User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Diffuse Urticarial Rash in a Pregnant Patient

The Diagnosis: Pemphigoid Gestationis

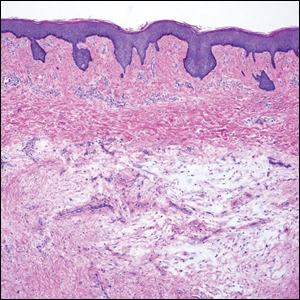

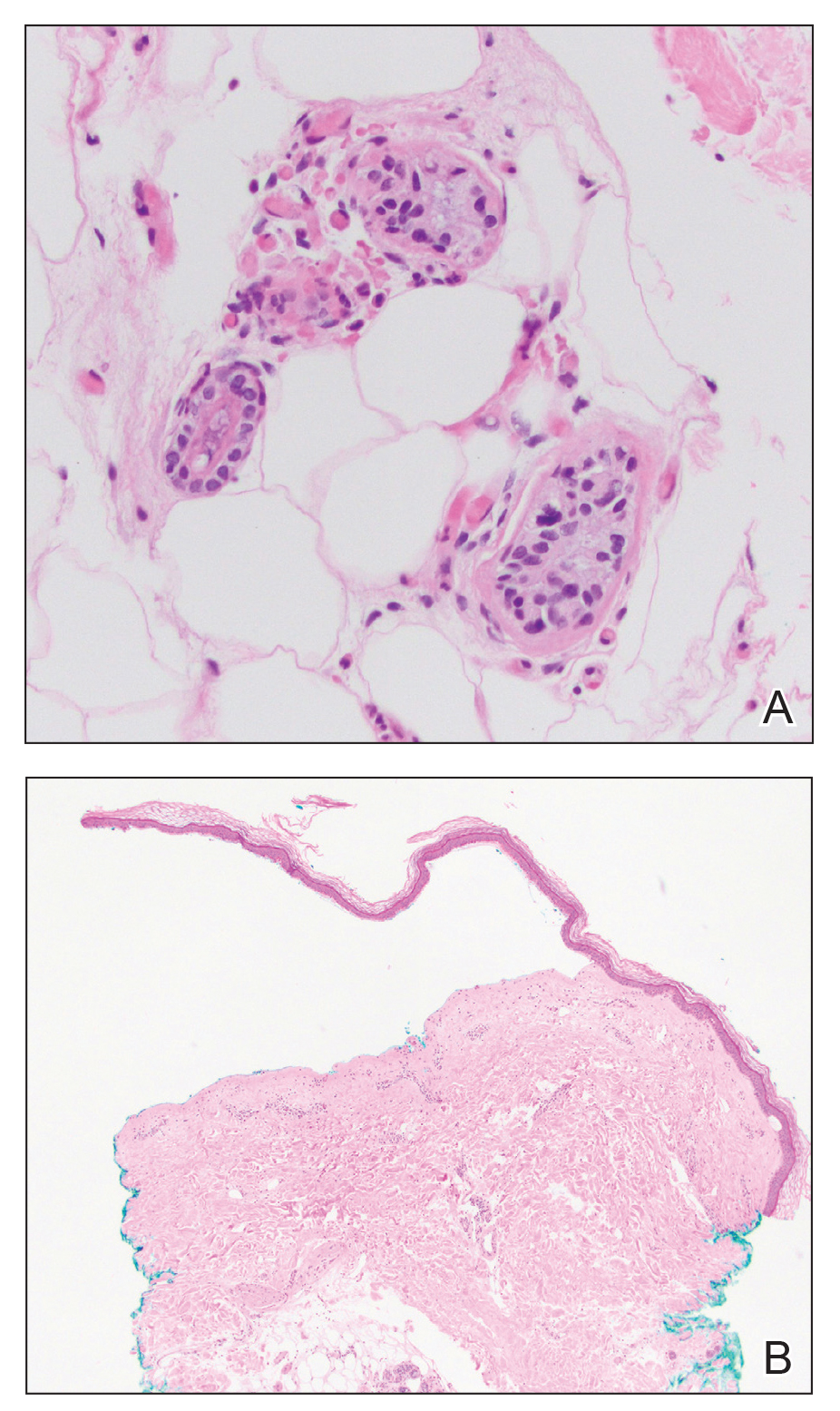

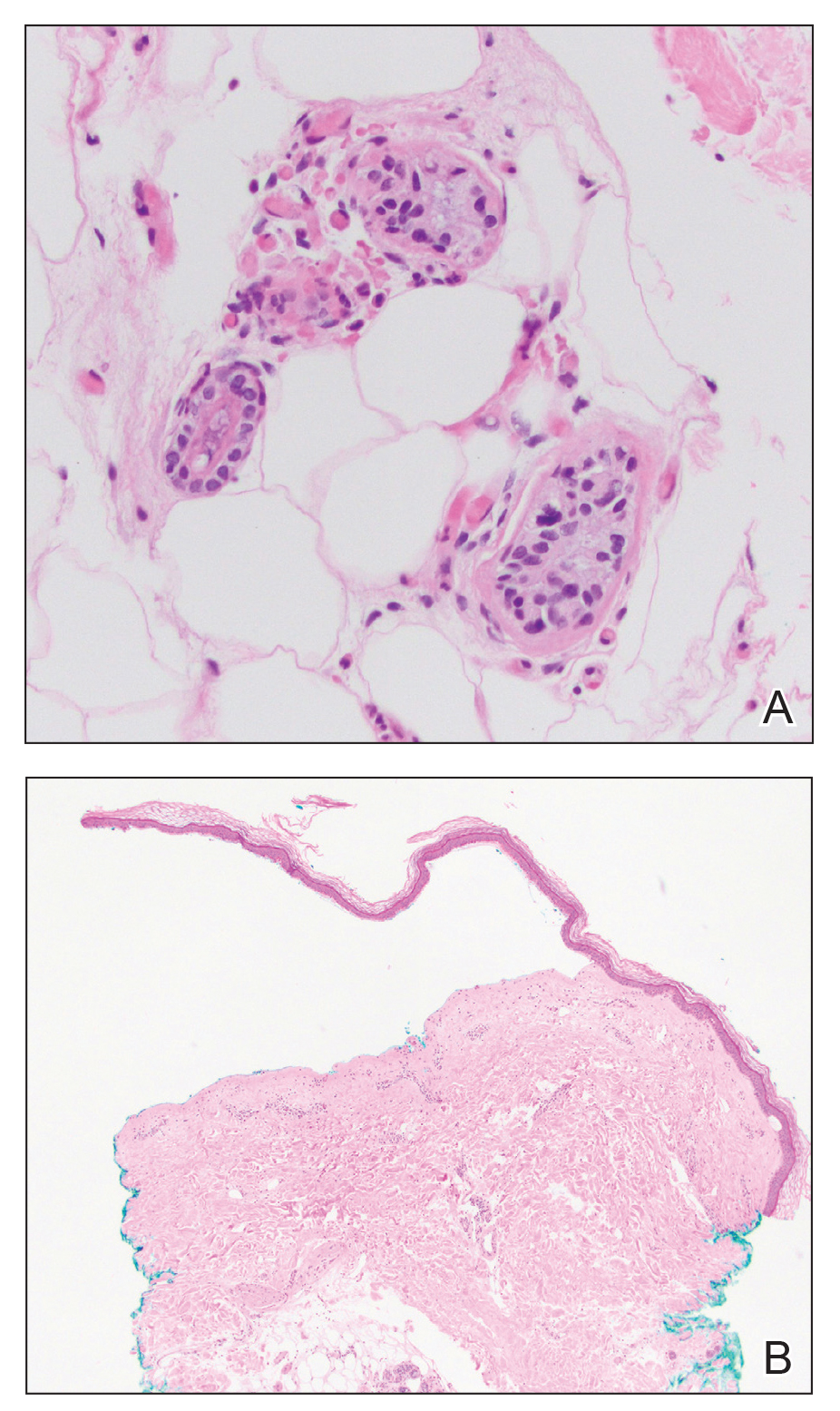

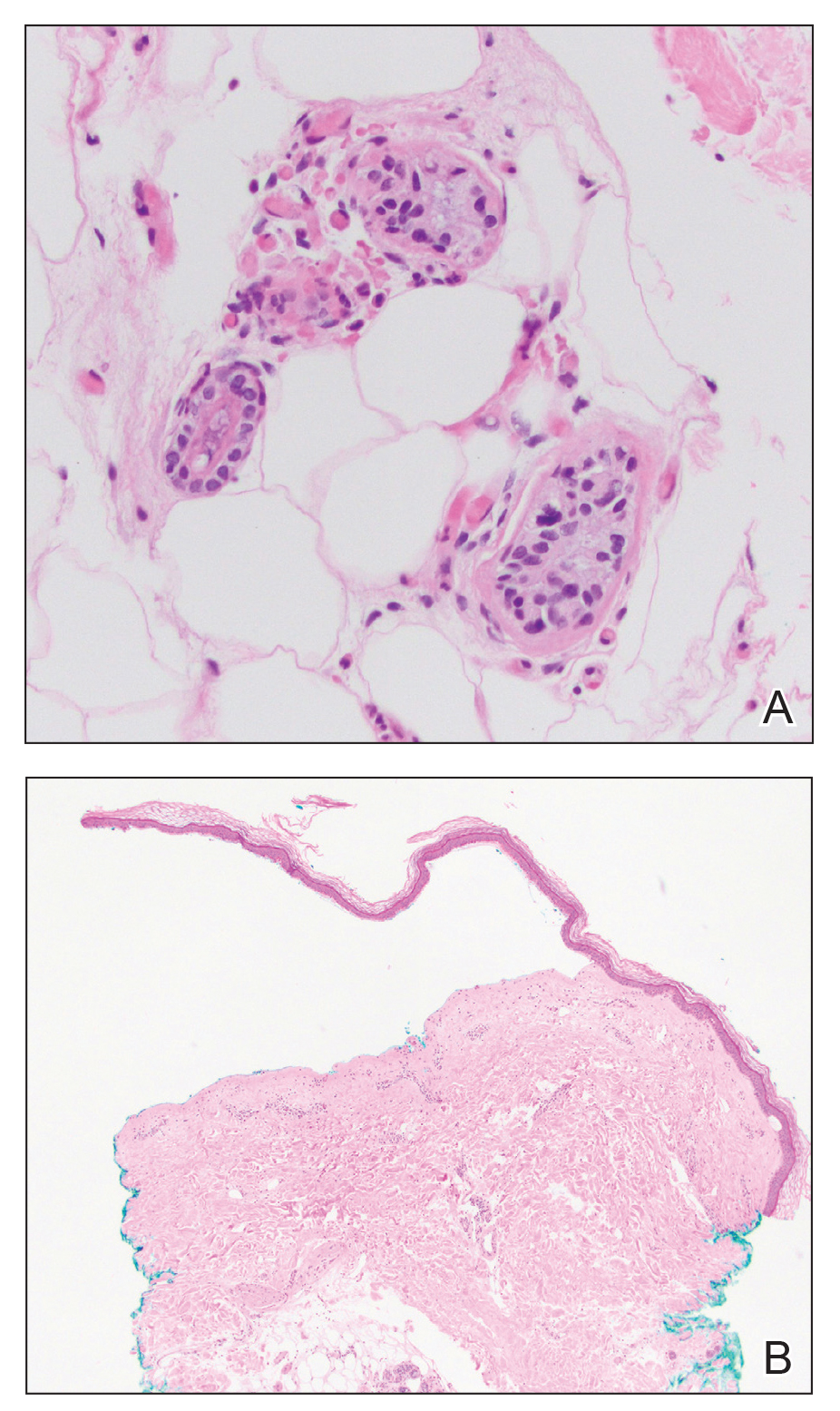

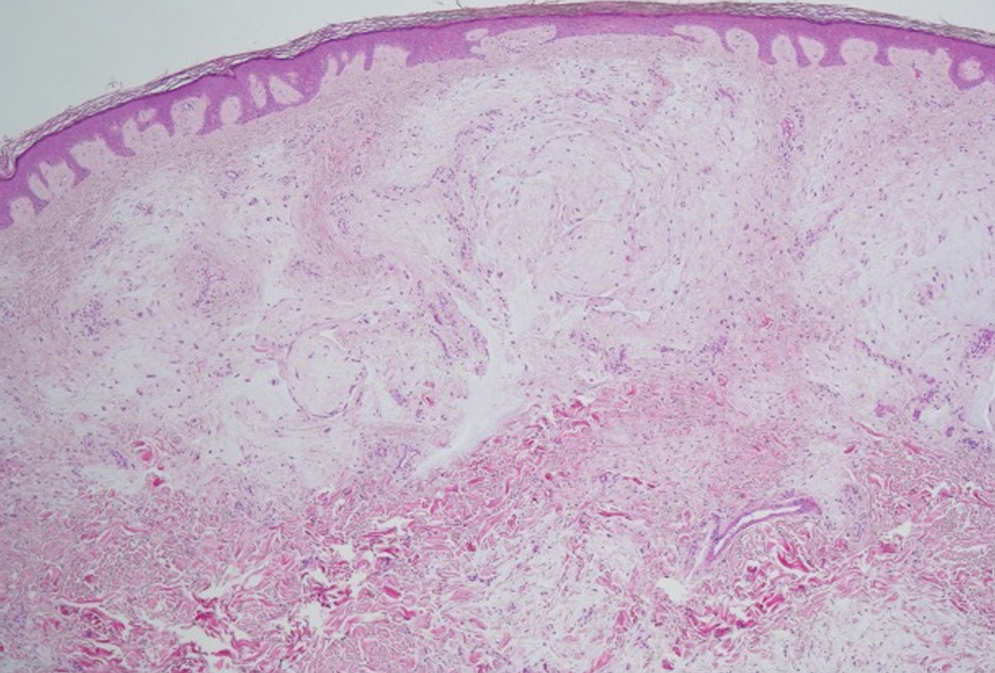

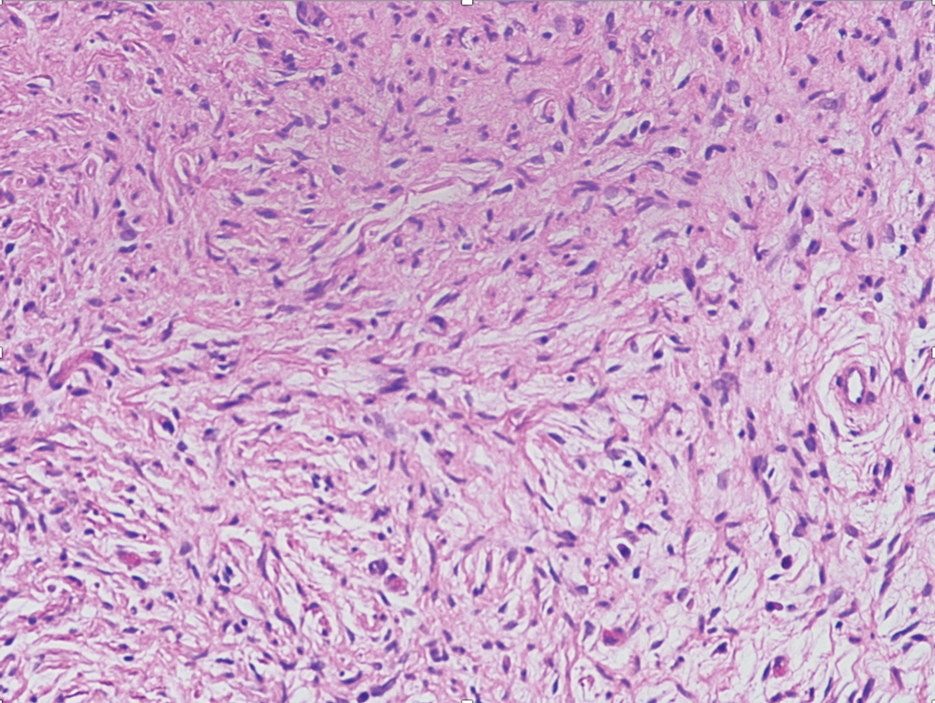

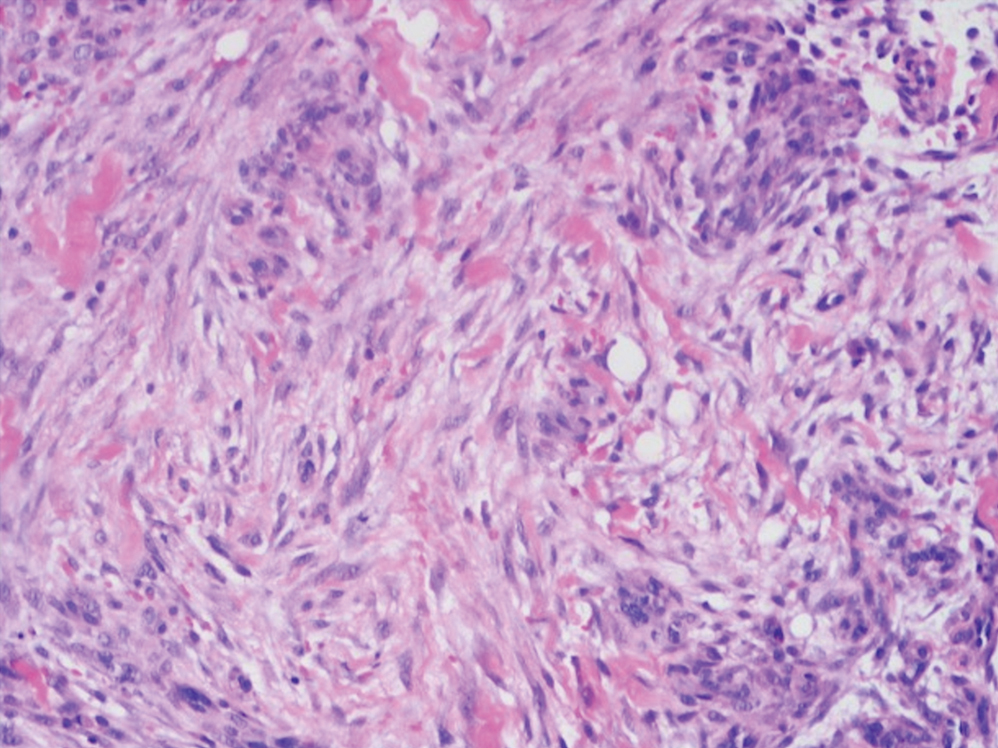

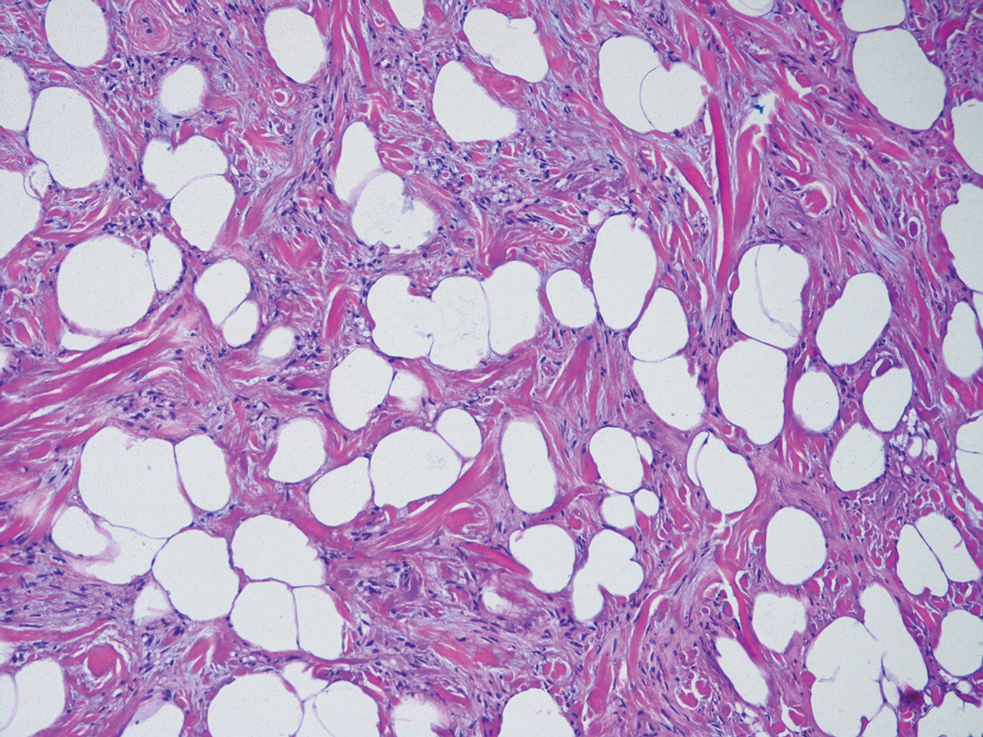

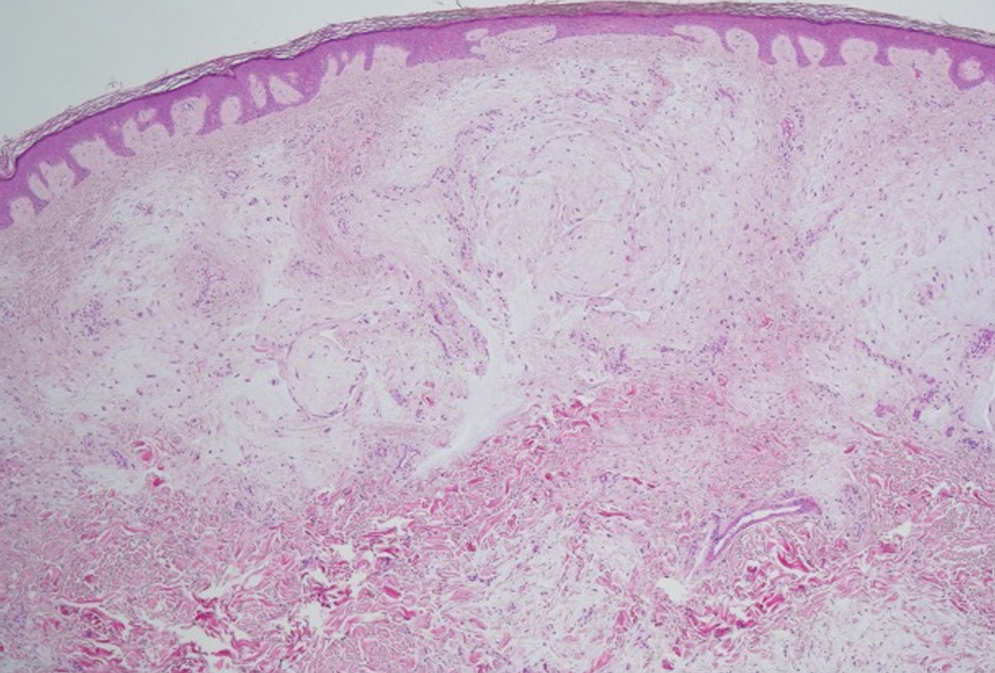

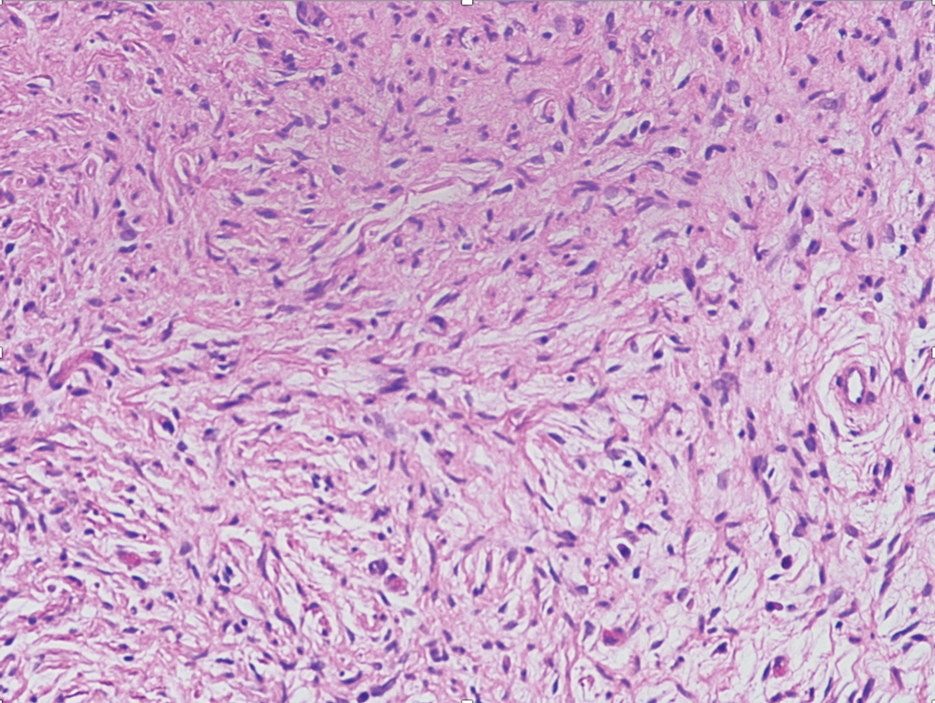

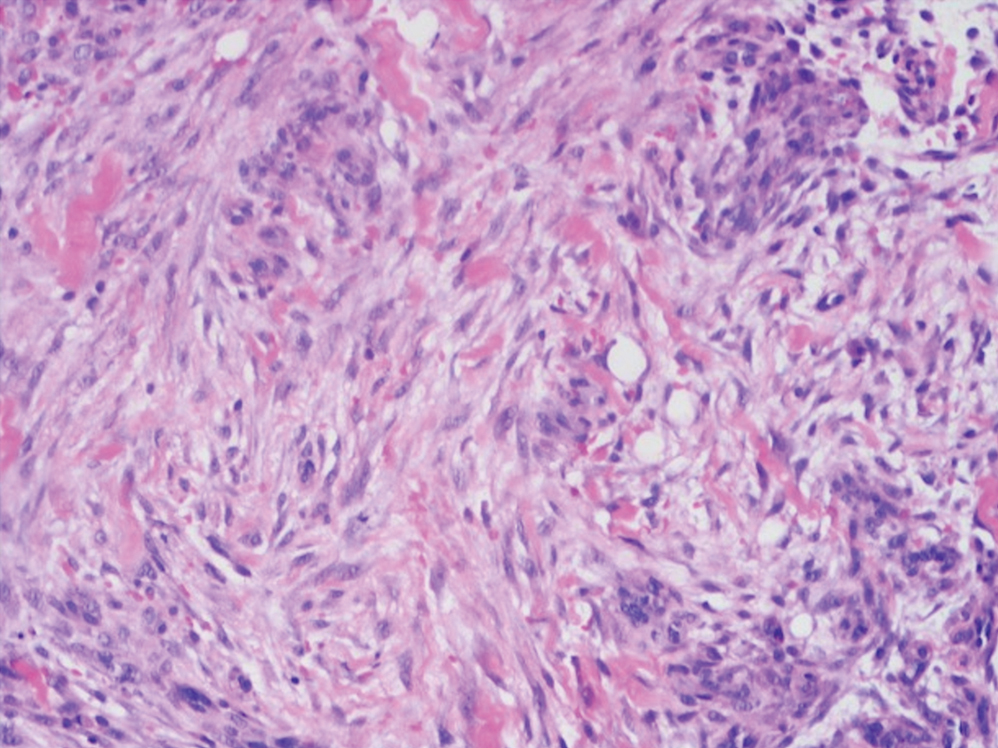

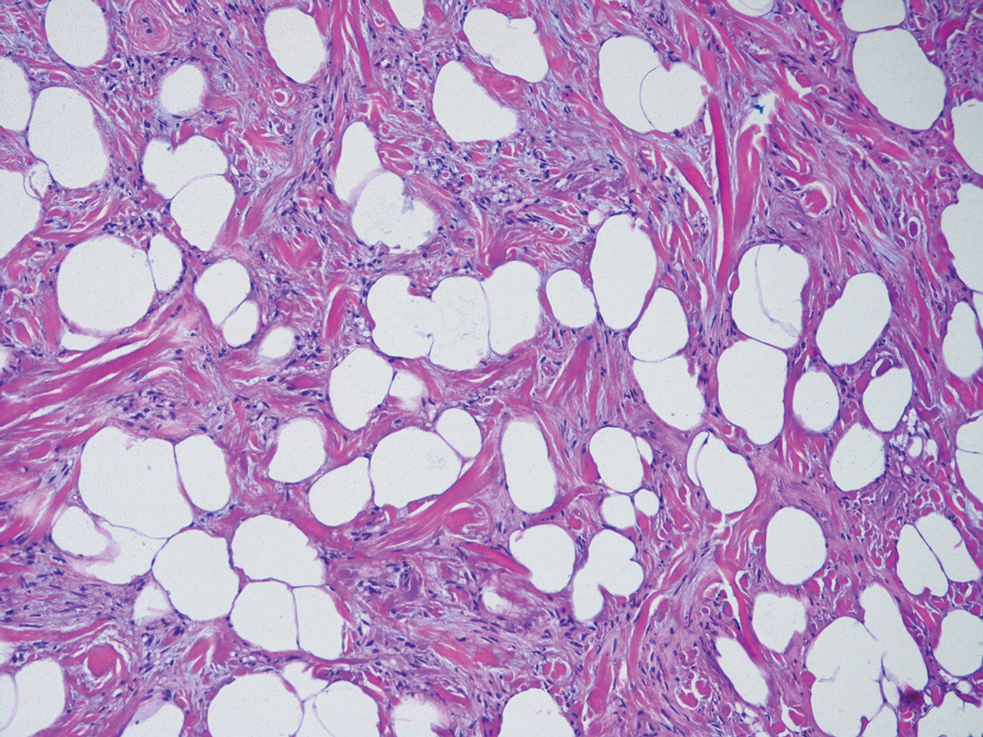

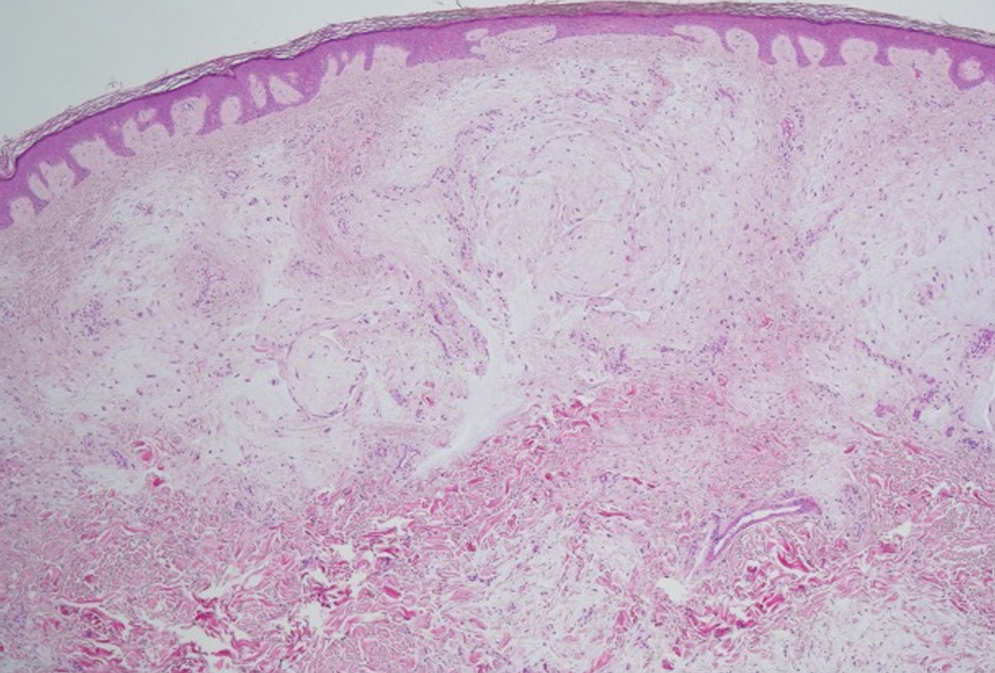

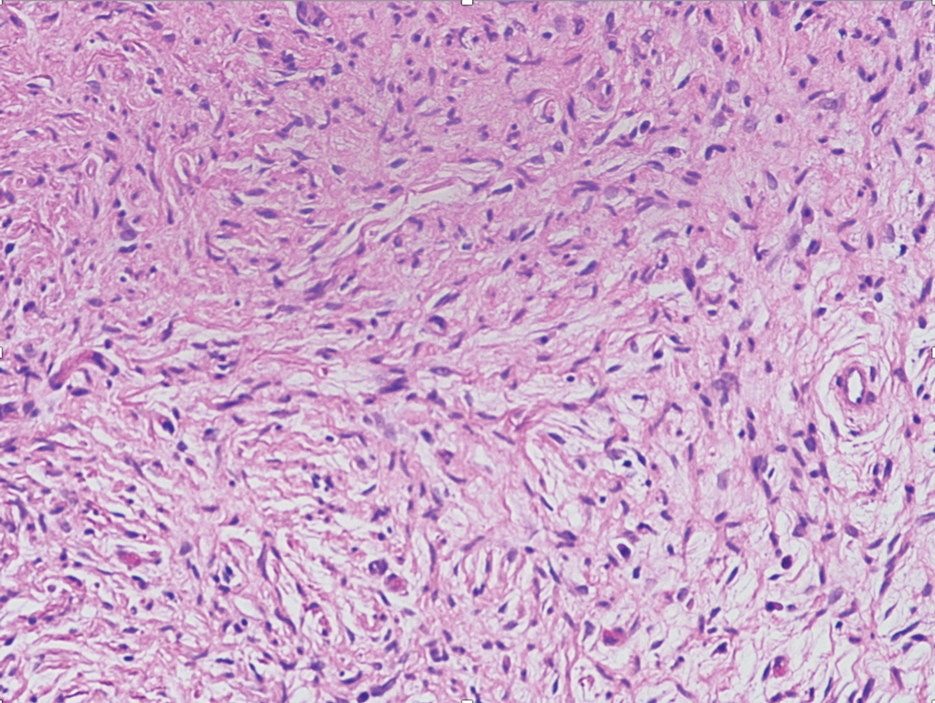

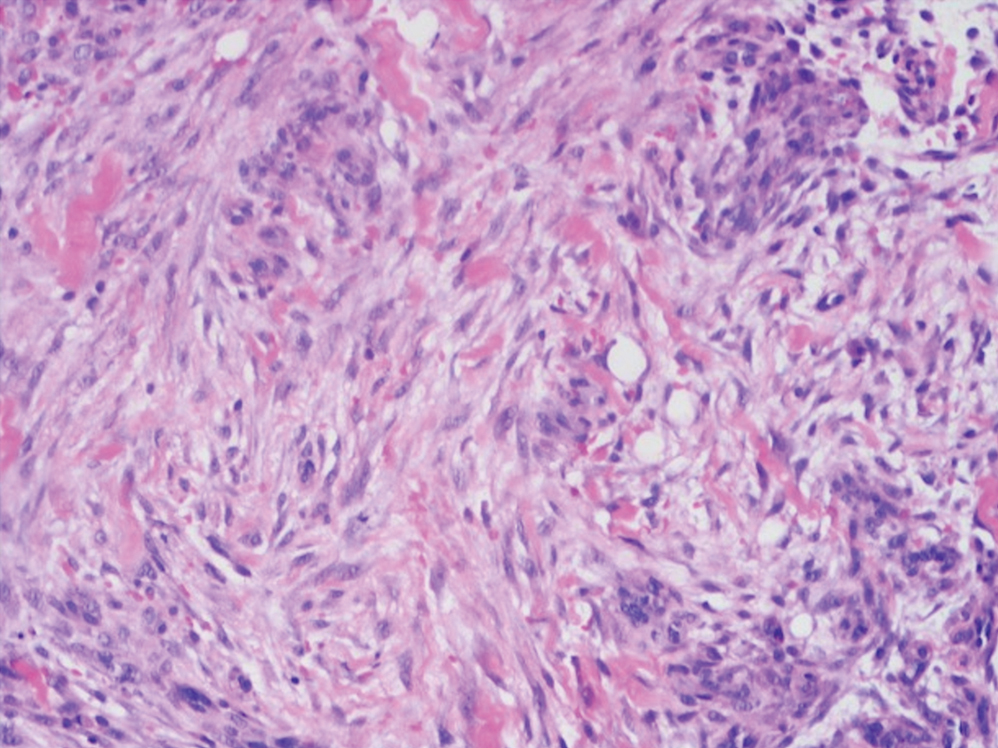

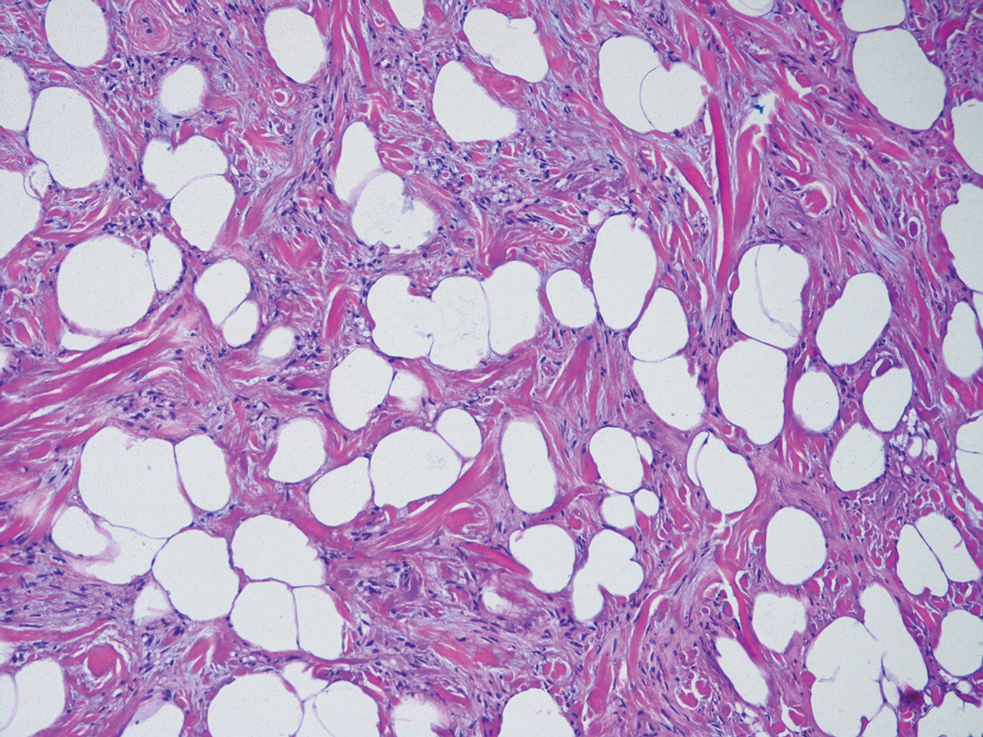

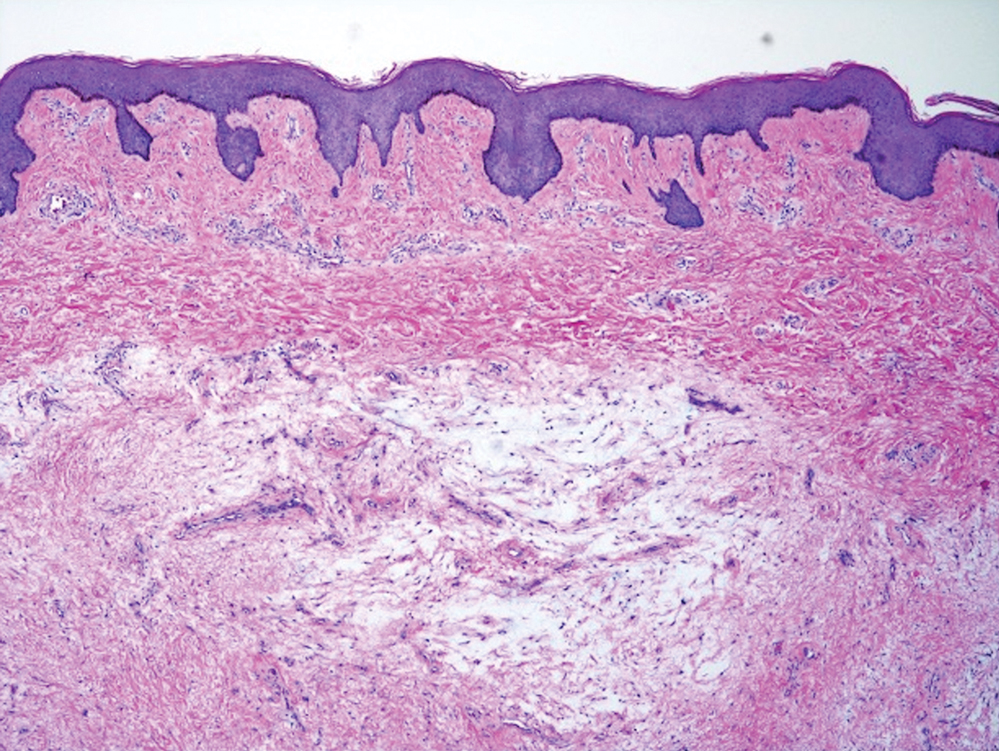

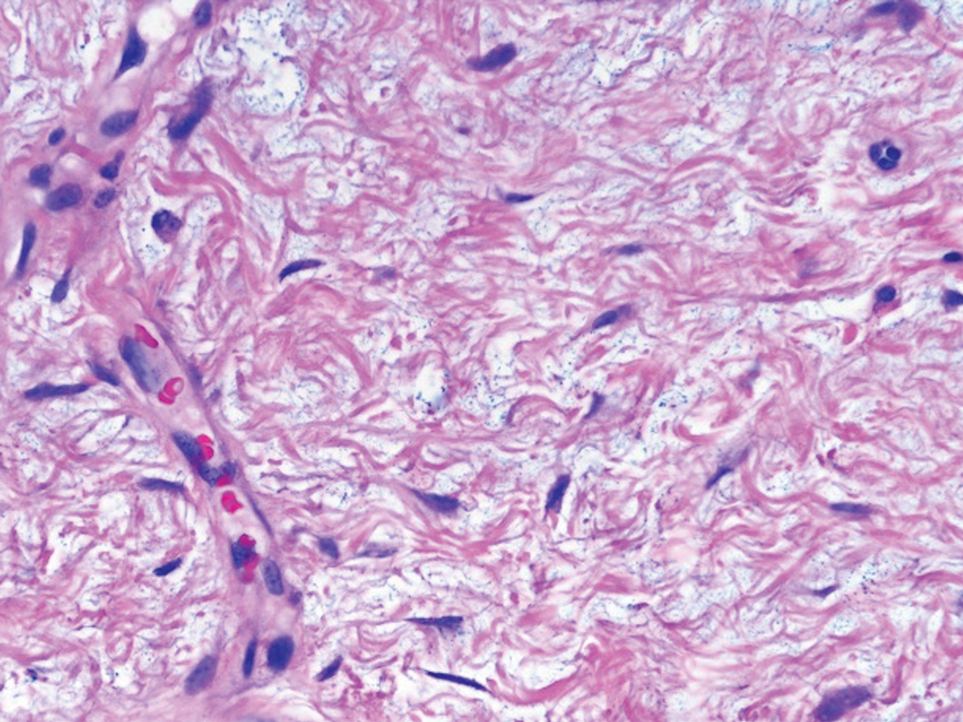

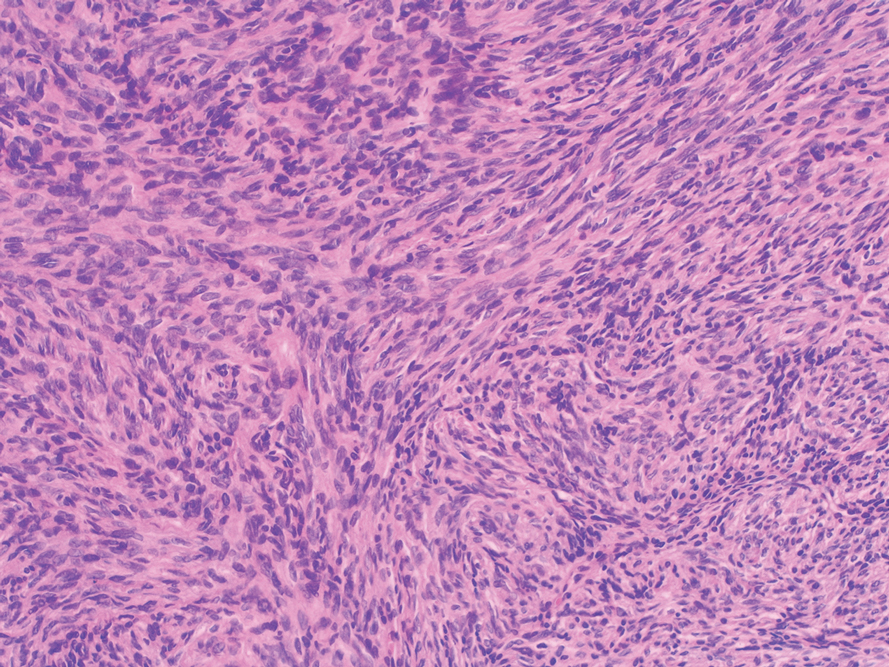

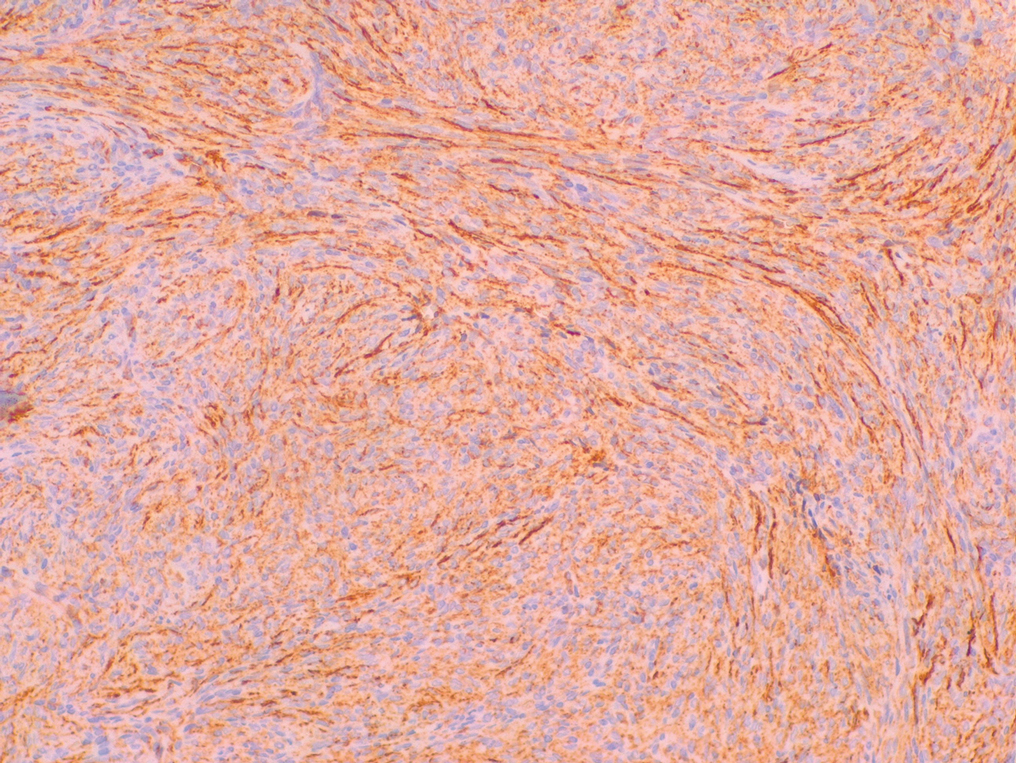

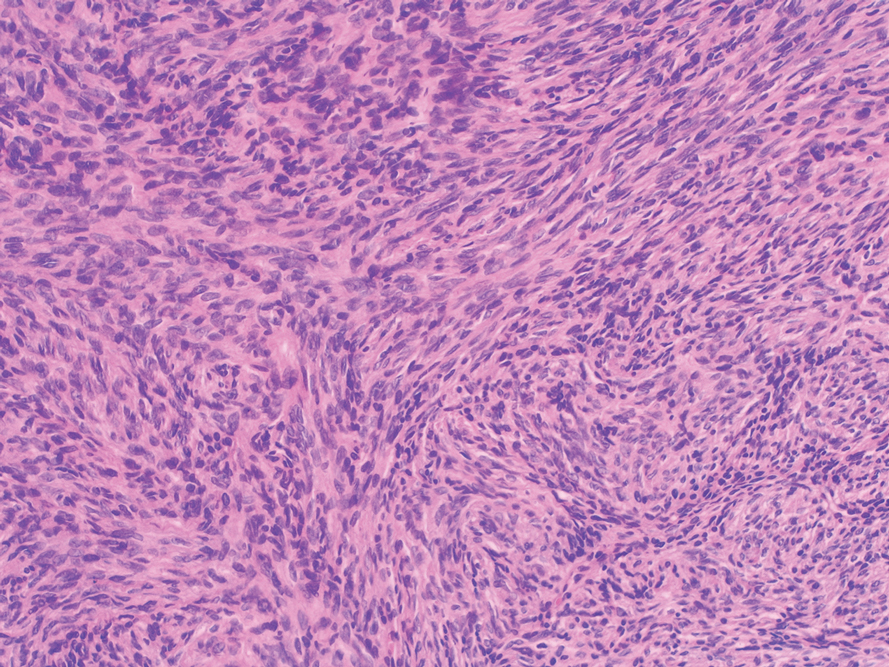

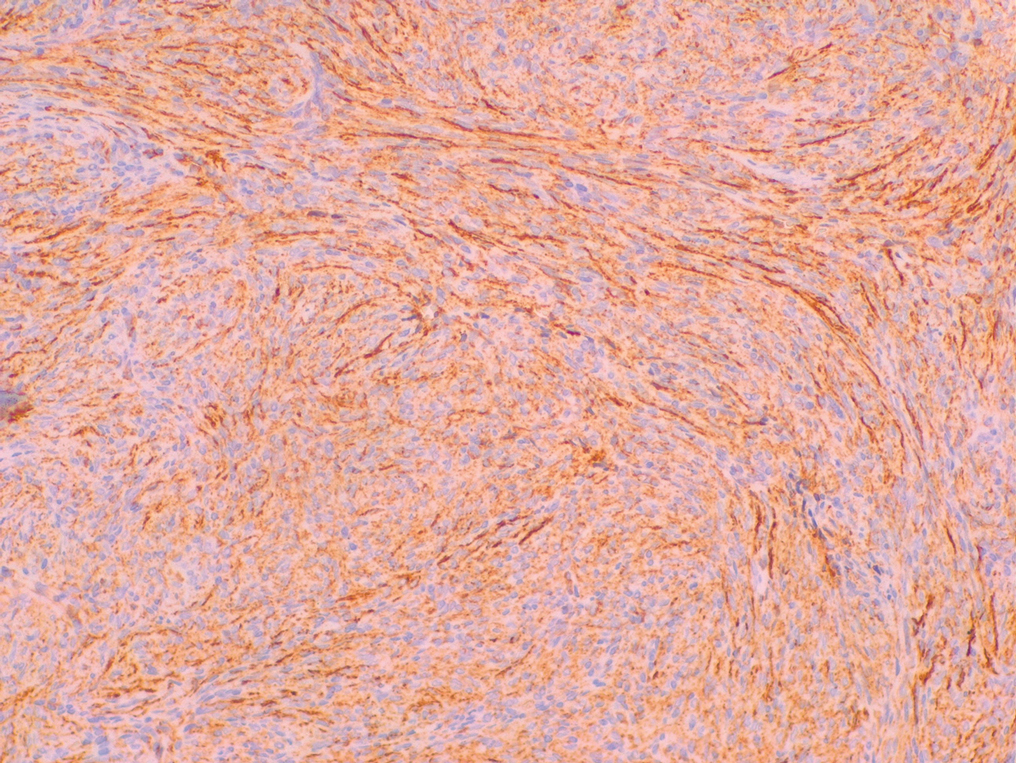

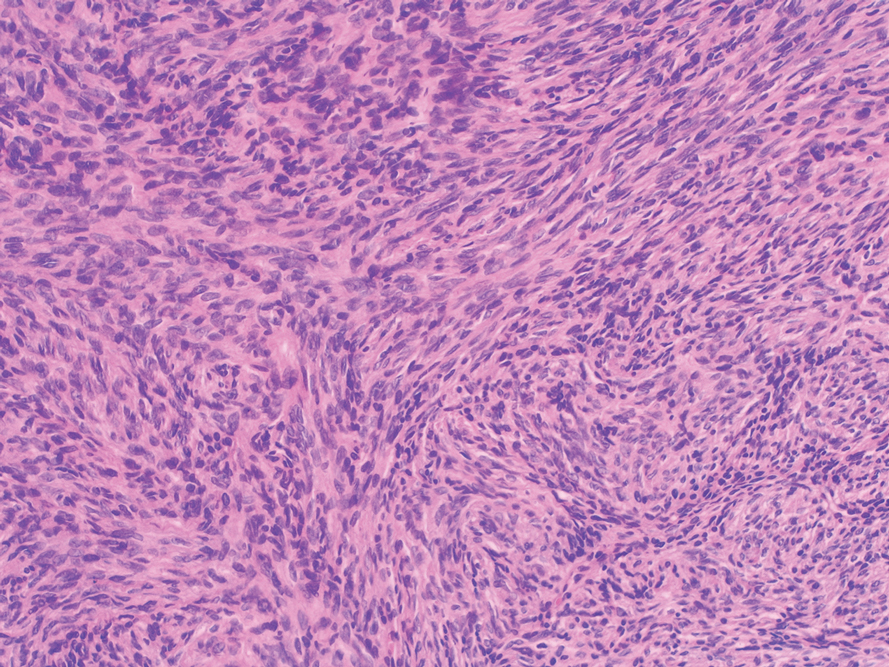

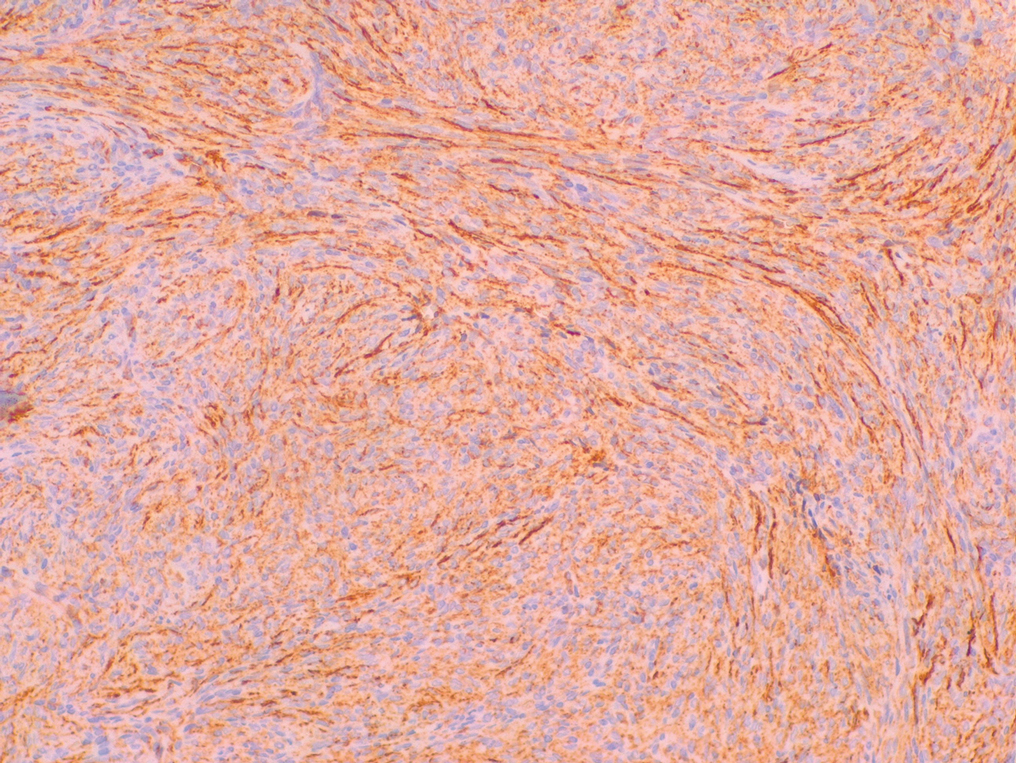

A lesional biopsy showed a subepidermal split with eosinophils and neutrophils. Perilesional biopsy for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed linear deposition of 3+ C3 along the basement membrane zone. The clinical, histopathologic, and immunofluorescent findings were consistent with pemphigoid gestationis (PG). Prednisone 1 mg/kg daily was initiated. Her condition continued to worsen, and cyclosporine 250 mg daily was added while prednisone was tapered, with remission of disease.

Pemphigoid gestationis is an autoimmune bullous dermatosis that occurs in the second or third trimester of pregnancy, with an incidence of 1 in 50,000 to 60,000 pregnancies.1 In terms of pathogenesis, aberrant expression of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules on placental tissues causes the loss of immune tolerance of the placenta, which leads to the production of antibodies against the placental protein bullous pemphigoid 180.2 Bullous pemphigoid 180 also is a hemidesmosomal protein found in the skin of the mother; therefore, the presence of the circulating antibodies leads to separation at the dermoepidermal junction and vesiculation.

Pemphigoid gestationis is characterized by the sudden eruption of intensely pruritic urticarial papules and plaques, classically with periumbilical involvement. Tense vesicles and bullae can develop. Women with PG have an increased risk for development of Graves disease. Histopathology shows subepidermal vesiculation with a predominance of eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence classically shows linear deposition of C3 along the basement membrane zone. Fetal complications include prematurity and small size for gestational age. Additionally, blisters can be seen in 5% to 10% of neonates due to placental transmission of autoantibodies.3

Frequently PG flares shortly postpartum. Pemphigoid gestationis resolves within 6 months postdelivery but frequently reoccurs in subsequent pregnancies. Mild disease can be treated with mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids. Severe disease is managed with oral corticosteroids, most commonly prednisone. Refractory disease is managed with azathioprine, cyclosporine, intravenous immunoglobulin, or plasmapheresis.

The differential diagnosis of PG includes other pregnancy-associated dermatoses such as atopic eruption of pregnancy, impetigo herpetiformis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and polymorphous eruption of pregnancy. Atopic eruption of pregnancy is the most common dermatosis of pregnancy and is characterized by an eczematous eruption in patients with an atopic history, typically in the first trimester. Blisters are not seen, and DIF is negative. Impetigo herpetiformis, or pustular psoriasis of pregnancy, is a variant of generalized pustular psoriasis that occurs during pregnancy. Diffuse erythematous patches studded with pustules, rather than vesicles, are seen; DIF is negative. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy presents without primary skin findings and severe pruritus predominantly on the palms and soles, often with secondary excoriations. Polymorphous eruption of pregnancy presents as a polymorphous eruption of urticarial to erythematous papules and plaques commonly originating in striae. In contrast to PG, there is periumbilical sparing, vesiculation is rare, and DIF is negative.

- Shornick JK, Bangert JL, Freeman RG, et al. Herpes gestationis: clinical and histologic features of twenty-eight cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:214-224.

- Sadik CD, Lima AL, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid gestationis: toward a better understanding of the etiopathogenesis. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:378-382.

- Shornick JK, Black MM. Fetal risks in herpes gestationis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:63-68.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigoid Gestationis

A lesional biopsy showed a subepidermal split with eosinophils and neutrophils. Perilesional biopsy for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed linear deposition of 3+ C3 along the basement membrane zone. The clinical, histopathologic, and immunofluorescent findings were consistent with pemphigoid gestationis (PG). Prednisone 1 mg/kg daily was initiated. Her condition continued to worsen, and cyclosporine 250 mg daily was added while prednisone was tapered, with remission of disease.

Pemphigoid gestationis is an autoimmune bullous dermatosis that occurs in the second or third trimester of pregnancy, with an incidence of 1 in 50,000 to 60,000 pregnancies.1 In terms of pathogenesis, aberrant expression of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules on placental tissues causes the loss of immune tolerance of the placenta, which leads to the production of antibodies against the placental protein bullous pemphigoid 180.2 Bullous pemphigoid 180 also is a hemidesmosomal protein found in the skin of the mother; therefore, the presence of the circulating antibodies leads to separation at the dermoepidermal junction and vesiculation.

Pemphigoid gestationis is characterized by the sudden eruption of intensely pruritic urticarial papules and plaques, classically with periumbilical involvement. Tense vesicles and bullae can develop. Women with PG have an increased risk for development of Graves disease. Histopathology shows subepidermal vesiculation with a predominance of eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence classically shows linear deposition of C3 along the basement membrane zone. Fetal complications include prematurity and small size for gestational age. Additionally, blisters can be seen in 5% to 10% of neonates due to placental transmission of autoantibodies.3

Frequently PG flares shortly postpartum. Pemphigoid gestationis resolves within 6 months postdelivery but frequently reoccurs in subsequent pregnancies. Mild disease can be treated with mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids. Severe disease is managed with oral corticosteroids, most commonly prednisone. Refractory disease is managed with azathioprine, cyclosporine, intravenous immunoglobulin, or plasmapheresis.

The differential diagnosis of PG includes other pregnancy-associated dermatoses such as atopic eruption of pregnancy, impetigo herpetiformis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and polymorphous eruption of pregnancy. Atopic eruption of pregnancy is the most common dermatosis of pregnancy and is characterized by an eczematous eruption in patients with an atopic history, typically in the first trimester. Blisters are not seen, and DIF is negative. Impetigo herpetiformis, or pustular psoriasis of pregnancy, is a variant of generalized pustular psoriasis that occurs during pregnancy. Diffuse erythematous patches studded with pustules, rather than vesicles, are seen; DIF is negative. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy presents without primary skin findings and severe pruritus predominantly on the palms and soles, often with secondary excoriations. Polymorphous eruption of pregnancy presents as a polymorphous eruption of urticarial to erythematous papules and plaques commonly originating in striae. In contrast to PG, there is periumbilical sparing, vesiculation is rare, and DIF is negative.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigoid Gestationis

A lesional biopsy showed a subepidermal split with eosinophils and neutrophils. Perilesional biopsy for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed linear deposition of 3+ C3 along the basement membrane zone. The clinical, histopathologic, and immunofluorescent findings were consistent with pemphigoid gestationis (PG). Prednisone 1 mg/kg daily was initiated. Her condition continued to worsen, and cyclosporine 250 mg daily was added while prednisone was tapered, with remission of disease.

Pemphigoid gestationis is an autoimmune bullous dermatosis that occurs in the second or third trimester of pregnancy, with an incidence of 1 in 50,000 to 60,000 pregnancies.1 In terms of pathogenesis, aberrant expression of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules on placental tissues causes the loss of immune tolerance of the placenta, which leads to the production of antibodies against the placental protein bullous pemphigoid 180.2 Bullous pemphigoid 180 also is a hemidesmosomal protein found in the skin of the mother; therefore, the presence of the circulating antibodies leads to separation at the dermoepidermal junction and vesiculation.

Pemphigoid gestationis is characterized by the sudden eruption of intensely pruritic urticarial papules and plaques, classically with periumbilical involvement. Tense vesicles and bullae can develop. Women with PG have an increased risk for development of Graves disease. Histopathology shows subepidermal vesiculation with a predominance of eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence classically shows linear deposition of C3 along the basement membrane zone. Fetal complications include prematurity and small size for gestational age. Additionally, blisters can be seen in 5% to 10% of neonates due to placental transmission of autoantibodies.3

Frequently PG flares shortly postpartum. Pemphigoid gestationis resolves within 6 months postdelivery but frequently reoccurs in subsequent pregnancies. Mild disease can be treated with mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids. Severe disease is managed with oral corticosteroids, most commonly prednisone. Refractory disease is managed with azathioprine, cyclosporine, intravenous immunoglobulin, or plasmapheresis.

The differential diagnosis of PG includes other pregnancy-associated dermatoses such as atopic eruption of pregnancy, impetigo herpetiformis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and polymorphous eruption of pregnancy. Atopic eruption of pregnancy is the most common dermatosis of pregnancy and is characterized by an eczematous eruption in patients with an atopic history, typically in the first trimester. Blisters are not seen, and DIF is negative. Impetigo herpetiformis, or pustular psoriasis of pregnancy, is a variant of generalized pustular psoriasis that occurs during pregnancy. Diffuse erythematous patches studded with pustules, rather than vesicles, are seen; DIF is negative. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy presents without primary skin findings and severe pruritus predominantly on the palms and soles, often with secondary excoriations. Polymorphous eruption of pregnancy presents as a polymorphous eruption of urticarial to erythematous papules and plaques commonly originating in striae. In contrast to PG, there is periumbilical sparing, vesiculation is rare, and DIF is negative.

- Shornick JK, Bangert JL, Freeman RG, et al. Herpes gestationis: clinical and histologic features of twenty-eight cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:214-224.

- Sadik CD, Lima AL, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid gestationis: toward a better understanding of the etiopathogenesis. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:378-382.

- Shornick JK, Black MM. Fetal risks in herpes gestationis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:63-68.

- Shornick JK, Bangert JL, Freeman RG, et al. Herpes gestationis: clinical and histologic features of twenty-eight cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:214-224.

- Sadik CD, Lima AL, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid gestationis: toward a better understanding of the etiopathogenesis. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:378-382.

- Shornick JK, Black MM. Fetal risks in herpes gestationis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:63-68.

A 29-year-old pregnant woman at 18 weeks and 5 days of gestation presented with a diffuse, pruritic, blistering rash of 5 weeks’ duration that started on the forearms and generalized to affect the trunk, legs, palms, and soles. Physical examination showed diffuse urticarial papules and plaques with small tense vesicles with an annular configuration on the abdomen and marked periumbilical involvement.

Pruritic Papules on the Trunk, Extremities, and Face

The Diagnosis: Gamasoidosis

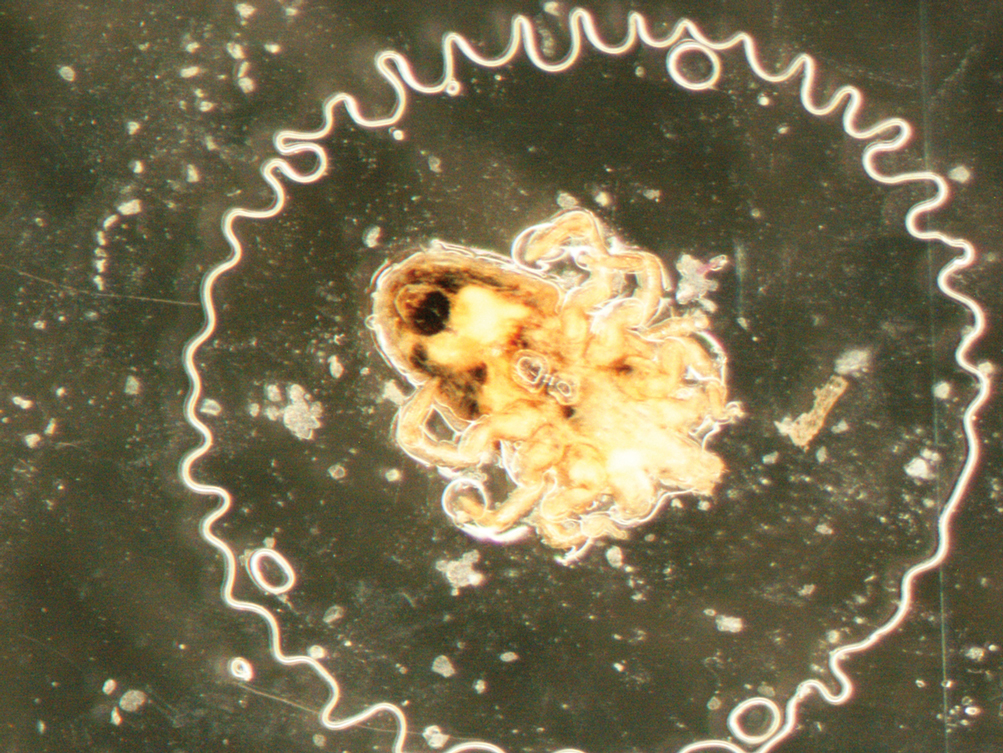

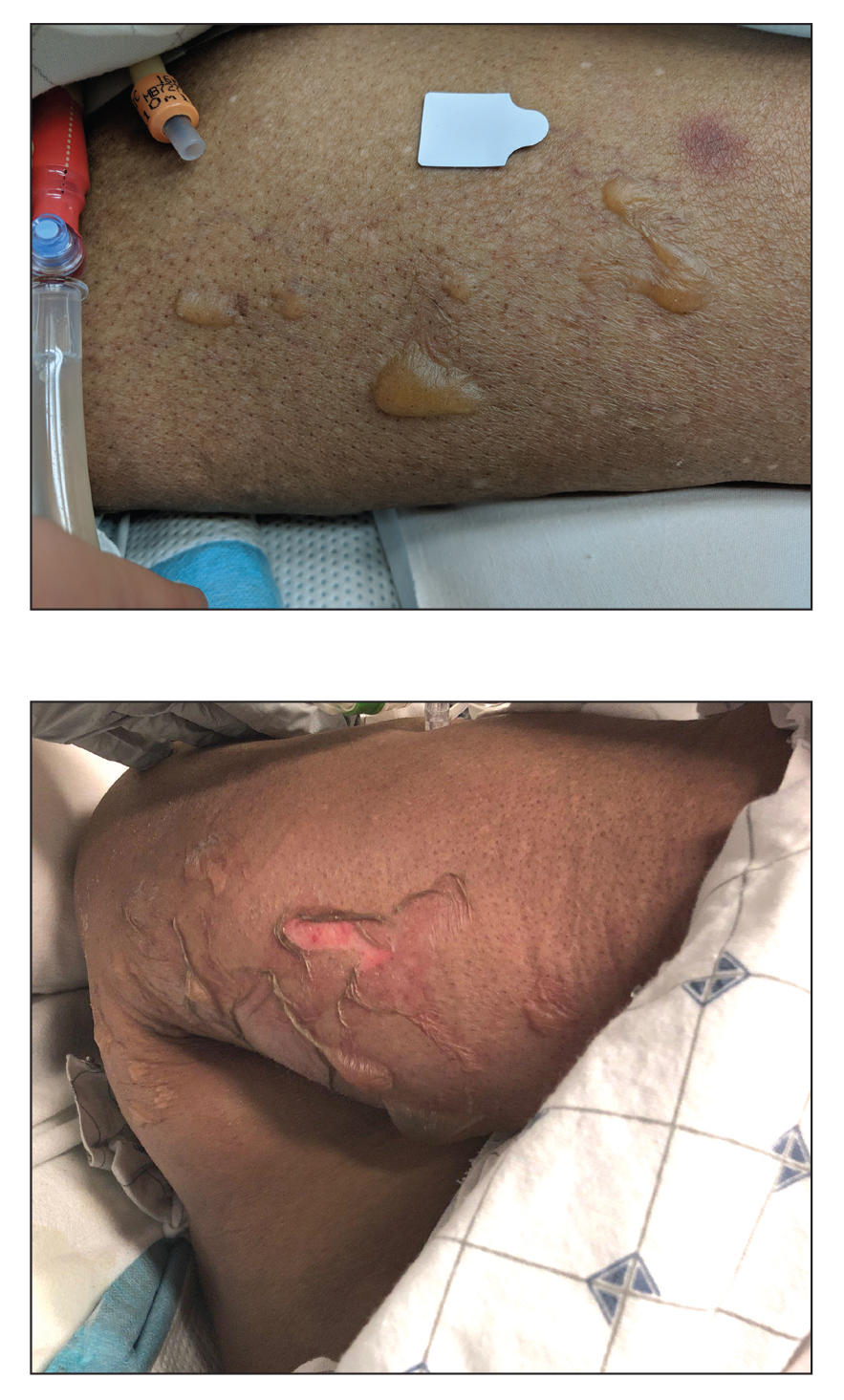

An entomologist confirmed the specimen as an avian mite in either the Dermanyssus or Ornithonyssus genera (quiz image [bottom]). The patient was asked whether any bird had nested around her bedroom, and she affirmed that a woodpecker had nested outside her bedroom closet that spring. She subsequently discovered it had burrowed a hole into her closet wall. She and her husband removed the nest, and within 4 weeks, the eruption permanently cleared.

Gamasoidosis, or avian mite dermatitis, often is an overlooked, difficult-to-make diagnosis that is increasing in prevalence.1 Bird mites are ectoparasitic arthropods that are 0.3 to 1 mm in length. They have egg-shaped bodies with 4 pairs of legs; they are a translucent brown color before feeding and red after feeding.2 Although most avian mites cannot subsist off human blood, if the mites are without an avian host, such as after affected birds abandon their nests, the mites will bite humans.3 Studies have discovered the presence of mammalian erythrocytes in the digestive tracts of one species of bird mite, Dermanyssus gallinae, suggesting that at least one form of avian mite may feed off humans but typically cannot reproduce without an avian blood meal.4 Individuals with gamasoidosis often are exposed to avian mites by owning birds as pets, rearing chickens or messenger pigeons, or having bird’s nests around their bedrooms or air conditioning units.1

Most people who develop avian mite dermatitis are the only affected member of the family to develop pruritus and papules since the reaction requires both bites and hypersensitivity to them; however, there are cases of nuclear families all reacting to avian mite bites.2,4 As in this case, hypersensitivity to avian mite bites causes exquisitely pruritic 2- to 5-mm papules, vesicles, or urticarial lesions that may be diagnosed as papular urticaria or misdiagnosed as scabies. Although bird mites may carry bacteria such as Salmonella, Spirochaete, Rickettsia, and Pasteurella, they have not demonstrated an ability to pass these on to human vectors.5,6

Bird mites will spend most of their lives on avian hosts but can spread to humans through direct contact or through air.7 Mites can go through floors, walls, ceilings, or most commonly through ventilation or air conditioning units. Increasing urbanization, especially in warmer climates where avian mites thrive, has increased the prevalence of gamasoidosis.1

Avian mite dermatitis commonly can be mistaken for scabies, but the mites can be seen with the naked eye and cannot form burrows, unlike scabies.4,8 Avian mites usually are not found on human skin since they leave the host after feeding and move with surprising speed.8 Pediculosis corporis (body lice) results from an infestation of Pediculus humanus corporis. At 2- to 4-mm long, this louse is much larger than a bird mite. Body lice rarely are found on the skin but rather live and lay eggs on clothing, particularly along the seams. The body louse has an elongated body with 3 segments and short antennae. Pthirus pubis (pubic lice) measure 1.5 to 2.0 mm in adulthood and have wider, more crablike bodies compared to body or hair lice or avian mites. Lice, being insects, have 6 legs as opposed to mites, being arachnids, having 8 legs. Cheyletiella are 0.5-mm long, nonburrowing mites commonly found on cats, dogs, and rabbits. Cheyletiella blakei affects cats. They look somewhat similar to bird mites but have hooklike palps extending from their heads instead of antennae.

Antihistamines and topical corticosteroids may reduce discomfort from avian bites but are not curative.2,9 The most efficient way to treat gamasoidosis is to remove any affected birds or nearby bird’s nests, as the mites cannot survive more than a few weeks to months without feeding on an avian host.8 It also may be necessary to fumigate infested rooms.10

The diagnosis of avian mite dermatitis often is missed to the frustration of the patient and clinician alike. Becoming familiar with this bite reaction will help clinicians diagnose this dermatologic conundrum.

- Wambier CG, de Farias Wambier SP. Gamasoidosis illustrated— from the nest to dermoscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:926-927. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962012000600021

- Collgros H, Iglesias-Sancho M, Aldunce MJ, et al. Dermanyssus gallinae (chicken mite): an underdiagnosed environmental infestation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:374-377.

- Akdemir C, Gülcan E, Tanritanir P. Case report: Dermanyssus gallinae in a patient with pruritus and skin lesions. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2009;33:242-244.

- Williams RW. An infestation of a human habitation by Dermanyssus gallinae (de Geer, 1778)(Acarina: Dermanyssidae) in New York resulting in sanguisugent attacks upon the occupants. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1958;7:627-629.

- Walker A. The Arthropods of Humans and Domestic Animals. A Guide to Preliminary Identification. Chapman and Hall; 1994.

- Vaiente MC, Chauve C, Zenner L. Experimental infection of Salmonella enteritidis by the poultry red mite, Dermanyssus gallinae. Vet Parasitol. 2007;146:329-336.

- Regan AM, Metersky ML, Craven DE. Nosocomial dermatitis and pruritus caused by pigeon mite infestation. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:2185-2187.

- Orton DI, Warren LJ, Wilkinson JD. Avian mite dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:129-131.

- Bassini-Silva R, de Castro Jacinavicius F, Akashi Hernandes F, et al. Dermatitis in humans caused by Ornithonyssus bursa (Berlese 1888) (Mesostigmata: Macronyssidae) and new records from Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2019;28:134-139.

- Watson CR. Human infestation with bird mites in Wollongong. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2003;27:259-261.

The Diagnosis: Gamasoidosis

An entomologist confirmed the specimen as an avian mite in either the Dermanyssus or Ornithonyssus genera (quiz image [bottom]). The patient was asked whether any bird had nested around her bedroom, and she affirmed that a woodpecker had nested outside her bedroom closet that spring. She subsequently discovered it had burrowed a hole into her closet wall. She and her husband removed the nest, and within 4 weeks, the eruption permanently cleared.

Gamasoidosis, or avian mite dermatitis, often is an overlooked, difficult-to-make diagnosis that is increasing in prevalence.1 Bird mites are ectoparasitic arthropods that are 0.3 to 1 mm in length. They have egg-shaped bodies with 4 pairs of legs; they are a translucent brown color before feeding and red after feeding.2 Although most avian mites cannot subsist off human blood, if the mites are without an avian host, such as after affected birds abandon their nests, the mites will bite humans.3 Studies have discovered the presence of mammalian erythrocytes in the digestive tracts of one species of bird mite, Dermanyssus gallinae, suggesting that at least one form of avian mite may feed off humans but typically cannot reproduce without an avian blood meal.4 Individuals with gamasoidosis often are exposed to avian mites by owning birds as pets, rearing chickens or messenger pigeons, or having bird’s nests around their bedrooms or air conditioning units.1

Most people who develop avian mite dermatitis are the only affected member of the family to develop pruritus and papules since the reaction requires both bites and hypersensitivity to them; however, there are cases of nuclear families all reacting to avian mite bites.2,4 As in this case, hypersensitivity to avian mite bites causes exquisitely pruritic 2- to 5-mm papules, vesicles, or urticarial lesions that may be diagnosed as papular urticaria or misdiagnosed as scabies. Although bird mites may carry bacteria such as Salmonella, Spirochaete, Rickettsia, and Pasteurella, they have not demonstrated an ability to pass these on to human vectors.5,6

Bird mites will spend most of their lives on avian hosts but can spread to humans through direct contact or through air.7 Mites can go through floors, walls, ceilings, or most commonly through ventilation or air conditioning units. Increasing urbanization, especially in warmer climates where avian mites thrive, has increased the prevalence of gamasoidosis.1

Avian mite dermatitis commonly can be mistaken for scabies, but the mites can be seen with the naked eye and cannot form burrows, unlike scabies.4,8 Avian mites usually are not found on human skin since they leave the host after feeding and move with surprising speed.8 Pediculosis corporis (body lice) results from an infestation of Pediculus humanus corporis. At 2- to 4-mm long, this louse is much larger than a bird mite. Body lice rarely are found on the skin but rather live and lay eggs on clothing, particularly along the seams. The body louse has an elongated body with 3 segments and short antennae. Pthirus pubis (pubic lice) measure 1.5 to 2.0 mm in adulthood and have wider, more crablike bodies compared to body or hair lice or avian mites. Lice, being insects, have 6 legs as opposed to mites, being arachnids, having 8 legs. Cheyletiella are 0.5-mm long, nonburrowing mites commonly found on cats, dogs, and rabbits. Cheyletiella blakei affects cats. They look somewhat similar to bird mites but have hooklike palps extending from their heads instead of antennae.

Antihistamines and topical corticosteroids may reduce discomfort from avian bites but are not curative.2,9 The most efficient way to treat gamasoidosis is to remove any affected birds or nearby bird’s nests, as the mites cannot survive more than a few weeks to months without feeding on an avian host.8 It also may be necessary to fumigate infested rooms.10

The diagnosis of avian mite dermatitis often is missed to the frustration of the patient and clinician alike. Becoming familiar with this bite reaction will help clinicians diagnose this dermatologic conundrum.

The Diagnosis: Gamasoidosis

An entomologist confirmed the specimen as an avian mite in either the Dermanyssus or Ornithonyssus genera (quiz image [bottom]). The patient was asked whether any bird had nested around her bedroom, and she affirmed that a woodpecker had nested outside her bedroom closet that spring. She subsequently discovered it had burrowed a hole into her closet wall. She and her husband removed the nest, and within 4 weeks, the eruption permanently cleared.

Gamasoidosis, or avian mite dermatitis, often is an overlooked, difficult-to-make diagnosis that is increasing in prevalence.1 Bird mites are ectoparasitic arthropods that are 0.3 to 1 mm in length. They have egg-shaped bodies with 4 pairs of legs; they are a translucent brown color before feeding and red after feeding.2 Although most avian mites cannot subsist off human blood, if the mites are without an avian host, such as after affected birds abandon their nests, the mites will bite humans.3 Studies have discovered the presence of mammalian erythrocytes in the digestive tracts of one species of bird mite, Dermanyssus gallinae, suggesting that at least one form of avian mite may feed off humans but typically cannot reproduce without an avian blood meal.4 Individuals with gamasoidosis often are exposed to avian mites by owning birds as pets, rearing chickens or messenger pigeons, or having bird’s nests around their bedrooms or air conditioning units.1

Most people who develop avian mite dermatitis are the only affected member of the family to develop pruritus and papules since the reaction requires both bites and hypersensitivity to them; however, there are cases of nuclear families all reacting to avian mite bites.2,4 As in this case, hypersensitivity to avian mite bites causes exquisitely pruritic 2- to 5-mm papules, vesicles, or urticarial lesions that may be diagnosed as papular urticaria or misdiagnosed as scabies. Although bird mites may carry bacteria such as Salmonella, Spirochaete, Rickettsia, and Pasteurella, they have not demonstrated an ability to pass these on to human vectors.5,6

Bird mites will spend most of their lives on avian hosts but can spread to humans through direct contact or through air.7 Mites can go through floors, walls, ceilings, or most commonly through ventilation or air conditioning units. Increasing urbanization, especially in warmer climates where avian mites thrive, has increased the prevalence of gamasoidosis.1

Avian mite dermatitis commonly can be mistaken for scabies, but the mites can be seen with the naked eye and cannot form burrows, unlike scabies.4,8 Avian mites usually are not found on human skin since they leave the host after feeding and move with surprising speed.8 Pediculosis corporis (body lice) results from an infestation of Pediculus humanus corporis. At 2- to 4-mm long, this louse is much larger than a bird mite. Body lice rarely are found on the skin but rather live and lay eggs on clothing, particularly along the seams. The body louse has an elongated body with 3 segments and short antennae. Pthirus pubis (pubic lice) measure 1.5 to 2.0 mm in adulthood and have wider, more crablike bodies compared to body or hair lice or avian mites. Lice, being insects, have 6 legs as opposed to mites, being arachnids, having 8 legs. Cheyletiella are 0.5-mm long, nonburrowing mites commonly found on cats, dogs, and rabbits. Cheyletiella blakei affects cats. They look somewhat similar to bird mites but have hooklike palps extending from their heads instead of antennae.

Antihistamines and topical corticosteroids may reduce discomfort from avian bites but are not curative.2,9 The most efficient way to treat gamasoidosis is to remove any affected birds or nearby bird’s nests, as the mites cannot survive more than a few weeks to months without feeding on an avian host.8 It also may be necessary to fumigate infested rooms.10

The diagnosis of avian mite dermatitis often is missed to the frustration of the patient and clinician alike. Becoming familiar with this bite reaction will help clinicians diagnose this dermatologic conundrum.

- Wambier CG, de Farias Wambier SP. Gamasoidosis illustrated— from the nest to dermoscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:926-927. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962012000600021

- Collgros H, Iglesias-Sancho M, Aldunce MJ, et al. Dermanyssus gallinae (chicken mite): an underdiagnosed environmental infestation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:374-377.

- Akdemir C, Gülcan E, Tanritanir P. Case report: Dermanyssus gallinae in a patient with pruritus and skin lesions. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2009;33:242-244.

- Williams RW. An infestation of a human habitation by Dermanyssus gallinae (de Geer, 1778)(Acarina: Dermanyssidae) in New York resulting in sanguisugent attacks upon the occupants. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1958;7:627-629.

- Walker A. The Arthropods of Humans and Domestic Animals. A Guide to Preliminary Identification. Chapman and Hall; 1994.

- Vaiente MC, Chauve C, Zenner L. Experimental infection of Salmonella enteritidis by the poultry red mite, Dermanyssus gallinae. Vet Parasitol. 2007;146:329-336.

- Regan AM, Metersky ML, Craven DE. Nosocomial dermatitis and pruritus caused by pigeon mite infestation. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:2185-2187.

- Orton DI, Warren LJ, Wilkinson JD. Avian mite dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:129-131.

- Bassini-Silva R, de Castro Jacinavicius F, Akashi Hernandes F, et al. Dermatitis in humans caused by Ornithonyssus bursa (Berlese 1888) (Mesostigmata: Macronyssidae) and new records from Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2019;28:134-139.

- Watson CR. Human infestation with bird mites in Wollongong. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2003;27:259-261.

- Wambier CG, de Farias Wambier SP. Gamasoidosis illustrated— from the nest to dermoscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:926-927. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962012000600021

- Collgros H, Iglesias-Sancho M, Aldunce MJ, et al. Dermanyssus gallinae (chicken mite): an underdiagnosed environmental infestation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:374-377.

- Akdemir C, Gülcan E, Tanritanir P. Case report: Dermanyssus gallinae in a patient with pruritus and skin lesions. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2009;33:242-244.

- Williams RW. An infestation of a human habitation by Dermanyssus gallinae (de Geer, 1778)(Acarina: Dermanyssidae) in New York resulting in sanguisugent attacks upon the occupants. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1958;7:627-629.

- Walker A. The Arthropods of Humans and Domestic Animals. A Guide to Preliminary Identification. Chapman and Hall; 1994.

- Vaiente MC, Chauve C, Zenner L. Experimental infection of Salmonella enteritidis by the poultry red mite, Dermanyssus gallinae. Vet Parasitol. 2007;146:329-336.

- Regan AM, Metersky ML, Craven DE. Nosocomial dermatitis and pruritus caused by pigeon mite infestation. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:2185-2187.

- Orton DI, Warren LJ, Wilkinson JD. Avian mite dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:129-131.

- Bassini-Silva R, de Castro Jacinavicius F, Akashi Hernandes F, et al. Dermatitis in humans caused by Ornithonyssus bursa (Berlese 1888) (Mesostigmata: Macronyssidae) and new records from Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2019;28:134-139.

- Watson CR. Human infestation with bird mites in Wollongong. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2003;27:259-261.

A 69-year-old woman presented in early summer in southeastern Michigan with several itchy bumps (top) of 4 to 5 weeks’ duration that erupted and remitted over the trunk, extremities, and face. She had taken no new medications. She had an asymptomatic cat and no exposure to anyone else who had been itching. Physical examination revealed approximately a dozen 2- to 5-mm edematous papules on the trunk, arms, shins, thighs, and left cheek, as well as one 3-mm vesicle on the forearm. No burrows could be identified on physical examination. Lesions treated with betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% improved, but new lesions continued to arise. An exterminator was contacted but found no signs of bedbugs or other infestations. Later, the patient reported seeing 3 tiny black dots crawl across the screen of her cell phone as she read in bed. She was able to capture them on tape and bring them to her appointment. The specimens were approximately 1 mm in length (bottom).

What’s in a White Coat? The Changing Trends in Physician Attire and What it Means for Dermatology

The White Coat Ceremony is an enduring memory from my medical school years. Amidst the tumult of memories of seemingly endless sleepless nights spent in libraries and cramming for clerkship examinations between surgical cases, I recall a sunny spring day in 2016 where I gathered with my classmates, family, and friends in the medical school campus courtyard. There were several short, mostly forgotten speeches after which proud fathers and mothers, partners, or siblings slipped the all-important white coat onto the shoulders of the physicians-to-be. At that moment, I felt the weight of tradition centuries in the making resting on my shoulders. Of course, the pomp of the ceremony might have felt a tad overblown had I known that the whole thing had fewer years under its belt than the movie Die Hard.

That’s right, the first White Coat Ceremony was held 5 years after the release of that Bruce Willis classic. Dr. Arnold Gold, a pediatric neurologist on faculty at Columbia University, conceived the ceremony in 1993, and it spread rapidly to medical schools—and later nursing schools—across the United States.1 Although the values highlighted by the White Coat Ceremony—humanism and compassion in medicine—are timeless, the ceremony itself is a more modern undertaking. What, then, of the white coat itself? Is it the timeless symbol of doctoring—of medicine—that we all presume it to be? Or is it a symbol of modern marketing, just a trend that caught on? And is it encountering its twilight—as trends often do—in the face of changing fashion and, more fundamentally, in changes to who our physicians are and to their roles in our society?

The Cleanliness of the White Coat

Until the end of the 19th century, physicians in the Western world most frequently dressed in black formal wear. The rationale behind this attire seems to have been twofold. First, society as a whole perceived the physician’s work as a serious and formal matter, and any medical encounter had to reflect the gravity of the occasion. Additionally, physicians’ visits often were a portent of impending demise, as physicians in the era prior to antibiotics and antisepsis frequently had little to offer their patients outside of—at best—anecdotal treatments and—at worst—sheer quackery.2 Black may have seemed a respectful choice for patients who likely faced dire outcomes regardless of the treatment afforded.3

With the turn of the century came a new understanding of the concepts of antisepsis and disease transmission. While Joseph Lister first published on the use of antisepsis in 1867, his practices did not become commonplace until the early 1900s.4 Around the same time came the Flexner report,5 the publication of William Osler’s Principles and Practice of Medicine,6 and the establishment of the modern medical residency, all of which contributed to the shift from the patient’s own bedside and to the hospital as the house of medicine, with cleanliness and antisepsis as part of its core principles.7 The white coat arose as a symbol of purity and freedom from disease. Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, it has remained the predominant symbol of cleanliness and professionalism for the medical practitioner.

Patient Preference of Physician Attire

Although the white coat may serve as a professional symbol and is well respected medicine, it also plays an important role in the layperson’s perception of their health care providers.8 There is little denying that patients prefer their physicians, almost uniformly, to wear a white coat. A systematic review of physician attire that included 30 studies mainly from North America, Europe, and the United Kingdom found that patient preference for formal attire and white coats is near universal.9 Patients routinely rate physicians wearing a white coat as more intelligent and trustworthy and feel more confident in the care they will receive.10-13 They also freely admit that a physician’s appearance influences their satisfaction with their care.14 The recent adoption of the fleece, or softshell, jacket has not yet pervaded patients’ perceptions of what is considered appropriate physician attire. A 500-respondent survey found that patients were more likely to rate a model wearing a white coat as more professional and experienced compared to the same model wearing a fleece or softshell jacket or other formal attire sans white coat.15

Closer examination of the same data, however, reveals results reproduced with startling consistency across several studies, which suggest those of us adopting other attire need not dig those white coats out of the closet just yet. First, while many studies point to patient preference for white coats, this preference is uniformly strongest in older patients, beginning around age 40 years and becoming an entrenched preference in those older than 65 years.9,14,16-18 On the other hand, younger patient populations display little to no such preference, and some studies indicate that younger patients actually prefer scrubs over formal attire in specific settings such as surgical offices, procedural spaces, or the emergency department.12,14,19 This suggests that bias in favor of traditional physician garb may be more linked to age demographics and may continue to shift as the overall population ages. Additionally, although patients might profess a strong preference for physician attire in theory, it often does not translate into any impact on the patient’s perception of the physician following a clinic visit. The large systematic review on the topic noted that only 25% of studies that surveyed patients about a clinical visit following the encounter reported that physician attire influenced their satisfaction with that visit, suggesting that attire may be less likely to influence patients in the real-world context of receiving care.9 In fact, a prospective study of patient perception of medical staff and interactions found that staff style of dress not only had no bearing on the perception of staff or visit satisfaction but that patients often failed to even accurately recall physician attire when surveyed.20 Another survey study echoed these conclusions, finding that physician attire had no effect on the perception of a proposed treatment plan.21

What do we know about patient perception of physician attire in the dermatology setting specifically, where visits can be unique in their tendency to transition from medical to procedural in the span of a 15-minute encounter depending on the patient’s chief concern? A survey study of dermatology patients at the general, surgical, and wound care dermatology clinics of an academic medical center (Miami, Florida) found that professional attire with a white coat was strongly preferred across a litany of scenarios assessing many aspects of dermatologic care.21 Similarly, a study of patients visiting a single institution’s dermatology and pediatric dermatology clinics surveyed patients and parents regarding attire prior to an appointment and specifically asked if a white coat should be worn.13 Fifty-four percent of the adult patients (n=176) surveyed professed a preference for physicians in white coats, with a stronger preference for white coats reported by those 50 years and older (55%; n=113). Parents or guardians presenting to the pediatric dermatology clinic, on the other hand, favored less formal attire.13 A recent, real-world study performed at an outpatient dermatology clinic examined the influence of changing physician attire on a patient’s perceptions of care received during clinic encounters. They found no substantial difference in patient satisfaction scores before and following the adoption of a new clinic uniform that transitioned from formal attire to fitted scrubs.22

Racial and Gender Bias Affecting Attire Preference

With any study of preference, there is the underlying concern over respondent bias. Many of the studies discussed here have found secondarily that a patient’s implicit bias does not end at the clothes their physician is wearing. The survey study of dermatology patients from the academic medical center in Miami, Florida, found that patients preferred that Black physicians of either sex be garbed in professional attire at all times but generally were more accepting of White physicians in less formal attire.21 Adamson et al23 published a response to the study’s findings urging dermatologists to recognize that a physician’s race and gender influence patients’ perceptions in much the same way that physician attire seems to and encouraged the development of a more diverse dermatologic workforce to help combat this prejudice. The issue of bias is not limited to the specialty of dermatology; the recent survey study by Xun et al15 found that respondents consistently rated female models garbed in physician attire as less professional than male model counterparts. Additionally, female models wearing white coats were mistakenly identified as medical technicians, physician assistants, or nurses with substantially more frequency than males, despite being clothed in the traditional physician garb. Several other publications on the subject have uncovered implicit bias, though it is rarely, if ever, the principle focus of the study.10,24,25 As is unfortunately true in many professions, female physicians and physicians from ethnic minorities face barriers to being perceived as fully competent physicians.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Finally, of course, there is the ever-present question of the effect of the pandemic. Although the exact role of the white coat as a fomite for infection—and especially for the spread of viral illness—remains controversial, the perception nonetheless has helped catalyze the movement to alternatives such as short-sleeved white coats, technical jackets, and more recently, fitted scrubs.26-29 As with much in this realm, facts seem less important than perceptions; Zahrina et al30 found that when patients were presented with information regarding the risk for microbial contamination associated with white coats, preference for physicians in professional garb plummeted from 72% to only 22%. To date no articles have examined patient perceptions of the white coat in the context of microbial transmission in the age of COVID-19, but future articles on this topic are likely and may serve to further the demise of the white coat.

Final Thoughts

From my vantage point, it seems the white coat will be claimed by the outgoing tide. During this most recent residency interview season, I do not recall a single medical student wearing a short white coat. The closest I came was a quick glimpse of a crumpled white jacket slung over an arm or stuffed in a shoulder bag. Rotating interns and residents from other services on rotation in our department present in softshell or fleece jackets. Fitted scrubs in the newest trendy colors speckle a previously all-white canvas. I, for one, have not donned my own white coat in at least a year, and perhaps it is all for the best. Physician attire is one small aspect of the practice of medicine and likely bears little, if any, relation to the wearer’s qualifications. Our focus should be on building rapport with our patients, providing high-quality care, reducing the risk for nosocomial infection, and developing a health care system that is fair and equitable for patients and health care workers alike, not on who is wearing what. Perhaps the introduction of new physician attire is a small part of the disruption we need to help address persistent gender and racial biases in our field and help shepherd our patients and colleagues to a worldview that is more open and accepting of physicians of diverse backgrounds.

- White Coat Ceremony. Gold Foundation website. Accessed December 26, 2021. https://www.gold-foundation.org/programs/white-coat-ceremony/

- Shryock RH. The Development of Modern Medicine. University of Pennsylvania Press; 2017.

- Hochberg MS. The doctor’s white coat—an historical perspective. Virtual Mentor. 2007;9:310-314.

- Lister J. On the antiseptic principle in the practice of surgery. Lancet. 1867;90:353-356.

- Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910.

- Osler W. Principles and Practice of Medicine: Designed for the Use of Practitioners and Students of Medicine. D. Appleton & Company; 1892.

- Blumhagen DW. The doctor’s white coat: the image of the physician in modern America. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:111-116.

- Verghese BG, Kashinath SK, Jadhav N, et al. Physician attire: physicians’ perspectives on attire in a community hospital setting among non-surgical specialties. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2020;10:1-5.

- Petrilli CM, Mack M, Petrilli JJ, et al. Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature—targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open. 2015;5:E006678.

- Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW, et al. What to wear today? effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am J Med. 2005;118:1279-1286.

- Jennings JD, Ciaravino SG, Ramsey FV, et al. Physicians’ attire influences patients’ perceptions in the urban outpatient orthopaedic surgery setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1908-1918.

- Gherardi G, Cameron J, West A, et al. Are we dressed to impress? a descriptive survey assessing patients preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. Clin Med (Lond). 2009;9:519-524.

- Thomas MW, Burkhart CN, Lugo-Somolinos A, et al. Patients’ perceptions of physician attire in dermatology clinics. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:505-506.

- Petrilli CM, Saint S, Jennings JJ, et al. Understanding patient preference for physician attire: a cross-sectional observational study of 10 academic medical centres in the USA. BMJ Open. 2018;8:E021239.

- Xun H, Chen J, Sun AH, et al. Public perceptions of physician attire and professionalism in the US. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4:E2117779.

- Kamata K, Kuriyama A, Chopra V, et al. Patient preferences for physician attire: a multicenter study in Japan [published online February 11, 2020]. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:204-210.

- Budny AM, Rogers LC, Mandracchia VJ, et al. The physician’s attire and its influence on patient confidence. J Am Podiatr Assoc. 2006;96:132-138.

- Lill MM, Wilkinson TJ. Judging a book by its cover: descriptive survey of patients’ preferences for doctors’ appearance and mode of address. Br Med J. 2005;331:1524-1527.

- Hossler EW, Shipp D, Palmer M, et al. Impact of provider attire on patient satisfaction in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Cutis. 2018;102:127-129.

- Boon D, Wardrope J. What should doctors wear in the accident and emergency department? patients’ perception. J Accid Emerg Med. 1994;11:175-177.

- Fox JD, Prado G, Baquerizo Nole KL, et al. Patient preference in dermatologist attire in the medical, surgical, and wound care settings. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:913-919.

- Bray JK, Porter C, Feldman SR. The effect of physician appearance on patient perceptions of treatment plans. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327553611

- Adamson AS, Wright SW, Pandya AG. A missed opportunity to discuss racial and gender bias in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:110-111.

- Hartmans C, Heremans S, Lagrain M, et al. The doctor’s new clothes: professional or fashionable? Primary Health Care. 2013;3:135.

- Kurihara H, Maeno T, Maeno T. Importance of physicians’ attire: factors influencing the impression it makes on patients, a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13:2.

- Treakle AM, Thom KA, Furuno JP, et al. Bacterial contamination of health care workers’ white coats. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:101-105.

- Banu A, Anand M, Nagi N, et al. White coats as a vehicle for bacterial dissemination. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1381-1384.

- Haun N, Hooper-Lane C, Safdar N. Healthcare personnel attire and devices as fomites: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1367-1373.

- Tse G, Withey S, Yeo JM, et al. Bare below the elbows: was the target the white coat? J Hosp Infect. 2015;91:299-301.

- Zahrina AZ, Haymond P, Rosanna P, et al. Does the attire of a primary care physician affect patients’ perceptions and their levels of trust in the doctor? Malays Fam Physician. 2018;13:3-11.

The White Coat Ceremony is an enduring memory from my medical school years. Amidst the tumult of memories of seemingly endless sleepless nights spent in libraries and cramming for clerkship examinations between surgical cases, I recall a sunny spring day in 2016 where I gathered with my classmates, family, and friends in the medical school campus courtyard. There were several short, mostly forgotten speeches after which proud fathers and mothers, partners, or siblings slipped the all-important white coat onto the shoulders of the physicians-to-be. At that moment, I felt the weight of tradition centuries in the making resting on my shoulders. Of course, the pomp of the ceremony might have felt a tad overblown had I known that the whole thing had fewer years under its belt than the movie Die Hard.

That’s right, the first White Coat Ceremony was held 5 years after the release of that Bruce Willis classic. Dr. Arnold Gold, a pediatric neurologist on faculty at Columbia University, conceived the ceremony in 1993, and it spread rapidly to medical schools—and later nursing schools—across the United States.1 Although the values highlighted by the White Coat Ceremony—humanism and compassion in medicine—are timeless, the ceremony itself is a more modern undertaking. What, then, of the white coat itself? Is it the timeless symbol of doctoring—of medicine—that we all presume it to be? Or is it a symbol of modern marketing, just a trend that caught on? And is it encountering its twilight—as trends often do—in the face of changing fashion and, more fundamentally, in changes to who our physicians are and to their roles in our society?

The Cleanliness of the White Coat

Until the end of the 19th century, physicians in the Western world most frequently dressed in black formal wear. The rationale behind this attire seems to have been twofold. First, society as a whole perceived the physician’s work as a serious and formal matter, and any medical encounter had to reflect the gravity of the occasion. Additionally, physicians’ visits often were a portent of impending demise, as physicians in the era prior to antibiotics and antisepsis frequently had little to offer their patients outside of—at best—anecdotal treatments and—at worst—sheer quackery.2 Black may have seemed a respectful choice for patients who likely faced dire outcomes regardless of the treatment afforded.3

With the turn of the century came a new understanding of the concepts of antisepsis and disease transmission. While Joseph Lister first published on the use of antisepsis in 1867, his practices did not become commonplace until the early 1900s.4 Around the same time came the Flexner report,5 the publication of William Osler’s Principles and Practice of Medicine,6 and the establishment of the modern medical residency, all of which contributed to the shift from the patient’s own bedside and to the hospital as the house of medicine, with cleanliness and antisepsis as part of its core principles.7 The white coat arose as a symbol of purity and freedom from disease. Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, it has remained the predominant symbol of cleanliness and professionalism for the medical practitioner.

Patient Preference of Physician Attire

Although the white coat may serve as a professional symbol and is well respected medicine, it also plays an important role in the layperson’s perception of their health care providers.8 There is little denying that patients prefer their physicians, almost uniformly, to wear a white coat. A systematic review of physician attire that included 30 studies mainly from North America, Europe, and the United Kingdom found that patient preference for formal attire and white coats is near universal.9 Patients routinely rate physicians wearing a white coat as more intelligent and trustworthy and feel more confident in the care they will receive.10-13 They also freely admit that a physician’s appearance influences their satisfaction with their care.14 The recent adoption of the fleece, or softshell, jacket has not yet pervaded patients’ perceptions of what is considered appropriate physician attire. A 500-respondent survey found that patients were more likely to rate a model wearing a white coat as more professional and experienced compared to the same model wearing a fleece or softshell jacket or other formal attire sans white coat.15

Closer examination of the same data, however, reveals results reproduced with startling consistency across several studies, which suggest those of us adopting other attire need not dig those white coats out of the closet just yet. First, while many studies point to patient preference for white coats, this preference is uniformly strongest in older patients, beginning around age 40 years and becoming an entrenched preference in those older than 65 years.9,14,16-18 On the other hand, younger patient populations display little to no such preference, and some studies indicate that younger patients actually prefer scrubs over formal attire in specific settings such as surgical offices, procedural spaces, or the emergency department.12,14,19 This suggests that bias in favor of traditional physician garb may be more linked to age demographics and may continue to shift as the overall population ages. Additionally, although patients might profess a strong preference for physician attire in theory, it often does not translate into any impact on the patient’s perception of the physician following a clinic visit. The large systematic review on the topic noted that only 25% of studies that surveyed patients about a clinical visit following the encounter reported that physician attire influenced their satisfaction with that visit, suggesting that attire may be less likely to influence patients in the real-world context of receiving care.9 In fact, a prospective study of patient perception of medical staff and interactions found that staff style of dress not only had no bearing on the perception of staff or visit satisfaction but that patients often failed to even accurately recall physician attire when surveyed.20 Another survey study echoed these conclusions, finding that physician attire had no effect on the perception of a proposed treatment plan.21

What do we know about patient perception of physician attire in the dermatology setting specifically, where visits can be unique in their tendency to transition from medical to procedural in the span of a 15-minute encounter depending on the patient’s chief concern? A survey study of dermatology patients at the general, surgical, and wound care dermatology clinics of an academic medical center (Miami, Florida) found that professional attire with a white coat was strongly preferred across a litany of scenarios assessing many aspects of dermatologic care.21 Similarly, a study of patients visiting a single institution’s dermatology and pediatric dermatology clinics surveyed patients and parents regarding attire prior to an appointment and specifically asked if a white coat should be worn.13 Fifty-four percent of the adult patients (n=176) surveyed professed a preference for physicians in white coats, with a stronger preference for white coats reported by those 50 years and older (55%; n=113). Parents or guardians presenting to the pediatric dermatology clinic, on the other hand, favored less formal attire.13 A recent, real-world study performed at an outpatient dermatology clinic examined the influence of changing physician attire on a patient’s perceptions of care received during clinic encounters. They found no substantial difference in patient satisfaction scores before and following the adoption of a new clinic uniform that transitioned from formal attire to fitted scrubs.22

Racial and Gender Bias Affecting Attire Preference

With any study of preference, there is the underlying concern over respondent bias. Many of the studies discussed here have found secondarily that a patient’s implicit bias does not end at the clothes their physician is wearing. The survey study of dermatology patients from the academic medical center in Miami, Florida, found that patients preferred that Black physicians of either sex be garbed in professional attire at all times but generally were more accepting of White physicians in less formal attire.21 Adamson et al23 published a response to the study’s findings urging dermatologists to recognize that a physician’s race and gender influence patients’ perceptions in much the same way that physician attire seems to and encouraged the development of a more diverse dermatologic workforce to help combat this prejudice. The issue of bias is not limited to the specialty of dermatology; the recent survey study by Xun et al15 found that respondents consistently rated female models garbed in physician attire as less professional than male model counterparts. Additionally, female models wearing white coats were mistakenly identified as medical technicians, physician assistants, or nurses with substantially more frequency than males, despite being clothed in the traditional physician garb. Several other publications on the subject have uncovered implicit bias, though it is rarely, if ever, the principle focus of the study.10,24,25 As is unfortunately true in many professions, female physicians and physicians from ethnic minorities face barriers to being perceived as fully competent physicians.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Finally, of course, there is the ever-present question of the effect of the pandemic. Although the exact role of the white coat as a fomite for infection—and especially for the spread of viral illness—remains controversial, the perception nonetheless has helped catalyze the movement to alternatives such as short-sleeved white coats, technical jackets, and more recently, fitted scrubs.26-29 As with much in this realm, facts seem less important than perceptions; Zahrina et al30 found that when patients were presented with information regarding the risk for microbial contamination associated with white coats, preference for physicians in professional garb plummeted from 72% to only 22%. To date no articles have examined patient perceptions of the white coat in the context of microbial transmission in the age of COVID-19, but future articles on this topic are likely and may serve to further the demise of the white coat.

Final Thoughts

From my vantage point, it seems the white coat will be claimed by the outgoing tide. During this most recent residency interview season, I do not recall a single medical student wearing a short white coat. The closest I came was a quick glimpse of a crumpled white jacket slung over an arm or stuffed in a shoulder bag. Rotating interns and residents from other services on rotation in our department present in softshell or fleece jackets. Fitted scrubs in the newest trendy colors speckle a previously all-white canvas. I, for one, have not donned my own white coat in at least a year, and perhaps it is all for the best. Physician attire is one small aspect of the practice of medicine and likely bears little, if any, relation to the wearer’s qualifications. Our focus should be on building rapport with our patients, providing high-quality care, reducing the risk for nosocomial infection, and developing a health care system that is fair and equitable for patients and health care workers alike, not on who is wearing what. Perhaps the introduction of new physician attire is a small part of the disruption we need to help address persistent gender and racial biases in our field and help shepherd our patients and colleagues to a worldview that is more open and accepting of physicians of diverse backgrounds.

The White Coat Ceremony is an enduring memory from my medical school years. Amidst the tumult of memories of seemingly endless sleepless nights spent in libraries and cramming for clerkship examinations between surgical cases, I recall a sunny spring day in 2016 where I gathered with my classmates, family, and friends in the medical school campus courtyard. There were several short, mostly forgotten speeches after which proud fathers and mothers, partners, or siblings slipped the all-important white coat onto the shoulders of the physicians-to-be. At that moment, I felt the weight of tradition centuries in the making resting on my shoulders. Of course, the pomp of the ceremony might have felt a tad overblown had I known that the whole thing had fewer years under its belt than the movie Die Hard.

That’s right, the first White Coat Ceremony was held 5 years after the release of that Bruce Willis classic. Dr. Arnold Gold, a pediatric neurologist on faculty at Columbia University, conceived the ceremony in 1993, and it spread rapidly to medical schools—and later nursing schools—across the United States.1 Although the values highlighted by the White Coat Ceremony—humanism and compassion in medicine—are timeless, the ceremony itself is a more modern undertaking. What, then, of the white coat itself? Is it the timeless symbol of doctoring—of medicine—that we all presume it to be? Or is it a symbol of modern marketing, just a trend that caught on? And is it encountering its twilight—as trends often do—in the face of changing fashion and, more fundamentally, in changes to who our physicians are and to their roles in our society?

The Cleanliness of the White Coat

Until the end of the 19th century, physicians in the Western world most frequently dressed in black formal wear. The rationale behind this attire seems to have been twofold. First, society as a whole perceived the physician’s work as a serious and formal matter, and any medical encounter had to reflect the gravity of the occasion. Additionally, physicians’ visits often were a portent of impending demise, as physicians in the era prior to antibiotics and antisepsis frequently had little to offer their patients outside of—at best—anecdotal treatments and—at worst—sheer quackery.2 Black may have seemed a respectful choice for patients who likely faced dire outcomes regardless of the treatment afforded.3

With the turn of the century came a new understanding of the concepts of antisepsis and disease transmission. While Joseph Lister first published on the use of antisepsis in 1867, his practices did not become commonplace until the early 1900s.4 Around the same time came the Flexner report,5 the publication of William Osler’s Principles and Practice of Medicine,6 and the establishment of the modern medical residency, all of which contributed to the shift from the patient’s own bedside and to the hospital as the house of medicine, with cleanliness and antisepsis as part of its core principles.7 The white coat arose as a symbol of purity and freedom from disease. Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, it has remained the predominant symbol of cleanliness and professionalism for the medical practitioner.

Patient Preference of Physician Attire

Although the white coat may serve as a professional symbol and is well respected medicine, it also plays an important role in the layperson’s perception of their health care providers.8 There is little denying that patients prefer their physicians, almost uniformly, to wear a white coat. A systematic review of physician attire that included 30 studies mainly from North America, Europe, and the United Kingdom found that patient preference for formal attire and white coats is near universal.9 Patients routinely rate physicians wearing a white coat as more intelligent and trustworthy and feel more confident in the care they will receive.10-13 They also freely admit that a physician’s appearance influences their satisfaction with their care.14 The recent adoption of the fleece, or softshell, jacket has not yet pervaded patients’ perceptions of what is considered appropriate physician attire. A 500-respondent survey found that patients were more likely to rate a model wearing a white coat as more professional and experienced compared to the same model wearing a fleece or softshell jacket or other formal attire sans white coat.15

Closer examination of the same data, however, reveals results reproduced with startling consistency across several studies, which suggest those of us adopting other attire need not dig those white coats out of the closet just yet. First, while many studies point to patient preference for white coats, this preference is uniformly strongest in older patients, beginning around age 40 years and becoming an entrenched preference in those older than 65 years.9,14,16-18 On the other hand, younger patient populations display little to no such preference, and some studies indicate that younger patients actually prefer scrubs over formal attire in specific settings such as surgical offices, procedural spaces, or the emergency department.12,14,19 This suggests that bias in favor of traditional physician garb may be more linked to age demographics and may continue to shift as the overall population ages. Additionally, although patients might profess a strong preference for physician attire in theory, it often does not translate into any impact on the patient’s perception of the physician following a clinic visit. The large systematic review on the topic noted that only 25% of studies that surveyed patients about a clinical visit following the encounter reported that physician attire influenced their satisfaction with that visit, suggesting that attire may be less likely to influence patients in the real-world context of receiving care.9 In fact, a prospective study of patient perception of medical staff and interactions found that staff style of dress not only had no bearing on the perception of staff or visit satisfaction but that patients often failed to even accurately recall physician attire when surveyed.20 Another survey study echoed these conclusions, finding that physician attire had no effect on the perception of a proposed treatment plan.21

What do we know about patient perception of physician attire in the dermatology setting specifically, where visits can be unique in their tendency to transition from medical to procedural in the span of a 15-minute encounter depending on the patient’s chief concern? A survey study of dermatology patients at the general, surgical, and wound care dermatology clinics of an academic medical center (Miami, Florida) found that professional attire with a white coat was strongly preferred across a litany of scenarios assessing many aspects of dermatologic care.21 Similarly, a study of patients visiting a single institution’s dermatology and pediatric dermatology clinics surveyed patients and parents regarding attire prior to an appointment and specifically asked if a white coat should be worn.13 Fifty-four percent of the adult patients (n=176) surveyed professed a preference for physicians in white coats, with a stronger preference for white coats reported by those 50 years and older (55%; n=113). Parents or guardians presenting to the pediatric dermatology clinic, on the other hand, favored less formal attire.13 A recent, real-world study performed at an outpatient dermatology clinic examined the influence of changing physician attire on a patient’s perceptions of care received during clinic encounters. They found no substantial difference in patient satisfaction scores before and following the adoption of a new clinic uniform that transitioned from formal attire to fitted scrubs.22

Racial and Gender Bias Affecting Attire Preference

With any study of preference, there is the underlying concern over respondent bias. Many of the studies discussed here have found secondarily that a patient’s implicit bias does not end at the clothes their physician is wearing. The survey study of dermatology patients from the academic medical center in Miami, Florida, found that patients preferred that Black physicians of either sex be garbed in professional attire at all times but generally were more accepting of White physicians in less formal attire.21 Adamson et al23 published a response to the study’s findings urging dermatologists to recognize that a physician’s race and gender influence patients’ perceptions in much the same way that physician attire seems to and encouraged the development of a more diverse dermatologic workforce to help combat this prejudice. The issue of bias is not limited to the specialty of dermatology; the recent survey study by Xun et al15 found that respondents consistently rated female models garbed in physician attire as less professional than male model counterparts. Additionally, female models wearing white coats were mistakenly identified as medical technicians, physician assistants, or nurses with substantially more frequency than males, despite being clothed in the traditional physician garb. Several other publications on the subject have uncovered implicit bias, though it is rarely, if ever, the principle focus of the study.10,24,25 As is unfortunately true in many professions, female physicians and physicians from ethnic minorities face barriers to being perceived as fully competent physicians.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Finally, of course, there is the ever-present question of the effect of the pandemic. Although the exact role of the white coat as a fomite for infection—and especially for the spread of viral illness—remains controversial, the perception nonetheless has helped catalyze the movement to alternatives such as short-sleeved white coats, technical jackets, and more recently, fitted scrubs.26-29 As with much in this realm, facts seem less important than perceptions; Zahrina et al30 found that when patients were presented with information regarding the risk for microbial contamination associated with white coats, preference for physicians in professional garb plummeted from 72% to only 22%. To date no articles have examined patient perceptions of the white coat in the context of microbial transmission in the age of COVID-19, but future articles on this topic are likely and may serve to further the demise of the white coat.

Final Thoughts

From my vantage point, it seems the white coat will be claimed by the outgoing tide. During this most recent residency interview season, I do not recall a single medical student wearing a short white coat. The closest I came was a quick glimpse of a crumpled white jacket slung over an arm or stuffed in a shoulder bag. Rotating interns and residents from other services on rotation in our department present in softshell or fleece jackets. Fitted scrubs in the newest trendy colors speckle a previously all-white canvas. I, for one, have not donned my own white coat in at least a year, and perhaps it is all for the best. Physician attire is one small aspect of the practice of medicine and likely bears little, if any, relation to the wearer’s qualifications. Our focus should be on building rapport with our patients, providing high-quality care, reducing the risk for nosocomial infection, and developing a health care system that is fair and equitable for patients and health care workers alike, not on who is wearing what. Perhaps the introduction of new physician attire is a small part of the disruption we need to help address persistent gender and racial biases in our field and help shepherd our patients and colleagues to a worldview that is more open and accepting of physicians of diverse backgrounds.

- White Coat Ceremony. Gold Foundation website. Accessed December 26, 2021. https://www.gold-foundation.org/programs/white-coat-ceremony/

- Shryock RH. The Development of Modern Medicine. University of Pennsylvania Press; 2017.

- Hochberg MS. The doctor’s white coat—an historical perspective. Virtual Mentor. 2007;9:310-314.

- Lister J. On the antiseptic principle in the practice of surgery. Lancet. 1867;90:353-356.

- Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910.

- Osler W. Principles and Practice of Medicine: Designed for the Use of Practitioners and Students of Medicine. D. Appleton & Company; 1892.

- Blumhagen DW. The doctor’s white coat: the image of the physician in modern America. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:111-116.

- Verghese BG, Kashinath SK, Jadhav N, et al. Physician attire: physicians’ perspectives on attire in a community hospital setting among non-surgical specialties. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2020;10:1-5.

- Petrilli CM, Mack M, Petrilli JJ, et al. Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature—targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open. 2015;5:E006678.

- Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW, et al. What to wear today? effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am J Med. 2005;118:1279-1286.

- Jennings JD, Ciaravino SG, Ramsey FV, et al. Physicians’ attire influences patients’ perceptions in the urban outpatient orthopaedic surgery setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1908-1918.

- Gherardi G, Cameron J, West A, et al. Are we dressed to impress? a descriptive survey assessing patients preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. Clin Med (Lond). 2009;9:519-524.

- Thomas MW, Burkhart CN, Lugo-Somolinos A, et al. Patients’ perceptions of physician attire in dermatology clinics. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:505-506.

- Petrilli CM, Saint S, Jennings JJ, et al. Understanding patient preference for physician attire: a cross-sectional observational study of 10 academic medical centres in the USA. BMJ Open. 2018;8:E021239.

- Xun H, Chen J, Sun AH, et al. Public perceptions of physician attire and professionalism in the US. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4:E2117779.

- Kamata K, Kuriyama A, Chopra V, et al. Patient preferences for physician attire: a multicenter study in Japan [published online February 11, 2020]. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:204-210.

- Budny AM, Rogers LC, Mandracchia VJ, et al. The physician’s attire and its influence on patient confidence. J Am Podiatr Assoc. 2006;96:132-138.

- Lill MM, Wilkinson TJ. Judging a book by its cover: descriptive survey of patients’ preferences for doctors’ appearance and mode of address. Br Med J. 2005;331:1524-1527.

- Hossler EW, Shipp D, Palmer M, et al. Impact of provider attire on patient satisfaction in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Cutis. 2018;102:127-129.

- Boon D, Wardrope J. What should doctors wear in the accident and emergency department? patients’ perception. J Accid Emerg Med. 1994;11:175-177.

- Fox JD, Prado G, Baquerizo Nole KL, et al. Patient preference in dermatologist attire in the medical, surgical, and wound care settings. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:913-919.

- Bray JK, Porter C, Feldman SR. The effect of physician appearance on patient perceptions of treatment plans. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327553611

- Adamson AS, Wright SW, Pandya AG. A missed opportunity to discuss racial and gender bias in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:110-111.

- Hartmans C, Heremans S, Lagrain M, et al. The doctor’s new clothes: professional or fashionable? Primary Health Care. 2013;3:135.

- Kurihara H, Maeno T, Maeno T. Importance of physicians’ attire: factors influencing the impression it makes on patients, a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2014;13:2.

- Treakle AM, Thom KA, Furuno JP, et al. Bacterial contamination of health care workers’ white coats. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:101-105.

- Banu A, Anand M, Nagi N, et al. White coats as a vehicle for bacterial dissemination. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1381-1384.

- Haun N, Hooper-Lane C, Safdar N. Healthcare personnel attire and devices as fomites: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1367-1373.

- Tse G, Withey S, Yeo JM, et al. Bare below the elbows: was the target the white coat? J Hosp Infect. 2015;91:299-301.

- Zahrina AZ, Haymond P, Rosanna P, et al. Does the attire of a primary care physician affect patients’ perceptions and their levels of trust in the doctor? Malays Fam Physician. 2018;13:3-11.

- White Coat Ceremony. Gold Foundation website. Accessed December 26, 2021. https://www.gold-foundation.org/programs/white-coat-ceremony/

- Shryock RH. The Development of Modern Medicine. University of Pennsylvania Press; 2017.

- Hochberg MS. The doctor’s white coat—an historical perspective. Virtual Mentor. 2007;9:310-314.

- Lister J. On the antiseptic principle in the practice of surgery. Lancet. 1867;90:353-356.

- Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910.

- Osler W. Principles and Practice of Medicine: Designed for the Use of Practitioners and Students of Medicine. D. Appleton & Company; 1892.

- Blumhagen DW. The doctor’s white coat: the image of the physician in modern America. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:111-116.

- Verghese BG, Kashinath SK, Jadhav N, et al. Physician attire: physicians’ perspectives on attire in a community hospital setting among non-surgical specialties. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2020;10:1-5.

- Petrilli CM, Mack M, Petrilli JJ, et al. Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature—targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open. 2015;5:E006678.

- Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW, et al. What to wear today? effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am J Med. 2005;118:1279-1286.

- Jennings JD, Ciaravino SG, Ramsey FV, et al. Physicians’ attire influences patients’ perceptions in the urban outpatient orthopaedic surgery setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1908-1918.

- Gherardi G, Cameron J, West A, et al. Are we dressed to impress? a descriptive survey assessing patients preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. Clin Med (Lond). 2009;9:519-524.

- Thomas MW, Burkhart CN, Lugo-Somolinos A, et al. Patients’ perceptions of physician attire in dermatology clinics. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:505-506.

- Petrilli CM, Saint S, Jennings JJ, et al. Understanding patient preference for physician attire: a cross-sectional observational study of 10 academic medical centres in the USA. BMJ Open. 2018;8:E021239.

- Xun H, Chen J, Sun AH, et al. Public perceptions of physician attire and professionalism in the US. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4:E2117779.

- Kamata K, Kuriyama A, Chopra V, et al. Patient preferences for physician attire: a multicenter study in Japan [published online February 11, 2020]. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:204-210.

- Budny AM, Rogers LC, Mandracchia VJ, et al. The physician’s attire and its influence on patient confidence. J Am Podiatr Assoc. 2006;96:132-138.