User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

What’s Eating You? Ixodes Tick and Related Diseases, Part 3: Coinfection and Tick-Bite Prevention

Tick-borne diseases are increasing in prevalence, likely due to climate change in combination with human movement into tick habitats.1-3 The Ixodes genus of hard ticks is a common vector for the transmission of pathogenic viruses, bacteria, parasites, and toxins. Among these, Lyme disease, which is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, is the most prevalent, followed by babesiosis and human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA), respectively.4 In Europe, tick-borne encephalitis is commonly encountered. More recently identified diseases transmitted by Ixodes ticks include Powassan virus and Borrelia miyamotoi infection; however, these diseases are less frequently encountered than other tick-borne diseases.5,6

As tick-borne diseases become more prevalent, the likelihood of coinfection with more than one Ixodes-transmitted pathogen is increasing.7 Therefore, it is important for physicians who practice in endemic areas to be aware of the possibility of coinfection, which can alter clinical presentation, disease severity, and treatment response in tick-borne diseases. Additionally, public education on tick-bite prevention and prompt tick removal is necessary to combat the rising prevalence of these diseases.

Coinfection

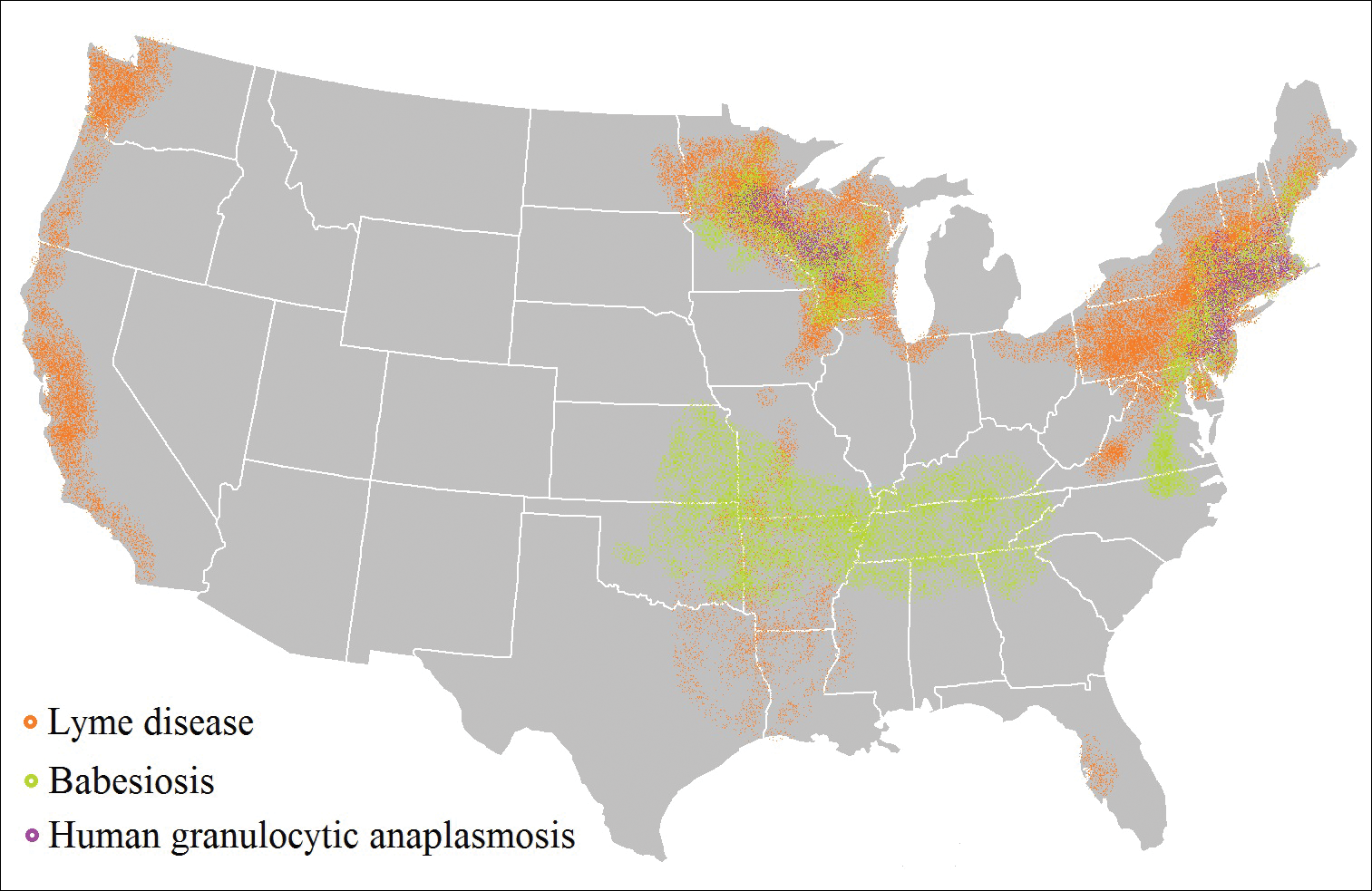

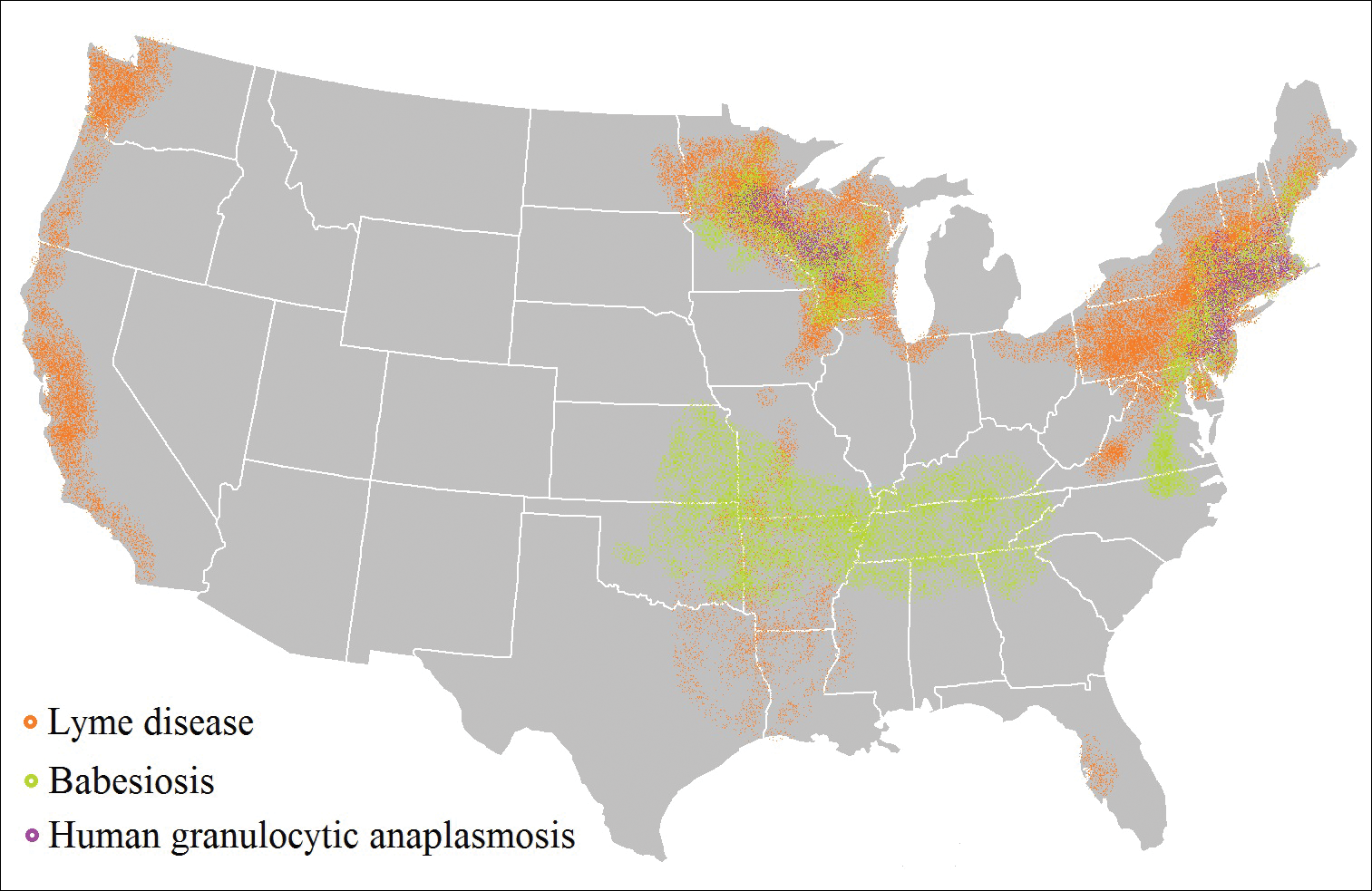

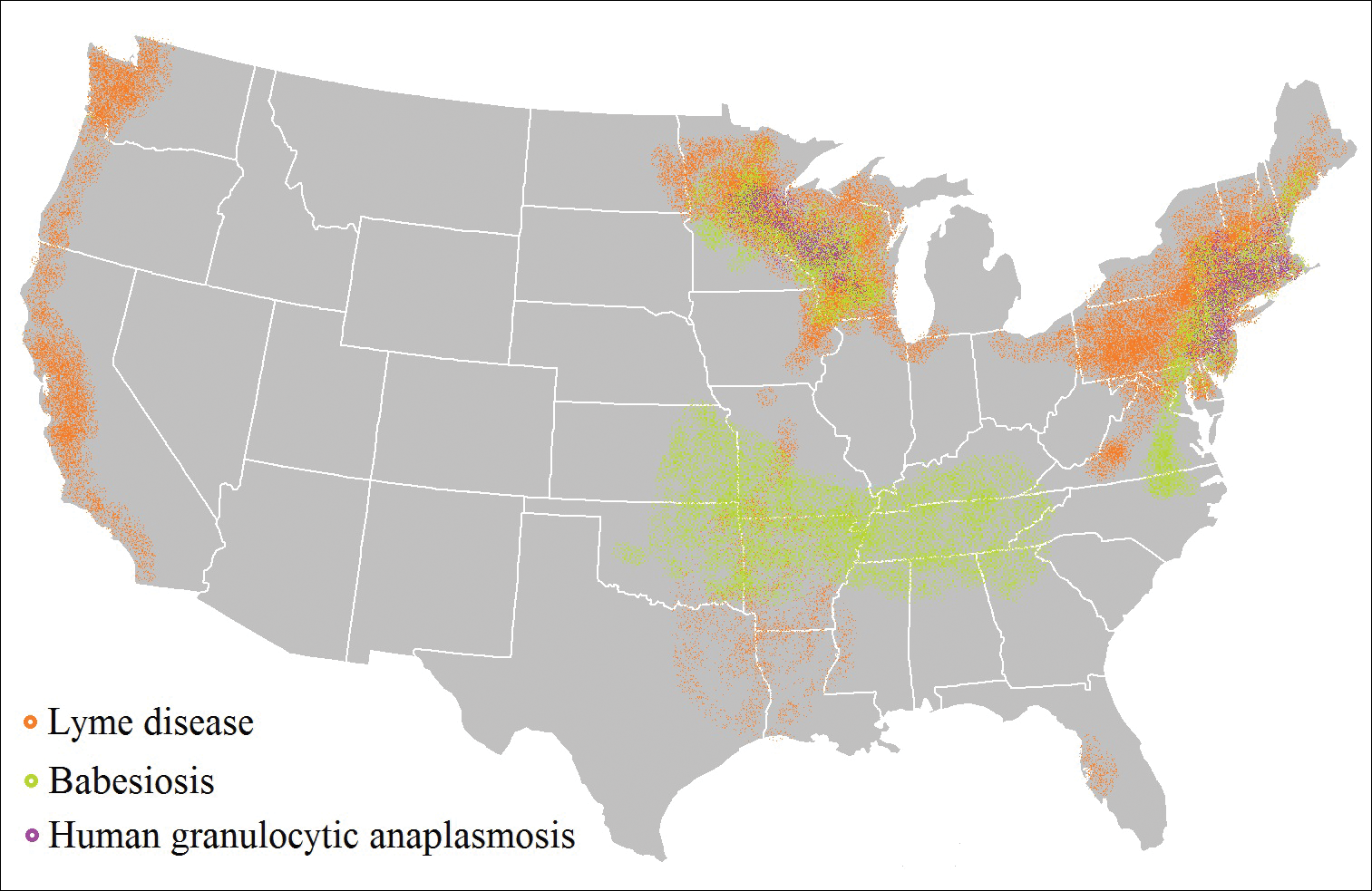

Risk of coinfection with more than one tick-borne disease is contingent on the geographic distribution of the tick species as well as the particular pathogen’s prevalence within reservoir hosts in a given area (Figure). Most coinfections occur with B. burgdorferi and an additional pathogen, usually Anaplasma phagocytophilum (which causes human granulocytic anaplasmosis [HGA]) or Babesia microti (which causes babesiosis). In Europe, coinfection with tick-borne encephalitis virus may occur. There is limited evidence of human coinfection with B miyamotoi or Powassan virus, as isolated infection with either of these pathogens is rare.

In patients with Lyme disease, as many as 35% may have concurrent babesiosis, and as many as 12% may have concurrent HGA in endemic areas (eg, northeast and northern central United States).7-9 Concurrent HGA and babesiosis in the absence of Lyme disease also has been documented.7-9 Coinfection generally increases the diversity of presenting symptoms, often obscuring the primary diagnosis. In addition, these patients may have more severe and prolonged illness.8,10,11

In endemic areas, coinfection with B burgdorferi and an additional pathogen should be suspected if a patient presents with typical symptoms of early Lyme disease, especially erythema migrans, along with (1) combination of fever, chills, and headache; (2) prolonged viral-like illness, particularly 48 hours after appropriate antibiotic treatment; and (3) unexplained blood dyscrasia.7,11,12 When a patient presents with erythema migrans, it is unnecessary to test for HGA, as treatment of Lyme disease with doxycycline also is adequate for treating HGA; however, if systemic symptoms persist despite treatment, testing for babesiosis and other tick-borne illnesses should be considered, as babesiosis requires treatment with atovaquone plus azithromycin or clindamycin plus quinine.13

A complete blood count and peripheral blood smear can aid in the diagnosis of coinfection. The complete blood count may reveal leukopenia, anemia, or thrombocytopenia associated with HGA or babesiosis. The peripheral blood smear can reveal inclusions of intra-erythrocytic ring forms and tetrads (the “Maltese cross” appearance) in babesiosis and intragranulocytic morulae in HGA.12 The most sensitive diagnostic tests for tick-borne diseases are organism-specific IgM and IgG serology for Lyme disease, babesiosis, and HGA and polymerase chain reaction for babesiosis and HGA.7

Prevention Strategies

The most effective means of controlling tick-borne disease is avoiding tick bites altogether. One method is to avoid spending time in high-risk areas that may be infested with ticks, particularly low-lying brush, where ticks are likely to hide.14 For individuals traveling in environments with a high risk of tick exposure, behavioral methods of avoidance are indicated, including wearing long pants and a shirt with long sleeves, tucking the shirt into the pants, and wearing closed-toe shoes. Wearing light-colored clothing may aid in tick identification and prompt removal prior to attachment. Permethrin-impregnated clothing has been proven to decrease the likelihood of tick bites in adults working outdoors.15-17

Topical repellents also play a role in the prevention of tick-borne diseases. The most effective and safe synthetic repellents are N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET); picaridin; p-menthane-3,8-diol; and insect repellent 3535 (IR3535)(ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate).16-19 Plant-based repellents also are available, but their efficacy is strongly influenced by the surrounding environment (eg, temperature, humidity, organic matter).20-22 Individuals also may be exposed to ticks following contact with domesticated animals and pets.23,24 Tick prevention in pets with the use of ectoparasiticides should be directed by a qualified veterinarian.25

Tick Removal

Following a bite, the tick should be removed promptly to avoid transmission of pathogens. Numerous commercial and in-home methods of tick removal are available, but not all are equally effective. Detachment techniques include removal with a card or commercially available radiofrequency device, lassoing, or freezing.26,27 However, the most effective method is simple removal with tweezers. The tick should be grasped close to the skin surface and pulled upward with an even pressure. Commercially available tick-removal devices have not been shown to produce better outcomes than removal of the tick with tweezers.28

Conclusion

When patients do not respond to therapy for presumed tick-borne infection, the diagnosis should be reconsidered. One important consideration is coinfection with a second organism. Prompt identification and removal of ticks can prevent disease transmission.

- McMichael C, Barnett J, McMichael AJ. An ill wind? climate change, migration, and health. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:646-654.

- Ostfeld RS, Brunner JL. Climate change and Ixodes tick-borne diseases of humans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370:20140051.

- Ogden NH, Bigras-Poulin M, O’Callaghan CJ, et al. Vector seasonality, host infection dynamics and fitness of pathogens transmitted by the tick Ixodes scapularis. Parasitology. 2007;134(pt 2):209-227.

- Tickborne diseases of the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/ticks/diseases/index.html. Updated July 25, 2017. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Hinten SR, Beckett GA, Gensheimer KF, et al. Increased recognition of Powassan encephalitis in the United States, 1999-2005. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:733-740.

- Platonov AE, Karan LS, Kolyasnikova NM, et al. Humans infected with relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia miyamotoi, Russia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1816-1823.

- Krause PJ, McKay K, Thompson CA, et al; Deer-Associated Infection Study Group. Disease-specific diagnosis of coinfecting tickborne zoonoses: babesiosis, human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, and Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1184-1191.

- Krause PJ, Telford SR 3rd, Spielman A, et al. Concurrent Lyme disease and babesiosis. evidence for increased severity and duration of illness. JAMA. 1996;275:1657-1660.

- Belongia EA, Reed KD, Mitchell PD, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of early Lyme disease and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Wisconsin. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1472-1477.

- Sweeny CJ, Ghassemi M, Agger WA, et al. Coinfection with Babesia microti and Borrelia burgdorferi in a western Wisconsin resident. Mayo Clin Proc.1998;73:338-341.

- Nadelman RB, Horowitz HW, Hsieh TC, et al. Simultaneous human granulocytic ehrlichiosis and Lyme borreliosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:27-30.

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1089-1134.

- Swanson SJ, Neitzel D, Reed DK, et al. Coinfections acquired from Ixodes ticks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:708-727.

- Hayes EB, Piesman J. How can we prevent Lyme disease? N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2424-2430.

- Vaughn MF, Funkhouser SW, Lin FC, et al. Long-lasting permethrin impregnated uniforms: a randomized-controlled trial for tick bite prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:473-480.

- Miller NJ, Rainone EE, Dyer MC, et al. Tick bite protection with permethrin-treated summer-weight clothing. J Med Entomol. 2011;48:327-333.

- Richards SL, Balanay JAG, Harris JW. Effectiveness of permethrin-treated clothing to prevent tick exposure in foresters in the central Appalachian region of the USA. Int J Environ Health Res. 2015;25:453-462.

- Pages F, Dautel H, Duvallet G, et al. Tick repellents for human use: prevention of tick bites and tick-borne diseases. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14:85-93.

- Büchel K, Bendin J, Gharbi A, et al. Repellent efficacy of DEET, icaridin, and EBAAP against Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes scapularis nymphs (Acari, Ixodidae). Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015;6:494-498.

- Schwantes U, Dautel H, Jung G. Prevention of infectious tick-borne diseases in humans: comparative studies of the repellency of different dodecanoic acid-formulations against Ixodes ricinus ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). Parasit Vectors. 2008;8:1-8.

- Bissinger BW, Apperson CS, Sonenshine DE, et al. Efficacy of the new repellent BioUD against three species of ixodid ticks. Exp Appl Acarol. 2009;48:239-250.

- Feaster JE, Scialdone MA, Todd RG, et al. Dihydronepetalactones deter feeding activity by mosquitoes, stable flies, and deer ticks. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:832-840.

- Jennett AL, Smith FD, Wall R. Tick infestation risk for dogs in a peri-urban park. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:358.

- Rand PW, Smith RP Jr, Lacombe EH. Canine seroprevalence and the distribution of Ixodes dammini in an area of emerging Lyme disease. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:1331-1334.

- Baneth G, Bourdeau P, Bourdoiseau G, et al; CVBD World Forum. Vector-borne diseases—constant challenge for practicing veterinarians: recommendations from the CVBD World Forum. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:55.

- Akin Belli A, Dervis E, Kar S, et al. Revisiting detachment techniques in human-biting ticks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:393-397.

- Ashique KT, Kaliyadan F. Radiofrequency device for tick removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:155-156.

- Due C, Fox W, Medlock JM, et al. Tick bite prevention and tick removal. BMJ. 2013;347:f7123.

Tick-borne diseases are increasing in prevalence, likely due to climate change in combination with human movement into tick habitats.1-3 The Ixodes genus of hard ticks is a common vector for the transmission of pathogenic viruses, bacteria, parasites, and toxins. Among these, Lyme disease, which is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, is the most prevalent, followed by babesiosis and human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA), respectively.4 In Europe, tick-borne encephalitis is commonly encountered. More recently identified diseases transmitted by Ixodes ticks include Powassan virus and Borrelia miyamotoi infection; however, these diseases are less frequently encountered than other tick-borne diseases.5,6

As tick-borne diseases become more prevalent, the likelihood of coinfection with more than one Ixodes-transmitted pathogen is increasing.7 Therefore, it is important for physicians who practice in endemic areas to be aware of the possibility of coinfection, which can alter clinical presentation, disease severity, and treatment response in tick-borne diseases. Additionally, public education on tick-bite prevention and prompt tick removal is necessary to combat the rising prevalence of these diseases.

Coinfection

Risk of coinfection with more than one tick-borne disease is contingent on the geographic distribution of the tick species as well as the particular pathogen’s prevalence within reservoir hosts in a given area (Figure). Most coinfections occur with B. burgdorferi and an additional pathogen, usually Anaplasma phagocytophilum (which causes human granulocytic anaplasmosis [HGA]) or Babesia microti (which causes babesiosis). In Europe, coinfection with tick-borne encephalitis virus may occur. There is limited evidence of human coinfection with B miyamotoi or Powassan virus, as isolated infection with either of these pathogens is rare.

In patients with Lyme disease, as many as 35% may have concurrent babesiosis, and as many as 12% may have concurrent HGA in endemic areas (eg, northeast and northern central United States).7-9 Concurrent HGA and babesiosis in the absence of Lyme disease also has been documented.7-9 Coinfection generally increases the diversity of presenting symptoms, often obscuring the primary diagnosis. In addition, these patients may have more severe and prolonged illness.8,10,11

In endemic areas, coinfection with B burgdorferi and an additional pathogen should be suspected if a patient presents with typical symptoms of early Lyme disease, especially erythema migrans, along with (1) combination of fever, chills, and headache; (2) prolonged viral-like illness, particularly 48 hours after appropriate antibiotic treatment; and (3) unexplained blood dyscrasia.7,11,12 When a patient presents with erythema migrans, it is unnecessary to test for HGA, as treatment of Lyme disease with doxycycline also is adequate for treating HGA; however, if systemic symptoms persist despite treatment, testing for babesiosis and other tick-borne illnesses should be considered, as babesiosis requires treatment with atovaquone plus azithromycin or clindamycin plus quinine.13

A complete blood count and peripheral blood smear can aid in the diagnosis of coinfection. The complete blood count may reveal leukopenia, anemia, or thrombocytopenia associated with HGA or babesiosis. The peripheral blood smear can reveal inclusions of intra-erythrocytic ring forms and tetrads (the “Maltese cross” appearance) in babesiosis and intragranulocytic morulae in HGA.12 The most sensitive diagnostic tests for tick-borne diseases are organism-specific IgM and IgG serology for Lyme disease, babesiosis, and HGA and polymerase chain reaction for babesiosis and HGA.7

Prevention Strategies

The most effective means of controlling tick-borne disease is avoiding tick bites altogether. One method is to avoid spending time in high-risk areas that may be infested with ticks, particularly low-lying brush, where ticks are likely to hide.14 For individuals traveling in environments with a high risk of tick exposure, behavioral methods of avoidance are indicated, including wearing long pants and a shirt with long sleeves, tucking the shirt into the pants, and wearing closed-toe shoes. Wearing light-colored clothing may aid in tick identification and prompt removal prior to attachment. Permethrin-impregnated clothing has been proven to decrease the likelihood of tick bites in adults working outdoors.15-17

Topical repellents also play a role in the prevention of tick-borne diseases. The most effective and safe synthetic repellents are N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET); picaridin; p-menthane-3,8-diol; and insect repellent 3535 (IR3535)(ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate).16-19 Plant-based repellents also are available, but their efficacy is strongly influenced by the surrounding environment (eg, temperature, humidity, organic matter).20-22 Individuals also may be exposed to ticks following contact with domesticated animals and pets.23,24 Tick prevention in pets with the use of ectoparasiticides should be directed by a qualified veterinarian.25

Tick Removal

Following a bite, the tick should be removed promptly to avoid transmission of pathogens. Numerous commercial and in-home methods of tick removal are available, but not all are equally effective. Detachment techniques include removal with a card or commercially available radiofrequency device, lassoing, or freezing.26,27 However, the most effective method is simple removal with tweezers. The tick should be grasped close to the skin surface and pulled upward with an even pressure. Commercially available tick-removal devices have not been shown to produce better outcomes than removal of the tick with tweezers.28

Conclusion

When patients do not respond to therapy for presumed tick-borne infection, the diagnosis should be reconsidered. One important consideration is coinfection with a second organism. Prompt identification and removal of ticks can prevent disease transmission.

Tick-borne diseases are increasing in prevalence, likely due to climate change in combination with human movement into tick habitats.1-3 The Ixodes genus of hard ticks is a common vector for the transmission of pathogenic viruses, bacteria, parasites, and toxins. Among these, Lyme disease, which is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, is the most prevalent, followed by babesiosis and human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA), respectively.4 In Europe, tick-borne encephalitis is commonly encountered. More recently identified diseases transmitted by Ixodes ticks include Powassan virus and Borrelia miyamotoi infection; however, these diseases are less frequently encountered than other tick-borne diseases.5,6

As tick-borne diseases become more prevalent, the likelihood of coinfection with more than one Ixodes-transmitted pathogen is increasing.7 Therefore, it is important for physicians who practice in endemic areas to be aware of the possibility of coinfection, which can alter clinical presentation, disease severity, and treatment response in tick-borne diseases. Additionally, public education on tick-bite prevention and prompt tick removal is necessary to combat the rising prevalence of these diseases.

Coinfection

Risk of coinfection with more than one tick-borne disease is contingent on the geographic distribution of the tick species as well as the particular pathogen’s prevalence within reservoir hosts in a given area (Figure). Most coinfections occur with B. burgdorferi and an additional pathogen, usually Anaplasma phagocytophilum (which causes human granulocytic anaplasmosis [HGA]) or Babesia microti (which causes babesiosis). In Europe, coinfection with tick-borne encephalitis virus may occur. There is limited evidence of human coinfection with B miyamotoi or Powassan virus, as isolated infection with either of these pathogens is rare.

In patients with Lyme disease, as many as 35% may have concurrent babesiosis, and as many as 12% may have concurrent HGA in endemic areas (eg, northeast and northern central United States).7-9 Concurrent HGA and babesiosis in the absence of Lyme disease also has been documented.7-9 Coinfection generally increases the diversity of presenting symptoms, often obscuring the primary diagnosis. In addition, these patients may have more severe and prolonged illness.8,10,11

In endemic areas, coinfection with B burgdorferi and an additional pathogen should be suspected if a patient presents with typical symptoms of early Lyme disease, especially erythema migrans, along with (1) combination of fever, chills, and headache; (2) prolonged viral-like illness, particularly 48 hours after appropriate antibiotic treatment; and (3) unexplained blood dyscrasia.7,11,12 When a patient presents with erythema migrans, it is unnecessary to test for HGA, as treatment of Lyme disease with doxycycline also is adequate for treating HGA; however, if systemic symptoms persist despite treatment, testing for babesiosis and other tick-borne illnesses should be considered, as babesiosis requires treatment with atovaquone plus azithromycin or clindamycin plus quinine.13

A complete blood count and peripheral blood smear can aid in the diagnosis of coinfection. The complete blood count may reveal leukopenia, anemia, or thrombocytopenia associated with HGA or babesiosis. The peripheral blood smear can reveal inclusions of intra-erythrocytic ring forms and tetrads (the “Maltese cross” appearance) in babesiosis and intragranulocytic morulae in HGA.12 The most sensitive diagnostic tests for tick-borne diseases are organism-specific IgM and IgG serology for Lyme disease, babesiosis, and HGA and polymerase chain reaction for babesiosis and HGA.7

Prevention Strategies

The most effective means of controlling tick-borne disease is avoiding tick bites altogether. One method is to avoid spending time in high-risk areas that may be infested with ticks, particularly low-lying brush, where ticks are likely to hide.14 For individuals traveling in environments with a high risk of tick exposure, behavioral methods of avoidance are indicated, including wearing long pants and a shirt with long sleeves, tucking the shirt into the pants, and wearing closed-toe shoes. Wearing light-colored clothing may aid in tick identification and prompt removal prior to attachment. Permethrin-impregnated clothing has been proven to decrease the likelihood of tick bites in adults working outdoors.15-17

Topical repellents also play a role in the prevention of tick-borne diseases. The most effective and safe synthetic repellents are N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET); picaridin; p-menthane-3,8-diol; and insect repellent 3535 (IR3535)(ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate).16-19 Plant-based repellents also are available, but their efficacy is strongly influenced by the surrounding environment (eg, temperature, humidity, organic matter).20-22 Individuals also may be exposed to ticks following contact with domesticated animals and pets.23,24 Tick prevention in pets with the use of ectoparasiticides should be directed by a qualified veterinarian.25

Tick Removal

Following a bite, the tick should be removed promptly to avoid transmission of pathogens. Numerous commercial and in-home methods of tick removal are available, but not all are equally effective. Detachment techniques include removal with a card or commercially available radiofrequency device, lassoing, or freezing.26,27 However, the most effective method is simple removal with tweezers. The tick should be grasped close to the skin surface and pulled upward with an even pressure. Commercially available tick-removal devices have not been shown to produce better outcomes than removal of the tick with tweezers.28

Conclusion

When patients do not respond to therapy for presumed tick-borne infection, the diagnosis should be reconsidered. One important consideration is coinfection with a second organism. Prompt identification and removal of ticks can prevent disease transmission.

- McMichael C, Barnett J, McMichael AJ. An ill wind? climate change, migration, and health. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:646-654.

- Ostfeld RS, Brunner JL. Climate change and Ixodes tick-borne diseases of humans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370:20140051.

- Ogden NH, Bigras-Poulin M, O’Callaghan CJ, et al. Vector seasonality, host infection dynamics and fitness of pathogens transmitted by the tick Ixodes scapularis. Parasitology. 2007;134(pt 2):209-227.

- Tickborne diseases of the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/ticks/diseases/index.html. Updated July 25, 2017. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Hinten SR, Beckett GA, Gensheimer KF, et al. Increased recognition of Powassan encephalitis in the United States, 1999-2005. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:733-740.

- Platonov AE, Karan LS, Kolyasnikova NM, et al. Humans infected with relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia miyamotoi, Russia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1816-1823.

- Krause PJ, McKay K, Thompson CA, et al; Deer-Associated Infection Study Group. Disease-specific diagnosis of coinfecting tickborne zoonoses: babesiosis, human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, and Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1184-1191.

- Krause PJ, Telford SR 3rd, Spielman A, et al. Concurrent Lyme disease and babesiosis. evidence for increased severity and duration of illness. JAMA. 1996;275:1657-1660.

- Belongia EA, Reed KD, Mitchell PD, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of early Lyme disease and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Wisconsin. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1472-1477.

- Sweeny CJ, Ghassemi M, Agger WA, et al. Coinfection with Babesia microti and Borrelia burgdorferi in a western Wisconsin resident. Mayo Clin Proc.1998;73:338-341.

- Nadelman RB, Horowitz HW, Hsieh TC, et al. Simultaneous human granulocytic ehrlichiosis and Lyme borreliosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:27-30.

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1089-1134.

- Swanson SJ, Neitzel D, Reed DK, et al. Coinfections acquired from Ixodes ticks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:708-727.

- Hayes EB, Piesman J. How can we prevent Lyme disease? N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2424-2430.

- Vaughn MF, Funkhouser SW, Lin FC, et al. Long-lasting permethrin impregnated uniforms: a randomized-controlled trial for tick bite prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:473-480.

- Miller NJ, Rainone EE, Dyer MC, et al. Tick bite protection with permethrin-treated summer-weight clothing. J Med Entomol. 2011;48:327-333.

- Richards SL, Balanay JAG, Harris JW. Effectiveness of permethrin-treated clothing to prevent tick exposure in foresters in the central Appalachian region of the USA. Int J Environ Health Res. 2015;25:453-462.

- Pages F, Dautel H, Duvallet G, et al. Tick repellents for human use: prevention of tick bites and tick-borne diseases. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14:85-93.

- Büchel K, Bendin J, Gharbi A, et al. Repellent efficacy of DEET, icaridin, and EBAAP against Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes scapularis nymphs (Acari, Ixodidae). Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015;6:494-498.

- Schwantes U, Dautel H, Jung G. Prevention of infectious tick-borne diseases in humans: comparative studies of the repellency of different dodecanoic acid-formulations against Ixodes ricinus ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). Parasit Vectors. 2008;8:1-8.

- Bissinger BW, Apperson CS, Sonenshine DE, et al. Efficacy of the new repellent BioUD against three species of ixodid ticks. Exp Appl Acarol. 2009;48:239-250.

- Feaster JE, Scialdone MA, Todd RG, et al. Dihydronepetalactones deter feeding activity by mosquitoes, stable flies, and deer ticks. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:832-840.

- Jennett AL, Smith FD, Wall R. Tick infestation risk for dogs in a peri-urban park. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:358.

- Rand PW, Smith RP Jr, Lacombe EH. Canine seroprevalence and the distribution of Ixodes dammini in an area of emerging Lyme disease. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:1331-1334.

- Baneth G, Bourdeau P, Bourdoiseau G, et al; CVBD World Forum. Vector-borne diseases—constant challenge for practicing veterinarians: recommendations from the CVBD World Forum. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:55.

- Akin Belli A, Dervis E, Kar S, et al. Revisiting detachment techniques in human-biting ticks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:393-397.

- Ashique KT, Kaliyadan F. Radiofrequency device for tick removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:155-156.

- Due C, Fox W, Medlock JM, et al. Tick bite prevention and tick removal. BMJ. 2013;347:f7123.

- McMichael C, Barnett J, McMichael AJ. An ill wind? climate change, migration, and health. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:646-654.

- Ostfeld RS, Brunner JL. Climate change and Ixodes tick-borne diseases of humans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370:20140051.

- Ogden NH, Bigras-Poulin M, O’Callaghan CJ, et al. Vector seasonality, host infection dynamics and fitness of pathogens transmitted by the tick Ixodes scapularis. Parasitology. 2007;134(pt 2):209-227.

- Tickborne diseases of the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/ticks/diseases/index.html. Updated July 25, 2017. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Hinten SR, Beckett GA, Gensheimer KF, et al. Increased recognition of Powassan encephalitis in the United States, 1999-2005. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:733-740.

- Platonov AE, Karan LS, Kolyasnikova NM, et al. Humans infected with relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia miyamotoi, Russia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1816-1823.

- Krause PJ, McKay K, Thompson CA, et al; Deer-Associated Infection Study Group. Disease-specific diagnosis of coinfecting tickborne zoonoses: babesiosis, human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, and Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1184-1191.

- Krause PJ, Telford SR 3rd, Spielman A, et al. Concurrent Lyme disease and babesiosis. evidence for increased severity and duration of illness. JAMA. 1996;275:1657-1660.

- Belongia EA, Reed KD, Mitchell PD, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of early Lyme disease and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Wisconsin. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1472-1477.

- Sweeny CJ, Ghassemi M, Agger WA, et al. Coinfection with Babesia microti and Borrelia burgdorferi in a western Wisconsin resident. Mayo Clin Proc.1998;73:338-341.

- Nadelman RB, Horowitz HW, Hsieh TC, et al. Simultaneous human granulocytic ehrlichiosis and Lyme borreliosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:27-30.

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1089-1134.

- Swanson SJ, Neitzel D, Reed DK, et al. Coinfections acquired from Ixodes ticks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:708-727.

- Hayes EB, Piesman J. How can we prevent Lyme disease? N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2424-2430.

- Vaughn MF, Funkhouser SW, Lin FC, et al. Long-lasting permethrin impregnated uniforms: a randomized-controlled trial for tick bite prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:473-480.

- Miller NJ, Rainone EE, Dyer MC, et al. Tick bite protection with permethrin-treated summer-weight clothing. J Med Entomol. 2011;48:327-333.

- Richards SL, Balanay JAG, Harris JW. Effectiveness of permethrin-treated clothing to prevent tick exposure in foresters in the central Appalachian region of the USA. Int J Environ Health Res. 2015;25:453-462.

- Pages F, Dautel H, Duvallet G, et al. Tick repellents for human use: prevention of tick bites and tick-borne diseases. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14:85-93.

- Büchel K, Bendin J, Gharbi A, et al. Repellent efficacy of DEET, icaridin, and EBAAP against Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes scapularis nymphs (Acari, Ixodidae). Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015;6:494-498.

- Schwantes U, Dautel H, Jung G. Prevention of infectious tick-borne diseases in humans: comparative studies of the repellency of different dodecanoic acid-formulations against Ixodes ricinus ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). Parasit Vectors. 2008;8:1-8.

- Bissinger BW, Apperson CS, Sonenshine DE, et al. Efficacy of the new repellent BioUD against three species of ixodid ticks. Exp Appl Acarol. 2009;48:239-250.

- Feaster JE, Scialdone MA, Todd RG, et al. Dihydronepetalactones deter feeding activity by mosquitoes, stable flies, and deer ticks. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:832-840.

- Jennett AL, Smith FD, Wall R. Tick infestation risk for dogs in a peri-urban park. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:358.

- Rand PW, Smith RP Jr, Lacombe EH. Canine seroprevalence and the distribution of Ixodes dammini in an area of emerging Lyme disease. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:1331-1334.

- Baneth G, Bourdeau P, Bourdoiseau G, et al; CVBD World Forum. Vector-borne diseases—constant challenge for practicing veterinarians: recommendations from the CVBD World Forum. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:55.

- Akin Belli A, Dervis E, Kar S, et al. Revisiting detachment techniques in human-biting ticks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:393-397.

- Ashique KT, Kaliyadan F. Radiofrequency device for tick removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:155-156.

- Due C, Fox W, Medlock JM, et al. Tick bite prevention and tick removal. BMJ. 2013;347:f7123.

Practice Points

- As tick-borne diseases become more prevalent, the likelihood of coinfection with more than one Ixodes-transmitted pathogen is increasing, particularly in endemic areas.

- Coinfection generally increases the diversity of presenting symptoms, obscuring the primary diagnosis. The disease course also may be prolonged and more severe.

- Prevention of tick attachment and prompt tick removal are critical to combating the rising prevalence of tick-borne diseases.

Painful Mouth Ulcers

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

A workup for infectious organisms and vasculitis was negative. The patient reported unintentional weight loss despite taking oral steroids prescribed by her pulmonologist for severe obstructive lung disease that appeared to develop around the same time as the mouth ulcers.

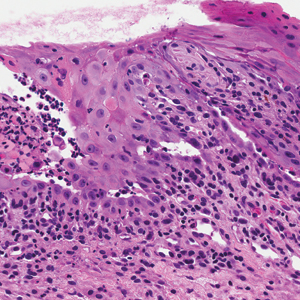

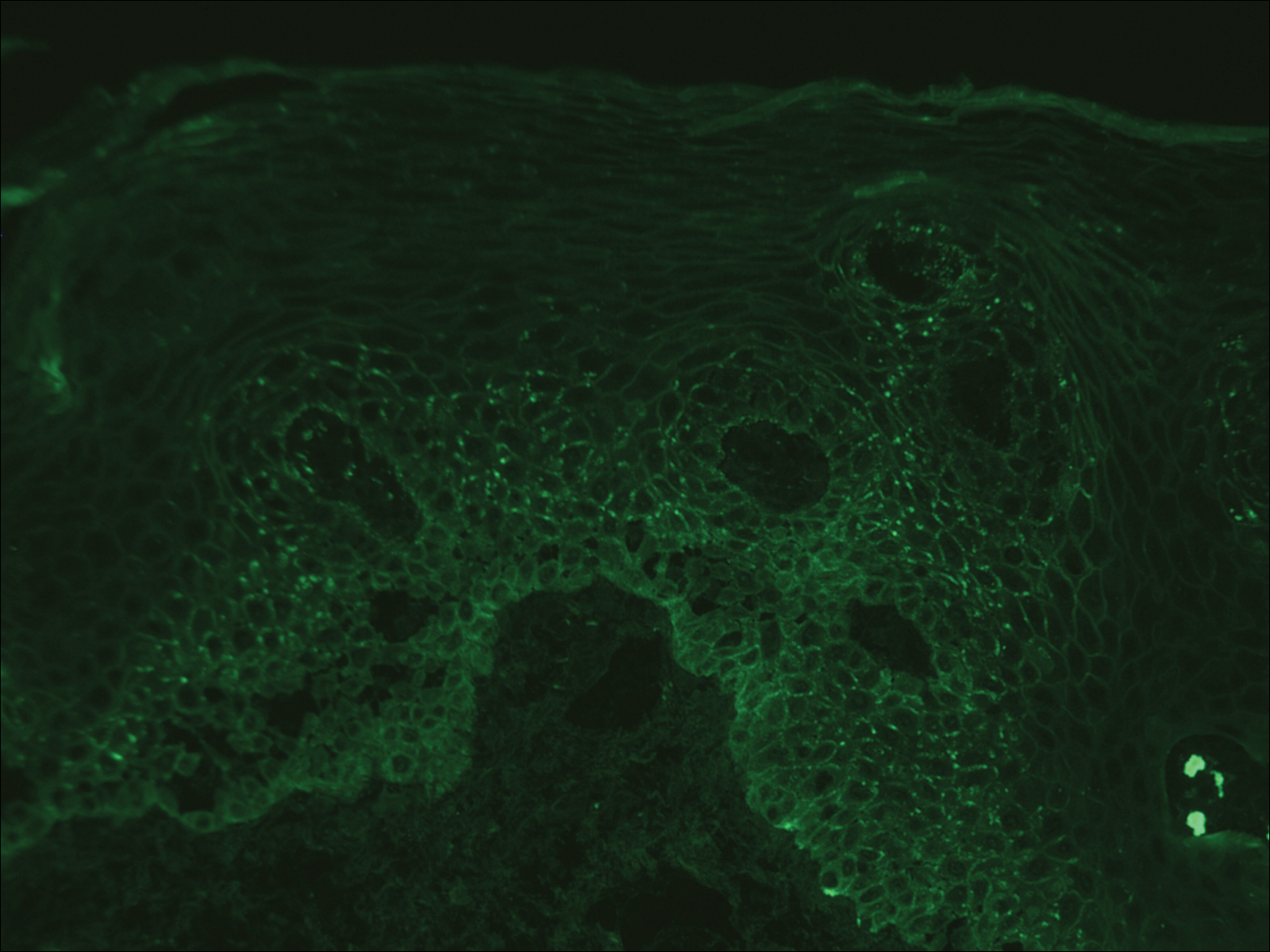

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed an 8.1-cm pelvic mass that a subsequent biopsy revealed to be a follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Biopsies of the mouth ulcers showed a mildly hyperplastic mucosa with acantholysis and interface change with dyskeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution (Figure 1). The pathologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunoblotting, and indirect immunofluorescence were not performed. The patient died within a few months after the initial presentation from bronchiolitis obliterans, a potentially fatal complication of PNP.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease associated with neoplasia, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders and thymoma.1 Oral mucosal erosions and crusting along the lips commonly is seen along with cutaneous involvement. The main histologic features are interface changes with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate and variable acantholysis.2

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin classically shows IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution, usually in a granular or linear distribution along the basement membrane. This same pattern of direct immunofluorescence is seen in pemphigus erythematosus; however, pemphigus erythematosus is clinically distinct from PNP, lacking mucosal involvement and affecting the face and/or seborrheic areas with an appearance more similar to seborrheic dermatitis or lupus erythematosus, depending on the patient.3 Indirect immunofluorescence with rat bladder epithelium typically is positive in PNP and can be a helpful feature in distinguishing PNP from other autoimmune blistering diseases (eg, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus).2

Immunoblotting assays via serology often detect numerous antigens in patients with PNP, including but not limited to plectin, desmoplakin, bullous pemphigoid antigens, envoplakin, desmoplakin II, and desmogleins 1 and 3.4 Some of these autoantibodies have been identified in tumors associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus, particularly Castleman disease and follicular dendritic cell sarcoma.

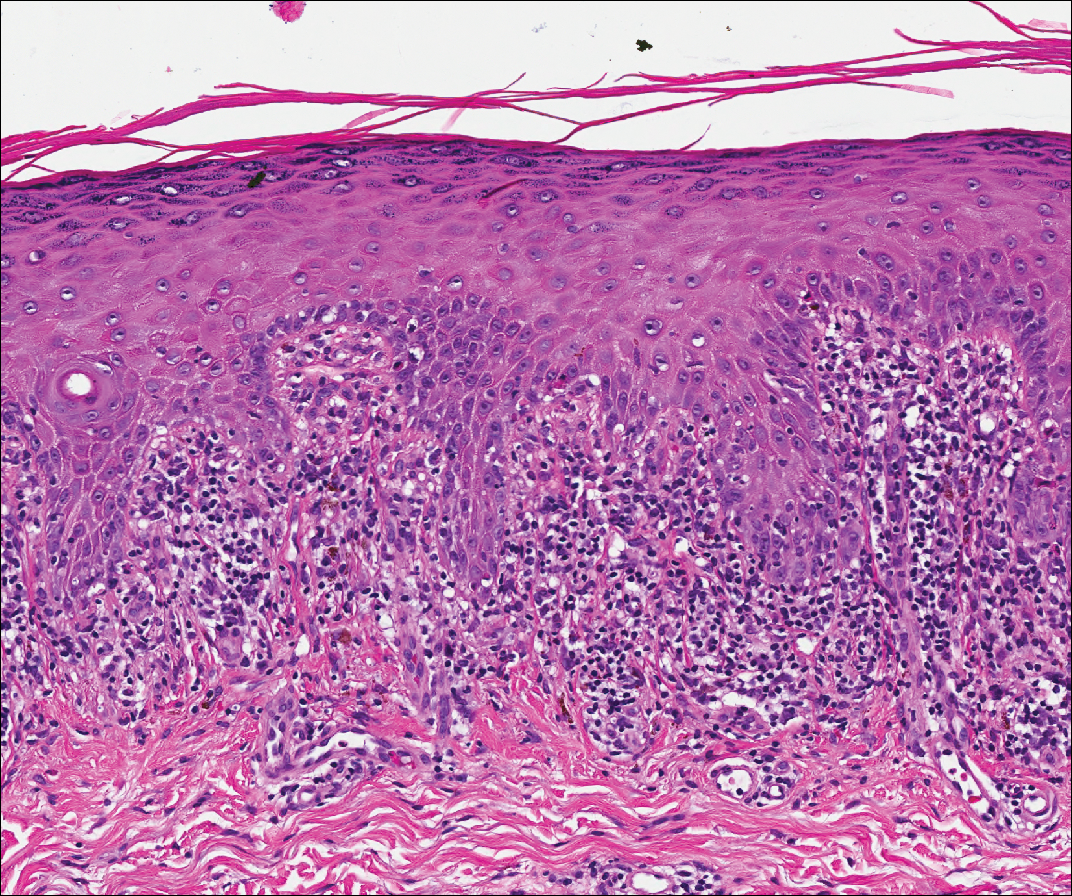

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can have a similar histologic appearance to PNP with prominent dyskeratosis and characteristically shows satellite cell necrosis consisting of dyskeratosis with surrounding lymphocytes (Figure 2). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a feature of GVHD. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative; however, nonspecific IgM and complement C3 deposition at the dermoepidermal junction and around the superficial vasculature has been reported in 39% of cases.5 Early chronic GVHD often shows retained lichenoid interface change, but late chronic GVHD has a sclerodermoid morphology that is easily distinguished histologically from PNP. Patients also have a history of either a bone marrow or solid organ transplant.6

Lichen planus also shows interface change with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate; however, acantholysis typically is not seen and, there often is prominent hypergranulosis (Figure 3). Mucosal lesions often show more subtle features with decreased hyperkeratosis, more subtle hypergranulosis, and decreased interface change with plasma cells in the inflammatory infiltrate.6 Additionally, direct immunofluorescence is either negative or shows IgM-positive colloid bodies and/or an irregular band of fibrinogen at the dermoepidermal junction. The characteristic intercellular and granular/linear IgG positivity at the dermoepidermal junction of PNP is not seen.

Lupus erythematosus is an interface dermatitis with histologic features that can overlap with PNP, in addition to positive direct immunofluorescence, which has been seen in 50% to 94% of cases and can vary depending on previous steroid treatment and timing of the biopsy in the disease process.7 Unlike PNP, lupus erythematosus has a full-house pattern on direct immunofluorescence with IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement C3 deposition in a granular pattern at the dermoepidermal junction. While PNP also typically shows granular deposition of IgG and complement C3 at the dermoepidermal junction, there also is intercellular positivity without a full-house pattern. While both conditions show interface change, histologic features that distinguish lupus erythematosus from PNP are a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, and increased dermal mucin (Figure 4). Subacute lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus can have similar histologic features, and definitive distinction on biopsy is not always possible; however, subacute lupus erythematosus shows milder follicular plugging and milder to absent basement membrane thickening, and the inflammatory infiltrate typically is sparser than in discoid lupus erythematosus.7 Subacute lupus erythematosus also can show anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A antibodies, which typically are not seen in discoid lupus eythematosus.8

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is on a spectrum with toxic epidermal necrolysis, with SJS involving less than 10% and toxic epidermal necrolysis involving 30% or more of the body surface area.5 Erythema multiforme also is on the histologic spectrum of SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis; however, erythema multiforme typically is more inflammatory than SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Stevens-Johnson syndrome typically affects older adults and shows both cutaneous and mucosal involvement; however, isolated mucosal involvement can be seen in children.5 Drugs, particularly sulfonamide antibiotics, usually are implicated as causative agents, but infections from Mycoplasma and other pathogens also may be the cause. There is notable clinical (with a combination of mucosal and cutaneous lesions) as well as histologic overlap between SJS and PNP. The density of the lichenoid infiltrate is variable, with dyskeratosis, basal cell hydropic degeneration, and occasional formation of subepidermal clefts (Figure 5). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a characteristic feature of SJS, and direct immunofluorescence generally is negative.

- Camisa C, Helm TN. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a distinct neoplasia-induced autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:883-886.

- Joly P, Richard C, Gilbert D, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical, histologic, and immunologic features in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:619-626.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Acantholytic disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:151-179.

- Billet ES, Grando AS, Pittelkow MR. Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome: review of the literature and support for a cytotoxic role in pathogenesis. Autoimmunity. 2006;36:617-630.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:219-255.

- Billings SD, Cotton J. Inflammatory Dermatopathology: A Pathologist's Survival Guide. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Idiopathic connective tissue disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:711-757.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

A workup for infectious organisms and vasculitis was negative. The patient reported unintentional weight loss despite taking oral steroids prescribed by her pulmonologist for severe obstructive lung disease that appeared to develop around the same time as the mouth ulcers.

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed an 8.1-cm pelvic mass that a subsequent biopsy revealed to be a follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Biopsies of the mouth ulcers showed a mildly hyperplastic mucosa with acantholysis and interface change with dyskeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution (Figure 1). The pathologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunoblotting, and indirect immunofluorescence were not performed. The patient died within a few months after the initial presentation from bronchiolitis obliterans, a potentially fatal complication of PNP.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease associated with neoplasia, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders and thymoma.1 Oral mucosal erosions and crusting along the lips commonly is seen along with cutaneous involvement. The main histologic features are interface changes with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate and variable acantholysis.2

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin classically shows IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution, usually in a granular or linear distribution along the basement membrane. This same pattern of direct immunofluorescence is seen in pemphigus erythematosus; however, pemphigus erythematosus is clinically distinct from PNP, lacking mucosal involvement and affecting the face and/or seborrheic areas with an appearance more similar to seborrheic dermatitis or lupus erythematosus, depending on the patient.3 Indirect immunofluorescence with rat bladder epithelium typically is positive in PNP and can be a helpful feature in distinguishing PNP from other autoimmune blistering diseases (eg, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus).2

Immunoblotting assays via serology often detect numerous antigens in patients with PNP, including but not limited to plectin, desmoplakin, bullous pemphigoid antigens, envoplakin, desmoplakin II, and desmogleins 1 and 3.4 Some of these autoantibodies have been identified in tumors associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus, particularly Castleman disease and follicular dendritic cell sarcoma.

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can have a similar histologic appearance to PNP with prominent dyskeratosis and characteristically shows satellite cell necrosis consisting of dyskeratosis with surrounding lymphocytes (Figure 2). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a feature of GVHD. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative; however, nonspecific IgM and complement C3 deposition at the dermoepidermal junction and around the superficial vasculature has been reported in 39% of cases.5 Early chronic GVHD often shows retained lichenoid interface change, but late chronic GVHD has a sclerodermoid morphology that is easily distinguished histologically from PNP. Patients also have a history of either a bone marrow or solid organ transplant.6

Lichen planus also shows interface change with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate; however, acantholysis typically is not seen and, there often is prominent hypergranulosis (Figure 3). Mucosal lesions often show more subtle features with decreased hyperkeratosis, more subtle hypergranulosis, and decreased interface change with plasma cells in the inflammatory infiltrate.6 Additionally, direct immunofluorescence is either negative or shows IgM-positive colloid bodies and/or an irregular band of fibrinogen at the dermoepidermal junction. The characteristic intercellular and granular/linear IgG positivity at the dermoepidermal junction of PNP is not seen.

Lupus erythematosus is an interface dermatitis with histologic features that can overlap with PNP, in addition to positive direct immunofluorescence, which has been seen in 50% to 94% of cases and can vary depending on previous steroid treatment and timing of the biopsy in the disease process.7 Unlike PNP, lupus erythematosus has a full-house pattern on direct immunofluorescence with IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement C3 deposition in a granular pattern at the dermoepidermal junction. While PNP also typically shows granular deposition of IgG and complement C3 at the dermoepidermal junction, there also is intercellular positivity without a full-house pattern. While both conditions show interface change, histologic features that distinguish lupus erythematosus from PNP are a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, and increased dermal mucin (Figure 4). Subacute lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus can have similar histologic features, and definitive distinction on biopsy is not always possible; however, subacute lupus erythematosus shows milder follicular plugging and milder to absent basement membrane thickening, and the inflammatory infiltrate typically is sparser than in discoid lupus erythematosus.7 Subacute lupus erythematosus also can show anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A antibodies, which typically are not seen in discoid lupus eythematosus.8

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is on a spectrum with toxic epidermal necrolysis, with SJS involving less than 10% and toxic epidermal necrolysis involving 30% or more of the body surface area.5 Erythema multiforme also is on the histologic spectrum of SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis; however, erythema multiforme typically is more inflammatory than SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Stevens-Johnson syndrome typically affects older adults and shows both cutaneous and mucosal involvement; however, isolated mucosal involvement can be seen in children.5 Drugs, particularly sulfonamide antibiotics, usually are implicated as causative agents, but infections from Mycoplasma and other pathogens also may be the cause. There is notable clinical (with a combination of mucosal and cutaneous lesions) as well as histologic overlap between SJS and PNP. The density of the lichenoid infiltrate is variable, with dyskeratosis, basal cell hydropic degeneration, and occasional formation of subepidermal clefts (Figure 5). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a characteristic feature of SJS, and direct immunofluorescence generally is negative.

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

A workup for infectious organisms and vasculitis was negative. The patient reported unintentional weight loss despite taking oral steroids prescribed by her pulmonologist for severe obstructive lung disease that appeared to develop around the same time as the mouth ulcers.

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed an 8.1-cm pelvic mass that a subsequent biopsy revealed to be a follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Biopsies of the mouth ulcers showed a mildly hyperplastic mucosa with acantholysis and interface change with dyskeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution (Figure 1). The pathologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunoblotting, and indirect immunofluorescence were not performed. The patient died within a few months after the initial presentation from bronchiolitis obliterans, a potentially fatal complication of PNP.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease associated with neoplasia, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders and thymoma.1 Oral mucosal erosions and crusting along the lips commonly is seen along with cutaneous involvement. The main histologic features are interface changes with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate and variable acantholysis.2

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin classically shows IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution, usually in a granular or linear distribution along the basement membrane. This same pattern of direct immunofluorescence is seen in pemphigus erythematosus; however, pemphigus erythematosus is clinically distinct from PNP, lacking mucosal involvement and affecting the face and/or seborrheic areas with an appearance more similar to seborrheic dermatitis or lupus erythematosus, depending on the patient.3 Indirect immunofluorescence with rat bladder epithelium typically is positive in PNP and can be a helpful feature in distinguishing PNP from other autoimmune blistering diseases (eg, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus).2

Immunoblotting assays via serology often detect numerous antigens in patients with PNP, including but not limited to plectin, desmoplakin, bullous pemphigoid antigens, envoplakin, desmoplakin II, and desmogleins 1 and 3.4 Some of these autoantibodies have been identified in tumors associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus, particularly Castleman disease and follicular dendritic cell sarcoma.

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can have a similar histologic appearance to PNP with prominent dyskeratosis and characteristically shows satellite cell necrosis consisting of dyskeratosis with surrounding lymphocytes (Figure 2). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a feature of GVHD. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative; however, nonspecific IgM and complement C3 deposition at the dermoepidermal junction and around the superficial vasculature has been reported in 39% of cases.5 Early chronic GVHD often shows retained lichenoid interface change, but late chronic GVHD has a sclerodermoid morphology that is easily distinguished histologically from PNP. Patients also have a history of either a bone marrow or solid organ transplant.6

Lichen planus also shows interface change with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate; however, acantholysis typically is not seen and, there often is prominent hypergranulosis (Figure 3). Mucosal lesions often show more subtle features with decreased hyperkeratosis, more subtle hypergranulosis, and decreased interface change with plasma cells in the inflammatory infiltrate.6 Additionally, direct immunofluorescence is either negative or shows IgM-positive colloid bodies and/or an irregular band of fibrinogen at the dermoepidermal junction. The characteristic intercellular and granular/linear IgG positivity at the dermoepidermal junction of PNP is not seen.

Lupus erythematosus is an interface dermatitis with histologic features that can overlap with PNP, in addition to positive direct immunofluorescence, which has been seen in 50% to 94% of cases and can vary depending on previous steroid treatment and timing of the biopsy in the disease process.7 Unlike PNP, lupus erythematosus has a full-house pattern on direct immunofluorescence with IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement C3 deposition in a granular pattern at the dermoepidermal junction. While PNP also typically shows granular deposition of IgG and complement C3 at the dermoepidermal junction, there also is intercellular positivity without a full-house pattern. While both conditions show interface change, histologic features that distinguish lupus erythematosus from PNP are a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, and increased dermal mucin (Figure 4). Subacute lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus can have similar histologic features, and definitive distinction on biopsy is not always possible; however, subacute lupus erythematosus shows milder follicular plugging and milder to absent basement membrane thickening, and the inflammatory infiltrate typically is sparser than in discoid lupus erythematosus.7 Subacute lupus erythematosus also can show anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A antibodies, which typically are not seen in discoid lupus eythematosus.8

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is on a spectrum with toxic epidermal necrolysis, with SJS involving less than 10% and toxic epidermal necrolysis involving 30% or more of the body surface area.5 Erythema multiforme also is on the histologic spectrum of SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis; however, erythema multiforme typically is more inflammatory than SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Stevens-Johnson syndrome typically affects older adults and shows both cutaneous and mucosal involvement; however, isolated mucosal involvement can be seen in children.5 Drugs, particularly sulfonamide antibiotics, usually are implicated as causative agents, but infections from Mycoplasma and other pathogens also may be the cause. There is notable clinical (with a combination of mucosal and cutaneous lesions) as well as histologic overlap between SJS and PNP. The density of the lichenoid infiltrate is variable, with dyskeratosis, basal cell hydropic degeneration, and occasional formation of subepidermal clefts (Figure 5). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a characteristic feature of SJS, and direct immunofluorescence generally is negative.

- Camisa C, Helm TN. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a distinct neoplasia-induced autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:883-886.

- Joly P, Richard C, Gilbert D, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical, histologic, and immunologic features in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:619-626.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Acantholytic disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:151-179.

- Billet ES, Grando AS, Pittelkow MR. Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome: review of the literature and support for a cytotoxic role in pathogenesis. Autoimmunity. 2006;36:617-630.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:219-255.

- Billings SD, Cotton J. Inflammatory Dermatopathology: A Pathologist's Survival Guide. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Idiopathic connective tissue disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:711-757.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

- Camisa C, Helm TN. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a distinct neoplasia-induced autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:883-886.

- Joly P, Richard C, Gilbert D, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical, histologic, and immunologic features in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:619-626.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Acantholytic disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:151-179.

- Billet ES, Grando AS, Pittelkow MR. Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome: review of the literature and support for a cytotoxic role in pathogenesis. Autoimmunity. 2006;36:617-630.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:219-255.

- Billings SD, Cotton J. Inflammatory Dermatopathology: A Pathologist's Survival Guide. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Idiopathic connective tissue disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:711-757.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

A 41-year-old woman presented with painful ulcers on the oral mucosa of 2 months' duration that were unresponsive to treatment with acyclovir. She had been diagnosed with a pelvic tumor a few weeks prior to the development of the mouth ulcers. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed positive IgG and complement C3 with an intercellular distribution. A biopsy of an oral lesion was performed.

Reticular Hyperpigmented Patches With Indurated Subcutaneous Plaques

The Diagnosis: Superficial Migratory Thrombophlebitis

On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included livedoid vasculopathy, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, erythema ab igne, cholesterol embolism, and livedo reticularis. Laboratory investigation included antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, serum protein electrophoresis, and coagulation tests. Pertinent findings included transient low total complement activity but normal complement protein C2, C3, and C5 levels and negative cryoglobulins. Additional laboratory testing revealed elevated antiphosphatidylserine IgG, which remained elevated 12 weeks later.

New lesions continued to appear over the next several months as painful, erythematous, linear, pruritic nodules that resolved as hyperpigmented linear patches, which intersected to form a livedo reticularis-like pattern that covered the lower legs. Biopsy of an erythematous nodule on the right leg revealed fibrin occlusion of a medium-sized vein in the subcutaneous fat. Direct immunofluorescence was not specific. Venous duplex ultrasonography demonstrated chronic superficial thrombophlebitis and was crucial to the diagnosis. Ultimately, the patient's history, clinical presentation, laboratory results, venous studies, and histopathologic analysis were consistent with a diagnosis of superficial migratory thrombophlebitis (SMT) with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation presenting in a reticular pattern that mimicked livedoid vasculopathy, livedo reticularis, or erythema ab igne.

Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis, also known as thrombophlebitis migrans, is defined as the recurrent formation of thrombi within superficial veins.1 The presence of a thrombus in a superficial vein evokes an inflammatory response, resulting in swelling, tenderness, erythema, and warmth in the affected area. Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis has been associated with several etiologies, including pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, APS, vasculitic disorders, and malignancies (eg, pancreas, lung, breast), as well as infections such as secondary syphilis.1

When SMT is associated with an occult malignancy, it is known as Trousseau syndrome. Common malignancies found in association with Trousseau syndrome include pancreatic, lung, and breast cancers.2 A systematic review from 2008 evaluated the utility of extensive cancer screening strategies in patients with newly diagnosed, unprovoked venous thromboembolic events.3 Using a wide screening strategy that included computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, the investigators detected a considerable number of formerly undiagnosed cancers, increasing detection rates from 49.4% to 69.7%. After the diagnosis of SMT was made in our patient, computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, but the findings were unremarkable.

Because occult malignancy was excluded in our patient, the likely etiology of SMT was APS, an acquired autoimmune condition diagnosed based on the presence of a vascular thrombosis and/or pregnancy failure in women as well as elevation of at least one antiphospholipid antibody laboratory marker (eg, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, and anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibody) on 2 or more occasions at least 12 weeks apart.4 Other antibodies such as those directed against negatively charged phospholipids (eg, antiphosphatidylserine [which was elevated in our patient], phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidic acid) have been reported in patients with APS, although their diagnostic use is controversial.5 For example, the presence of antiphosphatidylserine antibodies has been considered common but not specific in patients with APS.4 However, a recent observational study demonstrated that antiphosphatidylserine antibodies are highly specific (87%) and useful in diagnosing clinical APS cases in the presence of other negative markers.6

In our patient, diagnosis of SMT with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in a reticular pattern was based on the patient's medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings, as well as laboratory results and venous studies. However, it is important to note that a livedo reticularis-like pattern also is a very common finding in APS and must be included in the differential diagnosis of a reticular network on the skin.7 Moreover, differentiating livedo reticularis from SMT has prognostic importance since SMT may be associated with underlying malignancies while livedo reticularis may be associated with Sneddon syndrome, a disorder in which neurologic vascular events (eg, cerebrovascular accidents) are present.8 While this distinction is important, there are no pathognomonic histologic findings seen in livedo reticularis, and consideration of the clinical picture and additional testing is critical.4,8

Livedo vasculopathy was excluded in our patient due to the lack of diagnostic histopathologic findings, such as fibrin deposition and thrombus formation involving the upper- and mid-dermal capillaries.9 Furthermore, characteristic direct immunofluorescence findings of a homogenous or granular deposition in the vessel wall consisting of immune complexes, complement, and fibrin were absent in our patient.9 Our patient also lacked common clinical findings found in livedo vasculopathy such as small ulcerations or atrophic, porcelain-white scars on the lower legs. Erythema ab igne also was excluded in our patient due to the absence of heat exposure and presence of fibrin occlusion in the superficial leg veins. Physiologic livedo reticularis, defined as a livedoid pattern due to physiologic changes in the skin in response to cold exposure,10 also was excluded, as our patient's cutaneous changes included an alteration in pigmentation with a brown reticular pattern and no blanching, erythematous or violaceous hue, warmth, or tenderness.

In conclusion, SMT is a disorder with multiple associations that may clinically mimic livedo reticularis and livedoid vasculopathy when postinflammatory hyperpigmentation has a lacelike or livedoid pattern. While nontraditional antibodies may be useful in diagnosis in patients suspected of having APS with otherwise negative markers, standardized assays and further studies are needed to determine the specificity and value of these antibodies, particularly when used in isolation. Our patient's elevated antiphosphatidylserine IgG may have been the cause of her hypercoagulable state causing the SMT. A livedoid pattern is a common finding in APS and also was seen in our patient with SMT, but the differentiation of the brown pigmentary change and more active erythema was critical to the appropriate clinical workup of our patient.

- Samlaska CP, James WD. Superficial thrombophlebitis. II. secondary hypercoagulable states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:1-18.

- Rigdon EE. Trousseau's syndrome and acute arterial thrombosis. Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;8:214-218.

- Carrier M, Le Gal G, Wells PS, et al. Systematic review: the Trousseau syndrome revisited: should we screen extensively for cancer in patients with venous thromboembolism? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:323-333.

- Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306.

- Bertolaccini ML, Amengual O, Atsumi T, et al. 'Non-criteria' aPL tests: report of a task force and preconference workshop at the 13th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies, Galveston, TX, USA, April 2010. Lupus. 2011;20:191-205.

- Khogeer H, Alfattani A, Al Kaff M, et al. Antiphosphatidylserine antibodies as diagnostic indicators of antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus. 2015;24:186-190.

- Gibson GE, Su WP, Pittelkow MR. Antiphospholipid syndrome and the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6 pt 1):970-982.

- Francès C, Papo T, Wechsler B, et al. Sneddon syndrome with or without antiphospholipid antibodies. a comparative study in 46 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1999;78:209-219.

- Vasudevan B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478-488.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases Of The Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2006.

The Diagnosis: Superficial Migratory Thrombophlebitis

On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included livedoid vasculopathy, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, erythema ab igne, cholesterol embolism, and livedo reticularis. Laboratory investigation included antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, serum protein electrophoresis, and coagulation tests. Pertinent findings included transient low total complement activity but normal complement protein C2, C3, and C5 levels and negative cryoglobulins. Additional laboratory testing revealed elevated antiphosphatidylserine IgG, which remained elevated 12 weeks later.

New lesions continued to appear over the next several months as painful, erythematous, linear, pruritic nodules that resolved as hyperpigmented linear patches, which intersected to form a livedo reticularis-like pattern that covered the lower legs. Biopsy of an erythematous nodule on the right leg revealed fibrin occlusion of a medium-sized vein in the subcutaneous fat. Direct immunofluorescence was not specific. Venous duplex ultrasonography demonstrated chronic superficial thrombophlebitis and was crucial to the diagnosis. Ultimately, the patient's history, clinical presentation, laboratory results, venous studies, and histopathologic analysis were consistent with a diagnosis of superficial migratory thrombophlebitis (SMT) with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation presenting in a reticular pattern that mimicked livedoid vasculopathy, livedo reticularis, or erythema ab igne.

Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis, also known as thrombophlebitis migrans, is defined as the recurrent formation of thrombi within superficial veins.1 The presence of a thrombus in a superficial vein evokes an inflammatory response, resulting in swelling, tenderness, erythema, and warmth in the affected area. Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis has been associated with several etiologies, including pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, APS, vasculitic disorders, and malignancies (eg, pancreas, lung, breast), as well as infections such as secondary syphilis.1

When SMT is associated with an occult malignancy, it is known as Trousseau syndrome. Common malignancies found in association with Trousseau syndrome include pancreatic, lung, and breast cancers.2 A systematic review from 2008 evaluated the utility of extensive cancer screening strategies in patients with newly diagnosed, unprovoked venous thromboembolic events.3 Using a wide screening strategy that included computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, the investigators detected a considerable number of formerly undiagnosed cancers, increasing detection rates from 49.4% to 69.7%. After the diagnosis of SMT was made in our patient, computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, but the findings were unremarkable.

Because occult malignancy was excluded in our patient, the likely etiology of SMT was APS, an acquired autoimmune condition diagnosed based on the presence of a vascular thrombosis and/or pregnancy failure in women as well as elevation of at least one antiphospholipid antibody laboratory marker (eg, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, and anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibody) on 2 or more occasions at least 12 weeks apart.4 Other antibodies such as those directed against negatively charged phospholipids (eg, antiphosphatidylserine [which was elevated in our patient], phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidic acid) have been reported in patients with APS, although their diagnostic use is controversial.5 For example, the presence of antiphosphatidylserine antibodies has been considered common but not specific in patients with APS.4 However, a recent observational study demonstrated that antiphosphatidylserine antibodies are highly specific (87%) and useful in diagnosing clinical APS cases in the presence of other negative markers.6

In our patient, diagnosis of SMT with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in a reticular pattern was based on the patient's medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings, as well as laboratory results and venous studies. However, it is important to note that a livedo reticularis-like pattern also is a very common finding in APS and must be included in the differential diagnosis of a reticular network on the skin.7 Moreover, differentiating livedo reticularis from SMT has prognostic importance since SMT may be associated with underlying malignancies while livedo reticularis may be associated with Sneddon syndrome, a disorder in which neurologic vascular events (eg, cerebrovascular accidents) are present.8 While this distinction is important, there are no pathognomonic histologic findings seen in livedo reticularis, and consideration of the clinical picture and additional testing is critical.4,8

Livedo vasculopathy was excluded in our patient due to the lack of diagnostic histopathologic findings, such as fibrin deposition and thrombus formation involving the upper- and mid-dermal capillaries.9 Furthermore, characteristic direct immunofluorescence findings of a homogenous or granular deposition in the vessel wall consisting of immune complexes, complement, and fibrin were absent in our patient.9 Our patient also lacked common clinical findings found in livedo vasculopathy such as small ulcerations or atrophic, porcelain-white scars on the lower legs. Erythema ab igne also was excluded in our patient due to the absence of heat exposure and presence of fibrin occlusion in the superficial leg veins. Physiologic livedo reticularis, defined as a livedoid pattern due to physiologic changes in the skin in response to cold exposure,10 also was excluded, as our patient's cutaneous changes included an alteration in pigmentation with a brown reticular pattern and no blanching, erythematous or violaceous hue, warmth, or tenderness.

In conclusion, SMT is a disorder with multiple associations that may clinically mimic livedo reticularis and livedoid vasculopathy when postinflammatory hyperpigmentation has a lacelike or livedoid pattern. While nontraditional antibodies may be useful in diagnosis in patients suspected of having APS with otherwise negative markers, standardized assays and further studies are needed to determine the specificity and value of these antibodies, particularly when used in isolation. Our patient's elevated antiphosphatidylserine IgG may have been the cause of her hypercoagulable state causing the SMT. A livedoid pattern is a common finding in APS and also was seen in our patient with SMT, but the differentiation of the brown pigmentary change and more active erythema was critical to the appropriate clinical workup of our patient.

The Diagnosis: Superficial Migratory Thrombophlebitis

On initial presentation, the differential diagnosis included livedoid vasculopathy, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, erythema ab igne, cholesterol embolism, and livedo reticularis. Laboratory investigation included antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, serum protein electrophoresis, and coagulation tests. Pertinent findings included transient low total complement activity but normal complement protein C2, C3, and C5 levels and negative cryoglobulins. Additional laboratory testing revealed elevated antiphosphatidylserine IgG, which remained elevated 12 weeks later.

New lesions continued to appear over the next several months as painful, erythematous, linear, pruritic nodules that resolved as hyperpigmented linear patches, which intersected to form a livedo reticularis-like pattern that covered the lower legs. Biopsy of an erythematous nodule on the right leg revealed fibrin occlusion of a medium-sized vein in the subcutaneous fat. Direct immunofluorescence was not specific. Venous duplex ultrasonography demonstrated chronic superficial thrombophlebitis and was crucial to the diagnosis. Ultimately, the patient's history, clinical presentation, laboratory results, venous studies, and histopathologic analysis were consistent with a diagnosis of superficial migratory thrombophlebitis (SMT) with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation presenting in a reticular pattern that mimicked livedoid vasculopathy, livedo reticularis, or erythema ab igne.

Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis, also known as thrombophlebitis migrans, is defined as the recurrent formation of thrombi within superficial veins.1 The presence of a thrombus in a superficial vein evokes an inflammatory response, resulting in swelling, tenderness, erythema, and warmth in the affected area. Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis has been associated with several etiologies, including pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, APS, vasculitic disorders, and malignancies (eg, pancreas, lung, breast), as well as infections such as secondary syphilis.1

When SMT is associated with an occult malignancy, it is known as Trousseau syndrome. Common malignancies found in association with Trousseau syndrome include pancreatic, lung, and breast cancers.2 A systematic review from 2008 evaluated the utility of extensive cancer screening strategies in patients with newly diagnosed, unprovoked venous thromboembolic events.3 Using a wide screening strategy that included computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, the investigators detected a considerable number of formerly undiagnosed cancers, increasing detection rates from 49.4% to 69.7%. After the diagnosis of SMT was made in our patient, computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, but the findings were unremarkable.

Because occult malignancy was excluded in our patient, the likely etiology of SMT was APS, an acquired autoimmune condition diagnosed based on the presence of a vascular thrombosis and/or pregnancy failure in women as well as elevation of at least one antiphospholipid antibody laboratory marker (eg, lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, and anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibody) on 2 or more occasions at least 12 weeks apart.4 Other antibodies such as those directed against negatively charged phospholipids (eg, antiphosphatidylserine [which was elevated in our patient], phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidic acid) have been reported in patients with APS, although their diagnostic use is controversial.5 For example, the presence of antiphosphatidylserine antibodies has been considered common but not specific in patients with APS.4 However, a recent observational study demonstrated that antiphosphatidylserine antibodies are highly specific (87%) and useful in diagnosing clinical APS cases in the presence of other negative markers.6

In our patient, diagnosis of SMT with resultant postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in a reticular pattern was based on the patient's medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings, as well as laboratory results and venous studies. However, it is important to note that a livedo reticularis-like pattern also is a very common finding in APS and must be included in the differential diagnosis of a reticular network on the skin.7 Moreover, differentiating livedo reticularis from SMT has prognostic importance since SMT may be associated with underlying malignancies while livedo reticularis may be associated with Sneddon syndrome, a disorder in which neurologic vascular events (eg, cerebrovascular accidents) are present.8 While this distinction is important, there are no pathognomonic histologic findings seen in livedo reticularis, and consideration of the clinical picture and additional testing is critical.4,8