User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

The Use of Lung Cancer Screening to Increase Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Diagnosis in Veterans Affairs Primary Care

The Use of Lung Cancer Screening to Increase Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Diagnosis in Veterans Affairs Primary Care

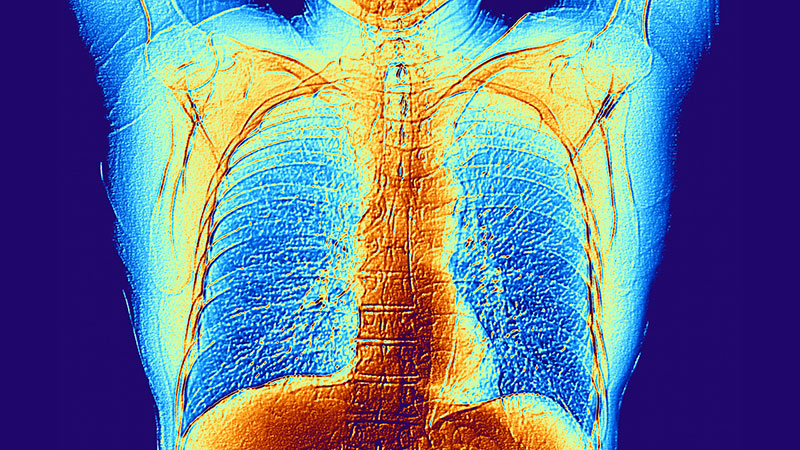

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provide care for patients with higher rates of many diseases—diabetes, heart disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and stroke—compared to the nonveteran population. 1 Due to the medical complexities of these diseases, they are often misdiagnosed or not diagnosed at all.

COPD is hiding in plain sight, impacting quality of life and burdening US health care systems.2 Research has yielded new treatments and evidence-based guidelines; however, COPD remains underdiagnosed. Only 13 million of the estimated 79 million US adults with COPD aged 20 to 79 years have been formally diagnosed.3 By the time patients are diagnosed, the disease is often advanced, and therapies are less effective. In 2 large studies of patients with COPD symptoms, later diagnosis was associated with worse outcomes.4,5

Veterans have a higher prevalence of COPD (8%-19%) than nonveterans (6%), likely due to higher rates of smoking and service-related exposures, especially among veterans of post-9/11 conflicts.6,7 Veterans do not always report symptoms and PCPs may not ask about symptoms, leading to underdiagnosis.8 The combination of high likelihood and underdetection of COPD presents a challenge and a target for VA quality improvement (QI).

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends against screening asymptomatic patients for COPD. However, both the USPSTF and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Report advocate for active case finding in primary care clinics to determine whether high-risk patients, such as smokers, experience COPD symptoms and warrant spirometry. 9,10 To make early COPD diagnoses, clinicians may use questionnaires alone or in combination with handheld peak expiratory flow rate measurements.11,12 Formal spirometry, considered the gold standard for COPD diagnosis, is ordered for patients who report COPD symptoms (ie, shortness of breath with exertion) or who have both COPD symptoms and reduced peak flow rates.

A systematic review and meta-analysis found that while the combination of questionnaires and peak flows was the more effective strategy overall, questionnaires alone were also valuable for identifying patients with possible COPD.13 Implementation of either screening method in primary care practices would be challenging. In a simulation study that applied chronic disease and preventive care guidelines to hypothetical patient panels, the time required for PCPs to provide guideline-recommended chronic and preventive care in addition to acute care far exceeded 8 hours per day, even in team-based settings.14 Overburdened PCPs are therefore unlikely to accept additional tasks like COPD case finding.

Why don’t patients report their pulmonary symptoms? Patients may not recognize the symptoms as evidence of COPD. Others may be afraid of a COPD diagnosis or the stigma that is associated with it.15 Perhaps they believe COPD treatment is ineffective because of lung damage from smoking. Some patients may not want to know if they have COPD, while others reduce activity levels to avoid symptoms.16

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROJECT

Given the high prevalence of COPD among veterans and the potential for underdiagnosis, VA Northeast Ohio Healthcare System (VANEOHS) internal medicine residents and faculty assessed the state of COPD diagnosis in its primary care clinic with a QI project in 2022. Patients in the clinic between August 1, 2015, and November 30, 2022, with an International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) COPD diagnosis code (J44) in the electronic health record were included. Of 157 included patients, 105 patients who had prior spirometry testing were excluded. Of the 52 patients with diagnosed COPD and no spirometry testing, 30 patients had computed tomography (CT) findings consistent with COPD (ie, airway thickening, emphysema, air trapping) that was performed for CT lung cancer screening (LCS).17 Twenty-three of these 30 patients were contacted by phone. All 23 were ever smokers and 13 reported COPD symptoms. The PCPs of the symptomatic patients were then contacted. Spirometry was ordered for all 13 patients and completed by 7. Three spirometry tests confirmed the COPD diagnosis. One PCP initiated inhaler therapy for a patient with newly diagnosed COPD.

All 11 PCPs of symptomatic patients were interviewed (many had > 1 symptomatic patient). They reported being unaware of patients’ COPD symptoms because the patients did not mention them, noting that screening for COPD was not a priority.

Role of Lung Cancer Screening

VA PCPs use electronic health record clinical reminders to track tests, consults, chronic disease education, cancer screenings, and routine health maintenance. A clinical reminder already exists (based on USPSTF recommendations) for LCS for patients aged 50 to 80 years who have a smoking history of 20 pack years. Patients who meet these criteria would also be considered high risk for COPD.

The VANEOHS QI project suggests that previously undiagnosed patients with findings of COPD on LCS may also have symptoms of COPD. Therefore, we wondered whether the LCS clinical reminder could serve a second purpose by prompting PCPs to ask veterans who meet LCS criteria about their COPD symptoms.

In 2022, about 13 million patients were eligible for LCS.18 Patients who qualify for LCS are at high risk for other cardiopulmonary disorders, such as COPD and coronary artery disease. Lung cancer is detected in only 1% of patients screened with CT at baseline. However, more often LCS yields evidence of additional cardiopulmonary disorders, such as emphysema or coronary artery calcifications. The International Early Lung Cancer Program (I-ELCAP) and the National Lung Cancer Screening Trial (NLST), which included > 79,000 patients, found evidence of emphysema on CT imaging in 24% and 31% of cases, respectively.19,20 In both cohorts, > 80% of patients with emphysema on CT imaging had no prior history of COPD.

In a 2022 article summarizing the potential impact of CT LCS on COPD diagnosis, Mulshine et al suggest that detection of emphysema on CT LCS provides “earlier recognition for PCPs to identify patients who would benefit from detailed symptom screening to prompt spirometry for COPD detection” and additional motivation for tobacco cessation.21 The VANEOHS QI project was developed and implemented prior to I-ELCAP or NLST reporting results but reinforces the value of CT LCS for COPD diagnosis.

Early diagnosis of COPD remains challenging because PCPs do not ask, patients do not tell, and symptoms can easily be dismissed. However, earlier diagnosis of COPD in symptomatic patients improves outcomes.3,4 To bridge this gap, VA PCPs and primary care patient aligned care teams (PACTs) need to commit to probing high-risk patients for COPD symptoms and ordering spirometry for those who are symptomatic. To accomplish this task, primary care teams need help.

The VANEOHS QI project confirmed that some patients with evidence of COPD on CT have symptoms of COPD that they did not share with their PCPs and suggests that LCS can be used as a dual action case finding method to screen both for lung cancer and COPD. We propose that patients who are eligible for LCS should also be probed for COPD symptoms at their clinic visits; for symptomatic patients, spirometry should be ordered, and COPD evidence-based management should be initiated when spirometry results are consistent with COPD. Annual probing for COPD symptoms could be considered in asymptomatic patients with ongoing tobacco use or emphysema on CT, since they may develop symptoms in the future. This new case-finding method bypasses the need for time-prohibitive questionnaires or peak flow measurements.

Future Opportunities

VA PCPs juggle many priorities and despite the simplicity of this new case finding COPD method, it may be unintentionally overlooked. PCPs often run out of time or may forget to ask patients about COPD symptoms when ordering LCS.

Future innovations to increase COPD diagnosis could include the creation of a yearly VA clinical reminder linked to the tobacco use reminder that has check boxes asking about symptoms of COPD in current and prior smokers. If patients have COPD symptoms, the reminder can prompt the ordering of spirometry. Similar reminders could be implemented to identify veterans with exposures to burn pits or other military environmental exposures who may have COPD symptoms. Another possible way to increase COPD diagnosis would be a partnership between primary care and the VA LCS program where patients receiving screening are asked about COPD symptoms during their LCS interviews and PACTs are alerted to order spirometry for symptomatic patients.

Elusive no longer! We can pull the veil back on COPD diagnosis and identify patients with possible COPD earlier in their course using their eligibility for LCS as a yearly reminder to probe them for symptoms. While not all patients who undergo LCS—even those with evidence of COPD on CT—will have COPD symptoms, symptoms may develop over time. LCS provides the possibility of 2 diagnoses from 1 test. This is an opportunity we cannot afford to miss.

- Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, et al. Exploring health outcomes for U.S. veterans compared to non-veterans from 2003 to 2019. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(5):604. doi:10.3390/healthcare90506064

- Bamonti PM, Fischer I, Moye J, Poghosyan H, Pietrzak RH. Obstructive respiratory disease in U.S. veterans: prevalence, characteristics, and health burden. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;176:140-147. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.05.053

- Criner RN, Han MK. COPD care in the 21st century: a public health priority. Respir Care. 2018;63(5):591-600. doi:10.4187/respcare.06276

- Larsson K, Janson C, Ställberg B, et al. Impact of COPD diagnosis timing on clinical and economic outcomes: the ARCTIC observational cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:995-1008. doi:10.2147/COPD.S195382

- Kostikas K, Price D, Gutzwiller FS, et al. Clinical impact and healthcare resource utilization associated with early versus late COPD diagnosis in patients from UK CPRD Database. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:1729- 1738. doi:10.2147/COPD.S255414

- Bamonti PM, Robinson SA, Wan ES, Moy ML. Improving physiological, physical, and psychological health outcomes: a narrative review in US veterans with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

- Savitz DA, Woskie SR, Bello A, et al. Deployment to military bases with open burn pits and respiratory and cardiovascular disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e247629. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.7629

- Murphy DE, Chaudhry Z, Almoosa KF, Panos RJ. High prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among veterans in the urban midwest. Mil Med. 2011;176(5):552-560. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-10-00377

- Guirguis-Blake JM, Senger CA, Webber EM, Mularski RA, Whitlock EP. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1378-1393. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2654

- Capriotti T, Tomy R, Morales M. COPD updates: 2023 GOLD Report for primary care providers. Clinical Advisor. May 9, 2023. Accessed May 14, 2025. https://www.clinicaladvisor.com/features/copd-updates-2023-gold-report-primary-care/

- Leidy NK, Martinez FJ, Malley KG, et al. Can CAPTURE be used to identify undiagnosed patients with mild- to- moderate COPD likely to benefit from treatment? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:1901-1912. doi:10.2147/COPD.S152226

- Jithoo A, Enright PL, Burney P, et al. Case-finding options for COPD: results from the burden of obstructive lung disease study. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(3):548-555. doi:10.1183/09031936.00132011

- Haroon SM, Jordan RE, O’Beirne-Elliman J, Adab P. Effectiveness of case finding strategies for COPD in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2015;25:15056. doi:10.1038/npjpcrm.2015.56

- Porter J, Boyd C, Skandari MR, Laiteerapong N. Revisiting the time needed to provide adult primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(1)147-155. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07707-x

- Woo S, Zhou W, Larson JL. Stigma experiences in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an integrative review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:1647- 1659. doi:10.2147/COPD.S306874

- Aaron SD, Montes de Oca M, Celli B, et al. Early diagnosis and treatment of COPD: the costs and benefits of case finding. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;209(8):928-937. doi:10.1164/rccm.202311-2120PP

- Kwon A, Lee C, Arafah A, Klein M, Namboodiri S, Lee C. Increasing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) diagnosis with pulmonary function testing for patients with chest imaging evidence of COPD. Poster presented at: Society of General Internal Medicine Midwest Regional Meeting; October 19-20, 2023; Chicago, IL.

- Henderson LM, Su I, Rivera MP, et al. Prevalence of lung cancer screening in the US, 2022. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e243190. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3190

- Steiger D, Siddiqi MF, Yip R, Yankelevitz DF, Henschke CI; I-ELCAP investigators. The importance of low-dose CT screening to identify emphysema in asymptomatic participants with and without a prior diagnosis of COPD. Clin Imaging. 2021;78:136-141. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.03.012

- Pinsky PF, Lynch DA, Gierada DS. Incidental findings on low-dose CT scan lung cancer screenings and deaths from respiratory diseases. Chest. 2022;161(4):1092-1100. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.11.015

- Mulshine JL, Aldigé CR, Ambrose LF, et al. Emphysema detection in the course of lung cancer screening: optimizing a rare opportunity to impact population health. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023;20(4):499- 503. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202207-631PS

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provide care for patients with higher rates of many diseases—diabetes, heart disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and stroke—compared to the nonveteran population. 1 Due to the medical complexities of these diseases, they are often misdiagnosed or not diagnosed at all.

COPD is hiding in plain sight, impacting quality of life and burdening US health care systems.2 Research has yielded new treatments and evidence-based guidelines; however, COPD remains underdiagnosed. Only 13 million of the estimated 79 million US adults with COPD aged 20 to 79 years have been formally diagnosed.3 By the time patients are diagnosed, the disease is often advanced, and therapies are less effective. In 2 large studies of patients with COPD symptoms, later diagnosis was associated with worse outcomes.4,5

Veterans have a higher prevalence of COPD (8%-19%) than nonveterans (6%), likely due to higher rates of smoking and service-related exposures, especially among veterans of post-9/11 conflicts.6,7 Veterans do not always report symptoms and PCPs may not ask about symptoms, leading to underdiagnosis.8 The combination of high likelihood and underdetection of COPD presents a challenge and a target for VA quality improvement (QI).

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends against screening asymptomatic patients for COPD. However, both the USPSTF and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Report advocate for active case finding in primary care clinics to determine whether high-risk patients, such as smokers, experience COPD symptoms and warrant spirometry. 9,10 To make early COPD diagnoses, clinicians may use questionnaires alone or in combination with handheld peak expiratory flow rate measurements.11,12 Formal spirometry, considered the gold standard for COPD diagnosis, is ordered for patients who report COPD symptoms (ie, shortness of breath with exertion) or who have both COPD symptoms and reduced peak flow rates.

A systematic review and meta-analysis found that while the combination of questionnaires and peak flows was the more effective strategy overall, questionnaires alone were also valuable for identifying patients with possible COPD.13 Implementation of either screening method in primary care practices would be challenging. In a simulation study that applied chronic disease and preventive care guidelines to hypothetical patient panels, the time required for PCPs to provide guideline-recommended chronic and preventive care in addition to acute care far exceeded 8 hours per day, even in team-based settings.14 Overburdened PCPs are therefore unlikely to accept additional tasks like COPD case finding.

Why don’t patients report their pulmonary symptoms? Patients may not recognize the symptoms as evidence of COPD. Others may be afraid of a COPD diagnosis or the stigma that is associated with it.15 Perhaps they believe COPD treatment is ineffective because of lung damage from smoking. Some patients may not want to know if they have COPD, while others reduce activity levels to avoid symptoms.16

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROJECT

Given the high prevalence of COPD among veterans and the potential for underdiagnosis, VA Northeast Ohio Healthcare System (VANEOHS) internal medicine residents and faculty assessed the state of COPD diagnosis in its primary care clinic with a QI project in 2022. Patients in the clinic between August 1, 2015, and November 30, 2022, with an International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) COPD diagnosis code (J44) in the electronic health record were included. Of 157 included patients, 105 patients who had prior spirometry testing were excluded. Of the 52 patients with diagnosed COPD and no spirometry testing, 30 patients had computed tomography (CT) findings consistent with COPD (ie, airway thickening, emphysema, air trapping) that was performed for CT lung cancer screening (LCS).17 Twenty-three of these 30 patients were contacted by phone. All 23 were ever smokers and 13 reported COPD symptoms. The PCPs of the symptomatic patients were then contacted. Spirometry was ordered for all 13 patients and completed by 7. Three spirometry tests confirmed the COPD diagnosis. One PCP initiated inhaler therapy for a patient with newly diagnosed COPD.

All 11 PCPs of symptomatic patients were interviewed (many had > 1 symptomatic patient). They reported being unaware of patients’ COPD symptoms because the patients did not mention them, noting that screening for COPD was not a priority.

Role of Lung Cancer Screening

VA PCPs use electronic health record clinical reminders to track tests, consults, chronic disease education, cancer screenings, and routine health maintenance. A clinical reminder already exists (based on USPSTF recommendations) for LCS for patients aged 50 to 80 years who have a smoking history of 20 pack years. Patients who meet these criteria would also be considered high risk for COPD.

The VANEOHS QI project suggests that previously undiagnosed patients with findings of COPD on LCS may also have symptoms of COPD. Therefore, we wondered whether the LCS clinical reminder could serve a second purpose by prompting PCPs to ask veterans who meet LCS criteria about their COPD symptoms.

In 2022, about 13 million patients were eligible for LCS.18 Patients who qualify for LCS are at high risk for other cardiopulmonary disorders, such as COPD and coronary artery disease. Lung cancer is detected in only 1% of patients screened with CT at baseline. However, more often LCS yields evidence of additional cardiopulmonary disorders, such as emphysema or coronary artery calcifications. The International Early Lung Cancer Program (I-ELCAP) and the National Lung Cancer Screening Trial (NLST), which included > 79,000 patients, found evidence of emphysema on CT imaging in 24% and 31% of cases, respectively.19,20 In both cohorts, > 80% of patients with emphysema on CT imaging had no prior history of COPD.

In a 2022 article summarizing the potential impact of CT LCS on COPD diagnosis, Mulshine et al suggest that detection of emphysema on CT LCS provides “earlier recognition for PCPs to identify patients who would benefit from detailed symptom screening to prompt spirometry for COPD detection” and additional motivation for tobacco cessation.21 The VANEOHS QI project was developed and implemented prior to I-ELCAP or NLST reporting results but reinforces the value of CT LCS for COPD diagnosis.

Early diagnosis of COPD remains challenging because PCPs do not ask, patients do not tell, and symptoms can easily be dismissed. However, earlier diagnosis of COPD in symptomatic patients improves outcomes.3,4 To bridge this gap, VA PCPs and primary care patient aligned care teams (PACTs) need to commit to probing high-risk patients for COPD symptoms and ordering spirometry for those who are symptomatic. To accomplish this task, primary care teams need help.

The VANEOHS QI project confirmed that some patients with evidence of COPD on CT have symptoms of COPD that they did not share with their PCPs and suggests that LCS can be used as a dual action case finding method to screen both for lung cancer and COPD. We propose that patients who are eligible for LCS should also be probed for COPD symptoms at their clinic visits; for symptomatic patients, spirometry should be ordered, and COPD evidence-based management should be initiated when spirometry results are consistent with COPD. Annual probing for COPD symptoms could be considered in asymptomatic patients with ongoing tobacco use or emphysema on CT, since they may develop symptoms in the future. This new case-finding method bypasses the need for time-prohibitive questionnaires or peak flow measurements.

Future Opportunities

VA PCPs juggle many priorities and despite the simplicity of this new case finding COPD method, it may be unintentionally overlooked. PCPs often run out of time or may forget to ask patients about COPD symptoms when ordering LCS.

Future innovations to increase COPD diagnosis could include the creation of a yearly VA clinical reminder linked to the tobacco use reminder that has check boxes asking about symptoms of COPD in current and prior smokers. If patients have COPD symptoms, the reminder can prompt the ordering of spirometry. Similar reminders could be implemented to identify veterans with exposures to burn pits or other military environmental exposures who may have COPD symptoms. Another possible way to increase COPD diagnosis would be a partnership between primary care and the VA LCS program where patients receiving screening are asked about COPD symptoms during their LCS interviews and PACTs are alerted to order spirometry for symptomatic patients.

Elusive no longer! We can pull the veil back on COPD diagnosis and identify patients with possible COPD earlier in their course using their eligibility for LCS as a yearly reminder to probe them for symptoms. While not all patients who undergo LCS—even those with evidence of COPD on CT—will have COPD symptoms, symptoms may develop over time. LCS provides the possibility of 2 diagnoses from 1 test. This is an opportunity we cannot afford to miss.

Primary care practitioners (PCPs) in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provide care for patients with higher rates of many diseases—diabetes, heart disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and stroke—compared to the nonveteran population. 1 Due to the medical complexities of these diseases, they are often misdiagnosed or not diagnosed at all.

COPD is hiding in plain sight, impacting quality of life and burdening US health care systems.2 Research has yielded new treatments and evidence-based guidelines; however, COPD remains underdiagnosed. Only 13 million of the estimated 79 million US adults with COPD aged 20 to 79 years have been formally diagnosed.3 By the time patients are diagnosed, the disease is often advanced, and therapies are less effective. In 2 large studies of patients with COPD symptoms, later diagnosis was associated with worse outcomes.4,5

Veterans have a higher prevalence of COPD (8%-19%) than nonveterans (6%), likely due to higher rates of smoking and service-related exposures, especially among veterans of post-9/11 conflicts.6,7 Veterans do not always report symptoms and PCPs may not ask about symptoms, leading to underdiagnosis.8 The combination of high likelihood and underdetection of COPD presents a challenge and a target for VA quality improvement (QI).

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends against screening asymptomatic patients for COPD. However, both the USPSTF and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Report advocate for active case finding in primary care clinics to determine whether high-risk patients, such as smokers, experience COPD symptoms and warrant spirometry. 9,10 To make early COPD diagnoses, clinicians may use questionnaires alone or in combination with handheld peak expiratory flow rate measurements.11,12 Formal spirometry, considered the gold standard for COPD diagnosis, is ordered for patients who report COPD symptoms (ie, shortness of breath with exertion) or who have both COPD symptoms and reduced peak flow rates.

A systematic review and meta-analysis found that while the combination of questionnaires and peak flows was the more effective strategy overall, questionnaires alone were also valuable for identifying patients with possible COPD.13 Implementation of either screening method in primary care practices would be challenging. In a simulation study that applied chronic disease and preventive care guidelines to hypothetical patient panels, the time required for PCPs to provide guideline-recommended chronic and preventive care in addition to acute care far exceeded 8 hours per day, even in team-based settings.14 Overburdened PCPs are therefore unlikely to accept additional tasks like COPD case finding.

Why don’t patients report their pulmonary symptoms? Patients may not recognize the symptoms as evidence of COPD. Others may be afraid of a COPD diagnosis or the stigma that is associated with it.15 Perhaps they believe COPD treatment is ineffective because of lung damage from smoking. Some patients may not want to know if they have COPD, while others reduce activity levels to avoid symptoms.16

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROJECT

Given the high prevalence of COPD among veterans and the potential for underdiagnosis, VA Northeast Ohio Healthcare System (VANEOHS) internal medicine residents and faculty assessed the state of COPD diagnosis in its primary care clinic with a QI project in 2022. Patients in the clinic between August 1, 2015, and November 30, 2022, with an International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) COPD diagnosis code (J44) in the electronic health record were included. Of 157 included patients, 105 patients who had prior spirometry testing were excluded. Of the 52 patients with diagnosed COPD and no spirometry testing, 30 patients had computed tomography (CT) findings consistent with COPD (ie, airway thickening, emphysema, air trapping) that was performed for CT lung cancer screening (LCS).17 Twenty-three of these 30 patients were contacted by phone. All 23 were ever smokers and 13 reported COPD symptoms. The PCPs of the symptomatic patients were then contacted. Spirometry was ordered for all 13 patients and completed by 7. Three spirometry tests confirmed the COPD diagnosis. One PCP initiated inhaler therapy for a patient with newly diagnosed COPD.

All 11 PCPs of symptomatic patients were interviewed (many had > 1 symptomatic patient). They reported being unaware of patients’ COPD symptoms because the patients did not mention them, noting that screening for COPD was not a priority.

Role of Lung Cancer Screening

VA PCPs use electronic health record clinical reminders to track tests, consults, chronic disease education, cancer screenings, and routine health maintenance. A clinical reminder already exists (based on USPSTF recommendations) for LCS for patients aged 50 to 80 years who have a smoking history of 20 pack years. Patients who meet these criteria would also be considered high risk for COPD.

The VANEOHS QI project suggests that previously undiagnosed patients with findings of COPD on LCS may also have symptoms of COPD. Therefore, we wondered whether the LCS clinical reminder could serve a second purpose by prompting PCPs to ask veterans who meet LCS criteria about their COPD symptoms.

In 2022, about 13 million patients were eligible for LCS.18 Patients who qualify for LCS are at high risk for other cardiopulmonary disorders, such as COPD and coronary artery disease. Lung cancer is detected in only 1% of patients screened with CT at baseline. However, more often LCS yields evidence of additional cardiopulmonary disorders, such as emphysema or coronary artery calcifications. The International Early Lung Cancer Program (I-ELCAP) and the National Lung Cancer Screening Trial (NLST), which included > 79,000 patients, found evidence of emphysema on CT imaging in 24% and 31% of cases, respectively.19,20 In both cohorts, > 80% of patients with emphysema on CT imaging had no prior history of COPD.

In a 2022 article summarizing the potential impact of CT LCS on COPD diagnosis, Mulshine et al suggest that detection of emphysema on CT LCS provides “earlier recognition for PCPs to identify patients who would benefit from detailed symptom screening to prompt spirometry for COPD detection” and additional motivation for tobacco cessation.21 The VANEOHS QI project was developed and implemented prior to I-ELCAP or NLST reporting results but reinforces the value of CT LCS for COPD diagnosis.

Early diagnosis of COPD remains challenging because PCPs do not ask, patients do not tell, and symptoms can easily be dismissed. However, earlier diagnosis of COPD in symptomatic patients improves outcomes.3,4 To bridge this gap, VA PCPs and primary care patient aligned care teams (PACTs) need to commit to probing high-risk patients for COPD symptoms and ordering spirometry for those who are symptomatic. To accomplish this task, primary care teams need help.

The VANEOHS QI project confirmed that some patients with evidence of COPD on CT have symptoms of COPD that they did not share with their PCPs and suggests that LCS can be used as a dual action case finding method to screen both for lung cancer and COPD. We propose that patients who are eligible for LCS should also be probed for COPD symptoms at their clinic visits; for symptomatic patients, spirometry should be ordered, and COPD evidence-based management should be initiated when spirometry results are consistent with COPD. Annual probing for COPD symptoms could be considered in asymptomatic patients with ongoing tobacco use or emphysema on CT, since they may develop symptoms in the future. This new case-finding method bypasses the need for time-prohibitive questionnaires or peak flow measurements.

Future Opportunities

VA PCPs juggle many priorities and despite the simplicity of this new case finding COPD method, it may be unintentionally overlooked. PCPs often run out of time or may forget to ask patients about COPD symptoms when ordering LCS.

Future innovations to increase COPD diagnosis could include the creation of a yearly VA clinical reminder linked to the tobacco use reminder that has check boxes asking about symptoms of COPD in current and prior smokers. If patients have COPD symptoms, the reminder can prompt the ordering of spirometry. Similar reminders could be implemented to identify veterans with exposures to burn pits or other military environmental exposures who may have COPD symptoms. Another possible way to increase COPD diagnosis would be a partnership between primary care and the VA LCS program where patients receiving screening are asked about COPD symptoms during their LCS interviews and PACTs are alerted to order spirometry for symptomatic patients.

Elusive no longer! We can pull the veil back on COPD diagnosis and identify patients with possible COPD earlier in their course using their eligibility for LCS as a yearly reminder to probe them for symptoms. While not all patients who undergo LCS—even those with evidence of COPD on CT—will have COPD symptoms, symptoms may develop over time. LCS provides the possibility of 2 diagnoses from 1 test. This is an opportunity we cannot afford to miss.

- Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, et al. Exploring health outcomes for U.S. veterans compared to non-veterans from 2003 to 2019. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(5):604. doi:10.3390/healthcare90506064

- Bamonti PM, Fischer I, Moye J, Poghosyan H, Pietrzak RH. Obstructive respiratory disease in U.S. veterans: prevalence, characteristics, and health burden. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;176:140-147. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.05.053

- Criner RN, Han MK. COPD care in the 21st century: a public health priority. Respir Care. 2018;63(5):591-600. doi:10.4187/respcare.06276

- Larsson K, Janson C, Ställberg B, et al. Impact of COPD diagnosis timing on clinical and economic outcomes: the ARCTIC observational cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:995-1008. doi:10.2147/COPD.S195382

- Kostikas K, Price D, Gutzwiller FS, et al. Clinical impact and healthcare resource utilization associated with early versus late COPD diagnosis in patients from UK CPRD Database. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:1729- 1738. doi:10.2147/COPD.S255414

- Bamonti PM, Robinson SA, Wan ES, Moy ML. Improving physiological, physical, and psychological health outcomes: a narrative review in US veterans with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

- Savitz DA, Woskie SR, Bello A, et al. Deployment to military bases with open burn pits and respiratory and cardiovascular disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e247629. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.7629

- Murphy DE, Chaudhry Z, Almoosa KF, Panos RJ. High prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among veterans in the urban midwest. Mil Med. 2011;176(5):552-560. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-10-00377

- Guirguis-Blake JM, Senger CA, Webber EM, Mularski RA, Whitlock EP. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1378-1393. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2654

- Capriotti T, Tomy R, Morales M. COPD updates: 2023 GOLD Report for primary care providers. Clinical Advisor. May 9, 2023. Accessed May 14, 2025. https://www.clinicaladvisor.com/features/copd-updates-2023-gold-report-primary-care/

- Leidy NK, Martinez FJ, Malley KG, et al. Can CAPTURE be used to identify undiagnosed patients with mild- to- moderate COPD likely to benefit from treatment? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:1901-1912. doi:10.2147/COPD.S152226

- Jithoo A, Enright PL, Burney P, et al. Case-finding options for COPD: results from the burden of obstructive lung disease study. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(3):548-555. doi:10.1183/09031936.00132011

- Haroon SM, Jordan RE, O’Beirne-Elliman J, Adab P. Effectiveness of case finding strategies for COPD in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2015;25:15056. doi:10.1038/npjpcrm.2015.56

- Porter J, Boyd C, Skandari MR, Laiteerapong N. Revisiting the time needed to provide adult primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(1)147-155. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07707-x

- Woo S, Zhou W, Larson JL. Stigma experiences in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an integrative review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:1647- 1659. doi:10.2147/COPD.S306874

- Aaron SD, Montes de Oca M, Celli B, et al. Early diagnosis and treatment of COPD: the costs and benefits of case finding. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;209(8):928-937. doi:10.1164/rccm.202311-2120PP

- Kwon A, Lee C, Arafah A, Klein M, Namboodiri S, Lee C. Increasing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) diagnosis with pulmonary function testing for patients with chest imaging evidence of COPD. Poster presented at: Society of General Internal Medicine Midwest Regional Meeting; October 19-20, 2023; Chicago, IL.

- Henderson LM, Su I, Rivera MP, et al. Prevalence of lung cancer screening in the US, 2022. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e243190. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3190

- Steiger D, Siddiqi MF, Yip R, Yankelevitz DF, Henschke CI; I-ELCAP investigators. The importance of low-dose CT screening to identify emphysema in asymptomatic participants with and without a prior diagnosis of COPD. Clin Imaging. 2021;78:136-141. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.03.012

- Pinsky PF, Lynch DA, Gierada DS. Incidental findings on low-dose CT scan lung cancer screenings and deaths from respiratory diseases. Chest. 2022;161(4):1092-1100. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.11.015

- Mulshine JL, Aldigé CR, Ambrose LF, et al. Emphysema detection in the course of lung cancer screening: optimizing a rare opportunity to impact population health. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023;20(4):499- 503. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202207-631PS

- Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, et al. Exploring health outcomes for U.S. veterans compared to non-veterans from 2003 to 2019. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(5):604. doi:10.3390/healthcare90506064

- Bamonti PM, Fischer I, Moye J, Poghosyan H, Pietrzak RH. Obstructive respiratory disease in U.S. veterans: prevalence, characteristics, and health burden. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;176:140-147. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.05.053

- Criner RN, Han MK. COPD care in the 21st century: a public health priority. Respir Care. 2018;63(5):591-600. doi:10.4187/respcare.06276

- Larsson K, Janson C, Ställberg B, et al. Impact of COPD diagnosis timing on clinical and economic outcomes: the ARCTIC observational cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:995-1008. doi:10.2147/COPD.S195382

- Kostikas K, Price D, Gutzwiller FS, et al. Clinical impact and healthcare resource utilization associated with early versus late COPD diagnosis in patients from UK CPRD Database. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:1729- 1738. doi:10.2147/COPD.S255414

- Bamonti PM, Robinson SA, Wan ES, Moy ML. Improving physiological, physical, and psychological health outcomes: a narrative review in US veterans with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

- Savitz DA, Woskie SR, Bello A, et al. Deployment to military bases with open burn pits and respiratory and cardiovascular disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(4):e247629. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.7629

- Murphy DE, Chaudhry Z, Almoosa KF, Panos RJ. High prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among veterans in the urban midwest. Mil Med. 2011;176(5):552-560. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-10-00377

- Guirguis-Blake JM, Senger CA, Webber EM, Mularski RA, Whitlock EP. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1378-1393. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2654

- Capriotti T, Tomy R, Morales M. COPD updates: 2023 GOLD Report for primary care providers. Clinical Advisor. May 9, 2023. Accessed May 14, 2025. https://www.clinicaladvisor.com/features/copd-updates-2023-gold-report-primary-care/

- Leidy NK, Martinez FJ, Malley KG, et al. Can CAPTURE be used to identify undiagnosed patients with mild- to- moderate COPD likely to benefit from treatment? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:1901-1912. doi:10.2147/COPD.S152226

- Jithoo A, Enright PL, Burney P, et al. Case-finding options for COPD: results from the burden of obstructive lung disease study. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(3):548-555. doi:10.1183/09031936.00132011

- Haroon SM, Jordan RE, O’Beirne-Elliman J, Adab P. Effectiveness of case finding strategies for COPD in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2015;25:15056. doi:10.1038/npjpcrm.2015.56

- Porter J, Boyd C, Skandari MR, Laiteerapong N. Revisiting the time needed to provide adult primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(1)147-155. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07707-x

- Woo S, Zhou W, Larson JL. Stigma experiences in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an integrative review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:1647- 1659. doi:10.2147/COPD.S306874

- Aaron SD, Montes de Oca M, Celli B, et al. Early diagnosis and treatment of COPD: the costs and benefits of case finding. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;209(8):928-937. doi:10.1164/rccm.202311-2120PP

- Kwon A, Lee C, Arafah A, Klein M, Namboodiri S, Lee C. Increasing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) diagnosis with pulmonary function testing for patients with chest imaging evidence of COPD. Poster presented at: Society of General Internal Medicine Midwest Regional Meeting; October 19-20, 2023; Chicago, IL.

- Henderson LM, Su I, Rivera MP, et al. Prevalence of lung cancer screening in the US, 2022. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e243190. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3190

- Steiger D, Siddiqi MF, Yip R, Yankelevitz DF, Henschke CI; I-ELCAP investigators. The importance of low-dose CT screening to identify emphysema in asymptomatic participants with and without a prior diagnosis of COPD. Clin Imaging. 2021;78:136-141. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.03.012

- Pinsky PF, Lynch DA, Gierada DS. Incidental findings on low-dose CT scan lung cancer screenings and deaths from respiratory diseases. Chest. 2022;161(4):1092-1100. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.11.015

- Mulshine JL, Aldigé CR, Ambrose LF, et al. Emphysema detection in the course of lung cancer screening: optimizing a rare opportunity to impact population health. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023;20(4):499- 503. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202207-631PS

The Use of Lung Cancer Screening to Increase Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Diagnosis in Veterans Affairs Primary Care

The Use of Lung Cancer Screening to Increase Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Diagnosis in Veterans Affairs Primary Care

When Patient-Centered Care Initiatives Align: Integrating VA Whole Health and Shared Decision-Making for Lung Cancer Screening

When Patient-Centered Care Initiatives Align: Integrating VA Whole Health and Shared Decision-Making for Lung Cancer Screening

The landmark Crossing the Quality Chasm report from the National Academy of Medicine identified patient- centered care as essential to health care quality. The report defines patientcentered care as “respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values.”1 Many health care systems, including the Veterans Health Administration, are transforming to a patient-centered model of care.2 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Whole Health System of Care initiative is a system-wide, cultural transformation. Within whole health, what matters most to the patient—including their preferences, needs, and values—is foundational to health care and meant to be essential in every clinical encounter. Whole health implementation includes a progressive rollout with health care practitioner (HCP) trainings across the VA.2

Shared decision-making (SDM) is a different but aligned patient-centered care concept. SDM is a process through which a decision or care plan, based on patients’ preferences, needs, and values, is made or developed.3-5 SDM is ideal in situations with equipoise (decisions with equivalent choices), individualized risks, and/or greater uncertainty of the net benefit, such as with lung cancer screening (LCS).3 SDM for LCS is required by the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and has been adopted by many US health care systems, including the VA.6,7 Early detection of lung cancer can reduce death by 20% at the population level.8 However, at the patient level there is wide variation in the risk of developing lung cancer and a range of potential harms.8 LCS follow-up procedures may be more invasive than with other cancer screenings. Thus, there is concern about the risk of false-positive results leading to unnecessary care or complications.8 Given this balance between benefit and harm and the differing patient value on the trade-offs of LCS, an individualized, patient-centered approach is essential when deciding whether LCS is the right choice for a specific patient.

Despite the importance of LCS SDM, observational studies have shown poor implementation in clinical encounters.9,10 HCP barriers include competing demands, limited time, lack of familiarity with and training in SDM, and beliefs biasing screening over no screening.11-13 Additionally, HCPs may assume that patients want them to make the decision. However, research has shown that patients actually want to be more involved in their health care decisions.14 One suggested strategy to overcome these barriers is aligning SDM for LCS within an organization’s broader patient-centered initiatives.15

This project sought to align the need for SDM for LCS and the broader VA whole health initiative as part of a multilevel strategy to implement SDM for LCS across Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 1.16

This article addresses HCP-level barriers. HCPs targeted are those typically involved in LCS. The VA utilizes LCS coordinators (LCSCs) in both centralized or consult models (in which LCSCs are involved in all aspects of screening) and hybrid models (in which primary care practitioners and LCSCs are both engaged in LCS tasks). The goal of this program was to generate areas of conceptual alignment between SDM and whole health as a first step in integrating these VA initiatives. This work was conducted as a foundation for an SDM for lung cancer HCP training and consultation initiative.

ALIGNMENT PROCESS

We reviewed relevant literature and resources for SDM and whole health. In reviewing the SDM literature, we included a sample of the most widely cited literature on the topic, and focused primarily on the systematic review by Bomhof-Roordink et al.4,5,17,18 This review provided a synthesis of SDM elements across SDM models and identified 53 different elements clustered into 24 components.4 The most common components were present in at least half of all SDM published models, including: make the decision, patient preferences, tailor information, deliberate, create choice awareness, and learn about the patient. Bomhof-Roordink et al provided the guiding framework for this conceptualization of SDM because that study included the available recent published SDM models.4

Second, published literature on VA whole health along with supplemental promotional and training materials were reviewed. The whole health materials included 2 sets of training slides developed for VA HCPs (available to VA employees): Implementing Whole Health in Clinical Care, which is focused on HCPs’ work with patients, and Whole Health for You and Me, which is about HCPs’ personal well-being.19 We also reviewed a publication describing the history of whole health and patient-facing online whole health tools.2,19

Each document was reviewed for key elements related to SDM, patient-centered care, and whole health. Using the 53 elements identified by Bomhof-Roordink et al, we reviewed and compared each element to the whole health materials to create the integrated model of SDM and whole health. We iteratively discussed and organized the elements until we reached consensus.

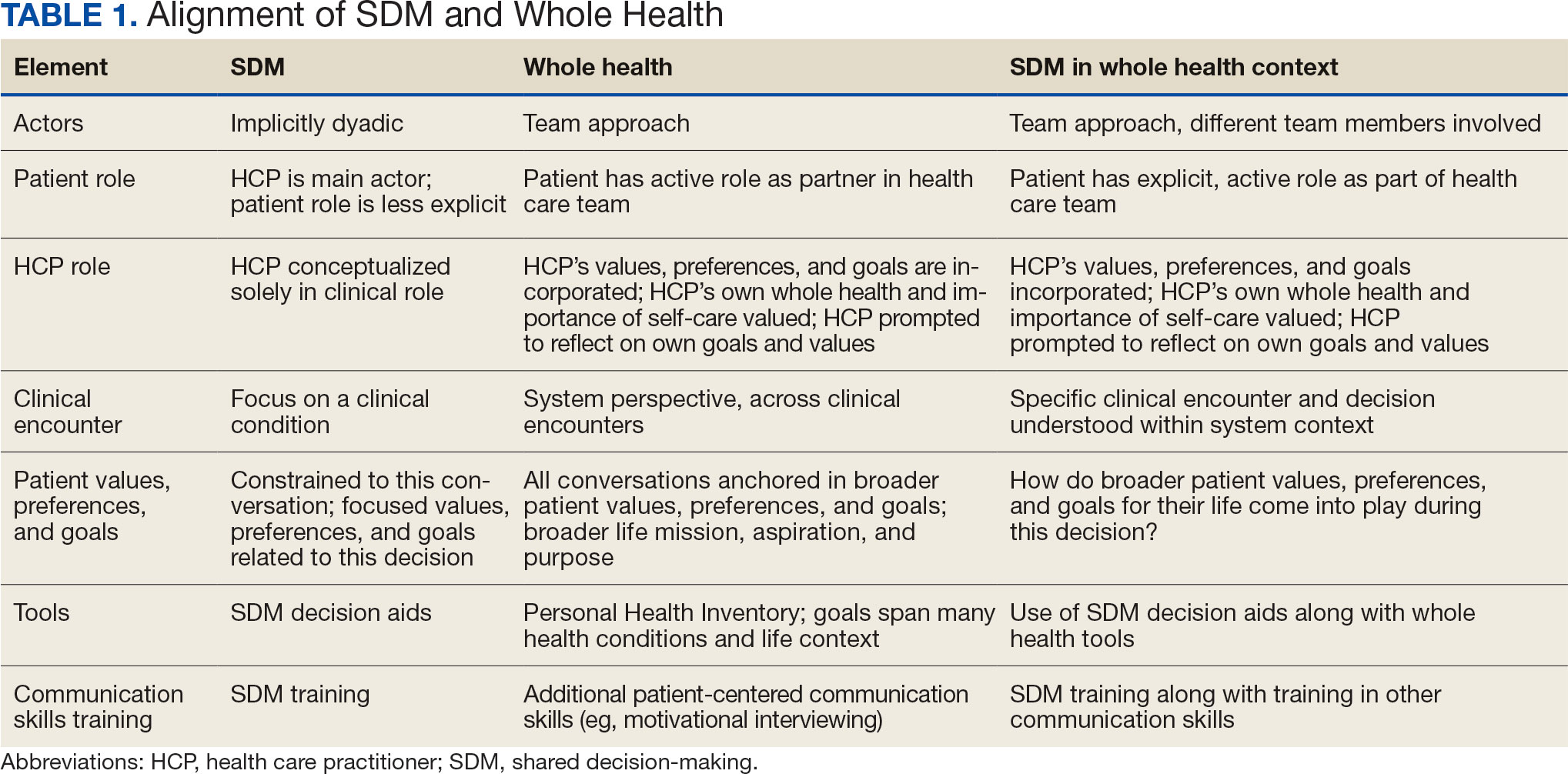

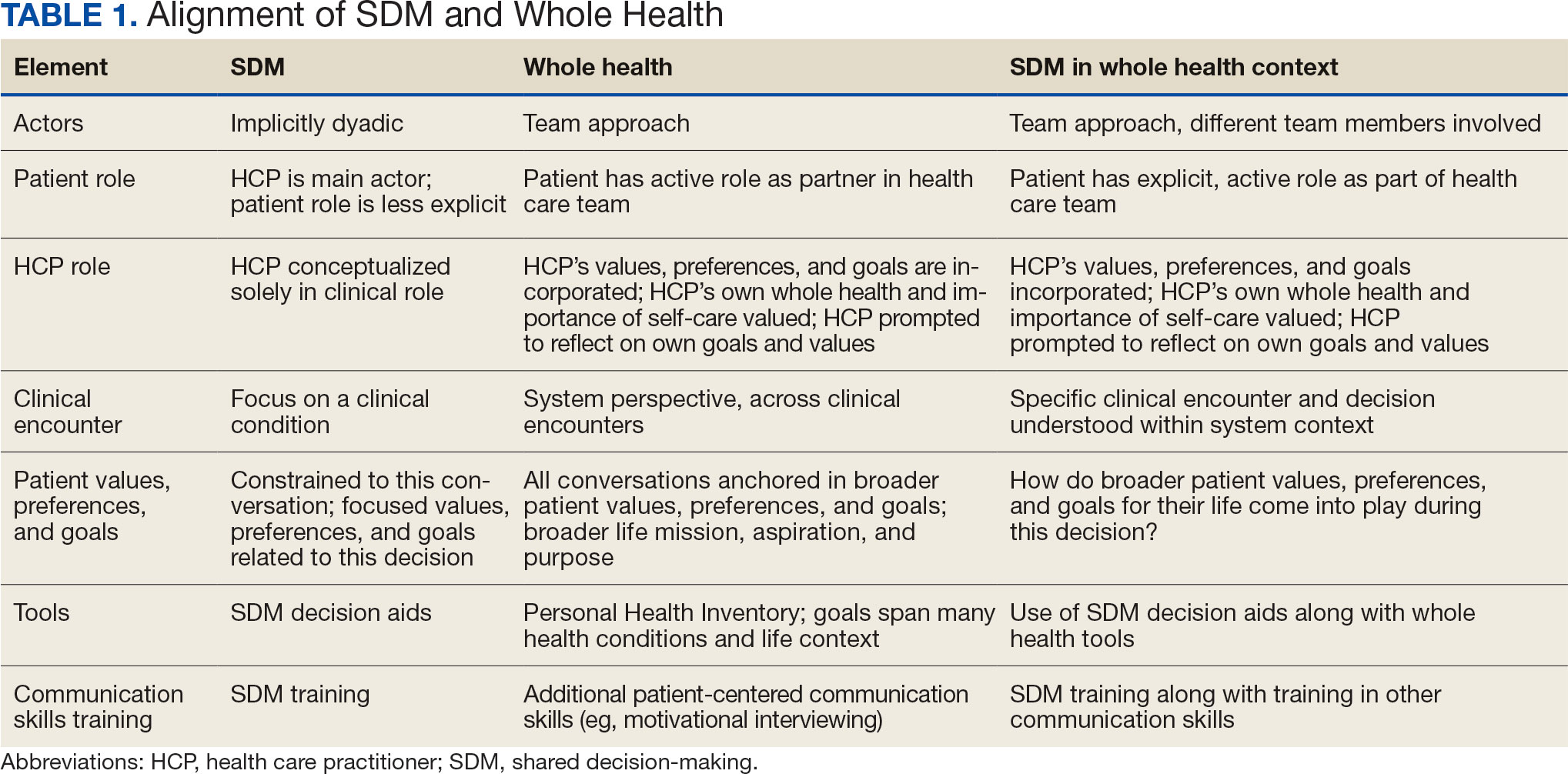

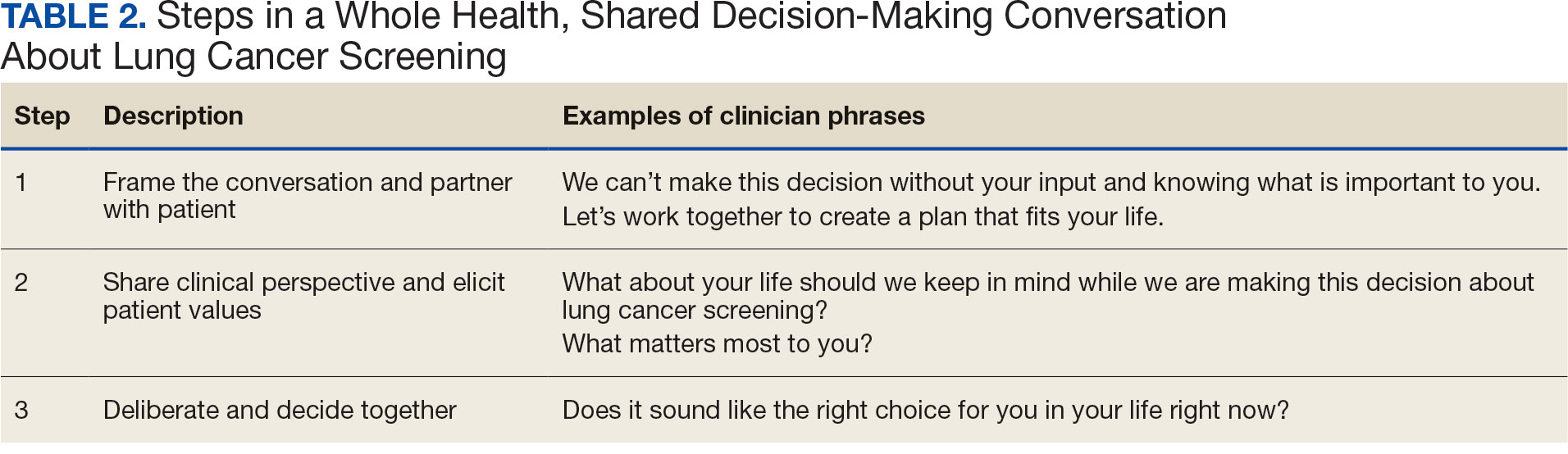

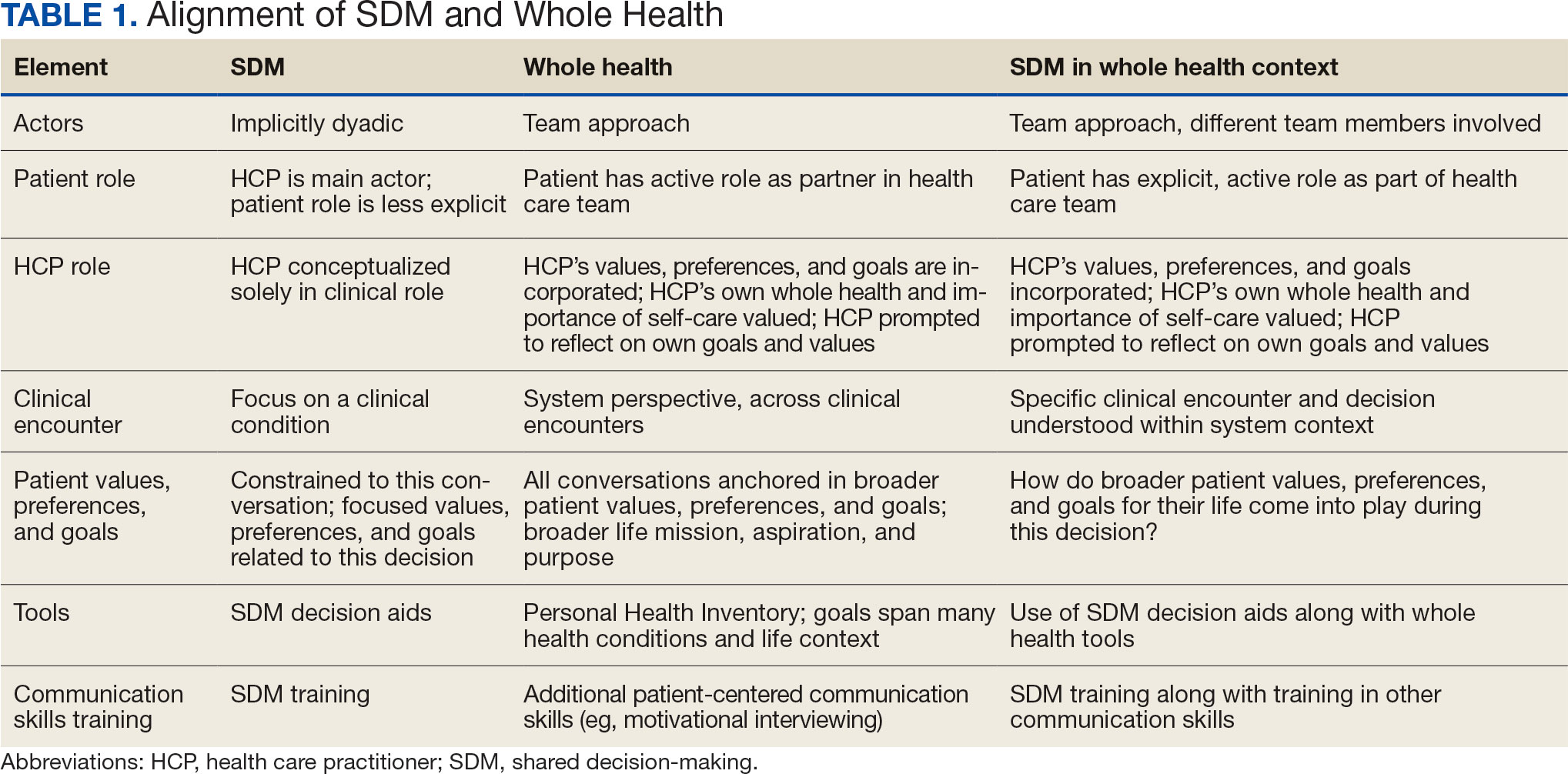

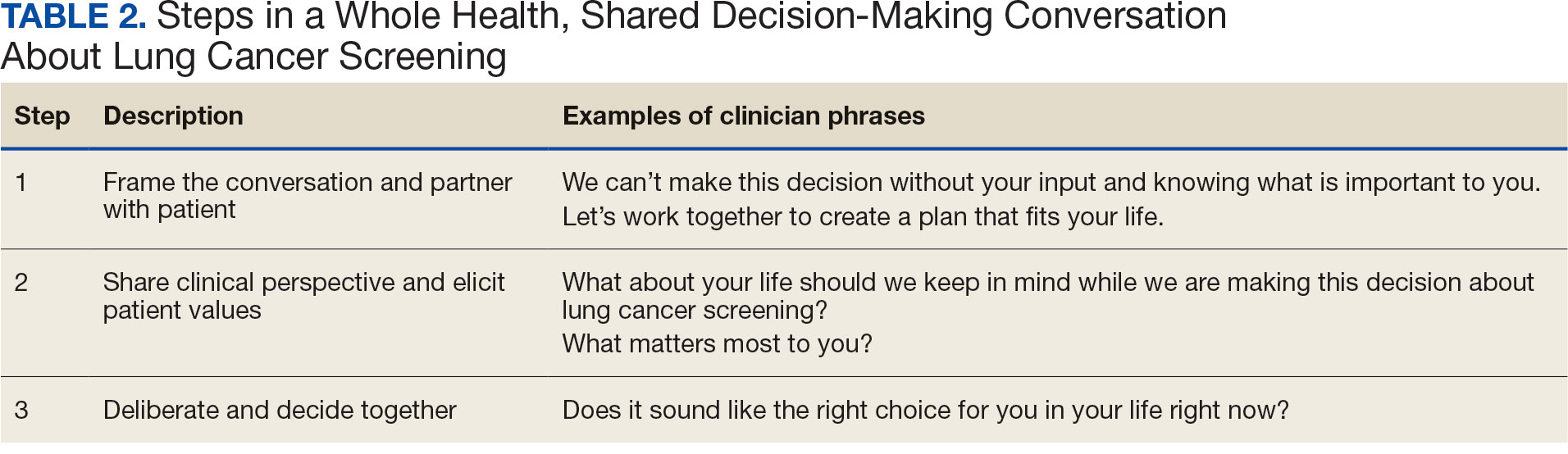

SDM and Whole Health Alignment

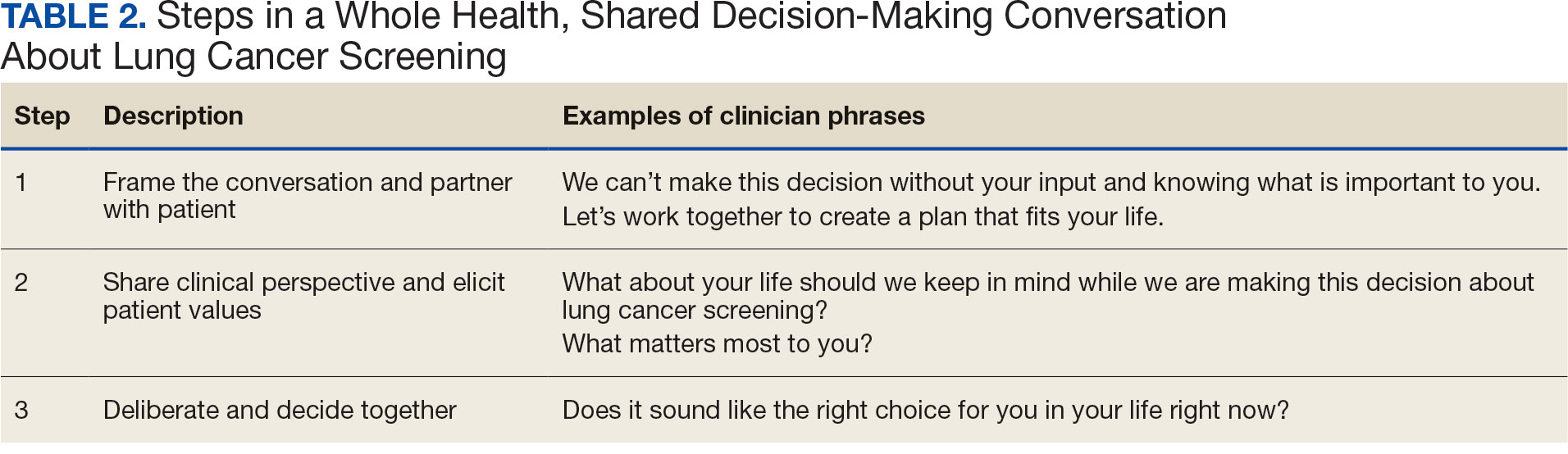

We created an integrated model of SDM for LCS within the context of the VA whole health initiative. This integrated model is directed at HCPs who would likely engage patients in discussions of LCS, including primary care practitioners and nurse coordinators. The model includes 3 steps for HCPs to follow that align SDM within whole health: (1) frame the conversation and partner with the patient; (2) share clinical perspective and elicit patient values; and (3) deliberate and decide together. For each step, the SDM elements, whole health elements, and integration of SDM and whole health are provided. Table 1 provides an overview of the similarities and differences between SDM and whole health. Example phrases that merge SDM and whole health for HCPs to use in patient conversations about LCS are included in Table 2.

STEP 1. FRAME THE CONVERSATION AND PARTNER WITH THE PATIENT

Shared decision-making. Traditional SDM literature includes an initial step of letting patients know that there is a choice to be made between ≥ 2 clinical options.4 Ancillary elements of this first step include asking patients their preferences about the degree to which they want to be involved in SDM and about how they like to receive information (eg, verbal, written, video). These steps open the SDM conversation and ensure the patient and HCP are on the same page before moving forward. For example, the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality SHARE model’s first step is for HCPs to communicate that choices exist and to invite the patient to be involved in decisions.20 Similarly, Elwyn’s 3-step SDM model begins with establishing that a choice exists and inviting patient input on making that choice.17

Whole health. Patients are encouraged to play an active role in their health care. Through whole health programs such as Taking Charge of My Life and Health, patients explore their values and set self-care goals.21 HCP whole health trainings teach and reinforce communication skills, including SDM, listening skills, and motivational interviewing.19

Shared decision-making/whole health integration. SDM and whole health both prioritize respect, compassion, and patients’ expertise. They focus on the patient-HCP relationship with an emphasis on fostering egalitarian interactions. HCPs frame the SDM conversation and partner with the patient so they know what to expect and who will be involved. This conversation is framed from the outset as a collaborative discussion. HCPs empower the patient to play an active role in decision-making and help them understand why their engagement is critical.

STEP 2. SHARE CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE AND ELICIT PATIENT VALUES

Shared decision-making. HCPs share clinical perspective on LCS tailored to individual patients while explicitly inviting the patient to share their preferences and values when thinking about whether to undergo LCS. HCPs give a balanced description of LCS, including the benefits and harms, tailored to the patient’s unique information needs and questions. Sharing clinical perspective also includes describing treatment options, the most common element across SDM models.4 Decision aids, which provide unbiased information and include a values clarification exercise, may be helpful in sharing clinical perspectives and clarifying patient values related to the trade-offs of LCS.22 For example, the VA National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention developed a LCS decision aid to be used for SDM for LCS.

Whole health. The conversation shifts from “What is the matter with you?” to “What matters to you?” starting with the patient’s goals and priorities rather than disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.2 Several whole health tools exist, including the Personal Health Inventory, used to identify what matters most to patients and understand their current well-being and self-care.23 Using the inventory, the patient and their health care team develop the patient’s personal health plan.24 Additionally, whole health trains HCPs to reflect on their own attitudes and biases when providing clinical care.

Shared decision-making/whole health integration. The LCS conversation can build on other whole health-related conversations with a HCP or other team members. HCPs can reference the patient’s personal health plan for documentation of the patient’s preferences, values, and goals in the electronic medical record. During this process, HCPs can give space for patients to discuss factors in their life and experiences that impact their perspective and decision-making. For example, patient concerns could be explored here, including fear of a cancer diagnosis, stigma around smoking, and fears around the screening and/or treatment process. HCPs may ask, “What matters most to you when making this decision?” Finally, by sharing clinical information, HCPs will focus on patient values to help overcome their own biases toward a desire for LCS. HCPs, similar to the rest of the US public, tend to hold highly favorable attitudes toward cancer screening as well as misconceptions about the magnitude of benefits from screening.13

STEP 3. DELIBERATE AND DECIDE TOGETHER

Shared decision-making. Decision-making is almost always considered the last SDM step.4 In the final step, the patient and HCP discuss the options (ie, to screen or not to screen) considering the patient’s values and preferences, and patients decide with their HCP whether they will undergo LCS. Patients may decide they need more time to think about these options. As part of deliberation, HCPs assess what other information patients may need to arrive at a decision. Family members, friends, or peers may be included in making the final decision.

Whole health. In Whole health, decisions also may include the entire health care team and other individuals important to the patient (eg, family, friends). Integration across different health care settings is also considered a key whole health element. Finally, whole health focuses on long-term relationships with patients; thus, the LCS SDM process is situated within longer term relationship building and patient empowerment, both of which will facilitate partnering with the patient in future conversations about other decisions.

Shared decision-making/whole health integration. Both SDM and whole health emphasize partnership with the patient in making a final decision. There is also focus on decision-making as an ongoing process. Deciding whether LCS is the best choice might include naming and addressing emotions, voicing questions not raised, and exploring whether screening fits the patient’s goals, values, and life context. HCPs may give guidance, but patients retain the authority to make decisions. The goal is to empower patients to know that the only right decision is the one right for them and they will be supported.

Limitations

This article describes a VA practice program and was not a formal research study. Further work is needed to evaluate the presented strategies. Additionally, we did not conduct a systematic literature review and thus elements of SDM and whole health may not be exhaustive.

CONCLUSIONS

This article describes the alignment of 2 distinct VA initiatives, whole health and SDM for LCS. The goal was to reduce known barriers to SDM, such as competing demands, limited time, and lack of familiarity with and training in SDM.11-13 These concepts are well aligned. This integrated model is the first step in informing the development of a HCP training program and materials as part of a multilevel strategy that our team is using to implement SDM for LCS in VISN 1.16 The final training and materials resulting from this work were delivered to LCSCs in 3 ways: (1) a series of 3 interactive group training sessions, including didactic elements, role play, and time for open discussion; (2) 1-on-1 academic detailing; and (3) educational handouts. In academic detailing, a member of the research team trained in academic detailing met virtually with each nurse coordinator, identified that individual’s barriers to SDM, and used the training materials to highlight messages to overcome those barriers; follow-up calls provided a forum for discussing progress and overcoming additional challenges. Although this article focused specifically on whole health and SDM, the conceptual alignment process strategy can be applied to other implementations of multiple initiatives.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. The National Academies Press; 2001. doi:10.17226/10027

- Bokhour BG, Haun JN, Hyde J, Charns M, Kligler B. Transforming the Veterans Affairs to a whole health system of care: time for action and research. Med Care. 2020;58:295- 300. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001316

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Rollnick S. Dual equipoise shared decision making: definitions for decision and behaviour support interventions. Implement Sci. 2009;4:75. doi:7510.1186/1748-5908-4-75

- Bomhof-Roordink H, Gärtner FR, Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH. Key components of shared decision making models: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e031763. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031763

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician- patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651-661. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8

- Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:330- 338. doi:10.7326/m13-2771

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT). February 10, 2022. Accessed February 7, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncacal-decision-memo.aspx?proposed=N&ncaid=304

- Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395-409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

- Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153:1004-1015. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.10.013

- Nishi SPE, Lowenstein LM, Mendoza TR, et al. Shared decision-making for lung cancer screening: how well are we “sharing”? Chest. 2021;160:330-340. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.041

- Wiener RS, Koppelman E, Bolton R, et al. Patient and clinician perspectives on shared decision-making in early adopting lung cancer screening programs: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1035-1042. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4350-9

- Melzer AC, Golden SE, Ono SS, Datta S, Triplette M, Slatore CG. “We just never have enough time”: clinician views of lung cancer screening processes and implementation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-262OC

- Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Fowler FJ Jr, Welch HG. Enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States. JAMA. 2004;291:71-78. doi:10.1001/jama.291.1.71

- Lown BA, Rosen J, Marttila J. An agenda for improving compassionate care: a survey shows about half of patients say such care is missing. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:1772-1778. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0539

- Scholl I, LaRussa A, Hahlweg P, Kobrin S, Elwyn G. Organizational- and system-level characteristics that influence implementation of shared decision-making and strategies to address them - a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2018;13:40. doi:10.1186/s13012-018-0731-z

- Khanna A, Fix GM, Anderson E, et al. Towards a framework for patient-centred care coordination: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e066808. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-066808

- Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ. 2017;359:j4891. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4891

- Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:301-312. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010

- Whole Health. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth/

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The SHARE approach. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/professional-training/shared-decision/index.html

- Abadi MH, Barker AM, Rao SR, Orner M, Rychener D, Bokhour BG. Examining the impact of a peer-led group program for veteran engagement and well-being. J Altern Complement Med. 2021;27:S37-S44. doi:10.1089/acm.2020.0124

- Stacey D, Lewis KB, Smith M, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;1:CD001431. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub6

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation. Personal health inventory. Revised April 2019. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth/docs/10-773_PHI_July2019_508.pdf

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Build your personal health plan. Updated July 24, 2024. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth/phi.asp

The landmark Crossing the Quality Chasm report from the National Academy of Medicine identified patient- centered care as essential to health care quality. The report defines patientcentered care as “respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values.”1 Many health care systems, including the Veterans Health Administration, are transforming to a patient-centered model of care.2 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Whole Health System of Care initiative is a system-wide, cultural transformation. Within whole health, what matters most to the patient—including their preferences, needs, and values—is foundational to health care and meant to be essential in every clinical encounter. Whole health implementation includes a progressive rollout with health care practitioner (HCP) trainings across the VA.2

Shared decision-making (SDM) is a different but aligned patient-centered care concept. SDM is a process through which a decision or care plan, based on patients’ preferences, needs, and values, is made or developed.3-5 SDM is ideal in situations with equipoise (decisions with equivalent choices), individualized risks, and/or greater uncertainty of the net benefit, such as with lung cancer screening (LCS).3 SDM for LCS is required by the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and has been adopted by many US health care systems, including the VA.6,7 Early detection of lung cancer can reduce death by 20% at the population level.8 However, at the patient level there is wide variation in the risk of developing lung cancer and a range of potential harms.8 LCS follow-up procedures may be more invasive than with other cancer screenings. Thus, there is concern about the risk of false-positive results leading to unnecessary care or complications.8 Given this balance between benefit and harm and the differing patient value on the trade-offs of LCS, an individualized, patient-centered approach is essential when deciding whether LCS is the right choice for a specific patient.

Despite the importance of LCS SDM, observational studies have shown poor implementation in clinical encounters.9,10 HCP barriers include competing demands, limited time, lack of familiarity with and training in SDM, and beliefs biasing screening over no screening.11-13 Additionally, HCPs may assume that patients want them to make the decision. However, research has shown that patients actually want to be more involved in their health care decisions.14 One suggested strategy to overcome these barriers is aligning SDM for LCS within an organization’s broader patient-centered initiatives.15

This project sought to align the need for SDM for LCS and the broader VA whole health initiative as part of a multilevel strategy to implement SDM for LCS across Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 1.16

This article addresses HCP-level barriers. HCPs targeted are those typically involved in LCS. The VA utilizes LCS coordinators (LCSCs) in both centralized or consult models (in which LCSCs are involved in all aspects of screening) and hybrid models (in which primary care practitioners and LCSCs are both engaged in LCS tasks). The goal of this program was to generate areas of conceptual alignment between SDM and whole health as a first step in integrating these VA initiatives. This work was conducted as a foundation for an SDM for lung cancer HCP training and consultation initiative.

ALIGNMENT PROCESS

We reviewed relevant literature and resources for SDM and whole health. In reviewing the SDM literature, we included a sample of the most widely cited literature on the topic, and focused primarily on the systematic review by Bomhof-Roordink et al.4,5,17,18 This review provided a synthesis of SDM elements across SDM models and identified 53 different elements clustered into 24 components.4 The most common components were present in at least half of all SDM published models, including: make the decision, patient preferences, tailor information, deliberate, create choice awareness, and learn about the patient. Bomhof-Roordink et al provided the guiding framework for this conceptualization of SDM because that study included the available recent published SDM models.4

Second, published literature on VA whole health along with supplemental promotional and training materials were reviewed. The whole health materials included 2 sets of training slides developed for VA HCPs (available to VA employees): Implementing Whole Health in Clinical Care, which is focused on HCPs’ work with patients, and Whole Health for You and Me, which is about HCPs’ personal well-being.19 We also reviewed a publication describing the history of whole health and patient-facing online whole health tools.2,19

Each document was reviewed for key elements related to SDM, patient-centered care, and whole health. Using the 53 elements identified by Bomhof-Roordink et al, we reviewed and compared each element to the whole health materials to create the integrated model of SDM and whole health. We iteratively discussed and organized the elements until we reached consensus.

SDM and Whole Health Alignment

We created an integrated model of SDM for LCS within the context of the VA whole health initiative. This integrated model is directed at HCPs who would likely engage patients in discussions of LCS, including primary care practitioners and nurse coordinators. The model includes 3 steps for HCPs to follow that align SDM within whole health: (1) frame the conversation and partner with the patient; (2) share clinical perspective and elicit patient values; and (3) deliberate and decide together. For each step, the SDM elements, whole health elements, and integration of SDM and whole health are provided. Table 1 provides an overview of the similarities and differences between SDM and whole health. Example phrases that merge SDM and whole health for HCPs to use in patient conversations about LCS are included in Table 2.

STEP 1. FRAME THE CONVERSATION AND PARTNER WITH THE PATIENT

Shared decision-making. Traditional SDM literature includes an initial step of letting patients know that there is a choice to be made between ≥ 2 clinical options.4 Ancillary elements of this first step include asking patients their preferences about the degree to which they want to be involved in SDM and about how they like to receive information (eg, verbal, written, video). These steps open the SDM conversation and ensure the patient and HCP are on the same page before moving forward. For example, the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality SHARE model’s first step is for HCPs to communicate that choices exist and to invite the patient to be involved in decisions.20 Similarly, Elwyn’s 3-step SDM model begins with establishing that a choice exists and inviting patient input on making that choice.17

Whole health. Patients are encouraged to play an active role in their health care. Through whole health programs such as Taking Charge of My Life and Health, patients explore their values and set self-care goals.21 HCP whole health trainings teach and reinforce communication skills, including SDM, listening skills, and motivational interviewing.19

Shared decision-making/whole health integration. SDM and whole health both prioritize respect, compassion, and patients’ expertise. They focus on the patient-HCP relationship with an emphasis on fostering egalitarian interactions. HCPs frame the SDM conversation and partner with the patient so they know what to expect and who will be involved. This conversation is framed from the outset as a collaborative discussion. HCPs empower the patient to play an active role in decision-making and help them understand why their engagement is critical.

STEP 2. SHARE CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE AND ELICIT PATIENT VALUES

Shared decision-making. HCPs share clinical perspective on LCS tailored to individual patients while explicitly inviting the patient to share their preferences and values when thinking about whether to undergo LCS. HCPs give a balanced description of LCS, including the benefits and harms, tailored to the patient’s unique information needs and questions. Sharing clinical perspective also includes describing treatment options, the most common element across SDM models.4 Decision aids, which provide unbiased information and include a values clarification exercise, may be helpful in sharing clinical perspectives and clarifying patient values related to the trade-offs of LCS.22 For example, the VA National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention developed a LCS decision aid to be used for SDM for LCS.

Whole health. The conversation shifts from “What is the matter with you?” to “What matters to you?” starting with the patient’s goals and priorities rather than disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.2 Several whole health tools exist, including the Personal Health Inventory, used to identify what matters most to patients and understand their current well-being and self-care.23 Using the inventory, the patient and their health care team develop the patient’s personal health plan.24 Additionally, whole health trains HCPs to reflect on their own attitudes and biases when providing clinical care.

Shared decision-making/whole health integration. The LCS conversation can build on other whole health-related conversations with a HCP or other team members. HCPs can reference the patient’s personal health plan for documentation of the patient’s preferences, values, and goals in the electronic medical record. During this process, HCPs can give space for patients to discuss factors in their life and experiences that impact their perspective and decision-making. For example, patient concerns could be explored here, including fear of a cancer diagnosis, stigma around smoking, and fears around the screening and/or treatment process. HCPs may ask, “What matters most to you when making this decision?” Finally, by sharing clinical information, HCPs will focus on patient values to help overcome their own biases toward a desire for LCS. HCPs, similar to the rest of the US public, tend to hold highly favorable attitudes toward cancer screening as well as misconceptions about the magnitude of benefits from screening.13

STEP 3. DELIBERATE AND DECIDE TOGETHER

Shared decision-making. Decision-making is almost always considered the last SDM step.4 In the final step, the patient and HCP discuss the options (ie, to screen or not to screen) considering the patient’s values and preferences, and patients decide with their HCP whether they will undergo LCS. Patients may decide they need more time to think about these options. As part of deliberation, HCPs assess what other information patients may need to arrive at a decision. Family members, friends, or peers may be included in making the final decision.

Whole health. In Whole health, decisions also may include the entire health care team and other individuals important to the patient (eg, family, friends). Integration across different health care settings is also considered a key whole health element. Finally, whole health focuses on long-term relationships with patients; thus, the LCS SDM process is situated within longer term relationship building and patient empowerment, both of which will facilitate partnering with the patient in future conversations about other decisions.

Shared decision-making/whole health integration. Both SDM and whole health emphasize partnership with the patient in making a final decision. There is also focus on decision-making as an ongoing process. Deciding whether LCS is the best choice might include naming and addressing emotions, voicing questions not raised, and exploring whether screening fits the patient’s goals, values, and life context. HCPs may give guidance, but patients retain the authority to make decisions. The goal is to empower patients to know that the only right decision is the one right for them and they will be supported.

Limitations

This article describes a VA practice program and was not a formal research study. Further work is needed to evaluate the presented strategies. Additionally, we did not conduct a systematic literature review and thus elements of SDM and whole health may not be exhaustive.

CONCLUSIONS

This article describes the alignment of 2 distinct VA initiatives, whole health and SDM for LCS. The goal was to reduce known barriers to SDM, such as competing demands, limited time, and lack of familiarity with and training in SDM.11-13 These concepts are well aligned. This integrated model is the first step in informing the development of a HCP training program and materials as part of a multilevel strategy that our team is using to implement SDM for LCS in VISN 1.16 The final training and materials resulting from this work were delivered to LCSCs in 3 ways: (1) a series of 3 interactive group training sessions, including didactic elements, role play, and time for open discussion; (2) 1-on-1 academic detailing; and (3) educational handouts. In academic detailing, a member of the research team trained in academic detailing met virtually with each nurse coordinator, identified that individual’s barriers to SDM, and used the training materials to highlight messages to overcome those barriers; follow-up calls provided a forum for discussing progress and overcoming additional challenges. Although this article focused specifically on whole health and SDM, the conceptual alignment process strategy can be applied to other implementations of multiple initiatives.

The landmark Crossing the Quality Chasm report from the National Academy of Medicine identified patient- centered care as essential to health care quality. The report defines patientcentered care as “respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values.”1 Many health care systems, including the Veterans Health Administration, are transforming to a patient-centered model of care.2 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Whole Health System of Care initiative is a system-wide, cultural transformation. Within whole health, what matters most to the patient—including their preferences, needs, and values—is foundational to health care and meant to be essential in every clinical encounter. Whole health implementation includes a progressive rollout with health care practitioner (HCP) trainings across the VA.2

Shared decision-making (SDM) is a different but aligned patient-centered care concept. SDM is a process through which a decision or care plan, based on patients’ preferences, needs, and values, is made or developed.3-5 SDM is ideal in situations with equipoise (decisions with equivalent choices), individualized risks, and/or greater uncertainty of the net benefit, such as with lung cancer screening (LCS).3 SDM for LCS is required by the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and has been adopted by many US health care systems, including the VA.6,7 Early detection of lung cancer can reduce death by 20% at the population level.8 However, at the patient level there is wide variation in the risk of developing lung cancer and a range of potential harms.8 LCS follow-up procedures may be more invasive than with other cancer screenings. Thus, there is concern about the risk of false-positive results leading to unnecessary care or complications.8 Given this balance between benefit and harm and the differing patient value on the trade-offs of LCS, an individualized, patient-centered approach is essential when deciding whether LCS is the right choice for a specific patient.

Despite the importance of LCS SDM, observational studies have shown poor implementation in clinical encounters.9,10 HCP barriers include competing demands, limited time, lack of familiarity with and training in SDM, and beliefs biasing screening over no screening.11-13 Additionally, HCPs may assume that patients want them to make the decision. However, research has shown that patients actually want to be more involved in their health care decisions.14 One suggested strategy to overcome these barriers is aligning SDM for LCS within an organization’s broader patient-centered initiatives.15

This project sought to align the need for SDM for LCS and the broader VA whole health initiative as part of a multilevel strategy to implement SDM for LCS across Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 1.16

This article addresses HCP-level barriers. HCPs targeted are those typically involved in LCS. The VA utilizes LCS coordinators (LCSCs) in both centralized or consult models (in which LCSCs are involved in all aspects of screening) and hybrid models (in which primary care practitioners and LCSCs are both engaged in LCS tasks). The goal of this program was to generate areas of conceptual alignment between SDM and whole health as a first step in integrating these VA initiatives. This work was conducted as a foundation for an SDM for lung cancer HCP training and consultation initiative.

ALIGNMENT PROCESS