User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

Social determinants of health may drive CVD risk in Black Americans

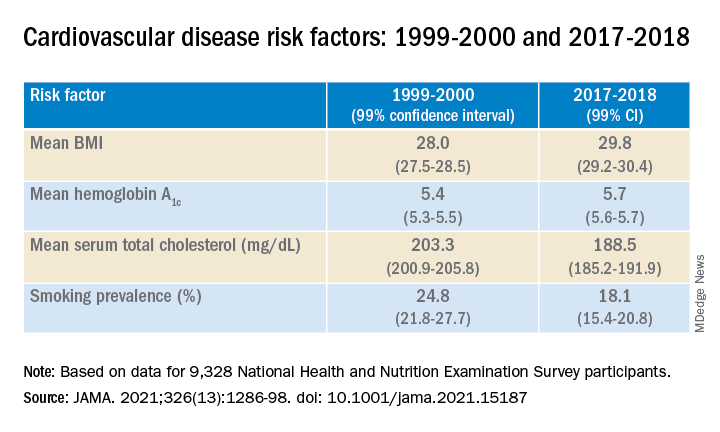

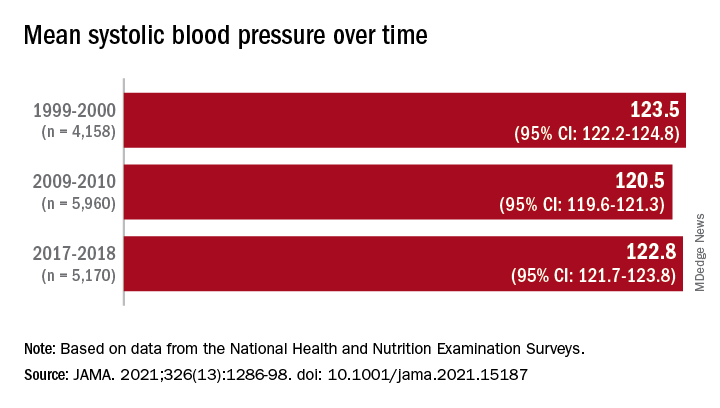

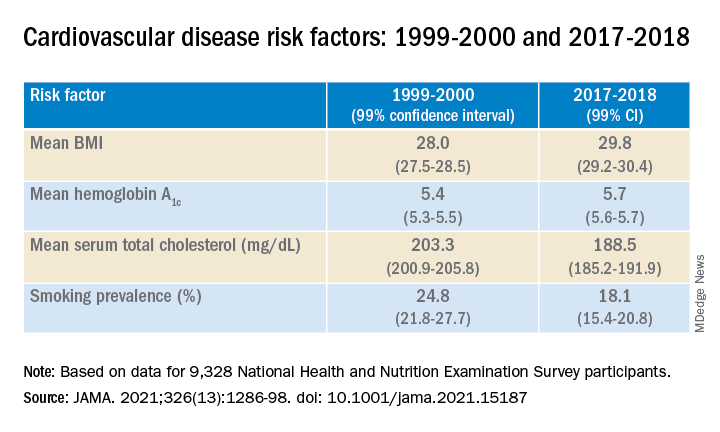

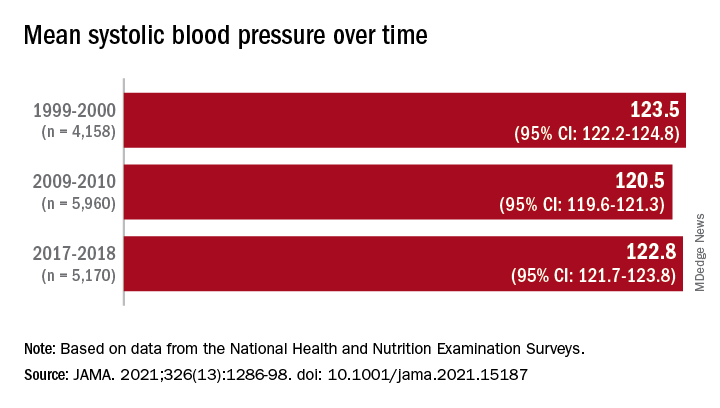

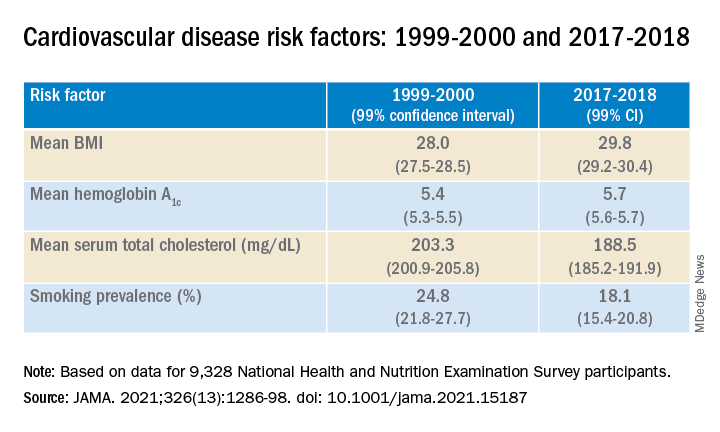

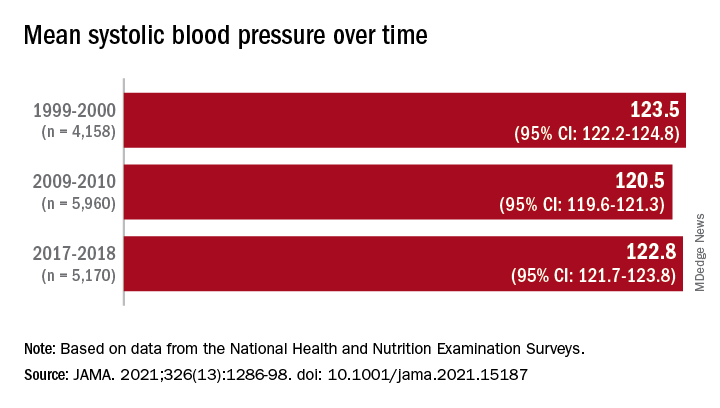

Investigators analyzed 20 years of data on over 50,500 U.S. adults drawn from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) and found that, in the overall population, body mass index and hemoglobin A1c were significantly increased between 1999 and 2018, while serum total cholesterol and cigarette smoking were significantly decreased. Mean systolic blood pressure decreased between 1999 and 2010, but then increased after 2010.

The mean age- and sex-adjusted estimated 10-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) was consistently higher in Black participants vs. White participants, but the difference was attenuated after further adjusting for education, income, home ownership, employment, health insurance, and access to health care.

“These findings are helpful to guide the development of national public health policies for targeted interventions aimed at eliminating health disparities,” Jiang He, MD, PhD, Joseph S. Copes Chair and professor of epidemiology, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, said in an interview.

“Interventions on social determinants of cardiovascular health should be tested in rigorous designed intervention trials,” said Dr. He, director of the Tulane University Translational Science Institute.

The study was published online Oct. 5 in JAMA.

‘Flattened’ CVD mortality?

Recent data show that the CVD mortality rate flattened, while the total number of cardiovascular deaths increased in the U.S. general population from 2010 to 2018, “but the reasons for this deceleration in the decline of CVD mortality are not entirely understood,” Dr. He said.

Moreover, “racial and ethnic differences in CVD mortality persist in the U.S. general population [but] the secular trends of cardiovascular risk factors among U.S. subpopulations with various racial and ethnic backgrounds and socioeconomic status are [also] not well understood,” he added. The effects of social determinants of health, such as education, income, home ownership, employment, health insurance, and access to health care on racial/ethnic differences in CVD risk, “are not well documented.”

To investigate these questions, the researchers drew on data from NHANES, a series of cross-sectional surveys in nationally representative samples of the U.S. population aged 20 years and older. The surveys are conducted in 2-year cycles and include data from 10 cycles conducted from 1999-2000 to 2017-2018 (n = 50,571, mean age 49.0-51.8 years; 48.2%-51.3% female).

Every 2 years, participants provided sociodemographic information, including age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, income, employment, housing, health insurance, and access to health care, as well as medical history and medication use. They underwent a physical examination that included weight and height, blood pressure, lipid levels, plasma glucose, and hemoglobin A1c.

Social determinants of health

Between 1999-2000 and 2017-2018, age- and sex-adjusted mean BMI and hemoglobin A1c increased, while mean serum total cholesterol and prevalence of smoking decreased (all P < .001).

Age- and sex-adjusted 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk decreased from 7.6% (6.9%-8.2%) in 1999-2000 to 6.5% (6.1%-6.8%) in 2011-2012, with no significant changes thereafter.

When the researchers looked at specific racial and ethnic groups, they found that age- and sex-adjusted BMI, systolic BP, and hemoglobin A1c were “consistently higher” in non-Hispanic Black participants compared with non-Hispanic White participants, but total cholesterol was lower (all P < .001).

Participants with at least a college education or high family income had “consistently lower levels” of cardiovascular risk factors. And although the mean age- and sex-adjusted 10-year risk for ASCVD was significantly higher in non-Hispanic Black vs. non-Hispanic White participants (difference, 1.4% [1.0%-1.7%] in 1999-2008 and 2.0% [1.7%-2.4%] in 2009-2018), the difference was attenuated (by –0.3% in 1999-2008 and 0.7% in 2009-2018) after the researchers further adjusted for education, income, home ownership, employment, health insurance, and access to health care.

The differences in cardiovascular risk factors between Black and White participants “may have been moderated by social determinants of health,” the authors noted.

Provide appropriate education

Commenting on the study in an interview, Mary Ann McLaughlin, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine, cardiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, pointed out that two important cardiovascular risk factors associated with being overweight – hypertension and diabetes – remained higher in the Black population compared with the White population in this analysis.

“Physicians and health care systems should provide appropriate education and resources regarding risk factor modification regarding diet, exercise, and blood pressure control,” advised Dr. McLaughlin, who was not involved with the study.

“Importantly, smoking rates and cholesterol levels are lower in the Black population, compared to the White population, when adjusted for many important socioeconomic factors,” she pointed out.

Dr. McLaughlin added that other “important social determinants of health, such as neighborhood and access to healthy food, were not measured and should be addressed by physicians when optimizing cardiovascular risk.”

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. One of the researchers, Joshua D. Bundy, PhD, was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. He and the other coauthors and Dr. McLaughlin reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed 20 years of data on over 50,500 U.S. adults drawn from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) and found that, in the overall population, body mass index and hemoglobin A1c were significantly increased between 1999 and 2018, while serum total cholesterol and cigarette smoking were significantly decreased. Mean systolic blood pressure decreased between 1999 and 2010, but then increased after 2010.

The mean age- and sex-adjusted estimated 10-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) was consistently higher in Black participants vs. White participants, but the difference was attenuated after further adjusting for education, income, home ownership, employment, health insurance, and access to health care.

“These findings are helpful to guide the development of national public health policies for targeted interventions aimed at eliminating health disparities,” Jiang He, MD, PhD, Joseph S. Copes Chair and professor of epidemiology, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, said in an interview.

“Interventions on social determinants of cardiovascular health should be tested in rigorous designed intervention trials,” said Dr. He, director of the Tulane University Translational Science Institute.

The study was published online Oct. 5 in JAMA.

‘Flattened’ CVD mortality?

Recent data show that the CVD mortality rate flattened, while the total number of cardiovascular deaths increased in the U.S. general population from 2010 to 2018, “but the reasons for this deceleration in the decline of CVD mortality are not entirely understood,” Dr. He said.

Moreover, “racial and ethnic differences in CVD mortality persist in the U.S. general population [but] the secular trends of cardiovascular risk factors among U.S. subpopulations with various racial and ethnic backgrounds and socioeconomic status are [also] not well understood,” he added. The effects of social determinants of health, such as education, income, home ownership, employment, health insurance, and access to health care on racial/ethnic differences in CVD risk, “are not well documented.”

To investigate these questions, the researchers drew on data from NHANES, a series of cross-sectional surveys in nationally representative samples of the U.S. population aged 20 years and older. The surveys are conducted in 2-year cycles and include data from 10 cycles conducted from 1999-2000 to 2017-2018 (n = 50,571, mean age 49.0-51.8 years; 48.2%-51.3% female).

Every 2 years, participants provided sociodemographic information, including age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, income, employment, housing, health insurance, and access to health care, as well as medical history and medication use. They underwent a physical examination that included weight and height, blood pressure, lipid levels, plasma glucose, and hemoglobin A1c.

Social determinants of health

Between 1999-2000 and 2017-2018, age- and sex-adjusted mean BMI and hemoglobin A1c increased, while mean serum total cholesterol and prevalence of smoking decreased (all P < .001).

Age- and sex-adjusted 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk decreased from 7.6% (6.9%-8.2%) in 1999-2000 to 6.5% (6.1%-6.8%) in 2011-2012, with no significant changes thereafter.

When the researchers looked at specific racial and ethnic groups, they found that age- and sex-adjusted BMI, systolic BP, and hemoglobin A1c were “consistently higher” in non-Hispanic Black participants compared with non-Hispanic White participants, but total cholesterol was lower (all P < .001).

Participants with at least a college education or high family income had “consistently lower levels” of cardiovascular risk factors. And although the mean age- and sex-adjusted 10-year risk for ASCVD was significantly higher in non-Hispanic Black vs. non-Hispanic White participants (difference, 1.4% [1.0%-1.7%] in 1999-2008 and 2.0% [1.7%-2.4%] in 2009-2018), the difference was attenuated (by –0.3% in 1999-2008 and 0.7% in 2009-2018) after the researchers further adjusted for education, income, home ownership, employment, health insurance, and access to health care.

The differences in cardiovascular risk factors between Black and White participants “may have been moderated by social determinants of health,” the authors noted.

Provide appropriate education

Commenting on the study in an interview, Mary Ann McLaughlin, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine, cardiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, pointed out that two important cardiovascular risk factors associated with being overweight – hypertension and diabetes – remained higher in the Black population compared with the White population in this analysis.

“Physicians and health care systems should provide appropriate education and resources regarding risk factor modification regarding diet, exercise, and blood pressure control,” advised Dr. McLaughlin, who was not involved with the study.

“Importantly, smoking rates and cholesterol levels are lower in the Black population, compared to the White population, when adjusted for many important socioeconomic factors,” she pointed out.

Dr. McLaughlin added that other “important social determinants of health, such as neighborhood and access to healthy food, were not measured and should be addressed by physicians when optimizing cardiovascular risk.”

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. One of the researchers, Joshua D. Bundy, PhD, was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. He and the other coauthors and Dr. McLaughlin reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed 20 years of data on over 50,500 U.S. adults drawn from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) and found that, in the overall population, body mass index and hemoglobin A1c were significantly increased between 1999 and 2018, while serum total cholesterol and cigarette smoking were significantly decreased. Mean systolic blood pressure decreased between 1999 and 2010, but then increased after 2010.

The mean age- and sex-adjusted estimated 10-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) was consistently higher in Black participants vs. White participants, but the difference was attenuated after further adjusting for education, income, home ownership, employment, health insurance, and access to health care.

“These findings are helpful to guide the development of national public health policies for targeted interventions aimed at eliminating health disparities,” Jiang He, MD, PhD, Joseph S. Copes Chair and professor of epidemiology, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, said in an interview.

“Interventions on social determinants of cardiovascular health should be tested in rigorous designed intervention trials,” said Dr. He, director of the Tulane University Translational Science Institute.

The study was published online Oct. 5 in JAMA.

‘Flattened’ CVD mortality?

Recent data show that the CVD mortality rate flattened, while the total number of cardiovascular deaths increased in the U.S. general population from 2010 to 2018, “but the reasons for this deceleration in the decline of CVD mortality are not entirely understood,” Dr. He said.

Moreover, “racial and ethnic differences in CVD mortality persist in the U.S. general population [but] the secular trends of cardiovascular risk factors among U.S. subpopulations with various racial and ethnic backgrounds and socioeconomic status are [also] not well understood,” he added. The effects of social determinants of health, such as education, income, home ownership, employment, health insurance, and access to health care on racial/ethnic differences in CVD risk, “are not well documented.”

To investigate these questions, the researchers drew on data from NHANES, a series of cross-sectional surveys in nationally representative samples of the U.S. population aged 20 years and older. The surveys are conducted in 2-year cycles and include data from 10 cycles conducted from 1999-2000 to 2017-2018 (n = 50,571, mean age 49.0-51.8 years; 48.2%-51.3% female).

Every 2 years, participants provided sociodemographic information, including age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, income, employment, housing, health insurance, and access to health care, as well as medical history and medication use. They underwent a physical examination that included weight and height, blood pressure, lipid levels, plasma glucose, and hemoglobin A1c.

Social determinants of health

Between 1999-2000 and 2017-2018, age- and sex-adjusted mean BMI and hemoglobin A1c increased, while mean serum total cholesterol and prevalence of smoking decreased (all P < .001).

Age- and sex-adjusted 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk decreased from 7.6% (6.9%-8.2%) in 1999-2000 to 6.5% (6.1%-6.8%) in 2011-2012, with no significant changes thereafter.

When the researchers looked at specific racial and ethnic groups, they found that age- and sex-adjusted BMI, systolic BP, and hemoglobin A1c were “consistently higher” in non-Hispanic Black participants compared with non-Hispanic White participants, but total cholesterol was lower (all P < .001).

Participants with at least a college education or high family income had “consistently lower levels” of cardiovascular risk factors. And although the mean age- and sex-adjusted 10-year risk for ASCVD was significantly higher in non-Hispanic Black vs. non-Hispanic White participants (difference, 1.4% [1.0%-1.7%] in 1999-2008 and 2.0% [1.7%-2.4%] in 2009-2018), the difference was attenuated (by –0.3% in 1999-2008 and 0.7% in 2009-2018) after the researchers further adjusted for education, income, home ownership, employment, health insurance, and access to health care.

The differences in cardiovascular risk factors between Black and White participants “may have been moderated by social determinants of health,” the authors noted.

Provide appropriate education

Commenting on the study in an interview, Mary Ann McLaughlin, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine, cardiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, pointed out that two important cardiovascular risk factors associated with being overweight – hypertension and diabetes – remained higher in the Black population compared with the White population in this analysis.

“Physicians and health care systems should provide appropriate education and resources regarding risk factor modification regarding diet, exercise, and blood pressure control,” advised Dr. McLaughlin, who was not involved with the study.

“Importantly, smoking rates and cholesterol levels are lower in the Black population, compared to the White population, when adjusted for many important socioeconomic factors,” she pointed out.

Dr. McLaughlin added that other “important social determinants of health, such as neighborhood and access to healthy food, were not measured and should be addressed by physicians when optimizing cardiovascular risk.”

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. One of the researchers, Joshua D. Bundy, PhD, was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. He and the other coauthors and Dr. McLaughlin reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antithrombotic therapy not warranted in COVID-19 outpatients

Antithrombotic therapy in clinically stable, nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients does not offer protection against adverse cardiovascular or pulmonary events, new randomized clinical trial results suggest.

Antithrombotic therapy has proven useful in acutely ill inpatients with COVID-19, but in this study, treatment with aspirin or apixaban (Eliquis) did not reduce the rate of all-cause mortality, symptomatic venous or arterial thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, or hospitalization for cardiovascular or pulmonary causes in patients ill with COVID-19 but who were not hospitalized.

“Among symptomatic, clinically stable outpatients with COVID-19, treatment with aspirin or apixaban compared with placebo did not reduce the rate of a composite clinical outcome,” the authors conclude. “However, the study was terminated after enrollment of 9% of participants because of a primary event rate lower than anticipated.”

The study, which was led by Jean M. Connors, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, was published online October 11 in JAMA.

The ACTIV-4B Outpatient Thrombosis Prevention Trial was a randomized, adaptive, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that sought to compare anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy among 7,000 symptomatic but clinically stable outpatients with COVID-19.

The trial was conducted at 52 sites in the U.S. between Sept. 2020 and June 2021, with final follow-up this past August 5, and involved minimal face-to-face interactions with study participants.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to aspirin (81 mg orally once daily; n = 164 patients), prophylactic-dose apixaban (2.5 mg orally twice daily; n = 165), therapeutic-dose apixaban (5 mg orally twice daily; n = 164), or placebo (n = 164) for 45 days.

The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause mortality, symptomatic venous or arterial thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, or hospitalization for cardiovascular or pulmonary cause.

The trial was terminated early this past June by the independent data monitoring committee because of lower than anticipated event rates. At the time, just 657 symptomatic outpatients with COVID-19 had been enrolled.

The median age of the study participants was 54 years (Interquartile Range [IQR] 46-59); 59% were women.

The median time from diagnosis to randomization was 7 days, and the median time from randomization to initiation of study medications was 3 days.

The trial’s primary efficacy and safety analyses were restricted to patients who received at least one dose of trial medication, for a final number of 558 patients.

Among these patients, the primary endpoint occurred in 1 patient (0.7%) in the aspirin group, 1 patient (0.7%) in the 2.5 mg apixaban group, 2 patients (1.4%) in the 5-mg apixaban group, and 1 patient (0.7%) in the placebo group.

The researchers found that the absolute risk reductions compared with placebo for the primary outcome were 0.0% (95% confidence interval not calculable) in the aspirin group, 0.7% (95% confidence interval, -2.1% to 4.1%) in the prophylactic-dose apixaban group, and 1.4% (95% CI, -1.5% to 5%) in the therapeutic-dose apixaban group.

No major bleeding events were reported.

The absolute risk differences compared with placebo for clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding events were 2% (95% CI, -2.7% to 6.8%) in the aspirin group, 4.5% (95% CI, -0.7% to 10.2%) in the prophylactic-dose apixaban group, and 6.9% (95% CI, 1.4% to 12.9%) in the therapeutic-dose apixaban group.

Safety and efficacy results were similar in all randomly assigned patients.

The researchers speculated that a combination of two demographic shifts over time may have led to the lower than anticipated rate of events in ACTIV-4B.

“First, the threshold for hospital admission has markedly declined since the beginning of the pandemic, such that hospitalization is no longer limited almost exclusively to those with severe pulmonary distress likely to require mechanical ventilation,” they write. “As a result, the severity of illness among individuals with COVID-19 and destined for outpatient care has declined.”

“Second, at least within the U.S., where the trial was conducted, individuals currently being infected with SARS-CoV-2 tend to be younger and have fewer comorbidities when compared with individuals with incident infection at the onset of the pandemic,” they add.

Further, COVID-19 testing was quite limited early in the pandemic, they note, “and it is possible that the anticipated event rates based on data from registries available at that time were overestimated because the denominator (that is, the number of infected individuals overall) was essentially unknown.”

Robust evidence

“The ACTIV-4B trial is the first randomized trial to generate robust evidence about the effects of antithrombotic therapy in outpatients with COVID-19,” Otavio Berwanger, MD, PhD, director of the Academic Research Organization, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, Sao Paulo-SP, Brazil, told this news organization.

“It should be noted that this was a well-designed trial with low risk of bias. On the other hand, the main limitation is the low number of events and, consequently, the limited statistical power,” said Dr. Berwanger, who wrote an accompanying editorial.

The ACTIV-4B trial has immediate implications for clinical practice, he added.

“In this sense, considering the neutral results for major cardiopulmonary outcomes, the use of aspirin or apixaban for the management of outpatients with COVID-19 should not be recommended.”

ACTIV-4B also provides useful information for the steering committees of other ongoing trials of antithrombotic therapy for patients with COVID-19 who are not hospitalized, Dr. Berwanger added.

“In this sense, probably issues like statistical power, outcome choices, recruitment feasibility, and even futility would need to be revisited. And finally, lessons learned from the implementation of an innovative, pragmatic, and decentralized trial design represent an important legacy for future trials in cardiovascular diseases and other common conditions,” he said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Connors reports financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Abbott, Alnylam, Takeda, Roche, and Sanofi. Dr. Berwanger reports financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Amgen, Servier, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer, Novartis, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antithrombotic therapy in clinically stable, nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients does not offer protection against adverse cardiovascular or pulmonary events, new randomized clinical trial results suggest.

Antithrombotic therapy has proven useful in acutely ill inpatients with COVID-19, but in this study, treatment with aspirin or apixaban (Eliquis) did not reduce the rate of all-cause mortality, symptomatic venous or arterial thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, or hospitalization for cardiovascular or pulmonary causes in patients ill with COVID-19 but who were not hospitalized.

“Among symptomatic, clinically stable outpatients with COVID-19, treatment with aspirin or apixaban compared with placebo did not reduce the rate of a composite clinical outcome,” the authors conclude. “However, the study was terminated after enrollment of 9% of participants because of a primary event rate lower than anticipated.”

The study, which was led by Jean M. Connors, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, was published online October 11 in JAMA.

The ACTIV-4B Outpatient Thrombosis Prevention Trial was a randomized, adaptive, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that sought to compare anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy among 7,000 symptomatic but clinically stable outpatients with COVID-19.

The trial was conducted at 52 sites in the U.S. between Sept. 2020 and June 2021, with final follow-up this past August 5, and involved minimal face-to-face interactions with study participants.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to aspirin (81 mg orally once daily; n = 164 patients), prophylactic-dose apixaban (2.5 mg orally twice daily; n = 165), therapeutic-dose apixaban (5 mg orally twice daily; n = 164), or placebo (n = 164) for 45 days.

The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause mortality, symptomatic venous or arterial thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, or hospitalization for cardiovascular or pulmonary cause.

The trial was terminated early this past June by the independent data monitoring committee because of lower than anticipated event rates. At the time, just 657 symptomatic outpatients with COVID-19 had been enrolled.

The median age of the study participants was 54 years (Interquartile Range [IQR] 46-59); 59% were women.

The median time from diagnosis to randomization was 7 days, and the median time from randomization to initiation of study medications was 3 days.

The trial’s primary efficacy and safety analyses were restricted to patients who received at least one dose of trial medication, for a final number of 558 patients.

Among these patients, the primary endpoint occurred in 1 patient (0.7%) in the aspirin group, 1 patient (0.7%) in the 2.5 mg apixaban group, 2 patients (1.4%) in the 5-mg apixaban group, and 1 patient (0.7%) in the placebo group.

The researchers found that the absolute risk reductions compared with placebo for the primary outcome were 0.0% (95% confidence interval not calculable) in the aspirin group, 0.7% (95% confidence interval, -2.1% to 4.1%) in the prophylactic-dose apixaban group, and 1.4% (95% CI, -1.5% to 5%) in the therapeutic-dose apixaban group.

No major bleeding events were reported.

The absolute risk differences compared with placebo for clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding events were 2% (95% CI, -2.7% to 6.8%) in the aspirin group, 4.5% (95% CI, -0.7% to 10.2%) in the prophylactic-dose apixaban group, and 6.9% (95% CI, 1.4% to 12.9%) in the therapeutic-dose apixaban group.

Safety and efficacy results were similar in all randomly assigned patients.

The researchers speculated that a combination of two demographic shifts over time may have led to the lower than anticipated rate of events in ACTIV-4B.

“First, the threshold for hospital admission has markedly declined since the beginning of the pandemic, such that hospitalization is no longer limited almost exclusively to those with severe pulmonary distress likely to require mechanical ventilation,” they write. “As a result, the severity of illness among individuals with COVID-19 and destined for outpatient care has declined.”

“Second, at least within the U.S., where the trial was conducted, individuals currently being infected with SARS-CoV-2 tend to be younger and have fewer comorbidities when compared with individuals with incident infection at the onset of the pandemic,” they add.

Further, COVID-19 testing was quite limited early in the pandemic, they note, “and it is possible that the anticipated event rates based on data from registries available at that time were overestimated because the denominator (that is, the number of infected individuals overall) was essentially unknown.”

Robust evidence

“The ACTIV-4B trial is the first randomized trial to generate robust evidence about the effects of antithrombotic therapy in outpatients with COVID-19,” Otavio Berwanger, MD, PhD, director of the Academic Research Organization, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, Sao Paulo-SP, Brazil, told this news organization.

“It should be noted that this was a well-designed trial with low risk of bias. On the other hand, the main limitation is the low number of events and, consequently, the limited statistical power,” said Dr. Berwanger, who wrote an accompanying editorial.

The ACTIV-4B trial has immediate implications for clinical practice, he added.

“In this sense, considering the neutral results for major cardiopulmonary outcomes, the use of aspirin or apixaban for the management of outpatients with COVID-19 should not be recommended.”

ACTIV-4B also provides useful information for the steering committees of other ongoing trials of antithrombotic therapy for patients with COVID-19 who are not hospitalized, Dr. Berwanger added.

“In this sense, probably issues like statistical power, outcome choices, recruitment feasibility, and even futility would need to be revisited. And finally, lessons learned from the implementation of an innovative, pragmatic, and decentralized trial design represent an important legacy for future trials in cardiovascular diseases and other common conditions,” he said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Connors reports financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Abbott, Alnylam, Takeda, Roche, and Sanofi. Dr. Berwanger reports financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Amgen, Servier, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer, Novartis, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antithrombotic therapy in clinically stable, nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients does not offer protection against adverse cardiovascular or pulmonary events, new randomized clinical trial results suggest.

Antithrombotic therapy has proven useful in acutely ill inpatients with COVID-19, but in this study, treatment with aspirin or apixaban (Eliquis) did not reduce the rate of all-cause mortality, symptomatic venous or arterial thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, or hospitalization for cardiovascular or pulmonary causes in patients ill with COVID-19 but who were not hospitalized.

“Among symptomatic, clinically stable outpatients with COVID-19, treatment with aspirin or apixaban compared with placebo did not reduce the rate of a composite clinical outcome,” the authors conclude. “However, the study was terminated after enrollment of 9% of participants because of a primary event rate lower than anticipated.”

The study, which was led by Jean M. Connors, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, was published online October 11 in JAMA.

The ACTIV-4B Outpatient Thrombosis Prevention Trial was a randomized, adaptive, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that sought to compare anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy among 7,000 symptomatic but clinically stable outpatients with COVID-19.

The trial was conducted at 52 sites in the U.S. between Sept. 2020 and June 2021, with final follow-up this past August 5, and involved minimal face-to-face interactions with study participants.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to aspirin (81 mg orally once daily; n = 164 patients), prophylactic-dose apixaban (2.5 mg orally twice daily; n = 165), therapeutic-dose apixaban (5 mg orally twice daily; n = 164), or placebo (n = 164) for 45 days.

The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause mortality, symptomatic venous or arterial thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, or hospitalization for cardiovascular or pulmonary cause.

The trial was terminated early this past June by the independent data monitoring committee because of lower than anticipated event rates. At the time, just 657 symptomatic outpatients with COVID-19 had been enrolled.

The median age of the study participants was 54 years (Interquartile Range [IQR] 46-59); 59% were women.

The median time from diagnosis to randomization was 7 days, and the median time from randomization to initiation of study medications was 3 days.

The trial’s primary efficacy and safety analyses were restricted to patients who received at least one dose of trial medication, for a final number of 558 patients.

Among these patients, the primary endpoint occurred in 1 patient (0.7%) in the aspirin group, 1 patient (0.7%) in the 2.5 mg apixaban group, 2 patients (1.4%) in the 5-mg apixaban group, and 1 patient (0.7%) in the placebo group.

The researchers found that the absolute risk reductions compared with placebo for the primary outcome were 0.0% (95% confidence interval not calculable) in the aspirin group, 0.7% (95% confidence interval, -2.1% to 4.1%) in the prophylactic-dose apixaban group, and 1.4% (95% CI, -1.5% to 5%) in the therapeutic-dose apixaban group.

No major bleeding events were reported.

The absolute risk differences compared with placebo for clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding events were 2% (95% CI, -2.7% to 6.8%) in the aspirin group, 4.5% (95% CI, -0.7% to 10.2%) in the prophylactic-dose apixaban group, and 6.9% (95% CI, 1.4% to 12.9%) in the therapeutic-dose apixaban group.

Safety and efficacy results were similar in all randomly assigned patients.

The researchers speculated that a combination of two demographic shifts over time may have led to the lower than anticipated rate of events in ACTIV-4B.

“First, the threshold for hospital admission has markedly declined since the beginning of the pandemic, such that hospitalization is no longer limited almost exclusively to those with severe pulmonary distress likely to require mechanical ventilation,” they write. “As a result, the severity of illness among individuals with COVID-19 and destined for outpatient care has declined.”

“Second, at least within the U.S., where the trial was conducted, individuals currently being infected with SARS-CoV-2 tend to be younger and have fewer comorbidities when compared with individuals with incident infection at the onset of the pandemic,” they add.

Further, COVID-19 testing was quite limited early in the pandemic, they note, “and it is possible that the anticipated event rates based on data from registries available at that time were overestimated because the denominator (that is, the number of infected individuals overall) was essentially unknown.”

Robust evidence

“The ACTIV-4B trial is the first randomized trial to generate robust evidence about the effects of antithrombotic therapy in outpatients with COVID-19,” Otavio Berwanger, MD, PhD, director of the Academic Research Organization, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, Sao Paulo-SP, Brazil, told this news organization.

“It should be noted that this was a well-designed trial with low risk of bias. On the other hand, the main limitation is the low number of events and, consequently, the limited statistical power,” said Dr. Berwanger, who wrote an accompanying editorial.

The ACTIV-4B trial has immediate implications for clinical practice, he added.

“In this sense, considering the neutral results for major cardiopulmonary outcomes, the use of aspirin or apixaban for the management of outpatients with COVID-19 should not be recommended.”

ACTIV-4B also provides useful information for the steering committees of other ongoing trials of antithrombotic therapy for patients with COVID-19 who are not hospitalized, Dr. Berwanger added.

“In this sense, probably issues like statistical power, outcome choices, recruitment feasibility, and even futility would need to be revisited. And finally, lessons learned from the implementation of an innovative, pragmatic, and decentralized trial design represent an important legacy for future trials in cardiovascular diseases and other common conditions,” he said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Connors reports financial relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Abbott, Alnylam, Takeda, Roche, and Sanofi. Dr. Berwanger reports financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Amgen, Servier, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer, Novartis, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

USPSTF statement on aspirin: poor messaging at best

: “The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that initiating aspirin use for the primary prevention of CVD events in adults age 60 years or older has no net benefit.” I take no issue with the data and appreciate the efforts of the researchers, but at a minimum the public statement is incomplete. At most, it’s dangerously poor messaging.

As physicians, we understand how best to apply this information, but most laypeople, some at significant cardiovascular risk, closed their medicine cabinets this morning and left their aspirin bottle unopened on the shelf. Some of these patients have never spent an hour in the hospital for cardiac-related issues, but they have mitigated their risk for myocardial infarction by purposely poisoning their platelets daily with 81 mg of aspirin. And they should continue to do so.

Don’t forget the calcium score

Take, for instance, my patient Jack, who is typical of many patients I’ve seen throughout the years. Jack is 68 years old and has never had a cardiac event or a gastrointestinal bleed. His daily routine includes a walk, a statin, and a baby aspirin because his CT coronary artery calcium (CAC) score was 10,000 at age 58.

He first visited me 10 years ago because his father died of a myocardial infarction in his late 50s. Jack’s left ventricular ejection fraction is normal and his stress ECG shows 1-mm ST-segment depression at 8 minutes on a Bruce protocol stress test, without angina. Because Jack is well-educated and keeps up with the latest cardiology recommendations, he is precisely the type of patient who may be harmed by this new USPSTF statement by stopping his aspirin.

In October 2020, an analysis from the DALLAS Heart Study showed that persons with a CAC score greater than 100 had a higher cumulative incidence of bleeding and of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events compared with those with no coronary calcium. After adjustment for clinical risk factors, the association between CAC and bleeding was attenuated and no longer statistically significant, whereas the relationship between CAC and ASCVD remained.

I asked one of the investigators, Amit Khera, MD, MSc, from UT Southwestern Medical Center, about the latest recommendations. He emphasized that both the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association prevention guidelines and the USPSTF statement say that aspirin could still be considered among patients who are at higher risk for cardiovascular events. The USPSTF delineated this as a 10-year ASCVD risk greater than 10%.

Dr. Khera, who was an author of the 2019 guidelines, explained that the guideline committee purposely did not make specific recommendations as to what demarcated higher risk because the data were not clear at that time. Since then, a couple of papers, including the Dallas Heart Study analysis published in JAMA Cardiology, showed that patients at low bleeding risk with a calcium score above 100 may get a net benefit from aspirin. “Thus, in my patients who have a high calcium score and low bleeding risk, I do discuss the option to start or continue aspirin,” he said.

One size does not fit all

I watched ABC World News Tonight on Tuesday, October 12, and was immediately troubled about the coverage of the USPSTF statement. With viewership for the “Big Three” networks in the millions, the message to discontinue aspirin may have unintended consequences for many at-risk patients. The blood-thinning effects of a single dose of aspirin last about 10 days; it will be interesting to see if the rates of myocardial infarction increase over time. This could have been avoided with a better-worded statement – I’m concerned that the lack of nuance could spell big trouble for some.

In JAMA Cardiology, Dr. Khera and colleagues wrote that, “Aspirin use is not a one-size-fits-all therapy.” All physicians likely agree with that opinion. The USPSTF statement should have included the point that if you have a high CT coronary artery calcium score and a low bleeding risk, aspirin still fits very well even if you haven’t experienced a cardiac event. At a minimum, the USPSTF statement should have included the suggestion for patients to consult their physician for advice before discontinuing aspirin therapy.

I hope patients like Jack get the right message.

Melissa Walton-Shirley, MD, is a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

: “The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that initiating aspirin use for the primary prevention of CVD events in adults age 60 years or older has no net benefit.” I take no issue with the data and appreciate the efforts of the researchers, but at a minimum the public statement is incomplete. At most, it’s dangerously poor messaging.

As physicians, we understand how best to apply this information, but most laypeople, some at significant cardiovascular risk, closed their medicine cabinets this morning and left their aspirin bottle unopened on the shelf. Some of these patients have never spent an hour in the hospital for cardiac-related issues, but they have mitigated their risk for myocardial infarction by purposely poisoning their platelets daily with 81 mg of aspirin. And they should continue to do so.

Don’t forget the calcium score

Take, for instance, my patient Jack, who is typical of many patients I’ve seen throughout the years. Jack is 68 years old and has never had a cardiac event or a gastrointestinal bleed. His daily routine includes a walk, a statin, and a baby aspirin because his CT coronary artery calcium (CAC) score was 10,000 at age 58.

He first visited me 10 years ago because his father died of a myocardial infarction in his late 50s. Jack’s left ventricular ejection fraction is normal and his stress ECG shows 1-mm ST-segment depression at 8 minutes on a Bruce protocol stress test, without angina. Because Jack is well-educated and keeps up with the latest cardiology recommendations, he is precisely the type of patient who may be harmed by this new USPSTF statement by stopping his aspirin.

In October 2020, an analysis from the DALLAS Heart Study showed that persons with a CAC score greater than 100 had a higher cumulative incidence of bleeding and of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events compared with those with no coronary calcium. After adjustment for clinical risk factors, the association between CAC and bleeding was attenuated and no longer statistically significant, whereas the relationship between CAC and ASCVD remained.

I asked one of the investigators, Amit Khera, MD, MSc, from UT Southwestern Medical Center, about the latest recommendations. He emphasized that both the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association prevention guidelines and the USPSTF statement say that aspirin could still be considered among patients who are at higher risk for cardiovascular events. The USPSTF delineated this as a 10-year ASCVD risk greater than 10%.

Dr. Khera, who was an author of the 2019 guidelines, explained that the guideline committee purposely did not make specific recommendations as to what demarcated higher risk because the data were not clear at that time. Since then, a couple of papers, including the Dallas Heart Study analysis published in JAMA Cardiology, showed that patients at low bleeding risk with a calcium score above 100 may get a net benefit from aspirin. “Thus, in my patients who have a high calcium score and low bleeding risk, I do discuss the option to start or continue aspirin,” he said.

One size does not fit all

I watched ABC World News Tonight on Tuesday, October 12, and was immediately troubled about the coverage of the USPSTF statement. With viewership for the “Big Three” networks in the millions, the message to discontinue aspirin may have unintended consequences for many at-risk patients. The blood-thinning effects of a single dose of aspirin last about 10 days; it will be interesting to see if the rates of myocardial infarction increase over time. This could have been avoided with a better-worded statement – I’m concerned that the lack of nuance could spell big trouble for some.

In JAMA Cardiology, Dr. Khera and colleagues wrote that, “Aspirin use is not a one-size-fits-all therapy.” All physicians likely agree with that opinion. The USPSTF statement should have included the point that if you have a high CT coronary artery calcium score and a low bleeding risk, aspirin still fits very well even if you haven’t experienced a cardiac event. At a minimum, the USPSTF statement should have included the suggestion for patients to consult their physician for advice before discontinuing aspirin therapy.

I hope patients like Jack get the right message.

Melissa Walton-Shirley, MD, is a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

: “The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that initiating aspirin use for the primary prevention of CVD events in adults age 60 years or older has no net benefit.” I take no issue with the data and appreciate the efforts of the researchers, but at a minimum the public statement is incomplete. At most, it’s dangerously poor messaging.

As physicians, we understand how best to apply this information, but most laypeople, some at significant cardiovascular risk, closed their medicine cabinets this morning and left their aspirin bottle unopened on the shelf. Some of these patients have never spent an hour in the hospital for cardiac-related issues, but they have mitigated their risk for myocardial infarction by purposely poisoning their platelets daily with 81 mg of aspirin. And they should continue to do so.

Don’t forget the calcium score

Take, for instance, my patient Jack, who is typical of many patients I’ve seen throughout the years. Jack is 68 years old and has never had a cardiac event or a gastrointestinal bleed. His daily routine includes a walk, a statin, and a baby aspirin because his CT coronary artery calcium (CAC) score was 10,000 at age 58.

He first visited me 10 years ago because his father died of a myocardial infarction in his late 50s. Jack’s left ventricular ejection fraction is normal and his stress ECG shows 1-mm ST-segment depression at 8 minutes on a Bruce protocol stress test, without angina. Because Jack is well-educated and keeps up with the latest cardiology recommendations, he is precisely the type of patient who may be harmed by this new USPSTF statement by stopping his aspirin.

In October 2020, an analysis from the DALLAS Heart Study showed that persons with a CAC score greater than 100 had a higher cumulative incidence of bleeding and of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events compared with those with no coronary calcium. After adjustment for clinical risk factors, the association between CAC and bleeding was attenuated and no longer statistically significant, whereas the relationship between CAC and ASCVD remained.

I asked one of the investigators, Amit Khera, MD, MSc, from UT Southwestern Medical Center, about the latest recommendations. He emphasized that both the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association prevention guidelines and the USPSTF statement say that aspirin could still be considered among patients who are at higher risk for cardiovascular events. The USPSTF delineated this as a 10-year ASCVD risk greater than 10%.

Dr. Khera, who was an author of the 2019 guidelines, explained that the guideline committee purposely did not make specific recommendations as to what demarcated higher risk because the data were not clear at that time. Since then, a couple of papers, including the Dallas Heart Study analysis published in JAMA Cardiology, showed that patients at low bleeding risk with a calcium score above 100 may get a net benefit from aspirin. “Thus, in my patients who have a high calcium score and low bleeding risk, I do discuss the option to start or continue aspirin,” he said.

One size does not fit all

I watched ABC World News Tonight on Tuesday, October 12, and was immediately troubled about the coverage of the USPSTF statement. With viewership for the “Big Three” networks in the millions, the message to discontinue aspirin may have unintended consequences for many at-risk patients. The blood-thinning effects of a single dose of aspirin last about 10 days; it will be interesting to see if the rates of myocardial infarction increase over time. This could have been avoided with a better-worded statement – I’m concerned that the lack of nuance could spell big trouble for some.

In JAMA Cardiology, Dr. Khera and colleagues wrote that, “Aspirin use is not a one-size-fits-all therapy.” All physicians likely agree with that opinion. The USPSTF statement should have included the point that if you have a high CT coronary artery calcium score and a low bleeding risk, aspirin still fits very well even if you haven’t experienced a cardiac event. At a minimum, the USPSTF statement should have included the suggestion for patients to consult their physician for advice before discontinuing aspirin therapy.

I hope patients like Jack get the right message.

Melissa Walton-Shirley, MD, is a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Broken heart syndrome: on the rise, especially in women 50-74

As a pediatric kidney doctor, Elaine S. Kamil, MD, is used to long hours helping children and teens with a variety of issues, some very serious, and also makes time to give back to her specialty.

In late 2013, she was in Washington, D.C., planning a meeting of the American Society of Nephrology. When the organizers decided at the last minute that another session was needed, she stayed late, putting it together. Then she hopped on a plane and returned home to Los Angeles on a Saturday night.

Right after midnight, Dr. Kamil knew something was wrong.

“I had really severe chest pain,” she says. “I have reflux, and I know what that feels like. This was much more intense. It really hurt.” She debated: “Should I wake up my husband?”

Soon, the pain got so bad, she had to.

At the hospital, an electrocardiogram was slightly abnormal, as was a blood test that measures damage to the heart. Next, she got an angiogram, an imaging technique to visualize the heart. Once doctors looked at the image on the screen during the angiogram, they knew the diagnosis: Broken heart syndrome, known medically as takotsubo cardiomyopathy or stress-induced cardiomyopathy. As the name suggests, it’s triggered by extreme stress or loss.

The telltale clue to the diagnosis is the appearance of the walls of the heart’s left ventricle, its main pumping chamber. When the condition is present, the left ventricle changes shape, developing a narrow neck and a round bottom, resembling an octopus pot called takotsubo used by fishermen in Japan, where the condition was first recognized in 1990.

Like most who are affected, Dr. Kamil, now 74, is fine now. She is still actively working, as a researcher and professor emerita at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and a health sciences clinical professor of pediatrics at UCLA. But she focuses more now on stress reduction.

Study: condition on the rise

New research from Cedars-Sinai suggests that broken heart syndrome, while still not common, is not as rare as once thought. And it’s on the rise, especially among middle-age and older women.

This ‘’middle” group – women ages 50 to 74 – had the greatest rate of increase over the years studied, 2006-2017, says Susan Cheng, MD, lead author of the study, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association. She is the director of the Institute for Research on Healthy Aging at the Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

Dr. Cheng and her team used national hospital inpatient data collected from more than 135,000 men and women diagnosed with the condition during the 12 years of the study. More than 88% of all cases were women, especially in those age 50 or older. When the researchers looked more closely, they found the diagnosis has been increasing at least 6 to 10 times more rapidly for women in the 50-to-74 age group than in any other group.

For every case of the condition in younger women, or in men of all age groups, the researchers found an additional 10 cases for middle-aged women and six additional cases for older women. For example, while the syndrome occurred in 15 younger women per million per year, it occurred in 128 middle aged women per year.

The age groups found most at risk was surprising, says Dr. Cheng, who expected the risk would be highest in the oldest age group of women, those over 75.

While doctors are more aware of the condition now, “it’s not just the increased recognition,” she says. “There is something going on” driving the continual increase. It probably has something to do with environmental changes, she says.

Hormones and hormonal differences between men and women aren’t the whole story either, she says. Her team will study it further, hoping eventually to find who might be more likely to get the condition by talking to those who have had it and collecting clues. “There probably is some underlying genetic predisposition,” she says.

“The neural hormones that drive the flight-or-fight response (such as adrenaline) are definitely elevated,” she says. “The brain and the heart are talking to each other.”

Experts say these surging stress hormones essentially “stun” the heart, affecting how it functions. The question is, what makes women particularly more susceptible to being excessively triggered when exposed to stress? That is unclear, Dr. Cheng says.

While the condition is a frightening experience, ‘’the overall prognosis is much better than having a garden-variety heart attack,” she says.

But researchers are still figuring out long-term outcomes, and she can’t tell patients if they are likely to have another episode.

Research findings reflected in practice

Other cardiologists say they are not surprised by the new findings.

“I think it’s very consistent with what I am seeing clinically,” says Tracy Stevens, MD, a cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City, MO. In the last 5 years, she has diagnosed at least 100 cases, she says. The increase is partly but not entirely due to increased awareness by doctors of the condition, she agrees.

If a postmenopausal woman comes to the hospital with chest pain, the condition is more likely now than in the past to be suspected, says Dr. Stevens, who’s also the medical director of the Muriel I. Kauffman Women’s Heart Center at Saint Luke’s. The octopus pot-like image is hard to miss.

“What we see at the base of the left ventricle is, it is squeezing like crazy, it is ballooning.”

“We probably see at least five to ten a month,” says Kevin Bybee, MD, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine.

The increase in numbers found by the Los Angeles researchers may not even capture the true picture of how many people have gotten this condition, he says. He suspects some women whose deaths are blamed on sudden cardiac death might actually have had broken heart syndrome.

“I have always wondered how many don’t make it to the hospital.”

Dr. Bybee, who’s also medical director of cardiovascular services at St. Luke’s South in Overland Park, KS, became interested in the syndrome during his fellowship at Mayo Clinic when he diagnosed three patients in just 2 months. He and his team published the case histories of seven patients in 2004. Since then, many more reports have been published.

Researchers from Texas used the same national database as the Cedars researchers to look at cases from 2005 to 2014, and also found an increase. But study co-author Abhijeet Dhoble, MD, a cardiologist and associate professor of medicine at UT Health Science Center and Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center in Houston, believes more recognition explains most of the increase.

And the pandemic is now playing a role in driving up cases, he says.

“In the last 2 years, we have been noticing increasing numbers of cases, probably due to the pandemic,” he says.

Profiles of cases

Over the years, Dr. Bybee has collected information on what is happening before the heart begins to go haywire.

“Fifteen to twenty percent of the time, there is no obvious trigger,” he says.

Other times, a stressful emotional event, such as the death of a spouse or a severe car accident, can trigger it.

One patient with an extreme fear of public speaking had to give a talk in front of a large group when she was new to a job. Another woman lost money at a casino before it happened, Dr. Bybee says. Yet another patient took her dog out for a walk in the woods, and the dog got caught in a raccoon trap.

Fierce arguments as well as surprise parties have triggered the condition, Dr. Bybee says. Physical problems such as asthma or sepsis, a life-threatening complication of an infection, can also trigger broken heart.

“It’s challenging because this is unpredictable,” he says.

Treatments and recovery

The condition is rarely fatal, say experts from Harvard and Mayo Clinic, but some can have complications such as heart failure.

There are no standard guidelines for treatment, Dr. Dhoble, of Memorial Hermann, says. “We give medications to keep blood pressures in the optimal range.” Doctors may also prescribe lipid-lowering medicines and blood thinner medications. “Most patients recover within 3 to 7 days.”

“Usually within a month, their [heart] function returns to normal,” Dr. Stevens says.

Getting one’s full energy back can take longer, as Dr. Kamil found. “It was about 6 months before I was up to speed.”

Survivors talk

Looking back, Dr. Kamil realizes now how much stress she was under before her episode.

“I took care of chronically ill kids,” she says, and worried about them. “I’m kind of a mother hen.”

Besides patient care and her cross-county meeting planning, she was flying back and forth to Florida to tend to her mother, who had chronic health problems. She was also managing that year’s annual media prize at a San Diego university that she and her husband established after the death of their adult son several years before.

“I was busy with that, and it is a bittersweet experience,” she says.

She is trying to take her cardiologist’s advice to slow down.

“I used to be notorious for saying, ‘I need to get one more thing done,’” she says.

Joanie Simpson says she, too, has slowed down. She was diagnosed with broken heart in 2016, after a cascade of stressful events. Her son was facing back surgery, her son-in-law had lost his job, and her tiny Yorkshire terrier Meha died. And she and her husband, Benny, had issues with their rental property.

Now 66 and retired in Camp Wood, Texas, she has learned to enjoy life and worry a little less. Music is one way.

“We’re Parrotheads,” she says, referencing the nickname given to fans of singer Jimmy Buffett. “We listen to Buffett and to ’60s, ’70s, ’80s music. We dance around the house. We aren’t big tavern goers, so we dance around the living room and hope we don’t fall over the coffee table. So far, so good.”

They have plans to buy a small pontoon boat and go fishing. Benny especially loves that idea, she says, laughing, as he finds it’s the only time she stops talking.

Reducing the what-ifs

Patients have a common question and worry: What if it happens again?

“I definitely worried more about it in the beginning,” Dr. Kamil says. “Could I have permanent heart damage? Will I be a cardiac cripple?” Her worry has eased.

If you suspect the condition, ‘’get yourself to a provider who knows about it,” she says.

Cardiologists are very likely to suspect the condition, Dr. Bybee says, as are doctors working in a large-volume emergency department.

Dr. Stevens, of St. Luke’s, is straightforward, telling her patients what is known and what is not about the condition. She recommends her patients go to cardiac rehab.

“It gives them that confidence to know what they can do,” she says.

She also gives lifestyle advice, suggesting patients get a home blood pressure cuff and use it. She suggests paying attention to good nutrition and exercise and not lifting anything so heavy that grunting is necessary.

Focus on protecting heart health, Dr. Cheng tells patients. She encourages them to find the stress reduction plan that works for them. Most important, she tells patients to understand that it is not their fault.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

As a pediatric kidney doctor, Elaine S. Kamil, MD, is used to long hours helping children and teens with a variety of issues, some very serious, and also makes time to give back to her specialty.

In late 2013, she was in Washington, D.C., planning a meeting of the American Society of Nephrology. When the organizers decided at the last minute that another session was needed, she stayed late, putting it together. Then she hopped on a plane and returned home to Los Angeles on a Saturday night.

Right after midnight, Dr. Kamil knew something was wrong.

“I had really severe chest pain,” she says. “I have reflux, and I know what that feels like. This was much more intense. It really hurt.” She debated: “Should I wake up my husband?”

Soon, the pain got so bad, she had to.

At the hospital, an electrocardiogram was slightly abnormal, as was a blood test that measures damage to the heart. Next, she got an angiogram, an imaging technique to visualize the heart. Once doctors looked at the image on the screen during the angiogram, they knew the diagnosis: Broken heart syndrome, known medically as takotsubo cardiomyopathy or stress-induced cardiomyopathy. As the name suggests, it’s triggered by extreme stress or loss.

The telltale clue to the diagnosis is the appearance of the walls of the heart’s left ventricle, its main pumping chamber. When the condition is present, the left ventricle changes shape, developing a narrow neck and a round bottom, resembling an octopus pot called takotsubo used by fishermen in Japan, where the condition was first recognized in 1990.

Like most who are affected, Dr. Kamil, now 74, is fine now. She is still actively working, as a researcher and professor emerita at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and a health sciences clinical professor of pediatrics at UCLA. But she focuses more now on stress reduction.

Study: condition on the rise

New research from Cedars-Sinai suggests that broken heart syndrome, while still not common, is not as rare as once thought. And it’s on the rise, especially among middle-age and older women.

This ‘’middle” group – women ages 50 to 74 – had the greatest rate of increase over the years studied, 2006-2017, says Susan Cheng, MD, lead author of the study, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association. She is the director of the Institute for Research on Healthy Aging at the Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

Dr. Cheng and her team used national hospital inpatient data collected from more than 135,000 men and women diagnosed with the condition during the 12 years of the study. More than 88% of all cases were women, especially in those age 50 or older. When the researchers looked more closely, they found the diagnosis has been increasing at least 6 to 10 times more rapidly for women in the 50-to-74 age group than in any other group.

For every case of the condition in younger women, or in men of all age groups, the researchers found an additional 10 cases for middle-aged women and six additional cases for older women. For example, while the syndrome occurred in 15 younger women per million per year, it occurred in 128 middle aged women per year.

The age groups found most at risk was surprising, says Dr. Cheng, who expected the risk would be highest in the oldest age group of women, those over 75.

While doctors are more aware of the condition now, “it’s not just the increased recognition,” she says. “There is something going on” driving the continual increase. It probably has something to do with environmental changes, she says.

Hormones and hormonal differences between men and women aren’t the whole story either, she says. Her team will study it further, hoping eventually to find who might be more likely to get the condition by talking to those who have had it and collecting clues. “There probably is some underlying genetic predisposition,” she says.

“The neural hormones that drive the flight-or-fight response (such as adrenaline) are definitely elevated,” she says. “The brain and the heart are talking to each other.”

Experts say these surging stress hormones essentially “stun” the heart, affecting how it functions. The question is, what makes women particularly more susceptible to being excessively triggered when exposed to stress? That is unclear, Dr. Cheng says.

While the condition is a frightening experience, ‘’the overall prognosis is much better than having a garden-variety heart attack,” she says.

But researchers are still figuring out long-term outcomes, and she can’t tell patients if they are likely to have another episode.

Research findings reflected in practice

Other cardiologists say they are not surprised by the new findings.

“I think it’s very consistent with what I am seeing clinically,” says Tracy Stevens, MD, a cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City, MO. In the last 5 years, she has diagnosed at least 100 cases, she says. The increase is partly but not entirely due to increased awareness by doctors of the condition, she agrees.

If a postmenopausal woman comes to the hospital with chest pain, the condition is more likely now than in the past to be suspected, says Dr. Stevens, who’s also the medical director of the Muriel I. Kauffman Women’s Heart Center at Saint Luke’s. The octopus pot-like image is hard to miss.

“What we see at the base of the left ventricle is, it is squeezing like crazy, it is ballooning.”

“We probably see at least five to ten a month,” says Kevin Bybee, MD, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine.

The increase in numbers found by the Los Angeles researchers may not even capture the true picture of how many people have gotten this condition, he says. He suspects some women whose deaths are blamed on sudden cardiac death might actually have had broken heart syndrome.

“I have always wondered how many don’t make it to the hospital.”

Dr. Bybee, who’s also medical director of cardiovascular services at St. Luke’s South in Overland Park, KS, became interested in the syndrome during his fellowship at Mayo Clinic when he diagnosed three patients in just 2 months. He and his team published the case histories of seven patients in 2004. Since then, many more reports have been published.

Researchers from Texas used the same national database as the Cedars researchers to look at cases from 2005 to 2014, and also found an increase. But study co-author Abhijeet Dhoble, MD, a cardiologist and associate professor of medicine at UT Health Science Center and Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center in Houston, believes more recognition explains most of the increase.

And the pandemic is now playing a role in driving up cases, he says.

“In the last 2 years, we have been noticing increasing numbers of cases, probably due to the pandemic,” he says.

Profiles of cases

Over the years, Dr. Bybee has collected information on what is happening before the heart begins to go haywire.

“Fifteen to twenty percent of the time, there is no obvious trigger,” he says.

Other times, a stressful emotional event, such as the death of a spouse or a severe car accident, can trigger it.

One patient with an extreme fear of public speaking had to give a talk in front of a large group when she was new to a job. Another woman lost money at a casino before it happened, Dr. Bybee says. Yet another patient took her dog out for a walk in the woods, and the dog got caught in a raccoon trap.

Fierce arguments as well as surprise parties have triggered the condition, Dr. Bybee says. Physical problems such as asthma or sepsis, a life-threatening complication of an infection, can also trigger broken heart.

“It’s challenging because this is unpredictable,” he says.

Treatments and recovery

The condition is rarely fatal, say experts from Harvard and Mayo Clinic, but some can have complications such as heart failure.

There are no standard guidelines for treatment, Dr. Dhoble, of Memorial Hermann, says. “We give medications to keep blood pressures in the optimal range.” Doctors may also prescribe lipid-lowering medicines and blood thinner medications. “Most patients recover within 3 to 7 days.”

“Usually within a month, their [heart] function returns to normal,” Dr. Stevens says.

Getting one’s full energy back can take longer, as Dr. Kamil found. “It was about 6 months before I was up to speed.”

Survivors talk

Looking back, Dr. Kamil realizes now how much stress she was under before her episode.

“I took care of chronically ill kids,” she says, and worried about them. “I’m kind of a mother hen.”

Besides patient care and her cross-county meeting planning, she was flying back and forth to Florida to tend to her mother, who had chronic health problems. She was also managing that year’s annual media prize at a San Diego university that she and her husband established after the death of their adult son several years before.

“I was busy with that, and it is a bittersweet experience,” she says.

She is trying to take her cardiologist’s advice to slow down.

“I used to be notorious for saying, ‘I need to get one more thing done,’” she says.

Joanie Simpson says she, too, has slowed down. She was diagnosed with broken heart in 2016, after a cascade of stressful events. Her son was facing back surgery, her son-in-law had lost his job, and her tiny Yorkshire terrier Meha died. And she and her husband, Benny, had issues with their rental property.

Now 66 and retired in Camp Wood, Texas, she has learned to enjoy life and worry a little less. Music is one way.

“We’re Parrotheads,” she says, referencing the nickname given to fans of singer Jimmy Buffett. “We listen to Buffett and to ’60s, ’70s, ’80s music. We dance around the house. We aren’t big tavern goers, so we dance around the living room and hope we don’t fall over the coffee table. So far, so good.”

They have plans to buy a small pontoon boat and go fishing. Benny especially loves that idea, she says, laughing, as he finds it’s the only time she stops talking.

Reducing the what-ifs

Patients have a common question and worry: What if it happens again?

“I definitely worried more about it in the beginning,” Dr. Kamil says. “Could I have permanent heart damage? Will I be a cardiac cripple?” Her worry has eased.

If you suspect the condition, ‘’get yourself to a provider who knows about it,” she says.

Cardiologists are very likely to suspect the condition, Dr. Bybee says, as are doctors working in a large-volume emergency department.

Dr. Stevens, of St. Luke’s, is straightforward, telling her patients what is known and what is not about the condition. She recommends her patients go to cardiac rehab.

“It gives them that confidence to know what they can do,” she says.

She also gives lifestyle advice, suggesting patients get a home blood pressure cuff and use it. She suggests paying attention to good nutrition and exercise and not lifting anything so heavy that grunting is necessary.

Focus on protecting heart health, Dr. Cheng tells patients. She encourages them to find the stress reduction plan that works for them. Most important, she tells patients to understand that it is not their fault.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

As a pediatric kidney doctor, Elaine S. Kamil, MD, is used to long hours helping children and teens with a variety of issues, some very serious, and also makes time to give back to her specialty.

In late 2013, she was in Washington, D.C., planning a meeting of the American Society of Nephrology. When the organizers decided at the last minute that another session was needed, she stayed late, putting it together. Then she hopped on a plane and returned home to Los Angeles on a Saturday night.

Right after midnight, Dr. Kamil knew something was wrong.

“I had really severe chest pain,” she says. “I have reflux, and I know what that feels like. This was much more intense. It really hurt.” She debated: “Should I wake up my husband?”

Soon, the pain got so bad, she had to.

At the hospital, an electrocardiogram was slightly abnormal, as was a blood test that measures damage to the heart. Next, she got an angiogram, an imaging technique to visualize the heart. Once doctors looked at the image on the screen during the angiogram, they knew the diagnosis: Broken heart syndrome, known medically as takotsubo cardiomyopathy or stress-induced cardiomyopathy. As the name suggests, it’s triggered by extreme stress or loss.

The telltale clue to the diagnosis is the appearance of the walls of the heart’s left ventricle, its main pumping chamber. When the condition is present, the left ventricle changes shape, developing a narrow neck and a round bottom, resembling an octopus pot called takotsubo used by fishermen in Japan, where the condition was first recognized in 1990.

Like most who are affected, Dr. Kamil, now 74, is fine now. She is still actively working, as a researcher and professor emerita at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and a health sciences clinical professor of pediatrics at UCLA. But she focuses more now on stress reduction.

Study: condition on the rise

New research from Cedars-Sinai suggests that broken heart syndrome, while still not common, is not as rare as once thought. And it’s on the rise, especially among middle-age and older women.

This ‘’middle” group – women ages 50 to 74 – had the greatest rate of increase over the years studied, 2006-2017, says Susan Cheng, MD, lead author of the study, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association. She is the director of the Institute for Research on Healthy Aging at the Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

Dr. Cheng and her team used national hospital inpatient data collected from more than 135,000 men and women diagnosed with the condition during the 12 years of the study. More than 88% of all cases were women, especially in those age 50 or older. When the researchers looked more closely, they found the diagnosis has been increasing at least 6 to 10 times more rapidly for women in the 50-to-74 age group than in any other group.

For every case of the condition in younger women, or in men of all age groups, the researchers found an additional 10 cases for middle-aged women and six additional cases for older women. For example, while the syndrome occurred in 15 younger women per million per year, it occurred in 128 middle aged women per year.

The age groups found most at risk was surprising, says Dr. Cheng, who expected the risk would be highest in the oldest age group of women, those over 75.

While doctors are more aware of the condition now, “it’s not just the increased recognition,” she says. “There is something going on” driving the continual increase. It probably has something to do with environmental changes, she says.

Hormones and hormonal differences between men and women aren’t the whole story either, she says. Her team will study it further, hoping eventually to find who might be more likely to get the condition by talking to those who have had it and collecting clues. “There probably is some underlying genetic predisposition,” she says.