User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Breakthrough Blood Test for Colorectal Cancer Gets Green Light

The FDA on July 29 approved the test, called Shield, which can accurately detect tumors in the colon or rectum about 87% of the time when the cancer is in treatable early stages. The approval was announced July 29 by the test’s maker, Guardant Health, and comes just months after promising clinical trial results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Colorectal cancer is among the most common types of cancer diagnosed in the United States each year, along with being one of the leading causes of cancer deaths. The condition is treatable in early stages, but about 1 in 3 people don’t stay up to date on regular screenings, which should begin at age 45.

The simplicity of a blood test could make it more likely for people to be screened for and, ultimately, survive the disease. Other primary screening options include feces-based tests or colonoscopy. The 5-year survival rate for colorectal cancer is 64%.

While highly accurate at detecting DNA shed by tumors during treatable stages of colorectal cancer, the Shield test was not as effective at detecting precancerous areas of tissue, which are typically removed after being detected.

In its news release, Guardant Health officials said they anticipate the test to be covered under Medicare. The out-of-pocket cost for people whose insurance does not cover the test has not yet been announced. The test is expected to be available by next week, The New York Times reported.

If someone’s Shield test comes back positive, the person would then get more tests to confirm the result. Shield was shown in trials to have a 10% false positive rate.

“I was in for a routine physical, and my doctor asked when I had my last colonoscopy,” said John Gormly, a 77-year-old business executive in Newport Beach, California, according to a Guardant Health news release. “I said it’s been a long time, so he offered to give me the Shield blood test. A few days later, the result came back positive, so he referred me for a colonoscopy. It turned out I had stage II colon cancer. The tumor was removed, and I recovered very quickly. Thank God I had taken that blood test.”

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

The FDA on July 29 approved the test, called Shield, which can accurately detect tumors in the colon or rectum about 87% of the time when the cancer is in treatable early stages. The approval was announced July 29 by the test’s maker, Guardant Health, and comes just months after promising clinical trial results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Colorectal cancer is among the most common types of cancer diagnosed in the United States each year, along with being one of the leading causes of cancer deaths. The condition is treatable in early stages, but about 1 in 3 people don’t stay up to date on regular screenings, which should begin at age 45.

The simplicity of a blood test could make it more likely for people to be screened for and, ultimately, survive the disease. Other primary screening options include feces-based tests or colonoscopy. The 5-year survival rate for colorectal cancer is 64%.

While highly accurate at detecting DNA shed by tumors during treatable stages of colorectal cancer, the Shield test was not as effective at detecting precancerous areas of tissue, which are typically removed after being detected.

In its news release, Guardant Health officials said they anticipate the test to be covered under Medicare. The out-of-pocket cost for people whose insurance does not cover the test has not yet been announced. The test is expected to be available by next week, The New York Times reported.

If someone’s Shield test comes back positive, the person would then get more tests to confirm the result. Shield was shown in trials to have a 10% false positive rate.

“I was in for a routine physical, and my doctor asked when I had my last colonoscopy,” said John Gormly, a 77-year-old business executive in Newport Beach, California, according to a Guardant Health news release. “I said it’s been a long time, so he offered to give me the Shield blood test. A few days later, the result came back positive, so he referred me for a colonoscopy. It turned out I had stage II colon cancer. The tumor was removed, and I recovered very quickly. Thank God I had taken that blood test.”

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

The FDA on July 29 approved the test, called Shield, which can accurately detect tumors in the colon or rectum about 87% of the time when the cancer is in treatable early stages. The approval was announced July 29 by the test’s maker, Guardant Health, and comes just months after promising clinical trial results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Colorectal cancer is among the most common types of cancer diagnosed in the United States each year, along with being one of the leading causes of cancer deaths. The condition is treatable in early stages, but about 1 in 3 people don’t stay up to date on regular screenings, which should begin at age 45.

The simplicity of a blood test could make it more likely for people to be screened for and, ultimately, survive the disease. Other primary screening options include feces-based tests or colonoscopy. The 5-year survival rate for colorectal cancer is 64%.

While highly accurate at detecting DNA shed by tumors during treatable stages of colorectal cancer, the Shield test was not as effective at detecting precancerous areas of tissue, which are typically removed after being detected.

In its news release, Guardant Health officials said they anticipate the test to be covered under Medicare. The out-of-pocket cost for people whose insurance does not cover the test has not yet been announced. The test is expected to be available by next week, The New York Times reported.

If someone’s Shield test comes back positive, the person would then get more tests to confirm the result. Shield was shown in trials to have a 10% false positive rate.

“I was in for a routine physical, and my doctor asked when I had my last colonoscopy,” said John Gormly, a 77-year-old business executive in Newport Beach, California, according to a Guardant Health news release. “I said it’s been a long time, so he offered to give me the Shield blood test. A few days later, the result came back positive, so he referred me for a colonoscopy. It turned out I had stage II colon cancer. The tumor was removed, and I recovered very quickly. Thank God I had taken that blood test.”

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

FDA Calls AstraZeneca’s NSCLC Trial Design Into Question

The trial in question, AEGEAN, investigated perioperative durvalumab for resectable NSCLC tumors across 802 patients. Patients without EGFR or ALK mutations were randomly assigned to receive durvalumab before surgery alongside platinum-containing chemotherapy and after surgery for a year as monotherapy or to receive chemotherapy and surgery alone.

Patients receiving durvalumab demonstrated better event-free survival at 1 year (73.4% vs 64.5% without durvalumab) and a better pathologic complete response rate (17.2% vs 4.3% without). Currently, AstraZeneca is seeking to add the indication for durvalumab to those the agent already has.

However, at the July 25 ODAC meeting, the committee explained that the AEGEAN trial design makes it impossible to tell whether patients benefited from durvalumab before surgery, after it, or at both points.

Mounting evidence, including from AstraZeneca’s own studies, suggests that the benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as durvalumab, comes before surgery. That means prescribing durvalumab after surgery could be exposing patients to serious side effects and financial toxicity, with potentially no clinical benefit, “magnifying the risk of potential overtreatment,” the committee cautioned.

When AEGEAN was being designed in 2018, FDA requested that AstraZeneca address the uncertainty surrounding when to use durvalumab by including separate neoadjuvant and adjuvant arms, or at least an arm where patients were treated with neoadjuvant durvalumab alone to compare with treatment both before and after surgery.

The company didn’t follow through and, during the July 25 meeting, the committee wanted answers. “Why did you not comply with this?” asked ODAC committee acting chair Daniel Spratt, MD, a radiation oncologist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

AstraZeneca personnel explained that doing so would have required many more subjects, made the trial more expensive, and added about 2 years to AEGEAN.

One speaker noted that the company, which makes more than $4 billion a year on durvalumab, would have taken about 2 days to recoup that added cost. Others wondered whether the motive was to sell durvalumab for as long as possible across a patient’s course of treatment.

Perhaps the biggest reason the company ignored the request is that “it wasn’t our understanding at that time that this was a barrier to approval,” an AstraZeneca regulatory affairs specialist said.

To this end, the agency asked its advisory panel to vote on whether it should require — instead of simply request, as it did with AstraZeneca — companies to prove that patients need immunotherapy both before and after surgery in resectable NSCLC.

The 11-member panel voted unanimously that it should make this a requirement, and several members said it should do so in other cancers as well.

However, when the agency asked whether durvalumab’s resectable NSCLC approval should be delayed until AstraZeneca conducts a trial to answer the neoadjuvant vs adjuvant question, the panel members didn’t think so.

The consensus was that because AEGEAN showed a decent benefit, patients and physicians should have it as an option, and approval shouldn’t be delayed. The panel said that the bigger question about the benefit of maintenance therapy should be left to future studies.

FDA usually follows the advice of its advisory panels.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The trial in question, AEGEAN, investigated perioperative durvalumab for resectable NSCLC tumors across 802 patients. Patients without EGFR or ALK mutations were randomly assigned to receive durvalumab before surgery alongside platinum-containing chemotherapy and after surgery for a year as monotherapy or to receive chemotherapy and surgery alone.

Patients receiving durvalumab demonstrated better event-free survival at 1 year (73.4% vs 64.5% without durvalumab) and a better pathologic complete response rate (17.2% vs 4.3% without). Currently, AstraZeneca is seeking to add the indication for durvalumab to those the agent already has.

However, at the July 25 ODAC meeting, the committee explained that the AEGEAN trial design makes it impossible to tell whether patients benefited from durvalumab before surgery, after it, or at both points.

Mounting evidence, including from AstraZeneca’s own studies, suggests that the benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as durvalumab, comes before surgery. That means prescribing durvalumab after surgery could be exposing patients to serious side effects and financial toxicity, with potentially no clinical benefit, “magnifying the risk of potential overtreatment,” the committee cautioned.

When AEGEAN was being designed in 2018, FDA requested that AstraZeneca address the uncertainty surrounding when to use durvalumab by including separate neoadjuvant and adjuvant arms, or at least an arm where patients were treated with neoadjuvant durvalumab alone to compare with treatment both before and after surgery.

The company didn’t follow through and, during the July 25 meeting, the committee wanted answers. “Why did you not comply with this?” asked ODAC committee acting chair Daniel Spratt, MD, a radiation oncologist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

AstraZeneca personnel explained that doing so would have required many more subjects, made the trial more expensive, and added about 2 years to AEGEAN.

One speaker noted that the company, which makes more than $4 billion a year on durvalumab, would have taken about 2 days to recoup that added cost. Others wondered whether the motive was to sell durvalumab for as long as possible across a patient’s course of treatment.

Perhaps the biggest reason the company ignored the request is that “it wasn’t our understanding at that time that this was a barrier to approval,” an AstraZeneca regulatory affairs specialist said.

To this end, the agency asked its advisory panel to vote on whether it should require — instead of simply request, as it did with AstraZeneca — companies to prove that patients need immunotherapy both before and after surgery in resectable NSCLC.

The 11-member panel voted unanimously that it should make this a requirement, and several members said it should do so in other cancers as well.

However, when the agency asked whether durvalumab’s resectable NSCLC approval should be delayed until AstraZeneca conducts a trial to answer the neoadjuvant vs adjuvant question, the panel members didn’t think so.

The consensus was that because AEGEAN showed a decent benefit, patients and physicians should have it as an option, and approval shouldn’t be delayed. The panel said that the bigger question about the benefit of maintenance therapy should be left to future studies.

FDA usually follows the advice of its advisory panels.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The trial in question, AEGEAN, investigated perioperative durvalumab for resectable NSCLC tumors across 802 patients. Patients without EGFR or ALK mutations were randomly assigned to receive durvalumab before surgery alongside platinum-containing chemotherapy and after surgery for a year as monotherapy or to receive chemotherapy and surgery alone.

Patients receiving durvalumab demonstrated better event-free survival at 1 year (73.4% vs 64.5% without durvalumab) and a better pathologic complete response rate (17.2% vs 4.3% without). Currently, AstraZeneca is seeking to add the indication for durvalumab to those the agent already has.

However, at the July 25 ODAC meeting, the committee explained that the AEGEAN trial design makes it impossible to tell whether patients benefited from durvalumab before surgery, after it, or at both points.

Mounting evidence, including from AstraZeneca’s own studies, suggests that the benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as durvalumab, comes before surgery. That means prescribing durvalumab after surgery could be exposing patients to serious side effects and financial toxicity, with potentially no clinical benefit, “magnifying the risk of potential overtreatment,” the committee cautioned.

When AEGEAN was being designed in 2018, FDA requested that AstraZeneca address the uncertainty surrounding when to use durvalumab by including separate neoadjuvant and adjuvant arms, or at least an arm where patients were treated with neoadjuvant durvalumab alone to compare with treatment both before and after surgery.

The company didn’t follow through and, during the July 25 meeting, the committee wanted answers. “Why did you not comply with this?” asked ODAC committee acting chair Daniel Spratt, MD, a radiation oncologist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

AstraZeneca personnel explained that doing so would have required many more subjects, made the trial more expensive, and added about 2 years to AEGEAN.

One speaker noted that the company, which makes more than $4 billion a year on durvalumab, would have taken about 2 days to recoup that added cost. Others wondered whether the motive was to sell durvalumab for as long as possible across a patient’s course of treatment.

Perhaps the biggest reason the company ignored the request is that “it wasn’t our understanding at that time that this was a barrier to approval,” an AstraZeneca regulatory affairs specialist said.

To this end, the agency asked its advisory panel to vote on whether it should require — instead of simply request, as it did with AstraZeneca — companies to prove that patients need immunotherapy both before and after surgery in resectable NSCLC.

The 11-member panel voted unanimously that it should make this a requirement, and several members said it should do so in other cancers as well.

However, when the agency asked whether durvalumab’s resectable NSCLC approval should be delayed until AstraZeneca conducts a trial to answer the neoadjuvant vs adjuvant question, the panel members didn’t think so.

The consensus was that because AEGEAN showed a decent benefit, patients and physicians should have it as an option, and approval shouldn’t be delayed. The panel said that the bigger question about the benefit of maintenance therapy should be left to future studies.

FDA usually follows the advice of its advisory panels.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Which Patients With Early TNBC Can Avoid Chemotherapy?

TOPLINE:

which suggest that stromal TILs could be a useful biomarker to optimize treatment decisions in this patient population.

METHODOLOGY:

- The absolute benefit of chemotherapy remains unclear among patients with stage I TNBC. High levels of stromal TILs, a promising biomarker, have been linked to better survival in patients with TNBC, but data focused on stage I disease are lacking.

- In the current analysis, researchers identified a cohort of 1041 women (mean age at diagnosis, 64.4 years) from the Netherlands Cancer Registry with stage I TNBC who had an available TIL score and had undergone a lumpectomy or a mastectomy but had not received neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Patients’ clinical data were matched to their corresponding pathologic data provided by the Dutch Pathology Registry, and a pathologist blinded to outcomes scored stromal TIL levels according to the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group guidelines.

- The primary endpoint was breast cancer–specific survival at prespecified stromal TIL cutoffs of 30%, 50%, and 75%. Secondary outcomes included specific survival by pathologic tumor stage and overall survival.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 8.6% of women had a pT1a tumor, 38.7% had a pT1b tumor, and 52.6% had a pT1c tumor. In the cohort, 25.6% of patients had stromal TIL levels of 30% or higher, 19.5% had levels of 50% or higher, and 13.5% had levels of 75% or higher.

- Over a median follow-up of 11.4 years, 335 patients died, 107 (32%) of whom died from breast cancer. Patients with smaller tumors (pT1abNO) had better survival outcomes than those with larger tumors (pT1cNO) — a 10-year breast cancer–specific survival of 92% vs 86%, respectively.

- In the overall cohort, stromal TIL levels of 30% or higher were associated with better breast cancer–specific survival than those with stromal TIL levels below 30% (96% vs 87%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.45). Stromal TIL levels of 50% or greater were also associated with better 10-year breast cancer–specific survival than those with levels below 50% (92% vs 88%; HR, 0.59). A similar pattern was observed for stromal TIL levels and overall survival.

- In patients with pT1c tumors, the 10-year breast cancer–specific survival among those with stromal TIL levels of 30% or higher was 95% vs 83% for levels below the 30% cutoff (HR, 0.24). Similarly, the 10-year breast cancer–specific survival for those in the 50% or higher group was 95% vs 84% for levels below that cutoff (HR, 0.27). The 10-year breast cancer–specific survival improved to 98% among patients with stromal TIL levels of 75% or higher (HR, 0.09).

IN PRACTICE:

The results supported the establishment of “treatment-optimization clinical trials in patients with stage I TNBC, using [stromal] TIL level as an integral biomarker to prospectively confirm the observed excellent survival when neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy is not administered,” the authors wrote. Assessing stromal TILs is also “inexpensive,” the authors added.

SOURCE:

The research, conducted by Marleen Kok, MD, PhD, Department of Medical Oncology, the Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, and colleagues, was published online in JAMA Oncology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted that the study was limited by its observational nature. The patients were drawn from a larger cohort, about half of whom received adjuvant chemotherapy, and the patients who did not receive chemotherapy may have had favorable tumor characteristics. There were also no data on BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline mutation status and recurrences and/or distant metastases. The database did not include data on patient ethnicity because most Dutch patients were White.

DISCLOSURES:

Research at the Netherlands Cancer Institute was supported by institutional grants from the Dutch Cancer Society and the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Dr. Kok declared financial relationships with several organizations including Gilead and Domain Therapeutics, as well as institutional grants from AstraZeneca, BMS, and Roche. Other authors also declared numerous financial relationships for themselves and their institutions with pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

which suggest that stromal TILs could be a useful biomarker to optimize treatment decisions in this patient population.

METHODOLOGY:

- The absolute benefit of chemotherapy remains unclear among patients with stage I TNBC. High levels of stromal TILs, a promising biomarker, have been linked to better survival in patients with TNBC, but data focused on stage I disease are lacking.

- In the current analysis, researchers identified a cohort of 1041 women (mean age at diagnosis, 64.4 years) from the Netherlands Cancer Registry with stage I TNBC who had an available TIL score and had undergone a lumpectomy or a mastectomy but had not received neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Patients’ clinical data were matched to their corresponding pathologic data provided by the Dutch Pathology Registry, and a pathologist blinded to outcomes scored stromal TIL levels according to the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group guidelines.

- The primary endpoint was breast cancer–specific survival at prespecified stromal TIL cutoffs of 30%, 50%, and 75%. Secondary outcomes included specific survival by pathologic tumor stage and overall survival.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 8.6% of women had a pT1a tumor, 38.7% had a pT1b tumor, and 52.6% had a pT1c tumor. In the cohort, 25.6% of patients had stromal TIL levels of 30% or higher, 19.5% had levels of 50% or higher, and 13.5% had levels of 75% or higher.

- Over a median follow-up of 11.4 years, 335 patients died, 107 (32%) of whom died from breast cancer. Patients with smaller tumors (pT1abNO) had better survival outcomes than those with larger tumors (pT1cNO) — a 10-year breast cancer–specific survival of 92% vs 86%, respectively.

- In the overall cohort, stromal TIL levels of 30% or higher were associated with better breast cancer–specific survival than those with stromal TIL levels below 30% (96% vs 87%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.45). Stromal TIL levels of 50% or greater were also associated with better 10-year breast cancer–specific survival than those with levels below 50% (92% vs 88%; HR, 0.59). A similar pattern was observed for stromal TIL levels and overall survival.

- In patients with pT1c tumors, the 10-year breast cancer–specific survival among those with stromal TIL levels of 30% or higher was 95% vs 83% for levels below the 30% cutoff (HR, 0.24). Similarly, the 10-year breast cancer–specific survival for those in the 50% or higher group was 95% vs 84% for levels below that cutoff (HR, 0.27). The 10-year breast cancer–specific survival improved to 98% among patients with stromal TIL levels of 75% or higher (HR, 0.09).

IN PRACTICE:

The results supported the establishment of “treatment-optimization clinical trials in patients with stage I TNBC, using [stromal] TIL level as an integral biomarker to prospectively confirm the observed excellent survival when neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy is not administered,” the authors wrote. Assessing stromal TILs is also “inexpensive,” the authors added.

SOURCE:

The research, conducted by Marleen Kok, MD, PhD, Department of Medical Oncology, the Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, and colleagues, was published online in JAMA Oncology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted that the study was limited by its observational nature. The patients were drawn from a larger cohort, about half of whom received adjuvant chemotherapy, and the patients who did not receive chemotherapy may have had favorable tumor characteristics. There were also no data on BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline mutation status and recurrences and/or distant metastases. The database did not include data on patient ethnicity because most Dutch patients were White.

DISCLOSURES:

Research at the Netherlands Cancer Institute was supported by institutional grants from the Dutch Cancer Society and the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Dr. Kok declared financial relationships with several organizations including Gilead and Domain Therapeutics, as well as institutional grants from AstraZeneca, BMS, and Roche. Other authors also declared numerous financial relationships for themselves and their institutions with pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

which suggest that stromal TILs could be a useful biomarker to optimize treatment decisions in this patient population.

METHODOLOGY:

- The absolute benefit of chemotherapy remains unclear among patients with stage I TNBC. High levels of stromal TILs, a promising biomarker, have been linked to better survival in patients with TNBC, but data focused on stage I disease are lacking.

- In the current analysis, researchers identified a cohort of 1041 women (mean age at diagnosis, 64.4 years) from the Netherlands Cancer Registry with stage I TNBC who had an available TIL score and had undergone a lumpectomy or a mastectomy but had not received neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Patients’ clinical data were matched to their corresponding pathologic data provided by the Dutch Pathology Registry, and a pathologist blinded to outcomes scored stromal TIL levels according to the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group guidelines.

- The primary endpoint was breast cancer–specific survival at prespecified stromal TIL cutoffs of 30%, 50%, and 75%. Secondary outcomes included specific survival by pathologic tumor stage and overall survival.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 8.6% of women had a pT1a tumor, 38.7% had a pT1b tumor, and 52.6% had a pT1c tumor. In the cohort, 25.6% of patients had stromal TIL levels of 30% or higher, 19.5% had levels of 50% or higher, and 13.5% had levels of 75% or higher.

- Over a median follow-up of 11.4 years, 335 patients died, 107 (32%) of whom died from breast cancer. Patients with smaller tumors (pT1abNO) had better survival outcomes than those with larger tumors (pT1cNO) — a 10-year breast cancer–specific survival of 92% vs 86%, respectively.

- In the overall cohort, stromal TIL levels of 30% or higher were associated with better breast cancer–specific survival than those with stromal TIL levels below 30% (96% vs 87%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.45). Stromal TIL levels of 50% or greater were also associated with better 10-year breast cancer–specific survival than those with levels below 50% (92% vs 88%; HR, 0.59). A similar pattern was observed for stromal TIL levels and overall survival.

- In patients with pT1c tumors, the 10-year breast cancer–specific survival among those with stromal TIL levels of 30% or higher was 95% vs 83% for levels below the 30% cutoff (HR, 0.24). Similarly, the 10-year breast cancer–specific survival for those in the 50% or higher group was 95% vs 84% for levels below that cutoff (HR, 0.27). The 10-year breast cancer–specific survival improved to 98% among patients with stromal TIL levels of 75% or higher (HR, 0.09).

IN PRACTICE:

The results supported the establishment of “treatment-optimization clinical trials in patients with stage I TNBC, using [stromal] TIL level as an integral biomarker to prospectively confirm the observed excellent survival when neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy is not administered,” the authors wrote. Assessing stromal TILs is also “inexpensive,” the authors added.

SOURCE:

The research, conducted by Marleen Kok, MD, PhD, Department of Medical Oncology, the Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, and colleagues, was published online in JAMA Oncology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted that the study was limited by its observational nature. The patients were drawn from a larger cohort, about half of whom received adjuvant chemotherapy, and the patients who did not receive chemotherapy may have had favorable tumor characteristics. There were also no data on BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline mutation status and recurrences and/or distant metastases. The database did not include data on patient ethnicity because most Dutch patients were White.

DISCLOSURES:

Research at the Netherlands Cancer Institute was supported by institutional grants from the Dutch Cancer Society and the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Dr. Kok declared financial relationships with several organizations including Gilead and Domain Therapeutics, as well as institutional grants from AstraZeneca, BMS, and Roche. Other authors also declared numerous financial relationships for themselves and their institutions with pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Baseline Bone Pain Predicts Survival in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Prostate cancer often metastasizes to the bones, leading to pain and a reduced quality of life. While the relationship between bone pain and overall survival in metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer is well-documented, its impact in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer is less clear.

- Researchers conducted a post hoc secondary analysis using data from the SWOG-1216 phase 3 randomized clinical trial, which included 1279 men diagnosed with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer from 248 centers across the United States. Patients had received androgen deprivation therapy either with orteronel or bicalutamide.

- Among the 1197 patients (median age, 67.6 years) with data on bone pain included in the secondary analysis, 301 (23.5%) reported bone pain at baseline.

- The primary outcome was overall survival; secondary outcomes included progression-free survival and prostate-specific antigen response.

TAKEAWAY:

- The median overall survival for patients with baseline bone pain was 3.9 years compared with not reached (95% CI, 6.6 years to not reached) for those without bone pain at a median follow-up of 4 years (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.66; P < .001).

- Similarly, patients with bone pain had a shorter progression-free survival vs those without bone pain (median, 1.3 years vs 3.7 years; aHR, 1.46; P < .001).

- The complete prostate-specific antigen response rate at 7 months was also lower for patients with baseline bone pain (46.3% vs 66.3%; P < .001).

IN PRACTICE:

Patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer “with baseline bone pain had worse survival outcomes than those without baseline bone pain,” the authors wrote. “These results highlight the need to consider bone pain in prognostic modeling, treatment selection, patient monitoring, and follow-up and suggest prioritizing these patients for clinical trials and immediate systemic treatment initiation.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Georges Gebrael, MD, Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The post hoc design may introduce bias. Orteronel failed to receive regulatory approval, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the study did not account for synchronous vs metachronous disease status, a known established prognostic factor.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute and Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Takeda Oncology Company). Several authors declared ties with various sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Prostate cancer often metastasizes to the bones, leading to pain and a reduced quality of life. While the relationship between bone pain and overall survival in metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer is well-documented, its impact in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer is less clear.

- Researchers conducted a post hoc secondary analysis using data from the SWOG-1216 phase 3 randomized clinical trial, which included 1279 men diagnosed with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer from 248 centers across the United States. Patients had received androgen deprivation therapy either with orteronel or bicalutamide.

- Among the 1197 patients (median age, 67.6 years) with data on bone pain included in the secondary analysis, 301 (23.5%) reported bone pain at baseline.

- The primary outcome was overall survival; secondary outcomes included progression-free survival and prostate-specific antigen response.

TAKEAWAY:

- The median overall survival for patients with baseline bone pain was 3.9 years compared with not reached (95% CI, 6.6 years to not reached) for those without bone pain at a median follow-up of 4 years (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.66; P < .001).

- Similarly, patients with bone pain had a shorter progression-free survival vs those without bone pain (median, 1.3 years vs 3.7 years; aHR, 1.46; P < .001).

- The complete prostate-specific antigen response rate at 7 months was also lower for patients with baseline bone pain (46.3% vs 66.3%; P < .001).

IN PRACTICE:

Patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer “with baseline bone pain had worse survival outcomes than those without baseline bone pain,” the authors wrote. “These results highlight the need to consider bone pain in prognostic modeling, treatment selection, patient monitoring, and follow-up and suggest prioritizing these patients for clinical trials and immediate systemic treatment initiation.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Georges Gebrael, MD, Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The post hoc design may introduce bias. Orteronel failed to receive regulatory approval, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the study did not account for synchronous vs metachronous disease status, a known established prognostic factor.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute and Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Takeda Oncology Company). Several authors declared ties with various sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Prostate cancer often metastasizes to the bones, leading to pain and a reduced quality of life. While the relationship between bone pain and overall survival in metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer is well-documented, its impact in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer is less clear.

- Researchers conducted a post hoc secondary analysis using data from the SWOG-1216 phase 3 randomized clinical trial, which included 1279 men diagnosed with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer from 248 centers across the United States. Patients had received androgen deprivation therapy either with orteronel or bicalutamide.

- Among the 1197 patients (median age, 67.6 years) with data on bone pain included in the secondary analysis, 301 (23.5%) reported bone pain at baseline.

- The primary outcome was overall survival; secondary outcomes included progression-free survival and prostate-specific antigen response.

TAKEAWAY:

- The median overall survival for patients with baseline bone pain was 3.9 years compared with not reached (95% CI, 6.6 years to not reached) for those without bone pain at a median follow-up of 4 years (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.66; P < .001).

- Similarly, patients with bone pain had a shorter progression-free survival vs those without bone pain (median, 1.3 years vs 3.7 years; aHR, 1.46; P < .001).

- The complete prostate-specific antigen response rate at 7 months was also lower for patients with baseline bone pain (46.3% vs 66.3%; P < .001).

IN PRACTICE:

Patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer “with baseline bone pain had worse survival outcomes than those without baseline bone pain,” the authors wrote. “These results highlight the need to consider bone pain in prognostic modeling, treatment selection, patient monitoring, and follow-up and suggest prioritizing these patients for clinical trials and immediate systemic treatment initiation.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Georges Gebrael, MD, Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The post hoc design may introduce bias. Orteronel failed to receive regulatory approval, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the study did not account for synchronous vs metachronous disease status, a known established prognostic factor.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute and Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Takeda Oncology Company). Several authors declared ties with various sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fed Worker Health Plans Ban Maximizers and Copay Accumulators: Why Not for the Rest of the US?

The escalating costs of medications and the prevalence of medical bankruptcy in our country have drawn criticism from governments, regulators, and the media. Federal and state governments are exploring various strategies to mitigate this issue, including the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) for drug price negotiations and the establishment of state Pharmaceutical Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs). However, it’s uncertain whether these measures will effectively reduce patients’ medication expenses, given the tendency of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to favor more expensive drugs on their formularies and the implementation challenges faced by PDABs.

The question then arises: How can we promptly assist patients, especially those with multiple chronic conditions, in affording their healthcare? Many of these patients are enrolled in high-deductible plans and struggle to cover all their medical and pharmacy costs.

A significant obstacle to healthcare affordability emerged in 2018 with the introduction of Copay Accumulator Programs by PBMs. These programs prevent patients from applying manufacturer copay cards toward their deductible and maximum out-of-pocket (OOP) costs. The impact of these policies has been devastating, leading to decreased adherence to medications and delayed necessary medical procedures, such as colonoscopies. Copay accumulators do nothing to address the high cost of medical care. They merely shift the burden from insurance companies to patients.

There is a direct solution to help patients, particularly those burdened with high pharmacy bills, afford their medical care. It would be that all payments from patients, including manufacturer copay cards, count toward their deductible and maximum OOP costs. This should apply regardless of whether the insurance plan is fully funded or a self-insured employer plan. This would be an immediate step toward making healthcare more affordable for patients.

Copay Accumulator Programs

How did these detrimental policies, which have been proven to harm patients, originate? It’s interesting that health insurance policies for federal employees do not allow these programs and yet the federal government has done little to protect its citizens from these egregious policies. More on that later.

In 2018, insurance companies and PBMs conceived an idea to introduce what they called copay accumulator adjustment programs. These programs would prevent the use of manufacturer copay cards from counting toward patient deductibles or OOP maximums. They justified this by arguing that manufacturer copay cards encouraged patients to opt for higher-priced brand drugs when lower-cost generics were available.

However, data from IQVIA contradicts this claim. An analysis of copay card usage from 2013 to 2017 revealed that a mere 0.4% of these cards were used for brand-name drugs that had already lost their exclusivity. This indicates that the vast majority of copay cards were not being used to purchase more expensive brand-name drugs when cheaper, generic alternatives were available.

Another argument put forth by one of the large PBMs was that patients with high deductibles don’t have enough “skin in the game” due to their low premiums, and therefore don’t deserve to have their deductible covered by a copay card. This raises the question, “Does a patient with hemophilia or systemic lupus who can’t afford a low deductible plan not have ‘skin in the game’? Is that a fair assessment?” It’s disconcerting to see a multibillion-dollar company dictating who deserves to have their deductible covered. These policies clearly disproportionately harm patients with chronic illnesses, especially those with high deductibles. As a result, many organizations have labeled these policies as discriminatory.

Following the implementation of accumulator programs in 2018 and 2019, many patients were unaware that their copay cards weren’t contributing toward their deductibles. They were taken aback when specialty pharmacies informed them of owing substantial amounts because of unmet deductibles. Consequently, patients discontinued their medications, leading to disease progression and increased costs. The only downside for health insurers and PBMs was the negative publicity associated with patients losing medication access.

Maximizer Programs

By the end of 2019, the three major PBMs had devised a strategy to keep patients on their medication throughout the year, without counting copay cards toward the deductible, and found a way to profit more from these cards, sometimes quadrupling their value. This was the birth of the maximizer programs.

Maximizers exploit a “loophole” in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA defines Essential Healthcare Benefits (EHB); anything not listed as an EHB is deemed “non-essential.” As a result, neither personal payments nor copay cards count toward deductibles or OOP maximums. Patients were informed that neither their own money nor manufacturer copay cards would count toward their deductible/OOP max.

One of my patients was warned that without enrolling in the maximizer program through SaveOnSP (owned by Express Scripts), she would bear the full cost of the drug, and nothing would count toward her OOP max. Frightened, she enrolled and surrendered her manufacturer copay card to SaveOnSP. Maximizers pocket the maximum value of the copay card, even if it exceeds the insurance plan’s yearly cost share by threefold or more. To do this legally, PBMs increase the patient’s original cost share amount during the plan year to match the value of the manufacturer copay card.

Combating These Programs

Nineteen states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico have outlawed copay accumulators in health plans under state jurisdiction. I personally testified in Louisiana, leading to a ban in our state. CSRO’s award-winning map tool can show if your state has passed the ban on copay accumulator programs. However, many states have not passed bans on copay accumulators and self-insured employer groups, which fall under the Department of Labor and not state regulation, are still unaffected. There is also proposed federal legislation, the “Help Ensure Lower Patient Copays Act,” that would prohibit the use of copay accumulators in exchange plans. Despite having bipartisan support, it is having a hard time getting across the finish line in Congress.

In 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued a rule prohibiting accumulator programs in all plans if the product was a brand name without a generic alternative. Unfortunately, this rule was rescinded in 2021, allowing copay accumulators even if a lower-cost generic was available.

In a positive turn of events, the US District Court of the District of Columbia overturned the 2021 rule in late 2023, reinstating the 2020 ban on copay accumulators. However, HHS has yet to enforce this ban.

Double Standard

Why is it that our federal government refrains from enforcing bans on copay accumulators for the American public, yet the US Office of Personnel Management (OPM) in its 2024 health plan for federal employees has explicitly stated that it “will decline any arrangements which may manipulate the prescription drug benefit design or incorporate any programs such as copay maximizers, copay optimizers, or other similar programs as these types of benefit designs are not in the best interest of enrollees or the Government.”

If such practices are deemed unsuitable for federal employees, why are they considered acceptable for the rest of the American population? This discrepancy raises important questions about healthcare equity.

In conclusion, the prevalence of medical bankruptcy in our country is a pressing issue that requires immediate attention. The introduction of copay accumulator programs and maximizers by PBMs has led to decreased adherence to needed medications, as well as delay in important medical procedures, exacerbating this situation. An across-the-board ban on these programs would offer immediate relief to many families that no longer can afford needed care.

It is clear that more needs to be done to ensure that all patients, regardless of their financial situation or the nature of their health insurance plan, can afford the healthcare they need. This includes ensuring that patients are not penalized for using manufacturer copay cards to help cover their costs. As we move forward, it is crucial that we continue to advocate for policies that prioritize the health and well-being of all patients.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at [email protected].

The escalating costs of medications and the prevalence of medical bankruptcy in our country have drawn criticism from governments, regulators, and the media. Federal and state governments are exploring various strategies to mitigate this issue, including the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) for drug price negotiations and the establishment of state Pharmaceutical Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs). However, it’s uncertain whether these measures will effectively reduce patients’ medication expenses, given the tendency of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to favor more expensive drugs on their formularies and the implementation challenges faced by PDABs.

The question then arises: How can we promptly assist patients, especially those with multiple chronic conditions, in affording their healthcare? Many of these patients are enrolled in high-deductible plans and struggle to cover all their medical and pharmacy costs.

A significant obstacle to healthcare affordability emerged in 2018 with the introduction of Copay Accumulator Programs by PBMs. These programs prevent patients from applying manufacturer copay cards toward their deductible and maximum out-of-pocket (OOP) costs. The impact of these policies has been devastating, leading to decreased adherence to medications and delayed necessary medical procedures, such as colonoscopies. Copay accumulators do nothing to address the high cost of medical care. They merely shift the burden from insurance companies to patients.

There is a direct solution to help patients, particularly those burdened with high pharmacy bills, afford their medical care. It would be that all payments from patients, including manufacturer copay cards, count toward their deductible and maximum OOP costs. This should apply regardless of whether the insurance plan is fully funded or a self-insured employer plan. This would be an immediate step toward making healthcare more affordable for patients.

Copay Accumulator Programs

How did these detrimental policies, which have been proven to harm patients, originate? It’s interesting that health insurance policies for federal employees do not allow these programs and yet the federal government has done little to protect its citizens from these egregious policies. More on that later.

In 2018, insurance companies and PBMs conceived an idea to introduce what they called copay accumulator adjustment programs. These programs would prevent the use of manufacturer copay cards from counting toward patient deductibles or OOP maximums. They justified this by arguing that manufacturer copay cards encouraged patients to opt for higher-priced brand drugs when lower-cost generics were available.

However, data from IQVIA contradicts this claim. An analysis of copay card usage from 2013 to 2017 revealed that a mere 0.4% of these cards were used for brand-name drugs that had already lost their exclusivity. This indicates that the vast majority of copay cards were not being used to purchase more expensive brand-name drugs when cheaper, generic alternatives were available.

Another argument put forth by one of the large PBMs was that patients with high deductibles don’t have enough “skin in the game” due to their low premiums, and therefore don’t deserve to have their deductible covered by a copay card. This raises the question, “Does a patient with hemophilia or systemic lupus who can’t afford a low deductible plan not have ‘skin in the game’? Is that a fair assessment?” It’s disconcerting to see a multibillion-dollar company dictating who deserves to have their deductible covered. These policies clearly disproportionately harm patients with chronic illnesses, especially those with high deductibles. As a result, many organizations have labeled these policies as discriminatory.

Following the implementation of accumulator programs in 2018 and 2019, many patients were unaware that their copay cards weren’t contributing toward their deductibles. They were taken aback when specialty pharmacies informed them of owing substantial amounts because of unmet deductibles. Consequently, patients discontinued their medications, leading to disease progression and increased costs. The only downside for health insurers and PBMs was the negative publicity associated with patients losing medication access.

Maximizer Programs

By the end of 2019, the three major PBMs had devised a strategy to keep patients on their medication throughout the year, without counting copay cards toward the deductible, and found a way to profit more from these cards, sometimes quadrupling their value. This was the birth of the maximizer programs.

Maximizers exploit a “loophole” in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA defines Essential Healthcare Benefits (EHB); anything not listed as an EHB is deemed “non-essential.” As a result, neither personal payments nor copay cards count toward deductibles or OOP maximums. Patients were informed that neither their own money nor manufacturer copay cards would count toward their deductible/OOP max.

One of my patients was warned that without enrolling in the maximizer program through SaveOnSP (owned by Express Scripts), she would bear the full cost of the drug, and nothing would count toward her OOP max. Frightened, she enrolled and surrendered her manufacturer copay card to SaveOnSP. Maximizers pocket the maximum value of the copay card, even if it exceeds the insurance plan’s yearly cost share by threefold or more. To do this legally, PBMs increase the patient’s original cost share amount during the plan year to match the value of the manufacturer copay card.

Combating These Programs

Nineteen states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico have outlawed copay accumulators in health plans under state jurisdiction. I personally testified in Louisiana, leading to a ban in our state. CSRO’s award-winning map tool can show if your state has passed the ban on copay accumulator programs. However, many states have not passed bans on copay accumulators and self-insured employer groups, which fall under the Department of Labor and not state regulation, are still unaffected. There is also proposed federal legislation, the “Help Ensure Lower Patient Copays Act,” that would prohibit the use of copay accumulators in exchange plans. Despite having bipartisan support, it is having a hard time getting across the finish line in Congress.

In 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued a rule prohibiting accumulator programs in all plans if the product was a brand name without a generic alternative. Unfortunately, this rule was rescinded in 2021, allowing copay accumulators even if a lower-cost generic was available.

In a positive turn of events, the US District Court of the District of Columbia overturned the 2021 rule in late 2023, reinstating the 2020 ban on copay accumulators. However, HHS has yet to enforce this ban.

Double Standard

Why is it that our federal government refrains from enforcing bans on copay accumulators for the American public, yet the US Office of Personnel Management (OPM) in its 2024 health plan for federal employees has explicitly stated that it “will decline any arrangements which may manipulate the prescription drug benefit design or incorporate any programs such as copay maximizers, copay optimizers, or other similar programs as these types of benefit designs are not in the best interest of enrollees or the Government.”

If such practices are deemed unsuitable for federal employees, why are they considered acceptable for the rest of the American population? This discrepancy raises important questions about healthcare equity.

In conclusion, the prevalence of medical bankruptcy in our country is a pressing issue that requires immediate attention. The introduction of copay accumulator programs and maximizers by PBMs has led to decreased adherence to needed medications, as well as delay in important medical procedures, exacerbating this situation. An across-the-board ban on these programs would offer immediate relief to many families that no longer can afford needed care.

It is clear that more needs to be done to ensure that all patients, regardless of their financial situation or the nature of their health insurance plan, can afford the healthcare they need. This includes ensuring that patients are not penalized for using manufacturer copay cards to help cover their costs. As we move forward, it is crucial that we continue to advocate for policies that prioritize the health and well-being of all patients.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at [email protected].

The escalating costs of medications and the prevalence of medical bankruptcy in our country have drawn criticism from governments, regulators, and the media. Federal and state governments are exploring various strategies to mitigate this issue, including the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) for drug price negotiations and the establishment of state Pharmaceutical Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs). However, it’s uncertain whether these measures will effectively reduce patients’ medication expenses, given the tendency of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to favor more expensive drugs on their formularies and the implementation challenges faced by PDABs.

The question then arises: How can we promptly assist patients, especially those with multiple chronic conditions, in affording their healthcare? Many of these patients are enrolled in high-deductible plans and struggle to cover all their medical and pharmacy costs.

A significant obstacle to healthcare affordability emerged in 2018 with the introduction of Copay Accumulator Programs by PBMs. These programs prevent patients from applying manufacturer copay cards toward their deductible and maximum out-of-pocket (OOP) costs. The impact of these policies has been devastating, leading to decreased adherence to medications and delayed necessary medical procedures, such as colonoscopies. Copay accumulators do nothing to address the high cost of medical care. They merely shift the burden from insurance companies to patients.

There is a direct solution to help patients, particularly those burdened with high pharmacy bills, afford their medical care. It would be that all payments from patients, including manufacturer copay cards, count toward their deductible and maximum OOP costs. This should apply regardless of whether the insurance plan is fully funded or a self-insured employer plan. This would be an immediate step toward making healthcare more affordable for patients.

Copay Accumulator Programs

How did these detrimental policies, which have been proven to harm patients, originate? It’s interesting that health insurance policies for federal employees do not allow these programs and yet the federal government has done little to protect its citizens from these egregious policies. More on that later.

In 2018, insurance companies and PBMs conceived an idea to introduce what they called copay accumulator adjustment programs. These programs would prevent the use of manufacturer copay cards from counting toward patient deductibles or OOP maximums. They justified this by arguing that manufacturer copay cards encouraged patients to opt for higher-priced brand drugs when lower-cost generics were available.

However, data from IQVIA contradicts this claim. An analysis of copay card usage from 2013 to 2017 revealed that a mere 0.4% of these cards were used for brand-name drugs that had already lost their exclusivity. This indicates that the vast majority of copay cards were not being used to purchase more expensive brand-name drugs when cheaper, generic alternatives were available.

Another argument put forth by one of the large PBMs was that patients with high deductibles don’t have enough “skin in the game” due to their low premiums, and therefore don’t deserve to have their deductible covered by a copay card. This raises the question, “Does a patient with hemophilia or systemic lupus who can’t afford a low deductible plan not have ‘skin in the game’? Is that a fair assessment?” It’s disconcerting to see a multibillion-dollar company dictating who deserves to have their deductible covered. These policies clearly disproportionately harm patients with chronic illnesses, especially those with high deductibles. As a result, many organizations have labeled these policies as discriminatory.

Following the implementation of accumulator programs in 2018 and 2019, many patients were unaware that their copay cards weren’t contributing toward their deductibles. They were taken aback when specialty pharmacies informed them of owing substantial amounts because of unmet deductibles. Consequently, patients discontinued their medications, leading to disease progression and increased costs. The only downside for health insurers and PBMs was the negative publicity associated with patients losing medication access.

Maximizer Programs

By the end of 2019, the three major PBMs had devised a strategy to keep patients on their medication throughout the year, without counting copay cards toward the deductible, and found a way to profit more from these cards, sometimes quadrupling their value. This was the birth of the maximizer programs.

Maximizers exploit a “loophole” in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA defines Essential Healthcare Benefits (EHB); anything not listed as an EHB is deemed “non-essential.” As a result, neither personal payments nor copay cards count toward deductibles or OOP maximums. Patients were informed that neither their own money nor manufacturer copay cards would count toward their deductible/OOP max.

One of my patients was warned that without enrolling in the maximizer program through SaveOnSP (owned by Express Scripts), she would bear the full cost of the drug, and nothing would count toward her OOP max. Frightened, she enrolled and surrendered her manufacturer copay card to SaveOnSP. Maximizers pocket the maximum value of the copay card, even if it exceeds the insurance plan’s yearly cost share by threefold or more. To do this legally, PBMs increase the patient’s original cost share amount during the plan year to match the value of the manufacturer copay card.

Combating These Programs

Nineteen states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico have outlawed copay accumulators in health plans under state jurisdiction. I personally testified in Louisiana, leading to a ban in our state. CSRO’s award-winning map tool can show if your state has passed the ban on copay accumulator programs. However, many states have not passed bans on copay accumulators and self-insured employer groups, which fall under the Department of Labor and not state regulation, are still unaffected. There is also proposed federal legislation, the “Help Ensure Lower Patient Copays Act,” that would prohibit the use of copay accumulators in exchange plans. Despite having bipartisan support, it is having a hard time getting across the finish line in Congress.

In 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued a rule prohibiting accumulator programs in all plans if the product was a brand name without a generic alternative. Unfortunately, this rule was rescinded in 2021, allowing copay accumulators even if a lower-cost generic was available.

In a positive turn of events, the US District Court of the District of Columbia overturned the 2021 rule in late 2023, reinstating the 2020 ban on copay accumulators. However, HHS has yet to enforce this ban.

Double Standard

Why is it that our federal government refrains from enforcing bans on copay accumulators for the American public, yet the US Office of Personnel Management (OPM) in its 2024 health plan for federal employees has explicitly stated that it “will decline any arrangements which may manipulate the prescription drug benefit design or incorporate any programs such as copay maximizers, copay optimizers, or other similar programs as these types of benefit designs are not in the best interest of enrollees or the Government.”

If such practices are deemed unsuitable for federal employees, why are they considered acceptable for the rest of the American population? This discrepancy raises important questions about healthcare equity.

In conclusion, the prevalence of medical bankruptcy in our country is a pressing issue that requires immediate attention. The introduction of copay accumulator programs and maximizers by PBMs has led to decreased adherence to needed medications, as well as delay in important medical procedures, exacerbating this situation. An across-the-board ban on these programs would offer immediate relief to many families that no longer can afford needed care.

It is clear that more needs to be done to ensure that all patients, regardless of their financial situation or the nature of their health insurance plan, can afford the healthcare they need. This includes ensuring that patients are not penalized for using manufacturer copay cards to help cover their costs. As we move forward, it is crucial that we continue to advocate for policies that prioritize the health and well-being of all patients.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at [email protected].

Paclitaxel Drug-Drug Interactions in the Military Health System

Background

Paclitaxel was first derived from the bark of the yew tree (Taxus brevifolia). It was discovered as part of a National Cancer Institute program screen of plants and natural products with putative anticancer activity during the 1960s.1-9 Paclitaxel works by suppressing spindle microtube dynamics, which results in the blockage of the metaphase-anaphase transitions, inhibition of mitosis, and induction of apoptosis in a broad spectrum of cancer cells. Paclitaxel also displayed additional anticancer activities, including the suppression of cell proliferation and antiangiogenic effects. However, since the growth of normal body cells may also be affected, other adverse effects (AEs) will also occur.8-18

Two different chemotherapy drugs contain paclitaxel—paclitaxel and nab-paclitaxel—and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognizes them as separate entities.19-21 Taxol (paclitaxel) was approved by the FDA in 1992 for treating advanced ovarian cancer.20 It has since been approved for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer, AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma (as an orphan drug), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and cervical cancers (in combination withbevacizumab) in 1994, 1997, 1999, and 2014, respectively.21 Since 2002, a generic version of Taxol, known as paclitaxel injectable, has been FDA-approved from different manufacturers. According to the National Cancer Institute, a combination of carboplatin and Taxol is approved to treat carcinoma of unknown primary, cervical, endometrial, NSCLC, ovarian, and thymoma cancers.19 Abraxane (nab-paclitaxel) was FDA-approved to treat metastatic breast cancer in 2005. It was later approved for first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC and late-stage pancreatic cancer in 2012 and 2013, respectively. In 2018 and 2020, both Taxol and Abraxane were approved for first-line treatment of metastatic squamous cell NSCLC in combination with carboplatin and pembrolizumab and metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in combination with pembrolizumab, respectively.22-26 In 2019, Abraxane was approved with atezolizumab to treat metastatic triple-negative breast cancer, but this approval was withdrawn in 2021. In 2022, a generic version of Abraxane, known as paclitaxel protein-bound, was released in the United States. Furthermore, paclitaxel-containing formulations also are being studied in the treatment of other types of cancer.19-32

One of the main limitations of paclitaxel is its low solubility in water, which complicates its drug supply. To distribute this hydrophobic anticancer drug efficiently, paclitaxel is formulated and administered to patients via polyethoxylated castor oil or albumin-bound (nab-paclitaxel). However, polyethoxylated castor oil induces complement activation and is the cause of common hypersensitivity reactions related to paclitaxel use.2,17,33-38 Therefore, many alternatives to polyethoxylated castor oil have been researched.

Since 2000, new paclitaxel formulations have emerged using nanomedicine techniques. The difference between these formulations is the drug vehicle. Different paclitaxel-based nanotechnological vehicles have been developed and approved, such as albumin-based nanoparticles, polymeric lipidic nanoparticles, polymeric micelles, and liposomes, with many others in clinical trial phases.3,37 Albumin-based nanoparticles have a high response rate (33%), whereas the response rate for polyethoxylated castor oil is 25% in patients with metastatic breast cancer.33,39-52 The use of paclitaxel dimer nanoparticles also has been proposed as a method for increasing drug solubility.33,53

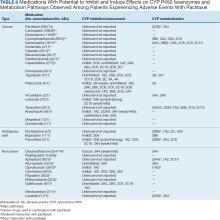

Paclitaxel is metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes 2C8 and 3A4. When administering paclitaxel with known inhibitors, inducers, or substrates of CYP2C8 or CYP3A4, caution is required.19-22 Regulations for CYP research were not issued until 2008, so potential interactions between paclitaxel and other drugs have not been extensively evaluated in clinical trials. A study of 12 kinase inhibitors showed strong inhibition of CYP2C8 and/or CYP3A4 pathways by these inhibitors, which could alter the ratio of paclitaxel metabolites in vivo, leading to clinically relevant changes.54 Differential metabolism has been linked to paclitaxel-induced neurotoxicity in patients with cancer.55 Nonetheless, variants in the CYP2C8, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and ABCB1 genes do not account for significant interindividual variability in paclitaxel pharmacokinetics.56 In liver microsomes, losartan inhibited paclitaxel metabolism when used at concentrations > 50 µmol/L.57 Many drug-drug interaction (DDI) studies of CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 have shown similar results for paclitaxel.58-64

The goals of this study are to investigate prescribed drugs used with paclitaxel and determine patient outcomes through several Military Health System (MHS) databases. The investigation focused on (1) the functions of paclitaxel; (2) identifying AEs that patients experienced; (3) evaluating differences when paclitaxel is used alone vs concomitantly and between the completed vs discontinued treatment groups; (4) identifying all drugs used during paclitaxel treatment; and (5) evaluating DDIs with antidepressants (that have an FDA boxed warning and are known to have DDIs confirmed in previous publications) and other drugs.65-67

The Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, institutionalreview board approved the study protocol and ensured compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act as an exempt protocol. The Joint Pathology Center (JPC) of the US Department of Defense (DoD) Cancer Registry Program and MHS data experts from the Comprehensive Ambulatory/Professional Encounter Record (CAPER) and the Pharmacy Data Transaction Service (PDTS) provided data for the analysis.

METHODS

The DoD Cancer Registry Program was established in 1986 and currently contains data from 1998 to 2024. CAPER and PDTS are part of the MHS Data Repository/Management Analysis and Reporting Tool database. Each observation in the CAPER record represents an ambulatory encounter at a military treatment facility (MTF). CAPER includes data from 2003 to 2024.

Each observation in the PDTS record represents a prescription filled for an MHS beneficiary at an MTF through the TRICARE mail-order program or a US retail pharmacy. Missing from this record are prescriptions filled at international civilian pharmacies and inpatient pharmacy prescriptions. The MHS Data Repository PDTS record is available from 2002 to 2024. The legacy Composite Health Care System is being replaced by GENESIS at MTFs.

Data Extraction Design

The study design involved a cross-sectional analysis. We requested data extraction for paclitaxel from 1998 to 2022. Data from the DoD Cancer Registry Program were used to identify patients who received cancer treatment. Once patients were identified, the CAPER database was searched for diagnoses to identify other health conditions, whereas the PDTS database was used to populate a list of prescription medications filled during chemotherapy treatment.

Data collected from the JPC included cancer treatment, cancer information, demographics, and physicians’ comments on AEs. Collected data from the MHS include diagnosis and filled prescription history from initiation to completion of the therapy period (or 2 years after the diagnosis date). For the analysis of the DoD Cancer Registry Program and CAPER databases, we used all collected data without excluding any. When analyzing PDTS data, we excluded patients with PDTS data but without a record of paclitaxel being filled, or medications filled outside the chemotherapy period (by evaluating the dispensed date and day of supply).

Data Extraction Analysis

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Coding and Staging Manual 2016 and the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition, 1st revision, were used to decode disease and cancer types.68,69 Data sorting and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel. The percentage for the total was calculated by using the number of patients or data available within the paclitaxel groups divided by the total number of patients or data variables. The subgroup percentage was calculated by using the number of patients or data available within the subgroup divided by the total number of patients in that subgroup.

In alone vs concomitant and completed vs discontinued treatment groups, a 2-tailed, 2-sample z test was used to statistical significance (P < .05) using a statistics website.70 Concomitant was defined as paclitaxel taken with other antineoplastic agent(s) before, after, or at the same time as cancer therapy. For the retrospective data analysis, physicians’ notes with a period, comma, forward slash, semicolon, or space between medication names were interpreted as concurrent, whereas plus (+), minus/plus (-/+), or “and” between drug names that were dispensed on the same day were interpreted as combined with known common combinations: 2 drugs (DM886 paclitaxel and carboplatin and DM881-TC-1 paclitaxel and cisplatin) or 3 drugs (DM887-ACT doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and paclitaxel). Completed treatment was defined as paclitaxel as the last medication the patient took without recorded AEs; switching or experiencing AEs was defined as discontinued treatment.

RESULTS

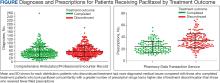

The JPC provided 702 entries for 687 patients with a mean age of 56 years (range, 2 months to 88 years) who were treated with paclitaxel from March 1996 to October 2021. Fifteen patients had duplicate entries because they had multiple cancer sites or occurrences. There were 623 patients (89%) who received paclitaxel for FDA-approved indications. The most common types of cancer identified were 344 patients with breast cancer (49%), 91 patients with lung cancer (13%), 79 patients with ovarian cancer (11%), and 75 patients with endometrial cancer (11%) (Table 1). Seventy-nine patients (11%) received paclitaxel for cancers that were not for FDA-approved indications, including 19 for cancers of the fallopian tube (3%) and 17 for esophageal cancer (2%) (Table 2).

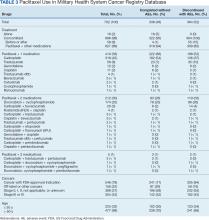

There were 477 patients (68%) aged > 50 years. A total of 304 patients (43%) had a stage III or IV cancer diagnosis and 398 (57%) had stage II or lower (combination of data for stages 0, I, and II; not applicable; and unknown) cancer diagnosis. For systemic treatment, 16 patients (2%) were treated with paclitaxel alone and 686 patients (98%) received paclitaxel concomitantly with additional chemotherapy: 59 patients (9%) in the before or after group, 410 patients (58%) had a 2-drug combination, 212 patients (30%) had a 3-drug combination, and 5 patients (1%) had a 4-drug combination. In addition, for doublet therapies, paclitaxel combined with carboplatin, trastuzumab, gemcitabine, or cisplatin had more patients (318, 58, 12, and 11, respectively) than other combinations (≤ 4 patients). For triplet therapies, paclitaxel combined withdoxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide or carboplatin plus bevacizumab had more patients (174 and 20, respectively) than other combinations, including quadruplet therapies (≤ 4 patients) (Table 3).

Patients were more likely to discontinue paclitaxel if they received concomitant treatment. None of the 16 patients receiving paclitaxel monotherapy experienced AEs, whereas 364 of 686 patients (53%) treated concomitantly discontinued (P < .001). Comparisons of 1 drug vs combination (2 to 4 drugs) and use for treating cancers that were FDA-approved indications vs off-label use were significant (P < .001), whereas comparisons of stage II or lower vs stage III and IV cancer and of those aged ≤ 50 years vs aged > 50 years were not significant (P = .50 andP = .30, respectively) (Table 4).

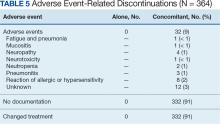

Among the 364 patients who had concomitant treatment and had discontinued their treatment, 332 (91%) switched treatments with no AEs documented and 32 (9%) experienced fatigue with pneumonia, mucositis, neuropathy, neurotoxicity, neutropenia, pneumonitis, allergic or hypersensitivity reaction, or an unknown AE. Patients who discontinued treatment because of unknown AEs had a physician’s note that detailed progressive disease, a significant decline in performance status, and another unknown adverse effect due to a previous sinus tract infection and infectious colitis (Table 5).

Management Analysis and Reporting Tool Database