User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

Will COVID-19 finally trigger action on health disparities?

Because of stark racial disparities in COVID-19 infection and mortality, the pandemic is being called a “sentinel” and “bellwether” event that should push the United States to finally come to grips with disparities in health care.

When it comes to COVID-19, the pattern is “irrefutable”: Blacks in the United States are being infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are dying of COVID-19 at higher rates than whites, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, wrote in a viewpoint article published online April 15 in JAMA.

According to one recent survey, he noted, the infection rate is threefold higher and the death rate is sixfold higher in predominantly black counties in the United States relative to predominantly white counties.

A sixfold increase in the rate of death for blacks due to a now ubiquitous virus should be deemed “unconscionable” and a moment of “ethical reckoning,” Dr. Yancy wrote.

“Why is this uniquely important to me? I am an academic cardiologist; I study health care disparities; and I am a black man,” he wrote.

The COVID-19 pandemic may be the “bellwether” event that the United States has needed to fully address disparities in health care, Dr. Yancy said.

“Public health is complicated and social reengineering is complex, but change of this magnitude does not happen without a new resolve,” he concluded. “The U.S. has needed a trigger to fully address health care disparities; COVID-19 may be that bellwether event. Certainly, within the broad and powerful economic and legislative engines of the U.S., there is room to definitively address a scourge even worse than COVID-19: health care disparities. It only takes will. It is time to end the refrain.”

The question is, he asks, will the nation finally “think differently, and, as has been done in response to other major diseases, declare that a civil society will no longer accept disproportionate suffering?”

Keith C. Ferdinand, MD, Tulane University, New Orleans, doesn’t think so.

In a related editorial published online April 17 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, he points out that the 1985 Heckler Report, from the Department of Health and Human Services, documented higher racial/ethnic mortality rates and the need to correct them. This was followed in 2002 by a report from the Institute of Medicine called Unequal Treatment that also underscored health disparities.

Despite some progress, the goal of reducing and eventually eliminating racial/ethnic disparities has not been realized, Dr. Ferdinand said. “I think baked into the consciousness of the American psyche is that there are some people who have and some who have not,” he said in an interview.

“To some extent, some societies at some point become immune. We would not like to think that America, with its sense of egalitarianism, would get to that point, but maybe we have,” said Dr. Ferdinand.

A ‘sentinel event’

He points out that black people are not genetically or biologically predisposed to COVID-19 but are socially prone to coronavirus exposure and are more likely to have comorbid conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease, that fuel complications.

The “tragic” higher COVID-19 mortality among African Americans and other racial/ethnic minorities confirms “inadequate” efforts on the part of society to eliminate disparities in cardiovascular disease (CVD) and is a “sentinel event,” Dr. Ferdinand wrote.

A sentinel event, as defined by the Joint Commission, is an unexpected occurrence that leads to death or serious physical or psychological injury or the risk thereof, he explained.

“Conventionally identified sentinel events, such as unintended retention of foreign objects and fall-related events, are used to evaluate quality in hospital care. Similarly, disparate [African American] COVID-19 mortality reflects long-standing, unacceptable U.S. racial/ethnic and socioeconomic CVD inequities and unmasks system failures and unacceptable care to be caught and mitigated,” Dr. Ferdinand concluded.

Dr. Yancy and Dr. Ferdinand have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Because of stark racial disparities in COVID-19 infection and mortality, the pandemic is being called a “sentinel” and “bellwether” event that should push the United States to finally come to grips with disparities in health care.

When it comes to COVID-19, the pattern is “irrefutable”: Blacks in the United States are being infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are dying of COVID-19 at higher rates than whites, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, wrote in a viewpoint article published online April 15 in JAMA.

According to one recent survey, he noted, the infection rate is threefold higher and the death rate is sixfold higher in predominantly black counties in the United States relative to predominantly white counties.

A sixfold increase in the rate of death for blacks due to a now ubiquitous virus should be deemed “unconscionable” and a moment of “ethical reckoning,” Dr. Yancy wrote.

“Why is this uniquely important to me? I am an academic cardiologist; I study health care disparities; and I am a black man,” he wrote.

The COVID-19 pandemic may be the “bellwether” event that the United States has needed to fully address disparities in health care, Dr. Yancy said.

“Public health is complicated and social reengineering is complex, but change of this magnitude does not happen without a new resolve,” he concluded. “The U.S. has needed a trigger to fully address health care disparities; COVID-19 may be that bellwether event. Certainly, within the broad and powerful economic and legislative engines of the U.S., there is room to definitively address a scourge even worse than COVID-19: health care disparities. It only takes will. It is time to end the refrain.”

The question is, he asks, will the nation finally “think differently, and, as has been done in response to other major diseases, declare that a civil society will no longer accept disproportionate suffering?”

Keith C. Ferdinand, MD, Tulane University, New Orleans, doesn’t think so.

In a related editorial published online April 17 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, he points out that the 1985 Heckler Report, from the Department of Health and Human Services, documented higher racial/ethnic mortality rates and the need to correct them. This was followed in 2002 by a report from the Institute of Medicine called Unequal Treatment that also underscored health disparities.

Despite some progress, the goal of reducing and eventually eliminating racial/ethnic disparities has not been realized, Dr. Ferdinand said. “I think baked into the consciousness of the American psyche is that there are some people who have and some who have not,” he said in an interview.

“To some extent, some societies at some point become immune. We would not like to think that America, with its sense of egalitarianism, would get to that point, but maybe we have,” said Dr. Ferdinand.

A ‘sentinel event’

He points out that black people are not genetically or biologically predisposed to COVID-19 but are socially prone to coronavirus exposure and are more likely to have comorbid conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease, that fuel complications.

The “tragic” higher COVID-19 mortality among African Americans and other racial/ethnic minorities confirms “inadequate” efforts on the part of society to eliminate disparities in cardiovascular disease (CVD) and is a “sentinel event,” Dr. Ferdinand wrote.

A sentinel event, as defined by the Joint Commission, is an unexpected occurrence that leads to death or serious physical or psychological injury or the risk thereof, he explained.

“Conventionally identified sentinel events, such as unintended retention of foreign objects and fall-related events, are used to evaluate quality in hospital care. Similarly, disparate [African American] COVID-19 mortality reflects long-standing, unacceptable U.S. racial/ethnic and socioeconomic CVD inequities and unmasks system failures and unacceptable care to be caught and mitigated,” Dr. Ferdinand concluded.

Dr. Yancy and Dr. Ferdinand have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Because of stark racial disparities in COVID-19 infection and mortality, the pandemic is being called a “sentinel” and “bellwether” event that should push the United States to finally come to grips with disparities in health care.

When it comes to COVID-19, the pattern is “irrefutable”: Blacks in the United States are being infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are dying of COVID-19 at higher rates than whites, Clyde W. Yancy, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, wrote in a viewpoint article published online April 15 in JAMA.

According to one recent survey, he noted, the infection rate is threefold higher and the death rate is sixfold higher in predominantly black counties in the United States relative to predominantly white counties.

A sixfold increase in the rate of death for blacks due to a now ubiquitous virus should be deemed “unconscionable” and a moment of “ethical reckoning,” Dr. Yancy wrote.

“Why is this uniquely important to me? I am an academic cardiologist; I study health care disparities; and I am a black man,” he wrote.

The COVID-19 pandemic may be the “bellwether” event that the United States has needed to fully address disparities in health care, Dr. Yancy said.

“Public health is complicated and social reengineering is complex, but change of this magnitude does not happen without a new resolve,” he concluded. “The U.S. has needed a trigger to fully address health care disparities; COVID-19 may be that bellwether event. Certainly, within the broad and powerful economic and legislative engines of the U.S., there is room to definitively address a scourge even worse than COVID-19: health care disparities. It only takes will. It is time to end the refrain.”

The question is, he asks, will the nation finally “think differently, and, as has been done in response to other major diseases, declare that a civil society will no longer accept disproportionate suffering?”

Keith C. Ferdinand, MD, Tulane University, New Orleans, doesn’t think so.

In a related editorial published online April 17 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, he points out that the 1985 Heckler Report, from the Department of Health and Human Services, documented higher racial/ethnic mortality rates and the need to correct them. This was followed in 2002 by a report from the Institute of Medicine called Unequal Treatment that also underscored health disparities.

Despite some progress, the goal of reducing and eventually eliminating racial/ethnic disparities has not been realized, Dr. Ferdinand said. “I think baked into the consciousness of the American psyche is that there are some people who have and some who have not,” he said in an interview.

“To some extent, some societies at some point become immune. We would not like to think that America, with its sense of egalitarianism, would get to that point, but maybe we have,” said Dr. Ferdinand.

A ‘sentinel event’

He points out that black people are not genetically or biologically predisposed to COVID-19 but are socially prone to coronavirus exposure and are more likely to have comorbid conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease, that fuel complications.

The “tragic” higher COVID-19 mortality among African Americans and other racial/ethnic minorities confirms “inadequate” efforts on the part of society to eliminate disparities in cardiovascular disease (CVD) and is a “sentinel event,” Dr. Ferdinand wrote.

A sentinel event, as defined by the Joint Commission, is an unexpected occurrence that leads to death or serious physical or psychological injury or the risk thereof, he explained.

“Conventionally identified sentinel events, such as unintended retention of foreign objects and fall-related events, are used to evaluate quality in hospital care. Similarly, disparate [African American] COVID-19 mortality reflects long-standing, unacceptable U.S. racial/ethnic and socioeconomic CVD inequities and unmasks system failures and unacceptable care to be caught and mitigated,” Dr. Ferdinand concluded.

Dr. Yancy and Dr. Ferdinand have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Consensus recommendations on AMI management during COVID-19

A consensus statement from the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) outlines recommendations for a systematic approach for the care of patients with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The statement was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) remains the standard of care for patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) at PCI-capable hospitals when it can be provided in a timely fashion in a dedicated cardiac catheterization laboratory with an expert care team wearing personal protection equipment (PPE), the writing group advised.

“A fibrinolysis-based strategy may be entertained at non-PCI capable referral hospitals or in specific situations where primary PCI cannot be executed or is not deemed the best option,” they said.

SCAI President Ehtisham Mahmud, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and the writing group also said that clinicians should recognize that cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 are “complex” in patients presenting with AMI, myocarditis simulating a STEMI, stress cardiomyopathy, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, coronary spasm, or nonspecific myocardial injury.

A “broad differential diagnosis for ST elevations (including COVID-associated myocarditis) should be considered in the ED prior to choosing a reperfusion strategy,” they advised.

In the absence of hemodynamic instability or ongoing ischemic symptoms, non-STEMI patients with known or suspected COVID-19 are best managed with an initial medical stabilization strategy, the group said.

They also said it is “imperative that health care workers use appropriate PPE for all invasive procedures during this pandemic” and that new rapid COVID-19 testing be “expeditiously” disseminated to all hospitals that manage patients with AMI.

Major challenges are that the prevalence of the COVID-19 in the United States remains unknown and there is the risk for asymptomatic spread.

The writing group said it’s “critical” to “inform the public that we can minimize exposure to the coronavirus so they can continue to call the Emergency Medical System (EMS) for acute ischemic heart disease symptoms and therefore get the appropriate level of cardiac care that their presentation warrants.”

This research had no commercial funding. Dr. Mahmud reported receiving clinical trial research support from Corindus, Abbott Vascular, and CSI; consulting with Medtronic; and consulting and equity with Abiomed. A complete list of author disclosures is included with the original article.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A consensus statement from the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) outlines recommendations for a systematic approach for the care of patients with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The statement was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) remains the standard of care for patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) at PCI-capable hospitals when it can be provided in a timely fashion in a dedicated cardiac catheterization laboratory with an expert care team wearing personal protection equipment (PPE), the writing group advised.

“A fibrinolysis-based strategy may be entertained at non-PCI capable referral hospitals or in specific situations where primary PCI cannot be executed or is not deemed the best option,” they said.

SCAI President Ehtisham Mahmud, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and the writing group also said that clinicians should recognize that cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 are “complex” in patients presenting with AMI, myocarditis simulating a STEMI, stress cardiomyopathy, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, coronary spasm, or nonspecific myocardial injury.

A “broad differential diagnosis for ST elevations (including COVID-associated myocarditis) should be considered in the ED prior to choosing a reperfusion strategy,” they advised.

In the absence of hemodynamic instability or ongoing ischemic symptoms, non-STEMI patients with known or suspected COVID-19 are best managed with an initial medical stabilization strategy, the group said.

They also said it is “imperative that health care workers use appropriate PPE for all invasive procedures during this pandemic” and that new rapid COVID-19 testing be “expeditiously” disseminated to all hospitals that manage patients with AMI.

Major challenges are that the prevalence of the COVID-19 in the United States remains unknown and there is the risk for asymptomatic spread.

The writing group said it’s “critical” to “inform the public that we can minimize exposure to the coronavirus so they can continue to call the Emergency Medical System (EMS) for acute ischemic heart disease symptoms and therefore get the appropriate level of cardiac care that their presentation warrants.”

This research had no commercial funding. Dr. Mahmud reported receiving clinical trial research support from Corindus, Abbott Vascular, and CSI; consulting with Medtronic; and consulting and equity with Abiomed. A complete list of author disclosures is included with the original article.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A consensus statement from the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) outlines recommendations for a systematic approach for the care of patients with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The statement was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) remains the standard of care for patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) at PCI-capable hospitals when it can be provided in a timely fashion in a dedicated cardiac catheterization laboratory with an expert care team wearing personal protection equipment (PPE), the writing group advised.

“A fibrinolysis-based strategy may be entertained at non-PCI capable referral hospitals or in specific situations where primary PCI cannot be executed or is not deemed the best option,” they said.

SCAI President Ehtisham Mahmud, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, and the writing group also said that clinicians should recognize that cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 are “complex” in patients presenting with AMI, myocarditis simulating a STEMI, stress cardiomyopathy, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, coronary spasm, or nonspecific myocardial injury.

A “broad differential diagnosis for ST elevations (including COVID-associated myocarditis) should be considered in the ED prior to choosing a reperfusion strategy,” they advised.

In the absence of hemodynamic instability or ongoing ischemic symptoms, non-STEMI patients with known or suspected COVID-19 are best managed with an initial medical stabilization strategy, the group said.

They also said it is “imperative that health care workers use appropriate PPE for all invasive procedures during this pandemic” and that new rapid COVID-19 testing be “expeditiously” disseminated to all hospitals that manage patients with AMI.

Major challenges are that the prevalence of the COVID-19 in the United States remains unknown and there is the risk for asymptomatic spread.

The writing group said it’s “critical” to “inform the public that we can minimize exposure to the coronavirus so they can continue to call the Emergency Medical System (EMS) for acute ischemic heart disease symptoms and therefore get the appropriate level of cardiac care that their presentation warrants.”

This research had no commercial funding. Dr. Mahmud reported receiving clinical trial research support from Corindus, Abbott Vascular, and CSI; consulting with Medtronic; and consulting and equity with Abiomed. A complete list of author disclosures is included with the original article.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

New advocacy group aims to give ‘every physician’ a voice

A new advocacy organization is launching on April 28 to give “every physician” a voice in decisions that affect their professional lives. But this group doesn’t intend to use the top-down approach to decision making seen in many medical societies.

Paul Teirstein, MD, chief of cardiology for Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif., and founder of the new organization United Physicians, said in an interviewit is a nonprofit group that will operate through online participation.

He said

Projects would need the support of a two-thirds majority of United Physicians’ members to proceed with any proposals. Meetings will be held publicly online, Dr. Teirstein explained.

There is a need for a broad-based organization that will respond to the voice of practicing physicians rather than dictate legislative priorities from management ranks, he said.

Dr. Teirstein said he learned how challenging it is to bring physicians together on issues in 2014 in his battles against changes in maintenance of certification rules. The result of his efforts was the National Board of Physicians and Surgeons (NBPAS), set up to provide a means of certification different from the one offered by the American Board of Internal Medicine.

Dr. Teirstein has argued that the approach of ABIM unfairly burdened physicians with a stepped-up schedule of testing and relied on an outdated approach to the practice of medicine.

Physicians busy with their practices feel they lack a unified voice in contesting the growing administrative burden and unproductive federal and state policies, Dr. Teirstein said.

He cited the limited enrollment in the largest physician groups as evidence of how disenfranchised many clinicians feel. There are about 1 million professional active physicians in the United States, according to the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation. Yet, even the largest physician group, the American Medical Association, has about 250,000 members, according to its 2018 annual report

“Clearly, most physicians believe they have little voice when it comes to health care decisions,” Dr. Teirstein said. “Our physician associations are governed from the top down. The leaders set the agenda. There may be delegates, but does leadership really listen to the delegates? Do the delegates really listen to the physician community?”

On its website, AMA describes itself as “physicians’ powerful ally in patient care” that works with more than 190 state and specialty medical societies. In recent months, James L. Madara, MD, the group’s chief executive officer, has urged governors to remove obstacles for physicians who want to fill workforce gaps in COVID-19 hot spots, among other actions.

In its annual report, the AMA, which declined to comment for this article, said its membership rose by 3.4% in 2018, double the growth rate of the previous year, thanks to a membership drive.

“The campaign celebrates the powerful work of our physician members and showcases how their individual efforts – along with the AMA – are moving medicine forward,” wrote Dr. Madara and other organization leaders in the report.

What Dr. Teirstein proposes is an inversion of the structure used by other medical societies, in which he says leaders and delegates dictate priorities.

United Physicians will use meetings and votes held by members online to decide which projects to pursue. Fees would be kept nominal, likely about $10 a year, depending on the number of members. Fees would be subject to change on the basis of expenses. The AMA has a sliding fee schedule that tops out with annual dues for physicians in regular practice of $420.

“There are no delegates, no representatives, and no board of directors. We want every physician to join and every physician to vote on every issue,” Dr. Teirstein said.

He stressed that he sees United Physicians as being complementary to the AMA.

“We do not compete with other organizations. Ideally, other organizations will use the platform,” Dr. Teirstein said. “If the AMA is considering a new policy, it can use the United Physicians platform to measure physician support. For example, through online discussions, petitions, and voting, it might learn a proposed policy needs a few tweaks to be accepted by most physicians.”

No compensation

Dr. Teirstein is among physician leaders who in recent years have sought to rally their colleagues to fight back against growing administrative burdens.

In a 2015 article in JAMA that was written with Medscape’s editor in chief, Eric Topol, MD, Dr. Teirstein criticized the ABIM’s drive to have physicians complete tests every 2 years and participate in continuous certification instead of recertifying once a decade, as had been the practice.

Dr. Teirstein formed the NBPAS as an alternative path for certification, with Dr. Topol serving on the board for that organization. Dr. Topol also will serve as a member of the advisory board for Teirstein’s United Physicians.

Dr. Topol wrote an article that appeared in the New Yorker last August that argued for physicians to move beyond the confines of medical societies and seek a path for broad-based activism. He said he intended to challenge medical societies, which, for all the good they do, can sometimes lose focus on that core relationship in favor of the bottom line.

Dr. Topol said in an interview that his colleague’s new project is a “good idea for a democratized platform at a time when physician solidarity is needed more than ever.”

Dr. Teirstein plans to run United Physicians on a volunteer basis. This builds on the approach he has used for NBPAS. He and the directors of the NBPAS will receive no compensation, he said, as was confirmed by the NBPAS.

In contrast, Dr. Madara made about $2.5 million in total compensation for 2018, according to the organization’s Internal Revenue Service filing. Physicians who served as trustees and officials for the AMA that year received annual compensation that ranged from around $60,000 to $291,980, depending on their duties.

“Having volunteer leadership mitigates conflict of interest. It also ensures leadership has a ‘day job’ that keeps them in touch with issues impacting practicing physicians,” Dr. Teirstein said

Start-up costs for United Physicians will be supported by NBPAS, but it will function as a completely independent organization, he added.

In introducing the group, Dr. Teirstein outlined suggestions for proposals it might pursue. These include making hospitals secure adequate supplies of personal protective equipment ahead of health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

His outline also includes suggestions for issues that likely will persist beyond the response to the pandemic.

Dr. Teirstein proposed a project for persuading insurance companies to provide online calendar appointments for peer-to-peer patient preauthorization. Failure of the insurer’s representative to attend would trigger approval of authorization under this proposal. He also suggested a lobbying effort for specific reimbursement for peer-to-peer, patient preauthorization phone calls.

Dr. Teirstein said he hopes most of the proposals will come from physicians who join United Physicians. Still, it is unclear whether United Physicians will succeed. An initial challenge could be in sorting through a barrage of competing ideas submitted to United Physicians.

But Dr. Teirstein appears hopeful about the changes for this experiment in online advocacy. He intends for United Physicians to be a pathway for clinicians to translate their complaints about policies into calls for action, with only a short investment of their time.

“Most of us have wonderful, engrossing jobs. It’s hard to beat helping a patient, and most of us get to do it every day,” Dr. .Teirstein said. “Will we take the 30 seconds required to sign up and become a United Physicians member? Will we spend a little time each week reviewing the issues and voting? I think it’s an experiment worth watching.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A new advocacy organization is launching on April 28 to give “every physician” a voice in decisions that affect their professional lives. But this group doesn’t intend to use the top-down approach to decision making seen in many medical societies.

Paul Teirstein, MD, chief of cardiology for Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif., and founder of the new organization United Physicians, said in an interviewit is a nonprofit group that will operate through online participation.

He said

Projects would need the support of a two-thirds majority of United Physicians’ members to proceed with any proposals. Meetings will be held publicly online, Dr. Teirstein explained.

There is a need for a broad-based organization that will respond to the voice of practicing physicians rather than dictate legislative priorities from management ranks, he said.

Dr. Teirstein said he learned how challenging it is to bring physicians together on issues in 2014 in his battles against changes in maintenance of certification rules. The result of his efforts was the National Board of Physicians and Surgeons (NBPAS), set up to provide a means of certification different from the one offered by the American Board of Internal Medicine.

Dr. Teirstein has argued that the approach of ABIM unfairly burdened physicians with a stepped-up schedule of testing and relied on an outdated approach to the practice of medicine.

Physicians busy with their practices feel they lack a unified voice in contesting the growing administrative burden and unproductive federal and state policies, Dr. Teirstein said.

He cited the limited enrollment in the largest physician groups as evidence of how disenfranchised many clinicians feel. There are about 1 million professional active physicians in the United States, according to the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation. Yet, even the largest physician group, the American Medical Association, has about 250,000 members, according to its 2018 annual report

“Clearly, most physicians believe they have little voice when it comes to health care decisions,” Dr. Teirstein said. “Our physician associations are governed from the top down. The leaders set the agenda. There may be delegates, but does leadership really listen to the delegates? Do the delegates really listen to the physician community?”

On its website, AMA describes itself as “physicians’ powerful ally in patient care” that works with more than 190 state and specialty medical societies. In recent months, James L. Madara, MD, the group’s chief executive officer, has urged governors to remove obstacles for physicians who want to fill workforce gaps in COVID-19 hot spots, among other actions.

In its annual report, the AMA, which declined to comment for this article, said its membership rose by 3.4% in 2018, double the growth rate of the previous year, thanks to a membership drive.

“The campaign celebrates the powerful work of our physician members and showcases how their individual efforts – along with the AMA – are moving medicine forward,” wrote Dr. Madara and other organization leaders in the report.

What Dr. Teirstein proposes is an inversion of the structure used by other medical societies, in which he says leaders and delegates dictate priorities.

United Physicians will use meetings and votes held by members online to decide which projects to pursue. Fees would be kept nominal, likely about $10 a year, depending on the number of members. Fees would be subject to change on the basis of expenses. The AMA has a sliding fee schedule that tops out with annual dues for physicians in regular practice of $420.

“There are no delegates, no representatives, and no board of directors. We want every physician to join and every physician to vote on every issue,” Dr. Teirstein said.

He stressed that he sees United Physicians as being complementary to the AMA.

“We do not compete with other organizations. Ideally, other organizations will use the platform,” Dr. Teirstein said. “If the AMA is considering a new policy, it can use the United Physicians platform to measure physician support. For example, through online discussions, petitions, and voting, it might learn a proposed policy needs a few tweaks to be accepted by most physicians.”

No compensation

Dr. Teirstein is among physician leaders who in recent years have sought to rally their colleagues to fight back against growing administrative burdens.

In a 2015 article in JAMA that was written with Medscape’s editor in chief, Eric Topol, MD, Dr. Teirstein criticized the ABIM’s drive to have physicians complete tests every 2 years and participate in continuous certification instead of recertifying once a decade, as had been the practice.

Dr. Teirstein formed the NBPAS as an alternative path for certification, with Dr. Topol serving on the board for that organization. Dr. Topol also will serve as a member of the advisory board for Teirstein’s United Physicians.

Dr. Topol wrote an article that appeared in the New Yorker last August that argued for physicians to move beyond the confines of medical societies and seek a path for broad-based activism. He said he intended to challenge medical societies, which, for all the good they do, can sometimes lose focus on that core relationship in favor of the bottom line.

Dr. Topol said in an interview that his colleague’s new project is a “good idea for a democratized platform at a time when physician solidarity is needed more than ever.”

Dr. Teirstein plans to run United Physicians on a volunteer basis. This builds on the approach he has used for NBPAS. He and the directors of the NBPAS will receive no compensation, he said, as was confirmed by the NBPAS.

In contrast, Dr. Madara made about $2.5 million in total compensation for 2018, according to the organization’s Internal Revenue Service filing. Physicians who served as trustees and officials for the AMA that year received annual compensation that ranged from around $60,000 to $291,980, depending on their duties.

“Having volunteer leadership mitigates conflict of interest. It also ensures leadership has a ‘day job’ that keeps them in touch with issues impacting practicing physicians,” Dr. Teirstein said

Start-up costs for United Physicians will be supported by NBPAS, but it will function as a completely independent organization, he added.

In introducing the group, Dr. Teirstein outlined suggestions for proposals it might pursue. These include making hospitals secure adequate supplies of personal protective equipment ahead of health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

His outline also includes suggestions for issues that likely will persist beyond the response to the pandemic.

Dr. Teirstein proposed a project for persuading insurance companies to provide online calendar appointments for peer-to-peer patient preauthorization. Failure of the insurer’s representative to attend would trigger approval of authorization under this proposal. He also suggested a lobbying effort for specific reimbursement for peer-to-peer, patient preauthorization phone calls.

Dr. Teirstein said he hopes most of the proposals will come from physicians who join United Physicians. Still, it is unclear whether United Physicians will succeed. An initial challenge could be in sorting through a barrage of competing ideas submitted to United Physicians.

But Dr. Teirstein appears hopeful about the changes for this experiment in online advocacy. He intends for United Physicians to be a pathway for clinicians to translate their complaints about policies into calls for action, with only a short investment of their time.

“Most of us have wonderful, engrossing jobs. It’s hard to beat helping a patient, and most of us get to do it every day,” Dr. .Teirstein said. “Will we take the 30 seconds required to sign up and become a United Physicians member? Will we spend a little time each week reviewing the issues and voting? I think it’s an experiment worth watching.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A new advocacy organization is launching on April 28 to give “every physician” a voice in decisions that affect their professional lives. But this group doesn’t intend to use the top-down approach to decision making seen in many medical societies.

Paul Teirstein, MD, chief of cardiology for Scripps Clinic in La Jolla, Calif., and founder of the new organization United Physicians, said in an interviewit is a nonprofit group that will operate through online participation.

He said

Projects would need the support of a two-thirds majority of United Physicians’ members to proceed with any proposals. Meetings will be held publicly online, Dr. Teirstein explained.

There is a need for a broad-based organization that will respond to the voice of practicing physicians rather than dictate legislative priorities from management ranks, he said.

Dr. Teirstein said he learned how challenging it is to bring physicians together on issues in 2014 in his battles against changes in maintenance of certification rules. The result of his efforts was the National Board of Physicians and Surgeons (NBPAS), set up to provide a means of certification different from the one offered by the American Board of Internal Medicine.

Dr. Teirstein has argued that the approach of ABIM unfairly burdened physicians with a stepped-up schedule of testing and relied on an outdated approach to the practice of medicine.

Physicians busy with their practices feel they lack a unified voice in contesting the growing administrative burden and unproductive federal and state policies, Dr. Teirstein said.

He cited the limited enrollment in the largest physician groups as evidence of how disenfranchised many clinicians feel. There are about 1 million professional active physicians in the United States, according to the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation. Yet, even the largest physician group, the American Medical Association, has about 250,000 members, according to its 2018 annual report

“Clearly, most physicians believe they have little voice when it comes to health care decisions,” Dr. Teirstein said. “Our physician associations are governed from the top down. The leaders set the agenda. There may be delegates, but does leadership really listen to the delegates? Do the delegates really listen to the physician community?”

On its website, AMA describes itself as “physicians’ powerful ally in patient care” that works with more than 190 state and specialty medical societies. In recent months, James L. Madara, MD, the group’s chief executive officer, has urged governors to remove obstacles for physicians who want to fill workforce gaps in COVID-19 hot spots, among other actions.

In its annual report, the AMA, which declined to comment for this article, said its membership rose by 3.4% in 2018, double the growth rate of the previous year, thanks to a membership drive.

“The campaign celebrates the powerful work of our physician members and showcases how their individual efforts – along with the AMA – are moving medicine forward,” wrote Dr. Madara and other organization leaders in the report.

What Dr. Teirstein proposes is an inversion of the structure used by other medical societies, in which he says leaders and delegates dictate priorities.

United Physicians will use meetings and votes held by members online to decide which projects to pursue. Fees would be kept nominal, likely about $10 a year, depending on the number of members. Fees would be subject to change on the basis of expenses. The AMA has a sliding fee schedule that tops out with annual dues for physicians in regular practice of $420.

“There are no delegates, no representatives, and no board of directors. We want every physician to join and every physician to vote on every issue,” Dr. Teirstein said.

He stressed that he sees United Physicians as being complementary to the AMA.

“We do not compete with other organizations. Ideally, other organizations will use the platform,” Dr. Teirstein said. “If the AMA is considering a new policy, it can use the United Physicians platform to measure physician support. For example, through online discussions, petitions, and voting, it might learn a proposed policy needs a few tweaks to be accepted by most physicians.”

No compensation

Dr. Teirstein is among physician leaders who in recent years have sought to rally their colleagues to fight back against growing administrative burdens.

In a 2015 article in JAMA that was written with Medscape’s editor in chief, Eric Topol, MD, Dr. Teirstein criticized the ABIM’s drive to have physicians complete tests every 2 years and participate in continuous certification instead of recertifying once a decade, as had been the practice.

Dr. Teirstein formed the NBPAS as an alternative path for certification, with Dr. Topol serving on the board for that organization. Dr. Topol also will serve as a member of the advisory board for Teirstein’s United Physicians.

Dr. Topol wrote an article that appeared in the New Yorker last August that argued for physicians to move beyond the confines of medical societies and seek a path for broad-based activism. He said he intended to challenge medical societies, which, for all the good they do, can sometimes lose focus on that core relationship in favor of the bottom line.

Dr. Topol said in an interview that his colleague’s new project is a “good idea for a democratized platform at a time when physician solidarity is needed more than ever.”

Dr. Teirstein plans to run United Physicians on a volunteer basis. This builds on the approach he has used for NBPAS. He and the directors of the NBPAS will receive no compensation, he said, as was confirmed by the NBPAS.

In contrast, Dr. Madara made about $2.5 million in total compensation for 2018, according to the organization’s Internal Revenue Service filing. Physicians who served as trustees and officials for the AMA that year received annual compensation that ranged from around $60,000 to $291,980, depending on their duties.

“Having volunteer leadership mitigates conflict of interest. It also ensures leadership has a ‘day job’ that keeps them in touch with issues impacting practicing physicians,” Dr. Teirstein said

Start-up costs for United Physicians will be supported by NBPAS, but it will function as a completely independent organization, he added.

In introducing the group, Dr. Teirstein outlined suggestions for proposals it might pursue. These include making hospitals secure adequate supplies of personal protective equipment ahead of health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

His outline also includes suggestions for issues that likely will persist beyond the response to the pandemic.

Dr. Teirstein proposed a project for persuading insurance companies to provide online calendar appointments for peer-to-peer patient preauthorization. Failure of the insurer’s representative to attend would trigger approval of authorization under this proposal. He also suggested a lobbying effort for specific reimbursement for peer-to-peer, patient preauthorization phone calls.

Dr. Teirstein said he hopes most of the proposals will come from physicians who join United Physicians. Still, it is unclear whether United Physicians will succeed. An initial challenge could be in sorting through a barrage of competing ideas submitted to United Physicians.

But Dr. Teirstein appears hopeful about the changes for this experiment in online advocacy. He intends for United Physicians to be a pathway for clinicians to translate their complaints about policies into calls for action, with only a short investment of their time.

“Most of us have wonderful, engrossing jobs. It’s hard to beat helping a patient, and most of us get to do it every day,” Dr. .Teirstein said. “Will we take the 30 seconds required to sign up and become a United Physicians member? Will we spend a little time each week reviewing the issues and voting? I think it’s an experiment worth watching.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

CMS suspends advance payment program to clinicians for COVID-19 relief

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will suspend its Medicare advance payment program for clinicians and is reevaluating how much to pay to hospitals going forward through particular COVID-19 relief initiatives. CMS announced the changes on April 26. Physicians and others who use the accelerated and advance Medicare payments program repay these advances, and they are typically given 1 year or less to repay the funding.

CMS said in a news release it will not accept new applications for the advanced Medicare payment, and it will be reevaluating all pending and new applications “in light of historical direct payments made available through the Department of Health & Human Services’ (HHS) Provider Relief Fund.”

The advance Medicare payment program predates COVID-19, although it previously was used on a much smaller scale. In the past 5 years, CMS approved about 100 total requests for advanced Medicare payment, with most being tied to natural disasters such as hurricanes.

CMS said it has approved, since March, more than 21,000 applications for advanced Medicare payment, totaling $59.6 billion, for hospitals and other organizations that bill its Part A program. In addition, CMS approved almost 24,000 applications for its Part B program, advancing $40.4 billion for physicians, other clinicians, and medical equipment suppliers.

CMS noted that Congress also has provided $175 billion in aid for the medical community that clinicians and medical organizations would not need to repay. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act enacted in March included $100 billion, and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, enacted March 24, includes another $75 billion.

A version of this article was originally published on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will suspend its Medicare advance payment program for clinicians and is reevaluating how much to pay to hospitals going forward through particular COVID-19 relief initiatives. CMS announced the changes on April 26. Physicians and others who use the accelerated and advance Medicare payments program repay these advances, and they are typically given 1 year or less to repay the funding.

CMS said in a news release it will not accept new applications for the advanced Medicare payment, and it will be reevaluating all pending and new applications “in light of historical direct payments made available through the Department of Health & Human Services’ (HHS) Provider Relief Fund.”

The advance Medicare payment program predates COVID-19, although it previously was used on a much smaller scale. In the past 5 years, CMS approved about 100 total requests for advanced Medicare payment, with most being tied to natural disasters such as hurricanes.

CMS said it has approved, since March, more than 21,000 applications for advanced Medicare payment, totaling $59.6 billion, for hospitals and other organizations that bill its Part A program. In addition, CMS approved almost 24,000 applications for its Part B program, advancing $40.4 billion for physicians, other clinicians, and medical equipment suppliers.

CMS noted that Congress also has provided $175 billion in aid for the medical community that clinicians and medical organizations would not need to repay. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act enacted in March included $100 billion, and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, enacted March 24, includes another $75 billion.

A version of this article was originally published on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will suspend its Medicare advance payment program for clinicians and is reevaluating how much to pay to hospitals going forward through particular COVID-19 relief initiatives. CMS announced the changes on April 26. Physicians and others who use the accelerated and advance Medicare payments program repay these advances, and they are typically given 1 year or less to repay the funding.

CMS said in a news release it will not accept new applications for the advanced Medicare payment, and it will be reevaluating all pending and new applications “in light of historical direct payments made available through the Department of Health & Human Services’ (HHS) Provider Relief Fund.”

The advance Medicare payment program predates COVID-19, although it previously was used on a much smaller scale. In the past 5 years, CMS approved about 100 total requests for advanced Medicare payment, with most being tied to natural disasters such as hurricanes.

CMS said it has approved, since March, more than 21,000 applications for advanced Medicare payment, totaling $59.6 billion, for hospitals and other organizations that bill its Part A program. In addition, CMS approved almost 24,000 applications for its Part B program, advancing $40.4 billion for physicians, other clinicians, and medical equipment suppliers.

CMS noted that Congress also has provided $175 billion in aid for the medical community that clinicians and medical organizations would not need to repay. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act enacted in March included $100 billion, and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, enacted March 24, includes another $75 billion.

A version of this article was originally published on Medscape.com.

Changing habits, sleep patterns, and home duties during the pandemic

Like you, I’m not sure when this weird Twilight Zone world of coronavirus will end. Even when it does, its effects will be with us for a long time to come.

But in some ways, they may be for the better. Hopefully some of these changes will stick. Like every new situation, I try to take away something of value from it.

As pithy as it sounds, I used to obsess (sort of) over the daily mail delivery. My secretary would check it mid-afternoon, and if it wasn’t there either she or I would run down again before we left. If it still wasn’t there I’d swing by the box when I came in early the next morning. On Saturdays, I’d sometimes drive in just to get the mail.

There certainly are things that come in that are important: payments, bills, medical records, legal cases to review ... but realistically a lot of mail is junk. Office-supply catalogs, CME or pharmaceutical ads, credit card promotions, and so on.

Now? I just don’t care. If I go several days without seeing patients at the office, the mail is at the back of my mind. It’s in a locked box and isn’t going anywhere. Why worry about it? Next time I’m there I can deal with it. It’s not worth thinking about, it’s just the mail. It’s not worth a special trip.

Sleep is another thing. For years my internal alarm has had me up around 4:00 a.m. (I don’t even bother to set one on my phone), and I get up and go in to get started on the day.

Now? I don’t think I’ve ever slept this much. If I have to go to my office, I’m much less rushed. Many days I don’t even have to do that. I walk down to my home office, call up my charts and the day’s video appointment schedule, and we’re off. Granted, once things return to speed, this will probably be back to normal.

My kids are all home from college, so I have the extra time at home to enjoy them and our dogs. My wife, an oncology infusion nurse, doesn’t get home until 6:00 each night, so for now I’ve become a stay-at-home dad. This is actually something I’ve always liked (in high school, I was voted “most likely to to be a house husband”). So I do the laundry and am in charge of dinner each night. I’m enjoying the last, as I get to pick things out, go through recipes, and cook. I won’t say I’m a great cook, but I’m learning and having fun. As strange as it sounds, being a house husband has always been something I wanted to do, so I’m appreciating the opportunity while it lasts.

I think all of us have come to accept this strange pause button that’s been pushed, and I’ll try to learn what I can from it and take that with me as I move forward.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Like you, I’m not sure when this weird Twilight Zone world of coronavirus will end. Even when it does, its effects will be with us for a long time to come.

But in some ways, they may be for the better. Hopefully some of these changes will stick. Like every new situation, I try to take away something of value from it.

As pithy as it sounds, I used to obsess (sort of) over the daily mail delivery. My secretary would check it mid-afternoon, and if it wasn’t there either she or I would run down again before we left. If it still wasn’t there I’d swing by the box when I came in early the next morning. On Saturdays, I’d sometimes drive in just to get the mail.

There certainly are things that come in that are important: payments, bills, medical records, legal cases to review ... but realistically a lot of mail is junk. Office-supply catalogs, CME or pharmaceutical ads, credit card promotions, and so on.

Now? I just don’t care. If I go several days without seeing patients at the office, the mail is at the back of my mind. It’s in a locked box and isn’t going anywhere. Why worry about it? Next time I’m there I can deal with it. It’s not worth thinking about, it’s just the mail. It’s not worth a special trip.

Sleep is another thing. For years my internal alarm has had me up around 4:00 a.m. (I don’t even bother to set one on my phone), and I get up and go in to get started on the day.

Now? I don’t think I’ve ever slept this much. If I have to go to my office, I’m much less rushed. Many days I don’t even have to do that. I walk down to my home office, call up my charts and the day’s video appointment schedule, and we’re off. Granted, once things return to speed, this will probably be back to normal.

My kids are all home from college, so I have the extra time at home to enjoy them and our dogs. My wife, an oncology infusion nurse, doesn’t get home until 6:00 each night, so for now I’ve become a stay-at-home dad. This is actually something I’ve always liked (in high school, I was voted “most likely to to be a house husband”). So I do the laundry and am in charge of dinner each night. I’m enjoying the last, as I get to pick things out, go through recipes, and cook. I won’t say I’m a great cook, but I’m learning and having fun. As strange as it sounds, being a house husband has always been something I wanted to do, so I’m appreciating the opportunity while it lasts.

I think all of us have come to accept this strange pause button that’s been pushed, and I’ll try to learn what I can from it and take that with me as I move forward.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Like you, I’m not sure when this weird Twilight Zone world of coronavirus will end. Even when it does, its effects will be with us for a long time to come.

But in some ways, they may be for the better. Hopefully some of these changes will stick. Like every new situation, I try to take away something of value from it.

As pithy as it sounds, I used to obsess (sort of) over the daily mail delivery. My secretary would check it mid-afternoon, and if it wasn’t there either she or I would run down again before we left. If it still wasn’t there I’d swing by the box when I came in early the next morning. On Saturdays, I’d sometimes drive in just to get the mail.

There certainly are things that come in that are important: payments, bills, medical records, legal cases to review ... but realistically a lot of mail is junk. Office-supply catalogs, CME or pharmaceutical ads, credit card promotions, and so on.

Now? I just don’t care. If I go several days without seeing patients at the office, the mail is at the back of my mind. It’s in a locked box and isn’t going anywhere. Why worry about it? Next time I’m there I can deal with it. It’s not worth thinking about, it’s just the mail. It’s not worth a special trip.

Sleep is another thing. For years my internal alarm has had me up around 4:00 a.m. (I don’t even bother to set one on my phone), and I get up and go in to get started on the day.

Now? I don’t think I’ve ever slept this much. If I have to go to my office, I’m much less rushed. Many days I don’t even have to do that. I walk down to my home office, call up my charts and the day’s video appointment schedule, and we’re off. Granted, once things return to speed, this will probably be back to normal.

My kids are all home from college, so I have the extra time at home to enjoy them and our dogs. My wife, an oncology infusion nurse, doesn’t get home until 6:00 each night, so for now I’ve become a stay-at-home dad. This is actually something I’ve always liked (in high school, I was voted “most likely to to be a house husband”). So I do the laundry and am in charge of dinner each night. I’m enjoying the last, as I get to pick things out, go through recipes, and cook. I won’t say I’m a great cook, but I’m learning and having fun. As strange as it sounds, being a house husband has always been something I wanted to do, so I’m appreciating the opportunity while it lasts.

I think all of us have come to accept this strange pause button that’s been pushed, and I’ll try to learn what I can from it and take that with me as I move forward.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Evidence on spironolactone safety, COVID-19 reassuring for acne patients

according to a report in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The virus needs androgens to infect cells, and uses androgen-dependent transmembrane protease serine 2 to prime viral protein spikes to anchor onto ACE2 receptors. Without that step, the virus can’t enter cells. Androgens are the only known activator in humans, so androgen blockers like spironolactone probably short-circuit the process, said the report’s lead author Carlos Wambier, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.032).

The lack of androgens could be a possible explanation as to why mortality is so rare among children with COVID-19, and why fatalities among men are higher than among women with COVID-19, he said in an interview.

There are a lot of androgen blocker candidates, but he said spironolactone – a mainstay of acne treatment – might well be the best for the pandemic because of its concomitant lung and heart benefits.

The message counters a post on Instagram in March from a New York City dermatologist in private practice, Ellen Marmur, MD, that raised a question about spironolactone. Concerned about the situation in New York, she reviewed the literature and found a 2005 study that reported that macrophages drawn from 10 heart failure patients had increased ACE2 activity and increased messenger RNA expression after the subjects had been on spironolactone 25 mg per day for a month.

In an interview, she said she has been sharing her concerns with patients on spironolactone and offering them an alternative, such as minocycline, until this issue is better elucidated. To date, she has had one young patient who declined to switch to another treatment, and about six patients who were comfortable switching to another treatment for 1-2 months. She said that she is “clearly cautious yet uncertain about the influence of chronic spironolactone for acne on COVID infection in acne patients,” and that eventually she would be interested in seeing retrospective data on outcomes of patients on spironolactone for hypertension versus acne during the pandemic.

Dr. Marmur’s post was spread on social media and was picked up by a few online news outlets.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said he’s been addressing concerns about spironolactone in educational webinars because of it.

He tells his audience that “you can’t make any claims” for COVID-19 based on the 2005 study. It was a small clinical study in heart failure patients and only assessed ACE2 expression on macrophages, not respiratory, cardiac, or mesangial cells, which are the relevant locations for viral invasion and damage. In fact, there are studies showing that spironolactone reduced ACE2 in renal mesangial cells. Also of note, spironolactone has been used with no indication of virus risk since the 1950s, he pointed out. The American Academy of Dermatology has not said to stop spironolactone.

At least one study is underway to see if spironolactone is beneficial: 100 mg twice a day for 5 days is being pitted against placebo in Turkey among people hospitalized with acute respiratory distress. The study will evaluate the effect of spironolactone on oxygenation.

“There’s no evidence to show spironolactone can increase mortality levels,” Dr. Wambier said. He is using it more now in patients with acne – a sign of androgen hyperactivity – convinced that it will protect against COVID-19. He even started his sister on it to help with androgenic hair loss, and maybe the virus.

Observations in Spain – increased prevalence of androgenic alopecia among hospitalized patients – support the androgen link; 29 of 41 men (71%) hospitalized with bilateral pneumonia had male pattern baldness, which was severe in 16 (39%), according to a recent report (J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13443). The expected prevalence in a similar age-matched population is 31%-53%.

“Based on the scientific rationale combined with this preliminary observation, we believe investigating the potential association between androgens and COVID‐19 disease severity warrants further merit,” concluded the authors, who included Dr. Wambier, and other dermatologists from the United States, as well as Spain, Australia, Croatia, and Switzerland. “If such an association is confirmed, antiandrogens could be evaluated as a potential treatment for COVID‐19 infection,” they wrote.

The numbers are holding up in a larger series from three Spanish hospitals, and also showing a greater prevalence of androgenic hair loss among hospitalized women, Dr. Wambier said in the interview.

Authors of the two studies include an employee of Applied Biology. No conflicts were declared in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology study; no disclosures were listed in the JAAD study. Dr. Friedman had no disclosures.

according to a report in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The virus needs androgens to infect cells, and uses androgen-dependent transmembrane protease serine 2 to prime viral protein spikes to anchor onto ACE2 receptors. Without that step, the virus can’t enter cells. Androgens are the only known activator in humans, so androgen blockers like spironolactone probably short-circuit the process, said the report’s lead author Carlos Wambier, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.032).

The lack of androgens could be a possible explanation as to why mortality is so rare among children with COVID-19, and why fatalities among men are higher than among women with COVID-19, he said in an interview.

There are a lot of androgen blocker candidates, but he said spironolactone – a mainstay of acne treatment – might well be the best for the pandemic because of its concomitant lung and heart benefits.

The message counters a post on Instagram in March from a New York City dermatologist in private practice, Ellen Marmur, MD, that raised a question about spironolactone. Concerned about the situation in New York, she reviewed the literature and found a 2005 study that reported that macrophages drawn from 10 heart failure patients had increased ACE2 activity and increased messenger RNA expression after the subjects had been on spironolactone 25 mg per day for a month.

In an interview, she said she has been sharing her concerns with patients on spironolactone and offering them an alternative, such as minocycline, until this issue is better elucidated. To date, she has had one young patient who declined to switch to another treatment, and about six patients who were comfortable switching to another treatment for 1-2 months. She said that she is “clearly cautious yet uncertain about the influence of chronic spironolactone for acne on COVID infection in acne patients,” and that eventually she would be interested in seeing retrospective data on outcomes of patients on spironolactone for hypertension versus acne during the pandemic.

Dr. Marmur’s post was spread on social media and was picked up by a few online news outlets.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said he’s been addressing concerns about spironolactone in educational webinars because of it.

He tells his audience that “you can’t make any claims” for COVID-19 based on the 2005 study. It was a small clinical study in heart failure patients and only assessed ACE2 expression on macrophages, not respiratory, cardiac, or mesangial cells, which are the relevant locations for viral invasion and damage. In fact, there are studies showing that spironolactone reduced ACE2 in renal mesangial cells. Also of note, spironolactone has been used with no indication of virus risk since the 1950s, he pointed out. The American Academy of Dermatology has not said to stop spironolactone.

At least one study is underway to see if spironolactone is beneficial: 100 mg twice a day for 5 days is being pitted against placebo in Turkey among people hospitalized with acute respiratory distress. The study will evaluate the effect of spironolactone on oxygenation.

“There’s no evidence to show spironolactone can increase mortality levels,” Dr. Wambier said. He is using it more now in patients with acne – a sign of androgen hyperactivity – convinced that it will protect against COVID-19. He even started his sister on it to help with androgenic hair loss, and maybe the virus.

Observations in Spain – increased prevalence of androgenic alopecia among hospitalized patients – support the androgen link; 29 of 41 men (71%) hospitalized with bilateral pneumonia had male pattern baldness, which was severe in 16 (39%), according to a recent report (J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13443). The expected prevalence in a similar age-matched population is 31%-53%.

“Based on the scientific rationale combined with this preliminary observation, we believe investigating the potential association between androgens and COVID‐19 disease severity warrants further merit,” concluded the authors, who included Dr. Wambier, and other dermatologists from the United States, as well as Spain, Australia, Croatia, and Switzerland. “If such an association is confirmed, antiandrogens could be evaluated as a potential treatment for COVID‐19 infection,” they wrote.

The numbers are holding up in a larger series from three Spanish hospitals, and also showing a greater prevalence of androgenic hair loss among hospitalized women, Dr. Wambier said in the interview.

Authors of the two studies include an employee of Applied Biology. No conflicts were declared in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology study; no disclosures were listed in the JAAD study. Dr. Friedman had no disclosures.

according to a report in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The virus needs androgens to infect cells, and uses androgen-dependent transmembrane protease serine 2 to prime viral protein spikes to anchor onto ACE2 receptors. Without that step, the virus can’t enter cells. Androgens are the only known activator in humans, so androgen blockers like spironolactone probably short-circuit the process, said the report’s lead author Carlos Wambier, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.032).

The lack of androgens could be a possible explanation as to why mortality is so rare among children with COVID-19, and why fatalities among men are higher than among women with COVID-19, he said in an interview.

There are a lot of androgen blocker candidates, but he said spironolactone – a mainstay of acne treatment – might well be the best for the pandemic because of its concomitant lung and heart benefits.

The message counters a post on Instagram in March from a New York City dermatologist in private practice, Ellen Marmur, MD, that raised a question about spironolactone. Concerned about the situation in New York, she reviewed the literature and found a 2005 study that reported that macrophages drawn from 10 heart failure patients had increased ACE2 activity and increased messenger RNA expression after the subjects had been on spironolactone 25 mg per day for a month.

In an interview, she said she has been sharing her concerns with patients on spironolactone and offering them an alternative, such as minocycline, until this issue is better elucidated. To date, she has had one young patient who declined to switch to another treatment, and about six patients who were comfortable switching to another treatment for 1-2 months. She said that she is “clearly cautious yet uncertain about the influence of chronic spironolactone for acne on COVID infection in acne patients,” and that eventually she would be interested in seeing retrospective data on outcomes of patients on spironolactone for hypertension versus acne during the pandemic.

Dr. Marmur’s post was spread on social media and was picked up by a few online news outlets.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said he’s been addressing concerns about spironolactone in educational webinars because of it.

He tells his audience that “you can’t make any claims” for COVID-19 based on the 2005 study. It was a small clinical study in heart failure patients and only assessed ACE2 expression on macrophages, not respiratory, cardiac, or mesangial cells, which are the relevant locations for viral invasion and damage. In fact, there are studies showing that spironolactone reduced ACE2 in renal mesangial cells. Also of note, spironolactone has been used with no indication of virus risk since the 1950s, he pointed out. The American Academy of Dermatology has not said to stop spironolactone.

At least one study is underway to see if spironolactone is beneficial: 100 mg twice a day for 5 days is being pitted against placebo in Turkey among people hospitalized with acute respiratory distress. The study will evaluate the effect of spironolactone on oxygenation.

“There’s no evidence to show spironolactone can increase mortality levels,” Dr. Wambier said. He is using it more now in patients with acne – a sign of androgen hyperactivity – convinced that it will protect against COVID-19. He even started his sister on it to help with androgenic hair loss, and maybe the virus.

Observations in Spain – increased prevalence of androgenic alopecia among hospitalized patients – support the androgen link; 29 of 41 men (71%) hospitalized with bilateral pneumonia had male pattern baldness, which was severe in 16 (39%), according to a recent report (J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13443). The expected prevalence in a similar age-matched population is 31%-53%.

“Based on the scientific rationale combined with this preliminary observation, we believe investigating the potential association between androgens and COVID‐19 disease severity warrants further merit,” concluded the authors, who included Dr. Wambier, and other dermatologists from the United States, as well as Spain, Australia, Croatia, and Switzerland. “If such an association is confirmed, antiandrogens could be evaluated as a potential treatment for COVID‐19 infection,” they wrote.

The numbers are holding up in a larger series from three Spanish hospitals, and also showing a greater prevalence of androgenic hair loss among hospitalized women, Dr. Wambier said in the interview.

Authors of the two studies include an employee of Applied Biology. No conflicts were declared in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology study; no disclosures were listed in the JAAD study. Dr. Friedman had no disclosures.

Rural ICU capacity could be strained by COVID-19

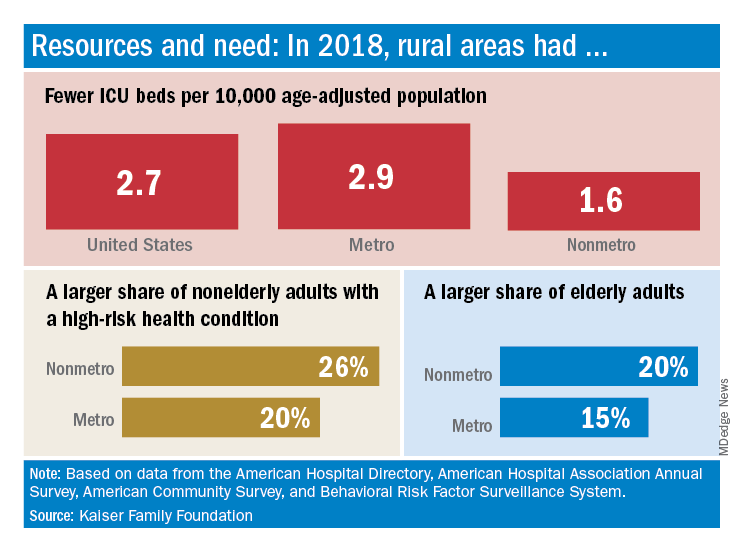

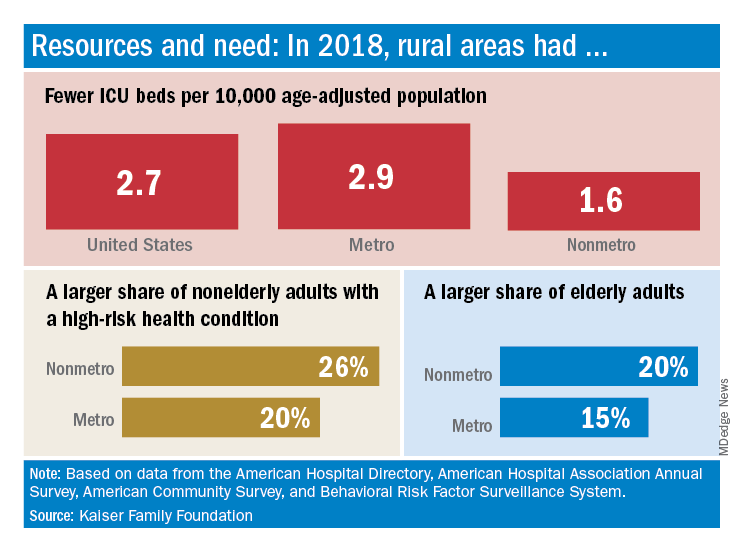

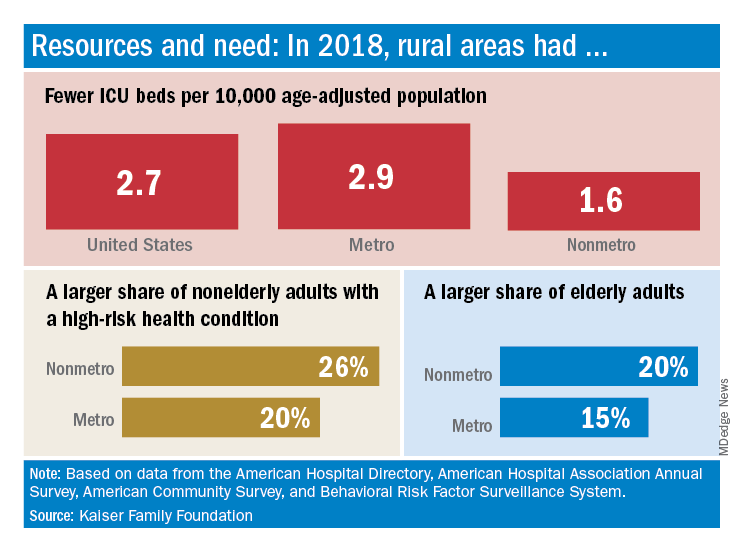

The nonmetropolitan, largely rural, areas of the United States have fewer ICU beds than do urban areas, but their populations may be at higher risk for COVID-19 complications, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

In 2018, the United States had 2.7 ICU beds per 10,000 age-adjusted population, but that number drops to 1.6 beds per 10,000 in nonmetro America and rises to 2.9 per 10,000 in metro areas. Counts for all hospital beds were much closer: 21.6 per 10,000 (rural) and 23.9 per 10,000 (urban), Kaiser investigators reported.

“The novel coronavirus was slower to spread to rural areas in the U.S., but that appears to be changing, with new outbreaks becoming evident in less densely populated parts of the country,” Kendal Orgera and associates said in a recent analysis.

Those rural areas have COVID-19 issues beyond ICU bed counts. Populations in nonmetro areas are less healthy – 26% of adults under age 65 years had a preexisting medical condition in 2018, compared with 20% in metro areas – and older – 20% of people are 65 and older, versus 15% in metro areas, they said.

“If coronavirus continues to spread in rural communities across the U.S., it is possible many [nonmetro] areas will face shortages of ICU beds with limited options to adapt. Patients in rural areas experiencing more severe illnesses may be transferred to hospitals with greater capacity, but if nearby urban areas are also overwhelmed, transfer may not be an option,” Ms. Orgera and associates wrote.

They defined nonmetro counties as those with rural towns of fewer than 2,500 people and/or “urban areas with populations ranging from 2,500 to 49,999 that are not part of larger labor market areas.” The Kaiser analysis involved 2018 data from the American Hospital Association, American Hospital Directory, American Community Survey, and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

The nonmetropolitan, largely rural, areas of the United States have fewer ICU beds than do urban areas, but their populations may be at higher risk for COVID-19 complications, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

In 2018, the United States had 2.7 ICU beds per 10,000 age-adjusted population, but that number drops to 1.6 beds per 10,000 in nonmetro America and rises to 2.9 per 10,000 in metro areas. Counts for all hospital beds were much closer: 21.6 per 10,000 (rural) and 23.9 per 10,000 (urban), Kaiser investigators reported.

“The novel coronavirus was slower to spread to rural areas in the U.S., but that appears to be changing, with new outbreaks becoming evident in less densely populated parts of the country,” Kendal Orgera and associates said in a recent analysis.

Those rural areas have COVID-19 issues beyond ICU bed counts. Populations in nonmetro areas are less healthy – 26% of adults under age 65 years had a preexisting medical condition in 2018, compared with 20% in metro areas – and older – 20% of people are 65 and older, versus 15% in metro areas, they said.

“If coronavirus continues to spread in rural communities across the U.S., it is possible many [nonmetro] areas will face shortages of ICU beds with limited options to adapt. Patients in rural areas experiencing more severe illnesses may be transferred to hospitals with greater capacity, but if nearby urban areas are also overwhelmed, transfer may not be an option,” Ms. Orgera and associates wrote.

They defined nonmetro counties as those with rural towns of fewer than 2,500 people and/or “urban areas with populations ranging from 2,500 to 49,999 that are not part of larger labor market areas.” The Kaiser analysis involved 2018 data from the American Hospital Association, American Hospital Directory, American Community Survey, and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

The nonmetropolitan, largely rural, areas of the United States have fewer ICU beds than do urban areas, but their populations may be at higher risk for COVID-19 complications, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.