User login

Surgical Risks From Systemic Psoriasis Therapies

I am a coauthor on a recent literature review (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:798.e7-805.e7) that addressed a common question regarding the use of systemic agents: What should a clinician do if a patient on one of these therapies has an upcoming elective surgery?

Treatment with systemic immunomodulatory agents commonly is employed in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. In these individuals, the concern is that surgery may carry an increased risk for infectious or surgical complications. Based on the available literature, my coauthors and I sought to create recommendations for the perioperative management of systemic immunosuppressive therapies in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. We conducted a literature review to examine studies that addressed the use of methotrexate, cyclosporine, and biologic agents in patients undergoing surgery. A total of 46 studies were examined, nearly all retrospective studies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis.

Based on level III evidence, we concluded that infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, methotrexate, and cyclosporine can be safely continued through low-risk operations in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. For moderate- and high-risk surgeries, a case-by-case approach should be taken based on the patient’s individual risk factors and comorbidities.

What’s the issue?

This study does not provide specific guidelines because of limited and conflicting literature. However, it does provide general guidelines that hopefully will be augmented in the future. How will you handle this situation when it arises in your practice?

I am a coauthor on a recent literature review (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:798.e7-805.e7) that addressed a common question regarding the use of systemic agents: What should a clinician do if a patient on one of these therapies has an upcoming elective surgery?

Treatment with systemic immunomodulatory agents commonly is employed in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. In these individuals, the concern is that surgery may carry an increased risk for infectious or surgical complications. Based on the available literature, my coauthors and I sought to create recommendations for the perioperative management of systemic immunosuppressive therapies in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. We conducted a literature review to examine studies that addressed the use of methotrexate, cyclosporine, and biologic agents in patients undergoing surgery. A total of 46 studies were examined, nearly all retrospective studies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis.

Based on level III evidence, we concluded that infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, methotrexate, and cyclosporine can be safely continued through low-risk operations in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. For moderate- and high-risk surgeries, a case-by-case approach should be taken based on the patient’s individual risk factors and comorbidities.

What’s the issue?

This study does not provide specific guidelines because of limited and conflicting literature. However, it does provide general guidelines that hopefully will be augmented in the future. How will you handle this situation when it arises in your practice?

I am a coauthor on a recent literature review (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:798.e7-805.e7) that addressed a common question regarding the use of systemic agents: What should a clinician do if a patient on one of these therapies has an upcoming elective surgery?

Treatment with systemic immunomodulatory agents commonly is employed in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. In these individuals, the concern is that surgery may carry an increased risk for infectious or surgical complications. Based on the available literature, my coauthors and I sought to create recommendations for the perioperative management of systemic immunosuppressive therapies in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. We conducted a literature review to examine studies that addressed the use of methotrexate, cyclosporine, and biologic agents in patients undergoing surgery. A total of 46 studies were examined, nearly all retrospective studies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis.

Based on level III evidence, we concluded that infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, methotrexate, and cyclosporine can be safely continued through low-risk operations in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. For moderate- and high-risk surgeries, a case-by-case approach should be taken based on the patient’s individual risk factors and comorbidities.

What’s the issue?

This study does not provide specific guidelines because of limited and conflicting literature. However, it does provide general guidelines that hopefully will be augmented in the future. How will you handle this situation when it arises in your practice?

Scalp Psoriasis: Weighing Treatment Options

Scalp psoriasis often is the initial presentation of psoriasis, and it can be one of the most challenging aspects of the disease. It can be difficult to treat for several reasons. First, hair can interfere with topical therapy reaching its site of action on the scalp. Second, facial skin also can be exposed to these treatments with the associated risk for adverse events. Finally, compliance often is difficult.

An evidence-based review published online on September 21 in the American Journal of Clinical Dermatology examined treatments for scalp psoriasis, including newer systemic therapies. Of 475 studies initially identified from PubMed and 845 from Embase (up to May 2016), the review included 27 clinical trials, 4 papers reporting pooled analyses of other clinical trials, 10 open-label trials, 1 case series, and 2 case reports after excluding non-English literature.

Wang and Tsai noted that few randomized controlled trials have been performed specifically in scalp psoriasis. The authors found that topical corticosteroids provide good effects and are usually recommended as first-line treatment. Calcipotriol–betamethasone dipropionate is more highly effective than either of its individual components.

The analysis also suggested that localized phototherapy is better than generalized phototherapy on hair-bearing areas. Methotrexate, cyclosporine, fumaric acid esters, and acitretin are well-recognized agents in the treatment of psoriasis, but they located no published randomized controlled trials specifically evaluating these agents in scalp psoriasis. Wang and Tsai also commented that biologics and new small-molecule agents show excellent effects on scalp psoriasis, but the high cost of these treatments mean they may be limited to use in extensive scalp psoriasis. They suggested that more controlled studies are needed for an evidence-based approach to scalp psoriasis.

What’s the issue?

Scalp psoriasis can be an isolated condition or may occur in association with more extensive disease. There has been increased attention to its treatment over the last several years, with several new options. What is your preferred approach to scalp psoriasis?

Scalp psoriasis often is the initial presentation of psoriasis, and it can be one of the most challenging aspects of the disease. It can be difficult to treat for several reasons. First, hair can interfere with topical therapy reaching its site of action on the scalp. Second, facial skin also can be exposed to these treatments with the associated risk for adverse events. Finally, compliance often is difficult.

An evidence-based review published online on September 21 in the American Journal of Clinical Dermatology examined treatments for scalp psoriasis, including newer systemic therapies. Of 475 studies initially identified from PubMed and 845 from Embase (up to May 2016), the review included 27 clinical trials, 4 papers reporting pooled analyses of other clinical trials, 10 open-label trials, 1 case series, and 2 case reports after excluding non-English literature.

Wang and Tsai noted that few randomized controlled trials have been performed specifically in scalp psoriasis. The authors found that topical corticosteroids provide good effects and are usually recommended as first-line treatment. Calcipotriol–betamethasone dipropionate is more highly effective than either of its individual components.

The analysis also suggested that localized phototherapy is better than generalized phototherapy on hair-bearing areas. Methotrexate, cyclosporine, fumaric acid esters, and acitretin are well-recognized agents in the treatment of psoriasis, but they located no published randomized controlled trials specifically evaluating these agents in scalp psoriasis. Wang and Tsai also commented that biologics and new small-molecule agents show excellent effects on scalp psoriasis, but the high cost of these treatments mean they may be limited to use in extensive scalp psoriasis. They suggested that more controlled studies are needed for an evidence-based approach to scalp psoriasis.

What’s the issue?

Scalp psoriasis can be an isolated condition or may occur in association with more extensive disease. There has been increased attention to its treatment over the last several years, with several new options. What is your preferred approach to scalp psoriasis?

Scalp psoriasis often is the initial presentation of psoriasis, and it can be one of the most challenging aspects of the disease. It can be difficult to treat for several reasons. First, hair can interfere with topical therapy reaching its site of action on the scalp. Second, facial skin also can be exposed to these treatments with the associated risk for adverse events. Finally, compliance often is difficult.

An evidence-based review published online on September 21 in the American Journal of Clinical Dermatology examined treatments for scalp psoriasis, including newer systemic therapies. Of 475 studies initially identified from PubMed and 845 from Embase (up to May 2016), the review included 27 clinical trials, 4 papers reporting pooled analyses of other clinical trials, 10 open-label trials, 1 case series, and 2 case reports after excluding non-English literature.

Wang and Tsai noted that few randomized controlled trials have been performed specifically in scalp psoriasis. The authors found that topical corticosteroids provide good effects and are usually recommended as first-line treatment. Calcipotriol–betamethasone dipropionate is more highly effective than either of its individual components.

The analysis also suggested that localized phototherapy is better than generalized phototherapy on hair-bearing areas. Methotrexate, cyclosporine, fumaric acid esters, and acitretin are well-recognized agents in the treatment of psoriasis, but they located no published randomized controlled trials specifically evaluating these agents in scalp psoriasis. Wang and Tsai also commented that biologics and new small-molecule agents show excellent effects on scalp psoriasis, but the high cost of these treatments mean they may be limited to use in extensive scalp psoriasis. They suggested that more controlled studies are needed for an evidence-based approach to scalp psoriasis.

What’s the issue?

Scalp psoriasis can be an isolated condition or may occur in association with more extensive disease. There has been increased attention to its treatment over the last several years, with several new options. What is your preferred approach to scalp psoriasis?

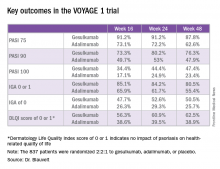

Guselkumab achieves highest-ever response rates in psoriasis

VIENNA – The investigational interleukin-23 inhibitor guselkumab decisively outperformed adalimumab in a head-to-head comparison for treatment of moderate or severe plaque psoriasis in the pivotal VOYAGE 1 study, Andrew Blauvelt, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

VOYAGE 1 was a 48-week, multicenter, international phase III trial in which 837 patients were randomized 2:2:1 to guselkumab, adalimumab (Humira), or placebo, with the placebo group switched to guselkumab at 16 weeks. Roughly three-quarters of patients had moderate psoriasis, the rest had severe disease. One in five had previously been treated with biologic agents; the only biologic disallowed was adalimumab.

The primary endpoints required by regulatory agencies involved efficacy comparisons between guselkumab and placebo at 16 weeks. Those results were a foregone conclusion. Far more arresting were the prespecified secondary endpoints comparing guselkumab to adalimumab at 24 and 48 weeks.

“These are very exciting results. We’re seeing efficacy in this trial that has not ever been seen before in a phase III study,” said Dr. Blauvelt, president of the Oregon Medical Research Center in Portland.

Take, for example, an efficacy yardstick dermatologists are quite familiar with: the PASI 75 response, defined as at least a 75% improvement from baseline in the Psoriasis Area Severity Index score, which averaged 22 at baseline in this trial. The PASI 75 rate in guselkumab-treated patients was 91.2% at 16 weeks, remained at 91.2% at 24 weeks, and was 87.8% at week 48.

“To my knowledge this is the highest PASI 75 response rate that’s been seen in a phase III study of any biologic in psoriasis,” the dermatologist said.

The PASI 75 rates with adalimumab, a tumor necrosis factor–alpha blocker widely prescribed for psoriasis, were markedly lower, although just a few years ago they would have been considered stratospheric: 73.1% at 16 weeks, 72.2% at 24 weeks, and 62.6% at 48 weeks.

The same pattern held for PASI 90, PASI 100, Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA), and quality-of-life measures.

“There is a clear early separation of guselkumab from adalimumab, sustained over time, curves staying flat, responses not dropping off,” Dr. Blauvelt said in summary.

Guselkumab was dosed at 100 mg subcutaneously at weeks 0 and 4, then every 8 weeks thereafter. Adalimumab was dosed subcutaneously at 80 mg at week 0, 40 mg at week 1, and then 40 mg every other week.

The two coprimary outcomes at week 16 in VOYAGE 1 were the guselkumab and placebo groups’ rates of clear or almost clear skin as defined by an IGA score of 0 or 1, and their PASI 90 response rates. An IGA of 0 or 1 was achieved by 85.1% of the guselkumab group compared with 6.9% on placebo. The week-16 PASI 90 rates – a “high bar” Dr. Blauvelt noted – were 73.3% and 2.9%, respectively.

“Clearly we’re now in an era where PASI 90 is the new PASI 75,” said session cochair Lajos Kemény, MD, professor and chairman of the department of dermatology and allergology at the University of Szeged, Hungary.

Guselkumab is a human monoclonal antibody directed at the p-19 subunit of interleukin-23, thereby preventing the inflammatory cytokine from binding to its receptor. In contrast, ustekinumab (Stelara) blocks both IL-23 and IL-12. Given that ustekinumab has established an excellent long-term safety record in PSOLAR, the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry, it stands to reason that guselkumab should have a favorable safety profile, too, since it targets only one of the two cytokines (J Drugs Dermatol. 2015 Jul;14[7]:706-14). And this indeed proved to be the case through 48 weeks in VOYAGE 1, according to Dr. Blauvelt.

Infections treated with antibiotics occurred in 6.1% of the guselkumab group, 7.2% of patients on adalimumab, and 7.5% on placebo. Mild to moderate injection site reactions occurred in 2.4% of patients on guselkumab and 7.5% on adalimumab. One patient on each of the biologics experienced an acute MI. Two malignancies occurred, both in the guselkumab group. One was prostate cancer, the other was a case of male breast cancer in a patient with a breast mass present at enrollment.

Results of two additional pivotal phase III trials, VOYAGE 2 and NAVIGATE, will be presented at future meetings. NAVIGATE is looking specifically at guselkumab’s performance in psoriasis patients with an inadequate response to ustekinumab.

“Those results look promising. It appears that patients who didn’t clear adequately on ustekinumab do well on guselkumab,” Dr. Blauvelt said in response to an audience question.

A phase II study of guselkumab in treating moderate to severe psoriatic arthritis is ongoing.

VOYAGE 1 was funded by Janssen, which is developing guselkumab. Dr. Blauvelt reported receiving research grants from and serving as a scientific consultant to Janssen and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

VIENNA – The investigational interleukin-23 inhibitor guselkumab decisively outperformed adalimumab in a head-to-head comparison for treatment of moderate or severe plaque psoriasis in the pivotal VOYAGE 1 study, Andrew Blauvelt, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

VOYAGE 1 was a 48-week, multicenter, international phase III trial in which 837 patients were randomized 2:2:1 to guselkumab, adalimumab (Humira), or placebo, with the placebo group switched to guselkumab at 16 weeks. Roughly three-quarters of patients had moderate psoriasis, the rest had severe disease. One in five had previously been treated with biologic agents; the only biologic disallowed was adalimumab.

The primary endpoints required by regulatory agencies involved efficacy comparisons between guselkumab and placebo at 16 weeks. Those results were a foregone conclusion. Far more arresting were the prespecified secondary endpoints comparing guselkumab to adalimumab at 24 and 48 weeks.

“These are very exciting results. We’re seeing efficacy in this trial that has not ever been seen before in a phase III study,” said Dr. Blauvelt, president of the Oregon Medical Research Center in Portland.

Take, for example, an efficacy yardstick dermatologists are quite familiar with: the PASI 75 response, defined as at least a 75% improvement from baseline in the Psoriasis Area Severity Index score, which averaged 22 at baseline in this trial. The PASI 75 rate in guselkumab-treated patients was 91.2% at 16 weeks, remained at 91.2% at 24 weeks, and was 87.8% at week 48.

“To my knowledge this is the highest PASI 75 response rate that’s been seen in a phase III study of any biologic in psoriasis,” the dermatologist said.

The PASI 75 rates with adalimumab, a tumor necrosis factor–alpha blocker widely prescribed for psoriasis, were markedly lower, although just a few years ago they would have been considered stratospheric: 73.1% at 16 weeks, 72.2% at 24 weeks, and 62.6% at 48 weeks.

The same pattern held for PASI 90, PASI 100, Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA), and quality-of-life measures.

“There is a clear early separation of guselkumab from adalimumab, sustained over time, curves staying flat, responses not dropping off,” Dr. Blauvelt said in summary.

Guselkumab was dosed at 100 mg subcutaneously at weeks 0 and 4, then every 8 weeks thereafter. Adalimumab was dosed subcutaneously at 80 mg at week 0, 40 mg at week 1, and then 40 mg every other week.

The two coprimary outcomes at week 16 in VOYAGE 1 were the guselkumab and placebo groups’ rates of clear or almost clear skin as defined by an IGA score of 0 or 1, and their PASI 90 response rates. An IGA of 0 or 1 was achieved by 85.1% of the guselkumab group compared with 6.9% on placebo. The week-16 PASI 90 rates – a “high bar” Dr. Blauvelt noted – were 73.3% and 2.9%, respectively.

“Clearly we’re now in an era where PASI 90 is the new PASI 75,” said session cochair Lajos Kemény, MD, professor and chairman of the department of dermatology and allergology at the University of Szeged, Hungary.

Guselkumab is a human monoclonal antibody directed at the p-19 subunit of interleukin-23, thereby preventing the inflammatory cytokine from binding to its receptor. In contrast, ustekinumab (Stelara) blocks both IL-23 and IL-12. Given that ustekinumab has established an excellent long-term safety record in PSOLAR, the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry, it stands to reason that guselkumab should have a favorable safety profile, too, since it targets only one of the two cytokines (J Drugs Dermatol. 2015 Jul;14[7]:706-14). And this indeed proved to be the case through 48 weeks in VOYAGE 1, according to Dr. Blauvelt.

Infections treated with antibiotics occurred in 6.1% of the guselkumab group, 7.2% of patients on adalimumab, and 7.5% on placebo. Mild to moderate injection site reactions occurred in 2.4% of patients on guselkumab and 7.5% on adalimumab. One patient on each of the biologics experienced an acute MI. Two malignancies occurred, both in the guselkumab group. One was prostate cancer, the other was a case of male breast cancer in a patient with a breast mass present at enrollment.

Results of two additional pivotal phase III trials, VOYAGE 2 and NAVIGATE, will be presented at future meetings. NAVIGATE is looking specifically at guselkumab’s performance in psoriasis patients with an inadequate response to ustekinumab.

“Those results look promising. It appears that patients who didn’t clear adequately on ustekinumab do well on guselkumab,” Dr. Blauvelt said in response to an audience question.

A phase II study of guselkumab in treating moderate to severe psoriatic arthritis is ongoing.

VOYAGE 1 was funded by Janssen, which is developing guselkumab. Dr. Blauvelt reported receiving research grants from and serving as a scientific consultant to Janssen and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

VIENNA – The investigational interleukin-23 inhibitor guselkumab decisively outperformed adalimumab in a head-to-head comparison for treatment of moderate or severe plaque psoriasis in the pivotal VOYAGE 1 study, Andrew Blauvelt, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

VOYAGE 1 was a 48-week, multicenter, international phase III trial in which 837 patients were randomized 2:2:1 to guselkumab, adalimumab (Humira), or placebo, with the placebo group switched to guselkumab at 16 weeks. Roughly three-quarters of patients had moderate psoriasis, the rest had severe disease. One in five had previously been treated with biologic agents; the only biologic disallowed was adalimumab.

The primary endpoints required by regulatory agencies involved efficacy comparisons between guselkumab and placebo at 16 weeks. Those results were a foregone conclusion. Far more arresting were the prespecified secondary endpoints comparing guselkumab to adalimumab at 24 and 48 weeks.

“These are very exciting results. We’re seeing efficacy in this trial that has not ever been seen before in a phase III study,” said Dr. Blauvelt, president of the Oregon Medical Research Center in Portland.

Take, for example, an efficacy yardstick dermatologists are quite familiar with: the PASI 75 response, defined as at least a 75% improvement from baseline in the Psoriasis Area Severity Index score, which averaged 22 at baseline in this trial. The PASI 75 rate in guselkumab-treated patients was 91.2% at 16 weeks, remained at 91.2% at 24 weeks, and was 87.8% at week 48.

“To my knowledge this is the highest PASI 75 response rate that’s been seen in a phase III study of any biologic in psoriasis,” the dermatologist said.

The PASI 75 rates with adalimumab, a tumor necrosis factor–alpha blocker widely prescribed for psoriasis, were markedly lower, although just a few years ago they would have been considered stratospheric: 73.1% at 16 weeks, 72.2% at 24 weeks, and 62.6% at 48 weeks.

The same pattern held for PASI 90, PASI 100, Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA), and quality-of-life measures.

“There is a clear early separation of guselkumab from adalimumab, sustained over time, curves staying flat, responses not dropping off,” Dr. Blauvelt said in summary.

Guselkumab was dosed at 100 mg subcutaneously at weeks 0 and 4, then every 8 weeks thereafter. Adalimumab was dosed subcutaneously at 80 mg at week 0, 40 mg at week 1, and then 40 mg every other week.

The two coprimary outcomes at week 16 in VOYAGE 1 were the guselkumab and placebo groups’ rates of clear or almost clear skin as defined by an IGA score of 0 or 1, and their PASI 90 response rates. An IGA of 0 or 1 was achieved by 85.1% of the guselkumab group compared with 6.9% on placebo. The week-16 PASI 90 rates – a “high bar” Dr. Blauvelt noted – were 73.3% and 2.9%, respectively.

“Clearly we’re now in an era where PASI 90 is the new PASI 75,” said session cochair Lajos Kemény, MD, professor and chairman of the department of dermatology and allergology at the University of Szeged, Hungary.

Guselkumab is a human monoclonal antibody directed at the p-19 subunit of interleukin-23, thereby preventing the inflammatory cytokine from binding to its receptor. In contrast, ustekinumab (Stelara) blocks both IL-23 and IL-12. Given that ustekinumab has established an excellent long-term safety record in PSOLAR, the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry, it stands to reason that guselkumab should have a favorable safety profile, too, since it targets only one of the two cytokines (J Drugs Dermatol. 2015 Jul;14[7]:706-14). And this indeed proved to be the case through 48 weeks in VOYAGE 1, according to Dr. Blauvelt.

Infections treated with antibiotics occurred in 6.1% of the guselkumab group, 7.2% of patients on adalimumab, and 7.5% on placebo. Mild to moderate injection site reactions occurred in 2.4% of patients on guselkumab and 7.5% on adalimumab. One patient on each of the biologics experienced an acute MI. Two malignancies occurred, both in the guselkumab group. One was prostate cancer, the other was a case of male breast cancer in a patient with a breast mass present at enrollment.

Results of two additional pivotal phase III trials, VOYAGE 2 and NAVIGATE, will be presented at future meetings. NAVIGATE is looking specifically at guselkumab’s performance in psoriasis patients with an inadequate response to ustekinumab.

“Those results look promising. It appears that patients who didn’t clear adequately on ustekinumab do well on guselkumab,” Dr. Blauvelt said in response to an audience question.

A phase II study of guselkumab in treating moderate to severe psoriatic arthritis is ongoing.

VOYAGE 1 was funded by Janssen, which is developing guselkumab. Dr. Blauvelt reported receiving research grants from and serving as a scientific consultant to Janssen and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The PASI 90 response rate at 24 weeks was 80% in psoriasis patients on guselkumab compared with 53% in those on adalimumab.

Data source: A randomized, multinational, 48-week, pivotal phase III clinical trial involving 837 psoriasis patients assigned to guselkumab, adalimumab, or placebo.

Disclosures: The VOYAGE 1 trial was funded by Janssen, which is developing guselkumab. The study presenter reported receiving research grants from and serving as a scientific consultant to Janssen and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

Birth outcomes unaffected by paternal immunosuppressive therapy

VIENNA – The use of classic systemic immunosuppressive agents by men in the months shortly before conception was not associated with increased risk of low birthweight, preterm birth, or congenital anomalies in their offspring in a large Danish national registry.

“We didn’t see any real safety signals,” Dr. Alexander Egeberg reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

He and his coinvestigators at the University of Copenhagen decided to examine this issue for a simple reason: “We know quite a lot from registry studies about the safety of these drugs when used by women during pregnancy, but very little about the safety of paternal use,” Dr. Egeberg explained.

Methotrexate, azathioprine, and cyclosporine are often prescribed for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis as well as other chronic inflammatory disorders. Female patients are typically told to stop using these medications if they’re trying to become pregnant, or as soon as they think they might be pregnant, but nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended.

Using linked comprehensive national Danish databases, the investigators scrutinized the medical records of all children born in Denmark during 2004-2010, as well as those of their parents. They identified 2,235 children whose fathers had been on immunosuppressive therapy for a medical condition at any time prior to conception. There were 1,246 fathers who had been on azathioprine, 848 on methotrexate, and 141 on cyclosporine.

Rates of preterm birth, congenital anomalies, and low birthweight were compared in children born to fathers using immunosuppression and in 415,589 children born to fathers with no history of exposure to the medications. These comparisons entailed multivariate regression analyses adjusted for maternal age, parity, smoking status, and the child’s gender. Dr. Egeberg and his colleagues also compared rates of these reproductive complications in the subgroup of children whose fathers had been on the medications within 3 months prior to the estimated time of conception and in children whose fathers had stopped taking the drugs by that point.

None of the adverse neonatal outcomes were significantly increased in ever or recent paternal users of the medications under study, with one exception. Paternal use of cyclosporine within the last 3 months prior to conception was associated with an adjusted 3.7-fold increased likelihood of having a baby with a congenital anomaly. Dr. Egeberg, however, was quick to state that this finding was based on small numbers of exposures: 18 paternal exposures and four affected offspring.

“The cyclosporine finding should be interpreted quite cautiously,” he emphasized.

The reproductive outcomes study was supported by Danish governmental research funds. Dr. Egeberg reported having received research funding from and serving as a consultant to Pfizer and Eli Lilly.

VIENNA – The use of classic systemic immunosuppressive agents by men in the months shortly before conception was not associated with increased risk of low birthweight, preterm birth, or congenital anomalies in their offspring in a large Danish national registry.

“We didn’t see any real safety signals,” Dr. Alexander Egeberg reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

He and his coinvestigators at the University of Copenhagen decided to examine this issue for a simple reason: “We know quite a lot from registry studies about the safety of these drugs when used by women during pregnancy, but very little about the safety of paternal use,” Dr. Egeberg explained.

Methotrexate, azathioprine, and cyclosporine are often prescribed for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis as well as other chronic inflammatory disorders. Female patients are typically told to stop using these medications if they’re trying to become pregnant, or as soon as they think they might be pregnant, but nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended.

Using linked comprehensive national Danish databases, the investigators scrutinized the medical records of all children born in Denmark during 2004-2010, as well as those of their parents. They identified 2,235 children whose fathers had been on immunosuppressive therapy for a medical condition at any time prior to conception. There were 1,246 fathers who had been on azathioprine, 848 on methotrexate, and 141 on cyclosporine.

Rates of preterm birth, congenital anomalies, and low birthweight were compared in children born to fathers using immunosuppression and in 415,589 children born to fathers with no history of exposure to the medications. These comparisons entailed multivariate regression analyses adjusted for maternal age, parity, smoking status, and the child’s gender. Dr. Egeberg and his colleagues also compared rates of these reproductive complications in the subgroup of children whose fathers had been on the medications within 3 months prior to the estimated time of conception and in children whose fathers had stopped taking the drugs by that point.

None of the adverse neonatal outcomes were significantly increased in ever or recent paternal users of the medications under study, with one exception. Paternal use of cyclosporine within the last 3 months prior to conception was associated with an adjusted 3.7-fold increased likelihood of having a baby with a congenital anomaly. Dr. Egeberg, however, was quick to state that this finding was based on small numbers of exposures: 18 paternal exposures and four affected offspring.

“The cyclosporine finding should be interpreted quite cautiously,” he emphasized.

The reproductive outcomes study was supported by Danish governmental research funds. Dr. Egeberg reported having received research funding from and serving as a consultant to Pfizer and Eli Lilly.

VIENNA – The use of classic systemic immunosuppressive agents by men in the months shortly before conception was not associated with increased risk of low birthweight, preterm birth, or congenital anomalies in their offspring in a large Danish national registry.

“We didn’t see any real safety signals,” Dr. Alexander Egeberg reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

He and his coinvestigators at the University of Copenhagen decided to examine this issue for a simple reason: “We know quite a lot from registry studies about the safety of these drugs when used by women during pregnancy, but very little about the safety of paternal use,” Dr. Egeberg explained.

Methotrexate, azathioprine, and cyclosporine are often prescribed for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis as well as other chronic inflammatory disorders. Female patients are typically told to stop using these medications if they’re trying to become pregnant, or as soon as they think they might be pregnant, but nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended.

Using linked comprehensive national Danish databases, the investigators scrutinized the medical records of all children born in Denmark during 2004-2010, as well as those of their parents. They identified 2,235 children whose fathers had been on immunosuppressive therapy for a medical condition at any time prior to conception. There were 1,246 fathers who had been on azathioprine, 848 on methotrexate, and 141 on cyclosporine.

Rates of preterm birth, congenital anomalies, and low birthweight were compared in children born to fathers using immunosuppression and in 415,589 children born to fathers with no history of exposure to the medications. These comparisons entailed multivariate regression analyses adjusted for maternal age, parity, smoking status, and the child’s gender. Dr. Egeberg and his colleagues also compared rates of these reproductive complications in the subgroup of children whose fathers had been on the medications within 3 months prior to the estimated time of conception and in children whose fathers had stopped taking the drugs by that point.

None of the adverse neonatal outcomes were significantly increased in ever or recent paternal users of the medications under study, with one exception. Paternal use of cyclosporine within the last 3 months prior to conception was associated with an adjusted 3.7-fold increased likelihood of having a baby with a congenital anomaly. Dr. Egeberg, however, was quick to state that this finding was based on small numbers of exposures: 18 paternal exposures and four affected offspring.

“The cyclosporine finding should be interpreted quite cautiously,” he emphasized.

The reproductive outcomes study was supported by Danish governmental research funds. Dr. Egeberg reported having received research funding from and serving as a consultant to Pfizer and Eli Lilly.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Adjusted rates of congenital anomalies, preterm birth, and low birthweight are not increased in children with paternal use of azathioprine, methotrexate, or cyclosporine prior to conception.

Data source: This retrospective study utilized linked Danish national registries to compare rates of low birthweight, congenital anomalies, and preterm birth in all Danish children born in 2004-2010 depending upon whether or not the father had been on methotrexate, azathioprine, or cyclosporine prior to the pregnancy.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Danish governmental research funds. Dr. Egeberg reported having received research funding from, and serving as a consultant to, Pfizer and Eli Lilly.

Debunking Psoriasis Myths: Does UVB Phototherapy Cause Skin Cancer?

Myth: UVB phototherapy causes skin cancer

Phototherapy is a common treatment modality for psoriasis patients that can be used in the physician’s office or psoriasis clinic or at home. Options include UVB phototherapy (broadband and narrowband), which slows the growth of affected skin cells; psoralen plus UVA (PUVA), which slows excessive skin cell growth; and excimer laser therapy, which targets select areas of the skin affected by mild to moderate psoriasis and is particularly useful for scalp psoriasis. Each of these therapies may be combined with other topical and/or systemic psoriasis treatments. The effects of UV light on the skin and the connection to skin cancer is widely known. Therefore, patient education on the risk for skin cancer with phototherapy is essential.

Evidence suggests that UVB phototherapy remains a safe treatment modality. In a 2005 analysis of prospective and retrospective studies on skin cancer risk from UVB phototherapy, 11 studies (10 concerning psoriasis patients) were reviewed and the researchers concluded that all studies eventually showed no increased skin cancer risk with UVB phototherapy. One of the PUVA cohort studies examined genital skin cancers and found an increased rate of genital tumors associated with UVB phototherapy.

Another analysis to define the long-term carcinogenic risk for narrowband UVB treatment found that there was no association between narrowband UVB exposure alone (without PUVA) and any skin cancer. For patients treated with narrowband UVB and PUVA, there was a small increase in basal cell carcinomas.

Dermatologists should monitor psoriasis patients for self-administered treatment with tanning beds. Based on a questionnaire sent to approximately 14,000 subscribers of National Psoriasis Foundation emails, 62% of 617 tanners started tanning to treat psoriasis; they were more likely to have received medical phototherapy and had more severe psoriasis. Approximately 30% of these patients indicated that they used tanning as a self-treatment for psoriasis because of the inconvenience and cost of UV light treatment in a physician’s office as well as treatment failure of other therapies prescribed by the physician. “Our results imply that tanning bed usage among psoriasis sufferers is widespread and linked with tanning addiction,” reported Felton et al. “Practitioners should be particularly vigilant to the possibility of tanning bed usage in at-risk patients.” These patients may be at increased risk for skin cancer. Problematic tanning behaviors may be seen in younger female patients diagnosed with psoriasis at an early age as well as patients with severe psoriasis who were previously prescribed phototherapy treatment.

Expert Commentary on next page

Expert Commentary

UVB phototherapy is an effective therapy that does not increase the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), according to the 2 analyses mentioned above. When I discuss the risks and benefits of UVB phototherapy with psoriasis patients, I do say that there is a theoretical increased risk for NMSC but that the 2005 study mentioned above does not indicate an increased risk. However, UVB phototherapy and cyclosporine should not be combined, as this combination does increase the risk for NMSC.

Psoralen plus UVA definitely will increase the risk for NMSC, particularly squamous cell carcinoma. However, in this age of the biologics, PUVA use has fallen out of favor, partly due to the increased risk for NMSC, and many patients will not encounter dermatology practices that still use PUVA.

—Jashin J. Wu, MD (Los Angeles, California)

Felton S, Adinoff B, Jeon-Slaughter H, et al. The significant health threat from tanning bed use as a self-treatment for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1015-1017.

Hearn RM, Kerr AC, Rahim KF, et al. Incidence of skin cancers in 3867 patients treated with narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:931-935.

Lee E, Koo J, Berger T. UVB phototherapy and skin cancer risk: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:355-360.

Phototherapy. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/phototherapy . Accessed October 4, 2016.

Myth: UVB phototherapy causes skin cancer

Phototherapy is a common treatment modality for psoriasis patients that can be used in the physician’s office or psoriasis clinic or at home. Options include UVB phototherapy (broadband and narrowband), which slows the growth of affected skin cells; psoralen plus UVA (PUVA), which slows excessive skin cell growth; and excimer laser therapy, which targets select areas of the skin affected by mild to moderate psoriasis and is particularly useful for scalp psoriasis. Each of these therapies may be combined with other topical and/or systemic psoriasis treatments. The effects of UV light on the skin and the connection to skin cancer is widely known. Therefore, patient education on the risk for skin cancer with phototherapy is essential.

Evidence suggests that UVB phototherapy remains a safe treatment modality. In a 2005 analysis of prospective and retrospective studies on skin cancer risk from UVB phototherapy, 11 studies (10 concerning psoriasis patients) were reviewed and the researchers concluded that all studies eventually showed no increased skin cancer risk with UVB phototherapy. One of the PUVA cohort studies examined genital skin cancers and found an increased rate of genital tumors associated with UVB phototherapy.

Another analysis to define the long-term carcinogenic risk for narrowband UVB treatment found that there was no association between narrowband UVB exposure alone (without PUVA) and any skin cancer. For patients treated with narrowband UVB and PUVA, there was a small increase in basal cell carcinomas.

Dermatologists should monitor psoriasis patients for self-administered treatment with tanning beds. Based on a questionnaire sent to approximately 14,000 subscribers of National Psoriasis Foundation emails, 62% of 617 tanners started tanning to treat psoriasis; they were more likely to have received medical phototherapy and had more severe psoriasis. Approximately 30% of these patients indicated that they used tanning as a self-treatment for psoriasis because of the inconvenience and cost of UV light treatment in a physician’s office as well as treatment failure of other therapies prescribed by the physician. “Our results imply that tanning bed usage among psoriasis sufferers is widespread and linked with tanning addiction,” reported Felton et al. “Practitioners should be particularly vigilant to the possibility of tanning bed usage in at-risk patients.” These patients may be at increased risk for skin cancer. Problematic tanning behaviors may be seen in younger female patients diagnosed with psoriasis at an early age as well as patients with severe psoriasis who were previously prescribed phototherapy treatment.

Expert Commentary on next page

Expert Commentary

UVB phototherapy is an effective therapy that does not increase the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), according to the 2 analyses mentioned above. When I discuss the risks and benefits of UVB phototherapy with psoriasis patients, I do say that there is a theoretical increased risk for NMSC but that the 2005 study mentioned above does not indicate an increased risk. However, UVB phototherapy and cyclosporine should not be combined, as this combination does increase the risk for NMSC.

Psoralen plus UVA definitely will increase the risk for NMSC, particularly squamous cell carcinoma. However, in this age of the biologics, PUVA use has fallen out of favor, partly due to the increased risk for NMSC, and many patients will not encounter dermatology practices that still use PUVA.

—Jashin J. Wu, MD (Los Angeles, California)

Myth: UVB phototherapy causes skin cancer

Phototherapy is a common treatment modality for psoriasis patients that can be used in the physician’s office or psoriasis clinic or at home. Options include UVB phototherapy (broadband and narrowband), which slows the growth of affected skin cells; psoralen plus UVA (PUVA), which slows excessive skin cell growth; and excimer laser therapy, which targets select areas of the skin affected by mild to moderate psoriasis and is particularly useful for scalp psoriasis. Each of these therapies may be combined with other topical and/or systemic psoriasis treatments. The effects of UV light on the skin and the connection to skin cancer is widely known. Therefore, patient education on the risk for skin cancer with phototherapy is essential.

Evidence suggests that UVB phototherapy remains a safe treatment modality. In a 2005 analysis of prospective and retrospective studies on skin cancer risk from UVB phototherapy, 11 studies (10 concerning psoriasis patients) were reviewed and the researchers concluded that all studies eventually showed no increased skin cancer risk with UVB phototherapy. One of the PUVA cohort studies examined genital skin cancers and found an increased rate of genital tumors associated with UVB phototherapy.

Another analysis to define the long-term carcinogenic risk for narrowband UVB treatment found that there was no association between narrowband UVB exposure alone (without PUVA) and any skin cancer. For patients treated with narrowband UVB and PUVA, there was a small increase in basal cell carcinomas.

Dermatologists should monitor psoriasis patients for self-administered treatment with tanning beds. Based on a questionnaire sent to approximately 14,000 subscribers of National Psoriasis Foundation emails, 62% of 617 tanners started tanning to treat psoriasis; they were more likely to have received medical phototherapy and had more severe psoriasis. Approximately 30% of these patients indicated that they used tanning as a self-treatment for psoriasis because of the inconvenience and cost of UV light treatment in a physician’s office as well as treatment failure of other therapies prescribed by the physician. “Our results imply that tanning bed usage among psoriasis sufferers is widespread and linked with tanning addiction,” reported Felton et al. “Practitioners should be particularly vigilant to the possibility of tanning bed usage in at-risk patients.” These patients may be at increased risk for skin cancer. Problematic tanning behaviors may be seen in younger female patients diagnosed with psoriasis at an early age as well as patients with severe psoriasis who were previously prescribed phototherapy treatment.

Expert Commentary on next page

Expert Commentary

UVB phototherapy is an effective therapy that does not increase the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), according to the 2 analyses mentioned above. When I discuss the risks and benefits of UVB phototherapy with psoriasis patients, I do say that there is a theoretical increased risk for NMSC but that the 2005 study mentioned above does not indicate an increased risk. However, UVB phototherapy and cyclosporine should not be combined, as this combination does increase the risk for NMSC.

Psoralen plus UVA definitely will increase the risk for NMSC, particularly squamous cell carcinoma. However, in this age of the biologics, PUVA use has fallen out of favor, partly due to the increased risk for NMSC, and many patients will not encounter dermatology practices that still use PUVA.

—Jashin J. Wu, MD (Los Angeles, California)

Felton S, Adinoff B, Jeon-Slaughter H, et al. The significant health threat from tanning bed use as a self-treatment for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1015-1017.

Hearn RM, Kerr AC, Rahim KF, et al. Incidence of skin cancers in 3867 patients treated with narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:931-935.

Lee E, Koo J, Berger T. UVB phototherapy and skin cancer risk: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:355-360.

Phototherapy. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/phototherapy . Accessed October 4, 2016.

Felton S, Adinoff B, Jeon-Slaughter H, et al. The significant health threat from tanning bed use as a self-treatment for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1015-1017.

Hearn RM, Kerr AC, Rahim KF, et al. Incidence of skin cancers in 3867 patients treated with narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:931-935.

Lee E, Koo J, Berger T. UVB phototherapy and skin cancer risk: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:355-360.

Phototherapy. National Psoriasis Foundation website. https://www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/phototherapy . Accessed October 4, 2016.

Presenting Treatment Safety Data: Subjective Interpretations of Objective Information

The Nuremberg Code in 1947,1 the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964,2 and the Belmont Report in 19793 were cornerstones in the establishment of ethical principles in the medical field. These documents specifically highlight the concept of informed consent, which maintains that to practice ethical medicine, physicians must fully inform patients of all therapeutic benefits and especially risks as well as treatment alternatives before they consent to therapeutic intervention. Educating patients about risks of treatment is obligatory. Risk communication involves a mutual exchange of information between physicians and patients; the physician presents risk information in an understandable manner that adequately conveys pertinent data that is critical for the patient to make an informed therapeutic decision.4

An inherent problem with risk education is that patients may be terrified about risks associated with treatment. Some patients will refuse needed treatment because of fear.5 When patients have concerns about the safety profile of a treatment regimen and potential adverse effects, they may be less compliant with treatment.6 The intelligent noncompliance phenomenon occurs when a patient knowingly makes the choice to not adhere to treatment, and concern regarding treatment risks relative to benefits is a common reason underlying this phenomenon.7,8

Behavioral economists have studied how individuals weigh risks. Kahneman and Tversky’s9 prospect theory asserts that individuals tend to overweigh unlikely risks and underweigh more certain risks, which they call the certainty effect; it is the basis of the human tendency to avoid risks in situations of likely gain and to pursue risks in situations of likely loss. The tendency to overweigh rare risks is even more pronounced for affect-rich events such as serious side effects.10 The way data are presented can affect how patients interpret the information. Context and framing of data affect patients’ perceptions.11 We describe several ways to present safety data using graphical presentation of psoriasis treatment safety data as an example and explain how each one can affect patients’ perception of treatment risks.

Approaches to Presenting Safety Data

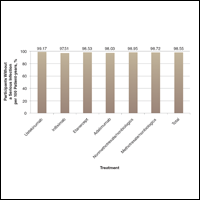

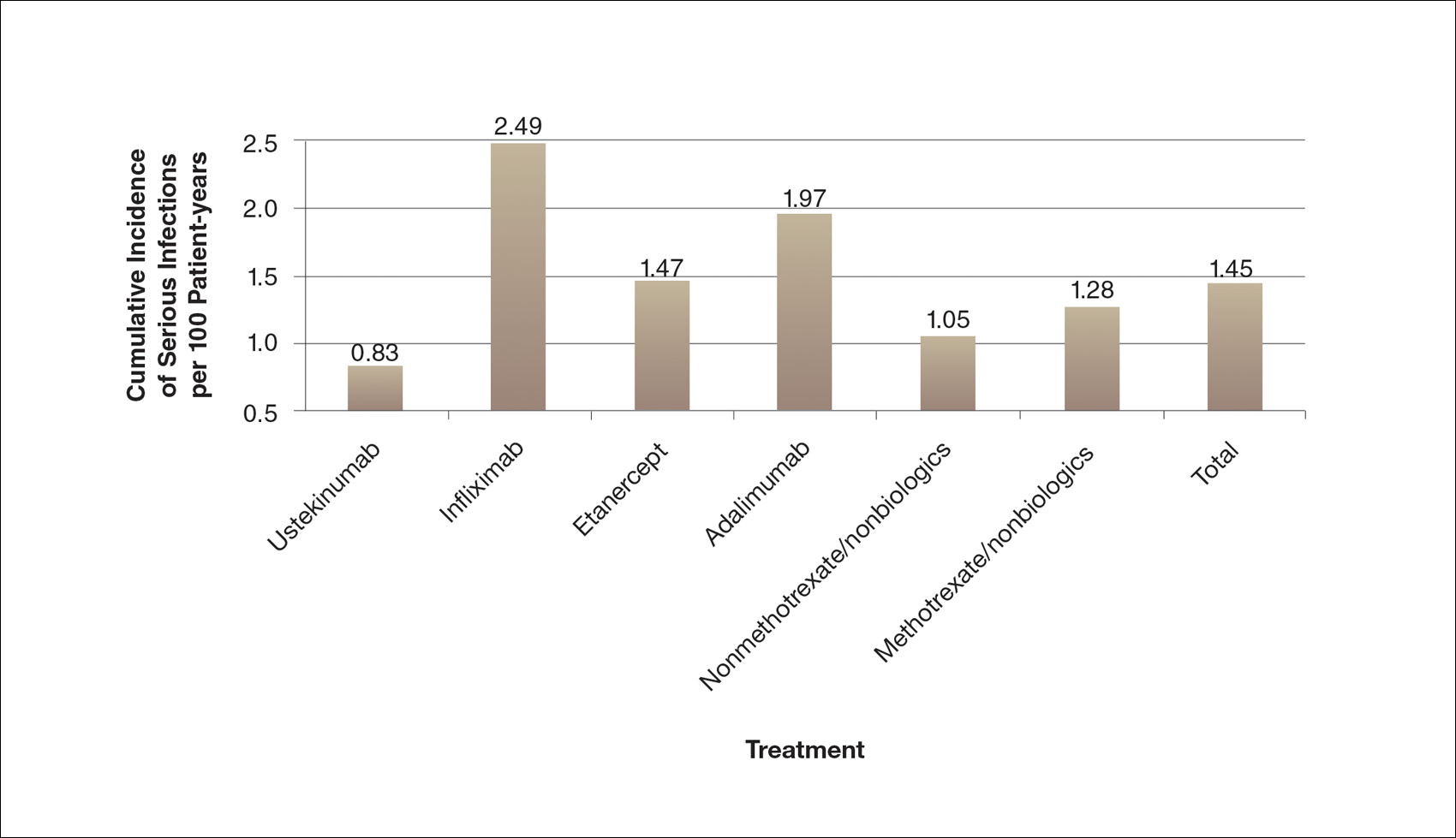

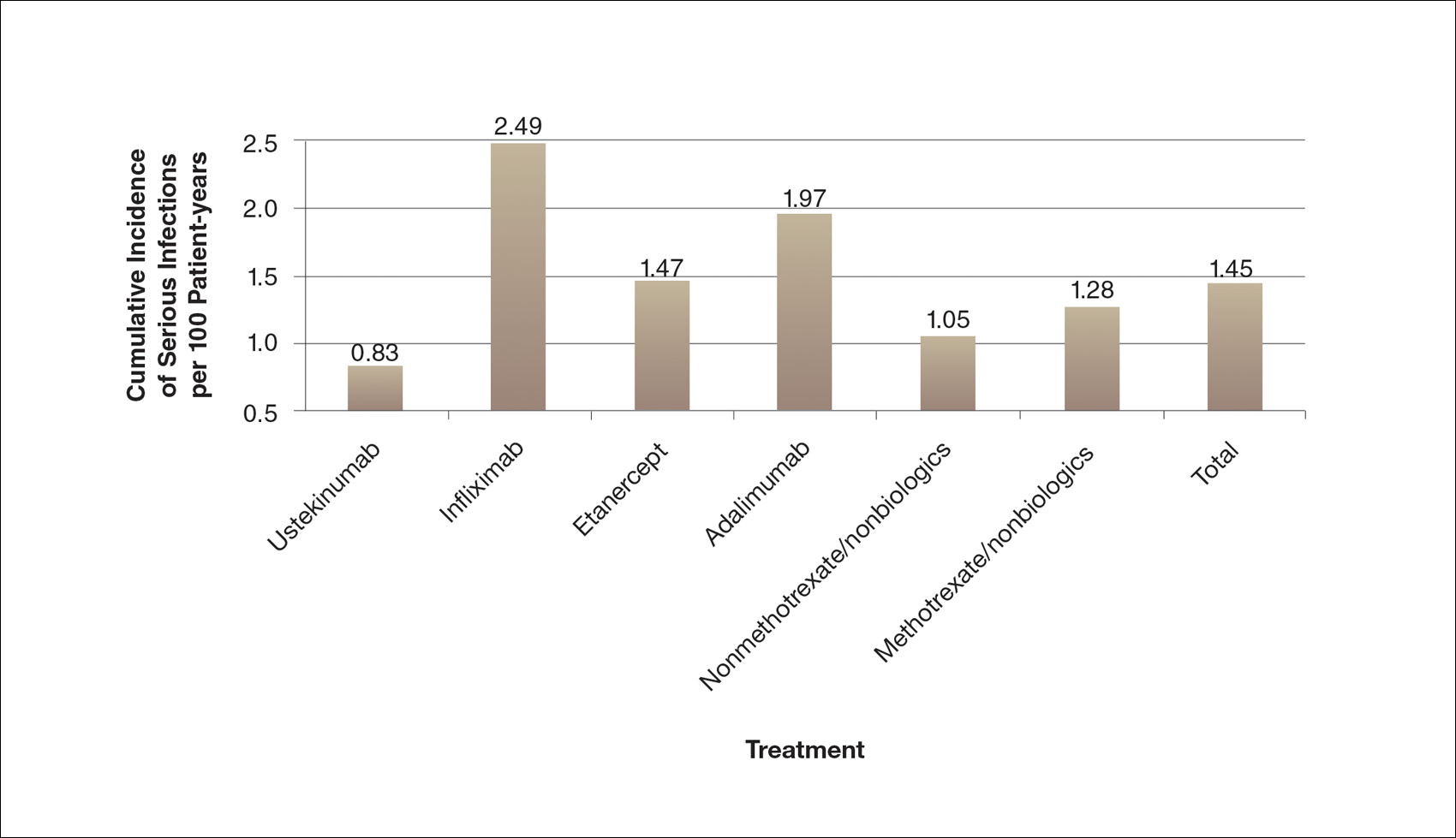

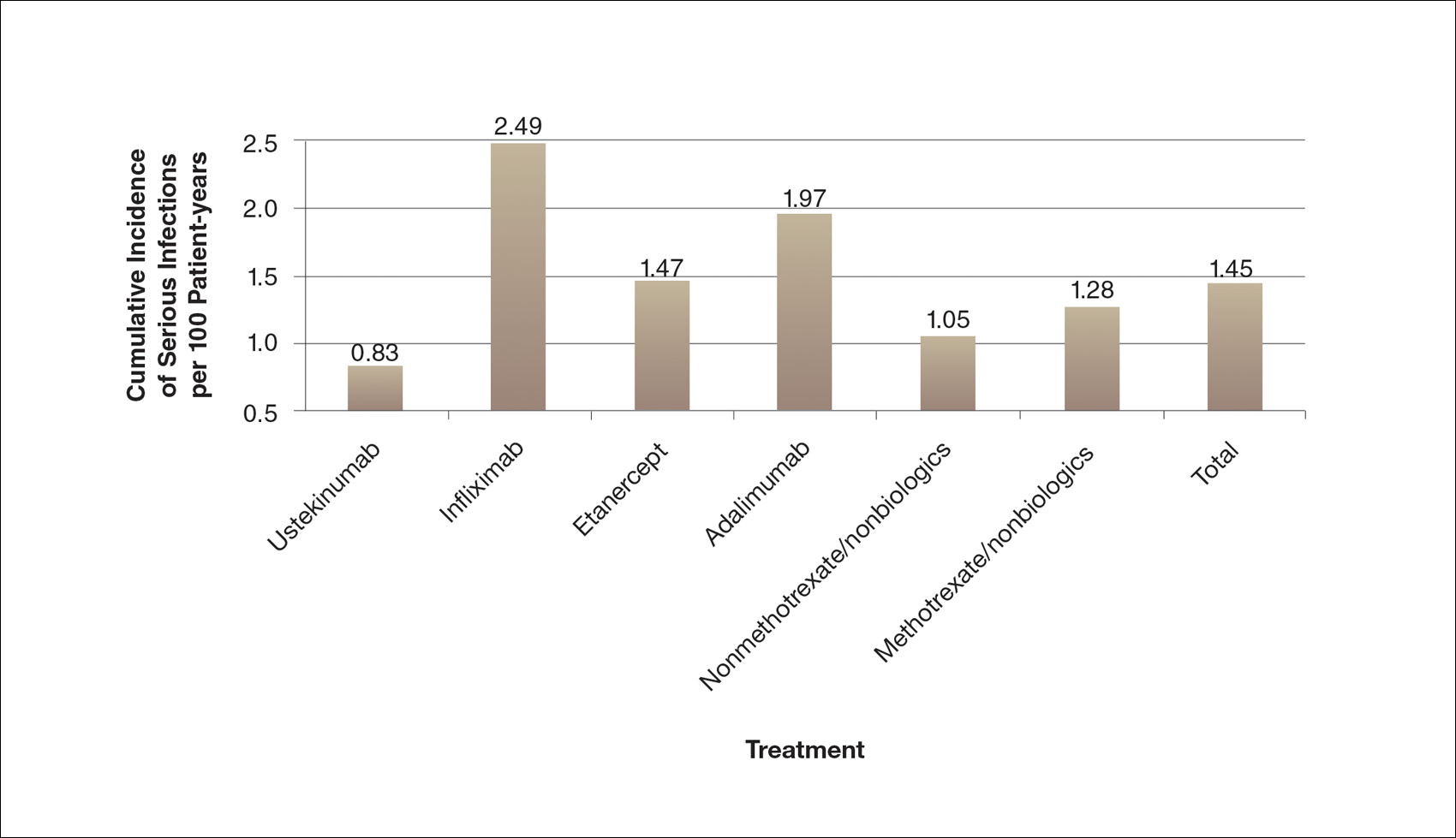

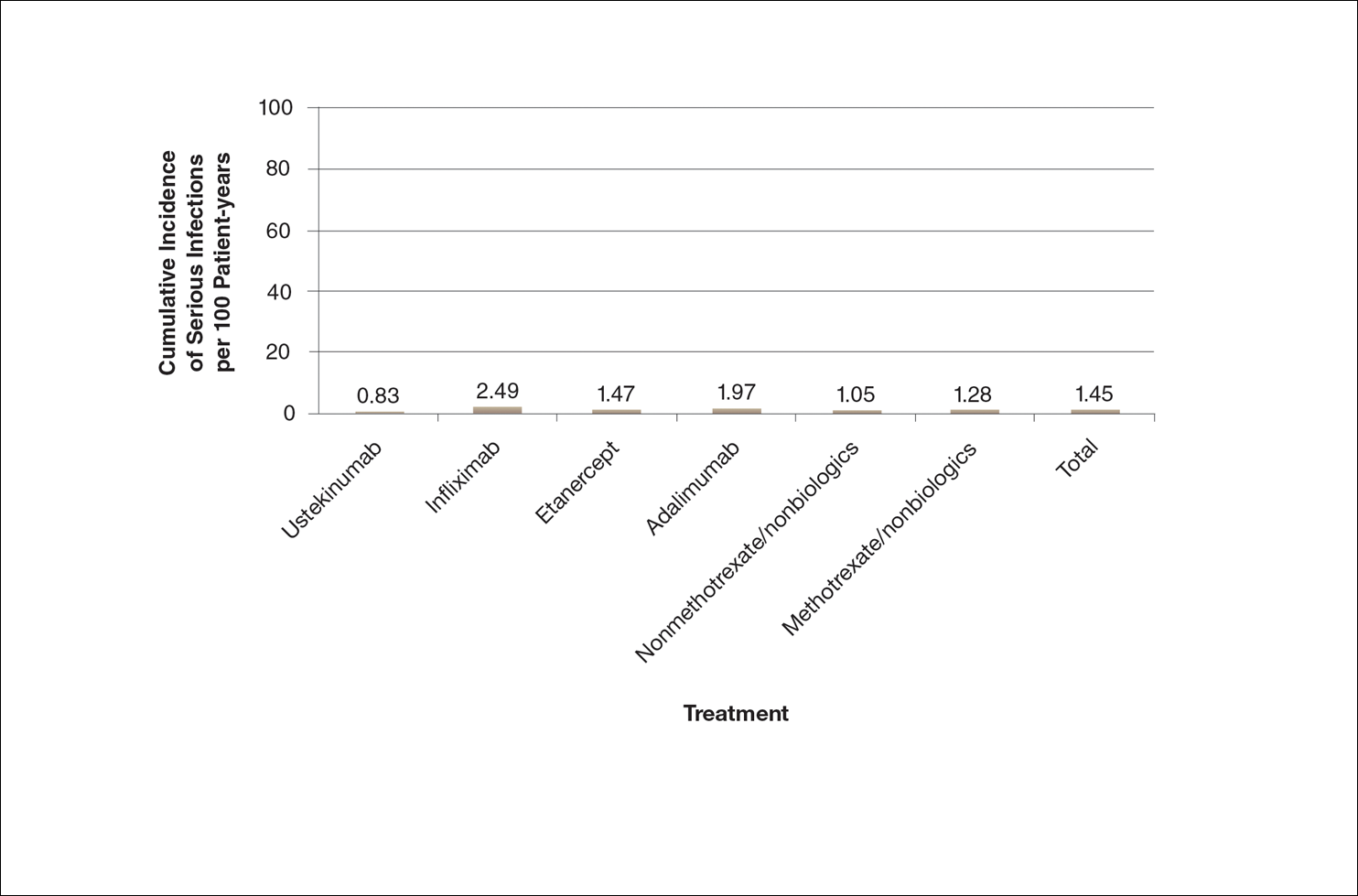

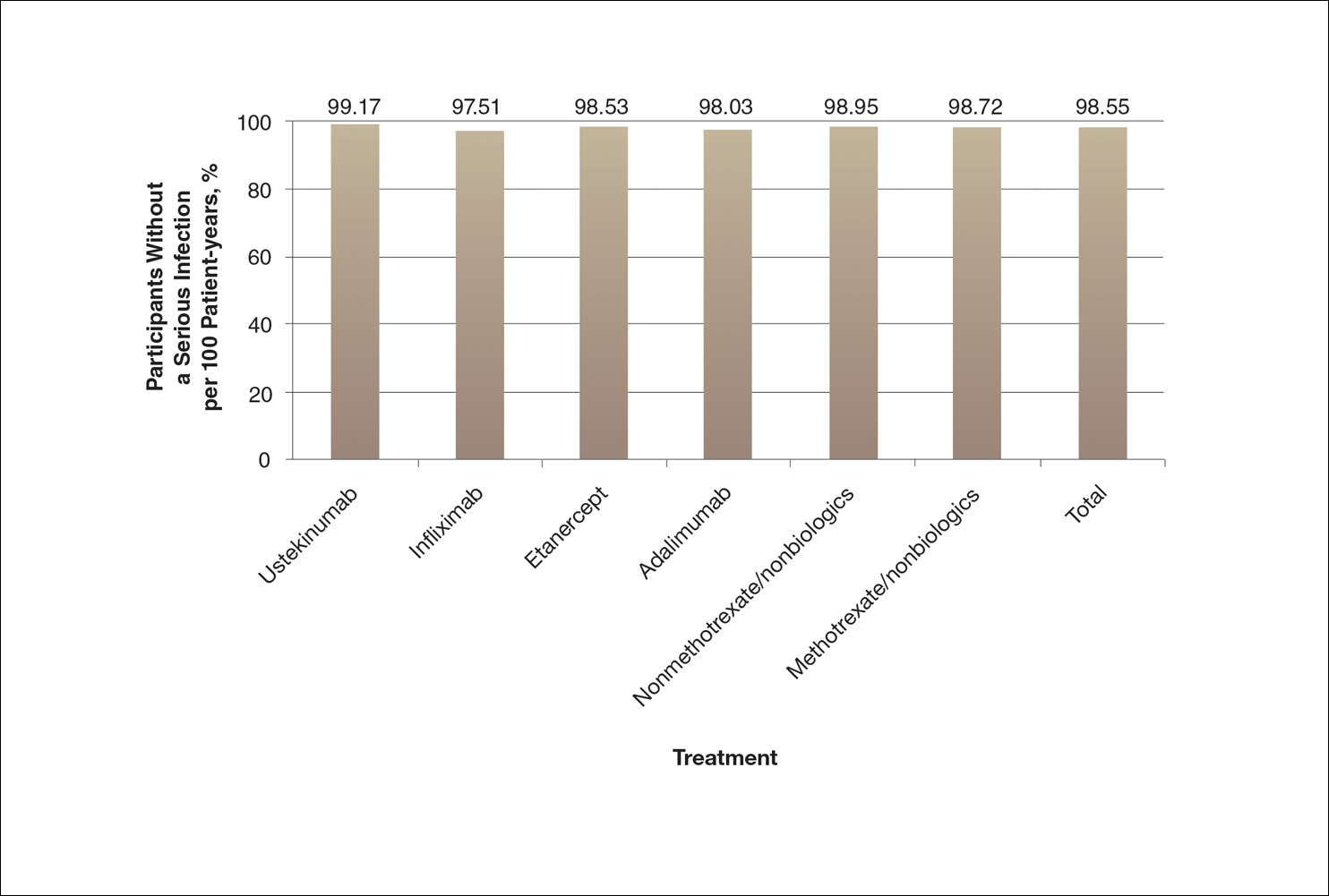

There are numerous ways to present safety data to patients, including verbal, numeric, and visual strategies.12 Many methods of presentation are a combination of these strategies. Graphs are visual strategies to further categorize and present numeric data, and physicians may choose to incorporate these aids when presenting safety information to patients. Graphical presentations give the patient a mental picture of the data. Numerous types of graphs can be constructed. Kalb et al13 determined the effect of psoriasis treatment on the risk of serious infection from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). We used the results from this study to demonstrate multiple ways of presenting safety data (Figures 1–3).

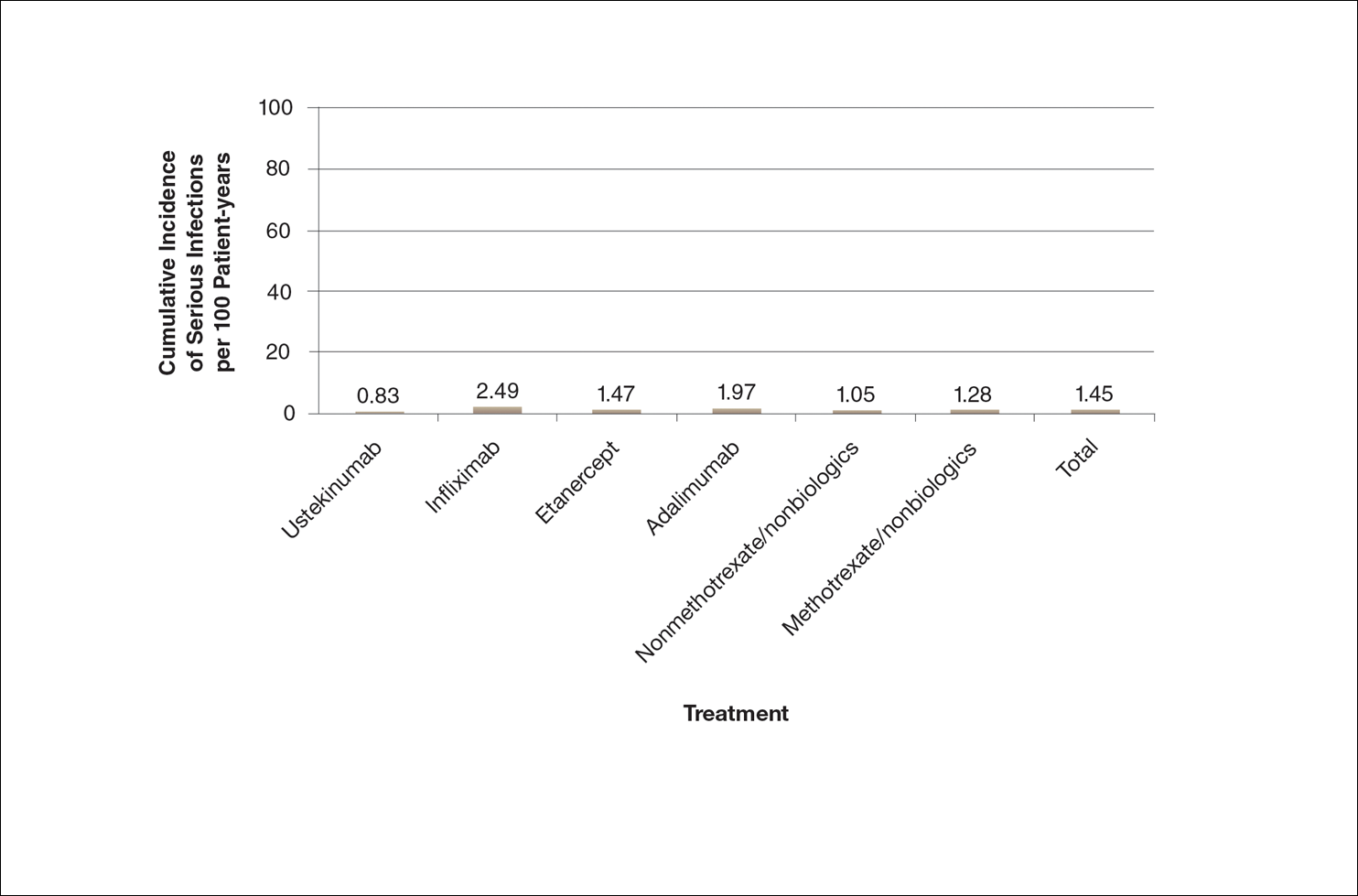

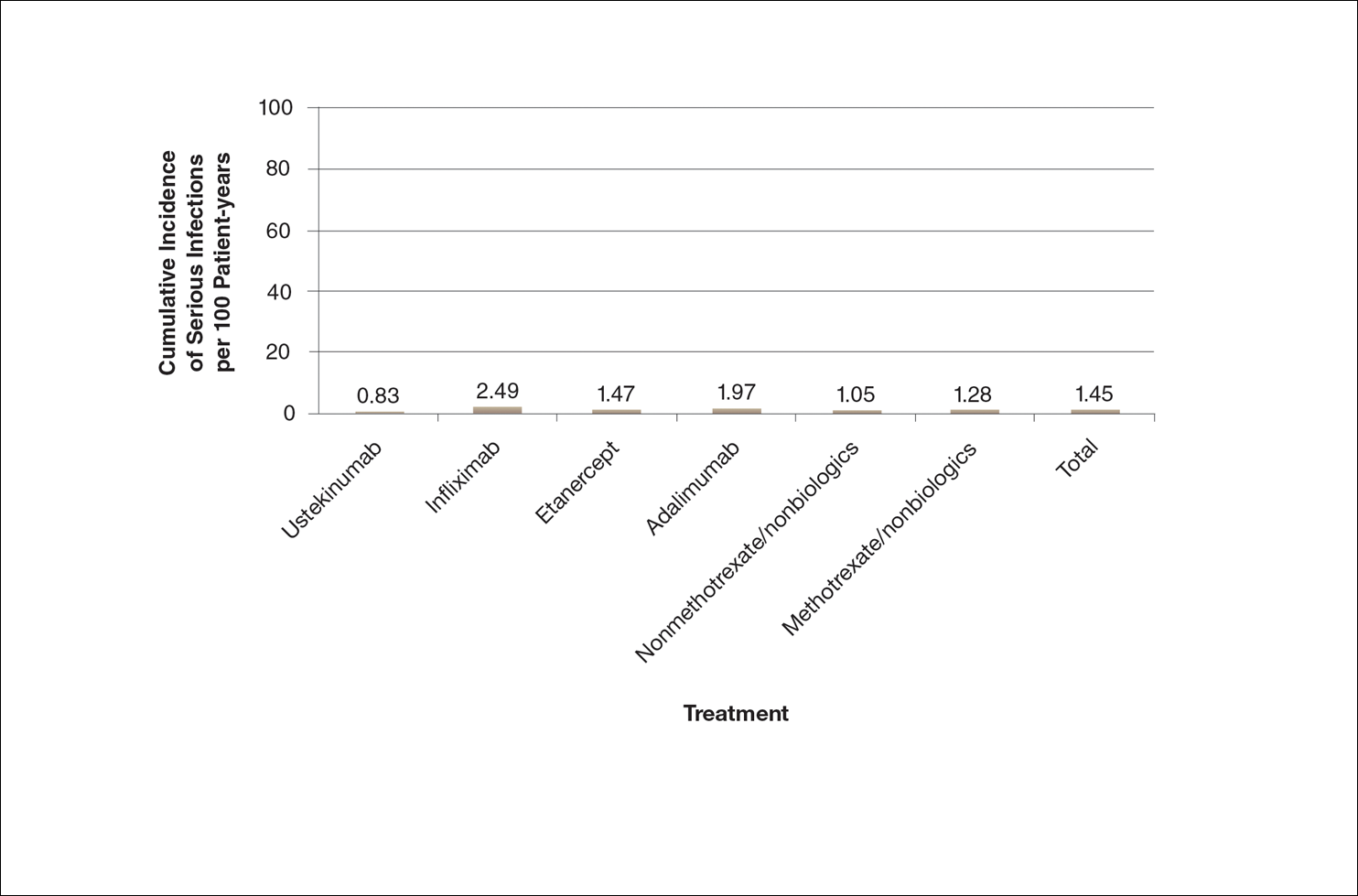

A graphical presentation with a truncated y-axis is a common approach (Figure 1). Graphs with truncated axes are sometimes used to conserve space or to accentuate certain differences in the graph that would otherwise be less obvious without the zoomed in y-axis.14 These graphs present quantitatively accurate information that can be visually misleading at the same time. Truncated axes accentuate differences, creating mental impressions that are not reflective of the magnitude of the numeric differences. Alternatively, a graph with a full y-axis includes both the maximum and minimum data values on the y-axis (Figure 2). The y-axis also extends maximally to the total number of patients or patient-years studied. This type of graph presents all of the numeric data without distortion.

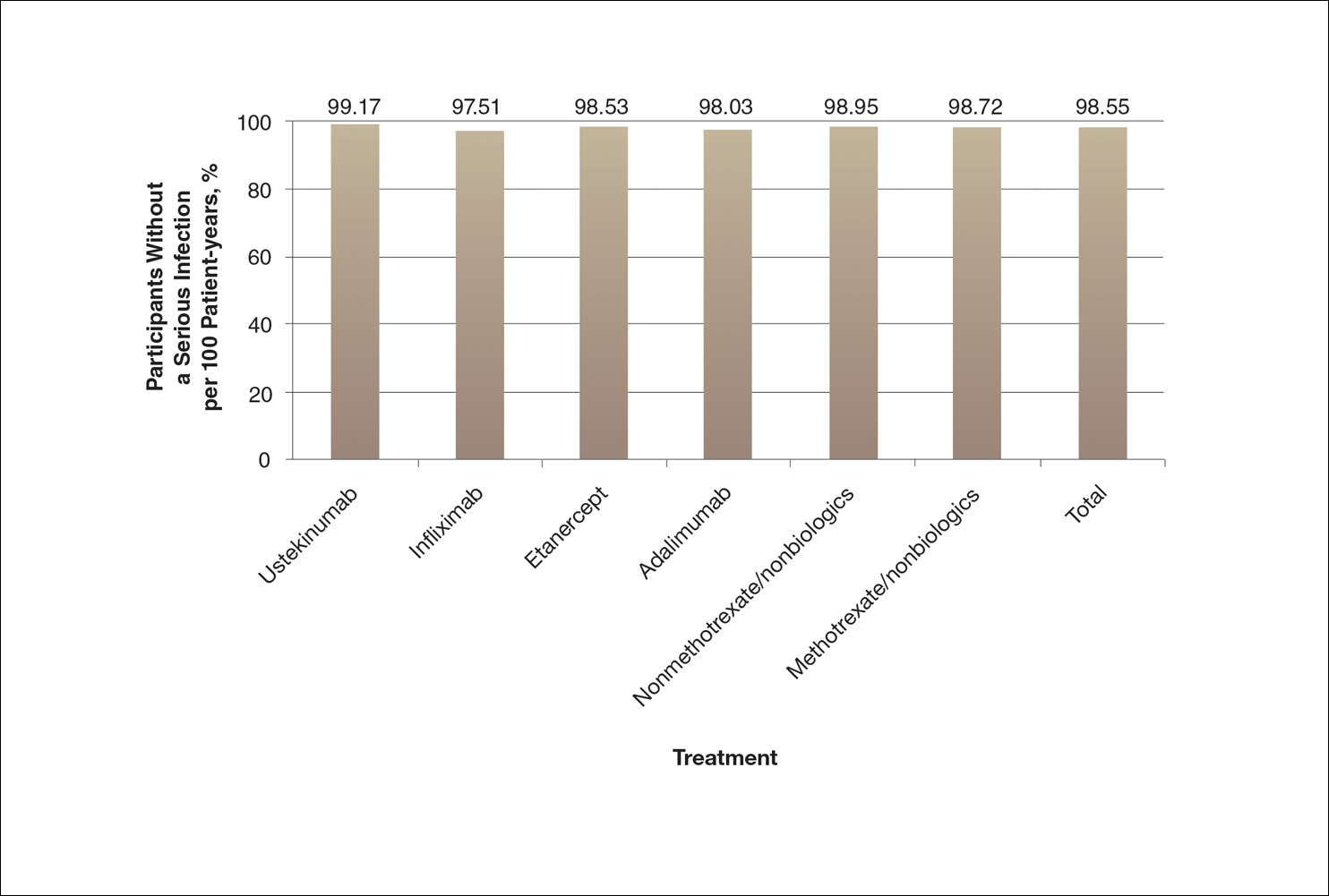

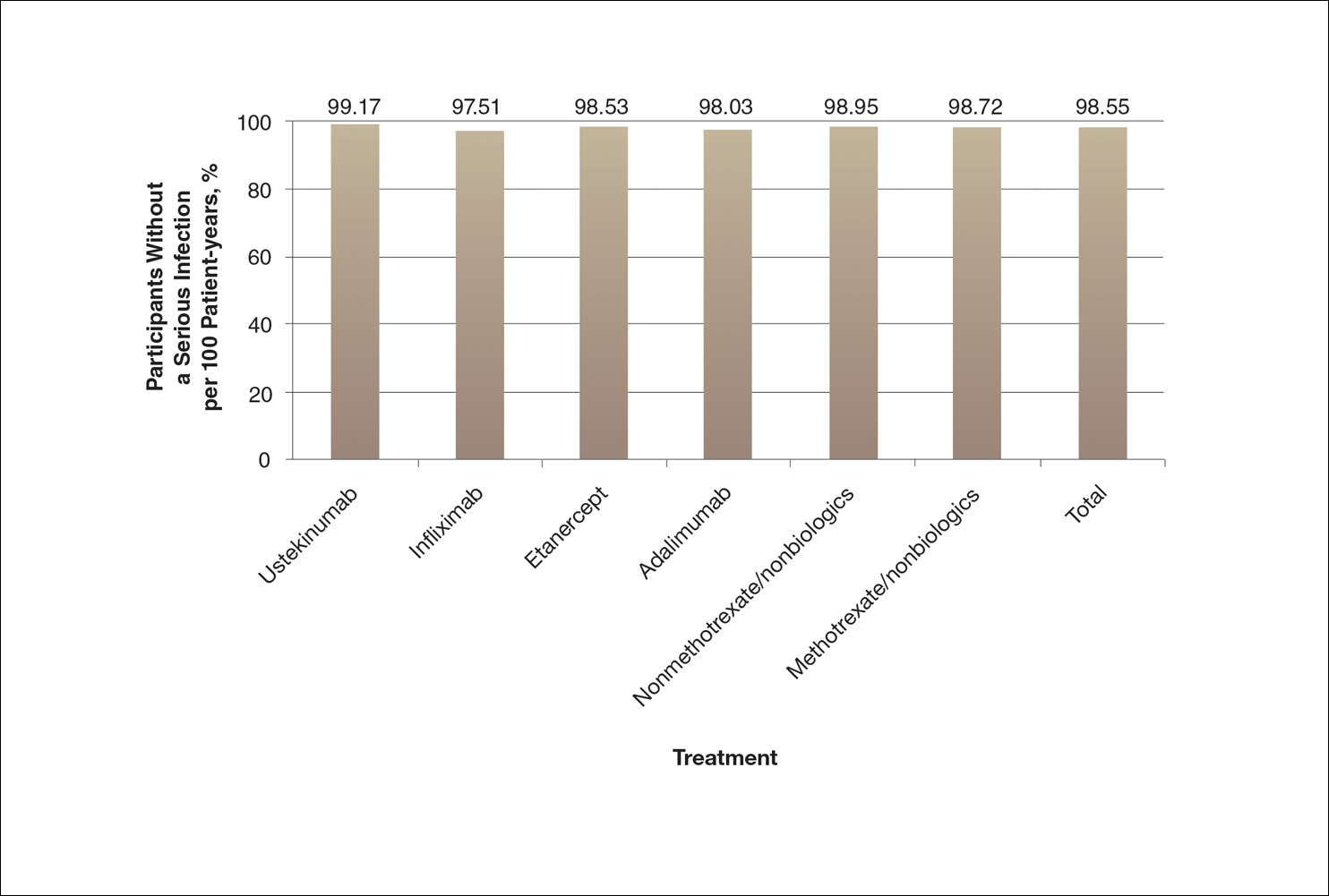

A graph also can present the percentage of patients or patient-years that do not have an adverse effect (Figure 3). This inverse presentation of the data does not emphasize rare cases of patients who have had adverse effects; instead, it emphasizes the large percentage of patients who did not have adverse effects and presents a far more reassuring perspective, even though mathematically the information is identical.

Focus on the Patients Who Do Not Have Adverse Effects of Treatments

Fear of adverse effects is one of the most commonly reported causes of poor treatment adherence.15 New therapies for psoriasis are highly effective and safe, but as with all treatments, they also are associated with some risks. Patients may latch onto those risks too tightly or perhaps, in other circumstances, not tightly enough. The method used by a physician to present safety data to a patient may determine the patient’s perception about treatments.

When trying to give patients an accurate impression of treatment risks, it may be helpful to avoid approaches that focus on presenting the (few) cases of severe adverse drug effects since patients (and physicians) are likely to overweigh the unlikely risk of having an adverse effect if presented with this information. It may be more reassuring to focus on presenting information about the chance of not having an adverse drug effect, assuming the physician’s goal is to be reassuring.

Poor communication with patients when presenting safety data can foster exaggerated fears of an unlikely consequence to the point that patients can be left undertreated and sustaining disease symptoms.16 Physicians may strive to do no harm to their patients, but without careful presentation of safety data in the process of helping the patient make an informed decision, it is possible to do mental harm to patients in the form of fear or even, in the case of nonadherence or treatment refusal, physical harm in the form of continued disease symptoms.

One limitation of this review is that we only used graphical presentation of data as an example. Similar concerns apply to numerical data presentation. Telling a patient the risk of a severe adverse reaction is doubled by a certain treatment may be terrifying, though if the baseline risk is rare, doubling the baseline risk may represent only a minimal increase in the absolute risk. Telling a patient the risk is only 1 in 1000 may still be alarming because many patients tend to focus on the 1, but telling a patient that 999 of 1000 patients do not have a problem can be much more reassuring.

The physician’s goal—to help patients make informed decisions about their treatment—calls for him/her to assimilate safety data into useful information that the patient can use to make an informed decision.17 Overly comforting or alarming, confusing, and inaccurate information can misguide the patient, violating the ethical principle of nonmaleficence. Although there is an obligation to educate patients about risks, there may not be a purely objective way to do it. When physicians present objective data to patients, whether in numerical or graphical form, there will be an unavoidable subjective interpretation of the data. The form of presentation will have a critical effect on patients’ subjective perceptions. Physicians can present objective data in such a way as to be reassuring or frightening.

Conclusion

Despite physicians’ best-intentioned efforts, it may be impossible to avoid presenting safety data in a way that will be subjectively interpreted by patients. Physicians have a choice in how they present data to patients; their best judgment should be used in how they present data to inform patients, guide them, and offer them the best treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Scott Jaros, BA (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), for his assistance in the revision of the manuscript.

- Freyhofer HH. The Nuremberg Medical Trial: The Holocaust and the Origin of the Nuremberg Medical Code. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing; 2004.

- Carlson R, Boyd KM, Webb DJ. The revision of the Declaration of Helsinki: past, present and future. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:695-713.

- Office for Human Research Protections. The Belmont Report. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1979.

- Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A. Explaining risks: turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ. 2002;324:827-830.

- Hayden C, Neame R, Tarrant C. Patients’ adherence-related beliefs about methotrexate: a qualitative study of the role of written patient information. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006918.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Weintraub M. Intelligent noncompliance with special emphasis on the elderly. Contemp Pharm Pract. 1981;4:8-11.

- Horne R. Representations of medication and treatment: advances in theory and measurement. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, eds. Perceptions of Health and Illness: Current Research and Applications. London, England: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 1997:155-188.

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263-291.

- Rottenstreich Y, Hsee CK. Money, kisses, and electric shocks: on the affective psychology of risk. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:185-190.

- Kessler JB, Zhang CY. Behavioural economics and health. In: Detels R, Gulliford M, Abdool Karim Q, et al, eds. Oxford Textbook of Global Public Health. 6th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015:775-789.

- Lipkus IM. Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risks: suggested best practices and future recommendations [published online September 14, 2007]. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:696-713.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Rensberger B. Slanting the slopes of graphs. The Washington Post. May 10, 1995. http://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/1995/05/10/slanting-the-slope-of-graphs/08a34412-60a2-4719-86e5-d7433938c166/. Accessed September 21, 2016.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Hahn RA. The nocebo phenomenon: concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Prev Med. 1997;26(5, pt 1):607-611.

- Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ. 2003;327:745-748.

The Nuremberg Code in 1947,1 the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964,2 and the Belmont Report in 19793 were cornerstones in the establishment of ethical principles in the medical field. These documents specifically highlight the concept of informed consent, which maintains that to practice ethical medicine, physicians must fully inform patients of all therapeutic benefits and especially risks as well as treatment alternatives before they consent to therapeutic intervention. Educating patients about risks of treatment is obligatory. Risk communication involves a mutual exchange of information between physicians and patients; the physician presents risk information in an understandable manner that adequately conveys pertinent data that is critical for the patient to make an informed therapeutic decision.4

An inherent problem with risk education is that patients may be terrified about risks associated with treatment. Some patients will refuse needed treatment because of fear.5 When patients have concerns about the safety profile of a treatment regimen and potential adverse effects, they may be less compliant with treatment.6 The intelligent noncompliance phenomenon occurs when a patient knowingly makes the choice to not adhere to treatment, and concern regarding treatment risks relative to benefits is a common reason underlying this phenomenon.7,8

Behavioral economists have studied how individuals weigh risks. Kahneman and Tversky’s9 prospect theory asserts that individuals tend to overweigh unlikely risks and underweigh more certain risks, which they call the certainty effect; it is the basis of the human tendency to avoid risks in situations of likely gain and to pursue risks in situations of likely loss. The tendency to overweigh rare risks is even more pronounced for affect-rich events such as serious side effects.10 The way data are presented can affect how patients interpret the information. Context and framing of data affect patients’ perceptions.11 We describe several ways to present safety data using graphical presentation of psoriasis treatment safety data as an example and explain how each one can affect patients’ perception of treatment risks.

Approaches to Presenting Safety Data

There are numerous ways to present safety data to patients, including verbal, numeric, and visual strategies.12 Many methods of presentation are a combination of these strategies. Graphs are visual strategies to further categorize and present numeric data, and physicians may choose to incorporate these aids when presenting safety information to patients. Graphical presentations give the patient a mental picture of the data. Numerous types of graphs can be constructed. Kalb et al13 determined the effect of psoriasis treatment on the risk of serious infection from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). We used the results from this study to demonstrate multiple ways of presenting safety data (Figures 1–3).

A graphical presentation with a truncated y-axis is a common approach (Figure 1). Graphs with truncated axes are sometimes used to conserve space or to accentuate certain differences in the graph that would otherwise be less obvious without the zoomed in y-axis.14 These graphs present quantitatively accurate information that can be visually misleading at the same time. Truncated axes accentuate differences, creating mental impressions that are not reflective of the magnitude of the numeric differences. Alternatively, a graph with a full y-axis includes both the maximum and minimum data values on the y-axis (Figure 2). The y-axis also extends maximally to the total number of patients or patient-years studied. This type of graph presents all of the numeric data without distortion.

A graph also can present the percentage of patients or patient-years that do not have an adverse effect (Figure 3). This inverse presentation of the data does not emphasize rare cases of patients who have had adverse effects; instead, it emphasizes the large percentage of patients who did not have adverse effects and presents a far more reassuring perspective, even though mathematically the information is identical.

Focus on the Patients Who Do Not Have Adverse Effects of Treatments

Fear of adverse effects is one of the most commonly reported causes of poor treatment adherence.15 New therapies for psoriasis are highly effective and safe, but as with all treatments, they also are associated with some risks. Patients may latch onto those risks too tightly or perhaps, in other circumstances, not tightly enough. The method used by a physician to present safety data to a patient may determine the patient’s perception about treatments.

When trying to give patients an accurate impression of treatment risks, it may be helpful to avoid approaches that focus on presenting the (few) cases of severe adverse drug effects since patients (and physicians) are likely to overweigh the unlikely risk of having an adverse effect if presented with this information. It may be more reassuring to focus on presenting information about the chance of not having an adverse drug effect, assuming the physician’s goal is to be reassuring.

Poor communication with patients when presenting safety data can foster exaggerated fears of an unlikely consequence to the point that patients can be left undertreated and sustaining disease symptoms.16 Physicians may strive to do no harm to their patients, but without careful presentation of safety data in the process of helping the patient make an informed decision, it is possible to do mental harm to patients in the form of fear or even, in the case of nonadherence or treatment refusal, physical harm in the form of continued disease symptoms.

One limitation of this review is that we only used graphical presentation of data as an example. Similar concerns apply to numerical data presentation. Telling a patient the risk of a severe adverse reaction is doubled by a certain treatment may be terrifying, though if the baseline risk is rare, doubling the baseline risk may represent only a minimal increase in the absolute risk. Telling a patient the risk is only 1 in 1000 may still be alarming because many patients tend to focus on the 1, but telling a patient that 999 of 1000 patients do not have a problem can be much more reassuring.

The physician’s goal—to help patients make informed decisions about their treatment—calls for him/her to assimilate safety data into useful information that the patient can use to make an informed decision.17 Overly comforting or alarming, confusing, and inaccurate information can misguide the patient, violating the ethical principle of nonmaleficence. Although there is an obligation to educate patients about risks, there may not be a purely objective way to do it. When physicians present objective data to patients, whether in numerical or graphical form, there will be an unavoidable subjective interpretation of the data. The form of presentation will have a critical effect on patients’ subjective perceptions. Physicians can present objective data in such a way as to be reassuring or frightening.

Conclusion

Despite physicians’ best-intentioned efforts, it may be impossible to avoid presenting safety data in a way that will be subjectively interpreted by patients. Physicians have a choice in how they present data to patients; their best judgment should be used in how they present data to inform patients, guide them, and offer them the best treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Scott Jaros, BA (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), for his assistance in the revision of the manuscript.

The Nuremberg Code in 1947,1 the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964,2 and the Belmont Report in 19793 were cornerstones in the establishment of ethical principles in the medical field. These documents specifically highlight the concept of informed consent, which maintains that to practice ethical medicine, physicians must fully inform patients of all therapeutic benefits and especially risks as well as treatment alternatives before they consent to therapeutic intervention. Educating patients about risks of treatment is obligatory. Risk communication involves a mutual exchange of information between physicians and patients; the physician presents risk information in an understandable manner that adequately conveys pertinent data that is critical for the patient to make an informed therapeutic decision.4

An inherent problem with risk education is that patients may be terrified about risks associated with treatment. Some patients will refuse needed treatment because of fear.5 When patients have concerns about the safety profile of a treatment regimen and potential adverse effects, they may be less compliant with treatment.6 The intelligent noncompliance phenomenon occurs when a patient knowingly makes the choice to not adhere to treatment, and concern regarding treatment risks relative to benefits is a common reason underlying this phenomenon.7,8

Behavioral economists have studied how individuals weigh risks. Kahneman and Tversky’s9 prospect theory asserts that individuals tend to overweigh unlikely risks and underweigh more certain risks, which they call the certainty effect; it is the basis of the human tendency to avoid risks in situations of likely gain and to pursue risks in situations of likely loss. The tendency to overweigh rare risks is even more pronounced for affect-rich events such as serious side effects.10 The way data are presented can affect how patients interpret the information. Context and framing of data affect patients’ perceptions.11 We describe several ways to present safety data using graphical presentation of psoriasis treatment safety data as an example and explain how each one can affect patients’ perception of treatment risks.

Approaches to Presenting Safety Data

There are numerous ways to present safety data to patients, including verbal, numeric, and visual strategies.12 Many methods of presentation are a combination of these strategies. Graphs are visual strategies to further categorize and present numeric data, and physicians may choose to incorporate these aids when presenting safety information to patients. Graphical presentations give the patient a mental picture of the data. Numerous types of graphs can be constructed. Kalb et al13 determined the effect of psoriasis treatment on the risk of serious infection from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). We used the results from this study to demonstrate multiple ways of presenting safety data (Figures 1–3).

A graphical presentation with a truncated y-axis is a common approach (Figure 1). Graphs with truncated axes are sometimes used to conserve space or to accentuate certain differences in the graph that would otherwise be less obvious without the zoomed in y-axis.14 These graphs present quantitatively accurate information that can be visually misleading at the same time. Truncated axes accentuate differences, creating mental impressions that are not reflective of the magnitude of the numeric differences. Alternatively, a graph with a full y-axis includes both the maximum and minimum data values on the y-axis (Figure 2). The y-axis also extends maximally to the total number of patients or patient-years studied. This type of graph presents all of the numeric data without distortion.

A graph also can present the percentage of patients or patient-years that do not have an adverse effect (Figure 3). This inverse presentation of the data does not emphasize rare cases of patients who have had adverse effects; instead, it emphasizes the large percentage of patients who did not have adverse effects and presents a far more reassuring perspective, even though mathematically the information is identical.

Focus on the Patients Who Do Not Have Adverse Effects of Treatments

Fear of adverse effects is one of the most commonly reported causes of poor treatment adherence.15 New therapies for psoriasis are highly effective and safe, but as with all treatments, they also are associated with some risks. Patients may latch onto those risks too tightly or perhaps, in other circumstances, not tightly enough. The method used by a physician to present safety data to a patient may determine the patient’s perception about treatments.

When trying to give patients an accurate impression of treatment risks, it may be helpful to avoid approaches that focus on presenting the (few) cases of severe adverse drug effects since patients (and physicians) are likely to overweigh the unlikely risk of having an adverse effect if presented with this information. It may be more reassuring to focus on presenting information about the chance of not having an adverse drug effect, assuming the physician’s goal is to be reassuring.

Poor communication with patients when presenting safety data can foster exaggerated fears of an unlikely consequence to the point that patients can be left undertreated and sustaining disease symptoms.16 Physicians may strive to do no harm to their patients, but without careful presentation of safety data in the process of helping the patient make an informed decision, it is possible to do mental harm to patients in the form of fear or even, in the case of nonadherence or treatment refusal, physical harm in the form of continued disease symptoms.

One limitation of this review is that we only used graphical presentation of data as an example. Similar concerns apply to numerical data presentation. Telling a patient the risk of a severe adverse reaction is doubled by a certain treatment may be terrifying, though if the baseline risk is rare, doubling the baseline risk may represent only a minimal increase in the absolute risk. Telling a patient the risk is only 1 in 1000 may still be alarming because many patients tend to focus on the 1, but telling a patient that 999 of 1000 patients do not have a problem can be much more reassuring.

The physician’s goal—to help patients make informed decisions about their treatment—calls for him/her to assimilate safety data into useful information that the patient can use to make an informed decision.17 Overly comforting or alarming, confusing, and inaccurate information can misguide the patient, violating the ethical principle of nonmaleficence. Although there is an obligation to educate patients about risks, there may not be a purely objective way to do it. When physicians present objective data to patients, whether in numerical or graphical form, there will be an unavoidable subjective interpretation of the data. The form of presentation will have a critical effect on patients’ subjective perceptions. Physicians can present objective data in such a way as to be reassuring or frightening.

Conclusion

Despite physicians’ best-intentioned efforts, it may be impossible to avoid presenting safety data in a way that will be subjectively interpreted by patients. Physicians have a choice in how they present data to patients; their best judgment should be used in how they present data to inform patients, guide them, and offer them the best treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Scott Jaros, BA (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), for his assistance in the revision of the manuscript.

- Freyhofer HH. The Nuremberg Medical Trial: The Holocaust and the Origin of the Nuremberg Medical Code. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing; 2004.

- Carlson R, Boyd KM, Webb DJ. The revision of the Declaration of Helsinki: past, present and future. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:695-713.

- Office for Human Research Protections. The Belmont Report. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1979.

- Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A. Explaining risks: turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ. 2002;324:827-830.

- Hayden C, Neame R, Tarrant C. Patients’ adherence-related beliefs about methotrexate: a qualitative study of the role of written patient information. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006918.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Weintraub M. Intelligent noncompliance with special emphasis on the elderly. Contemp Pharm Pract. 1981;4:8-11.

- Horne R. Representations of medication and treatment: advances in theory and measurement. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, eds. Perceptions of Health and Illness: Current Research and Applications. London, England: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 1997:155-188.

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263-291.

- Rottenstreich Y, Hsee CK. Money, kisses, and electric shocks: on the affective psychology of risk. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:185-190.

- Kessler JB, Zhang CY. Behavioural economics and health. In: Detels R, Gulliford M, Abdool Karim Q, et al, eds. Oxford Textbook of Global Public Health. 6th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015:775-789.

- Lipkus IM. Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risks: suggested best practices and future recommendations [published online September 14, 2007]. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:696-713.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Rensberger B. Slanting the slopes of graphs. The Washington Post. May 10, 1995. http://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/1995/05/10/slanting-the-slope-of-graphs/08a34412-60a2-4719-86e5-d7433938c166/. Accessed September 21, 2016.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Hahn RA. The nocebo phenomenon: concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Prev Med. 1997;26(5, pt 1):607-611.

- Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ. 2003;327:745-748.

- Freyhofer HH. The Nuremberg Medical Trial: The Holocaust and the Origin of the Nuremberg Medical Code. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing; 2004.

- Carlson R, Boyd KM, Webb DJ. The revision of the Declaration of Helsinki: past, present and future. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:695-713.

- Office for Human Research Protections. The Belmont Report. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1979.

- Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A. Explaining risks: turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ. 2002;324:827-830.