User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Ten ways docs are cutting costs and saving money

“Some of our physician clients have seen their income decrease by as much as 50%,” says Joel Greenwald, MD, CEO of Greenwald Wealth Management in St. Louis Park, Minnesota. “Many physicians had previously figured that whatever financial obligations they had wouldn’t be a problem because whatever amount they were making would continue, and if there were a decline it would be gradual.” However, assumption is now creating financial strain for many doctors.

Vikram Tarugu, MD, a gastroenterologist and CEO of Detox of South Florida in Okeechobee, Florida, says he has watched his budget for years, but has become even more careful with his spending in the past few months.

“It has helped me a lot to adjust to the new normal when it comes to the financial side of things,” Dr. Tarugu said. “Patients aren’t coming in as much as they used to, so my income has really been affected.”

Primary care physicians have seen a 55% decrease in revenue and a 20%-30% decrease in patient volume as a result of COVID-19. The impact has been even more severe for specialists. Even for physicians whose practices remain busy and whose family members haven’t lost their jobs or income, broader concerns about the economy may be reason enough for physicians to adopt cost-cutting measures.

In Medscape’s Physician Compensation Report 2020, we asked physicians to share their best cost-cutting tips. Many illustrate the lengths to which physicians are going to conserve money.

Here’s a look at some of the advice they shared, along with guidance from experts on how to make it work for you:

1. Create a written budget, even if you think it’s pointless.

Physicians said their most important piece of advice includes the following: “Use a formal budget to track progress,” “write out a budget,” “plan intermittent/large expenses in advance,” “Make sure all expenses are paid before you spend on leisure.”

Nearly 7 in 10 physicians say they have a budget for personal expenses, yet only one-quarter of those who do have a formal, written budget. Writing out a spending plan is key to being intentional about your spending, making sure that you’re living within your means, and identifying areas in which you may be able to cut back.

“Financial planning is all about cash flow, and everybody should know the amount of money coming in, how much is going out, and the difference between the two,” says Amy Guerich, a partner with Stepp & Rothwell, a Kansas City–based financial planning firm. “That’s important in good times, but it’s even more important now when we see physicians taking pay cuts.”

Many physicians have found that budget apps or software programs are easier to work with than anticipated; some even walk you through the process of creating a budget. To get the most out of the apps, you’ll need to check them regularly and make changes based on their data.

“Sometimes there’s this false belief that just by signing up, you are automatically going to be better at budgeting,” says Scott Snider, CFP, a certified financial planner and partner with Mellen Money Management in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida. “Basically, these apps are a great way to identify problem areas of spending. We have a tendency as humans to underestimate how much we spend on things like Starbucks, dining out, and Amazon shopping.”

One of the doctors’ tips that requires the most willpower is to “pay all expenses before spending on leisure.” That’s because we live in an instant gratification world, and want everything right away, Ms. Guerich said.

“I also think there’s an element of ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ and pressure associated with this profession,” she said. “The stereotype is that physicians are high-income earners so ‘We should be able to do that’ or ‘Mom and dad are doctors, so they can afford it.’ “

Creating and then revisiting your budget progress on a monthly or quarterly basis can give you a feeling of accomplishment and keep you motivated to stay with it.

Keep in mind that budgeting is a continual process rather than a singular event, and you’ll likely adjust it over time as your income and goals change.

2. Save more as you earn more.

Respondents to our Physician Compensation Report gave the following recommendations: “Pay yourself first,” “I put half of my bonus into an investment account no matter how much it is,” “I allocate extra money and put it into a savings account.”

Dr. Greenwald said, “I have a rule that every client needs to be saving 20% of their gross income toward retirement, including whatever the employer is putting in.”

Putting a portion of every paycheck into savings is key to making progress toward financial goals. Start by building an emergency fund with at least 3-6 months’ worth of expenses in it and making sure you’re saving at least enough for retirement to get any potential employer match.

Mr. Snider suggests increasing the percentage you save every time you get a raise.

“The thought behind that strategy is that when a doctor receives a pay raise – even if it’s just a cost-of-living raise of 3% – an extra 1% saved doesn’t reduce their take-home pay year-over-year,” he says. “In fact, they still take home more money, and they save more money. Win-win.”

3. Focus on paying down your debt.

Physicians told us how they were working to pay down debt with the following recommendations: “Accelerate debt reduction,” “I make additional principal payment to our home mortgage,” “We are aggressively attacking our remaining student loans.”

Reducing or eliminating debt is key to increasing cash flow, which can make it easier to meet all of your other financial goals. One-quarter of physicians have credit card debt, which typically carries interest rates higher than other types of debt, making it far more expensive. Focus on paying off such high-interest debt first, before moving on to other types of debt such as auto loans, student loans, or a mortgage.

“Credit card debt and any unsecured debt should be paid before anything else,” Mr. Snider says. “Getting rid of those high interest rates should be a priority. And that type of debt has less flexible terms than student debt.”

4. Great opportunity to take advantage of record-low interest rates.

Physicians said that, to save money, they are recommending the following: “Consolidating student debt into our mortgage,” “Accelerating payments of the principle on our mortgage,” “Making sure we have an affordable mortgage.”

With interest rates at an all-time low, even those who’ve recently refinanced might see significant savings by refinancing again. Given the associated fees, it typically makes sense to refinance if you can reduce your mortgage rate by at least a point, and you’re planning to stay in the home for at least 5 years.

“Depending on how much lower your rate is, refinancing can make a big difference in your monthly payments,” Ms. Guerich said. “For physicians who might need an emergency reserve but don’t have cash on hand, a HELOC [Home Equity Line of Credit] is a great way to accomplish that.”

5. Be wary of credit cards dangers; use cards wisely.

Physician respondents recommended the following: “Use 0% interest offers on credit cards,” “Only have one card and pay it off every month,” “Never carry over balance.”

Nearly 80% of physicians have three or more credit cards, with 18% reporting that they have seven or more. When used wisely, credit cards can be an important tool for managing finances. Many credit cards come with tools that can help with budgeting, and credit cards rewards and perks can offer real value to users. That said, rewards typically are not valuable enough to offset the cost of interest on balances (or the associated damage to your credit score) that aren’t paid off each month.

“If you’re paying a high rate on credit card balances that carry over every month, regardless of your income, that could be a symptom that you may be spending more than you should,” says Dan Keady, a CFP and chief financial planning strategist at financial services firm TIAA.

6. Give less to Uncle Sam: Keep it for yourself.

Physicians said that they do the following: “Maximize tax-free/deferred savings (401k, HSA, etc.),” “Give to charity to reduce tax,” “Use pre-tax dollars for childcare and healthcare.”

Not only does saving in workplace retirement accounts help you build your nest egg, but it also reduces the amount that you have to pay in taxes in a given year. Physicians should also take advantage of other ways to reduce their income for tax purposes, such as saving money in a health savings account or flexible savings account.

The 401(k) or 403(b) contribution limit for this year is $19,500 ($26,000) for those age 50 years and older. Self-employed physicians can save even more money via a Simplified Employee Pension (SEP) IRA, says Ms. Guerich said. They can save up to 25% of compensation, up to $57,000 in 2020.

7. Automate everything and spare yourself the headache.

Physicians said the following: “Designate money from your paycheck directly to tax deferred and taxable accounts automatically,” “Use automatic payment for credit card balance monthly,” “Automate your savings.”

You probably already automate your 401(k) contributions, but you can also automate bill payments, emergency savings contributions and other financial tasks. For busy physicians, this can make it easier to stick to your financial plan and achieve your goals.

“The older you get, the busier you get, said Mr. Snider says. “Automation can definitely help with that. But make sure you are checking in quarterly to make sure that everything is still in line with your plan. The problem with automation is when you forget about it completely and just let everything sit there.”

8. Save separately for big purchases.

Sometimes it’s the big major expenses that can start to derail a budget. Physicians told us the following tactics for large purchases: “We buy affordable cars and take budget vacations,” “I buy used cars,” “We save in advance for new cars and only buy cars with cash.”

The decision of which car to purchase or where to go on a family vacation is a personal one, and some physicians take great enjoyment and pride in driving a luxury vehicle or traveling to exotic locales. The key, experts say, is to factor the cost of that car into the rest of your budget, and make sure that it’s not preventing you from achieving other financial goals.

“I don’t like to judge or tell clients how they should spend their money,” said Andrew Musbach, a certified financial planner and cofounder of MD Wealth Management in Chelsea, Mich. “Some people like cars, we have clients that have two planes, others want a second house or like to travel. Each person has their own interest where they may spend more relative to other people, but as long as they are meeting their savings targets, I encourage them to spend their money and enjoy what they enjoy most, guilt free.”

Mr. Snider suggests setting up a savings account separate from emergency or retirement accounts to set aside money if you have a goal for a large future purchase, such as a boat or a second home.

“That way, the funds don’t get commingled, and it’s explicitly clear whether or not the doctor is on target,” he says. “It also prevents them from treating their emergency savings account as an ATM machine.”

9. Start saving for college when the kids are little.

Respondents said the following: “We are buying less to save for the kids’ college education,” “We set up direct deposit into college and retirement savings plans,” “We have a 529 account for college savings.”

Helping pay for their children’s college education is an important financial goal for many physicians. The earlier that you start saving, the less you’ll have to save overall, thanks to compound interest. State 529 accounts are often a good place to start, especially if your state offers a tax incentive for doing so.

Mr. Snider recommends that physicians start small, with an initial investment of $1,000 per month and $100 per month contributions. Assuming a 7% rate of return and 17 years’ worth of savings, this would generate just over $42,000. (Note, current typical rates of return are less than 7%).

“Ideally, as other goals are accomplished and personal debt gets paid off, the doctor is ramping up their savings to have at least 50% of college expenses covered from their 529 college savings,” he says.

10. Watch out for the temptation of impulse purchases.

Physicians said the following: “Avoid impulse purchases,” “Avoid impulse shopping, make a list for the store and stick to it,” “Wait to buy things on sale.”

Nothing wrecks a budget like an impulse buy. More than half (54%) of U.S. shoppers have admitted to spending $100 or more on an impulse purchase. And 20% of shoppers have spent at least $1,000 on an impulse buy. Avoid buyers’ remorse by waiting a few days to make large purchase decisions or by limiting your unplanned spending to a certain dollar amount within your budget.

Online shopping may be a particular temptation. Dr. Tarugu, the Florida gastroenterologist, has focused on reducing those impulse buys as well, deleting all online shopping apps from his and his family’s phones.

“You won’t notice how much you have ordered online until it arrives at your doorstep,” he said. “It’s really important to keep it at bay.”

Mr. Keady, the TIAA chief planning strategist, recommended this tactic: Calculate the number of patients (or hours) you’d need to see in order to earn the cash required to make the purchase.

“Then, in a mindful way, figure out the amount of value derived from the purchase,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

“Some of our physician clients have seen their income decrease by as much as 50%,” says Joel Greenwald, MD, CEO of Greenwald Wealth Management in St. Louis Park, Minnesota. “Many physicians had previously figured that whatever financial obligations they had wouldn’t be a problem because whatever amount they were making would continue, and if there were a decline it would be gradual.” However, assumption is now creating financial strain for many doctors.

Vikram Tarugu, MD, a gastroenterologist and CEO of Detox of South Florida in Okeechobee, Florida, says he has watched his budget for years, but has become even more careful with his spending in the past few months.

“It has helped me a lot to adjust to the new normal when it comes to the financial side of things,” Dr. Tarugu said. “Patients aren’t coming in as much as they used to, so my income has really been affected.”

Primary care physicians have seen a 55% decrease in revenue and a 20%-30% decrease in patient volume as a result of COVID-19. The impact has been even more severe for specialists. Even for physicians whose practices remain busy and whose family members haven’t lost their jobs or income, broader concerns about the economy may be reason enough for physicians to adopt cost-cutting measures.

In Medscape’s Physician Compensation Report 2020, we asked physicians to share their best cost-cutting tips. Many illustrate the lengths to which physicians are going to conserve money.

Here’s a look at some of the advice they shared, along with guidance from experts on how to make it work for you:

1. Create a written budget, even if you think it’s pointless.

Physicians said their most important piece of advice includes the following: “Use a formal budget to track progress,” “write out a budget,” “plan intermittent/large expenses in advance,” “Make sure all expenses are paid before you spend on leisure.”

Nearly 7 in 10 physicians say they have a budget for personal expenses, yet only one-quarter of those who do have a formal, written budget. Writing out a spending plan is key to being intentional about your spending, making sure that you’re living within your means, and identifying areas in which you may be able to cut back.

“Financial planning is all about cash flow, and everybody should know the amount of money coming in, how much is going out, and the difference between the two,” says Amy Guerich, a partner with Stepp & Rothwell, a Kansas City–based financial planning firm. “That’s important in good times, but it’s even more important now when we see physicians taking pay cuts.”

Many physicians have found that budget apps or software programs are easier to work with than anticipated; some even walk you through the process of creating a budget. To get the most out of the apps, you’ll need to check them regularly and make changes based on their data.

“Sometimes there’s this false belief that just by signing up, you are automatically going to be better at budgeting,” says Scott Snider, CFP, a certified financial planner and partner with Mellen Money Management in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida. “Basically, these apps are a great way to identify problem areas of spending. We have a tendency as humans to underestimate how much we spend on things like Starbucks, dining out, and Amazon shopping.”

One of the doctors’ tips that requires the most willpower is to “pay all expenses before spending on leisure.” That’s because we live in an instant gratification world, and want everything right away, Ms. Guerich said.

“I also think there’s an element of ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ and pressure associated with this profession,” she said. “The stereotype is that physicians are high-income earners so ‘We should be able to do that’ or ‘Mom and dad are doctors, so they can afford it.’ “

Creating and then revisiting your budget progress on a monthly or quarterly basis can give you a feeling of accomplishment and keep you motivated to stay with it.

Keep in mind that budgeting is a continual process rather than a singular event, and you’ll likely adjust it over time as your income and goals change.

2. Save more as you earn more.

Respondents to our Physician Compensation Report gave the following recommendations: “Pay yourself first,” “I put half of my bonus into an investment account no matter how much it is,” “I allocate extra money and put it into a savings account.”

Dr. Greenwald said, “I have a rule that every client needs to be saving 20% of their gross income toward retirement, including whatever the employer is putting in.”

Putting a portion of every paycheck into savings is key to making progress toward financial goals. Start by building an emergency fund with at least 3-6 months’ worth of expenses in it and making sure you’re saving at least enough for retirement to get any potential employer match.

Mr. Snider suggests increasing the percentage you save every time you get a raise.

“The thought behind that strategy is that when a doctor receives a pay raise – even if it’s just a cost-of-living raise of 3% – an extra 1% saved doesn’t reduce their take-home pay year-over-year,” he says. “In fact, they still take home more money, and they save more money. Win-win.”

3. Focus on paying down your debt.

Physicians told us how they were working to pay down debt with the following recommendations: “Accelerate debt reduction,” “I make additional principal payment to our home mortgage,” “We are aggressively attacking our remaining student loans.”

Reducing or eliminating debt is key to increasing cash flow, which can make it easier to meet all of your other financial goals. One-quarter of physicians have credit card debt, which typically carries interest rates higher than other types of debt, making it far more expensive. Focus on paying off such high-interest debt first, before moving on to other types of debt such as auto loans, student loans, or a mortgage.

“Credit card debt and any unsecured debt should be paid before anything else,” Mr. Snider says. “Getting rid of those high interest rates should be a priority. And that type of debt has less flexible terms than student debt.”

4. Great opportunity to take advantage of record-low interest rates.

Physicians said that, to save money, they are recommending the following: “Consolidating student debt into our mortgage,” “Accelerating payments of the principle on our mortgage,” “Making sure we have an affordable mortgage.”

With interest rates at an all-time low, even those who’ve recently refinanced might see significant savings by refinancing again. Given the associated fees, it typically makes sense to refinance if you can reduce your mortgage rate by at least a point, and you’re planning to stay in the home for at least 5 years.

“Depending on how much lower your rate is, refinancing can make a big difference in your monthly payments,” Ms. Guerich said. “For physicians who might need an emergency reserve but don’t have cash on hand, a HELOC [Home Equity Line of Credit] is a great way to accomplish that.”

5. Be wary of credit cards dangers; use cards wisely.

Physician respondents recommended the following: “Use 0% interest offers on credit cards,” “Only have one card and pay it off every month,” “Never carry over balance.”

Nearly 80% of physicians have three or more credit cards, with 18% reporting that they have seven or more. When used wisely, credit cards can be an important tool for managing finances. Many credit cards come with tools that can help with budgeting, and credit cards rewards and perks can offer real value to users. That said, rewards typically are not valuable enough to offset the cost of interest on balances (or the associated damage to your credit score) that aren’t paid off each month.

“If you’re paying a high rate on credit card balances that carry over every month, regardless of your income, that could be a symptom that you may be spending more than you should,” says Dan Keady, a CFP and chief financial planning strategist at financial services firm TIAA.

6. Give less to Uncle Sam: Keep it for yourself.

Physicians said that they do the following: “Maximize tax-free/deferred savings (401k, HSA, etc.),” “Give to charity to reduce tax,” “Use pre-tax dollars for childcare and healthcare.”

Not only does saving in workplace retirement accounts help you build your nest egg, but it also reduces the amount that you have to pay in taxes in a given year. Physicians should also take advantage of other ways to reduce their income for tax purposes, such as saving money in a health savings account or flexible savings account.

The 401(k) or 403(b) contribution limit for this year is $19,500 ($26,000) for those age 50 years and older. Self-employed physicians can save even more money via a Simplified Employee Pension (SEP) IRA, says Ms. Guerich said. They can save up to 25% of compensation, up to $57,000 in 2020.

7. Automate everything and spare yourself the headache.

Physicians said the following: “Designate money from your paycheck directly to tax deferred and taxable accounts automatically,” “Use automatic payment for credit card balance monthly,” “Automate your savings.”

You probably already automate your 401(k) contributions, but you can also automate bill payments, emergency savings contributions and other financial tasks. For busy physicians, this can make it easier to stick to your financial plan and achieve your goals.

“The older you get, the busier you get, said Mr. Snider says. “Automation can definitely help with that. But make sure you are checking in quarterly to make sure that everything is still in line with your plan. The problem with automation is when you forget about it completely and just let everything sit there.”

8. Save separately for big purchases.

Sometimes it’s the big major expenses that can start to derail a budget. Physicians told us the following tactics for large purchases: “We buy affordable cars and take budget vacations,” “I buy used cars,” “We save in advance for new cars and only buy cars with cash.”

The decision of which car to purchase or where to go on a family vacation is a personal one, and some physicians take great enjoyment and pride in driving a luxury vehicle or traveling to exotic locales. The key, experts say, is to factor the cost of that car into the rest of your budget, and make sure that it’s not preventing you from achieving other financial goals.

“I don’t like to judge or tell clients how they should spend their money,” said Andrew Musbach, a certified financial planner and cofounder of MD Wealth Management in Chelsea, Mich. “Some people like cars, we have clients that have two planes, others want a second house or like to travel. Each person has their own interest where they may spend more relative to other people, but as long as they are meeting their savings targets, I encourage them to spend their money and enjoy what they enjoy most, guilt free.”

Mr. Snider suggests setting up a savings account separate from emergency or retirement accounts to set aside money if you have a goal for a large future purchase, such as a boat or a second home.

“That way, the funds don’t get commingled, and it’s explicitly clear whether or not the doctor is on target,” he says. “It also prevents them from treating their emergency savings account as an ATM machine.”

9. Start saving for college when the kids are little.

Respondents said the following: “We are buying less to save for the kids’ college education,” “We set up direct deposit into college and retirement savings plans,” “We have a 529 account for college savings.”

Helping pay for their children’s college education is an important financial goal for many physicians. The earlier that you start saving, the less you’ll have to save overall, thanks to compound interest. State 529 accounts are often a good place to start, especially if your state offers a tax incentive for doing so.

Mr. Snider recommends that physicians start small, with an initial investment of $1,000 per month and $100 per month contributions. Assuming a 7% rate of return and 17 years’ worth of savings, this would generate just over $42,000. (Note, current typical rates of return are less than 7%).

“Ideally, as other goals are accomplished and personal debt gets paid off, the doctor is ramping up their savings to have at least 50% of college expenses covered from their 529 college savings,” he says.

10. Watch out for the temptation of impulse purchases.

Physicians said the following: “Avoid impulse purchases,” “Avoid impulse shopping, make a list for the store and stick to it,” “Wait to buy things on sale.”

Nothing wrecks a budget like an impulse buy. More than half (54%) of U.S. shoppers have admitted to spending $100 or more on an impulse purchase. And 20% of shoppers have spent at least $1,000 on an impulse buy. Avoid buyers’ remorse by waiting a few days to make large purchase decisions or by limiting your unplanned spending to a certain dollar amount within your budget.

Online shopping may be a particular temptation. Dr. Tarugu, the Florida gastroenterologist, has focused on reducing those impulse buys as well, deleting all online shopping apps from his and his family’s phones.

“You won’t notice how much you have ordered online until it arrives at your doorstep,” he said. “It’s really important to keep it at bay.”

Mr. Keady, the TIAA chief planning strategist, recommended this tactic: Calculate the number of patients (or hours) you’d need to see in order to earn the cash required to make the purchase.

“Then, in a mindful way, figure out the amount of value derived from the purchase,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

“Some of our physician clients have seen their income decrease by as much as 50%,” says Joel Greenwald, MD, CEO of Greenwald Wealth Management in St. Louis Park, Minnesota. “Many physicians had previously figured that whatever financial obligations they had wouldn’t be a problem because whatever amount they were making would continue, and if there were a decline it would be gradual.” However, assumption is now creating financial strain for many doctors.

Vikram Tarugu, MD, a gastroenterologist and CEO of Detox of South Florida in Okeechobee, Florida, says he has watched his budget for years, but has become even more careful with his spending in the past few months.

“It has helped me a lot to adjust to the new normal when it comes to the financial side of things,” Dr. Tarugu said. “Patients aren’t coming in as much as they used to, so my income has really been affected.”

Primary care physicians have seen a 55% decrease in revenue and a 20%-30% decrease in patient volume as a result of COVID-19. The impact has been even more severe for specialists. Even for physicians whose practices remain busy and whose family members haven’t lost their jobs or income, broader concerns about the economy may be reason enough for physicians to adopt cost-cutting measures.

In Medscape’s Physician Compensation Report 2020, we asked physicians to share their best cost-cutting tips. Many illustrate the lengths to which physicians are going to conserve money.

Here’s a look at some of the advice they shared, along with guidance from experts on how to make it work for you:

1. Create a written budget, even if you think it’s pointless.

Physicians said their most important piece of advice includes the following: “Use a formal budget to track progress,” “write out a budget,” “plan intermittent/large expenses in advance,” “Make sure all expenses are paid before you spend on leisure.”

Nearly 7 in 10 physicians say they have a budget for personal expenses, yet only one-quarter of those who do have a formal, written budget. Writing out a spending plan is key to being intentional about your spending, making sure that you’re living within your means, and identifying areas in which you may be able to cut back.

“Financial planning is all about cash flow, and everybody should know the amount of money coming in, how much is going out, and the difference between the two,” says Amy Guerich, a partner with Stepp & Rothwell, a Kansas City–based financial planning firm. “That’s important in good times, but it’s even more important now when we see physicians taking pay cuts.”

Many physicians have found that budget apps or software programs are easier to work with than anticipated; some even walk you through the process of creating a budget. To get the most out of the apps, you’ll need to check them regularly and make changes based on their data.

“Sometimes there’s this false belief that just by signing up, you are automatically going to be better at budgeting,” says Scott Snider, CFP, a certified financial planner and partner with Mellen Money Management in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida. “Basically, these apps are a great way to identify problem areas of spending. We have a tendency as humans to underestimate how much we spend on things like Starbucks, dining out, and Amazon shopping.”

One of the doctors’ tips that requires the most willpower is to “pay all expenses before spending on leisure.” That’s because we live in an instant gratification world, and want everything right away, Ms. Guerich said.

“I also think there’s an element of ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ and pressure associated with this profession,” she said. “The stereotype is that physicians are high-income earners so ‘We should be able to do that’ or ‘Mom and dad are doctors, so they can afford it.’ “

Creating and then revisiting your budget progress on a monthly or quarterly basis can give you a feeling of accomplishment and keep you motivated to stay with it.

Keep in mind that budgeting is a continual process rather than a singular event, and you’ll likely adjust it over time as your income and goals change.

2. Save more as you earn more.

Respondents to our Physician Compensation Report gave the following recommendations: “Pay yourself first,” “I put half of my bonus into an investment account no matter how much it is,” “I allocate extra money and put it into a savings account.”

Dr. Greenwald said, “I have a rule that every client needs to be saving 20% of their gross income toward retirement, including whatever the employer is putting in.”

Putting a portion of every paycheck into savings is key to making progress toward financial goals. Start by building an emergency fund with at least 3-6 months’ worth of expenses in it and making sure you’re saving at least enough for retirement to get any potential employer match.

Mr. Snider suggests increasing the percentage you save every time you get a raise.

“The thought behind that strategy is that when a doctor receives a pay raise – even if it’s just a cost-of-living raise of 3% – an extra 1% saved doesn’t reduce their take-home pay year-over-year,” he says. “In fact, they still take home more money, and they save more money. Win-win.”

3. Focus on paying down your debt.

Physicians told us how they were working to pay down debt with the following recommendations: “Accelerate debt reduction,” “I make additional principal payment to our home mortgage,” “We are aggressively attacking our remaining student loans.”

Reducing or eliminating debt is key to increasing cash flow, which can make it easier to meet all of your other financial goals. One-quarter of physicians have credit card debt, which typically carries interest rates higher than other types of debt, making it far more expensive. Focus on paying off such high-interest debt first, before moving on to other types of debt such as auto loans, student loans, or a mortgage.

“Credit card debt and any unsecured debt should be paid before anything else,” Mr. Snider says. “Getting rid of those high interest rates should be a priority. And that type of debt has less flexible terms than student debt.”

4. Great opportunity to take advantage of record-low interest rates.

Physicians said that, to save money, they are recommending the following: “Consolidating student debt into our mortgage,” “Accelerating payments of the principle on our mortgage,” “Making sure we have an affordable mortgage.”

With interest rates at an all-time low, even those who’ve recently refinanced might see significant savings by refinancing again. Given the associated fees, it typically makes sense to refinance if you can reduce your mortgage rate by at least a point, and you’re planning to stay in the home for at least 5 years.

“Depending on how much lower your rate is, refinancing can make a big difference in your monthly payments,” Ms. Guerich said. “For physicians who might need an emergency reserve but don’t have cash on hand, a HELOC [Home Equity Line of Credit] is a great way to accomplish that.”

5. Be wary of credit cards dangers; use cards wisely.

Physician respondents recommended the following: “Use 0% interest offers on credit cards,” “Only have one card and pay it off every month,” “Never carry over balance.”

Nearly 80% of physicians have three or more credit cards, with 18% reporting that they have seven or more. When used wisely, credit cards can be an important tool for managing finances. Many credit cards come with tools that can help with budgeting, and credit cards rewards and perks can offer real value to users. That said, rewards typically are not valuable enough to offset the cost of interest on balances (or the associated damage to your credit score) that aren’t paid off each month.

“If you’re paying a high rate on credit card balances that carry over every month, regardless of your income, that could be a symptom that you may be spending more than you should,” says Dan Keady, a CFP and chief financial planning strategist at financial services firm TIAA.

6. Give less to Uncle Sam: Keep it for yourself.

Physicians said that they do the following: “Maximize tax-free/deferred savings (401k, HSA, etc.),” “Give to charity to reduce tax,” “Use pre-tax dollars for childcare and healthcare.”

Not only does saving in workplace retirement accounts help you build your nest egg, but it also reduces the amount that you have to pay in taxes in a given year. Physicians should also take advantage of other ways to reduce their income for tax purposes, such as saving money in a health savings account or flexible savings account.

The 401(k) or 403(b) contribution limit for this year is $19,500 ($26,000) for those age 50 years and older. Self-employed physicians can save even more money via a Simplified Employee Pension (SEP) IRA, says Ms. Guerich said. They can save up to 25% of compensation, up to $57,000 in 2020.

7. Automate everything and spare yourself the headache.

Physicians said the following: “Designate money from your paycheck directly to tax deferred and taxable accounts automatically,” “Use automatic payment for credit card balance monthly,” “Automate your savings.”

You probably already automate your 401(k) contributions, but you can also automate bill payments, emergency savings contributions and other financial tasks. For busy physicians, this can make it easier to stick to your financial plan and achieve your goals.

“The older you get, the busier you get, said Mr. Snider says. “Automation can definitely help with that. But make sure you are checking in quarterly to make sure that everything is still in line with your plan. The problem with automation is when you forget about it completely and just let everything sit there.”

8. Save separately for big purchases.

Sometimes it’s the big major expenses that can start to derail a budget. Physicians told us the following tactics for large purchases: “We buy affordable cars and take budget vacations,” “I buy used cars,” “We save in advance for new cars and only buy cars with cash.”

The decision of which car to purchase or where to go on a family vacation is a personal one, and some physicians take great enjoyment and pride in driving a luxury vehicle or traveling to exotic locales. The key, experts say, is to factor the cost of that car into the rest of your budget, and make sure that it’s not preventing you from achieving other financial goals.

“I don’t like to judge or tell clients how they should spend their money,” said Andrew Musbach, a certified financial planner and cofounder of MD Wealth Management in Chelsea, Mich. “Some people like cars, we have clients that have two planes, others want a second house or like to travel. Each person has their own interest where they may spend more relative to other people, but as long as they are meeting their savings targets, I encourage them to spend their money and enjoy what they enjoy most, guilt free.”

Mr. Snider suggests setting up a savings account separate from emergency or retirement accounts to set aside money if you have a goal for a large future purchase, such as a boat or a second home.

“That way, the funds don’t get commingled, and it’s explicitly clear whether or not the doctor is on target,” he says. “It also prevents them from treating their emergency savings account as an ATM machine.”

9. Start saving for college when the kids are little.

Respondents said the following: “We are buying less to save for the kids’ college education,” “We set up direct deposit into college and retirement savings plans,” “We have a 529 account for college savings.”

Helping pay for their children’s college education is an important financial goal for many physicians. The earlier that you start saving, the less you’ll have to save overall, thanks to compound interest. State 529 accounts are often a good place to start, especially if your state offers a tax incentive for doing so.

Mr. Snider recommends that physicians start small, with an initial investment of $1,000 per month and $100 per month contributions. Assuming a 7% rate of return and 17 years’ worth of savings, this would generate just over $42,000. (Note, current typical rates of return are less than 7%).

“Ideally, as other goals are accomplished and personal debt gets paid off, the doctor is ramping up their savings to have at least 50% of college expenses covered from their 529 college savings,” he says.

10. Watch out for the temptation of impulse purchases.

Physicians said the following: “Avoid impulse purchases,” “Avoid impulse shopping, make a list for the store and stick to it,” “Wait to buy things on sale.”

Nothing wrecks a budget like an impulse buy. More than half (54%) of U.S. shoppers have admitted to spending $100 or more on an impulse purchase. And 20% of shoppers have spent at least $1,000 on an impulse buy. Avoid buyers’ remorse by waiting a few days to make large purchase decisions or by limiting your unplanned spending to a certain dollar amount within your budget.

Online shopping may be a particular temptation. Dr. Tarugu, the Florida gastroenterologist, has focused on reducing those impulse buys as well, deleting all online shopping apps from his and his family’s phones.

“You won’t notice how much you have ordered online until it arrives at your doorstep,” he said. “It’s really important to keep it at bay.”

Mr. Keady, the TIAA chief planning strategist, recommended this tactic: Calculate the number of patients (or hours) you’d need to see in order to earn the cash required to make the purchase.

“Then, in a mindful way, figure out the amount of value derived from the purchase,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Identifying ovarian malignancy is not so easy

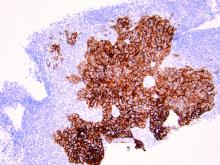

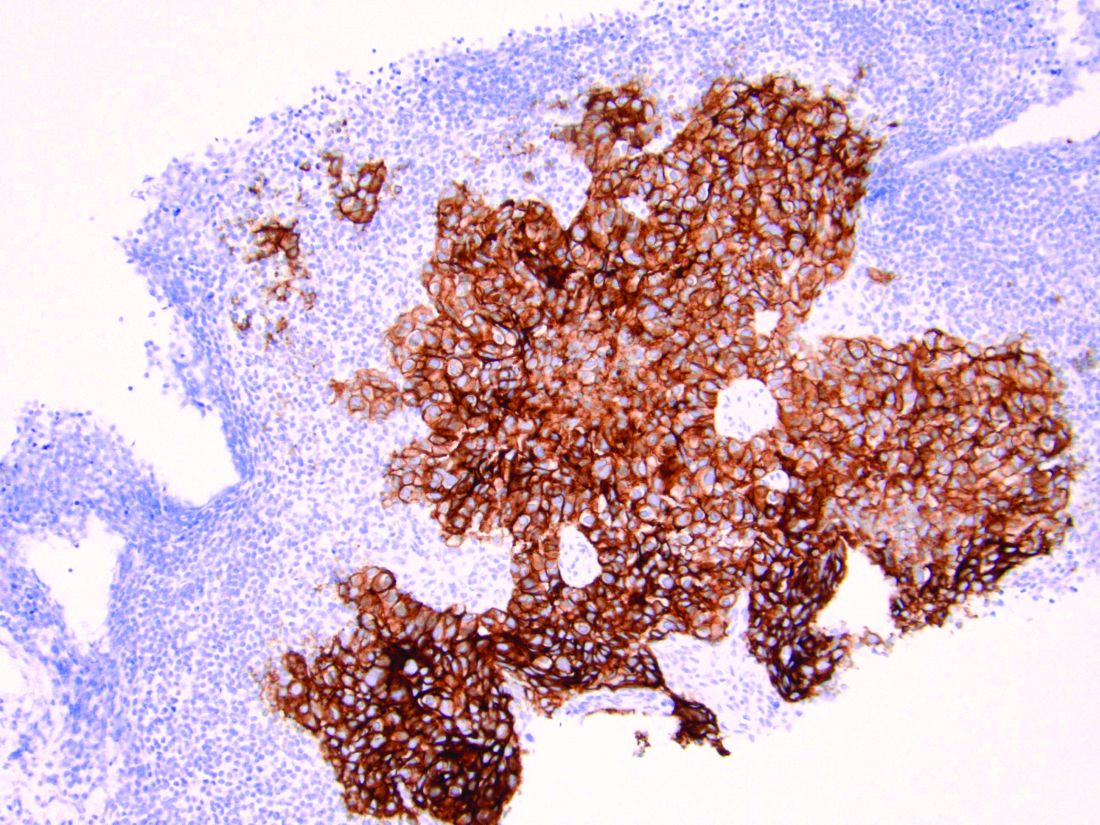

When an ovarian mass is anticipated or known, following evaluation of a patient’s history and physician examination, imaging via transvaginal and often abdominal ultrasound is the very next step. This evaluation likely will include both gray-scale and color Doppler examination. The initial concern always must be to identify ovarian malignancy.

Despite morphological scoring systems as well as the use of Doppler ultrasonography, there remains a lack of agreement and acceptance. In a 2008 multicenter study, Timmerman and colleagues evaluated 1,066 patients with 1,233 persistent adnexal tumors via transvaginal grayscale and Doppler ultrasound; 73% were benign tumors, and 27% were malignant tumors. Information on 42 gray-scale ultrasound variables and 6 Doppler variables was collected and evaluated to determine which variables had the highest positive predictive value for a malignant tumor and for a benign mass (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365).

Five simple rules were selected that best predict malignancy (M-rules), as follows:

- Irregular solid tumor.

- Ascites.

- At least four papillary projections.

- Irregular multilocular-solid tumor with a greatest diameter greater than or equal to 10 cm.

- Very high color content on Doppler exam.

The following five simple rules suggested that a mass is benign (B-rules):

- Unilocular cyst.

- Largest solid component less than 7 mm.

- Acoustic shadows.

- Smooth multilocular tumor less than 10 cm.

- No detectable blood flow with Doppler exam.

Unfortunately, despite a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 90%, and a positive and negative predictive value of 80% and 97%, these 10 simple rules were applicable to only 76% of tumors.

To assist those of us who are not gynecologic oncologists and who are often faced with having to determine whether surgery is recommended, I have elicited the expertise of Jubilee Brown, MD, professor and associate director of gynecologic oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, in Charlotte, N.C., and the current president of the AAGL, to lead us in a review of evaluating an ovarian mass.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, Ill., and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at [email protected].

When an ovarian mass is anticipated or known, following evaluation of a patient’s history and physician examination, imaging via transvaginal and often abdominal ultrasound is the very next step. This evaluation likely will include both gray-scale and color Doppler examination. The initial concern always must be to identify ovarian malignancy.

Despite morphological scoring systems as well as the use of Doppler ultrasonography, there remains a lack of agreement and acceptance. In a 2008 multicenter study, Timmerman and colleagues evaluated 1,066 patients with 1,233 persistent adnexal tumors via transvaginal grayscale and Doppler ultrasound; 73% were benign tumors, and 27% were malignant tumors. Information on 42 gray-scale ultrasound variables and 6 Doppler variables was collected and evaluated to determine which variables had the highest positive predictive value for a malignant tumor and for a benign mass (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365).

Five simple rules were selected that best predict malignancy (M-rules), as follows:

- Irregular solid tumor.

- Ascites.

- At least four papillary projections.

- Irregular multilocular-solid tumor with a greatest diameter greater than or equal to 10 cm.

- Very high color content on Doppler exam.

The following five simple rules suggested that a mass is benign (B-rules):

- Unilocular cyst.

- Largest solid component less than 7 mm.

- Acoustic shadows.

- Smooth multilocular tumor less than 10 cm.

- No detectable blood flow with Doppler exam.

Unfortunately, despite a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 90%, and a positive and negative predictive value of 80% and 97%, these 10 simple rules were applicable to only 76% of tumors.

To assist those of us who are not gynecologic oncologists and who are often faced with having to determine whether surgery is recommended, I have elicited the expertise of Jubilee Brown, MD, professor and associate director of gynecologic oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, in Charlotte, N.C., and the current president of the AAGL, to lead us in a review of evaluating an ovarian mass.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, Ill., and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at [email protected].

When an ovarian mass is anticipated or known, following evaluation of a patient’s history and physician examination, imaging via transvaginal and often abdominal ultrasound is the very next step. This evaluation likely will include both gray-scale and color Doppler examination. The initial concern always must be to identify ovarian malignancy.

Despite morphological scoring systems as well as the use of Doppler ultrasonography, there remains a lack of agreement and acceptance. In a 2008 multicenter study, Timmerman and colleagues evaluated 1,066 patients with 1,233 persistent adnexal tumors via transvaginal grayscale and Doppler ultrasound; 73% were benign tumors, and 27% were malignant tumors. Information on 42 gray-scale ultrasound variables and 6 Doppler variables was collected and evaluated to determine which variables had the highest positive predictive value for a malignant tumor and for a benign mass (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365).

Five simple rules were selected that best predict malignancy (M-rules), as follows:

- Irregular solid tumor.

- Ascites.

- At least four papillary projections.

- Irregular multilocular-solid tumor with a greatest diameter greater than or equal to 10 cm.

- Very high color content on Doppler exam.

The following five simple rules suggested that a mass is benign (B-rules):

- Unilocular cyst.

- Largest solid component less than 7 mm.

- Acoustic shadows.

- Smooth multilocular tumor less than 10 cm.

- No detectable blood flow with Doppler exam.

Unfortunately, despite a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 90%, and a positive and negative predictive value of 80% and 97%, these 10 simple rules were applicable to only 76% of tumors.

To assist those of us who are not gynecologic oncologists and who are often faced with having to determine whether surgery is recommended, I have elicited the expertise of Jubilee Brown, MD, professor and associate director of gynecologic oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, in Charlotte, N.C., and the current president of the AAGL, to lead us in a review of evaluating an ovarian mass.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, Ill., and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at [email protected].

How to evaluate a suspicious ovarian mass

Ovarian masses are common in women of all ages. It is important not to miss even one ovarian cancer, but we must also identify masses that will resolve on their own over time to avoid overtreatment. These concurrent goals of excluding malignancy while not overtreating patients are the basis for management of the pelvic mass. Additionally, fertility preservation is important when surgery is performed in a reproductive-aged woman.

An ovarian mass may be anything from a simple functional or physiologic cyst to an endometrioma to an epithelial carcinoma, a germ-cell tumor, or a stromal tumor (the latter three of which may metastasize). Across the general population, women have a 5%-10% lifetime risk of needing surgery for a suspected ovarian mass and a 1.4% (1 in 70) risk that this mass is cancerous. The majority of ovarian cysts or masses therefore are benign.

A thorough history – including family history – and physical examination with appropriate laboratory testing and directed imaging are important first steps for the ob.gyn. Fortunately, we have guidelines and criteria governing not only when observation or surgery is warranted but also when patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist. By following these guidelines,1 we are able to achieve the best outcomes.

Transvaginal ultrasound

A 2007 groundbreaking study led by Barbara Goff, MD, demonstrated that there are warning signs for ovarian cancer – symptoms that are significantly associated with malignancy. Dr. Goff and her coinvestigators evaluated the charts of hundreds of patients, including about 150 with ovarian cancer, and found that pelvic/abdominal pressure or pain, bloating, increase in abdominal size, and difficulty eating or feeling full were significantly and independently associated with cancer if these symptoms were present for less than a year and occurred at least 12 times per month.2

A pelvic examination is an integral part of evaluating every patient who has such concerns. That said, pelvic exams have limited ability to identify adnexal masses, especially in women who are obese – and that’s where imaging becomes especially important.

Masses generally can be considered simple or complex based on their appearance. A simple cyst is fluid-filled with thin, smooth walls and the absence of solid components or septations; it is significantly more likely to resolve on its own and is less likely to imply malignancy than a complex cyst, especially in a premenopausal woman. A complex cyst is multiseptated and/or solid – possibly with papillary projections – and is more concerning, especially if there is increased, new vascularity. Making this distinction helps us determine the risk of malignancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the preferred method for imaging, and our threshold for obtaining a TVUS should be very low. Women who have symptoms or concerns that can’t be attributed to a particular condition, and women in whom a mass can be palpated (even if asymptomatic) should have a TVUS. The imaging modality is cost effective and well tolerated by patients, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and should generally be considered first-line imaging.3,4

Size is not predictive of malignancy, but it is important for determining whether surgery is warranted. In our experience, a mass of 8-10 cm or larger on TVUS is at risk of torsion and is unlikely to resolve on its own, even in a premenopausal woman. While large masses generally require surgery, patients of any age who have simple cysts smaller than 8-10 cm generally can be followed with serial exams and ultrasound; spontaneous regression is common.

Doppler ultrasonography is useful for evaluating blood flow in and around an ovarian mass and can be helpful for confirming suspected characteristics of a mass.

Recent studies from the radiology community have looked at the utility of the resistive index – a measure of the impedance and velocity of blood flow – as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. However, we caution against using Doppler to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant, or to determine the necessity of surgery. An abnormal ovary may have what is considered to be a normal resistive index, and the resistive index of a normal ovary may fall within the abnormal range. Doppler flow can be helpful, but it must be combined with other predictive features, like solid components with flow or papillary projections within a cyst, to define a decision about surgery.4,5

Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in differentiating a fibroid from an ovarian mass, and a CT scan can be helpful in looking for disseminated disease when ovarian cancer is suspected based on ultrasound imaging, physical and history, and serum markers. A CT is useful, for instance, in a patient whose ovary is distended with ascites or who has upper abdominal complaints and a complex cyst. CT, PET, and MRI are not recommended in the initial evaluation of an ovarian mass.

The utility of serum biomarkers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) testing may be helpful – in combination with other findings – for decision-making regarding the likelihood of malignancy and the need to refer patients. CA-125 is like Doppler in that a normal CA-125 cannot eliminate the possibility of cancer, and an abnormal CA-125 does not in and of itself imply malignancy. It’s far from a perfect cancer screening test.

CA-125 is a protein associated with epithelial ovarian malignancies, the type of ovarian cancer most commonly seen in postmenopausal women with genetic predispositions. Its specificity and positive predictive value are much higher in postmenopausal women than in average-risk premenopausal women (those without a family history or a known mutation that predisposes them to ovarian cancer). Levels of the marker are elevated in association with many nonmalignant conditions in premenopausal women – endometriosis, fibroids, and various inflammatory conditions, for instance – so the marker’s utility in this population is limited.

For women who have a family history of ovarian cancer or a known breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) or BRCA2 mutation, there are some data that suggest that monitoring with CA-125 measurements and TVUS may be a good approach to following patients prior to the age at which risk-reducing surgery can best be performed.

In an adolescent girl or a woman of reproductive age, we think less about epithelial cancer and more about germ-cell and stromal tumors. When a solid mass is palpated or visualized on imaging, we therefore will utilize a different set of markers; alpha-fetoprotein, L-lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-HCG, for instance, have much higher specificity than CA-125 does for germ-cell tumors in this age group and may be helpful in the evaluation. Similarly, in cases of a very large mass resembling a mucinous tumor, a carcinoembryonic antigen may be helpful.

A number of proprietary profiling technologies have been developed to determine the risk of a diagnosed mass being malignant. For instance, the OVA1 assay looks at five serum markers and scores the results, and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) combines the results of three serum markers with menopausal status into a numerical score. Both have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in women in whom surgery has been deemed necessary. These panels can be fairly predictive of risk and may be helpful – especially in rural areas – in determining which women should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for surgery.

It is important to appreciate that an ovarian cyst or mass should never be biopsied or aspirated lest a malignant tumor confined to one ovary be potentially spread to the peritoneum.

Referral to a gynecologic oncologist

Postmenopausal women with a CA-125 greater than 35 U/mL should be referred, as should postmenopausal women with ascites, those with a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, and those with suspected abdominal or distant metastases (per a CT scan, for instance).

In premenopausal women, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, and evidence of metastases also are reasons for referral to a gynecologic oncologist. CA-125, again, is much more likely to be elevated for reasons other than malignancy and therefore is not as strong a driver for referral as in postmenopausal women. Patients with markedly elevated levels, however, should probably be referred – particularly when other clinical factors also suggest the need for consultation. While there is no evidence-based threshold for CA-125 in premenopausal women, a CA-125 greater than 200 U/mL is a good cutoff for referral.

For any patient, family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer – especially in a first-degree relative – raises the risk of malignancy and should figure prominently into decision-making regarding referral. Criteria for referral are among the points discussed in the ACOG 2016 Practice Bulletin on Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.1

A note on BRCA mutations

As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says in its practice bulletin, the most important personal risk factor for ovarian cancer is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Women with such a family history can undergo genetic testing for BRCA mutations and have the opportunity to prevent ovarian cancers when mutations are detected. This simple blood test can save lives.

A modeling study we recently completed – not yet published – shows that it actually would be cost effective to do population screening with BRCA testing performed on every woman at age 30 years.

According to the National Cancer Institute website (last review: 2018), it is estimated that about 44% of women who inherit a BRCA1 mutation, and about 17% of those who inherit a BRAC2 mutation, will develop ovarian cancer by the age of 80 years. By identifying those mutations, women may undergo risk-reducing surgery at designated ages after childbearing is complete and bring their risk down to under 5%.

An international take on managing adnexal masses

- Pelvic ultrasound should include the transvaginal approach. Use Doppler imaging as indicated.

- Although simple ovarian cysts are not precursor lesions to a malignant ovarian cancer, perform a high-quality examination to make sure there are no solid/papillary structures before classifying a cyst as a simple cyst. The risk of progression to malignancy is extremely low, but some follow-up is prudent.

- The most accurate method of characterizing an ovarian mass currently is real-time pattern recognition sonography in the hands of an experienced imager.

- Pattern recognition sonography or a risk model such as the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Simple Rules can be used to initially characterize an ovarian mass.

- When an ovarian lesion is classified as benign, the patient may be followed conservatively, or if indicated, surgery can be performed by a general gynecologist.

- Serial sonography can be beneficial, but there are limited prospective data to support an exact interval and duration.

- Fewer surgical interventions may result in an increase in sonographic surveillance.

- When an ovarian lesion is considered indeterminate on initial sonography, and after appropriate clinical evaluation, a “second-step” evaluation may include referral to an expert sonologist, serial sonography, application of established risk-prediction models, correlation with serum biomarkers, correlation with MRI, or referral to a gynecologic oncologist for further evaluation.

From the First International Consensus Report on Adnexal Masses: Management Recommendations

Source: Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 May;36(5):849-63.

Dr. Brown reported that she had received an earlier grant from Aspira Labs, the company that developed the OVA1 assay. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768.

2. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371.

3. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000083.

4. Ultrasound Q. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3182814d9b.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365.

Ovarian masses are common in women of all ages. It is important not to miss even one ovarian cancer, but we must also identify masses that will resolve on their own over time to avoid overtreatment. These concurrent goals of excluding malignancy while not overtreating patients are the basis for management of the pelvic mass. Additionally, fertility preservation is important when surgery is performed in a reproductive-aged woman.

An ovarian mass may be anything from a simple functional or physiologic cyst to an endometrioma to an epithelial carcinoma, a germ-cell tumor, or a stromal tumor (the latter three of which may metastasize). Across the general population, women have a 5%-10% lifetime risk of needing surgery for a suspected ovarian mass and a 1.4% (1 in 70) risk that this mass is cancerous. The majority of ovarian cysts or masses therefore are benign.

A thorough history – including family history – and physical examination with appropriate laboratory testing and directed imaging are important first steps for the ob.gyn. Fortunately, we have guidelines and criteria governing not only when observation or surgery is warranted but also when patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist. By following these guidelines,1 we are able to achieve the best outcomes.

Transvaginal ultrasound

A 2007 groundbreaking study led by Barbara Goff, MD, demonstrated that there are warning signs for ovarian cancer – symptoms that are significantly associated with malignancy. Dr. Goff and her coinvestigators evaluated the charts of hundreds of patients, including about 150 with ovarian cancer, and found that pelvic/abdominal pressure or pain, bloating, increase in abdominal size, and difficulty eating or feeling full were significantly and independently associated with cancer if these symptoms were present for less than a year and occurred at least 12 times per month.2

A pelvic examination is an integral part of evaluating every patient who has such concerns. That said, pelvic exams have limited ability to identify adnexal masses, especially in women who are obese – and that’s where imaging becomes especially important.

Masses generally can be considered simple or complex based on their appearance. A simple cyst is fluid-filled with thin, smooth walls and the absence of solid components or septations; it is significantly more likely to resolve on its own and is less likely to imply malignancy than a complex cyst, especially in a premenopausal woman. A complex cyst is multiseptated and/or solid – possibly with papillary projections – and is more concerning, especially if there is increased, new vascularity. Making this distinction helps us determine the risk of malignancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the preferred method for imaging, and our threshold for obtaining a TVUS should be very low. Women who have symptoms or concerns that can’t be attributed to a particular condition, and women in whom a mass can be palpated (even if asymptomatic) should have a TVUS. The imaging modality is cost effective and well tolerated by patients, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and should generally be considered first-line imaging.3,4

Size is not predictive of malignancy, but it is important for determining whether surgery is warranted. In our experience, a mass of 8-10 cm or larger on TVUS is at risk of torsion and is unlikely to resolve on its own, even in a premenopausal woman. While large masses generally require surgery, patients of any age who have simple cysts smaller than 8-10 cm generally can be followed with serial exams and ultrasound; spontaneous regression is common.

Doppler ultrasonography is useful for evaluating blood flow in and around an ovarian mass and can be helpful for confirming suspected characteristics of a mass.

Recent studies from the radiology community have looked at the utility of the resistive index – a measure of the impedance and velocity of blood flow – as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. However, we caution against using Doppler to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant, or to determine the necessity of surgery. An abnormal ovary may have what is considered to be a normal resistive index, and the resistive index of a normal ovary may fall within the abnormal range. Doppler flow can be helpful, but it must be combined with other predictive features, like solid components with flow or papillary projections within a cyst, to define a decision about surgery.4,5

Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in differentiating a fibroid from an ovarian mass, and a CT scan can be helpful in looking for disseminated disease when ovarian cancer is suspected based on ultrasound imaging, physical and history, and serum markers. A CT is useful, for instance, in a patient whose ovary is distended with ascites or who has upper abdominal complaints and a complex cyst. CT, PET, and MRI are not recommended in the initial evaluation of an ovarian mass.

The utility of serum biomarkers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) testing may be helpful – in combination with other findings – for decision-making regarding the likelihood of malignancy and the need to refer patients. CA-125 is like Doppler in that a normal CA-125 cannot eliminate the possibility of cancer, and an abnormal CA-125 does not in and of itself imply malignancy. It’s far from a perfect cancer screening test.

CA-125 is a protein associated with epithelial ovarian malignancies, the type of ovarian cancer most commonly seen in postmenopausal women with genetic predispositions. Its specificity and positive predictive value are much higher in postmenopausal women than in average-risk premenopausal women (those without a family history or a known mutation that predisposes them to ovarian cancer). Levels of the marker are elevated in association with many nonmalignant conditions in premenopausal women – endometriosis, fibroids, and various inflammatory conditions, for instance – so the marker’s utility in this population is limited.

For women who have a family history of ovarian cancer or a known breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) or BRCA2 mutation, there are some data that suggest that monitoring with CA-125 measurements and TVUS may be a good approach to following patients prior to the age at which risk-reducing surgery can best be performed.

In an adolescent girl or a woman of reproductive age, we think less about epithelial cancer and more about germ-cell and stromal tumors. When a solid mass is palpated or visualized on imaging, we therefore will utilize a different set of markers; alpha-fetoprotein, L-lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-HCG, for instance, have much higher specificity than CA-125 does for germ-cell tumors in this age group and may be helpful in the evaluation. Similarly, in cases of a very large mass resembling a mucinous tumor, a carcinoembryonic antigen may be helpful.

A number of proprietary profiling technologies have been developed to determine the risk of a diagnosed mass being malignant. For instance, the OVA1 assay looks at five serum markers and scores the results, and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) combines the results of three serum markers with menopausal status into a numerical score. Both have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in women in whom surgery has been deemed necessary. These panels can be fairly predictive of risk and may be helpful – especially in rural areas – in determining which women should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for surgery.

It is important to appreciate that an ovarian cyst or mass should never be biopsied or aspirated lest a malignant tumor confined to one ovary be potentially spread to the peritoneum.

Referral to a gynecologic oncologist

Postmenopausal women with a CA-125 greater than 35 U/mL should be referred, as should postmenopausal women with ascites, those with a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, and those with suspected abdominal or distant metastases (per a CT scan, for instance).

In premenopausal women, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, and evidence of metastases also are reasons for referral to a gynecologic oncologist. CA-125, again, is much more likely to be elevated for reasons other than malignancy and therefore is not as strong a driver for referral as in postmenopausal women. Patients with markedly elevated levels, however, should probably be referred – particularly when other clinical factors also suggest the need for consultation. While there is no evidence-based threshold for CA-125 in premenopausal women, a CA-125 greater than 200 U/mL is a good cutoff for referral.

For any patient, family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer – especially in a first-degree relative – raises the risk of malignancy and should figure prominently into decision-making regarding referral. Criteria for referral are among the points discussed in the ACOG 2016 Practice Bulletin on Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.1

A note on BRCA mutations

As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says in its practice bulletin, the most important personal risk factor for ovarian cancer is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Women with such a family history can undergo genetic testing for BRCA mutations and have the opportunity to prevent ovarian cancers when mutations are detected. This simple blood test can save lives.

A modeling study we recently completed – not yet published – shows that it actually would be cost effective to do population screening with BRCA testing performed on every woman at age 30 years.

According to the National Cancer Institute website (last review: 2018), it is estimated that about 44% of women who inherit a BRCA1 mutation, and about 17% of those who inherit a BRAC2 mutation, will develop ovarian cancer by the age of 80 years. By identifying those mutations, women may undergo risk-reducing surgery at designated ages after childbearing is complete and bring their risk down to under 5%.

An international take on managing adnexal masses

- Pelvic ultrasound should include the transvaginal approach. Use Doppler imaging as indicated.

- Although simple ovarian cysts are not precursor lesions to a malignant ovarian cancer, perform a high-quality examination to make sure there are no solid/papillary structures before classifying a cyst as a simple cyst. The risk of progression to malignancy is extremely low, but some follow-up is prudent.

- The most accurate method of characterizing an ovarian mass currently is real-time pattern recognition sonography in the hands of an experienced imager.

- Pattern recognition sonography or a risk model such as the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Simple Rules can be used to initially characterize an ovarian mass.

- When an ovarian lesion is classified as benign, the patient may be followed conservatively, or if indicated, surgery can be performed by a general gynecologist.

- Serial sonography can be beneficial, but there are limited prospective data to support an exact interval and duration.

- Fewer surgical interventions may result in an increase in sonographic surveillance.

- When an ovarian lesion is considered indeterminate on initial sonography, and after appropriate clinical evaluation, a “second-step” evaluation may include referral to an expert sonologist, serial sonography, application of established risk-prediction models, correlation with serum biomarkers, correlation with MRI, or referral to a gynecologic oncologist for further evaluation.

From the First International Consensus Report on Adnexal Masses: Management Recommendations

Source: Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 May;36(5):849-63.

Dr. Brown reported that she had received an earlier grant from Aspira Labs, the company that developed the OVA1 assay. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768.

2. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371.

3. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000083.

4. Ultrasound Q. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3182814d9b.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365.

Ovarian masses are common in women of all ages. It is important not to miss even one ovarian cancer, but we must also identify masses that will resolve on their own over time to avoid overtreatment. These concurrent goals of excluding malignancy while not overtreating patients are the basis for management of the pelvic mass. Additionally, fertility preservation is important when surgery is performed in a reproductive-aged woman.

An ovarian mass may be anything from a simple functional or physiologic cyst to an endometrioma to an epithelial carcinoma, a germ-cell tumor, or a stromal tumor (the latter three of which may metastasize). Across the general population, women have a 5%-10% lifetime risk of needing surgery for a suspected ovarian mass and a 1.4% (1 in 70) risk that this mass is cancerous. The majority of ovarian cysts or masses therefore are benign.

A thorough history – including family history – and physical examination with appropriate laboratory testing and directed imaging are important first steps for the ob.gyn. Fortunately, we have guidelines and criteria governing not only when observation or surgery is warranted but also when patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist. By following these guidelines,1 we are able to achieve the best outcomes.

Transvaginal ultrasound

A 2007 groundbreaking study led by Barbara Goff, MD, demonstrated that there are warning signs for ovarian cancer – symptoms that are significantly associated with malignancy. Dr. Goff and her coinvestigators evaluated the charts of hundreds of patients, including about 150 with ovarian cancer, and found that pelvic/abdominal pressure or pain, bloating, increase in abdominal size, and difficulty eating or feeling full were significantly and independently associated with cancer if these symptoms were present for less than a year and occurred at least 12 times per month.2

A pelvic examination is an integral part of evaluating every patient who has such concerns. That said, pelvic exams have limited ability to identify adnexal masses, especially in women who are obese – and that’s where imaging becomes especially important.

Masses generally can be considered simple or complex based on their appearance. A simple cyst is fluid-filled with thin, smooth walls and the absence of solid components or septations; it is significantly more likely to resolve on its own and is less likely to imply malignancy than a complex cyst, especially in a premenopausal woman. A complex cyst is multiseptated and/or solid – possibly with papillary projections – and is more concerning, especially if there is increased, new vascularity. Making this distinction helps us determine the risk of malignancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the preferred method for imaging, and our threshold for obtaining a TVUS should be very low. Women who have symptoms or concerns that can’t be attributed to a particular condition, and women in whom a mass can be palpated (even if asymptomatic) should have a TVUS. The imaging modality is cost effective and well tolerated by patients, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and should generally be considered first-line imaging.3,4

Size is not predictive of malignancy, but it is important for determining whether surgery is warranted. In our experience, a mass of 8-10 cm or larger on TVUS is at risk of torsion and is unlikely to resolve on its own, even in a premenopausal woman. While large masses generally require surgery, patients of any age who have simple cysts smaller than 8-10 cm generally can be followed with serial exams and ultrasound; spontaneous regression is common.

Doppler ultrasonography is useful for evaluating blood flow in and around an ovarian mass and can be helpful for confirming suspected characteristics of a mass.

Recent studies from the radiology community have looked at the utility of the resistive index – a measure of the impedance and velocity of blood flow – as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. However, we caution against using Doppler to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant, or to determine the necessity of surgery. An abnormal ovary may have what is considered to be a normal resistive index, and the resistive index of a normal ovary may fall within the abnormal range. Doppler flow can be helpful, but it must be combined with other predictive features, like solid components with flow or papillary projections within a cyst, to define a decision about surgery.4,5