User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

ASCO to award $50,000 young investigator grant to study MCL

Early-career researchers who are interested in studying

The young investigator grant is for a 1-year period and the award is used to fund a project focused on clinical or translational research on the clinical biology, natural history, prevention, screening, diagnosis, therapy, or epidemiology of MCL.

The purpose of this annual award, according to ASCO, is to fund physicians during the transition from a fellowship program to a faculty appointment.

Eligible applicants must be physicians currently in the last 2 years of final subspecialty training and within 10 years of having obtained his or her medical degree. Additionally, applicants must be planning a research career in clinical oncology, with a focus on MCL.

The grant selection committee’s primary criteria include the significance and originality of the proposed study and hypothesis, the feasibility of the experiment and methodology, whether it has an appropriate and detailed statistical analysis plan, and if the research is patient oriented.

The application deadline is Jan. 7, 2020, and the award term is July 1, 2020–June 30, 2021.

Application instructions are available on the ASCO website.

Early-career researchers who are interested in studying

The young investigator grant is for a 1-year period and the award is used to fund a project focused on clinical or translational research on the clinical biology, natural history, prevention, screening, diagnosis, therapy, or epidemiology of MCL.

The purpose of this annual award, according to ASCO, is to fund physicians during the transition from a fellowship program to a faculty appointment.

Eligible applicants must be physicians currently in the last 2 years of final subspecialty training and within 10 years of having obtained his or her medical degree. Additionally, applicants must be planning a research career in clinical oncology, with a focus on MCL.

The grant selection committee’s primary criteria include the significance and originality of the proposed study and hypothesis, the feasibility of the experiment and methodology, whether it has an appropriate and detailed statistical analysis plan, and if the research is patient oriented.

The application deadline is Jan. 7, 2020, and the award term is July 1, 2020–June 30, 2021.

Application instructions are available on the ASCO website.

Early-career researchers who are interested in studying

The young investigator grant is for a 1-year period and the award is used to fund a project focused on clinical or translational research on the clinical biology, natural history, prevention, screening, diagnosis, therapy, or epidemiology of MCL.

The purpose of this annual award, according to ASCO, is to fund physicians during the transition from a fellowship program to a faculty appointment.

Eligible applicants must be physicians currently in the last 2 years of final subspecialty training and within 10 years of having obtained his or her medical degree. Additionally, applicants must be planning a research career in clinical oncology, with a focus on MCL.

The grant selection committee’s primary criteria include the significance and originality of the proposed study and hypothesis, the feasibility of the experiment and methodology, whether it has an appropriate and detailed statistical analysis plan, and if the research is patient oriented.

The application deadline is Jan. 7, 2020, and the award term is July 1, 2020–June 30, 2021.

Application instructions are available on the ASCO website.

Trastuzumab benefit lasts long-term in HER2+ breast cancer

Among patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive (HER2+) breast cancer, adding trastuzumab to adjuvant chemotherapy reduces risk of recurrence for at least 10 years, according to investigators.

The benefit of trastuzumab was greater among patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) disease than those with HR– disease until the 5-year timepoint, after which HR status had no significant impact on recurrence rates, reported lead author Saranya Chumsri, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues. This finding echoes a pattern similar to that of HER2– breast cancer, in which patients with HR+ disease have relatively consistent risk of recurrence over time, whereas patients with HR– disease have an early risk of recurrence that decreases after 5 years.

“To the best of our knowledge, this analysis is the first to address the risk of late relapses in subsets of HER2+ breast cancer patients who were treated with adjuvant trastuzumab,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

They drew data from 3,177 patients with HER2+ breast cancer who were involved in two phase 3 studies: the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 and National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-31 trials. Patients involved in the analysis received either standard adjuvant chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin followed by weekly paclitaxel or the same chemotherapy regimen plus concurrent trastuzumab. The primary outcome was recurrence-free survival, which was defined as time from randomization until local, regional, or distant recurrence of breast cancer or breast cancer–related death. Kaplan-Meier estimates were performed to determine recurrence-free survival, while Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to determine factors that predicted relapse.

Including a median follow-up of 8 years across all patients, the analysis showed that those with HR+ breast cancer had a significantly higher estimated rate of recurrence-free survival than that of those with HR– disease after 5 years (81.49% vs. 74.65%) and 10 years (73.84% vs. 69.22%). Overall, a comparable level of benefit was derived from adding trastuzumab regardless of HR status (interaction P = .87). However, during the first 5 years, HR positivity predicted greater benefit from adding trastuzumab, as patients with HR+ disease had a 40% lower risk of relapse than that of those with HR– disease (hazard ratio, 0.60; P less than .001). Between years 5 and 10, the statistical significance of HR status faded (P = .12), suggesting that HR status is not a predictor of long-term recurrence.

“Given concerning adverse effects and potentially smaller benefit of extended adjuvant endocrine therapy, particularly in patients with N0 or N1 disease, our findings highlight the need to develop better risk prediction models and biomarkers to identify which patients have sufficient risk for late relapse to warrant the use of extended endocrine therapy in HER2+ breast cancer,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, Bankhead-Coley Research Program, the DONNA Foundation, and Genentech. Dr. Chumsri disclosed a financial relationship with Merck. Coauthors disclosed ties with Merck, Novartis, Genentech, and NanoString Technologies.

SOURCE: Chumsri et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Oct 17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00443.

Among patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive (HER2+) breast cancer, adding trastuzumab to adjuvant chemotherapy reduces risk of recurrence for at least 10 years, according to investigators.

The benefit of trastuzumab was greater among patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) disease than those with HR– disease until the 5-year timepoint, after which HR status had no significant impact on recurrence rates, reported lead author Saranya Chumsri, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues. This finding echoes a pattern similar to that of HER2– breast cancer, in which patients with HR+ disease have relatively consistent risk of recurrence over time, whereas patients with HR– disease have an early risk of recurrence that decreases after 5 years.

“To the best of our knowledge, this analysis is the first to address the risk of late relapses in subsets of HER2+ breast cancer patients who were treated with adjuvant trastuzumab,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

They drew data from 3,177 patients with HER2+ breast cancer who were involved in two phase 3 studies: the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 and National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-31 trials. Patients involved in the analysis received either standard adjuvant chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin followed by weekly paclitaxel or the same chemotherapy regimen plus concurrent trastuzumab. The primary outcome was recurrence-free survival, which was defined as time from randomization until local, regional, or distant recurrence of breast cancer or breast cancer–related death. Kaplan-Meier estimates were performed to determine recurrence-free survival, while Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to determine factors that predicted relapse.

Including a median follow-up of 8 years across all patients, the analysis showed that those with HR+ breast cancer had a significantly higher estimated rate of recurrence-free survival than that of those with HR– disease after 5 years (81.49% vs. 74.65%) and 10 years (73.84% vs. 69.22%). Overall, a comparable level of benefit was derived from adding trastuzumab regardless of HR status (interaction P = .87). However, during the first 5 years, HR positivity predicted greater benefit from adding trastuzumab, as patients with HR+ disease had a 40% lower risk of relapse than that of those with HR– disease (hazard ratio, 0.60; P less than .001). Between years 5 and 10, the statistical significance of HR status faded (P = .12), suggesting that HR status is not a predictor of long-term recurrence.

“Given concerning adverse effects and potentially smaller benefit of extended adjuvant endocrine therapy, particularly in patients with N0 or N1 disease, our findings highlight the need to develop better risk prediction models and biomarkers to identify which patients have sufficient risk for late relapse to warrant the use of extended endocrine therapy in HER2+ breast cancer,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, Bankhead-Coley Research Program, the DONNA Foundation, and Genentech. Dr. Chumsri disclosed a financial relationship with Merck. Coauthors disclosed ties with Merck, Novartis, Genentech, and NanoString Technologies.

SOURCE: Chumsri et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Oct 17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00443.

Among patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive (HER2+) breast cancer, adding trastuzumab to adjuvant chemotherapy reduces risk of recurrence for at least 10 years, according to investigators.

The benefit of trastuzumab was greater among patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) disease than those with HR– disease until the 5-year timepoint, after which HR status had no significant impact on recurrence rates, reported lead author Saranya Chumsri, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues. This finding echoes a pattern similar to that of HER2– breast cancer, in which patients with HR+ disease have relatively consistent risk of recurrence over time, whereas patients with HR– disease have an early risk of recurrence that decreases after 5 years.

“To the best of our knowledge, this analysis is the first to address the risk of late relapses in subsets of HER2+ breast cancer patients who were treated with adjuvant trastuzumab,” the investigators wrote. Their report is in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

They drew data from 3,177 patients with HER2+ breast cancer who were involved in two phase 3 studies: the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 and National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-31 trials. Patients involved in the analysis received either standard adjuvant chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin followed by weekly paclitaxel or the same chemotherapy regimen plus concurrent trastuzumab. The primary outcome was recurrence-free survival, which was defined as time from randomization until local, regional, or distant recurrence of breast cancer or breast cancer–related death. Kaplan-Meier estimates were performed to determine recurrence-free survival, while Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to determine factors that predicted relapse.

Including a median follow-up of 8 years across all patients, the analysis showed that those with HR+ breast cancer had a significantly higher estimated rate of recurrence-free survival than that of those with HR– disease after 5 years (81.49% vs. 74.65%) and 10 years (73.84% vs. 69.22%). Overall, a comparable level of benefit was derived from adding trastuzumab regardless of HR status (interaction P = .87). However, during the first 5 years, HR positivity predicted greater benefit from adding trastuzumab, as patients with HR+ disease had a 40% lower risk of relapse than that of those with HR– disease (hazard ratio, 0.60; P less than .001). Between years 5 and 10, the statistical significance of HR status faded (P = .12), suggesting that HR status is not a predictor of long-term recurrence.

“Given concerning adverse effects and potentially smaller benefit of extended adjuvant endocrine therapy, particularly in patients with N0 or N1 disease, our findings highlight the need to develop better risk prediction models and biomarkers to identify which patients have sufficient risk for late relapse to warrant the use of extended endocrine therapy in HER2+ breast cancer,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, Bankhead-Coley Research Program, the DONNA Foundation, and Genentech. Dr. Chumsri disclosed a financial relationship with Merck. Coauthors disclosed ties with Merck, Novartis, Genentech, and NanoString Technologies.

SOURCE: Chumsri et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Oct 17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00443.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

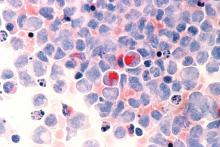

Adverse cytogenetics trump molecular risk in NPM1-mutated AML

A pooled analysis suggests adverse cytogenetics are a key factor negatively impacting outcomes in patients with NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

In patients with adverse chromosomal abnormalities, NPM1 mutational status was found not to confer a favorable outcome. The findings suggest cytogenetic risk outweighs molecular risk in patients with NPM1 mutations and the FLT3-ITDneg/low genotype.

“Patients carrying adverse-risk cytogenetics shared a virtually identical unfavorable outcome, regardless of whether the otherwise beneficial NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low status was present. The type of the adverse chromosomal abnormality did not seem to influence this effect, although low numbers might obscure detection of heterogeneity among individual aberrations,” Linus Angenendt, MD, of University Hospital Munster (Germany) and colleagues, wrote in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed 2,426 patients with NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low AML. Of these, 17.6% had an abnormal karyotype, and 3.4% had adverse-risk chromosomal aberrations.

Prior to analysis, individual patient data were pooled from nine international AML study group registries or treatment centers.

After analysis, the researchers found that adverse cytogenetics were associated with inferior complete remission rates (66.3%), compared with in patients with normal karyotype or intermediate-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (87.7% and 86.0%, respectively; P less than .001). The complete remission rates for the NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low AML adverse cytogenetics group was similar to patients with NPM1wt/FLT3-ITDneg/low and adverse cytogenetic abnormalities (66.3% vs. 57.5%).

Five-year event-free survival rates and overall survival rates were also lower in patients with NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low AML and adverse cytogenetics, compared with patients with normal karyotype or intermediate-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (P less than .001).

“Even though the combination of an NPM1 mutation with these abnormalities is rare, the prognostic effect of adverse cytogenetics in NPM1mut AML has important implications for postremission treatment decisions, in particular, the current recommendation that patients who are NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low not receive allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), given their presumed low risk of relapse might be altered if the adverse karyotype increased the risk,” they wrote.

The type of chromosomal aberration did not appear to impact this effect, but the small sample size may have hindered the ability to detect a difference between different abnormalities, the researchers noted.

One key limitation of the study was the retrospective design. As a result, in patients with an abnormal karyotype, some genetic analyses could have been underutilized.

“These results demand additional validation within prospective trials,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the University of Munster Medical School, the German Research Foundation, the French government, the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic, and others. The authors reported financial affiliations with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Angenendt L et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Oct 10;37(29):2632-42.

A pooled analysis suggests adverse cytogenetics are a key factor negatively impacting outcomes in patients with NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

In patients with adverse chromosomal abnormalities, NPM1 mutational status was found not to confer a favorable outcome. The findings suggest cytogenetic risk outweighs molecular risk in patients with NPM1 mutations and the FLT3-ITDneg/low genotype.

“Patients carrying adverse-risk cytogenetics shared a virtually identical unfavorable outcome, regardless of whether the otherwise beneficial NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low status was present. The type of the adverse chromosomal abnormality did not seem to influence this effect, although low numbers might obscure detection of heterogeneity among individual aberrations,” Linus Angenendt, MD, of University Hospital Munster (Germany) and colleagues, wrote in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed 2,426 patients with NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low AML. Of these, 17.6% had an abnormal karyotype, and 3.4% had adverse-risk chromosomal aberrations.

Prior to analysis, individual patient data were pooled from nine international AML study group registries or treatment centers.

After analysis, the researchers found that adverse cytogenetics were associated with inferior complete remission rates (66.3%), compared with in patients with normal karyotype or intermediate-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (87.7% and 86.0%, respectively; P less than .001). The complete remission rates for the NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low AML adverse cytogenetics group was similar to patients with NPM1wt/FLT3-ITDneg/low and adverse cytogenetic abnormalities (66.3% vs. 57.5%).

Five-year event-free survival rates and overall survival rates were also lower in patients with NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low AML and adverse cytogenetics, compared with patients with normal karyotype or intermediate-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (P less than .001).

“Even though the combination of an NPM1 mutation with these abnormalities is rare, the prognostic effect of adverse cytogenetics in NPM1mut AML has important implications for postremission treatment decisions, in particular, the current recommendation that patients who are NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low not receive allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), given their presumed low risk of relapse might be altered if the adverse karyotype increased the risk,” they wrote.

The type of chromosomal aberration did not appear to impact this effect, but the small sample size may have hindered the ability to detect a difference between different abnormalities, the researchers noted.

One key limitation of the study was the retrospective design. As a result, in patients with an abnormal karyotype, some genetic analyses could have been underutilized.

“These results demand additional validation within prospective trials,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the University of Munster Medical School, the German Research Foundation, the French government, the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic, and others. The authors reported financial affiliations with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Angenendt L et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Oct 10;37(29):2632-42.

A pooled analysis suggests adverse cytogenetics are a key factor negatively impacting outcomes in patients with NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

In patients with adverse chromosomal abnormalities, NPM1 mutational status was found not to confer a favorable outcome. The findings suggest cytogenetic risk outweighs molecular risk in patients with NPM1 mutations and the FLT3-ITDneg/low genotype.

“Patients carrying adverse-risk cytogenetics shared a virtually identical unfavorable outcome, regardless of whether the otherwise beneficial NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low status was present. The type of the adverse chromosomal abnormality did not seem to influence this effect, although low numbers might obscure detection of heterogeneity among individual aberrations,” Linus Angenendt, MD, of University Hospital Munster (Germany) and colleagues, wrote in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed 2,426 patients with NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low AML. Of these, 17.6% had an abnormal karyotype, and 3.4% had adverse-risk chromosomal aberrations.

Prior to analysis, individual patient data were pooled from nine international AML study group registries or treatment centers.

After analysis, the researchers found that adverse cytogenetics were associated with inferior complete remission rates (66.3%), compared with in patients with normal karyotype or intermediate-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (87.7% and 86.0%, respectively; P less than .001). The complete remission rates for the NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low AML adverse cytogenetics group was similar to patients with NPM1wt/FLT3-ITDneg/low and adverse cytogenetic abnormalities (66.3% vs. 57.5%).

Five-year event-free survival rates and overall survival rates were also lower in patients with NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low AML and adverse cytogenetics, compared with patients with normal karyotype or intermediate-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (P less than .001).

“Even though the combination of an NPM1 mutation with these abnormalities is rare, the prognostic effect of adverse cytogenetics in NPM1mut AML has important implications for postremission treatment decisions, in particular, the current recommendation that patients who are NPM1mut/FLT3-ITDneg/low not receive allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), given their presumed low risk of relapse might be altered if the adverse karyotype increased the risk,” they wrote.

The type of chromosomal aberration did not appear to impact this effect, but the small sample size may have hindered the ability to detect a difference between different abnormalities, the researchers noted.

One key limitation of the study was the retrospective design. As a result, in patients with an abnormal karyotype, some genetic analyses could have been underutilized.

“These results demand additional validation within prospective trials,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the University of Munster Medical School, the German Research Foundation, the French government, the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic, and others. The authors reported financial affiliations with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Angenendt L et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Oct 10;37(29):2632-42.

REPORTING FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Nivolumab boosts overall survival in HCC

BARCELONA – Checkpoint inhibition with nivolumab led to a clinically meaningful, but not statistically significant, improvement in overall survival, compared with sorafenib for the first-line treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the phase 3 CheckMate 459 study.

Median overall survival (OS), the primary study endpoint, was 16.4 months in 371 patients randomized to receive the programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor nivolumab, and 14.7 months in 372 patients who received the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib – the current standard for advanced HCC therapy (hazard ratio, 0.85; P = .0752), Thomas Yau, MD, reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

The median OS seen with nivolumab is the longest ever reported in a first-line phase 3 HCC trial, but the difference between the arms did not meet the predefined threshold for statistical significance (HR, 0.84 and P = .419). However, clinical benefit was observed across predefined subgroups of patients, including those with hepatitis infection and those with vascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread, said Dr. Yau of the University of Hong Kong.

The overall response rates (ORR) were 15% and 7% in the nivolumab and sorafenib arms, with 14 and 5 patients in each group experiencing a complete response (CR), respectively, he said.

At 12 and 24 months, the OS rates in the groups were 59.7% vs. 55.1%, and 36.5% vs. 33.1%, respectively. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was similar in the groups, at 3.7 and 3.8 months, respectively, and analysis by baseline tumor programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression showed that ORR was 28% vs. 9% with PD-L1 expression of 1% or greater in the groups, respectively, and 12% vs. 7% among those with PD-L1 expression less than 1%.

Additionally, nivolumab had a more tolerable safety profile; grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events were reported in 22% and 49% of patients in the groups, respectively, and led to discontinuation in 4% and 8%, respectively. No new safety signals were observed, Dr. Yau said.

Participants in the multicenter study were systemic therapy–naive adults with advanced disease. They were randomized 1:1 to receive intravenous nivolumab at a dose of 240 mg every 2 weeks or oral sorafenib at a dose of 400 mg twice daily, and were followed for at least 22.8 months.

“These results are important in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma, as there have been no significant advances over sorafenib in the first-line setting in more than a decade,” Dr. Yau said in an ESMO press release. “HCC is often diagnosed in the advanced stage, where effective treatment options are limited. The encouraging efficacy and favorable safety profile seen with nivolumab demonstrates the potential benefit of immunotherapy as a first-line treatment for patients with this aggressive cancer.”

He further noted that the OS benefit seen in this study is “particularly impactful considering the high frequency of subsequent use of systemic therapy, including immunotherapy, in the sorafenib arm,” and that the OS impact is bolstered by patient-reported outcomes suggesting improved quality of life in the nivolumab arm.

Nevertheless, the fact that CheckMate 459 did not meet its primary OS endpoint means the findings are unlikely to change the current standard of care, according to Angela Lamarca, MD, PhD, consultant medical oncologist and honorary senior lecturer at the Christie NHS Foundation Trust, University of Manchester (England).

She added, however, that the findings do underscore a potential role for immunotherapy in the first-line treatment of advanced HCC and noted that the clinically meaningful improvement in response rates with nivolumab, along with the checkpoint inhibitor’s favorable safety profile in this study, raise the possibility of its selection in this setting.

“In a hypothetical scenario in which both options ... were available and reimbursed, and if quality of life was shown to be better with nivolumab ... clinicians and patients may favor the option with a more tolerable safety profile,” she said in the press release.

She added, however, that at this point conclusions should be made cautiously and the high cost of immunotherapy should be considered.

Dr. Lamarca also highlighted the finding that patients with high PD-L1 expression had an increased response rate only in the nivolumab arm. This suggests a potential role for PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in advanced HCC, but more research is needed to better understand how to select patients for immunotherapy, she said, adding that the lack of a reliable biomarker may have contributed to the study’s failure to show improved OS with nivolumab.

“In addition, the study design with a ‘high’ predefined threshold of statistical significance is generating confusion in the community, with potentially beneficial therapies generating statistically negative studies,” she noted.

CheckMate 459 was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Yau is an advisor and/or consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, and reported honoraria from the company to his institution. Dr. Lamarca reported honoraria, consultation fees, travel funding, and/or education funding from Eisai, Nutricia, Ipsen, Pfizer, Bayer, AAA, Sirtex, Delcath, Novartis, and Mylan, as well as participation in company-sponsored speaker bureaus for Pfizer, Ipsen, Merck, and Incyte.

SOURCE: Yau T et al. ESMO 2019, Abstract LBA38-PR

BARCELONA – Checkpoint inhibition with nivolumab led to a clinically meaningful, but not statistically significant, improvement in overall survival, compared with sorafenib for the first-line treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the phase 3 CheckMate 459 study.

Median overall survival (OS), the primary study endpoint, was 16.4 months in 371 patients randomized to receive the programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor nivolumab, and 14.7 months in 372 patients who received the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib – the current standard for advanced HCC therapy (hazard ratio, 0.85; P = .0752), Thomas Yau, MD, reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

The median OS seen with nivolumab is the longest ever reported in a first-line phase 3 HCC trial, but the difference between the arms did not meet the predefined threshold for statistical significance (HR, 0.84 and P = .419). However, clinical benefit was observed across predefined subgroups of patients, including those with hepatitis infection and those with vascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread, said Dr. Yau of the University of Hong Kong.

The overall response rates (ORR) were 15% and 7% in the nivolumab and sorafenib arms, with 14 and 5 patients in each group experiencing a complete response (CR), respectively, he said.

At 12 and 24 months, the OS rates in the groups were 59.7% vs. 55.1%, and 36.5% vs. 33.1%, respectively. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was similar in the groups, at 3.7 and 3.8 months, respectively, and analysis by baseline tumor programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression showed that ORR was 28% vs. 9% with PD-L1 expression of 1% or greater in the groups, respectively, and 12% vs. 7% among those with PD-L1 expression less than 1%.

Additionally, nivolumab had a more tolerable safety profile; grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events were reported in 22% and 49% of patients in the groups, respectively, and led to discontinuation in 4% and 8%, respectively. No new safety signals were observed, Dr. Yau said.

Participants in the multicenter study were systemic therapy–naive adults with advanced disease. They were randomized 1:1 to receive intravenous nivolumab at a dose of 240 mg every 2 weeks or oral sorafenib at a dose of 400 mg twice daily, and were followed for at least 22.8 months.

“These results are important in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma, as there have been no significant advances over sorafenib in the first-line setting in more than a decade,” Dr. Yau said in an ESMO press release. “HCC is often diagnosed in the advanced stage, where effective treatment options are limited. The encouraging efficacy and favorable safety profile seen with nivolumab demonstrates the potential benefit of immunotherapy as a first-line treatment for patients with this aggressive cancer.”

He further noted that the OS benefit seen in this study is “particularly impactful considering the high frequency of subsequent use of systemic therapy, including immunotherapy, in the sorafenib arm,” and that the OS impact is bolstered by patient-reported outcomes suggesting improved quality of life in the nivolumab arm.

Nevertheless, the fact that CheckMate 459 did not meet its primary OS endpoint means the findings are unlikely to change the current standard of care, according to Angela Lamarca, MD, PhD, consultant medical oncologist and honorary senior lecturer at the Christie NHS Foundation Trust, University of Manchester (England).

She added, however, that the findings do underscore a potential role for immunotherapy in the first-line treatment of advanced HCC and noted that the clinically meaningful improvement in response rates with nivolumab, along with the checkpoint inhibitor’s favorable safety profile in this study, raise the possibility of its selection in this setting.

“In a hypothetical scenario in which both options ... were available and reimbursed, and if quality of life was shown to be better with nivolumab ... clinicians and patients may favor the option with a more tolerable safety profile,” she said in the press release.

She added, however, that at this point conclusions should be made cautiously and the high cost of immunotherapy should be considered.

Dr. Lamarca also highlighted the finding that patients with high PD-L1 expression had an increased response rate only in the nivolumab arm. This suggests a potential role for PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in advanced HCC, but more research is needed to better understand how to select patients for immunotherapy, she said, adding that the lack of a reliable biomarker may have contributed to the study’s failure to show improved OS with nivolumab.

“In addition, the study design with a ‘high’ predefined threshold of statistical significance is generating confusion in the community, with potentially beneficial therapies generating statistically negative studies,” she noted.

CheckMate 459 was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Yau is an advisor and/or consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, and reported honoraria from the company to his institution. Dr. Lamarca reported honoraria, consultation fees, travel funding, and/or education funding from Eisai, Nutricia, Ipsen, Pfizer, Bayer, AAA, Sirtex, Delcath, Novartis, and Mylan, as well as participation in company-sponsored speaker bureaus for Pfizer, Ipsen, Merck, and Incyte.

SOURCE: Yau T et al. ESMO 2019, Abstract LBA38-PR

BARCELONA – Checkpoint inhibition with nivolumab led to a clinically meaningful, but not statistically significant, improvement in overall survival, compared with sorafenib for the first-line treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the phase 3 CheckMate 459 study.

Median overall survival (OS), the primary study endpoint, was 16.4 months in 371 patients randomized to receive the programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor nivolumab, and 14.7 months in 372 patients who received the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib – the current standard for advanced HCC therapy (hazard ratio, 0.85; P = .0752), Thomas Yau, MD, reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

The median OS seen with nivolumab is the longest ever reported in a first-line phase 3 HCC trial, but the difference between the arms did not meet the predefined threshold for statistical significance (HR, 0.84 and P = .419). However, clinical benefit was observed across predefined subgroups of patients, including those with hepatitis infection and those with vascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread, said Dr. Yau of the University of Hong Kong.

The overall response rates (ORR) were 15% and 7% in the nivolumab and sorafenib arms, with 14 and 5 patients in each group experiencing a complete response (CR), respectively, he said.

At 12 and 24 months, the OS rates in the groups were 59.7% vs. 55.1%, and 36.5% vs. 33.1%, respectively. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was similar in the groups, at 3.7 and 3.8 months, respectively, and analysis by baseline tumor programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression showed that ORR was 28% vs. 9% with PD-L1 expression of 1% or greater in the groups, respectively, and 12% vs. 7% among those with PD-L1 expression less than 1%.

Additionally, nivolumab had a more tolerable safety profile; grade 3/4 treatment-related adverse events were reported in 22% and 49% of patients in the groups, respectively, and led to discontinuation in 4% and 8%, respectively. No new safety signals were observed, Dr. Yau said.

Participants in the multicenter study were systemic therapy–naive adults with advanced disease. They were randomized 1:1 to receive intravenous nivolumab at a dose of 240 mg every 2 weeks or oral sorafenib at a dose of 400 mg twice daily, and were followed for at least 22.8 months.

“These results are important in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma, as there have been no significant advances over sorafenib in the first-line setting in more than a decade,” Dr. Yau said in an ESMO press release. “HCC is often diagnosed in the advanced stage, where effective treatment options are limited. The encouraging efficacy and favorable safety profile seen with nivolumab demonstrates the potential benefit of immunotherapy as a first-line treatment for patients with this aggressive cancer.”

He further noted that the OS benefit seen in this study is “particularly impactful considering the high frequency of subsequent use of systemic therapy, including immunotherapy, in the sorafenib arm,” and that the OS impact is bolstered by patient-reported outcomes suggesting improved quality of life in the nivolumab arm.

Nevertheless, the fact that CheckMate 459 did not meet its primary OS endpoint means the findings are unlikely to change the current standard of care, according to Angela Lamarca, MD, PhD, consultant medical oncologist and honorary senior lecturer at the Christie NHS Foundation Trust, University of Manchester (England).

She added, however, that the findings do underscore a potential role for immunotherapy in the first-line treatment of advanced HCC and noted that the clinically meaningful improvement in response rates with nivolumab, along with the checkpoint inhibitor’s favorable safety profile in this study, raise the possibility of its selection in this setting.

“In a hypothetical scenario in which both options ... were available and reimbursed, and if quality of life was shown to be better with nivolumab ... clinicians and patients may favor the option with a more tolerable safety profile,” she said in the press release.

She added, however, that at this point conclusions should be made cautiously and the high cost of immunotherapy should be considered.

Dr. Lamarca also highlighted the finding that patients with high PD-L1 expression had an increased response rate only in the nivolumab arm. This suggests a potential role for PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in advanced HCC, but more research is needed to better understand how to select patients for immunotherapy, she said, adding that the lack of a reliable biomarker may have contributed to the study’s failure to show improved OS with nivolumab.

“In addition, the study design with a ‘high’ predefined threshold of statistical significance is generating confusion in the community, with potentially beneficial therapies generating statistically negative studies,” she noted.

CheckMate 459 was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Yau is an advisor and/or consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, and reported honoraria from the company to his institution. Dr. Lamarca reported honoraria, consultation fees, travel funding, and/or education funding from Eisai, Nutricia, Ipsen, Pfizer, Bayer, AAA, Sirtex, Delcath, Novartis, and Mylan, as well as participation in company-sponsored speaker bureaus for Pfizer, Ipsen, Merck, and Incyte.

SOURCE: Yau T et al. ESMO 2019, Abstract LBA38-PR

REPORTING FROM ESMO 2019

New practice guideline: CRC screening isn’t necessary for low-risk patients aged 50-75 years

Patients 50-79 years old with a demonstrably low risk of developing the disease within 15 years probably don’t need to be screened for colorectal cancer. But if their risk of disease is at least 3% over 15 years, patients should be screened, Lise M. Helsingen, MD, and colleagues wrote in BMJ (2019;367:l5515 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5515).

For these patients, “We suggest screening with one of the four screening options: fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every year, FIT every 2 years, a single sigmoidoscopy, or a single colonoscopy,” wrote Dr. Helsingen of the University of Oslo, and her team.

She chaired a 22-member international panel that developed a collaborative effort from the MAGIC research and innovation program as a part of the BMJ Rapid Recommendations project. The team reviewed 12 research papers comprising almost 1.4 million patients from Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Follow-up ranged from 0 to 19.5 years for colorectal cancer incidence and up to 30 years for mortality.

Because of the dearth of relevant data in some studies, however, the projected outcomes had to be simulated, with benefits and harms calculations based on 100% screening adherence. However, the team noted, it’s impossible to achieve complete adherence. Most studies of colorectal screening don’t exceed a 50% adherence level.

“All the modeling data are of low certainty. It is a useful indication, but there is a high chance that new evidence will show a smaller or larger benefit, which in turn may alter these recommendations.”

Compared with no screening, all four screening models reduced the risk of colorectal cancer mortality to a similar level.

- FIT every year, 59%.

- FIT every 2 years, 50%.

- Single sigmoidoscopy, 52%.

- Single colonoscopy, 67%.

Screening had less of an impact on reducing the incidence of colorectal cancer:

- FIT every 2 years, 0.05%.

- FIT every year, 0.15%.

- Single sigmoidoscopy, 27%.

- Single colonoscopy, 34%.

The panel also assessed potential harms. Among almost 1 million patients, the colonoscopy-related mortality rate was 0.03 per 1,000 procedures. The perforation rate was 0.8 per 1,000 colonoscopies after a positive fecal test, and 1.4 per 1,000 screened with sigmoidoscopy. The bleeding rate was 1.9 per 1,000 colonoscopies performed after a positive fecal test, and 3-4 per 1,000 screened with sigmoidoscopy.

Successful implementation of these recommendations hinges on accurate risk assessment, however. The team recommended the QCancer platform as “one of the best performing models for both men and women.”

The calculator includes age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol use, family history of gastrointestinal cancer, personal history of other cancers, diabetes, ulcerative colitis, colonic polyps, and body mass index.

“We suggest this model because it is available as an online calculator; includes only risk factors available in routine health care; has been validated in a population separate from the derivation population; has reasonable discriminatory ability; and has a good fit between predicted and observed outcomes. In addition, it is the only online risk calculator we know of that predicts risk over a 15-year time horizon.”

The team stressed that their recommendations can’t be applied to all patients. Because evidence for both screening recommendations was weak – largely because of the dearth of supporting data – patients and physicians should cocreate a personalized screening plan.

“Several factors influence individuals’ decisions whether to be screened, even when they are presented with the same information,” the authors said. These include variation in an individual’s values and preferences, a close balance of benefits versus harms and burdens, and personal preference.

“Some individuals may value a minimally invasive test such as FIT, and the possibility of invasive screening with colonoscopy might put them off screening altogether. Those who most value preventing colorectal cancer or avoiding repeated testing are likely to choose sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.”

The authors had no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: BMJ 2019;367:l5515. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5515.

There is compelling evidence that CRC screening of average-risk individuals is effective – screening with one of several modalities can reduce CRC incidence and mortality in average-risk individuals. Various guidelines throughout the world have recommended screening, usually beginning at age 50 years, in a one-size-fits-all manner. Despite our knowledge that different people have a different lifetime risk of CRC, no prior guidelines have suggested that risk stratification be built into the decision making.

All of the recommendations in this practice guideline are weak because they are derived from models that lack adequate precision. Nevertheless, the authors have proposed a new approach to CRC screening, similar to management plans for patients with cardiovascular disease. Before adopting such an approach, we need to be more comfortable with the precision of the risk estimates. These estimates, derived entirely from demographic and clinical information, may be enhanced by genomic data to achieve more precision. Further data on the willingness of the public to accept no screening if their risk is below a certain threshold needs to be evaluated. Despite these issues, the guideline presents a provocative approach which demands our attention.

David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, is professor of medicine and chief of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. He is Past President of the AGA Institute. He has no conflicts of interest.

There is compelling evidence that CRC screening of average-risk individuals is effective – screening with one of several modalities can reduce CRC incidence and mortality in average-risk individuals. Various guidelines throughout the world have recommended screening, usually beginning at age 50 years, in a one-size-fits-all manner. Despite our knowledge that different people have a different lifetime risk of CRC, no prior guidelines have suggested that risk stratification be built into the decision making.

All of the recommendations in this practice guideline are weak because they are derived from models that lack adequate precision. Nevertheless, the authors have proposed a new approach to CRC screening, similar to management plans for patients with cardiovascular disease. Before adopting such an approach, we need to be more comfortable with the precision of the risk estimates. These estimates, derived entirely from demographic and clinical information, may be enhanced by genomic data to achieve more precision. Further data on the willingness of the public to accept no screening if their risk is below a certain threshold needs to be evaluated. Despite these issues, the guideline presents a provocative approach which demands our attention.

David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, is professor of medicine and chief of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. He is Past President of the AGA Institute. He has no conflicts of interest.

There is compelling evidence that CRC screening of average-risk individuals is effective – screening with one of several modalities can reduce CRC incidence and mortality in average-risk individuals. Various guidelines throughout the world have recommended screening, usually beginning at age 50 years, in a one-size-fits-all manner. Despite our knowledge that different people have a different lifetime risk of CRC, no prior guidelines have suggested that risk stratification be built into the decision making.

All of the recommendations in this practice guideline are weak because they are derived from models that lack adequate precision. Nevertheless, the authors have proposed a new approach to CRC screening, similar to management plans for patients with cardiovascular disease. Before adopting such an approach, we need to be more comfortable with the precision of the risk estimates. These estimates, derived entirely from demographic and clinical information, may be enhanced by genomic data to achieve more precision. Further data on the willingness of the public to accept no screening if their risk is below a certain threshold needs to be evaluated. Despite these issues, the guideline presents a provocative approach which demands our attention.

David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, is professor of medicine and chief of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. He is Past President of the AGA Institute. He has no conflicts of interest.

Patients 50-79 years old with a demonstrably low risk of developing the disease within 15 years probably don’t need to be screened for colorectal cancer. But if their risk of disease is at least 3% over 15 years, patients should be screened, Lise M. Helsingen, MD, and colleagues wrote in BMJ (2019;367:l5515 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5515).

For these patients, “We suggest screening with one of the four screening options: fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every year, FIT every 2 years, a single sigmoidoscopy, or a single colonoscopy,” wrote Dr. Helsingen of the University of Oslo, and her team.

She chaired a 22-member international panel that developed a collaborative effort from the MAGIC research and innovation program as a part of the BMJ Rapid Recommendations project. The team reviewed 12 research papers comprising almost 1.4 million patients from Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Follow-up ranged from 0 to 19.5 years for colorectal cancer incidence and up to 30 years for mortality.

Because of the dearth of relevant data in some studies, however, the projected outcomes had to be simulated, with benefits and harms calculations based on 100% screening adherence. However, the team noted, it’s impossible to achieve complete adherence. Most studies of colorectal screening don’t exceed a 50% adherence level.

“All the modeling data are of low certainty. It is a useful indication, but there is a high chance that new evidence will show a smaller or larger benefit, which in turn may alter these recommendations.”

Compared with no screening, all four screening models reduced the risk of colorectal cancer mortality to a similar level.

- FIT every year, 59%.

- FIT every 2 years, 50%.

- Single sigmoidoscopy, 52%.

- Single colonoscopy, 67%.

Screening had less of an impact on reducing the incidence of colorectal cancer:

- FIT every 2 years, 0.05%.

- FIT every year, 0.15%.

- Single sigmoidoscopy, 27%.

- Single colonoscopy, 34%.

The panel also assessed potential harms. Among almost 1 million patients, the colonoscopy-related mortality rate was 0.03 per 1,000 procedures. The perforation rate was 0.8 per 1,000 colonoscopies after a positive fecal test, and 1.4 per 1,000 screened with sigmoidoscopy. The bleeding rate was 1.9 per 1,000 colonoscopies performed after a positive fecal test, and 3-4 per 1,000 screened with sigmoidoscopy.

Successful implementation of these recommendations hinges on accurate risk assessment, however. The team recommended the QCancer platform as “one of the best performing models for both men and women.”

The calculator includes age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol use, family history of gastrointestinal cancer, personal history of other cancers, diabetes, ulcerative colitis, colonic polyps, and body mass index.

“We suggest this model because it is available as an online calculator; includes only risk factors available in routine health care; has been validated in a population separate from the derivation population; has reasonable discriminatory ability; and has a good fit between predicted and observed outcomes. In addition, it is the only online risk calculator we know of that predicts risk over a 15-year time horizon.”

The team stressed that their recommendations can’t be applied to all patients. Because evidence for both screening recommendations was weak – largely because of the dearth of supporting data – patients and physicians should cocreate a personalized screening plan.

“Several factors influence individuals’ decisions whether to be screened, even when they are presented with the same information,” the authors said. These include variation in an individual’s values and preferences, a close balance of benefits versus harms and burdens, and personal preference.

“Some individuals may value a minimally invasive test such as FIT, and the possibility of invasive screening with colonoscopy might put them off screening altogether. Those who most value preventing colorectal cancer or avoiding repeated testing are likely to choose sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.”

The authors had no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: BMJ 2019;367:l5515. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5515.

Patients 50-79 years old with a demonstrably low risk of developing the disease within 15 years probably don’t need to be screened for colorectal cancer. But if their risk of disease is at least 3% over 15 years, patients should be screened, Lise M. Helsingen, MD, and colleagues wrote in BMJ (2019;367:l5515 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5515).

For these patients, “We suggest screening with one of the four screening options: fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every year, FIT every 2 years, a single sigmoidoscopy, or a single colonoscopy,” wrote Dr. Helsingen of the University of Oslo, and her team.

She chaired a 22-member international panel that developed a collaborative effort from the MAGIC research and innovation program as a part of the BMJ Rapid Recommendations project. The team reviewed 12 research papers comprising almost 1.4 million patients from Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Follow-up ranged from 0 to 19.5 years for colorectal cancer incidence and up to 30 years for mortality.

Because of the dearth of relevant data in some studies, however, the projected outcomes had to be simulated, with benefits and harms calculations based on 100% screening adherence. However, the team noted, it’s impossible to achieve complete adherence. Most studies of colorectal screening don’t exceed a 50% adherence level.

“All the modeling data are of low certainty. It is a useful indication, but there is a high chance that new evidence will show a smaller or larger benefit, which in turn may alter these recommendations.”

Compared with no screening, all four screening models reduced the risk of colorectal cancer mortality to a similar level.

- FIT every year, 59%.

- FIT every 2 years, 50%.

- Single sigmoidoscopy, 52%.

- Single colonoscopy, 67%.

Screening had less of an impact on reducing the incidence of colorectal cancer:

- FIT every 2 years, 0.05%.

- FIT every year, 0.15%.

- Single sigmoidoscopy, 27%.

- Single colonoscopy, 34%.

The panel also assessed potential harms. Among almost 1 million patients, the colonoscopy-related mortality rate was 0.03 per 1,000 procedures. The perforation rate was 0.8 per 1,000 colonoscopies after a positive fecal test, and 1.4 per 1,000 screened with sigmoidoscopy. The bleeding rate was 1.9 per 1,000 colonoscopies performed after a positive fecal test, and 3-4 per 1,000 screened with sigmoidoscopy.

Successful implementation of these recommendations hinges on accurate risk assessment, however. The team recommended the QCancer platform as “one of the best performing models for both men and women.”

The calculator includes age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol use, family history of gastrointestinal cancer, personal history of other cancers, diabetes, ulcerative colitis, colonic polyps, and body mass index.

“We suggest this model because it is available as an online calculator; includes only risk factors available in routine health care; has been validated in a population separate from the derivation population; has reasonable discriminatory ability; and has a good fit between predicted and observed outcomes. In addition, it is the only online risk calculator we know of that predicts risk over a 15-year time horizon.”

The team stressed that their recommendations can’t be applied to all patients. Because evidence for both screening recommendations was weak – largely because of the dearth of supporting data – patients and physicians should cocreate a personalized screening plan.

“Several factors influence individuals’ decisions whether to be screened, even when they are presented with the same information,” the authors said. These include variation in an individual’s values and preferences, a close balance of benefits versus harms and burdens, and personal preference.

“Some individuals may value a minimally invasive test such as FIT, and the possibility of invasive screening with colonoscopy might put them off screening altogether. Those who most value preventing colorectal cancer or avoiding repeated testing are likely to choose sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.”

The authors had no financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: BMJ 2019;367:l5515. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5515.

FROM BMJ

Smoking Out the Truth About Pot and Cancer

MINNEAPOLIS -- Medical professionals within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) can’t prescribe cannabis or certify patients to be able to get it. VA pharmacists can’t dispense it. Still, “we’re asked about it plenty,” a hospice and palliative care specialist told colleagues, at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO).

That brings up a big question, said Michael Stellini, MD, MS, FACP, FAAHPM, of Wayne State University, Karmanos Cancer Center, and the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center, in Detroit Michigan: “Should sick people be smoking pot?”

Even the question itself isn’t a simple one to answer since smoking isn’t the only way to consume cannabis for medical purposes. And figuring out the best advice is difficult. As Dr. Stellini said, there’s plenty of uncertainty about crucial cannabis topics like safety and benefits.

Dr. Stellini offered a number of facts and tips about cannabis in medicine.

Understand ‘qualifying conditions’ in your state

In states with legal medical marijuana, he said, physicians do not prescribe marijuana. However, they may certify that patients are eligible to get the drug for medical purposes if they meet certain qualifications.

A typical list of qualifying conditions includes diseases such as cancer, glaucoma, HIV/AIDS and Crohn’s disease. Qualifying conditions also tend to include treatments for severe diseases that produce wasting syndrome, severe and chronic pain, severe nausea, seizures and severe and persistent muscle spasm.

In Michigan, where Dr. Stellini practices, a panel in 2018 approved a long list of added qualifying conditions such as chronic pain, obsessive compulsive disorder and arthritis. But the panel rejected other conditions such as anxiety, asthma, panic attacks and schizophrenia.

Vaporizers are an alternative to joints, but...

Vaporizers are commonly used as an alternative to smoking marijuana joints, Dr. Stellini said, and they don’t significantly release tars or much if any carbon monoxide. While research is limited, he said, use of vaporizers hasn’t been linked to more lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“Vaping” is another option, but it’s been linked to dozens of deaths and hundreds of cases of illness in recent weeks. Many patients have reported using products that contain THC, a component of marijuana.

Other delivery methods exist

Marijuana can be ingested in liquid and solid food. “But edibles can have a slow onset of action compared to vaporizing or smoking,” Dr. Stellini said. “You might over-indulge. When users get to their steady state, they might have some adverse effects [AEs].”

Marijuana still has risks

Cannabis use has a long list of well-known AEs linked to the THC component. The most common are drowsiness, fatigue, dizziness, dry mouth, anxiety, cognitive effects, cough, and nausea, Dr. Stellini said. More serious AEs such as psychosis have been reported.

And, of course, users of cannabis with THC get high if they use enough.

A 2017 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report linked cannabis use to a higher risk of motor vehicle accidents. Still, Dr. Stellini said, “it’s relatively safe with respect to mortality, especially compared to opioids.”1

Risk of use in cancer may be low

Research suggest that patients with cancer use cannabis as much as other people and perhaps even more, Dr. Stellini said. But are they facing any extra risks? In general, he said, it doesn’t appear that way.

Cannabis seems to be safe when used with chemotherapy, he said, and drug-drug interactions in cancer appear to be rare. Some studies have suggested that cannabinoids—a component of marijuana—may be an effective treatment for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

However, he said, 1 study has raised a red flag about a possible interaction with cancer immunotherapy. Researchers found evidence that patients who used cannabis had lower tumor response rates to nivolomab for advanced melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and renal clear cell carcinoma. However, survival wasn’t affected.2

Meanwhile, he said, there’s no strong evidence that cannabis is a useful treatment for cancer, he said, although it’s worth investigating.

Cannabidiol is the hot new product

Cannabidiol, also known as CBD, has become hugely popular, Dr. Stellini said. It is derived from hemp and doesn’t cause a “buzz” like cannabis.

Due to lack of regulation, he said, buyers should beware. And, he said, CBD has multiple EAs. Standard doses can cause drowsiness, fatigue, dizziness, dry mouth, hypotension and lightheadedness.

Dr. Stellini reports no relevant disclosures.

1. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017.

2. Taha T, Meiri D, Talhamy S, Wollner M, Peer A, Bar-Sela G. Cannabis impacts tumor response rate to nivolumab in patients with advanced malignancies. Oncologist. 2019;24(4):549-554.

MINNEAPOLIS -- Medical professionals within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) can’t prescribe cannabis or certify patients to be able to get it. VA pharmacists can’t dispense it. Still, “we’re asked about it plenty,” a hospice and palliative care specialist told colleagues, at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO).

That brings up a big question, said Michael Stellini, MD, MS, FACP, FAAHPM, of Wayne State University, Karmanos Cancer Center, and the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center, in Detroit Michigan: “Should sick people be smoking pot?”

Even the question itself isn’t a simple one to answer since smoking isn’t the only way to consume cannabis for medical purposes. And figuring out the best advice is difficult. As Dr. Stellini said, there’s plenty of uncertainty about crucial cannabis topics like safety and benefits.

Dr. Stellini offered a number of facts and tips about cannabis in medicine.

Understand ‘qualifying conditions’ in your state

In states with legal medical marijuana, he said, physicians do not prescribe marijuana. However, they may certify that patients are eligible to get the drug for medical purposes if they meet certain qualifications.

A typical list of qualifying conditions includes diseases such as cancer, glaucoma, HIV/AIDS and Crohn’s disease. Qualifying conditions also tend to include treatments for severe diseases that produce wasting syndrome, severe and chronic pain, severe nausea, seizures and severe and persistent muscle spasm.

In Michigan, where Dr. Stellini practices, a panel in 2018 approved a long list of added qualifying conditions such as chronic pain, obsessive compulsive disorder and arthritis. But the panel rejected other conditions such as anxiety, asthma, panic attacks and schizophrenia.

Vaporizers are an alternative to joints, but...

Vaporizers are commonly used as an alternative to smoking marijuana joints, Dr. Stellini said, and they don’t significantly release tars or much if any carbon monoxide. While research is limited, he said, use of vaporizers hasn’t been linked to more lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“Vaping” is another option, but it’s been linked to dozens of deaths and hundreds of cases of illness in recent weeks. Many patients have reported using products that contain THC, a component of marijuana.

Other delivery methods exist

Marijuana can be ingested in liquid and solid food. “But edibles can have a slow onset of action compared to vaporizing or smoking,” Dr. Stellini said. “You might over-indulge. When users get to their steady state, they might have some adverse effects [AEs].”

Marijuana still has risks

Cannabis use has a long list of well-known AEs linked to the THC component. The most common are drowsiness, fatigue, dizziness, dry mouth, anxiety, cognitive effects, cough, and nausea, Dr. Stellini said. More serious AEs such as psychosis have been reported.

And, of course, users of cannabis with THC get high if they use enough.

A 2017 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report linked cannabis use to a higher risk of motor vehicle accidents. Still, Dr. Stellini said, “it’s relatively safe with respect to mortality, especially compared to opioids.”1

Risk of use in cancer may be low

Research suggest that patients with cancer use cannabis as much as other people and perhaps even more, Dr. Stellini said. But are they facing any extra risks? In general, he said, it doesn’t appear that way.

Cannabis seems to be safe when used with chemotherapy, he said, and drug-drug interactions in cancer appear to be rare. Some studies have suggested that cannabinoids—a component of marijuana—may be an effective treatment for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

However, he said, 1 study has raised a red flag about a possible interaction with cancer immunotherapy. Researchers found evidence that patients who used cannabis had lower tumor response rates to nivolomab for advanced melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and renal clear cell carcinoma. However, survival wasn’t affected.2

Meanwhile, he said, there’s no strong evidence that cannabis is a useful treatment for cancer, he said, although it’s worth investigating.

Cannabidiol is the hot new product

Cannabidiol, also known as CBD, has become hugely popular, Dr. Stellini said. It is derived from hemp and doesn’t cause a “buzz” like cannabis.

Due to lack of regulation, he said, buyers should beware. And, he said, CBD has multiple EAs. Standard doses can cause drowsiness, fatigue, dizziness, dry mouth, hypotension and lightheadedness.

Dr. Stellini reports no relevant disclosures.

MINNEAPOLIS -- Medical professionals within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) can’t prescribe cannabis or certify patients to be able to get it. VA pharmacists can’t dispense it. Still, “we’re asked about it plenty,” a hospice and palliative care specialist told colleagues, at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO).

That brings up a big question, said Michael Stellini, MD, MS, FACP, FAAHPM, of Wayne State University, Karmanos Cancer Center, and the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center, in Detroit Michigan: “Should sick people be smoking pot?”

Even the question itself isn’t a simple one to answer since smoking isn’t the only way to consume cannabis for medical purposes. And figuring out the best advice is difficult. As Dr. Stellini said, there’s plenty of uncertainty about crucial cannabis topics like safety and benefits.

Dr. Stellini offered a number of facts and tips about cannabis in medicine.

Understand ‘qualifying conditions’ in your state

In states with legal medical marijuana, he said, physicians do not prescribe marijuana. However, they may certify that patients are eligible to get the drug for medical purposes if they meet certain qualifications.

A typical list of qualifying conditions includes diseases such as cancer, glaucoma, HIV/AIDS and Crohn’s disease. Qualifying conditions also tend to include treatments for severe diseases that produce wasting syndrome, severe and chronic pain, severe nausea, seizures and severe and persistent muscle spasm.

In Michigan, where Dr. Stellini practices, a panel in 2018 approved a long list of added qualifying conditions such as chronic pain, obsessive compulsive disorder and arthritis. But the panel rejected other conditions such as anxiety, asthma, panic attacks and schizophrenia.

Vaporizers are an alternative to joints, but...

Vaporizers are commonly used as an alternative to smoking marijuana joints, Dr. Stellini said, and they don’t significantly release tars or much if any carbon monoxide. While research is limited, he said, use of vaporizers hasn’t been linked to more lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“Vaping” is another option, but it’s been linked to dozens of deaths and hundreds of cases of illness in recent weeks. Many patients have reported using products that contain THC, a component of marijuana.

Other delivery methods exist

Marijuana can be ingested in liquid and solid food. “But edibles can have a slow onset of action compared to vaporizing or smoking,” Dr. Stellini said. “You might over-indulge. When users get to their steady state, they might have some adverse effects [AEs].”

Marijuana still has risks

Cannabis use has a long list of well-known AEs linked to the THC component. The most common are drowsiness, fatigue, dizziness, dry mouth, anxiety, cognitive effects, cough, and nausea, Dr. Stellini said. More serious AEs such as psychosis have been reported.

And, of course, users of cannabis with THC get high if they use enough.

A 2017 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report linked cannabis use to a higher risk of motor vehicle accidents. Still, Dr. Stellini said, “it’s relatively safe with respect to mortality, especially compared to opioids.”1

Risk of use in cancer may be low

Research suggest that patients with cancer use cannabis as much as other people and perhaps even more, Dr. Stellini said. But are they facing any extra risks? In general, he said, it doesn’t appear that way.

Cannabis seems to be safe when used with chemotherapy, he said, and drug-drug interactions in cancer appear to be rare. Some studies have suggested that cannabinoids—a component of marijuana—may be an effective treatment for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

However, he said, 1 study has raised a red flag about a possible interaction with cancer immunotherapy. Researchers found evidence that patients who used cannabis had lower tumor response rates to nivolomab for advanced melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and renal clear cell carcinoma. However, survival wasn’t affected.2

Meanwhile, he said, there’s no strong evidence that cannabis is a useful treatment for cancer, he said, although it’s worth investigating.

Cannabidiol is the hot new product

Cannabidiol, also known as CBD, has become hugely popular, Dr. Stellini said. It is derived from hemp and doesn’t cause a “buzz” like cannabis.

Due to lack of regulation, he said, buyers should beware. And, he said, CBD has multiple EAs. Standard doses can cause drowsiness, fatigue, dizziness, dry mouth, hypotension and lightheadedness.

Dr. Stellini reports no relevant disclosures.

1. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017.

2. Taha T, Meiri D, Talhamy S, Wollner M, Peer A, Bar-Sela G. Cannabis impacts tumor response rate to nivolumab in patients with advanced malignancies. Oncologist. 2019;24(4):549-554.

1. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017.

2. Taha T, Meiri D, Talhamy S, Wollner M, Peer A, Bar-Sela G. Cannabis impacts tumor response rate to nivolumab in patients with advanced malignancies. Oncologist. 2019;24(4):549-554.

For Cancer Survivors, Nutrition Is Empowering

MINNEAPOLIS -- Ignore the big health claims about vitamin supplements, pork, and nitrate-free food products. Meet patients “where they are,” even if that means you focus first on helping a morbidly obese patient maintain her weight instead of losing pounds. And use nutrition to empower patients and reduce the risk of cancer recurrence.

Dianne Piepenburg, MS, RDN, CSO, a certified oncology nutritionist at the Malcolm Randall VA Medical Center in Gainesville, Florida, offered these tips and more in a presentation about nutrition for cancer survivors. She spoke at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO).

According to the National Institutes of Health, an estimated 17 million cancer survivors live in the US, accounting for 5% of the population. Nearly two-thirds are aged ≥ 65 years.1

Piepenburg highlighted the existence of certified specialists in oncology nutrition (CSOs). To be certified, registered dietitian nutritionists must have worked in that job for at least 2 years, have at least 2,000 hours of practice experience within the past 5 years and pass a board exam every 5 years.

Oncology nutritionists seek to empower cancer survivors to regain equilibrium in their lives, she said. “When a patient is told what scan to have next, what blood work they have to have, what treatment they need to be on, they feel they’re losing control,” she said. “Nutrition gives the power back to them, and they feel like there’s something they can do that’s in their control.”

Piepenburg urged colleagues to “meet patients where they are.” She gave the example of a patient with breast cancer whose body mass index is in the 50s, making her morbidly obese. “Our discussion wasn’t, ‘Let’s start [losing weight] today.’ Instead, I said, ‘Can we at least prevent you from gaining any more weight?’ She thought she could at least do that, try to recuperate a bit, and then start looking at a healthy weight loss. We’ll start there and circle back in a few months and see where we’re at.”

Piepenburg urged colleagues to bring exercise into the discussion. “We need people to be physically active no matter what phase of their survivorship journey they are in,” she said.

What about people who say, “I’ve never exercised a day in my life”? Her response: “I tell folks that we need them to move more. Maybe they’re walking to the mailbox or 3 laps around the house that day.”

Oncology patients should also watch sugar, meat, and processed foods. Refined sugar, fast food and processed food should be limited, Piepenburg said, along with red meats, such as beef, pork and lamb.

“Pork is not the ‘other white meat.’ How many of you grew up seeing and hearing that in the 1970s and 1980s? It’s a red meat, and it’s metabolized like a red meat.”

Advise patients to limit bacon, sausage, and lunch meat, she said, “even if they say, ‘I bought the nitrate-free and it’s really healthy for me.’”

It’s okay to eat some red meat, she said, “but there’s a tipping point. Tell them they can have some red meat but have it as a treat and please focus more on plant-based proteins—nuts, beans, legumes. But it’s tough for a lot of our veterans who grew up on meat and potatoes, and the only vegetable they eat is corn.”

It’s tough to limit grilling in a place like Minnesota, Piepenburg said, where the prime grilling season is short, and locals go a bit nuts when it’s nice enough outside. “I tell them to at least marinate the meat and put it on indirect heat.”

Finally, she encouraged oncology care providers to not fall for vitamin hype. Don’t rely on supplements for cancer prevention, she said. With some exceptions, she said, research has suggested they don’t work, and a 1990s study of beta-carotene and retinyl palmitate (vitamin A) in lung cancer was halted because patients actually fared worse on the regimen, although the effects didn’t seem to persist.2

1. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Office of Cancer Survivorship. Statistics. Updated February 8, 2019. Accessed October 7, 2019.

2. Goodman GE, Thornquist MD, Balmes J, et al. The Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial: incidence of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality during 6-year follow-up after stopping beta-carotene and retinol supplements. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(23):1743-1750.

MINNEAPOLIS -- Ignore the big health claims about vitamin supplements, pork, and nitrate-free food products. Meet patients “where they are,” even if that means you focus first on helping a morbidly obese patient maintain her weight instead of losing pounds. And use nutrition to empower patients and reduce the risk of cancer recurrence.