User login

-

Orthopedic problems in children can be the first indication of acute lymphoblastic leukemia

The diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) can be delayed because of vague presentation and normal hematological results. Orthopedic manifestations may be the primary presentation of ALL to physicians, and such symptoms in children should be cause for suspicion, even in the absence of hematological abnormalities, according to a report published in the Journal of Orthopaedics.

The study retrospectively assessed 250 consecutive ALL patients at a single institution to identify the frequency of ALL cases presented to the orthopedic department and to determine the number of these patients presenting with normal hematological results, according to Amrath Raj BK, MD, and colleagues at the Manipal (India) Academy of Higher Education.

Suspicion warranted

Twenty-two of the 250 patients (8.8%) presented primarily to the orthopedic department (4 with vertebral compression fractures, 12 with joint pain, and 6 with bone pain), but were subsequently diagnosed with ALL. These results were comparable to previous studies. The mean patient age at the first visit was 5.6 years; 13 patients were boys, and 9 were girls. Six of these 22 patients (27.3%) had a normal peripheral blood smear, according to the researchers.

“Acute leukemia should be considered strongly as a differential diagnosis in children with severe osteoporosis and vertebral fractures. Initial orthopedic manifestations are not uncommon, and the primary physician should maintain a high index of suspicion as a peripheral smear is not diagnostic in all patients,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that there was no outside funding source and that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Raj BK A et al. Journal of Orthopaedics. 2020;22:326-330.

The diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) can be delayed because of vague presentation and normal hematological results. Orthopedic manifestations may be the primary presentation of ALL to physicians, and such symptoms in children should be cause for suspicion, even in the absence of hematological abnormalities, according to a report published in the Journal of Orthopaedics.

The study retrospectively assessed 250 consecutive ALL patients at a single institution to identify the frequency of ALL cases presented to the orthopedic department and to determine the number of these patients presenting with normal hematological results, according to Amrath Raj BK, MD, and colleagues at the Manipal (India) Academy of Higher Education.

Suspicion warranted

Twenty-two of the 250 patients (8.8%) presented primarily to the orthopedic department (4 with vertebral compression fractures, 12 with joint pain, and 6 with bone pain), but were subsequently diagnosed with ALL. These results were comparable to previous studies. The mean patient age at the first visit was 5.6 years; 13 patients were boys, and 9 were girls. Six of these 22 patients (27.3%) had a normal peripheral blood smear, according to the researchers.

“Acute leukemia should be considered strongly as a differential diagnosis in children with severe osteoporosis and vertebral fractures. Initial orthopedic manifestations are not uncommon, and the primary physician should maintain a high index of suspicion as a peripheral smear is not diagnostic in all patients,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that there was no outside funding source and that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Raj BK A et al. Journal of Orthopaedics. 2020;22:326-330.

The diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) can be delayed because of vague presentation and normal hematological results. Orthopedic manifestations may be the primary presentation of ALL to physicians, and such symptoms in children should be cause for suspicion, even in the absence of hematological abnormalities, according to a report published in the Journal of Orthopaedics.

The study retrospectively assessed 250 consecutive ALL patients at a single institution to identify the frequency of ALL cases presented to the orthopedic department and to determine the number of these patients presenting with normal hematological results, according to Amrath Raj BK, MD, and colleagues at the Manipal (India) Academy of Higher Education.

Suspicion warranted

Twenty-two of the 250 patients (8.8%) presented primarily to the orthopedic department (4 with vertebral compression fractures, 12 with joint pain, and 6 with bone pain), but were subsequently diagnosed with ALL. These results were comparable to previous studies. The mean patient age at the first visit was 5.6 years; 13 patients were boys, and 9 were girls. Six of these 22 patients (27.3%) had a normal peripheral blood smear, according to the researchers.

“Acute leukemia should be considered strongly as a differential diagnosis in children with severe osteoporosis and vertebral fractures. Initial orthopedic manifestations are not uncommon, and the primary physician should maintain a high index of suspicion as a peripheral smear is not diagnostic in all patients,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that there was no outside funding source and that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Raj BK A et al. Journal of Orthopaedics. 2020;22:326-330.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ORTHOPAEDICS

Children’s share of new COVID-19 cases is on the rise

The cumulative percentage of COVID-19 cases reported in children continues to climb, but “the history behind that cumulative number shows substantial change,” according to a new analysis of state health department data.

As of Sept. 10, the 549,432 cases in children represented 10.0% of all reported COVID-19 cases in the United States following a substantial rise over the course of the pandemic – the figure was 7.7% on July 16 and 3.2% on May 7, Blake Sisk, PhD, of the American Academy of Pediatrics and associates reported Sept. 29 in Pediatrics.

Unlike the cumulative number, the weekly proportion of cases in children fell early in the summer but then started climbing again in late July. Dr. Sisk and associates wrote.

Despite the increase, however, the proportion of pediatric COVID-19 cases is still well below children’s share of the overall population (22.6%). Also, “it is unclear how much of the increase in child cases is due to increased testing capacity, although CDC data from public and commercial laboratories show the share of all tests administered to children ages 0-17 has remained stable at 5%-7% since late April,” they said.

Data for the current report were drawn from 49 state health department websites (New York state does not report ages for COVID-19 cases), along with New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Alabama changed its definition of a child case in August and was not included in the trend analysis (see graph), the investigators explained.

Those data show “substantial variation in case growth by region: in April, a preponderance of cases was in the Northeast. In June, cases surged in the South and West, followed by mid-July increases in the Midwest,” Dr. Sisk and associates said.

The increase among children in Midwest states is ongoing with the number of new cases reaching its highest level yet during the week ending Sept. 10, they reported.

SOURCE: Sisk B et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep 29. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-027425.

The cumulative percentage of COVID-19 cases reported in children continues to climb, but “the history behind that cumulative number shows substantial change,” according to a new analysis of state health department data.

As of Sept. 10, the 549,432 cases in children represented 10.0% of all reported COVID-19 cases in the United States following a substantial rise over the course of the pandemic – the figure was 7.7% on July 16 and 3.2% on May 7, Blake Sisk, PhD, of the American Academy of Pediatrics and associates reported Sept. 29 in Pediatrics.

Unlike the cumulative number, the weekly proportion of cases in children fell early in the summer but then started climbing again in late July. Dr. Sisk and associates wrote.

Despite the increase, however, the proportion of pediatric COVID-19 cases is still well below children’s share of the overall population (22.6%). Also, “it is unclear how much of the increase in child cases is due to increased testing capacity, although CDC data from public and commercial laboratories show the share of all tests administered to children ages 0-17 has remained stable at 5%-7% since late April,” they said.

Data for the current report were drawn from 49 state health department websites (New York state does not report ages for COVID-19 cases), along with New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Alabama changed its definition of a child case in August and was not included in the trend analysis (see graph), the investigators explained.

Those data show “substantial variation in case growth by region: in April, a preponderance of cases was in the Northeast. In June, cases surged in the South and West, followed by mid-July increases in the Midwest,” Dr. Sisk and associates said.

The increase among children in Midwest states is ongoing with the number of new cases reaching its highest level yet during the week ending Sept. 10, they reported.

SOURCE: Sisk B et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep 29. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-027425.

The cumulative percentage of COVID-19 cases reported in children continues to climb, but “the history behind that cumulative number shows substantial change,” according to a new analysis of state health department data.

As of Sept. 10, the 549,432 cases in children represented 10.0% of all reported COVID-19 cases in the United States following a substantial rise over the course of the pandemic – the figure was 7.7% on July 16 and 3.2% on May 7, Blake Sisk, PhD, of the American Academy of Pediatrics and associates reported Sept. 29 in Pediatrics.

Unlike the cumulative number, the weekly proportion of cases in children fell early in the summer but then started climbing again in late July. Dr. Sisk and associates wrote.

Despite the increase, however, the proportion of pediatric COVID-19 cases is still well below children’s share of the overall population (22.6%). Also, “it is unclear how much of the increase in child cases is due to increased testing capacity, although CDC data from public and commercial laboratories show the share of all tests administered to children ages 0-17 has remained stable at 5%-7% since late April,” they said.

Data for the current report were drawn from 49 state health department websites (New York state does not report ages for COVID-19 cases), along with New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Alabama changed its definition of a child case in August and was not included in the trend analysis (see graph), the investigators explained.

Those data show “substantial variation in case growth by region: in April, a preponderance of cases was in the Northeast. In June, cases surged in the South and West, followed by mid-July increases in the Midwest,” Dr. Sisk and associates said.

The increase among children in Midwest states is ongoing with the number of new cases reaching its highest level yet during the week ending Sept. 10, they reported.

SOURCE: Sisk B et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep 29. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-027425.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Pandemic poses new challenges for rural doctors

These include struggling with seeing patients virtually and treating patients who have politicized the virus. Additionally, the pandemic has exposed rural practices to greater financial difficulties.

Before the pandemic some rurally based primary care physicians were already working through big challenges, such as having few local medical colleagues to consult and working in small practices with lean budgets. In fact, data gathered by the National Rural Health Association showed that there are only 40 primary care physicians per 100,000 patients in rural regions, compared with 53 in urban areas – and the number of physicians overall is 13 per 10,000 in rural areas, compared with 31 in cities.

In the prepandemic world, for some doctors, the challenges were balanced by the benefits of practicing in these sparsely populated communities with scenic, low-traffic roads. Some perks of practicing in rural areas touted by doctors included having a fast commute, being able to swim in a lake near the office before work, having a low cost of living, and feeling like they are making a difference in their communities as they treat generations of the families they see around town.

But today, new hurdles to practicing medicine in rural America created by the COVID-19 pandemic have caused the hardships to feel heavier than the joys at times for some physicians interviewed by MDedge.

Many independent rural practices in need of assistance were not able to get much from the federal Provider Relief Funds, said John M. Westfall, MD, who is director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care, in an interview.

“Rural primary care doctors function independently or in smaller critical access hospitals and community health centers,” said Dr. Westfall, who previously practiced family medicine in a small town in Colorado. “Many of these have much less financial reserves so are at risk of cutbacks and closure.”

Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, an internist based in a tiny Georgia community along the highway between Atlanta and Augusta, said her small practice works on really thin margins and doesn’t have much cushion. At the beginning of the pandemic, all visits were down, and her practice operated at a loss. To help, Dr. Fincher and her colleagues applied for funding from the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) through the CARES Act.

“COVID-19 has had a tremendous impact especially on primary care practices. We live and die by volume. … Our volume in mid-March to mid-May really dropped dramatically,” explained Dr. Fincher, who is also president of the American College of Physicians. “The PPP sustained us for 2 months, enabling us to pay our staff and to remain open and get us up and running on telehealth.”

Starting up telemedicine

Experiencing spotty or no access to broadband Internet is nothing new to rural physicians, but having this problem interfere with their ability to provide care to patients is.

As much of the American health system rapidly embraced telehealth during the pandemic, obtaining access to high-speed Internet has been a major challenge for rural patients, noted Dr. Westfall.

“Some practices were able to quickly adopt some telehealth capacity with phone and video. Changes in payment for telehealth helped. But in some rural communities there was not adequate Internet bandwidth for quality video connections. And some patients did not have the means for high-speed video connections,” Dr. Westfall said.

Indeed, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, 63% of rural Americans say they can access the Internet through a broadband connection at home, compared with 75% and 79% in suburban and urban areas, respectively.

In the Appalachian town of Zanesville, Ohio, for example, family physician Shelly L. Dunmyer, MD, and her colleagues discovered that many patients don’t have Internet access at home. Dr. Fincher has to go to the office to conduct telehealth visits because her own Internet access at home is unpredictable. As for patients, it may take 15 minutes for them to work out technical glitches and find good Internet reception, said Dr. Fincher. For internist Y. Ki Shin, MD, who practices in the coastal town of Montesano in Washington state, about 25% of his practice’s telehealth visits must be conducted by phone because of limitations on video, such as lack of high-speed access.

But telephone visits are often insufficient replacements for appointments via video, according to several rural physicians interviewed for this piece.

“Telehealth can be frustrating at times due to connectivity issues which can be difficult at times in the rural areas,” said Dr. Fincher. “In order for telehealth to be reasonably helpful to patients and physicians to care for people with chronic problems, the patients must have things like blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and scales to address problems like hypertension, diabetes myelitis, and congestive heart failure.”

“If you have the audio and video and the data from these devices, you’re good. If you don’t have these data, and/or don’t have the video you just can’t provide good care,” she explained.

Dr. Dunmyer and her colleagues at Medical Home Primary Care Center in Zanesville, Ohio, found a way to get around the problem of patients not being able to access Internet to participate in video visits from their homes. This involved having her patients drive into her practice’s parking lot to participate in modified telehealth visits. Staffers gave iPads to patients in their cars, and Dr. Dunmyer conducted visits from her office, about 50 yards away.

“We were even doing Medicare wellness visits: Instead of asking them to get up and move around the room, we would sit at the window and wave at them, ask them to get out, walk around the car. We were able to check mobility and all kinds of things that we’d normally do in the office,” Dr. Dunmyer explained in an interview.

The family physician noted that her practice is now conducting fewer parking lot visits since her office is allowing in-person appointments, but that they’re still an option for her patients.

Treating political adversaries

Some rural physicians have experienced strained relationships with patients for reasons other than technology – stark differences in opinion over the pandemic itself. Certain patients are following President Trump’s lead and questioning everything from the pandemic death toll to preventive measures recommended by scientists and medical experts, physicians interviewed by MDedge said.

Patients everywhere share these viewpoints, of course, but research and election results confirm that rural areas are more receptive to conservative viewpoints. In 2018, a Pew Research Center survey reported that rural and urban areas are “becoming more polarized politically,” and “rural areas tend to have a higher concentration of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.” For example, 40% of rural respondents reported “very warm” or “somewhat warm” feelings toward Donald Trump, compared with just 19% in urban areas.

Dr. Shin has struggled to cope with patients who want to argue about pandemic safety precautions like wearing masks and seem to question whether systemic racism exists.

“We are seeing a lot more people who feel that this pandemic is not real, that it’s a political and not-true infection,” he said in an interview. “We’ve had patients who were angry at us because we made them wear masks, and some were demanding hydroxychloroquine and wanted to have an argument because we’re not going to prescribe it for them.”

In one situation, which he found especially disturbing, Dr. Shin had to leave the exam room because a patient wouldn’t stop challenging him regarding the pandemic. Things have gotten so bad that Dr. Shin has even questioned whether he wants to continue his long career in his small town because of local political attitudes such as opposition to mask-wearing and social distancing.

“Mr. Trump’s misinformation on this pandemic made my job much more difficult. As a minority, I feel less safe in my community than ever,” said Dr. Shin, who described himself as Asian American.

Despite these new stressors, Dr. Shin has experienced some joyful moments while practicing medicine in the pandemic.

He said a recent home visit to a patient who had been hospitalized for over 3 months and nearly died helped him put political disputes with his patients into perspective.

“He was discharged home but is bedbound. He had gangrene on his toes, and I could not fully examine him using video,” Dr. Shin recalled. “It was tricky to find the house, but a very large Trump sign was very helpful in locating it. It was a good visit: He was happy to see me, and I was happy to see that he was doing okay at home.”

“I need to remind myself that supporting Mr. Trump does not always mean that my patient supports Mr. Trump’s view on the pandemic and the race issues in our country,” Dr. Shin added.

The Washington-based internist said he also tells himself that, even if his patients refuse to follow his strong advice regarding pandemic precautions, it does not mean he has failed as a doctor.

“I need to continue to educate patients about the dangers of COVID infection but cannot be angry if they don’t choose to follow my recommendations,” he noted.

Dr. Fincher says her close connection with patients has allowed her to smooth over politically charged claims about the pandemic in the town of Thomson, Georgia, with a population 6,800.

“I have a sense that, even though we may differ in our understanding of some basic facts, they appreciate what I say since we have a long-term relationship built on trust,” she said. This kind of trust, Dr. Fincher suggested, may be more common than in urban areas where there’s a larger supply of physicians, and patients don’t see the same doctors for long periods of time.

“It’s more meaningful when it comes from me, rather than doctors who are [new to patients] every year when their employer changes their insurance,” she noted.

These include struggling with seeing patients virtually and treating patients who have politicized the virus. Additionally, the pandemic has exposed rural practices to greater financial difficulties.

Before the pandemic some rurally based primary care physicians were already working through big challenges, such as having few local medical colleagues to consult and working in small practices with lean budgets. In fact, data gathered by the National Rural Health Association showed that there are only 40 primary care physicians per 100,000 patients in rural regions, compared with 53 in urban areas – and the number of physicians overall is 13 per 10,000 in rural areas, compared with 31 in cities.

In the prepandemic world, for some doctors, the challenges were balanced by the benefits of practicing in these sparsely populated communities with scenic, low-traffic roads. Some perks of practicing in rural areas touted by doctors included having a fast commute, being able to swim in a lake near the office before work, having a low cost of living, and feeling like they are making a difference in their communities as they treat generations of the families they see around town.

But today, new hurdles to practicing medicine in rural America created by the COVID-19 pandemic have caused the hardships to feel heavier than the joys at times for some physicians interviewed by MDedge.

Many independent rural practices in need of assistance were not able to get much from the federal Provider Relief Funds, said John M. Westfall, MD, who is director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care, in an interview.

“Rural primary care doctors function independently or in smaller critical access hospitals and community health centers,” said Dr. Westfall, who previously practiced family medicine in a small town in Colorado. “Many of these have much less financial reserves so are at risk of cutbacks and closure.”

Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, an internist based in a tiny Georgia community along the highway between Atlanta and Augusta, said her small practice works on really thin margins and doesn’t have much cushion. At the beginning of the pandemic, all visits were down, and her practice operated at a loss. To help, Dr. Fincher and her colleagues applied for funding from the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) through the CARES Act.

“COVID-19 has had a tremendous impact especially on primary care practices. We live and die by volume. … Our volume in mid-March to mid-May really dropped dramatically,” explained Dr. Fincher, who is also president of the American College of Physicians. “The PPP sustained us for 2 months, enabling us to pay our staff and to remain open and get us up and running on telehealth.”

Starting up telemedicine

Experiencing spotty or no access to broadband Internet is nothing new to rural physicians, but having this problem interfere with their ability to provide care to patients is.

As much of the American health system rapidly embraced telehealth during the pandemic, obtaining access to high-speed Internet has been a major challenge for rural patients, noted Dr. Westfall.

“Some practices were able to quickly adopt some telehealth capacity with phone and video. Changes in payment for telehealth helped. But in some rural communities there was not adequate Internet bandwidth for quality video connections. And some patients did not have the means for high-speed video connections,” Dr. Westfall said.

Indeed, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, 63% of rural Americans say they can access the Internet through a broadband connection at home, compared with 75% and 79% in suburban and urban areas, respectively.

In the Appalachian town of Zanesville, Ohio, for example, family physician Shelly L. Dunmyer, MD, and her colleagues discovered that many patients don’t have Internet access at home. Dr. Fincher has to go to the office to conduct telehealth visits because her own Internet access at home is unpredictable. As for patients, it may take 15 minutes for them to work out technical glitches and find good Internet reception, said Dr. Fincher. For internist Y. Ki Shin, MD, who practices in the coastal town of Montesano in Washington state, about 25% of his practice’s telehealth visits must be conducted by phone because of limitations on video, such as lack of high-speed access.

But telephone visits are often insufficient replacements for appointments via video, according to several rural physicians interviewed for this piece.

“Telehealth can be frustrating at times due to connectivity issues which can be difficult at times in the rural areas,” said Dr. Fincher. “In order for telehealth to be reasonably helpful to patients and physicians to care for people with chronic problems, the patients must have things like blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and scales to address problems like hypertension, diabetes myelitis, and congestive heart failure.”

“If you have the audio and video and the data from these devices, you’re good. If you don’t have these data, and/or don’t have the video you just can’t provide good care,” she explained.

Dr. Dunmyer and her colleagues at Medical Home Primary Care Center in Zanesville, Ohio, found a way to get around the problem of patients not being able to access Internet to participate in video visits from their homes. This involved having her patients drive into her practice’s parking lot to participate in modified telehealth visits. Staffers gave iPads to patients in their cars, and Dr. Dunmyer conducted visits from her office, about 50 yards away.

“We were even doing Medicare wellness visits: Instead of asking them to get up and move around the room, we would sit at the window and wave at them, ask them to get out, walk around the car. We were able to check mobility and all kinds of things that we’d normally do in the office,” Dr. Dunmyer explained in an interview.

The family physician noted that her practice is now conducting fewer parking lot visits since her office is allowing in-person appointments, but that they’re still an option for her patients.

Treating political adversaries

Some rural physicians have experienced strained relationships with patients for reasons other than technology – stark differences in opinion over the pandemic itself. Certain patients are following President Trump’s lead and questioning everything from the pandemic death toll to preventive measures recommended by scientists and medical experts, physicians interviewed by MDedge said.

Patients everywhere share these viewpoints, of course, but research and election results confirm that rural areas are more receptive to conservative viewpoints. In 2018, a Pew Research Center survey reported that rural and urban areas are “becoming more polarized politically,” and “rural areas tend to have a higher concentration of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.” For example, 40% of rural respondents reported “very warm” or “somewhat warm” feelings toward Donald Trump, compared with just 19% in urban areas.

Dr. Shin has struggled to cope with patients who want to argue about pandemic safety precautions like wearing masks and seem to question whether systemic racism exists.

“We are seeing a lot more people who feel that this pandemic is not real, that it’s a political and not-true infection,” he said in an interview. “We’ve had patients who were angry at us because we made them wear masks, and some were demanding hydroxychloroquine and wanted to have an argument because we’re not going to prescribe it for them.”

In one situation, which he found especially disturbing, Dr. Shin had to leave the exam room because a patient wouldn’t stop challenging him regarding the pandemic. Things have gotten so bad that Dr. Shin has even questioned whether he wants to continue his long career in his small town because of local political attitudes such as opposition to mask-wearing and social distancing.

“Mr. Trump’s misinformation on this pandemic made my job much more difficult. As a minority, I feel less safe in my community than ever,” said Dr. Shin, who described himself as Asian American.

Despite these new stressors, Dr. Shin has experienced some joyful moments while practicing medicine in the pandemic.

He said a recent home visit to a patient who had been hospitalized for over 3 months and nearly died helped him put political disputes with his patients into perspective.

“He was discharged home but is bedbound. He had gangrene on his toes, and I could not fully examine him using video,” Dr. Shin recalled. “It was tricky to find the house, but a very large Trump sign was very helpful in locating it. It was a good visit: He was happy to see me, and I was happy to see that he was doing okay at home.”

“I need to remind myself that supporting Mr. Trump does not always mean that my patient supports Mr. Trump’s view on the pandemic and the race issues in our country,” Dr. Shin added.

The Washington-based internist said he also tells himself that, even if his patients refuse to follow his strong advice regarding pandemic precautions, it does not mean he has failed as a doctor.

“I need to continue to educate patients about the dangers of COVID infection but cannot be angry if they don’t choose to follow my recommendations,” he noted.

Dr. Fincher says her close connection with patients has allowed her to smooth over politically charged claims about the pandemic in the town of Thomson, Georgia, with a population 6,800.

“I have a sense that, even though we may differ in our understanding of some basic facts, they appreciate what I say since we have a long-term relationship built on trust,” she said. This kind of trust, Dr. Fincher suggested, may be more common than in urban areas where there’s a larger supply of physicians, and patients don’t see the same doctors for long periods of time.

“It’s more meaningful when it comes from me, rather than doctors who are [new to patients] every year when their employer changes their insurance,” she noted.

These include struggling with seeing patients virtually and treating patients who have politicized the virus. Additionally, the pandemic has exposed rural practices to greater financial difficulties.

Before the pandemic some rurally based primary care physicians were already working through big challenges, such as having few local medical colleagues to consult and working in small practices with lean budgets. In fact, data gathered by the National Rural Health Association showed that there are only 40 primary care physicians per 100,000 patients in rural regions, compared with 53 in urban areas – and the number of physicians overall is 13 per 10,000 in rural areas, compared with 31 in cities.

In the prepandemic world, for some doctors, the challenges were balanced by the benefits of practicing in these sparsely populated communities with scenic, low-traffic roads. Some perks of practicing in rural areas touted by doctors included having a fast commute, being able to swim in a lake near the office before work, having a low cost of living, and feeling like they are making a difference in their communities as they treat generations of the families they see around town.

But today, new hurdles to practicing medicine in rural America created by the COVID-19 pandemic have caused the hardships to feel heavier than the joys at times for some physicians interviewed by MDedge.

Many independent rural practices in need of assistance were not able to get much from the federal Provider Relief Funds, said John M. Westfall, MD, who is director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care, in an interview.

“Rural primary care doctors function independently or in smaller critical access hospitals and community health centers,” said Dr. Westfall, who previously practiced family medicine in a small town in Colorado. “Many of these have much less financial reserves so are at risk of cutbacks and closure.”

Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, an internist based in a tiny Georgia community along the highway between Atlanta and Augusta, said her small practice works on really thin margins and doesn’t have much cushion. At the beginning of the pandemic, all visits were down, and her practice operated at a loss. To help, Dr. Fincher and her colleagues applied for funding from the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) through the CARES Act.

“COVID-19 has had a tremendous impact especially on primary care practices. We live and die by volume. … Our volume in mid-March to mid-May really dropped dramatically,” explained Dr. Fincher, who is also president of the American College of Physicians. “The PPP sustained us for 2 months, enabling us to pay our staff and to remain open and get us up and running on telehealth.”

Starting up telemedicine

Experiencing spotty or no access to broadband Internet is nothing new to rural physicians, but having this problem interfere with their ability to provide care to patients is.

As much of the American health system rapidly embraced telehealth during the pandemic, obtaining access to high-speed Internet has been a major challenge for rural patients, noted Dr. Westfall.

“Some practices were able to quickly adopt some telehealth capacity with phone and video. Changes in payment for telehealth helped. But in some rural communities there was not adequate Internet bandwidth for quality video connections. And some patients did not have the means for high-speed video connections,” Dr. Westfall said.

Indeed, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, 63% of rural Americans say they can access the Internet through a broadband connection at home, compared with 75% and 79% in suburban and urban areas, respectively.

In the Appalachian town of Zanesville, Ohio, for example, family physician Shelly L. Dunmyer, MD, and her colleagues discovered that many patients don’t have Internet access at home. Dr. Fincher has to go to the office to conduct telehealth visits because her own Internet access at home is unpredictable. As for patients, it may take 15 minutes for them to work out technical glitches and find good Internet reception, said Dr. Fincher. For internist Y. Ki Shin, MD, who practices in the coastal town of Montesano in Washington state, about 25% of his practice’s telehealth visits must be conducted by phone because of limitations on video, such as lack of high-speed access.

But telephone visits are often insufficient replacements for appointments via video, according to several rural physicians interviewed for this piece.

“Telehealth can be frustrating at times due to connectivity issues which can be difficult at times in the rural areas,” said Dr. Fincher. “In order for telehealth to be reasonably helpful to patients and physicians to care for people with chronic problems, the patients must have things like blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and scales to address problems like hypertension, diabetes myelitis, and congestive heart failure.”

“If you have the audio and video and the data from these devices, you’re good. If you don’t have these data, and/or don’t have the video you just can’t provide good care,” she explained.

Dr. Dunmyer and her colleagues at Medical Home Primary Care Center in Zanesville, Ohio, found a way to get around the problem of patients not being able to access Internet to participate in video visits from their homes. This involved having her patients drive into her practice’s parking lot to participate in modified telehealth visits. Staffers gave iPads to patients in their cars, and Dr. Dunmyer conducted visits from her office, about 50 yards away.

“We were even doing Medicare wellness visits: Instead of asking them to get up and move around the room, we would sit at the window and wave at them, ask them to get out, walk around the car. We were able to check mobility and all kinds of things that we’d normally do in the office,” Dr. Dunmyer explained in an interview.

The family physician noted that her practice is now conducting fewer parking lot visits since her office is allowing in-person appointments, but that they’re still an option for her patients.

Treating political adversaries

Some rural physicians have experienced strained relationships with patients for reasons other than technology – stark differences in opinion over the pandemic itself. Certain patients are following President Trump’s lead and questioning everything from the pandemic death toll to preventive measures recommended by scientists and medical experts, physicians interviewed by MDedge said.

Patients everywhere share these viewpoints, of course, but research and election results confirm that rural areas are more receptive to conservative viewpoints. In 2018, a Pew Research Center survey reported that rural and urban areas are “becoming more polarized politically,” and “rural areas tend to have a higher concentration of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.” For example, 40% of rural respondents reported “very warm” or “somewhat warm” feelings toward Donald Trump, compared with just 19% in urban areas.

Dr. Shin has struggled to cope with patients who want to argue about pandemic safety precautions like wearing masks and seem to question whether systemic racism exists.

“We are seeing a lot more people who feel that this pandemic is not real, that it’s a political and not-true infection,” he said in an interview. “We’ve had patients who were angry at us because we made them wear masks, and some were demanding hydroxychloroquine and wanted to have an argument because we’re not going to prescribe it for them.”

In one situation, which he found especially disturbing, Dr. Shin had to leave the exam room because a patient wouldn’t stop challenging him regarding the pandemic. Things have gotten so bad that Dr. Shin has even questioned whether he wants to continue his long career in his small town because of local political attitudes such as opposition to mask-wearing and social distancing.

“Mr. Trump’s misinformation on this pandemic made my job much more difficult. As a minority, I feel less safe in my community than ever,” said Dr. Shin, who described himself as Asian American.

Despite these new stressors, Dr. Shin has experienced some joyful moments while practicing medicine in the pandemic.

He said a recent home visit to a patient who had been hospitalized for over 3 months and nearly died helped him put political disputes with his patients into perspective.

“He was discharged home but is bedbound. He had gangrene on his toes, and I could not fully examine him using video,” Dr. Shin recalled. “It was tricky to find the house, but a very large Trump sign was very helpful in locating it. It was a good visit: He was happy to see me, and I was happy to see that he was doing okay at home.”

“I need to remind myself that supporting Mr. Trump does not always mean that my patient supports Mr. Trump’s view on the pandemic and the race issues in our country,” Dr. Shin added.

The Washington-based internist said he also tells himself that, even if his patients refuse to follow his strong advice regarding pandemic precautions, it does not mean he has failed as a doctor.

“I need to continue to educate patients about the dangers of COVID infection but cannot be angry if they don’t choose to follow my recommendations,” he noted.

Dr. Fincher says her close connection with patients has allowed her to smooth over politically charged claims about the pandemic in the town of Thomson, Georgia, with a population 6,800.

“I have a sense that, even though we may differ in our understanding of some basic facts, they appreciate what I say since we have a long-term relationship built on trust,” she said. This kind of trust, Dr. Fincher suggested, may be more common than in urban areas where there’s a larger supply of physicians, and patients don’t see the same doctors for long periods of time.

“It’s more meaningful when it comes from me, rather than doctors who are [new to patients] every year when their employer changes their insurance,” she noted.

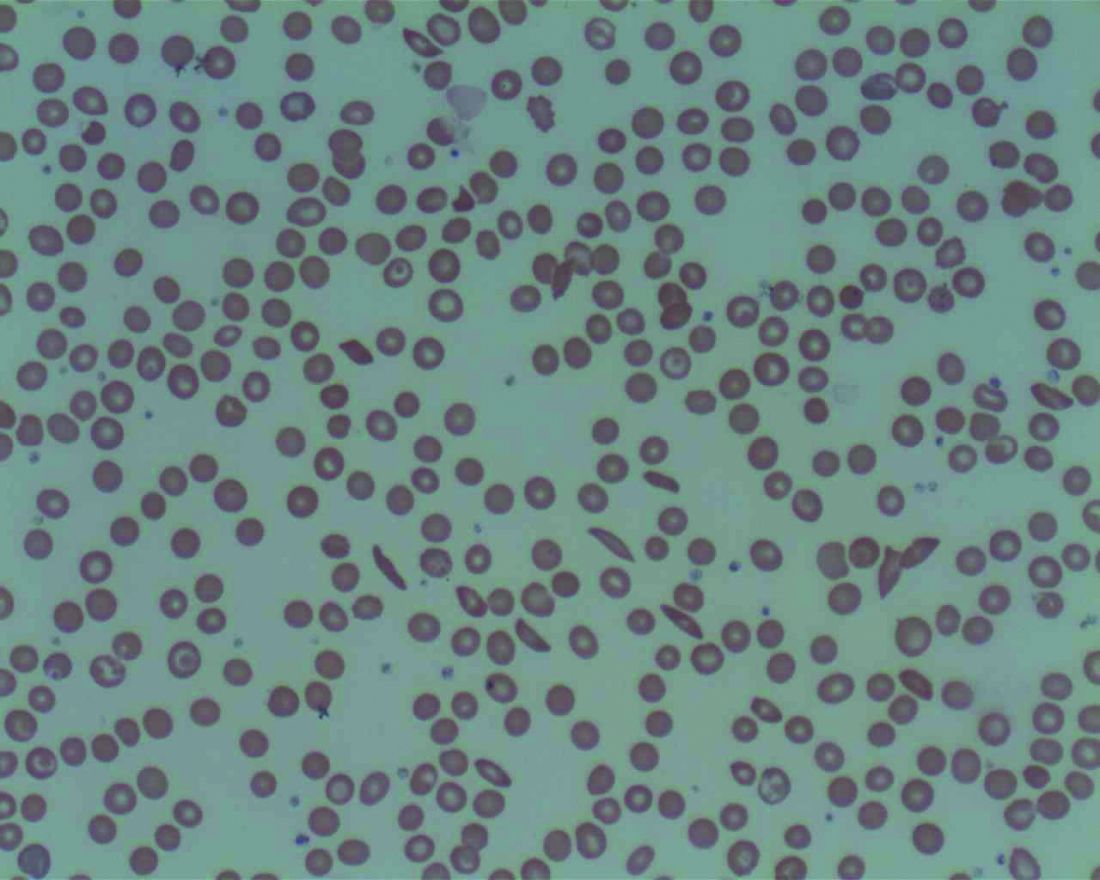

Landmark sickle cell report targets massive failures, calls for action

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine have just released a 522-page report, but it’s not the usual compilation of guidelines for treatment of a disease. Instead, the authors of “Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action” argue in stark terms that the American society has colossally failed individuals living with sickle cell disease (SCD), who are mostly Black or Brown. A dramatic overhaul of the country’s medical and societal priorities is needed to turn things around to improve health and longevity among this rare disease population.

The findings from the NASEM report are explicit: “There has been substantial success in increasing the survival of children with SCD, but this success had not been translated to similar success as they become adults.” One factor posited to contribute to the slow progress in the improvement of quality and quantity of life for adults living with this disease is the fact that “SCD is largely a disease of African Americans, and as such exists in a context of racial discrimination, health and other societal disparities, mistrust of the health care system, and the effects of poverty.” The report also cites the substantial evidence that those with SCD may receive poorer quality of care.

The report’s 14 authors were made up of an ad hoc committee formed at the request of the Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of Minority Health. The office asked NASEM to convene the committee to develop a strategic plan and blueprint for the United States and others regarding SCD.

The NASEM SCD committee members “realized that we can’t address the medical components of SCD if we don’t explore societal issues and why it’s been so hard to get good care for people with sickle cell disease,” hematologist and report coauthor Ifeyinwa (Ify) Osunkwo, MD, professor of medicine and pediatrics at Atrium Health and director of the Sickle Cell Disease Enterprise, Levine Cancer Institute, Charlotte, N.C., said in an interview. Dr. Osunkwo is also the medical editor of Hematology News.

“After almost a year of meetings and digging into the background and history of SCD care, we came out with very comprehensive summary of where we were and where we want to be,” she said. “The report provides short-, intermediate- and long-term recommendations and identifies which entity and organization should be responsible for implementing them.”

The report authors, led by pediatrician and committee chair Marie Clare McCormick, MD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, stated that about 100,000 people in the United States and millions worldwide live with SCD. The disease kills more than 700 people per year in the United States, and treatment costs an estimated $2 billion a year.

When judged by disability-adjusted life-years lost – a measurement of expected healthy years of life without an illness – the impact of SCD on individuals is estimated to be greater than a long list of other diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, breast cancer, type 1 diabetes, and AIDS/HIV, the report noted.

“The health care needs of individuals living with SCD have been neglected by the U.S. and global health care systems, causing them and their families to suffer,” the report said. “Many of the complications that afflict individuals with SCD, particularly pain, are invisible. Pain is only diagnosed by self-reports, and in SCD there are few to no external indicators of the pain experience. Nevertheless, the pain can be excruciatingly severe and requires treatment with strong analgesics.”

There’s even more misery to the story of SCD, the report said, and Dr. Osunkwo agreed. “It’s not just about pain. These individuals suffer from multiple organ-system complications that are physical but also psychological and societal. They experience a lot of disparities in every aspect of their lives. You’re sick, so then you can’t get a job or health insurance, you can’t get Social Security benefits. You can’t get the type of health care you need nor can you access the other forms of support you need and often you are judged as a drug seeker for complaining of pain or repeatedly seeking acute care for unresolved pain.”

Multiple factors exacerbate the experience of people living with SCD in America, the report said. “Because of systemic racism, unconscious bias, and the stigma associated with the diagnosis, the disease brings with it a much broader burden.”

Dr. Osunkwo put it this way: “SCD is a disease that mostly affects Brown and Black people, and that gets layered into the whole discrimination issues that Black and Brown people face compounding the health burden from their disease.”

The report added that “the SCD community has developed a significant lack of trust in the health care system due to the nearly universal stigma and lack of belief in their reports of pain, a lack of trust that has been further reinforced by historical events, such as the Tuskegee experiment.”

The report highlighted research that finds that Blacks “are more likely to receive a lower quality of pain management than white patients and may be perceived as having drug-seeking behavior.”

The report also identified gaps in treatment, noting that “many SCD complications are not restricted to any one organ system, and the impact of the disease on [quality of life] can be profound but hard to define and compartmentalize.”

Dr. Osunkwo said medical professionals often fail to understand the full breadth of the disease. “There’s no particular look to SCD. When you have cancer, you come in, and you look like you’re sick because you’re bald. Everyone clues into that cancer look and knows it’s lethal, that you’re may likely die early. We don’t have that “look that generates empathy” for SCD, and people don’t understand the burden on those affected. They don’t understand or appreciate that SCD shortens your lifespan as well ... that people living with SCD die 3 decades earlier than their ethnically matched peers. Also, SCD is associated with a lot of pain, and pain and the treatment of pain with opioids makes people [health care providers] uncomfortable unless it’s cancer pain.”

She added: “People also assume that, if it’s not pain, it’s not SCD even though SCD can cause leg ulcers and blood clots and even affect the tonsils, or lead to a stroke. When a disease complexity is too difficult for providers to understand, they either avoid it or don’t do anything for the patient.”

Screening and surveillance for SCD and sickle cell trait is insufficient, the report said, and the potential cost of missed childhood cases is large. Detecting the condition at birth allows the implementation of appropriate comprehensive care and treatment to prevent early death from infections and strokes. As the authors noted, “tremendous strides have been made in the past few decades in the care of children with SCD, which have led to almost all children in high-income settings surviving to adulthood.” However, there remains gaps in care coordination and follow-up of babies screened at birth and even bigger gaps in translating these life span gains to adults particularly around the period of transition from pediatrics to adult care when there appears to be a spike in morbidity and mortality.

The report summarized current treatments for SCD and noted “an influx of pipeline products” after years of little progress and identifies “a need for targeted SCD therapies that address the underlying cause of the disease.”

While treatment recommendations exist, Dr. Osunkwo said, “the evidence for them is very poor and many SCD complications have no evidence-based guidelines for providers to follow. We need more research to provide high quality evidence to make guidelines for SCD treatment stronger and more robust.”

In its final section, the report offers a “strategic plan and blueprint for sickle cell disease action.” It offers several strategies to achieve the vision of “long healthy productive lives for those living with sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait”:

- Establish and fund a research agenda to inform effective programs and policies across the life span.

- Implement efforts to advance understanding of the full impact of sickle cell trait on individuals and society.

- Address barriers to accessing current and pipeline therapies for SCD.

- Improve SCD awareness and strengthen advocacy efforts.

- Increase the number of qualified health professionals providing SCD care.

- Strengthen the evidence base for interventions and disease management and implement widespread efforts to monitor the quality of SCD care.

- Establish organized systems of care assuring both clinical and nonclinical supportive services to all persons living with SCD.

- Establish a national system to collect and link data to characterize the burden of disease, outcomes, and the needs of those with SCD across the life span.

“Right now, the average lifespan for SCD is in the mid-40s to mid-50s,” Dr. Osunkwo said. “That’s a horrible statistic. Even if we just take up half of these recommendations, people will live longer with SCD, and they’ll be more productive and contribute more to society. If we value a cancer life the same as a sickle cell life, we’ll be halfway across the finish line. But the stigma of SCD being a Black and Brown problem is going to be the hardest to confront as it requires a systemic change in our culture as a country and a health care system.”

Still, she said, the commissioning of the report “shows that there is a desire to understand the issue in better detail and try to mitigate it.”

Dr. Osunkwo and Dr. McCormick had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2020.

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine have just released a 522-page report, but it’s not the usual compilation of guidelines for treatment of a disease. Instead, the authors of “Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action” argue in stark terms that the American society has colossally failed individuals living with sickle cell disease (SCD), who are mostly Black or Brown. A dramatic overhaul of the country’s medical and societal priorities is needed to turn things around to improve health and longevity among this rare disease population.

The findings from the NASEM report are explicit: “There has been substantial success in increasing the survival of children with SCD, but this success had not been translated to similar success as they become adults.” One factor posited to contribute to the slow progress in the improvement of quality and quantity of life for adults living with this disease is the fact that “SCD is largely a disease of African Americans, and as such exists in a context of racial discrimination, health and other societal disparities, mistrust of the health care system, and the effects of poverty.” The report also cites the substantial evidence that those with SCD may receive poorer quality of care.

The report’s 14 authors were made up of an ad hoc committee formed at the request of the Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of Minority Health. The office asked NASEM to convene the committee to develop a strategic plan and blueprint for the United States and others regarding SCD.

The NASEM SCD committee members “realized that we can’t address the medical components of SCD if we don’t explore societal issues and why it’s been so hard to get good care for people with sickle cell disease,” hematologist and report coauthor Ifeyinwa (Ify) Osunkwo, MD, professor of medicine and pediatrics at Atrium Health and director of the Sickle Cell Disease Enterprise, Levine Cancer Institute, Charlotte, N.C., said in an interview. Dr. Osunkwo is also the medical editor of Hematology News.

“After almost a year of meetings and digging into the background and history of SCD care, we came out with very comprehensive summary of where we were and where we want to be,” she said. “The report provides short-, intermediate- and long-term recommendations and identifies which entity and organization should be responsible for implementing them.”

The report authors, led by pediatrician and committee chair Marie Clare McCormick, MD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, stated that about 100,000 people in the United States and millions worldwide live with SCD. The disease kills more than 700 people per year in the United States, and treatment costs an estimated $2 billion a year.

When judged by disability-adjusted life-years lost – a measurement of expected healthy years of life without an illness – the impact of SCD on individuals is estimated to be greater than a long list of other diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, breast cancer, type 1 diabetes, and AIDS/HIV, the report noted.

“The health care needs of individuals living with SCD have been neglected by the U.S. and global health care systems, causing them and their families to suffer,” the report said. “Many of the complications that afflict individuals with SCD, particularly pain, are invisible. Pain is only diagnosed by self-reports, and in SCD there are few to no external indicators of the pain experience. Nevertheless, the pain can be excruciatingly severe and requires treatment with strong analgesics.”

There’s even more misery to the story of SCD, the report said, and Dr. Osunkwo agreed. “It’s not just about pain. These individuals suffer from multiple organ-system complications that are physical but also psychological and societal. They experience a lot of disparities in every aspect of their lives. You’re sick, so then you can’t get a job or health insurance, you can’t get Social Security benefits. You can’t get the type of health care you need nor can you access the other forms of support you need and often you are judged as a drug seeker for complaining of pain or repeatedly seeking acute care for unresolved pain.”

Multiple factors exacerbate the experience of people living with SCD in America, the report said. “Because of systemic racism, unconscious bias, and the stigma associated with the diagnosis, the disease brings with it a much broader burden.”

Dr. Osunkwo put it this way: “SCD is a disease that mostly affects Brown and Black people, and that gets layered into the whole discrimination issues that Black and Brown people face compounding the health burden from their disease.”

The report added that “the SCD community has developed a significant lack of trust in the health care system due to the nearly universal stigma and lack of belief in their reports of pain, a lack of trust that has been further reinforced by historical events, such as the Tuskegee experiment.”

The report highlighted research that finds that Blacks “are more likely to receive a lower quality of pain management than white patients and may be perceived as having drug-seeking behavior.”

The report also identified gaps in treatment, noting that “many SCD complications are not restricted to any one organ system, and the impact of the disease on [quality of life] can be profound but hard to define and compartmentalize.”

Dr. Osunkwo said medical professionals often fail to understand the full breadth of the disease. “There’s no particular look to SCD. When you have cancer, you come in, and you look like you’re sick because you’re bald. Everyone clues into that cancer look and knows it’s lethal, that you’re may likely die early. We don’t have that “look that generates empathy” for SCD, and people don’t understand the burden on those affected. They don’t understand or appreciate that SCD shortens your lifespan as well ... that people living with SCD die 3 decades earlier than their ethnically matched peers. Also, SCD is associated with a lot of pain, and pain and the treatment of pain with opioids makes people [health care providers] uncomfortable unless it’s cancer pain.”

She added: “People also assume that, if it’s not pain, it’s not SCD even though SCD can cause leg ulcers and blood clots and even affect the tonsils, or lead to a stroke. When a disease complexity is too difficult for providers to understand, they either avoid it or don’t do anything for the patient.”

Screening and surveillance for SCD and sickle cell trait is insufficient, the report said, and the potential cost of missed childhood cases is large. Detecting the condition at birth allows the implementation of appropriate comprehensive care and treatment to prevent early death from infections and strokes. As the authors noted, “tremendous strides have been made in the past few decades in the care of children with SCD, which have led to almost all children in high-income settings surviving to adulthood.” However, there remains gaps in care coordination and follow-up of babies screened at birth and even bigger gaps in translating these life span gains to adults particularly around the period of transition from pediatrics to adult care when there appears to be a spike in morbidity and mortality.

The report summarized current treatments for SCD and noted “an influx of pipeline products” after years of little progress and identifies “a need for targeted SCD therapies that address the underlying cause of the disease.”

While treatment recommendations exist, Dr. Osunkwo said, “the evidence for them is very poor and many SCD complications have no evidence-based guidelines for providers to follow. We need more research to provide high quality evidence to make guidelines for SCD treatment stronger and more robust.”

In its final section, the report offers a “strategic plan and blueprint for sickle cell disease action.” It offers several strategies to achieve the vision of “long healthy productive lives for those living with sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait”:

- Establish and fund a research agenda to inform effective programs and policies across the life span.

- Implement efforts to advance understanding of the full impact of sickle cell trait on individuals and society.

- Address barriers to accessing current and pipeline therapies for SCD.

- Improve SCD awareness and strengthen advocacy efforts.

- Increase the number of qualified health professionals providing SCD care.

- Strengthen the evidence base for interventions and disease management and implement widespread efforts to monitor the quality of SCD care.

- Establish organized systems of care assuring both clinical and nonclinical supportive services to all persons living with SCD.

- Establish a national system to collect and link data to characterize the burden of disease, outcomes, and the needs of those with SCD across the life span.

“Right now, the average lifespan for SCD is in the mid-40s to mid-50s,” Dr. Osunkwo said. “That’s a horrible statistic. Even if we just take up half of these recommendations, people will live longer with SCD, and they’ll be more productive and contribute more to society. If we value a cancer life the same as a sickle cell life, we’ll be halfway across the finish line. But the stigma of SCD being a Black and Brown problem is going to be the hardest to confront as it requires a systemic change in our culture as a country and a health care system.”

Still, she said, the commissioning of the report “shows that there is a desire to understand the issue in better detail and try to mitigate it.”

Dr. Osunkwo and Dr. McCormick had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2020.

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine have just released a 522-page report, but it’s not the usual compilation of guidelines for treatment of a disease. Instead, the authors of “Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action” argue in stark terms that the American society has colossally failed individuals living with sickle cell disease (SCD), who are mostly Black or Brown. A dramatic overhaul of the country’s medical and societal priorities is needed to turn things around to improve health and longevity among this rare disease population.

The findings from the NASEM report are explicit: “There has been substantial success in increasing the survival of children with SCD, but this success had not been translated to similar success as they become adults.” One factor posited to contribute to the slow progress in the improvement of quality and quantity of life for adults living with this disease is the fact that “SCD is largely a disease of African Americans, and as such exists in a context of racial discrimination, health and other societal disparities, mistrust of the health care system, and the effects of poverty.” The report also cites the substantial evidence that those with SCD may receive poorer quality of care.

The report’s 14 authors were made up of an ad hoc committee formed at the request of the Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of Minority Health. The office asked NASEM to convene the committee to develop a strategic plan and blueprint for the United States and others regarding SCD.

The NASEM SCD committee members “realized that we can’t address the medical components of SCD if we don’t explore societal issues and why it’s been so hard to get good care for people with sickle cell disease,” hematologist and report coauthor Ifeyinwa (Ify) Osunkwo, MD, professor of medicine and pediatrics at Atrium Health and director of the Sickle Cell Disease Enterprise, Levine Cancer Institute, Charlotte, N.C., said in an interview. Dr. Osunkwo is also the medical editor of Hematology News.

“After almost a year of meetings and digging into the background and history of SCD care, we came out with very comprehensive summary of where we were and where we want to be,” she said. “The report provides short-, intermediate- and long-term recommendations and identifies which entity and organization should be responsible for implementing them.”

The report authors, led by pediatrician and committee chair Marie Clare McCormick, MD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, stated that about 100,000 people in the United States and millions worldwide live with SCD. The disease kills more than 700 people per year in the United States, and treatment costs an estimated $2 billion a year.

When judged by disability-adjusted life-years lost – a measurement of expected healthy years of life without an illness – the impact of SCD on individuals is estimated to be greater than a long list of other diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, breast cancer, type 1 diabetes, and AIDS/HIV, the report noted.

“The health care needs of individuals living with SCD have been neglected by the U.S. and global health care systems, causing them and their families to suffer,” the report said. “Many of the complications that afflict individuals with SCD, particularly pain, are invisible. Pain is only diagnosed by self-reports, and in SCD there are few to no external indicators of the pain experience. Nevertheless, the pain can be excruciatingly severe and requires treatment with strong analgesics.”

There’s even more misery to the story of SCD, the report said, and Dr. Osunkwo agreed. “It’s not just about pain. These individuals suffer from multiple organ-system complications that are physical but also psychological and societal. They experience a lot of disparities in every aspect of their lives. You’re sick, so then you can’t get a job or health insurance, you can’t get Social Security benefits. You can’t get the type of health care you need nor can you access the other forms of support you need and often you are judged as a drug seeker for complaining of pain or repeatedly seeking acute care for unresolved pain.”

Multiple factors exacerbate the experience of people living with SCD in America, the report said. “Because of systemic racism, unconscious bias, and the stigma associated with the diagnosis, the disease brings with it a much broader burden.”

Dr. Osunkwo put it this way: “SCD is a disease that mostly affects Brown and Black people, and that gets layered into the whole discrimination issues that Black and Brown people face compounding the health burden from their disease.”

The report added that “the SCD community has developed a significant lack of trust in the health care system due to the nearly universal stigma and lack of belief in their reports of pain, a lack of trust that has been further reinforced by historical events, such as the Tuskegee experiment.”

The report highlighted research that finds that Blacks “are more likely to receive a lower quality of pain management than white patients and may be perceived as having drug-seeking behavior.”

The report also identified gaps in treatment, noting that “many SCD complications are not restricted to any one organ system, and the impact of the disease on [quality of life] can be profound but hard to define and compartmentalize.”

Dr. Osunkwo said medical professionals often fail to understand the full breadth of the disease. “There’s no particular look to SCD. When you have cancer, you come in, and you look like you’re sick because you’re bald. Everyone clues into that cancer look and knows it’s lethal, that you’re may likely die early. We don’t have that “look that generates empathy” for SCD, and people don’t understand the burden on those affected. They don’t understand or appreciate that SCD shortens your lifespan as well ... that people living with SCD die 3 decades earlier than their ethnically matched peers. Also, SCD is associated with a lot of pain, and pain and the treatment of pain with opioids makes people [health care providers] uncomfortable unless it’s cancer pain.”

She added: “People also assume that, if it’s not pain, it’s not SCD even though SCD can cause leg ulcers and blood clots and even affect the tonsils, or lead to a stroke. When a disease complexity is too difficult for providers to understand, they either avoid it or don’t do anything for the patient.”

Screening and surveillance for SCD and sickle cell trait is insufficient, the report said, and the potential cost of missed childhood cases is large. Detecting the condition at birth allows the implementation of appropriate comprehensive care and treatment to prevent early death from infections and strokes. As the authors noted, “tremendous strides have been made in the past few decades in the care of children with SCD, which have led to almost all children in high-income settings surviving to adulthood.” However, there remains gaps in care coordination and follow-up of babies screened at birth and even bigger gaps in translating these life span gains to adults particularly around the period of transition from pediatrics to adult care when there appears to be a spike in morbidity and mortality.

The report summarized current treatments for SCD and noted “an influx of pipeline products” after years of little progress and identifies “a need for targeted SCD therapies that address the underlying cause of the disease.”

While treatment recommendations exist, Dr. Osunkwo said, “the evidence for them is very poor and many SCD complications have no evidence-based guidelines for providers to follow. We need more research to provide high quality evidence to make guidelines for SCD treatment stronger and more robust.”

In its final section, the report offers a “strategic plan and blueprint for sickle cell disease action.” It offers several strategies to achieve the vision of “long healthy productive lives for those living with sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait”:

- Establish and fund a research agenda to inform effective programs and policies across the life span.

- Implement efforts to advance understanding of the full impact of sickle cell trait on individuals and society.

- Address barriers to accessing current and pipeline therapies for SCD.

- Improve SCD awareness and strengthen advocacy efforts.

- Increase the number of qualified health professionals providing SCD care.

- Strengthen the evidence base for interventions and disease management and implement widespread efforts to monitor the quality of SCD care.

- Establish organized systems of care assuring both clinical and nonclinical supportive services to all persons living with SCD.

- Establish a national system to collect and link data to characterize the burden of disease, outcomes, and the needs of those with SCD across the life span.

“Right now, the average lifespan for SCD is in the mid-40s to mid-50s,” Dr. Osunkwo said. “That’s a horrible statistic. Even if we just take up half of these recommendations, people will live longer with SCD, and they’ll be more productive and contribute more to society. If we value a cancer life the same as a sickle cell life, we’ll be halfway across the finish line. But the stigma of SCD being a Black and Brown problem is going to be the hardest to confront as it requires a systemic change in our culture as a country and a health care system.”

Still, she said, the commissioning of the report “shows that there is a desire to understand the issue in better detail and try to mitigate it.”

Dr. Osunkwo and Dr. McCormick had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2020.

J&J’s one-shot COVID-19 vaccine advances to phase 3 testing

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which is aiding Johnson & Johnson with development, described this in a news release as the fourth phase 3 clinical trial of evaluating an investigational vaccine for coronavirus disease.

This NIAID tally tracks products likely to be presented soon for Food and Drug Administration approval. (The World Health Organization’s COVID vaccine tracker lists nine candidates as having reached this stage, including products developed in Russia and China.)

As many as 60,000 volunteers will be enrolled in the trial, with about 215 clinical research sites expected to participate, NIAID said. The vaccine will be tested in the United States and abroad.

The start of this test, known as the ENSEMBLE trial, follows positive results from a Phase 1/2a clinical study, which involved a single vaccination. The results of this study have been submitted to medRxiv and are set to be published online imminently.

New Brunswick, N.J–based J&J said it intends to offer the vaccine on “a not-for-profit basis for emergency pandemic use.” If testing proceeds well, J&J might seek an emergency use clearance for the vaccine, which could possibly allow the first batches to be made available in early 2021.

J&J’s vaccine is unusual in that it will be tested based on a single dose, while other advanced candidates have been tested in two-dose regimens.

J&J on Wednesday also released the study protocol for its phase 3 test. The developers of the other late-stage COVID vaccine candidates also have done this, as reported by Medscape Medical News. Because of the great interest in the COVID vaccine, the American Medical Association had last month asked the FDA to keep physicians informed of their COVID-19 vaccine review process.

Trials and tribulations

One of these experimental COVID vaccines already has had a setback in phase 3 testing, which is a fairly routine occurrence in drug development. But with a pandemic still causing deaths and disrupting lives around the world, there has been intense interest in each step of the effort to develop a COVID vaccine.

AstraZeneca PLC earlier this month announced a temporary cessation of all their coronavirus vaccine trials to investigate an “unexplained illness” that arose in a participant, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

On September 12, AstraZeneca announced that clinical trials for the AZD1222, which it developed with Oxford University, had resumed in the United Kingdom. On Wednesday, CNBC said Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar told the news station that AstraZeneca’s late-stage coronavirus vaccine trial in the United States remains on hold until safety concerns are resolved, a critical issue with all the fast-track COVID vaccines now being tested.

“Look at the AstraZeneca program, phase 3 clinical trial, a lot of hope. [A] single serious adverse event report in the United Kingdom, global shutdown, and [a] hold of the clinical trials,” Mr. Azar told CNBC.

The New York Times has reported on concerns stemming from serious neurologic illnesses in two participants, both women, who received AstraZeneca’s experimental vaccine in Britain.

The Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee on Wednesday separately held a hearing with the leaders of the FDA and the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, allowing an airing of lawmakers’ concerns about a potential rush to approve a COVID vaccine.

Details of J&J trial

The J&J trial is designed primarily to determine if the investigational vaccine can prevent moderate to severe COVID-19 after a single dose. It also is designed to examine whether the vaccine can prevent COVID-19 requiring medical intervention and if the vaccine can prevent milder cases of COVID-19 and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, NIAID said.

Principal investigators for the phase 3 trial of the J & J vaccine are Paul A. Goepfert, MD, director of the Alabama Vaccine Research Clinic at the University of Alabama in Birmingham; Beatriz Grinsztejn, MD, PhD, director of the Laboratory of Clinical Research on HIV/AIDS at the Evandro Chagas National Institute of Infectious Diseases-Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; and Glenda E. Gray, MBBCh, president and chief executive officer of the South African Medical Research Council and coprincipal investigator of the HIV Vaccine Trials Network.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which is aiding Johnson & Johnson with development, described this in a news release as the fourth phase 3 clinical trial of evaluating an investigational vaccine for coronavirus disease.

This NIAID tally tracks products likely to be presented soon for Food and Drug Administration approval. (The World Health Organization’s COVID vaccine tracker lists nine candidates as having reached this stage, including products developed in Russia and China.)

As many as 60,000 volunteers will be enrolled in the trial, with about 215 clinical research sites expected to participate, NIAID said. The vaccine will be tested in the United States and abroad.

The start of this test, known as the ENSEMBLE trial, follows positive results from a Phase 1/2a clinical study, which involved a single vaccination. The results of this study have been submitted to medRxiv and are set to be published online imminently.

New Brunswick, N.J–based J&J said it intends to offer the vaccine on “a not-for-profit basis for emergency pandemic use.” If testing proceeds well, J&J might seek an emergency use clearance for the vaccine, which could possibly allow the first batches to be made available in early 2021.

J&J’s vaccine is unusual in that it will be tested based on a single dose, while other advanced candidates have been tested in two-dose regimens.

J&J on Wednesday also released the study protocol for its phase 3 test. The developers of the other late-stage COVID vaccine candidates also have done this, as reported by Medscape Medical News. Because of the great interest in the COVID vaccine, the American Medical Association had last month asked the FDA to keep physicians informed of their COVID-19 vaccine review process.

Trials and tribulations

One of these experimental COVID vaccines already has had a setback in phase 3 testing, which is a fairly routine occurrence in drug development. But with a pandemic still causing deaths and disrupting lives around the world, there has been intense interest in each step of the effort to develop a COVID vaccine.

AstraZeneca PLC earlier this month announced a temporary cessation of all their coronavirus vaccine trials to investigate an “unexplained illness” that arose in a participant, as reported by Medscape Medical News.