User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Psychoses: The 5 comorbidity-defined subtypes

How can we treat psychosis if we don’t know what we are treating? Over the years, attempts at defining psychosis subtypes have met with dead ends. However, recent research supports a new approach that offers a rational classification model organized according to 5 specific comorbid anxiety and depressive disorder diagnoses.

Anxiety and depressive symptoms are not just the result of psychotic despair. They are specific diagnoses, they precede psychosis onset, they help define psychotic syndromes, and they can point to much more effective treatment approaches. Most of the psychotic diagnoses in this schema are already recognized or posited. And, just as patients who do not have psychotic illness can have more than 1 anxiety or depressive disorder, patients with psychosis can present with a mixed picture that reflects more than 1 contributing comorbidity. Research further suggests that each of the 5 psychosis comorbidity diagnoses may involve some similar underlying factors that facilitate the formation of psychosis.

This article describes the basics of 5 psychosis subtypes, and provides initial guidelines to diagnosis, symptomatology, and treatment. Though clinical experience and existing research support the clinical presence and treatment value of this classification model, further verification will require considerably more controlled studies. An eventual validation of this approach could largely supplant ill-defined diagnoses of “schizophrenia” and other functional psychoses.

Recognizing the comorbidities in the context of their corresponding psychoses entails learning new interviewing skills and devoting more time to both initial and subsequent diagnosis and treatment. In our recently published book,1 we provide extensive details on the approach we describe in this article, including case examples, new interview tools to simplify the diagnostic journey, and novel treatment approaches.

Psychosis-proneness underlies functional psychoses

Functional (idiopathic) schizophrenia and psychotic disorders have long been difficult to separate, and many categorizations have been discarded. Despite clinical dissimilarities, today we too often casually lump psychoses together as schizophrenia.2,3 Eugen Bleuler first suggested the existence of a “group of schizophrenias.”4 It is possible that his group encompasses our 5 psychoses from 5 inbuilt emotional instincts,5 each corresponding to a specific anxiety or depressive subtype.

The 5 anxiety and depressive subtypes noted in this article are common, but psychosis is not. Considerable research suggests that certain global “psychotogenic” factors create susceptibility to all psychoses.6,7 While many genetic, neuroanatomical, experiential, and other factors have been reported, the most important may be “hypofrontality” (genetically reduced frontal lobe function, size, or neuronal activity) and dopaminergic hyperfunction (genetically increased dopamine activity).5-7

An evolutionary perspective

One evolutionary theory of psychopathology starts with the subtypes of depression and anxiety. For example, major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder may encompass 5 commonplace and more specific anxiety and depressive subtypes. Consideration of the emotional, cognitive, and functional aspects of those subtypes suggests that they may have once been advantageous for primeval human herds. Those primeval altruistic instincts may have helped survival, reproduction, and preservation of kin group DNA.5

More than any other species, humans can draw upon consciousness and culture to rationally overcome the influences of unconscious instincts. But those instincts can then emerge from the deep, and painfully encourage obedience to their guidance. In nonpsychotic anxiety and depressive disorders, the specific messages are experienced as specific anxiety and depressive symptoms.5 In psychotic disorders, the messages can emerge as unreasoned and frightful fears, perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors. With newer research, clinical observation, and an evolutionary perspective, a novel and counterintuitive approach may improve our ability to help patients.8

Continue to: Five affective comorbidities evolved from primeval altruistic instincts...

Five affective comorbidities evolved from primeval altruistic instincts

Melancholic depression5

Melancholic depression is often triggered by serious illness, group exclusion, pronounced loss, or purposelessness. We hear patients talk painfully about illness, guilt, and death. Indeed, some increased risk of death, especially from infectious disease, may result from hypercortisolemia (documented by the dexamethasone suppression test). Hypercortisolemic death also occurs in salmon after spawning, and in male marsupial mice after mating. The tragic passing of an individual saves scarce resources for the remainder of the herd.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder5

Factor-analytic studies suggest 4 main obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) subtypes: cleanliness, hoarding, intrusive thoughts, and organizing. Obsessive-compulsive traits can help maintain a safe and efficient environment in humans and other species, but OCD is dysfunctional.

Panic anxiety5

Panic anxiety is triggered by real, symbolic, or emotional separation from home and family. In toddlers, separation anxiety can reduce the odds of getting lost and hurt.

Social anxiety5

Social anxiety includes fear of self-embarrassment, exposure as a pretender to higher social rank, and thus often a reluctant avoidance of increased social rank. While consciousness and cultural encouragement can overcome that hesitation and thus lead to greater success, social anxiety activation can still cause painful anxiety. The social hierarchies of many species include comparable biological influences, and help preserve group DNA by reducing hierarchical infighting.

Atypical depression and bipolar I mania5

Atypical depression includes increased rejection sensitivity, resulting in inoffensive behavior to avoid social rejection. This reduces risk of isolation from the group, and improves group harmony. Unlike the 4 other syndromes, atypical depression and bipolar I mania may reflect 2 separate seasonal mood phases. Atypical depression (including seasonal affective disorder) often worsens with shortened winter daylight hours, akin to hibernation. Initial bipolar I mania is more common with springtime daylight, with symptoms not unlike exaggerated hibernation awakening.9

Primeval biological altruism has great evolutionary value in many species, and even somewhat in modern humans. But it is quite different from modern rational altruism. Although we sometimes override our instincts, they respond with messages experienced as emotional pain—they still tell us to follow instructions for primeval herd survival. In an earlier book, I (JPK) provide a lengthier description of the evidence for this evolutionary psychopathology theory, including interplay of the 5 instincts with psychotogenic factors.5

Continue to: Five comorbidity psychoses from 5 primeval instincts.....

Five comorbidity psychoses from 5 primeval instincts

The 5 affective comorbidities described above contribute to the presence, subtype, and treatment approaches of 5 corresponding psychoses. Ordinary panic attacks might occur when feeling trapped or separated from home, so people want to flee to safety. Nonhuman species with limited consciousness and language are unlikely to think “time to head for safety.” Instead, instincts encourage flight from danger through internally generated perceptions of threat. Likewise, people with psychosis and panic, without sufficient conscious modulation, may experience sensory perceptions of actual danger when feeling symbolically trapped.1,10

One pilot study carefully examined the prevalence of these 5 comorbidities in an unselected group of psychotic patients.10 At least 85% met criteria for ≥1 of the 5 subtypes.10 Moreover, organic psychoses related to physical illness, substances, and iatrogenesis may also predict future episodes of functional psychoses.1

Using statistical analysis of psychosis rating scales, 2 studies took a “transdiagnostic” look at psychoses, and each found 5 psychosis subtypes and a generalized psychosis susceptibility factor.11,12 Replication of that transdiagnostic approach, newly including psychosis symptoms and our 5 specific comorbidities, might well find that the 5 subtype models resemble each other.11,12

Our proposed 5 comorbidity subtypes are1:

Delusional depression (melancholic depression). Most common in geriatric patients, this psychosis can also occur at younger ages. Prodromal melancholic depression can include guilt and hopelessness, and is acute, rather than the chronic course of our other 4 syndromes. Subsequent delusional depression includes delusions of bodily decay, illness, or death, as well as overwhelming guilt, shame, and remorse. The classic vegetative symptoms of depression continue. In addition to infectious disease issues, high suicide risk makes hospitalization imperative.

Obsessive-compulsive schizophrenia. Just as OCD has an early age of onset, obsessive-compulsive schizophrenia begins earlier than other psychoses. Despite preserved cognition, some nonpsychotic patients with OCD have diminished symptom insight. OCD may be comorbid with schizophrenia in 12% of cases, typically preceding psychosis onset. Obsessive-compulsive schizophrenia symptoms may include highly exaggerated doubt or ambivalence; contamination concerns; eccentric, ritualistic, motor stereotypy, checking, disorganized, and other behaviors; and paranoia.

Schizophrenia with voices (panic anxiety). Classic paranoid schizophrenia with voices appears to be the most similar to a “panic psychosis.” Patients with nonpsychotic panic anxiety have increased paranoid ideation and ideas of reference as measured on the Symptom Checklist-90. Schizophrenia is highly comorbid with panic anxiety, estimated at 45% in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study.13 These are likely underestimates: cognitive impairment hinders reporting, and psychotic panic is masked as auditory hallucinations. A pilot study of schizophrenia with voices using a carbon dioxide panic induction challenge found that 100% had panic anxiety.14 That study and another found that virtually all participants reported voices concurrent with panic using our Panic and Schizophrenia Interview (PaSI) (Box 1). Panic onset precedes schizophrenia onset, and panic may reappear if antipsychotic medications sufficiently control voices: “voices without the voices,” say some.

Box 1

Let’s talk for a minute about your voices.

[IDENTIFYING PAROXYSMAL MOMENTS OF VOICE ONSET]

Do you hear voices at every single moment, or are they sometimes silent? Think about those times when you are not actually hearing any voices.

Now, there may be reasons why the voices start talking when they do, but let’s leave that aside for now.

So, whenever the voices do begin speaking—and for whatever reason they do—is it all of a sudden, or do they start very softly and then very gradually get louder?

If your voices are nearly always there, then are there times when the voices suddenly come back, get louder, get more insistent, or just get more obvious to you?

[Focus patient on sudden moment of voice onset, intensification, or awareness]

Let’s talk about that sudden moment when the voices begin (or intensify, or become obvious), even if you know the reason why they start.

I’m going to ask you about some symptoms that you might have at that same sudden moment when the voices start (or intensify, or become obvious). If you have any of these symptoms at the other times, they do not count for now.

So, when I ask about each symptom, tell me whether it comes on at the same sudden moments as the voices, and also if it used to come on with the voices in the past.

For each sudden symptom, just say “YES” or “NO” or “SOMETIMES.”

[Begin each query with: “At the same sudden moment that the voices come on”]

- Sudden anxiety, fear, or panic on the inside?

- Sudden anger or rage on the inside? [ANGER QUERY]

- Sudden heart racing? Heart pounding?

- Sudden chest pain? Chest pressure?

- Sudden sweating?

- Sudden trembling or shaking?

- Sudden shortness of breath, or like you can’t catch your breath?

- Sudden choking or a lump in your throat?

- Sudden nausea or queasiness?

- Sudden dizziness, lightheadedness, or faintness?

- Sudden feeling of detachment, sort of like you are in a glass box?

- Sudden fear of losing control? Fear of going crazy?

- Sudden fear afraid of dying? Afraid of having a heart attack?

- Sudden numbness or tingling, especially in your hands or face?

- Sudden feeling of heat, or cold?

- Sudden itching in your teeth? [VALIDITY CHECK]

- Sudden fear that people want to hurt you? [EXCESS FEAR QUERY]

- Sudden voices? [VOICES QUERY]

[PAST & PRODROMAL PANIC HISTORY]

At what age did you first see a therapist or psychiatrist?

At what age were you first hospitalized for an emotional problem?

At what age did you first start hearing voices?

At what age did you first start having strong fears of other people?

Before you ever heard voices, did you ever have any of the other sudden symptoms like the ones we just talked about?

Did those episodes back then feel sort of like your voices or sudden fears do now, except that there were no voices or sudden fears of people back then?

At what age did those sudden anxiety (or panic or rage) episodes begin?

Back then, was there MORE (M) sudden anxiety, or the SAME (S) sudden anxiety, or LESS (L) sudden anxiety than with your sudden voices now?

[PAST & PRODROMAL PANIC SYMPTOMS]

Now let’s talk about some symptoms that you might have had at those same sudden anxiety moments, in the time before you ever heard any voices. So, for each sudden symptom just say “YES” or “NO” or “SOMETIMES.”

[Begin each query with: “At the same moment the sudden anxiety came on—but only during the time before you ever heard sudden voices”]

[Ask about the same 18 panic-related symptoms listed above]

[PHOBIA-RELATED PANIC AND VOICES]

Have you ever been afraid to go into a (car, bus, plane, train, subway, elevator, mall, tunnel, bridge, heights, small place, CAT scan or MRI, being alone, crowds)?

[If yes or maybe: Ask about panic symptoms in phobic situations]

Now let’s talk about some symptoms that you might have had at some of those times you were afraid. So, for each symptom just say “YES” or “NO” or “MAYBE.”

[Ask about the same 18 panic-related symptoms listed above]

At what age did you last have sudden anxiety without voices?

Has medication ever completely stopped your voices? Somewhat?

If so, did those other sudden symptoms still happen sometimes?

Thank you for your help, and for answering all of these questions!

Persecutory delusional disorder (social anxiety). Some “schizophrenia” without voices may be misdiagnosis of persecutory (paranoid) delusional disorder (PDD). Therefore, the reported population prevalence (0.02%) may be underestimated. Social anxiety is highly comorbid with “schizophrenia” (15%).16 Case reports and clinical experience suggest that PDD is commonly preceded by social anxiety.17 Some nonpsychotic social anxiety symptoms closely resemble the PDD psychotic ideas of reference (a perception that low social rank attracts critical scrutiny by authorities). Patients with PDD may remain relatively functional, with few negative symptoms, despite pronounced paranoia. Outward manifestation of paranoia may be limited, unless quite intense. The typical age of onset (40 years) is later than that of schizophrenia, and symptoms can last a long time.18

Continue to: Bipolar 1 mania with delusions...

Bipolar I mania with delusions (atypical depression). Atypical depression is the most common depression in bipolar I disorder. Often more pronounced in winter, it may intensify at any time of year. Long ago, hypersomnia, lethargy, inactivity, inoffensiveness, and craving high-calorie food may have been conducive to hibernation.

Bipolar I mania includes delusions of special accomplishments or abilities, energetically focused on a grandiose mission to help everyone. These intense symptoms may be related to reduced frontal lobe modulation. In some milder form, bipolar I mania may once have encouraged hibernation awakening. Indeed, initial bipolar I mania episodes are more common in spring, as is the spring cleaning that helps us prepare for summer.

Recognizing affective trees in a psychotic forest

Though long observed, comorbid affective symptoms have generally been considered a hodgepodge of distress caused by painful psychotic illness. But the affective symptoms precede psychosis onset, can be masked during acute psychosis, and will revert to ordinary form if psychosis abates.11-13

Rather than affective symptoms being a consequence of psychosis, it may well be the other way around. Affective disorders could be important causal and differentiating components of psychotic disorders.11-13 Research and clinical experience suggest that adjunctive treatment of the comorbidities with correct medication can greatly enhance outcome.

Diagnostic approaches

Because interviews of patients with psychosis are often complicated by confusion, irritability, paranoid evasiveness, cognitive impairment, and medication, nuanced diagnosis is difficult. Interviews should explore psychotic syndromes and subtypes that correlate with comorbidity psychoses, including pre-psychotic anxiety and depressive diagnoses that are chronic (though unlike our 4 other diagnoses, melancholic depression is not chronic).

Establishing pre-psychotic diagnosis of chronic syndromes suggests that they are still present, even if they are difficult to assess during psychosis. Re-interview after some improvement allows for a significantly better diagnosis. Just as in nonpsychotic affective disorders, multiple comorbidities are common, and can lead to a mixed psychotic diagnosis and treatment plan.1

Structured interview tools can assist diagnosis. The PaSI (Box 1,15) elicits past, present, and detailed history of DSM panic, and has been validated in a small pilot randomized controlled trial. The PaSI focuses patient attention on paroxysmal onset voices, and then evaluates the presence of concurrent DSM panic symptoms. If voices are mostly psychotic panic, they may well be a proxy for panic. Ultimately, diagnosis of 5 comorbidities and associated psychotic symptoms may allow simpler categorization into 1 (or more) of the 5 psychosis subtypes.

Continue to: Treatment by comorbidity subtype...

Treatment by comorbidity subtype

Treatment of psychosis generally begins with antipsychotics. Nominal psychotherapy (presence of a professionally detached, compassionate clinician) improves compliance and leads to supportive therapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and dialectical behavior therapy may help later, with limited interpersonal approaches further on for some patients.

The suggested approaches to pharmacotherapy noted here draw on research and clinical experience.1,14,19-21 All medications used to treat comorbidities noted here are approved or generally accepted for that diagnosis. Estimated doses are similar to those for comorbidities when patients are nonpsychotic, and vary among patients. Doses, dosing schedules, and titration are extremely important for full benefit. Always consider compliance issues, suicidality, possible adverse effects, and potential drug/drug interactions. Although the medications we suggest using to treat the comorbidities may appear to also benefit psychosis, only antipsychotics are approved for psychosis per se.

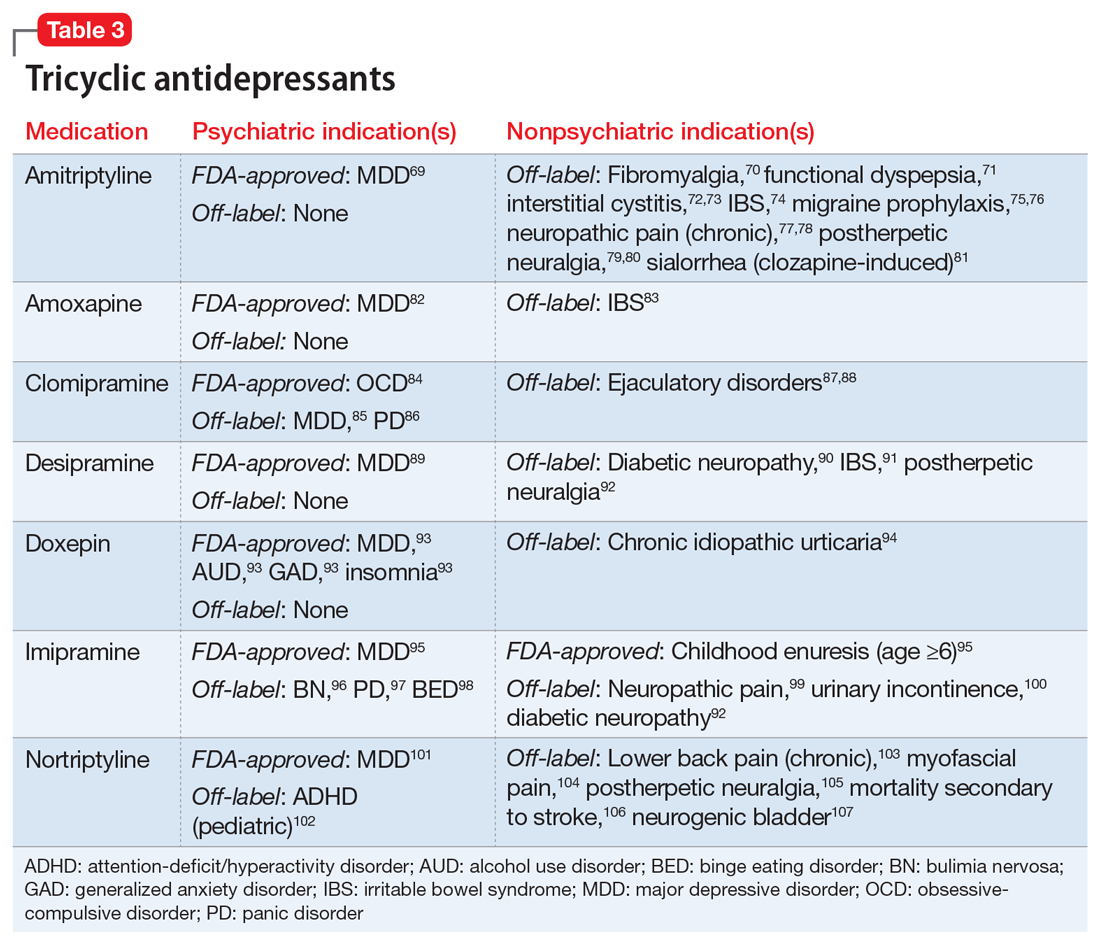

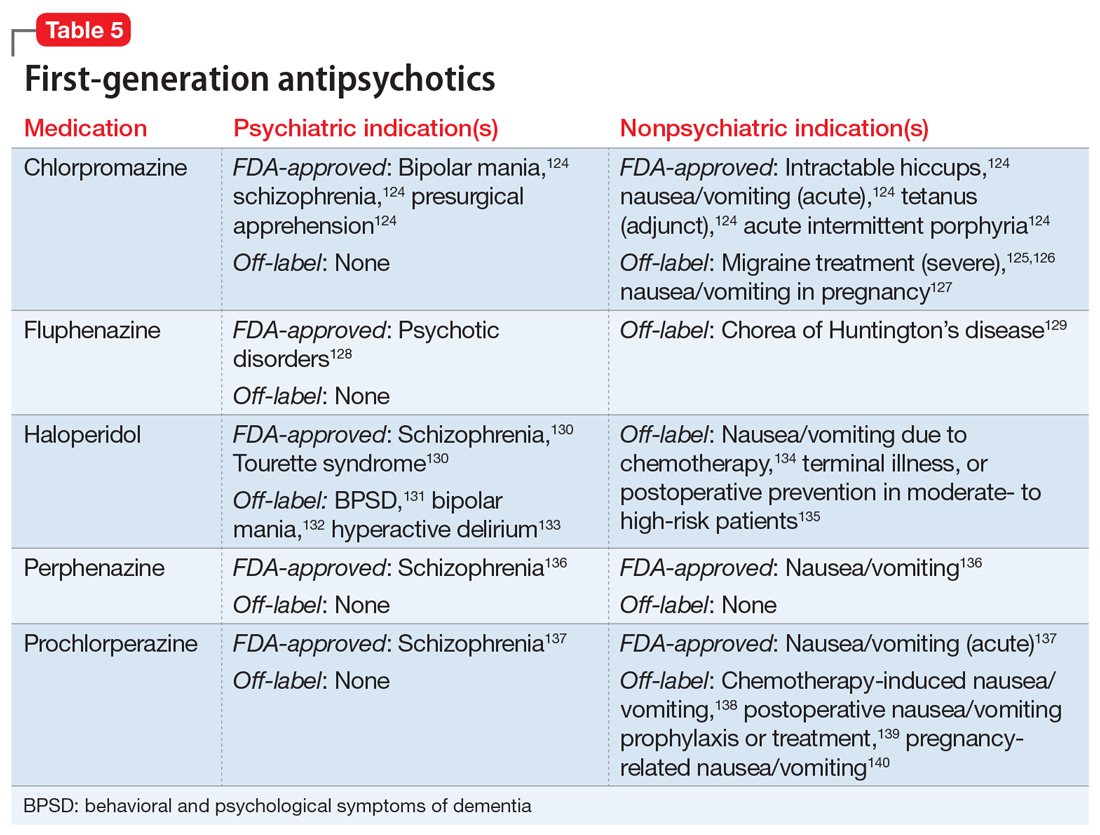

Delusional depression. Antipsychotic + antidepressant. Tricyclic antidepressants are possibly most effective, but increase the risk of overdose and dangerous falls among fragile patients. Electroconvulsive therapy is sometimes used.

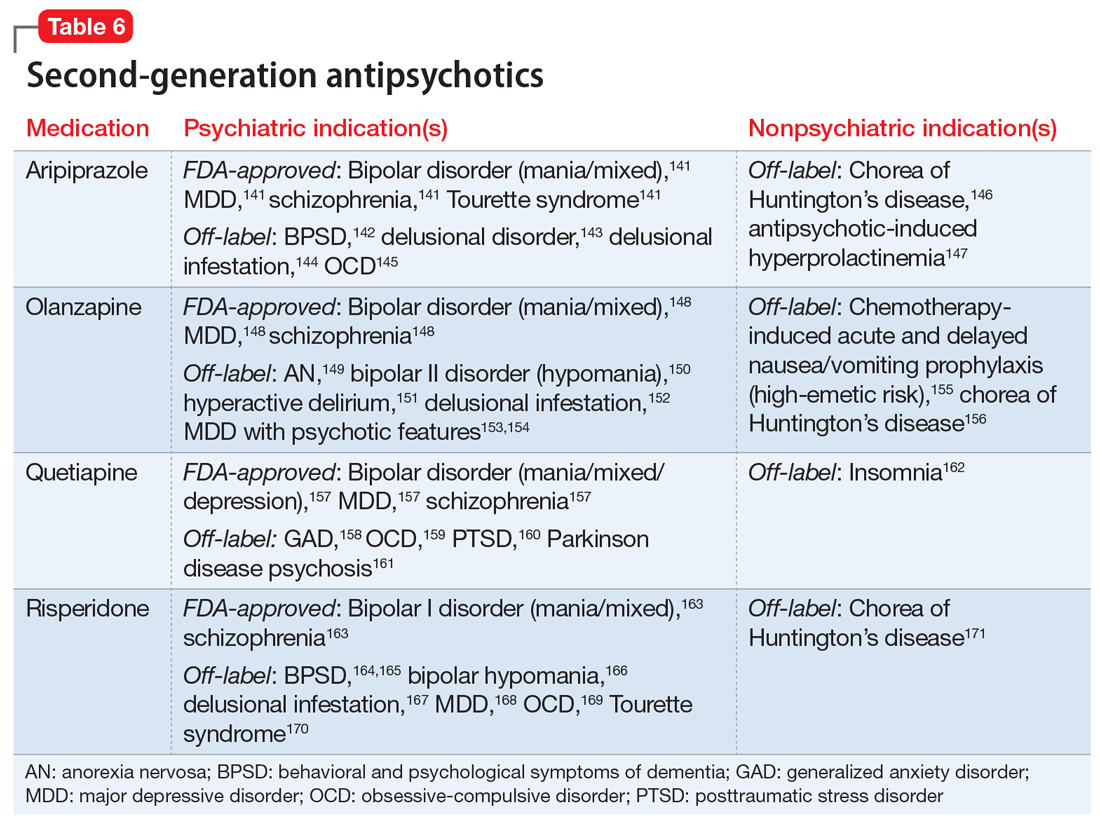

Obsessive-compulsive schizophrenia. Antipsychotic + selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Consider aripiprazole (

Schizophrenia with voices. Antipsychotic + clonazepam. Concurrent usage may stabilize psychosis more rapidly, and with a lower antipsychotic dose.23 Titrate a fixed dose of clonazepam every 12 hours (avoid as-needed doses), starting low (ie, 0.5 mg) to limit initial drowsiness (which typically diminishes in 3 to 10 days). Titrate to full voice and panic cessation (1 to 2.5 mg every 12 hours).14 Exercise caution about excessive drowsiness, as well as outpatient compliance and abuse. Besides alprazolam, other antipanic medications have little incidental benefit for psychosis.

Persecutory delusional disorder. Antipsychotic + SSRI. Aripiprazole (consider long-acting injectable for compliance) also enhances the benefits of fluoxetine for social anxiety. Long half-life fluoxetine (20 mg/d) improves compliance and near-term outcomes.

Bipolar I mania: mania with delusions. Consider olanzapine for acute phase, then add other antimanic medication (commonly lithium or valproic acid), check blood level, and then taper olanzapine some weeks later. Importantly, lamotrigine is not effective for bipolar I mania. Consider suicide risk, medical conditions, and outpatient compliance. Comorbid panic anxiety is also common in bipolar I mania, often presenting as nonthreatening voices.

Seasonality: Following research that bipolar I mania is more common in spring and summer, studies have shown beneficial clinical augmentation from dark therapy as provided by reduced light exposure, blue-blocking glasses, and exogenous melatonin (a darkness-signaling hormone).24

Bipolar I mania atypical depression (significant current or historical symptoms). SSRI + booster medication. An SSRI (ie, escitalopram, 10 mg/d) is best started several weeks after full bipolar I mania resolution, while also continuing long-term antimanic medication. Booster medications (ie, buspirone 15 mg every 12 hours; lithium 300 mg/d; or trazodone 50 mg every 12 hours) can enhance SSRI benefits. Meta-analysis suggests SSRIs may have limited risk of inducing bipolar I mania.25 Although not yet specifically tested for atypical depression, lamotrigine may be effective, and may be safer still.25 However, lamotrigine requires very gradual dose titration to prevent a potentially dangerous rash, including after periods of outpatient noncompliance.

Seasonality: Atypical depression is often worse in winter (seasonal affective disorder). Light therapy can produce some clinically helpful benefits year-round.

To illustrate this new approach to psychosis diagnosis and treatment, our book

Box 2

Ms. B, a studious 19-year-old, has been very shy since childhood, with few friends. Meeting new people always gave her gradually increasing anxiety, thinking that she would embarrass herself in their eyes. She had that same anxiety, along with sweating and tachycardia, when she couldn’t avoid speaking in front of class. Sometimes, while walking down the street she would think that strangers were casting a disdainful eye on her, though she knew that wasn’t true. Another anxiety started when she was 16. While looking for paper in a small supply closet, she suddenly felt panicky. With a racing heart and short of breath, she desperately fled the closet. These episodes continued, sometimes for no apparent reason, and nearly always unnoticed by others.

At age 17, she began to believe that those strangers on the street were looking down on her with evil intent, and even following her around. She became afraid to walk around town. A few months later, she also started to hear angry and critical voices at sudden moments. Although the paroxysmal voices always coincided with her panicky symptoms, the threatening voices now felt more important to her than the panic itself. Nonpsychotic panics had stopped. Mostly a recluse, she saw less of her family, left her job, and stopped going to the movies.

After a family dinner, she was detached, scared, and quieter than usual. She sought help from her primary care physician, who referred her to a psychiatrist. A thorough history from Ms. B and her family revealed her disturbing fears, as well as her history of social anxiety. Interviewing for panic was prompted by her mother’s recollection of the supply closet story.

In view of Ms. B’s cooperativeness and supportive family, outpatient treatment of her recent-onset psychosis began with aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, and clonazepam, 0.5 mg every 12 hours. Clonazepam was gradually increased until voices (and panic) ceased. She was then able to describe how earlier panics had felt just like voices, but without the voices. The fears of strangers continued. Escitalopram, 20 mg/d, was added for social anxiety (aripiprazole enhances the benefits of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors).

One month later, her fears of strangers diminished, and she felt more comfortable around people than ever before. On the same medications, and in psychotherapy over the next year, she began to increase her social network while making plans to start college.

Larger studies are needed

Current research supports the concept of a 5-diagnosis classification of psychoses, which may correlate with our comorbid anxiety and depression model. Larger diagnostic and treatment studies would invaluably examine existing research and clinical experience, and potentially encourage more clinically useful diagnoses, specific treatments, and improved outcomes.

Bottom Line

New insights from evolutionary psychopathology, clinical research and observation, psychotogenesis, genetics, and epidemiology suggest that most functional psychoses may fall into 1 of 5 comorbidity-defined subtypes, for which specific treatments can lead to much improved outcomes.

1. Veras AB, Kahn JP, eds. Psychotic Disorders: Comorbidity Detection Promotes Improved Diagnosis and Treatment. Elsevier; 2021.

2. Gaebel W, Zielasek J. Focus on psychosis. Dialogues Clin Neuroscience. 2015;17(1):9-18.

3. Guloksuz S, Van Os J. The slow death of the concept of schizophrenia and the painful birth of the psychosis spectrum. Psychological Medicine. 2018;48(2):229-244.

4. Bleuler E. Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias. International Universities Press; 1950.

5. Kahn JP. Angst: Origins of Depression and Anxiety. Oxford University Press; 2013.

6. Howes OD, McCutcheon R, Owen MJ, et al. The role of genes, stress, and dopamine in the development of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81(1):9-20.

7. Mubarik A, Tohid H. Frontal lobe alterations in schizophrenia: a review. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2016;38(4):198-206.

8. Murray RM, Bhavsar V, Tripoli G, et al. 30 Years on: How the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia morphed into the developmental risk factor model of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(6):1190-1196.

9. Bauer M, Glenn T, Alda M, et al. Solar insolation in springtime influences age of onset of bipolar I disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(6):571-582.

10. Kahn JP, Bombassaro T, Veras AB. Comorbid schizophrenia and panic anxiety: panic psychosis revisited. Psychiatr Ann. 2018;48(12):561-565.

11. Bebbington P, Freeman D. Transdiagnostic extension of delusions: schizophrenia and beyond. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(2):273-282.

12. Catalan A, Simons CJP, Bustamante S, et al. Data gathering bias: trait vulnerability to psychotic symptoms? PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132442. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132442

13. Goodwin R, Lyons JS, McNally RJ. Panic attacks in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2002;58(2-3):213-220.

14. Kahn JP, Puertollano MA, Schane MD, et al. Adjunctive alprazolam for schizophrenia with panic anxiety: clinical observation and pathogenetic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(6):742-744.

15. Kahn JP. Chapter 4: Paranoid schizophrenia with voices and panic anxiety. In: Veras AB, Kahn JP, eds. Psychotic Disorders: Comorbidity Detection Promotes Improved Diagnosis and Treatment. Elsevier; 2021.

16. Achim AM, Maziade M, Raymond E, et al. How prevalent are anxiety disorders in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis and critical review on a significant association. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(4):811-821.

17. Veras AB, Souza TG, Ricci TG, et al. Paranoid delusional disorder follows social anxiety disorder in a long-term case series: evolutionary perspective. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(6):477-479.

18. McIntyre JC, Wickham S, Barr B, et al. Social identity and psychosis: associations and psychological mechanisms. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(3):681-690.

19. Barbee JG, Mancuso DM, Freed CR. Alprazolam as a neuroleptic adjunct in the emergency treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(4):506-510.

20. Nardi AE, Machado S, Almada LF. Clonazepam for the treatment of panic disorder. Curr Drug Targets. 2013;14(3):353-364.

21. Poyurovsky M. Schizo-Obsessive Disorder. Cambridge University Press; 2013.

22. Reznik I, Sirota P. Obsessive and compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial with fluvoxamine and neuroleptics. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20(4):410-416.

23. Bodkin JA. Emerging uses for high-potency benzodiazepines in psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51 Suppl:41-53.

24. Gottlieb JF, Benedetti F, Geoffroy PA, et al. The chronotherapeutic treatment of bipolar disorders: a systematic review and practice recommendations from the ISBD task force on chronotherapy and chronobiology. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(8):741-773.

25. Pacchiarotti I, Bond DJ, Baldessarini RJ, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) task force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(11):1249-1262.

How can we treat psychosis if we don’t know what we are treating? Over the years, attempts at defining psychosis subtypes have met with dead ends. However, recent research supports a new approach that offers a rational classification model organized according to 5 specific comorbid anxiety and depressive disorder diagnoses.

Anxiety and depressive symptoms are not just the result of psychotic despair. They are specific diagnoses, they precede psychosis onset, they help define psychotic syndromes, and they can point to much more effective treatment approaches. Most of the psychotic diagnoses in this schema are already recognized or posited. And, just as patients who do not have psychotic illness can have more than 1 anxiety or depressive disorder, patients with psychosis can present with a mixed picture that reflects more than 1 contributing comorbidity. Research further suggests that each of the 5 psychosis comorbidity diagnoses may involve some similar underlying factors that facilitate the formation of psychosis.

This article describes the basics of 5 psychosis subtypes, and provides initial guidelines to diagnosis, symptomatology, and treatment. Though clinical experience and existing research support the clinical presence and treatment value of this classification model, further verification will require considerably more controlled studies. An eventual validation of this approach could largely supplant ill-defined diagnoses of “schizophrenia” and other functional psychoses.

Recognizing the comorbidities in the context of their corresponding psychoses entails learning new interviewing skills and devoting more time to both initial and subsequent diagnosis and treatment. In our recently published book,1 we provide extensive details on the approach we describe in this article, including case examples, new interview tools to simplify the diagnostic journey, and novel treatment approaches.

Psychosis-proneness underlies functional psychoses

Functional (idiopathic) schizophrenia and psychotic disorders have long been difficult to separate, and many categorizations have been discarded. Despite clinical dissimilarities, today we too often casually lump psychoses together as schizophrenia.2,3 Eugen Bleuler first suggested the existence of a “group of schizophrenias.”4 It is possible that his group encompasses our 5 psychoses from 5 inbuilt emotional instincts,5 each corresponding to a specific anxiety or depressive subtype.

The 5 anxiety and depressive subtypes noted in this article are common, but psychosis is not. Considerable research suggests that certain global “psychotogenic” factors create susceptibility to all psychoses.6,7 While many genetic, neuroanatomical, experiential, and other factors have been reported, the most important may be “hypofrontality” (genetically reduced frontal lobe function, size, or neuronal activity) and dopaminergic hyperfunction (genetically increased dopamine activity).5-7

An evolutionary perspective

One evolutionary theory of psychopathology starts with the subtypes of depression and anxiety. For example, major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder may encompass 5 commonplace and more specific anxiety and depressive subtypes. Consideration of the emotional, cognitive, and functional aspects of those subtypes suggests that they may have once been advantageous for primeval human herds. Those primeval altruistic instincts may have helped survival, reproduction, and preservation of kin group DNA.5

More than any other species, humans can draw upon consciousness and culture to rationally overcome the influences of unconscious instincts. But those instincts can then emerge from the deep, and painfully encourage obedience to their guidance. In nonpsychotic anxiety and depressive disorders, the specific messages are experienced as specific anxiety and depressive symptoms.5 In psychotic disorders, the messages can emerge as unreasoned and frightful fears, perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors. With newer research, clinical observation, and an evolutionary perspective, a novel and counterintuitive approach may improve our ability to help patients.8

Continue to: Five affective comorbidities evolved from primeval altruistic instincts...

Five affective comorbidities evolved from primeval altruistic instincts

Melancholic depression5

Melancholic depression is often triggered by serious illness, group exclusion, pronounced loss, or purposelessness. We hear patients talk painfully about illness, guilt, and death. Indeed, some increased risk of death, especially from infectious disease, may result from hypercortisolemia (documented by the dexamethasone suppression test). Hypercortisolemic death also occurs in salmon after spawning, and in male marsupial mice after mating. The tragic passing of an individual saves scarce resources for the remainder of the herd.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder5

Factor-analytic studies suggest 4 main obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) subtypes: cleanliness, hoarding, intrusive thoughts, and organizing. Obsessive-compulsive traits can help maintain a safe and efficient environment in humans and other species, but OCD is dysfunctional.

Panic anxiety5

Panic anxiety is triggered by real, symbolic, or emotional separation from home and family. In toddlers, separation anxiety can reduce the odds of getting lost and hurt.

Social anxiety5

Social anxiety includes fear of self-embarrassment, exposure as a pretender to higher social rank, and thus often a reluctant avoidance of increased social rank. While consciousness and cultural encouragement can overcome that hesitation and thus lead to greater success, social anxiety activation can still cause painful anxiety. The social hierarchies of many species include comparable biological influences, and help preserve group DNA by reducing hierarchical infighting.

Atypical depression and bipolar I mania5

Atypical depression includes increased rejection sensitivity, resulting in inoffensive behavior to avoid social rejection. This reduces risk of isolation from the group, and improves group harmony. Unlike the 4 other syndromes, atypical depression and bipolar I mania may reflect 2 separate seasonal mood phases. Atypical depression (including seasonal affective disorder) often worsens with shortened winter daylight hours, akin to hibernation. Initial bipolar I mania is more common with springtime daylight, with symptoms not unlike exaggerated hibernation awakening.9

Primeval biological altruism has great evolutionary value in many species, and even somewhat in modern humans. But it is quite different from modern rational altruism. Although we sometimes override our instincts, they respond with messages experienced as emotional pain—they still tell us to follow instructions for primeval herd survival. In an earlier book, I (JPK) provide a lengthier description of the evidence for this evolutionary psychopathology theory, including interplay of the 5 instincts with psychotogenic factors.5

Continue to: Five comorbidity psychoses from 5 primeval instincts.....

Five comorbidity psychoses from 5 primeval instincts

The 5 affective comorbidities described above contribute to the presence, subtype, and treatment approaches of 5 corresponding psychoses. Ordinary panic attacks might occur when feeling trapped or separated from home, so people want to flee to safety. Nonhuman species with limited consciousness and language are unlikely to think “time to head for safety.” Instead, instincts encourage flight from danger through internally generated perceptions of threat. Likewise, people with psychosis and panic, without sufficient conscious modulation, may experience sensory perceptions of actual danger when feeling symbolically trapped.1,10

One pilot study carefully examined the prevalence of these 5 comorbidities in an unselected group of psychotic patients.10 At least 85% met criteria for ≥1 of the 5 subtypes.10 Moreover, organic psychoses related to physical illness, substances, and iatrogenesis may also predict future episodes of functional psychoses.1

Using statistical analysis of psychosis rating scales, 2 studies took a “transdiagnostic” look at psychoses, and each found 5 psychosis subtypes and a generalized psychosis susceptibility factor.11,12 Replication of that transdiagnostic approach, newly including psychosis symptoms and our 5 specific comorbidities, might well find that the 5 subtype models resemble each other.11,12

Our proposed 5 comorbidity subtypes are1:

Delusional depression (melancholic depression). Most common in geriatric patients, this psychosis can also occur at younger ages. Prodromal melancholic depression can include guilt and hopelessness, and is acute, rather than the chronic course of our other 4 syndromes. Subsequent delusional depression includes delusions of bodily decay, illness, or death, as well as overwhelming guilt, shame, and remorse. The classic vegetative symptoms of depression continue. In addition to infectious disease issues, high suicide risk makes hospitalization imperative.

Obsessive-compulsive schizophrenia. Just as OCD has an early age of onset, obsessive-compulsive schizophrenia begins earlier than other psychoses. Despite preserved cognition, some nonpsychotic patients with OCD have diminished symptom insight. OCD may be comorbid with schizophrenia in 12% of cases, typically preceding psychosis onset. Obsessive-compulsive schizophrenia symptoms may include highly exaggerated doubt or ambivalence; contamination concerns; eccentric, ritualistic, motor stereotypy, checking, disorganized, and other behaviors; and paranoia.

Schizophrenia with voices (panic anxiety). Classic paranoid schizophrenia with voices appears to be the most similar to a “panic psychosis.” Patients with nonpsychotic panic anxiety have increased paranoid ideation and ideas of reference as measured on the Symptom Checklist-90. Schizophrenia is highly comorbid with panic anxiety, estimated at 45% in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study.13 These are likely underestimates: cognitive impairment hinders reporting, and psychotic panic is masked as auditory hallucinations. A pilot study of schizophrenia with voices using a carbon dioxide panic induction challenge found that 100% had panic anxiety.14 That study and another found that virtually all participants reported voices concurrent with panic using our Panic and Schizophrenia Interview (PaSI) (Box 1). Panic onset precedes schizophrenia onset, and panic may reappear if antipsychotic medications sufficiently control voices: “voices without the voices,” say some.

Box 1

Let’s talk for a minute about your voices.

[IDENTIFYING PAROXYSMAL MOMENTS OF VOICE ONSET]

Do you hear voices at every single moment, or are they sometimes silent? Think about those times when you are not actually hearing any voices.

Now, there may be reasons why the voices start talking when they do, but let’s leave that aside for now.

So, whenever the voices do begin speaking—and for whatever reason they do—is it all of a sudden, or do they start very softly and then very gradually get louder?

If your voices are nearly always there, then are there times when the voices suddenly come back, get louder, get more insistent, or just get more obvious to you?

[Focus patient on sudden moment of voice onset, intensification, or awareness]

Let’s talk about that sudden moment when the voices begin (or intensify, or become obvious), even if you know the reason why they start.

I’m going to ask you about some symptoms that you might have at that same sudden moment when the voices start (or intensify, or become obvious). If you have any of these symptoms at the other times, they do not count for now.

So, when I ask about each symptom, tell me whether it comes on at the same sudden moments as the voices, and also if it used to come on with the voices in the past.

For each sudden symptom, just say “YES” or “NO” or “SOMETIMES.”

[Begin each query with: “At the same sudden moment that the voices come on”]

- Sudden anxiety, fear, or panic on the inside?

- Sudden anger or rage on the inside? [ANGER QUERY]

- Sudden heart racing? Heart pounding?

- Sudden chest pain? Chest pressure?

- Sudden sweating?

- Sudden trembling or shaking?

- Sudden shortness of breath, or like you can’t catch your breath?

- Sudden choking or a lump in your throat?

- Sudden nausea or queasiness?

- Sudden dizziness, lightheadedness, or faintness?

- Sudden feeling of detachment, sort of like you are in a glass box?

- Sudden fear of losing control? Fear of going crazy?

- Sudden fear afraid of dying? Afraid of having a heart attack?

- Sudden numbness or tingling, especially in your hands or face?

- Sudden feeling of heat, or cold?

- Sudden itching in your teeth? [VALIDITY CHECK]

- Sudden fear that people want to hurt you? [EXCESS FEAR QUERY]

- Sudden voices? [VOICES QUERY]

[PAST & PRODROMAL PANIC HISTORY]

At what age did you first see a therapist or psychiatrist?

At what age were you first hospitalized for an emotional problem?

At what age did you first start hearing voices?

At what age did you first start having strong fears of other people?

Before you ever heard voices, did you ever have any of the other sudden symptoms like the ones we just talked about?

Did those episodes back then feel sort of like your voices or sudden fears do now, except that there were no voices or sudden fears of people back then?

At what age did those sudden anxiety (or panic or rage) episodes begin?

Back then, was there MORE (M) sudden anxiety, or the SAME (S) sudden anxiety, or LESS (L) sudden anxiety than with your sudden voices now?

[PAST & PRODROMAL PANIC SYMPTOMS]

Now let’s talk about some symptoms that you might have had at those same sudden anxiety moments, in the time before you ever heard any voices. So, for each sudden symptom just say “YES” or “NO” or “SOMETIMES.”

[Begin each query with: “At the same moment the sudden anxiety came on—but only during the time before you ever heard sudden voices”]

[Ask about the same 18 panic-related symptoms listed above]

[PHOBIA-RELATED PANIC AND VOICES]

Have you ever been afraid to go into a (car, bus, plane, train, subway, elevator, mall, tunnel, bridge, heights, small place, CAT scan or MRI, being alone, crowds)?

[If yes or maybe: Ask about panic symptoms in phobic situations]

Now let’s talk about some symptoms that you might have had at some of those times you were afraid. So, for each symptom just say “YES” or “NO” or “MAYBE.”

[Ask about the same 18 panic-related symptoms listed above]

At what age did you last have sudden anxiety without voices?

Has medication ever completely stopped your voices? Somewhat?

If so, did those other sudden symptoms still happen sometimes?

Thank you for your help, and for answering all of these questions!

Persecutory delusional disorder (social anxiety). Some “schizophrenia” without voices may be misdiagnosis of persecutory (paranoid) delusional disorder (PDD). Therefore, the reported population prevalence (0.02%) may be underestimated. Social anxiety is highly comorbid with “schizophrenia” (15%).16 Case reports and clinical experience suggest that PDD is commonly preceded by social anxiety.17 Some nonpsychotic social anxiety symptoms closely resemble the PDD psychotic ideas of reference (a perception that low social rank attracts critical scrutiny by authorities). Patients with PDD may remain relatively functional, with few negative symptoms, despite pronounced paranoia. Outward manifestation of paranoia may be limited, unless quite intense. The typical age of onset (40 years) is later than that of schizophrenia, and symptoms can last a long time.18

Continue to: Bipolar 1 mania with delusions...

Bipolar I mania with delusions (atypical depression). Atypical depression is the most common depression in bipolar I disorder. Often more pronounced in winter, it may intensify at any time of year. Long ago, hypersomnia, lethargy, inactivity, inoffensiveness, and craving high-calorie food may have been conducive to hibernation.

Bipolar I mania includes delusions of special accomplishments or abilities, energetically focused on a grandiose mission to help everyone. These intense symptoms may be related to reduced frontal lobe modulation. In some milder form, bipolar I mania may once have encouraged hibernation awakening. Indeed, initial bipolar I mania episodes are more common in spring, as is the spring cleaning that helps us prepare for summer.

Recognizing affective trees in a psychotic forest

Though long observed, comorbid affective symptoms have generally been considered a hodgepodge of distress caused by painful psychotic illness. But the affective symptoms precede psychosis onset, can be masked during acute psychosis, and will revert to ordinary form if psychosis abates.11-13

Rather than affective symptoms being a consequence of psychosis, it may well be the other way around. Affective disorders could be important causal and differentiating components of psychotic disorders.11-13 Research and clinical experience suggest that adjunctive treatment of the comorbidities with correct medication can greatly enhance outcome.

Diagnostic approaches

Because interviews of patients with psychosis are often complicated by confusion, irritability, paranoid evasiveness, cognitive impairment, and medication, nuanced diagnosis is difficult. Interviews should explore psychotic syndromes and subtypes that correlate with comorbidity psychoses, including pre-psychotic anxiety and depressive diagnoses that are chronic (though unlike our 4 other diagnoses, melancholic depression is not chronic).

Establishing pre-psychotic diagnosis of chronic syndromes suggests that they are still present, even if they are difficult to assess during psychosis. Re-interview after some improvement allows for a significantly better diagnosis. Just as in nonpsychotic affective disorders, multiple comorbidities are common, and can lead to a mixed psychotic diagnosis and treatment plan.1

Structured interview tools can assist diagnosis. The PaSI (Box 1,15) elicits past, present, and detailed history of DSM panic, and has been validated in a small pilot randomized controlled trial. The PaSI focuses patient attention on paroxysmal onset voices, and then evaluates the presence of concurrent DSM panic symptoms. If voices are mostly psychotic panic, they may well be a proxy for panic. Ultimately, diagnosis of 5 comorbidities and associated psychotic symptoms may allow simpler categorization into 1 (or more) of the 5 psychosis subtypes.

Continue to: Treatment by comorbidity subtype...

Treatment by comorbidity subtype

Treatment of psychosis generally begins with antipsychotics. Nominal psychotherapy (presence of a professionally detached, compassionate clinician) improves compliance and leads to supportive therapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and dialectical behavior therapy may help later, with limited interpersonal approaches further on for some patients.

The suggested approaches to pharmacotherapy noted here draw on research and clinical experience.1,14,19-21 All medications used to treat comorbidities noted here are approved or generally accepted for that diagnosis. Estimated doses are similar to those for comorbidities when patients are nonpsychotic, and vary among patients. Doses, dosing schedules, and titration are extremely important for full benefit. Always consider compliance issues, suicidality, possible adverse effects, and potential drug/drug interactions. Although the medications we suggest using to treat the comorbidities may appear to also benefit psychosis, only antipsychotics are approved for psychosis per se.

Delusional depression. Antipsychotic + antidepressant. Tricyclic antidepressants are possibly most effective, but increase the risk of overdose and dangerous falls among fragile patients. Electroconvulsive therapy is sometimes used.

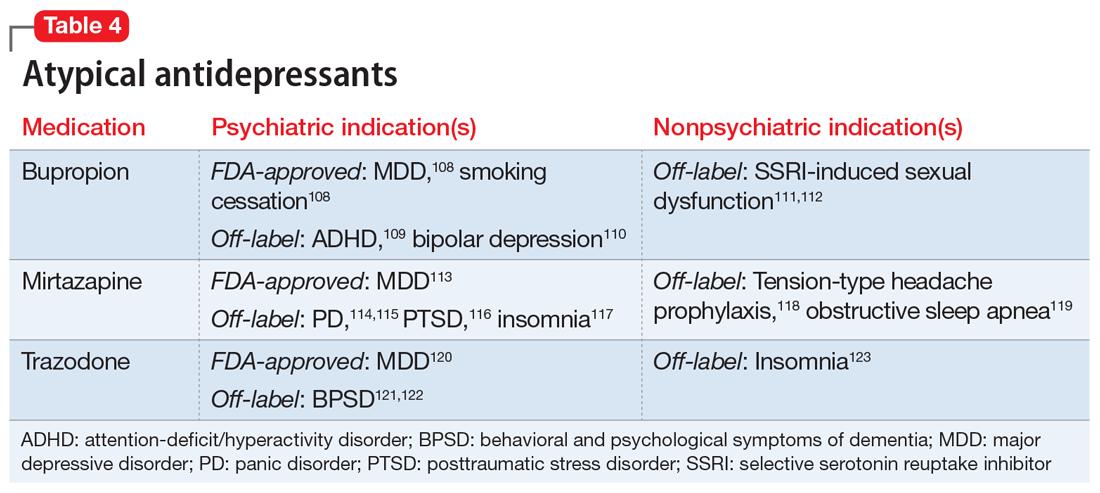

Obsessive-compulsive schizophrenia. Antipsychotic + selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Consider aripiprazole (

Schizophrenia with voices. Antipsychotic + clonazepam. Concurrent usage may stabilize psychosis more rapidly, and with a lower antipsychotic dose.23 Titrate a fixed dose of clonazepam every 12 hours (avoid as-needed doses), starting low (ie, 0.5 mg) to limit initial drowsiness (which typically diminishes in 3 to 10 days). Titrate to full voice and panic cessation (1 to 2.5 mg every 12 hours).14 Exercise caution about excessive drowsiness, as well as outpatient compliance and abuse. Besides alprazolam, other antipanic medications have little incidental benefit for psychosis.

Persecutory delusional disorder. Antipsychotic + SSRI. Aripiprazole (consider long-acting injectable for compliance) also enhances the benefits of fluoxetine for social anxiety. Long half-life fluoxetine (20 mg/d) improves compliance and near-term outcomes.

Bipolar I mania: mania with delusions. Consider olanzapine for acute phase, then add other antimanic medication (commonly lithium or valproic acid), check blood level, and then taper olanzapine some weeks later. Importantly, lamotrigine is not effective for bipolar I mania. Consider suicide risk, medical conditions, and outpatient compliance. Comorbid panic anxiety is also common in bipolar I mania, often presenting as nonthreatening voices.

Seasonality: Following research that bipolar I mania is more common in spring and summer, studies have shown beneficial clinical augmentation from dark therapy as provided by reduced light exposure, blue-blocking glasses, and exogenous melatonin (a darkness-signaling hormone).24

Bipolar I mania atypical depression (significant current or historical symptoms). SSRI + booster medication. An SSRI (ie, escitalopram, 10 mg/d) is best started several weeks after full bipolar I mania resolution, while also continuing long-term antimanic medication. Booster medications (ie, buspirone 15 mg every 12 hours; lithium 300 mg/d; or trazodone 50 mg every 12 hours) can enhance SSRI benefits. Meta-analysis suggests SSRIs may have limited risk of inducing bipolar I mania.25 Although not yet specifically tested for atypical depression, lamotrigine may be effective, and may be safer still.25 However, lamotrigine requires very gradual dose titration to prevent a potentially dangerous rash, including after periods of outpatient noncompliance.

Seasonality: Atypical depression is often worse in winter (seasonal affective disorder). Light therapy can produce some clinically helpful benefits year-round.

To illustrate this new approach to psychosis diagnosis and treatment, our book

Box 2

Ms. B, a studious 19-year-old, has been very shy since childhood, with few friends. Meeting new people always gave her gradually increasing anxiety, thinking that she would embarrass herself in their eyes. She had that same anxiety, along with sweating and tachycardia, when she couldn’t avoid speaking in front of class. Sometimes, while walking down the street she would think that strangers were casting a disdainful eye on her, though she knew that wasn’t true. Another anxiety started when she was 16. While looking for paper in a small supply closet, she suddenly felt panicky. With a racing heart and short of breath, she desperately fled the closet. These episodes continued, sometimes for no apparent reason, and nearly always unnoticed by others.

At age 17, she began to believe that those strangers on the street were looking down on her with evil intent, and even following her around. She became afraid to walk around town. A few months later, she also started to hear angry and critical voices at sudden moments. Although the paroxysmal voices always coincided with her panicky symptoms, the threatening voices now felt more important to her than the panic itself. Nonpsychotic panics had stopped. Mostly a recluse, she saw less of her family, left her job, and stopped going to the movies.

After a family dinner, she was detached, scared, and quieter than usual. She sought help from her primary care physician, who referred her to a psychiatrist. A thorough history from Ms. B and her family revealed her disturbing fears, as well as her history of social anxiety. Interviewing for panic was prompted by her mother’s recollection of the supply closet story.

In view of Ms. B’s cooperativeness and supportive family, outpatient treatment of her recent-onset psychosis began with aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, and clonazepam, 0.5 mg every 12 hours. Clonazepam was gradually increased until voices (and panic) ceased. She was then able to describe how earlier panics had felt just like voices, but without the voices. The fears of strangers continued. Escitalopram, 20 mg/d, was added for social anxiety (aripiprazole enhances the benefits of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors).

One month later, her fears of strangers diminished, and she felt more comfortable around people than ever before. On the same medications, and in psychotherapy over the next year, she began to increase her social network while making plans to start college.

Larger studies are needed

Current research supports the concept of a 5-diagnosis classification of psychoses, which may correlate with our comorbid anxiety and depression model. Larger diagnostic and treatment studies would invaluably examine existing research and clinical experience, and potentially encourage more clinically useful diagnoses, specific treatments, and improved outcomes.

Bottom Line

New insights from evolutionary psychopathology, clinical research and observation, psychotogenesis, genetics, and epidemiology suggest that most functional psychoses may fall into 1 of 5 comorbidity-defined subtypes, for which specific treatments can lead to much improved outcomes.

How can we treat psychosis if we don’t know what we are treating? Over the years, attempts at defining psychosis subtypes have met with dead ends. However, recent research supports a new approach that offers a rational classification model organized according to 5 specific comorbid anxiety and depressive disorder diagnoses.

Anxiety and depressive symptoms are not just the result of psychotic despair. They are specific diagnoses, they precede psychosis onset, they help define psychotic syndromes, and they can point to much more effective treatment approaches. Most of the psychotic diagnoses in this schema are already recognized or posited. And, just as patients who do not have psychotic illness can have more than 1 anxiety or depressive disorder, patients with psychosis can present with a mixed picture that reflects more than 1 contributing comorbidity. Research further suggests that each of the 5 psychosis comorbidity diagnoses may involve some similar underlying factors that facilitate the formation of psychosis.

This article describes the basics of 5 psychosis subtypes, and provides initial guidelines to diagnosis, symptomatology, and treatment. Though clinical experience and existing research support the clinical presence and treatment value of this classification model, further verification will require considerably more controlled studies. An eventual validation of this approach could largely supplant ill-defined diagnoses of “schizophrenia” and other functional psychoses.

Recognizing the comorbidities in the context of their corresponding psychoses entails learning new interviewing skills and devoting more time to both initial and subsequent diagnosis and treatment. In our recently published book,1 we provide extensive details on the approach we describe in this article, including case examples, new interview tools to simplify the diagnostic journey, and novel treatment approaches.

Psychosis-proneness underlies functional psychoses

Functional (idiopathic) schizophrenia and psychotic disorders have long been difficult to separate, and many categorizations have been discarded. Despite clinical dissimilarities, today we too often casually lump psychoses together as schizophrenia.2,3 Eugen Bleuler first suggested the existence of a “group of schizophrenias.”4 It is possible that his group encompasses our 5 psychoses from 5 inbuilt emotional instincts,5 each corresponding to a specific anxiety or depressive subtype.

The 5 anxiety and depressive subtypes noted in this article are common, but psychosis is not. Considerable research suggests that certain global “psychotogenic” factors create susceptibility to all psychoses.6,7 While many genetic, neuroanatomical, experiential, and other factors have been reported, the most important may be “hypofrontality” (genetically reduced frontal lobe function, size, or neuronal activity) and dopaminergic hyperfunction (genetically increased dopamine activity).5-7

An evolutionary perspective

One evolutionary theory of psychopathology starts with the subtypes of depression and anxiety. For example, major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder may encompass 5 commonplace and more specific anxiety and depressive subtypes. Consideration of the emotional, cognitive, and functional aspects of those subtypes suggests that they may have once been advantageous for primeval human herds. Those primeval altruistic instincts may have helped survival, reproduction, and preservation of kin group DNA.5

More than any other species, humans can draw upon consciousness and culture to rationally overcome the influences of unconscious instincts. But those instincts can then emerge from the deep, and painfully encourage obedience to their guidance. In nonpsychotic anxiety and depressive disorders, the specific messages are experienced as specific anxiety and depressive symptoms.5 In psychotic disorders, the messages can emerge as unreasoned and frightful fears, perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors. With newer research, clinical observation, and an evolutionary perspective, a novel and counterintuitive approach may improve our ability to help patients.8

Continue to: Five affective comorbidities evolved from primeval altruistic instincts...

Five affective comorbidities evolved from primeval altruistic instincts

Melancholic depression5

Melancholic depression is often triggered by serious illness, group exclusion, pronounced loss, or purposelessness. We hear patients talk painfully about illness, guilt, and death. Indeed, some increased risk of death, especially from infectious disease, may result from hypercortisolemia (documented by the dexamethasone suppression test). Hypercortisolemic death also occurs in salmon after spawning, and in male marsupial mice after mating. The tragic passing of an individual saves scarce resources for the remainder of the herd.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder5

Factor-analytic studies suggest 4 main obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) subtypes: cleanliness, hoarding, intrusive thoughts, and organizing. Obsessive-compulsive traits can help maintain a safe and efficient environment in humans and other species, but OCD is dysfunctional.

Panic anxiety5

Panic anxiety is triggered by real, symbolic, or emotional separation from home and family. In toddlers, separation anxiety can reduce the odds of getting lost and hurt.

Social anxiety5

Social anxiety includes fear of self-embarrassment, exposure as a pretender to higher social rank, and thus often a reluctant avoidance of increased social rank. While consciousness and cultural encouragement can overcome that hesitation and thus lead to greater success, social anxiety activation can still cause painful anxiety. The social hierarchies of many species include comparable biological influences, and help preserve group DNA by reducing hierarchical infighting.

Atypical depression and bipolar I mania5

Atypical depression includes increased rejection sensitivity, resulting in inoffensive behavior to avoid social rejection. This reduces risk of isolation from the group, and improves group harmony. Unlike the 4 other syndromes, atypical depression and bipolar I mania may reflect 2 separate seasonal mood phases. Atypical depression (including seasonal affective disorder) often worsens with shortened winter daylight hours, akin to hibernation. Initial bipolar I mania is more common with springtime daylight, with symptoms not unlike exaggerated hibernation awakening.9

Primeval biological altruism has great evolutionary value in many species, and even somewhat in modern humans. But it is quite different from modern rational altruism. Although we sometimes override our instincts, they respond with messages experienced as emotional pain—they still tell us to follow instructions for primeval herd survival. In an earlier book, I (JPK) provide a lengthier description of the evidence for this evolutionary psychopathology theory, including interplay of the 5 instincts with psychotogenic factors.5

Continue to: Five comorbidity psychoses from 5 primeval instincts.....

Five comorbidity psychoses from 5 primeval instincts

The 5 affective comorbidities described above contribute to the presence, subtype, and treatment approaches of 5 corresponding psychoses. Ordinary panic attacks might occur when feeling trapped or separated from home, so people want to flee to safety. Nonhuman species with limited consciousness and language are unlikely to think “time to head for safety.” Instead, instincts encourage flight from danger through internally generated perceptions of threat. Likewise, people with psychosis and panic, without sufficient conscious modulation, may experience sensory perceptions of actual danger when feeling symbolically trapped.1,10

One pilot study carefully examined the prevalence of these 5 comorbidities in an unselected group of psychotic patients.10 At least 85% met criteria for ≥1 of the 5 subtypes.10 Moreover, organic psychoses related to physical illness, substances, and iatrogenesis may also predict future episodes of functional psychoses.1

Using statistical analysis of psychosis rating scales, 2 studies took a “transdiagnostic” look at psychoses, and each found 5 psychosis subtypes and a generalized psychosis susceptibility factor.11,12 Replication of that transdiagnostic approach, newly including psychosis symptoms and our 5 specific comorbidities, might well find that the 5 subtype models resemble each other.11,12

Our proposed 5 comorbidity subtypes are1:

Delusional depression (melancholic depression). Most common in geriatric patients, this psychosis can also occur at younger ages. Prodromal melancholic depression can include guilt and hopelessness, and is acute, rather than the chronic course of our other 4 syndromes. Subsequent delusional depression includes delusions of bodily decay, illness, or death, as well as overwhelming guilt, shame, and remorse. The classic vegetative symptoms of depression continue. In addition to infectious disease issues, high suicide risk makes hospitalization imperative.

Obsessive-compulsive schizophrenia. Just as OCD has an early age of onset, obsessive-compulsive schizophrenia begins earlier than other psychoses. Despite preserved cognition, some nonpsychotic patients with OCD have diminished symptom insight. OCD may be comorbid with schizophrenia in 12% of cases, typically preceding psychosis onset. Obsessive-compulsive schizophrenia symptoms may include highly exaggerated doubt or ambivalence; contamination concerns; eccentric, ritualistic, motor stereotypy, checking, disorganized, and other behaviors; and paranoia.

Schizophrenia with voices (panic anxiety). Classic paranoid schizophrenia with voices appears to be the most similar to a “panic psychosis.” Patients with nonpsychotic panic anxiety have increased paranoid ideation and ideas of reference as measured on the Symptom Checklist-90. Schizophrenia is highly comorbid with panic anxiety, estimated at 45% in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study.13 These are likely underestimates: cognitive impairment hinders reporting, and psychotic panic is masked as auditory hallucinations. A pilot study of schizophrenia with voices using a carbon dioxide panic induction challenge found that 100% had panic anxiety.14 That study and another found that virtually all participants reported voices concurrent with panic using our Panic and Schizophrenia Interview (PaSI) (Box 1). Panic onset precedes schizophrenia onset, and panic may reappear if antipsychotic medications sufficiently control voices: “voices without the voices,” say some.

Box 1

Let’s talk for a minute about your voices.

[IDENTIFYING PAROXYSMAL MOMENTS OF VOICE ONSET]

Do you hear voices at every single moment, or are they sometimes silent? Think about those times when you are not actually hearing any voices.

Now, there may be reasons why the voices start talking when they do, but let’s leave that aside for now.

So, whenever the voices do begin speaking—and for whatever reason they do—is it all of a sudden, or do they start very softly and then very gradually get louder?

If your voices are nearly always there, then are there times when the voices suddenly come back, get louder, get more insistent, or just get more obvious to you?

[Focus patient on sudden moment of voice onset, intensification, or awareness]

Let’s talk about that sudden moment when the voices begin (or intensify, or become obvious), even if you know the reason why they start.

I’m going to ask you about some symptoms that you might have at that same sudden moment when the voices start (or intensify, or become obvious). If you have any of these symptoms at the other times, they do not count for now.

So, when I ask about each symptom, tell me whether it comes on at the same sudden moments as the voices, and also if it used to come on with the voices in the past.

For each sudden symptom, just say “YES” or “NO” or “SOMETIMES.”

[Begin each query with: “At the same sudden moment that the voices come on”]

- Sudden anxiety, fear, or panic on the inside?

- Sudden anger or rage on the inside? [ANGER QUERY]

- Sudden heart racing? Heart pounding?

- Sudden chest pain? Chest pressure?

- Sudden sweating?

- Sudden trembling or shaking?

- Sudden shortness of breath, or like you can’t catch your breath?

- Sudden choking or a lump in your throat?

- Sudden nausea or queasiness?

- Sudden dizziness, lightheadedness, or faintness?

- Sudden feeling of detachment, sort of like you are in a glass box?

- Sudden fear of losing control? Fear of going crazy?

- Sudden fear afraid of dying? Afraid of having a heart attack?

- Sudden numbness or tingling, especially in your hands or face?

- Sudden feeling of heat, or cold?

- Sudden itching in your teeth? [VALIDITY CHECK]

- Sudden fear that people want to hurt you? [EXCESS FEAR QUERY]

- Sudden voices? [VOICES QUERY]

[PAST & PRODROMAL PANIC HISTORY]

At what age did you first see a therapist or psychiatrist?

At what age were you first hospitalized for an emotional problem?

At what age did you first start hearing voices?

At what age did you first start having strong fears of other people?

Before you ever heard voices, did you ever have any of the other sudden symptoms like the ones we just talked about?

Did those episodes back then feel sort of like your voices or sudden fears do now, except that there were no voices or sudden fears of people back then?

At what age did those sudden anxiety (or panic or rage) episodes begin?

Back then, was there MORE (M) sudden anxiety, or the SAME (S) sudden anxiety, or LESS (L) sudden anxiety than with your sudden voices now?

[PAST & PRODROMAL PANIC SYMPTOMS]

Now let’s talk about some symptoms that you might have had at those same sudden anxiety moments, in the time before you ever heard any voices. So, for each sudden symptom just say “YES” or “NO” or “SOMETIMES.”

[Begin each query with: “At the same moment the sudden anxiety came on—but only during the time before you ever heard sudden voices”]

[Ask about the same 18 panic-related symptoms listed above]

[PHOBIA-RELATED PANIC AND VOICES]

Have you ever been afraid to go into a (car, bus, plane, train, subway, elevator, mall, tunnel, bridge, heights, small place, CAT scan or MRI, being alone, crowds)?

[If yes or maybe: Ask about panic symptoms in phobic situations]

Now let’s talk about some symptoms that you might have had at some of those times you were afraid. So, for each symptom just say “YES” or “NO” or “MAYBE.”

[Ask about the same 18 panic-related symptoms listed above]

At what age did you last have sudden anxiety without voices?

Has medication ever completely stopped your voices? Somewhat?

If so, did those other sudden symptoms still happen sometimes?

Thank you for your help, and for answering all of these questions!

Persecutory delusional disorder (social anxiety). Some “schizophrenia” without voices may be misdiagnosis of persecutory (paranoid) delusional disorder (PDD). Therefore, the reported population prevalence (0.02%) may be underestimated. Social anxiety is highly comorbid with “schizophrenia” (15%).16 Case reports and clinical experience suggest that PDD is commonly preceded by social anxiety.17 Some nonpsychotic social anxiety symptoms closely resemble the PDD psychotic ideas of reference (a perception that low social rank attracts critical scrutiny by authorities). Patients with PDD may remain relatively functional, with few negative symptoms, despite pronounced paranoia. Outward manifestation of paranoia may be limited, unless quite intense. The typical age of onset (40 years) is later than that of schizophrenia, and symptoms can last a long time.18

Continue to: Bipolar 1 mania with delusions...

Bipolar I mania with delusions (atypical depression). Atypical depression is the most common depression in bipolar I disorder. Often more pronounced in winter, it may intensify at any time of year. Long ago, hypersomnia, lethargy, inactivity, inoffensiveness, and craving high-calorie food may have been conducive to hibernation.

Bipolar I mania includes delusions of special accomplishments or abilities, energetically focused on a grandiose mission to help everyone. These intense symptoms may be related to reduced frontal lobe modulation. In some milder form, bipolar I mania may once have encouraged hibernation awakening. Indeed, initial bipolar I mania episodes are more common in spring, as is the spring cleaning that helps us prepare for summer.

Recognizing affective trees in a psychotic forest

Though long observed, comorbid affective symptoms have generally been considered a hodgepodge of distress caused by painful psychotic illness. But the affective symptoms precede psychosis onset, can be masked during acute psychosis, and will revert to ordinary form if psychosis abates.11-13

Rather than affective symptoms being a consequence of psychosis, it may well be the other way around. Affective disorders could be important causal and differentiating components of psychotic disorders.11-13 Research and clinical experience suggest that adjunctive treatment of the comorbidities with correct medication can greatly enhance outcome.

Diagnostic approaches

Because interviews of patients with psychosis are often complicated by confusion, irritability, paranoid evasiveness, cognitive impairment, and medication, nuanced diagnosis is difficult. Interviews should explore psychotic syndromes and subtypes that correlate with comorbidity psychoses, including pre-psychotic anxiety and depressive diagnoses that are chronic (though unlike our 4 other diagnoses, melancholic depression is not chronic).

Establishing pre-psychotic diagnosis of chronic syndromes suggests that they are still present, even if they are difficult to assess during psychosis. Re-interview after some improvement allows for a significantly better diagnosis. Just as in nonpsychotic affective disorders, multiple comorbidities are common, and can lead to a mixed psychotic diagnosis and treatment plan.1

Structured interview tools can assist diagnosis. The PaSI (Box 1,15) elicits past, present, and detailed history of DSM panic, and has been validated in a small pilot randomized controlled trial. The PaSI focuses patient attention on paroxysmal onset voices, and then evaluates the presence of concurrent DSM panic symptoms. If voices are mostly psychotic panic, they may well be a proxy for panic. Ultimately, diagnosis of 5 comorbidities and associated psychotic symptoms may allow simpler categorization into 1 (or more) of the 5 psychosis subtypes.

Continue to: Treatment by comorbidity subtype...

Treatment by comorbidity subtype

Treatment of psychosis generally begins with antipsychotics. Nominal psychotherapy (presence of a professionally detached, compassionate clinician) improves compliance and leads to supportive therapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and dialectical behavior therapy may help later, with limited interpersonal approaches further on for some patients.

The suggested approaches to pharmacotherapy noted here draw on research and clinical experience.1,14,19-21 All medications used to treat comorbidities noted here are approved or generally accepted for that diagnosis. Estimated doses are similar to those for comorbidities when patients are nonpsychotic, and vary among patients. Doses, dosing schedules, and titration are extremely important for full benefit. Always consider compliance issues, suicidality, possible adverse effects, and potential drug/drug interactions. Although the medications we suggest using to treat the comorbidities may appear to also benefit psychosis, only antipsychotics are approved for psychosis per se.

Delusional depression. Antipsychotic + antidepressant. Tricyclic antidepressants are possibly most effective, but increase the risk of overdose and dangerous falls among fragile patients. Electroconvulsive therapy is sometimes used.

Obsessive-compulsive schizophrenia. Antipsychotic + selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Consider aripiprazole (