User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

The COVID-19 push to evolve

Has anyone else noticed how slow it has been on your pediatric floors? Well, you are not alone.

The COVID pandemic has had a significant impact on health care volumes, with pediatric volumes decreasing across the nation. A Children’s Hospital Association CEO survey, currently unpublished, noted a 10%-20% decline in inpatient admissions and a 30%-50% decline in pediatric ED visits this past year. Even our usual respiratory surge has been disrupted. The rate of influenza tracked by the CDC is around 1%, compared with the usual seasonal flu baseline national rate of 2.6%. These COVID-related declines have occurred amidst the backdrop of already-decreasing inpatient admissions because of the great work of the pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) community in reducing unnecessary admissions and lengths of stay.

For many hospitals, several factors related to the pandemic have raised significant financial concerns. According to Becker Hospital Review, as of August 2020 over 500 hospitals had furloughed workers. While 26 of those hospitals had brought back workers by December 2020, many did not. Similar financial concerns were noted in a Kaufmann Hall report from January 2021, which showed a median drop of 55% in operating margins. The CARES Act helped reduce some of the detrimental impact on operating margins, but it did not diminish the added burden of personal protective equipment expenses, longer length of stay for COVID patients, and a reimbursement shift to more government payors and uninsured caused by pandemic-forced job losses.

COVID’s impact specific to pediatric hospital medicine has been substantial. A recent unpublished survey by the PHM Economics Research Collaborative (PERC) demonstrated how COVID has affected pediatric hospital medicine programs. Forty-five unique PHM programs from over 21 states responded, with 98% reporting a decrease in pediatric inpatient admissions as well as ED visits. About 11% reported temporary unit closures, while 51% of all programs reported staffing restrictions ranging from hiring freezes to downsizing the number of hospitalists in the group. Salaries decreased in 26% of reporting programs, and 20%-56% described reduced benefits, ranging from less CME/vacation time and stipends to retirement benefits. The three most frequent benefit losses included annual salary increases, educational stipends, and bonuses.

Community hospitals felt the palpable, financial strain of decreasing pediatric admissions well before the pandemic. Hospitals like MedStar Franklin Square Hospital in Baltimore and Harrington Hospital in Southbridge, Mass., had decided to close their pediatrics units before COVID hit. In a 2014 unpublished survey of 349 community PHM (CPHM) programs, 57% of respondents felt that finances and justification for a pediatric program were primary concerns.

Responding to financial stressors is not a novel challenge for CPHM programs. To keep these vital pediatric programs in place despite lower inpatient volumes, those of us in CPHM have learned many lessons over the years on how to adapt. Such adaptations have included diversification in procedures and multifloor coverage in the hospital. Voiding cystourethrogram catheterizations and circumcisions are now more commonly performed by CPHM providers, who may also cover multiple areas of the hospital, including the ED, NICU, and well-newborn nursery. Comanagement of subspecialty or surgical patients is yet another example of such diversification.

Furthermore, the PERC survey showed that some PHM programs temporarily covered pediatric ICUs and step-down units and began doing ED and urgent care coverage as primary providers Most programs reported no change in newborn visits while 16% reported an increase in newborn volume and 14% reported a decrease in newborn volume. My own health system was one of the groups that had an increase in newborn volume. This was caused by community pediatricians who had stopped coming in to see their own newborns. This coverage adjustment has yet to return to baseline and will likely become permanent.

There was a 11% increase from prepandemic baselines (from 9% to 20%) in programs doing telemedicine. Most respondents stated that they will continue to offer telemedicine with an additional 25% of programs considering starting. There was also a slight increase during the pandemic of coverage of mental health units (from 11% to 13%), which may have led 11% of respondents to consider the addition of this service. The survey also noted that about 28% of PHM programs performed circumcisions, frenectomies, and sedation prepandemic, and 14%-18% are considering adding these services.

Overall, the financial stressors are improving, but our need to adapt in PHM is more pressing than ever. The pandemic has given us the push for evolution and some opportunities that did not exist before. One is the use of telemedicine to expand our subspecialty support to community hospitals, as well as to children’s hospitals in areas where subspecialists are in short supply. These telemedicine consults are being reimbursed for the first time, which allows more access to these services.

With the pandemic, many hospitals are moving to single room occupancy models. Construction to add more beds is costly, and unnecessary if we can utilize community hospitals to keep appropriate patients in their home communities. The opportunity to partner with community hospital programs to provide telemedicine support should not be overlooked. This is also an opportunity for academic referral centers to have more open beds for critical care and highly specialized patients.

Another opportunity is to expand scope by changing age limits, as 18% of respondents to the PERC survey reported that they had started to care for adults since the pandemic. The Pediatric Overflow Planning Contingency Response Network (POPCoRN) has been a valuable resource for education on caring for adults, guidance on which patient populations are appropriate, and the resources needed to do this. While caring for older adults, even in their 90s, was a pandemic-related phenomenon, there is an opportunity to see if the age limit we care for should be raised to 21, or even 25, as some CPHM programs had been doing prepandemic.

Along with the expansion of age limits, there are many other areas of opportunity highlighted within the PERC survey. These include expanding coverage within pediatric ICUs, EDs, and urgent care areas, along with coverage of well newborns that were previously covered by community pediatricians. Also, the increase of mental health admissions is another area where PHM programs might expand their services.

While I hope the financial stressors improve, hope is not a plan and therefore we need to think and prepare for what the post-COVID future may look like. Some have predicted a rebound pediatric respiratory surge next year as the masks come off and children return to in-person learning and daycare. This may be true, but we would be foolish not to use lessons from the pandemic as well as the past to consider options in our toolkit to become more financially stable. POPCoRN, as well as the American Academy of Pediatrics’ listserv and subcommittees, have been a source of collaboration and shared knowledge during a time when we have needed to quickly respond to ever-changing information. These networks and information sharing should be leveraged once the dust settles for us to prepare for future challenges.

New innovations may arise as we look at how we address the growing need for mental health services and incorporate new procedures, like point of care ultrasound. As Charles Darwin said: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.” It is time for us to evolve.

Dr. Dias is a clinical associate professor of pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in the division of pediatric hospital medicine. She has practiced community pediatric hospital medicine for over 21 years in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut. She is the chair of the Education Working Group for the AAP’s section on hospital medicine’s subcommittee on community hospitalists as well as the cochair of the Community Hospital Operations Group of the POPCoRN network.

Has anyone else noticed how slow it has been on your pediatric floors? Well, you are not alone.

The COVID pandemic has had a significant impact on health care volumes, with pediatric volumes decreasing across the nation. A Children’s Hospital Association CEO survey, currently unpublished, noted a 10%-20% decline in inpatient admissions and a 30%-50% decline in pediatric ED visits this past year. Even our usual respiratory surge has been disrupted. The rate of influenza tracked by the CDC is around 1%, compared with the usual seasonal flu baseline national rate of 2.6%. These COVID-related declines have occurred amidst the backdrop of already-decreasing inpatient admissions because of the great work of the pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) community in reducing unnecessary admissions and lengths of stay.

For many hospitals, several factors related to the pandemic have raised significant financial concerns. According to Becker Hospital Review, as of August 2020 over 500 hospitals had furloughed workers. While 26 of those hospitals had brought back workers by December 2020, many did not. Similar financial concerns were noted in a Kaufmann Hall report from January 2021, which showed a median drop of 55% in operating margins. The CARES Act helped reduce some of the detrimental impact on operating margins, but it did not diminish the added burden of personal protective equipment expenses, longer length of stay for COVID patients, and a reimbursement shift to more government payors and uninsured caused by pandemic-forced job losses.

COVID’s impact specific to pediatric hospital medicine has been substantial. A recent unpublished survey by the PHM Economics Research Collaborative (PERC) demonstrated how COVID has affected pediatric hospital medicine programs. Forty-five unique PHM programs from over 21 states responded, with 98% reporting a decrease in pediatric inpatient admissions as well as ED visits. About 11% reported temporary unit closures, while 51% of all programs reported staffing restrictions ranging from hiring freezes to downsizing the number of hospitalists in the group. Salaries decreased in 26% of reporting programs, and 20%-56% described reduced benefits, ranging from less CME/vacation time and stipends to retirement benefits. The three most frequent benefit losses included annual salary increases, educational stipends, and bonuses.

Community hospitals felt the palpable, financial strain of decreasing pediatric admissions well before the pandemic. Hospitals like MedStar Franklin Square Hospital in Baltimore and Harrington Hospital in Southbridge, Mass., had decided to close their pediatrics units before COVID hit. In a 2014 unpublished survey of 349 community PHM (CPHM) programs, 57% of respondents felt that finances and justification for a pediatric program were primary concerns.

Responding to financial stressors is not a novel challenge for CPHM programs. To keep these vital pediatric programs in place despite lower inpatient volumes, those of us in CPHM have learned many lessons over the years on how to adapt. Such adaptations have included diversification in procedures and multifloor coverage in the hospital. Voiding cystourethrogram catheterizations and circumcisions are now more commonly performed by CPHM providers, who may also cover multiple areas of the hospital, including the ED, NICU, and well-newborn nursery. Comanagement of subspecialty or surgical patients is yet another example of such diversification.

Furthermore, the PERC survey showed that some PHM programs temporarily covered pediatric ICUs and step-down units and began doing ED and urgent care coverage as primary providers Most programs reported no change in newborn visits while 16% reported an increase in newborn volume and 14% reported a decrease in newborn volume. My own health system was one of the groups that had an increase in newborn volume. This was caused by community pediatricians who had stopped coming in to see their own newborns. This coverage adjustment has yet to return to baseline and will likely become permanent.

There was a 11% increase from prepandemic baselines (from 9% to 20%) in programs doing telemedicine. Most respondents stated that they will continue to offer telemedicine with an additional 25% of programs considering starting. There was also a slight increase during the pandemic of coverage of mental health units (from 11% to 13%), which may have led 11% of respondents to consider the addition of this service. The survey also noted that about 28% of PHM programs performed circumcisions, frenectomies, and sedation prepandemic, and 14%-18% are considering adding these services.

Overall, the financial stressors are improving, but our need to adapt in PHM is more pressing than ever. The pandemic has given us the push for evolution and some opportunities that did not exist before. One is the use of telemedicine to expand our subspecialty support to community hospitals, as well as to children’s hospitals in areas where subspecialists are in short supply. These telemedicine consults are being reimbursed for the first time, which allows more access to these services.

With the pandemic, many hospitals are moving to single room occupancy models. Construction to add more beds is costly, and unnecessary if we can utilize community hospitals to keep appropriate patients in their home communities. The opportunity to partner with community hospital programs to provide telemedicine support should not be overlooked. This is also an opportunity for academic referral centers to have more open beds for critical care and highly specialized patients.

Another opportunity is to expand scope by changing age limits, as 18% of respondents to the PERC survey reported that they had started to care for adults since the pandemic. The Pediatric Overflow Planning Contingency Response Network (POPCoRN) has been a valuable resource for education on caring for adults, guidance on which patient populations are appropriate, and the resources needed to do this. While caring for older adults, even in their 90s, was a pandemic-related phenomenon, there is an opportunity to see if the age limit we care for should be raised to 21, or even 25, as some CPHM programs had been doing prepandemic.

Along with the expansion of age limits, there are many other areas of opportunity highlighted within the PERC survey. These include expanding coverage within pediatric ICUs, EDs, and urgent care areas, along with coverage of well newborns that were previously covered by community pediatricians. Also, the increase of mental health admissions is another area where PHM programs might expand their services.

While I hope the financial stressors improve, hope is not a plan and therefore we need to think and prepare for what the post-COVID future may look like. Some have predicted a rebound pediatric respiratory surge next year as the masks come off and children return to in-person learning and daycare. This may be true, but we would be foolish not to use lessons from the pandemic as well as the past to consider options in our toolkit to become more financially stable. POPCoRN, as well as the American Academy of Pediatrics’ listserv and subcommittees, have been a source of collaboration and shared knowledge during a time when we have needed to quickly respond to ever-changing information. These networks and information sharing should be leveraged once the dust settles for us to prepare for future challenges.

New innovations may arise as we look at how we address the growing need for mental health services and incorporate new procedures, like point of care ultrasound. As Charles Darwin said: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.” It is time for us to evolve.

Dr. Dias is a clinical associate professor of pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in the division of pediatric hospital medicine. She has practiced community pediatric hospital medicine for over 21 years in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut. She is the chair of the Education Working Group for the AAP’s section on hospital medicine’s subcommittee on community hospitalists as well as the cochair of the Community Hospital Operations Group of the POPCoRN network.

Has anyone else noticed how slow it has been on your pediatric floors? Well, you are not alone.

The COVID pandemic has had a significant impact on health care volumes, with pediatric volumes decreasing across the nation. A Children’s Hospital Association CEO survey, currently unpublished, noted a 10%-20% decline in inpatient admissions and a 30%-50% decline in pediatric ED visits this past year. Even our usual respiratory surge has been disrupted. The rate of influenza tracked by the CDC is around 1%, compared with the usual seasonal flu baseline national rate of 2.6%. These COVID-related declines have occurred amidst the backdrop of already-decreasing inpatient admissions because of the great work of the pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) community in reducing unnecessary admissions and lengths of stay.

For many hospitals, several factors related to the pandemic have raised significant financial concerns. According to Becker Hospital Review, as of August 2020 over 500 hospitals had furloughed workers. While 26 of those hospitals had brought back workers by December 2020, many did not. Similar financial concerns were noted in a Kaufmann Hall report from January 2021, which showed a median drop of 55% in operating margins. The CARES Act helped reduce some of the detrimental impact on operating margins, but it did not diminish the added burden of personal protective equipment expenses, longer length of stay for COVID patients, and a reimbursement shift to more government payors and uninsured caused by pandemic-forced job losses.

COVID’s impact specific to pediatric hospital medicine has been substantial. A recent unpublished survey by the PHM Economics Research Collaborative (PERC) demonstrated how COVID has affected pediatric hospital medicine programs. Forty-five unique PHM programs from over 21 states responded, with 98% reporting a decrease in pediatric inpatient admissions as well as ED visits. About 11% reported temporary unit closures, while 51% of all programs reported staffing restrictions ranging from hiring freezes to downsizing the number of hospitalists in the group. Salaries decreased in 26% of reporting programs, and 20%-56% described reduced benefits, ranging from less CME/vacation time and stipends to retirement benefits. The three most frequent benefit losses included annual salary increases, educational stipends, and bonuses.

Community hospitals felt the palpable, financial strain of decreasing pediatric admissions well before the pandemic. Hospitals like MedStar Franklin Square Hospital in Baltimore and Harrington Hospital in Southbridge, Mass., had decided to close their pediatrics units before COVID hit. In a 2014 unpublished survey of 349 community PHM (CPHM) programs, 57% of respondents felt that finances and justification for a pediatric program were primary concerns.

Responding to financial stressors is not a novel challenge for CPHM programs. To keep these vital pediatric programs in place despite lower inpatient volumes, those of us in CPHM have learned many lessons over the years on how to adapt. Such adaptations have included diversification in procedures and multifloor coverage in the hospital. Voiding cystourethrogram catheterizations and circumcisions are now more commonly performed by CPHM providers, who may also cover multiple areas of the hospital, including the ED, NICU, and well-newborn nursery. Comanagement of subspecialty or surgical patients is yet another example of such diversification.

Furthermore, the PERC survey showed that some PHM programs temporarily covered pediatric ICUs and step-down units and began doing ED and urgent care coverage as primary providers Most programs reported no change in newborn visits while 16% reported an increase in newborn volume and 14% reported a decrease in newborn volume. My own health system was one of the groups that had an increase in newborn volume. This was caused by community pediatricians who had stopped coming in to see their own newborns. This coverage adjustment has yet to return to baseline and will likely become permanent.

There was a 11% increase from prepandemic baselines (from 9% to 20%) in programs doing telemedicine. Most respondents stated that they will continue to offer telemedicine with an additional 25% of programs considering starting. There was also a slight increase during the pandemic of coverage of mental health units (from 11% to 13%), which may have led 11% of respondents to consider the addition of this service. The survey also noted that about 28% of PHM programs performed circumcisions, frenectomies, and sedation prepandemic, and 14%-18% are considering adding these services.

Overall, the financial stressors are improving, but our need to adapt in PHM is more pressing than ever. The pandemic has given us the push for evolution and some opportunities that did not exist before. One is the use of telemedicine to expand our subspecialty support to community hospitals, as well as to children’s hospitals in areas where subspecialists are in short supply. These telemedicine consults are being reimbursed for the first time, which allows more access to these services.

With the pandemic, many hospitals are moving to single room occupancy models. Construction to add more beds is costly, and unnecessary if we can utilize community hospitals to keep appropriate patients in their home communities. The opportunity to partner with community hospital programs to provide telemedicine support should not be overlooked. This is also an opportunity for academic referral centers to have more open beds for critical care and highly specialized patients.

Another opportunity is to expand scope by changing age limits, as 18% of respondents to the PERC survey reported that they had started to care for adults since the pandemic. The Pediatric Overflow Planning Contingency Response Network (POPCoRN) has been a valuable resource for education on caring for adults, guidance on which patient populations are appropriate, and the resources needed to do this. While caring for older adults, even in their 90s, was a pandemic-related phenomenon, there is an opportunity to see if the age limit we care for should be raised to 21, or even 25, as some CPHM programs had been doing prepandemic.

Along with the expansion of age limits, there are many other areas of opportunity highlighted within the PERC survey. These include expanding coverage within pediatric ICUs, EDs, and urgent care areas, along with coverage of well newborns that were previously covered by community pediatricians. Also, the increase of mental health admissions is another area where PHM programs might expand their services.

While I hope the financial stressors improve, hope is not a plan and therefore we need to think and prepare for what the post-COVID future may look like. Some have predicted a rebound pediatric respiratory surge next year as the masks come off and children return to in-person learning and daycare. This may be true, but we would be foolish not to use lessons from the pandemic as well as the past to consider options in our toolkit to become more financially stable. POPCoRN, as well as the American Academy of Pediatrics’ listserv and subcommittees, have been a source of collaboration and shared knowledge during a time when we have needed to quickly respond to ever-changing information. These networks and information sharing should be leveraged once the dust settles for us to prepare for future challenges.

New innovations may arise as we look at how we address the growing need for mental health services and incorporate new procedures, like point of care ultrasound. As Charles Darwin said: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.” It is time for us to evolve.

Dr. Dias is a clinical associate professor of pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in the division of pediatric hospital medicine. She has practiced community pediatric hospital medicine for over 21 years in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut. She is the chair of the Education Working Group for the AAP’s section on hospital medicine’s subcommittee on community hospitalists as well as the cochair of the Community Hospital Operations Group of the POPCoRN network.

New guidelines on antibiotic prescribing focus on shorter courses

An antibiotic course of 5 days is usually just as effective as longer courses but with fewer side effects and decreased overall antibiotic exposure for a number of common bacterial conditions, according to new clinical guidelines published by the American College of Physicians.

The guidelines focus on treatment of uncomplicated cases involving pneumonia, urinary tract infections (UTIs), cellulitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations, and acute bronchitis. The goal of the guidelines is to continue improving antibiotic stewardship given the increasing threat of antibiotic resistance and the adverse effects of antibiotics.

“Any use of antibiotics (including necessary use) has downstream effects outside of treating infection,” Dawn Nolt, MD, MPH, a professor of pediatric infection disease at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview. Dr. Nolt was not involved in developing these guidelines. “Undesirable outcomes include allergic reactions, diarrhea, and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. When we reduce unnecessary antibiotic, we reduce undesirable outcomes,” she said.

According to background information in the paper, 1 in 10 patients receives an antibiotic prescription during visits, yet nearly a third of these (30%) are unnecessary and last too long, especially for sinusitis and bronchitis. Meanwhile, overuse of antibiotics, particularly broad-spectrum ones, leads to resistance and adverse effects in up to 20% of patients.

“Prescribing practices can vary based on the type of provider, the setting where the antibiotic is being prescribed, what geographic area you are looking at, the medical reason for which the antibiotic is being prescribed, the actual germ being targeted, and the type of patient,” Dr. Nolt said. “But this variability can be reduced when prescribing providers are aware and follow best practice standards as through this article.”

The new ACP guidelines are a distillation of recommendations from preexisting infectious disease organizations, Dr. Nolt said, but aimed specifically at those practicing internal medicine.

“We define appropriate antibiotic use as prescribing the right antibiotic at the right dose for the right duration for a specific condition,” Rachael A. Lee, MD, MSPH, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and colleagues wrote in the article detailing the new guidelines. “Despite evidence and guidelines supporting shorter durations of antibiotic use, many physicians do not prescribe short-course therapy, frequently defaulting to 10-day courses regardless of the condition.”

The reasons for this default response vary. Though some clinicians prescribe longer courses specifically to prevent antibiotic resistance, no evidence shows that continuing to take antibiotics after symptoms have resolved actually reduces likelihood of resistance, the authors noted.

“In fact, resistance is a documented side effect of prolonged antibiotic use due to natural selection pressure,” they wrote.

Another common reason is habit.

“This was the ‘conventional wisdom’ for so long, just trying to make sure all bacteria causing the infection were completely eradicated, with no stragglers that had been exposed to the antibiotic but were not gone and now could evolve into resistant organisms,” Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, a primary care physician and president of the ACP, said in an interview. “While antibiotic stewardship has been very important for over a decade, we now have more recent head-to-head studies/data showing that, in these four conditions, shorter courses of treatment are just as efficacious with less side effects and adverse events.”

The researchers reviewed all existing clinical guidelines related to bronchitis with COPD exacerbations, community-acquired pneumonia, UTIs, and cellulitis, as well as any other relevant studies in the literature. Although they did not conduct a formal systematic review, they compiled the guidelines specifically for all internists, family physicians and other clinicians caring for patients with these conditions.

“Although most patients with these infections will be seen in the outpatient setting, these best-practice advice statements also apply to patients who present in the inpatient setting,” the authors wrote. They also note the importance of ensuring the patient has the correct diagnosis and appropriate corresponding antibiotic prescription. “If a patient is not improving with appropriate antibiotics, it is important for the clinician to reassess for other causes of symptoms rather than defaulting to a longer duration of antibiotic therapy,” they wrote, calling a longer course “the exception and not the rule.”

Acute bronchitis with COPD exacerbations

Antibiotic treatment for COPD exacerbations and acute uncomplicated bronchitis with signs of a bacterial infection should last no longer than 5 days. The authors define this condition as an acute respiratory infection with a normal chest x-ray, most often caused by a virus. Although patients with bronchitis do not automatically need antibiotics if there’s no evidence of pneumonia, the authors did advise antibiotics in cases involving COPD and a high likelihood of bacterial infection. Clinicians should base their choice of antibiotics on the most common bacterial etiology: Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Ideal candidates for therapy may include aminopenicillin with clavulanic acid, a macrolide, or a tetracycline.

Community-acquired pneumonia

The initial course of antibiotics should be at least 5 days for pneumonia and only extended after considering validated evidence of the patient’s clinical stability, such as resuming normal vital signs, mental activity, and the ability to eat. Multiple randomized, controlled trials have shown no improved benefit from longer courses, though longer courses are linked to increased adverse events and mortality.

Again, antibiotics used should “cover common pathogens, such as S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus, and atypical pathogens, such as Legionella species,” the authors wrote. Options include “amoxicillin, doxycycline, or a macrolide for healthy adults or a beta-lactam with a macrolide or a respiratory fluoroquinolone in patients with comorbidities.”

UTIs: Uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis

For women’s bacterial cystitis – 75% of which is caused by Escherichia coli – the guidelines recommend nitrofurantoin for 5 days, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 3 days, or fosfomycin as a single dose. For uncomplicated pyelonephritis in both men and women, clinicians can consider fluoroquinolones for 5-7 days or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 14 days, depending on antibiotic susceptibility.

This recommendation does not include UTIs in women who are pregnant or UTIs with other functional abnormalities present, such as obstruction. The authors also intentionally left out acute bacterial prostatitis because of its complexity and how long it can take to treat.

Cellulitis

MRSA, which has been increasing in prevalence, is a leading cause of skin and soft-tissue infections, such as necrotizing infections, cellulitis, and erysipelas. Unless the patient has penetrating trauma, evidence of MRSA infection elsewhere, injection drug use, nasal colonization of MRSA, or systemic inflammatory response syndrome, the guidelines recommend a 5- to 6-day course of cephalosporin, penicillin, or clindamycin, extended only if the infection has not improved in 5 days. Further research can narrow down the most appropriate treatment course.

This guidance does not apply to purulent cellulitis, such as conditions with abscesses, furuncles, or carbuncles that typically require incision and drainage.

Continuing to get the message out

Dr. Fincher emphasized the importance of continuing to disseminate messaging for clinicians about reducing unnecessary antibiotic use.

“In medicine we are constantly bombarded with new information. It is those patients and disease states that we see and treat every day that are especially important for us as physicians and other clinicians to keep our skills and knowledge base up to date when it comes to use of antibiotics,” Dr. Fincher said in an interview. “We just need to continue to educate and push out the data, guidelines, and recommendations.”

Dr. Nolt added that it’s important to emphasize how to translate these national recommendations into local practices since local guidance can also raise awareness and encourage local compliance.

Other strategies for reducing overuse of antibiotics “include restriction on antibiotics available at health care systems (formulary restriction), not allowing use of antibiotics unless there is discussion about the patient’s case (preauthorization), and reviewing cases of patients on antibiotics and advising on next steps (prospective audit and feedback),” she said.

The research was funded by the ACP. Dr. Lee has received personal fees from this news organization and Prime Education. Dr. Fincher owns stock in Johnson & Johnson and Procter and Gamble. Dr. Nolt and the article’s coauthors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An antibiotic course of 5 days is usually just as effective as longer courses but with fewer side effects and decreased overall antibiotic exposure for a number of common bacterial conditions, according to new clinical guidelines published by the American College of Physicians.

The guidelines focus on treatment of uncomplicated cases involving pneumonia, urinary tract infections (UTIs), cellulitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations, and acute bronchitis. The goal of the guidelines is to continue improving antibiotic stewardship given the increasing threat of antibiotic resistance and the adverse effects of antibiotics.

“Any use of antibiotics (including necessary use) has downstream effects outside of treating infection,” Dawn Nolt, MD, MPH, a professor of pediatric infection disease at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview. Dr. Nolt was not involved in developing these guidelines. “Undesirable outcomes include allergic reactions, diarrhea, and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. When we reduce unnecessary antibiotic, we reduce undesirable outcomes,” she said.

According to background information in the paper, 1 in 10 patients receives an antibiotic prescription during visits, yet nearly a third of these (30%) are unnecessary and last too long, especially for sinusitis and bronchitis. Meanwhile, overuse of antibiotics, particularly broad-spectrum ones, leads to resistance and adverse effects in up to 20% of patients.

“Prescribing practices can vary based on the type of provider, the setting where the antibiotic is being prescribed, what geographic area you are looking at, the medical reason for which the antibiotic is being prescribed, the actual germ being targeted, and the type of patient,” Dr. Nolt said. “But this variability can be reduced when prescribing providers are aware and follow best practice standards as through this article.”

The new ACP guidelines are a distillation of recommendations from preexisting infectious disease organizations, Dr. Nolt said, but aimed specifically at those practicing internal medicine.

“We define appropriate antibiotic use as prescribing the right antibiotic at the right dose for the right duration for a specific condition,” Rachael A. Lee, MD, MSPH, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and colleagues wrote in the article detailing the new guidelines. “Despite evidence and guidelines supporting shorter durations of antibiotic use, many physicians do not prescribe short-course therapy, frequently defaulting to 10-day courses regardless of the condition.”

The reasons for this default response vary. Though some clinicians prescribe longer courses specifically to prevent antibiotic resistance, no evidence shows that continuing to take antibiotics after symptoms have resolved actually reduces likelihood of resistance, the authors noted.

“In fact, resistance is a documented side effect of prolonged antibiotic use due to natural selection pressure,” they wrote.

Another common reason is habit.

“This was the ‘conventional wisdom’ for so long, just trying to make sure all bacteria causing the infection were completely eradicated, with no stragglers that had been exposed to the antibiotic but were not gone and now could evolve into resistant organisms,” Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, a primary care physician and president of the ACP, said in an interview. “While antibiotic stewardship has been very important for over a decade, we now have more recent head-to-head studies/data showing that, in these four conditions, shorter courses of treatment are just as efficacious with less side effects and adverse events.”

The researchers reviewed all existing clinical guidelines related to bronchitis with COPD exacerbations, community-acquired pneumonia, UTIs, and cellulitis, as well as any other relevant studies in the literature. Although they did not conduct a formal systematic review, they compiled the guidelines specifically for all internists, family physicians and other clinicians caring for patients with these conditions.

“Although most patients with these infections will be seen in the outpatient setting, these best-practice advice statements also apply to patients who present in the inpatient setting,” the authors wrote. They also note the importance of ensuring the patient has the correct diagnosis and appropriate corresponding antibiotic prescription. “If a patient is not improving with appropriate antibiotics, it is important for the clinician to reassess for other causes of symptoms rather than defaulting to a longer duration of antibiotic therapy,” they wrote, calling a longer course “the exception and not the rule.”

Acute bronchitis with COPD exacerbations

Antibiotic treatment for COPD exacerbations and acute uncomplicated bronchitis with signs of a bacterial infection should last no longer than 5 days. The authors define this condition as an acute respiratory infection with a normal chest x-ray, most often caused by a virus. Although patients with bronchitis do not automatically need antibiotics if there’s no evidence of pneumonia, the authors did advise antibiotics in cases involving COPD and a high likelihood of bacterial infection. Clinicians should base their choice of antibiotics on the most common bacterial etiology: Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Ideal candidates for therapy may include aminopenicillin with clavulanic acid, a macrolide, or a tetracycline.

Community-acquired pneumonia

The initial course of antibiotics should be at least 5 days for pneumonia and only extended after considering validated evidence of the patient’s clinical stability, such as resuming normal vital signs, mental activity, and the ability to eat. Multiple randomized, controlled trials have shown no improved benefit from longer courses, though longer courses are linked to increased adverse events and mortality.

Again, antibiotics used should “cover common pathogens, such as S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus, and atypical pathogens, such as Legionella species,” the authors wrote. Options include “amoxicillin, doxycycline, or a macrolide for healthy adults or a beta-lactam with a macrolide or a respiratory fluoroquinolone in patients with comorbidities.”

UTIs: Uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis

For women’s bacterial cystitis – 75% of which is caused by Escherichia coli – the guidelines recommend nitrofurantoin for 5 days, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 3 days, or fosfomycin as a single dose. For uncomplicated pyelonephritis in both men and women, clinicians can consider fluoroquinolones for 5-7 days or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 14 days, depending on antibiotic susceptibility.

This recommendation does not include UTIs in women who are pregnant or UTIs with other functional abnormalities present, such as obstruction. The authors also intentionally left out acute bacterial prostatitis because of its complexity and how long it can take to treat.

Cellulitis

MRSA, which has been increasing in prevalence, is a leading cause of skin and soft-tissue infections, such as necrotizing infections, cellulitis, and erysipelas. Unless the patient has penetrating trauma, evidence of MRSA infection elsewhere, injection drug use, nasal colonization of MRSA, or systemic inflammatory response syndrome, the guidelines recommend a 5- to 6-day course of cephalosporin, penicillin, or clindamycin, extended only if the infection has not improved in 5 days. Further research can narrow down the most appropriate treatment course.

This guidance does not apply to purulent cellulitis, such as conditions with abscesses, furuncles, or carbuncles that typically require incision and drainage.

Continuing to get the message out

Dr. Fincher emphasized the importance of continuing to disseminate messaging for clinicians about reducing unnecessary antibiotic use.

“In medicine we are constantly bombarded with new information. It is those patients and disease states that we see and treat every day that are especially important for us as physicians and other clinicians to keep our skills and knowledge base up to date when it comes to use of antibiotics,” Dr. Fincher said in an interview. “We just need to continue to educate and push out the data, guidelines, and recommendations.”

Dr. Nolt added that it’s important to emphasize how to translate these national recommendations into local practices since local guidance can also raise awareness and encourage local compliance.

Other strategies for reducing overuse of antibiotics “include restriction on antibiotics available at health care systems (formulary restriction), not allowing use of antibiotics unless there is discussion about the patient’s case (preauthorization), and reviewing cases of patients on antibiotics and advising on next steps (prospective audit and feedback),” she said.

The research was funded by the ACP. Dr. Lee has received personal fees from this news organization and Prime Education. Dr. Fincher owns stock in Johnson & Johnson and Procter and Gamble. Dr. Nolt and the article’s coauthors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An antibiotic course of 5 days is usually just as effective as longer courses but with fewer side effects and decreased overall antibiotic exposure for a number of common bacterial conditions, according to new clinical guidelines published by the American College of Physicians.

The guidelines focus on treatment of uncomplicated cases involving pneumonia, urinary tract infections (UTIs), cellulitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations, and acute bronchitis. The goal of the guidelines is to continue improving antibiotic stewardship given the increasing threat of antibiotic resistance and the adverse effects of antibiotics.

“Any use of antibiotics (including necessary use) has downstream effects outside of treating infection,” Dawn Nolt, MD, MPH, a professor of pediatric infection disease at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview. Dr. Nolt was not involved in developing these guidelines. “Undesirable outcomes include allergic reactions, diarrhea, and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. When we reduce unnecessary antibiotic, we reduce undesirable outcomes,” she said.

According to background information in the paper, 1 in 10 patients receives an antibiotic prescription during visits, yet nearly a third of these (30%) are unnecessary and last too long, especially for sinusitis and bronchitis. Meanwhile, overuse of antibiotics, particularly broad-spectrum ones, leads to resistance and adverse effects in up to 20% of patients.

“Prescribing practices can vary based on the type of provider, the setting where the antibiotic is being prescribed, what geographic area you are looking at, the medical reason for which the antibiotic is being prescribed, the actual germ being targeted, and the type of patient,” Dr. Nolt said. “But this variability can be reduced when prescribing providers are aware and follow best practice standards as through this article.”

The new ACP guidelines are a distillation of recommendations from preexisting infectious disease organizations, Dr. Nolt said, but aimed specifically at those practicing internal medicine.

“We define appropriate antibiotic use as prescribing the right antibiotic at the right dose for the right duration for a specific condition,” Rachael A. Lee, MD, MSPH, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and colleagues wrote in the article detailing the new guidelines. “Despite evidence and guidelines supporting shorter durations of antibiotic use, many physicians do not prescribe short-course therapy, frequently defaulting to 10-day courses regardless of the condition.”

The reasons for this default response vary. Though some clinicians prescribe longer courses specifically to prevent antibiotic resistance, no evidence shows that continuing to take antibiotics after symptoms have resolved actually reduces likelihood of resistance, the authors noted.

“In fact, resistance is a documented side effect of prolonged antibiotic use due to natural selection pressure,” they wrote.

Another common reason is habit.

“This was the ‘conventional wisdom’ for so long, just trying to make sure all bacteria causing the infection were completely eradicated, with no stragglers that had been exposed to the antibiotic but were not gone and now could evolve into resistant organisms,” Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, a primary care physician and president of the ACP, said in an interview. “While antibiotic stewardship has been very important for over a decade, we now have more recent head-to-head studies/data showing that, in these four conditions, shorter courses of treatment are just as efficacious with less side effects and adverse events.”

The researchers reviewed all existing clinical guidelines related to bronchitis with COPD exacerbations, community-acquired pneumonia, UTIs, and cellulitis, as well as any other relevant studies in the literature. Although they did not conduct a formal systematic review, they compiled the guidelines specifically for all internists, family physicians and other clinicians caring for patients with these conditions.

“Although most patients with these infections will be seen in the outpatient setting, these best-practice advice statements also apply to patients who present in the inpatient setting,” the authors wrote. They also note the importance of ensuring the patient has the correct diagnosis and appropriate corresponding antibiotic prescription. “If a patient is not improving with appropriate antibiotics, it is important for the clinician to reassess for other causes of symptoms rather than defaulting to a longer duration of antibiotic therapy,” they wrote, calling a longer course “the exception and not the rule.”

Acute bronchitis with COPD exacerbations

Antibiotic treatment for COPD exacerbations and acute uncomplicated bronchitis with signs of a bacterial infection should last no longer than 5 days. The authors define this condition as an acute respiratory infection with a normal chest x-ray, most often caused by a virus. Although patients with bronchitis do not automatically need antibiotics if there’s no evidence of pneumonia, the authors did advise antibiotics in cases involving COPD and a high likelihood of bacterial infection. Clinicians should base their choice of antibiotics on the most common bacterial etiology: Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Ideal candidates for therapy may include aminopenicillin with clavulanic acid, a macrolide, or a tetracycline.

Community-acquired pneumonia

The initial course of antibiotics should be at least 5 days for pneumonia and only extended after considering validated evidence of the patient’s clinical stability, such as resuming normal vital signs, mental activity, and the ability to eat. Multiple randomized, controlled trials have shown no improved benefit from longer courses, though longer courses are linked to increased adverse events and mortality.

Again, antibiotics used should “cover common pathogens, such as S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus, and atypical pathogens, such as Legionella species,” the authors wrote. Options include “amoxicillin, doxycycline, or a macrolide for healthy adults or a beta-lactam with a macrolide or a respiratory fluoroquinolone in patients with comorbidities.”

UTIs: Uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis

For women’s bacterial cystitis – 75% of which is caused by Escherichia coli – the guidelines recommend nitrofurantoin for 5 days, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 3 days, or fosfomycin as a single dose. For uncomplicated pyelonephritis in both men and women, clinicians can consider fluoroquinolones for 5-7 days or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 14 days, depending on antibiotic susceptibility.

This recommendation does not include UTIs in women who are pregnant or UTIs with other functional abnormalities present, such as obstruction. The authors also intentionally left out acute bacterial prostatitis because of its complexity and how long it can take to treat.

Cellulitis

MRSA, which has been increasing in prevalence, is a leading cause of skin and soft-tissue infections, such as necrotizing infections, cellulitis, and erysipelas. Unless the patient has penetrating trauma, evidence of MRSA infection elsewhere, injection drug use, nasal colonization of MRSA, or systemic inflammatory response syndrome, the guidelines recommend a 5- to 6-day course of cephalosporin, penicillin, or clindamycin, extended only if the infection has not improved in 5 days. Further research can narrow down the most appropriate treatment course.

This guidance does not apply to purulent cellulitis, such as conditions with abscesses, furuncles, or carbuncles that typically require incision and drainage.

Continuing to get the message out

Dr. Fincher emphasized the importance of continuing to disseminate messaging for clinicians about reducing unnecessary antibiotic use.

“In medicine we are constantly bombarded with new information. It is those patients and disease states that we see and treat every day that are especially important for us as physicians and other clinicians to keep our skills and knowledge base up to date when it comes to use of antibiotics,” Dr. Fincher said in an interview. “We just need to continue to educate and push out the data, guidelines, and recommendations.”

Dr. Nolt added that it’s important to emphasize how to translate these national recommendations into local practices since local guidance can also raise awareness and encourage local compliance.

Other strategies for reducing overuse of antibiotics “include restriction on antibiotics available at health care systems (formulary restriction), not allowing use of antibiotics unless there is discussion about the patient’s case (preauthorization), and reviewing cases of patients on antibiotics and advising on next steps (prospective audit and feedback),” she said.

The research was funded by the ACP. Dr. Lee has received personal fees from this news organization and Prime Education. Dr. Fincher owns stock in Johnson & Johnson and Procter and Gamble. Dr. Nolt and the article’s coauthors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

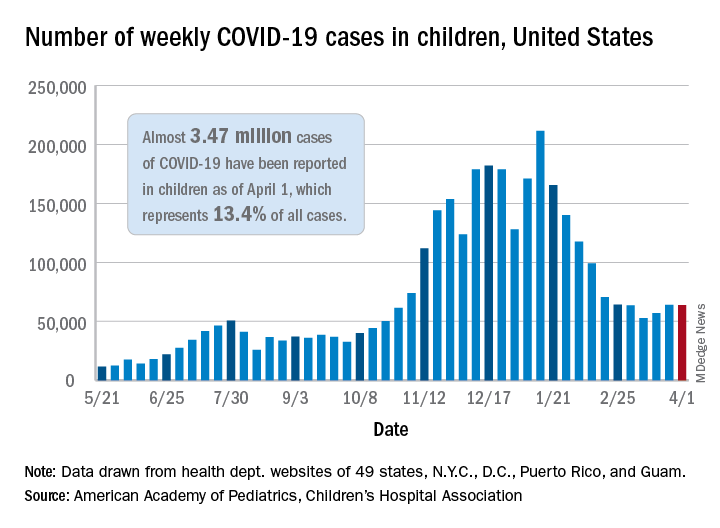

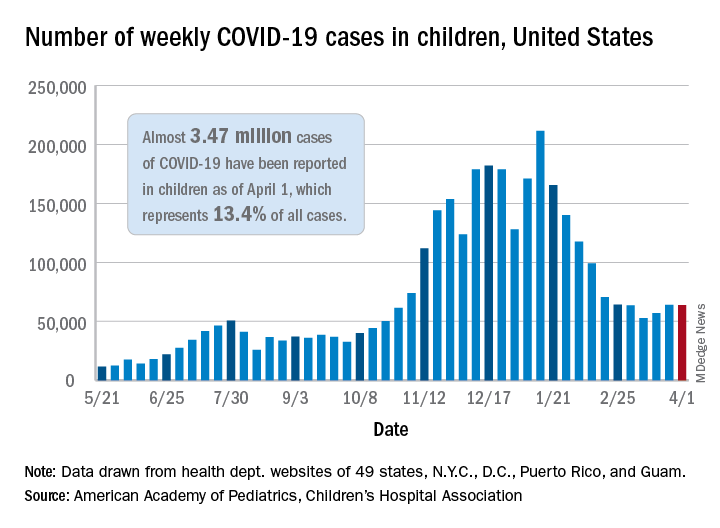

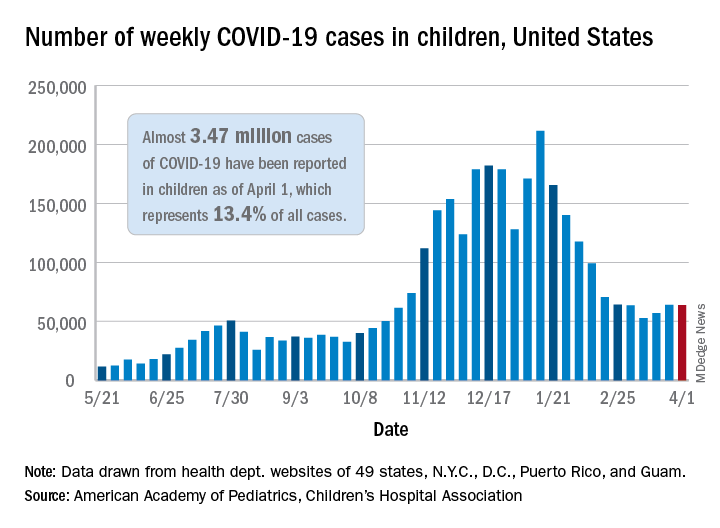

COVID-19 in children: New cases back on the decline

New cases of COVID-19 in children in the United States fell slightly, but even that small dip was enough to reverse 2 straight weeks of increases, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. For the week ending April 1, children represented 18.1% of all new cases reported in the United States, down from a pandemic-high 19.1% the week before.

COVID-19 cases in children now total just under 3.47 million, which works out to 13.4% of reported cases for all ages and 4,610 cases per 100,000 children since the beginning of the pandemic, the AAP and the CHA said based on data from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Among those jurisdictions, Vermont has the highest proportion of its cases occurring in children at 21.0%, and North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 8,958 cases per 100,000 children. Looking at those states from the bottoms of their respective lists are Florida, where children aged 0-14 years represent 8.4% of all cases, and Hawaii, with 1,133 cases per 100,000 children aged 0-17 years, the AAP/CHA report shows.

The data on more serious illness show that Minnesota has the highest proportion of hospitalizations occurring in children at 3.1%, while New York City has the highest hospitalization rate among infected children, 2.0%. Among the other 23 states reporting on such admissions, children make up only 1.3% of hospitalizations in Florida and in New Hampshire, which also has the lowest hospitalization rate at 0.1%, the AAP and CHA said.

Five more deaths were reported in children during the week ending April 1, bringing the total to 284 in the 43 states, along with New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, that are sharing age-distribution data on mortality.

New cases of COVID-19 in children in the United States fell slightly, but even that small dip was enough to reverse 2 straight weeks of increases, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. For the week ending April 1, children represented 18.1% of all new cases reported in the United States, down from a pandemic-high 19.1% the week before.

COVID-19 cases in children now total just under 3.47 million, which works out to 13.4% of reported cases for all ages and 4,610 cases per 100,000 children since the beginning of the pandemic, the AAP and the CHA said based on data from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Among those jurisdictions, Vermont has the highest proportion of its cases occurring in children at 21.0%, and North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 8,958 cases per 100,000 children. Looking at those states from the bottoms of their respective lists are Florida, where children aged 0-14 years represent 8.4% of all cases, and Hawaii, with 1,133 cases per 100,000 children aged 0-17 years, the AAP/CHA report shows.

The data on more serious illness show that Minnesota has the highest proportion of hospitalizations occurring in children at 3.1%, while New York City has the highest hospitalization rate among infected children, 2.0%. Among the other 23 states reporting on such admissions, children make up only 1.3% of hospitalizations in Florida and in New Hampshire, which also has the lowest hospitalization rate at 0.1%, the AAP and CHA said.

Five more deaths were reported in children during the week ending April 1, bringing the total to 284 in the 43 states, along with New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, that are sharing age-distribution data on mortality.

New cases of COVID-19 in children in the United States fell slightly, but even that small dip was enough to reverse 2 straight weeks of increases, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. For the week ending April 1, children represented 18.1% of all new cases reported in the United States, down from a pandemic-high 19.1% the week before.

COVID-19 cases in children now total just under 3.47 million, which works out to 13.4% of reported cases for all ages and 4,610 cases per 100,000 children since the beginning of the pandemic, the AAP and the CHA said based on data from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Among those jurisdictions, Vermont has the highest proportion of its cases occurring in children at 21.0%, and North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 8,958 cases per 100,000 children. Looking at those states from the bottoms of their respective lists are Florida, where children aged 0-14 years represent 8.4% of all cases, and Hawaii, with 1,133 cases per 100,000 children aged 0-17 years, the AAP/CHA report shows.

The data on more serious illness show that Minnesota has the highest proportion of hospitalizations occurring in children at 3.1%, while New York City has the highest hospitalization rate among infected children, 2.0%. Among the other 23 states reporting on such admissions, children make up only 1.3% of hospitalizations in Florida and in New Hampshire, which also has the lowest hospitalization rate at 0.1%, the AAP and CHA said.

Five more deaths were reported in children during the week ending April 1, bringing the total to 284 in the 43 states, along with New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, that are sharing age-distribution data on mortality.

Hospital medicine around the world

Similar needs, local adaptations

Hospital medicine has evolved rapidly and spread widely across the United States in the past 25 years in response to the health care system’s needs for patient safety, quality, efficiency, and effective coordination of care in the ever-more complex environment of the acute care hospital.

But hospital care can be just as complex in other countries, so it’s not surprising that there’s a lot of interest around the world in the U.S. model of hospital medicine. But adaptations of that model vary across – and within – countries, reflecting local culture, health care systems, payment models, and approaches to medical education.

Other countries have looked to U.S. experts for consultations, to U.S.-trained doctors who might be willing to relocate, and to the Society of Hospital Medicine as an internationally focused source of networking and other resources. Some U.S.-based institutions, led by the Cleveland Clinic, Johns Hopkins Medicine, and Weill-Cornell Medical School, have established teaching outposts in other countries, with opportunities for resident training that prepares future hospitalists on the ground.

SHM CEO Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, said that he personally has interacted with developing hospital medicine programs in six countries, who called upon him in part because of his past research on managing length of hospital stays. Dr. Howell counts himself among a few dozen U.S. hospitalists who are regularly invited to come and consult or to give talks to established or developing hospitalist programs in other countries. Because of the COVID-19 epidemic, in-person visits to other countries have largely been curtailed, but that has introduced a more virtual world of online meetings.

“I think the interesting thing about the ‘international consultants’ for hospital medicine is that while they come from professionally diverse backgrounds, they are all working to solve remarkably similar problems: How to make health care more affordable and higher quality while staying abreast of up-to-date best practice for physicians,” he said.

“Hospital care is costly no matter where you go. Other countries are also trying to limit expense in ways that don’t compromise the quality of that care,” Dr. Howell said. Also, hospitalized patients are more complex than ever, with increasing severity of illness and comorbidities, which makes having a hospitalist available on site more important.

Dr. Howell hopes to encourage more dialogue with international colleagues. SHM has established collaborations with medical societies in other countries and makes time at its conferences for international hospitalist participants to meet and share their experiences. Hospitalists from 33 countries were represented at SHM’s 2017 conference, and the upcoming virtual SHM Converge, May 3-7, 2021, includes a dedicated international session. SHM chapters have formed in a number of other countries.

Flora Kisuule, MD, MPH, SFHM, director of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, said her international hospital medicine work1 started 7 years ago when she was invited to the Middle East to help Aramco, the Saudi Arabian Oil Company, develop a hospital medicine program based on the U.S. model for its employees. This was a joint venture with Johns Hopkins Medicine. “We went there and looked at their processes and made recommendations such as duration of hospitalist shifts and how to expand the footprint of hospital medicine in the hospital,” she said.

Then Dr. Kisuule was asked to help develop a hospital medicine program in Panama, where the drivers for developing hospital medicine were improving quality of care and ensuring patient safety. The biggest barrier has been remuneration and how to pay salaries that will allow doctors to work at only one hospital. In Panama, doctors typically work at multiple hospitals or clinics so they can earn enough to make ends meet.

The need for professional identity

Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, “grew up” professionally in hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, a pioneering institution for hospital medicine, and in SHM. “We used to say: If you’ve seen one hospital medicine group, you’ve seen one hospital medicine group,” she said.

Dr. Vidyarthi went to Singapore in 2011, taking a job as a hospitalist at Singapore General Hospital and the affiliated Duke–National University Medical School, eventually directing the Division of Advanced Internal Medicine (general and hospital medicine) at the National University Health System, before moving back to UCSF in 2020.

“Professional identity is one of the biggest benefits hospital medicine can bestow in Singapore and across Asia, where general medicine is underdeveloped. Just as it did 20 years ago in the U.S., that professional identity offers a road map to achieving competency in practicing medicine in the hospital setting,” Dr. Vidyarthi said.

At UCSF, the professional identity of a hospitalist is broad but defined. The research agenda, quality, safety, and educational competencies are specific, seen through a system lens, she added. “We take pride in that professional identify. This is an opportunity for countries where general medicine is underdeveloped and undervalued.”

But the term hospital medicine – or the American model – isn’t always welcomed by health care systems in other countries, Dr Vidyarthi said. “The label of 'hospital medicine' brings people together in professional identify, and that professional identity opens doors. But for it to have legs in other countries, those skills need to be of value to the local system. It needs to make sense, as it did in the United States, and to add value for the identified gaps that need to be filled.”

In Singapore, the health care system turned to the model of acute medical units (AMUs) and the acute medicine physician specialty developed in the United Kingdom, which created a new way of delivering care, a new geography of care, and new set of competencies around which to build training and certification.

AMUs manage the majority of acute medical patients who present to the emergency department and get admitted, with initial treatment for a maximum of 72 hours. Acute physicians, trained in the specialty of assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of adult patients with urgent medical needs, work in a unit situated between the emergency department entrance and the specialty care units. This specialty has been recognized since 2009.2

“Acute medicine is the standard care model in the UK and is now found in all government hospitals in Singapore. This model is being adapted across Europe, Asia, and the Pacific Islands,” Dr. Vidyarthi said. “Advantages include the specific geography of the unit, and outcomes that are value-added to these systems such as decreased use of hospital beds in areas with very high bed occupancy rates.”

In many locales, a variety of titles are used to describe doctors who are not hospitalists as we understand them but whose work is based in the hospital, including house officer, duty officer, junior officer, registrar, or general practitioner. Often these hospital-based doctors, who may in fact be residents or nongraduated trainees, lack the training and the scope of practice of a hospitalist. Because they typically need to consult the supervising physician before making inpatient management decisions, they aren’t able to provide the timely response to the patient’s changing medical condition that is needed to manage today’s acute patients.

Defining the fee schedule

In South Korea, a hospitalist model has emerged since 2015 in response to the insufficient number of hospital-based physicians needed to cover all admitted patients and to address related issues of patient safety, health care quality, and limitations on total hours per week medical residents are allowed to work.

South Korea in 1989 adopted a universal National Health Insurance System (NHIS), which took 12 years to implement. But inadequate coverage for medical work in the hospital has deterred physicians from choosing to work there. South Korea had longer lengths of hospital stay, fewer practicing physicians per 1,000 patients, and a much higher number of hospital patients per practicing physician than other countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, according to a new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine detailing hospitalist development in South Korea.3

A council representing leading medical associations was formed to develop a South Korean hospitalist system and charged by the Ministry of Health with designing an official proposal for implementing it. A pilot study focused on quality and on defining a fee schedule for hospital work was tested in four hospitals, and then a second phase in 31 of South Korea’s 344 general hospitals tested the proposed fee schedule, said Wonjeong Chae, MPH, the first named author on the study, based in the Department of Public Health in the College of Medicine at Yonsei University in Seoul. “But we’re still working on making the fee schedule better,” she said.

Ms. Chae estimates that there are about 250 working hospitalists in South Korea today, which leaves a lot of gaps in practice. “We did learn from America, but we have a different system, so the American concept had to be adapted. Hospital medicine is still growing in Korea despite the impact of the pandemic. We are at the beginning stages of development, but we expect it will grow more with government support.”

In Brazil, a handful of hospital medicine pioneers such as Guilherme Barcellos, MD, SFHM, in Porto Alegre have tried to grow the hospitalist model, networking with colleagues across Latin America through the Pan American Society of Hospitalists and the Brazilian chapter of SHM.

Individual hospitals have developed hospitalist programs, but there is no national model to lead the way. Frequent turnover for the Minister of Health position has made it harder to develop consistent national policy, and the country is largely still in the early stages of developing hospital medicine, depending on isolated initiatives, as Dr. Barcellos described it in a November 2015 article in The Hospitalist.4 Growth is slow but continuing, with new programs such as the one led by Reginaldo Filho, MD at Hospital São Vicente in Curitiba standing out in the confrontation against COVID-19, Dr. Barcellos said.

What can we learn from others?

India-born, U.S.-trained hospitalist Anand Kartha, MD, MS, SFHM, currently heads the Hospital Medicine Program at Hamad General Hospital in Doha, Qatar. He moved from Boston to this small nation on the Arabian Peninsula in 2014. Under the leadership of the hospital’s Department of Medicine, this program was developed to address difficulties such as scheduling, transitions of care, and networking with home care and other providers – the same issues seen in hospitals around the world.

These are not novel problems, Dr. Kartha said, but all of them have a common solution in evidence-based practice. “As hospitalists, our key is to collaborate with everyone in the hospital, using the multidisciplinary approach that is a unique feature of hospital medicine.”

The model has continued to spread across hospitals in Qatar, including academic and community programs. “We now have a full-fledged academic hospitalist system, which collaborates with community hospitals and community programs including a women’s hospital and an oncologic hospital,” he said. “Now the focus is on expanding resource capacity and the internal pipeline for hospitalists. I am getting graduates from Weill Cornell Medicine in Qatar.” Another key collaborator has been the Boston-based Institute for Healthcare Improvement, helping to develop best practices in Qatar and sponsoring the annual Middle East Forum on Quality and Safety in Health Care.

The residency training program at Hamad General is accredited by ACGME, with the same expected competencies as in the U.S. “We don’t use the term ‘hospitalist,’ ” Dr. Kartha said. “It’s better to focus on the model of care – which clearly was American. That model has encountered some resistance in some countries – on many of the same grounds U.S. hospitalists faced 20 years ago. You have to be sensitive to local culture. For hospitalists to succeed internationally, they have to possess a high degree of cultural intelligence.” There’s no shortage of issues such as language barriers, he said. “But that’s no different than at Boston Medical Center.”

SHM’s Middle East Chapter was off to a great start and then was slowed down by regional politics and COVID-19, but is looking forward to a great reboot in 2021, Dr. Kartha said. The pandemic also has been an opportunity to show how hospital medicine is the backbone of the hospital’s ability to respond, although of course many other professionals also pitched in.

Other countries around the world have learned a lot from the American model of hospital medicine. But sources for this article wonder if U.S. hospitalists, in turn, could learn from their adaptations and innovations.

“We can all learn better how to practice our field of medicine in the hospital with less resource utilization,” Dr. Vidyarthi concluded. “So many innovations are happening around us. If we open our eyes to our global colleagues and infuse some of their ideas, it could be wonderful for hospital professionals in the United States.”

References

1. Kisuule F, Howell E. Hospital medicine beyond the United States. Int J Gen Med. 2018;11:65-71. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S151275.

2. Stosic J et al. The acute physician: The future of acute hospital care in the UK. Clin Med (Lond). 2010 Apr; 10(2):145-7. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.10-2-145.

3. Yan Y et al. Adoption of Hospitalist Care in Asia: Experiences From Singapore, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan. J Hosp Med. Published Online First 2021 June 11. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3621.

4. Beresford L. Hospital medicine flourishing around the world. The Hospitalist. Nov 2015.

Similar needs, local adaptations

Similar needs, local adaptations

Hospital medicine has evolved rapidly and spread widely across the United States in the past 25 years in response to the health care system’s needs for patient safety, quality, efficiency, and effective coordination of care in the ever-more complex environment of the acute care hospital.

But hospital care can be just as complex in other countries, so it’s not surprising that there’s a lot of interest around the world in the U.S. model of hospital medicine. But adaptations of that model vary across – and within – countries, reflecting local culture, health care systems, payment models, and approaches to medical education.

Other countries have looked to U.S. experts for consultations, to U.S.-trained doctors who might be willing to relocate, and to the Society of Hospital Medicine as an internationally focused source of networking and other resources. Some U.S.-based institutions, led by the Cleveland Clinic, Johns Hopkins Medicine, and Weill-Cornell Medical School, have established teaching outposts in other countries, with opportunities for resident training that prepares future hospitalists on the ground.

SHM CEO Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, said that he personally has interacted with developing hospital medicine programs in six countries, who called upon him in part because of his past research on managing length of hospital stays. Dr. Howell counts himself among a few dozen U.S. hospitalists who are regularly invited to come and consult or to give talks to established or developing hospitalist programs in other countries. Because of the COVID-19 epidemic, in-person visits to other countries have largely been curtailed, but that has introduced a more virtual world of online meetings.

“I think the interesting thing about the ‘international consultants’ for hospital medicine is that while they come from professionally diverse backgrounds, they are all working to solve remarkably similar problems: How to make health care more affordable and higher quality while staying abreast of up-to-date best practice for physicians,” he said.

“Hospital care is costly no matter where you go. Other countries are also trying to limit expense in ways that don’t compromise the quality of that care,” Dr. Howell said. Also, hospitalized patients are more complex than ever, with increasing severity of illness and comorbidities, which makes having a hospitalist available on site more important.

Dr. Howell hopes to encourage more dialogue with international colleagues. SHM has established collaborations with medical societies in other countries and makes time at its conferences for international hospitalist participants to meet and share their experiences. Hospitalists from 33 countries were represented at SHM’s 2017 conference, and the upcoming virtual SHM Converge, May 3-7, 2021, includes a dedicated international session. SHM chapters have formed in a number of other countries.

Flora Kisuule, MD, MPH, SFHM, director of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, said her international hospital medicine work1 started 7 years ago when she was invited to the Middle East to help Aramco, the Saudi Arabian Oil Company, develop a hospital medicine program based on the U.S. model for its employees. This was a joint venture with Johns Hopkins Medicine. “We went there and looked at their processes and made recommendations such as duration of hospitalist shifts and how to expand the footprint of hospital medicine in the hospital,” she said.

Then Dr. Kisuule was asked to help develop a hospital medicine program in Panama, where the drivers for developing hospital medicine were improving quality of care and ensuring patient safety. The biggest barrier has been remuneration and how to pay salaries that will allow doctors to work at only one hospital. In Panama, doctors typically work at multiple hospitals or clinics so they can earn enough to make ends meet.

The need for professional identity

Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, “grew up” professionally in hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, a pioneering institution for hospital medicine, and in SHM. “We used to say: If you’ve seen one hospital medicine group, you’ve seen one hospital medicine group,” she said.

Dr. Vidyarthi went to Singapore in 2011, taking a job as a hospitalist at Singapore General Hospital and the affiliated Duke–National University Medical School, eventually directing the Division of Advanced Internal Medicine (general and hospital medicine) at the National University Health System, before moving back to UCSF in 2020.

“Professional identity is one of the biggest benefits hospital medicine can bestow in Singapore and across Asia, where general medicine is underdeveloped. Just as it did 20 years ago in the U.S., that professional identity offers a road map to achieving competency in practicing medicine in the hospital setting,” Dr. Vidyarthi said.