User login

Aggression, Tantrums in Preschoolers Linked to Lack of Sleep

Preschoolers with shorter nighttime sleep duration are more likely to exhibit aggression, tantrums, and other externalizing behaviors, according to a large, nationally representative study.

"Pediatricians now can have a clearer picture of how many hours preschool children are sleeping in this country. In addition, from this study we do know now that there is an association on a population level between externalizing behaviors and shorter sleep duration," said Dr. Ruth E.K. Stein.

In a study of 8,900 children, born in 2001, who participated in the ECLS-B (Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Birth Cohort), parents provided their child’s typical weekday bed times and wake up times at the data collection point when their child turned 4 years old. They also rated their child on the PKBS-2 (Preschool and Kindergarten Behavior Scale, 2nd ed.). This instrument assesses six externalizing behaviors (overactivity, anger, aggression, impulsivity, tantrums, and annoyance) on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (very often).

The 4-year-olds slept a mean of 10.47 hours per night, with a mean bed time of 8:39 p.m. and a wake up time of 7:13 a.m.

Short sleepers were defined as children who averaged less than 9.5 hours of sleep per night – that is, 1 standard deviation or more below the mean. These short sleepers differed significantly on all six externalizing behaviors, compared with preschoolers who averaged at least 9.5 hours of sleep per night. For example, overactivity (the most commonly reported externalizing behavior) occurred often in 25% of preschoolers who got at least 9.5 hours of sleep per night compared with 33% of short sleepers, according to Dr. Stein, professor of pediatrics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

Indeed, in a logistic regression analysis adjusted for socioeconomic status, parents in the home, hours of television viewing, race, and sex, the short sleep group was 27%-65% more likely to display each of the various externalizing behaviors "often."

In this study, weighted to be representative of nearly 4 million children born in the United States in 2001, 68.4% of children resided in a household with their biological mother and father. Another 22.2% lived with either their biological mother or father only, 2.1% with two legal guardians, 6.4% with their biological mother and other father, 0.8% with their biological father and other mother, and 0.1% with "other guardians."

A shortcoming of this U.S. Department of Education-funded study is that it doesn’t include any data on napping, although by age 4 years, many kids are probably no longer napping, she said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Denver.

When sleep duration is regarded as a continuous variable, as sleep duration increased, externalizing behaviors decreased. However, Dr. Stein observed that because this was a cross-sectional study, it’s not legitimate to invoke causality. That is, at this point it’s equally possible to conclude that short sleep duration causes externalizing behaviors in preschoolers or, alternatively, that kids with frequent externalizing behaviors are difficult to put to bed and hence get less sleep.

A planned longitudinal analysis incorporating ratings of the subjects’ behavior by outside observers in kindergarten should help clarify that issue.

Dr. Stein declared that she and her coinvestigators have no relevant financial disclosures.

Preschoolers with shorter nighttime sleep duration are more likely to exhibit aggression, tantrums, and other externalizing behaviors, according to a large, nationally representative study.

"Pediatricians now can have a clearer picture of how many hours preschool children are sleeping in this country. In addition, from this study we do know now that there is an association on a population level between externalizing behaviors and shorter sleep duration," said Dr. Ruth E.K. Stein.

In a study of 8,900 children, born in 2001, who participated in the ECLS-B (Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Birth Cohort), parents provided their child’s typical weekday bed times and wake up times at the data collection point when their child turned 4 years old. They also rated their child on the PKBS-2 (Preschool and Kindergarten Behavior Scale, 2nd ed.). This instrument assesses six externalizing behaviors (overactivity, anger, aggression, impulsivity, tantrums, and annoyance) on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (very often).

The 4-year-olds slept a mean of 10.47 hours per night, with a mean bed time of 8:39 p.m. and a wake up time of 7:13 a.m.

Short sleepers were defined as children who averaged less than 9.5 hours of sleep per night – that is, 1 standard deviation or more below the mean. These short sleepers differed significantly on all six externalizing behaviors, compared with preschoolers who averaged at least 9.5 hours of sleep per night. For example, overactivity (the most commonly reported externalizing behavior) occurred often in 25% of preschoolers who got at least 9.5 hours of sleep per night compared with 33% of short sleepers, according to Dr. Stein, professor of pediatrics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

Indeed, in a logistic regression analysis adjusted for socioeconomic status, parents in the home, hours of television viewing, race, and sex, the short sleep group was 27%-65% more likely to display each of the various externalizing behaviors "often."

In this study, weighted to be representative of nearly 4 million children born in the United States in 2001, 68.4% of children resided in a household with their biological mother and father. Another 22.2% lived with either their biological mother or father only, 2.1% with two legal guardians, 6.4% with their biological mother and other father, 0.8% with their biological father and other mother, and 0.1% with "other guardians."

A shortcoming of this U.S. Department of Education-funded study is that it doesn’t include any data on napping, although by age 4 years, many kids are probably no longer napping, she said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Denver.

When sleep duration is regarded as a continuous variable, as sleep duration increased, externalizing behaviors decreased. However, Dr. Stein observed that because this was a cross-sectional study, it’s not legitimate to invoke causality. That is, at this point it’s equally possible to conclude that short sleep duration causes externalizing behaviors in preschoolers or, alternatively, that kids with frequent externalizing behaviors are difficult to put to bed and hence get less sleep.

A planned longitudinal analysis incorporating ratings of the subjects’ behavior by outside observers in kindergarten should help clarify that issue.

Dr. Stein declared that she and her coinvestigators have no relevant financial disclosures.

Preschoolers with shorter nighttime sleep duration are more likely to exhibit aggression, tantrums, and other externalizing behaviors, according to a large, nationally representative study.

"Pediatricians now can have a clearer picture of how many hours preschool children are sleeping in this country. In addition, from this study we do know now that there is an association on a population level between externalizing behaviors and shorter sleep duration," said Dr. Ruth E.K. Stein.

In a study of 8,900 children, born in 2001, who participated in the ECLS-B (Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Birth Cohort), parents provided their child’s typical weekday bed times and wake up times at the data collection point when their child turned 4 years old. They also rated their child on the PKBS-2 (Preschool and Kindergarten Behavior Scale, 2nd ed.). This instrument assesses six externalizing behaviors (overactivity, anger, aggression, impulsivity, tantrums, and annoyance) on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (very often).

The 4-year-olds slept a mean of 10.47 hours per night, with a mean bed time of 8:39 p.m. and a wake up time of 7:13 a.m.

Short sleepers were defined as children who averaged less than 9.5 hours of sleep per night – that is, 1 standard deviation or more below the mean. These short sleepers differed significantly on all six externalizing behaviors, compared with preschoolers who averaged at least 9.5 hours of sleep per night. For example, overactivity (the most commonly reported externalizing behavior) occurred often in 25% of preschoolers who got at least 9.5 hours of sleep per night compared with 33% of short sleepers, according to Dr. Stein, professor of pediatrics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

Indeed, in a logistic regression analysis adjusted for socioeconomic status, parents in the home, hours of television viewing, race, and sex, the short sleep group was 27%-65% more likely to display each of the various externalizing behaviors "often."

In this study, weighted to be representative of nearly 4 million children born in the United States in 2001, 68.4% of children resided in a household with their biological mother and father. Another 22.2% lived with either their biological mother or father only, 2.1% with two legal guardians, 6.4% with their biological mother and other father, 0.8% with their biological father and other mother, and 0.1% with "other guardians."

A shortcoming of this U.S. Department of Education-funded study is that it doesn’t include any data on napping, although by age 4 years, many kids are probably no longer napping, she said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Denver.

When sleep duration is regarded as a continuous variable, as sleep duration increased, externalizing behaviors decreased. However, Dr. Stein observed that because this was a cross-sectional study, it’s not legitimate to invoke causality. That is, at this point it’s equally possible to conclude that short sleep duration causes externalizing behaviors in preschoolers or, alternatively, that kids with frequent externalizing behaviors are difficult to put to bed and hence get less sleep.

A planned longitudinal analysis incorporating ratings of the subjects’ behavior by outside observers in kindergarten should help clarify that issue.

Dr. Stein declared that she and her coinvestigators have no relevant financial disclosures.

Major Finding: Overactivity occurred often in 25% of preschoolers who got at least 9.5 hours of sleep per night, compared with 33% of short-duration sleepers.

Data Source: A study of 8,900 children, born in 2001, who participated in the ECLS-B.

Disclosures: Dr. Stein declared she and her coinvestigators have no relevant financial disclosures.

Family-Centered Pediatric Rounds Boost Satisfaction

Want to markedly boost family satisfaction with inpatient pediatric care, foster a closer physician-family bond, impress families that you and your health care team operate at a high level of skill and intergroup communication, and – while you’re at it – score major points with hospital administrators?

Adopt family-centered rounds as your hospital’s standard in conducting inpatient pediatric rounds.

That’s what the American Academy of Pediatrics urged some 8 years ago in a policy statement. The academy declared that standard practice should be to conduct rounds in patients’ rooms with both the health care team (attending physician, residents, medical students, and charge nurse) and the families present, instead of in the conventional fashion, with the team meeting out in the hallway or in a conference room separated from patient and family.

The AAP statement elaborated that family-centered rounds are "interdisciplinary work rounds at the bedside in which the patient and family share in the control of the management plan as well as in the evaluation of the process itself" (Pediatrics 2003;112:691-97).

A growing number of hospitals have heeded this AAP recommendation. Indeed, a recent survey of pediatric hospitalists concluded that family-centered rounds have become the standard method of rounding in 48% of academic and 31% of nonacademic hospitals (Pediatrics 2010;126:37-43). Yet few studies have actually examined the impact of family-centered rounds on family satisfaction with inpatient care.

Dr. Alan R. Schroeder and his colleagues at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose, Calif., have recently done so. And the results are unabashedly positive, he reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Denver.

The hospital’s general pediatric inpatient unit switched to family-centered rounds in September 2008. The resultant highly positive changes in families’ satisfaction with physicians, nurses, and quality of care for their child were documented through standardized anonymous surveys that were routinely administered on a quarterly basis by Professional Resource Consultants Inc. to 50 randomly selected families with recently discharged pediatric inpatients.

Here’s what the survey showed in a comparison of the proportion of "excellent" scores provided by 600 families during 2006-2008, prior to implementation of family-centered rounds, and by 457 families who were surveyed in 2009-2011:

• Overall quality of care was rated as excellent by 46.7% of families prior to introduction of family-centered rounds, compared with 60% afterwards.

• Overall quality of the physician’s care improved from a 54.5% excellent rating in 2006-2008 to 65.7% in 2009-2011.

• Nurses’ instructions and explanations of tests were rated excellent by 41.4% of families in 2006-2008 and by 53.7% of families after introduction of family-centered rounds.

• Physicians’ instructions about treatments and tests were rated excellent by 50.9% of families during 2006-2008 and by 60.3% in 2009-2011.

• Adoption of family-centered rounds appeared to have an impact extending beyond the physician-family relationship. Notably, 46.8% of families rated overall teamwork between physicians, nurses, and staff as excellent in 2006-2008, compared with 58.9% afterwards.

Because the hospital is dedicated to continuous quality improvement, Dr. Schroeder and coinvestigators sought to learn whether the increase in family satisfaction resulting from introduction of family-centered rounds could be differentiated from the impact of other constructive hospital changes that were made during the study period.

This appeared to be the case. The mean absolute 11.4% increase in family satisfaction scores on survey items that were deemed likely to be affected by family-centered rounds was greater than the 8.1% rise in items that were "possibly" related to family-centered rounding, such as satisfaction with the discharge process, and the 7.1% increase in satisfaction with survey items that were unlikely to be linked to family-centered rounds, such as hospital food quality, cleanliness, and nurses’ promptness in responding to phone calls.

Dr. Schroeder declared having no relevant financial disclosures.

Want to markedly boost family satisfaction with inpatient pediatric care, foster a closer physician-family bond, impress families that you and your health care team operate at a high level of skill and intergroup communication, and – while you’re at it – score major points with hospital administrators?

Adopt family-centered rounds as your hospital’s standard in conducting inpatient pediatric rounds.

That’s what the American Academy of Pediatrics urged some 8 years ago in a policy statement. The academy declared that standard practice should be to conduct rounds in patients’ rooms with both the health care team (attending physician, residents, medical students, and charge nurse) and the families present, instead of in the conventional fashion, with the team meeting out in the hallway or in a conference room separated from patient and family.

The AAP statement elaborated that family-centered rounds are "interdisciplinary work rounds at the bedside in which the patient and family share in the control of the management plan as well as in the evaluation of the process itself" (Pediatrics 2003;112:691-97).

A growing number of hospitals have heeded this AAP recommendation. Indeed, a recent survey of pediatric hospitalists concluded that family-centered rounds have become the standard method of rounding in 48% of academic and 31% of nonacademic hospitals (Pediatrics 2010;126:37-43). Yet few studies have actually examined the impact of family-centered rounds on family satisfaction with inpatient care.

Dr. Alan R. Schroeder and his colleagues at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose, Calif., have recently done so. And the results are unabashedly positive, he reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Denver.

The hospital’s general pediatric inpatient unit switched to family-centered rounds in September 2008. The resultant highly positive changes in families’ satisfaction with physicians, nurses, and quality of care for their child were documented through standardized anonymous surveys that were routinely administered on a quarterly basis by Professional Resource Consultants Inc. to 50 randomly selected families with recently discharged pediatric inpatients.

Here’s what the survey showed in a comparison of the proportion of "excellent" scores provided by 600 families during 2006-2008, prior to implementation of family-centered rounds, and by 457 families who were surveyed in 2009-2011:

• Overall quality of care was rated as excellent by 46.7% of families prior to introduction of family-centered rounds, compared with 60% afterwards.

• Overall quality of the physician’s care improved from a 54.5% excellent rating in 2006-2008 to 65.7% in 2009-2011.

• Nurses’ instructions and explanations of tests were rated excellent by 41.4% of families in 2006-2008 and by 53.7% of families after introduction of family-centered rounds.

• Physicians’ instructions about treatments and tests were rated excellent by 50.9% of families during 2006-2008 and by 60.3% in 2009-2011.

• Adoption of family-centered rounds appeared to have an impact extending beyond the physician-family relationship. Notably, 46.8% of families rated overall teamwork between physicians, nurses, and staff as excellent in 2006-2008, compared with 58.9% afterwards.

Because the hospital is dedicated to continuous quality improvement, Dr. Schroeder and coinvestigators sought to learn whether the increase in family satisfaction resulting from introduction of family-centered rounds could be differentiated from the impact of other constructive hospital changes that were made during the study period.

This appeared to be the case. The mean absolute 11.4% increase in family satisfaction scores on survey items that were deemed likely to be affected by family-centered rounds was greater than the 8.1% rise in items that were "possibly" related to family-centered rounding, such as satisfaction with the discharge process, and the 7.1% increase in satisfaction with survey items that were unlikely to be linked to family-centered rounds, such as hospital food quality, cleanliness, and nurses’ promptness in responding to phone calls.

Dr. Schroeder declared having no relevant financial disclosures.

Want to markedly boost family satisfaction with inpatient pediatric care, foster a closer physician-family bond, impress families that you and your health care team operate at a high level of skill and intergroup communication, and – while you’re at it – score major points with hospital administrators?

Adopt family-centered rounds as your hospital’s standard in conducting inpatient pediatric rounds.

That’s what the American Academy of Pediatrics urged some 8 years ago in a policy statement. The academy declared that standard practice should be to conduct rounds in patients’ rooms with both the health care team (attending physician, residents, medical students, and charge nurse) and the families present, instead of in the conventional fashion, with the team meeting out in the hallway or in a conference room separated from patient and family.

The AAP statement elaborated that family-centered rounds are "interdisciplinary work rounds at the bedside in which the patient and family share in the control of the management plan as well as in the evaluation of the process itself" (Pediatrics 2003;112:691-97).

A growing number of hospitals have heeded this AAP recommendation. Indeed, a recent survey of pediatric hospitalists concluded that family-centered rounds have become the standard method of rounding in 48% of academic and 31% of nonacademic hospitals (Pediatrics 2010;126:37-43). Yet few studies have actually examined the impact of family-centered rounds on family satisfaction with inpatient care.

Dr. Alan R. Schroeder and his colleagues at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center in San Jose, Calif., have recently done so. And the results are unabashedly positive, he reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Denver.

The hospital’s general pediatric inpatient unit switched to family-centered rounds in September 2008. The resultant highly positive changes in families’ satisfaction with physicians, nurses, and quality of care for their child were documented through standardized anonymous surveys that were routinely administered on a quarterly basis by Professional Resource Consultants Inc. to 50 randomly selected families with recently discharged pediatric inpatients.

Here’s what the survey showed in a comparison of the proportion of "excellent" scores provided by 600 families during 2006-2008, prior to implementation of family-centered rounds, and by 457 families who were surveyed in 2009-2011:

• Overall quality of care was rated as excellent by 46.7% of families prior to introduction of family-centered rounds, compared with 60% afterwards.

• Overall quality of the physician’s care improved from a 54.5% excellent rating in 2006-2008 to 65.7% in 2009-2011.

• Nurses’ instructions and explanations of tests were rated excellent by 41.4% of families in 2006-2008 and by 53.7% of families after introduction of family-centered rounds.

• Physicians’ instructions about treatments and tests were rated excellent by 50.9% of families during 2006-2008 and by 60.3% in 2009-2011.

• Adoption of family-centered rounds appeared to have an impact extending beyond the physician-family relationship. Notably, 46.8% of families rated overall teamwork between physicians, nurses, and staff as excellent in 2006-2008, compared with 58.9% afterwards.

Because the hospital is dedicated to continuous quality improvement, Dr. Schroeder and coinvestigators sought to learn whether the increase in family satisfaction resulting from introduction of family-centered rounds could be differentiated from the impact of other constructive hospital changes that were made during the study period.

This appeared to be the case. The mean absolute 11.4% increase in family satisfaction scores on survey items that were deemed likely to be affected by family-centered rounds was greater than the 8.1% rise in items that were "possibly" related to family-centered rounding, such as satisfaction with the discharge process, and the 7.1% increase in satisfaction with survey items that were unlikely to be linked to family-centered rounds, such as hospital food quality, cleanliness, and nurses’ promptness in responding to phone calls.

Dr. Schroeder declared having no relevant financial disclosures.

Natural History of Empyema in Children Largely Reassuring

What can you tell parents to reasonably expect after their child with empyema gets discharged from the hospital?

Clinically important sequelae commonly persist in the first month after discharge but resolve in almost all cases by 6 months. And the rare patient who has lingering significant abnormalities on chest x-ray or spirometry 6 months after leaving the hospital can expect them to normalize by 1 year, according to a prospective Canadian study.

"Long-term [sequelae] are uncommon. This information may aid decision making for clinicians and families balancing the risks and benefits of interventions," Dr. Eyal Cohen observed.

The findings in this observational study take on added clinical relevance because the incidence of complicated pneumonia, or empyema, is increasing throughout the world, particularly in younger children. Proposed explanations for this phenomenon include pneumococcal serotype replacement and/or evolving antimicrobial resistance patterns, said Dr. Cohen of the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.

He recently reported on 82 children with empyema – as defined by ultrasound evidence of pleural effusions with loculations – at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. The children were seen at 1 and 6 months post discharge, where they underwent clinical examination, a chest x-ray, quality-of-life assessment using the Peds-QL instrument, and spirometry if they were at least 5 years old.

The median age of the subjects was 3.6 years; 27% of them had an organism isolated, most commonly Streptococcus pneumoniae. Of note, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was the causative organism in only one child. A chest drain was used in 51 children, and 40 of those also received fibrinolytics. The remaining patients were treated only with antibiotics. Video-assisted thorascopic surgery was not employed.

The average length of hospital stay was 10 days. Eight children went to the pediatric ICU.

At discharge, 21% of patients still had fever, which lasted up to 1 further week; 7% of children were readmitted within 1 month.

At the 1-month follow-up, 18% of the patients had fever, 23% cough, and 2% failure to thrive; 59% of the school-age children had missed a median of 5 classroom days. By 6 months, however, only 16% of children were still coughing, and 30% of school-age children had missed an average of 2 days of school since the 1-month evaluation. None of the children were experiencing fever or failure to thrive at late follow-up.

At 1 month post discharge, 7 of 20 children had abnormal spirometry, defined as a forced expiratory volume in 1 second that is 80% or less of predicted. Of the 82 children, 24 had persistent abnormalities on chest x-ray, mostly effusion, pneumatocele, or abscess. Twelve of 68 parents rated their child’s health-related quality of life as abnormal based on a Peds-QL score more than 1 standard deviation below the normal population.

By 6 months, only one child had abnormal spirometry and three had persistent chest x-ray abnormalities. At 1 year, these abnormalities had resolved in three patients, while the fourth was lost to follow-up.

Moreover, at 6 months, parents rated their child’s quality of life on the Peds-QL as similar to that in 8,430 healthy historical controls and significantly better than were the scores for 157 children with asthma, according to Dr. Cohen.

He declared having no financial conflicts of interest.

What can you tell parents to reasonably expect after their child with empyema gets discharged from the hospital?

Clinically important sequelae commonly persist in the first month after discharge but resolve in almost all cases by 6 months. And the rare patient who has lingering significant abnormalities on chest x-ray or spirometry 6 months after leaving the hospital can expect them to normalize by 1 year, according to a prospective Canadian study.

"Long-term [sequelae] are uncommon. This information may aid decision making for clinicians and families balancing the risks and benefits of interventions," Dr. Eyal Cohen observed.

The findings in this observational study take on added clinical relevance because the incidence of complicated pneumonia, or empyema, is increasing throughout the world, particularly in younger children. Proposed explanations for this phenomenon include pneumococcal serotype replacement and/or evolving antimicrobial resistance patterns, said Dr. Cohen of the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.

He recently reported on 82 children with empyema – as defined by ultrasound evidence of pleural effusions with loculations – at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. The children were seen at 1 and 6 months post discharge, where they underwent clinical examination, a chest x-ray, quality-of-life assessment using the Peds-QL instrument, and spirometry if they were at least 5 years old.

The median age of the subjects was 3.6 years; 27% of them had an organism isolated, most commonly Streptococcus pneumoniae. Of note, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was the causative organism in only one child. A chest drain was used in 51 children, and 40 of those also received fibrinolytics. The remaining patients were treated only with antibiotics. Video-assisted thorascopic surgery was not employed.

The average length of hospital stay was 10 days. Eight children went to the pediatric ICU.

At discharge, 21% of patients still had fever, which lasted up to 1 further week; 7% of children were readmitted within 1 month.

At the 1-month follow-up, 18% of the patients had fever, 23% cough, and 2% failure to thrive; 59% of the school-age children had missed a median of 5 classroom days. By 6 months, however, only 16% of children were still coughing, and 30% of school-age children had missed an average of 2 days of school since the 1-month evaluation. None of the children were experiencing fever or failure to thrive at late follow-up.

At 1 month post discharge, 7 of 20 children had abnormal spirometry, defined as a forced expiratory volume in 1 second that is 80% or less of predicted. Of the 82 children, 24 had persistent abnormalities on chest x-ray, mostly effusion, pneumatocele, or abscess. Twelve of 68 parents rated their child’s health-related quality of life as abnormal based on a Peds-QL score more than 1 standard deviation below the normal population.

By 6 months, only one child had abnormal spirometry and three had persistent chest x-ray abnormalities. At 1 year, these abnormalities had resolved in three patients, while the fourth was lost to follow-up.

Moreover, at 6 months, parents rated their child’s quality of life on the Peds-QL as similar to that in 8,430 healthy historical controls and significantly better than were the scores for 157 children with asthma, according to Dr. Cohen.

He declared having no financial conflicts of interest.

What can you tell parents to reasonably expect after their child with empyema gets discharged from the hospital?

Clinically important sequelae commonly persist in the first month after discharge but resolve in almost all cases by 6 months. And the rare patient who has lingering significant abnormalities on chest x-ray or spirometry 6 months after leaving the hospital can expect them to normalize by 1 year, according to a prospective Canadian study.

"Long-term [sequelae] are uncommon. This information may aid decision making for clinicians and families balancing the risks and benefits of interventions," Dr. Eyal Cohen observed.

The findings in this observational study take on added clinical relevance because the incidence of complicated pneumonia, or empyema, is increasing throughout the world, particularly in younger children. Proposed explanations for this phenomenon include pneumococcal serotype replacement and/or evolving antimicrobial resistance patterns, said Dr. Cohen of the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.

He recently reported on 82 children with empyema – as defined by ultrasound evidence of pleural effusions with loculations – at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. The children were seen at 1 and 6 months post discharge, where they underwent clinical examination, a chest x-ray, quality-of-life assessment using the Peds-QL instrument, and spirometry if they were at least 5 years old.

The median age of the subjects was 3.6 years; 27% of them had an organism isolated, most commonly Streptococcus pneumoniae. Of note, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was the causative organism in only one child. A chest drain was used in 51 children, and 40 of those also received fibrinolytics. The remaining patients were treated only with antibiotics. Video-assisted thorascopic surgery was not employed.

The average length of hospital stay was 10 days. Eight children went to the pediatric ICU.

At discharge, 21% of patients still had fever, which lasted up to 1 further week; 7% of children were readmitted within 1 month.

At the 1-month follow-up, 18% of the patients had fever, 23% cough, and 2% failure to thrive; 59% of the school-age children had missed a median of 5 classroom days. By 6 months, however, only 16% of children were still coughing, and 30% of school-age children had missed an average of 2 days of school since the 1-month evaluation. None of the children were experiencing fever or failure to thrive at late follow-up.

At 1 month post discharge, 7 of 20 children had abnormal spirometry, defined as a forced expiratory volume in 1 second that is 80% or less of predicted. Of the 82 children, 24 had persistent abnormalities on chest x-ray, mostly effusion, pneumatocele, or abscess. Twelve of 68 parents rated their child’s health-related quality of life as abnormal based on a Peds-QL score more than 1 standard deviation below the normal population.

By 6 months, only one child had abnormal spirometry and three had persistent chest x-ray abnormalities. At 1 year, these abnormalities had resolved in three patients, while the fourth was lost to follow-up.

Moreover, at 6 months, parents rated their child’s quality of life on the Peds-QL as similar to that in 8,430 healthy historical controls and significantly better than were the scores for 157 children with asthma, according to Dr. Cohen.

He declared having no financial conflicts of interest.

Study Finds Early Onset of Puberty in Girls

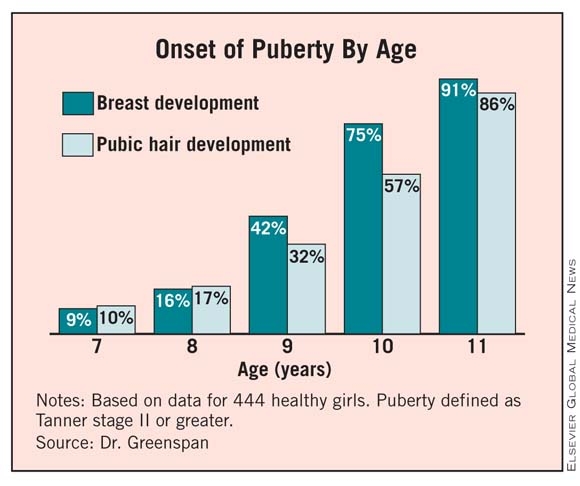

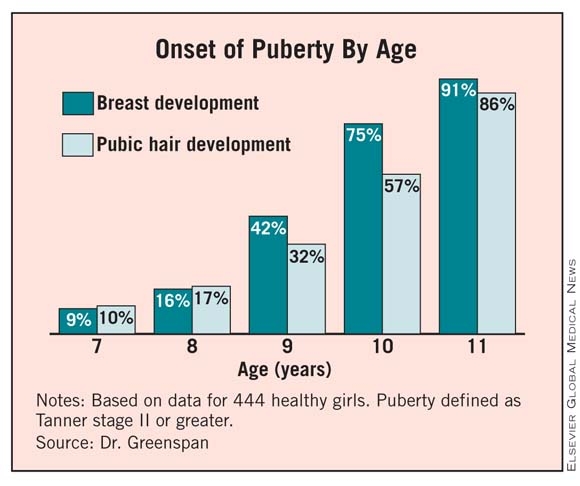

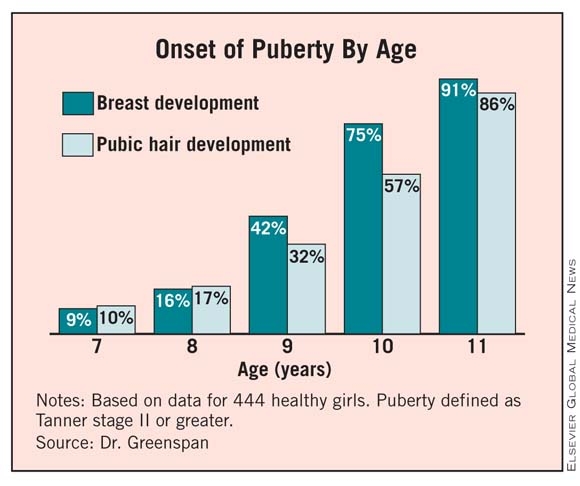

DENVER – A majority of girls start puberty before age 10 years, according to researchers for a longitudinal study who found young ages for onset of breast and pubic hair development.

Tanner stage II breast development ranged from 9% of 7-year-old girls to 91% of 11-year-olds in this ongoing study of 444 healthy girls. Similarly, 10% of the 7-year-olds had Tanner stage II pubic hair development, as did 86% of the 11-year-olds. A total of 75% achieved Tanner stage II or greater breast development, and 57% achieved Tanner stage II or greater pubic hair development by age 10 years.

"Observations from this longitudinal cohort study confirm that girls’ pubertal development is starting earlier," Dr. Louise C. Greenspan said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, where she presented data for the first 5 years. Data from the first 2 years were previously published (Pediatrics 2010;126:e583-90).

|

A higher body mass index (BMI) and black ethnicity were associated with earlier onset of puberty, said Dr. Greenspan, a pediatric endocrinologist at the Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Medical Center. Girls were aged 6-8 years in 2005 or 2006 when they were initially enrolled in the Cohort Study of Young Girls’ Nutrition, Environment, and Transitions (CYGNET). Participants are 42% white, 24% Hispanic, 22% black, and 12% Asian, "a historically understudied group in this field."

"When we break this down by ethnicity ... not surprisingly, the black girls were earlier for all stages of breast development," Dr. Greenspan said, whereas white girls were the later bloomers at all stages of breast development.

The black girls also were earlier for all stages of pubic hair development. By age 11 years, for example, almost 98% were at Tanner stage II or higher. "The difference here is that the Asian girls were the later girls, basically all the way along, for pubic hair development," Dr. Greenspan said.

Girls who were below the 85th percentile for BMI were the later bloomers at all stages of pubertal development, Dr. Greenspan said. She added that when girls had a high body-fat percentage on bioelectrical impedance analysis, examiners palpated them to try to distinguish fat from glandular tissue. In a similar fashion, the slimmer girls were the later developers of pubic hair at Tanner stage II.

Breast-development findings in the current study are similar to those reported by investigators for American Academy of Pediatrics’ Pediatric Research in Office Settings (PROS) research network.

"For breast stage, there were some variations, but it was pretty much on par," Dr. Greenspan said. However, for pubic hair, CYGNET participants had earlier rates of development versus those in the PROS cross-sectional study (Pediatrics 1997;99:505-12).

A meeting attendee asked Dr. Greenspan if she and her associates assessed BMI differences by ethnicity.

"We don’t have the power in our smaller cohort," she said. "We are looking at that in the larger 1,200 cohort."

The Relation Between Puberty and Breast Cancer

In addition to the San Francisco cohort, investigators are prospectively evaluating girls in Cincinnati and New York as part of the larger Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Program. This federally funded study is assessing the effect of early environmental exposures that could potentially trigger earlier pubertal development, and thus increase the risk of breast cancer. "We know that age of menarche is a risk for breast cancer," Dr. Greenspan said.

"There is growing evidence that timing of exposures may be important to determining breast cancer risk, and puberty may be an important window of susceptibility," Dr. Greenspan said.

The CYGNET study just entered year 6. Annual visits include a physical examination, evaluation of urine and blood samples, activity measurements, food recall, and questionnaires. One expert instructed all research staff to rate Tanner sexual maturity ratings.

Evaluation of tempo and menarche is a future goal for the CYGNET researchers. By the end of year 5, fewer than 20 girls have had menarche, Dr. Greenspan said.

"That is not enough yet to report. We are following the girls through at least year 10," so those data will be coming out, she added.

The Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Program is funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Greenspan said that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

DENVER – A majority of girls start puberty before age 10 years, according to researchers for a longitudinal study who found young ages for onset of breast and pubic hair development.

Tanner stage II breast development ranged from 9% of 7-year-old girls to 91% of 11-year-olds in this ongoing study of 444 healthy girls. Similarly, 10% of the 7-year-olds had Tanner stage II pubic hair development, as did 86% of the 11-year-olds. A total of 75% achieved Tanner stage II or greater breast development, and 57% achieved Tanner stage II or greater pubic hair development by age 10 years.

"Observations from this longitudinal cohort study confirm that girls’ pubertal development is starting earlier," Dr. Louise C. Greenspan said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, where she presented data for the first 5 years. Data from the first 2 years were previously published (Pediatrics 2010;126:e583-90).

|

A higher body mass index (BMI) and black ethnicity were associated with earlier onset of puberty, said Dr. Greenspan, a pediatric endocrinologist at the Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Medical Center. Girls were aged 6-8 years in 2005 or 2006 when they were initially enrolled in the Cohort Study of Young Girls’ Nutrition, Environment, and Transitions (CYGNET). Participants are 42% white, 24% Hispanic, 22% black, and 12% Asian, "a historically understudied group in this field."

"When we break this down by ethnicity ... not surprisingly, the black girls were earlier for all stages of breast development," Dr. Greenspan said, whereas white girls were the later bloomers at all stages of breast development.

The black girls also were earlier for all stages of pubic hair development. By age 11 years, for example, almost 98% were at Tanner stage II or higher. "The difference here is that the Asian girls were the later girls, basically all the way along, for pubic hair development," Dr. Greenspan said.

Girls who were below the 85th percentile for BMI were the later bloomers at all stages of pubertal development, Dr. Greenspan said. She added that when girls had a high body-fat percentage on bioelectrical impedance analysis, examiners palpated them to try to distinguish fat from glandular tissue. In a similar fashion, the slimmer girls were the later developers of pubic hair at Tanner stage II.

Breast-development findings in the current study are similar to those reported by investigators for American Academy of Pediatrics’ Pediatric Research in Office Settings (PROS) research network.

"For breast stage, there were some variations, but it was pretty much on par," Dr. Greenspan said. However, for pubic hair, CYGNET participants had earlier rates of development versus those in the PROS cross-sectional study (Pediatrics 1997;99:505-12).

A meeting attendee asked Dr. Greenspan if she and her associates assessed BMI differences by ethnicity.

"We don’t have the power in our smaller cohort," she said. "We are looking at that in the larger 1,200 cohort."

The Relation Between Puberty and Breast Cancer

In addition to the San Francisco cohort, investigators are prospectively evaluating girls in Cincinnati and New York as part of the larger Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Program. This federally funded study is assessing the effect of early environmental exposures that could potentially trigger earlier pubertal development, and thus increase the risk of breast cancer. "We know that age of menarche is a risk for breast cancer," Dr. Greenspan said.

"There is growing evidence that timing of exposures may be important to determining breast cancer risk, and puberty may be an important window of susceptibility," Dr. Greenspan said.

The CYGNET study just entered year 6. Annual visits include a physical examination, evaluation of urine and blood samples, activity measurements, food recall, and questionnaires. One expert instructed all research staff to rate Tanner sexual maturity ratings.

Evaluation of tempo and menarche is a future goal for the CYGNET researchers. By the end of year 5, fewer than 20 girls have had menarche, Dr. Greenspan said.

"That is not enough yet to report. We are following the girls through at least year 10," so those data will be coming out, she added.

The Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Program is funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Greenspan said that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

DENVER – A majority of girls start puberty before age 10 years, according to researchers for a longitudinal study who found young ages for onset of breast and pubic hair development.

Tanner stage II breast development ranged from 9% of 7-year-old girls to 91% of 11-year-olds in this ongoing study of 444 healthy girls. Similarly, 10% of the 7-year-olds had Tanner stage II pubic hair development, as did 86% of the 11-year-olds. A total of 75% achieved Tanner stage II or greater breast development, and 57% achieved Tanner stage II or greater pubic hair development by age 10 years.

"Observations from this longitudinal cohort study confirm that girls’ pubertal development is starting earlier," Dr. Louise C. Greenspan said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, where she presented data for the first 5 years. Data from the first 2 years were previously published (Pediatrics 2010;126:e583-90).

|

A higher body mass index (BMI) and black ethnicity were associated with earlier onset of puberty, said Dr. Greenspan, a pediatric endocrinologist at the Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Medical Center. Girls were aged 6-8 years in 2005 or 2006 when they were initially enrolled in the Cohort Study of Young Girls’ Nutrition, Environment, and Transitions (CYGNET). Participants are 42% white, 24% Hispanic, 22% black, and 12% Asian, "a historically understudied group in this field."

"When we break this down by ethnicity ... not surprisingly, the black girls were earlier for all stages of breast development," Dr. Greenspan said, whereas white girls were the later bloomers at all stages of breast development.

The black girls also were earlier for all stages of pubic hair development. By age 11 years, for example, almost 98% were at Tanner stage II or higher. "The difference here is that the Asian girls were the later girls, basically all the way along, for pubic hair development," Dr. Greenspan said.

Girls who were below the 85th percentile for BMI were the later bloomers at all stages of pubertal development, Dr. Greenspan said. She added that when girls had a high body-fat percentage on bioelectrical impedance analysis, examiners palpated them to try to distinguish fat from glandular tissue. In a similar fashion, the slimmer girls were the later developers of pubic hair at Tanner stage II.

Breast-development findings in the current study are similar to those reported by investigators for American Academy of Pediatrics’ Pediatric Research in Office Settings (PROS) research network.

"For breast stage, there were some variations, but it was pretty much on par," Dr. Greenspan said. However, for pubic hair, CYGNET participants had earlier rates of development versus those in the PROS cross-sectional study (Pediatrics 1997;99:505-12).

A meeting attendee asked Dr. Greenspan if she and her associates assessed BMI differences by ethnicity.

"We don’t have the power in our smaller cohort," she said. "We are looking at that in the larger 1,200 cohort."

The Relation Between Puberty and Breast Cancer

In addition to the San Francisco cohort, investigators are prospectively evaluating girls in Cincinnati and New York as part of the larger Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Program. This federally funded study is assessing the effect of early environmental exposures that could potentially trigger earlier pubertal development, and thus increase the risk of breast cancer. "We know that age of menarche is a risk for breast cancer," Dr. Greenspan said.

"There is growing evidence that timing of exposures may be important to determining breast cancer risk, and puberty may be an important window of susceptibility," Dr. Greenspan said.

The CYGNET study just entered year 6. Annual visits include a physical examination, evaluation of urine and blood samples, activity measurements, food recall, and questionnaires. One expert instructed all research staff to rate Tanner sexual maturity ratings.

Evaluation of tempo and menarche is a future goal for the CYGNET researchers. By the end of year 5, fewer than 20 girls have had menarche, Dr. Greenspan said.

"That is not enough yet to report. We are following the girls through at least year 10," so those data will be coming out, she added.

The Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Program is funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Greenspan said that she had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Major Finding: A total of 75% achieved Tanner stage II or greater breast development and 57% achieved Tanner stage II or greater pubic hair development by age 10 years.

Data Source: The 5-year data for 444 healthy girls from the ongoing, longitudinal CYGNET.

Disclosures: Dr. Greenspan said she had no relevant financial disclosures. The investigation is part of a larger study sponsored by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Cancer Institute.

Discordant Antibiotic Therapy for UTI Stretches Hospital Stays

DENVER – Discordant antibiotic therapy occurred in 11% of a large series of children admitted for urinary tract infection at five major freestanding children’s hospitals.

Antibiotic discordance occurs when the causative organism demonstrates in vitro nonsusceptibility to the empiric antibiotic therapy that was administered before the urine culture results became available. In this five-hospital study, discordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a significantly increased length of stay, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

"For most of the cases of antibiotic discordance, the antibiotics were clinically appropriate in the setting of presumed [urinary tract infection], but the bacteria themselves were more resistant," said Dr. Jerardi of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

The implication is: Know your local uropathogen resistance patterns and align the initial empiric antibiotic therapy accordingly, she said.

The study involved 192 patients aged 3 days to 18 years who were hospitalized for urinary tract infection (UTI), with a median 3-day length of stay. The major uropathogens identified were Escherichia coli in 66% of cases, Klebsiella species in 11%, Enterococcus species in 6%, and Pseudomonas species in 5%. Mixed-organism UTIs accounted for 5% of the total.

The most common initial antibiotics were third-generation cephalosporins in 39% of cases, followed by ampicillin plus a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin in 16%, and ampicillin plus gentamicin in 11%, with other agents being employed in the low single digits.

Antibiotic discordance was most frequent in UTIs caused by Klebsiella species, with a 7% rate. The other causative organisms where antibiotic discordance was common were mixed-organism infections, with a 5% antibiotic discordance rate, and E. coli and enterococcus, each with a 3% rate.

There were no significant differences between the concordant and discordant groups in terms of patient age, sex, chronic care conditions, presence of vesicoureteral reflux, or the use of prophylactic antibiotics. In a multivariate linear regression analysis adjusted for these factors, length of stay was a median 1.8 days shorter for patients treated initially with a concordant antibiotic. For the two-thirds of patients with an E. coli UTI, concordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a 3.1-day shorter stay.

As UTI is a common condition – accounting for 2% of all pediatric hospitalizations – selecting an initial antibiotic based on local uropathogen resistance patterns could result in significant cost savings as well as reduced exposure to unnecessary antibiotics, Dr. Jerardi observed.

She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Antibiotic discordance, UTI, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi, the Pediatric Academic Societies, bacteria, uropathogen resistance patterns, empiric antibiotic therapy, uropathogens, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, cephalosporins, ampicillin,

DENVER – Discordant antibiotic therapy occurred in 11% of a large series of children admitted for urinary tract infection at five major freestanding children’s hospitals.

Antibiotic discordance occurs when the causative organism demonstrates in vitro nonsusceptibility to the empiric antibiotic therapy that was administered before the urine culture results became available. In this five-hospital study, discordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a significantly increased length of stay, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

"For most of the cases of antibiotic discordance, the antibiotics were clinically appropriate in the setting of presumed [urinary tract infection], but the bacteria themselves were more resistant," said Dr. Jerardi of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

The implication is: Know your local uropathogen resistance patterns and align the initial empiric antibiotic therapy accordingly, she said.

The study involved 192 patients aged 3 days to 18 years who were hospitalized for urinary tract infection (UTI), with a median 3-day length of stay. The major uropathogens identified were Escherichia coli in 66% of cases, Klebsiella species in 11%, Enterococcus species in 6%, and Pseudomonas species in 5%. Mixed-organism UTIs accounted for 5% of the total.

The most common initial antibiotics were third-generation cephalosporins in 39% of cases, followed by ampicillin plus a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin in 16%, and ampicillin plus gentamicin in 11%, with other agents being employed in the low single digits.

Antibiotic discordance was most frequent in UTIs caused by Klebsiella species, with a 7% rate. The other causative organisms where antibiotic discordance was common were mixed-organism infections, with a 5% antibiotic discordance rate, and E. coli and enterococcus, each with a 3% rate.

There were no significant differences between the concordant and discordant groups in terms of patient age, sex, chronic care conditions, presence of vesicoureteral reflux, or the use of prophylactic antibiotics. In a multivariate linear regression analysis adjusted for these factors, length of stay was a median 1.8 days shorter for patients treated initially with a concordant antibiotic. For the two-thirds of patients with an E. coli UTI, concordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a 3.1-day shorter stay.

As UTI is a common condition – accounting for 2% of all pediatric hospitalizations – selecting an initial antibiotic based on local uropathogen resistance patterns could result in significant cost savings as well as reduced exposure to unnecessary antibiotics, Dr. Jerardi observed.

She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

DENVER – Discordant antibiotic therapy occurred in 11% of a large series of children admitted for urinary tract infection at five major freestanding children’s hospitals.

Antibiotic discordance occurs when the causative organism demonstrates in vitro nonsusceptibility to the empiric antibiotic therapy that was administered before the urine culture results became available. In this five-hospital study, discordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a significantly increased length of stay, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

"For most of the cases of antibiotic discordance, the antibiotics were clinically appropriate in the setting of presumed [urinary tract infection], but the bacteria themselves were more resistant," said Dr. Jerardi of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

The implication is: Know your local uropathogen resistance patterns and align the initial empiric antibiotic therapy accordingly, she said.

The study involved 192 patients aged 3 days to 18 years who were hospitalized for urinary tract infection (UTI), with a median 3-day length of stay. The major uropathogens identified were Escherichia coli in 66% of cases, Klebsiella species in 11%, Enterococcus species in 6%, and Pseudomonas species in 5%. Mixed-organism UTIs accounted for 5% of the total.

The most common initial antibiotics were third-generation cephalosporins in 39% of cases, followed by ampicillin plus a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin in 16%, and ampicillin plus gentamicin in 11%, with other agents being employed in the low single digits.

Antibiotic discordance was most frequent in UTIs caused by Klebsiella species, with a 7% rate. The other causative organisms where antibiotic discordance was common were mixed-organism infections, with a 5% antibiotic discordance rate, and E. coli and enterococcus, each with a 3% rate.

There were no significant differences between the concordant and discordant groups in terms of patient age, sex, chronic care conditions, presence of vesicoureteral reflux, or the use of prophylactic antibiotics. In a multivariate linear regression analysis adjusted for these factors, length of stay was a median 1.8 days shorter for patients treated initially with a concordant antibiotic. For the two-thirds of patients with an E. coli UTI, concordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a 3.1-day shorter stay.

As UTI is a common condition – accounting for 2% of all pediatric hospitalizations – selecting an initial antibiotic based on local uropathogen resistance patterns could result in significant cost savings as well as reduced exposure to unnecessary antibiotics, Dr. Jerardi observed.

She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Antibiotic discordance, UTI, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi, the Pediatric Academic Societies, bacteria, uropathogen resistance patterns, empiric antibiotic therapy, uropathogens, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, cephalosporins, ampicillin,

Antibiotic discordance, UTI, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi, the Pediatric Academic Societies, bacteria, uropathogen resistance patterns, empiric antibiotic therapy, uropathogens, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, cephalosporins, ampicillin,

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Major Finding: Discordant antibiotic therapy occurred in 11% of children admitted for urinary tract infection.

Data Source: A series of 192 patients aged 3 days to 18 years who were hospitalized for UTI at five children’s hospitals.

Disclosures: Dr. Jerardi reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Discordant Antibiotic Therapy for UTI Stretches Hospital Stays

DENVER – Discordant antibiotic therapy occurred in 11% of a large series of children admitted for urinary tract infection at five major freestanding children’s hospitals.

Antibiotic discordance occurs when the causative organism demonstrates in vitro nonsusceptibility to the empiric antibiotic therapy that was administered before the urine culture results became available. In this five-hospital study, discordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a significantly increased length of stay, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

"For most of the cases of antibiotic discordance, the antibiotics were clinically appropriate in the setting of presumed [urinary tract infection], but the bacteria themselves were more resistant," said Dr. Jerardi of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

The implication is: Know your local uropathogen resistance patterns and align the initial empiric antibiotic therapy accordingly, she said.

The study involved 192 patients aged 3 days to 18 years who were hospitalized for urinary tract infection (UTI), with a median 3-day length of stay. The major uropathogens identified were Escherichia coli in 66% of cases, Klebsiella species in 11%, Enterococcus species in 6%, and Pseudomonas species in 5%. Mixed-organism UTIs accounted for 5% of the total.

The most common initial antibiotics were third-generation cephalosporins in 39% of cases, followed by ampicillin plus a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin in 16%, and ampicillin plus gentamicin in 11%, with other agents being employed in the low single digits.

Antibiotic discordance was most frequent in UTIs caused by Klebsiella species, with a 7% rate. The other causative organisms where antibiotic discordance was common were mixed-organism infections, with a 5% antibiotic discordance rate, and E. coli and enterococcus, each with a 3% rate.

There were no significant differences between the concordant and discordant groups in terms of patient age, sex, chronic care conditions, presence of vesicoureteral reflux, or the use of prophylactic antibiotics. In a multivariate linear regression analysis adjusted for these factors, length of stay was a median 1.8 days shorter for patients treated initially with a concordant antibiotic. For the two-thirds of patients with an E. coli UTI, concordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a 3.1-day shorter stay.

As UTI is a common condition – accounting for 2% of all pediatric hospitalizations – selecting an initial antibiotic based on local uropathogen resistance patterns could result in significant cost savings as well as reduced exposure to unnecessary antibiotics, Dr. Jerardi observed.

She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Antibiotic discordance, UTI, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi, the Pediatric Academic Societies, bacteria, uropathogen resistance patterns, empiric antibiotic therapy, uropathogens, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, cephalosporins, ampicillin,

DENVER – Discordant antibiotic therapy occurred in 11% of a large series of children admitted for urinary tract infection at five major freestanding children’s hospitals.

Antibiotic discordance occurs when the causative organism demonstrates in vitro nonsusceptibility to the empiric antibiotic therapy that was administered before the urine culture results became available. In this five-hospital study, discordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a significantly increased length of stay, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

"For most of the cases of antibiotic discordance, the antibiotics were clinically appropriate in the setting of presumed [urinary tract infection], but the bacteria themselves were more resistant," said Dr. Jerardi of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

The implication is: Know your local uropathogen resistance patterns and align the initial empiric antibiotic therapy accordingly, she said.

The study involved 192 patients aged 3 days to 18 years who were hospitalized for urinary tract infection (UTI), with a median 3-day length of stay. The major uropathogens identified were Escherichia coli in 66% of cases, Klebsiella species in 11%, Enterococcus species in 6%, and Pseudomonas species in 5%. Mixed-organism UTIs accounted for 5% of the total.

The most common initial antibiotics were third-generation cephalosporins in 39% of cases, followed by ampicillin plus a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin in 16%, and ampicillin plus gentamicin in 11%, with other agents being employed in the low single digits.

Antibiotic discordance was most frequent in UTIs caused by Klebsiella species, with a 7% rate. The other causative organisms where antibiotic discordance was common were mixed-organism infections, with a 5% antibiotic discordance rate, and E. coli and enterococcus, each with a 3% rate.

There were no significant differences between the concordant and discordant groups in terms of patient age, sex, chronic care conditions, presence of vesicoureteral reflux, or the use of prophylactic antibiotics. In a multivariate linear regression analysis adjusted for these factors, length of stay was a median 1.8 days shorter for patients treated initially with a concordant antibiotic. For the two-thirds of patients with an E. coli UTI, concordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a 3.1-day shorter stay.

As UTI is a common condition – accounting for 2% of all pediatric hospitalizations – selecting an initial antibiotic based on local uropathogen resistance patterns could result in significant cost savings as well as reduced exposure to unnecessary antibiotics, Dr. Jerardi observed.

She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

DENVER – Discordant antibiotic therapy occurred in 11% of a large series of children admitted for urinary tract infection at five major freestanding children’s hospitals.

Antibiotic discordance occurs when the causative organism demonstrates in vitro nonsusceptibility to the empiric antibiotic therapy that was administered before the urine culture results became available. In this five-hospital study, discordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a significantly increased length of stay, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

"For most of the cases of antibiotic discordance, the antibiotics were clinically appropriate in the setting of presumed [urinary tract infection], but the bacteria themselves were more resistant," said Dr. Jerardi of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

The implication is: Know your local uropathogen resistance patterns and align the initial empiric antibiotic therapy accordingly, she said.

The study involved 192 patients aged 3 days to 18 years who were hospitalized for urinary tract infection (UTI), with a median 3-day length of stay. The major uropathogens identified were Escherichia coli in 66% of cases, Klebsiella species in 11%, Enterococcus species in 6%, and Pseudomonas species in 5%. Mixed-organism UTIs accounted for 5% of the total.

The most common initial antibiotics were third-generation cephalosporins in 39% of cases, followed by ampicillin plus a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin in 16%, and ampicillin plus gentamicin in 11%, with other agents being employed in the low single digits.

Antibiotic discordance was most frequent in UTIs caused by Klebsiella species, with a 7% rate. The other causative organisms where antibiotic discordance was common were mixed-organism infections, with a 5% antibiotic discordance rate, and E. coli and enterococcus, each with a 3% rate.

There were no significant differences between the concordant and discordant groups in terms of patient age, sex, chronic care conditions, presence of vesicoureteral reflux, or the use of prophylactic antibiotics. In a multivariate linear regression analysis adjusted for these factors, length of stay was a median 1.8 days shorter for patients treated initially with a concordant antibiotic. For the two-thirds of patients with an E. coli UTI, concordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a 3.1-day shorter stay.

As UTI is a common condition – accounting for 2% of all pediatric hospitalizations – selecting an initial antibiotic based on local uropathogen resistance patterns could result in significant cost savings as well as reduced exposure to unnecessary antibiotics, Dr. Jerardi observed.

She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Antibiotic discordance, UTI, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi, the Pediatric Academic Societies, bacteria, uropathogen resistance patterns, empiric antibiotic therapy, uropathogens, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, cephalosporins, ampicillin,

Antibiotic discordance, UTI, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi, the Pediatric Academic Societies, bacteria, uropathogen resistance patterns, empiric antibiotic therapy, uropathogens, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, cephalosporins, ampicillin,

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Discordant Antibiotic Therapy for UTI Stretches Hospital Stays

DENVER – Discordant antibiotic therapy occurred in 11% of a large series of children admitted for urinary tract infection at five major freestanding children’s hospitals.

Antibiotic discordance occurs when the causative organism demonstrates in vitro nonsusceptibility to the empiric antibiotic therapy that was administered before the urine culture results became available. In this five-hospital study, discordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a significantly increased length of stay, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

"For most of the cases of antibiotic discordance, the antibiotics were clinically appropriate in the setting of presumed [urinary tract infection], but the bacteria themselves were more resistant," said Dr. Jerardi of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

The implication is: Know your local uropathogen resistance patterns and align the initial empiric antibiotic therapy accordingly, she said.

The study involved 192 patients aged 3 days to 18 years who were hospitalized for urinary tract infection (UTI), with a median 3-day length of stay. The major uropathogens identified were Escherichia coli in 66% of cases, Klebsiella species in 11%, Enterococcus species in 6%, and Pseudomonas species in 5%. Mixed-organism UTIs accounted for 5% of the total.

The most common initial antibiotics were third-generation cephalosporins in 39% of cases, followed by ampicillin plus a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin in 16%, and ampicillin plus gentamicin in 11%, with other agents being employed in the low single digits.

Antibiotic discordance was most frequent in UTIs caused by Klebsiella species, with a 7% rate. The other causative organisms where antibiotic discordance was common were mixed-organism infections, with a 5% antibiotic discordance rate, and E. coli and enterococcus, each with a 3% rate.

There were no significant differences between the concordant and discordant groups in terms of patient age, sex, chronic care conditions, presence of vesicoureteral reflux, or the use of prophylactic antibiotics. In a multivariate linear regression analysis adjusted for these factors, length of stay was a median 1.8 days shorter for patients treated initially with a concordant antibiotic. For the two-thirds of patients with an E. coli UTI, concordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a 3.1-day shorter stay.

As UTI is a common condition – accounting for 2% of all pediatric hospitalizations – selecting an initial antibiotic based on local uropathogen resistance patterns could result in significant cost savings as well as reduced exposure to unnecessary antibiotics, Dr. Jerardi observed.

She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Antibiotic discordance, UTI, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi, the Pediatric Academic Societies, bacteria, uropathogen resistance patterns, empiric antibiotic therapy, uropathogens, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, cephalosporins, ampicillin,

DENVER – Discordant antibiotic therapy occurred in 11% of a large series of children admitted for urinary tract infection at five major freestanding children’s hospitals.

Antibiotic discordance occurs when the causative organism demonstrates in vitro nonsusceptibility to the empiric antibiotic therapy that was administered before the urine culture results became available. In this five-hospital study, discordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a significantly increased length of stay, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

"For most of the cases of antibiotic discordance, the antibiotics were clinically appropriate in the setting of presumed [urinary tract infection], but the bacteria themselves were more resistant," said Dr. Jerardi of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

The implication is: Know your local uropathogen resistance patterns and align the initial empiric antibiotic therapy accordingly, she said.

The study involved 192 patients aged 3 days to 18 years who were hospitalized for urinary tract infection (UTI), with a median 3-day length of stay. The major uropathogens identified were Escherichia coli in 66% of cases, Klebsiella species in 11%, Enterococcus species in 6%, and Pseudomonas species in 5%. Mixed-organism UTIs accounted for 5% of the total.

The most common initial antibiotics were third-generation cephalosporins in 39% of cases, followed by ampicillin plus a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin in 16%, and ampicillin plus gentamicin in 11%, with other agents being employed in the low single digits.

Antibiotic discordance was most frequent in UTIs caused by Klebsiella species, with a 7% rate. The other causative organisms where antibiotic discordance was common were mixed-organism infections, with a 5% antibiotic discordance rate, and E. coli and enterococcus, each with a 3% rate.

There were no significant differences between the concordant and discordant groups in terms of patient age, sex, chronic care conditions, presence of vesicoureteral reflux, or the use of prophylactic antibiotics. In a multivariate linear regression analysis adjusted for these factors, length of stay was a median 1.8 days shorter for patients treated initially with a concordant antibiotic. For the two-thirds of patients with an E. coli UTI, concordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a 3.1-day shorter stay.

As UTI is a common condition – accounting for 2% of all pediatric hospitalizations – selecting an initial antibiotic based on local uropathogen resistance patterns could result in significant cost savings as well as reduced exposure to unnecessary antibiotics, Dr. Jerardi observed.

She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

DENVER – Discordant antibiotic therapy occurred in 11% of a large series of children admitted for urinary tract infection at five major freestanding children’s hospitals.

Antibiotic discordance occurs when the causative organism demonstrates in vitro nonsusceptibility to the empiric antibiotic therapy that was administered before the urine culture results became available. In this five-hospital study, discordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a significantly increased length of stay, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi reported at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

"For most of the cases of antibiotic discordance, the antibiotics were clinically appropriate in the setting of presumed [urinary tract infection], but the bacteria themselves were more resistant," said Dr. Jerardi of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

The implication is: Know your local uropathogen resistance patterns and align the initial empiric antibiotic therapy accordingly, she said.

The study involved 192 patients aged 3 days to 18 years who were hospitalized for urinary tract infection (UTI), with a median 3-day length of stay. The major uropathogens identified were Escherichia coli in 66% of cases, Klebsiella species in 11%, Enterococcus species in 6%, and Pseudomonas species in 5%. Mixed-organism UTIs accounted for 5% of the total.

The most common initial antibiotics were third-generation cephalosporins in 39% of cases, followed by ampicillin plus a third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin in 16%, and ampicillin plus gentamicin in 11%, with other agents being employed in the low single digits.

Antibiotic discordance was most frequent in UTIs caused by Klebsiella species, with a 7% rate. The other causative organisms where antibiotic discordance was common were mixed-organism infections, with a 5% antibiotic discordance rate, and E. coli and enterococcus, each with a 3% rate.

There were no significant differences between the concordant and discordant groups in terms of patient age, sex, chronic care conditions, presence of vesicoureteral reflux, or the use of prophylactic antibiotics. In a multivariate linear regression analysis adjusted for these factors, length of stay was a median 1.8 days shorter for patients treated initially with a concordant antibiotic. For the two-thirds of patients with an E. coli UTI, concordant antibiotic therapy was associated with a 3.1-day shorter stay.

As UTI is a common condition – accounting for 2% of all pediatric hospitalizations – selecting an initial antibiotic based on local uropathogen resistance patterns could result in significant cost savings as well as reduced exposure to unnecessary antibiotics, Dr. Jerardi observed.

She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Antibiotic discordance, UTI, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi, the Pediatric Academic Societies, bacteria, uropathogen resistance patterns, empiric antibiotic therapy, uropathogens, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, cephalosporins, ampicillin,

Antibiotic discordance, UTI, Dr. Karen E. Jerardi, the Pediatric Academic Societies, bacteria, uropathogen resistance patterns, empiric antibiotic therapy, uropathogens, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, cephalosporins, ampicillin,

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Major Finding: Discordant antibiotic therapy occurred in 11% of children admitted for urinary tract infection.

Data Source: A series of 192 patients aged 3 days to 18 years who were hospitalized for UTI at five children’s hospitals.

Disclosures: Dr. Jerardi reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Depressive Symptoms: Like Father, Like Child

DENVER – Living with a father who has depressive symptoms or other mental health problems is independently associated with increased rates of emotional or behavioral difficulties in their children, a study of more than 20,000 U.S. youths shows.

These study data identify paternal mental health problems as a previously unrecognized threat to children’s mental health, David G. Rosenthal declared in presenting the results at the meeting.

Extensive literature has documented that maternal depression has multiple adverse impacts on child outcomes, including low birthweight, anxiety and depression, behavioral problems, and poor school performance.

"In contrast, there is a profound paucity of research regarding possible associations between paternal mental health and depressive symptoms and childhood health functioning," commented Mr. Rosenthal, a medical student at New York University. "In this study, we have documented that fathers are extremely important to the behavioral and emotional well being of the child, but they remain absent in many policy decisions about child health. This must be addressed."

His study also demonstrated that the adverse impact on children’s behavioral and emotional functioning is compounded when both the mother and father have mental health problems. For example, in homes where both parents experienced depressive symptoms, fully 25% of children had emotional or behavioral problems, a rate more than fourfold greater than when neither parent was affected.

The study used data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey – a nationally representative sample of the U.S. population – for the years 2004-2008 on 20,260 children aged 5-17 years and their parents. The Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS) was used to measure emotional and behavioral problems in the children, Short Form-12 (SF-12) was used to assess parental mental and physical health, and parental depressive symptoms were evaluated via the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2).

As seen in other studies, higher rates of significant behavioral or emotional problems, as defined by a CIS score of 16 or higher, were seen in children who were older, male, and white.