User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

Outcomes-based measurement of TAVR program quality goes live

The long-sought goal of measuring the quality of U.S. transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) programs by patient outcomes rather than by the surrogate measure of case volume is about to be realized.

Starting more or less immediately, the U.S. national register for all TAVR cases that’s mandated by Food and Drug Administration labeling of these devices and run through a collaboration of the American College of Cardiology and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons will start applying a newly developed and validated five-item metric for measuring 30-day patient outcomes and designed to gauge the quality of TAVR programs.

At first, the only recipients of the data will be the programs themselves, but starting in about a year, by sometime in 2021, the STS/ACC TVT (transcatheter valve therapy) Registry will start to make its star-based rating of TAVR programs available to the public, Nimesh D. Desai, MD, said on March 29 at the joint scientific sessions of the ACC and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic. These societies already make star-based ratings of U.S. programs available to the public for several other types of cardiac interventions, including coronary artery bypass surgery and MI management.

The new, composite metric based on 30-day outcome data “is appropriate for high-stakes applications such as public reporting,” said Dr. Desai, a thoracic surgeon and director of thoracic aortic surgery research at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “We’re confident this model can be used for public reporting. It’s undergone extensive testing of its validity.” The steering committee of the STS/ACC TVT Registry commissioned development of the metric, and it’s now “considered approved,” and ready for use, he explained.

To create the new metric, Dr. Desai and his associates used data from 52,561 patients who underwent transfemoral TAVR during 2015-2017 at any of 301 U.S. sites. These data came from a total pool of more than 114,000 patients at 556 sites, but data from many sites weren’t usable because they were not adequately complete. The researchers then identified the top four measures taken during the 30 days following intervention (hospitalization included) that best correlated with 1-year survival and patients’ quality-of-life scores on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: stroke; major, life-threatening, or disabling bleed; acute kidney injury (stage III); and moderate or severe paravalvular leak. These outcomes “matter most to patients,” Dr. Desai said.

They used these four outcomes plus 30-day mortality to calculate the programs’ ratings. Among the 52,561 patients, 14% had at least one of these adverse outcomes. The researchers then used a logistic regression model that adjusted for 46 measured variables to calculate how each program performed relative to the average performance of all the programs. Programs with outcomes that fell within the 95% confidence intervals of average performance were rated as performing as expected; those outside rated as performing either better or worse than expected. The results showed 34 centers (11%) had worse than expected outcomes and 25 (8%) had better than expected outcomes, Dr. Desai said.

“This is a major step forward in measuring TAVR quality,” commented Michael Mack, MD, a cardiac surgeon with Baylor Scott & White Health in Dallas who has been very active in studying TAVR. “Until now, we used volume as a surrogate for quality, but the precision was not great. This is an extremely welcome metric.” The next step is to eventually use 1-year follow-up data instead of 30-day outcomes, he added.

“With the rapid expansion of TAVR over the past 6-8 years, we’re now at the point to start to do this. It’s an ethical obligation This will be one of the most high-fidelity, valid models for public reporting” of clinical outcomes,” said Joseph Cleveland, MD, a professor of surgery at the University of Colorado at Denver in Aurora. “It’s reassuring that about 90% of the program performed as expected or better than expected,” he added.

“Transparency and outcomes should drive how TAVR is delivered,” commented Ashish Pershad, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Banner-University Medicine Heart Institute in Phoenix who estimated that he performs about 150 TAVR procedures annually. “This is a step forward. I’ve been waiting for this for a long time. Until now, volume has been used as a surrogate outcome, but we know it’s not accurate. I’m confident that this model is a good starting point.” But Dr. Pershad also had concern that this new approach “can lend itself to some degree of gaming,” like a bleeding event getting classified as minor when it was really major, or outlier patients getting dropped from reports.

The temptation to cut corners may be higher for TAVR than it’s been for the cardiac-disease metrics that already get publicly reported, like bypass surgery and myocardial infarction management, because of TAVR’s higher cost and higher profile, Dr. Pershad said. Existing measures “have not been as linked to financial disincentive as TAVR might be” because TAVR reimbursements can run as high as $50,000 per case. “The stakes with TAVR are higher,” he said.

Ultimately, the reliable examination of TAVR outcomes that this new metric allows may lead to a shake-up of TAVR programs, Dr. Pershad predicted. “This is clearly a step toward closing down some programs that [consistently] underperform.”

The STS/ACC TVT Registry receives no commercial funding. Dr. Desai has been a consultant to, speaker on behalf of, and received research funding from Gore, and he has also spoken on behalf of Cook, Medtronic, and Terumo Aortic. Dr. Cleveland, Dr. Mack, and Dr. Pershad had no disclosures.

The long-sought goal of measuring the quality of U.S. transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) programs by patient outcomes rather than by the surrogate measure of case volume is about to be realized.

Starting more or less immediately, the U.S. national register for all TAVR cases that’s mandated by Food and Drug Administration labeling of these devices and run through a collaboration of the American College of Cardiology and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons will start applying a newly developed and validated five-item metric for measuring 30-day patient outcomes and designed to gauge the quality of TAVR programs.

At first, the only recipients of the data will be the programs themselves, but starting in about a year, by sometime in 2021, the STS/ACC TVT (transcatheter valve therapy) Registry will start to make its star-based rating of TAVR programs available to the public, Nimesh D. Desai, MD, said on March 29 at the joint scientific sessions of the ACC and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic. These societies already make star-based ratings of U.S. programs available to the public for several other types of cardiac interventions, including coronary artery bypass surgery and MI management.

The new, composite metric based on 30-day outcome data “is appropriate for high-stakes applications such as public reporting,” said Dr. Desai, a thoracic surgeon and director of thoracic aortic surgery research at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “We’re confident this model can be used for public reporting. It’s undergone extensive testing of its validity.” The steering committee of the STS/ACC TVT Registry commissioned development of the metric, and it’s now “considered approved,” and ready for use, he explained.

To create the new metric, Dr. Desai and his associates used data from 52,561 patients who underwent transfemoral TAVR during 2015-2017 at any of 301 U.S. sites. These data came from a total pool of more than 114,000 patients at 556 sites, but data from many sites weren’t usable because they were not adequately complete. The researchers then identified the top four measures taken during the 30 days following intervention (hospitalization included) that best correlated with 1-year survival and patients’ quality-of-life scores on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: stroke; major, life-threatening, or disabling bleed; acute kidney injury (stage III); and moderate or severe paravalvular leak. These outcomes “matter most to patients,” Dr. Desai said.

They used these four outcomes plus 30-day mortality to calculate the programs’ ratings. Among the 52,561 patients, 14% had at least one of these adverse outcomes. The researchers then used a logistic regression model that adjusted for 46 measured variables to calculate how each program performed relative to the average performance of all the programs. Programs with outcomes that fell within the 95% confidence intervals of average performance were rated as performing as expected; those outside rated as performing either better or worse than expected. The results showed 34 centers (11%) had worse than expected outcomes and 25 (8%) had better than expected outcomes, Dr. Desai said.

“This is a major step forward in measuring TAVR quality,” commented Michael Mack, MD, a cardiac surgeon with Baylor Scott & White Health in Dallas who has been very active in studying TAVR. “Until now, we used volume as a surrogate for quality, but the precision was not great. This is an extremely welcome metric.” The next step is to eventually use 1-year follow-up data instead of 30-day outcomes, he added.

“With the rapid expansion of TAVR over the past 6-8 years, we’re now at the point to start to do this. It’s an ethical obligation This will be one of the most high-fidelity, valid models for public reporting” of clinical outcomes,” said Joseph Cleveland, MD, a professor of surgery at the University of Colorado at Denver in Aurora. “It’s reassuring that about 90% of the program performed as expected or better than expected,” he added.

“Transparency and outcomes should drive how TAVR is delivered,” commented Ashish Pershad, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Banner-University Medicine Heart Institute in Phoenix who estimated that he performs about 150 TAVR procedures annually. “This is a step forward. I’ve been waiting for this for a long time. Until now, volume has been used as a surrogate outcome, but we know it’s not accurate. I’m confident that this model is a good starting point.” But Dr. Pershad also had concern that this new approach “can lend itself to some degree of gaming,” like a bleeding event getting classified as minor when it was really major, or outlier patients getting dropped from reports.

The temptation to cut corners may be higher for TAVR than it’s been for the cardiac-disease metrics that already get publicly reported, like bypass surgery and myocardial infarction management, because of TAVR’s higher cost and higher profile, Dr. Pershad said. Existing measures “have not been as linked to financial disincentive as TAVR might be” because TAVR reimbursements can run as high as $50,000 per case. “The stakes with TAVR are higher,” he said.

Ultimately, the reliable examination of TAVR outcomes that this new metric allows may lead to a shake-up of TAVR programs, Dr. Pershad predicted. “This is clearly a step toward closing down some programs that [consistently] underperform.”

The STS/ACC TVT Registry receives no commercial funding. Dr. Desai has been a consultant to, speaker on behalf of, and received research funding from Gore, and he has also spoken on behalf of Cook, Medtronic, and Terumo Aortic. Dr. Cleveland, Dr. Mack, and Dr. Pershad had no disclosures.

The long-sought goal of measuring the quality of U.S. transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) programs by patient outcomes rather than by the surrogate measure of case volume is about to be realized.

Starting more or less immediately, the U.S. national register for all TAVR cases that’s mandated by Food and Drug Administration labeling of these devices and run through a collaboration of the American College of Cardiology and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons will start applying a newly developed and validated five-item metric for measuring 30-day patient outcomes and designed to gauge the quality of TAVR programs.

At first, the only recipients of the data will be the programs themselves, but starting in about a year, by sometime in 2021, the STS/ACC TVT (transcatheter valve therapy) Registry will start to make its star-based rating of TAVR programs available to the public, Nimesh D. Desai, MD, said on March 29 at the joint scientific sessions of the ACC and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic. These societies already make star-based ratings of U.S. programs available to the public for several other types of cardiac interventions, including coronary artery bypass surgery and MI management.

The new, composite metric based on 30-day outcome data “is appropriate for high-stakes applications such as public reporting,” said Dr. Desai, a thoracic surgeon and director of thoracic aortic surgery research at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “We’re confident this model can be used for public reporting. It’s undergone extensive testing of its validity.” The steering committee of the STS/ACC TVT Registry commissioned development of the metric, and it’s now “considered approved,” and ready for use, he explained.

To create the new metric, Dr. Desai and his associates used data from 52,561 patients who underwent transfemoral TAVR during 2015-2017 at any of 301 U.S. sites. These data came from a total pool of more than 114,000 patients at 556 sites, but data from many sites weren’t usable because they were not adequately complete. The researchers then identified the top four measures taken during the 30 days following intervention (hospitalization included) that best correlated with 1-year survival and patients’ quality-of-life scores on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: stroke; major, life-threatening, or disabling bleed; acute kidney injury (stage III); and moderate or severe paravalvular leak. These outcomes “matter most to patients,” Dr. Desai said.

They used these four outcomes plus 30-day mortality to calculate the programs’ ratings. Among the 52,561 patients, 14% had at least one of these adverse outcomes. The researchers then used a logistic regression model that adjusted for 46 measured variables to calculate how each program performed relative to the average performance of all the programs. Programs with outcomes that fell within the 95% confidence intervals of average performance were rated as performing as expected; those outside rated as performing either better or worse than expected. The results showed 34 centers (11%) had worse than expected outcomes and 25 (8%) had better than expected outcomes, Dr. Desai said.

“This is a major step forward in measuring TAVR quality,” commented Michael Mack, MD, a cardiac surgeon with Baylor Scott & White Health in Dallas who has been very active in studying TAVR. “Until now, we used volume as a surrogate for quality, but the precision was not great. This is an extremely welcome metric.” The next step is to eventually use 1-year follow-up data instead of 30-day outcomes, he added.

“With the rapid expansion of TAVR over the past 6-8 years, we’re now at the point to start to do this. It’s an ethical obligation This will be one of the most high-fidelity, valid models for public reporting” of clinical outcomes,” said Joseph Cleveland, MD, a professor of surgery at the University of Colorado at Denver in Aurora. “It’s reassuring that about 90% of the program performed as expected or better than expected,” he added.

“Transparency and outcomes should drive how TAVR is delivered,” commented Ashish Pershad, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Banner-University Medicine Heart Institute in Phoenix who estimated that he performs about 150 TAVR procedures annually. “This is a step forward. I’ve been waiting for this for a long time. Until now, volume has been used as a surrogate outcome, but we know it’s not accurate. I’m confident that this model is a good starting point.” But Dr. Pershad also had concern that this new approach “can lend itself to some degree of gaming,” like a bleeding event getting classified as minor when it was really major, or outlier patients getting dropped from reports.

The temptation to cut corners may be higher for TAVR than it’s been for the cardiac-disease metrics that already get publicly reported, like bypass surgery and myocardial infarction management, because of TAVR’s higher cost and higher profile, Dr. Pershad said. Existing measures “have not been as linked to financial disincentive as TAVR might be” because TAVR reimbursements can run as high as $50,000 per case. “The stakes with TAVR are higher,” he said.

Ultimately, the reliable examination of TAVR outcomes that this new metric allows may lead to a shake-up of TAVR programs, Dr. Pershad predicted. “This is clearly a step toward closing down some programs that [consistently] underperform.”

The STS/ACC TVT Registry receives no commercial funding. Dr. Desai has been a consultant to, speaker on behalf of, and received research funding from Gore, and he has also spoken on behalf of Cook, Medtronic, and Terumo Aortic. Dr. Cleveland, Dr. Mack, and Dr. Pershad had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ACC 20

Larger absolute rivaroxaban benefit in diabetes: COMPASS

In the COMPASS trial of patients with stable coronary or peripheral artery disease (PAD), the combination of aspirin plus rivaroxaban, 2.5 mg twice daily, provided a larger absolute benefit on cardiovascular endpoints — including a threefold greater reduction in all-cause mortality — in patients with diabetes compared with the overall population.

The results of the diabetes subset of the COMPASS trial were presented by Deepak Bhatt, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart & Vascular Center, Boston, Massachusetts, on March 28 at the “virtual” American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). They were also simultaneously published online in Circulation.

“Use of dual pathway inhibition with low-dose rivaroxaban plus aspirin is particularly attractive in high-risk patients such as those with diabetes,” Bhatt concluded.

The COMPASS trial was first reported in 2017 and showed a new low dose of rivaroxaban (2.5-mg twice-daily; Xarelto, Bayer/Janssen Pharmaceuticals) plus aspirin, 100 mg once daily, was associated with a reduction in ischemic events and mortality and a superior net clinical benefit, balancing ischemic benefit with severe bleeding, compared with aspirin alone for secondary prevention in patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease.

But clinicians have been slow to prescribe rivaroxaban in this new and very large population.

“It’s been more than 2 years now since main COMPASS results, and there isn’t a sense that this therapy has really caught on,” chair of the current ACC session at which the diabetes subgroup results were presented, Hadley Wilson, MD, Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute, Charlotte, North Carolina, commented:

He asked Bhatt whether the diabetes subgroup may be “the tipping point that will make people aware of rivaroxaban and then that may trickle down to other patients.”

Bhatt said that he hoped that would be the case. “We as a steering committee of this trial could say the results were positive so rivaroxaban should now be used in everyone with stable coronary or peripheral arterial disease, but that is impractical and as you out point out it hasn’t happened,” he replied.

“In PAD/vascular medicine we have embraced this new therapy. In the broader cardiology world there are a lot of patients with stable coronary arterial disease at high ischemic risk who could take rivaroxaban, but its use is bound to be limited by it being a branded drug and the fact that there is a bleeding risk,” Bhatt explained.

“I think we need to identify patients with the highest ischemic risk and focus drugs such as these with a financial cost and a bleeding risk on those who most likely will derive the greatest absolute reduction in risk,” he said. “The PAD subgroup is one group where this is the case, and now we have shown the diabetes subgroup is another. And there is no incremental bleeding risk in this group over the whole population, so they get a much greater benefit without a greater risk. I hope this helps get rivaroxaban at the new lower dose used much more often.”

A total of 18,278 patients were randomly assigned to the combination of rivaroxaban and aspirin or aspirin alone in the COMPASS trial. Of these, 6922 had diabetes mellitus at baseline and 11,356 did not have diabetes.

Results from the current analysis show a consistent and similar relative risk reduction for benefit of rivaroxaban plus aspirin vs placebo plus aspirin in patients both with and without diabetes for the primary efficacy endpoint, a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke, with a hazard ratio of 0.74 for patients with diabetes and 0.77 for those without diabetes, the researchers report.

Because of the higher baseline risk in the diabetes subgroup, these patients had numerically larger absolute risk reductions with rivaroxaban than those without diabetes for the primary efficacy endpoint at 3 years (2.3% vs 1.4%) and for all-cause mortality (1.9% vs 0.6%).

These results translate into a number needed to treat (NNT) with rivaroxaban for 3 years to prevent one CV death, MI, or stroke of 44 for the diabetes group vs 73 for the nondiabetes group; the NNT to prevent one all-cause death was 54 for the diabetes group vs 167 for the nondiabetes group, the authors write.

Because the bleeding hazards were similar among patients with and without diabetes, the absolute net clinical benefit (MI, stroke, cardiovascular death, or bleeding leading to death or symptomatic bleeding into a critical organ) for rivaroxaban was “particularly favorable” in the diabetes group (2.7% fewer events in the diabetes group vs 1.0% fewer events in the nondiabetes group), they add.

Panelist at the ACC Featured Clinical Research session at which these results were presented, Jennifer Robinson, MD, University of Iowa College of Public Health, Iowa City, asked Bhatt how clinicians were supposed to decide which of the many new agents now becoming available for patients with stable coronary artery disease to prescribe first.

“We often forget about rivaroxaban when we’re thinking about what to add next for our secondary prevention patients,” she said. “You also led the REDUCE-IT trial showing benefit of icosapent ethyl, icosapent ethyl icosapent ethyl icosapent ethyl and there is also ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors. For your patients with coronary disease who are already on a high dose statin which one of these would you add next?”

“That is what physicians need to ponder all the time,” Bhatt replied. “And when a patient has several risk factors that are not well controlled, I guess it’s all important. I go through a checklist with my patients and try and figure what they’re not on that could further reduce their risk.”

“In the COMPASS trial there was an overall positive result with rivaroxaban in the whole population. And now we have shown that patients with diabetes had an even greater absolute risk reduction. That pattern has also been seen with other classes of agents including the statins, PCSK9 inhibitors, and icosapent ethyl,” Bhatt noted.

“In patients with diabetes, I will usually target whatever is standing out most at that time. If their glycemic control is completely out of whack, then that is what I would focus on first, and these days often with a SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 agonist. If the LDL was out of control, I would add ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor. If the triglycerides were high, I would add icosapent ethyl. If multiple things were out of control, I would usually focus on the number most out of kilter first and try not to forget about everything else.”

But Bhatt noted that the challenge with rivaroxaban is that there is no test of thrombosis risk that would prompt the physician to take action. “Basically, the doctor just has to remember to do it. In that regard I would consider whether patients are at low bleeding risk and are they still at high ischemic risk despite controlling other risk factors and, if so, then I would add this low dose of rivaroxaban.”

Another panel member, Sekar Kathiresan, MD, asked Bhatt whether he recommended using available scores to assess the bleeding/thrombosis risk/benefits of adding an antithrombotic.

Bhatt replied: “That’s a terrific question. I guess the right answer is that we should be doing that, but in reality I have to concede that I don’t use these scores. They have shown appropriate C statistics in populations, but they are not fantastic in individual patients.”

“I have to confess that I use the eyeball test. There is nothing as good at predicting future bleeding as past bleeding. So if a patient has had bleeding problems on aspirin alone I wouldn’t add rivaroxaban. But if a patient hasn’t bled before, especially if they had some experience of dual antiplatelet therapy, then they would be good candidates for a low vascular dose of rivaroxaban,” he said.

“It is not as easy as with other drugs as there is always a bleeding trade-off with an antithrombotic. There is no such thing as a free lunch. So patients need careful assessment when considering prescribing rivaroxaban and regular reassessment over time to check if they have had any bleeding,” he added.

The COMPASS study was funded by Bayer. Bhatt reports honoraria from Bayer via the Population Health Research Institute for his role on the COMPASS trial and other research funding from Bayer to the Brigham & Women’s Hospital.

American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). Abstract 20-LB-20544-ACC. Presented March 28, 2020.

Circulation. Published online March 28, 2020. Full text.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the COMPASS trial of patients with stable coronary or peripheral artery disease (PAD), the combination of aspirin plus rivaroxaban, 2.5 mg twice daily, provided a larger absolute benefit on cardiovascular endpoints — including a threefold greater reduction in all-cause mortality — in patients with diabetes compared with the overall population.

The results of the diabetes subset of the COMPASS trial were presented by Deepak Bhatt, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart & Vascular Center, Boston, Massachusetts, on March 28 at the “virtual” American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). They were also simultaneously published online in Circulation.

“Use of dual pathway inhibition with low-dose rivaroxaban plus aspirin is particularly attractive in high-risk patients such as those with diabetes,” Bhatt concluded.

The COMPASS trial was first reported in 2017 and showed a new low dose of rivaroxaban (2.5-mg twice-daily; Xarelto, Bayer/Janssen Pharmaceuticals) plus aspirin, 100 mg once daily, was associated with a reduction in ischemic events and mortality and a superior net clinical benefit, balancing ischemic benefit with severe bleeding, compared with aspirin alone for secondary prevention in patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease.

But clinicians have been slow to prescribe rivaroxaban in this new and very large population.

“It’s been more than 2 years now since main COMPASS results, and there isn’t a sense that this therapy has really caught on,” chair of the current ACC session at which the diabetes subgroup results were presented, Hadley Wilson, MD, Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute, Charlotte, North Carolina, commented:

He asked Bhatt whether the diabetes subgroup may be “the tipping point that will make people aware of rivaroxaban and then that may trickle down to other patients.”

Bhatt said that he hoped that would be the case. “We as a steering committee of this trial could say the results were positive so rivaroxaban should now be used in everyone with stable coronary or peripheral arterial disease, but that is impractical and as you out point out it hasn’t happened,” he replied.

“In PAD/vascular medicine we have embraced this new therapy. In the broader cardiology world there are a lot of patients with stable coronary arterial disease at high ischemic risk who could take rivaroxaban, but its use is bound to be limited by it being a branded drug and the fact that there is a bleeding risk,” Bhatt explained.

“I think we need to identify patients with the highest ischemic risk and focus drugs such as these with a financial cost and a bleeding risk on those who most likely will derive the greatest absolute reduction in risk,” he said. “The PAD subgroup is one group where this is the case, and now we have shown the diabetes subgroup is another. And there is no incremental bleeding risk in this group over the whole population, so they get a much greater benefit without a greater risk. I hope this helps get rivaroxaban at the new lower dose used much more often.”

A total of 18,278 patients were randomly assigned to the combination of rivaroxaban and aspirin or aspirin alone in the COMPASS trial. Of these, 6922 had diabetes mellitus at baseline and 11,356 did not have diabetes.

Results from the current analysis show a consistent and similar relative risk reduction for benefit of rivaroxaban plus aspirin vs placebo plus aspirin in patients both with and without diabetes for the primary efficacy endpoint, a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke, with a hazard ratio of 0.74 for patients with diabetes and 0.77 for those without diabetes, the researchers report.

Because of the higher baseline risk in the diabetes subgroup, these patients had numerically larger absolute risk reductions with rivaroxaban than those without diabetes for the primary efficacy endpoint at 3 years (2.3% vs 1.4%) and for all-cause mortality (1.9% vs 0.6%).

These results translate into a number needed to treat (NNT) with rivaroxaban for 3 years to prevent one CV death, MI, or stroke of 44 for the diabetes group vs 73 for the nondiabetes group; the NNT to prevent one all-cause death was 54 for the diabetes group vs 167 for the nondiabetes group, the authors write.

Because the bleeding hazards were similar among patients with and without diabetes, the absolute net clinical benefit (MI, stroke, cardiovascular death, or bleeding leading to death or symptomatic bleeding into a critical organ) for rivaroxaban was “particularly favorable” in the diabetes group (2.7% fewer events in the diabetes group vs 1.0% fewer events in the nondiabetes group), they add.

Panelist at the ACC Featured Clinical Research session at which these results were presented, Jennifer Robinson, MD, University of Iowa College of Public Health, Iowa City, asked Bhatt how clinicians were supposed to decide which of the many new agents now becoming available for patients with stable coronary artery disease to prescribe first.

“We often forget about rivaroxaban when we’re thinking about what to add next for our secondary prevention patients,” she said. “You also led the REDUCE-IT trial showing benefit of icosapent ethyl, icosapent ethyl icosapent ethyl icosapent ethyl and there is also ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors. For your patients with coronary disease who are already on a high dose statin which one of these would you add next?”

“That is what physicians need to ponder all the time,” Bhatt replied. “And when a patient has several risk factors that are not well controlled, I guess it’s all important. I go through a checklist with my patients and try and figure what they’re not on that could further reduce their risk.”

“In the COMPASS trial there was an overall positive result with rivaroxaban in the whole population. And now we have shown that patients with diabetes had an even greater absolute risk reduction. That pattern has also been seen with other classes of agents including the statins, PCSK9 inhibitors, and icosapent ethyl,” Bhatt noted.

“In patients with diabetes, I will usually target whatever is standing out most at that time. If their glycemic control is completely out of whack, then that is what I would focus on first, and these days often with a SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 agonist. If the LDL was out of control, I would add ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor. If the triglycerides were high, I would add icosapent ethyl. If multiple things were out of control, I would usually focus on the number most out of kilter first and try not to forget about everything else.”

But Bhatt noted that the challenge with rivaroxaban is that there is no test of thrombosis risk that would prompt the physician to take action. “Basically, the doctor just has to remember to do it. In that regard I would consider whether patients are at low bleeding risk and are they still at high ischemic risk despite controlling other risk factors and, if so, then I would add this low dose of rivaroxaban.”

Another panel member, Sekar Kathiresan, MD, asked Bhatt whether he recommended using available scores to assess the bleeding/thrombosis risk/benefits of adding an antithrombotic.

Bhatt replied: “That’s a terrific question. I guess the right answer is that we should be doing that, but in reality I have to concede that I don’t use these scores. They have shown appropriate C statistics in populations, but they are not fantastic in individual patients.”

“I have to confess that I use the eyeball test. There is nothing as good at predicting future bleeding as past bleeding. So if a patient has had bleeding problems on aspirin alone I wouldn’t add rivaroxaban. But if a patient hasn’t bled before, especially if they had some experience of dual antiplatelet therapy, then they would be good candidates for a low vascular dose of rivaroxaban,” he said.

“It is not as easy as with other drugs as there is always a bleeding trade-off with an antithrombotic. There is no such thing as a free lunch. So patients need careful assessment when considering prescribing rivaroxaban and regular reassessment over time to check if they have had any bleeding,” he added.

The COMPASS study was funded by Bayer. Bhatt reports honoraria from Bayer via the Population Health Research Institute for his role on the COMPASS trial and other research funding from Bayer to the Brigham & Women’s Hospital.

American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). Abstract 20-LB-20544-ACC. Presented March 28, 2020.

Circulation. Published online March 28, 2020. Full text.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the COMPASS trial of patients with stable coronary or peripheral artery disease (PAD), the combination of aspirin plus rivaroxaban, 2.5 mg twice daily, provided a larger absolute benefit on cardiovascular endpoints — including a threefold greater reduction in all-cause mortality — in patients with diabetes compared with the overall population.

The results of the diabetes subset of the COMPASS trial were presented by Deepak Bhatt, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Heart & Vascular Center, Boston, Massachusetts, on March 28 at the “virtual” American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). They were also simultaneously published online in Circulation.

“Use of dual pathway inhibition with low-dose rivaroxaban plus aspirin is particularly attractive in high-risk patients such as those with diabetes,” Bhatt concluded.

The COMPASS trial was first reported in 2017 and showed a new low dose of rivaroxaban (2.5-mg twice-daily; Xarelto, Bayer/Janssen Pharmaceuticals) plus aspirin, 100 mg once daily, was associated with a reduction in ischemic events and mortality and a superior net clinical benefit, balancing ischemic benefit with severe bleeding, compared with aspirin alone for secondary prevention in patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease.

But clinicians have been slow to prescribe rivaroxaban in this new and very large population.

“It’s been more than 2 years now since main COMPASS results, and there isn’t a sense that this therapy has really caught on,” chair of the current ACC session at which the diabetes subgroup results were presented, Hadley Wilson, MD, Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute, Charlotte, North Carolina, commented:

He asked Bhatt whether the diabetes subgroup may be “the tipping point that will make people aware of rivaroxaban and then that may trickle down to other patients.”

Bhatt said that he hoped that would be the case. “We as a steering committee of this trial could say the results were positive so rivaroxaban should now be used in everyone with stable coronary or peripheral arterial disease, but that is impractical and as you out point out it hasn’t happened,” he replied.

“In PAD/vascular medicine we have embraced this new therapy. In the broader cardiology world there are a lot of patients with stable coronary arterial disease at high ischemic risk who could take rivaroxaban, but its use is bound to be limited by it being a branded drug and the fact that there is a bleeding risk,” Bhatt explained.

“I think we need to identify patients with the highest ischemic risk and focus drugs such as these with a financial cost and a bleeding risk on those who most likely will derive the greatest absolute reduction in risk,” he said. “The PAD subgroup is one group where this is the case, and now we have shown the diabetes subgroup is another. And there is no incremental bleeding risk in this group over the whole population, so they get a much greater benefit without a greater risk. I hope this helps get rivaroxaban at the new lower dose used much more often.”

A total of 18,278 patients were randomly assigned to the combination of rivaroxaban and aspirin or aspirin alone in the COMPASS trial. Of these, 6922 had diabetes mellitus at baseline and 11,356 did not have diabetes.

Results from the current analysis show a consistent and similar relative risk reduction for benefit of rivaroxaban plus aspirin vs placebo plus aspirin in patients both with and without diabetes for the primary efficacy endpoint, a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke, with a hazard ratio of 0.74 for patients with diabetes and 0.77 for those without diabetes, the researchers report.

Because of the higher baseline risk in the diabetes subgroup, these patients had numerically larger absolute risk reductions with rivaroxaban than those without diabetes for the primary efficacy endpoint at 3 years (2.3% vs 1.4%) and for all-cause mortality (1.9% vs 0.6%).

These results translate into a number needed to treat (NNT) with rivaroxaban for 3 years to prevent one CV death, MI, or stroke of 44 for the diabetes group vs 73 for the nondiabetes group; the NNT to prevent one all-cause death was 54 for the diabetes group vs 167 for the nondiabetes group, the authors write.

Because the bleeding hazards were similar among patients with and without diabetes, the absolute net clinical benefit (MI, stroke, cardiovascular death, or bleeding leading to death or symptomatic bleeding into a critical organ) for rivaroxaban was “particularly favorable” in the diabetes group (2.7% fewer events in the diabetes group vs 1.0% fewer events in the nondiabetes group), they add.

Panelist at the ACC Featured Clinical Research session at which these results were presented, Jennifer Robinson, MD, University of Iowa College of Public Health, Iowa City, asked Bhatt how clinicians were supposed to decide which of the many new agents now becoming available for patients with stable coronary artery disease to prescribe first.

“We often forget about rivaroxaban when we’re thinking about what to add next for our secondary prevention patients,” she said. “You also led the REDUCE-IT trial showing benefit of icosapent ethyl, icosapent ethyl icosapent ethyl icosapent ethyl and there is also ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors. For your patients with coronary disease who are already on a high dose statin which one of these would you add next?”

“That is what physicians need to ponder all the time,” Bhatt replied. “And when a patient has several risk factors that are not well controlled, I guess it’s all important. I go through a checklist with my patients and try and figure what they’re not on that could further reduce their risk.”

“In the COMPASS trial there was an overall positive result with rivaroxaban in the whole population. And now we have shown that patients with diabetes had an even greater absolute risk reduction. That pattern has also been seen with other classes of agents including the statins, PCSK9 inhibitors, and icosapent ethyl,” Bhatt noted.

“In patients with diabetes, I will usually target whatever is standing out most at that time. If their glycemic control is completely out of whack, then that is what I would focus on first, and these days often with a SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 agonist. If the LDL was out of control, I would add ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor. If the triglycerides were high, I would add icosapent ethyl. If multiple things were out of control, I would usually focus on the number most out of kilter first and try not to forget about everything else.”

But Bhatt noted that the challenge with rivaroxaban is that there is no test of thrombosis risk that would prompt the physician to take action. “Basically, the doctor just has to remember to do it. In that regard I would consider whether patients are at low bleeding risk and are they still at high ischemic risk despite controlling other risk factors and, if so, then I would add this low dose of rivaroxaban.”

Another panel member, Sekar Kathiresan, MD, asked Bhatt whether he recommended using available scores to assess the bleeding/thrombosis risk/benefits of adding an antithrombotic.

Bhatt replied: “That’s a terrific question. I guess the right answer is that we should be doing that, but in reality I have to concede that I don’t use these scores. They have shown appropriate C statistics in populations, but they are not fantastic in individual patients.”

“I have to confess that I use the eyeball test. There is nothing as good at predicting future bleeding as past bleeding. So if a patient has had bleeding problems on aspirin alone I wouldn’t add rivaroxaban. But if a patient hasn’t bled before, especially if they had some experience of dual antiplatelet therapy, then they would be good candidates for a low vascular dose of rivaroxaban,” he said.

“It is not as easy as with other drugs as there is always a bleeding trade-off with an antithrombotic. There is no such thing as a free lunch. So patients need careful assessment when considering prescribing rivaroxaban and regular reassessment over time to check if they have had any bleeding,” he added.

The COMPASS study was funded by Bayer. Bhatt reports honoraria from Bayer via the Population Health Research Institute for his role on the COMPASS trial and other research funding from Bayer to the Brigham & Women’s Hospital.

American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). Abstract 20-LB-20544-ACC. Presented March 28, 2020.

Circulation. Published online March 28, 2020. Full text.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

UK TAVI: Similar outcomes to surgery in real world

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) was not inferior to conventional surgery with respect to death from any cause at 1 year in a new real-world study in patients age 70 years or older with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis at increased operative risk due to age or comorbidity.

The UK TAVI study was presented March 29 at the “virtual” American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC).

The trial involved a broad group of patients who were treated at every medical center that performs the transcatheter procedure across the United Kingdom.

“The importance of this trial is that it confirms the effectiveness of the TAVR strategy in a real-world setting,” said lead author, William D. Toff, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of Leicester, United Kingdom.

Previous clinical trials have found TAVR to be noninferior or superior to open-heart surgery for various patient groups, but most trials have been limited to medical centers that perform a high volume of procedures or focus on the use of specific types of replacement valves, he noted.

“Our results are concordant with those from earlier trials in intermediate- and low-risk patients, but those earlier trials were performed in the best centers and had many exclusion criteria. We have replicated those results in populations more representative of the real world.”

“I think it is a very important message that supports the findings in earlier trials that were focused on showing whether TAVR can work under ideal conditions, while our trial shows that it does work in real-world clinical practice,” he added.

The UK TAVI trial enrolled 913 patients referred for treatment of severe aortic stenosis at 34 UK sites from 2014 to 2018. They were randomly assigned to receive TAVR or open-heart surgery.

Enrollment was limited to participants age 70 years or older (with additional risk factors) or age 80 years or older (with or without additional risk factors). The average age was 81 years.

Overall, participants were at intermediate to low risk from surgery, with a median Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk score of 2.6%. However, researchers did not specify a particular risk score cutoff for enrollment.

“This allowed the trial to evolve along with changes in guidelines and practice regarding TAVR over the course of the study and to reflect physicians’ nuanced, real-world approach to considering risk in decision-making rather than taking a formulaic approach,” Toff said.

At 1 year, the rate of death from any cause (the primary endpoint) was 4.6% in the TAVR group and 6.6% in the surgery group, a difference that met the trial’s prespecified threshold for noninferiority of TAVR.

Rates of death from cardiovascular disease or stroke were also similar between the two groups.

Patients who received TAVR had a significantly higher rate of vascular complications (4.8%) than those receiving surgery (1.3%).

TAVR patients were also more likely to have a pacemaker implanted. This occurred in 12.2% of TAVR patients and 6.6% of those undergoing surgery.

In addition, patients who underwent TAVR had a higher rate of aortic regurgitation. Mild aortic regurgitation occurred at 1 year in 38.3% of the TAVR group and 11.7% of the surgery group, whereas moderate regurgitation occurred in 2.3% of TAVR patients and 0.6% of surgery patients.

On the other hand, patients undergoing TAVR had a significantly lower rate of major bleeding complications, which occurred in 6.3% of patients having TAVR and 17.1% of those undergoing surgery.

TAVR was also associated with a shorter hospital stay, fewer days in intensive care, and a faster improvement in functional capacity and quality of life. Functional capacity and quality-of-life measures at 6 weeks after the procedure were better in the TAVR group but by 1 year they were similar in the two groups.

“Longer follow-up is required to confirm sustained clinical benefit and valve durability to inform clinical practice, particularly in younger patients,” Toff concluded.

“The results from our trial and others are encouraging, but patients need to be fully informed and know that the long-term durability of the TAVR valves and the long-term implications of the increased risk of aortic regurgitation are still uncertain,” he added.

The researchers plan to continue to track outcomes for a minimum of 5 years.

Discussant of the UK TAVI trial at an ACC press conference, Julia Grapsa, MD, Guys and St Thomas NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom, said it was a well-designed study.

“It was impressive to see so many UK sites and the age range of patients from 70 to 91 years, and the shorter hospital stays and functional recoveries as well as reduced major bleeding in the TAVR group,” Grapsa said.

“But something that was very striking to me was the increase in moderate aortic regurgitation in the TAVR arm, 2.3% versus 0.6% in the surgical arm, so it is very important to keep following these patients long term,” she added.

In answer to a question during the main session about using age alone as an inclusion criterion in those over 80 years old, Toff said, “We were more comfortable taking all comers over 80 years of age because of the uncertainty about TAVR is more in relation to its durability and the clinical significance of the aortic regurgitation, which may have consequences in the longer term. But the longer term for the over 80s is obviously less of a problem than for those in their 70s.”

This study was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. Toff reports no disclosures.

American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). Abstract 20-LB-20410-ACC. Presented March 29, 2020.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) was not inferior to conventional surgery with respect to death from any cause at 1 year in a new real-world study in patients age 70 years or older with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis at increased operative risk due to age or comorbidity.

The UK TAVI study was presented March 29 at the “virtual” American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC).

The trial involved a broad group of patients who were treated at every medical center that performs the transcatheter procedure across the United Kingdom.

“The importance of this trial is that it confirms the effectiveness of the TAVR strategy in a real-world setting,” said lead author, William D. Toff, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of Leicester, United Kingdom.

Previous clinical trials have found TAVR to be noninferior or superior to open-heart surgery for various patient groups, but most trials have been limited to medical centers that perform a high volume of procedures or focus on the use of specific types of replacement valves, he noted.

“Our results are concordant with those from earlier trials in intermediate- and low-risk patients, but those earlier trials were performed in the best centers and had many exclusion criteria. We have replicated those results in populations more representative of the real world.”

“I think it is a very important message that supports the findings in earlier trials that were focused on showing whether TAVR can work under ideal conditions, while our trial shows that it does work in real-world clinical practice,” he added.

The UK TAVI trial enrolled 913 patients referred for treatment of severe aortic stenosis at 34 UK sites from 2014 to 2018. They were randomly assigned to receive TAVR or open-heart surgery.

Enrollment was limited to participants age 70 years or older (with additional risk factors) or age 80 years or older (with or without additional risk factors). The average age was 81 years.

Overall, participants were at intermediate to low risk from surgery, with a median Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk score of 2.6%. However, researchers did not specify a particular risk score cutoff for enrollment.

“This allowed the trial to evolve along with changes in guidelines and practice regarding TAVR over the course of the study and to reflect physicians’ nuanced, real-world approach to considering risk in decision-making rather than taking a formulaic approach,” Toff said.

At 1 year, the rate of death from any cause (the primary endpoint) was 4.6% in the TAVR group and 6.6% in the surgery group, a difference that met the trial’s prespecified threshold for noninferiority of TAVR.

Rates of death from cardiovascular disease or stroke were also similar between the two groups.

Patients who received TAVR had a significantly higher rate of vascular complications (4.8%) than those receiving surgery (1.3%).

TAVR patients were also more likely to have a pacemaker implanted. This occurred in 12.2% of TAVR patients and 6.6% of those undergoing surgery.

In addition, patients who underwent TAVR had a higher rate of aortic regurgitation. Mild aortic regurgitation occurred at 1 year in 38.3% of the TAVR group and 11.7% of the surgery group, whereas moderate regurgitation occurred in 2.3% of TAVR patients and 0.6% of surgery patients.

On the other hand, patients undergoing TAVR had a significantly lower rate of major bleeding complications, which occurred in 6.3% of patients having TAVR and 17.1% of those undergoing surgery.

TAVR was also associated with a shorter hospital stay, fewer days in intensive care, and a faster improvement in functional capacity and quality of life. Functional capacity and quality-of-life measures at 6 weeks after the procedure were better in the TAVR group but by 1 year they were similar in the two groups.

“Longer follow-up is required to confirm sustained clinical benefit and valve durability to inform clinical practice, particularly in younger patients,” Toff concluded.

“The results from our trial and others are encouraging, but patients need to be fully informed and know that the long-term durability of the TAVR valves and the long-term implications of the increased risk of aortic regurgitation are still uncertain,” he added.

The researchers plan to continue to track outcomes for a minimum of 5 years.

Discussant of the UK TAVI trial at an ACC press conference, Julia Grapsa, MD, Guys and St Thomas NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom, said it was a well-designed study.

“It was impressive to see so many UK sites and the age range of patients from 70 to 91 years, and the shorter hospital stays and functional recoveries as well as reduced major bleeding in the TAVR group,” Grapsa said.

“But something that was very striking to me was the increase in moderate aortic regurgitation in the TAVR arm, 2.3% versus 0.6% in the surgical arm, so it is very important to keep following these patients long term,” she added.

In answer to a question during the main session about using age alone as an inclusion criterion in those over 80 years old, Toff said, “We were more comfortable taking all comers over 80 years of age because of the uncertainty about TAVR is more in relation to its durability and the clinical significance of the aortic regurgitation, which may have consequences in the longer term. But the longer term for the over 80s is obviously less of a problem than for those in their 70s.”

This study was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. Toff reports no disclosures.

American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). Abstract 20-LB-20410-ACC. Presented March 29, 2020.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) was not inferior to conventional surgery with respect to death from any cause at 1 year in a new real-world study in patients age 70 years or older with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis at increased operative risk due to age or comorbidity.

The UK TAVI study was presented March 29 at the “virtual” American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC).

The trial involved a broad group of patients who were treated at every medical center that performs the transcatheter procedure across the United Kingdom.

“The importance of this trial is that it confirms the effectiveness of the TAVR strategy in a real-world setting,” said lead author, William D. Toff, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of Leicester, United Kingdom.

Previous clinical trials have found TAVR to be noninferior or superior to open-heart surgery for various patient groups, but most trials have been limited to medical centers that perform a high volume of procedures or focus on the use of specific types of replacement valves, he noted.

“Our results are concordant with those from earlier trials in intermediate- and low-risk patients, but those earlier trials were performed in the best centers and had many exclusion criteria. We have replicated those results in populations more representative of the real world.”

“I think it is a very important message that supports the findings in earlier trials that were focused on showing whether TAVR can work under ideal conditions, while our trial shows that it does work in real-world clinical practice,” he added.

The UK TAVI trial enrolled 913 patients referred for treatment of severe aortic stenosis at 34 UK sites from 2014 to 2018. They were randomly assigned to receive TAVR or open-heart surgery.

Enrollment was limited to participants age 70 years or older (with additional risk factors) or age 80 years or older (with or without additional risk factors). The average age was 81 years.

Overall, participants were at intermediate to low risk from surgery, with a median Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk score of 2.6%. However, researchers did not specify a particular risk score cutoff for enrollment.

“This allowed the trial to evolve along with changes in guidelines and practice regarding TAVR over the course of the study and to reflect physicians’ nuanced, real-world approach to considering risk in decision-making rather than taking a formulaic approach,” Toff said.

At 1 year, the rate of death from any cause (the primary endpoint) was 4.6% in the TAVR group and 6.6% in the surgery group, a difference that met the trial’s prespecified threshold for noninferiority of TAVR.

Rates of death from cardiovascular disease or stroke were also similar between the two groups.

Patients who received TAVR had a significantly higher rate of vascular complications (4.8%) than those receiving surgery (1.3%).

TAVR patients were also more likely to have a pacemaker implanted. This occurred in 12.2% of TAVR patients and 6.6% of those undergoing surgery.

In addition, patients who underwent TAVR had a higher rate of aortic regurgitation. Mild aortic regurgitation occurred at 1 year in 38.3% of the TAVR group and 11.7% of the surgery group, whereas moderate regurgitation occurred in 2.3% of TAVR patients and 0.6% of surgery patients.

On the other hand, patients undergoing TAVR had a significantly lower rate of major bleeding complications, which occurred in 6.3% of patients having TAVR and 17.1% of those undergoing surgery.

TAVR was also associated with a shorter hospital stay, fewer days in intensive care, and a faster improvement in functional capacity and quality of life. Functional capacity and quality-of-life measures at 6 weeks after the procedure were better in the TAVR group but by 1 year they were similar in the two groups.

“Longer follow-up is required to confirm sustained clinical benefit and valve durability to inform clinical practice, particularly in younger patients,” Toff concluded.

“The results from our trial and others are encouraging, but patients need to be fully informed and know that the long-term durability of the TAVR valves and the long-term implications of the increased risk of aortic regurgitation are still uncertain,” he added.

The researchers plan to continue to track outcomes for a minimum of 5 years.

Discussant of the UK TAVI trial at an ACC press conference, Julia Grapsa, MD, Guys and St Thomas NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom, said it was a well-designed study.

“It was impressive to see so many UK sites and the age range of patients from 70 to 91 years, and the shorter hospital stays and functional recoveries as well as reduced major bleeding in the TAVR group,” Grapsa said.

“But something that was very striking to me was the increase in moderate aortic regurgitation in the TAVR arm, 2.3% versus 0.6% in the surgical arm, so it is very important to keep following these patients long term,” she added.

In answer to a question during the main session about using age alone as an inclusion criterion in those over 80 years old, Toff said, “We were more comfortable taking all comers over 80 years of age because of the uncertainty about TAVR is more in relation to its durability and the clinical significance of the aortic regurgitation, which may have consequences in the longer term. But the longer term for the over 80s is obviously less of a problem than for those in their 70s.”

This study was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. Toff reports no disclosures.

American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). Abstract 20-LB-20410-ACC. Presented March 29, 2020.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

VICTORIA: Vericiguat seen as novel success in tough-to-treat, high-risk heart failure

Not too many years ago, clinicians who treat patients with heart failure, especially those at high risk for decompensation, lamented what seemed a dearth of new drug therapy options.

Now, with the toolbox brimming with new guideline-supported alternatives, .

Importantly, it entered an especially high-risk population with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF); everyone in the trial had experienced a prior, usually quite recent, heart failure exacerbation.

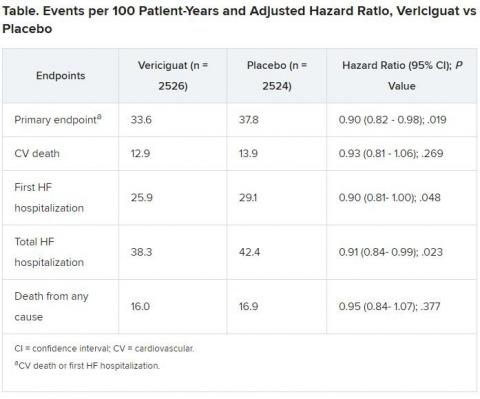

In such patients, the addition of vericiguat (Merck/Bayer) to standard drug and device therapies was followed by a moderately but significantly reduced relative risk for the trial’s primary clinical endpoint over about 11 months.

Recipients benefited with a 10% drop in adjusted risk (P = .019) for cardiovascular (CV) death or first heart failure hospitalization compared to a placebo control group.

But researchers leading the 5050-patient Vericiguat Global Study in Subjects with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (VICTORIA), as well as unaffiliated experts who have studied the trial, say that in this case, risk reduction in absolute numbers is a more telling outcome.

“Remember who we’re talking about here in terms of the patients who have this degree of morbidity and mortality,” VICTORIA study chair Paul W. Armstrong, MD, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, pointing to the “incredible placebo-group event rate and relatively modest follow-up of 10.8 months.”

The control group’s primary-endpoint event rate was 37.8 per 100 patient-years, 4.2 points higher than the rate for patients who received vericiguat. “And from there you get a number needed to treat of 24 to prevent one event, which is low,” Armstrong said.

“Think about the hundreds of thousands of people with this disease and what that means at the public health level.” About one in four patients with heart failure experience such exacerbations each year, he said.

Armstrong is lead author on the 42-country trial’s publication today in the New England Journal of Medicine, timed to coincide with his online presentation for the American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). The annual session was conducted virtually this year following the traditional live meeting’s cancelation due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The VICTORIA presentation and publication flesh out the cursory top-line primary results that Merck unveiled in November 2019, which had not included the magnitude of the vericiguat relative benefit for the primary endpoint.

The trial represents “another win” for the treatment of heart failure, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, said as an invited discussant following Armstrong’s presentation.

“Hospitalization for heart failure generates a major inflection point in the natural history of this condition, with a marked change in the risk for re-hospitalization and death. Up until now, no prior therapies have attenuated this risk, except for more intensive processes and care improvement strategies,” he said.

“Now we have a therapy that may be the first one to change that natural history after a person with heart failure has had a worsening event.”

Interestingly, the primary-endpoint reduction was driven by a significant drop in heart failure hospitalizations, even within a fairly short follow-up time.

“What was fascinating is that the requisite number of events were accrued in less than 12 months — meaning that inexplicably, this is one of the few times we’ve had a trial where the event rate realized was higher than the event rate predicted,” Yancy observed for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

Although the effect size was similar to what was observed for dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) in DAPA-HF and sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis) in PARADIGM-HF, he said, VICTORIA’s population was much sicker and had an “astonishingly high” event rate even while receiving aggressive background heart failure therapy.

It included “triple therapy with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in 60% of patients, and at least double therapy in 90% of patients.” Also, Yancy said, 30% of the population had implantable devices, such as defibrillators and biventricular pacemakers.

Such patients with advanced, late-stage disease are common as the latest therapies for heart failure prolong their survival, notes Lynne W. Stevenson, MD, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, also as an invited discussant after Armstrong’s presentation.

“It’s a unique population with longer disease duration, more severe disease, and narrow options,” one in which personalized approaches are needed. Yet VICTORIA-like patients “have been actively excluded from all the trials that have shown benefit,” she said.

“VICTORIA finally addresses this population of decompensated patients,” she said, and seems to show that vericiguat may help some of them.

At the University of Glasgow, United Kingdom, John J.V. McMurray, MBChB, MD, agreed that the relative risk reduction was “small but significant,” but also that the control group’s event rate was “very high, reflecting the inclusion and exclusion criteria.”

As a result, McMurray told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, there was “quite a large absolute risk reduction and small number needed to treat. Also on the positive side: no significant excess of the adverse effects we might have been concerned about,” for example, hypotension.

Vericiguat, if ultimately approved in heart failure, “isn’t going to be first-line or widely used, but it is an additional asset,” he said. “Anything that helps in heart failure is valuable. There are always patients who can’t tolerate treatments, and always people who need more done.”

It’s appealing that the drug works by a long but unfruitfully explored mechanism that has little to do directly with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Vericiguat is a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator that boosts cyclic guanosine monophosphate activity along several pathways, potentiating the salutary pulmonary artery–vasodilating effects of nitric oxide. It improved natriuretic peptide levels in the preceding phase 2 SOCRATES-REDUCED study.

“This is not a me-too drug. It’s a new avenue for heart failure patients,” Armstrong said in an interview. It’s taken once daily, “was relatively easy to titrate up to the target dose, pretty well tolerated, and very safe. And remarkably, you don’t need to measure renal function.”

However, because the drug’s mechanism resides in the same neighborhood of biochemical pathways affected by chronic nitrates and by phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil and tadalafil, patients taking those drugs were excluded from VICTORIA. Acute nitrates were allowed, however.

“Hospitalization for heart failure generates a major inflection point in the natural history of this condition, with a marked change in the risk for re-hospitalization and death. Up until now, no prior therapies have attenuated this risk, except for more intensive processes and care improvement strategies,” he said.

“Now we have a therapy that may be the first one to change that natural history after a person with heart failure has had a worsening event.”

Interestingly, the primary-endpoint reduction was driven by a significant drop in heart failure hospitalizations, even within a fairly short follow-up time.

“What was fascinating is that the requisite number of events were accrued in less than 12 months — meaning that inexplicably, this is one of the few times we’ve had a trial where the event rate realized was higher than the event rate predicted,” Yancy observed for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

Although the effect size was similar to what was observed for dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) in DAPA-HF and sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto, Novartis) in PARADIGM-HF, he said, VICTORIA’s population was much sicker and had an “astonishingly high” event rate even while receiving aggressive background heart failure therapy.

It included “triple therapy with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in 60% of patients, and at least double therapy in 90% of patients.” Also, Yancy said, 30% of the population had implantable devices, such as defibrillators and biventricular pacemakers.

Such patients with advanced, late-stage disease are common as the latest therapies for heart failure prolong their survival, notes Lynne W. Stevenson, MD, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, also as an invited discussant after Armstrong’s presentation.

“It’s a unique population with longer disease duration, more severe disease, and narrow options,” one in which personalized approaches are needed. Yet VICTORIA-like patients “have been actively excluded from all the trials that have shown benefit,” she said.

“VICTORIA finally addresses this population of decompensated patients,” she said, and seems to show that vericiguat may help some of them.

At the University of Glasgow, United Kingdom, John J.V. McMurray, MBChB, MD, agreed that the relative risk reduction was “small but significant,” but also that the control group’s event rate was “very high, reflecting the inclusion and exclusion criteria.”

As a result, McMurray told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, there was “quite a large absolute risk reduction and small number needed to treat. Also on the positive side: no significant excess of the adverse effects we might have been concerned about,” for example, hypotension.

Vericiguat, if ultimately approved in heart failure, “isn’t going to be first-line or widely used, but it is an additional asset,” he said. “Anything that helps in heart failure is valuable. There are always patients who can’t tolerate treatments, and always people who need more done.”

It’s appealing that the drug works by a long but unfruitfully explored mechanism that has little to do directly with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Vericiguat is a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator that boosts cyclic guanosine monophosphate activity along several pathways, potentiating the salutary pulmonary artery–vasodilating effects of nitric oxide. It improved natriuretic peptide levels in the preceding phase 2 SOCRATES-REDUCED study.

“This is not a me-too drug. It’s a new avenue for heart failure patients,” Armstrong said in an interview. It’s taken once daily, “was relatively easy to titrate up to the target dose, pretty well tolerated, and very safe. And remarkably, you don’t need to measure renal function.”

However, because the drug’s mechanism resides in the same neighborhood of biochemical pathways affected by chronic nitrates and by phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil and tadalafil, patients taking those drugs were excluded from VICTORIA. Acute nitrates were allowed, however.

Symptomatic hypotension occurred in less than 10% and syncope in 4% or less of both groups; neither difference between the two groups was significant. Anemia developed more often in patients receiving vericiguat (7.6%) than in the control group (5.7%).

“We think that on balance, vericiguat is a useful alternative option for patients. But certainly the only thing we can say at this point is it works in the high-risk population that we studied,” Armstrong said. “Whether it works in lower-risk populations and how it compares is speculation, of course.”

The drug’s cost, whatever it might be if approved, is another factor affecting how it would be used, noted several observers.

“We don’t know what the cost-effectiveness will be. It should be reasonable because the benefit was on hospitalization. That’s a costly outcome,” Yancy said.

McMurray was also hopeful. “If the treatment is well tolerated and reasonably priced, it may still be a valuable asset for at least a subset of patients.”

VICTORIA was supported by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp and Bayer AG. Armstrong discloses receiving research grants from Merck, Bayer AG, Sanofi-Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, and CSL Ltd and consulting fees from Merck, Bayer AG, AstraZeneca, and Novartis. Y ancy has previously disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Stevenson has previously disclosed receiving research grants from Novartis, consulting or serving on an advisory board for Abbott and travel expenses or meals from Novartis and St Jude Medical. McMurray has previously disclosed nonfinancial support or other support from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Cardiorentis, Amgen, Oxford University/Bayer, Theracos, AbbVie, DalCor, Pfizer, Merck, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Vifor-Fresenius.

American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). Presented March 28, 2020. Session 402-08.

N Engl J Med. Published online March 28, 2020. Full text; Circulation. Published online March 28, 2020. Full text.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Not too many years ago, clinicians who treat patients with heart failure, especially those at high risk for decompensation, lamented what seemed a dearth of new drug therapy options.

Now, with the toolbox brimming with new guideline-supported alternatives, .

Importantly, it entered an especially high-risk population with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF); everyone in the trial had experienced a prior, usually quite recent, heart failure exacerbation.

In such patients, the addition of vericiguat (Merck/Bayer) to standard drug and device therapies was followed by a moderately but significantly reduced relative risk for the trial’s primary clinical endpoint over about 11 months.

Recipients benefited with a 10% drop in adjusted risk (P = .019) for cardiovascular (CV) death or first heart failure hospitalization compared to a placebo control group.

But researchers leading the 5050-patient Vericiguat Global Study in Subjects with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (VICTORIA), as well as unaffiliated experts who have studied the trial, say that in this case, risk reduction in absolute numbers is a more telling outcome.

“Remember who we’re talking about here in terms of the patients who have this degree of morbidity and mortality,” VICTORIA study chair Paul W. Armstrong, MD, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, pointing to the “incredible placebo-group event rate and relatively modest follow-up of 10.8 months.”

The control group’s primary-endpoint event rate was 37.8 per 100 patient-years, 4.2 points higher than the rate for patients who received vericiguat. “And from there you get a number needed to treat of 24 to prevent one event, which is low,” Armstrong said.

“Think about the hundreds of thousands of people with this disease and what that means at the public health level.” About one in four patients with heart failure experience such exacerbations each year, he said.

Armstrong is lead author on the 42-country trial’s publication today in the New England Journal of Medicine, timed to coincide with his online presentation for the American College of Cardiology 2020 Scientific Session (ACC.20)/World Congress of Cardiology (WCC). The annual session was conducted virtually this year following the traditional live meeting’s cancelation due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The VICTORIA presentation and publication flesh out the cursory top-line primary results that Merck unveiled in November 2019, which had not included the magnitude of the vericiguat relative benefit for the primary endpoint.

The trial represents “another win” for the treatment of heart failure, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, said as an invited discussant following Armstrong’s presentation.

“Hospitalization for heart failure generates a major inflection point in the natural history of this condition, with a marked change in the risk for re-hospitalization and death. Up until now, no prior therapies have attenuated this risk, except for more intensive processes and care improvement strategies,” he said.

“Now we have a therapy that may be the first one to change that natural history after a person with heart failure has had a worsening event.”

Interestingly, the primary-endpoint reduction was driven by a significant drop in heart failure hospitalizations, even within a fairly short follow-up time.