User login

Subspecialty May Be on the Horizon

DENVER – Pediatric hospitalists adhere more closely to bronchiolitis management guidelines than do nonhospitalist pediatricians, according to a multicenter chart review.

The implication is that hospitalists therefore provide a higher quality of care. This notion is supported by the study finding that hospitalist-managed patients were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. On the other hand, neither overall length of stay nor rates of rehospitalization within 4 weeks were significantly different for pediatric hospitalist- and nonhospitalist-managed patients with bronchiolitis, Dr. Russell McCulloh reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Prior attempts to compare the quality of care provided by pediatric hospitalists and nonhospitalists have generally relied upon self-reported rates of guideline adherence obtained in physician surveys. To generate more objective data, Dr. McCulloh and coworkers at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., analyzed the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

The investigators selected bronchiolitis as the index diagnosis for their quality-of-care study because it is the No. 1 cause of hospital admission in children. The quality standard against which physician management was measured was the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for bronchiolitis diagnosis and management (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93).

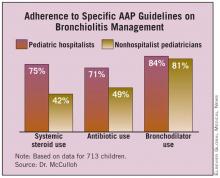

Reviewers focused on three quality indicators contained in the guidelines. First, the AAP guidelines recommend that corticosteroids shouldn’t be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis. Pediatric hospitalists were clearly more in step with this guidance. The review showed that they discontinued systemic steroids when no indication existed 75% of the time, compared with 42% for nonhospitalists, according to Dr. McCulloh.

Second, hospitalists similarly discontinued antibiotics in the absence of specific indications of a coexistent bacterial infection 71% of the time. Nonhospitalist pediatricians were in step with this AAP recommendation only 49% of the time.

Third, regarding the discontinuation of bronchodilators in the absence of a documented, objective, positive clinical response, both types of physicians showed room for improvement. Hospitalists stopped albuterol in only 84% of cases when it had been proved ineffective; nonhospitalist pediatricians did so 81% of the time. Those rates of guideline adherence are insufficient, Dr. McCulloh commented.

On the other hand, hospitalists discontinued unneeded racemic epinephrine 93% of the time, as did nonhospitalists in 91% of cases in which it was appropriate to do so.

Rehospitalization within 4 weeks occurred in 4.6% of pediatric hospitalist–managed patients and in 7.2% of those managed by nonhospitalist pediatricians, a nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 10.9% ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Dr. McCulloh declared having no financial conflicts.

Medical knowledge

is too vast to be mastered by an individual. The location in which medical care

is delivered, rather than the organ system involved, has become a common

paradigm for delineating subspecialization.

The PICU, NICU and ED have

all become boarded pediatric subspecialties. Pediatric inpatient medicine

continues to evolve and has yet to determine whether to adopt a traditional

board format (3-year fellowship with a research requirement), follow adult

hospitalists with a focused practice certification (after 3 years of real-world

and real-income experience), or to become a separate track within a 3-year pediatric

residency program. As an already large and the fastest-growing subspecialty,

hospitalists may break those molds and establish their own accreditation

format. Committees are examining these options, each sparking debate at the

annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

Requiring less start up

time than an outpatient practice, for the past decade hospital positions have

been attractive to those seeking a temporary position after residency. But as these

numbers show, the vast and growing majority of hospitalists are adopting

inpatient medicine as an exciting career path. As a lifestyle choice, it is

also more amenable to part-time positions, shift work such as nocturnists, and

extended leaves of absence.

Intellectually, hospital

medicine demands different knowledge and skills than outpatient medicine. These

include the treatment of diseases in seriously ill children, coordinating care

for technology-dependent children, and providing procedural sedation.

More recently, the

emphasis of hospital medicine has focused on systemic issues, such as reducing

errors and other quality improvement programs. In the near future, providing

cost-effective care will gain importance.

Kevin Powell, M.D., Ph.D.,

is associate professor of pediatrics at St. Louis

University and a pediatric hospitalist

at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical

Center in St. Louis. He has no relevant disclosures nor

conflicts of interest to report.

Medical knowledge

is too vast to be mastered by an individual. The location in which medical care

is delivered, rather than the organ system involved, has become a common

paradigm for delineating subspecialization.

The PICU, NICU and ED have

all become boarded pediatric subspecialties. Pediatric inpatient medicine

continues to evolve and has yet to determine whether to adopt a traditional

board format (3-year fellowship with a research requirement), follow adult

hospitalists with a focused practice certification (after 3 years of real-world

and real-income experience), or to become a separate track within a 3-year pediatric

residency program. As an already large and the fastest-growing subspecialty,

hospitalists may break those molds and establish their own accreditation

format. Committees are examining these options, each sparking debate at the

annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

Requiring less start up

time than an outpatient practice, for the past decade hospital positions have

been attractive to those seeking a temporary position after residency. But as these

numbers show, the vast and growing majority of hospitalists are adopting

inpatient medicine as an exciting career path. As a lifestyle choice, it is

also more amenable to part-time positions, shift work such as nocturnists, and

extended leaves of absence.

Intellectually, hospital

medicine demands different knowledge and skills than outpatient medicine. These

include the treatment of diseases in seriously ill children, coordinating care

for technology-dependent children, and providing procedural sedation.

More recently, the

emphasis of hospital medicine has focused on systemic issues, such as reducing

errors and other quality improvement programs. In the near future, providing

cost-effective care will gain importance.

Kevin Powell, M.D., Ph.D.,

is associate professor of pediatrics at St. Louis

University and a pediatric hospitalist

at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical

Center in St. Louis. He has no relevant disclosures nor

conflicts of interest to report.

Medical knowledge

is too vast to be mastered by an individual. The location in which medical care

is delivered, rather than the organ system involved, has become a common

paradigm for delineating subspecialization.

The PICU, NICU and ED have

all become boarded pediatric subspecialties. Pediatric inpatient medicine

continues to evolve and has yet to determine whether to adopt a traditional

board format (3-year fellowship with a research requirement), follow adult

hospitalists with a focused practice certification (after 3 years of real-world

and real-income experience), or to become a separate track within a 3-year pediatric

residency program. As an already large and the fastest-growing subspecialty,

hospitalists may break those molds and establish their own accreditation

format. Committees are examining these options, each sparking debate at the

annual Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

Requiring less start up

time than an outpatient practice, for the past decade hospital positions have

been attractive to those seeking a temporary position after residency. But as these

numbers show, the vast and growing majority of hospitalists are adopting

inpatient medicine as an exciting career path. As a lifestyle choice, it is

also more amenable to part-time positions, shift work such as nocturnists, and

extended leaves of absence.

Intellectually, hospital

medicine demands different knowledge and skills than outpatient medicine. These

include the treatment of diseases in seriously ill children, coordinating care

for technology-dependent children, and providing procedural sedation.

More recently, the

emphasis of hospital medicine has focused on systemic issues, such as reducing

errors and other quality improvement programs. In the near future, providing

cost-effective care will gain importance.

Kevin Powell, M.D., Ph.D.,

is associate professor of pediatrics at St. Louis

University and a pediatric hospitalist

at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical

Center in St. Louis. He has no relevant disclosures nor

conflicts of interest to report.

Subspecialty May Be on the Horizon

Subspecialty May Be on the Horizon

DENVER – Pediatric hospitalists adhere more closely to bronchiolitis management guidelines than do nonhospitalist pediatricians, according to a multicenter chart review.

The implication is that hospitalists therefore provide a higher quality of care. This notion is supported by the study finding that hospitalist-managed patients were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. On the other hand, neither overall length of stay nor rates of rehospitalization within 4 weeks were significantly different for pediatric hospitalist- and nonhospitalist-managed patients with bronchiolitis, Dr. Russell McCulloh reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Prior attempts to compare the quality of care provided by pediatric hospitalists and nonhospitalists have generally relied upon self-reported rates of guideline adherence obtained in physician surveys. To generate more objective data, Dr. McCulloh and coworkers at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., analyzed the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

The investigators selected bronchiolitis as the index diagnosis for their quality-of-care study because it is the No. 1 cause of hospital admission in children. The quality standard against which physician management was measured was the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for bronchiolitis diagnosis and management (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93).

Reviewers focused on three quality indicators contained in the guidelines. First, the AAP guidelines recommend that corticosteroids shouldn’t be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis. Pediatric hospitalists were clearly more in step with this guidance. The review showed that they discontinued systemic steroids when no indication existed 75% of the time, compared with 42% for nonhospitalists, according to Dr. McCulloh.

Second, hospitalists similarly discontinued antibiotics in the absence of specific indications of a coexistent bacterial infection 71% of the time. Nonhospitalist pediatricians were in step with this AAP recommendation only 49% of the time.

Third, regarding the discontinuation of bronchodilators in the absence of a documented, objective, positive clinical response, both types of physicians showed room for improvement. Hospitalists stopped albuterol in only 84% of cases when it had been proved ineffective; nonhospitalist pediatricians did so 81% of the time. Those rates of guideline adherence are insufficient, Dr. McCulloh commented.

On the other hand, hospitalists discontinued unneeded racemic epinephrine 93% of the time, as did nonhospitalists in 91% of cases in which it was appropriate to do so.

Rehospitalization within 4 weeks occurred in 4.6% of pediatric hospitalist–managed patients and in 7.2% of those managed by nonhospitalist pediatricians, a nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 10.9% ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Dr. McCulloh declared having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Pediatric hospitalists adhere more closely to bronchiolitis management guidelines than do nonhospitalist pediatricians, according to a multicenter chart review.

The implication is that hospitalists therefore provide a higher quality of care. This notion is supported by the study finding that hospitalist-managed patients were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit. On the other hand, neither overall length of stay nor rates of rehospitalization within 4 weeks were significantly different for pediatric hospitalist- and nonhospitalist-managed patients with bronchiolitis, Dr. Russell McCulloh reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Prior attempts to compare the quality of care provided by pediatric hospitalists and nonhospitalists have generally relied upon self-reported rates of guideline adherence obtained in physician surveys. To generate more objective data, Dr. McCulloh and coworkers at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., analyzed the charts of 713 children with bronchiolitis who were admitted to the pediatric hospitalist and nonhospitalist pediatric services at two academic tertiary medical centers in 2007-2008.

The investigators selected bronchiolitis as the index diagnosis for their quality-of-care study because it is the No. 1 cause of hospital admission in children. The quality standard against which physician management was measured was the 2006 American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for bronchiolitis diagnosis and management (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93).

Reviewers focused on three quality indicators contained in the guidelines. First, the AAP guidelines recommend that corticosteroids shouldn’t be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis. Pediatric hospitalists were clearly more in step with this guidance. The review showed that they discontinued systemic steroids when no indication existed 75% of the time, compared with 42% for nonhospitalists, according to Dr. McCulloh.

Second, hospitalists similarly discontinued antibiotics in the absence of specific indications of a coexistent bacterial infection 71% of the time. Nonhospitalist pediatricians were in step with this AAP recommendation only 49% of the time.

Third, regarding the discontinuation of bronchodilators in the absence of a documented, objective, positive clinical response, both types of physicians showed room for improvement. Hospitalists stopped albuterol in only 84% of cases when it had been proved ineffective; nonhospitalist pediatricians did so 81% of the time. Those rates of guideline adherence are insufficient, Dr. McCulloh commented.

On the other hand, hospitalists discontinued unneeded racemic epinephrine 93% of the time, as did nonhospitalists in 91% of cases in which it was appropriate to do so.

Rehospitalization within 4 weeks occurred in 4.6% of pediatric hospitalist–managed patients and in 7.2% of those managed by nonhospitalist pediatricians, a nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 10.9% ICU admission rate for hospitalist-managed bronchiolitis patients was significantly lower than the 16.3% rate among children managed by nonhospitalists.

Dr. McCulloh declared having no financial conflicts.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES