User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Comments & Controversies

A broken system

I was relieved to see your article “I have a dream … for psychiatry” (From the Editor,

Psychiatry does need better treatments. On the other hand, we do have many effective treatments that simply are not available to many.

This brings me to ask, how is it that overall psychiatric care is actually worse now than in, say, the late 20th century? There might have been fewer psychopharmacologic treatments available back then, but there was overall better access to care, and a largely intact system. For lower-functioning patients, such as those who are homeless or in jail, I do believe this is the case, as I will explain. But even higher-functioning private practice patients are affected by the shortage of psychiatrists.

In 2022, the system is broken. Funding is abysmal, and numerous psychiatric hospital closures across the United States have led to simply no reasonable local access for many.

Prisons and jails are the new treatment centers! As you have rightly pointed out, by being housed in prisons with violent criminals, severely mentally ill patients are subjected to physical and sexual abuse daily.

Laws meant to protect mentally ill individuals, such as psychiatric holds, are often not implemented. Severely mentally ill patients can meet the criteria to be categorized as a danger to self, danger to others, or gravely disabled, but can’t get crisis intervention. Abandoning these patients to the streets is, in part, fueling homelessness and drug addiction.

In my opinion, the broken system is the fundamental problem that needs to be solved. Although I long for novel treatments, if there were such breakthrough treatments available—as exciting as that may be—how could they be delivered effectively in our current broken system? In other words, how can these patients be treated with neuroscientific breakthrough treatments without the necessary psychiatric infrastructure? We are at such an extreme, I worry for our specialty.

In Karl Menninger’s The Crime of Punishment, one passage stuck with me: “I suspect that all the crimes committed by all the jailed criminals do not equal in total social damage that of the crimes committed against them.”1 I have often wondered how that relates to the criminalized mentally ill, who are punished daily by being in horrific, abusive, unsafe settings. What truly is their crime? Being mentally ill?

Given how the system is now engineered to throw these patients in prison and allow them to be abused instead of admitting them to a psychiatric hospital, one must wonder: How did this come to be? Could it go beyond stigma to actual hatred and contempt for these people? After all, as psychiatrists, the abuse is in plain sight.

Finally, I have often wondered why there has not been a robust psychiatric organizational response to the breakdown in access to patient care. I can only hope that one day there can be.

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Thank you for your comments on my editorial. I sense that you are quite frustrated with the current status of psychiatry, and are longing for improvements.

I do share some of your concerns about: 1) society turning a blind eye to the mentally ill (and I have written about that from the angle of tragically high suicide rate1); 2) the hatred and contempt embedded within stigma of serious mental disorders; 3) the deplorable criminalization and trans-institutionalization of our patients from state hospitals to jails and prisons; 4) the shortage of acute psychiatric beds in many communities because the wards were converted to highly lucrative, procedure-oriented programs; 5) the dysfunctional public mental health system; and 6) the need for new and novel treatments.

However, despite those challenges, I remain optimistic that the future of psychiatry is bright because I keep abreast of the stunning neuroscience advances every day that will be translated into psychiatric treatments in the future. I envision a time when these brain research breakthroughs will lead to important clinical applications, such as a better diagnostic system using biomarkers (precision psychiatry), not just a cluster of clinical symptoms, and to brave new therapeutic interventions with superior efficacy and better safety. I would not be surprised if psychiatry and neurology will again merge after decades of separation, and that will certainly erase much of the stigma of disorders of the mind, which is the virtual brain.

Please hang in there, and do not let your patients perceive a sense of resignation and pessimism about psychiatry. Both our patients and psychiatrists need to be uplifted by hope for a better future.

1. Menninger K. The Crime of Punishment. Viking Adult; 1968.

2. Nasrallah HA. The scourge of societal anosognosia about the mentally ill. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(6):19,23-24.

A broken system

I was relieved to see your article “I have a dream … for psychiatry” (From the Editor,

Psychiatry does need better treatments. On the other hand, we do have many effective treatments that simply are not available to many.

This brings me to ask, how is it that overall psychiatric care is actually worse now than in, say, the late 20th century? There might have been fewer psychopharmacologic treatments available back then, but there was overall better access to care, and a largely intact system. For lower-functioning patients, such as those who are homeless or in jail, I do believe this is the case, as I will explain. But even higher-functioning private practice patients are affected by the shortage of psychiatrists.

In 2022, the system is broken. Funding is abysmal, and numerous psychiatric hospital closures across the United States have led to simply no reasonable local access for many.

Prisons and jails are the new treatment centers! As you have rightly pointed out, by being housed in prisons with violent criminals, severely mentally ill patients are subjected to physical and sexual abuse daily.

Laws meant to protect mentally ill individuals, such as psychiatric holds, are often not implemented. Severely mentally ill patients can meet the criteria to be categorized as a danger to self, danger to others, or gravely disabled, but can’t get crisis intervention. Abandoning these patients to the streets is, in part, fueling homelessness and drug addiction.

In my opinion, the broken system is the fundamental problem that needs to be solved. Although I long for novel treatments, if there were such breakthrough treatments available—as exciting as that may be—how could they be delivered effectively in our current broken system? In other words, how can these patients be treated with neuroscientific breakthrough treatments without the necessary psychiatric infrastructure? We are at such an extreme, I worry for our specialty.

In Karl Menninger’s The Crime of Punishment, one passage stuck with me: “I suspect that all the crimes committed by all the jailed criminals do not equal in total social damage that of the crimes committed against them.”1 I have often wondered how that relates to the criminalized mentally ill, who are punished daily by being in horrific, abusive, unsafe settings. What truly is their crime? Being mentally ill?

Given how the system is now engineered to throw these patients in prison and allow them to be abused instead of admitting them to a psychiatric hospital, one must wonder: How did this come to be? Could it go beyond stigma to actual hatred and contempt for these people? After all, as psychiatrists, the abuse is in plain sight.

Finally, I have often wondered why there has not been a robust psychiatric organizational response to the breakdown in access to patient care. I can only hope that one day there can be.

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Thank you for your comments on my editorial. I sense that you are quite frustrated with the current status of psychiatry, and are longing for improvements.

I do share some of your concerns about: 1) society turning a blind eye to the mentally ill (and I have written about that from the angle of tragically high suicide rate1); 2) the hatred and contempt embedded within stigma of serious mental disorders; 3) the deplorable criminalization and trans-institutionalization of our patients from state hospitals to jails and prisons; 4) the shortage of acute psychiatric beds in many communities because the wards were converted to highly lucrative, procedure-oriented programs; 5) the dysfunctional public mental health system; and 6) the need for new and novel treatments.

However, despite those challenges, I remain optimistic that the future of psychiatry is bright because I keep abreast of the stunning neuroscience advances every day that will be translated into psychiatric treatments in the future. I envision a time when these brain research breakthroughs will lead to important clinical applications, such as a better diagnostic system using biomarkers (precision psychiatry), not just a cluster of clinical symptoms, and to brave new therapeutic interventions with superior efficacy and better safety. I would not be surprised if psychiatry and neurology will again merge after decades of separation, and that will certainly erase much of the stigma of disorders of the mind, which is the virtual brain.

Please hang in there, and do not let your patients perceive a sense of resignation and pessimism about psychiatry. Both our patients and psychiatrists need to be uplifted by hope for a better future.

A broken system

I was relieved to see your article “I have a dream … for psychiatry” (From the Editor,

Psychiatry does need better treatments. On the other hand, we do have many effective treatments that simply are not available to many.

This brings me to ask, how is it that overall psychiatric care is actually worse now than in, say, the late 20th century? There might have been fewer psychopharmacologic treatments available back then, but there was overall better access to care, and a largely intact system. For lower-functioning patients, such as those who are homeless or in jail, I do believe this is the case, as I will explain. But even higher-functioning private practice patients are affected by the shortage of psychiatrists.

In 2022, the system is broken. Funding is abysmal, and numerous psychiatric hospital closures across the United States have led to simply no reasonable local access for many.

Prisons and jails are the new treatment centers! As you have rightly pointed out, by being housed in prisons with violent criminals, severely mentally ill patients are subjected to physical and sexual abuse daily.

Laws meant to protect mentally ill individuals, such as psychiatric holds, are often not implemented. Severely mentally ill patients can meet the criteria to be categorized as a danger to self, danger to others, or gravely disabled, but can’t get crisis intervention. Abandoning these patients to the streets is, in part, fueling homelessness and drug addiction.

In my opinion, the broken system is the fundamental problem that needs to be solved. Although I long for novel treatments, if there were such breakthrough treatments available—as exciting as that may be—how could they be delivered effectively in our current broken system? In other words, how can these patients be treated with neuroscientific breakthrough treatments without the necessary psychiatric infrastructure? We are at such an extreme, I worry for our specialty.

In Karl Menninger’s The Crime of Punishment, one passage stuck with me: “I suspect that all the crimes committed by all the jailed criminals do not equal in total social damage that of the crimes committed against them.”1 I have often wondered how that relates to the criminalized mentally ill, who are punished daily by being in horrific, abusive, unsafe settings. What truly is their crime? Being mentally ill?

Given how the system is now engineered to throw these patients in prison and allow them to be abused instead of admitting them to a psychiatric hospital, one must wonder: How did this come to be? Could it go beyond stigma to actual hatred and contempt for these people? After all, as psychiatrists, the abuse is in plain sight.

Finally, I have often wondered why there has not been a robust psychiatric organizational response to the breakdown in access to patient care. I can only hope that one day there can be.

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Thank you for your comments on my editorial. I sense that you are quite frustrated with the current status of psychiatry, and are longing for improvements.

I do share some of your concerns about: 1) society turning a blind eye to the mentally ill (and I have written about that from the angle of tragically high suicide rate1); 2) the hatred and contempt embedded within stigma of serious mental disorders; 3) the deplorable criminalization and trans-institutionalization of our patients from state hospitals to jails and prisons; 4) the shortage of acute psychiatric beds in many communities because the wards were converted to highly lucrative, procedure-oriented programs; 5) the dysfunctional public mental health system; and 6) the need for new and novel treatments.

However, despite those challenges, I remain optimistic that the future of psychiatry is bright because I keep abreast of the stunning neuroscience advances every day that will be translated into psychiatric treatments in the future. I envision a time when these brain research breakthroughs will lead to important clinical applications, such as a better diagnostic system using biomarkers (precision psychiatry), not just a cluster of clinical symptoms, and to brave new therapeutic interventions with superior efficacy and better safety. I would not be surprised if psychiatry and neurology will again merge after decades of separation, and that will certainly erase much of the stigma of disorders of the mind, which is the virtual brain.

Please hang in there, and do not let your patients perceive a sense of resignation and pessimism about psychiatry. Both our patients and psychiatrists need to be uplifted by hope for a better future.

1. Menninger K. The Crime of Punishment. Viking Adult; 1968.

2. Nasrallah HA. The scourge of societal anosognosia about the mentally ill. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(6):19,23-24.

1. Menninger K. The Crime of Punishment. Viking Adult; 1968.

2. Nasrallah HA. The scourge of societal anosognosia about the mentally ill. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(6):19,23-24.

Assessing imminent suicide risk: What about future planning?

A patient who has the ability to plan for their future can be reassuring for a clinician who is conducting an imminent suicide risk evaluation. However, that patient may report future plans even as they are contemplating suicide. Therefore, this variable should not be simplified categorically to the mere presence or absence of future plans. Such plans, and the process by which they are produced, should be examined more closely. In this article, we explore the relationship between a patient’s intent to die by suicide in the near future and their ability to maintain future planning. We also use case examples to highlight certain characteristics that may allow future planning to be integrated more reliably into the assessment of imminent risk of suicide.

An inherent challenge

Suicide risk assessment can be challenging due to the numerous factors that can contribute to a patient’s suicidal intent.1 Some individuals don’t seek help when they develop suicidal thoughts, and even among those who do, recognizing who may be at greater risk is not an easy task. Sometimes, this leads to inadequate interventions and a subsequent failure to ensure safety, or to an overreaction and unnecessary hospitalization.

A common difficulty is a patient’s unwillingness to cooperate with the examination.2 Some patients do not present voluntarily, while others may seek help but then conceal suicidal intent. In a sample of 66 psychotherapy patients who reported concealing suicidal ideation from their therapist and provided short essay responses explaining their motives for doing so, approximately 70% said fear of involuntary hospitalization was their motive to hide those thoughts from their doctor.3 Other reasons for concealment are shame, stigma, embarrassment, fear of rejection, and loss of autonomy.3-5 Moreover, higher levels of suicidal ideation are associated with treatment avoidance.6 Therefore, it is important to improve suicide predictability independent of the patient report. In a survey of 1,150 emergency physicians in Australasia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, the need for evidence-based guidelines on when to hospitalize a patient at risk for suicide was ranked as the 7th-highest priority.7 There are limitations to using suicide risk assessment scales,8,9 because scales designed to have high sensitivity are less specific, and those with high specificity fail to identify individuals at high risk.9,10 Most of the research conducted in this area has focused on the risk of suicide in 2 to 6 months, and not on imminent risk.11

What is ‘imminent’ risk?

There is no specific time definition for “imminent risk,” but the Lifeline Standards, Trainings, and Practices Subcommittee, a group of national and international experts in suicide prevention, defines imminent risk of suicide as the belief that there is a “close temporal connection between the person’s current risk status and actions that could lead to his/her suicide.”12 Practically, suicide could be considered imminent when it occurs within a few days of the evaluation. However, suicide may take place within a few days of an evaluation due to new life events or impulsive actions, which may explain why imminent risk of suicide can be difficult to define and predict. In clinical practice, there is little evidence-based knowledge about estimating imminent risk. Recent studies have explored certain aspects of a patient’s history in the attempt to improve imminent risk predictability.13 In light of the complexity of this matter and the lack of widely validated tools, clinicians are encouraged to share their experience with other clinicians while the efforts to advance evidence-based knowledge and tools continue.

The function of future planning

Future planning is a mental process embedded in several crucial executive functions. It operates on a daily basis to organize, prioritize, and carry out tasks to achieve day-to-day and more distant future goals. Some research has found that a decreased ability to generate positive future thoughts is linked to increased suicide risk in the long term.14-17 Positive future planning can be affected by even minor fluctuations in mood because the additional processing capacity needed during these mood changes may limit one’s ability to generate positive future thoughts.18 Patients experiencing mood episodes are known to experience cognitive dysfunctions.19-21 However, additional measurable cognitive changes have been detected in patients who are suicidal. For example, in a small study (N = 33) of patients with depression, those who were experiencing suicidal thoughts underperformed on several measures of executive functioning compared to patients with no suicidal ideation.22

However, when addressing imminent rather than future suicide risk, even neutral future plans—such as day-to-day plans or those addressing barriers to treatment—can be a meaningful indicator of the investment in one’s future beyond a potential near-term suicide, and therefore can be explored to further inform the risk evaluation. Significant mental resources can be consumed due to the level of distress associated with contemplating suicide, and therefore patients may have a reduced capacity for day-to-day planning. Thus, serious suicide contemplation is less likely in the presence of typical future planning.

Continue to: Characteristics of future planning...

Characteristics of future planning

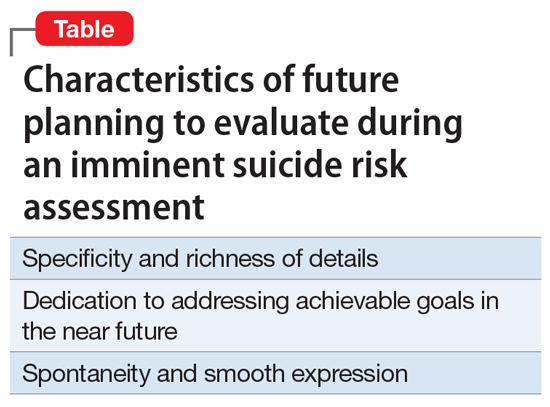

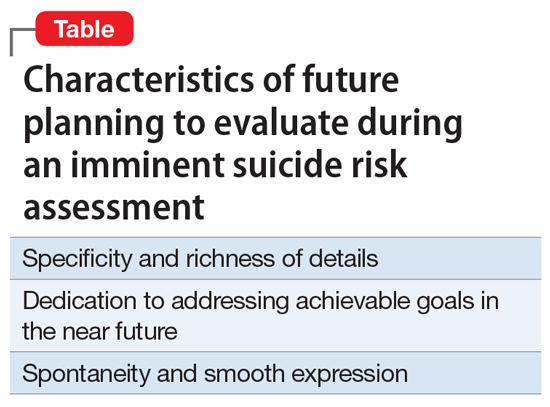

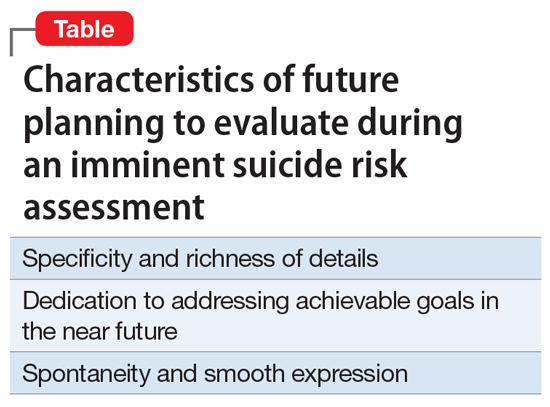

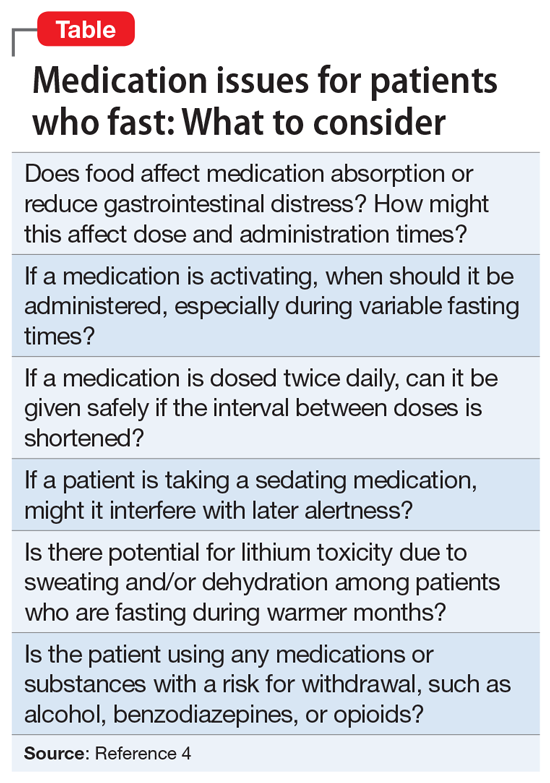

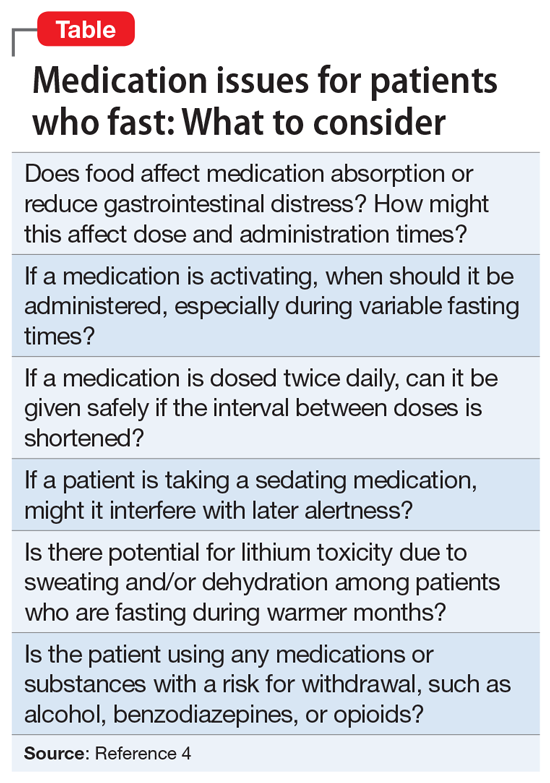

Some patients may pretend to engage in future planning to indicate the absence of suicidal intent. This necessitates a more nuanced assessment of future plans beyond whether they exist or not by examining the genuineness of such plans, and the authenticity of the process by which they are produced. The Table lists 3 characteristics of future plans/future planning that, based on our clinical experience, can be helpful to evaluate during an imminent suicide risk evaluation. These are described in the following case examples.

Specificity and richness of details

CASE 1

Mr. A, a college student, presents to the emergency department (ED) complaining of depression and suicidal thoughts that he is able to dismiss. He would like to avoid starting a medication because he has finals in 2 weeks and is worried about adverse effects. He learned about cognitive-behavioral therapy and is interested in getting a referral to a specific office because it is located within a walking distance from campus and easy for him to access because he does not own a car.

The volume of details expressed in a patient’s future plans is important. The more detailed these plans are, the more likely the patient is invested in them. Attendance to the details, especially when addressing expected barriers to treatment, such as transportation, can be evidence of genuine future planning and subsequently of low imminent suicide risk. Spreng et al23 found that autobiographic plans that are more specific and richer in detail recruit additional brain regions that are not recruited in plans that are sparsely detailed or constructed from more generalized representations.

CASE 2

An ambulance transports Ms. B, age 42, from a primary care clinic to the ED because she has been having suicidal thoughts, with a plan to hang herself, for the past 2 days. During the evaluation, Ms. B denies having further suicidal thoughts and declines inpatient admission. She claims that she cannot be away from her children because she is their primary caretaker. Collateral information reveals that Ms. B’s mother has been caring for her children for the last 2 weeks because Ms. B has been too depressed to do so. She continues to refuse admission and is in tears while trying to explain how her absence due to inpatient treatment will be detrimental to her children. Eventually, she angrily accuses the clinician of abusing her children by forcing her to be hospitalized.

In an effort to conceal suicidal intent, patients may present obligations or excuses that would be an obstacle to psychiatric hospitalization. This might give a false perception of intact future planning. However, in these cases, patients often fail to volunteer details about their future plans or show evidence for actual attendance to their obligations. Due to the lack of tangible details to explain the negative effects of inpatient treatment, patients may compensate by using an exaggerated emotional response, with a strong emotional attachment to the obligation and severe distress over their potential inability to fulfill it due to a psychiatric hospitalization. This may contribute to concealing suicidal intent in a different way. A patient may be distressed by the prospect of losing their autonomy or ability to attempt suicide if hospitalized, and they may employ a false excuse as a substitute for the actual reason underlying their distress. A clinician may be falsely reassured if they do not accurately perceive the true cause of the emotional distress. Upon deeper exploration, the expressed emotional attachment is often found to be superficial and has little substantive support.

Continue to: Dedication to addressing acheivable goals in the near future...

Dedication to addressing achievable goals in the near future

CASE 3

Ms. C, age 15, survived a suicide attempt via a medication overdose. She says that she regrets what she did and is not planning to attempt suicide again. Ms. C says she no longer wants to die because in the future she wants to help people by becoming a nurse. She adds that there is a lot waiting for her because she wants to travel all over the world.

Ms. D, age 15, also survived a suicide attempt via a medication overdose. She also says that she regrets what she did and is not planning to attempt suicide again. Ms. D asks whether the physician would be willing to contact the school on her behalf to explain why she had to miss class and to ask for accommodations at school to assist with her panic attacks.

Future planning that involves a patient generating new plans to address current circumstances or the near future may be more reliable than future planning in which a patient repeats their previously constructed plans for the distant future. Eliciting more distant plans, such as a career or family-oriented decisions, indicates the ability to access these “memorized” plans rather than the ability to generate future plans.

Plans that address the distant future, such as those expressed by Ms. C, may have stronger neurologic imprints as a result of repeated memorization and modifications over the years, which may allow a patient to access these plans even while under the stress associated with suicidal thinking. On the other hand, plans that address the near future, such as those expressed by Ms. D, are likely generated in response to current circumstances, which indicates the presence of adequate mental capacity to attend to the current situation, and hence, less preoccupation with suicidal thinking. There might be a neurologic basis for this: some evidence suggests that executive frontoparietal control is recruited in achievable, near-future planning, whereas abstract, difficult-to-achieve, more distant planning fails to engage these additional brain regions.23,24

Spontaneity and smooth expression

CASE 4

Mr. E, age 48, reassures his psychiatrist that he has no intent to act on his suicidal thoughts. When he is offered treatment options, he explains that he would like to start pharmacologic treatment because he only has a few weeks left before he relocates for a new job. The clinician discusses starting a specific medication, and Mr. E expresses interest unless the medication will interfere with his future position as a machine operator. Later, he declines social work assistance to establish care in his new location, preferring to first get the new health care insurance.

A smooth and noncalculated flow of future plans in a patient’s speech allows their plans to be more believable. Plans that naturally flow in response to a verbal exchange and without direct inquiry from the clinician are less likely to be confabulated. This leaves clinicians with the burden of improving the skill of subtly eliciting a patient’s future plans while avoiding directly asking about them. Directly inquiring about such plans may easily tip off the patient that their future planning is under investigation, which may result in misleading responses.

Although future plans that are expressed abruptly, without introductory verbal exchange, or are explicitly linked to why the patient doesn’t intend to kill themselves, can be genuine, the clinician may need to be skeptical about their significance during the risk evaluation. While facing such challenges, clinicians could attempt to shift the patient’s attention away from a safety and disposition-focused conversation toward a less goal-directed verbal exchange during which other opportunities for smooth expression of future plans may emerge. For example, if a patient suddenly discusses how much they care about X in attempt to emphasize why they are not contemplating suicide, the clinician may respond by gently asking the patient to talk more about X.

Continue to: Adopt a more nuanced approach...

Adopt a more nuanced approach

Assessment of the imminent risk of suicide is complicated and not well researched. A patient’s future planning can be used to better inform the evaluation. A patient may have a limited ability to generate future plans while contemplating suicide. Future plans that are specific, rich in details, achievable, dedicated to addressing the near future, and expressed smoothly and in a noncalculated fashion may be more reliable than other types of plans. The process of future planning may indicate low imminent suicide risk when it leads the patient to generate new plans to address current circumstances or the near future. When evaluating a patient’s imminent suicide risk, clinicians should consider abandoning a binary “is there future planning or not” approach and adopting a more complex, nuanced understanding to appropriately utilize this important factor in the risk assessment.

Bottom Line

A patient’s ability to plan for the future should be explored during an assessment of imminent suicide risk. Future plans that are specific, rich in details, achievable, dedicated to addressing the near future, and expressed smoothly and in a noncalculated fashion may be more reliable than other types of plans.

1. Gilbert AM, Garno JL, Braga RJ, et al. Clinical and cognitive correlates of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder: is suicide predictable? J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1027-1033.

2. Obegi JH. Your patient refuses a suicide risk assessment. Now what? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):45.

3. Blanchard M, Farber BA. “It is never okay to talk about suicide”: Patients’ reasons for concealing suicidal ideation in psychotherapy. Psychother Res. 2020;30(1):124-136.

4. Richards JE, Whiteside U, Ludman EJ, et al. Understanding why patients may not report suicidal ideation at a health care visit prior to a suicide attempt: a qualitative study. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(1):40-45.

5. Fulginiti A, Frey LM. Exploring suicide-related disclosure motivation and the impact on mechanisms linked to suicide. Death Stud. 2019;43(9):562-569.

6. Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Marshall KL, et al. Adolescents’ suicidal thinking and reluctance to consult general medical practitioners. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(4):343-356.

7. Eagles D, Stiell IG, Clement CM, et al. International survey of emergency physicians’ priorities for clinical decision rules. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(2):177-182.

8. Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment (SBU): SBU Systematic Review Summaries. Instruments for Suicide Risk Assessment. Summary and Conclusions. SBU Yellow Report No. 242. 2015. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK350492/

9. Runeson B, Odeberg J, Pettersson A, et al. Instruments for the assessment of suicide risk: a systematic review evaluating the certainty of the evidence. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180292. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180292

10. Steeg S, Quinlivan L, Nowland R, et al. Accuracy of risk scales for predicting repeat self-harm and suicide: a multicentre, population-level cohort study using routine clinical data. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):113.

11. Nock MK, Banaji MR. Prediction of suicide ideation and attempts among adolescents using a brief performance-based test. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(5):707-715.

12. Draper J, Murphy G, Vega E, et al. Helping callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline who are at imminent risk of suicide: the importance of active engagement, active rescue, and collaboration between crisis and emergency services. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015;45(3):261-270.

13. Glenn CR, Nock MK. Improving the short-term prediction of suicidal behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3 Suppl 2):S176-S180.

14. MacLeod AK, Pankhania B, Lee M, et al. Parasuicide, depression and the anticipation of positive and negative future experiences. Psychol Med. 1997;27(4):973-977.

15. MacLeod AK, Tata P, Evans K, et al. Recovery of positive future thinking within a high-risk parasuicide group: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Br J Clin Psychol. 1998;37(4):371-379.

16. MacLeod AK, Tata P, Tyrer P, et al. Hopelessness and positive and negative future thinking in parasuicide. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44(Pt 4):495-504.

17. O’Connor RC, Smyth R, Williams JM. Intrapersonal positive future thinking predicts repeat suicide attempts in hospital-treated suicide attempters. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(1):169-176.

18. O’Connor RC, Williams JMG. The relationship between positive future thinking, brooding, defeat and entrapment. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;70:29-34.

19. Castaneda AE, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Marttunen M, et al. A review on cognitive impairments in depressive and anxiety disorders with a focus on young adults. J Affect Disord. 2008;106(1-2):1-27.

20. Austin MP, Mitchell P, Goodwin GM. Cognitive deficits in depression: possible implications for functional neuropathology. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:200-206.

21. Buoli M, Caldiroli A, Caletti E, et al. The impact of mood episodes and duration of illness on cognition in bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(7):1561-1566.

22. Marzuk PM, Hartwell N, Leon AC, et al. Executive functioning in depressed patients with suicidal ideation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(4):294-301.

23. Spreng RN, Gerlach KD, Turner GR, et al. Autobiographical planning and the brain: activation and its modulation by qualitative features. J Cogn Neurosci. 2015;27(11):2147-2157.

24. Spreng RN, Sepulcre J, Turner GR, et al. Intrinsic architecture underlying the relations among the default, dorsal attention, and frontoparietal control networks of the human brain. J Cogn Neurosci. 2013;25(1):74-86.

A patient who has the ability to plan for their future can be reassuring for a clinician who is conducting an imminent suicide risk evaluation. However, that patient may report future plans even as they are contemplating suicide. Therefore, this variable should not be simplified categorically to the mere presence or absence of future plans. Such plans, and the process by which they are produced, should be examined more closely. In this article, we explore the relationship between a patient’s intent to die by suicide in the near future and their ability to maintain future planning. We also use case examples to highlight certain characteristics that may allow future planning to be integrated more reliably into the assessment of imminent risk of suicide.

An inherent challenge

Suicide risk assessment can be challenging due to the numerous factors that can contribute to a patient’s suicidal intent.1 Some individuals don’t seek help when they develop suicidal thoughts, and even among those who do, recognizing who may be at greater risk is not an easy task. Sometimes, this leads to inadequate interventions and a subsequent failure to ensure safety, or to an overreaction and unnecessary hospitalization.

A common difficulty is a patient’s unwillingness to cooperate with the examination.2 Some patients do not present voluntarily, while others may seek help but then conceal suicidal intent. In a sample of 66 psychotherapy patients who reported concealing suicidal ideation from their therapist and provided short essay responses explaining their motives for doing so, approximately 70% said fear of involuntary hospitalization was their motive to hide those thoughts from their doctor.3 Other reasons for concealment are shame, stigma, embarrassment, fear of rejection, and loss of autonomy.3-5 Moreover, higher levels of suicidal ideation are associated with treatment avoidance.6 Therefore, it is important to improve suicide predictability independent of the patient report. In a survey of 1,150 emergency physicians in Australasia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, the need for evidence-based guidelines on when to hospitalize a patient at risk for suicide was ranked as the 7th-highest priority.7 There are limitations to using suicide risk assessment scales,8,9 because scales designed to have high sensitivity are less specific, and those with high specificity fail to identify individuals at high risk.9,10 Most of the research conducted in this area has focused on the risk of suicide in 2 to 6 months, and not on imminent risk.11

What is ‘imminent’ risk?

There is no specific time definition for “imminent risk,” but the Lifeline Standards, Trainings, and Practices Subcommittee, a group of national and international experts in suicide prevention, defines imminent risk of suicide as the belief that there is a “close temporal connection between the person’s current risk status and actions that could lead to his/her suicide.”12 Practically, suicide could be considered imminent when it occurs within a few days of the evaluation. However, suicide may take place within a few days of an evaluation due to new life events or impulsive actions, which may explain why imminent risk of suicide can be difficult to define and predict. In clinical practice, there is little evidence-based knowledge about estimating imminent risk. Recent studies have explored certain aspects of a patient’s history in the attempt to improve imminent risk predictability.13 In light of the complexity of this matter and the lack of widely validated tools, clinicians are encouraged to share their experience with other clinicians while the efforts to advance evidence-based knowledge and tools continue.

The function of future planning

Future planning is a mental process embedded in several crucial executive functions. It operates on a daily basis to organize, prioritize, and carry out tasks to achieve day-to-day and more distant future goals. Some research has found that a decreased ability to generate positive future thoughts is linked to increased suicide risk in the long term.14-17 Positive future planning can be affected by even minor fluctuations in mood because the additional processing capacity needed during these mood changes may limit one’s ability to generate positive future thoughts.18 Patients experiencing mood episodes are known to experience cognitive dysfunctions.19-21 However, additional measurable cognitive changes have been detected in patients who are suicidal. For example, in a small study (N = 33) of patients with depression, those who were experiencing suicidal thoughts underperformed on several measures of executive functioning compared to patients with no suicidal ideation.22

However, when addressing imminent rather than future suicide risk, even neutral future plans—such as day-to-day plans or those addressing barriers to treatment—can be a meaningful indicator of the investment in one’s future beyond a potential near-term suicide, and therefore can be explored to further inform the risk evaluation. Significant mental resources can be consumed due to the level of distress associated with contemplating suicide, and therefore patients may have a reduced capacity for day-to-day planning. Thus, serious suicide contemplation is less likely in the presence of typical future planning.

Continue to: Characteristics of future planning...

Characteristics of future planning

Some patients may pretend to engage in future planning to indicate the absence of suicidal intent. This necessitates a more nuanced assessment of future plans beyond whether they exist or not by examining the genuineness of such plans, and the authenticity of the process by which they are produced. The Table lists 3 characteristics of future plans/future planning that, based on our clinical experience, can be helpful to evaluate during an imminent suicide risk evaluation. These are described in the following case examples.

Specificity and richness of details

CASE 1

Mr. A, a college student, presents to the emergency department (ED) complaining of depression and suicidal thoughts that he is able to dismiss. He would like to avoid starting a medication because he has finals in 2 weeks and is worried about adverse effects. He learned about cognitive-behavioral therapy and is interested in getting a referral to a specific office because it is located within a walking distance from campus and easy for him to access because he does not own a car.

The volume of details expressed in a patient’s future plans is important. The more detailed these plans are, the more likely the patient is invested in them. Attendance to the details, especially when addressing expected barriers to treatment, such as transportation, can be evidence of genuine future planning and subsequently of low imminent suicide risk. Spreng et al23 found that autobiographic plans that are more specific and richer in detail recruit additional brain regions that are not recruited in plans that are sparsely detailed or constructed from more generalized representations.

CASE 2

An ambulance transports Ms. B, age 42, from a primary care clinic to the ED because she has been having suicidal thoughts, with a plan to hang herself, for the past 2 days. During the evaluation, Ms. B denies having further suicidal thoughts and declines inpatient admission. She claims that she cannot be away from her children because she is their primary caretaker. Collateral information reveals that Ms. B’s mother has been caring for her children for the last 2 weeks because Ms. B has been too depressed to do so. She continues to refuse admission and is in tears while trying to explain how her absence due to inpatient treatment will be detrimental to her children. Eventually, she angrily accuses the clinician of abusing her children by forcing her to be hospitalized.

In an effort to conceal suicidal intent, patients may present obligations or excuses that would be an obstacle to psychiatric hospitalization. This might give a false perception of intact future planning. However, in these cases, patients often fail to volunteer details about their future plans or show evidence for actual attendance to their obligations. Due to the lack of tangible details to explain the negative effects of inpatient treatment, patients may compensate by using an exaggerated emotional response, with a strong emotional attachment to the obligation and severe distress over their potential inability to fulfill it due to a psychiatric hospitalization. This may contribute to concealing suicidal intent in a different way. A patient may be distressed by the prospect of losing their autonomy or ability to attempt suicide if hospitalized, and they may employ a false excuse as a substitute for the actual reason underlying their distress. A clinician may be falsely reassured if they do not accurately perceive the true cause of the emotional distress. Upon deeper exploration, the expressed emotional attachment is often found to be superficial and has little substantive support.

Continue to: Dedication to addressing acheivable goals in the near future...

Dedication to addressing achievable goals in the near future

CASE 3

Ms. C, age 15, survived a suicide attempt via a medication overdose. She says that she regrets what she did and is not planning to attempt suicide again. Ms. C says she no longer wants to die because in the future she wants to help people by becoming a nurse. She adds that there is a lot waiting for her because she wants to travel all over the world.

Ms. D, age 15, also survived a suicide attempt via a medication overdose. She also says that she regrets what she did and is not planning to attempt suicide again. Ms. D asks whether the physician would be willing to contact the school on her behalf to explain why she had to miss class and to ask for accommodations at school to assist with her panic attacks.

Future planning that involves a patient generating new plans to address current circumstances or the near future may be more reliable than future planning in which a patient repeats their previously constructed plans for the distant future. Eliciting more distant plans, such as a career or family-oriented decisions, indicates the ability to access these “memorized” plans rather than the ability to generate future plans.

Plans that address the distant future, such as those expressed by Ms. C, may have stronger neurologic imprints as a result of repeated memorization and modifications over the years, which may allow a patient to access these plans even while under the stress associated with suicidal thinking. On the other hand, plans that address the near future, such as those expressed by Ms. D, are likely generated in response to current circumstances, which indicates the presence of adequate mental capacity to attend to the current situation, and hence, less preoccupation with suicidal thinking. There might be a neurologic basis for this: some evidence suggests that executive frontoparietal control is recruited in achievable, near-future planning, whereas abstract, difficult-to-achieve, more distant planning fails to engage these additional brain regions.23,24

Spontaneity and smooth expression

CASE 4

Mr. E, age 48, reassures his psychiatrist that he has no intent to act on his suicidal thoughts. When he is offered treatment options, he explains that he would like to start pharmacologic treatment because he only has a few weeks left before he relocates for a new job. The clinician discusses starting a specific medication, and Mr. E expresses interest unless the medication will interfere with his future position as a machine operator. Later, he declines social work assistance to establish care in his new location, preferring to first get the new health care insurance.

A smooth and noncalculated flow of future plans in a patient’s speech allows their plans to be more believable. Plans that naturally flow in response to a verbal exchange and without direct inquiry from the clinician are less likely to be confabulated. This leaves clinicians with the burden of improving the skill of subtly eliciting a patient’s future plans while avoiding directly asking about them. Directly inquiring about such plans may easily tip off the patient that their future planning is under investigation, which may result in misleading responses.

Although future plans that are expressed abruptly, without introductory verbal exchange, or are explicitly linked to why the patient doesn’t intend to kill themselves, can be genuine, the clinician may need to be skeptical about their significance during the risk evaluation. While facing such challenges, clinicians could attempt to shift the patient’s attention away from a safety and disposition-focused conversation toward a less goal-directed verbal exchange during which other opportunities for smooth expression of future plans may emerge. For example, if a patient suddenly discusses how much they care about X in attempt to emphasize why they are not contemplating suicide, the clinician may respond by gently asking the patient to talk more about X.

Continue to: Adopt a more nuanced approach...

Adopt a more nuanced approach

Assessment of the imminent risk of suicide is complicated and not well researched. A patient’s future planning can be used to better inform the evaluation. A patient may have a limited ability to generate future plans while contemplating suicide. Future plans that are specific, rich in details, achievable, dedicated to addressing the near future, and expressed smoothly and in a noncalculated fashion may be more reliable than other types of plans. The process of future planning may indicate low imminent suicide risk when it leads the patient to generate new plans to address current circumstances or the near future. When evaluating a patient’s imminent suicide risk, clinicians should consider abandoning a binary “is there future planning or not” approach and adopting a more complex, nuanced understanding to appropriately utilize this important factor in the risk assessment.

Bottom Line

A patient’s ability to plan for the future should be explored during an assessment of imminent suicide risk. Future plans that are specific, rich in details, achievable, dedicated to addressing the near future, and expressed smoothly and in a noncalculated fashion may be more reliable than other types of plans.

A patient who has the ability to plan for their future can be reassuring for a clinician who is conducting an imminent suicide risk evaluation. However, that patient may report future plans even as they are contemplating suicide. Therefore, this variable should not be simplified categorically to the mere presence or absence of future plans. Such plans, and the process by which they are produced, should be examined more closely. In this article, we explore the relationship between a patient’s intent to die by suicide in the near future and their ability to maintain future planning. We also use case examples to highlight certain characteristics that may allow future planning to be integrated more reliably into the assessment of imminent risk of suicide.

An inherent challenge

Suicide risk assessment can be challenging due to the numerous factors that can contribute to a patient’s suicidal intent.1 Some individuals don’t seek help when they develop suicidal thoughts, and even among those who do, recognizing who may be at greater risk is not an easy task. Sometimes, this leads to inadequate interventions and a subsequent failure to ensure safety, or to an overreaction and unnecessary hospitalization.

A common difficulty is a patient’s unwillingness to cooperate with the examination.2 Some patients do not present voluntarily, while others may seek help but then conceal suicidal intent. In a sample of 66 psychotherapy patients who reported concealing suicidal ideation from their therapist and provided short essay responses explaining their motives for doing so, approximately 70% said fear of involuntary hospitalization was their motive to hide those thoughts from their doctor.3 Other reasons for concealment are shame, stigma, embarrassment, fear of rejection, and loss of autonomy.3-5 Moreover, higher levels of suicidal ideation are associated with treatment avoidance.6 Therefore, it is important to improve suicide predictability independent of the patient report. In a survey of 1,150 emergency physicians in Australasia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, the need for evidence-based guidelines on when to hospitalize a patient at risk for suicide was ranked as the 7th-highest priority.7 There are limitations to using suicide risk assessment scales,8,9 because scales designed to have high sensitivity are less specific, and those with high specificity fail to identify individuals at high risk.9,10 Most of the research conducted in this area has focused on the risk of suicide in 2 to 6 months, and not on imminent risk.11

What is ‘imminent’ risk?

There is no specific time definition for “imminent risk,” but the Lifeline Standards, Trainings, and Practices Subcommittee, a group of national and international experts in suicide prevention, defines imminent risk of suicide as the belief that there is a “close temporal connection between the person’s current risk status and actions that could lead to his/her suicide.”12 Practically, suicide could be considered imminent when it occurs within a few days of the evaluation. However, suicide may take place within a few days of an evaluation due to new life events or impulsive actions, which may explain why imminent risk of suicide can be difficult to define and predict. In clinical practice, there is little evidence-based knowledge about estimating imminent risk. Recent studies have explored certain aspects of a patient’s history in the attempt to improve imminent risk predictability.13 In light of the complexity of this matter and the lack of widely validated tools, clinicians are encouraged to share their experience with other clinicians while the efforts to advance evidence-based knowledge and tools continue.

The function of future planning

Future planning is a mental process embedded in several crucial executive functions. It operates on a daily basis to organize, prioritize, and carry out tasks to achieve day-to-day and more distant future goals. Some research has found that a decreased ability to generate positive future thoughts is linked to increased suicide risk in the long term.14-17 Positive future planning can be affected by even minor fluctuations in mood because the additional processing capacity needed during these mood changes may limit one’s ability to generate positive future thoughts.18 Patients experiencing mood episodes are known to experience cognitive dysfunctions.19-21 However, additional measurable cognitive changes have been detected in patients who are suicidal. For example, in a small study (N = 33) of patients with depression, those who were experiencing suicidal thoughts underperformed on several measures of executive functioning compared to patients with no suicidal ideation.22

However, when addressing imminent rather than future suicide risk, even neutral future plans—such as day-to-day plans or those addressing barriers to treatment—can be a meaningful indicator of the investment in one’s future beyond a potential near-term suicide, and therefore can be explored to further inform the risk evaluation. Significant mental resources can be consumed due to the level of distress associated with contemplating suicide, and therefore patients may have a reduced capacity for day-to-day planning. Thus, serious suicide contemplation is less likely in the presence of typical future planning.

Continue to: Characteristics of future planning...

Characteristics of future planning

Some patients may pretend to engage in future planning to indicate the absence of suicidal intent. This necessitates a more nuanced assessment of future plans beyond whether they exist or not by examining the genuineness of such plans, and the authenticity of the process by which they are produced. The Table lists 3 characteristics of future plans/future planning that, based on our clinical experience, can be helpful to evaluate during an imminent suicide risk evaluation. These are described in the following case examples.

Specificity and richness of details

CASE 1

Mr. A, a college student, presents to the emergency department (ED) complaining of depression and suicidal thoughts that he is able to dismiss. He would like to avoid starting a medication because he has finals in 2 weeks and is worried about adverse effects. He learned about cognitive-behavioral therapy and is interested in getting a referral to a specific office because it is located within a walking distance from campus and easy for him to access because he does not own a car.

The volume of details expressed in a patient’s future plans is important. The more detailed these plans are, the more likely the patient is invested in them. Attendance to the details, especially when addressing expected barriers to treatment, such as transportation, can be evidence of genuine future planning and subsequently of low imminent suicide risk. Spreng et al23 found that autobiographic plans that are more specific and richer in detail recruit additional brain regions that are not recruited in plans that are sparsely detailed or constructed from more generalized representations.

CASE 2

An ambulance transports Ms. B, age 42, from a primary care clinic to the ED because she has been having suicidal thoughts, with a plan to hang herself, for the past 2 days. During the evaluation, Ms. B denies having further suicidal thoughts and declines inpatient admission. She claims that she cannot be away from her children because she is their primary caretaker. Collateral information reveals that Ms. B’s mother has been caring for her children for the last 2 weeks because Ms. B has been too depressed to do so. She continues to refuse admission and is in tears while trying to explain how her absence due to inpatient treatment will be detrimental to her children. Eventually, she angrily accuses the clinician of abusing her children by forcing her to be hospitalized.

In an effort to conceal suicidal intent, patients may present obligations or excuses that would be an obstacle to psychiatric hospitalization. This might give a false perception of intact future planning. However, in these cases, patients often fail to volunteer details about their future plans or show evidence for actual attendance to their obligations. Due to the lack of tangible details to explain the negative effects of inpatient treatment, patients may compensate by using an exaggerated emotional response, with a strong emotional attachment to the obligation and severe distress over their potential inability to fulfill it due to a psychiatric hospitalization. This may contribute to concealing suicidal intent in a different way. A patient may be distressed by the prospect of losing their autonomy or ability to attempt suicide if hospitalized, and they may employ a false excuse as a substitute for the actual reason underlying their distress. A clinician may be falsely reassured if they do not accurately perceive the true cause of the emotional distress. Upon deeper exploration, the expressed emotional attachment is often found to be superficial and has little substantive support.

Continue to: Dedication to addressing acheivable goals in the near future...

Dedication to addressing achievable goals in the near future

CASE 3

Ms. C, age 15, survived a suicide attempt via a medication overdose. She says that she regrets what she did and is not planning to attempt suicide again. Ms. C says she no longer wants to die because in the future she wants to help people by becoming a nurse. She adds that there is a lot waiting for her because she wants to travel all over the world.

Ms. D, age 15, also survived a suicide attempt via a medication overdose. She also says that she regrets what she did and is not planning to attempt suicide again. Ms. D asks whether the physician would be willing to contact the school on her behalf to explain why she had to miss class and to ask for accommodations at school to assist with her panic attacks.

Future planning that involves a patient generating new plans to address current circumstances or the near future may be more reliable than future planning in which a patient repeats their previously constructed plans for the distant future. Eliciting more distant plans, such as a career or family-oriented decisions, indicates the ability to access these “memorized” plans rather than the ability to generate future plans.

Plans that address the distant future, such as those expressed by Ms. C, may have stronger neurologic imprints as a result of repeated memorization and modifications over the years, which may allow a patient to access these plans even while under the stress associated with suicidal thinking. On the other hand, plans that address the near future, such as those expressed by Ms. D, are likely generated in response to current circumstances, which indicates the presence of adequate mental capacity to attend to the current situation, and hence, less preoccupation with suicidal thinking. There might be a neurologic basis for this: some evidence suggests that executive frontoparietal control is recruited in achievable, near-future planning, whereas abstract, difficult-to-achieve, more distant planning fails to engage these additional brain regions.23,24

Spontaneity and smooth expression

CASE 4

Mr. E, age 48, reassures his psychiatrist that he has no intent to act on his suicidal thoughts. When he is offered treatment options, he explains that he would like to start pharmacologic treatment because he only has a few weeks left before he relocates for a new job. The clinician discusses starting a specific medication, and Mr. E expresses interest unless the medication will interfere with his future position as a machine operator. Later, he declines social work assistance to establish care in his new location, preferring to first get the new health care insurance.

A smooth and noncalculated flow of future plans in a patient’s speech allows their plans to be more believable. Plans that naturally flow in response to a verbal exchange and without direct inquiry from the clinician are less likely to be confabulated. This leaves clinicians with the burden of improving the skill of subtly eliciting a patient’s future plans while avoiding directly asking about them. Directly inquiring about such plans may easily tip off the patient that their future planning is under investigation, which may result in misleading responses.

Although future plans that are expressed abruptly, without introductory verbal exchange, or are explicitly linked to why the patient doesn’t intend to kill themselves, can be genuine, the clinician may need to be skeptical about their significance during the risk evaluation. While facing such challenges, clinicians could attempt to shift the patient’s attention away from a safety and disposition-focused conversation toward a less goal-directed verbal exchange during which other opportunities for smooth expression of future plans may emerge. For example, if a patient suddenly discusses how much they care about X in attempt to emphasize why they are not contemplating suicide, the clinician may respond by gently asking the patient to talk more about X.

Continue to: Adopt a more nuanced approach...

Adopt a more nuanced approach

Assessment of the imminent risk of suicide is complicated and not well researched. A patient’s future planning can be used to better inform the evaluation. A patient may have a limited ability to generate future plans while contemplating suicide. Future plans that are specific, rich in details, achievable, dedicated to addressing the near future, and expressed smoothly and in a noncalculated fashion may be more reliable than other types of plans. The process of future planning may indicate low imminent suicide risk when it leads the patient to generate new plans to address current circumstances or the near future. When evaluating a patient’s imminent suicide risk, clinicians should consider abandoning a binary “is there future planning or not” approach and adopting a more complex, nuanced understanding to appropriately utilize this important factor in the risk assessment.

Bottom Line

A patient’s ability to plan for the future should be explored during an assessment of imminent suicide risk. Future plans that are specific, rich in details, achievable, dedicated to addressing the near future, and expressed smoothly and in a noncalculated fashion may be more reliable than other types of plans.

1. Gilbert AM, Garno JL, Braga RJ, et al. Clinical and cognitive correlates of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder: is suicide predictable? J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1027-1033.

2. Obegi JH. Your patient refuses a suicide risk assessment. Now what? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):45.

3. Blanchard M, Farber BA. “It is never okay to talk about suicide”: Patients’ reasons for concealing suicidal ideation in psychotherapy. Psychother Res. 2020;30(1):124-136.

4. Richards JE, Whiteside U, Ludman EJ, et al. Understanding why patients may not report suicidal ideation at a health care visit prior to a suicide attempt: a qualitative study. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(1):40-45.

5. Fulginiti A, Frey LM. Exploring suicide-related disclosure motivation and the impact on mechanisms linked to suicide. Death Stud. 2019;43(9):562-569.

6. Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Marshall KL, et al. Adolescents’ suicidal thinking and reluctance to consult general medical practitioners. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(4):343-356.

7. Eagles D, Stiell IG, Clement CM, et al. International survey of emergency physicians’ priorities for clinical decision rules. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(2):177-182.

8. Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment (SBU): SBU Systematic Review Summaries. Instruments for Suicide Risk Assessment. Summary and Conclusions. SBU Yellow Report No. 242. 2015. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK350492/

9. Runeson B, Odeberg J, Pettersson A, et al. Instruments for the assessment of suicide risk: a systematic review evaluating the certainty of the evidence. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180292. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180292

10. Steeg S, Quinlivan L, Nowland R, et al. Accuracy of risk scales for predicting repeat self-harm and suicide: a multicentre, population-level cohort study using routine clinical data. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):113.

11. Nock MK, Banaji MR. Prediction of suicide ideation and attempts among adolescents using a brief performance-based test. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(5):707-715.

12. Draper J, Murphy G, Vega E, et al. Helping callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline who are at imminent risk of suicide: the importance of active engagement, active rescue, and collaboration between crisis and emergency services. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015;45(3):261-270.

13. Glenn CR, Nock MK. Improving the short-term prediction of suicidal behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3 Suppl 2):S176-S180.

14. MacLeod AK, Pankhania B, Lee M, et al. Parasuicide, depression and the anticipation of positive and negative future experiences. Psychol Med. 1997;27(4):973-977.

15. MacLeod AK, Tata P, Evans K, et al. Recovery of positive future thinking within a high-risk parasuicide group: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Br J Clin Psychol. 1998;37(4):371-379.

16. MacLeod AK, Tata P, Tyrer P, et al. Hopelessness and positive and negative future thinking in parasuicide. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44(Pt 4):495-504.

17. O’Connor RC, Smyth R, Williams JM. Intrapersonal positive future thinking predicts repeat suicide attempts in hospital-treated suicide attempters. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(1):169-176.

18. O’Connor RC, Williams JMG. The relationship between positive future thinking, brooding, defeat and entrapment. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;70:29-34.

19. Castaneda AE, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Marttunen M, et al. A review on cognitive impairments in depressive and anxiety disorders with a focus on young adults. J Affect Disord. 2008;106(1-2):1-27.

20. Austin MP, Mitchell P, Goodwin GM. Cognitive deficits in depression: possible implications for functional neuropathology. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:200-206.

21. Buoli M, Caldiroli A, Caletti E, et al. The impact of mood episodes and duration of illness on cognition in bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(7):1561-1566.

22. Marzuk PM, Hartwell N, Leon AC, et al. Executive functioning in depressed patients with suicidal ideation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(4):294-301.

23. Spreng RN, Gerlach KD, Turner GR, et al. Autobiographical planning and the brain: activation and its modulation by qualitative features. J Cogn Neurosci. 2015;27(11):2147-2157.

24. Spreng RN, Sepulcre J, Turner GR, et al. Intrinsic architecture underlying the relations among the default, dorsal attention, and frontoparietal control networks of the human brain. J Cogn Neurosci. 2013;25(1):74-86.

1. Gilbert AM, Garno JL, Braga RJ, et al. Clinical and cognitive correlates of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder: is suicide predictable? J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1027-1033.

2. Obegi JH. Your patient refuses a suicide risk assessment. Now what? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):45.

3. Blanchard M, Farber BA. “It is never okay to talk about suicide”: Patients’ reasons for concealing suicidal ideation in psychotherapy. Psychother Res. 2020;30(1):124-136.

4. Richards JE, Whiteside U, Ludman EJ, et al. Understanding why patients may not report suicidal ideation at a health care visit prior to a suicide attempt: a qualitative study. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(1):40-45.

5. Fulginiti A, Frey LM. Exploring suicide-related disclosure motivation and the impact on mechanisms linked to suicide. Death Stud. 2019;43(9):562-569.

6. Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Marshall KL, et al. Adolescents’ suicidal thinking and reluctance to consult general medical practitioners. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(4):343-356.

7. Eagles D, Stiell IG, Clement CM, et al. International survey of emergency physicians’ priorities for clinical decision rules. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(2):177-182.

8. Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment (SBU): SBU Systematic Review Summaries. Instruments for Suicide Risk Assessment. Summary and Conclusions. SBU Yellow Report No. 242. 2015. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK350492/

9. Runeson B, Odeberg J, Pettersson A, et al. Instruments for the assessment of suicide risk: a systematic review evaluating the certainty of the evidence. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180292. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180292

10. Steeg S, Quinlivan L, Nowland R, et al. Accuracy of risk scales for predicting repeat self-harm and suicide: a multicentre, population-level cohort study using routine clinical data. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):113.

11. Nock MK, Banaji MR. Prediction of suicide ideation and attempts among adolescents using a brief performance-based test. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(5):707-715.

12. Draper J, Murphy G, Vega E, et al. Helping callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline who are at imminent risk of suicide: the importance of active engagement, active rescue, and collaboration between crisis and emergency services. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015;45(3):261-270.

13. Glenn CR, Nock MK. Improving the short-term prediction of suicidal behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3 Suppl 2):S176-S180.

14. MacLeod AK, Pankhania B, Lee M, et al. Parasuicide, depression and the anticipation of positive and negative future experiences. Psychol Med. 1997;27(4):973-977.

15. MacLeod AK, Tata P, Evans K, et al. Recovery of positive future thinking within a high-risk parasuicide group: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Br J Clin Psychol. 1998;37(4):371-379.

16. MacLeod AK, Tata P, Tyrer P, et al. Hopelessness and positive and negative future thinking in parasuicide. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44(Pt 4):495-504.

17. O’Connor RC, Smyth R, Williams JM. Intrapersonal positive future thinking predicts repeat suicide attempts in hospital-treated suicide attempters. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(1):169-176.

18. O’Connor RC, Williams JMG. The relationship between positive future thinking, brooding, defeat and entrapment. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;70:29-34.

19. Castaneda AE, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Marttunen M, et al. A review on cognitive impairments in depressive and anxiety disorders with a focus on young adults. J Affect Disord. 2008;106(1-2):1-27.

20. Austin MP, Mitchell P, Goodwin GM. Cognitive deficits in depression: possible implications for functional neuropathology. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:200-206.

21. Buoli M, Caldiroli A, Caletti E, et al. The impact of mood episodes and duration of illness on cognition in bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(7):1561-1566.

22. Marzuk PM, Hartwell N, Leon AC, et al. Executive functioning in depressed patients with suicidal ideation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112(4):294-301.

23. Spreng RN, Gerlach KD, Turner GR, et al. Autobiographical planning and the brain: activation and its modulation by qualitative features. J Cogn Neurosci. 2015;27(11):2147-2157.

24. Spreng RN, Sepulcre J, Turner GR, et al. Intrinsic architecture underlying the relations among the default, dorsal attention, and frontoparietal control networks of the human brain. J Cogn Neurosci. 2013;25(1):74-86.

Borderline personality disorder: 6 studies of psychosocial interventions

SECOND OF 2 PARTS

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with serious impairment in psychosocial functioning.1 It is characterized by an ongoing pattern of mood instability, cognitive distortions, problems with self-image, and impulsive behavior that often results in problems in relationships. As a result, patients with BPD tend to utilize more mental health services than patients with other personality disorders or major depressive disorder.2

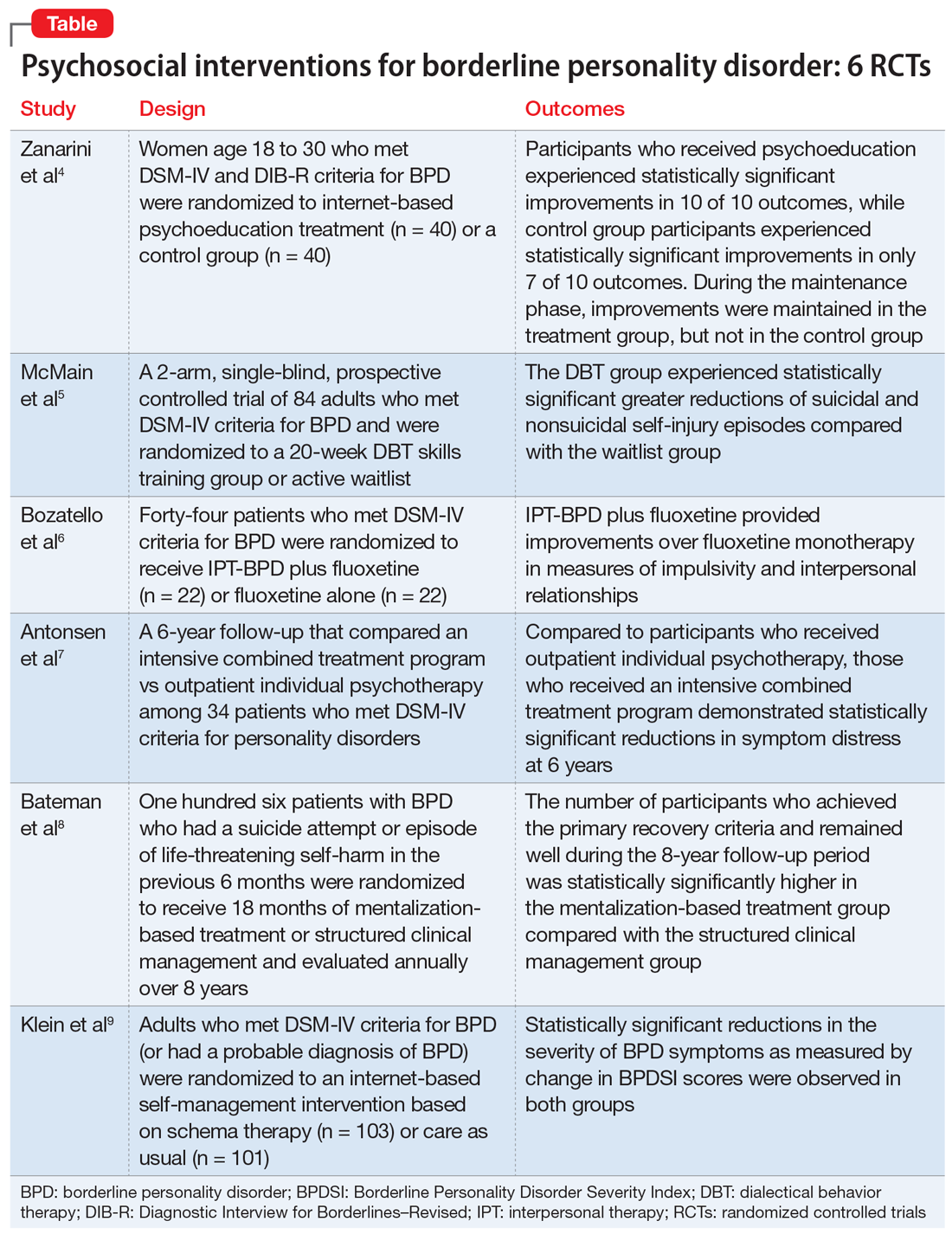

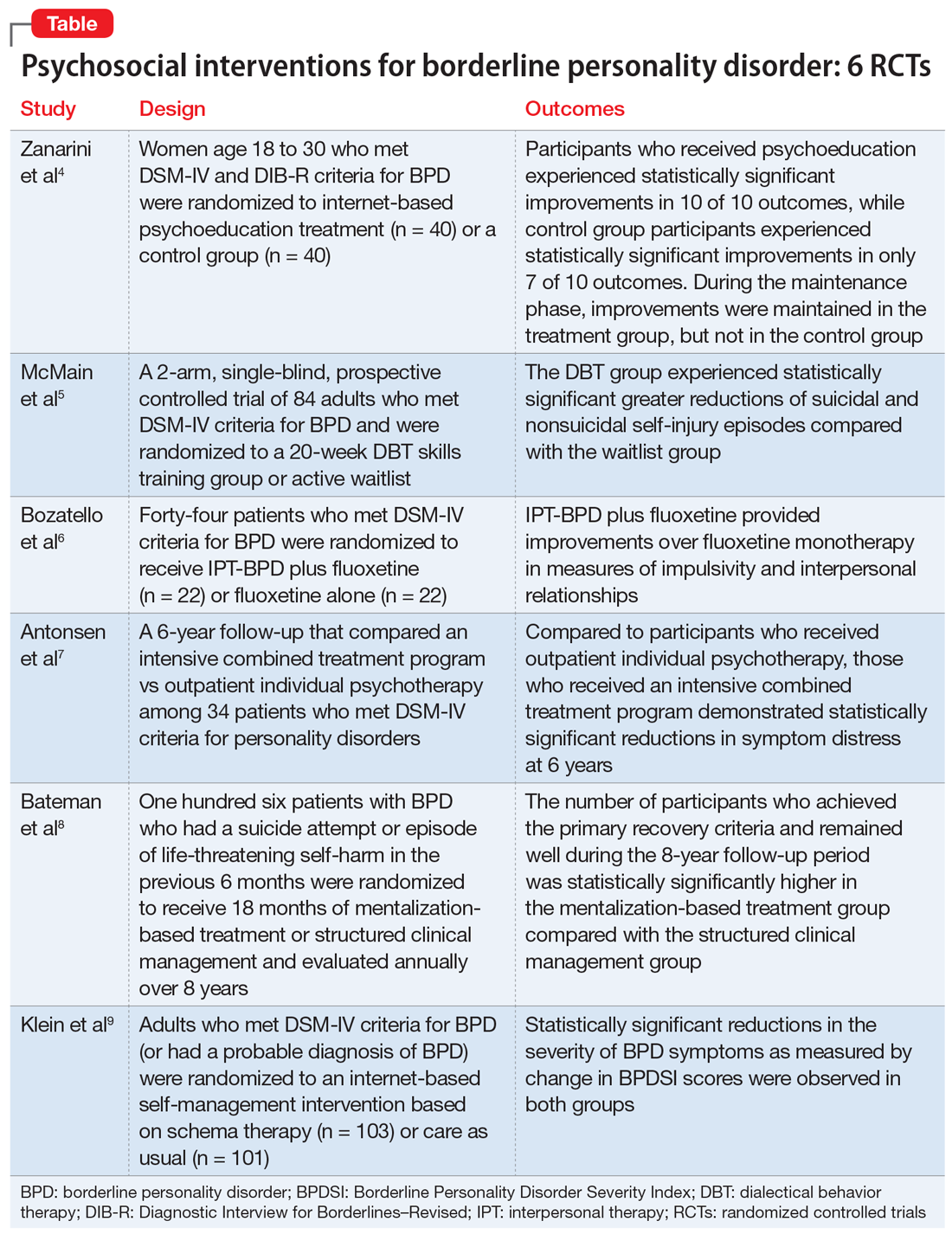

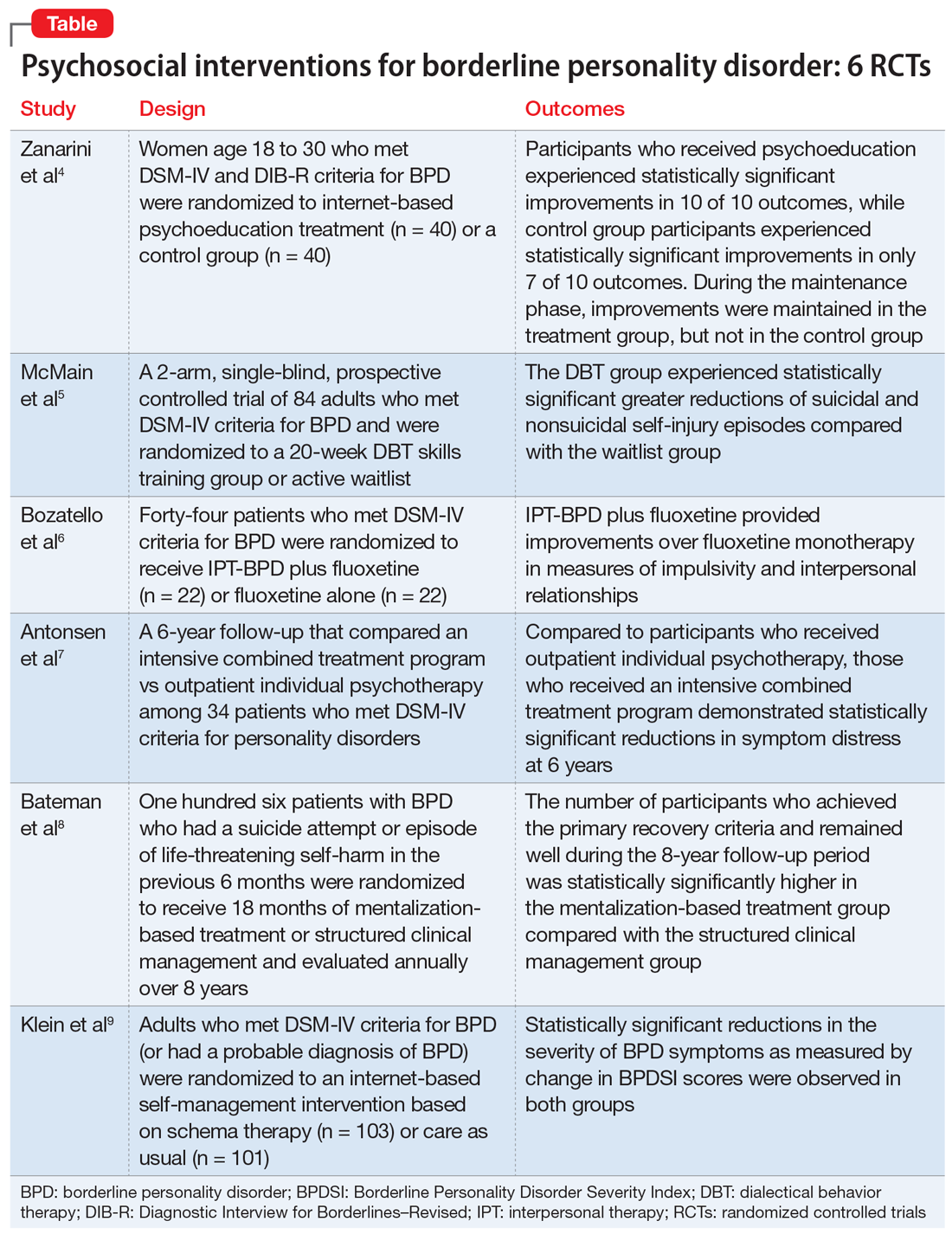

Some clinicians believe BPD is difficult to treat. While historically there has been little consensus on the best treatments for this disorder, current options include both pharmacologic and psychological interventions. In Part 1 of this 2-part article, we focused on 6 studies that evaluated biological interventions.3 Here in Part 2, we focus on findings from 6 recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychosocial interventions for BPD

1. Zanarini MC, Conkey LC, Temes CM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of web-based psychoeducation for women with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3):16m11153. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11153

Research has shown that BPD is a treatable illness with a more favorable prognosis than previously believed. Despite this, patients often experience difficulty accessing the most up-to-date information on BPD, which can impede their treatment. A 2008 study by Zanarini et al10 of younger female patients with BPD demonstrated that immediate, in-person psychoeducation improved impulsivity and relationships. Widespread implementation of this program proved problematic, however, due to cost and personnel constraints. To resolve this issue, researchers developed an internet-based version of the program. In a 2018 follow-up study, Zanarini et al4 examined the effect of this internet-based psychoeducation program on symptoms of BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- Women (age 18 to 30) who met DSM-IV and Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines–Revised criteria for BPD were randomized to an internet-based psychoeducation treatment group (n = 40) or a control group (n = 40).

- Ten outcomes concerning symptom severity and psychosocial functioning were assessed during weeks 1 to 12 (acute phase) and at months 6, 9, and 12 (maintenance phase) using the self-report version of the Zanarini Rating Scale for BPD (ZAN-BPD), the Borderline Evaluation of Severity over Time, the Sheehan Disability Scale, the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale, the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale, and Weissman’s Social Adjustment Scale (SAS).

Outcomes

- In the acute phase, treatment group participants experienced statistically significant improvements in all 10 outcomes. Control group participants demonstrated similar results, achieving statistically significant improvements in 7 of 10 outcomes.

- Compared to the control group, the treatment group experienced a more significant reduction in impulsivity and improvement in psychosocial functioning as measured by the ZAN-BPD and SAS.

- In the maintenance phase, treatment group participants achieved statistically significant improvements in 9 of 10 outcomes, whereas control group participants demonstrated statistically significant improvements in only 3 of 10 outcomes.

- Compared to the control group, the treatment group also demonstrated a significantly greater improvement in all 4 sector scores and the total score of the ZAN-BP

Conclusions/limitations

- In patients with BPD, internet-based psychoeducation reduced symptom severity and improved psychosocial functioning, with effects lasting 1 year. Treatment group participants experienced clinically significant improvements in all outcomes measured during the acute phase of the study; most improvements were maintained over 1 year.

- While the control group initially saw similar improvements in most measurements, these improvements were not maintained as effectively over 1 year.

- Limitations include a female-only population, the restricted age range of participants, and recruitment exclusively from volunteers.

2. McMain SF, Guimond T, Barnhart R, et al. A randomized trial of brief dialectical behaviour therapy skills training in suicidal patients suffering from borderline disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(2):138-148.

Standard dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an effective treatment for BPD; however, access is often limited by shortages of clinicians and resources. Therefore, it has become increasingly common for clinical settings to offer patients only the skills training component of DBT, which requires fewer resources. While several clinical trials examining brief DBT skills–only treatment for BPD have shown promising results, it is unclear how effective this intervention is at reducing suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) episodes. McMain et al5 explored the effectiveness of brief DBT skills–only adjunctive treatment on the rates of suicidal and NSSI episodes in patients with BPD.

Study design