User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Sporotrichoid Pattern of Mycobacterium chelonae-abscessus Infection

To the Editor:

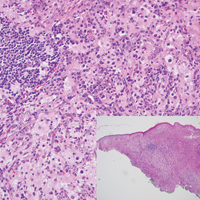

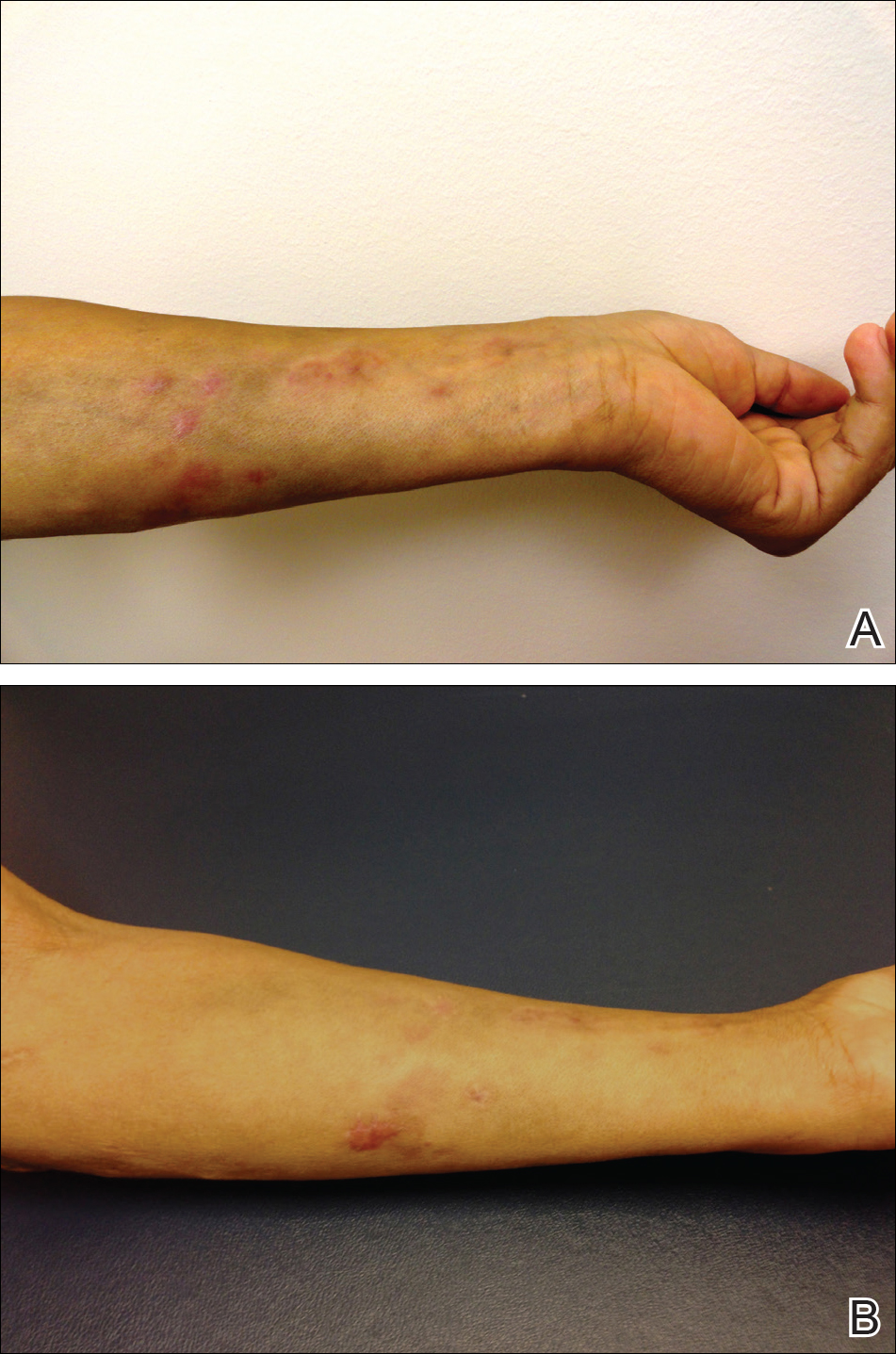

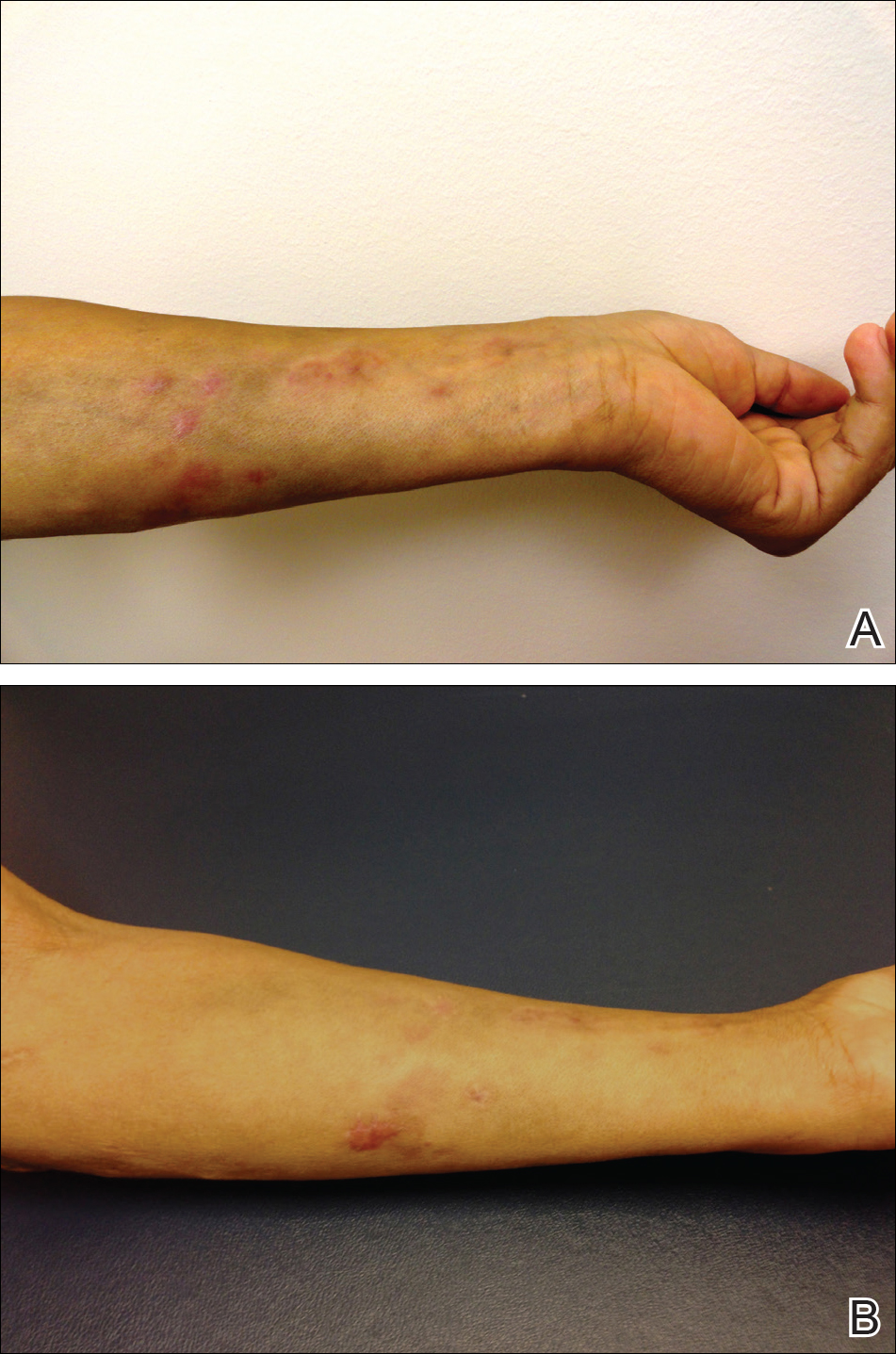

We present a case of Mycobacterium chelonae-abscessus cutaneous infection in a sporotrichoid pattern, a rare presentation most often found in immunocompromised patients. A 34-year-old man with lupus nephritis who was taking oral prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil, and hydroxychloroquine presented with multiple erythematous fluctuant nodules and plaques on the left volar forearm in a sporotrichoid pattern of 3 months’ duration (Figure, A). He denied recent travel, exposure to fish or fish tanks, and penetrating wounds. Punch biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and scarring with negative tissue cultures. Repeat biopsies and cultures were obtained when the lesions increased in number over 2 months.

Final biopsy showed upper dermal granulomatous inflammation with karyorrhectic debris, suggesting infection, and acid-fast bacilli. Culture grew M chelonae-abscessus on Löwenstein-Jensen agar at 37°C and blood culture media from which the complex was identified using high-performance liquid chromatography. Empiric therapy with renal dosing based on the Infectious Diseases Society of America statement of susceptibilities1 was initiated with clarithromycin, doxycycline, and ciprofloxacin for 4 months. Furthermore, the prednisone dose was tapered to 7.5 mg daily. Two months later, the lesions regressed and ciprofloxacin was discontinued (Figure, B).

The sporotrichoid spread of nodules suggests infection with mycobacteria, Sporothrix schenckii, Leishmania, Francisella tularensis, or Nocardia. Most cultures for nontuberculous mycobacteria will grow on Löwenstein-Jensen agar between 28°C and 37°C. Runyon rapidly growing (group IV) mycobacteria are defined by their ubiquitous presence in the environment and ability to develop colonies in 7 days.2 Cutaneous infections are increasing in prevalence, as reported in a retrospective study spanning nearly 30 years.3 The presentation is variable but often includes the distal extremities and usually is a nodule, ulcer, or abscess at a single site; a sporotrichoid pattern is more rare. Preceding skin trauma is the major risk factor for immunocompetent hosts, and the infection can spontaneously resolve in 8 to 12 months.1 In contrast, immunosuppressed patients may have no known source of infection and often have a progressive course with an increasing number of lesions and increased time until clearance.4

It is difficult to differentiate M chelonae and M abscessus based on growth characteristics, and they share the same 16S ribosomal RNA sequence commonly used to differentiate other mycobacterial species.2 Mycobacterium abscessus can be more difficult to treat, thus distinction via polymerase chain reaction of the heat-shock protein 65 gene, hsp65, can be valuable in cases recalcitrant to initial therapy.1

The likelihood of M chelonae and M abscessus isolates to be initially sensitive to clarithromycin is 100%,1 and this antibiotic remains the cornerstone of therapy. A clinical trial of treatments for M chelonae-abscessus found that clarithromycin monotherapy can be successful or complicated by resistance5; therefore, multidrug therapy is recommended. The antibiotic regimen for our patient was chosen to limit renal toxicity.

In summary, we report a case of M chelonae-abscessus cutaneous infection in a sporotrichoid pattern in a patient with lupus nephritis on immunosuppressive drugs. As the incidence of rapidly growing mycobacterial cutaneous infections rises, dermatologists must be aware of this pattern of infection.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- De Groote MA, Huitt G. Infections due to rapidly-growing Mycobacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1756-1763.

- Wentworth AB, Drage LA, Wengenack NL, et al. Increased incidence of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, 1980 to 2009: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:38-45.

- Lee WJ, Kang SM, Sung H, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections of the skin: a retrospective study of 29 cases. J Dermatol. 2010:37:965-972.

- Wallace RJ, Tanner D, Brennan PJ, et al. Clinical trial of clarithromycin for cutaneous (disseminated) infection due to Mycobacterium chelonae. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:482-486.

To the Editor:

We present a case of Mycobacterium chelonae-abscessus cutaneous infection in a sporotrichoid pattern, a rare presentation most often found in immunocompromised patients. A 34-year-old man with lupus nephritis who was taking oral prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil, and hydroxychloroquine presented with multiple erythematous fluctuant nodules and plaques on the left volar forearm in a sporotrichoid pattern of 3 months’ duration (Figure, A). He denied recent travel, exposure to fish or fish tanks, and penetrating wounds. Punch biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and scarring with negative tissue cultures. Repeat biopsies and cultures were obtained when the lesions increased in number over 2 months.

Final biopsy showed upper dermal granulomatous inflammation with karyorrhectic debris, suggesting infection, and acid-fast bacilli. Culture grew M chelonae-abscessus on Löwenstein-Jensen agar at 37°C and blood culture media from which the complex was identified using high-performance liquid chromatography. Empiric therapy with renal dosing based on the Infectious Diseases Society of America statement of susceptibilities1 was initiated with clarithromycin, doxycycline, and ciprofloxacin for 4 months. Furthermore, the prednisone dose was tapered to 7.5 mg daily. Two months later, the lesions regressed and ciprofloxacin was discontinued (Figure, B).

The sporotrichoid spread of nodules suggests infection with mycobacteria, Sporothrix schenckii, Leishmania, Francisella tularensis, or Nocardia. Most cultures for nontuberculous mycobacteria will grow on Löwenstein-Jensen agar between 28°C and 37°C. Runyon rapidly growing (group IV) mycobacteria are defined by their ubiquitous presence in the environment and ability to develop colonies in 7 days.2 Cutaneous infections are increasing in prevalence, as reported in a retrospective study spanning nearly 30 years.3 The presentation is variable but often includes the distal extremities and usually is a nodule, ulcer, or abscess at a single site; a sporotrichoid pattern is more rare. Preceding skin trauma is the major risk factor for immunocompetent hosts, and the infection can spontaneously resolve in 8 to 12 months.1 In contrast, immunosuppressed patients may have no known source of infection and often have a progressive course with an increasing number of lesions and increased time until clearance.4

It is difficult to differentiate M chelonae and M abscessus based on growth characteristics, and they share the same 16S ribosomal RNA sequence commonly used to differentiate other mycobacterial species.2 Mycobacterium abscessus can be more difficult to treat, thus distinction via polymerase chain reaction of the heat-shock protein 65 gene, hsp65, can be valuable in cases recalcitrant to initial therapy.1

The likelihood of M chelonae and M abscessus isolates to be initially sensitive to clarithromycin is 100%,1 and this antibiotic remains the cornerstone of therapy. A clinical trial of treatments for M chelonae-abscessus found that clarithromycin monotherapy can be successful or complicated by resistance5; therefore, multidrug therapy is recommended. The antibiotic regimen for our patient was chosen to limit renal toxicity.

In summary, we report a case of M chelonae-abscessus cutaneous infection in a sporotrichoid pattern in a patient with lupus nephritis on immunosuppressive drugs. As the incidence of rapidly growing mycobacterial cutaneous infections rises, dermatologists must be aware of this pattern of infection.

To the Editor:

We present a case of Mycobacterium chelonae-abscessus cutaneous infection in a sporotrichoid pattern, a rare presentation most often found in immunocompromised patients. A 34-year-old man with lupus nephritis who was taking oral prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil, and hydroxychloroquine presented with multiple erythematous fluctuant nodules and plaques on the left volar forearm in a sporotrichoid pattern of 3 months’ duration (Figure, A). He denied recent travel, exposure to fish or fish tanks, and penetrating wounds. Punch biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and scarring with negative tissue cultures. Repeat biopsies and cultures were obtained when the lesions increased in number over 2 months.

Final biopsy showed upper dermal granulomatous inflammation with karyorrhectic debris, suggesting infection, and acid-fast bacilli. Culture grew M chelonae-abscessus on Löwenstein-Jensen agar at 37°C and blood culture media from which the complex was identified using high-performance liquid chromatography. Empiric therapy with renal dosing based on the Infectious Diseases Society of America statement of susceptibilities1 was initiated with clarithromycin, doxycycline, and ciprofloxacin for 4 months. Furthermore, the prednisone dose was tapered to 7.5 mg daily. Two months later, the lesions regressed and ciprofloxacin was discontinued (Figure, B).

The sporotrichoid spread of nodules suggests infection with mycobacteria, Sporothrix schenckii, Leishmania, Francisella tularensis, or Nocardia. Most cultures for nontuberculous mycobacteria will grow on Löwenstein-Jensen agar between 28°C and 37°C. Runyon rapidly growing (group IV) mycobacteria are defined by their ubiquitous presence in the environment and ability to develop colonies in 7 days.2 Cutaneous infections are increasing in prevalence, as reported in a retrospective study spanning nearly 30 years.3 The presentation is variable but often includes the distal extremities and usually is a nodule, ulcer, or abscess at a single site; a sporotrichoid pattern is more rare. Preceding skin trauma is the major risk factor for immunocompetent hosts, and the infection can spontaneously resolve in 8 to 12 months.1 In contrast, immunosuppressed patients may have no known source of infection and often have a progressive course with an increasing number of lesions and increased time until clearance.4

It is difficult to differentiate M chelonae and M abscessus based on growth characteristics, and they share the same 16S ribosomal RNA sequence commonly used to differentiate other mycobacterial species.2 Mycobacterium abscessus can be more difficult to treat, thus distinction via polymerase chain reaction of the heat-shock protein 65 gene, hsp65, can be valuable in cases recalcitrant to initial therapy.1

The likelihood of M chelonae and M abscessus isolates to be initially sensitive to clarithromycin is 100%,1 and this antibiotic remains the cornerstone of therapy. A clinical trial of treatments for M chelonae-abscessus found that clarithromycin monotherapy can be successful or complicated by resistance5; therefore, multidrug therapy is recommended. The antibiotic regimen for our patient was chosen to limit renal toxicity.

In summary, we report a case of M chelonae-abscessus cutaneous infection in a sporotrichoid pattern in a patient with lupus nephritis on immunosuppressive drugs. As the incidence of rapidly growing mycobacterial cutaneous infections rises, dermatologists must be aware of this pattern of infection.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- De Groote MA, Huitt G. Infections due to rapidly-growing Mycobacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1756-1763.

- Wentworth AB, Drage LA, Wengenack NL, et al. Increased incidence of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, 1980 to 2009: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:38-45.

- Lee WJ, Kang SM, Sung H, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections of the skin: a retrospective study of 29 cases. J Dermatol. 2010:37:965-972.

- Wallace RJ, Tanner D, Brennan PJ, et al. Clinical trial of clarithromycin for cutaneous (disseminated) infection due to Mycobacterium chelonae. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:482-486.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- De Groote MA, Huitt G. Infections due to rapidly-growing Mycobacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1756-1763.

- Wentworth AB, Drage LA, Wengenack NL, et al. Increased incidence of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, 1980 to 2009: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:38-45.

- Lee WJ, Kang SM, Sung H, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections of the skin: a retrospective study of 29 cases. J Dermatol. 2010:37:965-972.

- Wallace RJ, Tanner D, Brennan PJ, et al. Clinical trial of clarithromycin for cutaneous (disseminated) infection due to Mycobacterium chelonae. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:482-486.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should consider atypical mycobacterial infections, including rapidly growing mycobacteria, in the differential diagnosis for lesions with sporotrichoid-pattern spread.

- Multidrug therapy often is required for treatment of infection caused by Mycobacteria chelonae-abscessus complex.

Microneedling With Stem Cells

Tender Edematous Nodules on the Hand

The Diagnosis: Ecthyma Contagiosum (Orf)

Orf, or ecthyma contagiosum, is a zoonotic cutaneous infection caused by the orf DNA virus of the genus Parapoxvirus of the family Poxviridae. It is transmitted to humans through direct contact with infected animals, namely sheep and goats, and as such is most commonly seen in patients with occupational exposure to these animals such as butchers, farmers, veterinarians, and shepherds.1,2 Human-to-human transmission is exceedingly rare in immunocompetent patients.2,3 In affected animals, lesions usually are found around the mouth, muzzle, and eyes. In humans, hands are the most commonly affected site, and lesions occur 3 to 10 days after contact. Clinically, the lesions are nonspecific, and our patient presented with tender, erythematous, edematous nodules on the left hand. The differential diagnosis is broad and includes a milker's nodule, pyogenic granuloma, tularemia, anthrax, atypical mycobacterial infection, and sporotrichosis.1,4,5

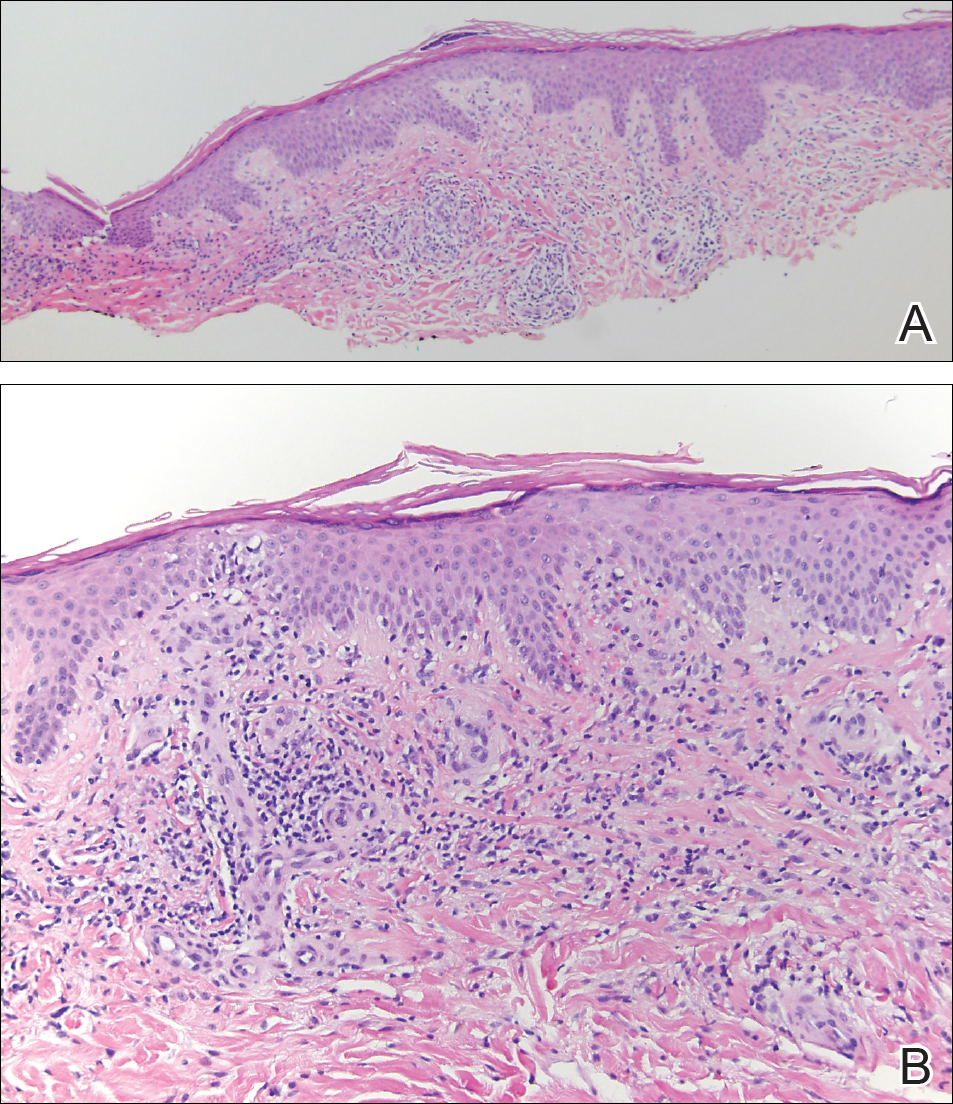

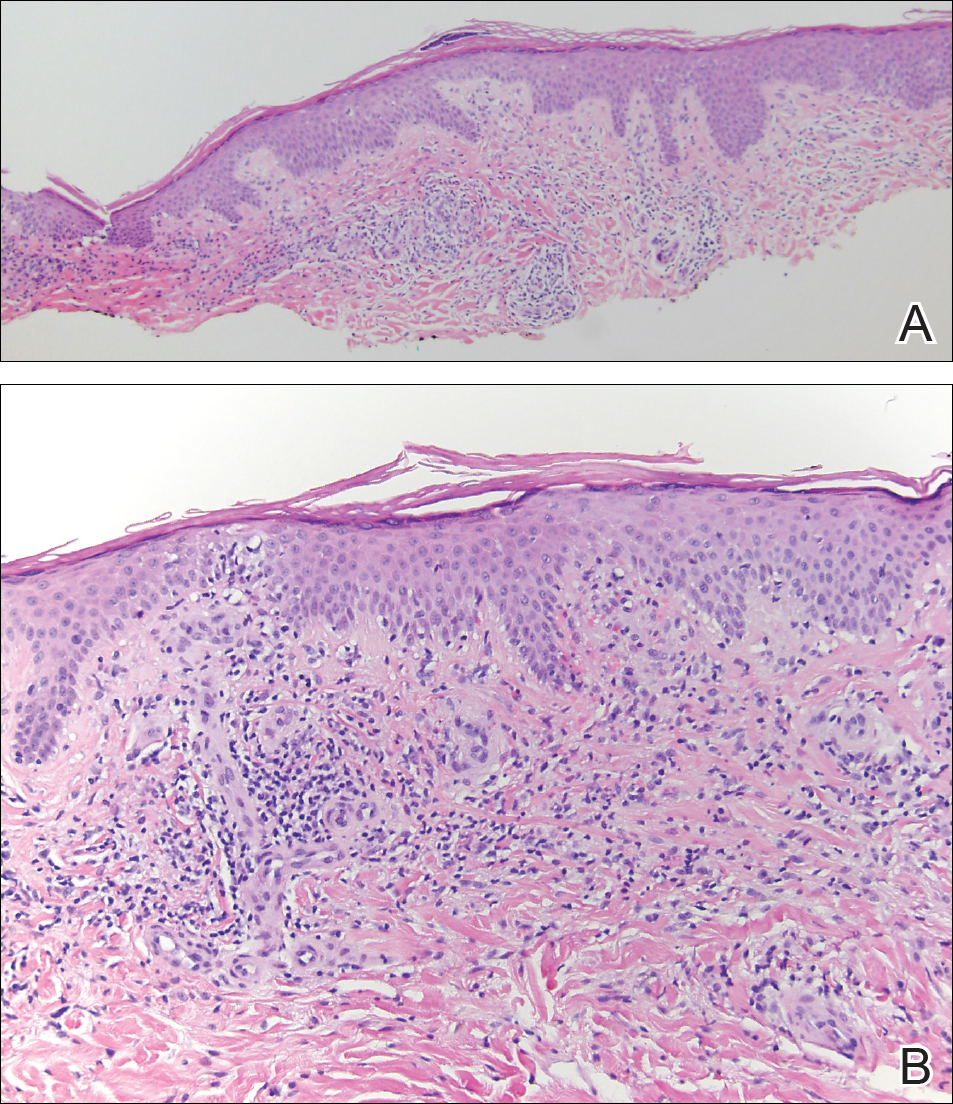

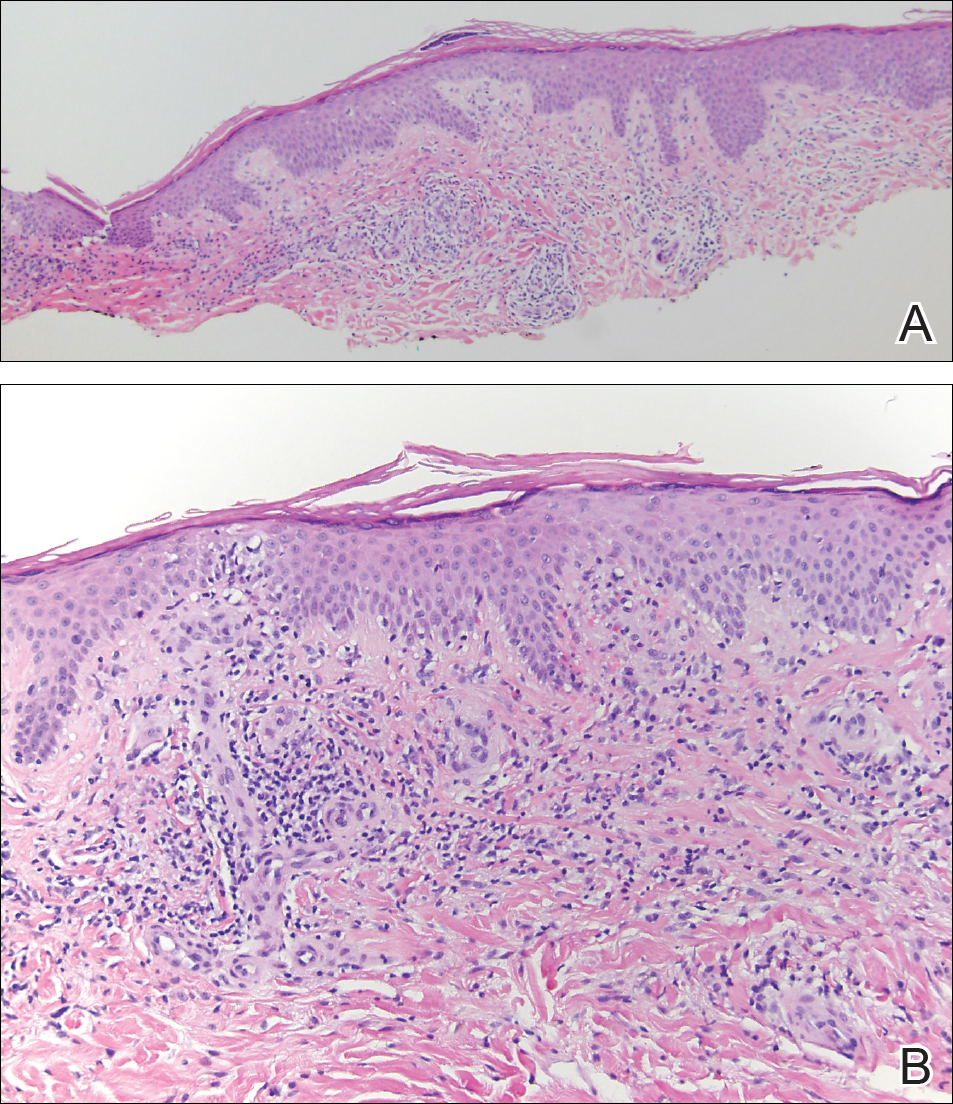

The diagnosis usually is made with a thorough history and examination, but in cases of uncertainty, routine pathology with hematoxylin and eosin staining, electron microscopy, or real-time polymerase chain reaction may be used.2-4 Histopathologically, lesions demonstrate intraepidermal vesicles, vacuolization of keratinocytes of the upper epidermis with characteristic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies, rete ridge elongation, and dilated vessels in the intervening dermal papillae. Central necrosis may occur in well-developed lesions.2,6 Interestingly, our patient's biopsy exhibited all of these findings (Figure). Immunostains for cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus were negative, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and acid-fast bacillus stains also were negative.

Our patient also developed lymphangitic streaking suggestive of a bacterial superinfection and was treated with a course of intravenous antibiotics. She eventually was discharged with reassurance, wound care instructions, and outpatient antibiotics. She returned to an outside institution's emergency department for further evaluation, and she was admitted for workup. A lesional swab was sent for real-time polymerase chain reaction, which confirmed the diagnosis as orf. When the patient was contacted for follow-up 1 week after biopsy, the hand lesions had notably improved.

Orf is self-limited and typically resolves within 4 to 8 weeks after undergoing evolution through 5 described stages. The maculopapular stage is denoted by enlarging erythematous macule. The targetoid stage is described by a red center within a white halo surrounded by a broader red halo. The nodular stage is self-descriptive. The regenerative and regression stages describe the progressively improving, drier, and crusted nodules.3

Because orf is self-limited, no treatment is required, and patients should be counseled that their lesions should resolve within weeks. Complications include lymphangitis, secondary bacterial infection, and erythema multiforme.1,2,4,5 Immunocompromised patients may develop recalcitrant, giant, or multiple lesions that may be treated with topical imiquimod, topical cidofovir, intralesional interferon alfa, or surgical excision.1,2,4,7

We present a case of orf to remind practitioners of this rare entity. Although the disease is endemic worldwide, it likely is underreported due to its self-limited nature.2,4 A careful history may reveal the diagnosis, and overtreatment with antibiotics, many of which have their own significant side-effect profile, can then be avoided.

Acknowledgment

We thank Eric Behling, MD (Camden, New Jersey), for his contributions in obtaining the histologic images.

- Veraldi S, Nazzaro G, Vaira F, et al. Presentation of orf (ecthyma contagiosum) after sheep slaughtering for religious feasts. Infection. 2014;42:767-769.

- Al-Salam S, Nowotny N, Sohail MR, et al. Ecthyma contagiosum (orf)--report of a human case from the United Arab Emirates and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:603-607.

- Thurman RJ, Fitch RW. Images in clinical medicine. contagious ecthyma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:E12.

- Meier R, Sommacal A, Stahel A, et al. Orf--an orphan disease? JRSM Open. 2015;6:2054270415593718.

- Joseph RH, Haddad FA, Matthews AL, et al. Erythema multiforme after orf virus infection: a report of two cases and literature review. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:385-390.

- Xu X, Yun SJ, Erikson L, et al. Diseases caused by viruses. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:781-815.

- Koufakis T, Katsaitis P, Gabranis I. Orf disease: a report of a case. Braz J Infect Dis. 2014;18:568-569.

The Diagnosis: Ecthyma Contagiosum (Orf)

Orf, or ecthyma contagiosum, is a zoonotic cutaneous infection caused by the orf DNA virus of the genus Parapoxvirus of the family Poxviridae. It is transmitted to humans through direct contact with infected animals, namely sheep and goats, and as such is most commonly seen in patients with occupational exposure to these animals such as butchers, farmers, veterinarians, and shepherds.1,2 Human-to-human transmission is exceedingly rare in immunocompetent patients.2,3 In affected animals, lesions usually are found around the mouth, muzzle, and eyes. In humans, hands are the most commonly affected site, and lesions occur 3 to 10 days after contact. Clinically, the lesions are nonspecific, and our patient presented with tender, erythematous, edematous nodules on the left hand. The differential diagnosis is broad and includes a milker's nodule, pyogenic granuloma, tularemia, anthrax, atypical mycobacterial infection, and sporotrichosis.1,4,5

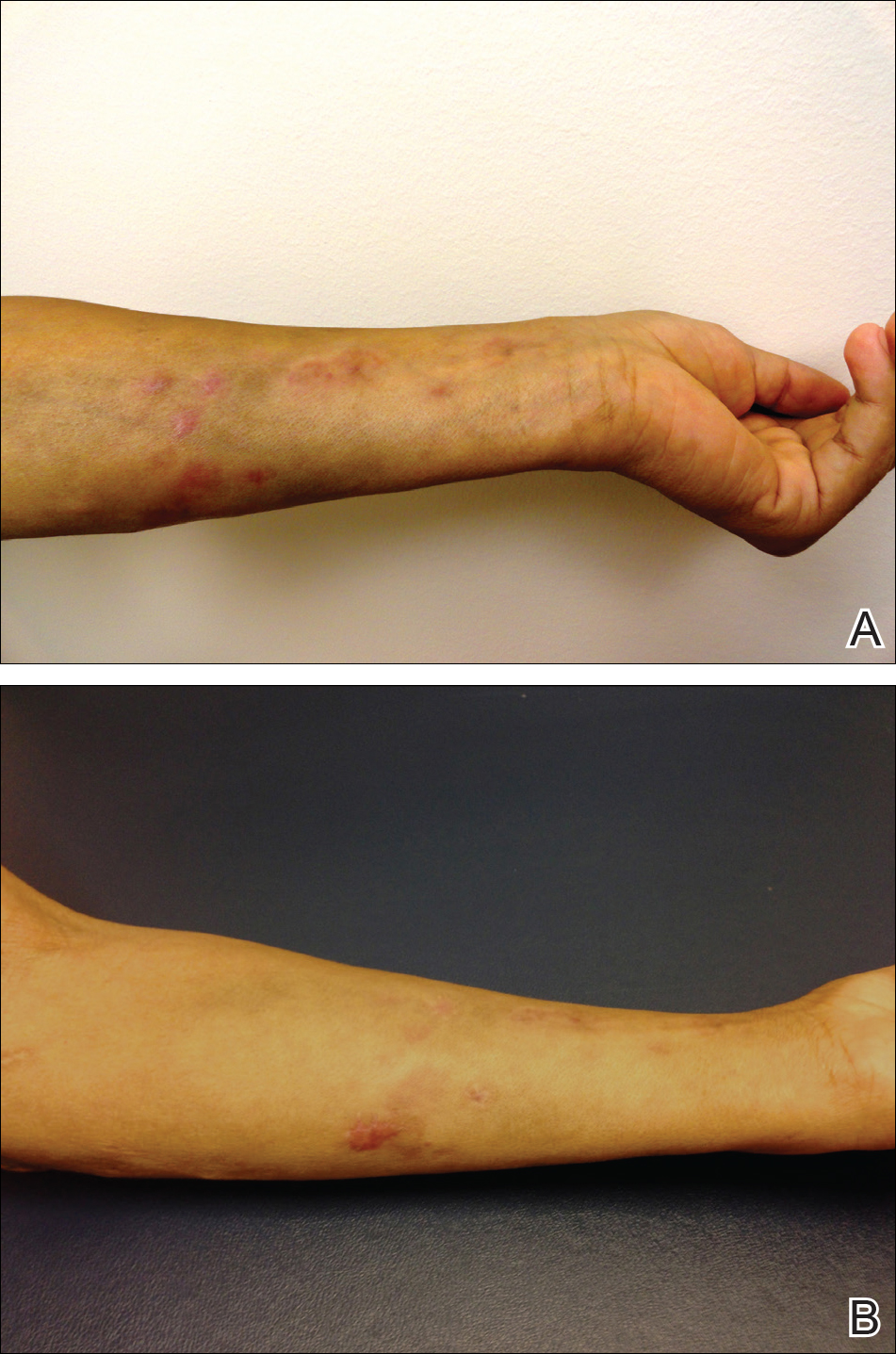

The diagnosis usually is made with a thorough history and examination, but in cases of uncertainty, routine pathology with hematoxylin and eosin staining, electron microscopy, or real-time polymerase chain reaction may be used.2-4 Histopathologically, lesions demonstrate intraepidermal vesicles, vacuolization of keratinocytes of the upper epidermis with characteristic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies, rete ridge elongation, and dilated vessels in the intervening dermal papillae. Central necrosis may occur in well-developed lesions.2,6 Interestingly, our patient's biopsy exhibited all of these findings (Figure). Immunostains for cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus were negative, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and acid-fast bacillus stains also were negative.

Our patient also developed lymphangitic streaking suggestive of a bacterial superinfection and was treated with a course of intravenous antibiotics. She eventually was discharged with reassurance, wound care instructions, and outpatient antibiotics. She returned to an outside institution's emergency department for further evaluation, and she was admitted for workup. A lesional swab was sent for real-time polymerase chain reaction, which confirmed the diagnosis as orf. When the patient was contacted for follow-up 1 week after biopsy, the hand lesions had notably improved.

Orf is self-limited and typically resolves within 4 to 8 weeks after undergoing evolution through 5 described stages. The maculopapular stage is denoted by enlarging erythematous macule. The targetoid stage is described by a red center within a white halo surrounded by a broader red halo. The nodular stage is self-descriptive. The regenerative and regression stages describe the progressively improving, drier, and crusted nodules.3

Because orf is self-limited, no treatment is required, and patients should be counseled that their lesions should resolve within weeks. Complications include lymphangitis, secondary bacterial infection, and erythema multiforme.1,2,4,5 Immunocompromised patients may develop recalcitrant, giant, or multiple lesions that may be treated with topical imiquimod, topical cidofovir, intralesional interferon alfa, or surgical excision.1,2,4,7

We present a case of orf to remind practitioners of this rare entity. Although the disease is endemic worldwide, it likely is underreported due to its self-limited nature.2,4 A careful history may reveal the diagnosis, and overtreatment with antibiotics, many of which have their own significant side-effect profile, can then be avoided.

Acknowledgment

We thank Eric Behling, MD (Camden, New Jersey), for his contributions in obtaining the histologic images.

The Diagnosis: Ecthyma Contagiosum (Orf)

Orf, or ecthyma contagiosum, is a zoonotic cutaneous infection caused by the orf DNA virus of the genus Parapoxvirus of the family Poxviridae. It is transmitted to humans through direct contact with infected animals, namely sheep and goats, and as such is most commonly seen in patients with occupational exposure to these animals such as butchers, farmers, veterinarians, and shepherds.1,2 Human-to-human transmission is exceedingly rare in immunocompetent patients.2,3 In affected animals, lesions usually are found around the mouth, muzzle, and eyes. In humans, hands are the most commonly affected site, and lesions occur 3 to 10 days after contact. Clinically, the lesions are nonspecific, and our patient presented with tender, erythematous, edematous nodules on the left hand. The differential diagnosis is broad and includes a milker's nodule, pyogenic granuloma, tularemia, anthrax, atypical mycobacterial infection, and sporotrichosis.1,4,5

The diagnosis usually is made with a thorough history and examination, but in cases of uncertainty, routine pathology with hematoxylin and eosin staining, electron microscopy, or real-time polymerase chain reaction may be used.2-4 Histopathologically, lesions demonstrate intraepidermal vesicles, vacuolization of keratinocytes of the upper epidermis with characteristic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies, rete ridge elongation, and dilated vessels in the intervening dermal papillae. Central necrosis may occur in well-developed lesions.2,6 Interestingly, our patient's biopsy exhibited all of these findings (Figure). Immunostains for cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus were negative, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and acid-fast bacillus stains also were negative.

Our patient also developed lymphangitic streaking suggestive of a bacterial superinfection and was treated with a course of intravenous antibiotics. She eventually was discharged with reassurance, wound care instructions, and outpatient antibiotics. She returned to an outside institution's emergency department for further evaluation, and she was admitted for workup. A lesional swab was sent for real-time polymerase chain reaction, which confirmed the diagnosis as orf. When the patient was contacted for follow-up 1 week after biopsy, the hand lesions had notably improved.

Orf is self-limited and typically resolves within 4 to 8 weeks after undergoing evolution through 5 described stages. The maculopapular stage is denoted by enlarging erythematous macule. The targetoid stage is described by a red center within a white halo surrounded by a broader red halo. The nodular stage is self-descriptive. The regenerative and regression stages describe the progressively improving, drier, and crusted nodules.3

Because orf is self-limited, no treatment is required, and patients should be counseled that their lesions should resolve within weeks. Complications include lymphangitis, secondary bacterial infection, and erythema multiforme.1,2,4,5 Immunocompromised patients may develop recalcitrant, giant, or multiple lesions that may be treated with topical imiquimod, topical cidofovir, intralesional interferon alfa, or surgical excision.1,2,4,7

We present a case of orf to remind practitioners of this rare entity. Although the disease is endemic worldwide, it likely is underreported due to its self-limited nature.2,4 A careful history may reveal the diagnosis, and overtreatment with antibiotics, many of which have their own significant side-effect profile, can then be avoided.

Acknowledgment

We thank Eric Behling, MD (Camden, New Jersey), for his contributions in obtaining the histologic images.

- Veraldi S, Nazzaro G, Vaira F, et al. Presentation of orf (ecthyma contagiosum) after sheep slaughtering for religious feasts. Infection. 2014;42:767-769.

- Al-Salam S, Nowotny N, Sohail MR, et al. Ecthyma contagiosum (orf)--report of a human case from the United Arab Emirates and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:603-607.

- Thurman RJ, Fitch RW. Images in clinical medicine. contagious ecthyma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:E12.

- Meier R, Sommacal A, Stahel A, et al. Orf--an orphan disease? JRSM Open. 2015;6:2054270415593718.

- Joseph RH, Haddad FA, Matthews AL, et al. Erythema multiforme after orf virus infection: a report of two cases and literature review. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:385-390.

- Xu X, Yun SJ, Erikson L, et al. Diseases caused by viruses. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:781-815.

- Koufakis T, Katsaitis P, Gabranis I. Orf disease: a report of a case. Braz J Infect Dis. 2014;18:568-569.

- Veraldi S, Nazzaro G, Vaira F, et al. Presentation of orf (ecthyma contagiosum) after sheep slaughtering for religious feasts. Infection. 2014;42:767-769.

- Al-Salam S, Nowotny N, Sohail MR, et al. Ecthyma contagiosum (orf)--report of a human case from the United Arab Emirates and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:603-607.

- Thurman RJ, Fitch RW. Images in clinical medicine. contagious ecthyma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:E12.

- Meier R, Sommacal A, Stahel A, et al. Orf--an orphan disease? JRSM Open. 2015;6:2054270415593718.

- Joseph RH, Haddad FA, Matthews AL, et al. Erythema multiforme after orf virus infection: a report of two cases and literature review. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:385-390.

- Xu X, Yun SJ, Erikson L, et al. Diseases caused by viruses. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:781-815.

- Koufakis T, Katsaitis P, Gabranis I. Orf disease: a report of a case. Braz J Infect Dis. 2014;18:568-569.

A 57-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of a rash on the left hand of 2 weeks' duration. She described pinpoint red lesions on the left palm, as well as the third, fourth, and fifth fingers, which gradually enlarged and became painful. She denied any specific trauma but recalled cutting her hand on a piece of metal in the ground prior to the onset of the rash. She worked on a farm and bottle-fed sheep and chickens. Physical examination revealed tender edematous nodules with central gray pustules, and the left axillary lymph node was enlarged and tender. Ulceration was not appreciated. Various antibiotics including cephalexin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and clindamycin were prescribed during prior ED visits, but she reported no improvement with these medications. She remained afebrile throughout the course of the hand rash, and laboratory workup was consistently unremarkable. Two sets of herpes simplex virus cultures from the ED visits showed no growth, and a hand radiograph also was normal. Medical history included coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, mitral regurgitation, and hyperlipidemia.

Making Practice Perfect Download

Please click either of the links below to download your free eBook

Onecount Call To Arms

Orange Nodules on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown etiology. It has 2 forms: limited cutaneous and systemic. The systemic form, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, affects the lymph nodes and other organs at times. The disease is characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes in the lymph nodes, most commonly in the cervical basin1; however, the inguinal, axillary, mediastinal, or para-aortic nodes also may be affected.1,2 The skin is the most common site of extranodal disease, seen in approximately 10% of cases.1 Cutaneous involvement often is in the facial area but also can be found on the trunk, ears, neck, arms, legs, and genitals. Clinically, skin lesions appear as papules, plaques, and/or nodules.2

Histopathologic examination of Rosai-Dorfman disease generally shows a dense sheetlike dermal infiltrate of large polygonal histiocytes (Figure 1). Histiocytes may display pale pink or clear cytoplasm. The pathognomonic finding is emperipolesis, which consists of histiocytes with engulfed lymphocytes, erythrocytes, plasma cells, and/or granulocytes surrounded by a clear halo. Immunohistochemical staining also is characteristic, with lesional histiocytes showing expression of S-100 protein (Figure 1, inset) and CD68. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is mixed, containing primarily plasma cells but also lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.

Blastomycosis (Figure 2) is a systemic infection due to inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia. Primary infection occurs in the lungs, and with dissemination the skin is the most common subsequently involved organ.3 Cutaneous blastomycosis shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic microabscesses and a dense dermal infiltrate containing suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The nonpigmented yeast phase typically is 8 to 15 µm in length with a refractile cell wall and characteristic single, broad-based budding.3

Granuloma faciale (Figure 3) is a rare disease with unknown etiology characterized by reddish brown plaques or nodules most commonly occurring on the face.4,5 Histology shows a dense nodular dermal infiltrate with a grenz zone. The infiltrate is mixed, containing mostly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present with associated extravasated erythrocytes. In chronic fibrosing granuloma faciale, lesions can demonstrate fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition, similar to erythema elevatum diutinum.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (Figure 4) is a common histiocytic disease of early childhood, though adult cases have been reported.6 Tumors are found on the head and trunk and are typically firm, reddish yellow papules or nodules.6,7 Histologic examination shows a nodular infiltrate of foamy histiocytes in the superficial dermis. Touton-type multinucleated giant cells with a peripheral rim of xanthomatized foamy cytoplasm and a wreathlike arrangement of nuclei are characteristic. Associated eosinophils are seen. No emperipolesis is present.

Reticulohistiocytoma (Figure 5) is a benign dermal lesion that presents as solitary or less commonly multiple red-brown papules or nodules.8 Lesions consist of well-delineated nodular aggregates of histiocytes containing a finely granular eosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm. Few, if any, eosinophils are found. The lack of Touton multinucleated giant cells or emperipolesis and lack of expression of S-100 protein helps to distinguish reticulohistiocytoma from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

- Kutlubay Z, Bairamov O, Sevim A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report with nodal and cutaneous involvement and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:353-357.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyrí J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Tanz WS, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Cutis. 1994;54:241-245.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatology Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21725.

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown etiology. It has 2 forms: limited cutaneous and systemic. The systemic form, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, affects the lymph nodes and other organs at times. The disease is characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes in the lymph nodes, most commonly in the cervical basin1; however, the inguinal, axillary, mediastinal, or para-aortic nodes also may be affected.1,2 The skin is the most common site of extranodal disease, seen in approximately 10% of cases.1 Cutaneous involvement often is in the facial area but also can be found on the trunk, ears, neck, arms, legs, and genitals. Clinically, skin lesions appear as papules, plaques, and/or nodules.2

Histopathologic examination of Rosai-Dorfman disease generally shows a dense sheetlike dermal infiltrate of large polygonal histiocytes (Figure 1). Histiocytes may display pale pink or clear cytoplasm. The pathognomonic finding is emperipolesis, which consists of histiocytes with engulfed lymphocytes, erythrocytes, plasma cells, and/or granulocytes surrounded by a clear halo. Immunohistochemical staining also is characteristic, with lesional histiocytes showing expression of S-100 protein (Figure 1, inset) and CD68. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is mixed, containing primarily plasma cells but also lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.

Blastomycosis (Figure 2) is a systemic infection due to inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia. Primary infection occurs in the lungs, and with dissemination the skin is the most common subsequently involved organ.3 Cutaneous blastomycosis shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic microabscesses and a dense dermal infiltrate containing suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The nonpigmented yeast phase typically is 8 to 15 µm in length with a refractile cell wall and characteristic single, broad-based budding.3

Granuloma faciale (Figure 3) is a rare disease with unknown etiology characterized by reddish brown plaques or nodules most commonly occurring on the face.4,5 Histology shows a dense nodular dermal infiltrate with a grenz zone. The infiltrate is mixed, containing mostly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present with associated extravasated erythrocytes. In chronic fibrosing granuloma faciale, lesions can demonstrate fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition, similar to erythema elevatum diutinum.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (Figure 4) is a common histiocytic disease of early childhood, though adult cases have been reported.6 Tumors are found on the head and trunk and are typically firm, reddish yellow papules or nodules.6,7 Histologic examination shows a nodular infiltrate of foamy histiocytes in the superficial dermis. Touton-type multinucleated giant cells with a peripheral rim of xanthomatized foamy cytoplasm and a wreathlike arrangement of nuclei are characteristic. Associated eosinophils are seen. No emperipolesis is present.

Reticulohistiocytoma (Figure 5) is a benign dermal lesion that presents as solitary or less commonly multiple red-brown papules or nodules.8 Lesions consist of well-delineated nodular aggregates of histiocytes containing a finely granular eosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm. Few, if any, eosinophils are found. The lack of Touton multinucleated giant cells or emperipolesis and lack of expression of S-100 protein helps to distinguish reticulohistiocytoma from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown etiology. It has 2 forms: limited cutaneous and systemic. The systemic form, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, affects the lymph nodes and other organs at times. The disease is characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes in the lymph nodes, most commonly in the cervical basin1; however, the inguinal, axillary, mediastinal, or para-aortic nodes also may be affected.1,2 The skin is the most common site of extranodal disease, seen in approximately 10% of cases.1 Cutaneous involvement often is in the facial area but also can be found on the trunk, ears, neck, arms, legs, and genitals. Clinically, skin lesions appear as papules, plaques, and/or nodules.2

Histopathologic examination of Rosai-Dorfman disease generally shows a dense sheetlike dermal infiltrate of large polygonal histiocytes (Figure 1). Histiocytes may display pale pink or clear cytoplasm. The pathognomonic finding is emperipolesis, which consists of histiocytes with engulfed lymphocytes, erythrocytes, plasma cells, and/or granulocytes surrounded by a clear halo. Immunohistochemical staining also is characteristic, with lesional histiocytes showing expression of S-100 protein (Figure 1, inset) and CD68. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is mixed, containing primarily plasma cells but also lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.

Blastomycosis (Figure 2) is a systemic infection due to inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia. Primary infection occurs in the lungs, and with dissemination the skin is the most common subsequently involved organ.3 Cutaneous blastomycosis shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic microabscesses and a dense dermal infiltrate containing suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The nonpigmented yeast phase typically is 8 to 15 µm in length with a refractile cell wall and characteristic single, broad-based budding.3

Granuloma faciale (Figure 3) is a rare disease with unknown etiology characterized by reddish brown plaques or nodules most commonly occurring on the face.4,5 Histology shows a dense nodular dermal infiltrate with a grenz zone. The infiltrate is mixed, containing mostly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present with associated extravasated erythrocytes. In chronic fibrosing granuloma faciale, lesions can demonstrate fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition, similar to erythema elevatum diutinum.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (Figure 4) is a common histiocytic disease of early childhood, though adult cases have been reported.6 Tumors are found on the head and trunk and are typically firm, reddish yellow papules or nodules.6,7 Histologic examination shows a nodular infiltrate of foamy histiocytes in the superficial dermis. Touton-type multinucleated giant cells with a peripheral rim of xanthomatized foamy cytoplasm and a wreathlike arrangement of nuclei are characteristic. Associated eosinophils are seen. No emperipolesis is present.

Reticulohistiocytoma (Figure 5) is a benign dermal lesion that presents as solitary or less commonly multiple red-brown papules or nodules.8 Lesions consist of well-delineated nodular aggregates of histiocytes containing a finely granular eosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm. Few, if any, eosinophils are found. The lack of Touton multinucleated giant cells or emperipolesis and lack of expression of S-100 protein helps to distinguish reticulohistiocytoma from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

- Kutlubay Z, Bairamov O, Sevim A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report with nodal and cutaneous involvement and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:353-357.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyrí J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Tanz WS, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Cutis. 1994;54:241-245.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatology Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21725.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

- Kutlubay Z, Bairamov O, Sevim A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report with nodal and cutaneous involvement and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:353-357.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyrí J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Tanz WS, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Cutis. 1994;54:241-245.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatology Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21725.

A 59-year-old man presented with itchy and mildly painful nodules on the head and neck of 7 months' duration. The patient denied fever, chills, unintentional weight loss, night sweats, and other systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed multiple firm pink-orange nodules of varying sizes distributed on the scalp, face, and neck. Right-sided, painless, bulky cervical lymphadenopathy also was noted. An incisional biopsy was performed.

The Atopic Dermatitis Biologic Era Has Begun

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a vexing multisystem disorder characterized by frequently recurrent, intrusive, and sometimes disabling itch and dermatitis. The itch may be present throughout the day but crescendos at bedtime or 1 to 2 hours after sleep initiation, resulting in disrupted sleep cycles, lack of rest, more hours scratching, daytime somnolence, poor work attendance and performance, and poor school attendance and performance.1

Atopic dermatitis is a lifelong disease that only remits in approximately half of patients.2 There is a need for a disease-specific systemic drug in AD. Phototherapy, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and azathioprine are nonspecific immunosuppressive agents that can be used off label for AD but may or may not be effective.3 Oral or intramuscular corticosteroids are associated with problematic side effects such as weight gain, osteoporosis, fractures, psychological problems, striae, buffalo hump, and steroid withdrawal symptoms and disease aggravation upon withdrawal (ie, flaring to a state worse than prior to steroid initiation).3,4

A biologic medication for AD has been long overdue. Psoriatic biologic medications have been tried in AD with occasional benefit in case reports but no major response in larger trials. Belloni et al5 reviewed early data on off-label usage of biologics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psoriasis or other indications applied to AD patients. In their review of cases, they make the point that results are variable and anti-B-cell activity may hold the greatest promise.5 On the other hand, a recent series of 3 patients showed limited response to rituximab in chronic AD,6 while a combination of omalizumab, an anti-IgE medication, and rituximab was helpful in some patients.7 Ultimately, the issue is that nonspecific biologics may or may not address the underlying disease factors in AD. Therefore, there has been a true need for biologic intervention targeted directly at the pathogenic mechanism of AD. Furthermore, the desire for a biologic targeted at AD is paired with the true need to have a medication so targeted that the drug would have little effect on the rest of the immune system, resulting in targeted immunomodulation without secondary risk of infections.

Wait no longer, that era arrived a few months ago with the rapid US Food and Drug Administration approval of dupilumab, an injectable medication used every 2 weeks for the therapy of moderate to severe AD. This fully human monoclonal antibody against the IL-4Rα subunit blocks IL-4 and IL-13, key inflammatory agents in the triggering of production of IgE and eosinophil activation. Even better than the fact that it is targeted are the excellent outcomes in the therapy of moderate to severe AD in adults and the minimal side-effect profile resulting in no requirements for laboratory screening or ongoing monitoring.8

Dupilumab seems to perform well, both clinically and in improving the lives of AD patients. Meta-analysis of trials involving dupilumab has shown improved health-related quality of life outcomes.9,10 Usage of dupilumab alone in clinical trials for 16 weeks (SOLO 1 and SOLO 2) has resulted in stunning reduction in disease severity with a limited side-effect profile, with patients most commonly reporting conjunctivitis.11 In real-world models where dupilumab is added into a regimen of topical corticosteroid usage (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS trial), patients fared even better with the combination, highlighting that this medication may best be used adjunctively to our skin care guidance as dermatologists.12

A new era for AD patients has arrived and we as practitioners are now fortunate to be able to therapeutically reach the worst cases of AD. The new era has only begun with dozens of new agents addressing a variety of interleukin pathways including IL-17 and IL-22 still under development. Ultimately, we hope that ongoing pediatric trials will allow us to glean the role of early disease intervention at the root cause of AD and address our abilities to prevent comorbidities and disease persistence. Will we be able to avert years of disabling disease? The future holds immense hope.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351.

- Somanunt S, Chinratanapisit S, Pacharn P, et al. The natural history of atopic dermatitis and its association with Atopic March [published online Dec 12, 2016]. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. doi:10.12932/AP0825.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- Hajar T, Leshem YA, Hanifin JM, et al; the National Eczema Association Task Force. A systematic review of topical corticosteroid withdrawal ("steroid addiction") in patients with atopic dermatitis and other dermatoses [published online January 13, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:541.e2-549.e2.

- Belloni B, Andres C, Ollert M, et al. Novel immunological approaches in the treatment of atopic eczema. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:423-427.

- McDonald BS, Jones J, Rustin M. Rituximab as a treatment for severe atopic eczema: failure to improve in three consecutive patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:45-47.

- Sánchez-Ramón S, Eguíluz-Gracia I, Rodríguez-Mazariego ME, et al. Sequential combined therapy with omalizumab and rituximab: a new approach to severe atopic dermatitis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23:190-196.

- D'Erme AM, Romanelli M, Chiricozzi A. Spotlight on dupilumab in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: design, development, and potential place in therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:1473-1480.

- Han Y, Chen Y, Liu X, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of adult atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials [published online May 4, 2017]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.015.

- Simpson EL. Dupilumab improves general health-related quality-of-life in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: pooled results from two randomized, controlled phase 3 clinical trials. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:243-248.

- Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al; SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 Investigators. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis [published online Sep 30, 2016]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335-2348.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [published online May 4, 2017]. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a vexing multisystem disorder characterized by frequently recurrent, intrusive, and sometimes disabling itch and dermatitis. The itch may be present throughout the day but crescendos at bedtime or 1 to 2 hours after sleep initiation, resulting in disrupted sleep cycles, lack of rest, more hours scratching, daytime somnolence, poor work attendance and performance, and poor school attendance and performance.1

Atopic dermatitis is a lifelong disease that only remits in approximately half of patients.2 There is a need for a disease-specific systemic drug in AD. Phototherapy, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and azathioprine are nonspecific immunosuppressive agents that can be used off label for AD but may or may not be effective.3 Oral or intramuscular corticosteroids are associated with problematic side effects such as weight gain, osteoporosis, fractures, psychological problems, striae, buffalo hump, and steroid withdrawal symptoms and disease aggravation upon withdrawal (ie, flaring to a state worse than prior to steroid initiation).3,4

A biologic medication for AD has been long overdue. Psoriatic biologic medications have been tried in AD with occasional benefit in case reports but no major response in larger trials. Belloni et al5 reviewed early data on off-label usage of biologics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psoriasis or other indications applied to AD patients. In their review of cases, they make the point that results are variable and anti-B-cell activity may hold the greatest promise.5 On the other hand, a recent series of 3 patients showed limited response to rituximab in chronic AD,6 while a combination of omalizumab, an anti-IgE medication, and rituximab was helpful in some patients.7 Ultimately, the issue is that nonspecific biologics may or may not address the underlying disease factors in AD. Therefore, there has been a true need for biologic intervention targeted directly at the pathogenic mechanism of AD. Furthermore, the desire for a biologic targeted at AD is paired with the true need to have a medication so targeted that the drug would have little effect on the rest of the immune system, resulting in targeted immunomodulation without secondary risk of infections.

Wait no longer, that era arrived a few months ago with the rapid US Food and Drug Administration approval of dupilumab, an injectable medication used every 2 weeks for the therapy of moderate to severe AD. This fully human monoclonal antibody against the IL-4Rα subunit blocks IL-4 and IL-13, key inflammatory agents in the triggering of production of IgE and eosinophil activation. Even better than the fact that it is targeted are the excellent outcomes in the therapy of moderate to severe AD in adults and the minimal side-effect profile resulting in no requirements for laboratory screening or ongoing monitoring.8

Dupilumab seems to perform well, both clinically and in improving the lives of AD patients. Meta-analysis of trials involving dupilumab has shown improved health-related quality of life outcomes.9,10 Usage of dupilumab alone in clinical trials for 16 weeks (SOLO 1 and SOLO 2) has resulted in stunning reduction in disease severity with a limited side-effect profile, with patients most commonly reporting conjunctivitis.11 In real-world models where dupilumab is added into a regimen of topical corticosteroid usage (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS trial), patients fared even better with the combination, highlighting that this medication may best be used adjunctively to our skin care guidance as dermatologists.12

A new era for AD patients has arrived and we as practitioners are now fortunate to be able to therapeutically reach the worst cases of AD. The new era has only begun with dozens of new agents addressing a variety of interleukin pathways including IL-17 and IL-22 still under development. Ultimately, we hope that ongoing pediatric trials will allow us to glean the role of early disease intervention at the root cause of AD and address our abilities to prevent comorbidities and disease persistence. Will we be able to avert years of disabling disease? The future holds immense hope.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a vexing multisystem disorder characterized by frequently recurrent, intrusive, and sometimes disabling itch and dermatitis. The itch may be present throughout the day but crescendos at bedtime or 1 to 2 hours after sleep initiation, resulting in disrupted sleep cycles, lack of rest, more hours scratching, daytime somnolence, poor work attendance and performance, and poor school attendance and performance.1

Atopic dermatitis is a lifelong disease that only remits in approximately half of patients.2 There is a need for a disease-specific systemic drug in AD. Phototherapy, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and azathioprine are nonspecific immunosuppressive agents that can be used off label for AD but may or may not be effective.3 Oral or intramuscular corticosteroids are associated with problematic side effects such as weight gain, osteoporosis, fractures, psychological problems, striae, buffalo hump, and steroid withdrawal symptoms and disease aggravation upon withdrawal (ie, flaring to a state worse than prior to steroid initiation).3,4

A biologic medication for AD has been long overdue. Psoriatic biologic medications have been tried in AD with occasional benefit in case reports but no major response in larger trials. Belloni et al5 reviewed early data on off-label usage of biologics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psoriasis or other indications applied to AD patients. In their review of cases, they make the point that results are variable and anti-B-cell activity may hold the greatest promise.5 On the other hand, a recent series of 3 patients showed limited response to rituximab in chronic AD,6 while a combination of omalizumab, an anti-IgE medication, and rituximab was helpful in some patients.7 Ultimately, the issue is that nonspecific biologics may or may not address the underlying disease factors in AD. Therefore, there has been a true need for biologic intervention targeted directly at the pathogenic mechanism of AD. Furthermore, the desire for a biologic targeted at AD is paired with the true need to have a medication so targeted that the drug would have little effect on the rest of the immune system, resulting in targeted immunomodulation without secondary risk of infections.

Wait no longer, that era arrived a few months ago with the rapid US Food and Drug Administration approval of dupilumab, an injectable medication used every 2 weeks for the therapy of moderate to severe AD. This fully human monoclonal antibody against the IL-4Rα subunit blocks IL-4 and IL-13, key inflammatory agents in the triggering of production of IgE and eosinophil activation. Even better than the fact that it is targeted are the excellent outcomes in the therapy of moderate to severe AD in adults and the minimal side-effect profile resulting in no requirements for laboratory screening or ongoing monitoring.8

Dupilumab seems to perform well, both clinically and in improving the lives of AD patients. Meta-analysis of trials involving dupilumab has shown improved health-related quality of life outcomes.9,10 Usage of dupilumab alone in clinical trials for 16 weeks (SOLO 1 and SOLO 2) has resulted in stunning reduction in disease severity with a limited side-effect profile, with patients most commonly reporting conjunctivitis.11 In real-world models where dupilumab is added into a regimen of topical corticosteroid usage (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS trial), patients fared even better with the combination, highlighting that this medication may best be used adjunctively to our skin care guidance as dermatologists.12

A new era for AD patients has arrived and we as practitioners are now fortunate to be able to therapeutically reach the worst cases of AD. The new era has only begun with dozens of new agents addressing a variety of interleukin pathways including IL-17 and IL-22 still under development. Ultimately, we hope that ongoing pediatric trials will allow us to glean the role of early disease intervention at the root cause of AD and address our abilities to prevent comorbidities and disease persistence. Will we be able to avert years of disabling disease? The future holds immense hope.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351.

- Somanunt S, Chinratanapisit S, Pacharn P, et al. The natural history of atopic dermatitis and its association with Atopic March [published online Dec 12, 2016]. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. doi:10.12932/AP0825.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- Hajar T, Leshem YA, Hanifin JM, et al; the National Eczema Association Task Force. A systematic review of topical corticosteroid withdrawal ("steroid addiction") in patients with atopic dermatitis and other dermatoses [published online January 13, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:541.e2-549.e2.

- Belloni B, Andres C, Ollert M, et al. Novel immunological approaches in the treatment of atopic eczema. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:423-427.

- McDonald BS, Jones J, Rustin M. Rituximab as a treatment for severe atopic eczema: failure to improve in three consecutive patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:45-47.

- Sánchez-Ramón S, Eguíluz-Gracia I, Rodríguez-Mazariego ME, et al. Sequential combined therapy with omalizumab and rituximab: a new approach to severe atopic dermatitis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23:190-196.

- D'Erme AM, Romanelli M, Chiricozzi A. Spotlight on dupilumab in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: design, development, and potential place in therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:1473-1480.

- Han Y, Chen Y, Liu X, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of adult atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials [published online May 4, 2017]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.015.

- Simpson EL. Dupilumab improves general health-related quality-of-life in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: pooled results from two randomized, controlled phase 3 clinical trials. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:243-248.

- Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al; SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 Investigators. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis [published online Sep 30, 2016]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335-2348.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [published online May 4, 2017]. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-351.

- Somanunt S, Chinratanapisit S, Pacharn P, et al. The natural history of atopic dermatitis and its association with Atopic March [published online Dec 12, 2016]. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. doi:10.12932/AP0825.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- Hajar T, Leshem YA, Hanifin JM, et al; the National Eczema Association Task Force. A systematic review of topical corticosteroid withdrawal ("steroid addiction") in patients with atopic dermatitis and other dermatoses [published online January 13, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:541.e2-549.e2.

- Belloni B, Andres C, Ollert M, et al. Novel immunological approaches in the treatment of atopic eczema. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:423-427.

- McDonald BS, Jones J, Rustin M. Rituximab as a treatment for severe atopic eczema: failure to improve in three consecutive patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:45-47.

- Sánchez-Ramón S, Eguíluz-Gracia I, Rodríguez-Mazariego ME, et al. Sequential combined therapy with omalizumab and rituximab: a new approach to severe atopic dermatitis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23:190-196.

- D'Erme AM, Romanelli M, Chiricozzi A. Spotlight on dupilumab in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: design, development, and potential place in therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:1473-1480.

- Han Y, Chen Y, Liu X, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of adult atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials [published online May 4, 2017]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.015.

- Simpson EL. Dupilumab improves general health-related quality-of-life in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: pooled results from two randomized, controlled phase 3 clinical trials. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:243-248.

- Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al; SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 Investigators. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis [published online Sep 30, 2016]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335-2348.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [published online May 4, 2017]. Lancet. 2017;389:2287-2303.

Hyperpigmented Patch on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Lichen Aureus

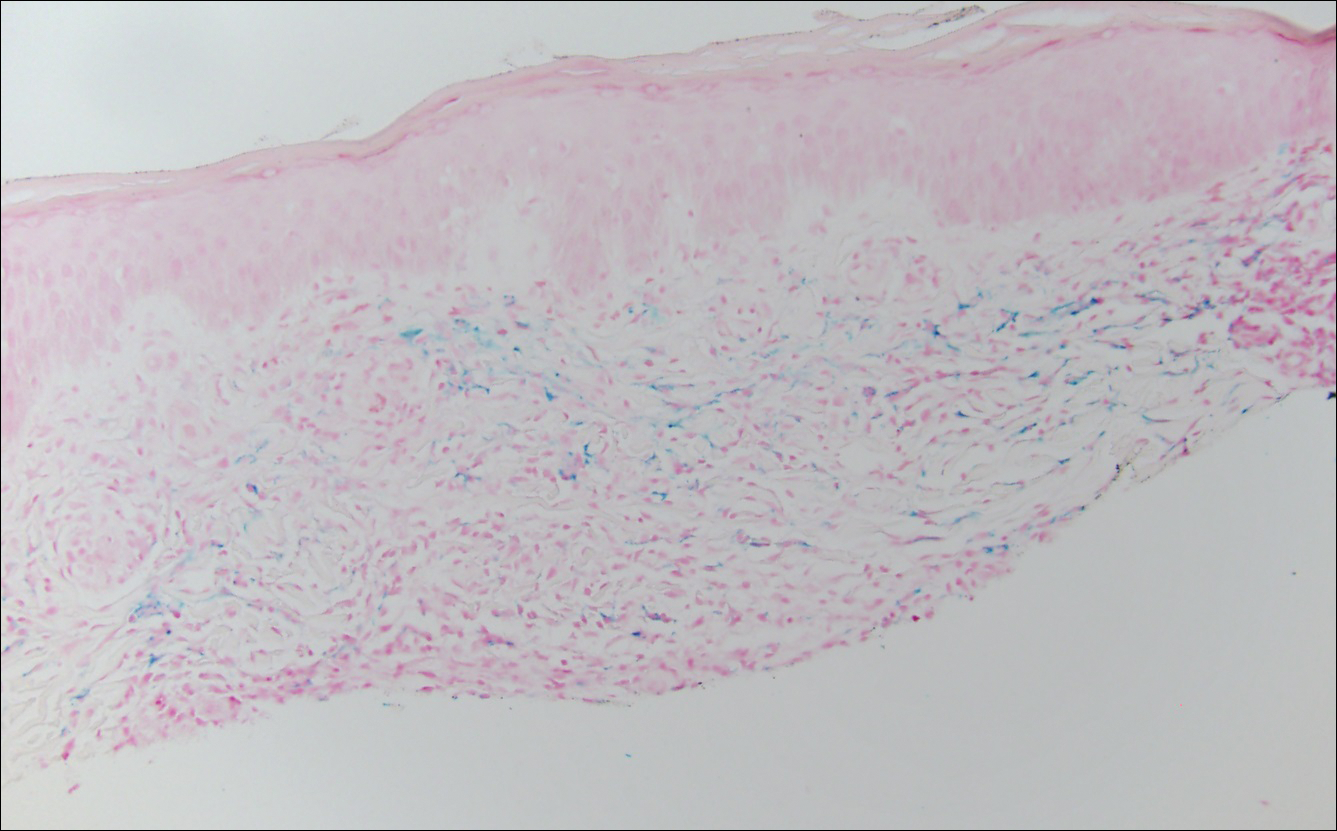

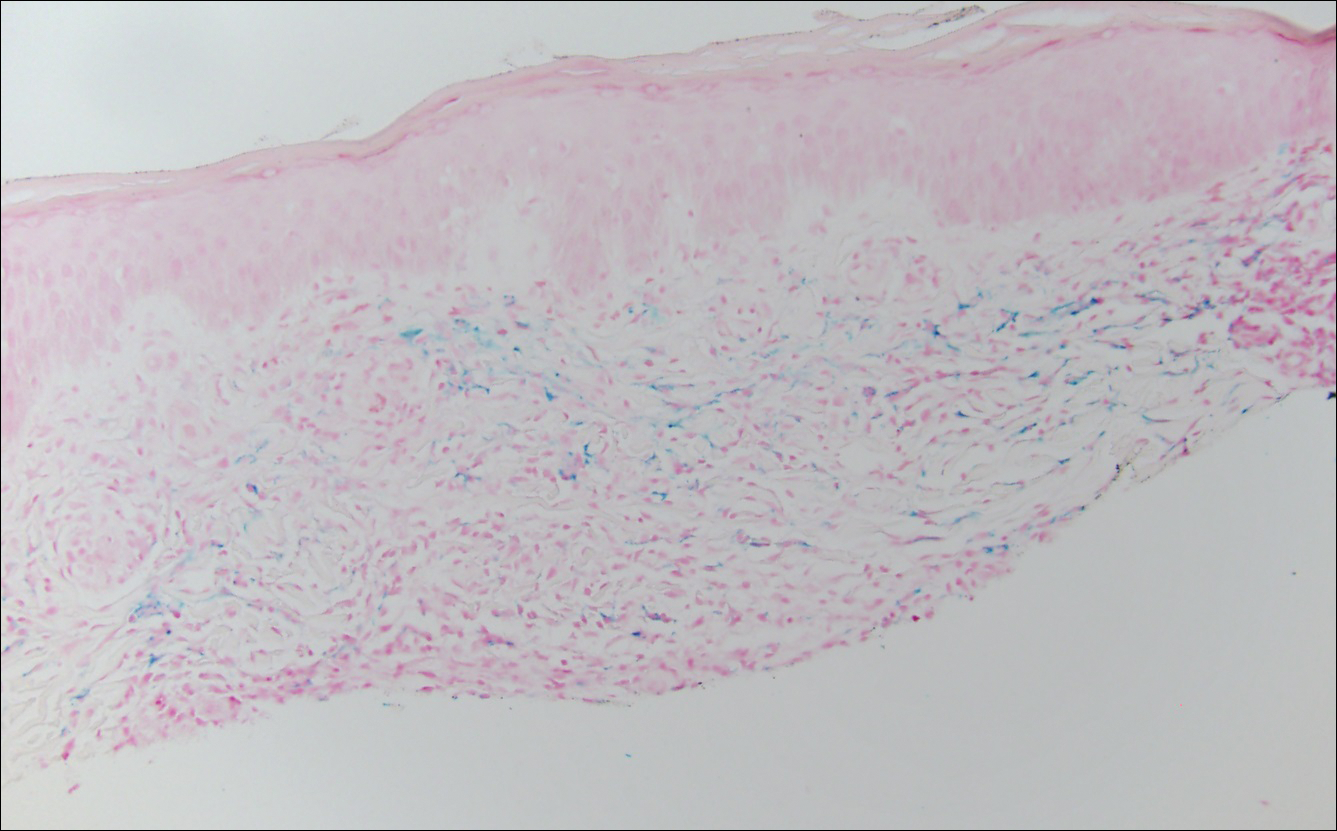

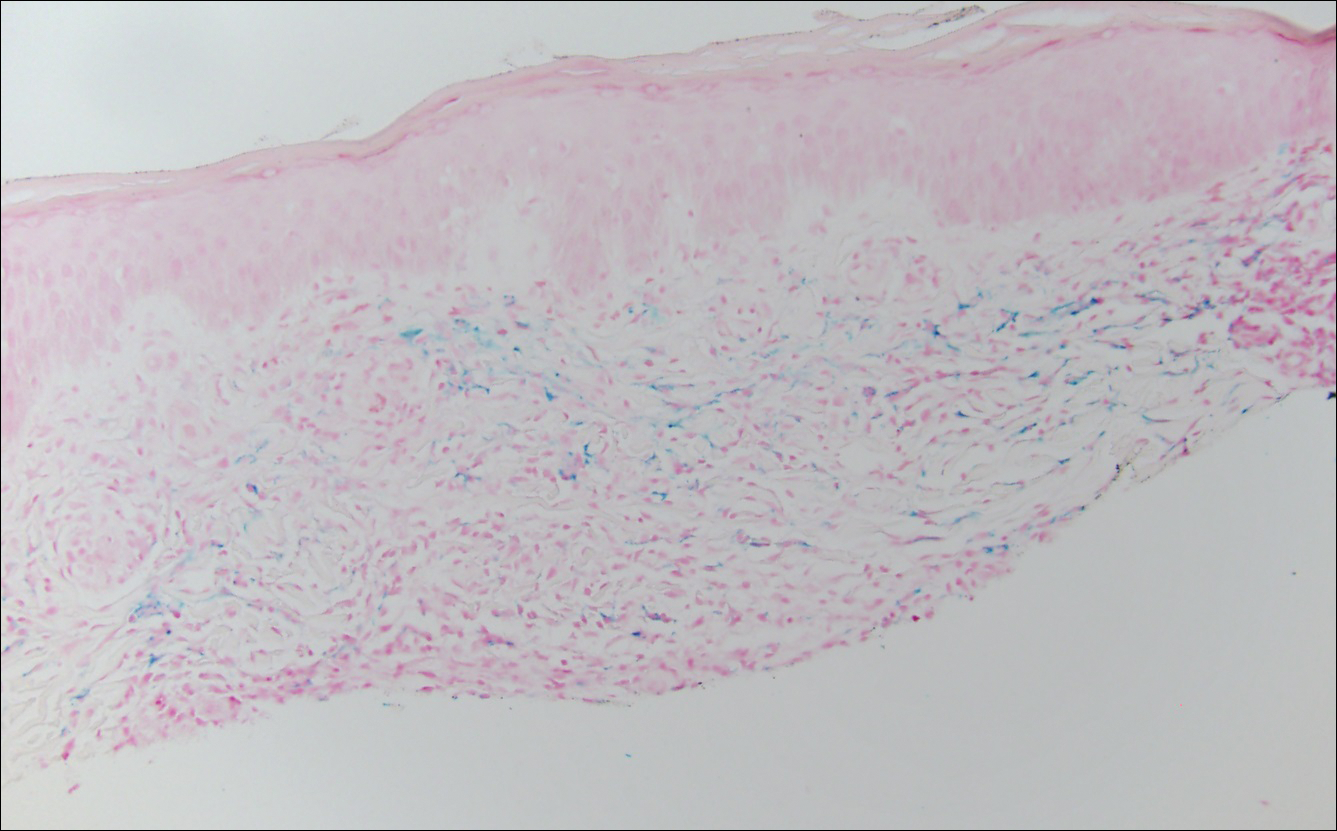

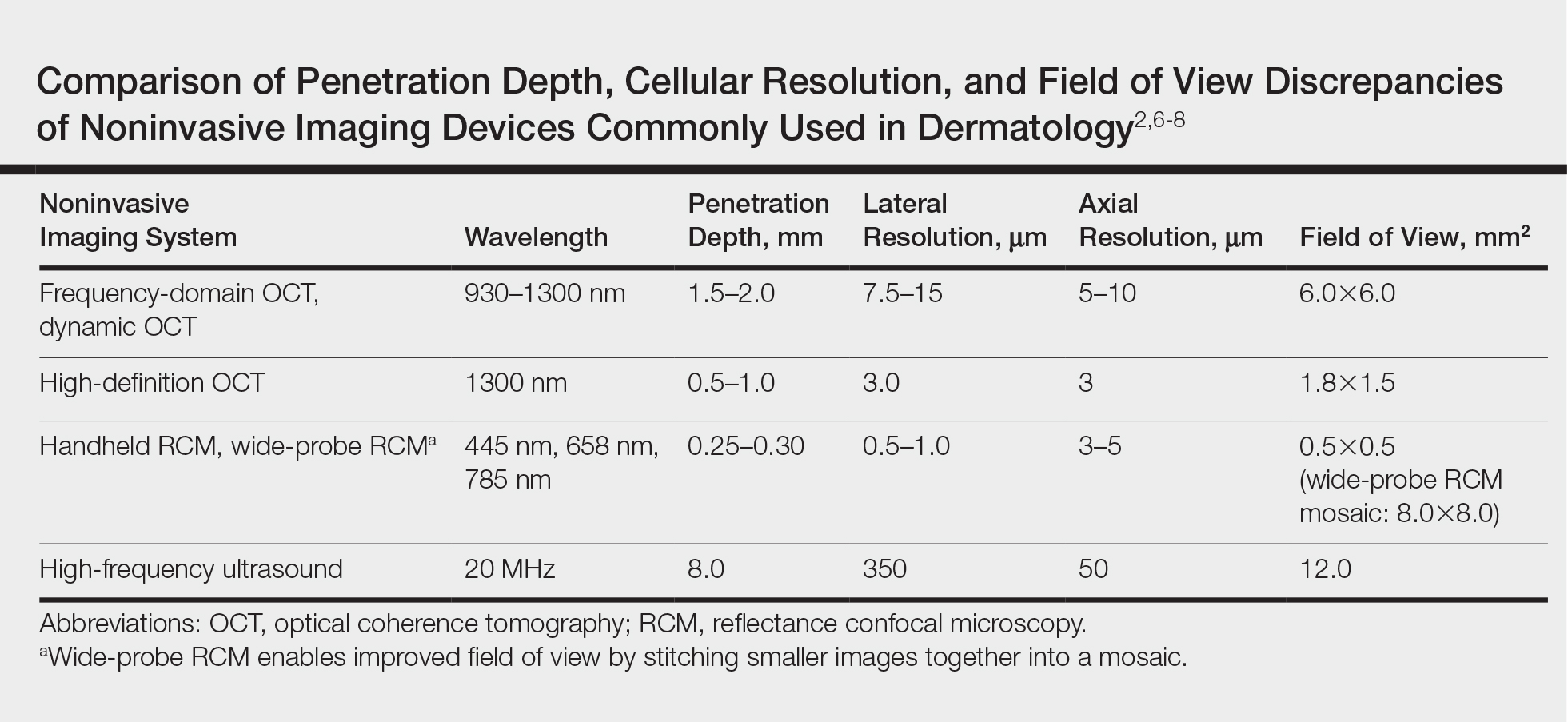

The clinicopathological findings were diagnostic of lichen aureus (LA). Microscopic examination revealed a relatively sparse, superficial, perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered siderophages in the upper dermis. Extravasation of red blood cells also was noted (Figure 1). An immunohistochemical stain for Melan-A highlighted a normal number and distribution of single melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction with no evidence of pagetoid scatter. A Perls Prussian blue stain for iron demonstrated abundant hemosiderin in the dermis (Figure 2).

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD) describes a group of cutaneous lesions that are characterized by petechiae and pigmentary changes. These lesions most commonly present on the lower limbs; however, other sites have been reported.1 This group includes several major clinical forms such as Schamberg disease, LA, purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis, and lichenoid PPD of Gougerot and Blum. Lesions typically demonstrate a striking golden brown color clinically and by definition occur in the absence of platelet defects or vasculitis.1

Factors implicated in the pathogenesis of pigmented purpura include gravitational dependency, venous stasis, infection, and drugs.2 It is suggested that cellular immunity may play a role in the development of the disease based on the presence of CD4+ T lymphocytes in the infiltrate and the expression of HLA-DR by these lymphocytes and the keratinocytes.3 Lichen aureus differs in that it relates to increased intravascular pressure from an incompetent valve in an underlying perforating vein.4

Lichen aureus, also referred to as lichen purpuricus, is one major variant of PPD. The name reflects both the characteristic golden brown color and the histopathologic pattern of inflammation.1 Lichen aureus usually presents as a unilateral, asymptomatic, confined single lesion located mainly on the leg,1 though it can develop at other sites or as a localized group of lesions. Extensive lesions have been reported5 and cases with a segmental distribution have been described.6 In contrast, Schamberg disease demonstrates pinhead-sized reddish lesions giving the characteristic cayenne pepper pigmentation. These lesions coalesce to form thumbprint patches that progress proximally.1 Majocchi purpura is annular and telangiectatic, while lichenoid purpura of Gougerot and Blum presents with flat-topped, polygonal, violaceous papules that turn brown over time.

Some authors have championed a role for dermoscopy in diagnosis of LA.7 By dermoscopy, LA demonstrates a diffuse copper background reflecting the lymphohistiocytic dermal infiltrate, red dots and globules representing the extravasated red blood cells and the dilated swollen vessels, and grey dots that reflect the hemosiderin present in the dermis.8

Histologically, LA demonstrates a superficial perivascular infiltrate composed mainly of CD4+ lymphocytes surrounding the superficial capillaries. Over time, red cell extravasation leads to the formation of hemosiderin-laden macrophages, which can be highlighted with Perls Prussian blue stain. A bandlike infiltrate with thin strands of collagen separating it from the epidermis also may be noted.9

An important consideration in the differential diagnosis of PPD is mycosis fungoides (MF). Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that clinically presents as a single or multiple hypopigmented or hyperpigmented patches or as erythematous scaly lesions in the patch or plaque stage. These lesions eventually may evolve into tumor stage.10 Mycosis fungoides may mimic PPD clinically and/or histopathologically, and rarely PPD also may precede MF.11 Involvement of the trunk, especially the lower abdomen and buttock region, favors a diagnosis of MF. Typically, histopathologic examination of MF demonstrates an epidermotropic lymphocytic infiltrate composed of atypical cerebriform lymphocytes overlying papillary dermal fibrosis. Although classic MF would be difficult to confuse with PPD, the atrophic lichenoid pattern of MF may show remarkable overlap with PPD.12 Such cases require clinicopathologic correlation, immunophenotyping of the epidermotropic lymphocytes, and occasionally T-cell clonality studies.

Lichen aureus is a chronic persistent disease unless the underlying incompetent perforator vessel is ligated. Various treatments have been used for other forms of pigmented purpura including topical corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, systemic vasodilators such as prostacyclin and pentoxifylline, and phototherapy.1 Clinical follow-up is recommended for lesions that show some clinical or histopathological overlap with MF. Additional biopsies also may prove useful in establishing a definitive diagnosis in ambiguous cases.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Aiba S, Tagami H. Immunohistologic studies in Schamberg's disease. evidence for cellular immune reaction in lesional skin. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1058-1062.

- English J. Lichen aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(2, pt 1):377-379.

- Duhra P, Tan CY. Lichen aureus. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:395.

- Moche J, Glassman S, Modi D, et al. Segmental lichen aureus: a report of two cases treated with methylprednisolone aceponate. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:E15-E18.

- Zaballos P, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of pigmented purpuric dermatoses (lichen aureus): a useful tool for clinical diagnosis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1290-1291.

- Portela PS, Melo DF, Ormiga P, et al. Dermoscopy of lichen aureus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:253-255.

- Smoller BR, Kamel OW. Pigmented purpuric eruptions: immunopathologic studies supportive of a common immunophenotype. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:423-427.

- Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. a progress report. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111(1 suppl 1):S8-S12.

- Hanna S, Walsh N, D'Intino Y, et al. Mycosis fungoides presenting as pigmented purpuric dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:350-354.

- Toro JR, Sander CA, LeBoit PE. Persistent pigmented purpuric dermatitis and mycosis fungoides: simulant, precursor, or both? a study by light microscopy and molecular methods. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:108-118.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Aureus

The clinicopathological findings were diagnostic of lichen aureus (LA). Microscopic examination revealed a relatively sparse, superficial, perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered siderophages in the upper dermis. Extravasation of red blood cells also was noted (Figure 1). An immunohistochemical stain for Melan-A highlighted a normal number and distribution of single melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction with no evidence of pagetoid scatter. A Perls Prussian blue stain for iron demonstrated abundant hemosiderin in the dermis (Figure 2).

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD) describes a group of cutaneous lesions that are characterized by petechiae and pigmentary changes. These lesions most commonly present on the lower limbs; however, other sites have been reported.1 This group includes several major clinical forms such as Schamberg disease, LA, purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis, and lichenoid PPD of Gougerot and Blum. Lesions typically demonstrate a striking golden brown color clinically and by definition occur in the absence of platelet defects or vasculitis.1

Factors implicated in the pathogenesis of pigmented purpura include gravitational dependency, venous stasis, infection, and drugs.2 It is suggested that cellular immunity may play a role in the development of the disease based on the presence of CD4+ T lymphocytes in the infiltrate and the expression of HLA-DR by these lymphocytes and the keratinocytes.3 Lichen aureus differs in that it relates to increased intravascular pressure from an incompetent valve in an underlying perforating vein.4

Lichen aureus, also referred to as lichen purpuricus, is one major variant of PPD. The name reflects both the characteristic golden brown color and the histopathologic pattern of inflammation.1 Lichen aureus usually presents as a unilateral, asymptomatic, confined single lesion located mainly on the leg,1 though it can develop at other sites or as a localized group of lesions. Extensive lesions have been reported5 and cases with a segmental distribution have been described.6 In contrast, Schamberg disease demonstrates pinhead-sized reddish lesions giving the characteristic cayenne pepper pigmentation. These lesions coalesce to form thumbprint patches that progress proximally.1 Majocchi purpura is annular and telangiectatic, while lichenoid purpura of Gougerot and Blum presents with flat-topped, polygonal, violaceous papules that turn brown over time.

Some authors have championed a role for dermoscopy in diagnosis of LA.7 By dermoscopy, LA demonstrates a diffuse copper background reflecting the lymphohistiocytic dermal infiltrate, red dots and globules representing the extravasated red blood cells and the dilated swollen vessels, and grey dots that reflect the hemosiderin present in the dermis.8

Histologically, LA demonstrates a superficial perivascular infiltrate composed mainly of CD4+ lymphocytes surrounding the superficial capillaries. Over time, red cell extravasation leads to the formation of hemosiderin-laden macrophages, which can be highlighted with Perls Prussian blue stain. A bandlike infiltrate with thin strands of collagen separating it from the epidermis also may be noted.9

An important consideration in the differential diagnosis of PPD is mycosis fungoides (MF). Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that clinically presents as a single or multiple hypopigmented or hyperpigmented patches or as erythematous scaly lesions in the patch or plaque stage. These lesions eventually may evolve into tumor stage.10 Mycosis fungoides may mimic PPD clinically and/or histopathologically, and rarely PPD also may precede MF.11 Involvement of the trunk, especially the lower abdomen and buttock region, favors a diagnosis of MF. Typically, histopathologic examination of MF demonstrates an epidermotropic lymphocytic infiltrate composed of atypical cerebriform lymphocytes overlying papillary dermal fibrosis. Although classic MF would be difficult to confuse with PPD, the atrophic lichenoid pattern of MF may show remarkable overlap with PPD.12 Such cases require clinicopathologic correlation, immunophenotyping of the epidermotropic lymphocytes, and occasionally T-cell clonality studies.

Lichen aureus is a chronic persistent disease unless the underlying incompetent perforator vessel is ligated. Various treatments have been used for other forms of pigmented purpura including topical corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, systemic vasodilators such as prostacyclin and pentoxifylline, and phototherapy.1 Clinical follow-up is recommended for lesions that show some clinical or histopathological overlap with MF. Additional biopsies also may prove useful in establishing a definitive diagnosis in ambiguous cases.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Aureus

The clinicopathological findings were diagnostic of lichen aureus (LA). Microscopic examination revealed a relatively sparse, superficial, perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered siderophages in the upper dermis. Extravasation of red blood cells also was noted (Figure 1). An immunohistochemical stain for Melan-A highlighted a normal number and distribution of single melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction with no evidence of pagetoid scatter. A Perls Prussian blue stain for iron demonstrated abundant hemosiderin in the dermis (Figure 2).