User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Limiting antibiotic overprescription in pandemics: New guidelines

A statement by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, published online in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, offers health care providers guidelines on how to prevent inappropriate antibiotic use in future pandemics and to avoid some of the negative scenarios that have been seen with COVID-19.

According to the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention,

The culprit might be the widespread antibiotic overprescription during the current pandemic. A 2022 meta-analysis revealed that in high-income countries, 58% of patients with COVID-19 were given antibiotics, whereas in lower- and middle-income countries, 89% of patients were put on such drugs. Some hospitals in Europe and the United States reported similarly elevated numbers, sometimes approaching 100%.

“We’ve lost control,” Natasha Pettit, PharmD, pharmacy director at University of Chicago Medicine, told this news organization. Dr. Pettit was not involved in the SHEA study. “Even if CDC didn’t come out with that data, I can tell you right now more of my time is spent trying to figure out how to manage these multi-drug–resistant infections, and we are running out of options for these patients,”

“Dealing with uncertainty, exhaustion, [and] critical illness in often young, otherwise healthy patients meant doctors wanted to do something for their patients,” said Tamar Barlam, MD, an infectious diseases expert at the Boston Medical Center who led the development of the SHEA white paper, in an interview.

That something often was a prescription for antibiotics, even without a clear indication that they were actually needed. A British study revealed that in times of pandemic uncertainty, clinicians often reached for antibiotics “just in case” and referred to conservative prescribing as “bravery.”

Studies have shown, however, that bacterial co-infections in COVID-19 are rare. A 2020 meta-analysis of 24 studies concluded that only 3.5% of patients had a bacterial co-infection on presentation, and 14.3% had a secondary infection. Similar patterns had previously been observed in other viral outbreaks. Research on MERS-CoV, for example, documented only 1% of patients with a bacterial co-infection on admission. During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, that number was 12% of non–ICU hospitalized patients.

Yet, according to Dr. Pettit, even when such data became available, it didn’t necessarily change prescribing patterns. “Information was coming at us so quickly, I think the providers didn’t have a moment to see the data, to understand what it meant for their prescribing. Having external guidance earlier on would have been hugely helpful,” she told this news organization.

That’s where the newly published SHEA statement comes in: It outlines recommendations on when to prescribe antibiotics during a respiratory viral pandemic, what tests to order, and when to de-escalate or discontinue the treatment. These recommendations include, for instance, advice to not trust inflammatory markers as reliable indicators of bacterial or fungal infection and to not use procalcitonin routinely to aid in the decision to initiate antibiotics.

According to Dr. Barlam, one of the crucial lessons here is that if clinicians see patients with symptoms that are consistent with the current pandemic, they should trust their own impressions and avoid reaching for antimicrobials “just in case.”

Another important lesson is that antibiotic stewardship programs have a huge role to play during pandemics. They should not only monitor prescribing but also compile new information on bacterial co-infections as it gets released and make sure it reaches the clinicians in a clear form.

Evidence suggests that such programs and guidelines do work to limit unnecessary antibiotic use. In one medical center in Chicago, for example, before recommendations on when to initiate and discontinue antimicrobials were released, over 74% of COVID-19 patients received antibiotics. After guidelines were put in place, the use of such drugs fell to 42%.

Dr. Pettit believes, however, that it’s important not to leave each medical center to its own devices. “Hindsight is always twenty-twenty,” she said, “but I think it would be great that, if we start hearing about a pathogen that might lead to another pandemic, we should have a mechanism in place to call together an expert body to get guidance for how antimicrobial stewardship programs should get involved.”

One of the authors of the SHEA statement, Susan Seo, reports an investigator-initiated Merck grant on cost-effectiveness of letermovir in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Another author, Graeme Forrest, reports a clinical study grant from Regeneron for inpatient monoclonals against SARS-CoV-2. All other authors report no conflicts of interest. The study was independently supported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A statement by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, published online in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, offers health care providers guidelines on how to prevent inappropriate antibiotic use in future pandemics and to avoid some of the negative scenarios that have been seen with COVID-19.

According to the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention,

The culprit might be the widespread antibiotic overprescription during the current pandemic. A 2022 meta-analysis revealed that in high-income countries, 58% of patients with COVID-19 were given antibiotics, whereas in lower- and middle-income countries, 89% of patients were put on such drugs. Some hospitals in Europe and the United States reported similarly elevated numbers, sometimes approaching 100%.

“We’ve lost control,” Natasha Pettit, PharmD, pharmacy director at University of Chicago Medicine, told this news organization. Dr. Pettit was not involved in the SHEA study. “Even if CDC didn’t come out with that data, I can tell you right now more of my time is spent trying to figure out how to manage these multi-drug–resistant infections, and we are running out of options for these patients,”

“Dealing with uncertainty, exhaustion, [and] critical illness in often young, otherwise healthy patients meant doctors wanted to do something for their patients,” said Tamar Barlam, MD, an infectious diseases expert at the Boston Medical Center who led the development of the SHEA white paper, in an interview.

That something often was a prescription for antibiotics, even without a clear indication that they were actually needed. A British study revealed that in times of pandemic uncertainty, clinicians often reached for antibiotics “just in case” and referred to conservative prescribing as “bravery.”

Studies have shown, however, that bacterial co-infections in COVID-19 are rare. A 2020 meta-analysis of 24 studies concluded that only 3.5% of patients had a bacterial co-infection on presentation, and 14.3% had a secondary infection. Similar patterns had previously been observed in other viral outbreaks. Research on MERS-CoV, for example, documented only 1% of patients with a bacterial co-infection on admission. During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, that number was 12% of non–ICU hospitalized patients.

Yet, according to Dr. Pettit, even when such data became available, it didn’t necessarily change prescribing patterns. “Information was coming at us so quickly, I think the providers didn’t have a moment to see the data, to understand what it meant for their prescribing. Having external guidance earlier on would have been hugely helpful,” she told this news organization.

That’s where the newly published SHEA statement comes in: It outlines recommendations on when to prescribe antibiotics during a respiratory viral pandemic, what tests to order, and when to de-escalate or discontinue the treatment. These recommendations include, for instance, advice to not trust inflammatory markers as reliable indicators of bacterial or fungal infection and to not use procalcitonin routinely to aid in the decision to initiate antibiotics.

According to Dr. Barlam, one of the crucial lessons here is that if clinicians see patients with symptoms that are consistent with the current pandemic, they should trust their own impressions and avoid reaching for antimicrobials “just in case.”

Another important lesson is that antibiotic stewardship programs have a huge role to play during pandemics. They should not only monitor prescribing but also compile new information on bacterial co-infections as it gets released and make sure it reaches the clinicians in a clear form.

Evidence suggests that such programs and guidelines do work to limit unnecessary antibiotic use. In one medical center in Chicago, for example, before recommendations on when to initiate and discontinue antimicrobials were released, over 74% of COVID-19 patients received antibiotics. After guidelines were put in place, the use of such drugs fell to 42%.

Dr. Pettit believes, however, that it’s important not to leave each medical center to its own devices. “Hindsight is always twenty-twenty,” she said, “but I think it would be great that, if we start hearing about a pathogen that might lead to another pandemic, we should have a mechanism in place to call together an expert body to get guidance for how antimicrobial stewardship programs should get involved.”

One of the authors of the SHEA statement, Susan Seo, reports an investigator-initiated Merck grant on cost-effectiveness of letermovir in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Another author, Graeme Forrest, reports a clinical study grant from Regeneron for inpatient monoclonals against SARS-CoV-2. All other authors report no conflicts of interest. The study was independently supported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A statement by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, published online in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, offers health care providers guidelines on how to prevent inappropriate antibiotic use in future pandemics and to avoid some of the negative scenarios that have been seen with COVID-19.

According to the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention,

The culprit might be the widespread antibiotic overprescription during the current pandemic. A 2022 meta-analysis revealed that in high-income countries, 58% of patients with COVID-19 were given antibiotics, whereas in lower- and middle-income countries, 89% of patients were put on such drugs. Some hospitals in Europe and the United States reported similarly elevated numbers, sometimes approaching 100%.

“We’ve lost control,” Natasha Pettit, PharmD, pharmacy director at University of Chicago Medicine, told this news organization. Dr. Pettit was not involved in the SHEA study. “Even if CDC didn’t come out with that data, I can tell you right now more of my time is spent trying to figure out how to manage these multi-drug–resistant infections, and we are running out of options for these patients,”

“Dealing with uncertainty, exhaustion, [and] critical illness in often young, otherwise healthy patients meant doctors wanted to do something for their patients,” said Tamar Barlam, MD, an infectious diseases expert at the Boston Medical Center who led the development of the SHEA white paper, in an interview.

That something often was a prescription for antibiotics, even without a clear indication that they were actually needed. A British study revealed that in times of pandemic uncertainty, clinicians often reached for antibiotics “just in case” and referred to conservative prescribing as “bravery.”

Studies have shown, however, that bacterial co-infections in COVID-19 are rare. A 2020 meta-analysis of 24 studies concluded that only 3.5% of patients had a bacterial co-infection on presentation, and 14.3% had a secondary infection. Similar patterns had previously been observed in other viral outbreaks. Research on MERS-CoV, for example, documented only 1% of patients with a bacterial co-infection on admission. During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, that number was 12% of non–ICU hospitalized patients.

Yet, according to Dr. Pettit, even when such data became available, it didn’t necessarily change prescribing patterns. “Information was coming at us so quickly, I think the providers didn’t have a moment to see the data, to understand what it meant for their prescribing. Having external guidance earlier on would have been hugely helpful,” she told this news organization.

That’s where the newly published SHEA statement comes in: It outlines recommendations on when to prescribe antibiotics during a respiratory viral pandemic, what tests to order, and when to de-escalate or discontinue the treatment. These recommendations include, for instance, advice to not trust inflammatory markers as reliable indicators of bacterial or fungal infection and to not use procalcitonin routinely to aid in the decision to initiate antibiotics.

According to Dr. Barlam, one of the crucial lessons here is that if clinicians see patients with symptoms that are consistent with the current pandemic, they should trust their own impressions and avoid reaching for antimicrobials “just in case.”

Another important lesson is that antibiotic stewardship programs have a huge role to play during pandemics. They should not only monitor prescribing but also compile new information on bacterial co-infections as it gets released and make sure it reaches the clinicians in a clear form.

Evidence suggests that such programs and guidelines do work to limit unnecessary antibiotic use. In one medical center in Chicago, for example, before recommendations on when to initiate and discontinue antimicrobials were released, over 74% of COVID-19 patients received antibiotics. After guidelines were put in place, the use of such drugs fell to 42%.

Dr. Pettit believes, however, that it’s important not to leave each medical center to its own devices. “Hindsight is always twenty-twenty,” she said, “but I think it would be great that, if we start hearing about a pathogen that might lead to another pandemic, we should have a mechanism in place to call together an expert body to get guidance for how antimicrobial stewardship programs should get involved.”

One of the authors of the SHEA statement, Susan Seo, reports an investigator-initiated Merck grant on cost-effectiveness of letermovir in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Another author, Graeme Forrest, reports a clinical study grant from Regeneron for inpatient monoclonals against SARS-CoV-2. All other authors report no conflicts of interest. The study was independently supported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM INFECTION CONTROL & HOSPITAL EPIDEMIOLOGY

Hep C, HIV coinfection tied to higher MI risk with age

, a new analysis suggests.

By contrast, the risk increases by 30% every 10 years among PWH without HCV infection.

“There is other evidence that suggests people with HIV and HCV have a greater burden of negative health outcomes,” senior author Keri N. Althoff, PhD, MPH, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, said in an interview. “But the magnitude of ‘greater’ was bigger than I expected.”

“Understanding the difference HCV can make in the risk of MI with increasing age among those with – compared to without – HCV is an important step for understanding additional potential benefits of HCV treatment (among PWH),” she said.

The amplified risk with age occurred even though, overall, the association between HCV coinfection and increased risk of type 1 myocardial infarction (T1MI) was not significant, the analysis showed.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

How age counts

Dr. Althoff and colleagues analyzed data from 23,361 PWH aged 40-79 who had initiated antiretroviral therapy between 2000 and 2017. The primary outcome was T1MI.

A total of 4,677 participants (20%) had HCV. Eighty-nine T1MIs occurred among PWH with HCV (1.9%) vs. 314 among PWH without HCV (1.7%). In adjusted analyses, HCV was not associated with increased T1MI risk (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.98).

However, the risk of T1MI increased with age and was augmented in those with HCV (aHR per 10-year increase in age, 1.85) vs. those without HCV (aHR, 1.30).

Specifically, compared with those without HCV, the estimated T1MI risk was 17% higher among 50- to 59-year-olds with HCV and 77% higher among those 60 and older; neither association was statistically significant, although the authors suggest this probably was because of the smaller number of participants in the older age categories.

Even without HCV, the risk of T1MI increased in participants who had traditional risk factors. The risk was significantly higher among PWH aged 40-49 with diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, protease inhibitor (PI) use, and smoking, whereas among PWH aged 50-59, the T1MI risk was significantly greater among those with hypertension, PI use, and smoking.

Among those aged 60 or older, hypertension and low CD4 counts were associated with a significantly increased T1MI risk.

“Clinicians providing health care to people with HIV should know their patients’ HCV status,” Dr. Althoff said, “and provide support regarding HCV treatment and ways to reduce their cardiovascular risk, including smoking cessation, reaching and maintaining a healthy BMI, and substance use treatment.”

Truly additive?

American Heart Association expert volunteer Nieca Goldberg, MD, a clinical associate professor of medicine at New York University and medical director of Atria NY, said the increased T1MI risk with coinfection “makes sense” because both HIV and HCV are linked to inflammation.

However, she said in an interview, “the fact that the authors didn’t control for other, more traditional heart attack risk factors is a limitation. I would like to see a study that takes other risk factors into consideration to see if HCV is truly additive.”

Meanwhile, like Dr. Althoff, she said, “Clinicians should be taking a careful history that includes chronic infections as well as traditional heart risk factors.”

Additional studies are needed, Dr. Althoff agreed. “There are two paths we are keenly interested in pursuing. The first is understanding how metabolic risk factors for MI change after HCV treatment. We are working on this.”

“Ultimately,” she said, “we want to compare MI risk in people with HIV who had successful HCV treatment to those who have not had successful HCV treatment.”

In their current study, they had nearly 2 decades of follow-up, she noted. “Although we don’t need to wait that long, we would like to have close to a decade of potential follow-up time (since 2016, when sofosbuvir/velpatasvir became available) so that we have a large enough sample size to observe a sufficient number of MIs within the first 5 years after successful HCV treatment.”

No commercial funding or relevant disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new analysis suggests.

By contrast, the risk increases by 30% every 10 years among PWH without HCV infection.

“There is other evidence that suggests people with HIV and HCV have a greater burden of negative health outcomes,” senior author Keri N. Althoff, PhD, MPH, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, said in an interview. “But the magnitude of ‘greater’ was bigger than I expected.”

“Understanding the difference HCV can make in the risk of MI with increasing age among those with – compared to without – HCV is an important step for understanding additional potential benefits of HCV treatment (among PWH),” she said.

The amplified risk with age occurred even though, overall, the association between HCV coinfection and increased risk of type 1 myocardial infarction (T1MI) was not significant, the analysis showed.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

How age counts

Dr. Althoff and colleagues analyzed data from 23,361 PWH aged 40-79 who had initiated antiretroviral therapy between 2000 and 2017. The primary outcome was T1MI.

A total of 4,677 participants (20%) had HCV. Eighty-nine T1MIs occurred among PWH with HCV (1.9%) vs. 314 among PWH without HCV (1.7%). In adjusted analyses, HCV was not associated with increased T1MI risk (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.98).

However, the risk of T1MI increased with age and was augmented in those with HCV (aHR per 10-year increase in age, 1.85) vs. those without HCV (aHR, 1.30).

Specifically, compared with those without HCV, the estimated T1MI risk was 17% higher among 50- to 59-year-olds with HCV and 77% higher among those 60 and older; neither association was statistically significant, although the authors suggest this probably was because of the smaller number of participants in the older age categories.

Even without HCV, the risk of T1MI increased in participants who had traditional risk factors. The risk was significantly higher among PWH aged 40-49 with diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, protease inhibitor (PI) use, and smoking, whereas among PWH aged 50-59, the T1MI risk was significantly greater among those with hypertension, PI use, and smoking.

Among those aged 60 or older, hypertension and low CD4 counts were associated with a significantly increased T1MI risk.

“Clinicians providing health care to people with HIV should know their patients’ HCV status,” Dr. Althoff said, “and provide support regarding HCV treatment and ways to reduce their cardiovascular risk, including smoking cessation, reaching and maintaining a healthy BMI, and substance use treatment.”

Truly additive?

American Heart Association expert volunteer Nieca Goldberg, MD, a clinical associate professor of medicine at New York University and medical director of Atria NY, said the increased T1MI risk with coinfection “makes sense” because both HIV and HCV are linked to inflammation.

However, she said in an interview, “the fact that the authors didn’t control for other, more traditional heart attack risk factors is a limitation. I would like to see a study that takes other risk factors into consideration to see if HCV is truly additive.”

Meanwhile, like Dr. Althoff, she said, “Clinicians should be taking a careful history that includes chronic infections as well as traditional heart risk factors.”

Additional studies are needed, Dr. Althoff agreed. “There are two paths we are keenly interested in pursuing. The first is understanding how metabolic risk factors for MI change after HCV treatment. We are working on this.”

“Ultimately,” she said, “we want to compare MI risk in people with HIV who had successful HCV treatment to those who have not had successful HCV treatment.”

In their current study, they had nearly 2 decades of follow-up, she noted. “Although we don’t need to wait that long, we would like to have close to a decade of potential follow-up time (since 2016, when sofosbuvir/velpatasvir became available) so that we have a large enough sample size to observe a sufficient number of MIs within the first 5 years after successful HCV treatment.”

No commercial funding or relevant disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new analysis suggests.

By contrast, the risk increases by 30% every 10 years among PWH without HCV infection.

“There is other evidence that suggests people with HIV and HCV have a greater burden of negative health outcomes,” senior author Keri N. Althoff, PhD, MPH, of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, said in an interview. “But the magnitude of ‘greater’ was bigger than I expected.”

“Understanding the difference HCV can make in the risk of MI with increasing age among those with – compared to without – HCV is an important step for understanding additional potential benefits of HCV treatment (among PWH),” she said.

The amplified risk with age occurred even though, overall, the association between HCV coinfection and increased risk of type 1 myocardial infarction (T1MI) was not significant, the analysis showed.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

How age counts

Dr. Althoff and colleagues analyzed data from 23,361 PWH aged 40-79 who had initiated antiretroviral therapy between 2000 and 2017. The primary outcome was T1MI.

A total of 4,677 participants (20%) had HCV. Eighty-nine T1MIs occurred among PWH with HCV (1.9%) vs. 314 among PWH without HCV (1.7%). In adjusted analyses, HCV was not associated with increased T1MI risk (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.98).

However, the risk of T1MI increased with age and was augmented in those with HCV (aHR per 10-year increase in age, 1.85) vs. those without HCV (aHR, 1.30).

Specifically, compared with those without HCV, the estimated T1MI risk was 17% higher among 50- to 59-year-olds with HCV and 77% higher among those 60 and older; neither association was statistically significant, although the authors suggest this probably was because of the smaller number of participants in the older age categories.

Even without HCV, the risk of T1MI increased in participants who had traditional risk factors. The risk was significantly higher among PWH aged 40-49 with diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, protease inhibitor (PI) use, and smoking, whereas among PWH aged 50-59, the T1MI risk was significantly greater among those with hypertension, PI use, and smoking.

Among those aged 60 or older, hypertension and low CD4 counts were associated with a significantly increased T1MI risk.

“Clinicians providing health care to people with HIV should know their patients’ HCV status,” Dr. Althoff said, “and provide support regarding HCV treatment and ways to reduce their cardiovascular risk, including smoking cessation, reaching and maintaining a healthy BMI, and substance use treatment.”

Truly additive?

American Heart Association expert volunteer Nieca Goldberg, MD, a clinical associate professor of medicine at New York University and medical director of Atria NY, said the increased T1MI risk with coinfection “makes sense” because both HIV and HCV are linked to inflammation.

However, she said in an interview, “the fact that the authors didn’t control for other, more traditional heart attack risk factors is a limitation. I would like to see a study that takes other risk factors into consideration to see if HCV is truly additive.”

Meanwhile, like Dr. Althoff, she said, “Clinicians should be taking a careful history that includes chronic infections as well as traditional heart risk factors.”

Additional studies are needed, Dr. Althoff agreed. “There are two paths we are keenly interested in pursuing. The first is understanding how metabolic risk factors for MI change after HCV treatment. We are working on this.”

“Ultimately,” she said, “we want to compare MI risk in people with HIV who had successful HCV treatment to those who have not had successful HCV treatment.”

In their current study, they had nearly 2 decades of follow-up, she noted. “Although we don’t need to wait that long, we would like to have close to a decade of potential follow-up time (since 2016, when sofosbuvir/velpatasvir became available) so that we have a large enough sample size to observe a sufficient number of MIs within the first 5 years after successful HCV treatment.”

No commercial funding or relevant disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Early bird gets the worm, night owl gets the diabetes

Metabolism a player in circadian rhythm section

Are you an early bird, or do you wake up and stare at your phone, wondering why you were up watching “The Crown” until 3 a.m.? Recent research suggests that people who wake up earlier tend to be more active during the day and burn more fat than those who sleep in. Fat builds up in the night owls, putting them at higher risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

The study gives physicians something to think about when assessing a patient’s risk factors. “This could help medical professionals consider another behavioral factor contributing to disease risk,” Steven Malin, PhD, lead author of the study and expert in metabolism at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., said in The Guardian.

For the research, 51 participants were divided into night owls and early birds, depending on their answers to a questionnaire. They were examined, monitored for a week, and assessed while doing various activities. Those who woke up early tended to be more sensitive to insulin and burned off fat faster than those who woke up late, the researchers explained.

“Night owls are reported to have a higher risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease when compared with early birds,” Dr. Malin said. “A potential explanation is they become misaligned with their circadian rhythm for various reasons, but most notably among adults would be work.”

We all know that we may not be at our best when we throw off our internal clocks by going to sleep late and waking up early. Think about that next time you start another episode on Netflix at 2:57 a.m.

Mosquitoes, chemical cocktails, and glass sock beads

We all know that mosquitoes are annoying little disease vectors with a taste for human blood. One of the less-known things about mosquitoes is what attracts them to humans in the first place. It’s so less known that, until now, it was unknown. Oh sure, we knew that odor was involved, and that lactic acid was part of the odor equation, but what are the specific chemicals? Well, there’s carbon dioxide … and ammonia. Those were already known.

Ring Cardé, PhD, an entomologist at the University of California, Riverside, wasn’t convinced. “I suspected there was something undiscovered about the chemistry of odors luring the yellow fever mosquito. I wanted to nail down the exact blend,” he said in a statement from the university.

Dr. Cardé and his associates eventually figured out that the exact chemical cocktail attracting female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes was a combination of carbon dioxide plus two chemicals, 2-ketoglutaric acid and lactic acid. The odor from these chemicals enables mosquitoes to locate and land on their victim and “also encourages probing, the use of piercing mouthparts to find blood,” the university said.

This amazing destination of science is important, but we have to acknowledge the journey as well. To do that we turn to one of Dr. Cardé’s associates, Jan Bello, PhD, formerly of Cal-Riverside and now with insect pest control company Provivi. Turns out that 2-ketoglutaric acid is tricky stuff because the methods typically used to identify chemicals don’t work on it.

Dr. Bello employed a somewhat unorthodox chemical extraction method: He filled his socks with glass beads and walked around with the beads in his socks.

“Wearing the beads felt almost like a massage, like squeezing stress balls full of sand, but with your feet,” Dr. Bello said. “The most frustrating part of doing it for a long time is that they would get stuck in between your toes, so it would be uncomfortable after a while.”

We hate when science gets stuck between our toes, but we love it when scientists write their own punchlines.

The MS drugs are better down where it’s wetter, take it from me

The myth of the mermaid is one with hundreds, if not thousands, of years of history. The ancient Greeks had the mythological siren, while the Babylonians depicted kulullû (which were mermen – never let the Babylonians be known as noninclusive) in artwork as far back as 1600 BC. Cultures as far flung as Japan, southern Africa, and New Zealand have folkloric figures similar to the mermaid. It is most decidedly not a creation of western Europe, Hans Christian Andersen, or Disney.

With that mild rant out of the way, let’s move to Germany and a group of researchers from the University of Bonn, who have not created a mermaid. They did, however, add human genes to a zebrafish for research purposes, which feels uncomfortably close. Nothing better than unholy animal-human hybrids, right?

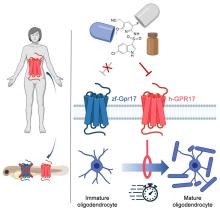

Stick with us here, because the researchers did have a good reason for their gene splicing. Zebrafish and humans both have the GPR17 receptor, which is highly active in nerve tissue. When GPR17 is overactivated, diseases such as multiple sclerosis can develop. Because the zebrafish has this receptor, which performs the same function in its body as in ours, it’s a prime candidate for replacement. Also, zebrafish larvae are transparent, which makes it very easy to observe a drug working.

That said, fish and humans are very far apart, genetically speaking. Big shock right there. But by replacing their GPR17 receptor with ours, the scientists have created a fish that we could test drug candidates on and be assured that they would also work on humans. Actually testing drugs for MS on these humanized zebrafish was beyond the scope of the study, but the researchers said that the new genes function normally in the fish larvae, making them a promising new avenue for MS drug development.

Can we all promise not to tell Disney that human DNA can be spliced into a fish without consequence? Otherwise, we’re just going to have to sit through another “Little Mermaid” adaptation in 30 years, this one in super live-action featuring actual, real-life mermaids. And we’re not ready for that level of man-made horror just yet.

Beware of the fly vomit

Picture this: You’re outside at a picnic or barbecue, loading a plate with food. In a brief moment of conversation a fly lands right on top of your sandwich. You shoo it away and think nothing more of it, eating the sandwich anyway. We’ve all been there.

A recent study is making us think again.

John Stoffolano, an entomology professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, claims that too much attention has been focused on pathogen transmission by the biting, blood-feeding flies when really we should be taking note of the nonbiting, or synanthropic, flies we live with, which may have a greater impact on the transmission of pathogens right in our own homes.

Sure, blood-feeding flies can spread pathogens directly, but house flies vomit every time they land on something. Think about that.

The fly that sneakily swooped into your house from a tear in your window screen has just been outside in the neighbor’s garbage or sitting on dog poop and now has who knows what filling its crop, the tank in their body that serves as “a place to store food before it makes its way into the digestive tract where it will get turned into energy for the fly,” Dr. Stoffolano explained in a written statement.

Did that fly land right on the baked potato you were prepping for dinner before you shooed it away? Guess what? Before flying off it emitted excess water that has pathogens from whatever was in its crop. We don’t want to say your potato might have dog poop on it, but you get the idea. The crop doesn’t have a ton of digestive enzymes that would help neutralize pathogens, so whatever that fly regurgitated before buzzing off is still around for you to ingest and there’s not much you can do about it.

More research needs to be done about flies, but at the very least this study should make you think twice before eating that baked potato after a fly has been there.

Metabolism a player in circadian rhythm section

Are you an early bird, or do you wake up and stare at your phone, wondering why you were up watching “The Crown” until 3 a.m.? Recent research suggests that people who wake up earlier tend to be more active during the day and burn more fat than those who sleep in. Fat builds up in the night owls, putting them at higher risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

The study gives physicians something to think about when assessing a patient’s risk factors. “This could help medical professionals consider another behavioral factor contributing to disease risk,” Steven Malin, PhD, lead author of the study and expert in metabolism at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., said in The Guardian.

For the research, 51 participants were divided into night owls and early birds, depending on their answers to a questionnaire. They were examined, monitored for a week, and assessed while doing various activities. Those who woke up early tended to be more sensitive to insulin and burned off fat faster than those who woke up late, the researchers explained.

“Night owls are reported to have a higher risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease when compared with early birds,” Dr. Malin said. “A potential explanation is they become misaligned with their circadian rhythm for various reasons, but most notably among adults would be work.”

We all know that we may not be at our best when we throw off our internal clocks by going to sleep late and waking up early. Think about that next time you start another episode on Netflix at 2:57 a.m.

Mosquitoes, chemical cocktails, and glass sock beads

We all know that mosquitoes are annoying little disease vectors with a taste for human blood. One of the less-known things about mosquitoes is what attracts them to humans in the first place. It’s so less known that, until now, it was unknown. Oh sure, we knew that odor was involved, and that lactic acid was part of the odor equation, but what are the specific chemicals? Well, there’s carbon dioxide … and ammonia. Those were already known.

Ring Cardé, PhD, an entomologist at the University of California, Riverside, wasn’t convinced. “I suspected there was something undiscovered about the chemistry of odors luring the yellow fever mosquito. I wanted to nail down the exact blend,” he said in a statement from the university.

Dr. Cardé and his associates eventually figured out that the exact chemical cocktail attracting female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes was a combination of carbon dioxide plus two chemicals, 2-ketoglutaric acid and lactic acid. The odor from these chemicals enables mosquitoes to locate and land on their victim and “also encourages probing, the use of piercing mouthparts to find blood,” the university said.

This amazing destination of science is important, but we have to acknowledge the journey as well. To do that we turn to one of Dr. Cardé’s associates, Jan Bello, PhD, formerly of Cal-Riverside and now with insect pest control company Provivi. Turns out that 2-ketoglutaric acid is tricky stuff because the methods typically used to identify chemicals don’t work on it.

Dr. Bello employed a somewhat unorthodox chemical extraction method: He filled his socks with glass beads and walked around with the beads in his socks.

“Wearing the beads felt almost like a massage, like squeezing stress balls full of sand, but with your feet,” Dr. Bello said. “The most frustrating part of doing it for a long time is that they would get stuck in between your toes, so it would be uncomfortable after a while.”

We hate when science gets stuck between our toes, but we love it when scientists write their own punchlines.

The MS drugs are better down where it’s wetter, take it from me

The myth of the mermaid is one with hundreds, if not thousands, of years of history. The ancient Greeks had the mythological siren, while the Babylonians depicted kulullû (which were mermen – never let the Babylonians be known as noninclusive) in artwork as far back as 1600 BC. Cultures as far flung as Japan, southern Africa, and New Zealand have folkloric figures similar to the mermaid. It is most decidedly not a creation of western Europe, Hans Christian Andersen, or Disney.

With that mild rant out of the way, let’s move to Germany and a group of researchers from the University of Bonn, who have not created a mermaid. They did, however, add human genes to a zebrafish for research purposes, which feels uncomfortably close. Nothing better than unholy animal-human hybrids, right?

Stick with us here, because the researchers did have a good reason for their gene splicing. Zebrafish and humans both have the GPR17 receptor, which is highly active in nerve tissue. When GPR17 is overactivated, diseases such as multiple sclerosis can develop. Because the zebrafish has this receptor, which performs the same function in its body as in ours, it’s a prime candidate for replacement. Also, zebrafish larvae are transparent, which makes it very easy to observe a drug working.

That said, fish and humans are very far apart, genetically speaking. Big shock right there. But by replacing their GPR17 receptor with ours, the scientists have created a fish that we could test drug candidates on and be assured that they would also work on humans. Actually testing drugs for MS on these humanized zebrafish was beyond the scope of the study, but the researchers said that the new genes function normally in the fish larvae, making them a promising new avenue for MS drug development.

Can we all promise not to tell Disney that human DNA can be spliced into a fish without consequence? Otherwise, we’re just going to have to sit through another “Little Mermaid” adaptation in 30 years, this one in super live-action featuring actual, real-life mermaids. And we’re not ready for that level of man-made horror just yet.

Beware of the fly vomit

Picture this: You’re outside at a picnic or barbecue, loading a plate with food. In a brief moment of conversation a fly lands right on top of your sandwich. You shoo it away and think nothing more of it, eating the sandwich anyway. We’ve all been there.

A recent study is making us think again.

John Stoffolano, an entomology professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, claims that too much attention has been focused on pathogen transmission by the biting, blood-feeding flies when really we should be taking note of the nonbiting, or synanthropic, flies we live with, which may have a greater impact on the transmission of pathogens right in our own homes.

Sure, blood-feeding flies can spread pathogens directly, but house flies vomit every time they land on something. Think about that.

The fly that sneakily swooped into your house from a tear in your window screen has just been outside in the neighbor’s garbage or sitting on dog poop and now has who knows what filling its crop, the tank in their body that serves as “a place to store food before it makes its way into the digestive tract where it will get turned into energy for the fly,” Dr. Stoffolano explained in a written statement.

Did that fly land right on the baked potato you were prepping for dinner before you shooed it away? Guess what? Before flying off it emitted excess water that has pathogens from whatever was in its crop. We don’t want to say your potato might have dog poop on it, but you get the idea. The crop doesn’t have a ton of digestive enzymes that would help neutralize pathogens, so whatever that fly regurgitated before buzzing off is still around for you to ingest and there’s not much you can do about it.

More research needs to be done about flies, but at the very least this study should make you think twice before eating that baked potato after a fly has been there.

Metabolism a player in circadian rhythm section

Are you an early bird, or do you wake up and stare at your phone, wondering why you were up watching “The Crown” until 3 a.m.? Recent research suggests that people who wake up earlier tend to be more active during the day and burn more fat than those who sleep in. Fat builds up in the night owls, putting them at higher risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

The study gives physicians something to think about when assessing a patient’s risk factors. “This could help medical professionals consider another behavioral factor contributing to disease risk,” Steven Malin, PhD, lead author of the study and expert in metabolism at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., said in The Guardian.

For the research, 51 participants were divided into night owls and early birds, depending on their answers to a questionnaire. They were examined, monitored for a week, and assessed while doing various activities. Those who woke up early tended to be more sensitive to insulin and burned off fat faster than those who woke up late, the researchers explained.

“Night owls are reported to have a higher risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease when compared with early birds,” Dr. Malin said. “A potential explanation is they become misaligned with their circadian rhythm for various reasons, but most notably among adults would be work.”

We all know that we may not be at our best when we throw off our internal clocks by going to sleep late and waking up early. Think about that next time you start another episode on Netflix at 2:57 a.m.

Mosquitoes, chemical cocktails, and glass sock beads

We all know that mosquitoes are annoying little disease vectors with a taste for human blood. One of the less-known things about mosquitoes is what attracts them to humans in the first place. It’s so less known that, until now, it was unknown. Oh sure, we knew that odor was involved, and that lactic acid was part of the odor equation, but what are the specific chemicals? Well, there’s carbon dioxide … and ammonia. Those were already known.

Ring Cardé, PhD, an entomologist at the University of California, Riverside, wasn’t convinced. “I suspected there was something undiscovered about the chemistry of odors luring the yellow fever mosquito. I wanted to nail down the exact blend,” he said in a statement from the university.

Dr. Cardé and his associates eventually figured out that the exact chemical cocktail attracting female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes was a combination of carbon dioxide plus two chemicals, 2-ketoglutaric acid and lactic acid. The odor from these chemicals enables mosquitoes to locate and land on their victim and “also encourages probing, the use of piercing mouthparts to find blood,” the university said.

This amazing destination of science is important, but we have to acknowledge the journey as well. To do that we turn to one of Dr. Cardé’s associates, Jan Bello, PhD, formerly of Cal-Riverside and now with insect pest control company Provivi. Turns out that 2-ketoglutaric acid is tricky stuff because the methods typically used to identify chemicals don’t work on it.

Dr. Bello employed a somewhat unorthodox chemical extraction method: He filled his socks with glass beads and walked around with the beads in his socks.

“Wearing the beads felt almost like a massage, like squeezing stress balls full of sand, but with your feet,” Dr. Bello said. “The most frustrating part of doing it for a long time is that they would get stuck in between your toes, so it would be uncomfortable after a while.”

We hate when science gets stuck between our toes, but we love it when scientists write their own punchlines.

The MS drugs are better down where it’s wetter, take it from me

The myth of the mermaid is one with hundreds, if not thousands, of years of history. The ancient Greeks had the mythological siren, while the Babylonians depicted kulullû (which were mermen – never let the Babylonians be known as noninclusive) in artwork as far back as 1600 BC. Cultures as far flung as Japan, southern Africa, and New Zealand have folkloric figures similar to the mermaid. It is most decidedly not a creation of western Europe, Hans Christian Andersen, or Disney.

With that mild rant out of the way, let’s move to Germany and a group of researchers from the University of Bonn, who have not created a mermaid. They did, however, add human genes to a zebrafish for research purposes, which feels uncomfortably close. Nothing better than unholy animal-human hybrids, right?

Stick with us here, because the researchers did have a good reason for their gene splicing. Zebrafish and humans both have the GPR17 receptor, which is highly active in nerve tissue. When GPR17 is overactivated, diseases such as multiple sclerosis can develop. Because the zebrafish has this receptor, which performs the same function in its body as in ours, it’s a prime candidate for replacement. Also, zebrafish larvae are transparent, which makes it very easy to observe a drug working.

That said, fish and humans are very far apart, genetically speaking. Big shock right there. But by replacing their GPR17 receptor with ours, the scientists have created a fish that we could test drug candidates on and be assured that they would also work on humans. Actually testing drugs for MS on these humanized zebrafish was beyond the scope of the study, but the researchers said that the new genes function normally in the fish larvae, making them a promising new avenue for MS drug development.

Can we all promise not to tell Disney that human DNA can be spliced into a fish without consequence? Otherwise, we’re just going to have to sit through another “Little Mermaid” adaptation in 30 years, this one in super live-action featuring actual, real-life mermaids. And we’re not ready for that level of man-made horror just yet.

Beware of the fly vomit

Picture this: You’re outside at a picnic or barbecue, loading a plate with food. In a brief moment of conversation a fly lands right on top of your sandwich. You shoo it away and think nothing more of it, eating the sandwich anyway. We’ve all been there.

A recent study is making us think again.

John Stoffolano, an entomology professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, claims that too much attention has been focused on pathogen transmission by the biting, blood-feeding flies when really we should be taking note of the nonbiting, or synanthropic, flies we live with, which may have a greater impact on the transmission of pathogens right in our own homes.

Sure, blood-feeding flies can spread pathogens directly, but house flies vomit every time they land on something. Think about that.

The fly that sneakily swooped into your house from a tear in your window screen has just been outside in the neighbor’s garbage or sitting on dog poop and now has who knows what filling its crop, the tank in their body that serves as “a place to store food before it makes its way into the digestive tract where it will get turned into energy for the fly,” Dr. Stoffolano explained in a written statement.

Did that fly land right on the baked potato you were prepping for dinner before you shooed it away? Guess what? Before flying off it emitted excess water that has pathogens from whatever was in its crop. We don’t want to say your potato might have dog poop on it, but you get the idea. The crop doesn’t have a ton of digestive enzymes that would help neutralize pathogens, so whatever that fly regurgitated before buzzing off is still around for you to ingest and there’s not much you can do about it.

More research needs to be done about flies, but at the very least this study should make you think twice before eating that baked potato after a fly has been there.

House passes prior authorization bill, Senate path unclear

The path through the U.S. Senate is not yet certain for a bill intended to speed the prior authorization process of insurer-run Medicare Advantage plans, despite the measure having breezed through the House.

House leaders opted to move the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2021 (HR 3173) without requiring a roll-call vote. The measure was passed on Sept. 14 by a voice vote, an approach used in general with only uncontroversial measures that have broad support. The bill has 191 Democratic and 135 Republican sponsors, representing about three-quarters of the members of the House.

“There is no reason that patients should be waiting for medically appropriate care, especially when we know that this can lead to worse outcomes,” Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) said in a Sept. 14 speech on the House floor. “The fundamental promise of Medicare Advantage is undermined when people are delaying care, getting sicker, and ultimately costing Medicare more money.”

Rep. Greg Murphy, MD (R-N.C.), spoke on the House floor that day as well, bringing up cases he has seen in his own urology practice in which prior authorization delays disrupted medical care. One patient wound up in the hospital with abscess after an insurer denied an antibiotic prescription, Rep. Murphy said.

But the Senate appears unlikely at this time to move the prior authorization bill as a standalone measure. Instead, the bill may become part of a larger legislative package focused on health care that the Senate Finance Committee intends to prepare later this year.

The House-passed bill would require insurer-run Medicare plans to respond to expedited requests for prior authorization of services within 24 hours and to other requests within 7 days. This bill also would establish an electronic program for prior authorizations and mandate increased transparency as to how insurers use this tool.

CBO: Cost of change would be billions

In seeking to mandate changes in prior authorization, lawmakers likely will need to contend with the issue of a $16 billion cumulative cost estimate for the bill from the Congressional Budget Office. Members of Congress often seek to offset new spending by pairing bills that add to expected costs for the federal government with ones expected to produce savings.

Unlike Rep. Blumenauer, Rep. Murphy, and other backers of the prior authorization streamlining bill, CBO staff estimates that making the mandated changes would raise federal spending, inasmuch as there would be “a greater use of services.”

On Sept. 14, CBO issued a one-page report on the costs of the bill. The CBO report concerns only the bill in question, as is common practice with the office’s estimates.

Prior authorization changes would begin in fiscal 2025 and would add $899 million in spending, or outlays, that year, CBO said. The annual costs from the streamlined prior authorization practices through fiscal 2026 to 2032 range from $1.6 billion to $2.7 billion.

Looking at the CBO estimate against a backdrop of total Medicare Advantage costs, though, may provide important context.

The increases in spending estimated by CBO may suggest that there would be little change in federal spending as a result of streamlining prior authorization practices. These estimates of increased annual spending of $1.6 billion–$2.7 billion are only a small fraction of the current annual cost of insurer-run Medicare, and they represent an even smaller share of the projected expense.

The federal government last year spent about $350 billion on insurer-run plans, excluding Part D drug plan payments, according to the Medicare Advisory Payment Commission (MedPAC).

As of 2021, about 27 million people were enrolled in these plans, accounting for about 46% of the total Medicare population. Enrollment has doubled since 2010, MedPAC said, and it is expected to continue to grow. By 2027, insurer-run Medicare could cover 50% of the program’s population, a figure that may reach 53% by 2031.

Federal payments to these plans will accelerate in the years ahead as insurers attract more people eligible for Medicare as customers. Payments to these private health plans could rise from an expected $418 billion this year to $940.6 billion by 2031, according to the most recent Medicare trustees report.

Good intentions, poor implementation?

Insurer-run Medicare has long enjoyed deep bipartisan support in Congress. That’s due in part to its potential for reducing spending on what are considered low-value treatments, or ones considered unlikely to provide a significant medical benefit, but Rep. Blumenauer is among the members of Congress who see insurer-run Medicare as a path for preserving the giant federal health program. Traditional Medicare has far fewer restrictions on services, which sometimes opens a path for tests and treatments that offer less value for patients.

“I believe that the way traditional fee-for-service Medicare operates is not sustainable and that Medicare Advantage is one of the tools we can use to demonstrate how we can incentivize value,” Rep. Blumenauer said on the House floor. “But this is only possible when the program operates as intended. I have been deeply concerned about the reports of delays in care” caused by the clunky prior authorization processes.

He highlighted a recent report from the internal watchdog group for the Department of Health & Human Services that raises concerns about denials of appropriate care. About 18% of a set of payment denials examined by the Office of Inspector General of HHS in April actually met Medicare coverage rules and plan billing rules.

“For patients and their families, being told that you need to wait longer for care that your doctor tells you that you need is incredibly frustrating and frightening,” Rep. Blumenauer said. “There’s no comfort to be found in the fact that your insurance company needs time to decide if your doctor is right.”

Trends in prior authorization

The CBO report does not provide detail on what kind of medical spending would increase under a streamlined prior authorization process in insurer-run Medicare plans.

From trends reported in prior authorization, though, two factors could be at play in what appear to be relatively small estimated increases in Medicare spending from streamlined prior authorization.

One is the work already underway to create less burdensome electronic systems for these requests, such as the Fast Prior Authorization Technology Highway initiative run by the trade association America’s Health Insurance Plans.

The other factor could be the number of cases in which prior authorization merely causes delays in treatments and tests and thus simply postpones spending while adding to clinicians’ administrative work.

An analysis of prior authorization requests for dermatologic practices affiliated with the University of Utah may represent an extreme example. In a report published in JAMA Dermatology in 2020, researchers described what happened with requests made during 1 month, September 2016.

The approval rate for procedures was 99.6% – 100% (95 of 95) for Mohs surgery, and 96% (130 of 131, with 4 additional cases pending) for excisions. These findings supported calls for simplifying prior authorization procedures, “perhaps first by eliminating unnecessary PAs [prior authorizations] and appeals,” Aaron M. Secrest, MD, PhD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and coauthors wrote in the article.

Still, there is some evidence that insurer-run Medicare policies reduce the use of low-value care.

In a study published in JAMA Health Forum, Emily Boudreau, PhD, of insurer Humana Inc, and coauthors from Tufts University, Boston, and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia investigated whether insurer-run Medicare could do a better job in reducing the amount of low-value care delivered than the traditional program. They analyzed a set of claims data from 2017 to 2019 for people enrolled in insurer-run and traditional Medicare.

They reported a rate of 23.07 low-value services provided per 100 people in insurer-run Medicare, compared with 25.39 for those in traditional Medicare. Some of the biggest differences reported in the article were in cancer screenings for older people.

As an example, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that women older than 65 years not be screened for cervical cancer if they have undergone adequate screening in the past and are not at high risk for cervical cancer. There was an annual count of 1.76 screenings for cervical cancer per 100 women older than 65 in the insurer-run Medicare group versus 3.18 for those in traditional Medicare.

The Better Medicare Alliance issued a statement in favor of the House passage of the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act.

In it, the group said the measure would “modernize prior authorization while protecting its essential function in facilitating safe, high-value, evidence-based care.” The alliance promotes use of insurer-run Medicare. The board of the Better Medicare Alliance includes executives who serve with firms that run Advantage plans as well as medical organizations and universities.

“With studies showing that up to one-quarter of all health care expenditures are wasted on services with no benefit to the patient, we need a robust, next-generation prior authorization program to deter low-value, and even harmful, care while protecting access to needed treatment and effective therapies,” said A. Mark Fendrick, MD, director of the University of Michigan’s Center for Value-Based Insurance Design in Ann Arbor, in a statement issued by the Better Medicare Alliance. He is a member of the group’s council of scholars.

On the House floor on September 14, Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-Calif.), said he has heard from former colleagues and his medical school classmates that they now spend as much as 40% of their time on administrative work. These distractions from patient care are helping drive physicians away from the practice of medicine.

Still, the internist defended the basic premise of prior authorization while strongly appealing for better systems of handling it.

“Yes, there is a role for prior authorization in limited cases. There is also a role to go back and retrospectively look at how care is being delivered,” Rep. Bera said. “But what is happening today is a travesty. It wasn’t the intention of prior authorization. It is a prior authorization process gone awry.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The path through the U.S. Senate is not yet certain for a bill intended to speed the prior authorization process of insurer-run Medicare Advantage plans, despite the measure having breezed through the House.

House leaders opted to move the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2021 (HR 3173) without requiring a roll-call vote. The measure was passed on Sept. 14 by a voice vote, an approach used in general with only uncontroversial measures that have broad support. The bill has 191 Democratic and 135 Republican sponsors, representing about three-quarters of the members of the House.

“There is no reason that patients should be waiting for medically appropriate care, especially when we know that this can lead to worse outcomes,” Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) said in a Sept. 14 speech on the House floor. “The fundamental promise of Medicare Advantage is undermined when people are delaying care, getting sicker, and ultimately costing Medicare more money.”

Rep. Greg Murphy, MD (R-N.C.), spoke on the House floor that day as well, bringing up cases he has seen in his own urology practice in which prior authorization delays disrupted medical care. One patient wound up in the hospital with abscess after an insurer denied an antibiotic prescription, Rep. Murphy said.

But the Senate appears unlikely at this time to move the prior authorization bill as a standalone measure. Instead, the bill may become part of a larger legislative package focused on health care that the Senate Finance Committee intends to prepare later this year.

The House-passed bill would require insurer-run Medicare plans to respond to expedited requests for prior authorization of services within 24 hours and to other requests within 7 days. This bill also would establish an electronic program for prior authorizations and mandate increased transparency as to how insurers use this tool.

CBO: Cost of change would be billions

In seeking to mandate changes in prior authorization, lawmakers likely will need to contend with the issue of a $16 billion cumulative cost estimate for the bill from the Congressional Budget Office. Members of Congress often seek to offset new spending by pairing bills that add to expected costs for the federal government with ones expected to produce savings.

Unlike Rep. Blumenauer, Rep. Murphy, and other backers of the prior authorization streamlining bill, CBO staff estimates that making the mandated changes would raise federal spending, inasmuch as there would be “a greater use of services.”

On Sept. 14, CBO issued a one-page report on the costs of the bill. The CBO report concerns only the bill in question, as is common practice with the office’s estimates.

Prior authorization changes would begin in fiscal 2025 and would add $899 million in spending, or outlays, that year, CBO said. The annual costs from the streamlined prior authorization practices through fiscal 2026 to 2032 range from $1.6 billion to $2.7 billion.

Looking at the CBO estimate against a backdrop of total Medicare Advantage costs, though, may provide important context.

The increases in spending estimated by CBO may suggest that there would be little change in federal spending as a result of streamlining prior authorization practices. These estimates of increased annual spending of $1.6 billion–$2.7 billion are only a small fraction of the current annual cost of insurer-run Medicare, and they represent an even smaller share of the projected expense.

The federal government last year spent about $350 billion on insurer-run plans, excluding Part D drug plan payments, according to the Medicare Advisory Payment Commission (MedPAC).

As of 2021, about 27 million people were enrolled in these plans, accounting for about 46% of the total Medicare population. Enrollment has doubled since 2010, MedPAC said, and it is expected to continue to grow. By 2027, insurer-run Medicare could cover 50% of the program’s population, a figure that may reach 53% by 2031.

Federal payments to these plans will accelerate in the years ahead as insurers attract more people eligible for Medicare as customers. Payments to these private health plans could rise from an expected $418 billion this year to $940.6 billion by 2031, according to the most recent Medicare trustees report.

Good intentions, poor implementation?

Insurer-run Medicare has long enjoyed deep bipartisan support in Congress. That’s due in part to its potential for reducing spending on what are considered low-value treatments, or ones considered unlikely to provide a significant medical benefit, but Rep. Blumenauer is among the members of Congress who see insurer-run Medicare as a path for preserving the giant federal health program. Traditional Medicare has far fewer restrictions on services, which sometimes opens a path for tests and treatments that offer less value for patients.

“I believe that the way traditional fee-for-service Medicare operates is not sustainable and that Medicare Advantage is one of the tools we can use to demonstrate how we can incentivize value,” Rep. Blumenauer said on the House floor. “But this is only possible when the program operates as intended. I have been deeply concerned about the reports of delays in care” caused by the clunky prior authorization processes.

He highlighted a recent report from the internal watchdog group for the Department of Health & Human Services that raises concerns about denials of appropriate care. About 18% of a set of payment denials examined by the Office of Inspector General of HHS in April actually met Medicare coverage rules and plan billing rules.

“For patients and their families, being told that you need to wait longer for care that your doctor tells you that you need is incredibly frustrating and frightening,” Rep. Blumenauer said. “There’s no comfort to be found in the fact that your insurance company needs time to decide if your doctor is right.”

Trends in prior authorization

The CBO report does not provide detail on what kind of medical spending would increase under a streamlined prior authorization process in insurer-run Medicare plans.

From trends reported in prior authorization, though, two factors could be at play in what appear to be relatively small estimated increases in Medicare spending from streamlined prior authorization.

One is the work already underway to create less burdensome electronic systems for these requests, such as the Fast Prior Authorization Technology Highway initiative run by the trade association America’s Health Insurance Plans.

The other factor could be the number of cases in which prior authorization merely causes delays in treatments and tests and thus simply postpones spending while adding to clinicians’ administrative work.

An analysis of prior authorization requests for dermatologic practices affiliated with the University of Utah may represent an extreme example. In a report published in JAMA Dermatology in 2020, researchers described what happened with requests made during 1 month, September 2016.

The approval rate for procedures was 99.6% – 100% (95 of 95) for Mohs surgery, and 96% (130 of 131, with 4 additional cases pending) for excisions. These findings supported calls for simplifying prior authorization procedures, “perhaps first by eliminating unnecessary PAs [prior authorizations] and appeals,” Aaron M. Secrest, MD, PhD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and coauthors wrote in the article.

Still, there is some evidence that insurer-run Medicare policies reduce the use of low-value care.

In a study published in JAMA Health Forum, Emily Boudreau, PhD, of insurer Humana Inc, and coauthors from Tufts University, Boston, and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia investigated whether insurer-run Medicare could do a better job in reducing the amount of low-value care delivered than the traditional program. They analyzed a set of claims data from 2017 to 2019 for people enrolled in insurer-run and traditional Medicare.

They reported a rate of 23.07 low-value services provided per 100 people in insurer-run Medicare, compared with 25.39 for those in traditional Medicare. Some of the biggest differences reported in the article were in cancer screenings for older people.

As an example, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that women older than 65 years not be screened for cervical cancer if they have undergone adequate screening in the past and are not at high risk for cervical cancer. There was an annual count of 1.76 screenings for cervical cancer per 100 women older than 65 in the insurer-run Medicare group versus 3.18 for those in traditional Medicare.

The Better Medicare Alliance issued a statement in favor of the House passage of the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act.

In it, the group said the measure would “modernize prior authorization while protecting its essential function in facilitating safe, high-value, evidence-based care.” The alliance promotes use of insurer-run Medicare. The board of the Better Medicare Alliance includes executives who serve with firms that run Advantage plans as well as medical organizations and universities.

“With studies showing that up to one-quarter of all health care expenditures are wasted on services with no benefit to the patient, we need a robust, next-generation prior authorization program to deter low-value, and even harmful, care while protecting access to needed treatment and effective therapies,” said A. Mark Fendrick, MD, director of the University of Michigan’s Center for Value-Based Insurance Design in Ann Arbor, in a statement issued by the Better Medicare Alliance. He is a member of the group’s council of scholars.

On the House floor on September 14, Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-Calif.), said he has heard from former colleagues and his medical school classmates that they now spend as much as 40% of their time on administrative work. These distractions from patient care are helping drive physicians away from the practice of medicine.

Still, the internist defended the basic premise of prior authorization while strongly appealing for better systems of handling it.

“Yes, there is a role for prior authorization in limited cases. There is also a role to go back and retrospectively look at how care is being delivered,” Rep. Bera said. “But what is happening today is a travesty. It wasn’t the intention of prior authorization. It is a prior authorization process gone awry.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The path through the U.S. Senate is not yet certain for a bill intended to speed the prior authorization process of insurer-run Medicare Advantage plans, despite the measure having breezed through the House.

House leaders opted to move the Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act of 2021 (HR 3173) without requiring a roll-call vote. The measure was passed on Sept. 14 by a voice vote, an approach used in general with only uncontroversial measures that have broad support. The bill has 191 Democratic and 135 Republican sponsors, representing about three-quarters of the members of the House.

“There is no reason that patients should be waiting for medically appropriate care, especially when we know that this can lead to worse outcomes,” Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) said in a Sept. 14 speech on the House floor. “The fundamental promise of Medicare Advantage is undermined when people are delaying care, getting sicker, and ultimately costing Medicare more money.”

Rep. Greg Murphy, MD (R-N.C.), spoke on the House floor that day as well, bringing up cases he has seen in his own urology practice in which prior authorization delays disrupted medical care. One patient wound up in the hospital with abscess after an insurer denied an antibiotic prescription, Rep. Murphy said.

But the Senate appears unlikely at this time to move the prior authorization bill as a standalone measure. Instead, the bill may become part of a larger legislative package focused on health care that the Senate Finance Committee intends to prepare later this year.

The House-passed bill would require insurer-run Medicare plans to respond to expedited requests for prior authorization of services within 24 hours and to other requests within 7 days. This bill also would establish an electronic program for prior authorizations and mandate increased transparency as to how insurers use this tool.

CBO: Cost of change would be billions

In seeking to mandate changes in prior authorization, lawmakers likely will need to contend with the issue of a $16 billion cumulative cost estimate for the bill from the Congressional Budget Office. Members of Congress often seek to offset new spending by pairing bills that add to expected costs for the federal government with ones expected to produce savings.

Unlike Rep. Blumenauer, Rep. Murphy, and other backers of the prior authorization streamlining bill, CBO staff estimates that making the mandated changes would raise federal spending, inasmuch as there would be “a greater use of services.”

On Sept. 14, CBO issued a one-page report on the costs of the bill. The CBO report concerns only the bill in question, as is common practice with the office’s estimates.

Prior authorization changes would begin in fiscal 2025 and would add $899 million in spending, or outlays, that year, CBO said. The annual costs from the streamlined prior authorization practices through fiscal 2026 to 2032 range from $1.6 billion to $2.7 billion.

Looking at the CBO estimate against a backdrop of total Medicare Advantage costs, though, may provide important context.

The increases in spending estimated by CBO may suggest that there would be little change in federal spending as a result of streamlining prior authorization practices. These estimates of increased annual spending of $1.6 billion–$2.7 billion are only a small fraction of the current annual cost of insurer-run Medicare, and they represent an even smaller share of the projected expense.

The federal government last year spent about $350 billion on insurer-run plans, excluding Part D drug plan payments, according to the Medicare Advisory Payment Commission (MedPAC).

As of 2021, about 27 million people were enrolled in these plans, accounting for about 46% of the total Medicare population. Enrollment has doubled since 2010, MedPAC said, and it is expected to continue to grow. By 2027, insurer-run Medicare could cover 50% of the program’s population, a figure that may reach 53% by 2031.

Federal payments to these plans will accelerate in the years ahead as insurers attract more people eligible for Medicare as customers. Payments to these private health plans could rise from an expected $418 billion this year to $940.6 billion by 2031, according to the most recent Medicare trustees report.

Good intentions, poor implementation?

Insurer-run Medicare has long enjoyed deep bipartisan support in Congress. That’s due in part to its potential for reducing spending on what are considered low-value treatments, or ones considered unlikely to provide a significant medical benefit, but Rep. Blumenauer is among the members of Congress who see insurer-run Medicare as a path for preserving the giant federal health program. Traditional Medicare has far fewer restrictions on services, which sometimes opens a path for tests and treatments that offer less value for patients.

“I believe that the way traditional fee-for-service Medicare operates is not sustainable and that Medicare Advantage is one of the tools we can use to demonstrate how we can incentivize value,” Rep. Blumenauer said on the House floor. “But this is only possible when the program operates as intended. I have been deeply concerned about the reports of delays in care” caused by the clunky prior authorization processes.

He highlighted a recent report from the internal watchdog group for the Department of Health & Human Services that raises concerns about denials of appropriate care. About 18% of a set of payment denials examined by the Office of Inspector General of HHS in April actually met Medicare coverage rules and plan billing rules.