User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Providing culturally competent postpartum care for South Asian women

As do women from a wide range of cultures, South Asian (SA) women frequently report feelings of shame associated with receiving a psychiatric diagnosis during the postpartum period because they fear it may reflect poorly on their ability to be good mothers or negatively impact their family’s

Be aware of psychosomatic presentations. SA mothers who develop postpartum psychiatric symptoms might not present with complaints of dysphoria, crying, low energy, or suicidal thoughts. They may instead describe psychosomatic symptoms such as headaches and body pains.

Consider their hesitation to use psychiatric terms. SA women may not be comfortable using psychiatric terms such as depression or anxiety. Instead, they might respond more positively when their preferred descriptive terms (ie, sadness, worry, stress) are used by the clinicians who treat them.

Engage the partner and/or family. SA women may emphasize that they are part of a family unit, rather than regarding themselves as individuals. Thus, including family members in the treatment plan may help improve adherence.

Screen for suicide risk. Evidence suggests that young SA women have a higher rate of suicide and suicide attempts than young SA men or non-SA women.1,2 Further, they may be less willing to speak openly about it.

Ask questions about cultural or traditional forms of treatment. SA mothers, particularly those who are breastfeeding, might be wary of Western medicine and may be familiar with traditional Indian medicine practices such as herbal, homeopathic, or Ayurvedic approaches.3 These interventions may include a specified diet, use of herbal treatments, exercise, and lifestyle recommendations.When taking the patient’s history, find out which treatments she is currently using, and discuss whether she can safely continue to use them.

Do not mistake poor eye contact for lack of engagement. Because SA patients may view a physician as a source of authority, they might regard direct eye contact with a physician as being somewhat disrespectful, and they may avoid eye contact altogether.

Continue to: Maintain an active approach

Maintain an active approach. SA women may prefer to view the physician as an expert, rather than a partner with whom to develop a collaborative relationship. Thus, they may feel more comfortable with direct feedback rather than a passive or reflective approach.

Suggest a postpartum support group. In a U.K. study of 17 SA postpartum women, age 20 to 45, group therapy improved health outcomes and overall satisfaction.4 It may be particularly helpful to SA patients if group therapy is facilitated by a culturally sensitive moderator.

Help patients overcome logistical barriers. Lack of transportation, childcare difficulties, and financial limitations are common deterrents to treatment. These barriers may be particularly challenging for SA women of lower socioeconomic status. Postpartum mothers who feel overtasked with caring for their children and undertaking household duties may feel less able to complete therapy.

Screen for adherence. Although SA patients may view clinicians as authority figures, adherence with medications or treatment plans should not be assumed. Many patients may quietly avoid treatments or recommendations instead of discussing their ambivalence with their clinicians.

1. Anand AS, Cochrane R. The mental health status of South Asian women in Britain. A review of the UK literature. Psychol Dev Soc J. 2005;17(2):195-214.

2. Bhugra D, Desai M. Attempted suicide in South Asian women. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2002;8(6):418-423.

3. Chopra A, Doiphode VV. Ayurvedic medicine. Core concept, therapeutic principles, and current relevance. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86(1):75-89,vii.

4. Masood Y, Lovell K, Lunat F, et al. Group psychological intervention for postnatal depression: a nested qualitative study with British South Asian women. BMC Womens Health. 2015;25(15):109.

As do women from a wide range of cultures, South Asian (SA) women frequently report feelings of shame associated with receiving a psychiatric diagnosis during the postpartum period because they fear it may reflect poorly on their ability to be good mothers or negatively impact their family’s

Be aware of psychosomatic presentations. SA mothers who develop postpartum psychiatric symptoms might not present with complaints of dysphoria, crying, low energy, or suicidal thoughts. They may instead describe psychosomatic symptoms such as headaches and body pains.

Consider their hesitation to use psychiatric terms. SA women may not be comfortable using psychiatric terms such as depression or anxiety. Instead, they might respond more positively when their preferred descriptive terms (ie, sadness, worry, stress) are used by the clinicians who treat them.

Engage the partner and/or family. SA women may emphasize that they are part of a family unit, rather than regarding themselves as individuals. Thus, including family members in the treatment plan may help improve adherence.

Screen for suicide risk. Evidence suggests that young SA women have a higher rate of suicide and suicide attempts than young SA men or non-SA women.1,2 Further, they may be less willing to speak openly about it.

Ask questions about cultural or traditional forms of treatment. SA mothers, particularly those who are breastfeeding, might be wary of Western medicine and may be familiar with traditional Indian medicine practices such as herbal, homeopathic, or Ayurvedic approaches.3 These interventions may include a specified diet, use of herbal treatments, exercise, and lifestyle recommendations.When taking the patient’s history, find out which treatments she is currently using, and discuss whether she can safely continue to use them.

Do not mistake poor eye contact for lack of engagement. Because SA patients may view a physician as a source of authority, they might regard direct eye contact with a physician as being somewhat disrespectful, and they may avoid eye contact altogether.

Continue to: Maintain an active approach

Maintain an active approach. SA women may prefer to view the physician as an expert, rather than a partner with whom to develop a collaborative relationship. Thus, they may feel more comfortable with direct feedback rather than a passive or reflective approach.

Suggest a postpartum support group. In a U.K. study of 17 SA postpartum women, age 20 to 45, group therapy improved health outcomes and overall satisfaction.4 It may be particularly helpful to SA patients if group therapy is facilitated by a culturally sensitive moderator.

Help patients overcome logistical barriers. Lack of transportation, childcare difficulties, and financial limitations are common deterrents to treatment. These barriers may be particularly challenging for SA women of lower socioeconomic status. Postpartum mothers who feel overtasked with caring for their children and undertaking household duties may feel less able to complete therapy.

Screen for adherence. Although SA patients may view clinicians as authority figures, adherence with medications or treatment plans should not be assumed. Many patients may quietly avoid treatments or recommendations instead of discussing their ambivalence with their clinicians.

As do women from a wide range of cultures, South Asian (SA) women frequently report feelings of shame associated with receiving a psychiatric diagnosis during the postpartum period because they fear it may reflect poorly on their ability to be good mothers or negatively impact their family’s

Be aware of psychosomatic presentations. SA mothers who develop postpartum psychiatric symptoms might not present with complaints of dysphoria, crying, low energy, or suicidal thoughts. They may instead describe psychosomatic symptoms such as headaches and body pains.

Consider their hesitation to use psychiatric terms. SA women may not be comfortable using psychiatric terms such as depression or anxiety. Instead, they might respond more positively when their preferred descriptive terms (ie, sadness, worry, stress) are used by the clinicians who treat them.

Engage the partner and/or family. SA women may emphasize that they are part of a family unit, rather than regarding themselves as individuals. Thus, including family members in the treatment plan may help improve adherence.

Screen for suicide risk. Evidence suggests that young SA women have a higher rate of suicide and suicide attempts than young SA men or non-SA women.1,2 Further, they may be less willing to speak openly about it.

Ask questions about cultural or traditional forms of treatment. SA mothers, particularly those who are breastfeeding, might be wary of Western medicine and may be familiar with traditional Indian medicine practices such as herbal, homeopathic, or Ayurvedic approaches.3 These interventions may include a specified diet, use of herbal treatments, exercise, and lifestyle recommendations.When taking the patient’s history, find out which treatments she is currently using, and discuss whether she can safely continue to use them.

Do not mistake poor eye contact for lack of engagement. Because SA patients may view a physician as a source of authority, they might regard direct eye contact with a physician as being somewhat disrespectful, and they may avoid eye contact altogether.

Continue to: Maintain an active approach

Maintain an active approach. SA women may prefer to view the physician as an expert, rather than a partner with whom to develop a collaborative relationship. Thus, they may feel more comfortable with direct feedback rather than a passive or reflective approach.

Suggest a postpartum support group. In a U.K. study of 17 SA postpartum women, age 20 to 45, group therapy improved health outcomes and overall satisfaction.4 It may be particularly helpful to SA patients if group therapy is facilitated by a culturally sensitive moderator.

Help patients overcome logistical barriers. Lack of transportation, childcare difficulties, and financial limitations are common deterrents to treatment. These barriers may be particularly challenging for SA women of lower socioeconomic status. Postpartum mothers who feel overtasked with caring for their children and undertaking household duties may feel less able to complete therapy.

Screen for adherence. Although SA patients may view clinicians as authority figures, adherence with medications or treatment plans should not be assumed. Many patients may quietly avoid treatments or recommendations instead of discussing their ambivalence with their clinicians.

1. Anand AS, Cochrane R. The mental health status of South Asian women in Britain. A review of the UK literature. Psychol Dev Soc J. 2005;17(2):195-214.

2. Bhugra D, Desai M. Attempted suicide in South Asian women. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2002;8(6):418-423.

3. Chopra A, Doiphode VV. Ayurvedic medicine. Core concept, therapeutic principles, and current relevance. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86(1):75-89,vii.

4. Masood Y, Lovell K, Lunat F, et al. Group psychological intervention for postnatal depression: a nested qualitative study with British South Asian women. BMC Womens Health. 2015;25(15):109.

1. Anand AS, Cochrane R. The mental health status of South Asian women in Britain. A review of the UK literature. Psychol Dev Soc J. 2005;17(2):195-214.

2. Bhugra D, Desai M. Attempted suicide in South Asian women. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2002;8(6):418-423.

3. Chopra A, Doiphode VV. Ayurvedic medicine. Core concept, therapeutic principles, and current relevance. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86(1):75-89,vii.

4. Masood Y, Lovell K, Lunat F, et al. Group psychological intervention for postnatal depression: a nested qualitative study with British South Asian women. BMC Womens Health. 2015;25(15):109.

Paliperidone palmitate: Adjusting dosing intervals and measuring serum concentrations

Mr. B, age 27, has a 10-year history of schizophrenia. Last year, he was doing well and working 4 hours/day 3 days/week while taking oral risperidone, 6 mg, at bedtime. However, during the past 2 weeks Mr. B began to have a return of auditory hallucinations and reports that he stopped taking his medication again 6 weeks ago.

As a result, he is started on paliperidone palmitate following the product label’s initiation dosing recommendation. On the first day he is given the first dose of the initiation regimen, 234 mg IM. One week later, the second dose of the initiation regimen, 156 mg IM, is given. One month later, the first maintenance dose of 117 mg IM every 28 days is given. All injections are in his deltoid muscle at his request.

After 3 weeks on the first maintenance dose of 117 mg, the voices begin to bother him again. Subsequently, Mr. B’s maintenance dose is increased first to 156 mg, and for the same problem with breakthrough hallucinations the following month to 234 mg, the maximum dose in the product label. After 6 months of receiving 234 mg IM every 28 days, the auditory hallucinations continue to bother him, but only for a few days prior to his next injection. He misses work 1 or 2 times before each injection.

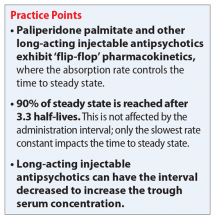

Can the injection frequency for Mr. B’s paliperidone palmitate, 234 mg IM, in the deltoid muscle be increased to every 21 days to prevent the monthly exacerbations? Yes, the injection frequency can be increased, and doing so will increase the concentrations of paliperidone. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) is complicated by the lengthy time needed to reach steady state. In the case of paliperidone palmitate, an initiation regimen was developed that achieves therapeutic concentrations that are close to steady state before the oral antipsychotic’s effects are lost. This initiation strategy avoids the need for oral supplementation to maintain clinical efficacy. However, even using an initiation regimen or a loading dose does not decrease the time to final steady state after a dose adjustment due to the slow absorption of the medication from the injection site. The time to steady state is controlled by “flip-flop” pharmacokinetics. In this kind of pharmacokinetics, which is observed with all LAIs, the absorption rate from the injection site is lower than the elimination rate.1

Cleton et al2 reported the pharmacokinetics of paliperidone palmitate for deltoid and gluteal injection sites. By combining the median data for the deltoid injection route from the article by Cleton et al2 and the dosing from Mr. B’s case, I created a model using superposition of a sixth-degree polynomial fitted to the single dose data. Gluteal injections were not included because their increased complexity is beyond the scope of this article, but the time to maximum concentration (gluteal > deltoid) and peak concentration (deltoid > gluteal) are different for each route. The polynomial was a good fit with the adjusted r2 = 0.976, P < .0001. This model illustrates the paliperidone serum concentrations for Mr. B and is shown in the Figure. As you can see, by Day 9, the serum concentrations had reached the lower limit of the expected range of 20 to 60 ng/mL, shown in the shaded region of the Figure.3

Steady state at the routine maintenance dose of 117 mg every 28 days was never reached as the medication was not sufficient to suppress Mr. B’s hallucinations, and his doses needed to be increased each month. First, Mr. B’s dose was increased to 156 mg and then to the maximum recommended dose of 234 mg every 28 days. Steady state can be considered to have been achieved when 90% of the final steady state is reached after 3.3 half-lives. Because of the flip-flop pharmacokinetics, the important half-life is the absorption half-life of approximately 40 days or 132 days at the same dose. In Mr. B’s case, this was Day 221, where the trough concentration was 35 ng/mL. However, this regimen was still inadequate because he had breakthrough symptoms prior to the next injection.

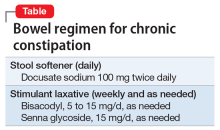

By decreasing the injection interval from 28 days to 21 days, the concentrations will increase to a new steady state. This will take the same 132 days. With the reduced injection frequency of 21 days, 7 injections will have been given prior to reaching the new steady state. Steady state is not dependent on the number of injections, but only on the absorption half-life. This new steady state trough is substantially higher at 52 ng/mL, but still in the expected range for commonly used doses. Because Mr. B’s hallucinations only appeared at the end of the dosing interval, it is reasonable to expect that his new regimen would be successful in suppressing his hallucinations. However, monitoring for peak-related adverse effects is essential. Based upon controlled clinical trials, the potential dose-related adverse effects of paliperidone include akathisia, other extrapyramidal symptoms, weight gain, and QTc prolongation.

Continue to: Would monitoring a patient's paliperidone serum concentrations be useful?

Would monitoring a patient’s paliperidone serum concentrations be useful? Currently, measuring an individual’s paliperidone serum concentration is generally considered unwarranted.3,4 One of the major reasons is a lack of appropriately designed studies to determine a therapeutic range.5 Flexible dose designs, commonly used in registration studies, cloud the relationships between concentration, time, response, and adverse effects. There are additional problems that are the result of diagnostic heterogeneity and placebo responders. A well-designed study to determine the therapeutic range would have ≥1 fixed dose groups and be diagnostically homogeneous. There are currently only a limited number of clinical laboratories that have implemented suitable assays.

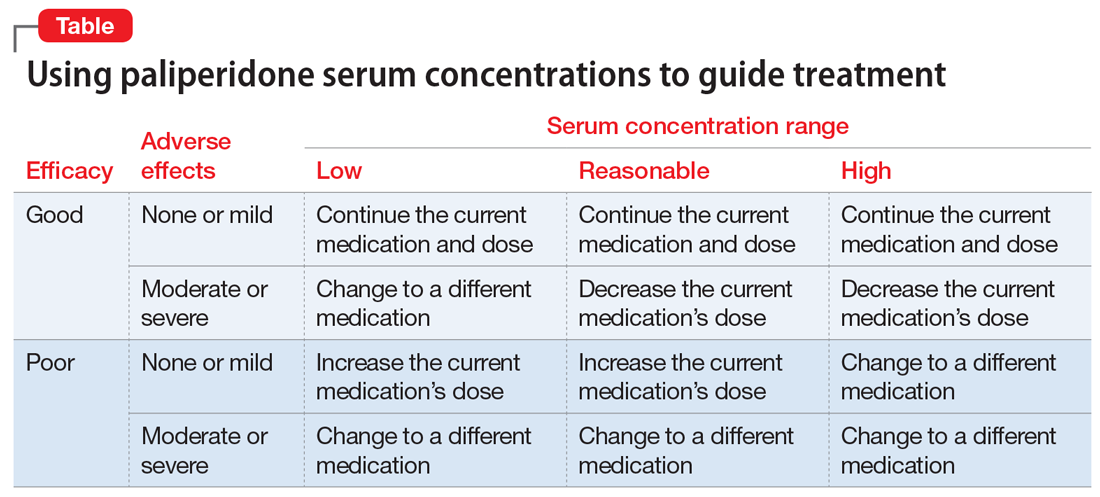

Given the lack of knowledge of a therapeutic range, assured knowledge of nonadherence to LAIs, and the absence of significant drug interactions for paliperidone, there remain a few reasonable justifications for obtaining a patient’s paliperidone serum concentration (Table). If the patient had a good response with mild adverse effects, there is no reason to obtain a paliperidone serum concentration or make any change in the medication or dose. However, if the patient had a good response accompanied by moderate or severe adverse effects, or the patient has a poor response, then obtaining the paliperidone serum concentration could help determine an appropriate course of action.

CASE CONTINUED

After the second dose at the increased frequency on Day 252, the paliperidone serum concentration was maintained above 40 ng/mL. Mr. B continued to tolerate the LAI well and no longer reported any breakthrough hallucinations.

Related Resources

- ARUP Laboratories. Paliperidone, serum or plasma. http://ltd.aruplab.com/tests/pub/2007949.

- LabCorp. Paliperidone Paliperidone (as 9-hydroxyrisperidone), serum or plasma. https://www.labcorp.com/test-menu/38351/paliperidone-as-9-hydroxyrisperidone-serum-or-plasma.

- Janssen Scientific Affairs. Educational dose illustrator. http://www.educationaldoseillustrator.com.

Drug Brand Names

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Jann MW, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the depot antipsychotics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1985;10(4):315-333.

2. Cleton A, Rossenu S, Crauwels H, et al. A single-dose, open-label, parallel, randomized, dose-proportionality study of paliperidone after intramuscular injections of paliperidone palmitate in the deltoid or gluteal muscle in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54(9):1048-1057.

3. Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. 12th ed. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2015:1-10.

4. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

5. Lopez LV, Kane JM. Plasma levels of second-generation antipsychotics and clinical response in acute psychosis: a review of the literature. Schizophr Res. 2013;147(2-3):368-374.

Mr. B, age 27, has a 10-year history of schizophrenia. Last year, he was doing well and working 4 hours/day 3 days/week while taking oral risperidone, 6 mg, at bedtime. However, during the past 2 weeks Mr. B began to have a return of auditory hallucinations and reports that he stopped taking his medication again 6 weeks ago.

As a result, he is started on paliperidone palmitate following the product label’s initiation dosing recommendation. On the first day he is given the first dose of the initiation regimen, 234 mg IM. One week later, the second dose of the initiation regimen, 156 mg IM, is given. One month later, the first maintenance dose of 117 mg IM every 28 days is given. All injections are in his deltoid muscle at his request.

After 3 weeks on the first maintenance dose of 117 mg, the voices begin to bother him again. Subsequently, Mr. B’s maintenance dose is increased first to 156 mg, and for the same problem with breakthrough hallucinations the following month to 234 mg, the maximum dose in the product label. After 6 months of receiving 234 mg IM every 28 days, the auditory hallucinations continue to bother him, but only for a few days prior to his next injection. He misses work 1 or 2 times before each injection.

Can the injection frequency for Mr. B’s paliperidone palmitate, 234 mg IM, in the deltoid muscle be increased to every 21 days to prevent the monthly exacerbations? Yes, the injection frequency can be increased, and doing so will increase the concentrations of paliperidone. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) is complicated by the lengthy time needed to reach steady state. In the case of paliperidone palmitate, an initiation regimen was developed that achieves therapeutic concentrations that are close to steady state before the oral antipsychotic’s effects are lost. This initiation strategy avoids the need for oral supplementation to maintain clinical efficacy. However, even using an initiation regimen or a loading dose does not decrease the time to final steady state after a dose adjustment due to the slow absorption of the medication from the injection site. The time to steady state is controlled by “flip-flop” pharmacokinetics. In this kind of pharmacokinetics, which is observed with all LAIs, the absorption rate from the injection site is lower than the elimination rate.1

Cleton et al2 reported the pharmacokinetics of paliperidone palmitate for deltoid and gluteal injection sites. By combining the median data for the deltoid injection route from the article by Cleton et al2 and the dosing from Mr. B’s case, I created a model using superposition of a sixth-degree polynomial fitted to the single dose data. Gluteal injections were not included because their increased complexity is beyond the scope of this article, but the time to maximum concentration (gluteal > deltoid) and peak concentration (deltoid > gluteal) are different for each route. The polynomial was a good fit with the adjusted r2 = 0.976, P < .0001. This model illustrates the paliperidone serum concentrations for Mr. B and is shown in the Figure. As you can see, by Day 9, the serum concentrations had reached the lower limit of the expected range of 20 to 60 ng/mL, shown in the shaded region of the Figure.3

Steady state at the routine maintenance dose of 117 mg every 28 days was never reached as the medication was not sufficient to suppress Mr. B’s hallucinations, and his doses needed to be increased each month. First, Mr. B’s dose was increased to 156 mg and then to the maximum recommended dose of 234 mg every 28 days. Steady state can be considered to have been achieved when 90% of the final steady state is reached after 3.3 half-lives. Because of the flip-flop pharmacokinetics, the important half-life is the absorption half-life of approximately 40 days or 132 days at the same dose. In Mr. B’s case, this was Day 221, where the trough concentration was 35 ng/mL. However, this regimen was still inadequate because he had breakthrough symptoms prior to the next injection.

By decreasing the injection interval from 28 days to 21 days, the concentrations will increase to a new steady state. This will take the same 132 days. With the reduced injection frequency of 21 days, 7 injections will have been given prior to reaching the new steady state. Steady state is not dependent on the number of injections, but only on the absorption half-life. This new steady state trough is substantially higher at 52 ng/mL, but still in the expected range for commonly used doses. Because Mr. B’s hallucinations only appeared at the end of the dosing interval, it is reasonable to expect that his new regimen would be successful in suppressing his hallucinations. However, monitoring for peak-related adverse effects is essential. Based upon controlled clinical trials, the potential dose-related adverse effects of paliperidone include akathisia, other extrapyramidal symptoms, weight gain, and QTc prolongation.

Continue to: Would monitoring a patient's paliperidone serum concentrations be useful?

Would monitoring a patient’s paliperidone serum concentrations be useful? Currently, measuring an individual’s paliperidone serum concentration is generally considered unwarranted.3,4 One of the major reasons is a lack of appropriately designed studies to determine a therapeutic range.5 Flexible dose designs, commonly used in registration studies, cloud the relationships between concentration, time, response, and adverse effects. There are additional problems that are the result of diagnostic heterogeneity and placebo responders. A well-designed study to determine the therapeutic range would have ≥1 fixed dose groups and be diagnostically homogeneous. There are currently only a limited number of clinical laboratories that have implemented suitable assays.

Given the lack of knowledge of a therapeutic range, assured knowledge of nonadherence to LAIs, and the absence of significant drug interactions for paliperidone, there remain a few reasonable justifications for obtaining a patient’s paliperidone serum concentration (Table). If the patient had a good response with mild adverse effects, there is no reason to obtain a paliperidone serum concentration or make any change in the medication or dose. However, if the patient had a good response accompanied by moderate or severe adverse effects, or the patient has a poor response, then obtaining the paliperidone serum concentration could help determine an appropriate course of action.

CASE CONTINUED

After the second dose at the increased frequency on Day 252, the paliperidone serum concentration was maintained above 40 ng/mL. Mr. B continued to tolerate the LAI well and no longer reported any breakthrough hallucinations.

Related Resources

- ARUP Laboratories. Paliperidone, serum or plasma. http://ltd.aruplab.com/tests/pub/2007949.

- LabCorp. Paliperidone Paliperidone (as 9-hydroxyrisperidone), serum or plasma. https://www.labcorp.com/test-menu/38351/paliperidone-as-9-hydroxyrisperidone-serum-or-plasma.

- Janssen Scientific Affairs. Educational dose illustrator. http://www.educationaldoseillustrator.com.

Drug Brand Names

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Risperidone • Risperdal

Mr. B, age 27, has a 10-year history of schizophrenia. Last year, he was doing well and working 4 hours/day 3 days/week while taking oral risperidone, 6 mg, at bedtime. However, during the past 2 weeks Mr. B began to have a return of auditory hallucinations and reports that he stopped taking his medication again 6 weeks ago.

As a result, he is started on paliperidone palmitate following the product label’s initiation dosing recommendation. On the first day he is given the first dose of the initiation regimen, 234 mg IM. One week later, the second dose of the initiation regimen, 156 mg IM, is given. One month later, the first maintenance dose of 117 mg IM every 28 days is given. All injections are in his deltoid muscle at his request.

After 3 weeks on the first maintenance dose of 117 mg, the voices begin to bother him again. Subsequently, Mr. B’s maintenance dose is increased first to 156 mg, and for the same problem with breakthrough hallucinations the following month to 234 mg, the maximum dose in the product label. After 6 months of receiving 234 mg IM every 28 days, the auditory hallucinations continue to bother him, but only for a few days prior to his next injection. He misses work 1 or 2 times before each injection.

Can the injection frequency for Mr. B’s paliperidone palmitate, 234 mg IM, in the deltoid muscle be increased to every 21 days to prevent the monthly exacerbations? Yes, the injection frequency can be increased, and doing so will increase the concentrations of paliperidone. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) is complicated by the lengthy time needed to reach steady state. In the case of paliperidone palmitate, an initiation regimen was developed that achieves therapeutic concentrations that are close to steady state before the oral antipsychotic’s effects are lost. This initiation strategy avoids the need for oral supplementation to maintain clinical efficacy. However, even using an initiation regimen or a loading dose does not decrease the time to final steady state after a dose adjustment due to the slow absorption of the medication from the injection site. The time to steady state is controlled by “flip-flop” pharmacokinetics. In this kind of pharmacokinetics, which is observed with all LAIs, the absorption rate from the injection site is lower than the elimination rate.1

Cleton et al2 reported the pharmacokinetics of paliperidone palmitate for deltoid and gluteal injection sites. By combining the median data for the deltoid injection route from the article by Cleton et al2 and the dosing from Mr. B’s case, I created a model using superposition of a sixth-degree polynomial fitted to the single dose data. Gluteal injections were not included because their increased complexity is beyond the scope of this article, but the time to maximum concentration (gluteal > deltoid) and peak concentration (deltoid > gluteal) are different for each route. The polynomial was a good fit with the adjusted r2 = 0.976, P < .0001. This model illustrates the paliperidone serum concentrations for Mr. B and is shown in the Figure. As you can see, by Day 9, the serum concentrations had reached the lower limit of the expected range of 20 to 60 ng/mL, shown in the shaded region of the Figure.3

Steady state at the routine maintenance dose of 117 mg every 28 days was never reached as the medication was not sufficient to suppress Mr. B’s hallucinations, and his doses needed to be increased each month. First, Mr. B’s dose was increased to 156 mg and then to the maximum recommended dose of 234 mg every 28 days. Steady state can be considered to have been achieved when 90% of the final steady state is reached after 3.3 half-lives. Because of the flip-flop pharmacokinetics, the important half-life is the absorption half-life of approximately 40 days or 132 days at the same dose. In Mr. B’s case, this was Day 221, where the trough concentration was 35 ng/mL. However, this regimen was still inadequate because he had breakthrough symptoms prior to the next injection.

By decreasing the injection interval from 28 days to 21 days, the concentrations will increase to a new steady state. This will take the same 132 days. With the reduced injection frequency of 21 days, 7 injections will have been given prior to reaching the new steady state. Steady state is not dependent on the number of injections, but only on the absorption half-life. This new steady state trough is substantially higher at 52 ng/mL, but still in the expected range for commonly used doses. Because Mr. B’s hallucinations only appeared at the end of the dosing interval, it is reasonable to expect that his new regimen would be successful in suppressing his hallucinations. However, monitoring for peak-related adverse effects is essential. Based upon controlled clinical trials, the potential dose-related adverse effects of paliperidone include akathisia, other extrapyramidal symptoms, weight gain, and QTc prolongation.

Continue to: Would monitoring a patient's paliperidone serum concentrations be useful?

Would monitoring a patient’s paliperidone serum concentrations be useful? Currently, measuring an individual’s paliperidone serum concentration is generally considered unwarranted.3,4 One of the major reasons is a lack of appropriately designed studies to determine a therapeutic range.5 Flexible dose designs, commonly used in registration studies, cloud the relationships between concentration, time, response, and adverse effects. There are additional problems that are the result of diagnostic heterogeneity and placebo responders. A well-designed study to determine the therapeutic range would have ≥1 fixed dose groups and be diagnostically homogeneous. There are currently only a limited number of clinical laboratories that have implemented suitable assays.

Given the lack of knowledge of a therapeutic range, assured knowledge of nonadherence to LAIs, and the absence of significant drug interactions for paliperidone, there remain a few reasonable justifications for obtaining a patient’s paliperidone serum concentration (Table). If the patient had a good response with mild adverse effects, there is no reason to obtain a paliperidone serum concentration or make any change in the medication or dose. However, if the patient had a good response accompanied by moderate or severe adverse effects, or the patient has a poor response, then obtaining the paliperidone serum concentration could help determine an appropriate course of action.

CASE CONTINUED

After the second dose at the increased frequency on Day 252, the paliperidone serum concentration was maintained above 40 ng/mL. Mr. B continued to tolerate the LAI well and no longer reported any breakthrough hallucinations.

Related Resources

- ARUP Laboratories. Paliperidone, serum or plasma. http://ltd.aruplab.com/tests/pub/2007949.

- LabCorp. Paliperidone Paliperidone (as 9-hydroxyrisperidone), serum or plasma. https://www.labcorp.com/test-menu/38351/paliperidone-as-9-hydroxyrisperidone-serum-or-plasma.

- Janssen Scientific Affairs. Educational dose illustrator. http://www.educationaldoseillustrator.com.

Drug Brand Names

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Jann MW, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the depot antipsychotics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1985;10(4):315-333.

2. Cleton A, Rossenu S, Crauwels H, et al. A single-dose, open-label, parallel, randomized, dose-proportionality study of paliperidone after intramuscular injections of paliperidone palmitate in the deltoid or gluteal muscle in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54(9):1048-1057.

3. Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. 12th ed. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2015:1-10.

4. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

5. Lopez LV, Kane JM. Plasma levels of second-generation antipsychotics and clinical response in acute psychosis: a review of the literature. Schizophr Res. 2013;147(2-3):368-374.

1. Jann MW, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the depot antipsychotics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1985;10(4):315-333.

2. Cleton A, Rossenu S, Crauwels H, et al. A single-dose, open-label, parallel, randomized, dose-proportionality study of paliperidone after intramuscular injections of paliperidone palmitate in the deltoid or gluteal muscle in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54(9):1048-1057.

3. Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. 12th ed. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2015:1-10.

4. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

5. Lopez LV, Kane JM. Plasma levels of second-generation antipsychotics and clinical response in acute psychosis: a review of the literature. Schizophr Res. 2013;147(2-3):368-374.

Helping survivors in the aftermath of suicide loss

The loss of a loved one to suicide is often experienced as “devastating.”1 While survivors of suicide loss may be able to move through the grief process without clinical support,2 the traumatic and stigmatizing nature of suicide is likely to make its aftermath more challenging to navigate than other types of loss. Sanford et al3 found that more than two-thirds of suicide loss survivors sought therapy after their loss. Further, when individuals facing these challenges present for treatment, clinicians often face challenges of their own.

Very few clinicians are trained in general grief processes,4 and even those specifically trained in grief and loss have been shown to “miss” several of the common clinical features that are unique to suicide loss.3 In my professional experience, the intensity and duration of suicide grief are often greater than they are for other losses, and many survivors of suicide loss have reported that others, including clinicians, have “pathologized” this, rather than having understood it as normative under the circumstances.

Although there is extensive literature on the aftermath of suicide for surviving loved ones, very few controlled studies have assessed interventions specifically for this population. Yet the U.S. Guidelines for Suicide Postvention5 explicitly call for improved training for those who work with suicide loss survivors, as well as research on these interventions. Jordan and McGann6 noted, “Without a full knowledge of suicide and its aftermath, it is very possible to make clinical errors which can hamper treatment.” This article summarizes what is currently known about the general experience of suicide bereavement and optimal interventions in treatment.

What makes suicide loss unique?

Suicide bereavement is distinct from other types of loss in 3 significant ways7:

- the thematic content of the grief

- the social processes surrounding the survivor

- the impact that suicide has on family systems.

Additionally, the perceived intentionality and preventability of a suicide death, as well as its stigmatized and traumatic nature, differentiate it from other types of traumatic loss.7 These elements are all likely to affect the nature, intensity, and duration of the grief.

Stigma and suicide. Stigma associated with suicide is well documented.8 Former U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher9 specifically described stigma toward suicide as one of the biggest barriers to prevention. In addition, researchers have found that the stigma associated with suicide “spills over” to the bereaved family members. Doka10,11 refers to “disenfranchised grief,” in which bereaved individuals receive the message that their grief is not legitimate, and as a result, they are likely to internalize this view. Studies have shown that individuals bereaved by suicide are also stigmatized, and are believed to be more psychologically disturbed, less likable, more blameworthy, more ashamed, and more in need of professional help than other bereaved individuals.8,12-20

These judgments often mirror suicide loss survivors’ self-punitive assessments, which then become exacerbated by and intertwined with both externally imposed and internalized stigma. Thus, it is not uncommon for survivors of suicide loss to question their own right to grieve, to report low expectations of social support, and to feel compelled to deny or hide the mode of death. To the extent that they are actively grieving, survivors of suicide loss often feel that they must do so in isolation. Thus, the perception of stigma, whether external or internalized, can have a profound effect on decisions about disclosure, requesting support, and ultimately on one’s ability to integrate the loss. Indeed, Feigelman et al21 found that stigmatization after suicide was specifically associated with ongoing grief difficulties, depression, and suicidal ideation.

Continue to: Traumatic nature of suicide

Traumatic nature of suicide. Suicide loss is also quite traumatic, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms such as shock, horror, disbelief, and intrusive/perseverative thoughts and questions, particularly in the earlier stages of grief, are common. Sanford et al3 found that the higher the level of “perceived closeness” to the deceased, the more likely that survivors of suicide loss would experience PTSD symptoms. In addition, the dramatic loss of social support following a suicide loss may itself be traumatic, which can serve to compound these difficulties. Notably, Sanford et al3 found that even for those survivors of suicide loss in treatment who endorsed PTSD symptoms, many of their treating clinicians did not assess or diagnose this disorder, thus missing an important component for treatment.

Increased risk for suicidality. Studies have shown that individuals who have lost a loved one to suicide are themselves at heightened risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors.22-27 Therefore, an assessment for suicide risk is always advisable. However, it is important to note that suicidal ideation is not uncommon and can serve different functions for survivors of suicide loss without necessarily progressing to a plan for acting on such ideations. Survivors of suicide loss may wish to “join” their loved one; to understand or identify with the mental state of the deceased; to punish themselves for failing to prevent the suicide; or to end their own pain through death. Therefore, it is crucial to assess the nature and function of expressed ideation (in addition to the presence or absence of plans) before assigning the level of risk.

Elements of suicide grief

After the loss of a loved one to suicide, the path to healing is often complex, with survivors of suicide loss enduring the following challenges:

Existential assumptions are shattered. Several authors28-30 have found that suicide loss is also likely to shatter survivors’ existential assumptions regarding their worldviews, roles, and identities, as well as religious and spiritual beliefs. As one survivor of suicide loss in my practice noted, “The world is gone, nothing is predictable anymore, and it’s no longer safe to assume anything.” Others have described feeling “fragmented” in ways they had never before experienced, and many have reported difficulties in “trusting” their own judgment, the stability of the world, and relationships. “Why?” becomes an emergent and insistent question in the survivor’s efforts to understand the suicide and (ideally) reassemble a coherent narrative around the loss.

Increased duration and intensity of grief. The duration of the grief process is likely to be affected by the traumatic nature of suicide loss, the differential social support accorded to its survivors, and the difficulty in finding systems that can validate and normalize the unique elements in suicide bereavement. The stigmatized reactions of others, particularly when internalized, can present barriers to the processing of grief. In addition, the intensity of the trauma and existential impact, as well as the perseverative nature of several of the unique themes (Box 1), can also prolong the processing and increase the intensity of suicide grief. Clinicians would do well to recognize the relatively “normative” nature of the increased duration and intensity, rather than seeing it as immediately indicative of a DSM diagnosis of complicated/prolonged grief disorder.

Box 1

Common themes in the suicide grief process

Several common themes are likely to emerge during the suicide grief process. Guilt and a sense of failure—around what one did and did not do—can be pervasive and persistent, and are often present even when not objectively warranted.

Anger and blame directed towards the deceased, other family members, and clinicians who had been treating the deceased may also be present, and may be used in efforts to deflect guilt. Any of these themes may be enlisted to create a deceptively simple narrative for understanding the reasons for the suicide.

Shame is often present, and certainly exacerbated by both external and internalized stigma. Feelings of rejection, betrayal, and abandonment by the deceased are also common, as well as fear/hypervigilance regarding the possibility of losing others to suicide. Given the intensity of suicide grief, it has been my observation that there may also be fear in relation to one's own mental status, as many otherwise healthy survivors of suicide loss have described feeling like they're "going crazy." Finally, there may also be relief, particularly if the deceased had been suffering from chronic psychiatric distress or had been cruel or abusive.

Continue to: Family disruption

Family disruption. It is not uncommon for a suicide loss to result in family disruption.6,31-32 This may manifest in the blaming of family members for “sins of omission or commission,”6 conflicts around the disclosure of the suicide both within and outside of the family, discordant grieving styles, and difficulties in understanding and attending to the needs of one’s children while grieving oneself.

Despite the common elements often seen in suicide grief, it is crucial to recognize that this process is not “one size fits all.” Not only are there individual variants, but Grad et al33 found gender-based differences in grieving styles, and cultural issues such as the “meanings” assigned to suicide, and culturally sanctioned grief rituals and behaviors that are also likely to affect how grief is experienced and expressed. In addition, personal variants such as closeness/conflicts with the deceased, histories of previous trauma or loss, pre-existing psychiatric disorders, and attachment orientation34 are likely to impact the grief process.

Losing close friends and colleagues may be similarly traumatic, but these survivors of suicide loss often receive even less social support than those who have kinship losses. Finally, when a suicide loss occurs in a professional capacity (such as the loss of a patient), this is likely to have many additional implications for one’s professional functions and identity.35

Interventions to help survivors

Several goals and “tasks” are involved in the suicide bereavement process (Box 21,6,30,36-40). These can be achieved through the following interventions: Support groups. Many survivors find that support groups that focus on suicide loss are extremely helpful, and research has supported this.1,4,41-44 Interactions with other suicide loss survivors provide hope, connection, and an “antidote” to stigma and shame. Optimally, group facilitators provide education, validation and normalization of the grief trajectory, and facilitate the sharing of both loss experiences and current functioning between group members. As a result, group participants often report renewed connections, increased efficacy in giving and accepting support, and decreased distress (including reductions in PTSD and depressive symptoms). The American Association of Suicidology (www.suicidology.org) and American Foundation of Suicide Prevention (www.afsp.org) provide contact information for suicide loss survivor groups (by geographical area) as well as information about online support groups.

Box 2

Goals and 'tasks' in suicide bereavement

The following goals and "tasks" should be part of the process of suicide bereavement:

- Reduce symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychiatric disorders. Given the traumatic nature of the loss, an important goal is to understand and reduce posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychiatric symptoms, and incrementally improving functionality in relation to these.

- Integrate the loss. Recent authors36-38 have highlighted the need for survivors of suicide loss to "bear" and integrate the loss, as opposed to the concept of "getting over it." In these paradigms, the loss becomes an important part of one's identity, and eventually ceases to define it. Optimally, the "whole person" is remembered, not just the suicide. Part of this involves a reinvestment in life, with the acceptance of a "new normal" that takes the loss into account. It is not unusual for survivors of suicide loss to report some guilt in "moving on" and/or experiencing pleasure; often this is felt as a "betrayal" of the deceased.

- Create meaning from the loss. A major goal for those who have lost a loved one to suicide is the ability to find and/or create meaning from the loss. This would include the creation of a loss narrative39 that incorporates both ambiguity and complexity, as well as a regained/renewed sense of purpose in ongoing life.

- Develop ambiguity tolerance. A related "task" in suicide grief is the development of ambiguity tolerance, which generally includes an understanding of the complexity underlying suicide, the ability to offer oneself a "fair trial"30 in relation to one's realistic degree of responsibility, and the acceptance that many questions may remain unanswerable. In addition, in concert with the current understanding of "continuing bonds,"40 survivors should attempt to attend to the ongoing relationship with the deceased, including any "unfinished business."6

- Develop skills to manage stigmatized social responses and/or changes in family and social relationships.

- Memorialize and honor the deceased. Healing for survivors is facilitated by memorializations, which both validate the mourning process itself while also paying tribute to the richness of the deceased person's life.

- Post-traumatic growth. The relatively new understanding of "post-traumatic" growth is certainly applicable to the "unexpected gifts" many survivors of suicide loss report after they have moved through suicide grief. This includes greater understanding toward oneself, other survivors of suicide loss, and suicidal individuals; gratitude toward those who have provided support; and a desire to "use" their newfound understanding of suicide and suicide grief in ways to honor the deceased and benefit others. Feigelman et al1 found that many longer-term survivors of suicide loss engaged in both direct service and social activism around suicide pre- and postvention.

Individual treatment. The limited research on individual treatment for suicide loss survivors suggests that while most participants find it generally helpful, a significant number of others report that their therapists lack knowledge of suicide grief and endorse stigmatizing attitudes toward suicide and suicide loss survivors.45-46 In addition, Sanford et al3 found that survivors of suicide loss who endorsed PTSD symptoms were not assessed, diagnosed, or treated for these symptoms.

Continue to: This speaks to the importance of understanding what is...

This speaks to the importance of understanding what is “normative” for survivors of suicide loss. In general, “normalization” and psychoeducation about the suicide grief trajectory can play an important role in work with survivors of suicide loss, even in the presence of diagnosable disorders. While PTSD, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation are not uncommon in suicide loss survivors, and certainly may warrant clinical assessment and treatment, it can be helpful (and less stigmatizing) for your patients to know that these diagnoses are relatively common and understandable in the context of this devastating experience. For instance, survivors of suicide loss often report feeling relieved when clinicians explain the connections between traumatic loss and PTSD and/or depressive symptoms, and this can also help to relieve secondary anxiety about “going crazy.” Many survivors of suicide loss also describe feeling as though they are functioning on “autopilot” in the earlier stages of grief; it can help them understand the “function” of compartmentalization as potentially adaptive in the short run.

Suicide loss survivors may also find it helpful to learn about suicidal states of mind and their relationships to any types of mental illness their loved ones had struggled with.47

Your role: Help survivors integrate the loss

Before beginning treatment with an individual who has lost a loved one to suicide, clinicians should thoroughly explore their own understanding of and experience with suicide, including assumptions around causation, internalized stigma about suicidal individuals and survivors of suicide loss, their own history of suicide loss or suicidality, cultural/religious attitudes, and anxiety/defenses associated with the topic of suicide. These factors, particularly when unexamined, are likely to impact the treatment relationship and one’s clinical efficacy.

In concert with the existing literature, consider the potential goals and tasks involved in the integration of the individual’s suicide loss, along with any individual factors/variants that may impact the grief trajectory. Kosminsky and Jordon34 described the role of the clinician in this situation as a “transitional attachment figure” who facilitates the management and integration of the loss into the creation of what survivors of suicide loss have termed a “new normal.”

Because suicide loss is often associated with PTSD and other psychiatric illnesses (eg, depression, suicidality, substance abuse), it is essential to balance the assessment and treatment of these issues with attention to grief issues as needed. Again, to the extent that such issues have arisen primarily in the wake of the suicide loss, it can be helpful for patients to understand their connection to the context of the loss.

Continue to: Ideally, the clinician should...

Ideally, the clinician should be “present” with the patient’s pain, normative guilt, and rumination, without attempting to quickly eliminate or “fix” it or provide premature reassurance that the survivor of suicide loss “did nothing wrong.” Rather, as Jordan6 suggests, the clinician should act to promote a “fair trial” with respect to the patient’s guilt and blame, with an understanding of the “tyranny of hindsight.” The promotion of ambiguity tolerance should also play a role in coming to terms with many questions that may remain unanswered.

Optimally, clinicians should encourage patients to attend to their ongoing relationship with the deceased, particularly in the service of resolving “unfinished business,” ultimately integrating the loss into memories of the whole person. In line with this, survivors of suicide loss may be encouraged to create a narrative of the loss that incorporates both complexity and ambiguity. In the service of supporting the suicide loss survivor’s reinvestment in life, it is often helpful to facilitate their ability to anticipate and cope with triggers, such as anniversaries, birthdays, or holidays, as well as to develop and use skills for managing difficult or stigmatizing social or cultural reactions.

Any disruptions in family functioning should also be addressed. Psychoeducation about discordant grieving styles (particularly around gender) and the support of children’s grief may be helpful, and referrals to family or couples therapists should be considered as needed. Finally, the facilitation of suicide loss survivors’ creation of memorializations or rituals can help promote healing and make their loss meaningful.

Bottom Line

Losing a loved one to suicide is often a devastating and traumatic experience, but with optimal support, most survivors are ultimately able to integrate the loss and grow as a result. Understanding the suicide grief trajectory, as well as general guidelines for treatment, will facilitate healing and growth in the aftermath of suicide loss.

Related Resources

- Jordan JR, McIntosh JL. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011.

- American Association of Suicidology. http://www.suicidology.org/.

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. https://afsp.org/.

1. Feigelman W, Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, et al. Devastating losses: how parents cope with the death of a child to suicide or drugs. New York, NY: Springer; 2012.

2. McIntosh JL. Research on survivors of suicide. In: Stimming MT, Stimming M, eds. Before their time: adult children’s experiences of parental suicide. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1999:157-180.

3. Sanford RL, Cerel J, McGann VL, et al. Suicide loss survivors’ experiences with therapy: Implications for clinical practice. Community Ment Health J. 2016;5(2):551-558.

4. Jordan JR, McMenamy J. Interventions for suicide survivors: a review of the literature. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2004;34(4):337-349.

5. Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force. Responding to grief, trauma, & distress after a suicide: U.S. national guidelines. Washington, DC: National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention; 2015.

6. Jordan JR, McGann V. Clinical work with suicide loss survivors: implications of the U.S. postvention guidelines. Death Stud. 2017;41(10):659-672.

7. Jordan JR. Is suicide bereavement different? A reassessment of the literature. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31(1):91-102.

8. Cvinar JG. Do suicide survivors suffer social stigma: a review of the literature. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2005;41(1):14-21.

9. U.S. Public Health Service. The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent suicide. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 1999.

10. Doka KJ. Disenfranchised grief: recognizing hidden sorrow. Lexington, MA: Lexington; 1989.

11. Doka KJ. Disenfranchised grief: new directions, challenges, and strategies for practice. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 2002.

12. McIntosh JL. Suicide survivors: the aftermath of suicide and suicidal behavior. In: Bryant CD, ed. Handbook of death & dying. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2003:339-350.

13. Jordan, JR, McIntosh, JL. Is suicide bereavement different? A framework for rethinking the question. In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011:19-42.

14. Dunne EJ, McIntosh JL, Dunne-Maxim K, eds. Suicide and its aftermath: understanding and counseling the survivors. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.; 1987.

15. Harwood D, Hawton K, Hope T, et al. The grief experiences and needs of bereaved relatives and friends of older people dying through suicide: a descriptive and case-control study. J Affect Disord. 2002;72(2):185-194.

16. Armour, M. Violent death: understanding the context of traumatic and stigmatized grief. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2006;14(4):53-90.

17. Van Dongen CJ. Social context of postsuicide bereavement. Death Stud. 1993;17(2):125-141.

18. Calhoun LG, Allen BG. Social reactions to the survivor of a suicide in the family: A review of the literature. Omega – Journal of Death and Dying. 1991;23(2):95-107.

19. Range LM. When a loss is due to suicide: unique aspects of bereavement. In: Harvey JH, ed. Perspectives on loss: a sourcebook. Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel; 1998:213-220.

20. Sveen CA, Walby FA. Suicide survivors’ mental health and grief reactions: a systematic review of controlled studies. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38(1):13-29.

21. Feigelman W, Gorman BS, Jordan JR. Stigmatization and suicide bereavement. Death Stud. 2009;33(7):591-608.

22. Shneidman ES. Foreword. In: Cain AC, ed. Survivors of suicide. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1972:ix-xi.

23. Jordan JR, McIntosh, JL. Suicide bereavement: Why study survivors of suicide loss? In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011:3-18.

24. Agerbo E. Midlife suicide risk, partner’s psychiatric illness, spouse and child bereavement by suicide or other modes of death: a gender specific study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(5):407-412.

25. Hedström P, Liu KY, Nordvik MK. Interaction domains and suicide: a population-based panel study of suicides in Stockholm, 1991-1999. Soc Forces. 2008;87(2):713-740.

26. Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB. Suicide risk in relation to family history of completed suicide and psychiatric disorders: a nested case-control study based on longitudinal registers. Lancet. 2002;360(9340):1126-1130.

27. Qin P, Mortensen PB. The impact of parental status on the risk of completed suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(8):797-802.

28. Neimeyer RA, Sands D. Suicide loss and the quest for meaning. In: Andriessen K, Krysinska K, Grad OT, eds. Postvention in action: the international handbook of suicide bereavement support. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe; 2017:71-84.

29. Sands DC, Jordan JR, Neimeyer RA. The meanings of suicide: A narrative approach to healing. In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011:249-282.

30. Jordan JR. Principles of grief counseling with adult survivors. In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011:179-224.

31. Cerel J, Jordan JR, Duberstein PR. The impact of suicide on the family. Crisis. 2008;29:38-44.

32. Kaslow NJ, Samples TC, Rhodes M, et al. A family-oriented and culturally sensitive postvention approach with suicide survivors. In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011:301-323.

33. Grad OT, Treven M, Krysinska K. Suicide bereavement and gender. In: Andriessen K, Krysinska K, Grad OT, eds. Postvention in action: the international handbook of suicide bereavement support. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe; 2017:39-49.

34. Kosminsky PS, Jordan JR. Attachment-informed grief therapy: the clinician’s guide to foundations and applications. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016.

35. Gutin N, McGann VL, Jordan JR. The impact of suicide on professional caregivers. In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011:93-111.

36. Jordan JR. Bereavement after suicide. Psychiatr Ann. 2008;38(10):679-685.

37. Jordan JR. After suicide: clinical work with survivors. Grief Matters. 2009;12(1):4-9.

38. Neimeyer, RA. Traumatic loss and the reconstruction of meaning. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(6):935-942; discussion 942-943.

39. Neimeyer R, ed. Meaning reconstruction & the experience of loss. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001.

40. Klass, D. Sorrow and solace: Neglected areas in bereavement research. Death Stud. 2013;37(7):597-616.

41. Farberow NL. The Los Angeles Survivors-After-Suicide program: an evaluation. Crisis. 1992;13(1):23-34.

42. McDaid C, Trowman R, Golder S, et al. Interventions for people bereaved through suicide: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(6):438-443.

43. Groos AD, Shakespeare-Finch J. Positive experiences for participants in suicide bereavement groups: a grounded theory model. Death Stud. 2013;37(1):1-24.

44. Jordan JR. Group work with suicide survivors. In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011:283-300.

45. Wilson A, Marshall A. The support needs and experiences of suicidally bereaved family and friends. Death Stud. 2010;34(7):625-640.

46. McKinnon JM, Chonody J. Exploring the formal supports used by people bereaved through suicide: a qualitative study. Soc Work Ment Health. 2014;12(3):231-248.

47. Myers MF, Fine C. Touched by suicide: hope and healing after loss. New York, NY: Gotham Books; 2006.

The loss of a loved one to suicide is often experienced as “devastating.”1 While survivors of suicide loss may be able to move through the grief process without clinical support,2 the traumatic and stigmatizing nature of suicide is likely to make its aftermath more challenging to navigate than other types of loss. Sanford et al3 found that more than two-thirds of suicide loss survivors sought therapy after their loss. Further, when individuals facing these challenges present for treatment, clinicians often face challenges of their own.

Very few clinicians are trained in general grief processes,4 and even those specifically trained in grief and loss have been shown to “miss” several of the common clinical features that are unique to suicide loss.3 In my professional experience, the intensity and duration of suicide grief are often greater than they are for other losses, and many survivors of suicide loss have reported that others, including clinicians, have “pathologized” this, rather than having understood it as normative under the circumstances.

Although there is extensive literature on the aftermath of suicide for surviving loved ones, very few controlled studies have assessed interventions specifically for this population. Yet the U.S. Guidelines for Suicide Postvention5 explicitly call for improved training for those who work with suicide loss survivors, as well as research on these interventions. Jordan and McGann6 noted, “Without a full knowledge of suicide and its aftermath, it is very possible to make clinical errors which can hamper treatment.” This article summarizes what is currently known about the general experience of suicide bereavement and optimal interventions in treatment.

What makes suicide loss unique?

Suicide bereavement is distinct from other types of loss in 3 significant ways7:

- the thematic content of the grief

- the social processes surrounding the survivor

- the impact that suicide has on family systems.

Additionally, the perceived intentionality and preventability of a suicide death, as well as its stigmatized and traumatic nature, differentiate it from other types of traumatic loss.7 These elements are all likely to affect the nature, intensity, and duration of the grief.

Stigma and suicide. Stigma associated with suicide is well documented.8 Former U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher9 specifically described stigma toward suicide as one of the biggest barriers to prevention. In addition, researchers have found that the stigma associated with suicide “spills over” to the bereaved family members. Doka10,11 refers to “disenfranchised grief,” in which bereaved individuals receive the message that their grief is not legitimate, and as a result, they are likely to internalize this view. Studies have shown that individuals bereaved by suicide are also stigmatized, and are believed to be more psychologically disturbed, less likable, more blameworthy, more ashamed, and more in need of professional help than other bereaved individuals.8,12-20

These judgments often mirror suicide loss survivors’ self-punitive assessments, which then become exacerbated by and intertwined with both externally imposed and internalized stigma. Thus, it is not uncommon for survivors of suicide loss to question their own right to grieve, to report low expectations of social support, and to feel compelled to deny or hide the mode of death. To the extent that they are actively grieving, survivors of suicide loss often feel that they must do so in isolation. Thus, the perception of stigma, whether external or internalized, can have a profound effect on decisions about disclosure, requesting support, and ultimately on one’s ability to integrate the loss. Indeed, Feigelman et al21 found that stigmatization after suicide was specifically associated with ongoing grief difficulties, depression, and suicidal ideation.

Continue to: Traumatic nature of suicide

Traumatic nature of suicide. Suicide loss is also quite traumatic, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms such as shock, horror, disbelief, and intrusive/perseverative thoughts and questions, particularly in the earlier stages of grief, are common. Sanford et al3 found that the higher the level of “perceived closeness” to the deceased, the more likely that survivors of suicide loss would experience PTSD symptoms. In addition, the dramatic loss of social support following a suicide loss may itself be traumatic, which can serve to compound these difficulties. Notably, Sanford et al3 found that even for those survivors of suicide loss in treatment who endorsed PTSD symptoms, many of their treating clinicians did not assess or diagnose this disorder, thus missing an important component for treatment.

Increased risk for suicidality. Studies have shown that individuals who have lost a loved one to suicide are themselves at heightened risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors.22-27 Therefore, an assessment for suicide risk is always advisable. However, it is important to note that suicidal ideation is not uncommon and can serve different functions for survivors of suicide loss without necessarily progressing to a plan for acting on such ideations. Survivors of suicide loss may wish to “join” their loved one; to understand or identify with the mental state of the deceased; to punish themselves for failing to prevent the suicide; or to end their own pain through death. Therefore, it is crucial to assess the nature and function of expressed ideation (in addition to the presence or absence of plans) before assigning the level of risk.

Elements of suicide grief

After the loss of a loved one to suicide, the path to healing is often complex, with survivors of suicide loss enduring the following challenges:

Existential assumptions are shattered. Several authors28-30 have found that suicide loss is also likely to shatter survivors’ existential assumptions regarding their worldviews, roles, and identities, as well as religious and spiritual beliefs. As one survivor of suicide loss in my practice noted, “The world is gone, nothing is predictable anymore, and it’s no longer safe to assume anything.” Others have described feeling “fragmented” in ways they had never before experienced, and many have reported difficulties in “trusting” their own judgment, the stability of the world, and relationships. “Why?” becomes an emergent and insistent question in the survivor’s efforts to understand the suicide and (ideally) reassemble a coherent narrative around the loss.

Increased duration and intensity of grief. The duration of the grief process is likely to be affected by the traumatic nature of suicide loss, the differential social support accorded to its survivors, and the difficulty in finding systems that can validate and normalize the unique elements in suicide bereavement. The stigmatized reactions of others, particularly when internalized, can present barriers to the processing of grief. In addition, the intensity of the trauma and existential impact, as well as the perseverative nature of several of the unique themes (Box 1), can also prolong the processing and increase the intensity of suicide grief. Clinicians would do well to recognize the relatively “normative” nature of the increased duration and intensity, rather than seeing it as immediately indicative of a DSM diagnosis of complicated/prolonged grief disorder.

Box 1

Common themes in the suicide grief process

Several common themes are likely to emerge during the suicide grief process. Guilt and a sense of failure—around what one did and did not do—can be pervasive and persistent, and are often present even when not objectively warranted.

Anger and blame directed towards the deceased, other family members, and clinicians who had been treating the deceased may also be present, and may be used in efforts to deflect guilt. Any of these themes may be enlisted to create a deceptively simple narrative for understanding the reasons for the suicide.

Shame is often present, and certainly exacerbated by both external and internalized stigma. Feelings of rejection, betrayal, and abandonment by the deceased are also common, as well as fear/hypervigilance regarding the possibility of losing others to suicide. Given the intensity of suicide grief, it has been my observation that there may also be fear in relation to one's own mental status, as many otherwise healthy survivors of suicide loss have described feeling like they're "going crazy." Finally, there may also be relief, particularly if the deceased had been suffering from chronic psychiatric distress or had been cruel or abusive.

Continue to: Family disruption

Family disruption. It is not uncommon for a suicide loss to result in family disruption.6,31-32 This may manifest in the blaming of family members for “sins of omission or commission,”6 conflicts around the disclosure of the suicide both within and outside of the family, discordant grieving styles, and difficulties in understanding and attending to the needs of one’s children while grieving oneself.

Despite the common elements often seen in suicide grief, it is crucial to recognize that this process is not “one size fits all.” Not only are there individual variants, but Grad et al33 found gender-based differences in grieving styles, and cultural issues such as the “meanings” assigned to suicide, and culturally sanctioned grief rituals and behaviors that are also likely to affect how grief is experienced and expressed. In addition, personal variants such as closeness/conflicts with the deceased, histories of previous trauma or loss, pre-existing psychiatric disorders, and attachment orientation34 are likely to impact the grief process.

Losing close friends and colleagues may be similarly traumatic, but these survivors of suicide loss often receive even less social support than those who have kinship losses. Finally, when a suicide loss occurs in a professional capacity (such as the loss of a patient), this is likely to have many additional implications for one’s professional functions and identity.35

Interventions to help survivors

Several goals and “tasks” are involved in the suicide bereavement process (Box 21,6,30,36-40). These can be achieved through the following interventions: Support groups. Many survivors find that support groups that focus on suicide loss are extremely helpful, and research has supported this.1,4,41-44 Interactions with other suicide loss survivors provide hope, connection, and an “antidote” to stigma and shame. Optimally, group facilitators provide education, validation and normalization of the grief trajectory, and facilitate the sharing of both loss experiences and current functioning between group members. As a result, group participants often report renewed connections, increased efficacy in giving and accepting support, and decreased distress (including reductions in PTSD and depressive symptoms). The American Association of Suicidology (www.suicidology.org) and American Foundation of Suicide Prevention (www.afsp.org) provide contact information for suicide loss survivor groups (by geographical area) as well as information about online support groups.

Box 2

Goals and 'tasks' in suicide bereavement

The following goals and "tasks" should be part of the process of suicide bereavement:

- Reduce symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychiatric disorders. Given the traumatic nature of the loss, an important goal is to understand and reduce posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychiatric symptoms, and incrementally improving functionality in relation to these.