User login

Psychosis and stroke are arguably the most serious acute threats to the integrity of the brain, and consequently the mind. Both are unquestionably associated with a grave outcome the longer their treatment is delayed.1,2

While the management of stroke has been elevated to the highest emergent priority because of the progressively deleterious impact of thrombotic ischemia in one of the cerebral arteries, rapid intervention for acute psychosis has never been regarded as an urgent neurologic condition with severe threats to the brain’s structure and function.3,4 There is extensive literature on the serious consequences of a long duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), including treatment resistance, frequent re-hospitalizations, more negative symptoms, and greater disability.5

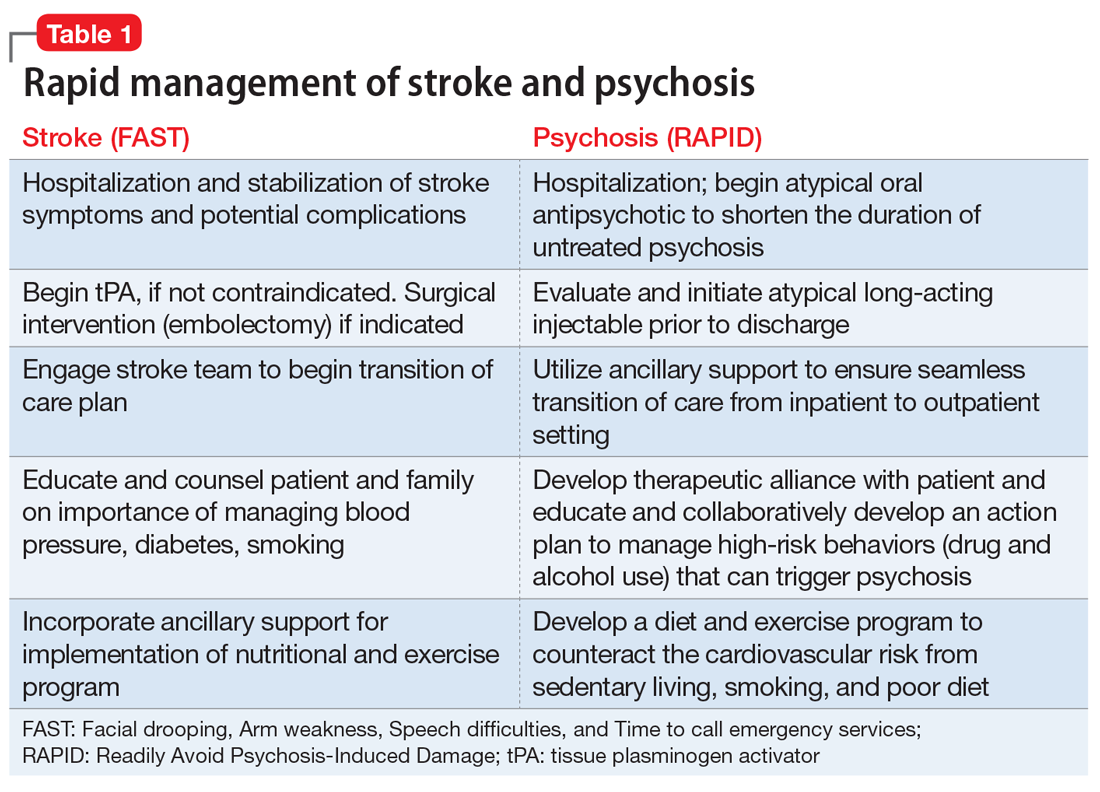

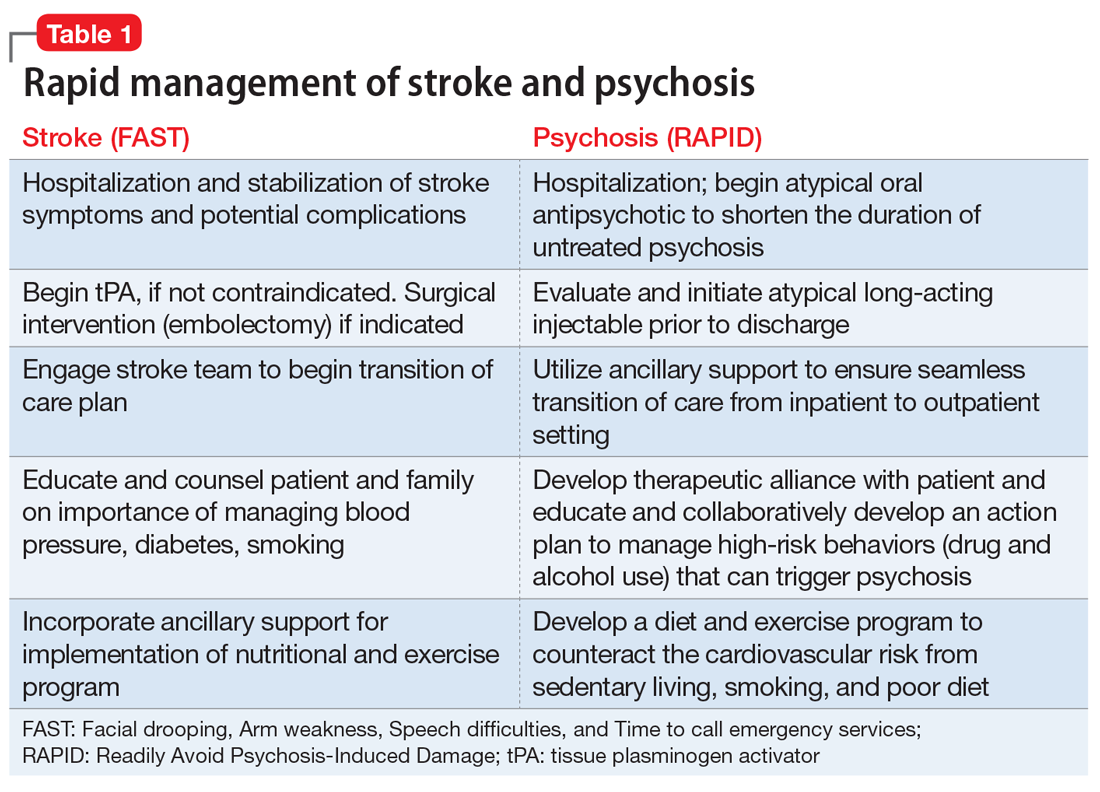

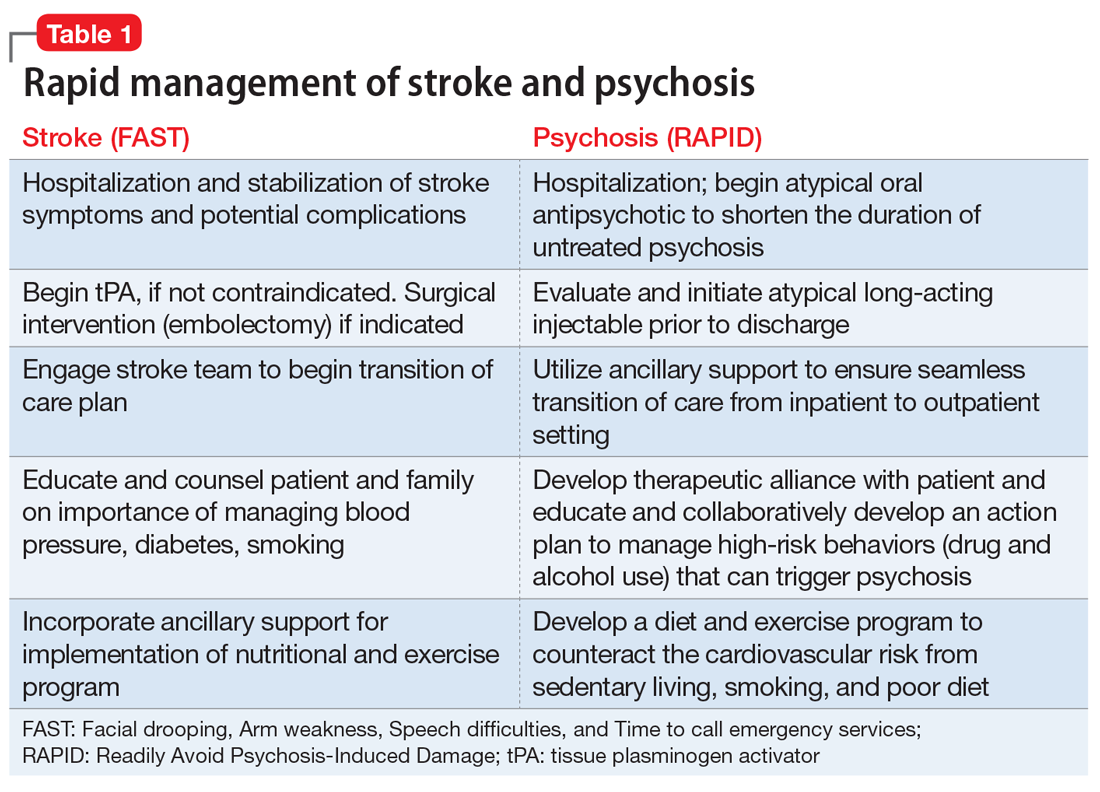

Physical paralysis from a stroke receives much more attention than “mental paralysis” of psychosis. Both must be rapidly treated, whether for the regional ischemia to brain tissue following a stroke or for the neurotoxicity of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress that lead to widespread neurodegeneration during psychosis.6 While an acronym for the quick recognition of a stroke (FAST: Facial drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulties, and Time to call emergency services) is well established, no acronym for the urgency to treat psychosis has been developed. We propose the acronym RAPID (Readily Avoid Psychosis-Induced Damage). The acronym RAPID would hopefully expedite the urgently needed pharmacotherapeutic and psychosocial intervention in psychosis to halt ongoing brain tissue loss.

It is ironic that the legal obstacles for immediate treatment, which do not exist for stroke, often delay administering antipsychotic medication to patients with anosognosia (a neurologic delusional belief that one is not ill, leading to refusal of treatment) for their psychosis and end up harming patients by prolonging their DUP until a court order is obtained to force brain-saving treatment. Frequent psychotic relapses due to nonadherence with medications are also a very common cause for prolonged DUP due to the inexplicable reluctance of some psychiatric practitioners to employ a long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAI) medication as soon as possible after the onset of psychosis to circumvent subsequent relapses due to the very high risk of poor adherence. Table 1 describes the optimal management of both stroke and acute psychosis once they are rapidly diagnosed, thanks to the FAST and RAPID reminders.

Tragically, the treatments of the mind have become falsely disengaged from the brain, the physical organ whose neurons, electrical impulses, synapses, and neurotransmitters generate the mind with its advanced human functions, such as self-awareness, will, thoughts, mood, speech, executive functions, memories, and social cognition. Recent editorials have challenged psychiatric practitioners to behave like cardiologists7 and oncologists8 by aggressively treating first-episode psychosis to prevent ongoing neurodegeneration due to recurrences. The brain loses 1% of its brain volume (~11 ml) after the first psychotic episode,8 which represents hundreds of millions of cells, billions of synapses, and substantial myelin. A second psychotic episode causes significant additional neuropil and white matter fiber damage and represents a different stage of schizophrenia9 with more severe tissue loss and disruption of neural pathways that trigger the process of treatment resistance and functional disability. Ensuring adherence with LAI antipsychotic formulations immediately after the first psychotic episode may allow many patients with schizophrenia to achieve a relapse-free remission and to return to their baseline functioning.10

In addition to significant brain tissue loss during psychotic episodes, mortality is also a very high risk following discharge from the first hospitalization for psychosis.11 LAI second-generation antipsychotic medications have been shown to be associated with lower mortality and neuroprotective effects,12 compared with oral or injectable first-generation antipsychotics. The highest mortality rate was reported to be associated with the lack of any antipsychotic medication,12 underscoring how untreated psychosis can be fatal.

Bottom line: Rapid treatment of stroke and psychosis is an absolute imperative for minimizing brain damage that respectively leads to physical or mental disability. The acronyms FAST and RAPID are essential reminders of the urgency needed to halt progressive neurodegeneration in those 2 devastating acute threats to the integrity of brain and mind. Intensive physical, psychological, and social rehabilitation must follow the acute treatment of stroke and psychosis, and the prevention of any recurrence is an absolute must. For psychosis, the use of a LAI second-generation antipsychotic before hospital discharge from a first episode of psychosis can be disease-modifying, with a more benign illness trajectory and outcome than the devastating deterioration that follows repetitive psychotic relapse, most often due to nonadherence with oral medications.

Continue to: Psychosis should be conceptualized as...

Psychosis should be conceptualized as a “stroke of the mind,” and it can be prevented in most patients with schizophrenia by adopting injectable antipsychotics as early after the onset of psychosis as possible. Yet, starting a LAI antipsychotic drug in first-episode psychosis before hospital discharge is rarely done, and the few patients who currently receive LAIs (10% of U.S. patients) generally receive them after multiple episodes and a protracted DUP. That’s like calling the fire department when much of the house has turned to ashes, instead of calling them when the first small flame is noticed. It makes so much sense, but the decades-old practice of postponing the use of LAIs continues to ruin the lives of young persons in the prime of life. By changing our practice habits to early use of LAIs, we have nothing to lose and our patients with psychosis may be spared a lifetime of suffering, poverty, stigma, incarceration, and functional disability. Wouldn’t we want to avoid that atrocious outcome for our own family members if they develop schizophrenia?

1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67-e492.

2. Cechnicki A, Cichocki Ł, Kalisz A, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and the course of schizophrenia in a 20-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(3):420-425.

3. Davis J, Moylan S, Harvey BH, et al. Neuroprogression in schizophrenia: pathways underpinning clinical staging and therapeutic corollaries. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(6):512-529.

4. Olabi B, Ellison-Wright I, McIntosh AM, et al. Are there progressive brain changes in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(1):88-96.

5. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

6. Najjar S, Pearlman DM. Neuroinflammation and white matter pathology in schizophrenia: systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(1):102-112.

7. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

8. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

9. McGorry P, Nelson B. Why we need a transdiagnostic staging approach to emerging psychopathology, early diagnosis, and treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):191-192.

10. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

11. Nasrallah HA. The crisis of poor physical health and early mortality of psychiatric patients. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(4):7-8,11.

12. Nasrallah HA. Triple advantages of injectable long acting second generation antipsychotics: relapse prevention, neuroprotection, and lower mortality. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:69-70.

Psychosis and stroke are arguably the most serious acute threats to the integrity of the brain, and consequently the mind. Both are unquestionably associated with a grave outcome the longer their treatment is delayed.1,2

While the management of stroke has been elevated to the highest emergent priority because of the progressively deleterious impact of thrombotic ischemia in one of the cerebral arteries, rapid intervention for acute psychosis has never been regarded as an urgent neurologic condition with severe threats to the brain’s structure and function.3,4 There is extensive literature on the serious consequences of a long duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), including treatment resistance, frequent re-hospitalizations, more negative symptoms, and greater disability.5

Physical paralysis from a stroke receives much more attention than “mental paralysis” of psychosis. Both must be rapidly treated, whether for the regional ischemia to brain tissue following a stroke or for the neurotoxicity of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress that lead to widespread neurodegeneration during psychosis.6 While an acronym for the quick recognition of a stroke (FAST: Facial drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulties, and Time to call emergency services) is well established, no acronym for the urgency to treat psychosis has been developed. We propose the acronym RAPID (Readily Avoid Psychosis-Induced Damage). The acronym RAPID would hopefully expedite the urgently needed pharmacotherapeutic and psychosocial intervention in psychosis to halt ongoing brain tissue loss.

It is ironic that the legal obstacles for immediate treatment, which do not exist for stroke, often delay administering antipsychotic medication to patients with anosognosia (a neurologic delusional belief that one is not ill, leading to refusal of treatment) for their psychosis and end up harming patients by prolonging their DUP until a court order is obtained to force brain-saving treatment. Frequent psychotic relapses due to nonadherence with medications are also a very common cause for prolonged DUP due to the inexplicable reluctance of some psychiatric practitioners to employ a long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAI) medication as soon as possible after the onset of psychosis to circumvent subsequent relapses due to the very high risk of poor adherence. Table 1 describes the optimal management of both stroke and acute psychosis once they are rapidly diagnosed, thanks to the FAST and RAPID reminders.

Tragically, the treatments of the mind have become falsely disengaged from the brain, the physical organ whose neurons, electrical impulses, synapses, and neurotransmitters generate the mind with its advanced human functions, such as self-awareness, will, thoughts, mood, speech, executive functions, memories, and social cognition. Recent editorials have challenged psychiatric practitioners to behave like cardiologists7 and oncologists8 by aggressively treating first-episode psychosis to prevent ongoing neurodegeneration due to recurrences. The brain loses 1% of its brain volume (~11 ml) after the first psychotic episode,8 which represents hundreds of millions of cells, billions of synapses, and substantial myelin. A second psychotic episode causes significant additional neuropil and white matter fiber damage and represents a different stage of schizophrenia9 with more severe tissue loss and disruption of neural pathways that trigger the process of treatment resistance and functional disability. Ensuring adherence with LAI antipsychotic formulations immediately after the first psychotic episode may allow many patients with schizophrenia to achieve a relapse-free remission and to return to their baseline functioning.10

In addition to significant brain tissue loss during psychotic episodes, mortality is also a very high risk following discharge from the first hospitalization for psychosis.11 LAI second-generation antipsychotic medications have been shown to be associated with lower mortality and neuroprotective effects,12 compared with oral or injectable first-generation antipsychotics. The highest mortality rate was reported to be associated with the lack of any antipsychotic medication,12 underscoring how untreated psychosis can be fatal.

Bottom line: Rapid treatment of stroke and psychosis is an absolute imperative for minimizing brain damage that respectively leads to physical or mental disability. The acronyms FAST and RAPID are essential reminders of the urgency needed to halt progressive neurodegeneration in those 2 devastating acute threats to the integrity of brain and mind. Intensive physical, psychological, and social rehabilitation must follow the acute treatment of stroke and psychosis, and the prevention of any recurrence is an absolute must. For psychosis, the use of a LAI second-generation antipsychotic before hospital discharge from a first episode of psychosis can be disease-modifying, with a more benign illness trajectory and outcome than the devastating deterioration that follows repetitive psychotic relapse, most often due to nonadherence with oral medications.

Continue to: Psychosis should be conceptualized as...

Psychosis should be conceptualized as a “stroke of the mind,” and it can be prevented in most patients with schizophrenia by adopting injectable antipsychotics as early after the onset of psychosis as possible. Yet, starting a LAI antipsychotic drug in first-episode psychosis before hospital discharge is rarely done, and the few patients who currently receive LAIs (10% of U.S. patients) generally receive them after multiple episodes and a protracted DUP. That’s like calling the fire department when much of the house has turned to ashes, instead of calling them when the first small flame is noticed. It makes so much sense, but the decades-old practice of postponing the use of LAIs continues to ruin the lives of young persons in the prime of life. By changing our practice habits to early use of LAIs, we have nothing to lose and our patients with psychosis may be spared a lifetime of suffering, poverty, stigma, incarceration, and functional disability. Wouldn’t we want to avoid that atrocious outcome for our own family members if they develop schizophrenia?

Psychosis and stroke are arguably the most serious acute threats to the integrity of the brain, and consequently the mind. Both are unquestionably associated with a grave outcome the longer their treatment is delayed.1,2

While the management of stroke has been elevated to the highest emergent priority because of the progressively deleterious impact of thrombotic ischemia in one of the cerebral arteries, rapid intervention for acute psychosis has never been regarded as an urgent neurologic condition with severe threats to the brain’s structure and function.3,4 There is extensive literature on the serious consequences of a long duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), including treatment resistance, frequent re-hospitalizations, more negative symptoms, and greater disability.5

Physical paralysis from a stroke receives much more attention than “mental paralysis” of psychosis. Both must be rapidly treated, whether for the regional ischemia to brain tissue following a stroke or for the neurotoxicity of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress that lead to widespread neurodegeneration during psychosis.6 While an acronym for the quick recognition of a stroke (FAST: Facial drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulties, and Time to call emergency services) is well established, no acronym for the urgency to treat psychosis has been developed. We propose the acronym RAPID (Readily Avoid Psychosis-Induced Damage). The acronym RAPID would hopefully expedite the urgently needed pharmacotherapeutic and psychosocial intervention in psychosis to halt ongoing brain tissue loss.

It is ironic that the legal obstacles for immediate treatment, which do not exist for stroke, often delay administering antipsychotic medication to patients with anosognosia (a neurologic delusional belief that one is not ill, leading to refusal of treatment) for their psychosis and end up harming patients by prolonging their DUP until a court order is obtained to force brain-saving treatment. Frequent psychotic relapses due to nonadherence with medications are also a very common cause for prolonged DUP due to the inexplicable reluctance of some psychiatric practitioners to employ a long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAI) medication as soon as possible after the onset of psychosis to circumvent subsequent relapses due to the very high risk of poor adherence. Table 1 describes the optimal management of both stroke and acute psychosis once they are rapidly diagnosed, thanks to the FAST and RAPID reminders.

Tragically, the treatments of the mind have become falsely disengaged from the brain, the physical organ whose neurons, electrical impulses, synapses, and neurotransmitters generate the mind with its advanced human functions, such as self-awareness, will, thoughts, mood, speech, executive functions, memories, and social cognition. Recent editorials have challenged psychiatric practitioners to behave like cardiologists7 and oncologists8 by aggressively treating first-episode psychosis to prevent ongoing neurodegeneration due to recurrences. The brain loses 1% of its brain volume (~11 ml) after the first psychotic episode,8 which represents hundreds of millions of cells, billions of synapses, and substantial myelin. A second psychotic episode causes significant additional neuropil and white matter fiber damage and represents a different stage of schizophrenia9 with more severe tissue loss and disruption of neural pathways that trigger the process of treatment resistance and functional disability. Ensuring adherence with LAI antipsychotic formulations immediately after the first psychotic episode may allow many patients with schizophrenia to achieve a relapse-free remission and to return to their baseline functioning.10

In addition to significant brain tissue loss during psychotic episodes, mortality is also a very high risk following discharge from the first hospitalization for psychosis.11 LAI second-generation antipsychotic medications have been shown to be associated with lower mortality and neuroprotective effects,12 compared with oral or injectable first-generation antipsychotics. The highest mortality rate was reported to be associated with the lack of any antipsychotic medication,12 underscoring how untreated psychosis can be fatal.

Bottom line: Rapid treatment of stroke and psychosis is an absolute imperative for minimizing brain damage that respectively leads to physical or mental disability. The acronyms FAST and RAPID are essential reminders of the urgency needed to halt progressive neurodegeneration in those 2 devastating acute threats to the integrity of brain and mind. Intensive physical, psychological, and social rehabilitation must follow the acute treatment of stroke and psychosis, and the prevention of any recurrence is an absolute must. For psychosis, the use of a LAI second-generation antipsychotic before hospital discharge from a first episode of psychosis can be disease-modifying, with a more benign illness trajectory and outcome than the devastating deterioration that follows repetitive psychotic relapse, most often due to nonadherence with oral medications.

Continue to: Psychosis should be conceptualized as...

Psychosis should be conceptualized as a “stroke of the mind,” and it can be prevented in most patients with schizophrenia by adopting injectable antipsychotics as early after the onset of psychosis as possible. Yet, starting a LAI antipsychotic drug in first-episode psychosis before hospital discharge is rarely done, and the few patients who currently receive LAIs (10% of U.S. patients) generally receive them after multiple episodes and a protracted DUP. That’s like calling the fire department when much of the house has turned to ashes, instead of calling them when the first small flame is noticed. It makes so much sense, but the decades-old practice of postponing the use of LAIs continues to ruin the lives of young persons in the prime of life. By changing our practice habits to early use of LAIs, we have nothing to lose and our patients with psychosis may be spared a lifetime of suffering, poverty, stigma, incarceration, and functional disability. Wouldn’t we want to avoid that atrocious outcome for our own family members if they develop schizophrenia?

1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67-e492.

2. Cechnicki A, Cichocki Ł, Kalisz A, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and the course of schizophrenia in a 20-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(3):420-425.

3. Davis J, Moylan S, Harvey BH, et al. Neuroprogression in schizophrenia: pathways underpinning clinical staging and therapeutic corollaries. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(6):512-529.

4. Olabi B, Ellison-Wright I, McIntosh AM, et al. Are there progressive brain changes in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(1):88-96.

5. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

6. Najjar S, Pearlman DM. Neuroinflammation and white matter pathology in schizophrenia: systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(1):102-112.

7. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

8. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

9. McGorry P, Nelson B. Why we need a transdiagnostic staging approach to emerging psychopathology, early diagnosis, and treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):191-192.

10. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

11. Nasrallah HA. The crisis of poor physical health and early mortality of psychiatric patients. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(4):7-8,11.

12. Nasrallah HA. Triple advantages of injectable long acting second generation antipsychotics: relapse prevention, neuroprotection, and lower mortality. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:69-70.

1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67-e492.

2. Cechnicki A, Cichocki Ł, Kalisz A, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and the course of schizophrenia in a 20-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(3):420-425.

3. Davis J, Moylan S, Harvey BH, et al. Neuroprogression in schizophrenia: pathways underpinning clinical staging and therapeutic corollaries. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(6):512-529.

4. Olabi B, Ellison-Wright I, McIntosh AM, et al. Are there progressive brain changes in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70(1):88-96.

5. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

6. Najjar S, Pearlman DM. Neuroinflammation and white matter pathology in schizophrenia: systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(1):102-112.

7. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

8. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

9. McGorry P, Nelson B. Why we need a transdiagnostic staging approach to emerging psychopathology, early diagnosis, and treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):191-192.

10. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

11. Nasrallah HA. The crisis of poor physical health and early mortality of psychiatric patients. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(4):7-8,11.

12. Nasrallah HA. Triple advantages of injectable long acting second generation antipsychotics: relapse prevention, neuroprotection, and lower mortality. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:69-70.