User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Will a one-dose drug mean the end of sleeping sickness?

A single dose of oral acoziborole resulted in a greater than 95% cure or probable cure rate for human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), also known as sleeping sickness, according to results from a clinical trial testing a one-dose experimental drug.

The drug has “the potential to revolutionize treatment” for the disease, which remains endemic in sub-Saharan Africa, said Antoine Tarral, MD, head of the human African trypanosomiasis clinical program at the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative, based in Geneva, and senior author of the study, in a press release.

he told this news organization. “It’s the first drug we can use without hospitalization. ... All the previous medications needed hospitalization, and therefore we could not treat the population early before they started expressing symptoms.”

The World Health Organization “has been working for decades for such a possibility to implement a new strategy for this disease,” Dr. Tarral said.

Current (2019) WHO guidelines recommend oral fexinidazole as first-line treatment for any stage of the disease. The 10-day course often requires hospitalization and skilled staff. Previous recommendations required disease-staging with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sampling and 7 days of intramuscular pentamidine for early-stage disease or nifurtimox-eflornithine combination therapy (NECT) with hospitalization for late-stage disease.

By contrast, acoziborole, which was codeveloped by the DND initiative and Sanofi, “is administered in a single dose and is effective across every stage of the disease, thereby eliminating the many barriers currently in place for people most vulnerable to the diseases, such as invasive treatments and long travel distances to a hospital or clinic, and opening the door to screen-and-treat approaches at the village level,” Dr. Tarral said in the statement.

“Today, and in the future, we will have less and less support to do this long and costly diagnostic process and treatment in the hospital,” he said in an interview. “This development means we can go for a simple test and a simple treatment, which means we can meet the WHO 2030 goal for ending transmission of this disease.”

Results from the multicenter, prospective, open-label, single-arm, noncomparative, phase 2/3 study were published in The Lancet.

Pragmatic study design

Sleeping sickness is caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (gambiense HAT). It is transmitted by the tsetse fly and mostly fatal when left untreated.

The study enrolled 208 adults and adolescents (167 with late-stage, and 41 with early-stage or intermediate-stage disease) from 10 hospitals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Guinea. All patients were treated with acoziborole 960 mg – an unusual study design.

“Due to the substantial decline in incidence, enrolling patients with gambiense HAT into clinical trials is challenging,” the authors wrote. “Following advice from the European Medicines Agency, this study was designed as an open-label, single-arm trial with no comparator or control group.”

After 18 months of follow-up, treatment success, defined as absence of trypanosomes and less than 20 white blood cells per mcL of CSF, occurred in 159 (95.2%) of the late-stage patients, and 100% of the early- and intermediate-stage patients, “which was similar to the estimated historical results for NECT,” the authors noted.

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 21 (10%) of patients, “but none of these events were considered drug-related,” they added.

The DND initiative and the WHO are currently nearing completion of a much larger, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of acoziborole to “increase the safety database,” Dr. Tarral explained.

“Purists will say that acoziborole has not been evaluated according to current standards, because the study was not a randomized trial, there was no control group, and the number of participants was small,” said Jacques Pépin, MD, from the University of Sherbrooke (Que.), in a linked commentary.

“But these were difficult challenges to overcome, considering the drastic reduction in the number of patients with HAT and dispersion over a vast territory, particularly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. For these reasons, the authors took a pragmatic approach instead,” he wrote.

A potential new tool for eradication of sleeping sickness

“This is really an exciting development, which will be useful in the drive for eradication/interruption of transmission of this disease,” Dr. Pépin told this news organization.

Dr. Pépin treated around 1,000 trypanosomiasis patients during an outbreak in Zaire in the early 1980s. Because the asymptomatic incubation period for the disease can be several months or even years, “the core strategy for controlling the disease is active screening,” he said in an interview.

“You try to convince the whole population of endemic villages to show up on a given day, and then you have a mobile team of nurses who examine everybody, trying to find those with early trypanosomiasis. This includes physical examination for lymph nodes in the neck, but also a blood test whose results are available within minutes,” he said.

“Until now, these persons with a positive serology would undergo additional and labor-intensive examinations of blood to try to find trypanosomes and prove that they have the disease. So far those with a positive serology and negative parasitological assays (‘serological suspects’) were left untreated, because the treatments were toxic and cumbersome, and because a substantial but unknown proportion of these ‘suspects’ just have a false positive of their serological test, without having the disease,” Dr. Pépin said.

“Now with acoziborole, which seems to have little serious toxicity ... and can be given as a single-dose oral med, it might be reasonable to treat the ‘serological suspects,’ ” he said.

“Take it one step further, it might be possible to do the serological test only and treat all individuals with a positive serology without bothering to do parasitological assays. This is what they call ‘test-and-treat’ strategy. It would make sense, provided that we are sure that the drug is very well tolerated.”

Dr. Pépin added that he is “just slightly worried” about three patients described in the paper who had psychiatric adverse events 3 months after treatment. “If that happens to patients who indeed have trypanosomiasis, that’s a reasonable price to pay considering the toxicity of other drugs,” he said. “If that happens to serological suspects, many of whom don’t have any disease, this becomes a preoccupation.”

But Dr. Tarral said, “We have no indication that the drug can provoke psychiatric symptoms. In fact, the psychiatric symptoms did not emerge – they re-emerged after 3 months due to some patients’ refusal to be followed up.”

“We included patients in very advanced stages of the disease, and these symptoms are considered disease sequelae,” Dr. Tarral said. “The majority of patients who have such psychiatric symptoms need follow-up after treatment. If not, they can relapse very early. There were a lot of patients who had such symptoms and the investigators proposed they should be followed by a psychiatrist and some of them refused. And due to that only three of our patients had this relapse, and they were cured after psychiatric support.”

The study was funded through the DND initiative and was supported by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; UK Aid; the Federal Ministry of Education and Research through Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau, Germany; the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation; Médecins Sans Frontières; the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs; the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation; the Stavros Niarchos Foundation; the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation; and the Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria Foundation.

A number of study investigators, including Dr. Tarral, report employment at the DND initiative. Other investigators report fees from the DND initiative for the statistical report, consulting fees from CEMAG, D&A Pharma, Inventiva, and OT4B Pharma. The Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute acted as a service provider for the DND initiative by monitoring the study sites. Dr. Pépin declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A single dose of oral acoziborole resulted in a greater than 95% cure or probable cure rate for human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), also known as sleeping sickness, according to results from a clinical trial testing a one-dose experimental drug.

The drug has “the potential to revolutionize treatment” for the disease, which remains endemic in sub-Saharan Africa, said Antoine Tarral, MD, head of the human African trypanosomiasis clinical program at the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative, based in Geneva, and senior author of the study, in a press release.

he told this news organization. “It’s the first drug we can use without hospitalization. ... All the previous medications needed hospitalization, and therefore we could not treat the population early before they started expressing symptoms.”

The World Health Organization “has been working for decades for such a possibility to implement a new strategy for this disease,” Dr. Tarral said.

Current (2019) WHO guidelines recommend oral fexinidazole as first-line treatment for any stage of the disease. The 10-day course often requires hospitalization and skilled staff. Previous recommendations required disease-staging with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sampling and 7 days of intramuscular pentamidine for early-stage disease or nifurtimox-eflornithine combination therapy (NECT) with hospitalization for late-stage disease.

By contrast, acoziborole, which was codeveloped by the DND initiative and Sanofi, “is administered in a single dose and is effective across every stage of the disease, thereby eliminating the many barriers currently in place for people most vulnerable to the diseases, such as invasive treatments and long travel distances to a hospital or clinic, and opening the door to screen-and-treat approaches at the village level,” Dr. Tarral said in the statement.

“Today, and in the future, we will have less and less support to do this long and costly diagnostic process and treatment in the hospital,” he said in an interview. “This development means we can go for a simple test and a simple treatment, which means we can meet the WHO 2030 goal for ending transmission of this disease.”

Results from the multicenter, prospective, open-label, single-arm, noncomparative, phase 2/3 study were published in The Lancet.

Pragmatic study design

Sleeping sickness is caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (gambiense HAT). It is transmitted by the tsetse fly and mostly fatal when left untreated.

The study enrolled 208 adults and adolescents (167 with late-stage, and 41 with early-stage or intermediate-stage disease) from 10 hospitals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Guinea. All patients were treated with acoziborole 960 mg – an unusual study design.

“Due to the substantial decline in incidence, enrolling patients with gambiense HAT into clinical trials is challenging,” the authors wrote. “Following advice from the European Medicines Agency, this study was designed as an open-label, single-arm trial with no comparator or control group.”

After 18 months of follow-up, treatment success, defined as absence of trypanosomes and less than 20 white blood cells per mcL of CSF, occurred in 159 (95.2%) of the late-stage patients, and 100% of the early- and intermediate-stage patients, “which was similar to the estimated historical results for NECT,” the authors noted.

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 21 (10%) of patients, “but none of these events were considered drug-related,” they added.

The DND initiative and the WHO are currently nearing completion of a much larger, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of acoziborole to “increase the safety database,” Dr. Tarral explained.

“Purists will say that acoziborole has not been evaluated according to current standards, because the study was not a randomized trial, there was no control group, and the number of participants was small,” said Jacques Pépin, MD, from the University of Sherbrooke (Que.), in a linked commentary.

“But these were difficult challenges to overcome, considering the drastic reduction in the number of patients with HAT and dispersion over a vast territory, particularly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. For these reasons, the authors took a pragmatic approach instead,” he wrote.

A potential new tool for eradication of sleeping sickness

“This is really an exciting development, which will be useful in the drive for eradication/interruption of transmission of this disease,” Dr. Pépin told this news organization.

Dr. Pépin treated around 1,000 trypanosomiasis patients during an outbreak in Zaire in the early 1980s. Because the asymptomatic incubation period for the disease can be several months or even years, “the core strategy for controlling the disease is active screening,” he said in an interview.

“You try to convince the whole population of endemic villages to show up on a given day, and then you have a mobile team of nurses who examine everybody, trying to find those with early trypanosomiasis. This includes physical examination for lymph nodes in the neck, but also a blood test whose results are available within minutes,” he said.

“Until now, these persons with a positive serology would undergo additional and labor-intensive examinations of blood to try to find trypanosomes and prove that they have the disease. So far those with a positive serology and negative parasitological assays (‘serological suspects’) were left untreated, because the treatments were toxic and cumbersome, and because a substantial but unknown proportion of these ‘suspects’ just have a false positive of their serological test, without having the disease,” Dr. Pépin said.

“Now with acoziborole, which seems to have little serious toxicity ... and can be given as a single-dose oral med, it might be reasonable to treat the ‘serological suspects,’ ” he said.

“Take it one step further, it might be possible to do the serological test only and treat all individuals with a positive serology without bothering to do parasitological assays. This is what they call ‘test-and-treat’ strategy. It would make sense, provided that we are sure that the drug is very well tolerated.”

Dr. Pépin added that he is “just slightly worried” about three patients described in the paper who had psychiatric adverse events 3 months after treatment. “If that happens to patients who indeed have trypanosomiasis, that’s a reasonable price to pay considering the toxicity of other drugs,” he said. “If that happens to serological suspects, many of whom don’t have any disease, this becomes a preoccupation.”

But Dr. Tarral said, “We have no indication that the drug can provoke psychiatric symptoms. In fact, the psychiatric symptoms did not emerge – they re-emerged after 3 months due to some patients’ refusal to be followed up.”

“We included patients in very advanced stages of the disease, and these symptoms are considered disease sequelae,” Dr. Tarral said. “The majority of patients who have such psychiatric symptoms need follow-up after treatment. If not, they can relapse very early. There were a lot of patients who had such symptoms and the investigators proposed they should be followed by a psychiatrist and some of them refused. And due to that only three of our patients had this relapse, and they were cured after psychiatric support.”

The study was funded through the DND initiative and was supported by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; UK Aid; the Federal Ministry of Education and Research through Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau, Germany; the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation; Médecins Sans Frontières; the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs; the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation; the Stavros Niarchos Foundation; the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation; and the Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria Foundation.

A number of study investigators, including Dr. Tarral, report employment at the DND initiative. Other investigators report fees from the DND initiative for the statistical report, consulting fees from CEMAG, D&A Pharma, Inventiva, and OT4B Pharma. The Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute acted as a service provider for the DND initiative by monitoring the study sites. Dr. Pépin declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A single dose of oral acoziborole resulted in a greater than 95% cure or probable cure rate for human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), also known as sleeping sickness, according to results from a clinical trial testing a one-dose experimental drug.

The drug has “the potential to revolutionize treatment” for the disease, which remains endemic in sub-Saharan Africa, said Antoine Tarral, MD, head of the human African trypanosomiasis clinical program at the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative, based in Geneva, and senior author of the study, in a press release.

he told this news organization. “It’s the first drug we can use without hospitalization. ... All the previous medications needed hospitalization, and therefore we could not treat the population early before they started expressing symptoms.”

The World Health Organization “has been working for decades for such a possibility to implement a new strategy for this disease,” Dr. Tarral said.

Current (2019) WHO guidelines recommend oral fexinidazole as first-line treatment for any stage of the disease. The 10-day course often requires hospitalization and skilled staff. Previous recommendations required disease-staging with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sampling and 7 days of intramuscular pentamidine for early-stage disease or nifurtimox-eflornithine combination therapy (NECT) with hospitalization for late-stage disease.

By contrast, acoziborole, which was codeveloped by the DND initiative and Sanofi, “is administered in a single dose and is effective across every stage of the disease, thereby eliminating the many barriers currently in place for people most vulnerable to the diseases, such as invasive treatments and long travel distances to a hospital or clinic, and opening the door to screen-and-treat approaches at the village level,” Dr. Tarral said in the statement.

“Today, and in the future, we will have less and less support to do this long and costly diagnostic process and treatment in the hospital,” he said in an interview. “This development means we can go for a simple test and a simple treatment, which means we can meet the WHO 2030 goal for ending transmission of this disease.”

Results from the multicenter, prospective, open-label, single-arm, noncomparative, phase 2/3 study were published in The Lancet.

Pragmatic study design

Sleeping sickness is caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (gambiense HAT). It is transmitted by the tsetse fly and mostly fatal when left untreated.

The study enrolled 208 adults and adolescents (167 with late-stage, and 41 with early-stage or intermediate-stage disease) from 10 hospitals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Guinea. All patients were treated with acoziborole 960 mg – an unusual study design.

“Due to the substantial decline in incidence, enrolling patients with gambiense HAT into clinical trials is challenging,” the authors wrote. “Following advice from the European Medicines Agency, this study was designed as an open-label, single-arm trial with no comparator or control group.”

After 18 months of follow-up, treatment success, defined as absence of trypanosomes and less than 20 white blood cells per mcL of CSF, occurred in 159 (95.2%) of the late-stage patients, and 100% of the early- and intermediate-stage patients, “which was similar to the estimated historical results for NECT,” the authors noted.

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 21 (10%) of patients, “but none of these events were considered drug-related,” they added.

The DND initiative and the WHO are currently nearing completion of a much larger, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of acoziborole to “increase the safety database,” Dr. Tarral explained.

“Purists will say that acoziborole has not been evaluated according to current standards, because the study was not a randomized trial, there was no control group, and the number of participants was small,” said Jacques Pépin, MD, from the University of Sherbrooke (Que.), in a linked commentary.

“But these were difficult challenges to overcome, considering the drastic reduction in the number of patients with HAT and dispersion over a vast territory, particularly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. For these reasons, the authors took a pragmatic approach instead,” he wrote.

A potential new tool for eradication of sleeping sickness

“This is really an exciting development, which will be useful in the drive for eradication/interruption of transmission of this disease,” Dr. Pépin told this news organization.

Dr. Pépin treated around 1,000 trypanosomiasis patients during an outbreak in Zaire in the early 1980s. Because the asymptomatic incubation period for the disease can be several months or even years, “the core strategy for controlling the disease is active screening,” he said in an interview.

“You try to convince the whole population of endemic villages to show up on a given day, and then you have a mobile team of nurses who examine everybody, trying to find those with early trypanosomiasis. This includes physical examination for lymph nodes in the neck, but also a blood test whose results are available within minutes,” he said.

“Until now, these persons with a positive serology would undergo additional and labor-intensive examinations of blood to try to find trypanosomes and prove that they have the disease. So far those with a positive serology and negative parasitological assays (‘serological suspects’) were left untreated, because the treatments were toxic and cumbersome, and because a substantial but unknown proportion of these ‘suspects’ just have a false positive of their serological test, without having the disease,” Dr. Pépin said.

“Now with acoziborole, which seems to have little serious toxicity ... and can be given as a single-dose oral med, it might be reasonable to treat the ‘serological suspects,’ ” he said.

“Take it one step further, it might be possible to do the serological test only and treat all individuals with a positive serology without bothering to do parasitological assays. This is what they call ‘test-and-treat’ strategy. It would make sense, provided that we are sure that the drug is very well tolerated.”

Dr. Pépin added that he is “just slightly worried” about three patients described in the paper who had psychiatric adverse events 3 months after treatment. “If that happens to patients who indeed have trypanosomiasis, that’s a reasonable price to pay considering the toxicity of other drugs,” he said. “If that happens to serological suspects, many of whom don’t have any disease, this becomes a preoccupation.”

But Dr. Tarral said, “We have no indication that the drug can provoke psychiatric symptoms. In fact, the psychiatric symptoms did not emerge – they re-emerged after 3 months due to some patients’ refusal to be followed up.”

“We included patients in very advanced stages of the disease, and these symptoms are considered disease sequelae,” Dr. Tarral said. “The majority of patients who have such psychiatric symptoms need follow-up after treatment. If not, they can relapse very early. There were a lot of patients who had such symptoms and the investigators proposed they should be followed by a psychiatrist and some of them refused. And due to that only three of our patients had this relapse, and they were cured after psychiatric support.”

The study was funded through the DND initiative and was supported by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; UK Aid; the Federal Ministry of Education and Research through Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau, Germany; the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation; Médecins Sans Frontières; the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs; the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation; the Stavros Niarchos Foundation; the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation; and the Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria Foundation.

A number of study investigators, including Dr. Tarral, report employment at the DND initiative. Other investigators report fees from the DND initiative for the statistical report, consulting fees from CEMAG, D&A Pharma, Inventiva, and OT4B Pharma. The Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute acted as a service provider for the DND initiative by monitoring the study sites. Dr. Pépin declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What is the genetic influence on the severity of COVID-19?

A striking characteristic of COVID-19 is that the severity of clinical outcomes is remarkably variable. Establishing a prognosis for individuals infected with COVID-19 remains a challenge.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the heterogeneity of individuals who progress toward severe disease or death, along with the fact that individuals directly exposed to the virus do not necessarily become sick, supports the hypothesis that genetic risk or protective factors are at play.

In an interview with this news organization, Mayana Zatz, PhD, head professor of genetics and coordinator of the Human Genome and Stem Cell Study Center at the University of São Paulo, explained: “The first case that caught my eye was the case of my neighbors, a couple. He presented COVID-19 symptoms, but his wife, who took care of him, had absolutely no symptoms. I thought that it was strange, but we received 3,000 emails from people saying, ‘This happened to me, too.’”

Reports in the media about seven pairs of monozygotic (MZ) twins who died from COVID-19 within days of one another in Brazil also stood out, said the researcher.

, as well as their pathology. Dr. Zatz’s team analyzed the case of a 31-year-old Brazilian MZ twin brother pair who presented simultaneously with severe COVID-19 and the need for oxygen support, despite their age and good health conditions. Curiously, they were admitted and intubated on the same day, but neither of the twins knew about the other’s situation; they found out only when they were extubated.

The study was carried out at the USP with the collaboration of the State University of São Paulo. The authors mapped the genetic profile (by sequencing the genome responsible for coding proteins, or whole-exome sequencing) and the immune cell profile to evaluate innate and adaptive immunity.

The MZ twin brothers shared the same two rare genetic mutations, which may be associated with their increased risk of developing severe COVID-19. However, since these variants were not studied at the protein or functional level, their pathogenicity has yet to be determined. The twins also had [human leukocyte antigen (HLA)] alleles associated with severe COVID-19, which are important candidates for the mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity and susceptibility to COVID-19 infection and manifestation.

But one particular oddity stood out to the researchers: One of the brothers required longer hospitalization, and only he reported symptoms of long COVID.

In the authors’ eyes, even though the patients shared genetic mutations potentially associated with the risk of developing severe COVID-19, the differences in clinical progression emphasize that, beyond genetic risk factors, continuous exposure to pathogens over a lifetime and other environmental factors mean that each individual’s immune response is unique, even in twins.

“There is no doubt that genetics contribute to the severity of COVID-19, and environmental factors sometimes give us the opportunity to study the disease, too. Such [is the case with] MZ twins who have genetic similarities, even with changes that take place over a lifetime,” José Eduardo Krieger, MD, PhD, professor of molecular medicine at the University of São Paulo Medical School (FMUSP), told this news organization. “Examining MZ twins is a strategy that may help, but, with n = 2, luck really needs to be on your side to get straight to the problem. You need to combine [these findings] with other studies to solve this conundrum,” said Dr. Krieger, who did not take part in the research.

Large cohorts

Genomic and computer resources allow for the study of large sets of data from thousands of individuals. In each of those sets of data, the signal offered by thousands of markers distributed throughout the genome can be studied. This is the possibility offered by various genomic studies of large cohorts of patients with different clinical manifestations.

“Researchers examine thousands of genetic variants throughout the genome from a large sample of individuals and have the chance, for example, to identify genetic variants that are more prevalent in patients who have presented with severe disease than in those who presented with milder disease,” said Dr. Krieger. “These associations highlight a chromosome region in which one or more genes explain, at least in part, the differences observed.”

Genomewide association studies have identified some genetic variants that indicate severity of COVID-19, with potential impact on the virus entering the cell, the immune response, or the development of cytokine storms.

One of these studies, COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative (COVID-19 HGI), is an international, open-science collaboration for sharing scientific methods and resources with research groups across the world, with the goal of robustly mapping the host genetic determinants of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the severity of the resulting COVID-19 disease. At the start of 2021, the COVID-19 HGI combined genetic data from 49,562 cases and 2 million controls from 46 studies in 19 countries. A total of 853 samples from the BRACOVID study were included in the meta-analysis. The endeavor enabled the identification of 13 genomewide significant loci that are associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection or severe manifestations of COVID-19.

The BRACOVID study, in which Dr. Krieger participates, aims to identify host genetic factors that determine the severity of COVID-19. It is currently the largest project of its kind in Latin America. An article provides the analysis of the first 5,233 participants in the BRACOVID study, who were recruited in São Paulo. Of these participants, 3,533 had been infected with COVID-19 and hospitalized at either the Heart Institute or the Central Institute of the FMUSP General Hospital. The remaining 1,700 made up the control group, which included health care professionals and members of the general population. The controls were recruited through serology assays or PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2.

The researchers discovered a region of chromosome 1 that could play a role in modulating immune response and that could lead to an increase in the likelihood of hospitalization across a wide range of COVID-19 risk factors. This region of chromosome 1 was observed only in Brazilians with a strong European ancestry; however, this finding had not been mentioned in previous studies, suggesting that it could harbor a risk allele specific to the Brazilian population.

The study also confirmed most, but not all, of the regions recorded in the literature, which may be significant in identifying factors determining severity that are specific to a given population.

Including information from the BRACOVID study, other studies have enhanced the knowledge on affected organs. Combined data from 14,000 patients from nine countries evaluated a region of a single chromosome and found that carriers of a certain allele had a higher probability of experiencing various COVID-19 complications, such as severe respiratory failure, venous thromboembolism, and liver damage. The risk was even higher for individuals aged 60 years and over.

Discordant couples

Smaller sample sizes of underrepresented populations also provide relevant data for genomic studies. Dr. Zatz’s team carried out genomic studies on smaller groups, comparing serodiscordant couples (where one was infected and symptomatic while the partner remained asymptomatic and seronegative despite sharing the same bedroom during the infection). Their research found genetic variants related to immune response that were associated with susceptibility to infection and progression to severe COVID-19.

The team also went on to study a group of patients older than 90 years who recovered from COVID-19 with mild symptoms or who remained asymptomatic following a positive test for SARS-CoV-2. They compared these patients with a sample of elderly patients from the same city (São Paulo), sampled before the current pandemic. The researchers identified a genetic variant related to mucin production. “In individuals with mild COVID-19, the degradation of these mucins would be more efficient,” said Dr. Zatz. It is possible for this variant to interfere not only with the production of mucus, but also in its composition, as there is an exchange of amino acids in the protein.

“We continued the study by comparing the extremes, i.e., those in their 90s with mild COVID-19 and younger patients with severe COVID-19, including several who died,” said Dr. Zatz.

More personalized medicine

The specialists agreed that a genetic test to predict COVID-19 severity is still a long way away. The genetic component is too little understood to enable the evaluation of individual risk. It has been possible to identify several important areas but, as Dr. Krieger pointed out, a variant identified in a certain chromosome interval may not be just one gene. There may be various candidate genes, or there may be a regulatory sequence for a distant gene. Furthermore, there are regions with genes that make sense as moderators of COVID-19 severity, because they regulate an inflammatory or immunologic reaction, but evidence is still lacking.

Reaching the molecular mechanism would, in future, allow a medicine to be chosen for a given patient, as already happens with other diseases. It also could enable the discovery of new medicines following as-yet-unexplored lines of research. Dr. Zatz also considers the possibility of genetic therapy.

Even with the knowledge of human genetics, one part of the equation is missing: viral genetics. “Many of the individuals who were resistant to the Delta variant were later affected by Omicron,” she pointed out.

Significance of Brazil

“We have an infinite amount of genomic data worldwide, but the vast majority originates from White Americans of European origin,” said Dr. Krieger. Moreover, genomic associations of COVID-19 severity discovered in the Chinese population were not significant in the European population. Besides underscoring the importance of collaborating with international studies, this situation supports scientists’ interest in carrying out genetic studies within Brazil, he added.

“In the genomic study of the Brazilian population, we found 2 million variants that were not present in the European populations,” said Dr. Zatz.

Dr. Krieger mentioned a technical advantage that Brazil has. “Having been colonized by different ethnic groups and mixed many generations ago, Brazil has a population with a unique genetic structure; the recombinations are different. When preparing the samples, the regions break differently.” This factor could help to separate, in a candidate region, the gene that is significant from those that might not be.

In general, severe COVID-19 would be a complex phenomenon involving several genes and interactions with environmental factors. The Brazilian studies tried to find a factor that was unique to Brazil, but the significance of the differences remained unclear. “We found some signs that were specific to our population,” concluded Dr. Krieger. “But the reason that more people in Brazil died as a result of COVID-19 was not genetic,” he added.

Dr. Zatz and Dr. Krieger reported no conflicts of interest. This article was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A striking characteristic of COVID-19 is that the severity of clinical outcomes is remarkably variable. Establishing a prognosis for individuals infected with COVID-19 remains a challenge.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the heterogeneity of individuals who progress toward severe disease or death, along with the fact that individuals directly exposed to the virus do not necessarily become sick, supports the hypothesis that genetic risk or protective factors are at play.

In an interview with this news organization, Mayana Zatz, PhD, head professor of genetics and coordinator of the Human Genome and Stem Cell Study Center at the University of São Paulo, explained: “The first case that caught my eye was the case of my neighbors, a couple. He presented COVID-19 symptoms, but his wife, who took care of him, had absolutely no symptoms. I thought that it was strange, but we received 3,000 emails from people saying, ‘This happened to me, too.’”

Reports in the media about seven pairs of monozygotic (MZ) twins who died from COVID-19 within days of one another in Brazil also stood out, said the researcher.

, as well as their pathology. Dr. Zatz’s team analyzed the case of a 31-year-old Brazilian MZ twin brother pair who presented simultaneously with severe COVID-19 and the need for oxygen support, despite their age and good health conditions. Curiously, they were admitted and intubated on the same day, but neither of the twins knew about the other’s situation; they found out only when they were extubated.

The study was carried out at the USP with the collaboration of the State University of São Paulo. The authors mapped the genetic profile (by sequencing the genome responsible for coding proteins, or whole-exome sequencing) and the immune cell profile to evaluate innate and adaptive immunity.

The MZ twin brothers shared the same two rare genetic mutations, which may be associated with their increased risk of developing severe COVID-19. However, since these variants were not studied at the protein or functional level, their pathogenicity has yet to be determined. The twins also had [human leukocyte antigen (HLA)] alleles associated with severe COVID-19, which are important candidates for the mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity and susceptibility to COVID-19 infection and manifestation.

But one particular oddity stood out to the researchers: One of the brothers required longer hospitalization, and only he reported symptoms of long COVID.

In the authors’ eyes, even though the patients shared genetic mutations potentially associated with the risk of developing severe COVID-19, the differences in clinical progression emphasize that, beyond genetic risk factors, continuous exposure to pathogens over a lifetime and other environmental factors mean that each individual’s immune response is unique, even in twins.

“There is no doubt that genetics contribute to the severity of COVID-19, and environmental factors sometimes give us the opportunity to study the disease, too. Such [is the case with] MZ twins who have genetic similarities, even with changes that take place over a lifetime,” José Eduardo Krieger, MD, PhD, professor of molecular medicine at the University of São Paulo Medical School (FMUSP), told this news organization. “Examining MZ twins is a strategy that may help, but, with n = 2, luck really needs to be on your side to get straight to the problem. You need to combine [these findings] with other studies to solve this conundrum,” said Dr. Krieger, who did not take part in the research.

Large cohorts

Genomic and computer resources allow for the study of large sets of data from thousands of individuals. In each of those sets of data, the signal offered by thousands of markers distributed throughout the genome can be studied. This is the possibility offered by various genomic studies of large cohorts of patients with different clinical manifestations.

“Researchers examine thousands of genetic variants throughout the genome from a large sample of individuals and have the chance, for example, to identify genetic variants that are more prevalent in patients who have presented with severe disease than in those who presented with milder disease,” said Dr. Krieger. “These associations highlight a chromosome region in which one or more genes explain, at least in part, the differences observed.”

Genomewide association studies have identified some genetic variants that indicate severity of COVID-19, with potential impact on the virus entering the cell, the immune response, or the development of cytokine storms.

One of these studies, COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative (COVID-19 HGI), is an international, open-science collaboration for sharing scientific methods and resources with research groups across the world, with the goal of robustly mapping the host genetic determinants of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the severity of the resulting COVID-19 disease. At the start of 2021, the COVID-19 HGI combined genetic data from 49,562 cases and 2 million controls from 46 studies in 19 countries. A total of 853 samples from the BRACOVID study were included in the meta-analysis. The endeavor enabled the identification of 13 genomewide significant loci that are associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection or severe manifestations of COVID-19.

The BRACOVID study, in which Dr. Krieger participates, aims to identify host genetic factors that determine the severity of COVID-19. It is currently the largest project of its kind in Latin America. An article provides the analysis of the first 5,233 participants in the BRACOVID study, who were recruited in São Paulo. Of these participants, 3,533 had been infected with COVID-19 and hospitalized at either the Heart Institute or the Central Institute of the FMUSP General Hospital. The remaining 1,700 made up the control group, which included health care professionals and members of the general population. The controls were recruited through serology assays or PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2.

The researchers discovered a region of chromosome 1 that could play a role in modulating immune response and that could lead to an increase in the likelihood of hospitalization across a wide range of COVID-19 risk factors. This region of chromosome 1 was observed only in Brazilians with a strong European ancestry; however, this finding had not been mentioned in previous studies, suggesting that it could harbor a risk allele specific to the Brazilian population.

The study also confirmed most, but not all, of the regions recorded in the literature, which may be significant in identifying factors determining severity that are specific to a given population.

Including information from the BRACOVID study, other studies have enhanced the knowledge on affected organs. Combined data from 14,000 patients from nine countries evaluated a region of a single chromosome and found that carriers of a certain allele had a higher probability of experiencing various COVID-19 complications, such as severe respiratory failure, venous thromboembolism, and liver damage. The risk was even higher for individuals aged 60 years and over.

Discordant couples

Smaller sample sizes of underrepresented populations also provide relevant data for genomic studies. Dr. Zatz’s team carried out genomic studies on smaller groups, comparing serodiscordant couples (where one was infected and symptomatic while the partner remained asymptomatic and seronegative despite sharing the same bedroom during the infection). Their research found genetic variants related to immune response that were associated with susceptibility to infection and progression to severe COVID-19.

The team also went on to study a group of patients older than 90 years who recovered from COVID-19 with mild symptoms or who remained asymptomatic following a positive test for SARS-CoV-2. They compared these patients with a sample of elderly patients from the same city (São Paulo), sampled before the current pandemic. The researchers identified a genetic variant related to mucin production. “In individuals with mild COVID-19, the degradation of these mucins would be more efficient,” said Dr. Zatz. It is possible for this variant to interfere not only with the production of mucus, but also in its composition, as there is an exchange of amino acids in the protein.

“We continued the study by comparing the extremes, i.e., those in their 90s with mild COVID-19 and younger patients with severe COVID-19, including several who died,” said Dr. Zatz.

More personalized medicine

The specialists agreed that a genetic test to predict COVID-19 severity is still a long way away. The genetic component is too little understood to enable the evaluation of individual risk. It has been possible to identify several important areas but, as Dr. Krieger pointed out, a variant identified in a certain chromosome interval may not be just one gene. There may be various candidate genes, or there may be a regulatory sequence for a distant gene. Furthermore, there are regions with genes that make sense as moderators of COVID-19 severity, because they regulate an inflammatory or immunologic reaction, but evidence is still lacking.

Reaching the molecular mechanism would, in future, allow a medicine to be chosen for a given patient, as already happens with other diseases. It also could enable the discovery of new medicines following as-yet-unexplored lines of research. Dr. Zatz also considers the possibility of genetic therapy.

Even with the knowledge of human genetics, one part of the equation is missing: viral genetics. “Many of the individuals who were resistant to the Delta variant were later affected by Omicron,” she pointed out.

Significance of Brazil

“We have an infinite amount of genomic data worldwide, but the vast majority originates from White Americans of European origin,” said Dr. Krieger. Moreover, genomic associations of COVID-19 severity discovered in the Chinese population were not significant in the European population. Besides underscoring the importance of collaborating with international studies, this situation supports scientists’ interest in carrying out genetic studies within Brazil, he added.

“In the genomic study of the Brazilian population, we found 2 million variants that were not present in the European populations,” said Dr. Zatz.

Dr. Krieger mentioned a technical advantage that Brazil has. “Having been colonized by different ethnic groups and mixed many generations ago, Brazil has a population with a unique genetic structure; the recombinations are different. When preparing the samples, the regions break differently.” This factor could help to separate, in a candidate region, the gene that is significant from those that might not be.

In general, severe COVID-19 would be a complex phenomenon involving several genes and interactions with environmental factors. The Brazilian studies tried to find a factor that was unique to Brazil, but the significance of the differences remained unclear. “We found some signs that were specific to our population,” concluded Dr. Krieger. “But the reason that more people in Brazil died as a result of COVID-19 was not genetic,” he added.

Dr. Zatz and Dr. Krieger reported no conflicts of interest. This article was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A striking characteristic of COVID-19 is that the severity of clinical outcomes is remarkably variable. Establishing a prognosis for individuals infected with COVID-19 remains a challenge.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the heterogeneity of individuals who progress toward severe disease or death, along with the fact that individuals directly exposed to the virus do not necessarily become sick, supports the hypothesis that genetic risk or protective factors are at play.

In an interview with this news organization, Mayana Zatz, PhD, head professor of genetics and coordinator of the Human Genome and Stem Cell Study Center at the University of São Paulo, explained: “The first case that caught my eye was the case of my neighbors, a couple. He presented COVID-19 symptoms, but his wife, who took care of him, had absolutely no symptoms. I thought that it was strange, but we received 3,000 emails from people saying, ‘This happened to me, too.’”

Reports in the media about seven pairs of monozygotic (MZ) twins who died from COVID-19 within days of one another in Brazil also stood out, said the researcher.

, as well as their pathology. Dr. Zatz’s team analyzed the case of a 31-year-old Brazilian MZ twin brother pair who presented simultaneously with severe COVID-19 and the need for oxygen support, despite their age and good health conditions. Curiously, they were admitted and intubated on the same day, but neither of the twins knew about the other’s situation; they found out only when they were extubated.

The study was carried out at the USP with the collaboration of the State University of São Paulo. The authors mapped the genetic profile (by sequencing the genome responsible for coding proteins, or whole-exome sequencing) and the immune cell profile to evaluate innate and adaptive immunity.

The MZ twin brothers shared the same two rare genetic mutations, which may be associated with their increased risk of developing severe COVID-19. However, since these variants were not studied at the protein or functional level, their pathogenicity has yet to be determined. The twins also had [human leukocyte antigen (HLA)] alleles associated with severe COVID-19, which are important candidates for the mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity and susceptibility to COVID-19 infection and manifestation.

But one particular oddity stood out to the researchers: One of the brothers required longer hospitalization, and only he reported symptoms of long COVID.

In the authors’ eyes, even though the patients shared genetic mutations potentially associated with the risk of developing severe COVID-19, the differences in clinical progression emphasize that, beyond genetic risk factors, continuous exposure to pathogens over a lifetime and other environmental factors mean that each individual’s immune response is unique, even in twins.

“There is no doubt that genetics contribute to the severity of COVID-19, and environmental factors sometimes give us the opportunity to study the disease, too. Such [is the case with] MZ twins who have genetic similarities, even with changes that take place over a lifetime,” José Eduardo Krieger, MD, PhD, professor of molecular medicine at the University of São Paulo Medical School (FMUSP), told this news organization. “Examining MZ twins is a strategy that may help, but, with n = 2, luck really needs to be on your side to get straight to the problem. You need to combine [these findings] with other studies to solve this conundrum,” said Dr. Krieger, who did not take part in the research.

Large cohorts

Genomic and computer resources allow for the study of large sets of data from thousands of individuals. In each of those sets of data, the signal offered by thousands of markers distributed throughout the genome can be studied. This is the possibility offered by various genomic studies of large cohorts of patients with different clinical manifestations.

“Researchers examine thousands of genetic variants throughout the genome from a large sample of individuals and have the chance, for example, to identify genetic variants that are more prevalent in patients who have presented with severe disease than in those who presented with milder disease,” said Dr. Krieger. “These associations highlight a chromosome region in which one or more genes explain, at least in part, the differences observed.”

Genomewide association studies have identified some genetic variants that indicate severity of COVID-19, with potential impact on the virus entering the cell, the immune response, or the development of cytokine storms.

One of these studies, COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative (COVID-19 HGI), is an international, open-science collaboration for sharing scientific methods and resources with research groups across the world, with the goal of robustly mapping the host genetic determinants of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the severity of the resulting COVID-19 disease. At the start of 2021, the COVID-19 HGI combined genetic data from 49,562 cases and 2 million controls from 46 studies in 19 countries. A total of 853 samples from the BRACOVID study were included in the meta-analysis. The endeavor enabled the identification of 13 genomewide significant loci that are associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection or severe manifestations of COVID-19.

The BRACOVID study, in which Dr. Krieger participates, aims to identify host genetic factors that determine the severity of COVID-19. It is currently the largest project of its kind in Latin America. An article provides the analysis of the first 5,233 participants in the BRACOVID study, who were recruited in São Paulo. Of these participants, 3,533 had been infected with COVID-19 and hospitalized at either the Heart Institute or the Central Institute of the FMUSP General Hospital. The remaining 1,700 made up the control group, which included health care professionals and members of the general population. The controls were recruited through serology assays or PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2.

The researchers discovered a region of chromosome 1 that could play a role in modulating immune response and that could lead to an increase in the likelihood of hospitalization across a wide range of COVID-19 risk factors. This region of chromosome 1 was observed only in Brazilians with a strong European ancestry; however, this finding had not been mentioned in previous studies, suggesting that it could harbor a risk allele specific to the Brazilian population.

The study also confirmed most, but not all, of the regions recorded in the literature, which may be significant in identifying factors determining severity that are specific to a given population.

Including information from the BRACOVID study, other studies have enhanced the knowledge on affected organs. Combined data from 14,000 patients from nine countries evaluated a region of a single chromosome and found that carriers of a certain allele had a higher probability of experiencing various COVID-19 complications, such as severe respiratory failure, venous thromboembolism, and liver damage. The risk was even higher for individuals aged 60 years and over.

Discordant couples

Smaller sample sizes of underrepresented populations also provide relevant data for genomic studies. Dr. Zatz’s team carried out genomic studies on smaller groups, comparing serodiscordant couples (where one was infected and symptomatic while the partner remained asymptomatic and seronegative despite sharing the same bedroom during the infection). Their research found genetic variants related to immune response that were associated with susceptibility to infection and progression to severe COVID-19.

The team also went on to study a group of patients older than 90 years who recovered from COVID-19 with mild symptoms or who remained asymptomatic following a positive test for SARS-CoV-2. They compared these patients with a sample of elderly patients from the same city (São Paulo), sampled before the current pandemic. The researchers identified a genetic variant related to mucin production. “In individuals with mild COVID-19, the degradation of these mucins would be more efficient,” said Dr. Zatz. It is possible for this variant to interfere not only with the production of mucus, but also in its composition, as there is an exchange of amino acids in the protein.

“We continued the study by comparing the extremes, i.e., those in their 90s with mild COVID-19 and younger patients with severe COVID-19, including several who died,” said Dr. Zatz.

More personalized medicine

The specialists agreed that a genetic test to predict COVID-19 severity is still a long way away. The genetic component is too little understood to enable the evaluation of individual risk. It has been possible to identify several important areas but, as Dr. Krieger pointed out, a variant identified in a certain chromosome interval may not be just one gene. There may be various candidate genes, or there may be a regulatory sequence for a distant gene. Furthermore, there are regions with genes that make sense as moderators of COVID-19 severity, because they regulate an inflammatory or immunologic reaction, but evidence is still lacking.

Reaching the molecular mechanism would, in future, allow a medicine to be chosen for a given patient, as already happens with other diseases. It also could enable the discovery of new medicines following as-yet-unexplored lines of research. Dr. Zatz also considers the possibility of genetic therapy.

Even with the knowledge of human genetics, one part of the equation is missing: viral genetics. “Many of the individuals who were resistant to the Delta variant were later affected by Omicron,” she pointed out.

Significance of Brazil

“We have an infinite amount of genomic data worldwide, but the vast majority originates from White Americans of European origin,” said Dr. Krieger. Moreover, genomic associations of COVID-19 severity discovered in the Chinese population were not significant in the European population. Besides underscoring the importance of collaborating with international studies, this situation supports scientists’ interest in carrying out genetic studies within Brazil, he added.

“In the genomic study of the Brazilian population, we found 2 million variants that were not present in the European populations,” said Dr. Zatz.

Dr. Krieger mentioned a technical advantage that Brazil has. “Having been colonized by different ethnic groups and mixed many generations ago, Brazil has a population with a unique genetic structure; the recombinations are different. When preparing the samples, the regions break differently.” This factor could help to separate, in a candidate region, the gene that is significant from those that might not be.

In general, severe COVID-19 would be a complex phenomenon involving several genes and interactions with environmental factors. The Brazilian studies tried to find a factor that was unique to Brazil, but the significance of the differences remained unclear. “We found some signs that were specific to our population,” concluded Dr. Krieger. “But the reason that more people in Brazil died as a result of COVID-19 was not genetic,” he added.

Dr. Zatz and Dr. Krieger reported no conflicts of interest. This article was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The surprising failure of vitamin D in deficient kids

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

My basic gripe is that you’ve got all these observational studies linking lower levels of vitamin D to everything from dementia to falls to cancer to COVID infection, and then you do a big randomized trial of supplementation and don’t see an effect.

And the explanation is that vitamin D is not necessarily the thing causing these bad outcomes; it’s a bystander – a canary in the coal mine. Your vitamin D level is a marker of your lifestyle; it’s higher in people who eat healthier foods, who exercise, and who spend more time out in the sun.

And yet ... if you were to ask me whether supplementing vitamin D in children with vitamin D deficiency would help them grow better and be healthier, I probably would have been on board for the idea.

And, it looks like, I would have been wrong.

Yes, it’s another negative randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to add to the seemingly ever-growing body of literature suggesting that your money is better spent on a day at the park rather than buying D3 from your local GNC.

We are talking about this study, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Briefly, 8,851 children from around Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, were randomized to receive 14,000 international units of vitamin D3 or placebo every week for 3 years.

Before we get into the results of the study, I need to point out that this part of Mongolia has a high rate of vitamin D deficiency. Beyond that, a prior observational study by these authors had shown that lower vitamin D levels were linked to the risk of acquiring latent tuberculosis infection in this area. Other studies have linked vitamin D deficiency with poorer growth metrics in children. Given the global scourge that is TB (around 2 million deaths a year) and childhood malnutrition (around 10% of children around the world), vitamin D supplementation is incredibly attractive as a public health intervention. It is relatively low on side effects and, importantly, it is cheap – and thus scalable.

Back to the study. These kids had pretty poor vitamin D levels at baseline; 95% of them were deficient, based on the accepted standard of levels less than 20 ng/mL. Over 30% were severely deficient, with levels less than 10 ng/mL.

The initial purpose of this study was to see if supplementation would prevent TB, but that analysis, which was published a few months ago, was negative. Vitamin D levels went up dramatically in the intervention group – they were taking their pills – but there was no difference in the rate of latent TB infection, active TB, other respiratory infections, or even serum interferon gamma levels.

Nothing.

But to be fair, the TB seroconversion rate was lower than expected, potentially leading to an underpowered study.

Which brings us to the just-published analysis which moves away from infectious disease to something where vitamin D should have some stronger footing: growth.

Would the kids who were randomized to vitamin D, those same kids who got their vitamin D levels into the normal range over 3 years of supplementation, grow more or grow better than the kids who didn’t?

And, unfortunately, the answer is still no.

At the end of follow-up, height z scores were not different between the groups. BMI z scores were not different between the groups. Pubertal development was not different between the groups. This was true not only overall, but across various subgroups, including analyses of those kids who had vitamin D levels less than 10 ng/mL to start with.

So, what’s going on? There are two very broad possibilities we can endorse. First, there’s the idea that vitamin D supplementation simply doesn’t do much for health. This is supported, now, by a long string of large clinical trials that show no effect across a variety of disease states and predisease states. In other words, the observational data linking low vitamin D to bad outcomes is correlation, not causation.

Or we can take the tack of some vitamin D apologists and decide that this trial just got it wrong. Perhaps the dose wasn’t given correctly, or 3 years isn’t long enough to see a real difference, or the growth metrics were wrong, or vitamin D needs to be given alongside something else to really work and so on. This is fine; no study is perfect and there is always something to criticize, believe me. But we need to be careful not to fall into the baby-and-bathwater fallacy. Just because we think a study could have done something better, or differently, doesn’t mean we can ignore all the results. And as each new randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation comes out, it’s getting harder and harder to believe that these trialists keep getting their methods wrong. Maybe they are just testing something that doesn’t work.

What to do? Well, it should be obvious. If low vitamin D levels are linked to TB rates and poor growth but supplementation doesn’t fix the problem, then we have to fix what is upstream of the problem. We need to boost vitamin D levels not through supplements, but through nutrition, exercise, activity, and getting outside. That’s a randomized trial you can sign me up for any day.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this video transcript first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

My basic gripe is that you’ve got all these observational studies linking lower levels of vitamin D to everything from dementia to falls to cancer to COVID infection, and then you do a big randomized trial of supplementation and don’t see an effect.

And the explanation is that vitamin D is not necessarily the thing causing these bad outcomes; it’s a bystander – a canary in the coal mine. Your vitamin D level is a marker of your lifestyle; it’s higher in people who eat healthier foods, who exercise, and who spend more time out in the sun.

And yet ... if you were to ask me whether supplementing vitamin D in children with vitamin D deficiency would help them grow better and be healthier, I probably would have been on board for the idea.

And, it looks like, I would have been wrong.

Yes, it’s another negative randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to add to the seemingly ever-growing body of literature suggesting that your money is better spent on a day at the park rather than buying D3 from your local GNC.

We are talking about this study, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Briefly, 8,851 children from around Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, were randomized to receive 14,000 international units of vitamin D3 or placebo every week for 3 years.

Before we get into the results of the study, I need to point out that this part of Mongolia has a high rate of vitamin D deficiency. Beyond that, a prior observational study by these authors had shown that lower vitamin D levels were linked to the risk of acquiring latent tuberculosis infection in this area. Other studies have linked vitamin D deficiency with poorer growth metrics in children. Given the global scourge that is TB (around 2 million deaths a year) and childhood malnutrition (around 10% of children around the world), vitamin D supplementation is incredibly attractive as a public health intervention. It is relatively low on side effects and, importantly, it is cheap – and thus scalable.

Back to the study. These kids had pretty poor vitamin D levels at baseline; 95% of them were deficient, based on the accepted standard of levels less than 20 ng/mL. Over 30% were severely deficient, with levels less than 10 ng/mL.

The initial purpose of this study was to see if supplementation would prevent TB, but that analysis, which was published a few months ago, was negative. Vitamin D levels went up dramatically in the intervention group – they were taking their pills – but there was no difference in the rate of latent TB infection, active TB, other respiratory infections, or even serum interferon gamma levels.

Nothing.

But to be fair, the TB seroconversion rate was lower than expected, potentially leading to an underpowered study.

Which brings us to the just-published analysis which moves away from infectious disease to something where vitamin D should have some stronger footing: growth.

Would the kids who were randomized to vitamin D, those same kids who got their vitamin D levels into the normal range over 3 years of supplementation, grow more or grow better than the kids who didn’t?

And, unfortunately, the answer is still no.

At the end of follow-up, height z scores were not different between the groups. BMI z scores were not different between the groups. Pubertal development was not different between the groups. This was true not only overall, but across various subgroups, including analyses of those kids who had vitamin D levels less than 10 ng/mL to start with.

So, what’s going on? There are two very broad possibilities we can endorse. First, there’s the idea that vitamin D supplementation simply doesn’t do much for health. This is supported, now, by a long string of large clinical trials that show no effect across a variety of disease states and predisease states. In other words, the observational data linking low vitamin D to bad outcomes is correlation, not causation.

Or we can take the tack of some vitamin D apologists and decide that this trial just got it wrong. Perhaps the dose wasn’t given correctly, or 3 years isn’t long enough to see a real difference, or the growth metrics were wrong, or vitamin D needs to be given alongside something else to really work and so on. This is fine; no study is perfect and there is always something to criticize, believe me. But we need to be careful not to fall into the baby-and-bathwater fallacy. Just because we think a study could have done something better, or differently, doesn’t mean we can ignore all the results. And as each new randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation comes out, it’s getting harder and harder to believe that these trialists keep getting their methods wrong. Maybe they are just testing something that doesn’t work.

What to do? Well, it should be obvious. If low vitamin D levels are linked to TB rates and poor growth but supplementation doesn’t fix the problem, then we have to fix what is upstream of the problem. We need to boost vitamin D levels not through supplements, but through nutrition, exercise, activity, and getting outside. That’s a randomized trial you can sign me up for any day.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this video transcript first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

My basic gripe is that you’ve got all these observational studies linking lower levels of vitamin D to everything from dementia to falls to cancer to COVID infection, and then you do a big randomized trial of supplementation and don’t see an effect.

And the explanation is that vitamin D is not necessarily the thing causing these bad outcomes; it’s a bystander – a canary in the coal mine. Your vitamin D level is a marker of your lifestyle; it’s higher in people who eat healthier foods, who exercise, and who spend more time out in the sun.

And yet ... if you were to ask me whether supplementing vitamin D in children with vitamin D deficiency would help them grow better and be healthier, I probably would have been on board for the idea.

And, it looks like, I would have been wrong.

Yes, it’s another negative randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to add to the seemingly ever-growing body of literature suggesting that your money is better spent on a day at the park rather than buying D3 from your local GNC.

We are talking about this study, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Briefly, 8,851 children from around Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, were randomized to receive 14,000 international units of vitamin D3 or placebo every week for 3 years.

Before we get into the results of the study, I need to point out that this part of Mongolia has a high rate of vitamin D deficiency. Beyond that, a prior observational study by these authors had shown that lower vitamin D levels were linked to the risk of acquiring latent tuberculosis infection in this area. Other studies have linked vitamin D deficiency with poorer growth metrics in children. Given the global scourge that is TB (around 2 million deaths a year) and childhood malnutrition (around 10% of children around the world), vitamin D supplementation is incredibly attractive as a public health intervention. It is relatively low on side effects and, importantly, it is cheap – and thus scalable.

Back to the study. These kids had pretty poor vitamin D levels at baseline; 95% of them were deficient, based on the accepted standard of levels less than 20 ng/mL. Over 30% were severely deficient, with levels less than 10 ng/mL.

The initial purpose of this study was to see if supplementation would prevent TB, but that analysis, which was published a few months ago, was negative. Vitamin D levels went up dramatically in the intervention group – they were taking their pills – but there was no difference in the rate of latent TB infection, active TB, other respiratory infections, or even serum interferon gamma levels.

Nothing.

But to be fair, the TB seroconversion rate was lower than expected, potentially leading to an underpowered study.

Which brings us to the just-published analysis which moves away from infectious disease to something where vitamin D should have some stronger footing: growth.

Would the kids who were randomized to vitamin D, those same kids who got their vitamin D levels into the normal range over 3 years of supplementation, grow more or grow better than the kids who didn’t?

And, unfortunately, the answer is still no.

At the end of follow-up, height z scores were not different between the groups. BMI z scores were not different between the groups. Pubertal development was not different between the groups. This was true not only overall, but across various subgroups, including analyses of those kids who had vitamin D levels less than 10 ng/mL to start with.

So, what’s going on? There are two very broad possibilities we can endorse. First, there’s the idea that vitamin D supplementation simply doesn’t do much for health. This is supported, now, by a long string of large clinical trials that show no effect across a variety of disease states and predisease states. In other words, the observational data linking low vitamin D to bad outcomes is correlation, not causation.

Or we can take the tack of some vitamin D apologists and decide that this trial just got it wrong. Perhaps the dose wasn’t given correctly, or 3 years isn’t long enough to see a real difference, or the growth metrics were wrong, or vitamin D needs to be given alongside something else to really work and so on. This is fine; no study is perfect and there is always something to criticize, believe me. But we need to be careful not to fall into the baby-and-bathwater fallacy. Just because we think a study could have done something better, or differently, doesn’t mean we can ignore all the results. And as each new randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation comes out, it’s getting harder and harder to believe that these trialists keep getting their methods wrong. Maybe they are just testing something that doesn’t work.

What to do? Well, it should be obvious. If low vitamin D levels are linked to TB rates and poor growth but supplementation doesn’t fix the problem, then we have to fix what is upstream of the problem. We need to boost vitamin D levels not through supplements, but through nutrition, exercise, activity, and getting outside. That’s a randomized trial you can sign me up for any day.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this video transcript first appeared on Medscape.com.

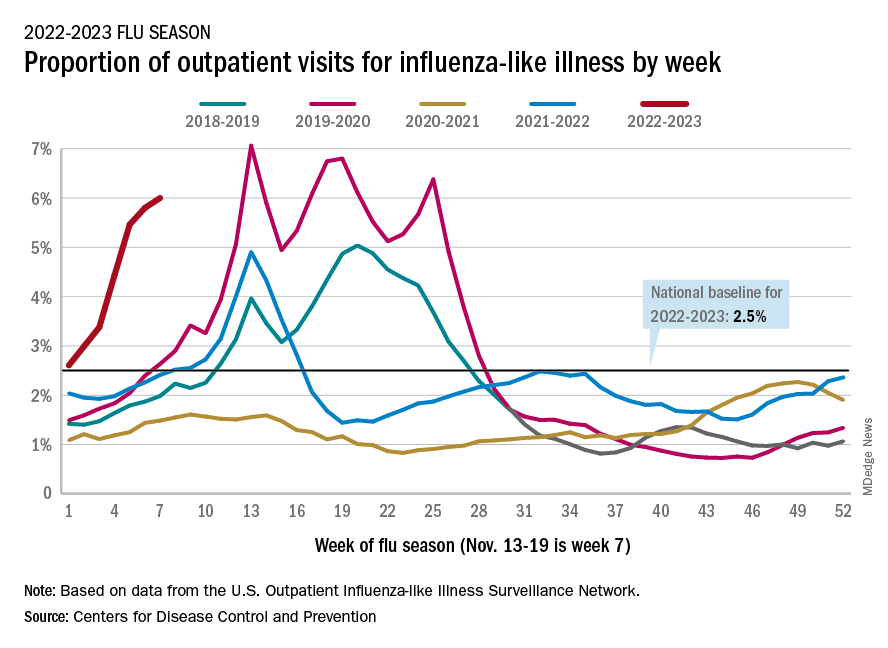

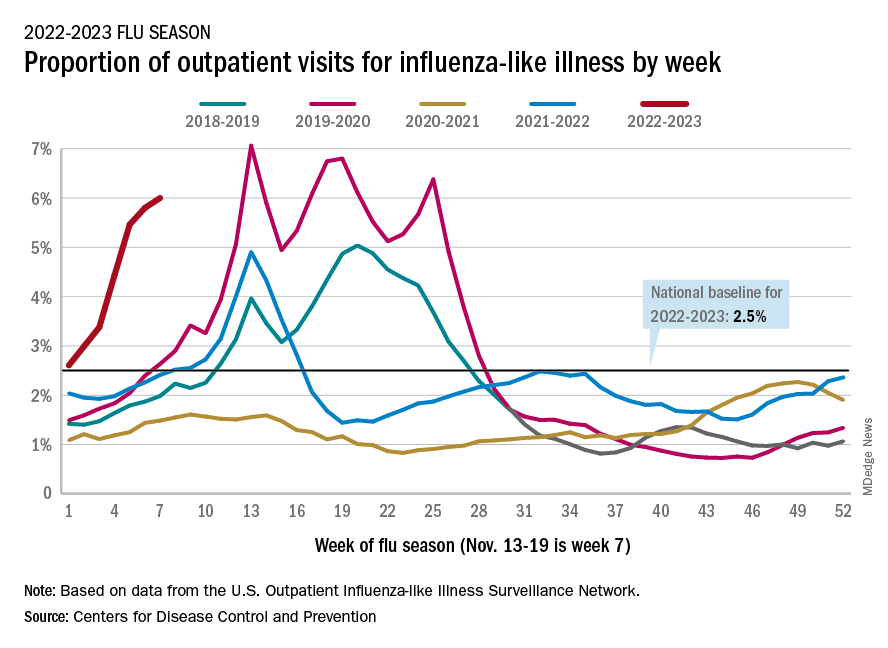

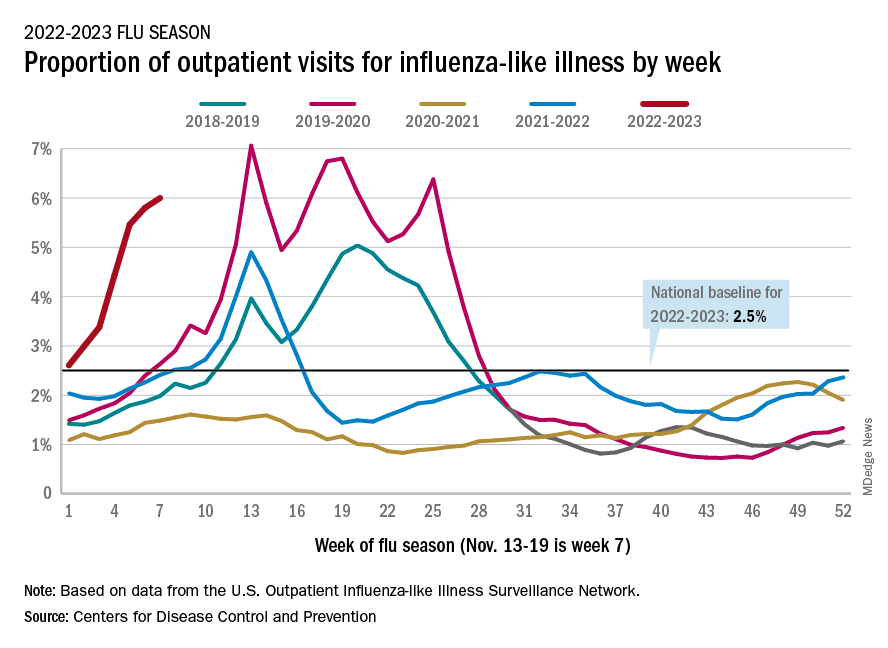

U.S. flu activity already at mid-season levels

according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 6% of all outpatient visits were because of flu or flu-like illness for the week of Nov. 13-19, up from 5.8% the previous week, the CDC’s Influenza Division said in its weekly FluView report.

Those figures are the highest recorded in November since 2009, but the peak of the 2009-10 flu season occurred even earlier – the week of Oct. 18-24 – and the rate of flu-like illness had already dropped to just over 4.0% by Nov. 15-21 that year and continued to drop thereafter.

Although COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are included in the data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the agency did note that “seasonal influenza activity is elevated across the country” and estimated that “there have been at least 6.2 million illnesses, 53,000 hospitalizations, and 2,900 deaths from flu” during the 2022-23 season.

Total flu deaths include 11 reported in children as of Nov. 19, and children ages 0-4 had a higher proportion of visits for flu like-illness than other age groups.

The agency also said the cumulative hospitalization rate of 11.3 per 100,000 population “is higher than the rate observed in [the corresponding week of] every previous season since 2010-2011.” Adults 65 years and older have the highest cumulative rate, 25.9 per 100,000, for this year, compared with 20.7 for children 0-4; 11.1 for adults 50-64; 10.3 for children 5-17; and 5.6 for adults 18-49 years old, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 6% of all outpatient visits were because of flu or flu-like illness for the week of Nov. 13-19, up from 5.8% the previous week, the CDC’s Influenza Division said in its weekly FluView report.

Those figures are the highest recorded in November since 2009, but the peak of the 2009-10 flu season occurred even earlier – the week of Oct. 18-24 – and the rate of flu-like illness had already dropped to just over 4.0% by Nov. 15-21 that year and continued to drop thereafter.