User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

FDA authorizes booster shot for immunocompromised Americans

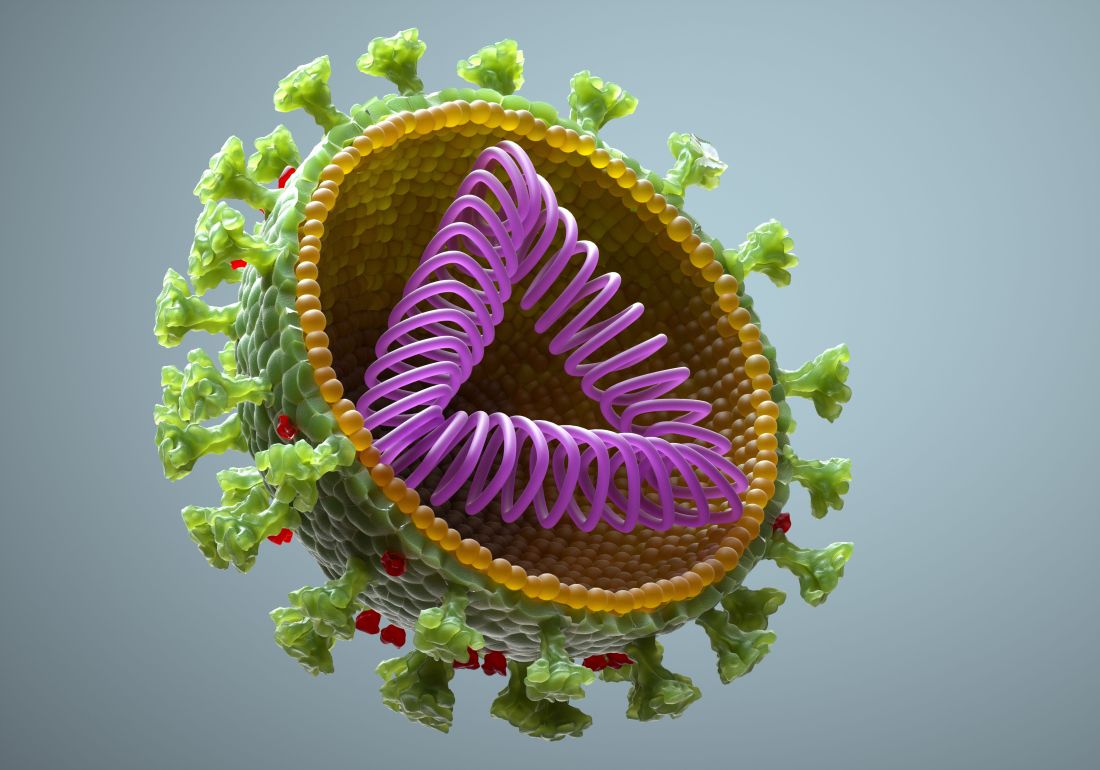

The decision, which came late on Aug. 12, was not unexpected and a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) panel meeting Aug. 13 is expected to approve directions to doctors and health care providers on who should receive the booster shot.

“The country has entered yet another wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the FDA is especially cognizant that immunocompromised people are particularly at risk for severe disease. After a thorough review of the available data, the FDA determined that this small, vulnerable group may benefit from a third dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna Vaccines,” acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, said in a statement.

Those eligible for a third dose include solid organ transplant recipients, those undergoing cancer treatments, and people with autoimmune diseases that suppress their immune systems.

Meanwhile, White House officials said Aug. 12 they “have supply and are prepared” to give all U.S. residents COVID-19 boosters -- which, as of now, are likely to be authorized first only for immunocompromised people.

“We believe sooner or later you will need a booster,” Anthony Fauci, MD, said at a news briefing Aug. 12. “Right now, we are evaluating this on a day-by-day, week-by-week, month-by-month basis.”

He added: “Right at this moment, apart from the immunocompromised -- elderly or not elderly -- people do not need a booster.” But, he said, “We’re preparing for the eventuality of doing that.”

White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said officials “have supply and are prepared” to at some point provide widespread access to boosters.

The immunocompromised population is very small -- less than 3% of adults, said CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 rates continue to rise. Dr. Walensky reported that the 7-day average of daily cases is 132,384 -- an increase of 24% from the previous week. Average daily hospitalizations are up 31%, at 9,700, and deaths are up to 452 -- an increase of 22%.

In the past week, Florida has had more COVID-19 cases than the 30 states with the lowest case rates combined, Mr. Zients said. Florida and Texas alone have accounted for nearly 40% of new hospitalizations across the country.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The decision, which came late on Aug. 12, was not unexpected and a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) panel meeting Aug. 13 is expected to approve directions to doctors and health care providers on who should receive the booster shot.

“The country has entered yet another wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the FDA is especially cognizant that immunocompromised people are particularly at risk for severe disease. After a thorough review of the available data, the FDA determined that this small, vulnerable group may benefit from a third dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna Vaccines,” acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, said in a statement.

Those eligible for a third dose include solid organ transplant recipients, those undergoing cancer treatments, and people with autoimmune diseases that suppress their immune systems.

Meanwhile, White House officials said Aug. 12 they “have supply and are prepared” to give all U.S. residents COVID-19 boosters -- which, as of now, are likely to be authorized first only for immunocompromised people.

“We believe sooner or later you will need a booster,” Anthony Fauci, MD, said at a news briefing Aug. 12. “Right now, we are evaluating this on a day-by-day, week-by-week, month-by-month basis.”

He added: “Right at this moment, apart from the immunocompromised -- elderly or not elderly -- people do not need a booster.” But, he said, “We’re preparing for the eventuality of doing that.”

White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said officials “have supply and are prepared” to at some point provide widespread access to boosters.

The immunocompromised population is very small -- less than 3% of adults, said CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 rates continue to rise. Dr. Walensky reported that the 7-day average of daily cases is 132,384 -- an increase of 24% from the previous week. Average daily hospitalizations are up 31%, at 9,700, and deaths are up to 452 -- an increase of 22%.

In the past week, Florida has had more COVID-19 cases than the 30 states with the lowest case rates combined, Mr. Zients said. Florida and Texas alone have accounted for nearly 40% of new hospitalizations across the country.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The decision, which came late on Aug. 12, was not unexpected and a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) panel meeting Aug. 13 is expected to approve directions to doctors and health care providers on who should receive the booster shot.

“The country has entered yet another wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the FDA is especially cognizant that immunocompromised people are particularly at risk for severe disease. After a thorough review of the available data, the FDA determined that this small, vulnerable group may benefit from a third dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna Vaccines,” acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, said in a statement.

Those eligible for a third dose include solid organ transplant recipients, those undergoing cancer treatments, and people with autoimmune diseases that suppress their immune systems.

Meanwhile, White House officials said Aug. 12 they “have supply and are prepared” to give all U.S. residents COVID-19 boosters -- which, as of now, are likely to be authorized first only for immunocompromised people.

“We believe sooner or later you will need a booster,” Anthony Fauci, MD, said at a news briefing Aug. 12. “Right now, we are evaluating this on a day-by-day, week-by-week, month-by-month basis.”

He added: “Right at this moment, apart from the immunocompromised -- elderly or not elderly -- people do not need a booster.” But, he said, “We’re preparing for the eventuality of doing that.”

White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said officials “have supply and are prepared” to at some point provide widespread access to boosters.

The immunocompromised population is very small -- less than 3% of adults, said CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 rates continue to rise. Dr. Walensky reported that the 7-day average of daily cases is 132,384 -- an increase of 24% from the previous week. Average daily hospitalizations are up 31%, at 9,700, and deaths are up to 452 -- an increase of 22%.

In the past week, Florida has had more COVID-19 cases than the 30 states with the lowest case rates combined, Mr. Zients said. Florida and Texas alone have accounted for nearly 40% of new hospitalizations across the country.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Move from awareness to action to combat racism in medicine

Structural racism and implicit bias are connected, and both must be addressed to move from awareness of racism to action, said Nathan Chomilo, MD, of HealthPartners/Park Nicollet, Brooklyn Center, Minn., in a presentation at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine annual conference.

“We need pediatricians with the courage to address racism head on,” he said.

One step in moving from awareness to action against structural and institutional racism in medicine is examining policies, Dr. Chomilo said. He cited the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 as examples of how policy changes can make a difference, illustrated by data from 1955-1975 that showed a significant decrease in infant deaths among Black infants in Mississippi after 1965.

Medicaid expansion has helped to narrow, but not eliminate, racial disparities in health care, Dr. Chomilo said. The impact of Medicare and Medicaid is evident in the current COVID-19 pandemic, as county level data show that areas where more than 25% of the population are uninsured have higher rates of COVID-19 infections, said Dr. Chomilo. Policies that impact access to care also impact their incidence of chronic diseases and risk for severe disease, he noted.

“If you don’t have ready access to a health care provider, you don’t have access to the vaccine, and you don’t have information that would inform your getting the vaccine,” he added.

Prioritizing the power of voting

“Voting is one of many ways we can impact structural racism in health care policy,” Dr. Chomilo emphasized.

However, voting inequity remains a challenge, Dr. Chomilo noted. Community level disparities lead to inequity in voting access and subsequent disparities in voter participation, he said. “Leaders are less responsive to nonvoting constituents,” which can result in policies that impact health inequitably, and loop back to community level health disparities, he explained.

Historically, physicians have had an 8%-9% lower voter turnout than the general public, although this may have changed in recent elections, Dr. Chomilo said. He encouraged all clinicians to set an example and vote, and to empower their patients to vote. Evidence shows that enfranchisement of Black voters is associated with reductions in education gaps for Blacks and Whites, and that enfranchisement of women is associated with increased spending on children and lower child mortality, he said. Dr. Chomilo encouraged pediatricians and all clinicians to take advantage of the resources on voting available from the American Academy of Pediatrics (aap.org/votekids).

“When we see more people in a community vote, leaders are more responsive to their needs,” he said.

Informing racial identity

“Racial identity is informed by racial socialization,” Dr. Chomilo said. “All of us are socialized along the lines of race; it happens in conversations with parents, family, peers, community.” Another point in moving from awareness to action in eliminating structural racism is recognizing that children are not too young to talk about race, Dr. Chomilo emphasized.

Children start to navigate racial identity and to take note of other differences at an early age. For example, a 3-year-old might ask, “why does that person talk funny, why is that person being pushed in a chair?” Dr. Chomilo said, and it is important for parents and as pediatricians to be prepared for these questions, which are part of normal development. As children get older, they start to reflect on what differences mean for them, which is not rooted in anything negative, he noted.

Children first develop racial identity at home, but children solidify their identities in child care and school settings, Dr. Chomilo said. The American Academy of Pediatrics has acknowledged the potential for racial bias in education and child care, and said in a statement that, “it is critical for pediatricians to recognize the institutional personally mediated, and internalized levels of racism that occur in the educational setting, because education is a critical social determinant of health for children.” In fact, data from children in preschool show that they use racial categories to identify themselves and others, to include or exclude children from activities, and to negotiate power in their social and play networks.

Early intervention matters in educating children about racism, Dr. Chomilo said. “If we were not taught to talk about race, it is on us to learn about it ourselves as well,” he said.

Ultimately, the goal is to create active antiracism among adults and children, said Dr. Chomilo. He encouraged pediatricians and parents not to shut down or discourage children when they raise questions of race, but to take the opportunity to teach. “There may be hurt feelings around what a child said, even if they didn’t mean to offend someone,” he noted. Take the topic seriously, and make racism conversations ongoing; teach children to safely oppose negative messages and behaviors in others, and replace them with something positive, he emphasized.

Addressing bias in clinical settings

Dr. Chomilo also encouraged hospitalists to consider internalized racism in clinical settings and take action to build confidence and cultural pride in all patients by ensuring that a pediatric hospital unit is welcoming and representative of the diversity in a given community, with appropriate options for books, movies, and toys. He also encouraged pediatric hospitalists to assess children for experiences of racism as part of a social assessment. Be aware of signs of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, or grief that might have a racial component, he said.

Dr. Chomilo had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Structural racism and implicit bias are connected, and both must be addressed to move from awareness of racism to action, said Nathan Chomilo, MD, of HealthPartners/Park Nicollet, Brooklyn Center, Minn., in a presentation at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine annual conference.

“We need pediatricians with the courage to address racism head on,” he said.

One step in moving from awareness to action against structural and institutional racism in medicine is examining policies, Dr. Chomilo said. He cited the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 as examples of how policy changes can make a difference, illustrated by data from 1955-1975 that showed a significant decrease in infant deaths among Black infants in Mississippi after 1965.

Medicaid expansion has helped to narrow, but not eliminate, racial disparities in health care, Dr. Chomilo said. The impact of Medicare and Medicaid is evident in the current COVID-19 pandemic, as county level data show that areas where more than 25% of the population are uninsured have higher rates of COVID-19 infections, said Dr. Chomilo. Policies that impact access to care also impact their incidence of chronic diseases and risk for severe disease, he noted.

“If you don’t have ready access to a health care provider, you don’t have access to the vaccine, and you don’t have information that would inform your getting the vaccine,” he added.

Prioritizing the power of voting

“Voting is one of many ways we can impact structural racism in health care policy,” Dr. Chomilo emphasized.

However, voting inequity remains a challenge, Dr. Chomilo noted. Community level disparities lead to inequity in voting access and subsequent disparities in voter participation, he said. “Leaders are less responsive to nonvoting constituents,” which can result in policies that impact health inequitably, and loop back to community level health disparities, he explained.

Historically, physicians have had an 8%-9% lower voter turnout than the general public, although this may have changed in recent elections, Dr. Chomilo said. He encouraged all clinicians to set an example and vote, and to empower their patients to vote. Evidence shows that enfranchisement of Black voters is associated with reductions in education gaps for Blacks and Whites, and that enfranchisement of women is associated with increased spending on children and lower child mortality, he said. Dr. Chomilo encouraged pediatricians and all clinicians to take advantage of the resources on voting available from the American Academy of Pediatrics (aap.org/votekids).

“When we see more people in a community vote, leaders are more responsive to their needs,” he said.

Informing racial identity

“Racial identity is informed by racial socialization,” Dr. Chomilo said. “All of us are socialized along the lines of race; it happens in conversations with parents, family, peers, community.” Another point in moving from awareness to action in eliminating structural racism is recognizing that children are not too young to talk about race, Dr. Chomilo emphasized.

Children start to navigate racial identity and to take note of other differences at an early age. For example, a 3-year-old might ask, “why does that person talk funny, why is that person being pushed in a chair?” Dr. Chomilo said, and it is important for parents and as pediatricians to be prepared for these questions, which are part of normal development. As children get older, they start to reflect on what differences mean for them, which is not rooted in anything negative, he noted.

Children first develop racial identity at home, but children solidify their identities in child care and school settings, Dr. Chomilo said. The American Academy of Pediatrics has acknowledged the potential for racial bias in education and child care, and said in a statement that, “it is critical for pediatricians to recognize the institutional personally mediated, and internalized levels of racism that occur in the educational setting, because education is a critical social determinant of health for children.” In fact, data from children in preschool show that they use racial categories to identify themselves and others, to include or exclude children from activities, and to negotiate power in their social and play networks.

Early intervention matters in educating children about racism, Dr. Chomilo said. “If we were not taught to talk about race, it is on us to learn about it ourselves as well,” he said.

Ultimately, the goal is to create active antiracism among adults and children, said Dr. Chomilo. He encouraged pediatricians and parents not to shut down or discourage children when they raise questions of race, but to take the opportunity to teach. “There may be hurt feelings around what a child said, even if they didn’t mean to offend someone,” he noted. Take the topic seriously, and make racism conversations ongoing; teach children to safely oppose negative messages and behaviors in others, and replace them with something positive, he emphasized.

Addressing bias in clinical settings

Dr. Chomilo also encouraged hospitalists to consider internalized racism in clinical settings and take action to build confidence and cultural pride in all patients by ensuring that a pediatric hospital unit is welcoming and representative of the diversity in a given community, with appropriate options for books, movies, and toys. He also encouraged pediatric hospitalists to assess children for experiences of racism as part of a social assessment. Be aware of signs of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, or grief that might have a racial component, he said.

Dr. Chomilo had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Structural racism and implicit bias are connected, and both must be addressed to move from awareness of racism to action, said Nathan Chomilo, MD, of HealthPartners/Park Nicollet, Brooklyn Center, Minn., in a presentation at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine annual conference.

“We need pediatricians with the courage to address racism head on,” he said.

One step in moving from awareness to action against structural and institutional racism in medicine is examining policies, Dr. Chomilo said. He cited the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 as examples of how policy changes can make a difference, illustrated by data from 1955-1975 that showed a significant decrease in infant deaths among Black infants in Mississippi after 1965.

Medicaid expansion has helped to narrow, but not eliminate, racial disparities in health care, Dr. Chomilo said. The impact of Medicare and Medicaid is evident in the current COVID-19 pandemic, as county level data show that areas where more than 25% of the population are uninsured have higher rates of COVID-19 infections, said Dr. Chomilo. Policies that impact access to care also impact their incidence of chronic diseases and risk for severe disease, he noted.

“If you don’t have ready access to a health care provider, you don’t have access to the vaccine, and you don’t have information that would inform your getting the vaccine,” he added.

Prioritizing the power of voting

“Voting is one of many ways we can impact structural racism in health care policy,” Dr. Chomilo emphasized.

However, voting inequity remains a challenge, Dr. Chomilo noted. Community level disparities lead to inequity in voting access and subsequent disparities in voter participation, he said. “Leaders are less responsive to nonvoting constituents,” which can result in policies that impact health inequitably, and loop back to community level health disparities, he explained.

Historically, physicians have had an 8%-9% lower voter turnout than the general public, although this may have changed in recent elections, Dr. Chomilo said. He encouraged all clinicians to set an example and vote, and to empower their patients to vote. Evidence shows that enfranchisement of Black voters is associated with reductions in education gaps for Blacks and Whites, and that enfranchisement of women is associated with increased spending on children and lower child mortality, he said. Dr. Chomilo encouraged pediatricians and all clinicians to take advantage of the resources on voting available from the American Academy of Pediatrics (aap.org/votekids).

“When we see more people in a community vote, leaders are more responsive to their needs,” he said.

Informing racial identity

“Racial identity is informed by racial socialization,” Dr. Chomilo said. “All of us are socialized along the lines of race; it happens in conversations with parents, family, peers, community.” Another point in moving from awareness to action in eliminating structural racism is recognizing that children are not too young to talk about race, Dr. Chomilo emphasized.

Children start to navigate racial identity and to take note of other differences at an early age. For example, a 3-year-old might ask, “why does that person talk funny, why is that person being pushed in a chair?” Dr. Chomilo said, and it is important for parents and as pediatricians to be prepared for these questions, which are part of normal development. As children get older, they start to reflect on what differences mean for them, which is not rooted in anything negative, he noted.

Children first develop racial identity at home, but children solidify their identities in child care and school settings, Dr. Chomilo said. The American Academy of Pediatrics has acknowledged the potential for racial bias in education and child care, and said in a statement that, “it is critical for pediatricians to recognize the institutional personally mediated, and internalized levels of racism that occur in the educational setting, because education is a critical social determinant of health for children.” In fact, data from children in preschool show that they use racial categories to identify themselves and others, to include or exclude children from activities, and to negotiate power in their social and play networks.

Early intervention matters in educating children about racism, Dr. Chomilo said. “If we were not taught to talk about race, it is on us to learn about it ourselves as well,” he said.

Ultimately, the goal is to create active antiracism among adults and children, said Dr. Chomilo. He encouraged pediatricians and parents not to shut down or discourage children when they raise questions of race, but to take the opportunity to teach. “There may be hurt feelings around what a child said, even if they didn’t mean to offend someone,” he noted. Take the topic seriously, and make racism conversations ongoing; teach children to safely oppose negative messages and behaviors in others, and replace them with something positive, he emphasized.

Addressing bias in clinical settings

Dr. Chomilo also encouraged hospitalists to consider internalized racism in clinical settings and take action to build confidence and cultural pride in all patients by ensuring that a pediatric hospital unit is welcoming and representative of the diversity in a given community, with appropriate options for books, movies, and toys. He also encouraged pediatric hospitalists to assess children for experiences of racism as part of a social assessment. Be aware of signs of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, or grief that might have a racial component, he said.

Dr. Chomilo had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PHM 2021

SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement to partner on NIH grant

The Society of Hospital Medicine has announced that its award-winning Center for Quality Improvement will partner on the National Institutes of Health National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute study, “The SIP Study: Simultaneously Implementing Pathways for Improving Asthma, Pneumonia, and Bronchiolitis Care for Hospitalized Children” (NIH R61HL157804). The core objectives of the planned 5-year study are to identify and test practical, sustainable strategies for implementing a multicondition clinical pathway intervention for children hospitalized with asthma, pneumonia, or bronchiolitis in community hospitals.

Under the leadership of principal investigator Sunitha Kaiser, MD, MSc, a pediatric hospitalist at the University of California, San Francisco, the study will employ rigorous implementation science methods and SHM’s mentored implementation model.

“The lessons learned from this study could inform improved care delivery strategies for the millions of children hospitalized with respiratory illnesses across the U.S. each year,” said Jenna Goldstein, chief of strategic partnerships at SHM and director of SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement.

The team will recruit a diverse group of community hospitals in partnership with SHM, the Value in Inpatient Pediatrics Network (within the American Academy of Pediatrics), the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network, America’s Hospital Essentials, and the National Improvement Partnership Network. In collaboration with these national organizations and the participating hospitals, the team seeks to realize the following aims:

- Aim 1. (Preimplementation) Identify barriers and facilitators of implementing a multicondition pathway intervention and refine the intervention for community hospitals.

- Aim 2a. Determine the effects of the intervention, compared with control via chart reviews of children hospitalized with asthma, pneumonia, or bronchiolitis.

- Aim 2b. Determine if the core implementation strategies (audit and feedback, electronic order sets, Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles) are associated with clinicians’ guideline adoption.

“SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement is a recognized partner in facilitating process and culture change in the hospital to improve outcomes for patients,” said Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of SHM. “SHM is committed to supporting quality-improvement research, and we look forward to contributing to improved care for hospitalized pediatric patients through this study and beyond.”

To learn more about SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement, visit hospitalmedicine.org/qi.

The Society of Hospital Medicine has announced that its award-winning Center for Quality Improvement will partner on the National Institutes of Health National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute study, “The SIP Study: Simultaneously Implementing Pathways for Improving Asthma, Pneumonia, and Bronchiolitis Care for Hospitalized Children” (NIH R61HL157804). The core objectives of the planned 5-year study are to identify and test practical, sustainable strategies for implementing a multicondition clinical pathway intervention for children hospitalized with asthma, pneumonia, or bronchiolitis in community hospitals.

Under the leadership of principal investigator Sunitha Kaiser, MD, MSc, a pediatric hospitalist at the University of California, San Francisco, the study will employ rigorous implementation science methods and SHM’s mentored implementation model.

“The lessons learned from this study could inform improved care delivery strategies for the millions of children hospitalized with respiratory illnesses across the U.S. each year,” said Jenna Goldstein, chief of strategic partnerships at SHM and director of SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement.

The team will recruit a diverse group of community hospitals in partnership with SHM, the Value in Inpatient Pediatrics Network (within the American Academy of Pediatrics), the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network, America’s Hospital Essentials, and the National Improvement Partnership Network. In collaboration with these national organizations and the participating hospitals, the team seeks to realize the following aims:

- Aim 1. (Preimplementation) Identify barriers and facilitators of implementing a multicondition pathway intervention and refine the intervention for community hospitals.

- Aim 2a. Determine the effects of the intervention, compared with control via chart reviews of children hospitalized with asthma, pneumonia, or bronchiolitis.

- Aim 2b. Determine if the core implementation strategies (audit and feedback, electronic order sets, Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles) are associated with clinicians’ guideline adoption.

“SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement is a recognized partner in facilitating process and culture change in the hospital to improve outcomes for patients,” said Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of SHM. “SHM is committed to supporting quality-improvement research, and we look forward to contributing to improved care for hospitalized pediatric patients through this study and beyond.”

To learn more about SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement, visit hospitalmedicine.org/qi.

The Society of Hospital Medicine has announced that its award-winning Center for Quality Improvement will partner on the National Institutes of Health National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute study, “The SIP Study: Simultaneously Implementing Pathways for Improving Asthma, Pneumonia, and Bronchiolitis Care for Hospitalized Children” (NIH R61HL157804). The core objectives of the planned 5-year study are to identify and test practical, sustainable strategies for implementing a multicondition clinical pathway intervention for children hospitalized with asthma, pneumonia, or bronchiolitis in community hospitals.

Under the leadership of principal investigator Sunitha Kaiser, MD, MSc, a pediatric hospitalist at the University of California, San Francisco, the study will employ rigorous implementation science methods and SHM’s mentored implementation model.

“The lessons learned from this study could inform improved care delivery strategies for the millions of children hospitalized with respiratory illnesses across the U.S. each year,” said Jenna Goldstein, chief of strategic partnerships at SHM and director of SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement.

The team will recruit a diverse group of community hospitals in partnership with SHM, the Value in Inpatient Pediatrics Network (within the American Academy of Pediatrics), the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network, America’s Hospital Essentials, and the National Improvement Partnership Network. In collaboration with these national organizations and the participating hospitals, the team seeks to realize the following aims:

- Aim 1. (Preimplementation) Identify barriers and facilitators of implementing a multicondition pathway intervention and refine the intervention for community hospitals.

- Aim 2a. Determine the effects of the intervention, compared with control via chart reviews of children hospitalized with asthma, pneumonia, or bronchiolitis.

- Aim 2b. Determine if the core implementation strategies (audit and feedback, electronic order sets, Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles) are associated with clinicians’ guideline adoption.

“SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement is a recognized partner in facilitating process and culture change in the hospital to improve outcomes for patients,” said Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of SHM. “SHM is committed to supporting quality-improvement research, and we look forward to contributing to improved care for hospitalized pediatric patients through this study and beyond.”

To learn more about SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement, visit hospitalmedicine.org/qi.

Febrile infant guideline allows wiggle room on hospital admission, testing

The long-anticipated American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for the treatment of well-appearing febrile infants have arrived, and key points include updated guidance for cerebrospinal fluid testing and urine cultures, according to Robert Pantell, MD, and Kenneth Roberts, MD, who presented the guidelines at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine annual conference.

The AAP guideline was published in the August 2021 issue of Pediatrics. The guideline includes 21 key action statements and 40 total recommendations, and describes separate management algorithms for three age groups: infants aged 8-21 days, 22-28 days, and 29-60 days.

Dr. Roberts, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Dr. Pantell, of the University of California, San Francisco, emphasized that all pediatricians should read the full guideline, but they offered an overview of some of the notable points.

Some changes that drove the development of evidence-based guideline included changes in technology, such as the increased use of procalcitonin, the development of large research networks for studies of sufficient size, and a need to reduce the costs of unnecessary care and unnecessary trauma for infants, Dr. Roberts said. Use of data from large networks such as the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network provided enough evidence to support dividing the aged 8- to 60-day population into three groups.

The guideline applies to well-appearing term infants aged 8-60 days and at least 37 weeks’ gestation, with fever of 38° C (100.4° F) or higher in the past 24 hours in the home or clinical setting. The decision to exclude infants in the first week of life from the guideline was because at this age, infants “are sufficiently different in rates and types of illness, including early-onset bacterial infection,” according to the authors.

Dr. Roberts emphasized that the guidelines apply to “well-appearing infants,” which is not always obvious. “If a clinician is not confident an infant is well appearing, the clinical practice guideline should not be applied,” he said.

The guideline also includes a visual algorithm for each age group.

Dr. Pantell summarized the key action statements for the three age groups, and encouraged pediatricians to review the visual algorithms and footnotes available in the full text of the guideline.

The guideline includes seven key action statements for each of the three age groups. Four of these address evaluations, using urine, blood culture, inflammatory markers (IM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). One action statement focuses on initial treatment, and two on management: hospital admission versus monitoring at home, and treatment cessation.

Infants aged 8-21 days

The key action statements for well-appearing infants aged 8-21 days are similar to what clinicians likely would do for ill-appearing infants, the authors noted, based in part on the challenge of assessing an infant this age as “well appearing,” because they don’t yet have the ability to interact with the clinician.

For the 8- to 21-day group, the first two key actions are to obtain a urine specimen and blood culture, Dr. Pantell said. Also, clinicians “should” obtain a CSF for analysis and culture. “We recognize that the ability to get CSF quickly is a challenge,” he added. However, for the 8- to 21-day age group, a new feature is that these infants may be discharged if the CSF is negative. Evaluation in this youngest group states that clinicians “may assess inflammatory markers” including height of fever, absolute neutrophil count, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin.

Treatment of infants in the 8- to 21-day group “should” include parenteral antimicrobial therapy, according to the guideline, and these infants “should” be actively monitored in the hospital by nurses and staff experienced in neonatal care, Dr. Pantell said. The guideline also includes a key action statement to stop antimicrobials at 24-36 hours if cultures are negative, but to treat identified organisms.

Infants aged 22-28 days

In both the 22- to 28-day-old and 29- to 60-day-old groups, the guideline offers opportunities for less testing and treatment, such as avoiding a lumbar puncture, and fewer hospitalizations. The development of a separate guideline for the 22- to 28-day group is something new, said Dr. Pantell. The guideline states that clinicians should obtain urine specimens and blood culture, and should assess IM in this group. Further key action statements note that clinicians “should obtain a CSF if any IM is positive,” but “may” obtain CSF if the infant is hospitalized, if blood and urine cultures have been obtained, and if none of the IMs are abnormal.

As with younger patients, those with a negative CSF can go home, he said. As for treatment, clinicians “should” administer parenteral antimicrobial therapy to infants managed at home even if they have a negative CSF and urinalysis (UA), and no abnormal inflammatory markers Other points for management of infants in this age group at home include verbal teaching and written instructions for caregivers, plans for a re-evaluation at home in 24 hours, and a plan for communication and access to emergency care in case of a change in clinical status, Dr. Pantell explained. The guideline states that infants “should” be hospitalized if CSF is either not obtained or not interpretable, which leaves room for clinical judgment and individual circumstances. Antimicrobials “should” be discontinued in this group once all cultures are negative after 24-36 hours and no other infection requires treatment.

Infants aged 29-60 days

For the 29- to 60-day group, there are some differences, the main one is the recommendation of blood cultures in this group, said Dr. Pantell. “We are seeing a lot of UTIs [urinary tract infections], and we would like those treated.” However, clinicians need not obtain a CSF if other IMs are normal, but may do so if any IM is abnormal. Antimicrobial therapy may include ceftriaxone or cephalexin for UTIs, or vancomycin for bacteremia.

Although antimicrobial therapy is an option for UTIs and bacterial meningitis, clinicians “need not” use antimicrobials if CSF is normal, if UA is negative, and if no IMs are abnormal, Dr. Pantell added. Overall, further management of infants in this oldest age group should focus on discharge to home in the absence of abnormal findings, but hospitalization in the presence of abnormal CSF, IMs, or other concerns.

During a question-and-answer session, Dr. Roberts said that, while rectal temperature is preferable, any method is acceptable as a starting point for applying the guideline. Importantly, the guideline still leaves room for clinical judgment. “We hope this will change some thinking as far as whether one model fits all,” he noted. The authors tried to temper the word “should” with the word “may” when possible, so clinicians can say: “I’m going to individualize my decision to the infant in front of me.”

Ultimately, the guideline is meant as a guide, and not an absolute standard of care, the authors said. The language of the key action statements includes the words “should, may, need not” in place of “must, must not.” The guideline recommends factoring family values and preferences into any treatment decisions. “Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.”

The guideline received no outside funding. The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The long-anticipated American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for the treatment of well-appearing febrile infants have arrived, and key points include updated guidance for cerebrospinal fluid testing and urine cultures, according to Robert Pantell, MD, and Kenneth Roberts, MD, who presented the guidelines at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine annual conference.

The AAP guideline was published in the August 2021 issue of Pediatrics. The guideline includes 21 key action statements and 40 total recommendations, and describes separate management algorithms for three age groups: infants aged 8-21 days, 22-28 days, and 29-60 days.

Dr. Roberts, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Dr. Pantell, of the University of California, San Francisco, emphasized that all pediatricians should read the full guideline, but they offered an overview of some of the notable points.

Some changes that drove the development of evidence-based guideline included changes in technology, such as the increased use of procalcitonin, the development of large research networks for studies of sufficient size, and a need to reduce the costs of unnecessary care and unnecessary trauma for infants, Dr. Roberts said. Use of data from large networks such as the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network provided enough evidence to support dividing the aged 8- to 60-day population into three groups.

The guideline applies to well-appearing term infants aged 8-60 days and at least 37 weeks’ gestation, with fever of 38° C (100.4° F) or higher in the past 24 hours in the home or clinical setting. The decision to exclude infants in the first week of life from the guideline was because at this age, infants “are sufficiently different in rates and types of illness, including early-onset bacterial infection,” according to the authors.

Dr. Roberts emphasized that the guidelines apply to “well-appearing infants,” which is not always obvious. “If a clinician is not confident an infant is well appearing, the clinical practice guideline should not be applied,” he said.

The guideline also includes a visual algorithm for each age group.

Dr. Pantell summarized the key action statements for the three age groups, and encouraged pediatricians to review the visual algorithms and footnotes available in the full text of the guideline.

The guideline includes seven key action statements for each of the three age groups. Four of these address evaluations, using urine, blood culture, inflammatory markers (IM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). One action statement focuses on initial treatment, and two on management: hospital admission versus monitoring at home, and treatment cessation.

Infants aged 8-21 days

The key action statements for well-appearing infants aged 8-21 days are similar to what clinicians likely would do for ill-appearing infants, the authors noted, based in part on the challenge of assessing an infant this age as “well appearing,” because they don’t yet have the ability to interact with the clinician.

For the 8- to 21-day group, the first two key actions are to obtain a urine specimen and blood culture, Dr. Pantell said. Also, clinicians “should” obtain a CSF for analysis and culture. “We recognize that the ability to get CSF quickly is a challenge,” he added. However, for the 8- to 21-day age group, a new feature is that these infants may be discharged if the CSF is negative. Evaluation in this youngest group states that clinicians “may assess inflammatory markers” including height of fever, absolute neutrophil count, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin.

Treatment of infants in the 8- to 21-day group “should” include parenteral antimicrobial therapy, according to the guideline, and these infants “should” be actively monitored in the hospital by nurses and staff experienced in neonatal care, Dr. Pantell said. The guideline also includes a key action statement to stop antimicrobials at 24-36 hours if cultures are negative, but to treat identified organisms.

Infants aged 22-28 days

In both the 22- to 28-day-old and 29- to 60-day-old groups, the guideline offers opportunities for less testing and treatment, such as avoiding a lumbar puncture, and fewer hospitalizations. The development of a separate guideline for the 22- to 28-day group is something new, said Dr. Pantell. The guideline states that clinicians should obtain urine specimens and blood culture, and should assess IM in this group. Further key action statements note that clinicians “should obtain a CSF if any IM is positive,” but “may” obtain CSF if the infant is hospitalized, if blood and urine cultures have been obtained, and if none of the IMs are abnormal.

As with younger patients, those with a negative CSF can go home, he said. As for treatment, clinicians “should” administer parenteral antimicrobial therapy to infants managed at home even if they have a negative CSF and urinalysis (UA), and no abnormal inflammatory markers Other points for management of infants in this age group at home include verbal teaching and written instructions for caregivers, plans for a re-evaluation at home in 24 hours, and a plan for communication and access to emergency care in case of a change in clinical status, Dr. Pantell explained. The guideline states that infants “should” be hospitalized if CSF is either not obtained or not interpretable, which leaves room for clinical judgment and individual circumstances. Antimicrobials “should” be discontinued in this group once all cultures are negative after 24-36 hours and no other infection requires treatment.

Infants aged 29-60 days

For the 29- to 60-day group, there are some differences, the main one is the recommendation of blood cultures in this group, said Dr. Pantell. “We are seeing a lot of UTIs [urinary tract infections], and we would like those treated.” However, clinicians need not obtain a CSF if other IMs are normal, but may do so if any IM is abnormal. Antimicrobial therapy may include ceftriaxone or cephalexin for UTIs, or vancomycin for bacteremia.

Although antimicrobial therapy is an option for UTIs and bacterial meningitis, clinicians “need not” use antimicrobials if CSF is normal, if UA is negative, and if no IMs are abnormal, Dr. Pantell added. Overall, further management of infants in this oldest age group should focus on discharge to home in the absence of abnormal findings, but hospitalization in the presence of abnormal CSF, IMs, or other concerns.

During a question-and-answer session, Dr. Roberts said that, while rectal temperature is preferable, any method is acceptable as a starting point for applying the guideline. Importantly, the guideline still leaves room for clinical judgment. “We hope this will change some thinking as far as whether one model fits all,” he noted. The authors tried to temper the word “should” with the word “may” when possible, so clinicians can say: “I’m going to individualize my decision to the infant in front of me.”

Ultimately, the guideline is meant as a guide, and not an absolute standard of care, the authors said. The language of the key action statements includes the words “should, may, need not” in place of “must, must not.” The guideline recommends factoring family values and preferences into any treatment decisions. “Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.”

The guideline received no outside funding. The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The long-anticipated American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for the treatment of well-appearing febrile infants have arrived, and key points include updated guidance for cerebrospinal fluid testing and urine cultures, according to Robert Pantell, MD, and Kenneth Roberts, MD, who presented the guidelines at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine annual conference.

The AAP guideline was published in the August 2021 issue of Pediatrics. The guideline includes 21 key action statements and 40 total recommendations, and describes separate management algorithms for three age groups: infants aged 8-21 days, 22-28 days, and 29-60 days.

Dr. Roberts, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Dr. Pantell, of the University of California, San Francisco, emphasized that all pediatricians should read the full guideline, but they offered an overview of some of the notable points.

Some changes that drove the development of evidence-based guideline included changes in technology, such as the increased use of procalcitonin, the development of large research networks for studies of sufficient size, and a need to reduce the costs of unnecessary care and unnecessary trauma for infants, Dr. Roberts said. Use of data from large networks such as the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network provided enough evidence to support dividing the aged 8- to 60-day population into three groups.

The guideline applies to well-appearing term infants aged 8-60 days and at least 37 weeks’ gestation, with fever of 38° C (100.4° F) or higher in the past 24 hours in the home or clinical setting. The decision to exclude infants in the first week of life from the guideline was because at this age, infants “are sufficiently different in rates and types of illness, including early-onset bacterial infection,” according to the authors.

Dr. Roberts emphasized that the guidelines apply to “well-appearing infants,” which is not always obvious. “If a clinician is not confident an infant is well appearing, the clinical practice guideline should not be applied,” he said.

The guideline also includes a visual algorithm for each age group.

Dr. Pantell summarized the key action statements for the three age groups, and encouraged pediatricians to review the visual algorithms and footnotes available in the full text of the guideline.

The guideline includes seven key action statements for each of the three age groups. Four of these address evaluations, using urine, blood culture, inflammatory markers (IM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). One action statement focuses on initial treatment, and two on management: hospital admission versus monitoring at home, and treatment cessation.

Infants aged 8-21 days

The key action statements for well-appearing infants aged 8-21 days are similar to what clinicians likely would do for ill-appearing infants, the authors noted, based in part on the challenge of assessing an infant this age as “well appearing,” because they don’t yet have the ability to interact with the clinician.

For the 8- to 21-day group, the first two key actions are to obtain a urine specimen and blood culture, Dr. Pantell said. Also, clinicians “should” obtain a CSF for analysis and culture. “We recognize that the ability to get CSF quickly is a challenge,” he added. However, for the 8- to 21-day age group, a new feature is that these infants may be discharged if the CSF is negative. Evaluation in this youngest group states that clinicians “may assess inflammatory markers” including height of fever, absolute neutrophil count, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin.

Treatment of infants in the 8- to 21-day group “should” include parenteral antimicrobial therapy, according to the guideline, and these infants “should” be actively monitored in the hospital by nurses and staff experienced in neonatal care, Dr. Pantell said. The guideline also includes a key action statement to stop antimicrobials at 24-36 hours if cultures are negative, but to treat identified organisms.

Infants aged 22-28 days

In both the 22- to 28-day-old and 29- to 60-day-old groups, the guideline offers opportunities for less testing and treatment, such as avoiding a lumbar puncture, and fewer hospitalizations. The development of a separate guideline for the 22- to 28-day group is something new, said Dr. Pantell. The guideline states that clinicians should obtain urine specimens and blood culture, and should assess IM in this group. Further key action statements note that clinicians “should obtain a CSF if any IM is positive,” but “may” obtain CSF if the infant is hospitalized, if blood and urine cultures have been obtained, and if none of the IMs are abnormal.

As with younger patients, those with a negative CSF can go home, he said. As for treatment, clinicians “should” administer parenteral antimicrobial therapy to infants managed at home even if they have a negative CSF and urinalysis (UA), and no abnormal inflammatory markers Other points for management of infants in this age group at home include verbal teaching and written instructions for caregivers, plans for a re-evaluation at home in 24 hours, and a plan for communication and access to emergency care in case of a change in clinical status, Dr. Pantell explained. The guideline states that infants “should” be hospitalized if CSF is either not obtained or not interpretable, which leaves room for clinical judgment and individual circumstances. Antimicrobials “should” be discontinued in this group once all cultures are negative after 24-36 hours and no other infection requires treatment.

Infants aged 29-60 days

For the 29- to 60-day group, there are some differences, the main one is the recommendation of blood cultures in this group, said Dr. Pantell. “We are seeing a lot of UTIs [urinary tract infections], and we would like those treated.” However, clinicians need not obtain a CSF if other IMs are normal, but may do so if any IM is abnormal. Antimicrobial therapy may include ceftriaxone or cephalexin for UTIs, or vancomycin for bacteremia.

Although antimicrobial therapy is an option for UTIs and bacterial meningitis, clinicians “need not” use antimicrobials if CSF is normal, if UA is negative, and if no IMs are abnormal, Dr. Pantell added. Overall, further management of infants in this oldest age group should focus on discharge to home in the absence of abnormal findings, but hospitalization in the presence of abnormal CSF, IMs, or other concerns.

During a question-and-answer session, Dr. Roberts said that, while rectal temperature is preferable, any method is acceptable as a starting point for applying the guideline. Importantly, the guideline still leaves room for clinical judgment. “We hope this will change some thinking as far as whether one model fits all,” he noted. The authors tried to temper the word “should” with the word “may” when possible, so clinicians can say: “I’m going to individualize my decision to the infant in front of me.”

Ultimately, the guideline is meant as a guide, and not an absolute standard of care, the authors said. The language of the key action statements includes the words “should, may, need not” in place of “must, must not.” The guideline recommends factoring family values and preferences into any treatment decisions. “Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.”

The guideline received no outside funding. The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PHM 2021

Hospitals struggle to find nurses, beds, even oxygen as Delta surges

The state of Mississippi is out of intensive care unit beds. The University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson – the state’s largest health system – is converting part of a parking garage into a field hospital to make more room.

“Hospitals are full from Memphis to Gulfport, Natchez to Meridian. Everything’s full,” said Alan Jones, MD, the hospital’s COVID-19 response leader, in a press briefing Aug. 11.

The state has requested the help of a federal disaster medical assistance team of physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and paramedics to staff the extra beds. The goal is to open the field hospital on Aug. 13.

Arkansas hospitals have as little as eight ICU beds left to serve a population of 3 million people. Alabama isn’t far behind.

As of Aug. 10, several large metro Atlanta hospitals were diverting patients because they were full.

Hospitals in Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, and Texas are canceling elective surgeries, as they are flooded with COVID patients.

Florida has ordered more ventilators from the federal government. Some hospitals in that state have so many patients on high-flow medical oxygen that it is taxing the building supply lines.

“Most hospitals were not designed for this type of volume distribution in their facilities,” said Mary Mayhew, president of the Florida Hospital Association.

That’s when they can get it. Oxygen deliveries have been disrupted because of a shortage of drivers who are trained to transport it.

“Any disruption in the timing of a delivery can be hugely problematic because of the volume of oxygen they’re going through,” Ms. Mayhew said.

Hospitals ‘under great stress’

Over the month of June, the number of COVID patients in Florida hospitals soared from 2,000 to 10,000. Ms. Mayhew says it took twice as long during the last surge for the state to reach those numbers. And they’re still climbing. The state had 15,000 hospitalized COVID patients as of Aug. 11.

COVID hospitalizations tripled in 3 weeks in South Carolina, said state epidemiologist Linda Bell, MD, in a news conference Aug. 11.

“These hospitals are under great stress,” says Eric Toner, MD, a senior scientist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore

The Delta variant has swept through the unvaccinated South with such veracity that hospitals in the region are unable to keep up. Patients with non-COVID health conditions are in jeopardy too.

Lee Owens, age 56, said he was supposed to have triple bypass surgery on Aug. 12 at St. Thomas West Hospital in Nashville, Tenn. Three of the arteries around his heart are 100%, 90%, and 70% blocked. Mr. Owens said the hospital called him Aug. 10 to postpone his surgery because they’ve cut back elective procedures to just one each day because the ICU beds there are full.

“I’m okay with having to wait a few days (my family isn’t!), especially if there are people worse than me, but so much anger at the reason,” he said. “These idiots that refused health care are now taking up my slot for heart surgery. It’s really aggravating.”

Anjali Bright, a spokesperson for St. Thomas West, provided a statement to this news organization saying they are not suspending elective procedures, but they are reviewing those “requiring an inpatient stay on a case-by-case basis.”

She emphasized, though, that “we will never delay care if the patient’s status changes to ‘urgent.’ ”

“Because of how infectious this variant is, this has the potential to be so much worse than what we saw in January,” said Donald Williamson, MD, president of the Alabama Hospital Association.

Dr. Williamson said they have modeled three possible scenarios for spread in the state, which ranks dead last in the United States for vaccination, with just 35% of its population fully protected. If the Delta variant spreads as it did in the United Kingdom, Alabama could see it hospitalize up to 3,000 people.

“That’s the best scenario,” he said.

If it sweeps through the state as it did in India, Alabama is looking at up to 4,500 patients hospitalized, a number that would require more beds and more staff to care for patients.

Then, there is what Dr. Williamson calls his “nightmare scenario.” If the entire state begins to see transmission rates as high as they’re currently seeing in coastal Mobile and Baldwin counties, that could mean up to 8,000 people in the hospital.

“If we see R-naughts of 5-8 statewide, we’re in real trouble,” he said. The R-naught is the basic rate of reproduction, and it means that each infected person would go on to infect 5-8 others. Dr. Williamson said the federal government would have to send them more staff to handle that kind of a surge.

‘Sense of betrayal’

Unlike the surges of last winter and spring, which sent hospitals scrambling for beds and supplies, the biggest pain point for hospitals now is staffing.

In Mississippi, where 200 patients are parked in emergency departments waiting for available and staffed ICU beds, the state is facing Delta with 2,000 fewer registered nurses than it had during its winter surge.

Some have left because of stress and burnout. Others have taken higher-paying jobs with travel nursing companies. To stop the exodus, hospitals are offering better pay, easier schedules, and sign-on and stay-on bonuses.

Doctors say the incentives are nice, but they don’t help with the anguish and anger many feel after months of battling COVID.

“There’s a big sense of betrayal,” said Sarah Nafziger, MD, vice president of clinical support services at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital. “Our staff and health care workers, in general, feel like we’ve been betrayed by the community.”

“We have a vaccine, which is the key to ending this pandemic and people just refuse to take it, and so I think we’re very frustrated. We feel that our communities have let us down by not taking advantage of the vaccine,” Dr. Nafziger said. “It’s just baffling to me and it’s broken my heart every single day.”

Dr. Nafziger said she met with several surgeons at UAB on Aug. 11 and began making decisions about which surgeries would need to be canceled the following week. “We’re talking about cancer surgery. We’re talking about heart surgery. We’re talking about things that are critical to people.”

Compounding the staffing problems, about half of hospital workers in Alabama are still unvaccinated. Dr. Williamson says they’re now starting to see these unvaccinated health care workers come down with COVID too. He says that will exacerbate their surge even further as health care workers become too sick to help care for patients and some will end up needing hospital beds themselves.

At the University of Mississippi Medical Center, 70 hospital employees and another 20 clinic employees are now being quarantined or have COVID, Dr. Jones said.

“The situation is bleak for Mississippi hospitals,” said Timothy Moore, president and CEO of the Mississippi Hospital Association. He said he doesn’t expect it to get better anytime soon.

Mississippi has more patients hospitalized now than at any other point in the pandemic, said Thomas Dobbs, MD, MPH, the state epidemiologist.

“If we look at the rapidity of this rise, it’s really kind of terrifying and awe-inspiring,” Dr. Dobbs said in a news conference Aug. 11.

Schools are just starting back, and, in many parts of the South, districts are operating under a patchwork of policies – some require masks, while others have made them voluntary. Physicians say they are bracing for what these half measures could mean for pediatric cases and community transmission.

The only sure way for people to help themselves and their hospitals and schools, experts said, is vaccination.

“State data show that in this latest COVID surge, 97% of new COVID-19 infections, 89% of hospitalizations, and 82% of deaths occur in unvaccinated residents,” Mr. Moore said.

“To relieve pressure on hospitals, we need Mississippians – even those who have previously had COVID – to get vaccinated and wear a mask in public. The Delta variant is highly contagious and we need to do all we can to stop the spread,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The state of Mississippi is out of intensive care unit beds. The University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson – the state’s largest health system – is converting part of a parking garage into a field hospital to make more room.

“Hospitals are full from Memphis to Gulfport, Natchez to Meridian. Everything’s full,” said Alan Jones, MD, the hospital’s COVID-19 response leader, in a press briefing Aug. 11.

The state has requested the help of a federal disaster medical assistance team of physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and paramedics to staff the extra beds. The goal is to open the field hospital on Aug. 13.

Arkansas hospitals have as little as eight ICU beds left to serve a population of 3 million people. Alabama isn’t far behind.

As of Aug. 10, several large metro Atlanta hospitals were diverting patients because they were full.

Hospitals in Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, and Texas are canceling elective surgeries, as they are flooded with COVID patients.

Florida has ordered more ventilators from the federal government. Some hospitals in that state have so many patients on high-flow medical oxygen that it is taxing the building supply lines.

“Most hospitals were not designed for this type of volume distribution in their facilities,” said Mary Mayhew, president of the Florida Hospital Association.

That’s when they can get it. Oxygen deliveries have been disrupted because of a shortage of drivers who are trained to transport it.

“Any disruption in the timing of a delivery can be hugely problematic because of the volume of oxygen they’re going through,” Ms. Mayhew said.

Hospitals ‘under great stress’

Over the month of June, the number of COVID patients in Florida hospitals soared from 2,000 to 10,000. Ms. Mayhew says it took twice as long during the last surge for the state to reach those numbers. And they’re still climbing. The state had 15,000 hospitalized COVID patients as of Aug. 11.

COVID hospitalizations tripled in 3 weeks in South Carolina, said state epidemiologist Linda Bell, MD, in a news conference Aug. 11.

“These hospitals are under great stress,” says Eric Toner, MD, a senior scientist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore

The Delta variant has swept through the unvaccinated South with such veracity that hospitals in the region are unable to keep up. Patients with non-COVID health conditions are in jeopardy too.

Lee Owens, age 56, said he was supposed to have triple bypass surgery on Aug. 12 at St. Thomas West Hospital in Nashville, Tenn. Three of the arteries around his heart are 100%, 90%, and 70% blocked. Mr. Owens said the hospital called him Aug. 10 to postpone his surgery because they’ve cut back elective procedures to just one each day because the ICU beds there are full.

“I’m okay with having to wait a few days (my family isn’t!), especially if there are people worse than me, but so much anger at the reason,” he said. “These idiots that refused health care are now taking up my slot for heart surgery. It’s really aggravating.”

Anjali Bright, a spokesperson for St. Thomas West, provided a statement to this news organization saying they are not suspending elective procedures, but they are reviewing those “requiring an inpatient stay on a case-by-case basis.”

She emphasized, though, that “we will never delay care if the patient’s status changes to ‘urgent.’ ”

“Because of how infectious this variant is, this has the potential to be so much worse than what we saw in January,” said Donald Williamson, MD, president of the Alabama Hospital Association.

Dr. Williamson said they have modeled three possible scenarios for spread in the state, which ranks dead last in the United States for vaccination, with just 35% of its population fully protected. If the Delta variant spreads as it did in the United Kingdom, Alabama could see it hospitalize up to 3,000 people.

“That’s the best scenario,” he said.

If it sweeps through the state as it did in India, Alabama is looking at up to 4,500 patients hospitalized, a number that would require more beds and more staff to care for patients.

Then, there is what Dr. Williamson calls his “nightmare scenario.” If the entire state begins to see transmission rates as high as they’re currently seeing in coastal Mobile and Baldwin counties, that could mean up to 8,000 people in the hospital.

“If we see R-naughts of 5-8 statewide, we’re in real trouble,” he said. The R-naught is the basic rate of reproduction, and it means that each infected person would go on to infect 5-8 others. Dr. Williamson said the federal government would have to send them more staff to handle that kind of a surge.

‘Sense of betrayal’

Unlike the surges of last winter and spring, which sent hospitals scrambling for beds and supplies, the biggest pain point for hospitals now is staffing.

In Mississippi, where 200 patients are parked in emergency departments waiting for available and staffed ICU beds, the state is facing Delta with 2,000 fewer registered nurses than it had during its winter surge.

Some have left because of stress and burnout. Others have taken higher-paying jobs with travel nursing companies. To stop the exodus, hospitals are offering better pay, easier schedules, and sign-on and stay-on bonuses.

Doctors say the incentives are nice, but they don’t help with the anguish and anger many feel after months of battling COVID.

“There’s a big sense of betrayal,” said Sarah Nafziger, MD, vice president of clinical support services at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital. “Our staff and health care workers, in general, feel like we’ve been betrayed by the community.”

“We have a vaccine, which is the key to ending this pandemic and people just refuse to take it, and so I think we’re very frustrated. We feel that our communities have let us down by not taking advantage of the vaccine,” Dr. Nafziger said. “It’s just baffling to me and it’s broken my heart every single day.”

Dr. Nafziger said she met with several surgeons at UAB on Aug. 11 and began making decisions about which surgeries would need to be canceled the following week. “We’re talking about cancer surgery. We’re talking about heart surgery. We’re talking about things that are critical to people.”

Compounding the staffing problems, about half of hospital workers in Alabama are still unvaccinated. Dr. Williamson says they’re now starting to see these unvaccinated health care workers come down with COVID too. He says that will exacerbate their surge even further as health care workers become too sick to help care for patients and some will end up needing hospital beds themselves.

At the University of Mississippi Medical Center, 70 hospital employees and another 20 clinic employees are now being quarantined or have COVID, Dr. Jones said.

“The situation is bleak for Mississippi hospitals,” said Timothy Moore, president and CEO of the Mississippi Hospital Association. He said he doesn’t expect it to get better anytime soon.

Mississippi has more patients hospitalized now than at any other point in the pandemic, said Thomas Dobbs, MD, MPH, the state epidemiologist.

“If we look at the rapidity of this rise, it’s really kind of terrifying and awe-inspiring,” Dr. Dobbs said in a news conference Aug. 11.

Schools are just starting back, and, in many parts of the South, districts are operating under a patchwork of policies – some require masks, while others have made them voluntary. Physicians say they are bracing for what these half measures could mean for pediatric cases and community transmission.

The only sure way for people to help themselves and their hospitals and schools, experts said, is vaccination.

“State data show that in this latest COVID surge, 97% of new COVID-19 infections, 89% of hospitalizations, and 82% of deaths occur in unvaccinated residents,” Mr. Moore said.

“To relieve pressure on hospitals, we need Mississippians – even those who have previously had COVID – to get vaccinated and wear a mask in public. The Delta variant is highly contagious and we need to do all we can to stop the spread,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The state of Mississippi is out of intensive care unit beds. The University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson – the state’s largest health system – is converting part of a parking garage into a field hospital to make more room.

“Hospitals are full from Memphis to Gulfport, Natchez to Meridian. Everything’s full,” said Alan Jones, MD, the hospital’s COVID-19 response leader, in a press briefing Aug. 11.

The state has requested the help of a federal disaster medical assistance team of physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and paramedics to staff the extra beds. The goal is to open the field hospital on Aug. 13.

Arkansas hospitals have as little as eight ICU beds left to serve a population of 3 million people. Alabama isn’t far behind.

As of Aug. 10, several large metro Atlanta hospitals were diverting patients because they were full.

Hospitals in Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, and Texas are canceling elective surgeries, as they are flooded with COVID patients.

Florida has ordered more ventilators from the federal government. Some hospitals in that state have so many patients on high-flow medical oxygen that it is taxing the building supply lines.

“Most hospitals were not designed for this type of volume distribution in their facilities,” said Mary Mayhew, president of the Florida Hospital Association.

That’s when they can get it. Oxygen deliveries have been disrupted because of a shortage of drivers who are trained to transport it.

“Any disruption in the timing of a delivery can be hugely problematic because of the volume of oxygen they’re going through,” Ms. Mayhew said.

Hospitals ‘under great stress’

Over the month of June, the number of COVID patients in Florida hospitals soared from 2,000 to 10,000. Ms. Mayhew says it took twice as long during the last surge for the state to reach those numbers. And they’re still climbing. The state had 15,000 hospitalized COVID patients as of Aug. 11.

COVID hospitalizations tripled in 3 weeks in South Carolina, said state epidemiologist Linda Bell, MD, in a news conference Aug. 11.

“These hospitals are under great stress,” says Eric Toner, MD, a senior scientist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore

The Delta variant has swept through the unvaccinated South with such veracity that hospitals in the region are unable to keep up. Patients with non-COVID health conditions are in jeopardy too.

Lee Owens, age 56, said he was supposed to have triple bypass surgery on Aug. 12 at St. Thomas West Hospital in Nashville, Tenn. Three of the arteries around his heart are 100%, 90%, and 70% blocked. Mr. Owens said the hospital called him Aug. 10 to postpone his surgery because they’ve cut back elective procedures to just one each day because the ICU beds there are full.

“I’m okay with having to wait a few days (my family isn’t!), especially if there are people worse than me, but so much anger at the reason,” he said. “These idiots that refused health care are now taking up my slot for heart surgery. It’s really aggravating.”

Anjali Bright, a spokesperson for St. Thomas West, provided a statement to this news organization saying they are not suspending elective procedures, but they are reviewing those “requiring an inpatient stay on a case-by-case basis.”

She emphasized, though, that “we will never delay care if the patient’s status changes to ‘urgent.’ ”

“Because of how infectious this variant is, this has the potential to be so much worse than what we saw in January,” said Donald Williamson, MD, president of the Alabama Hospital Association.

Dr. Williamson said they have modeled three possible scenarios for spread in the state, which ranks dead last in the United States for vaccination, with just 35% of its population fully protected. If the Delta variant spreads as it did in the United Kingdom, Alabama could see it hospitalize up to 3,000 people.

“That’s the best scenario,” he said.

If it sweeps through the state as it did in India, Alabama is looking at up to 4,500 patients hospitalized, a number that would require more beds and more staff to care for patients.

Then, there is what Dr. Williamson calls his “nightmare scenario.” If the entire state begins to see transmission rates as high as they’re currently seeing in coastal Mobile and Baldwin counties, that could mean up to 8,000 people in the hospital.

“If we see R-naughts of 5-8 statewide, we’re in real trouble,” he said. The R-naught is the basic rate of reproduction, and it means that each infected person would go on to infect 5-8 others. Dr. Williamson said the federal government would have to send them more staff to handle that kind of a surge.

‘Sense of betrayal’

Unlike the surges of last winter and spring, which sent hospitals scrambling for beds and supplies, the biggest pain point for hospitals now is staffing.

In Mississippi, where 200 patients are parked in emergency departments waiting for available and staffed ICU beds, the state is facing Delta with 2,000 fewer registered nurses than it had during its winter surge.

Some have left because of stress and burnout. Others have taken higher-paying jobs with travel nursing companies. To stop the exodus, hospitals are offering better pay, easier schedules, and sign-on and stay-on bonuses.

Doctors say the incentives are nice, but they don’t help with the anguish and anger many feel after months of battling COVID.

“There’s a big sense of betrayal,” said Sarah Nafziger, MD, vice president of clinical support services at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital. “Our staff and health care workers, in general, feel like we’ve been betrayed by the community.”

“We have a vaccine, which is the key to ending this pandemic and people just refuse to take it, and so I think we’re very frustrated. We feel that our communities have let us down by not taking advantage of the vaccine,” Dr. Nafziger said. “It’s just baffling to me and it’s broken my heart every single day.”

Dr. Nafziger said she met with several surgeons at UAB on Aug. 11 and began making decisions about which surgeries would need to be canceled the following week. “We’re talking about cancer surgery. We’re talking about heart surgery. We’re talking about things that are critical to people.”