User login

Perioperative infliximab does not increase serious infection risk

Administration of infliximab within 4 weeks of elective knee or hip arthroplasty did not have any significant effect on patients’ risk of serious infection after surgery, whereas the use of glucocorticoids increased that risk, in an analysis of a Medicare claims database.

“This increased risk with glucocorticoids has been suggested by previous studies [and] although this risk may be related in part to increased disease severity among glucocorticoid treated patients, a direct medication effect is likely. [These data suggest] that prolonged interruptions in infliximab therapy prior to surgery may be counterproductive if higher dose glucocorticoid therapy is used in substitution,” wrote the authors of the new study, led by Michael D. George, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. George and his colleagues examined data from the U.S. Medicare claims system on 4,288 elective knee or hip arthroplasties in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis who received infliximab within 6 months prior to the operation during 2007-2013 (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Jan 27. doi: 10.1002/acr.23209).

The patients had to have received infliximab at least three times within a year of their procedure to establish that they were receiving stable therapy over a long-term period. The investigators also looked at oral prednisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone prescriptions and used data on average dosing to determine how much was administered to each subject.

“Although previous studies have treated TNF stopping vs. not stopping as a dichotomous exposure based on an arbitrary (and variable) stopping definition, in this study the primary analysis evaluated stop timing as a more general categorical exposure using 4-week intervals (half the standard rheumatoid arthritis dosing interval) to allow better assessment of the optimal stop timing,” the authors explained.

Stopping infliximab within 4 weeks of the operation did not significantly influence the rate of serious infection within 30 days (adjusted odds ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.60-1.34) and neither did stopping within 4-8 weeks (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.62-1.36) when compared against stopping 8-12 weeks before surgery. Of the 4,288 arthroplasties, 270 serious infections (6.3%) occurred within 30 days of the operation.

There also was no significant difference between stopping within 4 weeks and 8-12 weeks in the rate of prosthetic joint infection within 1 year of the operation (hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.52-1.87). Overall, prosthetic joint infection occurred 2.9 times per 100 person-years.

However, glucocorticoid doses of more than 10 mg per day were risky. The odds for a serious infection within 30 days after surgery more than doubled with that level of use (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.30-3.40), while the risk for a prosthetic joint infection within 1 year of the surgery also rose significantly (HR, 2.70; 95% CI, 1.30-5.60).

“This is a very well done paper that adds important observational data to our understanding of perioperative medication risk,” Dr. Goodman said.

But the study results will not, at least initially, bring about any changes to the proposed guidelines for perioperative management of patients taking antirheumatic drugs that were described at the 2016 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, she said.

“We were aware of the abstract, which was also presented at the ACR last fall at the time the current perioperative medication management guidelines were presented, and it won’t change guidelines at this point,” said Dr. Goodman, who is one of the lead authors of the proposed guidelines. “[But] I think [the study] could provide important background information to use in a randomized clinical trial to compare infection on [and] not on TNF inhibitors.”

The proposed guidelines conditionally recommend that all biologics should be withheld prior to surgery in patients with inflammatory arthritis, that surgery should be planned for the end of the dosing cycle, and that current daily doses of glucocorticoids, rather than supraphysiologic doses, should be continued in adults with rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or inflammatory arthritis.

The National Institutes of Health, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the Department of Veterans Affairs funded the study. Dr. George did not report any relevant financial disclosures. Two coauthors disclosed receiving research grants or consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies for unrelated work.

Administration of infliximab within 4 weeks of elective knee or hip arthroplasty did not have any significant effect on patients’ risk of serious infection after surgery, whereas the use of glucocorticoids increased that risk, in an analysis of a Medicare claims database.

“This increased risk with glucocorticoids has been suggested by previous studies [and] although this risk may be related in part to increased disease severity among glucocorticoid treated patients, a direct medication effect is likely. [These data suggest] that prolonged interruptions in infliximab therapy prior to surgery may be counterproductive if higher dose glucocorticoid therapy is used in substitution,” wrote the authors of the new study, led by Michael D. George, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. George and his colleagues examined data from the U.S. Medicare claims system on 4,288 elective knee or hip arthroplasties in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis who received infliximab within 6 months prior to the operation during 2007-2013 (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Jan 27. doi: 10.1002/acr.23209).

The patients had to have received infliximab at least three times within a year of their procedure to establish that they were receiving stable therapy over a long-term period. The investigators also looked at oral prednisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone prescriptions and used data on average dosing to determine how much was administered to each subject.

“Although previous studies have treated TNF stopping vs. not stopping as a dichotomous exposure based on an arbitrary (and variable) stopping definition, in this study the primary analysis evaluated stop timing as a more general categorical exposure using 4-week intervals (half the standard rheumatoid arthritis dosing interval) to allow better assessment of the optimal stop timing,” the authors explained.

Stopping infliximab within 4 weeks of the operation did not significantly influence the rate of serious infection within 30 days (adjusted odds ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.60-1.34) and neither did stopping within 4-8 weeks (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.62-1.36) when compared against stopping 8-12 weeks before surgery. Of the 4,288 arthroplasties, 270 serious infections (6.3%) occurred within 30 days of the operation.

There also was no significant difference between stopping within 4 weeks and 8-12 weeks in the rate of prosthetic joint infection within 1 year of the operation (hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.52-1.87). Overall, prosthetic joint infection occurred 2.9 times per 100 person-years.

However, glucocorticoid doses of more than 10 mg per day were risky. The odds for a serious infection within 30 days after surgery more than doubled with that level of use (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.30-3.40), while the risk for a prosthetic joint infection within 1 year of the surgery also rose significantly (HR, 2.70; 95% CI, 1.30-5.60).

“This is a very well done paper that adds important observational data to our understanding of perioperative medication risk,” Dr. Goodman said.

But the study results will not, at least initially, bring about any changes to the proposed guidelines for perioperative management of patients taking antirheumatic drugs that were described at the 2016 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, she said.

“We were aware of the abstract, which was also presented at the ACR last fall at the time the current perioperative medication management guidelines were presented, and it won’t change guidelines at this point,” said Dr. Goodman, who is one of the lead authors of the proposed guidelines. “[But] I think [the study] could provide important background information to use in a randomized clinical trial to compare infection on [and] not on TNF inhibitors.”

The proposed guidelines conditionally recommend that all biologics should be withheld prior to surgery in patients with inflammatory arthritis, that surgery should be planned for the end of the dosing cycle, and that current daily doses of glucocorticoids, rather than supraphysiologic doses, should be continued in adults with rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or inflammatory arthritis.

The National Institutes of Health, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the Department of Veterans Affairs funded the study. Dr. George did not report any relevant financial disclosures. Two coauthors disclosed receiving research grants or consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies for unrelated work.

Administration of infliximab within 4 weeks of elective knee or hip arthroplasty did not have any significant effect on patients’ risk of serious infection after surgery, whereas the use of glucocorticoids increased that risk, in an analysis of a Medicare claims database.

“This increased risk with glucocorticoids has been suggested by previous studies [and] although this risk may be related in part to increased disease severity among glucocorticoid treated patients, a direct medication effect is likely. [These data suggest] that prolonged interruptions in infliximab therapy prior to surgery may be counterproductive if higher dose glucocorticoid therapy is used in substitution,” wrote the authors of the new study, led by Michael D. George, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. George and his colleagues examined data from the U.S. Medicare claims system on 4,288 elective knee or hip arthroplasties in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis who received infliximab within 6 months prior to the operation during 2007-2013 (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Jan 27. doi: 10.1002/acr.23209).

The patients had to have received infliximab at least three times within a year of their procedure to establish that they were receiving stable therapy over a long-term period. The investigators also looked at oral prednisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone prescriptions and used data on average dosing to determine how much was administered to each subject.

“Although previous studies have treated TNF stopping vs. not stopping as a dichotomous exposure based on an arbitrary (and variable) stopping definition, in this study the primary analysis evaluated stop timing as a more general categorical exposure using 4-week intervals (half the standard rheumatoid arthritis dosing interval) to allow better assessment of the optimal stop timing,” the authors explained.

Stopping infliximab within 4 weeks of the operation did not significantly influence the rate of serious infection within 30 days (adjusted odds ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.60-1.34) and neither did stopping within 4-8 weeks (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.62-1.36) when compared against stopping 8-12 weeks before surgery. Of the 4,288 arthroplasties, 270 serious infections (6.3%) occurred within 30 days of the operation.

There also was no significant difference between stopping within 4 weeks and 8-12 weeks in the rate of prosthetic joint infection within 1 year of the operation (hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.52-1.87). Overall, prosthetic joint infection occurred 2.9 times per 100 person-years.

However, glucocorticoid doses of more than 10 mg per day were risky. The odds for a serious infection within 30 days after surgery more than doubled with that level of use (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.30-3.40), while the risk for a prosthetic joint infection within 1 year of the surgery also rose significantly (HR, 2.70; 95% CI, 1.30-5.60).

“This is a very well done paper that adds important observational data to our understanding of perioperative medication risk,” Dr. Goodman said.

But the study results will not, at least initially, bring about any changes to the proposed guidelines for perioperative management of patients taking antirheumatic drugs that were described at the 2016 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, she said.

“We were aware of the abstract, which was also presented at the ACR last fall at the time the current perioperative medication management guidelines were presented, and it won’t change guidelines at this point,” said Dr. Goodman, who is one of the lead authors of the proposed guidelines. “[But] I think [the study] could provide important background information to use in a randomized clinical trial to compare infection on [and] not on TNF inhibitors.”

The proposed guidelines conditionally recommend that all biologics should be withheld prior to surgery in patients with inflammatory arthritis, that surgery should be planned for the end of the dosing cycle, and that current daily doses of glucocorticoids, rather than supraphysiologic doses, should be continued in adults with rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or inflammatory arthritis.

The National Institutes of Health, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the Department of Veterans Affairs funded the study. Dr. George did not report any relevant financial disclosures. Two coauthors disclosed receiving research grants or consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies for unrelated work.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Subjects on glucocorticoids had an OR of 2.11 (95% CI 1.30-3.40) for serious infection within 30 days and an HR of 2.70 (95% CI 1.30-5.60) for prosthetic joint infection within 1 year.

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of 4,288 elective knee and hip arthroplasties in Medicare patients with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis during 2007-2013.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the Department of Veterans Affairs funded the study. Dr. George did not report any relevant financial disclosures. Two coauthors disclosed receiving research grants or consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies for unrelated work.

Psoriatic Arthritis Treatment: The Dermatologist’s Role

Resolution of Psoriatic Lesions on the Gingiva and Hard Palate Following Administration of Adalimumab for Cutaneous Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory systemic disorder of the skin with an incidence of 2% to 3% and is estimated to affect 125 million individuals worldwide.1 Environmental triggers of disease modulation may include cutaneous microbiota, smoking, alcohol use, drugs (ie, beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarials), stress, and trauma.2 Comorbidities associated with cutaneous lesions include psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, stroke, and cardiovascular disease.3 In some studies, patients with psoriasis also had a 24% to 27% increased propensity for periodontal bone loss versus 10% of controls.4,5

Oral psoriasis is rare and case reports have been preferentially published in dental journals, usually with regard to glossal lesions, leaving gingival and palatal psoriatic involvement infrequently reported in the dermatologic literature.6,7 In fact, oral assessments involving 535 psoriatic patients from a dermatology center only yielded cases of geographic and fissured tongue.8 Another study at a psoriasis clinic found 3.8% (21/547) of patients with geographic tongue, 3.1% (17/547) with buccal mucosal plaques, and only 0.4% (2/547) with palatal lesions.9 To extend the knowledge of oral psoriasis, we provide the clinical and histopathologic findings of a patient with synchronous oral and cutaneous psoriatic lesions that responded well to the administration of adalimumab for management of recurrent cutaneous disease.

Case Report

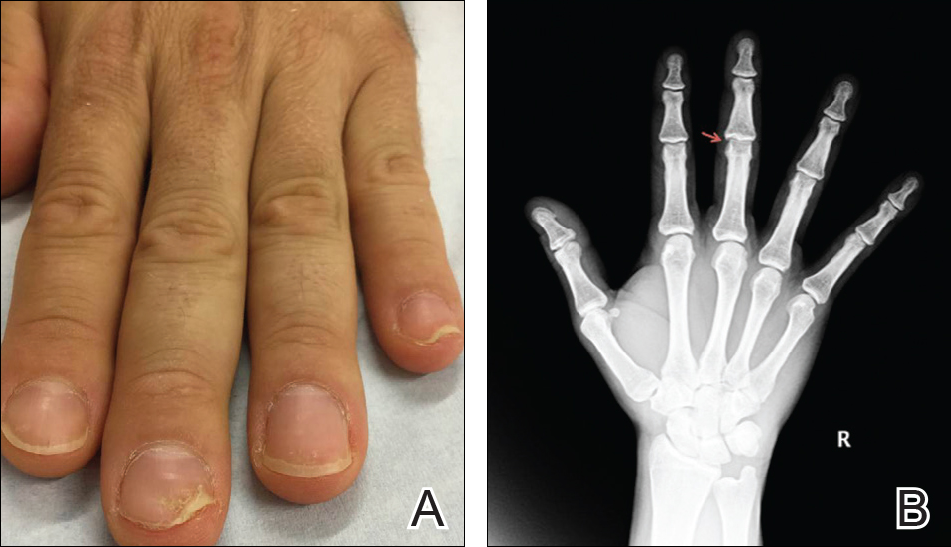

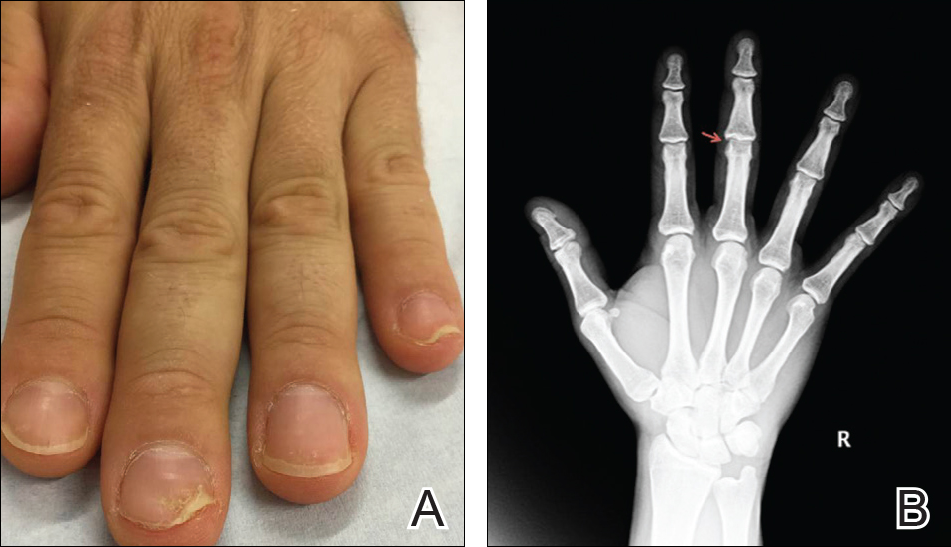

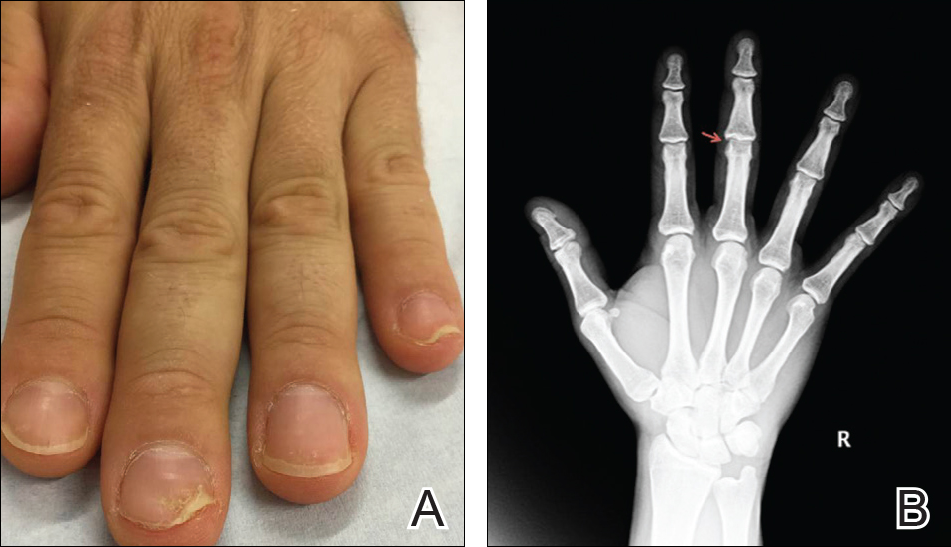

A 51-year-old man presented to the attending periodontist for comprehensive treatment of multiple quadrants of gingival recession. His medical history was remarkable for psoriasis; Prinzmetal angina, which led to myocardial infarction; and diverticulitis. The cutaneous psoriasis began approximately 18 years prior to the current presentation and was initially managed with various topical therapeutics. At an 11-year follow-up, the patient was experiencing poor lesional control as well as severe pruritus and was prescribed etanercept by a dermatologist. His inconsistent compliance with frequency and dosing failed to achieve satisfactory disease suppression and etanercept was discontinued after approximately 2.5 years. Two years later the patient was switched to adalimumab by a dermatologist, and around this time he had developed psoriatic arthritis of the hands and knees and pitting of the nail plates. The patient elected to discontinue adalimumab usage after 3 years due to successful management of the skin lesions, cost considerations, and his perception that the psoriasis could “remain in remission.” After a 6-month lapse, the patient resumed adalimumab due to cutaneous lesional recurrence (Figure 1A).

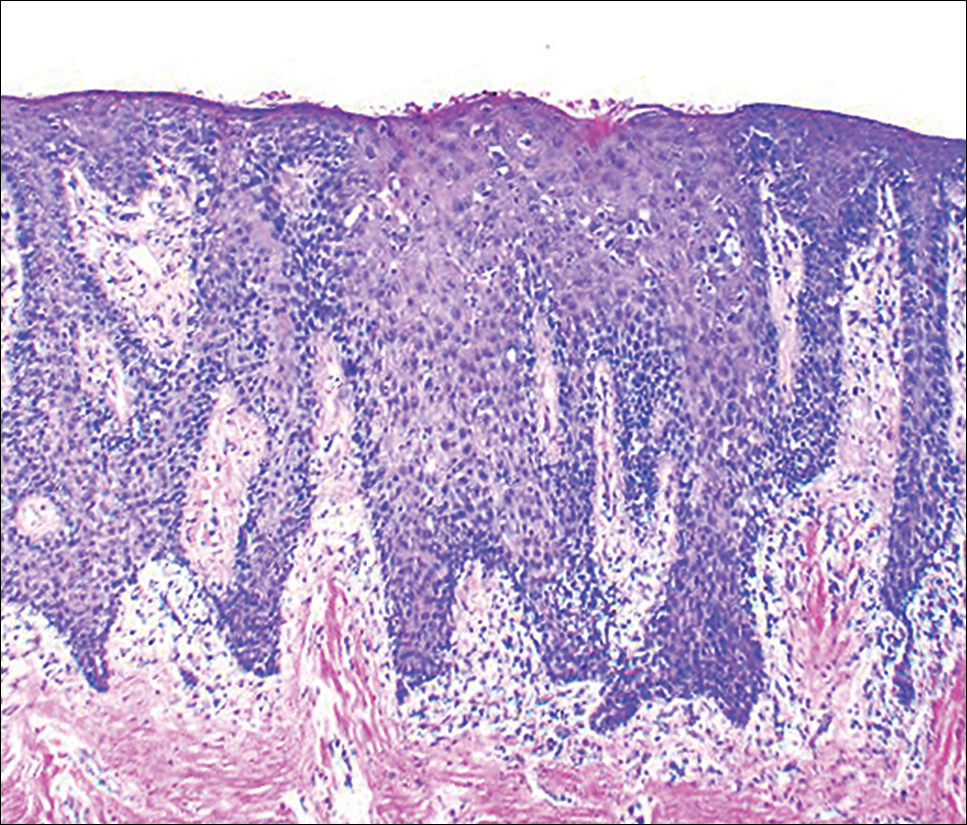

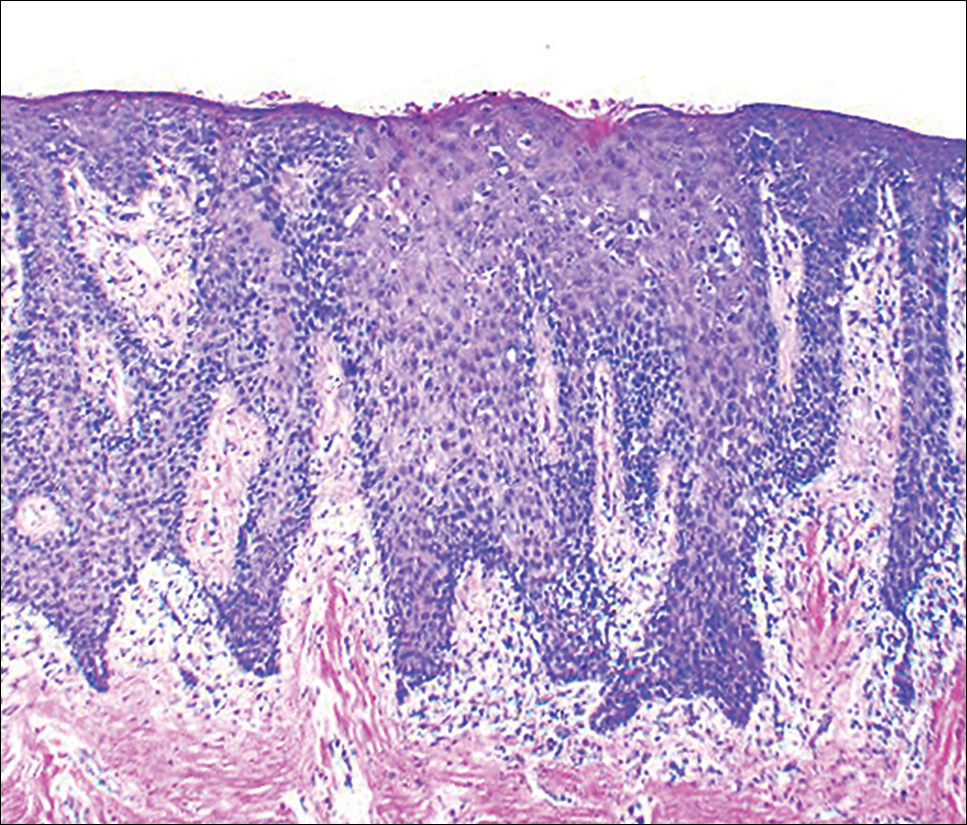

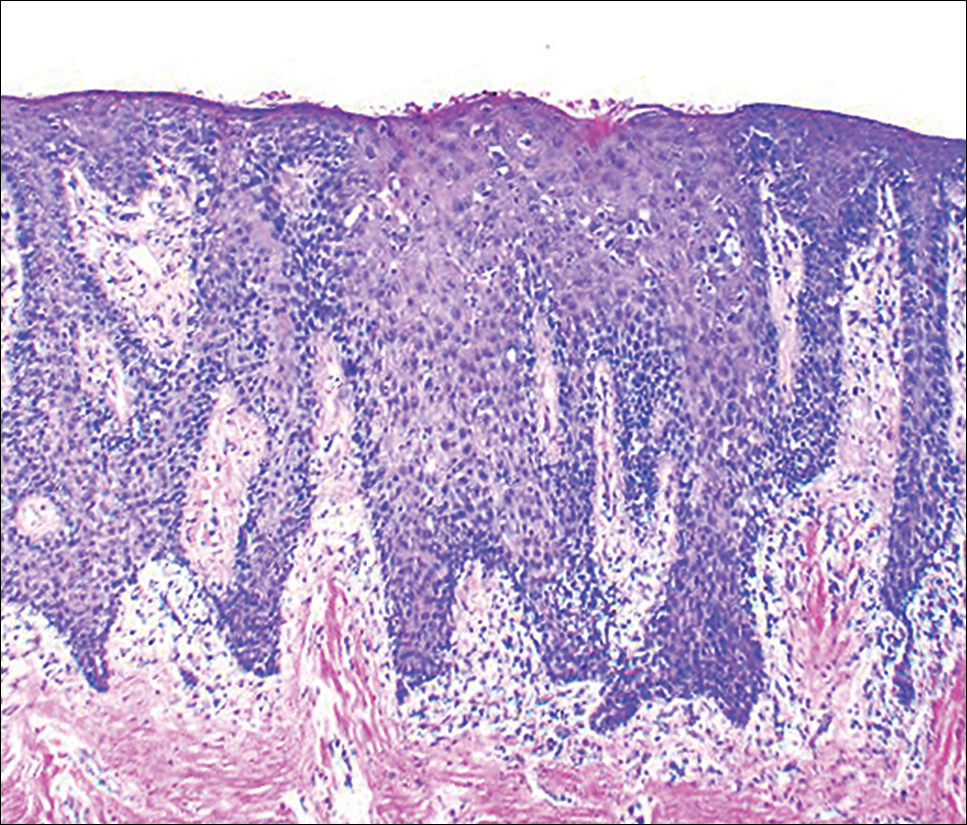

At the current presentation, an oral examination performed 2 days after the reinstitution of adalim-umab revealed generalized severe gingivitis with an atypical inflammatory response that extended from just beyond the mucogingival junction to the marginal gingiva. The gingiva also appeared edematous with a conspicuously granular surface (Figure 1B). The hard palate displayed multiple red macules of varying sizes (Figure 1C). A maxillary gingival biopsy demonstrated hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, spongiosis, acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, numerous collections of neutrophils (Munro microabscesses), and abundant lymphocytes in the subjacent connective tissue (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal hyphae. These features were consistent with oral mucosal psoriasis.

At a 2-month follow-up, the biopsy site had healed without incident and without loss of the gingival architecture. There was an almost-complete resolution of the gingival erythema (Figure 3A) and the patient has since noticed a lack of bleeding using floss. Additionally, the red macules on the palate were no longer present (Figure 3B). The cutaneous plaques were greatly reduced in size and the patient experienced a proportionate decline in pruritus. Based on the uneventful surgical biopsy procedure, the patient was advised to undergo gingival grafting and has not returned for periodontal care.

Comment

Psoriasis of the oral cavity is rare and typically occurs on the tongue and less frequently on the hard palate, lip, buccal mucosa, and gingiva.2,7 The lesions are almost always concordant with cutaneous psoriasis, and only sporadic examples exclusive to the oral mucosa have been recognized.7,10 Gingival psoriasis usually is described as intensely erythematous and occasionally laced with white scaly streaks involving the marginal gingiva that extend toward the mucogingival junction. In general, the erythematous presentation of gingival psoriasis may not be commensurate with the degree of inflammation induced by dental plaque-based periodontal disease. Doben11 documented gingival psoriasis as appearing “deeply stippled and grainy” and commented that the tissue was “friable” and incapable of maintaining a “clean incision line” during periodontal surgery. In our patient, the gingiva also had exhibited a granular surface. Patients with oral psoriasis often report soreness or a burning sensation of the gingiva, which may easily bleed on manipulation or brushing the teeth, whereas other patients are asymptomatic,12 as in our case. Psoriasis of the hard palate usually presents as multiple painless red macules. Unlike cutaneous psoriasis, oral lesions rarely evoke pruritus.10 Histopathologically, oral psoriasis bears a striking resemblance to its cutaneous counterpart. The epithelium has a pronounced parakeratinized surface with elongated rete ridges and aggregations of Munro microabscesses. The connective tissue often is composed of dilated capillaries that closely approximate the epithelium as well as infiltrations of lymphocytes. Specimens suspected for oral psoriasis should routinely be stained with periodic acid–Schiff to rule out candidiasis coinfection. The microscopic findings of our patient were congruent with prior reports of oral psoriasis.7,10-12 Some clinicians have questioned if psoriasis can actually occur in the oral cavity, but most authorities in the field have recognized its true existence, as evidenced by various shared HLA antigens, specifically HLA-Cw.13

Another group of oral lesions collectively referred to as psoriasiform mucositis, notably geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis, erythema migrans) and its extraglossal variant geographic stomatitis,14,15 have histopathologic features and HLAs similar to those seen in cutaneous psoriasis.13 Interestingly, geographic tongue has been found in 3.8% to 9.1% of cohorts with cutaneous psoriasis,8,9 but in the extant population, the vast majority of patients with oral psoriasiform mucositis do not have cutaneous psoriasis. Other differential diagnoses for gingival psoriasis are lichen planus, human immunodeficiency virus–associated periodontitis, desquamative gingivitis, plasma cell gingivitis, erythematous candidiasis, mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, leukemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, orofacial granulomatosis, localized juvenile spongiotic gingivitis hyperplasia, and primary gingivostomatitis.

Management of gingival psoriasis focuses on strategies to reduce inflammation and discomfort and measures to achieve meticulous oral plaque control. Judicious efforts should be exercised to avoid oral soft-tissue injury when performing periodontal scaling, although it has not been established whether gingival psoriasis is associated with the Köbner phenomenon, as seen with cutaneous lesions. Adjunctive measures employed for symptomatic patients have involved the use of corticosteroids (eg, lesional injection, oral rinse, systemic) and oral rinses with retinoic acid, chlorhexidine gluconate, and warm saline.7,10,16 Prolonged utilization of corticosteroids, however, may necessitate supplemental administration of antifungal agents.

This case report represents a rare documentation of a successful outcome of gingival and palatal psoriasis subsequent to the reinstitution of adalimumab solely for treatment of recurrent cutaneous disease. There likely is a pharmacologic basis for the amelioration of oral psoriasis in our patient. Adalimumab is a bivalent IgG monoclonal antibody that binds to activated dermal dendritic cell receptors of tumor necrosis factor α, thereby attenuating a cytokine-derived inflammatory response and apoptosis.17 In fact, patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed notable reductions in both gingival inflammation and bleeding following a 3-month regimen of adalimumab.18

Conclusion

Practitioners should be aware of the phenotypic overlap of cutaneous and oral psoriasis, particularly involving the gingiva and palate. It is recommended that psoriasis patients routinely receive a dental prophylaxis and engage in oral hygiene efforts to reduce the presence of oral microbiota. Furthermore, it is emphasized that psoriatic patients who maintain an atypical erythematous presentation on the oral mucosa undergo a biopsy for identification of the lesions and correlation with disease dissemination. Prospective studies are needed to characterize the clinical courses of oral psoriasis, ascertain their correlative behavior with cutaneous flares, and determine if lesional improvement can be achieved with the use of biologic agents or other therapeutic modalities.

- Gupta R, Debbaneh MG, Liao W. Genetic epidemiology of psoriasis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2014;3:61-78.

- Younai FS, Phelan JA. Oral mucositis with features of psoriasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:61-67.

- Xu T, Zhang YH. Association of psoriasis with stroke and myocardial infarction: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1345-1350.

- Lazaridou E, Tsikrikoni A, Fotiadou C, et al. Association of chronic plaque psoriasis and severe periodontitis: a hospital based case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:967-972.

- Skudutyte-Rysstad R, Slevolden EM, Hansen BF, et al. Association between moderate to severe psoriasis and periodontitis in a Scandinavian population. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:139.

- Zunt SL, Tomich CE. Erythema migrans—a psoriasiform lesion of the oral mucosa. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:1067-1070.

- Reis V, Artico G, Seo J, et al. Psoriasiform mucositis on the gingival and palatal mucosae treated with retinoic-acid mouthwash. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:113-115.

- Germi L, De Giorgi V, Bergamo F, et al. Psoriasis and oral lesions: multicentric study of oral mucosa diseases Italian group (GIPMO). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Kaur I, Handa S, Kumar B. Oral lesions in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:78-79.

- Brayshaw HA, Orban B. Psoriasis gingivae. J Periodontol. 1953;24:156-160.

- Doben DI. Psoriasis of the attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1976;47:38-40.

- Mattsson U, Warfvinge G, Jontell M. Oral psoriasis—a diagnostic dilemma: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;120:e183-e189.

- Dermatologic diseases. In: Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, et al, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009:792-794.

- Brooks JK, Balciunas BA. Geographic stomatitis: review of the literature and report of five cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:421-424.

- Brooks JK, Nikitakis NG. Multiple mucosal lesions. erythema migrans. Gen Dent. 2007;55:160, 163.

- Ulmansky M, Michelle R, Azaz B. Oral psoriasis: report of six new cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:42-45.

- Lis K, Kuzawinska O, Bałkowiec-Iskra E. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors—state of knowledge. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:1175-1185.

- Kobayashi T, Yokoyama T, Ito S, et al. Periodontal and serum protein profiles in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1480-1488.

Psoriasis is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory systemic disorder of the skin with an incidence of 2% to 3% and is estimated to affect 125 million individuals worldwide.1 Environmental triggers of disease modulation may include cutaneous microbiota, smoking, alcohol use, drugs (ie, beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarials), stress, and trauma.2 Comorbidities associated with cutaneous lesions include psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, stroke, and cardiovascular disease.3 In some studies, patients with psoriasis also had a 24% to 27% increased propensity for periodontal bone loss versus 10% of controls.4,5

Oral psoriasis is rare and case reports have been preferentially published in dental journals, usually with regard to glossal lesions, leaving gingival and palatal psoriatic involvement infrequently reported in the dermatologic literature.6,7 In fact, oral assessments involving 535 psoriatic patients from a dermatology center only yielded cases of geographic and fissured tongue.8 Another study at a psoriasis clinic found 3.8% (21/547) of patients with geographic tongue, 3.1% (17/547) with buccal mucosal plaques, and only 0.4% (2/547) with palatal lesions.9 To extend the knowledge of oral psoriasis, we provide the clinical and histopathologic findings of a patient with synchronous oral and cutaneous psoriatic lesions that responded well to the administration of adalimumab for management of recurrent cutaneous disease.

Case Report

A 51-year-old man presented to the attending periodontist for comprehensive treatment of multiple quadrants of gingival recession. His medical history was remarkable for psoriasis; Prinzmetal angina, which led to myocardial infarction; and diverticulitis. The cutaneous psoriasis began approximately 18 years prior to the current presentation and was initially managed with various topical therapeutics. At an 11-year follow-up, the patient was experiencing poor lesional control as well as severe pruritus and was prescribed etanercept by a dermatologist. His inconsistent compliance with frequency and dosing failed to achieve satisfactory disease suppression and etanercept was discontinued after approximately 2.5 years. Two years later the patient was switched to adalimumab by a dermatologist, and around this time he had developed psoriatic arthritis of the hands and knees and pitting of the nail plates. The patient elected to discontinue adalimumab usage after 3 years due to successful management of the skin lesions, cost considerations, and his perception that the psoriasis could “remain in remission.” After a 6-month lapse, the patient resumed adalimumab due to cutaneous lesional recurrence (Figure 1A).

At the current presentation, an oral examination performed 2 days after the reinstitution of adalim-umab revealed generalized severe gingivitis with an atypical inflammatory response that extended from just beyond the mucogingival junction to the marginal gingiva. The gingiva also appeared edematous with a conspicuously granular surface (Figure 1B). The hard palate displayed multiple red macules of varying sizes (Figure 1C). A maxillary gingival biopsy demonstrated hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, spongiosis, acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, numerous collections of neutrophils (Munro microabscesses), and abundant lymphocytes in the subjacent connective tissue (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal hyphae. These features were consistent with oral mucosal psoriasis.

At a 2-month follow-up, the biopsy site had healed without incident and without loss of the gingival architecture. There was an almost-complete resolution of the gingival erythema (Figure 3A) and the patient has since noticed a lack of bleeding using floss. Additionally, the red macules on the palate were no longer present (Figure 3B). The cutaneous plaques were greatly reduced in size and the patient experienced a proportionate decline in pruritus. Based on the uneventful surgical biopsy procedure, the patient was advised to undergo gingival grafting and has not returned for periodontal care.

Comment

Psoriasis of the oral cavity is rare and typically occurs on the tongue and less frequently on the hard palate, lip, buccal mucosa, and gingiva.2,7 The lesions are almost always concordant with cutaneous psoriasis, and only sporadic examples exclusive to the oral mucosa have been recognized.7,10 Gingival psoriasis usually is described as intensely erythematous and occasionally laced with white scaly streaks involving the marginal gingiva that extend toward the mucogingival junction. In general, the erythematous presentation of gingival psoriasis may not be commensurate with the degree of inflammation induced by dental plaque-based periodontal disease. Doben11 documented gingival psoriasis as appearing “deeply stippled and grainy” and commented that the tissue was “friable” and incapable of maintaining a “clean incision line” during periodontal surgery. In our patient, the gingiva also had exhibited a granular surface. Patients with oral psoriasis often report soreness or a burning sensation of the gingiva, which may easily bleed on manipulation or brushing the teeth, whereas other patients are asymptomatic,12 as in our case. Psoriasis of the hard palate usually presents as multiple painless red macules. Unlike cutaneous psoriasis, oral lesions rarely evoke pruritus.10 Histopathologically, oral psoriasis bears a striking resemblance to its cutaneous counterpart. The epithelium has a pronounced parakeratinized surface with elongated rete ridges and aggregations of Munro microabscesses. The connective tissue often is composed of dilated capillaries that closely approximate the epithelium as well as infiltrations of lymphocytes. Specimens suspected for oral psoriasis should routinely be stained with periodic acid–Schiff to rule out candidiasis coinfection. The microscopic findings of our patient were congruent with prior reports of oral psoriasis.7,10-12 Some clinicians have questioned if psoriasis can actually occur in the oral cavity, but most authorities in the field have recognized its true existence, as evidenced by various shared HLA antigens, specifically HLA-Cw.13

Another group of oral lesions collectively referred to as psoriasiform mucositis, notably geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis, erythema migrans) and its extraglossal variant geographic stomatitis,14,15 have histopathologic features and HLAs similar to those seen in cutaneous psoriasis.13 Interestingly, geographic tongue has been found in 3.8% to 9.1% of cohorts with cutaneous psoriasis,8,9 but in the extant population, the vast majority of patients with oral psoriasiform mucositis do not have cutaneous psoriasis. Other differential diagnoses for gingival psoriasis are lichen planus, human immunodeficiency virus–associated periodontitis, desquamative gingivitis, plasma cell gingivitis, erythematous candidiasis, mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, leukemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, orofacial granulomatosis, localized juvenile spongiotic gingivitis hyperplasia, and primary gingivostomatitis.

Management of gingival psoriasis focuses on strategies to reduce inflammation and discomfort and measures to achieve meticulous oral plaque control. Judicious efforts should be exercised to avoid oral soft-tissue injury when performing periodontal scaling, although it has not been established whether gingival psoriasis is associated with the Köbner phenomenon, as seen with cutaneous lesions. Adjunctive measures employed for symptomatic patients have involved the use of corticosteroids (eg, lesional injection, oral rinse, systemic) and oral rinses with retinoic acid, chlorhexidine gluconate, and warm saline.7,10,16 Prolonged utilization of corticosteroids, however, may necessitate supplemental administration of antifungal agents.

This case report represents a rare documentation of a successful outcome of gingival and palatal psoriasis subsequent to the reinstitution of adalimumab solely for treatment of recurrent cutaneous disease. There likely is a pharmacologic basis for the amelioration of oral psoriasis in our patient. Adalimumab is a bivalent IgG monoclonal antibody that binds to activated dermal dendritic cell receptors of tumor necrosis factor α, thereby attenuating a cytokine-derived inflammatory response and apoptosis.17 In fact, patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed notable reductions in both gingival inflammation and bleeding following a 3-month regimen of adalimumab.18

Conclusion

Practitioners should be aware of the phenotypic overlap of cutaneous and oral psoriasis, particularly involving the gingiva and palate. It is recommended that psoriasis patients routinely receive a dental prophylaxis and engage in oral hygiene efforts to reduce the presence of oral microbiota. Furthermore, it is emphasized that psoriatic patients who maintain an atypical erythematous presentation on the oral mucosa undergo a biopsy for identification of the lesions and correlation with disease dissemination. Prospective studies are needed to characterize the clinical courses of oral psoriasis, ascertain their correlative behavior with cutaneous flares, and determine if lesional improvement can be achieved with the use of biologic agents or other therapeutic modalities.

Psoriasis is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory systemic disorder of the skin with an incidence of 2% to 3% and is estimated to affect 125 million individuals worldwide.1 Environmental triggers of disease modulation may include cutaneous microbiota, smoking, alcohol use, drugs (ie, beta-blockers, lithium, antimalarials), stress, and trauma.2 Comorbidities associated with cutaneous lesions include psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, stroke, and cardiovascular disease.3 In some studies, patients with psoriasis also had a 24% to 27% increased propensity for periodontal bone loss versus 10% of controls.4,5

Oral psoriasis is rare and case reports have been preferentially published in dental journals, usually with regard to glossal lesions, leaving gingival and palatal psoriatic involvement infrequently reported in the dermatologic literature.6,7 In fact, oral assessments involving 535 psoriatic patients from a dermatology center only yielded cases of geographic and fissured tongue.8 Another study at a psoriasis clinic found 3.8% (21/547) of patients with geographic tongue, 3.1% (17/547) with buccal mucosal plaques, and only 0.4% (2/547) with palatal lesions.9 To extend the knowledge of oral psoriasis, we provide the clinical and histopathologic findings of a patient with synchronous oral and cutaneous psoriatic lesions that responded well to the administration of adalimumab for management of recurrent cutaneous disease.

Case Report

A 51-year-old man presented to the attending periodontist for comprehensive treatment of multiple quadrants of gingival recession. His medical history was remarkable for psoriasis; Prinzmetal angina, which led to myocardial infarction; and diverticulitis. The cutaneous psoriasis began approximately 18 years prior to the current presentation and was initially managed with various topical therapeutics. At an 11-year follow-up, the patient was experiencing poor lesional control as well as severe pruritus and was prescribed etanercept by a dermatologist. His inconsistent compliance with frequency and dosing failed to achieve satisfactory disease suppression and etanercept was discontinued after approximately 2.5 years. Two years later the patient was switched to adalimumab by a dermatologist, and around this time he had developed psoriatic arthritis of the hands and knees and pitting of the nail plates. The patient elected to discontinue adalimumab usage after 3 years due to successful management of the skin lesions, cost considerations, and his perception that the psoriasis could “remain in remission.” After a 6-month lapse, the patient resumed adalimumab due to cutaneous lesional recurrence (Figure 1A).

At the current presentation, an oral examination performed 2 days after the reinstitution of adalim-umab revealed generalized severe gingivitis with an atypical inflammatory response that extended from just beyond the mucogingival junction to the marginal gingiva. The gingiva also appeared edematous with a conspicuously granular surface (Figure 1B). The hard palate displayed multiple red macules of varying sizes (Figure 1C). A maxillary gingival biopsy demonstrated hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, spongiosis, acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, numerous collections of neutrophils (Munro microabscesses), and abundant lymphocytes in the subjacent connective tissue (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal hyphae. These features were consistent with oral mucosal psoriasis.

At a 2-month follow-up, the biopsy site had healed without incident and without loss of the gingival architecture. There was an almost-complete resolution of the gingival erythema (Figure 3A) and the patient has since noticed a lack of bleeding using floss. Additionally, the red macules on the palate were no longer present (Figure 3B). The cutaneous plaques were greatly reduced in size and the patient experienced a proportionate decline in pruritus. Based on the uneventful surgical biopsy procedure, the patient was advised to undergo gingival grafting and has not returned for periodontal care.

Comment

Psoriasis of the oral cavity is rare and typically occurs on the tongue and less frequently on the hard palate, lip, buccal mucosa, and gingiva.2,7 The lesions are almost always concordant with cutaneous psoriasis, and only sporadic examples exclusive to the oral mucosa have been recognized.7,10 Gingival psoriasis usually is described as intensely erythematous and occasionally laced with white scaly streaks involving the marginal gingiva that extend toward the mucogingival junction. In general, the erythematous presentation of gingival psoriasis may not be commensurate with the degree of inflammation induced by dental plaque-based periodontal disease. Doben11 documented gingival psoriasis as appearing “deeply stippled and grainy” and commented that the tissue was “friable” and incapable of maintaining a “clean incision line” during periodontal surgery. In our patient, the gingiva also had exhibited a granular surface. Patients with oral psoriasis often report soreness or a burning sensation of the gingiva, which may easily bleed on manipulation or brushing the teeth, whereas other patients are asymptomatic,12 as in our case. Psoriasis of the hard palate usually presents as multiple painless red macules. Unlike cutaneous psoriasis, oral lesions rarely evoke pruritus.10 Histopathologically, oral psoriasis bears a striking resemblance to its cutaneous counterpart. The epithelium has a pronounced parakeratinized surface with elongated rete ridges and aggregations of Munro microabscesses. The connective tissue often is composed of dilated capillaries that closely approximate the epithelium as well as infiltrations of lymphocytes. Specimens suspected for oral psoriasis should routinely be stained with periodic acid–Schiff to rule out candidiasis coinfection. The microscopic findings of our patient were congruent with prior reports of oral psoriasis.7,10-12 Some clinicians have questioned if psoriasis can actually occur in the oral cavity, but most authorities in the field have recognized its true existence, as evidenced by various shared HLA antigens, specifically HLA-Cw.13

Another group of oral lesions collectively referred to as psoriasiform mucositis, notably geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis, erythema migrans) and its extraglossal variant geographic stomatitis,14,15 have histopathologic features and HLAs similar to those seen in cutaneous psoriasis.13 Interestingly, geographic tongue has been found in 3.8% to 9.1% of cohorts with cutaneous psoriasis,8,9 but in the extant population, the vast majority of patients with oral psoriasiform mucositis do not have cutaneous psoriasis. Other differential diagnoses for gingival psoriasis are lichen planus, human immunodeficiency virus–associated periodontitis, desquamative gingivitis, plasma cell gingivitis, erythematous candidiasis, mucous membrane pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, leukemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, orofacial granulomatosis, localized juvenile spongiotic gingivitis hyperplasia, and primary gingivostomatitis.

Management of gingival psoriasis focuses on strategies to reduce inflammation and discomfort and measures to achieve meticulous oral plaque control. Judicious efforts should be exercised to avoid oral soft-tissue injury when performing periodontal scaling, although it has not been established whether gingival psoriasis is associated with the Köbner phenomenon, as seen with cutaneous lesions. Adjunctive measures employed for symptomatic patients have involved the use of corticosteroids (eg, lesional injection, oral rinse, systemic) and oral rinses with retinoic acid, chlorhexidine gluconate, and warm saline.7,10,16 Prolonged utilization of corticosteroids, however, may necessitate supplemental administration of antifungal agents.

This case report represents a rare documentation of a successful outcome of gingival and palatal psoriasis subsequent to the reinstitution of adalimumab solely for treatment of recurrent cutaneous disease. There likely is a pharmacologic basis for the amelioration of oral psoriasis in our patient. Adalimumab is a bivalent IgG monoclonal antibody that binds to activated dermal dendritic cell receptors of tumor necrosis factor α, thereby attenuating a cytokine-derived inflammatory response and apoptosis.17 In fact, patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed notable reductions in both gingival inflammation and bleeding following a 3-month regimen of adalimumab.18

Conclusion

Practitioners should be aware of the phenotypic overlap of cutaneous and oral psoriasis, particularly involving the gingiva and palate. It is recommended that psoriasis patients routinely receive a dental prophylaxis and engage in oral hygiene efforts to reduce the presence of oral microbiota. Furthermore, it is emphasized that psoriatic patients who maintain an atypical erythematous presentation on the oral mucosa undergo a biopsy for identification of the lesions and correlation with disease dissemination. Prospective studies are needed to characterize the clinical courses of oral psoriasis, ascertain their correlative behavior with cutaneous flares, and determine if lesional improvement can be achieved with the use of biologic agents or other therapeutic modalities.

- Gupta R, Debbaneh MG, Liao W. Genetic epidemiology of psoriasis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2014;3:61-78.

- Younai FS, Phelan JA. Oral mucositis with features of psoriasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:61-67.

- Xu T, Zhang YH. Association of psoriasis with stroke and myocardial infarction: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1345-1350.

- Lazaridou E, Tsikrikoni A, Fotiadou C, et al. Association of chronic plaque psoriasis and severe periodontitis: a hospital based case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:967-972.

- Skudutyte-Rysstad R, Slevolden EM, Hansen BF, et al. Association between moderate to severe psoriasis and periodontitis in a Scandinavian population. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:139.

- Zunt SL, Tomich CE. Erythema migrans—a psoriasiform lesion of the oral mucosa. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:1067-1070.

- Reis V, Artico G, Seo J, et al. Psoriasiform mucositis on the gingival and palatal mucosae treated with retinoic-acid mouthwash. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:113-115.

- Germi L, De Giorgi V, Bergamo F, et al. Psoriasis and oral lesions: multicentric study of oral mucosa diseases Italian group (GIPMO). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Kaur I, Handa S, Kumar B. Oral lesions in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:78-79.

- Brayshaw HA, Orban B. Psoriasis gingivae. J Periodontol. 1953;24:156-160.

- Doben DI. Psoriasis of the attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1976;47:38-40.

- Mattsson U, Warfvinge G, Jontell M. Oral psoriasis—a diagnostic dilemma: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;120:e183-e189.

- Dermatologic diseases. In: Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, et al, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009:792-794.

- Brooks JK, Balciunas BA. Geographic stomatitis: review of the literature and report of five cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:421-424.

- Brooks JK, Nikitakis NG. Multiple mucosal lesions. erythema migrans. Gen Dent. 2007;55:160, 163.

- Ulmansky M, Michelle R, Azaz B. Oral psoriasis: report of six new cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:42-45.

- Lis K, Kuzawinska O, Bałkowiec-Iskra E. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors—state of knowledge. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:1175-1185.

- Kobayashi T, Yokoyama T, Ito S, et al. Periodontal and serum protein profiles in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1480-1488.

- Gupta R, Debbaneh MG, Liao W. Genetic epidemiology of psoriasis. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2014;3:61-78.

- Younai FS, Phelan JA. Oral mucositis with features of psoriasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:61-67.

- Xu T, Zhang YH. Association of psoriasis with stroke and myocardial infarction: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1345-1350.

- Lazaridou E, Tsikrikoni A, Fotiadou C, et al. Association of chronic plaque psoriasis and severe periodontitis: a hospital based case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:967-972.

- Skudutyte-Rysstad R, Slevolden EM, Hansen BF, et al. Association between moderate to severe psoriasis and periodontitis in a Scandinavian population. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:139.

- Zunt SL, Tomich CE. Erythema migrans—a psoriasiform lesion of the oral mucosa. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:1067-1070.

- Reis V, Artico G, Seo J, et al. Psoriasiform mucositis on the gingival and palatal mucosae treated with retinoic-acid mouthwash. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:113-115.

- Germi L, De Giorgi V, Bergamo F, et al. Psoriasis and oral lesions: multicentric study of oral mucosa diseases Italian group (GIPMO). Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Kaur I, Handa S, Kumar B. Oral lesions in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:78-79.

- Brayshaw HA, Orban B. Psoriasis gingivae. J Periodontol. 1953;24:156-160.

- Doben DI. Psoriasis of the attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1976;47:38-40.

- Mattsson U, Warfvinge G, Jontell M. Oral psoriasis—a diagnostic dilemma: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;120:e183-e189.

- Dermatologic diseases. In: Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, et al, eds. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009:792-794.

- Brooks JK, Balciunas BA. Geographic stomatitis: review of the literature and report of five cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:421-424.

- Brooks JK, Nikitakis NG. Multiple mucosal lesions. erythema migrans. Gen Dent. 2007;55:160, 163.

- Ulmansky M, Michelle R, Azaz B. Oral psoriasis: report of six new cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:42-45.

- Lis K, Kuzawinska O, Bałkowiec-Iskra E. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors—state of knowledge. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:1175-1185.

- Kobayashi T, Yokoyama T, Ito S, et al. Periodontal and serum protein profiles in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1480-1488.

Practice Points

- A subset of patients with cutaneous psoriasis may be associated with oral psoriatic outbreaks.

- Oral psoriasis presents as an atypical inflammatory response, and histopathologic assessment is recommended for lesional identity.

- Use of adalimumab for management of cutaneous psoriasis may demonstrate efficacy for oral psoriasis.

Biosimilars in Psoriasis: The Future or Not?

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a biosimilar is “highly similar to an FDA-approved biological product, . . . and has no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety and effectiveness.”1 The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation (BPCI) Act of 2009 created an expedited pathway for the approval of products shown to be biosimilar to FDA-licensed reference products.2 In 2013, the European Medicines Agency approved the first biosimilar modeled on infliximab (Remsima [formerly known as CT-P13], Celltrion Healthcare Co, Ltd) for the same indications as its reference product.3 In 2016, the FDA approved Inflectra (Hospira, a Pfizer Company), an infliximab biosimilar; Erelzi (Sandoz, a Novartis Division), an etanercept biosimilar; and Amjevita (Amgen Inc), an adalimumab biosimilar, all for numerous clinical indications including plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.4-6

There has been a substantial amount of distrust surrounding the biosimilars; however, as the patents for the biologic agents expire, new biosimilars will undoubtedly flood the market. In this article, we provide information that will help dermatologists understand the need for and use of these agents.

Biosimilars Versus Generic Drugs

Small-molecule generics can be made in a process that is relatively inexpensive, reproducible, and able to yield identical products with each lot.7 In contrast, biosimilars are large complex proteins made in living cells. They differ from their reference product because of changes that occur during manufacturing (eg, purification system, posttranslational modifications).7-9 Glycosylation is particularly sensitive to manufacturing and can affect the immunogenicity of the product.9 The impact of manufacturing can be substantial; for example, during phase 3 trials for efalizumab, a change in the manufacturing facility affected pharmacokinetic properties to such a degree that the FDA required a repeat of the trials.10

FDA Guidelines on Biosimilarity

The FDA outlines the following approach to demonstrate biosimilarity.2 The first step is structural characterization to evaluate the primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures and posttranslational modifications. The next step utilizes in vivo and/or in vitro functional assays to compare the biosimilar and reference product. The third step is a focus on toxicity and immunogenicity. The fourth step involves clinical studies to study pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, immunogenicity, safety, and efficacy. After the biosimilar has been approved, there must be a system in place to monitor postmarketing safety. If a biosimilar is tested in one patient population (eg, patients with plaque psoriasis), a request can be made to approve the drug for all the conditions that the reference product was approved for, such as plaque psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease, even though clinical trials were not performed in all of these patient populations.2 The BPCI Act leaves it up to the FDA to determine how much and what type of data (eg, in vitro, in vivo, clinical) are required.11

Extrapolation and Interchangeability

Once a biosimilar has been approved, 2 questions must be answered: First, can its use be extrapolated to all indications for the reference product? The infliximab biosimilar approved by the European Medicines Agency and the FDA had only been studied in patients with ankylosing spondylitis12 and rheumatoid arthritis,13 yet it was granted all the indications for infliximab, including severe plaque psoriasis.14 As of now, the various regulatory agencies differ on their policies regarding extrapolation. Extrapolation is not automatically bestowed on a biosimilar in the United States but can be requested by the manufacturer.2

Second, can the biosimilar be seamlessly switched with its reference product at the pharmacy level? The BPCI Act allows for the substitution of biosimilars that are deemed interchangeable without notifying the provider, yet individual states ultimately can pass laws regarding this issue.15,16 An interchangeable agent would “produce the same clinical result as the reference product,” and “the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy of alternating or switching between use of the biological product and the reference product is not greater than the risk of using the reference product.”15 Generic drugs are allowed to be substituted without notifying the patient or prescriber16; however, biosimilars that are not deemed interchangeable would require permission from the prescriber before substitution.11

Biosimilars for Psoriasis

In April 2016, an infliximab biosimilar (Inflectra) became the second biosimilar approved by the FDA.4 Inflectra was studied in clinical trials for patients with ankylosing spondylitis17 and rheumatoid arthritis,18 and in both trials the biosimilar was found to have similar efficacy and safety profiles to that of the reference product. In August 2016, an etanercept biosimilar (Erelzi) was approved,5 and in September 2016, an adalimumab biosimilar (Amjevita) was approved.6

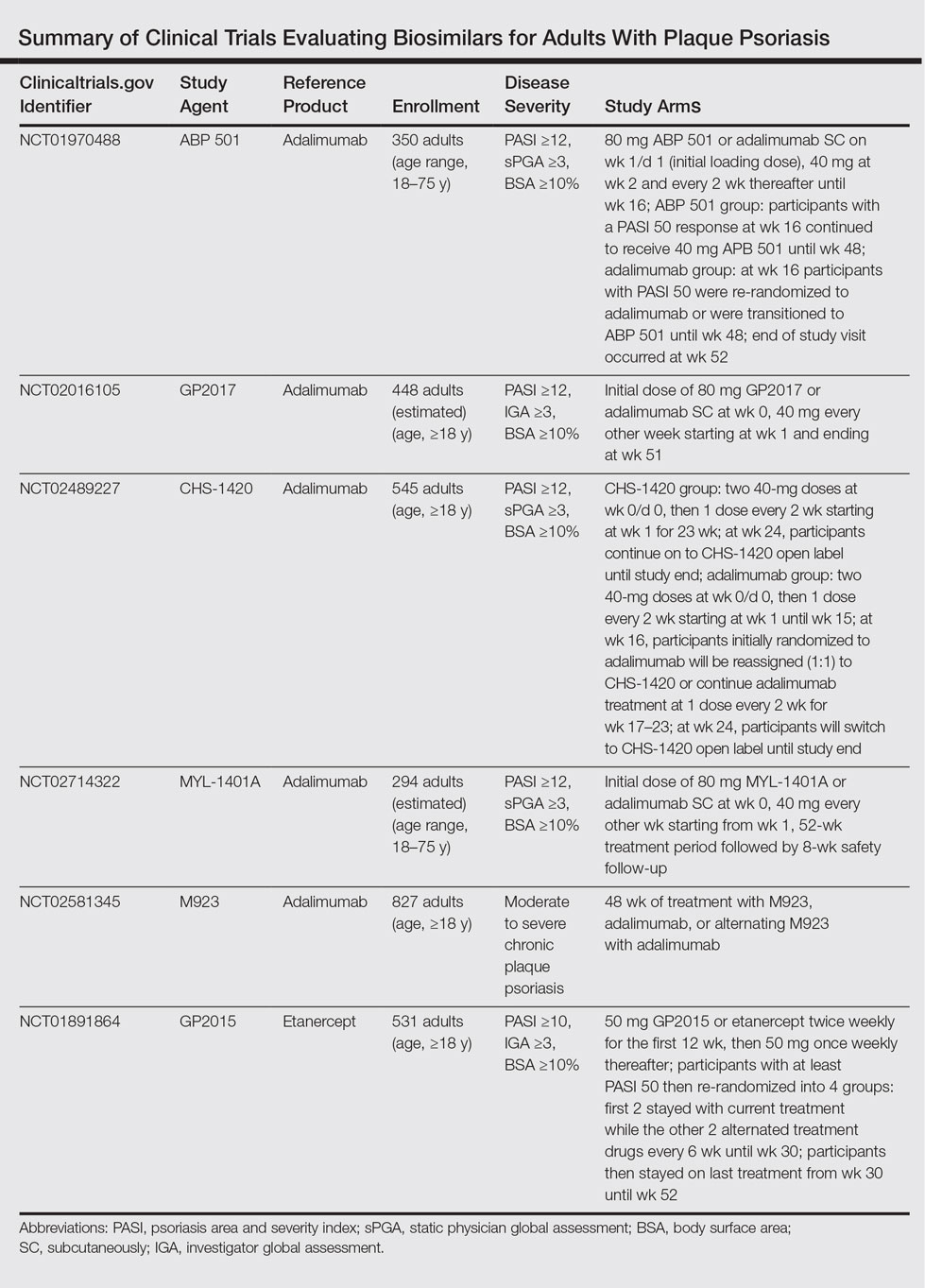

The Table summarizes clinical trials (both completed and ongoing) evaluating biosimilars in adults with plaque psoriasis; thus far, there are 2464 participants enrolled across 5 different studies of adalimumab biosimilars (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifiers NCT01970488, NCT02016105, NCT02489227, NCT02714322, NCT02581345) and 531 participants in an etanercept biosimilar study (NCT01891864).

A phase 3 double-blind study compared adalimumab to an adalimumab biosimilar (ABP 501) in 350 adults with plaque psoriasis (NCT01970488). Participants received an initial loading dose of adalimumab (n=175) or ABP 501 (n=175) 80 mg subcutaneously on week 1/day 1, followed by 40 mg at week 2 every 2 weeks thereafter. At week 16, participants with psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) 50 or greater remained in the study for up to 52 weeks; those who were receiving adalimumab were re-randomized to receive either ABP 501 or adalimumab. Participants receiving ABP 501 continued to receive the biosimilar. The mean PASI improvement at weeks 16, 32, and 50 was 86.6, 87.6, and 87.2, respectively, in the ABP 501/ABP 501 group (A/A) compared to 88.0, 88.2, and 88.1, respectively, in the adalimumab/adalimumab group (B/B).19 Autoantibodies developed in 68.4% of participants in the A/A group compared to 74.7% in the B/B group. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was 86.2% in the A/A group and 78.5% in the B/B group. The most common TEAEs were nasopharyngitis, headache, and upper respiratory tract infection. The incidence of serious TEAEs was 4.6% in the A/A group compared to 5.1% in the B/B group. Overall, the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the adalimumab biosimilar was comparable to the reference product.19

A second phase 3 trial (ADACCESS) evaluated the adalimumab biosimilar GP2017 (NCT02016105). Participants received an initial dose of 80 mg subcutaneously of either GP2017 or adalimumab at week 0, followed by 40 mg every other week starting at week 1 and ending at week 51. The study has been completed but results are not yet available.

The third trial is evaluating the adalimumab biosimilar CHS-1420 (NCT02489227). Participants in the experimental arm receive two 40-mg doses of CHS-1420 at week 0/day 0, and then 1 dose every 2 weeks from week 1 for 23 weeks. At week 24, participants continue with an open-label study. Participants in the adalimumab group receive two 40-mg doses at week 0/day 0, and then 1 dose every 2 weeks from week 1 to week 15. At week 16, participants will be re-randomized (1:1) to continue adalimumab or start CHS-1420 at one 40-mg dose every 2 weeks during weeks 17 to 23. At week 24, participants will switch to CHS-1420 open label until the end of the study. Study results are not yet available; the study is ongoing but not recruiting.

The fourth ongoing trial is evaluating the adalimumab biosimilar MYL-1401A (NCT02714322). Participants receive an initial dose of 80 mg subcutaneously of either MYL-1401A or adalimumab (2:1), followed by 40 mg every other week starting 1 week after the initial dose. After the 52-week treatment period, there is an 8-week safety follow-up period. Study results are not yet available; the study is ongoing but not recruiting.

A fifth adalimumab biosimilar, M923, also is currently being tested in clinical trials (NCT02581345). Participants receive either M923, adalimumab, or alternate between the 2 agents. Although the study is still ongoing, data released from the manufacturer state that the proportion of participants who achieved PASI 75 after 16 weeks of treatment was equivalent in the 2 treatment groups. The proportion of participants who achieved PASI 90, as well as the type, frequency, and severity of adverse events, also were comparable.20

The EGALITY trial, completed in March 2015, compared the etanercept biosimilar GP2015 to etanercept over a 52-week period (NCT01891864). Participants received either GP2015 or etanercept 50 mg twice weekly for the first 12 weeks. Participants with at least PASI 50 were then re-randomized into 4 groups: the first 2 groups stayed with their current treatments while the other 2 groups alternated treatments every 6 weeks until week 30. Participants then stayed on their last treatment from week 30 to week 52. The adjusted PASI 75 response rate at week 12 was 73.4% in the group receiving GP2015 and 75.7% in the group receiving etanercept.21 The percentage change in PASI score at all time points was found to be comparable from baseline until week 52. Importantly, the incidence of TEAEs up to week 52 was comparable and no new safety issues were reported. Additionally, switching participants from etanercept to the biosimilar during the subsequent treatment periods did not cause an increase in formation of antidrug antibodies.21

There are 2 upcoming studies involving biosimilars that are not yet recruiting patients. The first (NCT02925338) will analyze the characteristics of patients treated with Inflectra as well as their response to treatment. The second (NCT02762955) will be comparing the efficacy and safety of an adalimumab biosimilar (BCD-057, BIOCAD) to adalimumab.

Economic Advantages of Biosimilars

The annual economic burden of psoriasis in the United States is substantial, with estimates between $35.2 billion22 and $112 billion.23 Biosimilars can be 25% to 30% cheaper than their reference products9,11,24 and have the potential to save the US health care system billions of dollars.25 Furthermore, the developers of biosimilars could offer patient assistance programs.11 That being said, drug developers can extend patents for their branded drugs; for instance, 2 patents for Enbrel (Amgen Inc) could protect the drug until 2029.26,27

Although cost is an important factor in deciding which medications to prescribe for patients, it should never take precedence over safety and efficacy. Manufacturers can develop new drugs with greater efficacy, fewer side effects, or more convenient dosing schedules,26,27 or they could offer co-payment assistance programs.26,28 Physicians also must consider how the biosimilars will be integrated into drug formularies. Would patients be required to use a biosimilar before a branded drug?11,29 Will patients already taking a branded drug be grandfathered in?11 Would they have to pay a premium to continue taking their drug? And finally, could changes in formularies and employer-payer relationships destabilize patient regimens?30

Conclusion

Preliminary results suggest that biosimilars can have similar safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity data compared to their reference products.19,21 Biosimilars have the potential to greatly reduce the cost burden associated with psoriasis. However, how similar is “highly similar”? Although cost is an important consideration in selecting drug therapies, the reason for using a biosimilar should never be based on cost alone.

- Information on biosimilars. US Food and Drug Administration website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/. Updated May 10, 2016. Accessed July 5, 2016.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Scientific Considerations in Demonstrating Biosimilarity to a Reference Product: Guidance for Industry. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2015.

- McKeage K. A review of CT-P13: an infliximab biosimilar. BioDrugs. 2014;28:313-321.

- FDA approves Inflectra, a biosimilar to Remicade [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; April 5, 2016. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm494227.htm. Updated April 20, 2016. Accessed January 23, 2017.

- FDA approves Erelzi, a biosimilar to Enbrel [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; August 30, 2016. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm518639.htm. Accessed January 23, 2017.

- FDA approves Amjevita, a biosimilar to Humira [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; September 23, 2016. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm522243.htm. Accessed January 23, 2017.

- Scott BJ, Klein AV, Wang J. Biosimilar monoclonal antibodies: a Canadian regulatory perspective on the assessment of clinically relevant differences and indication extrapolation [published online June 26, 2014]. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55(suppl 3):S123-S132.

- Mellstedt H, Niederwieser D, Ludwig H. The challenge of biosimilars [published online September 14, 2007]. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:411-419.

- Puig L. Biosimilars and reference biologics: decisions on biosimilar interchangeability require the involvement of dermatologists [published online October 2, 2013]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:435-437.

- Strober BE, Armour K, Romiti R, et al. Biopharmaceuticals and biosimilars in psoriasis: what the dermatologist needs to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:317-322.

- Falit BP, Singh SC, Brennan TA. Biosimilar competition in the United States: statutory incentives, payers, and pharmacy benefit managers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34:294-301.

- Park W, Hrycaj P, Jeka S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, prospective study comparing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of CT-P13 and innovator infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: the PLANETAS study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1605-1612.

- Yoo DH, Hrycaj P, Miranda P, et al. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study to demonstrate equivalence in efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with innovator infliximab when coadministered with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: the PLANETRA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1613-1620.

- Carretero Hernandez G, Puig L. The use of biosimilar drugs in psoriasis: a position paper. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:249-251.

- Regulation of Biological Products, 42 USC §262 (2013).

- Ventola CL. Evaluation of biosimilars for formulary inclusion: factors for consideration by P&T committees. P T. 2015;40:680-689.

- Park W, Yoo DH, Jaworski J, et al. Comparable long-term efficacy, as assessed by patient-reported outcomes, safety and pharmacokinetics, of CT-P13 and reference infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: 54-week results from the randomized, parallel-group PLANETAS study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:25.

- Yoo DH, Racewicz A, Brzezicki J, et al. A phase III randomized study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of CT-P13 compared with reference infliximab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: 54-week results from the PLANETRA study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;18:82.

- Strober B, Foley P, Philipp S, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of ABP 501 in a phase 3 study in subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: 52-week results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5, suppl 1):AB249.

- Momenta Pharmaceuticals announces positive top-line phase 3 results for M923, a proposed Humira (adalimumab) biosimilar [news release]. Cambridge, MA: Momenta Pharmaceuticals, Inc; November 29, 2016. http://ir.momentapharma.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=1001255. Accessed January 25, 2017.

- Griffiths CE, Thaci D, Gerdes S, et al. The EGALITY study: a confirmatory, randomised, double-blind study comparing the efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of GP2015, a proposed etanercept biosimilar, versus the originator product in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis [published online October 27, 2016]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.15152.

- Vanderpuye-Orgle J, Zhao Y, Lu J, et al. Evaluating the economic burden of psoriasis in the United States [published online April 14, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:961-967.

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658.

- Menter MA, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: the future. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:161-166.

- Hackbarth GM, Crosson FJ, Miller ME. Report to the Congress: improving incentives in the Medicare program. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Washington, DC; 2009.

- Lovenworth SJ. The new biosimilar era: the basics, the landscape, and the future. Bloomberg website. http://about.bloomberglaw.com/practitioner-contributions/the-new-biosimilar-era-the-basics-the-landscape-and-the-future. Published September 21, 2012. Accessed July 6, 2016.

- Blackstone EA, Joseph PF. The economics of biosimilars. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013;6:469-478.

- Calvo B, Zuniga L. The US approach to biosimilars: the long-awaited FDA approval pathway. BioDrugs. 2012;26:357-361.

- Lucio SD, Stevenson JG, Hoffman JM. Biosimilars: implications for health-system pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70:2004-2017.

- Barriers to access attributed to formulary changes. Manag Care. 2012;21:41.

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a biosimilar is “highly similar to an FDA-approved biological product, . . . and has no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety and effectiveness.”1 The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation (BPCI) Act of 2009 created an expedited pathway for the approval of products shown to be biosimilar to FDA-licensed reference products.2 In 2013, the European Medicines Agency approved the first biosimilar modeled on infliximab (Remsima [formerly known as CT-P13], Celltrion Healthcare Co, Ltd) for the same indications as its reference product.3 In 2016, the FDA approved Inflectra (Hospira, a Pfizer Company), an infliximab biosimilar; Erelzi (Sandoz, a Novartis Division), an etanercept biosimilar; and Amjevita (Amgen Inc), an adalimumab biosimilar, all for numerous clinical indications including plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.4-6

There has been a substantial amount of distrust surrounding the biosimilars; however, as the patents for the biologic agents expire, new biosimilars will undoubtedly flood the market. In this article, we provide information that will help dermatologists understand the need for and use of these agents.

Biosimilars Versus Generic Drugs

Small-molecule generics can be made in a process that is relatively inexpensive, reproducible, and able to yield identical products with each lot.7 In contrast, biosimilars are large complex proteins made in living cells. They differ from their reference product because of changes that occur during manufacturing (eg, purification system, posttranslational modifications).7-9 Glycosylation is particularly sensitive to manufacturing and can affect the immunogenicity of the product.9 The impact of manufacturing can be substantial; for example, during phase 3 trials for efalizumab, a change in the manufacturing facility affected pharmacokinetic properties to such a degree that the FDA required a repeat of the trials.10

FDA Guidelines on Biosimilarity

The FDA outlines the following approach to demonstrate biosimilarity.2 The first step is structural characterization to evaluate the primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures and posttranslational modifications. The next step utilizes in vivo and/or in vitro functional assays to compare the biosimilar and reference product. The third step is a focus on toxicity and immunogenicity. The fourth step involves clinical studies to study pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, immunogenicity, safety, and efficacy. After the biosimilar has been approved, there must be a system in place to monitor postmarketing safety. If a biosimilar is tested in one patient population (eg, patients with plaque psoriasis), a request can be made to approve the drug for all the conditions that the reference product was approved for, such as plaque psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease, even though clinical trials were not performed in all of these patient populations.2 The BPCI Act leaves it up to the FDA to determine how much and what type of data (eg, in vitro, in vivo, clinical) are required.11

Extrapolation and Interchangeability

Once a biosimilar has been approved, 2 questions must be answered: First, can its use be extrapolated to all indications for the reference product? The infliximab biosimilar approved by the European Medicines Agency and the FDA had only been studied in patients with ankylosing spondylitis12 and rheumatoid arthritis,13 yet it was granted all the indications for infliximab, including severe plaque psoriasis.14 As of now, the various regulatory agencies differ on their policies regarding extrapolation. Extrapolation is not automatically bestowed on a biosimilar in the United States but can be requested by the manufacturer.2

Second, can the biosimilar be seamlessly switched with its reference product at the pharmacy level? The BPCI Act allows for the substitution of biosimilars that are deemed interchangeable without notifying the provider, yet individual states ultimately can pass laws regarding this issue.15,16 An interchangeable agent would “produce the same clinical result as the reference product,” and “the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy of alternating or switching between use of the biological product and the reference product is not greater than the risk of using the reference product.”15 Generic drugs are allowed to be substituted without notifying the patient or prescriber16; however, biosimilars that are not deemed interchangeable would require permission from the prescriber before substitution.11

Biosimilars for Psoriasis

In April 2016, an infliximab biosimilar (Inflectra) became the second biosimilar approved by the FDA.4 Inflectra was studied in clinical trials for patients with ankylosing spondylitis17 and rheumatoid arthritis,18 and in both trials the biosimilar was found to have similar efficacy and safety profiles to that of the reference product. In August 2016, an etanercept biosimilar (Erelzi) was approved,5 and in September 2016, an adalimumab biosimilar (Amjevita) was approved.6

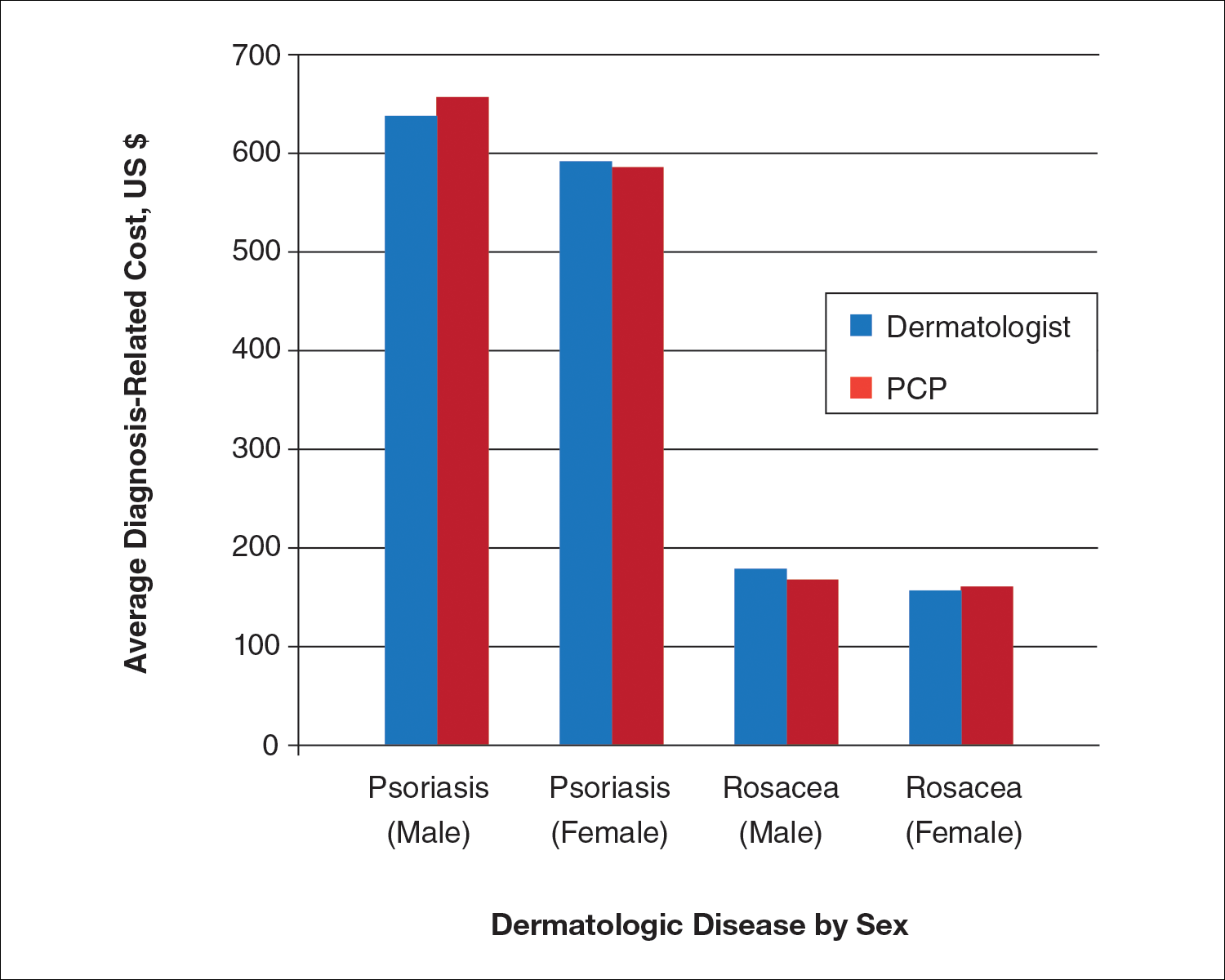

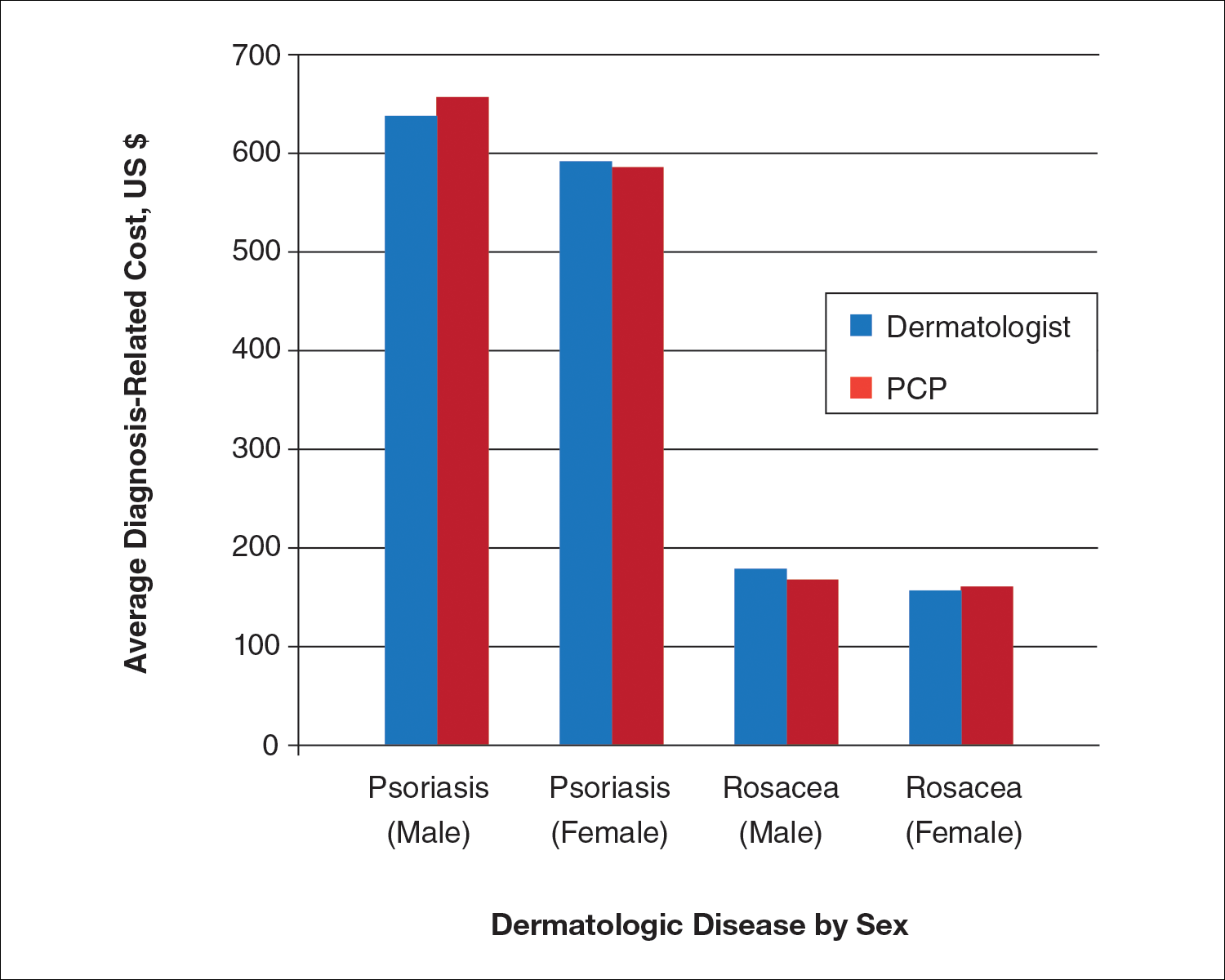

The Table summarizes clinical trials (both completed and ongoing) evaluating biosimilars in adults with plaque psoriasis; thus far, there are 2464 participants enrolled across 5 different studies of adalimumab biosimilars (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifiers NCT01970488, NCT02016105, NCT02489227, NCT02714322, NCT02581345) and 531 participants in an etanercept biosimilar study (NCT01891864).

A phase 3 double-blind study compared adalimumab to an adalimumab biosimilar (ABP 501) in 350 adults with plaque psoriasis (NCT01970488). Participants received an initial loading dose of adalimumab (n=175) or ABP 501 (n=175) 80 mg subcutaneously on week 1/day 1, followed by 40 mg at week 2 every 2 weeks thereafter. At week 16, participants with psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) 50 or greater remained in the study for up to 52 weeks; those who were receiving adalimumab were re-randomized to receive either ABP 501 or adalimumab. Participants receiving ABP 501 continued to receive the biosimilar. The mean PASI improvement at weeks 16, 32, and 50 was 86.6, 87.6, and 87.2, respectively, in the ABP 501/ABP 501 group (A/A) compared to 88.0, 88.2, and 88.1, respectively, in the adalimumab/adalimumab group (B/B).19 Autoantibodies developed in 68.4% of participants in the A/A group compared to 74.7% in the B/B group. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was 86.2% in the A/A group and 78.5% in the B/B group. The most common TEAEs were nasopharyngitis, headache, and upper respiratory tract infection. The incidence of serious TEAEs was 4.6% in the A/A group compared to 5.1% in the B/B group. Overall, the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the adalimumab biosimilar was comparable to the reference product.19

A second phase 3 trial (ADACCESS) evaluated the adalimumab biosimilar GP2017 (NCT02016105). Participants received an initial dose of 80 mg subcutaneously of either GP2017 or adalimumab at week 0, followed by 40 mg every other week starting at week 1 and ending at week 51. The study has been completed but results are not yet available.

The third trial is evaluating the adalimumab biosimilar CHS-1420 (NCT02489227). Participants in the experimental arm receive two 40-mg doses of CHS-1420 at week 0/day 0, and then 1 dose every 2 weeks from week 1 for 23 weeks. At week 24, participants continue with an open-label study. Participants in the adalimumab group receive two 40-mg doses at week 0/day 0, and then 1 dose every 2 weeks from week 1 to week 15. At week 16, participants will be re-randomized (1:1) to continue adalimumab or start CHS-1420 at one 40-mg dose every 2 weeks during weeks 17 to 23. At week 24, participants will switch to CHS-1420 open label until the end of the study. Study results are not yet available; the study is ongoing but not recruiting.

The fourth ongoing trial is evaluating the adalimumab biosimilar MYL-1401A (NCT02714322). Participants receive an initial dose of 80 mg subcutaneously of either MYL-1401A or adalimumab (2:1), followed by 40 mg every other week starting 1 week after the initial dose. After the 52-week treatment period, there is an 8-week safety follow-up period. Study results are not yet available; the study is ongoing but not recruiting.

A fifth adalimumab biosimilar, M923, also is currently being tested in clinical trials (NCT02581345). Participants receive either M923, adalimumab, or alternate between the 2 agents. Although the study is still ongoing, data released from the manufacturer state that the proportion of participants who achieved PASI 75 after 16 weeks of treatment was equivalent in the 2 treatment groups. The proportion of participants who achieved PASI 90, as well as the type, frequency, and severity of adverse events, also were comparable.20