User login

-

More guidance on inpatient management of blood glucose in COVID-19

“The glycemic management of many COVID-19–positive patients with diabetes is proving extremely complex, with huge fluctuations in glucose control and the need for very high doses of insulin,” says Diabetes UK’s National Diabetes Inpatient COVID Response Team.

“Intravenous infusion pumps, also required for inotropes, are at a premium and there may be the need to consider the use of subcutaneous or intramuscular insulin protocols,” they note.

Updated as of April 29, all of the information of the National Diabetes Inpatient COVID Response Team is available on the Diabetes UK website.

The new inpatient management graphic adds more detail to the previous “front-door” guidance, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The document stressed that, as well as identifying patients with known diabetes, it is imperative that all newly admitted patients with COVID-19 are evaluated for diabetes, as the infection is known to cause new-onset diabetes.

Subcutaneous insulin dosing

The new graphic gives extensive details on subcutaneous insulin dosing in place of variable rate intravenous insulin when infusion pumps are not available, and when the patient has a glucose level above 12 mmol/L (216 mg/dL) but does not have DKA or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state.

However, the advice is not intended for people with COVID-19 causing severe insulin resistance in the intensive care unit.

The other new guidance graphic on managing DKA or hyperosmolar state in people with COVID-19 using subcutaneous insulin is also intended for situations where intravenous infusion isn’t available.

Seek help from specialist diabetes team when needed

This is not to be used for mixed DKA/hyperosmolar state or for patients who are pregnant, have severe metabolic derangement, other significant comorbidity, or impaired consciousness, however.

For those situations, the advice is to seek help from a specialist diabetes team, says Diabetes UK.

Specialist teams will be available to answer diabetes queries, both by signposting to relevant existing local documents and also by providing patient-specific advice.

Indeed, NHS England recommends that such a team be available in every hospital, with a lead consultant designated each day to co-ordinate these services who must be free of other clinical duties when doing so. The role involves co-ordination of the whole service from the emergency department through to liaison with other specialties and managers.

Also newly updated is a page with extensive information for patients, including advice for staying at home, medication use, self-isolating, shielding, hospital and doctor appointments, need for urgent medical advice, and going to the hospital.

It also covers how coronavirus can affect people with diabetes, children and school, pregnancy, work situations, and tips for picking up prescriptions.

Another, shorter document with COVID-19 advice for patients has been posted by the JDRF and Beyond Type 1 Alliance.

It has also been endorsed by the American Diabetes Association, Harvard Medical School, and International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, in partnership with many other professional organizations, including the International Diabetes Federation, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists.

The shorter document covers topics such as personal hygiene, distancing, diabetes management, and seeking treatment, as well as links to other resources on what to do when health insurance is lost and legal rights.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“The glycemic management of many COVID-19–positive patients with diabetes is proving extremely complex, with huge fluctuations in glucose control and the need for very high doses of insulin,” says Diabetes UK’s National Diabetes Inpatient COVID Response Team.

“Intravenous infusion pumps, also required for inotropes, are at a premium and there may be the need to consider the use of subcutaneous or intramuscular insulin protocols,” they note.

Updated as of April 29, all of the information of the National Diabetes Inpatient COVID Response Team is available on the Diabetes UK website.

The new inpatient management graphic adds more detail to the previous “front-door” guidance, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The document stressed that, as well as identifying patients with known diabetes, it is imperative that all newly admitted patients with COVID-19 are evaluated for diabetes, as the infection is known to cause new-onset diabetes.

Subcutaneous insulin dosing

The new graphic gives extensive details on subcutaneous insulin dosing in place of variable rate intravenous insulin when infusion pumps are not available, and when the patient has a glucose level above 12 mmol/L (216 mg/dL) but does not have DKA or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state.

However, the advice is not intended for people with COVID-19 causing severe insulin resistance in the intensive care unit.

The other new guidance graphic on managing DKA or hyperosmolar state in people with COVID-19 using subcutaneous insulin is also intended for situations where intravenous infusion isn’t available.

Seek help from specialist diabetes team when needed

This is not to be used for mixed DKA/hyperosmolar state or for patients who are pregnant, have severe metabolic derangement, other significant comorbidity, or impaired consciousness, however.

For those situations, the advice is to seek help from a specialist diabetes team, says Diabetes UK.

Specialist teams will be available to answer diabetes queries, both by signposting to relevant existing local documents and also by providing patient-specific advice.

Indeed, NHS England recommends that such a team be available in every hospital, with a lead consultant designated each day to co-ordinate these services who must be free of other clinical duties when doing so. The role involves co-ordination of the whole service from the emergency department through to liaison with other specialties and managers.

Also newly updated is a page with extensive information for patients, including advice for staying at home, medication use, self-isolating, shielding, hospital and doctor appointments, need for urgent medical advice, and going to the hospital.

It also covers how coronavirus can affect people with diabetes, children and school, pregnancy, work situations, and tips for picking up prescriptions.

Another, shorter document with COVID-19 advice for patients has been posted by the JDRF and Beyond Type 1 Alliance.

It has also been endorsed by the American Diabetes Association, Harvard Medical School, and International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, in partnership with many other professional organizations, including the International Diabetes Federation, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists.

The shorter document covers topics such as personal hygiene, distancing, diabetes management, and seeking treatment, as well as links to other resources on what to do when health insurance is lost and legal rights.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“The glycemic management of many COVID-19–positive patients with diabetes is proving extremely complex, with huge fluctuations in glucose control and the need for very high doses of insulin,” says Diabetes UK’s National Diabetes Inpatient COVID Response Team.

“Intravenous infusion pumps, also required for inotropes, are at a premium and there may be the need to consider the use of subcutaneous or intramuscular insulin protocols,” they note.

Updated as of April 29, all of the information of the National Diabetes Inpatient COVID Response Team is available on the Diabetes UK website.

The new inpatient management graphic adds more detail to the previous “front-door” guidance, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The document stressed that, as well as identifying patients with known diabetes, it is imperative that all newly admitted patients with COVID-19 are evaluated for diabetes, as the infection is known to cause new-onset diabetes.

Subcutaneous insulin dosing

The new graphic gives extensive details on subcutaneous insulin dosing in place of variable rate intravenous insulin when infusion pumps are not available, and when the patient has a glucose level above 12 mmol/L (216 mg/dL) but does not have DKA or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state.

However, the advice is not intended for people with COVID-19 causing severe insulin resistance in the intensive care unit.

The other new guidance graphic on managing DKA or hyperosmolar state in people with COVID-19 using subcutaneous insulin is also intended for situations where intravenous infusion isn’t available.

Seek help from specialist diabetes team when needed

This is not to be used for mixed DKA/hyperosmolar state or for patients who are pregnant, have severe metabolic derangement, other significant comorbidity, or impaired consciousness, however.

For those situations, the advice is to seek help from a specialist diabetes team, says Diabetes UK.

Specialist teams will be available to answer diabetes queries, both by signposting to relevant existing local documents and also by providing patient-specific advice.

Indeed, NHS England recommends that such a team be available in every hospital, with a lead consultant designated each day to co-ordinate these services who must be free of other clinical duties when doing so. The role involves co-ordination of the whole service from the emergency department through to liaison with other specialties and managers.

Also newly updated is a page with extensive information for patients, including advice for staying at home, medication use, self-isolating, shielding, hospital and doctor appointments, need for urgent medical advice, and going to the hospital.

It also covers how coronavirus can affect people with diabetes, children and school, pregnancy, work situations, and tips for picking up prescriptions.

Another, shorter document with COVID-19 advice for patients has been posted by the JDRF and Beyond Type 1 Alliance.

It has also been endorsed by the American Diabetes Association, Harvard Medical School, and International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, in partnership with many other professional organizations, including the International Diabetes Federation, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists.

The shorter document covers topics such as personal hygiene, distancing, diabetes management, and seeking treatment, as well as links to other resources on what to do when health insurance is lost and legal rights.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results from 11 AHA-funded COVID-19 studies expected within months

Work is set to start in June, with findings reported in as few as 6 months. The Cleveland Clinic will coordinate the efforts, collecting and disseminating the findings.

There were more than 750 research proposals in less than a month after the association announced its COVID-19 and Its Cardiovascular Impact Rapid Response Grant initiative.

“We were just blown away and so impressed to see this level of interest and commitment from the teams submitting such thorough proposals so quickly,” AHA President Robert Harrington, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in a press statement. “There’s so much we don’t know about this unique coronavirus, and we continue to see emerging complications affecting both heart and brain health for which we desperately need answers and we need them quickly.”

The projects include the following:

- A Comprehensive Assessment of Arterial and Venous Thrombotic Complications in Patients with COVID-19, led by Columbia University, New York City.

- Repurposing Drugs for Treatment of Cardiomyopathy Caused by Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), led by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

- Risk of Severe Morbidity and Mortality of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Among Patients Taking Antihypertensive Medications, led by Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

- Deep Learning Using Chest Radiographs to Predict COVID-19 Cardiopulmonary Risk, led by Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

- Cardiovascular Outcomes and Biomarker Titrated Corticosteroid Dosing for SARS COV-2 (COVID-19): A Randomized Controlled Trial, led by the Mayo Clinic, Rochester Minn.

- Outcomes for Patients With Hypertension, Diabetes, and Heart Disease in the Coronavirus Pandemic: Impact of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers Treatment, led by Stanford University.

- Rapid COVID-19-on-A-Chip to Screen Competitive Targets for SARS-CoV-2 Spike Binding Sites, led by University of California, Los Angeles.

- COVID-19 Infection, African American Women and Cardiovascular Health, led by University of California, San Francisco.

- Myocardial Virus and Gene Expression in SARS CoV-2 Positive Patients with Clinically Important Myocardial Dysfunction, led by the University of Colorado, Aurora.

- The Role of the Platelet in Mediating Cardiovascular Disease in SARS-CoV-2 Infection, led by the University of Massachusetts, Worcester.

- Harnessing Glycomics to Understand Myocardial Injury in COVID-19, led by the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha.

The AHA also awarded $800,000 for short-term projects to members of its new Health Technologies & Innovation Strategically Focused Research Network.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital will assess the use of ejection fraction to triage COVID-19 patients; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, will assess smartphones for “virtual check-in” for stroke symptoms; Stanford will assess digital tracking of COVID-19 patients with cardiovascular complications; and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, will assess a system to track physiological and cardiovascular consequences of the infection.

Work is set to start in June, with findings reported in as few as 6 months. The Cleveland Clinic will coordinate the efforts, collecting and disseminating the findings.

There were more than 750 research proposals in less than a month after the association announced its COVID-19 and Its Cardiovascular Impact Rapid Response Grant initiative.

“We were just blown away and so impressed to see this level of interest and commitment from the teams submitting such thorough proposals so quickly,” AHA President Robert Harrington, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in a press statement. “There’s so much we don’t know about this unique coronavirus, and we continue to see emerging complications affecting both heart and brain health for which we desperately need answers and we need them quickly.”

The projects include the following:

- A Comprehensive Assessment of Arterial and Venous Thrombotic Complications in Patients with COVID-19, led by Columbia University, New York City.

- Repurposing Drugs for Treatment of Cardiomyopathy Caused by Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), led by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

- Risk of Severe Morbidity and Mortality of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Among Patients Taking Antihypertensive Medications, led by Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

- Deep Learning Using Chest Radiographs to Predict COVID-19 Cardiopulmonary Risk, led by Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

- Cardiovascular Outcomes and Biomarker Titrated Corticosteroid Dosing for SARS COV-2 (COVID-19): A Randomized Controlled Trial, led by the Mayo Clinic, Rochester Minn.

- Outcomes for Patients With Hypertension, Diabetes, and Heart Disease in the Coronavirus Pandemic: Impact of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers Treatment, led by Stanford University.

- Rapid COVID-19-on-A-Chip to Screen Competitive Targets for SARS-CoV-2 Spike Binding Sites, led by University of California, Los Angeles.

- COVID-19 Infection, African American Women and Cardiovascular Health, led by University of California, San Francisco.

- Myocardial Virus and Gene Expression in SARS CoV-2 Positive Patients with Clinically Important Myocardial Dysfunction, led by the University of Colorado, Aurora.

- The Role of the Platelet in Mediating Cardiovascular Disease in SARS-CoV-2 Infection, led by the University of Massachusetts, Worcester.

- Harnessing Glycomics to Understand Myocardial Injury in COVID-19, led by the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha.

The AHA also awarded $800,000 for short-term projects to members of its new Health Technologies & Innovation Strategically Focused Research Network.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital will assess the use of ejection fraction to triage COVID-19 patients; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, will assess smartphones for “virtual check-in” for stroke symptoms; Stanford will assess digital tracking of COVID-19 patients with cardiovascular complications; and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, will assess a system to track physiological and cardiovascular consequences of the infection.

Work is set to start in June, with findings reported in as few as 6 months. The Cleveland Clinic will coordinate the efforts, collecting and disseminating the findings.

There were more than 750 research proposals in less than a month after the association announced its COVID-19 and Its Cardiovascular Impact Rapid Response Grant initiative.

“We were just blown away and so impressed to see this level of interest and commitment from the teams submitting such thorough proposals so quickly,” AHA President Robert Harrington, MD, chair of the department of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in a press statement. “There’s so much we don’t know about this unique coronavirus, and we continue to see emerging complications affecting both heart and brain health for which we desperately need answers and we need them quickly.”

The projects include the following:

- A Comprehensive Assessment of Arterial and Venous Thrombotic Complications in Patients with COVID-19, led by Columbia University, New York City.

- Repurposing Drugs for Treatment of Cardiomyopathy Caused by Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), led by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

- Risk of Severe Morbidity and Mortality of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Among Patients Taking Antihypertensive Medications, led by Kaiser Permanente Southern California.

- Deep Learning Using Chest Radiographs to Predict COVID-19 Cardiopulmonary Risk, led by Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

- Cardiovascular Outcomes and Biomarker Titrated Corticosteroid Dosing for SARS COV-2 (COVID-19): A Randomized Controlled Trial, led by the Mayo Clinic, Rochester Minn.

- Outcomes for Patients With Hypertension, Diabetes, and Heart Disease in the Coronavirus Pandemic: Impact of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers Treatment, led by Stanford University.

- Rapid COVID-19-on-A-Chip to Screen Competitive Targets for SARS-CoV-2 Spike Binding Sites, led by University of California, Los Angeles.

- COVID-19 Infection, African American Women and Cardiovascular Health, led by University of California, San Francisco.

- Myocardial Virus and Gene Expression in SARS CoV-2 Positive Patients with Clinically Important Myocardial Dysfunction, led by the University of Colorado, Aurora.

- The Role of the Platelet in Mediating Cardiovascular Disease in SARS-CoV-2 Infection, led by the University of Massachusetts, Worcester.

- Harnessing Glycomics to Understand Myocardial Injury in COVID-19, led by the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha.

The AHA also awarded $800,000 for short-term projects to members of its new Health Technologies & Innovation Strategically Focused Research Network.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital will assess the use of ejection fraction to triage COVID-19 patients; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, will assess smartphones for “virtual check-in” for stroke symptoms; Stanford will assess digital tracking of COVID-19 patients with cardiovascular complications; and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, will assess a system to track physiological and cardiovascular consequences of the infection.

COVID-19–associated coagulopathy

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a viral illness caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), currently causing a pandemic affecting many countries around the world, beginning in December 2019 and spreading rapidly on a global scale since. Globally, its burden has been increasing rapidly, with more than 1.2 million people testing positive for the illness and 123,000 people losing their lives, as per April 15th’s WHO COVID-19 Situation Report.1 These numbers are increasing with each passing day. Clinically, SARS-CoV-2 has a highly variable course, ranging from mild disease manifested as a self-limited illness (seen in younger and healthier patients) to severe pneumonia/ARDS and multiorgan failure with intravascular coagulopathy.2

In this article, we intend to investigate and establish a comprehensive review of COVID-19–associated coagulopathy mechanisms, laboratory findings, and current management guidelines put forth by various societies globally.

Mechanism of coagulopathy

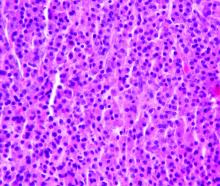

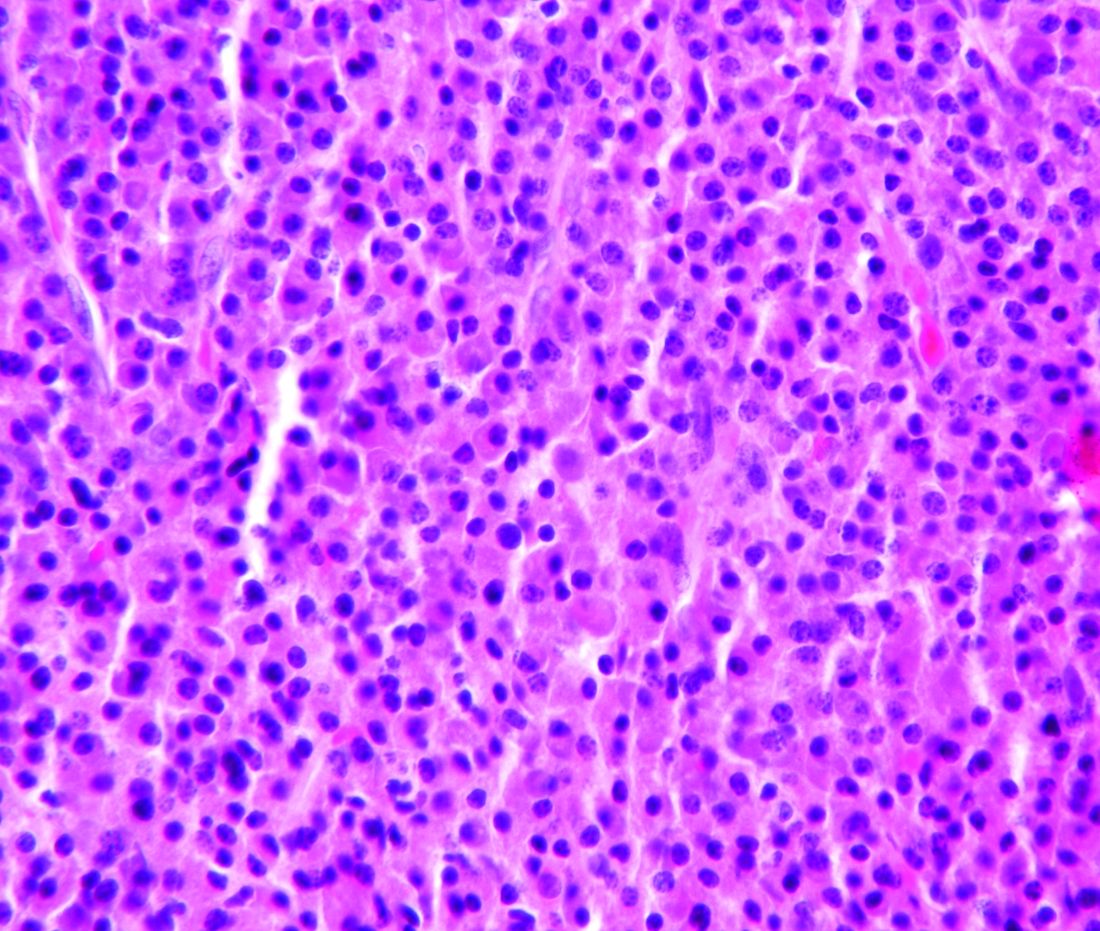

COVID-19–associated coagulopathy has been shown to predispose to both arterial and venous thrombosis through excessive inflammation and hypoxia, leading to activation of the coagulation cascade and consumption of coagulation factors, resulting in microvascular thrombosis.3 Though the exact pathophysiology for the activation of this cascade is not known, the proposed mechanism has been: endothelial damage triggering platelet activation within the lung, leading to aggregation, thrombosis, and consumption of platelets in the lung.2,5,6

Fox et al. noted similar coagulopathy findings of four deceased COVID-19 patients. Autopsy results concluded that the dominant process was diffuse alveolar damage, notable CD4+ aggregates around thrombosed small vessels, significant associated hemorrhage, and thrombotic microangiopathy restricted to the lungs. The proposed mechanism was the activation of megakaryocytes, possibly native to the lung, with platelet aggregation, formation of platelet-rich clots, and fibrin deposition playing a major role.4

It has been noted that diabetic patients are at an increased risk of vascular events and hypercoagulability with COVID-19.7 COVID-19 can also cause livedo reticularis and acrocyanosis because of the microthrombosis in the cutaneous vasculature secondary to underlying coagulopathy, as reported in a case report of two U.S. patients with COVID-19.8

Clinical and laboratory abnormalities

A recent study reported from Netherlands by Klok et al. analyzed 184 ICU patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and concluded that the cumulative incidence of acute pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), ischemic stroke, MI, or systemic arterial embolism was 31% (95% confidence interval, 20%-41%). PE was the most frequent thrombotic complication and was noted in 81% of patients. Coagulopathy, defined as spontaneous prolongation of prothrombin time (PT) > 3s or activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) > 5s, was reported as an independent predictor of thrombotic complications.3

Hematologic abnormalities that were noted in COVID-19 coagulopathy include: decreased platelet counts, decreased fibrinogen levels, elevated PT/INR, elevated partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and elevated d-dimer.9,10 In a retrospective analysis9 by Tang et al., 71.4% of nonsurvivors and 0.6% of survivors had met the criteria of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) during their hospital stay. Nonsurvivors of COVID-19 had statistically significant elevation of d-dimer levels, FDP levels, PT, and aPTT, when compared to survivors (P < .05). The overall mortality in this study was reported as 11.5%.9 In addition, elevated d-dimer, fibrin and fibrinogen degradation product (FDP) levels and longer PT and aPTT were associated with poor prognosis.

Thus, d-dimer, PT, and platelet count should be measured in all patients who present with COVID-19 infection. We can also suggest that in patients with markedly elevated d-dimer (three- to fourfold increase), admission to hospital should be considered even in the absence of severe clinical symptoms.11

COVID-19 coagulopathy management

In a retrospective study9 of 449 patients with severe COVID-19 from Wuhan, China, by Tang et al., 99 patients mainly received low-weight molecular heparin (LMWH) for 7 days or longer. No difference in 28-day mortality was noted between heparin users and nonusers (30.3% vs. 29.7%; P = .910). A lower 28-day mortality rate was noted in heparin patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy score of ≥4.0 (40.0% vs. 64.2%; P = .029) or a d-dimer level greater than sixfold of upper limit of normal, compared with nonusers of heparin.12

Another small study of seven COVID-19 patients with acroischemia in China demonstrated that administering LMWH was successful at decreasing the d-dimer and fibrinogen degradation product levels but noted no significant improvement in clinical symptoms.13

Recently, the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis and American Society of Hematology published recommendations and guidelines regarding the recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19.11 Prophylactic anticoagulation therapy with LMWH was recommended in all hospitalized patients with COVID-19, provided there was an absence of any contraindications (active bleeding, platelet count less than 25 x 109/L and fibrinogen less than 0.5 g/dL). Anticoagulation with LMWH was associated with better prognosis in severe COVID-19 patients and in COVID-19 patients with markedly elevated d-dimer, as it also has anti-inflammatory effects.12 This anti-inflammatory property of heparin has been documented in previous studies but the underlying mechanism is unknown and more research is required.14,15

Despite coagulopathy being noticed with cases of COVID-19, bleeding has been a rare finding in COVID-19 infections. If bleeding is noted, recommendations were made to keep platelet levels greater than 50 x109/L, fibrinogen less than 2.0 g/L, and INR [international normalized ratio] greater than 1.5.11 Mechanical thromboprophylaxis should be used when pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis is contraindicated.16

COVID-19 patients with new diagnoses of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or atrial fibrillation should be prescribed therapeutic anticoagulation. Patients who are already on anticoagulation for VTE or atrial fibrillation should continue their therapy unless the platelet count is less than 30-50x109/L or if the fibrinogen is less than 1.0 g/L.16

Conclusion

Coagulopathies associated with COVID-19 infections have been documented in several studies around the world, and it has been shown to be fatal in some cases. Despite documentation, the mechanism behind this coagulopathy is not well understood. Because of the potentially lethal complications associated with coagulopathies, early recognition and anticoagulation is imperative to improve clinical outcomes. These results are very preliminary: More studies are required to understand the role of anticoagulation and its effect on the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19–associated coagulopathy.

Dr. Yeruva is a board-certified hematologist/medical oncologist with WellSpan Health and clinical assistant professor of internal medicine, Penn State University, Hershey. Mr. Henderson is a third-year graduate-entry medical student at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland with interests in family medicine, dermatology, and tropical diseases. Dr. Al-Tawfiq is a consultant of internal medicine & infectious diseases, and the director of quality at Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, an adjunct associate professor of infectious diseases, molecular medicine and clinical pharmacology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and adjunct associate professor at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis. Dr. Tirupathi is the medical director of Keystone Infectious Diseases/HIV in Chambersburg, Pa., and currently chair of infection prevention at Wellspan Chambersburg and Waynesboro (Pa.) Hospitals. He also is the lead physician for antibiotic stewardship at these hospitals.

References

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports.

2. Lippi G et al. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: A meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020 Mar 13. 506:145-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022.

3. Klok FA et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Throm Res. 2020;18(4):844-7. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013.

4. Fox S et al. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in Covid-19: The first autopsy series from New Orleans. MedRxiv. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.06.20050575.

5. Yang M et al. Thrombocytopenia in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (review). Hematology 2013 Sep 4. doi: 10.1080/1024533040002617.

6. Giannis D et al. Coagulation disorders in coronavirus infected patients: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and lessons from the past. J Clin Virol. 2020 June. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104362.

7. Guo W et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020 Mar 31. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3319.

8. Manalo IF et al. A dermatologic manifestation of COVID-19: Transient livedo reticularis. J Am Acad Dermat. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.018.

9. Tang N et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768, 18: 844-847.

10. Huang C et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

11. Thachil J et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Mar 25. doi: 10.1111/JTH.14810.

12. Tang N et al. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1111/JTH.14817.

13. Zhang Y et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-2019 pneumonia and acro-ischemia. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020 Mar 28. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2020.0006.

14. Poterucha TJ et al. More than an anticoagulant: Do heparins have direct anti-inflammatory effects? Thromb Haemost. 2017. doi: 10.1160/TH16-08-0620.

15. Mousavi S et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of heparin and its derivatives: A systematic review. Adv Pharmacol Pharm Sci. 2015 May 12. doi: 10.1155/2015/507151.

16. Kreuziger L et al. COVID-19 and VTE/anticoagulation: Frequently asked questions. American Society of Hematology. 2020 Apr 17.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a viral illness caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), currently causing a pandemic affecting many countries around the world, beginning in December 2019 and spreading rapidly on a global scale since. Globally, its burden has been increasing rapidly, with more than 1.2 million people testing positive for the illness and 123,000 people losing their lives, as per April 15th’s WHO COVID-19 Situation Report.1 These numbers are increasing with each passing day. Clinically, SARS-CoV-2 has a highly variable course, ranging from mild disease manifested as a self-limited illness (seen in younger and healthier patients) to severe pneumonia/ARDS and multiorgan failure with intravascular coagulopathy.2

In this article, we intend to investigate and establish a comprehensive review of COVID-19–associated coagulopathy mechanisms, laboratory findings, and current management guidelines put forth by various societies globally.

Mechanism of coagulopathy

COVID-19–associated coagulopathy has been shown to predispose to both arterial and venous thrombosis through excessive inflammation and hypoxia, leading to activation of the coagulation cascade and consumption of coagulation factors, resulting in microvascular thrombosis.3 Though the exact pathophysiology for the activation of this cascade is not known, the proposed mechanism has been: endothelial damage triggering platelet activation within the lung, leading to aggregation, thrombosis, and consumption of platelets in the lung.2,5,6

Fox et al. noted similar coagulopathy findings of four deceased COVID-19 patients. Autopsy results concluded that the dominant process was diffuse alveolar damage, notable CD4+ aggregates around thrombosed small vessels, significant associated hemorrhage, and thrombotic microangiopathy restricted to the lungs. The proposed mechanism was the activation of megakaryocytes, possibly native to the lung, with platelet aggregation, formation of platelet-rich clots, and fibrin deposition playing a major role.4

It has been noted that diabetic patients are at an increased risk of vascular events and hypercoagulability with COVID-19.7 COVID-19 can also cause livedo reticularis and acrocyanosis because of the microthrombosis in the cutaneous vasculature secondary to underlying coagulopathy, as reported in a case report of two U.S. patients with COVID-19.8

Clinical and laboratory abnormalities

A recent study reported from Netherlands by Klok et al. analyzed 184 ICU patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and concluded that the cumulative incidence of acute pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), ischemic stroke, MI, or systemic arterial embolism was 31% (95% confidence interval, 20%-41%). PE was the most frequent thrombotic complication and was noted in 81% of patients. Coagulopathy, defined as spontaneous prolongation of prothrombin time (PT) > 3s or activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) > 5s, was reported as an independent predictor of thrombotic complications.3

Hematologic abnormalities that were noted in COVID-19 coagulopathy include: decreased platelet counts, decreased fibrinogen levels, elevated PT/INR, elevated partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and elevated d-dimer.9,10 In a retrospective analysis9 by Tang et al., 71.4% of nonsurvivors and 0.6% of survivors had met the criteria of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) during their hospital stay. Nonsurvivors of COVID-19 had statistically significant elevation of d-dimer levels, FDP levels, PT, and aPTT, when compared to survivors (P < .05). The overall mortality in this study was reported as 11.5%.9 In addition, elevated d-dimer, fibrin and fibrinogen degradation product (FDP) levels and longer PT and aPTT were associated with poor prognosis.

Thus, d-dimer, PT, and platelet count should be measured in all patients who present with COVID-19 infection. We can also suggest that in patients with markedly elevated d-dimer (three- to fourfold increase), admission to hospital should be considered even in the absence of severe clinical symptoms.11

COVID-19 coagulopathy management

In a retrospective study9 of 449 patients with severe COVID-19 from Wuhan, China, by Tang et al., 99 patients mainly received low-weight molecular heparin (LMWH) for 7 days or longer. No difference in 28-day mortality was noted between heparin users and nonusers (30.3% vs. 29.7%; P = .910). A lower 28-day mortality rate was noted in heparin patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy score of ≥4.0 (40.0% vs. 64.2%; P = .029) or a d-dimer level greater than sixfold of upper limit of normal, compared with nonusers of heparin.12

Another small study of seven COVID-19 patients with acroischemia in China demonstrated that administering LMWH was successful at decreasing the d-dimer and fibrinogen degradation product levels but noted no significant improvement in clinical symptoms.13

Recently, the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis and American Society of Hematology published recommendations and guidelines regarding the recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19.11 Prophylactic anticoagulation therapy with LMWH was recommended in all hospitalized patients with COVID-19, provided there was an absence of any contraindications (active bleeding, platelet count less than 25 x 109/L and fibrinogen less than 0.5 g/dL). Anticoagulation with LMWH was associated with better prognosis in severe COVID-19 patients and in COVID-19 patients with markedly elevated d-dimer, as it also has anti-inflammatory effects.12 This anti-inflammatory property of heparin has been documented in previous studies but the underlying mechanism is unknown and more research is required.14,15

Despite coagulopathy being noticed with cases of COVID-19, bleeding has been a rare finding in COVID-19 infections. If bleeding is noted, recommendations were made to keep platelet levels greater than 50 x109/L, fibrinogen less than 2.0 g/L, and INR [international normalized ratio] greater than 1.5.11 Mechanical thromboprophylaxis should be used when pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis is contraindicated.16

COVID-19 patients with new diagnoses of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or atrial fibrillation should be prescribed therapeutic anticoagulation. Patients who are already on anticoagulation for VTE or atrial fibrillation should continue their therapy unless the platelet count is less than 30-50x109/L or if the fibrinogen is less than 1.0 g/L.16

Conclusion

Coagulopathies associated with COVID-19 infections have been documented in several studies around the world, and it has been shown to be fatal in some cases. Despite documentation, the mechanism behind this coagulopathy is not well understood. Because of the potentially lethal complications associated with coagulopathies, early recognition and anticoagulation is imperative to improve clinical outcomes. These results are very preliminary: More studies are required to understand the role of anticoagulation and its effect on the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19–associated coagulopathy.

Dr. Yeruva is a board-certified hematologist/medical oncologist with WellSpan Health and clinical assistant professor of internal medicine, Penn State University, Hershey. Mr. Henderson is a third-year graduate-entry medical student at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland with interests in family medicine, dermatology, and tropical diseases. Dr. Al-Tawfiq is a consultant of internal medicine & infectious diseases, and the director of quality at Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, an adjunct associate professor of infectious diseases, molecular medicine and clinical pharmacology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and adjunct associate professor at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis. Dr. Tirupathi is the medical director of Keystone Infectious Diseases/HIV in Chambersburg, Pa., and currently chair of infection prevention at Wellspan Chambersburg and Waynesboro (Pa.) Hospitals. He also is the lead physician for antibiotic stewardship at these hospitals.

References

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports.

2. Lippi G et al. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: A meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020 Mar 13. 506:145-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022.

3. Klok FA et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Throm Res. 2020;18(4):844-7. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013.

4. Fox S et al. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in Covid-19: The first autopsy series from New Orleans. MedRxiv. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.06.20050575.

5. Yang M et al. Thrombocytopenia in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (review). Hematology 2013 Sep 4. doi: 10.1080/1024533040002617.

6. Giannis D et al. Coagulation disorders in coronavirus infected patients: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and lessons from the past. J Clin Virol. 2020 June. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104362.

7. Guo W et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020 Mar 31. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3319.

8. Manalo IF et al. A dermatologic manifestation of COVID-19: Transient livedo reticularis. J Am Acad Dermat. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.018.

9. Tang N et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768, 18: 844-847.

10. Huang C et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

11. Thachil J et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Mar 25. doi: 10.1111/JTH.14810.

12. Tang N et al. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1111/JTH.14817.

13. Zhang Y et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-2019 pneumonia and acro-ischemia. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020 Mar 28. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2020.0006.

14. Poterucha TJ et al. More than an anticoagulant: Do heparins have direct anti-inflammatory effects? Thromb Haemost. 2017. doi: 10.1160/TH16-08-0620.

15. Mousavi S et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of heparin and its derivatives: A systematic review. Adv Pharmacol Pharm Sci. 2015 May 12. doi: 10.1155/2015/507151.

16. Kreuziger L et al. COVID-19 and VTE/anticoagulation: Frequently asked questions. American Society of Hematology. 2020 Apr 17.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a viral illness caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), currently causing a pandemic affecting many countries around the world, beginning in December 2019 and spreading rapidly on a global scale since. Globally, its burden has been increasing rapidly, with more than 1.2 million people testing positive for the illness and 123,000 people losing their lives, as per April 15th’s WHO COVID-19 Situation Report.1 These numbers are increasing with each passing day. Clinically, SARS-CoV-2 has a highly variable course, ranging from mild disease manifested as a self-limited illness (seen in younger and healthier patients) to severe pneumonia/ARDS and multiorgan failure with intravascular coagulopathy.2

In this article, we intend to investigate and establish a comprehensive review of COVID-19–associated coagulopathy mechanisms, laboratory findings, and current management guidelines put forth by various societies globally.

Mechanism of coagulopathy

COVID-19–associated coagulopathy has been shown to predispose to both arterial and venous thrombosis through excessive inflammation and hypoxia, leading to activation of the coagulation cascade and consumption of coagulation factors, resulting in microvascular thrombosis.3 Though the exact pathophysiology for the activation of this cascade is not known, the proposed mechanism has been: endothelial damage triggering platelet activation within the lung, leading to aggregation, thrombosis, and consumption of platelets in the lung.2,5,6

Fox et al. noted similar coagulopathy findings of four deceased COVID-19 patients. Autopsy results concluded that the dominant process was diffuse alveolar damage, notable CD4+ aggregates around thrombosed small vessels, significant associated hemorrhage, and thrombotic microangiopathy restricted to the lungs. The proposed mechanism was the activation of megakaryocytes, possibly native to the lung, with platelet aggregation, formation of platelet-rich clots, and fibrin deposition playing a major role.4

It has been noted that diabetic patients are at an increased risk of vascular events and hypercoagulability with COVID-19.7 COVID-19 can also cause livedo reticularis and acrocyanosis because of the microthrombosis in the cutaneous vasculature secondary to underlying coagulopathy, as reported in a case report of two U.S. patients with COVID-19.8

Clinical and laboratory abnormalities

A recent study reported from Netherlands by Klok et al. analyzed 184 ICU patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and concluded that the cumulative incidence of acute pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), ischemic stroke, MI, or systemic arterial embolism was 31% (95% confidence interval, 20%-41%). PE was the most frequent thrombotic complication and was noted in 81% of patients. Coagulopathy, defined as spontaneous prolongation of prothrombin time (PT) > 3s or activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) > 5s, was reported as an independent predictor of thrombotic complications.3

Hematologic abnormalities that were noted in COVID-19 coagulopathy include: decreased platelet counts, decreased fibrinogen levels, elevated PT/INR, elevated partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and elevated d-dimer.9,10 In a retrospective analysis9 by Tang et al., 71.4% of nonsurvivors and 0.6% of survivors had met the criteria of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) during their hospital stay. Nonsurvivors of COVID-19 had statistically significant elevation of d-dimer levels, FDP levels, PT, and aPTT, when compared to survivors (P < .05). The overall mortality in this study was reported as 11.5%.9 In addition, elevated d-dimer, fibrin and fibrinogen degradation product (FDP) levels and longer PT and aPTT were associated with poor prognosis.

Thus, d-dimer, PT, and platelet count should be measured in all patients who present with COVID-19 infection. We can also suggest that in patients with markedly elevated d-dimer (three- to fourfold increase), admission to hospital should be considered even in the absence of severe clinical symptoms.11

COVID-19 coagulopathy management

In a retrospective study9 of 449 patients with severe COVID-19 from Wuhan, China, by Tang et al., 99 patients mainly received low-weight molecular heparin (LMWH) for 7 days or longer. No difference in 28-day mortality was noted between heparin users and nonusers (30.3% vs. 29.7%; P = .910). A lower 28-day mortality rate was noted in heparin patients with sepsis-induced coagulopathy score of ≥4.0 (40.0% vs. 64.2%; P = .029) or a d-dimer level greater than sixfold of upper limit of normal, compared with nonusers of heparin.12

Another small study of seven COVID-19 patients with acroischemia in China demonstrated that administering LMWH was successful at decreasing the d-dimer and fibrinogen degradation product levels but noted no significant improvement in clinical symptoms.13

Recently, the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis and American Society of Hematology published recommendations and guidelines regarding the recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19.11 Prophylactic anticoagulation therapy with LMWH was recommended in all hospitalized patients with COVID-19, provided there was an absence of any contraindications (active bleeding, platelet count less than 25 x 109/L and fibrinogen less than 0.5 g/dL). Anticoagulation with LMWH was associated with better prognosis in severe COVID-19 patients and in COVID-19 patients with markedly elevated d-dimer, as it also has anti-inflammatory effects.12 This anti-inflammatory property of heparin has been documented in previous studies but the underlying mechanism is unknown and more research is required.14,15

Despite coagulopathy being noticed with cases of COVID-19, bleeding has been a rare finding in COVID-19 infections. If bleeding is noted, recommendations were made to keep platelet levels greater than 50 x109/L, fibrinogen less than 2.0 g/L, and INR [international normalized ratio] greater than 1.5.11 Mechanical thromboprophylaxis should be used when pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis is contraindicated.16

COVID-19 patients with new diagnoses of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or atrial fibrillation should be prescribed therapeutic anticoagulation. Patients who are already on anticoagulation for VTE or atrial fibrillation should continue their therapy unless the platelet count is less than 30-50x109/L or if the fibrinogen is less than 1.0 g/L.16

Conclusion

Coagulopathies associated with COVID-19 infections have been documented in several studies around the world, and it has been shown to be fatal in some cases. Despite documentation, the mechanism behind this coagulopathy is not well understood. Because of the potentially lethal complications associated with coagulopathies, early recognition and anticoagulation is imperative to improve clinical outcomes. These results are very preliminary: More studies are required to understand the role of anticoagulation and its effect on the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19–associated coagulopathy.

Dr. Yeruva is a board-certified hematologist/medical oncologist with WellSpan Health and clinical assistant professor of internal medicine, Penn State University, Hershey. Mr. Henderson is a third-year graduate-entry medical student at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland with interests in family medicine, dermatology, and tropical diseases. Dr. Al-Tawfiq is a consultant of internal medicine & infectious diseases, and the director of quality at Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, an adjunct associate professor of infectious diseases, molecular medicine and clinical pharmacology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and adjunct associate professor at Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis. Dr. Tirupathi is the medical director of Keystone Infectious Diseases/HIV in Chambersburg, Pa., and currently chair of infection prevention at Wellspan Chambersburg and Waynesboro (Pa.) Hospitals. He also is the lead physician for antibiotic stewardship at these hospitals.

References

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports.

2. Lippi G et al. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: A meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020 Mar 13. 506:145-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022.

3. Klok FA et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Throm Res. 2020;18(4):844-7. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013.

4. Fox S et al. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in Covid-19: The first autopsy series from New Orleans. MedRxiv. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.06.20050575.

5. Yang M et al. Thrombocytopenia in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (review). Hematology 2013 Sep 4. doi: 10.1080/1024533040002617.

6. Giannis D et al. Coagulation disorders in coronavirus infected patients: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and lessons from the past. J Clin Virol. 2020 June. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104362.

7. Guo W et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020 Mar 31. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3319.

8. Manalo IF et al. A dermatologic manifestation of COVID-19: Transient livedo reticularis. J Am Acad Dermat. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.018.

9. Tang N et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768, 18: 844-847.

10. Huang C et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

11. Thachil J et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Mar 25. doi: 10.1111/JTH.14810.

12. Tang N et al. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Mar 27. doi: 10.1111/JTH.14817.

13. Zhang Y et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-2019 pneumonia and acro-ischemia. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020 Mar 28. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2020.0006.

14. Poterucha TJ et al. More than an anticoagulant: Do heparins have direct anti-inflammatory effects? Thromb Haemost. 2017. doi: 10.1160/TH16-08-0620.

15. Mousavi S et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of heparin and its derivatives: A systematic review. Adv Pharmacol Pharm Sci. 2015 May 12. doi: 10.1155/2015/507151.

16. Kreuziger L et al. COVID-19 and VTE/anticoagulation: Frequently asked questions. American Society of Hematology. 2020 Apr 17.

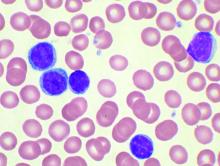

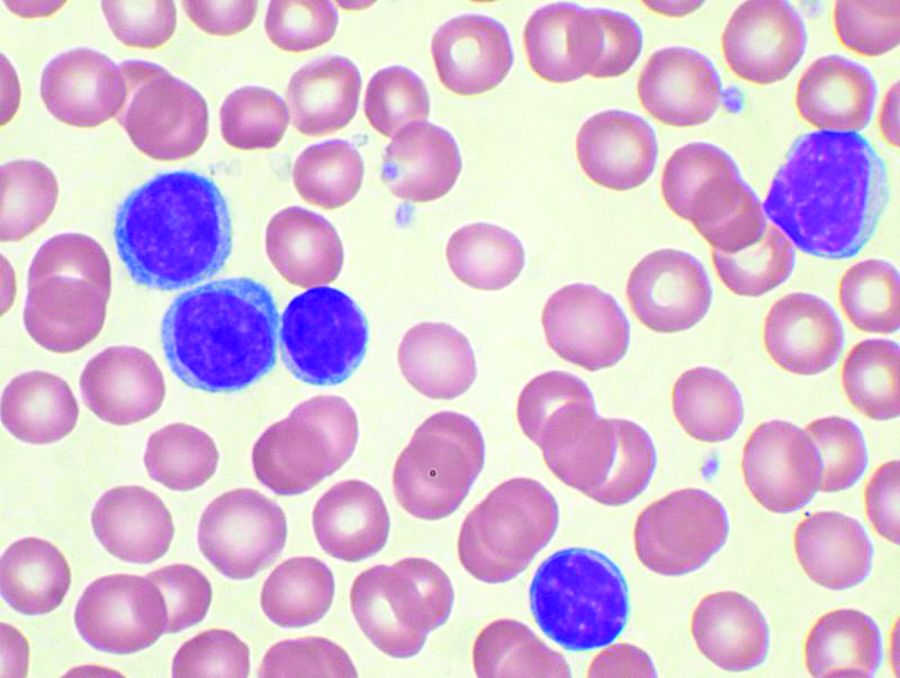

Transplant beats bortezomib-based therapy for MM, but questions remain

While upfront autologous transplantation has bested bortezomib-based intensification therapy in a large, randomized multiple myeloma (MM) trial, investigators and observers say more research will be needed to determine the optimal treatment strategy in the era of novel agents.

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) extended progression-free survival by almost 15 months compared with bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone (VMP) intensification therapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, according to results of the randomized, phase 3 trial of 1,503 patients enrolled at 172 centers in the European Myeloma Network.

That finding could provide more fodder for the ongoing debate over the role of upfront autologous HSCT as a gold-standard intensification treatment for patients who can tolerate myeloablative doses of chemotherapy in light of the proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs, and monoclonal antibodies that are now available.

However, the study is not without limitations, including the use of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone (VCD) as induction therapy, according to the investigators, led by Michele Cavo, MD, with the Seràgnoli Institute of Hematology at Bologna (Italy) University.

The VCD regimen was one of the most frequently used induction regimens back when the trial was designed, but now it’s considered “less optimal” versus regimens such as bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (VRD), according to Dr. Cavo and coinvestigators.

Besides, the field is moving forward based on clinical trials of “highly active” daratumumab-based four-drug regimens, which appear to enhance rates of response and minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity when given as induction before autologous HSCT and as consolidation afterward, they said.

“Final results from these studies should be awaited before a shift from routine use of upfront autologous HSCT to delayed HSCT or alternative treatment strategies driven by MRD status can be offered to patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are fit for high-dose chemotherapy,” Dr. Cavo and colleagues noted in their report, available in The Lancet Hematology.

The multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase 3 study by Dr. Cavo and coinvestigators, known as EMN02/HO95, included patients up to 65 years of age with symptomatic multiple myeloma, measurable disease, and WHO performance of 0 to 2. Patients were treated with VCD induction therapy, followed by randomization to either VMP or autologous HSCT after high-dose melphalan. In a second randomization, patients were assigned to either VRD consolidation therapy or no consolidation. All patients then received lenalidomide maintenance therapy until progression.

Median progression-free survival was 56.7 months in patients initially randomized to HSCT, compared with 41.9 months for MP (hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.62-0.85; P = .0001), according to the investigators, who said that finding supports the value of HSCT “even in the era of highly active novel agents.”

Turning to results of the second randomization, Dr. Cavo and colleagues said the VRD consolidation strategy resulted in median progression-free survival that was significantly improved versus no consolidation, at 58.9 months and 45.5 months, respectively (P = .014).

While this is an important study, the added benefit of HSCT intensification therapy is in question given the high rates of MRD being reported for potent, daratumumab-based four-drug combination regimens, according to a related commentary by Omar Nadeem, MD, and Irene M. Ghobrial, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“We are entering an era in which novel combinations have shown unprecedented efficacy and future studies with or without HSCT will be needed to answer these key questions,” wrote Dr. Nadeem and Dr. Ghobrial.

Dr. Cavo and colleagues said the estimated 5-year rate of overall survival in EMN02/HO95 was “comparable” between arms, at 75% for the HSCT strategy and 72% for VMP.

“Although this suggests that delaying HSCT to a later time is not harmful, a substantial proportion of patients may become ineligible for high-dose melphalan at first relapse,” they said, noting that 63% of VMP-treated patients went on to receive salvage HSCT.

Further follow-up could demonstrate a survival advantage, as seen in other studies, they added.

Dr. Cavo reported that he has received honoraria from multiple pharmaceutical companies, and is a member of speakers bureaus for Janssen and Celgene. Dr. Nadeem and Dr. Ghobrial reported serving on the advisory boards of multiple pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Cavo M et al. Lancet Haematol. 2020 Apr 30. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30099-5.

While upfront autologous transplantation has bested bortezomib-based intensification therapy in a large, randomized multiple myeloma (MM) trial, investigators and observers say more research will be needed to determine the optimal treatment strategy in the era of novel agents.

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) extended progression-free survival by almost 15 months compared with bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone (VMP) intensification therapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, according to results of the randomized, phase 3 trial of 1,503 patients enrolled at 172 centers in the European Myeloma Network.

That finding could provide more fodder for the ongoing debate over the role of upfront autologous HSCT as a gold-standard intensification treatment for patients who can tolerate myeloablative doses of chemotherapy in light of the proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs, and monoclonal antibodies that are now available.

However, the study is not without limitations, including the use of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone (VCD) as induction therapy, according to the investigators, led by Michele Cavo, MD, with the Seràgnoli Institute of Hematology at Bologna (Italy) University.

The VCD regimen was one of the most frequently used induction regimens back when the trial was designed, but now it’s considered “less optimal” versus regimens such as bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (VRD), according to Dr. Cavo and coinvestigators.

Besides, the field is moving forward based on clinical trials of “highly active” daratumumab-based four-drug regimens, which appear to enhance rates of response and minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity when given as induction before autologous HSCT and as consolidation afterward, they said.

“Final results from these studies should be awaited before a shift from routine use of upfront autologous HSCT to delayed HSCT or alternative treatment strategies driven by MRD status can be offered to patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are fit for high-dose chemotherapy,” Dr. Cavo and colleagues noted in their report, available in The Lancet Hematology.

The multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase 3 study by Dr. Cavo and coinvestigators, known as EMN02/HO95, included patients up to 65 years of age with symptomatic multiple myeloma, measurable disease, and WHO performance of 0 to 2. Patients were treated with VCD induction therapy, followed by randomization to either VMP or autologous HSCT after high-dose melphalan. In a second randomization, patients were assigned to either VRD consolidation therapy or no consolidation. All patients then received lenalidomide maintenance therapy until progression.

Median progression-free survival was 56.7 months in patients initially randomized to HSCT, compared with 41.9 months for MP (hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.62-0.85; P = .0001), according to the investigators, who said that finding supports the value of HSCT “even in the era of highly active novel agents.”

Turning to results of the second randomization, Dr. Cavo and colleagues said the VRD consolidation strategy resulted in median progression-free survival that was significantly improved versus no consolidation, at 58.9 months and 45.5 months, respectively (P = .014).

While this is an important study, the added benefit of HSCT intensification therapy is in question given the high rates of MRD being reported for potent, daratumumab-based four-drug combination regimens, according to a related commentary by Omar Nadeem, MD, and Irene M. Ghobrial, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“We are entering an era in which novel combinations have shown unprecedented efficacy and future studies with or without HSCT will be needed to answer these key questions,” wrote Dr. Nadeem and Dr. Ghobrial.

Dr. Cavo and colleagues said the estimated 5-year rate of overall survival in EMN02/HO95 was “comparable” between arms, at 75% for the HSCT strategy and 72% for VMP.

“Although this suggests that delaying HSCT to a later time is not harmful, a substantial proportion of patients may become ineligible for high-dose melphalan at first relapse,” they said, noting that 63% of VMP-treated patients went on to receive salvage HSCT.

Further follow-up could demonstrate a survival advantage, as seen in other studies, they added.

Dr. Cavo reported that he has received honoraria from multiple pharmaceutical companies, and is a member of speakers bureaus for Janssen and Celgene. Dr. Nadeem and Dr. Ghobrial reported serving on the advisory boards of multiple pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Cavo M et al. Lancet Haematol. 2020 Apr 30. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30099-5.

While upfront autologous transplantation has bested bortezomib-based intensification therapy in a large, randomized multiple myeloma (MM) trial, investigators and observers say more research will be needed to determine the optimal treatment strategy in the era of novel agents.

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) extended progression-free survival by almost 15 months compared with bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone (VMP) intensification therapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, according to results of the randomized, phase 3 trial of 1,503 patients enrolled at 172 centers in the European Myeloma Network.

That finding could provide more fodder for the ongoing debate over the role of upfront autologous HSCT as a gold-standard intensification treatment for patients who can tolerate myeloablative doses of chemotherapy in light of the proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs, and monoclonal antibodies that are now available.

However, the study is not without limitations, including the use of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone (VCD) as induction therapy, according to the investigators, led by Michele Cavo, MD, with the Seràgnoli Institute of Hematology at Bologna (Italy) University.

The VCD regimen was one of the most frequently used induction regimens back when the trial was designed, but now it’s considered “less optimal” versus regimens such as bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (VRD), according to Dr. Cavo and coinvestigators.

Besides, the field is moving forward based on clinical trials of “highly active” daratumumab-based four-drug regimens, which appear to enhance rates of response and minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity when given as induction before autologous HSCT and as consolidation afterward, they said.

“Final results from these studies should be awaited before a shift from routine use of upfront autologous HSCT to delayed HSCT or alternative treatment strategies driven by MRD status can be offered to patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are fit for high-dose chemotherapy,” Dr. Cavo and colleagues noted in their report, available in The Lancet Hematology.

The multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase 3 study by Dr. Cavo and coinvestigators, known as EMN02/HO95, included patients up to 65 years of age with symptomatic multiple myeloma, measurable disease, and WHO performance of 0 to 2. Patients were treated with VCD induction therapy, followed by randomization to either VMP or autologous HSCT after high-dose melphalan. In a second randomization, patients were assigned to either VRD consolidation therapy or no consolidation. All patients then received lenalidomide maintenance therapy until progression.

Median progression-free survival was 56.7 months in patients initially randomized to HSCT, compared with 41.9 months for MP (hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.62-0.85; P = .0001), according to the investigators, who said that finding supports the value of HSCT “even in the era of highly active novel agents.”

Turning to results of the second randomization, Dr. Cavo and colleagues said the VRD consolidation strategy resulted in median progression-free survival that was significantly improved versus no consolidation, at 58.9 months and 45.5 months, respectively (P = .014).

While this is an important study, the added benefit of HSCT intensification therapy is in question given the high rates of MRD being reported for potent, daratumumab-based four-drug combination regimens, according to a related commentary by Omar Nadeem, MD, and Irene M. Ghobrial, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“We are entering an era in which novel combinations have shown unprecedented efficacy and future studies with or without HSCT will be needed to answer these key questions,” wrote Dr. Nadeem and Dr. Ghobrial.

Dr. Cavo and colleagues said the estimated 5-year rate of overall survival in EMN02/HO95 was “comparable” between arms, at 75% for the HSCT strategy and 72% for VMP.

“Although this suggests that delaying HSCT to a later time is not harmful, a substantial proportion of patients may become ineligible for high-dose melphalan at first relapse,” they said, noting that 63% of VMP-treated patients went on to receive salvage HSCT.

Further follow-up could demonstrate a survival advantage, as seen in other studies, they added.

Dr. Cavo reported that he has received honoraria from multiple pharmaceutical companies, and is a member of speakers bureaus for Janssen and Celgene. Dr. Nadeem and Dr. Ghobrial reported serving on the advisory boards of multiple pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Cavo M et al. Lancet Haematol. 2020 Apr 30. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30099-5.

FROM THE LANCET HEMATOLOGY

COVID-19 pulmonary severity ascribed to coagulation differences

Differences in COVID-19-related death rates between people of white and Asian ancestry may be partly explained by documented ethnic/racial differences in risk for blood clotting and pulmonary thrombotic events, investigators propose.

“Our novel findings demonstrate that COVID-19 is associated with a unique type of blood clotting disorder that is primarily focused within the lungs and which undoubtedly contributes to the high levels of mortality being seen in patients with COVID-19,” said James O’Donnell, MB, PhD, director of the Irish Centre for Vascular Biology at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

Dr. O’Donnell and colleagues studied pulmonary effects and outcomes of 83 patients admitted to St. James Hospital in Dublin, and found evidence to suggest that the diffuse, bilateral pulmonary inflammation seen in many patients with severe COVID-19 infections may be caused by a pulmonary-specific vasculopathy they label “pulmonary intravascular coagulopathy” (PIC), an entity distinct from disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC).

“Given that thrombotic risk is significantly impacted by race, coupled with the accumulating evidence that coagulopathy is important in COVID-19 pathogenesis, our findings raise the intriguing possibility that pulmonary vasculopathy may contribute to the unexplained differences that are beginning to emerge highlighting racial susceptibility to COVID-19 mortality,” they wrote in a study published online in the British Journal of Haematology.

Study flaws harm conclusions

But critical care specialists who agreed to review and comment on the study for MDedge News said that it has significant flaws that affect the ability to interpret the findings and “undermine the conclusions reached by the authors.”

“The underlying premise of the study is that there are racial and ethnic differences in the development of venous thromboembolism that may explain the racial and ethnic differences in outcomes from COVID-19,” J. Daryl Thornton, MD, MPH, a fellow of the American Thoracic Society and associate professor of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said in an interview. “This is an interesting hypothesis and one that could be easily tested in a well-designed study with sufficient representation from the relevant racial and ethnic groups. However, this study is neither well designed nor does it have sufficient racial and ethnic representation.”

Elliott R. Haut, MD, PhD, associate professor of surgery, anesthesiology and critical care medicine at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, said in an interview that the study is “mediocre” and has the feel of a paper rushed to press.

“It talks about their theory that race, ethnicity, have an effect on venous thromboembolism, and that’s a pretty well-known fact. No one’s a hundred percent sure why that is, but certainly there are tons and tons of papers that show that there are groups that are at higher risk than others,” he said. “Their idea that this is caused by this pulmonary inflammation, that is totally a guess; there is no data in this paper to support that.”

Dr. Thornton and Dr. Haut both noted that the authors don’t define how race and ethnicity were determined and whether patients were asked to provide it, and although they mention the racial/ethnic breakdown once, subsequent references are to entire cohort are as “Caucasian.”

They also called into question the value of comparing laboratory data across continents in centers with different testing methods and parameters, especially in a time when the clinical picture changes so rapidly.

Coagulation differences

Dr. O’Donnell and colleagues noted that most studies of COVID-19-associated coagulopathy published to date have been with Chinese patients.

“This is important because race and ethnicity have major effects upon thrombotic risk. In particular, epidemiological studies have shown that the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is approximately three to fourfold lower in Chinese compared to Caucasian individuals. Conversely, VTE risk is significantly higher in African-Americans compared to Caucasians,” they wrote.

Because of the lower risk of VTE in the Chinese population, thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or other agents is less frequently used in Chinese hospitals than in hospitals with predominantly non-Asian patients, they noted.

To see whether the were differences in coagulopathy between Chinese and white patients, the researchers enrolled 55 men and 28 women, median age 64, who were admitted to St. James Hospital with COVID-19 infections from March 13 through April 10, 2020. The cohort included 67 patients of white background, 10 of Asian ancestry, 5 of African ethnicity, and 1 of Latino/Hispanic ancestry.

Of the 83 patients, 67 had comorbidities at admission. At the time of the report, 50 patients had fully recovered and were discharged, 20 remained in the hospital, and 13 had died. In all, 50 patients were discharged without needing ICU care, 23 were admitted to the ICU, and 10 required ICU but were deemed “clinically unsuitable” for ICU admission.

Although the patients had normal prothrombin time (PT) and normal activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), plasma d-dimer levels were significantly elevated and were above the range of normal in two-thirds of patients on admission.

Despite the increased d-dimer levels, however, there was no evidence of DIC as defined by the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis Scientific and Standardization committee (ISTH SSC) guidelines. Platelet counts were in the normal range in 83.1% of patients, and only five had counts less than 100 x 109/L at admission. Fibrinogen levels were also elevated, as were C-reactive protein levels, both likely indicating an acute phase response.

“Thus, despite the fact that thrombotic risk is much higher in Caucasian patients and the significant elevated levels of d-dimers observed, overt DIC as defined according to the ISTH SSC DIC score was present in none of our COVID-19 patients at time of admission. Nevertheless, our data confirm that severe COVID-19 infection is associated with a significant coagulopathy in Caucasian patients that appears to be similar in magnitude to that previously reported in the original Chinese cohorts,” they wrote.

When they compared patients who required ICU admission for ventilator support and those who died with patients who were discharged without needing ICU support, they found that survivors were younger (median age 60.2 vs. 75.2 years), and that more critically ill patients were more likely to have comorbidities.

They also found that patients with abnormal coagulation parameters on admission were significantly more likely to have poor prognosis (P = .018), and that patients in the adverse outcomes group had significantly higher fibrinogen and CRP levels (P = .045 and .0005, respectively).

There was no significant difference in PT between the prognosis groups at admission, but by day 4 and beyond PT was a median of 13.1 vs. 12.5 seconds in the favorable outcomes groups (P = .007), and patients with poor prognosis continued to have significantly higher d-dimer levels. (P = .003)

“Cumulatively, these data support the hypothesis that COVID-19–associated coagulopathy probably contributes to the underlying pulmonary pathogenesis,” the researchers wrote.

They noted that the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor that COVID-19 uses to enter cells is expressed on both type II pneumocytes and vascular endothelial cells within the lung, suggesting that the coagulopathy may be related to direct pulmonary endothelial cell infection , activation, and/or damage, and to the documented cytokine storm that can affect thrombin generation and fibrin deposition within the lungs.

“In the context of this lung-centric vasculopathy, we hypothesize that the refractory acute respiratory distress syndrome phenotype observed in severe COVID-19 is due to concurrent ‘double-hit’ pathologies targeting both ventilation (V) and perfusion (Q) within the lungs where alveoli and pulmonary microvasculature exist in close anatomical juxtaposition,” they wrote.

The investigators noted that larger randomized trials will be needed to determine whether more aggressive anti-coagulation and/or targeted anti-inflammatory therapies could effectively treated PIC in patients with severe COVID-19.

The study was supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Health Research Board Health Service and the Research and Development Division, Northern Ireland. Dr. O’Donnell disclosed speakers bureau activities, advisory board participation, and research grants from multiple companies. The other doctors had no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Fogarty H et al. Br J Haematol. 2020 Apr 24. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16749.

Differences in COVID-19-related death rates between people of white and Asian ancestry may be partly explained by documented ethnic/racial differences in risk for blood clotting and pulmonary thrombotic events, investigators propose.

“Our novel findings demonstrate that COVID-19 is associated with a unique type of blood clotting disorder that is primarily focused within the lungs and which undoubtedly contributes to the high levels of mortality being seen in patients with COVID-19,” said James O’Donnell, MB, PhD, director of the Irish Centre for Vascular Biology at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

Dr. O’Donnell and colleagues studied pulmonary effects and outcomes of 83 patients admitted to St. James Hospital in Dublin, and found evidence to suggest that the diffuse, bilateral pulmonary inflammation seen in many patients with severe COVID-19 infections may be caused by a pulmonary-specific vasculopathy they label “pulmonary intravascular coagulopathy” (PIC), an entity distinct from disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC).

“Given that thrombotic risk is significantly impacted by race, coupled with the accumulating evidence that coagulopathy is important in COVID-19 pathogenesis, our findings raise the intriguing possibility that pulmonary vasculopathy may contribute to the unexplained differences that are beginning to emerge highlighting racial susceptibility to COVID-19 mortality,” they wrote in a study published online in the British Journal of Haematology.

Study flaws harm conclusions

But critical care specialists who agreed to review and comment on the study for MDedge News said that it has significant flaws that affect the ability to interpret the findings and “undermine the conclusions reached by the authors.”