics in Boys) study. In all, 277 (7%) were taking stimulant medication. Clinicians received standardized training and evaluated genital development, pubic hair growth, and testicular volume for these boys (aged 6-16 years).

There were no significant differences between medicated and nonmedicated participants. Mean onset of genital growth (Tanner stage II) in the stimulant group was 9.84 years vs. 9.85 years in the nonstimulant group. Mean onset of pubic hair (Tanner stage II) in the stimulant group was 11.49 years vs. 11.14 years, and testicular volume of 3 mL or greater was observed in the stimulant group at a median 10.11 years, compared with 9.80 years among those who were not taking stimulant medication.

"Our results suggest that there is no difference in age of pubertal onset between boys taking stimulant medication and their nonmedicated counterparts," Ms. Steffes said.

"For clinicians, our research should be used as reassurance to parents – should stimulant medication be recommended – that the use of these stimulants will not delay pubertal maturation," said Ms. Steffes, an investigator for the PROS (Pediatric Research in Office Settings) research network at the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In addition, there were no significant differences in age of pubertal onset by race or ethnicity. The study included 1,979 white, 963 black, and 926 Hispanic children. Consecutive children and adolescents who were seen for well-child visits in 2005-2010 in 41 states were recruited through practices that participated in PROS, the Academic Pediatric Association’s CORNET (Continuity Research Network), and the NMA PedsNet (National Medical Association’s Pediatric Research Network).

Participants in the stimulant cohort took the medications regularly for 3 consecutive months within the past year. Testicular volume measurements were standardized via a modified Prader orchidometer.

Rigorous clinician training, use of the orchidometer, and inclusion of a broadly-representative geographic sample of children are among the strengths of the study, Ms. Steffes said. Limitations include its cross-sectional design; she noted that a randomized sample and/or longitudinal study design might have been more rigorous. Also, stimulant use was reported from multiple sources (chart review and self- or parent-report).

A meeting attendee asked about the science behind the evidence pointing to delayed growth with stimulant medications. Ms. Steffes deferred to a study coauthor in the audience.

"There [are some] data for a number of psychoactive medications possibly altering growth hormone release," Dr. Steven A. Dowshen said. "The problem with the studies is ... there really is inconsistency in terms of effects [of stimulants] on linear growth, although those [children] who show it tend to show a slowing of linear growth. The commonly accepted end point, though, is that eventually those kids catch up.

"That brings up the possibility, certainly to an endocrinologist, that the effects on growth might be mediated by delayed puberty. So in essence, the drug might be creating a constitutional growth delay," added Dr. Dowshen, a private practice pediatric endocrinologist in Wilmington, Del. "One of the reasons we were interested in looking at the data from PROS was to [to test] that hypothesis. And that wasn’t the case."