User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

COVID-clogged ICUs ‘terrify’ those with chronic or emergency illness

Jessica Gosnell, MD, 41, from Portland, Oregon, lives daily with the knowledge that her rare disease — a form of hereditary angioedema — could cause a sudden, severe swelling in her throat that could require quick intubation and land her in an intensive care unit (ICU) for days.

“I’ve been hospitalized for throat swells three times in the last year,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Gosnell no longer practices medicine because of a combination of illnesses, but lives with her husband, Andrew, and two young children, and said they are all “terrified” she will have to go to the hospital amid a COVID-19 surge that had shrunk the number of available ICU beds to 152 from 780 in Oregon as of Aug. 30. Thirty percent of the beds are in use for patients with COVID-19.

She said her life depends on being near hospitals that have ICUs and having access to highly specialized medications, one of which can cost up to $50,000 for the rescue dose.

Her fear has her “literally living bedbound.” In addition to hereditary angioedema, she has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which weakens connective tissue. She wears a cervical collar 24/7 to keep from tearing tissues, as any tissue injury can trigger a swell.

Patients worry there won’t be room

As ICU beds in most states are filling with COVID-19 patients as the Delta variant spreads, fears are rising among people like Dr. Gosnell, who have chronic conditions and diseases with unpredictable emergency visits, who worry that if they need emergency care there won’t be room.

As of Aug. 30, in the United States, 79% of ICU beds nationally were in use, 30% of them for COVID-19 patients, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

In individual states, the picture is dire. Alabama has fewer than 10% of its ICU beds open across the entire state. In Florida, 93% of ICU beds are filled, 53% of them with COVID patients. In Louisiana, 87% of beds were already in use, 45% of them with COVID patients, just as category 4 hurricane Ida smashed into the coastline on Aug. 29.

News reports have told of people transported and airlifted as hospitals reach capacity.

In Bellville, Tex., U.S. Army veteran Daniel Wilkinson needed advanced care for gallstone pancreatitis that normally would take 30 minutes to treat, his Bellville doctor, Hasan Kakli, MD, told CBS News.

Mr. Wilkinson’s house was three doors from Bellville Hospital, but the hospital was not equipped to treat the condition. Calls to other hospitals found the same answer: no empty ICU beds. After a 7-hour wait on a stretcher, he was airlifted to a Veterans Affairs hospital in Houston, but it was too late. He died on August 22 at age 46.

Dr. Kakli said, “I’ve never lost a patient with this diagnosis. Ever. I’m scared that the next patient I see is someone that I can’t get to where they need to get to. We are playing musical chairs with 100 people and 10 chairs. When the music stops, what happens?”

Also in Texas in August, Joe Valdez, who was shot six times as an unlucky bystander in a domestic dispute, waited for more than a week for surgery at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, which was over capacity with COVID patients, the Washington Post reported.

Others with chronic diseases fear needing emergency services or even entering a hospital for regular care with the COVID surge.

Nicole Seefeldt, 44, from Easton, Penn., who had a double-lung transplant in 2016, said that she hasn’t been able to see her lung transplant specialists in Philadelphia — an hour-and-a-half drive — for almost 2 years because of fear of contracting COVID. Before the pandemic, she made the trip almost weekly.

“I protect my lungs like they’re children,” she said.

She relies on her local hospital for care, but has put off some needed care, such as a colonoscopy, and has relied on telemedicine because she wants to limit her hospital exposure.

Ms. Seefeldt now faces an eventual kidney transplant, as her kidney function has been reduced to 20%. In the meantime, she worries she will need emergency care for either her lungs or kidneys.

“For those of us who are chronically ill or disabled, what if we have an emergency that is not COVID-related? Are we going to be able to get a bed? Are we going to be able to get treatment? It’s not just COVID patients who come to the [emergency room],” she said.

A pandemic problem

Paul E. Casey, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said that high vaccination rates in Chicago have helped Rush continue to accommodate both non-COVID and COVID patients in the emergency department.

Though the hospital treated a large volume of COVID patients, “The vast majority of people we see and did see through the pandemic were non-COVID patents,” he said.

Dr. Casey said that in the first wave the hospital noticed a concerning drop in patients coming in for strokes and heart attacks — “things we knew hadn’t gone away.”

And the data backs it up. Over the course of the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health Interview Survey found that the percentage of Americans who reported seeing a doctor or health professional fell from 85% at the end of 2019 to about 80% in the first three months of 2021. The survey did not differentiate between in-person visits and telehealth appointments.

Medical practices and patients themselves postponed elective procedures and delayed routine visits during the early months of the crisis.

Patients also reported staying away from hospitals’ emergency departments throughout the pandemic. At the end of 2019, 22% of respondents reported visiting an emergency department in the past year. That dropped to 17% by the end of 2020, and was at 17.7% in the first 3 months of 2021.

Dr. Casey said that, in his hospital’s case, clear messaging became very important to assure patients it was safe to come back. And the message is still critical.

“We want to be loud and clear that patients should continue to seek care for those conditions,” Dr. Casey said. “Deferring healthcare only comes with the long-term sequelae of disease left untreated so we want people to be as proactive in seeking care as they always would be.”

In some cases, fears of entering emergency rooms because of excess patients and risk for infection are keeping some patients from seeking necessary care for minor injuries.

Jim Rickert, MD, an orthopedic surgeon with Indiana University Health in Bloomington, said that some of his patients have expressed fears of coming into the hospital for fractures.

Some patients, particularly elderly patients, he said, are having falls and fractures and wearing slings or braces at home rather than going into the hospital for injuries that need immediate attention.

Bones start healing incorrectly, Dr. Rickert said, and the correction becomes much more difficult.

Plea for vaccinations

Dr. Gosnell made a plea posted on her neighborhood news forum for people to get COVID vaccinations.

“It seems to me it’s easy for other people who are not in bodies like mine to take health for granted,” she said. “But there are a lot of us who live in very fragile bodies and our entire life is at the intersection of us and getting healthcare treatment. Small complications to getting treatment can be life altering.”

Dr. Gosnell, Ms. Seefeldt, Dr. Casey, and Dr. Rickert reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Jessica Gosnell, MD, 41, from Portland, Oregon, lives daily with the knowledge that her rare disease — a form of hereditary angioedema — could cause a sudden, severe swelling in her throat that could require quick intubation and land her in an intensive care unit (ICU) for days.

“I’ve been hospitalized for throat swells three times in the last year,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Gosnell no longer practices medicine because of a combination of illnesses, but lives with her husband, Andrew, and two young children, and said they are all “terrified” she will have to go to the hospital amid a COVID-19 surge that had shrunk the number of available ICU beds to 152 from 780 in Oregon as of Aug. 30. Thirty percent of the beds are in use for patients with COVID-19.

She said her life depends on being near hospitals that have ICUs and having access to highly specialized medications, one of which can cost up to $50,000 for the rescue dose.

Her fear has her “literally living bedbound.” In addition to hereditary angioedema, she has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which weakens connective tissue. She wears a cervical collar 24/7 to keep from tearing tissues, as any tissue injury can trigger a swell.

Patients worry there won’t be room

As ICU beds in most states are filling with COVID-19 patients as the Delta variant spreads, fears are rising among people like Dr. Gosnell, who have chronic conditions and diseases with unpredictable emergency visits, who worry that if they need emergency care there won’t be room.

As of Aug. 30, in the United States, 79% of ICU beds nationally were in use, 30% of them for COVID-19 patients, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

In individual states, the picture is dire. Alabama has fewer than 10% of its ICU beds open across the entire state. In Florida, 93% of ICU beds are filled, 53% of them with COVID patients. In Louisiana, 87% of beds were already in use, 45% of them with COVID patients, just as category 4 hurricane Ida smashed into the coastline on Aug. 29.

News reports have told of people transported and airlifted as hospitals reach capacity.

In Bellville, Tex., U.S. Army veteran Daniel Wilkinson needed advanced care for gallstone pancreatitis that normally would take 30 minutes to treat, his Bellville doctor, Hasan Kakli, MD, told CBS News.

Mr. Wilkinson’s house was three doors from Bellville Hospital, but the hospital was not equipped to treat the condition. Calls to other hospitals found the same answer: no empty ICU beds. After a 7-hour wait on a stretcher, he was airlifted to a Veterans Affairs hospital in Houston, but it was too late. He died on August 22 at age 46.

Dr. Kakli said, “I’ve never lost a patient with this diagnosis. Ever. I’m scared that the next patient I see is someone that I can’t get to where they need to get to. We are playing musical chairs with 100 people and 10 chairs. When the music stops, what happens?”

Also in Texas in August, Joe Valdez, who was shot six times as an unlucky bystander in a domestic dispute, waited for more than a week for surgery at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, which was over capacity with COVID patients, the Washington Post reported.

Others with chronic diseases fear needing emergency services or even entering a hospital for regular care with the COVID surge.

Nicole Seefeldt, 44, from Easton, Penn., who had a double-lung transplant in 2016, said that she hasn’t been able to see her lung transplant specialists in Philadelphia — an hour-and-a-half drive — for almost 2 years because of fear of contracting COVID. Before the pandemic, she made the trip almost weekly.

“I protect my lungs like they’re children,” she said.

She relies on her local hospital for care, but has put off some needed care, such as a colonoscopy, and has relied on telemedicine because she wants to limit her hospital exposure.

Ms. Seefeldt now faces an eventual kidney transplant, as her kidney function has been reduced to 20%. In the meantime, she worries she will need emergency care for either her lungs or kidneys.

“For those of us who are chronically ill or disabled, what if we have an emergency that is not COVID-related? Are we going to be able to get a bed? Are we going to be able to get treatment? It’s not just COVID patients who come to the [emergency room],” she said.

A pandemic problem

Paul E. Casey, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said that high vaccination rates in Chicago have helped Rush continue to accommodate both non-COVID and COVID patients in the emergency department.

Though the hospital treated a large volume of COVID patients, “The vast majority of people we see and did see through the pandemic were non-COVID patents,” he said.

Dr. Casey said that in the first wave the hospital noticed a concerning drop in patients coming in for strokes and heart attacks — “things we knew hadn’t gone away.”

And the data backs it up. Over the course of the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health Interview Survey found that the percentage of Americans who reported seeing a doctor or health professional fell from 85% at the end of 2019 to about 80% in the first three months of 2021. The survey did not differentiate between in-person visits and telehealth appointments.

Medical practices and patients themselves postponed elective procedures and delayed routine visits during the early months of the crisis.

Patients also reported staying away from hospitals’ emergency departments throughout the pandemic. At the end of 2019, 22% of respondents reported visiting an emergency department in the past year. That dropped to 17% by the end of 2020, and was at 17.7% in the first 3 months of 2021.

Dr. Casey said that, in his hospital’s case, clear messaging became very important to assure patients it was safe to come back. And the message is still critical.

“We want to be loud and clear that patients should continue to seek care for those conditions,” Dr. Casey said. “Deferring healthcare only comes with the long-term sequelae of disease left untreated so we want people to be as proactive in seeking care as they always would be.”

In some cases, fears of entering emergency rooms because of excess patients and risk for infection are keeping some patients from seeking necessary care for minor injuries.

Jim Rickert, MD, an orthopedic surgeon with Indiana University Health in Bloomington, said that some of his patients have expressed fears of coming into the hospital for fractures.

Some patients, particularly elderly patients, he said, are having falls and fractures and wearing slings or braces at home rather than going into the hospital for injuries that need immediate attention.

Bones start healing incorrectly, Dr. Rickert said, and the correction becomes much more difficult.

Plea for vaccinations

Dr. Gosnell made a plea posted on her neighborhood news forum for people to get COVID vaccinations.

“It seems to me it’s easy for other people who are not in bodies like mine to take health for granted,” she said. “But there are a lot of us who live in very fragile bodies and our entire life is at the intersection of us and getting healthcare treatment. Small complications to getting treatment can be life altering.”

Dr. Gosnell, Ms. Seefeldt, Dr. Casey, and Dr. Rickert reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Jessica Gosnell, MD, 41, from Portland, Oregon, lives daily with the knowledge that her rare disease — a form of hereditary angioedema — could cause a sudden, severe swelling in her throat that could require quick intubation and land her in an intensive care unit (ICU) for days.

“I’ve been hospitalized for throat swells three times in the last year,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Gosnell no longer practices medicine because of a combination of illnesses, but lives with her husband, Andrew, and two young children, and said they are all “terrified” she will have to go to the hospital amid a COVID-19 surge that had shrunk the number of available ICU beds to 152 from 780 in Oregon as of Aug. 30. Thirty percent of the beds are in use for patients with COVID-19.

She said her life depends on being near hospitals that have ICUs and having access to highly specialized medications, one of which can cost up to $50,000 for the rescue dose.

Her fear has her “literally living bedbound.” In addition to hereditary angioedema, she has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which weakens connective tissue. She wears a cervical collar 24/7 to keep from tearing tissues, as any tissue injury can trigger a swell.

Patients worry there won’t be room

As ICU beds in most states are filling with COVID-19 patients as the Delta variant spreads, fears are rising among people like Dr. Gosnell, who have chronic conditions and diseases with unpredictable emergency visits, who worry that if they need emergency care there won’t be room.

As of Aug. 30, in the United States, 79% of ICU beds nationally were in use, 30% of them for COVID-19 patients, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

In individual states, the picture is dire. Alabama has fewer than 10% of its ICU beds open across the entire state. In Florida, 93% of ICU beds are filled, 53% of them with COVID patients. In Louisiana, 87% of beds were already in use, 45% of them with COVID patients, just as category 4 hurricane Ida smashed into the coastline on Aug. 29.

News reports have told of people transported and airlifted as hospitals reach capacity.

In Bellville, Tex., U.S. Army veteran Daniel Wilkinson needed advanced care for gallstone pancreatitis that normally would take 30 minutes to treat, his Bellville doctor, Hasan Kakli, MD, told CBS News.

Mr. Wilkinson’s house was three doors from Bellville Hospital, but the hospital was not equipped to treat the condition. Calls to other hospitals found the same answer: no empty ICU beds. After a 7-hour wait on a stretcher, he was airlifted to a Veterans Affairs hospital in Houston, but it was too late. He died on August 22 at age 46.

Dr. Kakli said, “I’ve never lost a patient with this diagnosis. Ever. I’m scared that the next patient I see is someone that I can’t get to where they need to get to. We are playing musical chairs with 100 people and 10 chairs. When the music stops, what happens?”

Also in Texas in August, Joe Valdez, who was shot six times as an unlucky bystander in a domestic dispute, waited for more than a week for surgery at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, which was over capacity with COVID patients, the Washington Post reported.

Others with chronic diseases fear needing emergency services or even entering a hospital for regular care with the COVID surge.

Nicole Seefeldt, 44, from Easton, Penn., who had a double-lung transplant in 2016, said that she hasn’t been able to see her lung transplant specialists in Philadelphia — an hour-and-a-half drive — for almost 2 years because of fear of contracting COVID. Before the pandemic, she made the trip almost weekly.

“I protect my lungs like they’re children,” she said.

She relies on her local hospital for care, but has put off some needed care, such as a colonoscopy, and has relied on telemedicine because she wants to limit her hospital exposure.

Ms. Seefeldt now faces an eventual kidney transplant, as her kidney function has been reduced to 20%. In the meantime, she worries she will need emergency care for either her lungs or kidneys.

“For those of us who are chronically ill or disabled, what if we have an emergency that is not COVID-related? Are we going to be able to get a bed? Are we going to be able to get treatment? It’s not just COVID patients who come to the [emergency room],” she said.

A pandemic problem

Paul E. Casey, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said that high vaccination rates in Chicago have helped Rush continue to accommodate both non-COVID and COVID patients in the emergency department.

Though the hospital treated a large volume of COVID patients, “The vast majority of people we see and did see through the pandemic were non-COVID patents,” he said.

Dr. Casey said that in the first wave the hospital noticed a concerning drop in patients coming in for strokes and heart attacks — “things we knew hadn’t gone away.”

And the data backs it up. Over the course of the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health Interview Survey found that the percentage of Americans who reported seeing a doctor or health professional fell from 85% at the end of 2019 to about 80% in the first three months of 2021. The survey did not differentiate between in-person visits and telehealth appointments.

Medical practices and patients themselves postponed elective procedures and delayed routine visits during the early months of the crisis.

Patients also reported staying away from hospitals’ emergency departments throughout the pandemic. At the end of 2019, 22% of respondents reported visiting an emergency department in the past year. That dropped to 17% by the end of 2020, and was at 17.7% in the first 3 months of 2021.

Dr. Casey said that, in his hospital’s case, clear messaging became very important to assure patients it was safe to come back. And the message is still critical.

“We want to be loud and clear that patients should continue to seek care for those conditions,” Dr. Casey said. “Deferring healthcare only comes with the long-term sequelae of disease left untreated so we want people to be as proactive in seeking care as they always would be.”

In some cases, fears of entering emergency rooms because of excess patients and risk for infection are keeping some patients from seeking necessary care for minor injuries.

Jim Rickert, MD, an orthopedic surgeon with Indiana University Health in Bloomington, said that some of his patients have expressed fears of coming into the hospital for fractures.

Some patients, particularly elderly patients, he said, are having falls and fractures and wearing slings or braces at home rather than going into the hospital for injuries that need immediate attention.

Bones start healing incorrectly, Dr. Rickert said, and the correction becomes much more difficult.

Plea for vaccinations

Dr. Gosnell made a plea posted on her neighborhood news forum for people to get COVID vaccinations.

“It seems to me it’s easy for other people who are not in bodies like mine to take health for granted,” she said. “But there are a lot of us who live in very fragile bodies and our entire life is at the intersection of us and getting healthcare treatment. Small complications to getting treatment can be life altering.”

Dr. Gosnell, Ms. Seefeldt, Dr. Casey, and Dr. Rickert reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Type 2 diabetes ‘remission’ is a reality, say major organizations

A new joint consensus statement by four major diabetes organizations aims to standardize the terminology, definition, and assessment to the phenomenon of diabetes “remission.”

The statement was jointly issued by the American Diabetes Association, the Endocrine Society, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, and Diabetes UK.

The 12-member international writing panel proposed use of the term “remission,” as opposed to others such as “reversal,” “resolution,” or “cure,” to describe the phenomenon of prolonged normoglycemia without the use of glucose-lowering medication in a person previously diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

“Diabetes remission may be occurring more often due to advances in treatment,” writing group member Amy Rothberg, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in a statement.

The group defined “remission” – whether attained via lifestyle, bariatric surgery, or other means – as an A1c < 6.5% (< 48 mmol/mol) at least 3 months after cessation of glucose-lowering pharmacotherapy. The panel also suggested monitoring individuals experiencing diabetes remission and raised questions that need further attention and study.

But it’s not a guideline, panel chair Matthew C. Riddle, MD, said in an interview. Rather, the “main purpose of the statement was to provide definitions, terminology, cut-points, and timing recommendations to allow data collection that will eventually lead to clinical guidelines,” he said.

A great deal of epidemiological research is conducted by analyzing data from medical records, he noted. “If clinicians are more consistent in entering data into the records and in doing measurements, it will be a better database.”

Remission reality: Advice needed for deprescribing, talking to patients

“Increasingly our treatments are getting glucose levels into the normal range, and in many cases, even after withdrawal of drug therapy. That’s not an anomaly or a fiction, it’s reality. Clinicians need to know how to talk to their patients about it,” noted Dr. Riddle, of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and clinical nutrition at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

There is a need for data on the effects of deprescribing once normoglycemia is achieved, he said. “It really goes a long way to have strong epidemiological and interventional evidence. That’s what we need here, and that’s what the group is really hoping for.”

The statement recommends the following:

- The term “remission” should be used to describe a sustained metabolic improvement in type 2 diabetes to near normal levels. The panel agreed the word strikes the best balance, given that insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction may still be present despite normoglycemia. “Diabetes doesn’t get cured. The underlying abnormalities are still there. Remission is defined by glucose,” Dr. Riddle said. The panel also decided to do away with ADA’s former terms “partial,” “complete,” and “prolonged” remission because they are ambiguous and unhelpful.

- Remission should be defined as a return to an A1c of < 6.5% (< 48 mmol/mol) – the threshold used to diagnose diabetes – spontaneously or following an intervention and that persists for at least 3 months in the absence of usual glucose-lowering medication.

- When A1c may be unreliable, such as conditions involving variant hemoglobin or erythrocyte survival alterations, acceptable alternatives are a fasting blood glucose < 126 mg/dL (< 7.0 mmol/L) or an estimated A1c < 6.5% calculated from continuous glucose monitoring data.

- A1c testing to document a remission should be performed just prior to an intervention and no sooner than 3 months after initiation of the intervention and withdrawal of any glucose-lowering medication.

- Subsequent ongoing A1c testing should be done at least yearly thereafter, along with routine monitoring for diabetes-related complications, including retinal screening, renal function assessment, foot exams, and cardiovascular risk factor testing. “At present, there is no long-term evidence indicating that any of the usually recommended assessments for complications can safely be discontinued,” the authors wrote.

- Research based on the terminology and definitions in the present statement is needed to determine the frequency, duration, and effects on short- and long-term medical outcomes of type 2 diabetes remissions using available interventions.

Dr. Riddle said in an interview: “We thought that the clinical community needed to understand where this issue stands right now. The feasibility of a remission is greater than it used to be.

“We’re going to see more patients who have what we can now call a remission according to a standardized definition. In the future, there are likely to be guidelines regarding the kind of patients and the kind of tactics appropriate for seeking a remission,” he said.

The statement was simultaneously published online in each of the organizations’ respective journals: Diabetes Care, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Diabetologia, and Diabetic Medicine.

Dr. Riddle has reported receiving research grant support through Oregon Health & Science University from Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and AstraZeneca and honoraria for consulting from Adocia, Intercept, and Theracos.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new joint consensus statement by four major diabetes organizations aims to standardize the terminology, definition, and assessment to the phenomenon of diabetes “remission.”

The statement was jointly issued by the American Diabetes Association, the Endocrine Society, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, and Diabetes UK.

The 12-member international writing panel proposed use of the term “remission,” as opposed to others such as “reversal,” “resolution,” or “cure,” to describe the phenomenon of prolonged normoglycemia without the use of glucose-lowering medication in a person previously diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

“Diabetes remission may be occurring more often due to advances in treatment,” writing group member Amy Rothberg, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in a statement.

The group defined “remission” – whether attained via lifestyle, bariatric surgery, or other means – as an A1c < 6.5% (< 48 mmol/mol) at least 3 months after cessation of glucose-lowering pharmacotherapy. The panel also suggested monitoring individuals experiencing diabetes remission and raised questions that need further attention and study.

But it’s not a guideline, panel chair Matthew C. Riddle, MD, said in an interview. Rather, the “main purpose of the statement was to provide definitions, terminology, cut-points, and timing recommendations to allow data collection that will eventually lead to clinical guidelines,” he said.

A great deal of epidemiological research is conducted by analyzing data from medical records, he noted. “If clinicians are more consistent in entering data into the records and in doing measurements, it will be a better database.”

Remission reality: Advice needed for deprescribing, talking to patients

“Increasingly our treatments are getting glucose levels into the normal range, and in many cases, even after withdrawal of drug therapy. That’s not an anomaly or a fiction, it’s reality. Clinicians need to know how to talk to their patients about it,” noted Dr. Riddle, of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and clinical nutrition at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

There is a need for data on the effects of deprescribing once normoglycemia is achieved, he said. “It really goes a long way to have strong epidemiological and interventional evidence. That’s what we need here, and that’s what the group is really hoping for.”

The statement recommends the following:

- The term “remission” should be used to describe a sustained metabolic improvement in type 2 diabetes to near normal levels. The panel agreed the word strikes the best balance, given that insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction may still be present despite normoglycemia. “Diabetes doesn’t get cured. The underlying abnormalities are still there. Remission is defined by glucose,” Dr. Riddle said. The panel also decided to do away with ADA’s former terms “partial,” “complete,” and “prolonged” remission because they are ambiguous and unhelpful.

- Remission should be defined as a return to an A1c of < 6.5% (< 48 mmol/mol) – the threshold used to diagnose diabetes – spontaneously or following an intervention and that persists for at least 3 months in the absence of usual glucose-lowering medication.

- When A1c may be unreliable, such as conditions involving variant hemoglobin or erythrocyte survival alterations, acceptable alternatives are a fasting blood glucose < 126 mg/dL (< 7.0 mmol/L) or an estimated A1c < 6.5% calculated from continuous glucose monitoring data.

- A1c testing to document a remission should be performed just prior to an intervention and no sooner than 3 months after initiation of the intervention and withdrawal of any glucose-lowering medication.

- Subsequent ongoing A1c testing should be done at least yearly thereafter, along with routine monitoring for diabetes-related complications, including retinal screening, renal function assessment, foot exams, and cardiovascular risk factor testing. “At present, there is no long-term evidence indicating that any of the usually recommended assessments for complications can safely be discontinued,” the authors wrote.

- Research based on the terminology and definitions in the present statement is needed to determine the frequency, duration, and effects on short- and long-term medical outcomes of type 2 diabetes remissions using available interventions.

Dr. Riddle said in an interview: “We thought that the clinical community needed to understand where this issue stands right now. The feasibility of a remission is greater than it used to be.

“We’re going to see more patients who have what we can now call a remission according to a standardized definition. In the future, there are likely to be guidelines regarding the kind of patients and the kind of tactics appropriate for seeking a remission,” he said.

The statement was simultaneously published online in each of the organizations’ respective journals: Diabetes Care, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Diabetologia, and Diabetic Medicine.

Dr. Riddle has reported receiving research grant support through Oregon Health & Science University from Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and AstraZeneca and honoraria for consulting from Adocia, Intercept, and Theracos.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new joint consensus statement by four major diabetes organizations aims to standardize the terminology, definition, and assessment to the phenomenon of diabetes “remission.”

The statement was jointly issued by the American Diabetes Association, the Endocrine Society, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, and Diabetes UK.

The 12-member international writing panel proposed use of the term “remission,” as opposed to others such as “reversal,” “resolution,” or “cure,” to describe the phenomenon of prolonged normoglycemia without the use of glucose-lowering medication in a person previously diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

“Diabetes remission may be occurring more often due to advances in treatment,” writing group member Amy Rothberg, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in a statement.

The group defined “remission” – whether attained via lifestyle, bariatric surgery, or other means – as an A1c < 6.5% (< 48 mmol/mol) at least 3 months after cessation of glucose-lowering pharmacotherapy. The panel also suggested monitoring individuals experiencing diabetes remission and raised questions that need further attention and study.

But it’s not a guideline, panel chair Matthew C. Riddle, MD, said in an interview. Rather, the “main purpose of the statement was to provide definitions, terminology, cut-points, and timing recommendations to allow data collection that will eventually lead to clinical guidelines,” he said.

A great deal of epidemiological research is conducted by analyzing data from medical records, he noted. “If clinicians are more consistent in entering data into the records and in doing measurements, it will be a better database.”

Remission reality: Advice needed for deprescribing, talking to patients

“Increasingly our treatments are getting glucose levels into the normal range, and in many cases, even after withdrawal of drug therapy. That’s not an anomaly or a fiction, it’s reality. Clinicians need to know how to talk to their patients about it,” noted Dr. Riddle, of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and clinical nutrition at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

There is a need for data on the effects of deprescribing once normoglycemia is achieved, he said. “It really goes a long way to have strong epidemiological and interventional evidence. That’s what we need here, and that’s what the group is really hoping for.”

The statement recommends the following:

- The term “remission” should be used to describe a sustained metabolic improvement in type 2 diabetes to near normal levels. The panel agreed the word strikes the best balance, given that insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction may still be present despite normoglycemia. “Diabetes doesn’t get cured. The underlying abnormalities are still there. Remission is defined by glucose,” Dr. Riddle said. The panel also decided to do away with ADA’s former terms “partial,” “complete,” and “prolonged” remission because they are ambiguous and unhelpful.

- Remission should be defined as a return to an A1c of < 6.5% (< 48 mmol/mol) – the threshold used to diagnose diabetes – spontaneously or following an intervention and that persists for at least 3 months in the absence of usual glucose-lowering medication.

- When A1c may be unreliable, such as conditions involving variant hemoglobin or erythrocyte survival alterations, acceptable alternatives are a fasting blood glucose < 126 mg/dL (< 7.0 mmol/L) or an estimated A1c < 6.5% calculated from continuous glucose monitoring data.

- A1c testing to document a remission should be performed just prior to an intervention and no sooner than 3 months after initiation of the intervention and withdrawal of any glucose-lowering medication.

- Subsequent ongoing A1c testing should be done at least yearly thereafter, along with routine monitoring for diabetes-related complications, including retinal screening, renal function assessment, foot exams, and cardiovascular risk factor testing. “At present, there is no long-term evidence indicating that any of the usually recommended assessments for complications can safely be discontinued,” the authors wrote.

- Research based on the terminology and definitions in the present statement is needed to determine the frequency, duration, and effects on short- and long-term medical outcomes of type 2 diabetes remissions using available interventions.

Dr. Riddle said in an interview: “We thought that the clinical community needed to understand where this issue stands right now. The feasibility of a remission is greater than it used to be.

“We’re going to see more patients who have what we can now call a remission according to a standardized definition. In the future, there are likely to be guidelines regarding the kind of patients and the kind of tactics appropriate for seeking a remission,” he said.

The statement was simultaneously published online in each of the organizations’ respective journals: Diabetes Care, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Diabetologia, and Diabetic Medicine.

Dr. Riddle has reported receiving research grant support through Oregon Health & Science University from Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and AstraZeneca and honoraria for consulting from Adocia, Intercept, and Theracos.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two swings, two misses with colchicine, Vascepa in COVID-19

The anti-inflammatory agents colchicine and icosapent ethyl (Vascepa; Amarin) failed to provide substantial benefits in separate randomized COVID-19 trials.

Both were reported at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress 2021.

The open-label ECLA PHRI COLCOVID trial randomized 1,277 hospitalized adults (mean age 62 years) to usual care alone or with colchicine at a loading dose of 1.5 mg for 2 hours followed by 0.5 mg on day 1 and then 0.5 mg twice daily for 14 days or until discharge.

The investigators hypothesized that colchicine, which is widely used to treat gout and other inflammatory conditions, might modulate the hyperinflammatory syndrome, or cytokine storm, associated with COVID-19.

Results showed that the need for mechanical ventilation or death occurred in 25.0% of patients receiving colchicine and 28.8% with usual care (P = .08).

The coprimary endpoint of death at 28 days was also not significantly different between groups (20.5% vs. 22.2%), principal investigator Rafael Diaz, MD, said in a late-breaking COVID-19 trials session at the congress.

Among the secondary outcomes at 28 days, colchicine significantly reduced the incidence of new intubation or death from respiratory failure from 27.0% to 22.3% (hazard ratio, 0.79; 95% confidence interval, 0.63-0.99) but not mortality from respiratory failure (19.5% vs. 16.8%).

The only important adverse effect was severe diarrhea, which was reported in 11.3% of the colchicine group vs. 4.5% in the control group, said Dr. Diaz, director of Estudios Clínicos Latinoamérica (ECLA), Rosario, Argentina.

The results are consistent with those from the massive RECOVERY trial, which earlier this year stopped enrollment in the colchicine arm for lack of efficacy in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, and COLCORONA, which missed its primary endpoint using colchicine among nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19.

Session chair and COLCORONA principal investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, pointed out that, as clinicians, it’s fairly uncommon to combine systemic steroids with colchicine, which was the case in 92% of patients in ECLA PHRI COLCOVID.

“I think it is an inherent limitation of testing colchicine on top of steroids,” said Dr. Tardif, of the Montreal Heart Institute.

Icosapent ethyl in PREPARE-IT

Dr. Diaz returned in the ESC session to present the results of the PREPARE-IT trial, which tested whether icosapent ethyl – at a loading dose of 8 grams (4 capsules) for the first 3 days and 4 g/d on days 4-60 – could reduce the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection in 2,041 health care and other public workers in Argentina at high risk for infection (mean age 40.5 years).

Vascepa was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2012 for the reduction of elevated triglyceride levels, with an added indication in 2019 to reduce cardiovascular (CV) events in people with elevated triglycerides and established CV disease or diabetes with other CV risk factors.

The rationale for using the high-dose prescription eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) preparation includes its anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic effects, and that unsaturated fatty acids, especially EPA, might inactivate the enveloped virus, he explained.

Among 1,712 participants followed for up to 60 days, however, the SARS-CoV-2 infection rate was 7.9% with icosapent ethyl vs. 7.1% with a mineral oil placebo (P = .58).

There were also no significant changes from baseline in the icosapent ethyl and placebo groups for the secondary outcomes of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (0 vs. 0), triglycerides (median –2 mg/dL vs. 7 mg/dL), or Influenza Patient-Reported Outcome (FLU-PRO) questionnaire scores (median 0.01 vs. 0.03).

The use of a mineral oil placebo has been the subject of controversy in previous fish oil trials, but, Dr. Diaz noted, it did not have a significant proinflammatory effect or cause any excess adverse events.

Overall, adverse events were similar between the active and placebo groups, including atrial fibrillation (none), major bleeding (none), minor bleeding (7 events vs. 10 events), gastrointestinal symptoms (6.8% vs. 7.0%), and diarrhea (8.6% vs. 7.7%).

Although it missed the primary endpoint, Dr. Diaz said, “this is the first large, randomized blinded trial to demonstrate excellent safety and tolerability of an 8-gram-per-day loading dose of icosapent ethyl, opening up the potential for acute use in randomized trials of myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndromes, strokes, and revascularization.”

During a discussion of the results, Dr. Diaz said the Delta variant was not present at the time of the analysis and that the second half of the trial will report on whether icosapent ethyl can reduce the risk for hospitalization or death in participants diagnosed with COVID-19.

ECLA PHRI COLCOVID was supported by the Estudios Clínicos Latinoamérica Population Health Research Institute. PREPARE-IT was supported by Estudios Clínicos Latinoamérica with collaboration from Amarin. Dr. Diaz reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The anti-inflammatory agents colchicine and icosapent ethyl (Vascepa; Amarin) failed to provide substantial benefits in separate randomized COVID-19 trials.

Both were reported at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress 2021.

The open-label ECLA PHRI COLCOVID trial randomized 1,277 hospitalized adults (mean age 62 years) to usual care alone or with colchicine at a loading dose of 1.5 mg for 2 hours followed by 0.5 mg on day 1 and then 0.5 mg twice daily for 14 days or until discharge.

The investigators hypothesized that colchicine, which is widely used to treat gout and other inflammatory conditions, might modulate the hyperinflammatory syndrome, or cytokine storm, associated with COVID-19.

Results showed that the need for mechanical ventilation or death occurred in 25.0% of patients receiving colchicine and 28.8% with usual care (P = .08).

The coprimary endpoint of death at 28 days was also not significantly different between groups (20.5% vs. 22.2%), principal investigator Rafael Diaz, MD, said in a late-breaking COVID-19 trials session at the congress.

Among the secondary outcomes at 28 days, colchicine significantly reduced the incidence of new intubation or death from respiratory failure from 27.0% to 22.3% (hazard ratio, 0.79; 95% confidence interval, 0.63-0.99) but not mortality from respiratory failure (19.5% vs. 16.8%).

The only important adverse effect was severe diarrhea, which was reported in 11.3% of the colchicine group vs. 4.5% in the control group, said Dr. Diaz, director of Estudios Clínicos Latinoamérica (ECLA), Rosario, Argentina.

The results are consistent with those from the massive RECOVERY trial, which earlier this year stopped enrollment in the colchicine arm for lack of efficacy in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, and COLCORONA, which missed its primary endpoint using colchicine among nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19.

Session chair and COLCORONA principal investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, pointed out that, as clinicians, it’s fairly uncommon to combine systemic steroids with colchicine, which was the case in 92% of patients in ECLA PHRI COLCOVID.

“I think it is an inherent limitation of testing colchicine on top of steroids,” said Dr. Tardif, of the Montreal Heart Institute.

Icosapent ethyl in PREPARE-IT

Dr. Diaz returned in the ESC session to present the results of the PREPARE-IT trial, which tested whether icosapent ethyl – at a loading dose of 8 grams (4 capsules) for the first 3 days and 4 g/d on days 4-60 – could reduce the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection in 2,041 health care and other public workers in Argentina at high risk for infection (mean age 40.5 years).

Vascepa was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2012 for the reduction of elevated triglyceride levels, with an added indication in 2019 to reduce cardiovascular (CV) events in people with elevated triglycerides and established CV disease or diabetes with other CV risk factors.

The rationale for using the high-dose prescription eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) preparation includes its anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic effects, and that unsaturated fatty acids, especially EPA, might inactivate the enveloped virus, he explained.

Among 1,712 participants followed for up to 60 days, however, the SARS-CoV-2 infection rate was 7.9% with icosapent ethyl vs. 7.1% with a mineral oil placebo (P = .58).

There were also no significant changes from baseline in the icosapent ethyl and placebo groups for the secondary outcomes of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (0 vs. 0), triglycerides (median –2 mg/dL vs. 7 mg/dL), or Influenza Patient-Reported Outcome (FLU-PRO) questionnaire scores (median 0.01 vs. 0.03).

The use of a mineral oil placebo has been the subject of controversy in previous fish oil trials, but, Dr. Diaz noted, it did not have a significant proinflammatory effect or cause any excess adverse events.

Overall, adverse events were similar between the active and placebo groups, including atrial fibrillation (none), major bleeding (none), minor bleeding (7 events vs. 10 events), gastrointestinal symptoms (6.8% vs. 7.0%), and diarrhea (8.6% vs. 7.7%).

Although it missed the primary endpoint, Dr. Diaz said, “this is the first large, randomized blinded trial to demonstrate excellent safety and tolerability of an 8-gram-per-day loading dose of icosapent ethyl, opening up the potential for acute use in randomized trials of myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndromes, strokes, and revascularization.”

During a discussion of the results, Dr. Diaz said the Delta variant was not present at the time of the analysis and that the second half of the trial will report on whether icosapent ethyl can reduce the risk for hospitalization or death in participants diagnosed with COVID-19.

ECLA PHRI COLCOVID was supported by the Estudios Clínicos Latinoamérica Population Health Research Institute. PREPARE-IT was supported by Estudios Clínicos Latinoamérica with collaboration from Amarin. Dr. Diaz reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The anti-inflammatory agents colchicine and icosapent ethyl (Vascepa; Amarin) failed to provide substantial benefits in separate randomized COVID-19 trials.

Both were reported at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress 2021.

The open-label ECLA PHRI COLCOVID trial randomized 1,277 hospitalized adults (mean age 62 years) to usual care alone or with colchicine at a loading dose of 1.5 mg for 2 hours followed by 0.5 mg on day 1 and then 0.5 mg twice daily for 14 days or until discharge.

The investigators hypothesized that colchicine, which is widely used to treat gout and other inflammatory conditions, might modulate the hyperinflammatory syndrome, or cytokine storm, associated with COVID-19.

Results showed that the need for mechanical ventilation or death occurred in 25.0% of patients receiving colchicine and 28.8% with usual care (P = .08).

The coprimary endpoint of death at 28 days was also not significantly different between groups (20.5% vs. 22.2%), principal investigator Rafael Diaz, MD, said in a late-breaking COVID-19 trials session at the congress.

Among the secondary outcomes at 28 days, colchicine significantly reduced the incidence of new intubation or death from respiratory failure from 27.0% to 22.3% (hazard ratio, 0.79; 95% confidence interval, 0.63-0.99) but not mortality from respiratory failure (19.5% vs. 16.8%).

The only important adverse effect was severe diarrhea, which was reported in 11.3% of the colchicine group vs. 4.5% in the control group, said Dr. Diaz, director of Estudios Clínicos Latinoamérica (ECLA), Rosario, Argentina.

The results are consistent with those from the massive RECOVERY trial, which earlier this year stopped enrollment in the colchicine arm for lack of efficacy in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, and COLCORONA, which missed its primary endpoint using colchicine among nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19.

Session chair and COLCORONA principal investigator Jean-Claude Tardif, MD, pointed out that, as clinicians, it’s fairly uncommon to combine systemic steroids with colchicine, which was the case in 92% of patients in ECLA PHRI COLCOVID.

“I think it is an inherent limitation of testing colchicine on top of steroids,” said Dr. Tardif, of the Montreal Heart Institute.

Icosapent ethyl in PREPARE-IT

Dr. Diaz returned in the ESC session to present the results of the PREPARE-IT trial, which tested whether icosapent ethyl – at a loading dose of 8 grams (4 capsules) for the first 3 days and 4 g/d on days 4-60 – could reduce the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection in 2,041 health care and other public workers in Argentina at high risk for infection (mean age 40.5 years).

Vascepa was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2012 for the reduction of elevated triglyceride levels, with an added indication in 2019 to reduce cardiovascular (CV) events in people with elevated triglycerides and established CV disease or diabetes with other CV risk factors.

The rationale for using the high-dose prescription eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) preparation includes its anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic effects, and that unsaturated fatty acids, especially EPA, might inactivate the enveloped virus, he explained.

Among 1,712 participants followed for up to 60 days, however, the SARS-CoV-2 infection rate was 7.9% with icosapent ethyl vs. 7.1% with a mineral oil placebo (P = .58).

There were also no significant changes from baseline in the icosapent ethyl and placebo groups for the secondary outcomes of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (0 vs. 0), triglycerides (median –2 mg/dL vs. 7 mg/dL), or Influenza Patient-Reported Outcome (FLU-PRO) questionnaire scores (median 0.01 vs. 0.03).

The use of a mineral oil placebo has been the subject of controversy in previous fish oil trials, but, Dr. Diaz noted, it did not have a significant proinflammatory effect or cause any excess adverse events.

Overall, adverse events were similar between the active and placebo groups, including atrial fibrillation (none), major bleeding (none), minor bleeding (7 events vs. 10 events), gastrointestinal symptoms (6.8% vs. 7.0%), and diarrhea (8.6% vs. 7.7%).

Although it missed the primary endpoint, Dr. Diaz said, “this is the first large, randomized blinded trial to demonstrate excellent safety and tolerability of an 8-gram-per-day loading dose of icosapent ethyl, opening up the potential for acute use in randomized trials of myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndromes, strokes, and revascularization.”

During a discussion of the results, Dr. Diaz said the Delta variant was not present at the time of the analysis and that the second half of the trial will report on whether icosapent ethyl can reduce the risk for hospitalization or death in participants diagnosed with COVID-19.

ECLA PHRI COLCOVID was supported by the Estudios Clínicos Latinoamérica Population Health Research Institute. PREPARE-IT was supported by Estudios Clínicos Latinoamérica with collaboration from Amarin. Dr. Diaz reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘This food will kill you, that food will save you’

Not sure if you’ve heard the news, but eating a single hot dog will apparently cost you 36 minutes of healthy life. My first thought when hearing this was of course the same as everyone else’s: Poor Joey Chestnut, multiyear winner of Nathan’s annual hot dog–eating contest.

He won this year’s contest with 76 hot dogs, which puts his total number of competition-consumed hot dogs at 1,089 – which cost him, it would seem, 27.2 days of healthy life. Unless, of course, every hot dog he inhaled came with a bun hosting two portions of sesame seeds, which in turn would buy him 50 extra minutes of life (25 minutes per portion, you see) and would consequently have extended his life by 10.6 days.

Clearly, the obvious solution here is to ensure that all hot dog buns have two portions of sesame seeds on them moving forward; that way, hot dogs can transition from being poisonous killers to antiaging medicine.

The other solution, albeit less exciting, perhaps, is for researchers to stop studying single foods’ impacts on health, and/or for journals to stop publishing them, and/or for the media to stop promoting them – because they are all as ridiculously useless as the example above highlighting findings from a newly published study in Nature Food, entitled “Small targeted dietary changes can yield substantial gains for human health and the environment.”

While no doubt we would all love for diet and health to be so well understood that we could choose specific single foods (knowing that they would prolong our lives) while avoiding single foods that would shorten it, there’s this unfortunate truth that the degree of confounding among food alone is staggering. People eat thousands of different foods in thousands of different dietary combinations. Moreover, most (all?) research conducted on dietary impacts of single foods on health don’t actually track consumption of those specific foods over time, let alone their interactions with all other foods consumed, but rather at moments in time.

In the case of the “hot dogs will kill you unless there are sesame seeds on your bun” article, for example, the researchers utilized one solitary dietary recall session upon which to base their ridiculously specific, ridiculous conclusions.

People’s diets also change over time for various reasons, and of course people themselves are very different. You might imagine that people whose diets are rich in chicken wings, sugared soda, and hot dogs will have markedly different lifestyles and demographics than those whose diets are rich in walnuts, sashimi, and avocados.

So why do we keep seeing studies like this being published? Is it because they’re basically clickbait catnip for journals and newspapers, and in our publish-or-perish attention-seeking world, that means they not only get a pass but they get a press release? Is it because peer review is broken and everyone knows it? Is it because as a society, we’re frogs who have been steeping for decades in the ever-heated pot of nutritional nonsense, and consequently don’t think to question it?

I don’t know the answer to any of those questions, but one thing I do know: Studies on single foods’ impact on life length are pointless, impossible, and idiotic, and people who share them noncritically should be forever shunned – or at the very least, forever ignored.

Yoni Freedhoff, MD, is an associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa and medical director of the Bariatric Medical Institute, a nonsurgical weight-management center.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Not sure if you’ve heard the news, but eating a single hot dog will apparently cost you 36 minutes of healthy life. My first thought when hearing this was of course the same as everyone else’s: Poor Joey Chestnut, multiyear winner of Nathan’s annual hot dog–eating contest.

He won this year’s contest with 76 hot dogs, which puts his total number of competition-consumed hot dogs at 1,089 – which cost him, it would seem, 27.2 days of healthy life. Unless, of course, every hot dog he inhaled came with a bun hosting two portions of sesame seeds, which in turn would buy him 50 extra minutes of life (25 minutes per portion, you see) and would consequently have extended his life by 10.6 days.

Clearly, the obvious solution here is to ensure that all hot dog buns have two portions of sesame seeds on them moving forward; that way, hot dogs can transition from being poisonous killers to antiaging medicine.

The other solution, albeit less exciting, perhaps, is for researchers to stop studying single foods’ impacts on health, and/or for journals to stop publishing them, and/or for the media to stop promoting them – because they are all as ridiculously useless as the example above highlighting findings from a newly published study in Nature Food, entitled “Small targeted dietary changes can yield substantial gains for human health and the environment.”

While no doubt we would all love for diet and health to be so well understood that we could choose specific single foods (knowing that they would prolong our lives) while avoiding single foods that would shorten it, there’s this unfortunate truth that the degree of confounding among food alone is staggering. People eat thousands of different foods in thousands of different dietary combinations. Moreover, most (all?) research conducted on dietary impacts of single foods on health don’t actually track consumption of those specific foods over time, let alone their interactions with all other foods consumed, but rather at moments in time.

In the case of the “hot dogs will kill you unless there are sesame seeds on your bun” article, for example, the researchers utilized one solitary dietary recall session upon which to base their ridiculously specific, ridiculous conclusions.

People’s diets also change over time for various reasons, and of course people themselves are very different. You might imagine that people whose diets are rich in chicken wings, sugared soda, and hot dogs will have markedly different lifestyles and demographics than those whose diets are rich in walnuts, sashimi, and avocados.

So why do we keep seeing studies like this being published? Is it because they’re basically clickbait catnip for journals and newspapers, and in our publish-or-perish attention-seeking world, that means they not only get a pass but they get a press release? Is it because peer review is broken and everyone knows it? Is it because as a society, we’re frogs who have been steeping for decades in the ever-heated pot of nutritional nonsense, and consequently don’t think to question it?

I don’t know the answer to any of those questions, but one thing I do know: Studies on single foods’ impact on life length are pointless, impossible, and idiotic, and people who share them noncritically should be forever shunned – or at the very least, forever ignored.

Yoni Freedhoff, MD, is an associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa and medical director of the Bariatric Medical Institute, a nonsurgical weight-management center.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Not sure if you’ve heard the news, but eating a single hot dog will apparently cost you 36 minutes of healthy life. My first thought when hearing this was of course the same as everyone else’s: Poor Joey Chestnut, multiyear winner of Nathan’s annual hot dog–eating contest.

He won this year’s contest with 76 hot dogs, which puts his total number of competition-consumed hot dogs at 1,089 – which cost him, it would seem, 27.2 days of healthy life. Unless, of course, every hot dog he inhaled came with a bun hosting two portions of sesame seeds, which in turn would buy him 50 extra minutes of life (25 minutes per portion, you see) and would consequently have extended his life by 10.6 days.

Clearly, the obvious solution here is to ensure that all hot dog buns have two portions of sesame seeds on them moving forward; that way, hot dogs can transition from being poisonous killers to antiaging medicine.

The other solution, albeit less exciting, perhaps, is for researchers to stop studying single foods’ impacts on health, and/or for journals to stop publishing them, and/or for the media to stop promoting them – because they are all as ridiculously useless as the example above highlighting findings from a newly published study in Nature Food, entitled “Small targeted dietary changes can yield substantial gains for human health and the environment.”

While no doubt we would all love for diet and health to be so well understood that we could choose specific single foods (knowing that they would prolong our lives) while avoiding single foods that would shorten it, there’s this unfortunate truth that the degree of confounding among food alone is staggering. People eat thousands of different foods in thousands of different dietary combinations. Moreover, most (all?) research conducted on dietary impacts of single foods on health don’t actually track consumption of those specific foods over time, let alone their interactions with all other foods consumed, but rather at moments in time.

In the case of the “hot dogs will kill you unless there are sesame seeds on your bun” article, for example, the researchers utilized one solitary dietary recall session upon which to base their ridiculously specific, ridiculous conclusions.

People’s diets also change over time for various reasons, and of course people themselves are very different. You might imagine that people whose diets are rich in chicken wings, sugared soda, and hot dogs will have markedly different lifestyles and demographics than those whose diets are rich in walnuts, sashimi, and avocados.

So why do we keep seeing studies like this being published? Is it because they’re basically clickbait catnip for journals and newspapers, and in our publish-or-perish attention-seeking world, that means they not only get a pass but they get a press release? Is it because peer review is broken and everyone knows it? Is it because as a society, we’re frogs who have been steeping for decades in the ever-heated pot of nutritional nonsense, and consequently don’t think to question it?

I don’t know the answer to any of those questions, but one thing I do know: Studies on single foods’ impact on life length are pointless, impossible, and idiotic, and people who share them noncritically should be forever shunned – or at the very least, forever ignored.

Yoni Freedhoff, MD, is an associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa and medical director of the Bariatric Medical Institute, a nonsurgical weight-management center.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

EMPEROR-Preserved spouts torrent of reports on empagliflozin treatment of HFpEF

The featured report from the 6,000-patient EMPEROR-Preserved trial at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology drew lots of attention for its headline finding: the first unequivocal demonstration that a medication, empagliflozin, can significantly reduce the rate of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, a left ventricular ejection fraction of more than 40%), with the details simultaneously published online.

But at the same time, the EMPEROR-Preserved investigators released four additional reports with a lot more outcome analyses that also deserve some attention.

The puzzling neutral effect on renal events

Perhaps the most surprising and complicated set of findings among the main EMPEROR-Preserved outcomes involved renal outcomes.

The trial’s primary outcome was the combined rate of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure (HHF), and the results showed that treatment with empagliflozin (Jardiance) for a median of 26 months on top of standard treatment for patients with HFpEF led to a significant 21% relative risk reduction, compared with placebo-treated patients.

The trial had two prespecified secondary outcomes. One was the total number of HHF, which dropped by a significant 27%, compared with placebo. The second was the mean change in slope of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) on an annualized basis, and the empagliflozin regimen reduced the cumulative annual deficit, compared with placebo by an average of 1.36 mL/min per 1.73 m2, a significant difference.

This preservation of renal function was consistent with results from many prior studies of empagliflozin and all of the other U.S.-approved agents from the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor class. Preservation of renal function and a reduction in renal events has become a hallmark property of all agents in the SGLT2 inhibitor class both in patients with type 2 diabetes, as well as in those without diabetes but with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) or with chronic kidney disease.

EMPEROR-Preserved threw a wrench into what had been an unbroken history of renal protection by SGLT2 inhibitors. That happened when a prespecified endpoint of the study – a composite renal outcome defined as time to first occurrence of chronic dialysis, renal transplantation, a sustained reduction of at least 40% in eGFR, or a sustained drop in eGFR of more than 10 or 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2 from baseline – yielded an unexpected neutral finding.

For this composite renal outcome, EMPEROR-Preserved showed a nonsignificant 5% reduction, compared with placebo, a result that both differed from what had been seen in essentially all the other SGLT2 inhibitor trials that had looked at this, but which also seemed at odds with the observed significant preservation of renal function that seemed substantial enough to produce a clinically meaningful benefit.

Renal effects blunted in HFpEF

The immediate upshot was a letter published by several EMPEROR-Preserved investigators that spelled out this discrepancy and came to the jolting conclusion that “eGFR slope analysis has limitations as a surrogate for predicting the effect of drugs on renal outcomes in patients with heart failure.”

The same authors, along with some additional associates, also published a second letter that noted a further unexpected twist with the renal outcome: “In prior large-scale clinical trials, the effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on heart failure and renal outcomes had consistently tracked together,” they noted, but in this case it didn’t, a discordance they said was “extraordinarily puzzling”.

This led the study’s leaders to reanalyze the renal outcomes using a different definition, one that Milton Packer, MD, who helped design the trial and oversaw several of its analyses, called “a more conventional definition of renal events,” during his presentation of these findings at the congress. The researchers swapped out a 40% drop from baseline eGFR as an event and replaced it with a 50% decline, a change designed to screen out less severe, and often transient, reductions in kidney function that have less lasting impact on health. They also added an additional component to the composite endpoint, renal death. A revised analysis using this new renal composite outcome appeared in the European Journal of Heart Failure letter.

This change cut the total number of renal events tallied in the trial nearly in half, down to 112, and showed a more robust decline in renal events with empagliflozin treatment compared with the initial analysis, although the drop remained nonsignificant. The revised analysis also showed that the overall, nonsignificant 22% relative reduction in renal events in patients on empagliflozin, compared with placebo, dwindled down to completely nonexistent in the tertile of patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 60% or greater. In this tertile the hazard ratio actually showed a nonsignificant point estimate of a 24% increased rate of renal events on empagliflozin, with the caveat that this subgroup now included a total of just 40 total events between the two treatment arms. (Each of the two other tertiles also had roughly the same number of total events.)

The biggest effect on renal-event reduction was in the tertile of patients with an ejection fraction of 41%-49%, in which empagliflozin treatment was linked with a significant 59% cut in renal events, compared with placebo. The analysis also showed significant heterogeneity in thus outcome between this subgroup and the other two tertiles that had higher ejection fractions and showed reduced rates of protection by empagliflozin against renal events.

This apparent blunting of a renal effect despite preservation of renal function seemed to mimic the blunting of the primary cardiovascular outcome effect that also appeared in patients with ejection fractions in the 60%-65% range or above.

“If we knew what blunted the effect of empagliflozin on heart failure outcomes at higher ejection fraction levels, we think the same explanation may also apply to the blunting of effect on renal outcomes, but right now we do not know the answer to either question,” Dr. Packer said in an interview. He’s suggested that one possibility is that many of the enrolled patients identified as having HFpEF, but with these high ejection fractions may have not actually had HFpEF, and their signs and symptoms may have instead resulted from atrial fibrillation.

“Many patients with an ejection fraction of 60%-65% and above had atrial fibrillation,” he noted, with a prevalence at enrollment in this subgroup of about 50%. Atrial fibrillation can cause dyspnea, a hallmark symptom leading to diagnosis of heart failure, and it also increases levels of N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide, a metric that served as a gatekeeper for entry into the trial. “Essentially, we are saying that many of the criteria that we specified to ensure that patients had heart failure probably did not work very well in patients with an ejection fraction of 65% or greater,” said Dr. Packer, a cardiologist at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas. “We need to figure out who these patients are.”

Some experts not involved with the study voiced skepticism that the renal findings reflected a real issue.

“I’m quite optimistic that in the long-term the effect on eGFR will translate into renal protection,” said Rudolf A. de Boer, MD, PhD, a professor of translational cardiology at University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands), and designated discussant at the congress for the presentation by Dr. Packer.

John J.V. McMurray, MD, a professor of cardiology and a heart failure specialist at Glasgow University, speculated that the unexpected renal outcomes data may relate to the initial decline in renal function produced by treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors despite their longer-term enhancement of renal protection.

“If you use a treatment that protects the kidneys in the long-term but causes an initial dip in eGFR, more patients receiving that treatment will have an early ‘event,’ ” he noted in an interview. He also cautioned about the dangers of subgroup analyses that dice the study population into small cohorts.

“Trials are powered to look at the effect of treatment in the overall population. Everything else is exploratory, underpowered, and subject to the play of chance,” Dr. McMurray stressed.

Counting additional cardiovascular disease events allows more analyses

A third auxiliary report from the EMPEROR-Preserved investigators performed several prespecified analyses that depended on adding additional cardiovascular disease endpoints to the core tallies of cardiovascular death or HHF – such as emergent, urgent, and outpatient events that reflected worsening heart failure – and also included information on diuretic and vasopressor use because of worsening heart failure. The increased event numbers allowed the researchers to perform 30 additional analyses included in this report, according to the count kept by Dr. Packer who was the lead author.

He highlighted several of the additional results in this paper that documented benefits from empagliflozin treatment, compared with placebo:

- A significant 29% reduction in the need for admission to a cardiac care unit or intensive care unit during an HHF.

- A nonsignificant 33% reduction in the need for intravenous vasopressors or positive inotropic drugs during HHF.

- A significantly increased rate of patients achieving a higher New York Heart Association functional class. For example, after the first year of treatment patients who received empagliflozin had a 37% higher rate of functional class improvement, compared with patients who received placebo.

Dr. McMurray had his own list of key takeaways from this paper, including:

- Among patients who needed hospitalization, “those treated with empagliflozin were less sick than those in the placebo group.”

- In addition to reducing HHF empagliflozin treatment also reduced episodes of outpatient worsening as reflected by their receipt of intensified diuretic treatment, which occurred a significant 27% less often, compared with patients on placebo.

- Treatment with empagliflozin also linked with a significant 39% relative reduction in emergency or urgent-care visits that required intravenous therapy.

Empagliflozin’s performance relative to sacubitril/valsartan

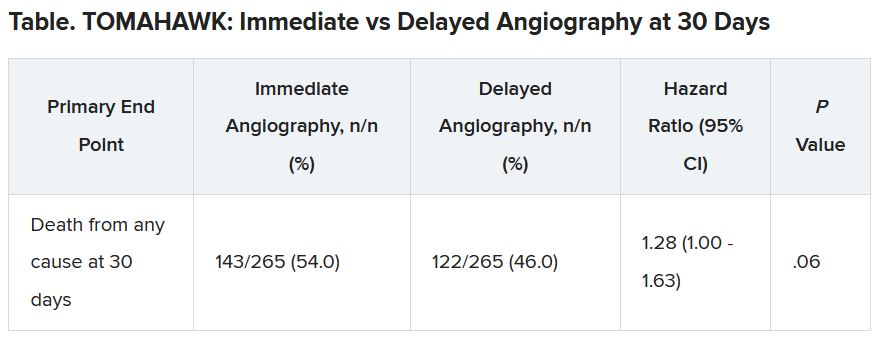

The fourth additional report focused on a post hoc, cross-trial comparison of the results from EMPEROR-Preserved and from another recent trial that, like EMPEROR-Preserved, assessed in patients with HFpEF a drug previously proven to work quite well in patients with HFrEF. The comparator drug was sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto), which underwent testing in patients with HFpEF in the PARAGON-HF trial.

The primary outcome of PARAGON-HF, which randomized 4,822 patients, was reduction in cardiovascular death and in total HHF. This dropped by a relative 13%, compared with placebo, during a median of 35 months, a between-group difference that came close to but did not achieve significance (P = .06). Despite this limitation, the Food and Drug Administration in February 2021 loosened the indication for using sacubitril/valsartan in patients with heart failure and a “below normal” ejection fraction, a category that can include many patients considered to have HFpEF.

Although the researchers who ran this analysis, including Dr. Packer, who was the first author, admitted that “comparison of effect sizes across trials is fraught with difficulties,” they nonetheless concluded from their analysis that “for all outcomes that included HHF the effect size was larger for empagliflozin than for sacubitril/valsartan.”

Dr. McMurray, a lead instigator for PARAGON-HF, said there was little to take away from this analysis.

“The patient populations were different, and sacubitril/valsartan was compared against an active therapy, valsartan,” while in EMPEROR-Preserved empagliflozin compared against placebo. “Most of us believe that sacubitril/valsartan and SGLT2 inhibitors work in different but complementary ways, and their benefits are additive. You would want patients with HFpEF or HFrEF to take both,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Packer agreed with that approach and added that he would probably also prescribe a third agent, spironolactone, to many patients with HFpEF.