User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Physician Burnout in Dermatology

Many articles about physician burnout and more alarmingly depression and suicide include chilling statistics; however, the data are limited. The same study from Medscape about burnout broken down by medical specialty often is cited.1 Although dermatology fares better than many specialties in this research, the percentages are still abysmal.

I am writing as a physician, for physicians. I do not want to quote the data to you. If you are reading this article, you have probably felt some burnout, even transiently. Maybe you even feel it now, at this very moment. Physicians are competitive capable people. I do not want to present numbers and statistics that make you question the validity of your feelings, whether you fit with the average statistics, or make you try to calculate how many of your friends or colleagues match these statistics. The numbers are terrible, no matter how you look at them, and all trends show them worsening with time.

What is burnout?

To simply define burnout as fatigue or high workload would be to undervalue the term. Physicians are trained through college, medical school, and countless hours of residency to cope with both challenges. Maslach et al2 defined burnout as “a psychological syndrome in response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” leading to “overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.”

Who does burnout affect?

Physician burnout affects both the patient and the physician. It has been demonstrated that physician burnout leads to lower patient satisfaction and care as well as higher risk for medical errors. There are the more obvious and direct effects on the physician, with affected physicians having much higher employment turnover and risk for addiction and suicide.3 One could argue that there are even more downstream effects of burnout, including physicians’ families who may be directly affected and even societal effects when fully trained physicians leave the clinical arena to pursue other careers.

How do you recognize when you are burnt out?

The first time I recognized that I was burnt out was in medical school. I understood my burnout through the lens of my undergraduate training in anthropology as compassion fatigue, a term that has been used to describe the lack of empathy that can develop when any individual is presented with an overwhelming tragedy or horror. When you are in survival mode—waking up just to survive the next day or clinic shift or call—you are surviving but hardly thriving as a physician.3 I believe that humans have a tremendous capacity for survival, but when we are in survival mode we have little energy leftover for the pleasures of life, from family to hobbies. I would similarly argue that in survival mode we have limited ability to appreciate the pain and suffering our patients are experiencing. Survival mode limits our ability as physicians to connect with our patients and to engage in the full spectrum of emotion in our time outside of our job.

What are the causes of burnout in dermatology?

As dermatologists, we often have milder on-call schedules and fewer critically ill patients than many of our medical colleagues. For this reason, we may be afraid to address the real role of physician burnout in our field. Fellow dermatologist Jeffrey Benabio, MD (San Diego, California), notes that the phrase dermatologist burnout may even seem oxymoronic, but we face many of the same daily frustrations with electronic medical records, increasing patient volume, and insurance struggles.4 The electronic medical record looms large in many physicians’ complaints these days. A recent article in the New York Times described the physician as “the highest-paid clerical worker in the hospital,”5 which is not wrong. For every hour of patient time, we have nearly double that spent on paperwork.5

Dike Drummond, MD, a family practice physician who focuses on physician burnout, notes that physicians are taught very early to put the patient first, but it is never discussed when or how to turn this switch off.3 However, there is little written about dermatology-specific burnout. A problem that is not studied or even considered will be harder to fix.

Why does it matter?

I believe that addressing physician burnout is critical for 2 reasons: (1) we can improve patient care by improving patient satisfaction and decreasing medical error, and (2) we can find greater satisfaction and professional fulfillment while caring for our patients. Ultimately, patient care and physician care are intimately linked; as stated by Thomas et al,6 “[p]hysicians who are well can best serve their patients.”

As a resident in 2018, I recognize that my coresidents and I are training as physicians in the time of “duty hours” and an ongoing discussion of burnout. However, I sense a burnout fatigue setting in among residents, many who do not want to discuss wellness anymore. The newer data suggest that work hour restrictions do not improve patient safety, negating one of the driving reasons for the change.7 At the same time, residency programs are initiating wellness programs in response to the growing literature on physician burnout. These wellness programs vary in the types of activities included, from individual coping techniques such as mindfulness training to social gatherings for the residents. In general, these wellness initiatives focus on burnout at the individual level, but they do not take into account systemic or structural challenges that might contribute to this worsening epidemic.

Final Thoughts

As a profession, I believe that physicians have internalized the concept of burnout to equate with a personal individual failing. At various times in my training, I have felt that if I could just practice mediation, study more, or shift my perspective, I personally could overcome burnout. I have intermittently felt my burnout as proof that I should never have become a physician. As a woman and the first physician in my family, fighting the sense of burnout so early in my career seemed demoralizing and nearly drove me to change my career path. It exacerbated my sense of imposter syndrome: that I never truly belonged in medicine at all. After much soul-searching, I have concluded that burnout is a concept propagated by administrators and businesspeople to stigmatize the reaction by many physicians to the growing trends in medicine and cast it as a personal failure rather than as the symptom of a broken medical system.

If we continue to identify burnout as an individual failing and treat it as such, I believe that we will fail to stem the growing trend within dermatology and within medicine more broadly. We need to consider the driving factors behind dermatology burnout so that we can begin to address them at a structural level.

- Peckham C. Medscape national physician burnout & depression report 2018. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6009235. Published January 17, 2018. Accessed June 21, 2018.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job

burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. - Drummond D. Physician burnout: its origin, symptoms, and five main causes. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22:42-47.

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed June 30, 2018.

- Verghese A. How tech can turn doctors into clerical workers. New York Times. May 16, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/05/16/magazine/health-issue-what-we-lose-with-data-driven-medicine.html. Accessed July 3, 2018.

- Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319:1541-1542.

- Osborne R, Parshuram CS. Delinking resident duty hours from patient safety [published online December 11, 2014]. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(suppl 1):S2.

Many articles about physician burnout and more alarmingly depression and suicide include chilling statistics; however, the data are limited. The same study from Medscape about burnout broken down by medical specialty often is cited.1 Although dermatology fares better than many specialties in this research, the percentages are still abysmal.

I am writing as a physician, for physicians. I do not want to quote the data to you. If you are reading this article, you have probably felt some burnout, even transiently. Maybe you even feel it now, at this very moment. Physicians are competitive capable people. I do not want to present numbers and statistics that make you question the validity of your feelings, whether you fit with the average statistics, or make you try to calculate how many of your friends or colleagues match these statistics. The numbers are terrible, no matter how you look at them, and all trends show them worsening with time.

What is burnout?

To simply define burnout as fatigue or high workload would be to undervalue the term. Physicians are trained through college, medical school, and countless hours of residency to cope with both challenges. Maslach et al2 defined burnout as “a psychological syndrome in response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” leading to “overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.”

Who does burnout affect?

Physician burnout affects both the patient and the physician. It has been demonstrated that physician burnout leads to lower patient satisfaction and care as well as higher risk for medical errors. There are the more obvious and direct effects on the physician, with affected physicians having much higher employment turnover and risk for addiction and suicide.3 One could argue that there are even more downstream effects of burnout, including physicians’ families who may be directly affected and even societal effects when fully trained physicians leave the clinical arena to pursue other careers.

How do you recognize when you are burnt out?

The first time I recognized that I was burnt out was in medical school. I understood my burnout through the lens of my undergraduate training in anthropology as compassion fatigue, a term that has been used to describe the lack of empathy that can develop when any individual is presented with an overwhelming tragedy or horror. When you are in survival mode—waking up just to survive the next day or clinic shift or call—you are surviving but hardly thriving as a physician.3 I believe that humans have a tremendous capacity for survival, but when we are in survival mode we have little energy leftover for the pleasures of life, from family to hobbies. I would similarly argue that in survival mode we have limited ability to appreciate the pain and suffering our patients are experiencing. Survival mode limits our ability as physicians to connect with our patients and to engage in the full spectrum of emotion in our time outside of our job.

What are the causes of burnout in dermatology?

As dermatologists, we often have milder on-call schedules and fewer critically ill patients than many of our medical colleagues. For this reason, we may be afraid to address the real role of physician burnout in our field. Fellow dermatologist Jeffrey Benabio, MD (San Diego, California), notes that the phrase dermatologist burnout may even seem oxymoronic, but we face many of the same daily frustrations with electronic medical records, increasing patient volume, and insurance struggles.4 The electronic medical record looms large in many physicians’ complaints these days. A recent article in the New York Times described the physician as “the highest-paid clerical worker in the hospital,”5 which is not wrong. For every hour of patient time, we have nearly double that spent on paperwork.5

Dike Drummond, MD, a family practice physician who focuses on physician burnout, notes that physicians are taught very early to put the patient first, but it is never discussed when or how to turn this switch off.3 However, there is little written about dermatology-specific burnout. A problem that is not studied or even considered will be harder to fix.

Why does it matter?

I believe that addressing physician burnout is critical for 2 reasons: (1) we can improve patient care by improving patient satisfaction and decreasing medical error, and (2) we can find greater satisfaction and professional fulfillment while caring for our patients. Ultimately, patient care and physician care are intimately linked; as stated by Thomas et al,6 “[p]hysicians who are well can best serve their patients.”

As a resident in 2018, I recognize that my coresidents and I are training as physicians in the time of “duty hours” and an ongoing discussion of burnout. However, I sense a burnout fatigue setting in among residents, many who do not want to discuss wellness anymore. The newer data suggest that work hour restrictions do not improve patient safety, negating one of the driving reasons for the change.7 At the same time, residency programs are initiating wellness programs in response to the growing literature on physician burnout. These wellness programs vary in the types of activities included, from individual coping techniques such as mindfulness training to social gatherings for the residents. In general, these wellness initiatives focus on burnout at the individual level, but they do not take into account systemic or structural challenges that might contribute to this worsening epidemic.

Final Thoughts

As a profession, I believe that physicians have internalized the concept of burnout to equate with a personal individual failing. At various times in my training, I have felt that if I could just practice mediation, study more, or shift my perspective, I personally could overcome burnout. I have intermittently felt my burnout as proof that I should never have become a physician. As a woman and the first physician in my family, fighting the sense of burnout so early in my career seemed demoralizing and nearly drove me to change my career path. It exacerbated my sense of imposter syndrome: that I never truly belonged in medicine at all. After much soul-searching, I have concluded that burnout is a concept propagated by administrators and businesspeople to stigmatize the reaction by many physicians to the growing trends in medicine and cast it as a personal failure rather than as the symptom of a broken medical system.

If we continue to identify burnout as an individual failing and treat it as such, I believe that we will fail to stem the growing trend within dermatology and within medicine more broadly. We need to consider the driving factors behind dermatology burnout so that we can begin to address them at a structural level.

Many articles about physician burnout and more alarmingly depression and suicide include chilling statistics; however, the data are limited. The same study from Medscape about burnout broken down by medical specialty often is cited.1 Although dermatology fares better than many specialties in this research, the percentages are still abysmal.

I am writing as a physician, for physicians. I do not want to quote the data to you. If you are reading this article, you have probably felt some burnout, even transiently. Maybe you even feel it now, at this very moment. Physicians are competitive capable people. I do not want to present numbers and statistics that make you question the validity of your feelings, whether you fit with the average statistics, or make you try to calculate how many of your friends or colleagues match these statistics. The numbers are terrible, no matter how you look at them, and all trends show them worsening with time.

What is burnout?

To simply define burnout as fatigue or high workload would be to undervalue the term. Physicians are trained through college, medical school, and countless hours of residency to cope with both challenges. Maslach et al2 defined burnout as “a psychological syndrome in response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” leading to “overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.”

Who does burnout affect?

Physician burnout affects both the patient and the physician. It has been demonstrated that physician burnout leads to lower patient satisfaction and care as well as higher risk for medical errors. There are the more obvious and direct effects on the physician, with affected physicians having much higher employment turnover and risk for addiction and suicide.3 One could argue that there are even more downstream effects of burnout, including physicians’ families who may be directly affected and even societal effects when fully trained physicians leave the clinical arena to pursue other careers.

How do you recognize when you are burnt out?

The first time I recognized that I was burnt out was in medical school. I understood my burnout through the lens of my undergraduate training in anthropology as compassion fatigue, a term that has been used to describe the lack of empathy that can develop when any individual is presented with an overwhelming tragedy or horror. When you are in survival mode—waking up just to survive the next day or clinic shift or call—you are surviving but hardly thriving as a physician.3 I believe that humans have a tremendous capacity for survival, but when we are in survival mode we have little energy leftover for the pleasures of life, from family to hobbies. I would similarly argue that in survival mode we have limited ability to appreciate the pain and suffering our patients are experiencing. Survival mode limits our ability as physicians to connect with our patients and to engage in the full spectrum of emotion in our time outside of our job.

What are the causes of burnout in dermatology?

As dermatologists, we often have milder on-call schedules and fewer critically ill patients than many of our medical colleagues. For this reason, we may be afraid to address the real role of physician burnout in our field. Fellow dermatologist Jeffrey Benabio, MD (San Diego, California), notes that the phrase dermatologist burnout may even seem oxymoronic, but we face many of the same daily frustrations with electronic medical records, increasing patient volume, and insurance struggles.4 The electronic medical record looms large in many physicians’ complaints these days. A recent article in the New York Times described the physician as “the highest-paid clerical worker in the hospital,”5 which is not wrong. For every hour of patient time, we have nearly double that spent on paperwork.5

Dike Drummond, MD, a family practice physician who focuses on physician burnout, notes that physicians are taught very early to put the patient first, but it is never discussed when or how to turn this switch off.3 However, there is little written about dermatology-specific burnout. A problem that is not studied or even considered will be harder to fix.

Why does it matter?

I believe that addressing physician burnout is critical for 2 reasons: (1) we can improve patient care by improving patient satisfaction and decreasing medical error, and (2) we can find greater satisfaction and professional fulfillment while caring for our patients. Ultimately, patient care and physician care are intimately linked; as stated by Thomas et al,6 “[p]hysicians who are well can best serve their patients.”

As a resident in 2018, I recognize that my coresidents and I are training as physicians in the time of “duty hours” and an ongoing discussion of burnout. However, I sense a burnout fatigue setting in among residents, many who do not want to discuss wellness anymore. The newer data suggest that work hour restrictions do not improve patient safety, negating one of the driving reasons for the change.7 At the same time, residency programs are initiating wellness programs in response to the growing literature on physician burnout. These wellness programs vary in the types of activities included, from individual coping techniques such as mindfulness training to social gatherings for the residents. In general, these wellness initiatives focus on burnout at the individual level, but they do not take into account systemic or structural challenges that might contribute to this worsening epidemic.

Final Thoughts

As a profession, I believe that physicians have internalized the concept of burnout to equate with a personal individual failing. At various times in my training, I have felt that if I could just practice mediation, study more, or shift my perspective, I personally could overcome burnout. I have intermittently felt my burnout as proof that I should never have become a physician. As a woman and the first physician in my family, fighting the sense of burnout so early in my career seemed demoralizing and nearly drove me to change my career path. It exacerbated my sense of imposter syndrome: that I never truly belonged in medicine at all. After much soul-searching, I have concluded that burnout is a concept propagated by administrators and businesspeople to stigmatize the reaction by many physicians to the growing trends in medicine and cast it as a personal failure rather than as the symptom of a broken medical system.

If we continue to identify burnout as an individual failing and treat it as such, I believe that we will fail to stem the growing trend within dermatology and within medicine more broadly. We need to consider the driving factors behind dermatology burnout so that we can begin to address them at a structural level.

- Peckham C. Medscape national physician burnout & depression report 2018. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6009235. Published January 17, 2018. Accessed June 21, 2018.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job

burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. - Drummond D. Physician burnout: its origin, symptoms, and five main causes. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22:42-47.

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed June 30, 2018.

- Verghese A. How tech can turn doctors into clerical workers. New York Times. May 16, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/05/16/magazine/health-issue-what-we-lose-with-data-driven-medicine.html. Accessed July 3, 2018.

- Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319:1541-1542.

- Osborne R, Parshuram CS. Delinking resident duty hours from patient safety [published online December 11, 2014]. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(suppl 1):S2.

- Peckham C. Medscape national physician burnout & depression report 2018. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6009235. Published January 17, 2018. Accessed June 21, 2018.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job

burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. - Drummond D. Physician burnout: its origin, symptoms, and five main causes. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22:42-47.

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed June 30, 2018.

- Verghese A. How tech can turn doctors into clerical workers. New York Times. May 16, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/05/16/magazine/health-issue-what-we-lose-with-data-driven-medicine.html. Accessed July 3, 2018.

- Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319:1541-1542.

- Osborne R, Parshuram CS. Delinking resident duty hours from patient safety [published online December 11, 2014]. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(suppl 1):S2.

Acne Medications: What Factors Drive Variable Costs?

Gottron Papules Mimicking Dermatomyositis: An Unusual Manifestation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

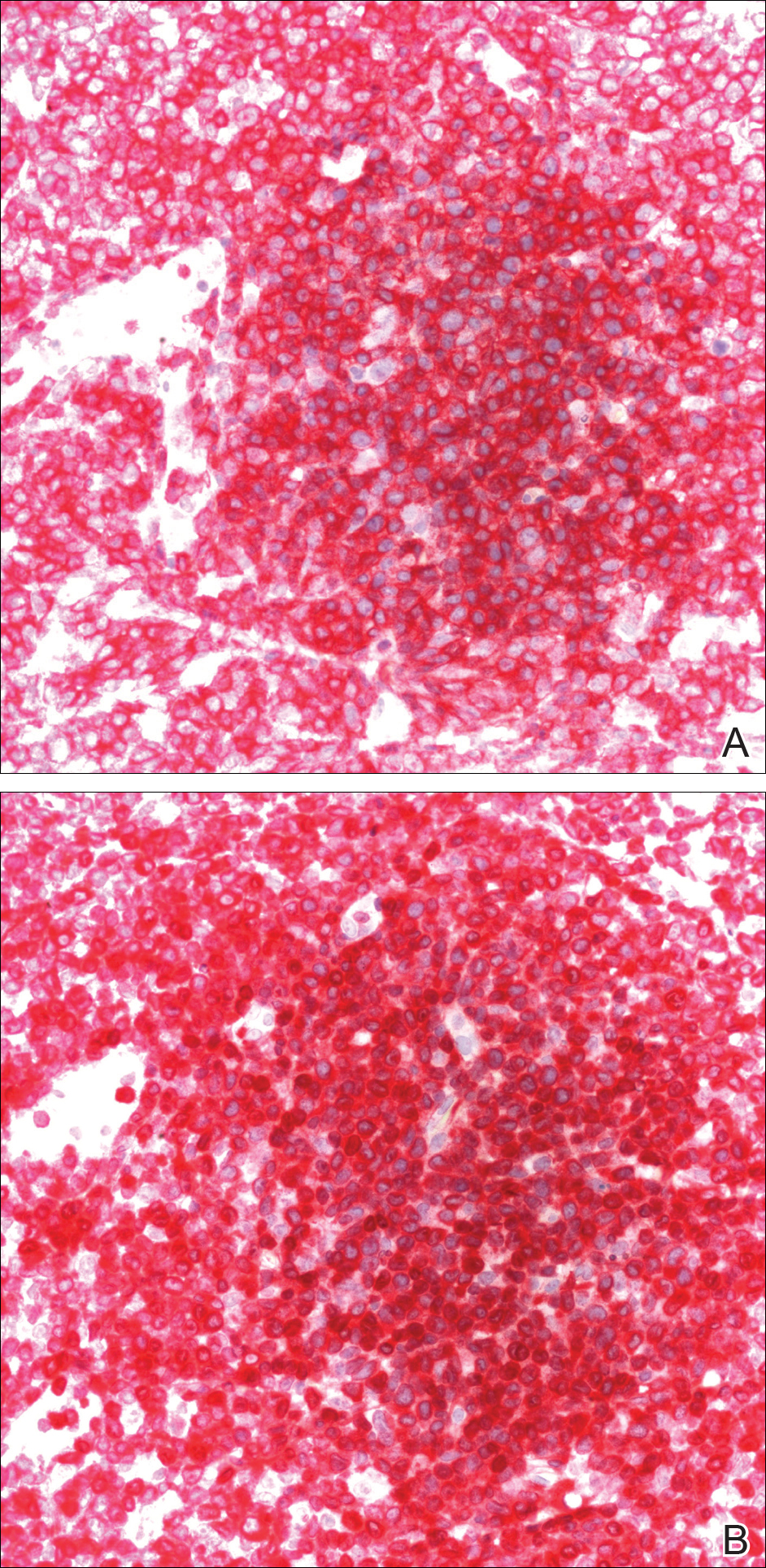

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

Practice Points

- Gottron-like papules can be a dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

- When present along with other findings of lupus erythematosus without any clinical manifestations of dermatomyositis, Gottron-like papules can be thought of as a manifestation of lupus erythematosus rather than dermatomyositis.

VIDEO: Look for Signs of Depression in Rosacea Patients

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Risk Stratification for Cellulitis Versus Noncellulitic Conditions of the Lower Extremity: A Retrospective Review of the NEW HAvUN Criteria

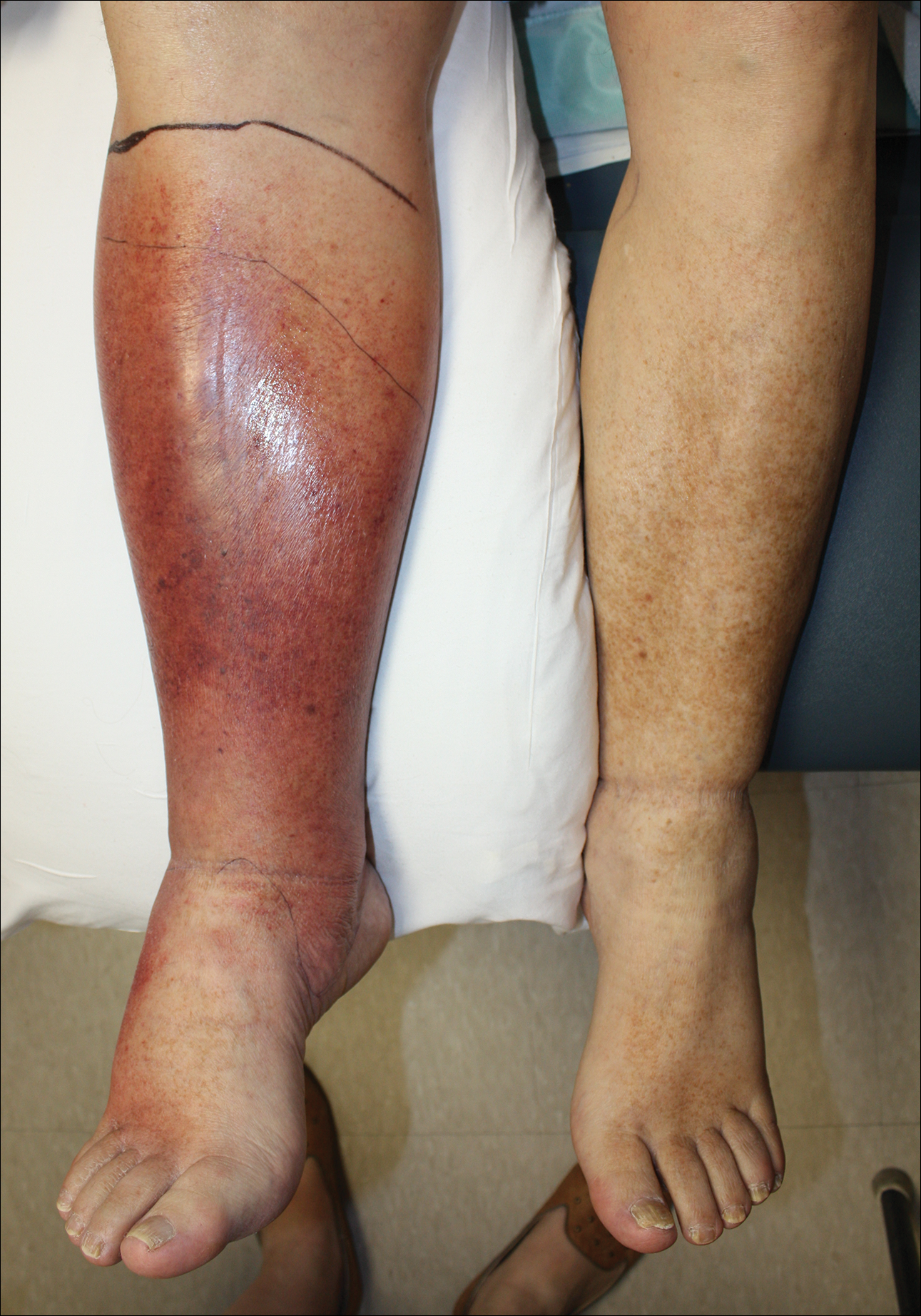

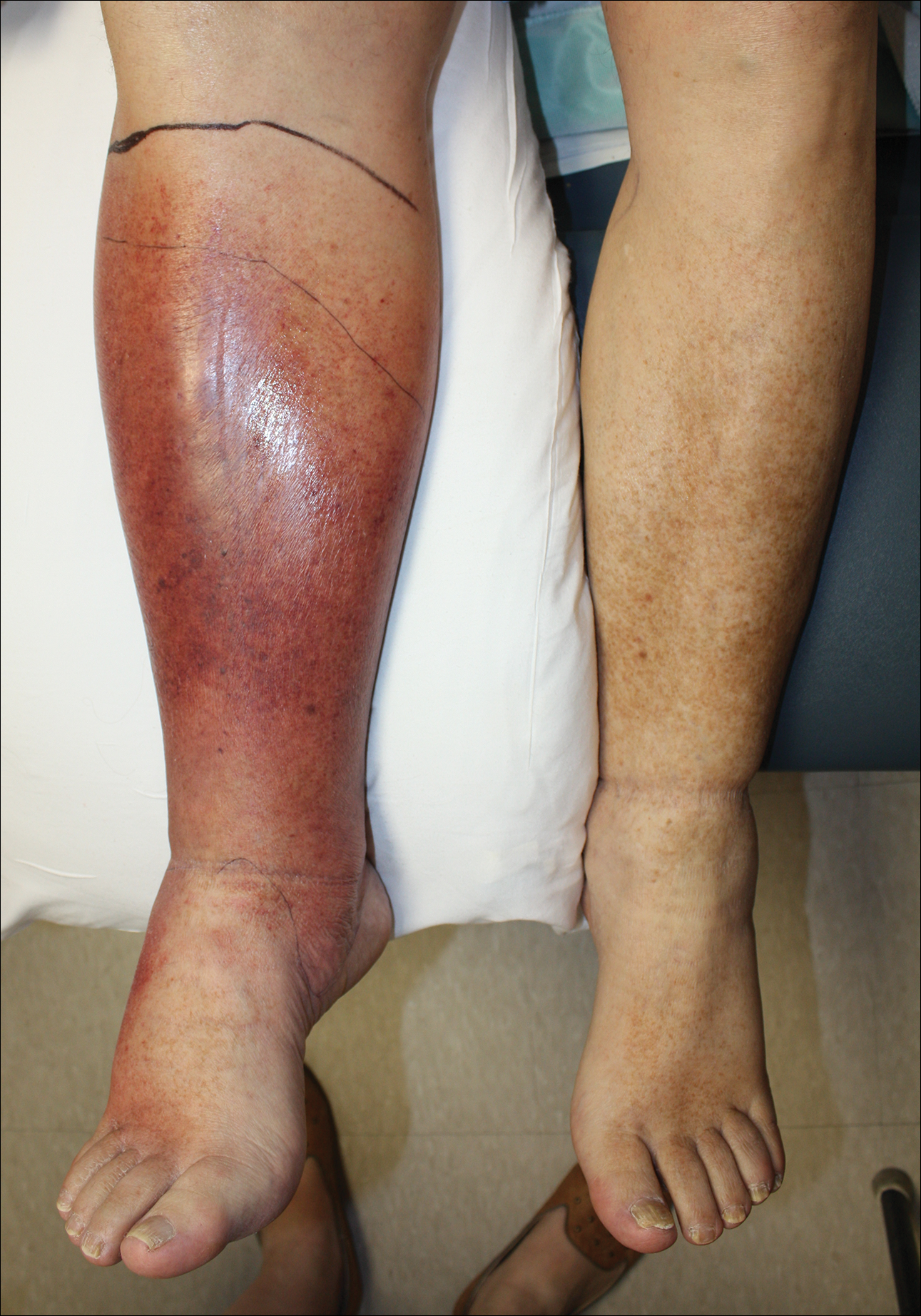

Cellulitis is defined as an acute or subacute, bacterial-induced inflammation of subcutaneous tissue that can extend superficially. The inciting incident often is assumed to be invasion of bacteria through loose connective tissue.1 Although cellulitis is bacterial in origin, it often is difficult to culture the offending microorganism from biopsy sites, swabs, or blood. Erythema, fever, induration, and tenderness are largely seen as clinical manifestations. Moderate and severe cases may be accompanied by fever, malaise, and leukocytosis. The lower extremity is the most common location of involvement (Figure 1), and usually a wound, ulcer, or interdigital superficial infection can be identified and implicated as the source of entry.

Effective treatment of cellulitis is necessary because complications such as abscesses, underlying fascia or muscle involvement, and septicemia can develop, leading to poor outcomes. Antibiotics should be administered intravenously in patients with suspected fascial involvement, septicemia, or dermal necrosis, or in those with an immunological comorbidity.2

The differential diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis is wide due to the existence of several mimicking dermatologic conditions. These so-called pseudocellulitis conditions include stasis dermatitis, venous ulceration, acute lipodermatosclerosis, pigmented purpura, vasculopathy, contact dermatitis, adverse medication reaction, and arthropod bite. Stasis dermatitis and lipodermatosclerosis, both arising from venous insufficiency, are by far 2 of the most common skin conditions that imitate cellulitis.

Stasis dermatitis is a common condition in the United States and Europe, usually manifesting as a pigmented purpuric dermatosis on anterior tibial surfaces, around the ankle, or overlying dependent varicosities. Skin changes can include hyperpigmentation, edema, mild scaling, eczematous patches, and even ulceration.3

Lipodermatosclerosis is a disorder of progressive fibrosis of subcutaneous fat. It is more common in middle-aged women who have a high body mass index and a venous abnormality.4 This form of panniculitis typically affects the lower extremities bilaterally, manifesting as erythematous and indurated skin changes, sometimes described as inverted champagne bottles (Figure 2). At times, there can be accompanying painful ulceration on the erythematous areas, features that closely resemble cellulitis.5,6 Lipodermatosclerosis is commonly misdiagnosed as cellulitis, leading to inappropriate prescription of antibiotics.7

Distinguishing cellulitis from noncellulitic conditions of the lower extremity is paramount to effective patient management in the emergent setting. With a reported incidence of 24.6 per 100 person-years, cellulitis constitutes 1% to 14% of emergency department visits and 4% to 7% of hospital admissions.Therefore, prompt appropriate diagnosis and treatment can avoid life-threatening complications associated with infection such as sepsis, abscess, lymphangitis, and necrotizing fasciitis.8-11

It is estimated that 10% to 20% of patients who have been given a diagnosis of cellulitis do not actually have the disease.2,12 This discrepancy consumes a remarkable amount of hospital resources and can lead to inappropriate or excessive use of antibiotics.13 Although the true incidence of adverse antibiotic reactions is unknown, it is estimated that they are the cause of 3% to 6% of acute hospital admissions and occur in 10% to 15% of inpatients admitted for other primary reasons.14 These findings illustrate the potential for an increased risk for morbidity and increased length of stay for patients beginning an antibiotic regimen, especially when the agents are administered unnecessarily. In addition, inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to antibiotic resistance, which continues to be a major problem, especially in hospitalized patients.

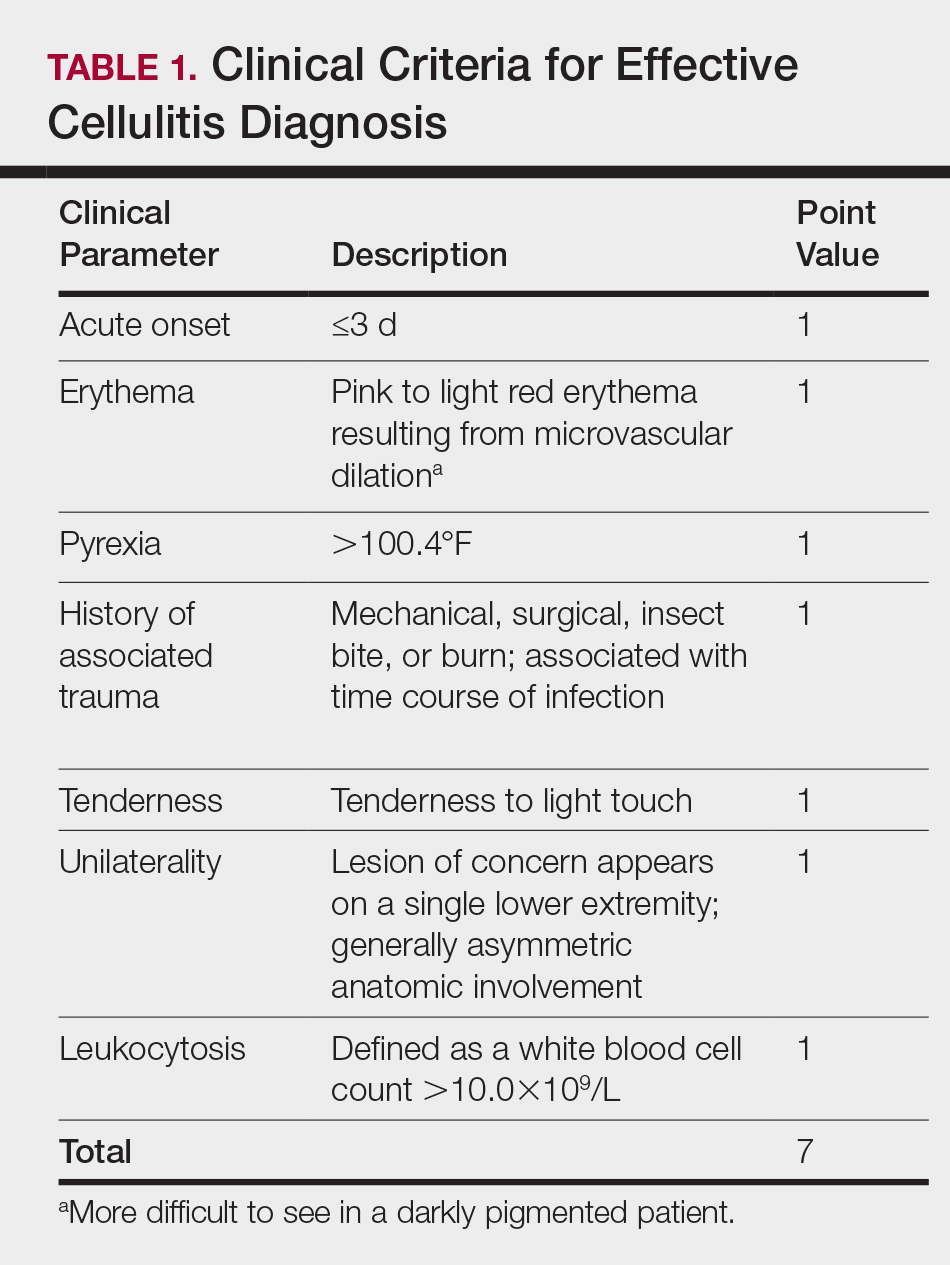

There is a lack of consensus in the literature about methods to risk stratify patients who present with acute dermatologic conditions that include and resemble cellulitis. We sought to identify clinical features based on available clinical literature-derived variables. We tested our scheme in a series of patients with a known diagnosis of cellulitis or other dermatologic pathology of the lower extremity to assess the validity of the following 7 clinical criteria: acute onset, erythema, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, tenderness, unilaterality, and leukocytosis.

Materials and Methods

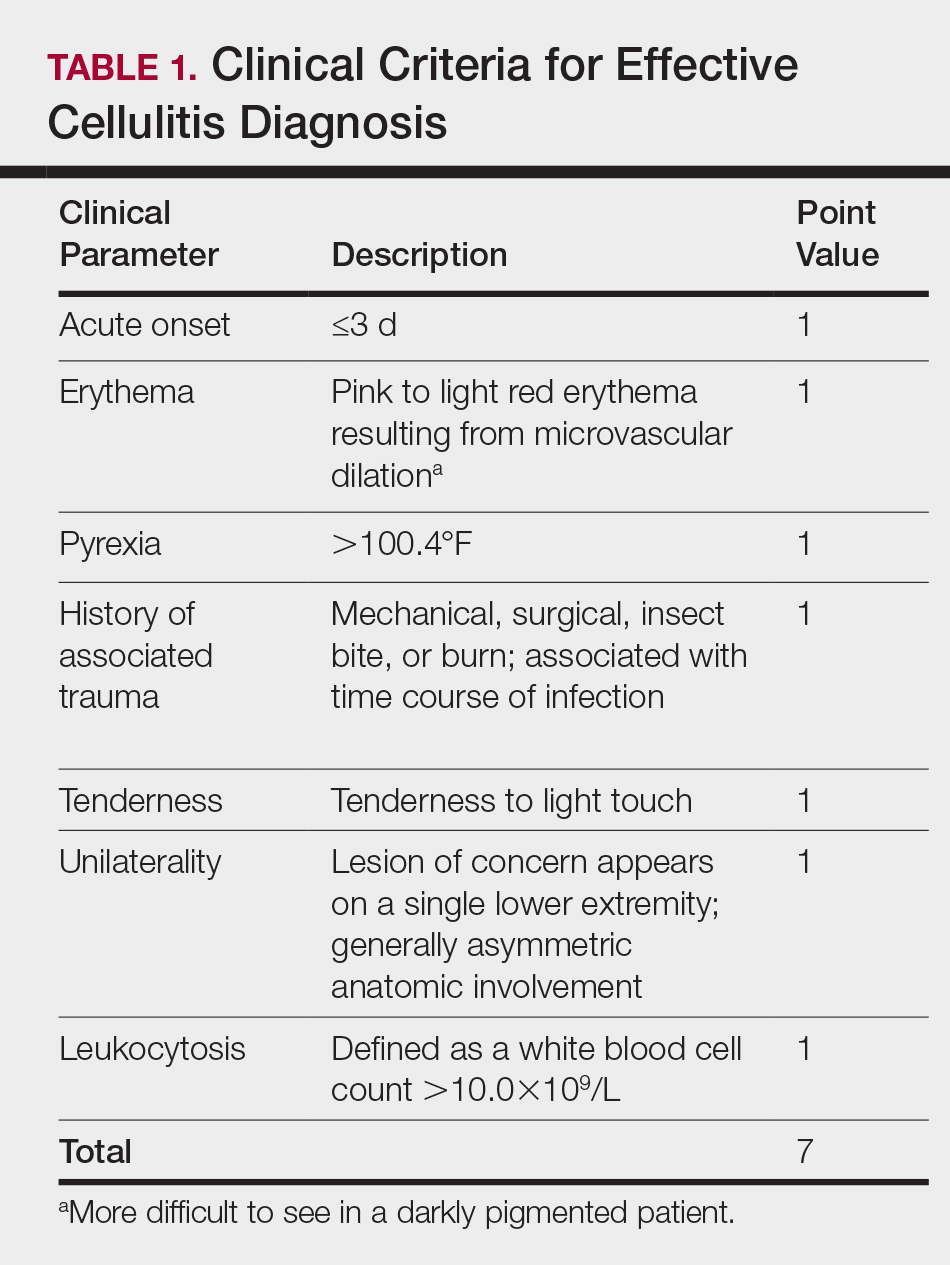

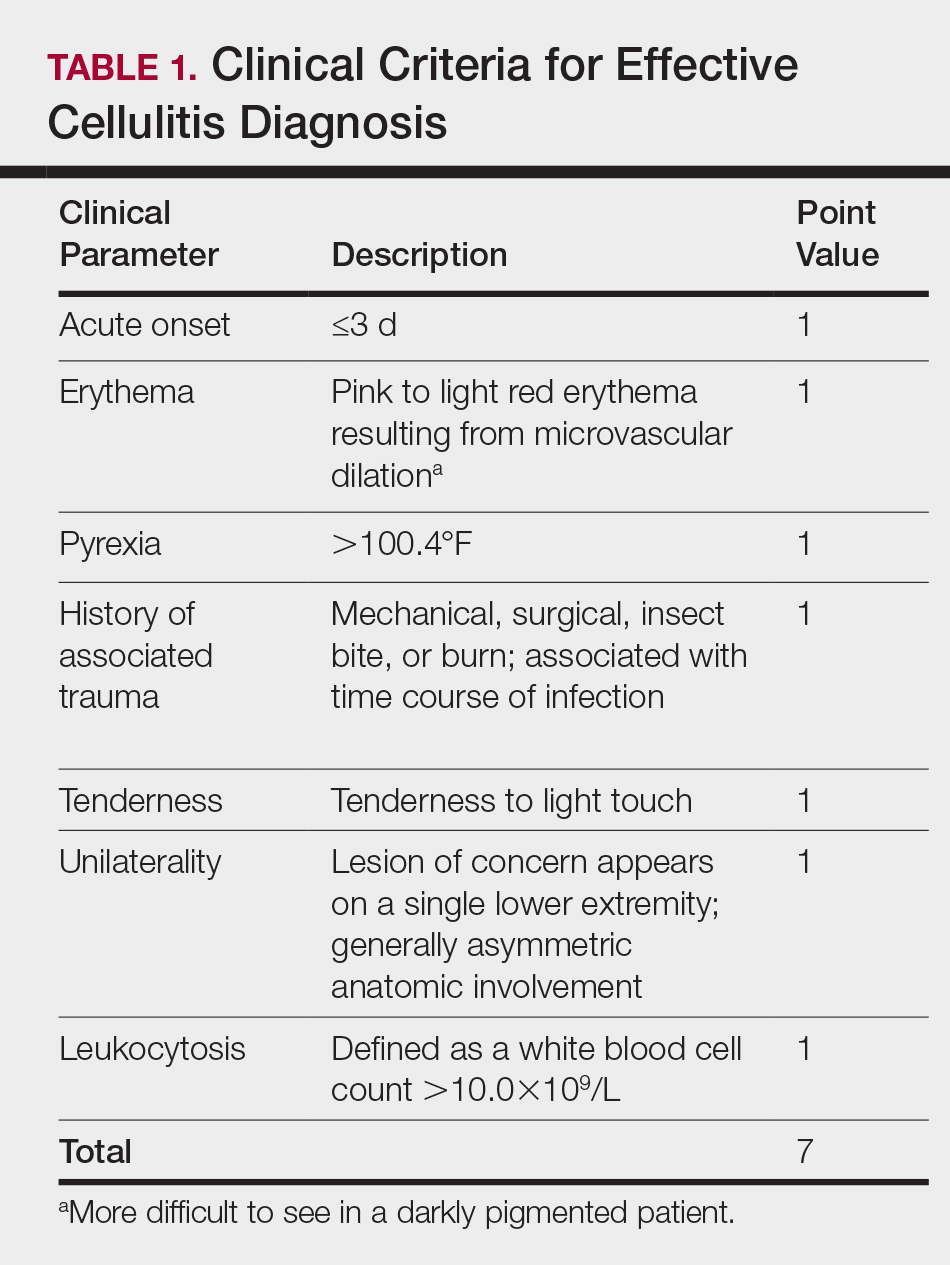

This retrospective chart review was approved by the Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut) institutional review board (HIC#1409014533). Final diagnosis, demographic data, clinical manifestations, and relevant diagnostic laboratory values of 57 patients were obtained from a database in the dermatology department’s consultation log and electronic medical record database (December 2011 to December 2014). The presence of each clinical symptom—acute onset, erythema, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, tenderness, unilaterality, and leukocytosis—was assigned a score equal to 1; values were tallied to achieve a final score for each patient (Table 1). Patients who were seen initially as a consultation for possible cellulitis but given a final diagnosis of stasis dermatitis or lipodermatosclerosis were included (Table 2).

Clinical Criteria

The clinical criteria were developed based largely on clinical experience and relevant secondary literature.15-17 At the patient encounter, presence of each of the variables (Table 1) was assessed according to the following definitions:

- acute onset: within the prior 72 hours and more indicative of an acute infective process than a gradual and chronic consequence of venous stasis

- erythema: a subjective clinical marker for inflammation that can be associated with cellulitis, though darker, erythematous-appearing discolorations also can be seen in patients with chronic venous hypertension or valvular incompetence4,15

- pyrexia: body temperature greater than 100.4°F

- history of associated trauma: encompassing mechanical wounds, surgical incisions, burns, and insect bites that correlate closely to the time course of symptomatic development

- tenderness: tenderness to light touch, which may be more common in patients afflicted with cellulitis than in those with venous insufficiency

- unilaterality: a helpful distinguishing feature that points the diagnosis away from a dermatitislike clinical picture, especially because bilateral cellulitis is rare and regarded as a diagnostic pitfall18

- leukocytosis: white blood cell count greater than 10.0×109/L and is reasonably considered a cardinal metric of inflammatory processes, though it can be confounded by immunocompromise (low count) or steroid use (high count)

Statistical Analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated and χ2 analysis was performed for each presenting symptom using JMP 10.0 analytical software (SAS Institute Inc). Each patient was rated separately by means of the clinical feature–based scoring system for the calculation of a total score. After application of the score to the patient population, receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed to identify the optimal score threshold for discriminating cellulitis from dermatitis in this group. For each clinical feature, P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

Our cohort included 32 male and 25 female patients with a mean age of 63 and 61 years, respectively. The final clinical diagnosis of cellulitis was made in 20 patients (35%). An established diagnosis of cellulitis was assigned based on a dermatology evaluation located within our electronic medical record database (Table 2).

Each clinical parameter was evaluated separately for each patient; combined results are summarized in Table 3. Acute onset (≤3 days) was a clinical characteristic seen in 80% (16/20) of cellulitis cases and 22% (8/37) of noncellulitis cases (OR, 14.5; P<.001). Erythema had similar significance (OR, 10.3; prevalence, 95% [19/20] vs 65% [24/37]; P=.012). Pyrexia possessed an OR of 99.2 for cellulitis and was seen in 85% (17/20) of cellulitis cases and only 5% (2/37) of noncellulitis cases (P<.001).

A history of associated trauma had an OR of 36.0 for cellulitis, with 50% (10/20) and 3% (1/37) prevalence in cellulitis cases and noncellulitis cases, respectively (P<.001). Tenderness, documented in 90% (18/20) of cellulitis cases and 43% (16/37) of noncellulitis cases, had an OR of 11.8 (P<.001).

Unilaterality had 100% (20/20) prevalence in our cellulitis cohort and was the only characteristic within the algorithm that yielded an incalculable OR. Noncellulitis or stasis dermatitis of the lower extremity exhibited a unilateral lesion in 11 cases (30%), of which 1 case resulted from a unilateral tibial fracture. Leukocytosis was seen in 65% (13/20) of cellulitis cases and 8% (3/37) of noncellulitis cases, with an OR for cellulitis of 21.0 (P<.001).

All parameters were significant by χ2 analysis (Table 3).

Comment

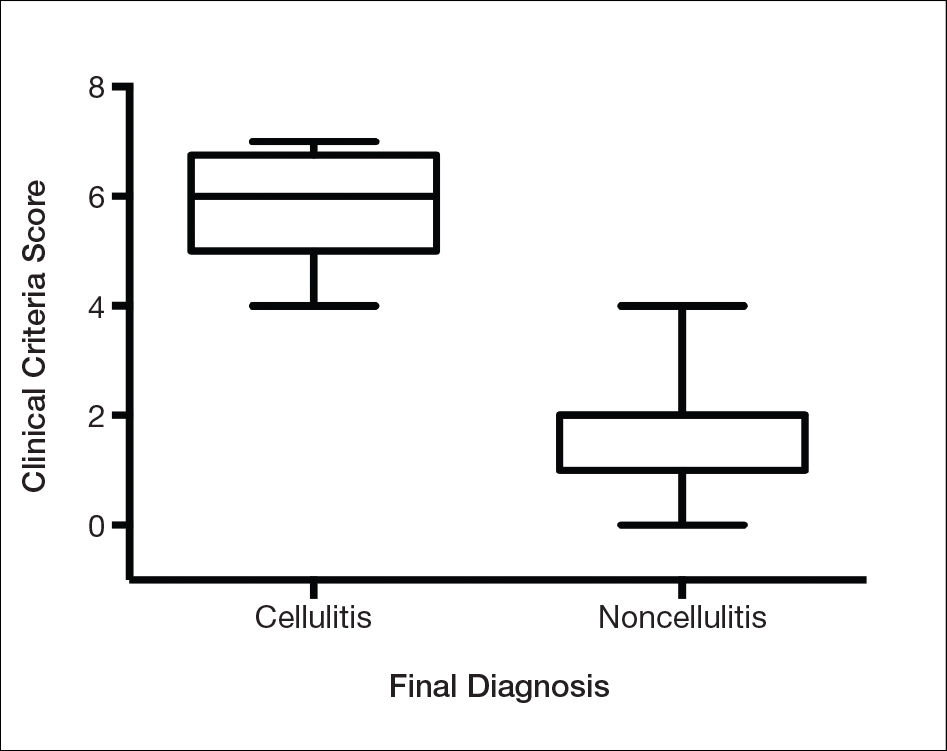

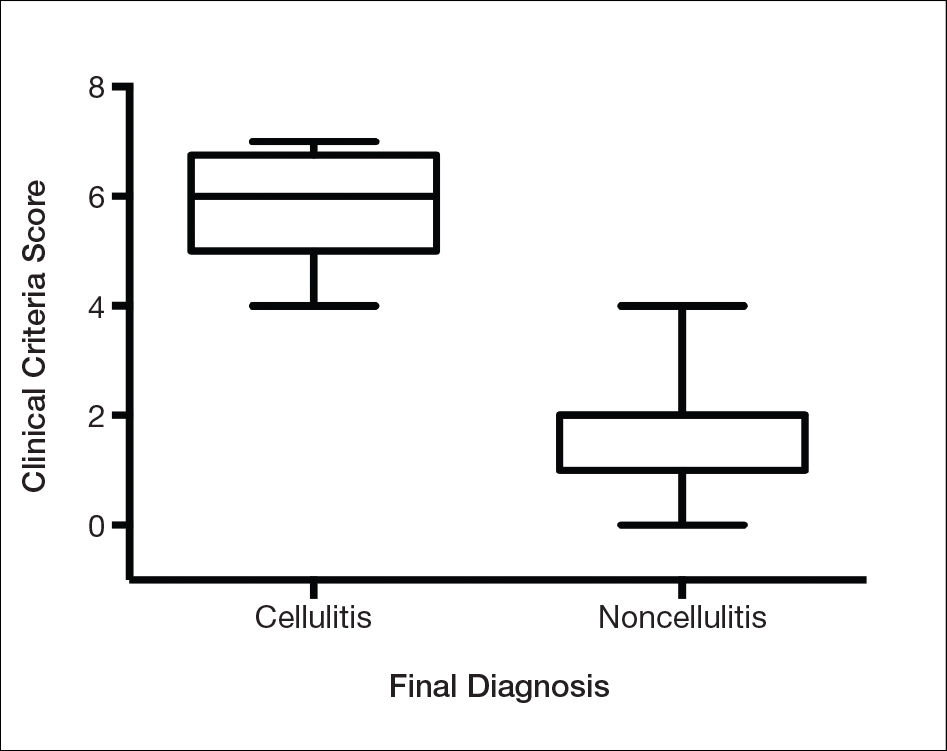

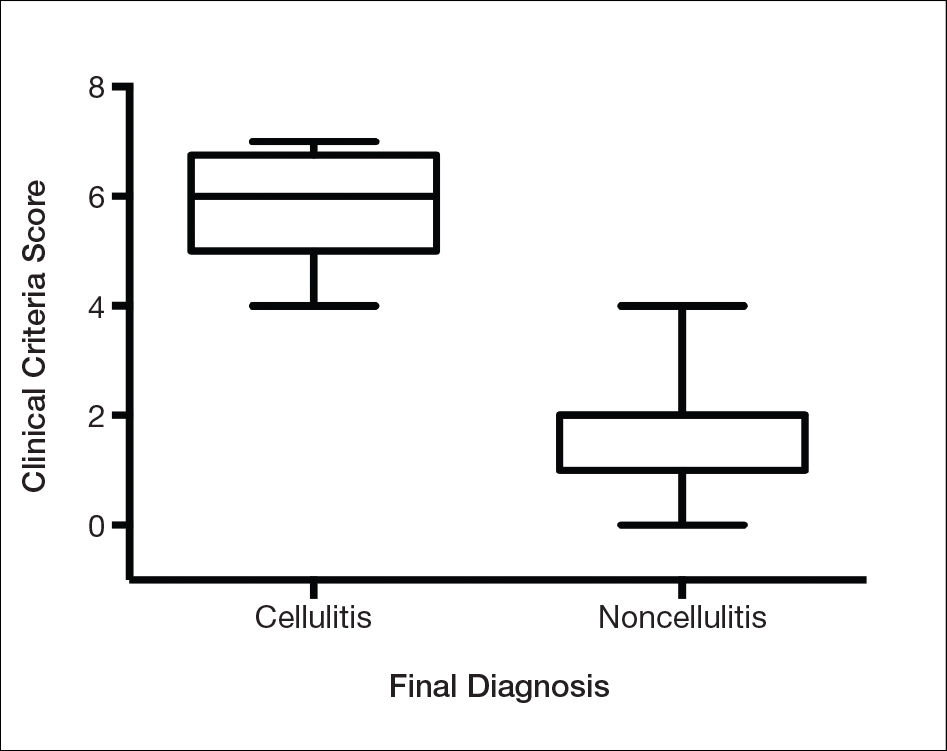

We found that testing positive for 4 of 7 clinical criteria for assessing cellulitis was highly specific (95%) and sensitive (100%) for a diagnosis of cellulitis among its range of mimics (Figure 3). These cellulitis criteria can be remembered, with some modification, using NEW HAvUN as a mnemonic device (New onset,

Consistent with the literature, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, and unilaterality also were predictors of cellulitis diagnosis. Unilaterality often is used as a diagnostic tool by dermatologist consultants when a patient lacks other criteria for cellulitis, so these findings are intuitive and consistent with our institutional experience. Interestingly, leukocytosis was seen in only 65% of cellulitis cases and 8% of noncellulitis cases and therefore might not serve as a sensitive independent predictor of a diagnosis of cellulitis, emphasizing the importance of the multifactorial scoring system we have put forward. Additionally, acuity of onset, erythema, and tenderness are not independently associated with cellulitis when assessing a patient because several of those findings are present in other dermatologic conditions of the lower extremity; when combined with the other criteria, however, these 3 findings can play a role in diagnosis.

Effective cellulitis diagnosis provides well-recognized challenges in the acute medical setting because many clinical mimics exist. The estimated rate of misdiagnosed cellulitis is certainly well-established: 30% to 75% in independent and multi-institutional studies. These studies also revealed that patients admitted for bilateral “cellulitis” overwhelmingly tended to be stasis clinical pictures.13,19

Cost implications from inappropriate diagnosis largely regard inappropriate antibiotic use and the potential for microbial resistance, with associated costs estimated to be more than $50 billion (2004 dollars).20,21 The true cost burden is extremely difficult to model or predict due to remarkable variations in the institutional misdiagnosis rate, prescribing pattern, and antibiotic cost and could represent avenues of further study. Misappropriation of antibiotics includes not only a monetary cost that encompasses all aspects of acute treatment and hospitalization but also an unquantifiable cost: human lives associated with the consequences of antibiotic resistance.

Conclusion

There is a lack of consensus or criteria for differentiating cellulitis from its most common clinical counterparts. Here, we propose a convenient clinical correlation system that we hope will lead to more efficient allocation of clinical resources, including antibiotics and hospital admissions, while lowering the incidence of adverse events and leading to better patient outcomes. We recognize that the small sample size of our study may limit broad application of these criteria, though we anticipate that further prospective studies can improve the diagnostic relevance and risk-assessment power of the NEW HAvUN criteria put forth here for assessing cellulitis in the acute medical setting.

Acknowledgement—Author H.H.E. recognizes the loving memory of Nadia Ezaldein for her profound influence on and motivation behind this research.

- Lep

pard BJ, Seal DV, Colman G, et al. The value of bacteriology and serology in the diagnosis of cellulitis and erysipelas. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112:559-567. - Hep

burn MJ, Dooley DP, Skidmore PJ, et al. Comparison of short-course (5 days) and standard (10 days) treatment for uncomplicated cellulitis. Arch Int Med. 2004;164:1669-1674. - Bergan JJ, Schmid-Schönbein GW, Smith PD, et al. Chronic venous disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:488-498.

- Bruc

e AJ, Bennett DD, Lohse CM, et al. Lipodermatosclerosis: review of cases evaluated at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:187-192. - Heym

ann WR. Lipodermatosclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1022-1023. - Vesi

ć S, Vuković J, Medenica LJ, et al. Acute lipodermatosclerosis: an open clinical trial of stanozolol in patients unable to sustain compression therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:1. - Keller

EC, Tomecki KJ, Alraies MC. Distinguishing cellulitis from its mimics. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:547-552. - Dong SL, Kelly KD, Oland RC, et al. ED management of cellulitis: a review of five urban centers. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:535-540.

- Ellis Simonsen SM, van Orman ER, Hatch BE, et al. Cellulitis incidence in a defined population. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:293-299.

- Manfredi R, Calza L, Chiodo F. Epidemiology and microbiology of cellulitis and bacterial soft tissue infection during HIV disease: a 10-year survey. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:168-172.

- Pascarella L, Schonbein GW, Bergan JJ. Microcirculation and venous ulcers: a review. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19:921-927.

- Hepburn MJ, Dooley DP, Ellis MW. Alternative diagnoses that often mimic cellulitis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2471.

- David CV, Chira S, Eells SJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy in patients admitted to hospitals with cellulitis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Hay RJ, Adriaans BM. Bacterial infections. In: Thong BY, Tan TC. Epidemiology and risk factors for drug allergy. 8th ed. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71:684-700.

- Hay RJ, Adriaans BM. Bacterial infections. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004:1345-1426.

- Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology In General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003.

- Sommer LL, Reboli AC, Heymann WR. Bacterial infections. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, et al. Dermatology. Vol 4. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1462-1502.

- Cox NH. Management of lower leg cellulitis. Clin Med. 2002;2:23-27.

- Strazzula L, Cotliar J, Fox LP, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation aids diagnosis of cellulitis among hospitalized patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:70-75.

- Pinder R, Sallis A, Berry D, et al. Behaviour change and antibiotic prescribing in healthcare settings: literature review and behavioural analysis. London, UK: Public Health England; February 2015. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/

uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/405031

/Behaviour_Change_for_Antibiotic_Prescribing_-_FINAL.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2018. - Smith R, Coast J. The true cost of antimicrobial resistance. BMJ. 2013;346:f1493.

Cellulitis is defined as an acute or subacute, bacterial-induced inflammation of subcutaneous tissue that can extend superficially. The inciting incident often is assumed to be invasion of bacteria through loose connective tissue.1 Although cellulitis is bacterial in origin, it often is difficult to culture the offending microorganism from biopsy sites, swabs, or blood. Erythema, fever, induration, and tenderness are largely seen as clinical manifestations. Moderate and severe cases may be accompanied by fever, malaise, and leukocytosis. The lower extremity is the most common location of involvement (Figure 1), and usually a wound, ulcer, or interdigital superficial infection can be identified and implicated as the source of entry.

Effective treatment of cellulitis is necessary because complications such as abscesses, underlying fascia or muscle involvement, and septicemia can develop, leading to poor outcomes. Antibiotics should be administered intravenously in patients with suspected fascial involvement, septicemia, or dermal necrosis, or in those with an immunological comorbidity.2

The differential diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis is wide due to the existence of several mimicking dermatologic conditions. These so-called pseudocellulitis conditions include stasis dermatitis, venous ulceration, acute lipodermatosclerosis, pigmented purpura, vasculopathy, contact dermatitis, adverse medication reaction, and arthropod bite. Stasis dermatitis and lipodermatosclerosis, both arising from venous insufficiency, are by far 2 of the most common skin conditions that imitate cellulitis.

Stasis dermatitis is a common condition in the United States and Europe, usually manifesting as a pigmented purpuric dermatosis on anterior tibial surfaces, around the ankle, or overlying dependent varicosities. Skin changes can include hyperpigmentation, edema, mild scaling, eczematous patches, and even ulceration.3

Lipodermatosclerosis is a disorder of progressive fibrosis of subcutaneous fat. It is more common in middle-aged women who have a high body mass index and a venous abnormality.4 This form of panniculitis typically affects the lower extremities bilaterally, manifesting as erythematous and indurated skin changes, sometimes described as inverted champagne bottles (Figure 2). At times, there can be accompanying painful ulceration on the erythematous areas, features that closely resemble cellulitis.5,6 Lipodermatosclerosis is commonly misdiagnosed as cellulitis, leading to inappropriate prescription of antibiotics.7

Distinguishing cellulitis from noncellulitic conditions of the lower extremity is paramount to effective patient management in the emergent setting. With a reported incidence of 24.6 per 100 person-years, cellulitis constitutes 1% to 14% of emergency department visits and 4% to 7% of hospital admissions.Therefore, prompt appropriate diagnosis and treatment can avoid life-threatening complications associated with infection such as sepsis, abscess, lymphangitis, and necrotizing fasciitis.8-11

It is estimated that 10% to 20% of patients who have been given a diagnosis of cellulitis do not actually have the disease.2,12 This discrepancy consumes a remarkable amount of hospital resources and can lead to inappropriate or excessive use of antibiotics.13 Although the true incidence of adverse antibiotic reactions is unknown, it is estimated that they are the cause of 3% to 6% of acute hospital admissions and occur in 10% to 15% of inpatients admitted for other primary reasons.14 These findings illustrate the potential for an increased risk for morbidity and increased length of stay for patients beginning an antibiotic regimen, especially when the agents are administered unnecessarily. In addition, inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to antibiotic resistance, which continues to be a major problem, especially in hospitalized patients.

There is a lack of consensus in the literature about methods to risk stratify patients who present with acute dermatologic conditions that include and resemble cellulitis. We sought to identify clinical features based on available clinical literature-derived variables. We tested our scheme in a series of patients with a known diagnosis of cellulitis or other dermatologic pathology of the lower extremity to assess the validity of the following 7 clinical criteria: acute onset, erythema, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, tenderness, unilaterality, and leukocytosis.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective chart review was approved by the Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut) institutional review board (HIC#1409014533). Final diagnosis, demographic data, clinical manifestations, and relevant diagnostic laboratory values of 57 patients were obtained from a database in the dermatology department’s consultation log and electronic medical record database (December 2011 to December 2014). The presence of each clinical symptom—acute onset, erythema, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, tenderness, unilaterality, and leukocytosis—was assigned a score equal to 1; values were tallied to achieve a final score for each patient (Table 1). Patients who were seen initially as a consultation for possible cellulitis but given a final diagnosis of stasis dermatitis or lipodermatosclerosis were included (Table 2).

Clinical Criteria

The clinical criteria were developed based largely on clinical experience and relevant secondary literature.15-17 At the patient encounter, presence of each of the variables (Table 1) was assessed according to the following definitions:

- acute onset: within the prior 72 hours and more indicative of an acute infective process than a gradual and chronic consequence of venous stasis

- erythema: a subjective clinical marker for inflammation that can be associated with cellulitis, though darker, erythematous-appearing discolorations also can be seen in patients with chronic venous hypertension or valvular incompetence4,15

- pyrexia: body temperature greater than 100.4°F

- history of associated trauma: encompassing mechanical wounds, surgical incisions, burns, and insect bites that correlate closely to the time course of symptomatic development

- tenderness: tenderness to light touch, which may be more common in patients afflicted with cellulitis than in those with venous insufficiency

- unilaterality: a helpful distinguishing feature that points the diagnosis away from a dermatitislike clinical picture, especially because bilateral cellulitis is rare and regarded as a diagnostic pitfall18

- leukocytosis: white blood cell count greater than 10.0×109/L and is reasonably considered a cardinal metric of inflammatory processes, though it can be confounded by immunocompromise (low count) or steroid use (high count)

Statistical Analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated and χ2 analysis was performed for each presenting symptom using JMP 10.0 analytical software (SAS Institute Inc). Each patient was rated separately by means of the clinical feature–based scoring system for the calculation of a total score. After application of the score to the patient population, receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed to identify the optimal score threshold for discriminating cellulitis from dermatitis in this group. For each clinical feature, P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

Our cohort included 32 male and 25 female patients with a mean age of 63 and 61 years, respectively. The final clinical diagnosis of cellulitis was made in 20 patients (35%). An established diagnosis of cellulitis was assigned based on a dermatology evaluation located within our electronic medical record database (Table 2).

Each clinical parameter was evaluated separately for each patient; combined results are summarized in Table 3. Acute onset (≤3 days) was a clinical characteristic seen in 80% (16/20) of cellulitis cases and 22% (8/37) of noncellulitis cases (OR, 14.5; P<.001). Erythema had similar significance (OR, 10.3; prevalence, 95% [19/20] vs 65% [24/37]; P=.012). Pyrexia possessed an OR of 99.2 for cellulitis and was seen in 85% (17/20) of cellulitis cases and only 5% (2/37) of noncellulitis cases (P<.001).

A history of associated trauma had an OR of 36.0 for cellulitis, with 50% (10/20) and 3% (1/37) prevalence in cellulitis cases and noncellulitis cases, respectively (P<.001). Tenderness, documented in 90% (18/20) of cellulitis cases and 43% (16/37) of noncellulitis cases, had an OR of 11.8 (P<.001).

Unilaterality had 100% (20/20) prevalence in our cellulitis cohort and was the only characteristic within the algorithm that yielded an incalculable OR. Noncellulitis or stasis dermatitis of the lower extremity exhibited a unilateral lesion in 11 cases (30%), of which 1 case resulted from a unilateral tibial fracture. Leukocytosis was seen in 65% (13/20) of cellulitis cases and 8% (3/37) of noncellulitis cases, with an OR for cellulitis of 21.0 (P<.001).

All parameters were significant by χ2 analysis (Table 3).

Comment

We found that testing positive for 4 of 7 clinical criteria for assessing cellulitis was highly specific (95%) and sensitive (100%) for a diagnosis of cellulitis among its range of mimics (Figure 3). These cellulitis criteria can be remembered, with some modification, using NEW HAvUN as a mnemonic device (New onset,

Consistent with the literature, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, and unilaterality also were predictors of cellulitis diagnosis. Unilaterality often is used as a diagnostic tool by dermatologist consultants when a patient lacks other criteria for cellulitis, so these findings are intuitive and consistent with our institutional experience. Interestingly, leukocytosis was seen in only 65% of cellulitis cases and 8% of noncellulitis cases and therefore might not serve as a sensitive independent predictor of a diagnosis of cellulitis, emphasizing the importance of the multifactorial scoring system we have put forward. Additionally, acuity of onset, erythema, and tenderness are not independently associated with cellulitis when assessing a patient because several of those findings are present in other dermatologic conditions of the lower extremity; when combined with the other criteria, however, these 3 findings can play a role in diagnosis.

Effective cellulitis diagnosis provides well-recognized challenges in the acute medical setting because many clinical mimics exist. The estimated rate of misdiagnosed cellulitis is certainly well-established: 30% to 75% in independent and multi-institutional studies. These studies also revealed that patients admitted for bilateral “cellulitis” overwhelmingly tended to be stasis clinical pictures.13,19

Cost implications from inappropriate diagnosis largely regard inappropriate antibiotic use and the potential for microbial resistance, with associated costs estimated to be more than $50 billion (2004 dollars).20,21 The true cost burden is extremely difficult to model or predict due to remarkable variations in the institutional misdiagnosis rate, prescribing pattern, and antibiotic cost and could represent avenues of further study. Misappropriation of antibiotics includes not only a monetary cost that encompasses all aspects of acute treatment and hospitalization but also an unquantifiable cost: human lives associated with the consequences of antibiotic resistance.

Conclusion

There is a lack of consensus or criteria for differentiating cellulitis from its most common clinical counterparts. Here, we propose a convenient clinical correlation system that we hope will lead to more efficient allocation of clinical resources, including antibiotics and hospital admissions, while lowering the incidence of adverse events and leading to better patient outcomes. We recognize that the small sample size of our study may limit broad application of these criteria, though we anticipate that further prospective studies can improve the diagnostic relevance and risk-assessment power of the NEW HAvUN criteria put forth here for assessing cellulitis in the acute medical setting.

Acknowledgement—Author H.H.E. recognizes the loving memory of Nadia Ezaldein for her profound influence on and motivation behind this research.

Cellulitis is defined as an acute or subacute, bacterial-induced inflammation of subcutaneous tissue that can extend superficially. The inciting incident often is assumed to be invasion of bacteria through loose connective tissue.1 Although cellulitis is bacterial in origin, it often is difficult to culture the offending microorganism from biopsy sites, swabs, or blood. Erythema, fever, induration, and tenderness are largely seen as clinical manifestations. Moderate and severe cases may be accompanied by fever, malaise, and leukocytosis. The lower extremity is the most common location of involvement (Figure 1), and usually a wound, ulcer, or interdigital superficial infection can be identified and implicated as the source of entry.

Effective treatment of cellulitis is necessary because complications such as abscesses, underlying fascia or muscle involvement, and septicemia can develop, leading to poor outcomes. Antibiotics should be administered intravenously in patients with suspected fascial involvement, septicemia, or dermal necrosis, or in those with an immunological comorbidity.2

The differential diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis is wide due to the existence of several mimicking dermatologic conditions. These so-called pseudocellulitis conditions include stasis dermatitis, venous ulceration, acute lipodermatosclerosis, pigmented purpura, vasculopathy, contact dermatitis, adverse medication reaction, and arthropod bite. Stasis dermatitis and lipodermatosclerosis, both arising from venous insufficiency, are by far 2 of the most common skin conditions that imitate cellulitis.