User login

Historical Perspectives on Hair Care and Common Styling Practices in Black Women

Patients often ask dermatologists how to best care for their specific hair type; however, there are no formal recommendations that apply to the many different hair care practices utilized by Black patients, as hair types in this community can range from wavy to tightly coiled.1 Understanding the the history of hair care in those of African ancestry and various styling practices in this population is necessary to adequately counsel patients and gain trust in the doctor-patient relationship. In this article, we provide an overview of hair care recommendations based on common styling practices in Black women.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Black hair care, African American hair management, hair loss prevention, hair care practices, natural hair, natural-hair styles, alopecia, hairdressing, hair breakage, hair fragility, heat-stressed hair, traction alopecia, and natural hair care yielded 305 results; 107 duplicates were identified and removed, leaving 198 articles to be screened for eligibility (ie, English-language studies created in the past 15 years). Sixty-eight full-text articles were screened against the exclusion criteria, which included case reports and case series, articles not focused on Afro-textured hair, and cancer-related hair loss. Three additional fulltext articles were identified via resources from Wayne State University library (Detroit, Michigan) that were not available on PubMed. A total of 29 full-text articles were included in our review.

Background on Hair Care and Styling in African Populations

It is difficult to understand the history of hair in those of African ancestry in the United States.2 Prior to slavery, hair styling was considered a way of identification, classification, and communication as well as a medium through which to connect with the spiritual world in many parts of Africa. Hair-styling practices in Africa included elaborate cornrows, threading, and braiding with many accessories. Notable hair-styling products included natural butters, herbs, and powders to assist with moisture retention. Scarves also were used during this time for ceremonies or protection.3 During the mass enslavement of African populations and their transportation to the Americas by Europeans, slaveholders routinely cut off all the hair of both men and women in order to objectify and erase the culture of African hair styling passed down through generations.4,5 Hair texture then was weaponized to create a caste system in plantation life, in which Black slaves with straight hair textures were granted the “privilege” of domestic work, while those with kinky hair were relegated to arduous manual labor in the fields.4 Years later, during the 1800s, laws were enacted in the United States to prohibit Black women from wearing tightly coiled natural hair in public places.5 Over the next few centuries from the 1800s to the early 2000s, various hair-styling trends such as the use of hot combs, perms, afros, and Jheri curls developed as a means for Black individuals to conform to societal pressure to adopt more European features; however, as time progressed, afros, braids, locs, and natural hair would become more dominant as statements against these same societal pressures.5

The natural hair movement, which emerged in the United States in the 2000s, encouraged Black women to abandon the use of toxic chemical hair straighteners, cultivate healthier hair care practices, disrupt Eurocentric standards of wearing straightened hair, and facilitate self-definition of beauty ideals from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.4,5 It is estimated that between 30% and 70% of all Black women in the United States wear natural hair, including 79% of millennial Black women younger than 30 years6; however, several new trends such as wigs and weaves have grown in popularity since the early 2000s due to mainstream pop culture and improvements in creating natural hairlines.7,8

Key Features of Afro-Textured Hair

Individuals of African descent have the most diverse hair texture phenotypes, ranging from straight to tightly coiled.9 Although hair is chemically similar across various racial groups, differences are noted mainly in the shape of the hair shaft, with elliptical and curved shapes seen in Afrotextured hair. These differences yield more tightly curled strands than in other hair types; however, these features also contribute to fragility, as it creates points of weakness and decreases the tensile strength of the hair shaft.10 This inherent fragility leads to higher rates of hair breakage as well as lower moisture content and slower growth rates, which is why Afro-textured hair requires special care.9

Afro-textured hair generally falls into 2 main categories of the Andre Walker hair typing system: 4A-4C and 3A-3C.11 In the 4A-4C category, hair is described as coily or kinky. Common concerns related to this hair type include dryness and brittleness with increased susceptibility to breakage. The 3A-3C category is described as loose to corkscrew curls, with a common concern of dryness.11,12 Additionally, Loussouarn et al13 established a method to further define natural hair curliness using curve diameter and curl meters on glass plates to measure the curvature of hair strands. This method allows for assessing diversity and range of curliness within various races without relying on ethnic origin.13

Common Hair Care Practices

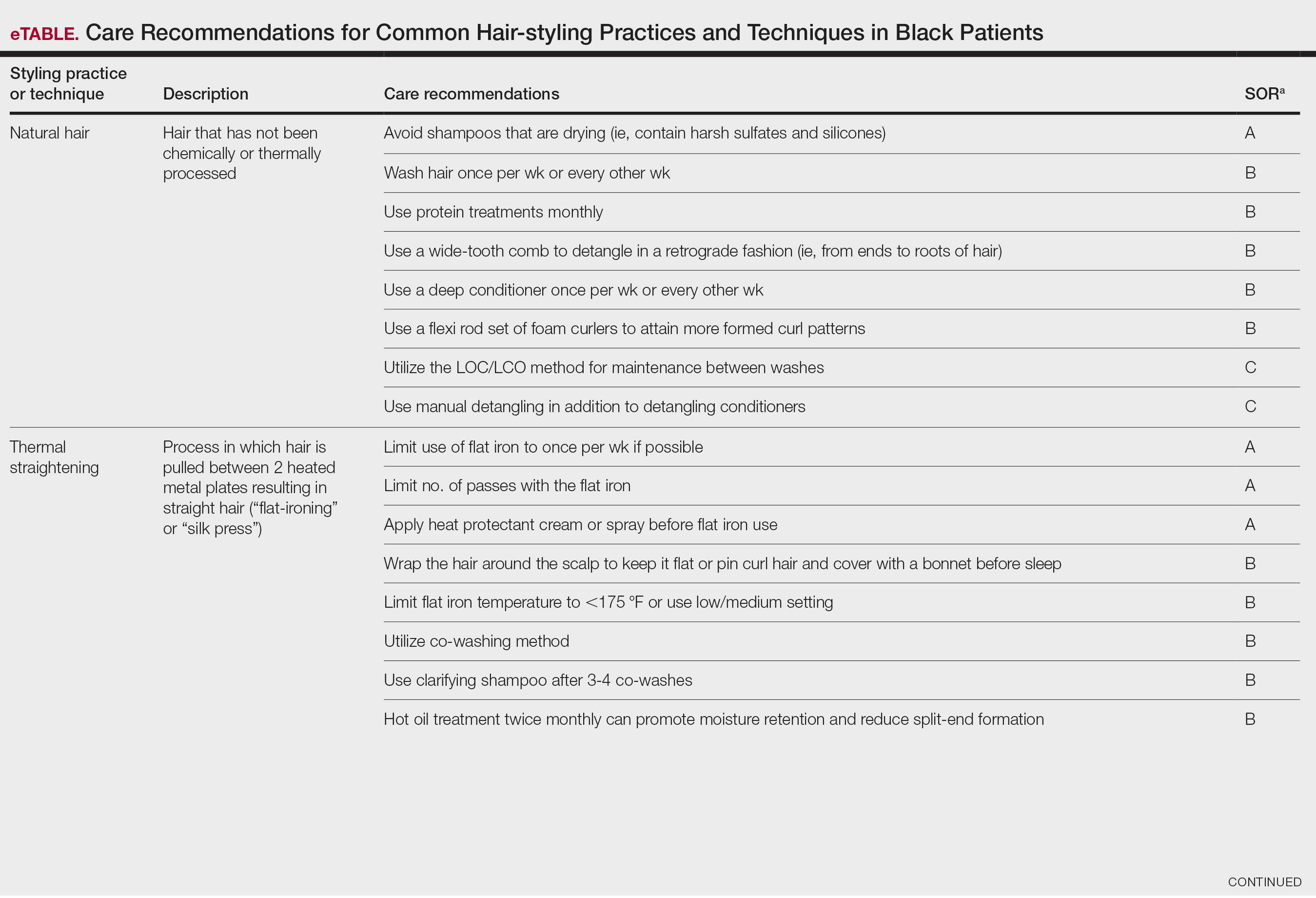

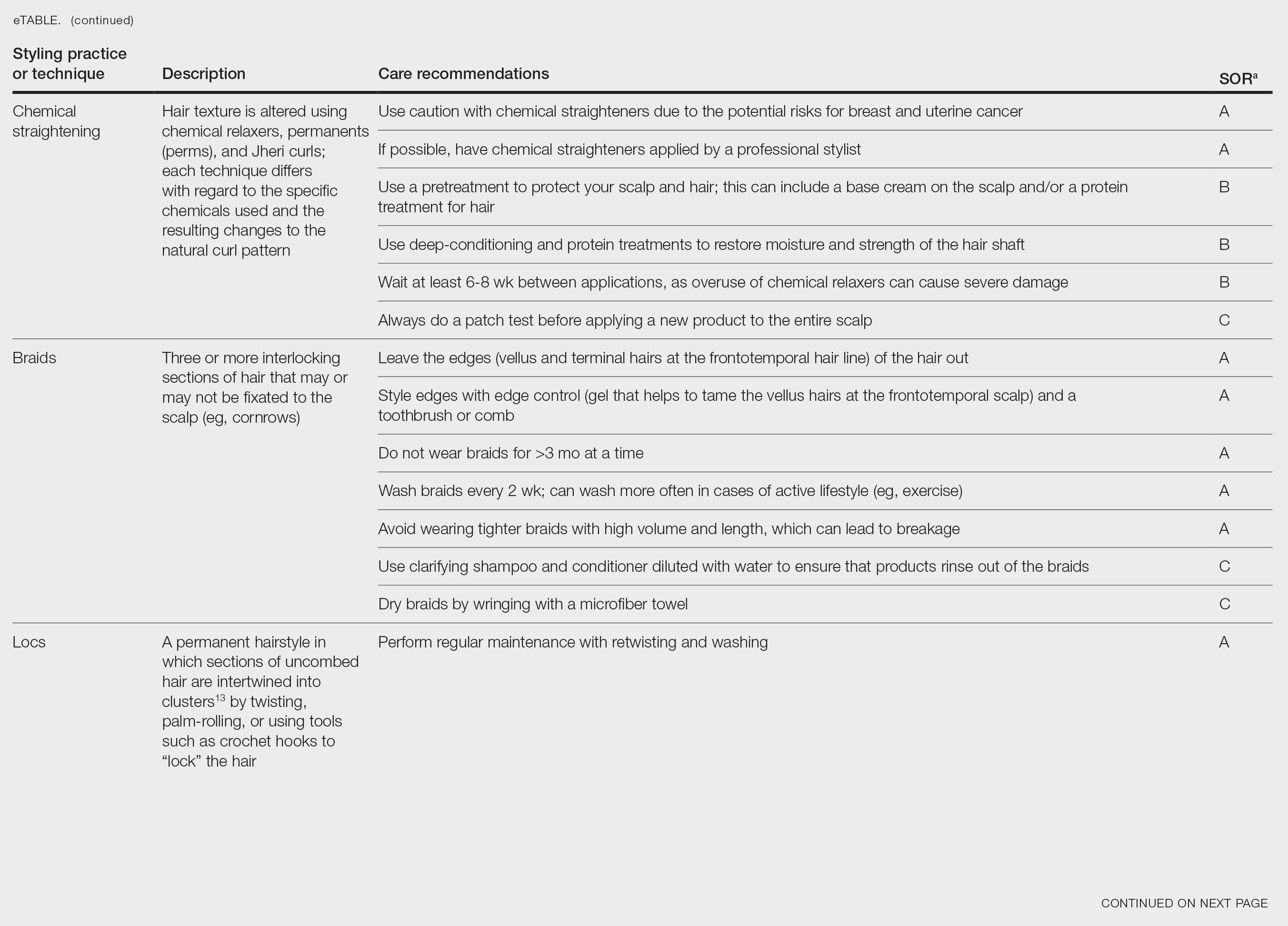

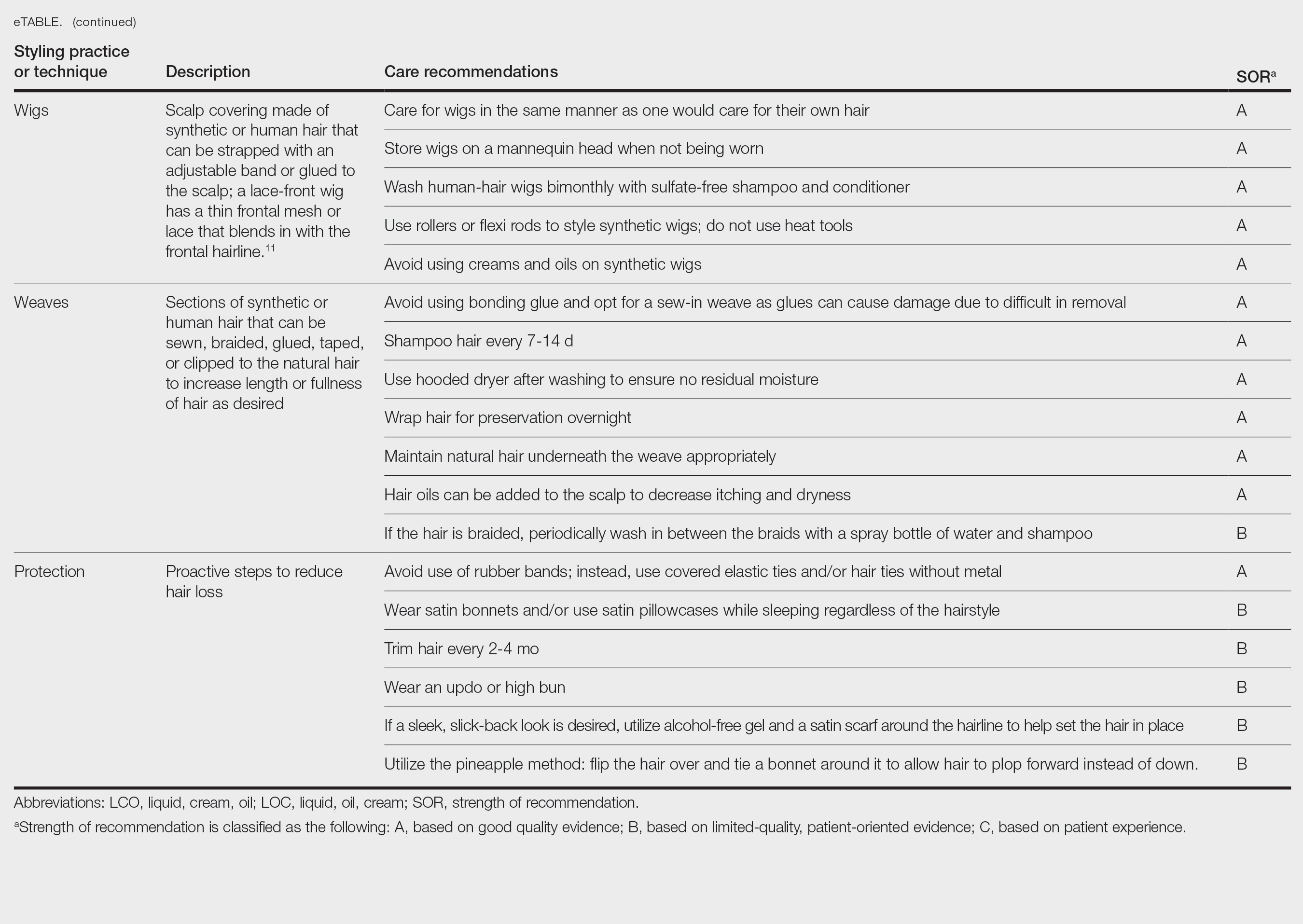

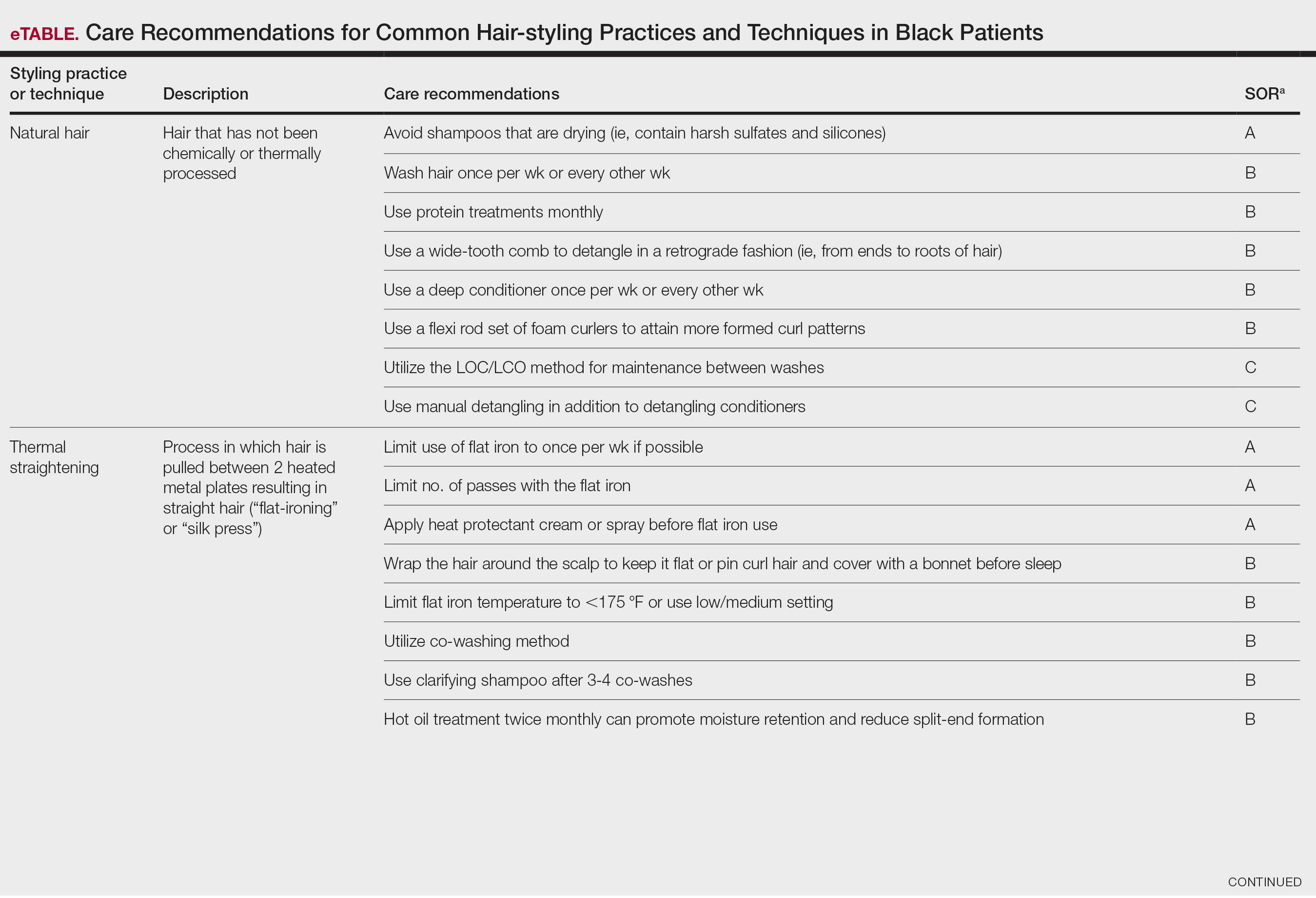

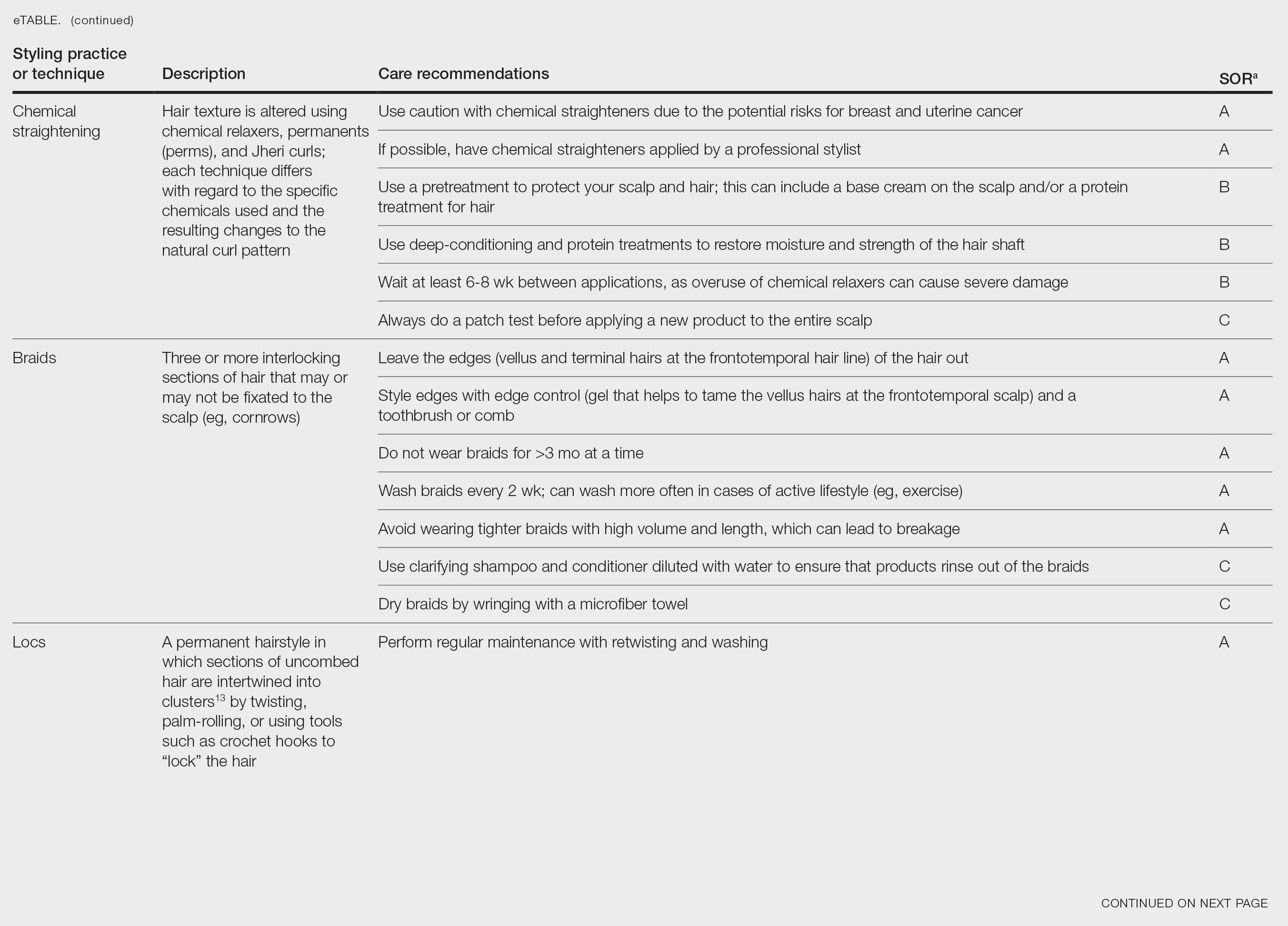

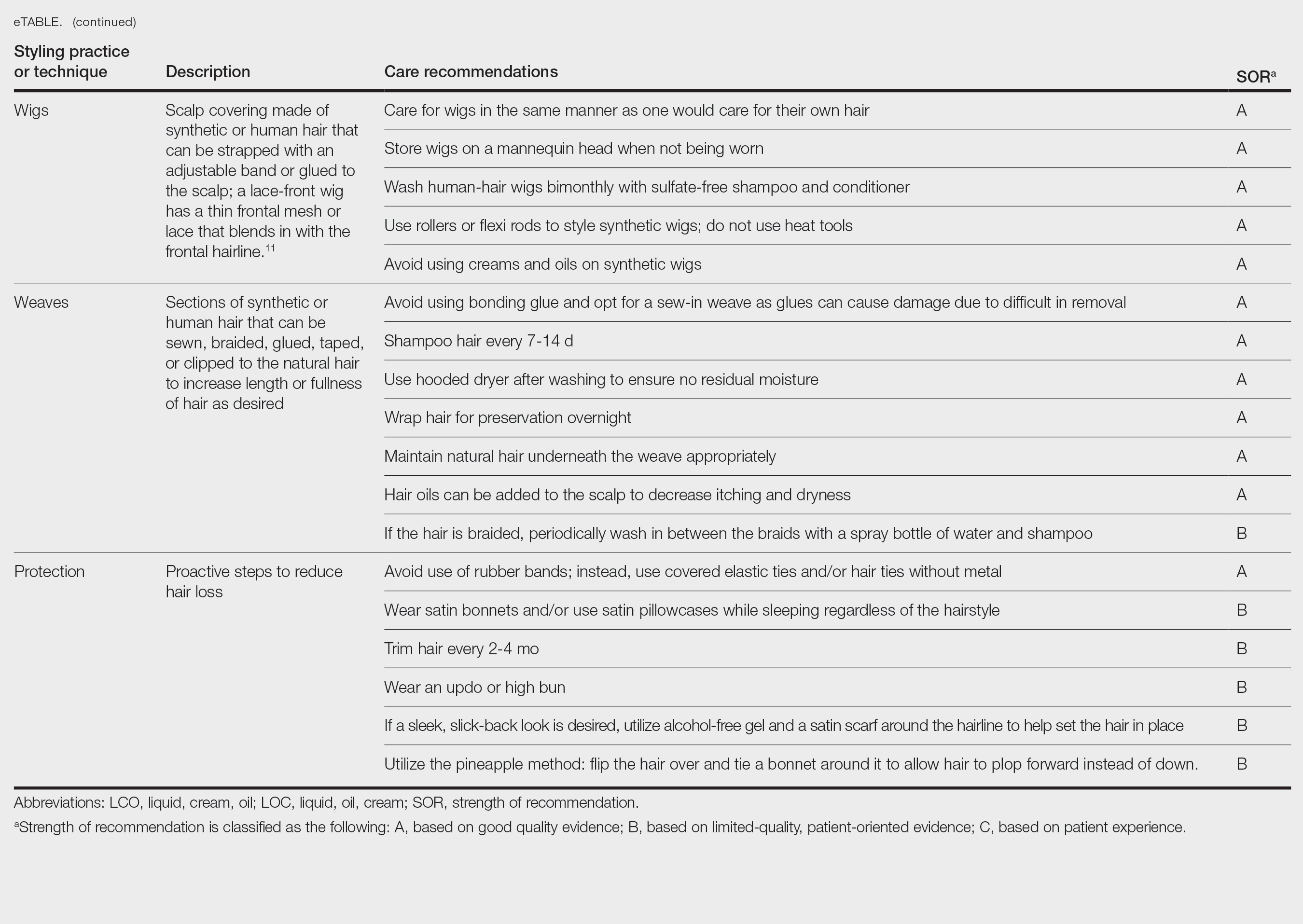

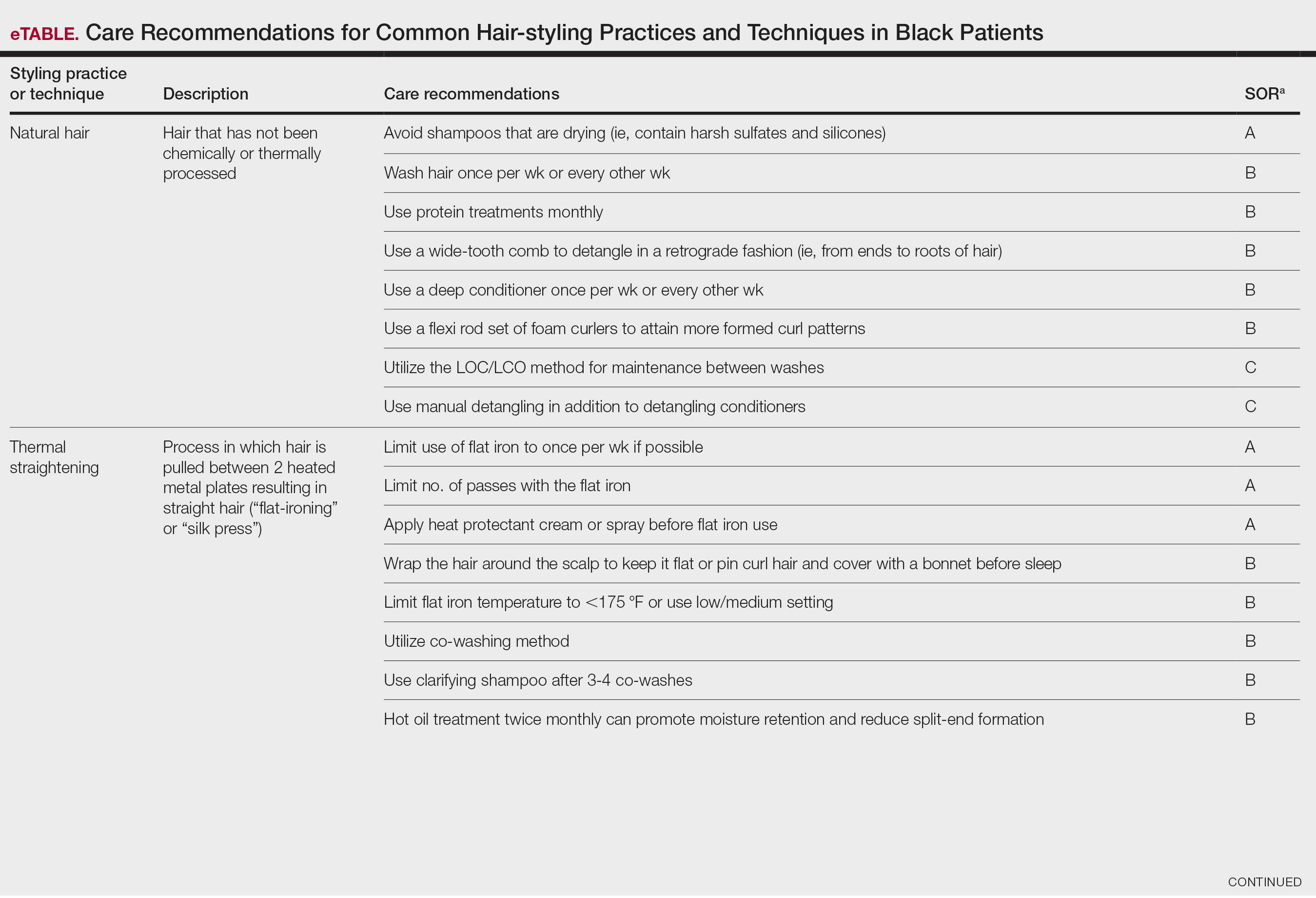

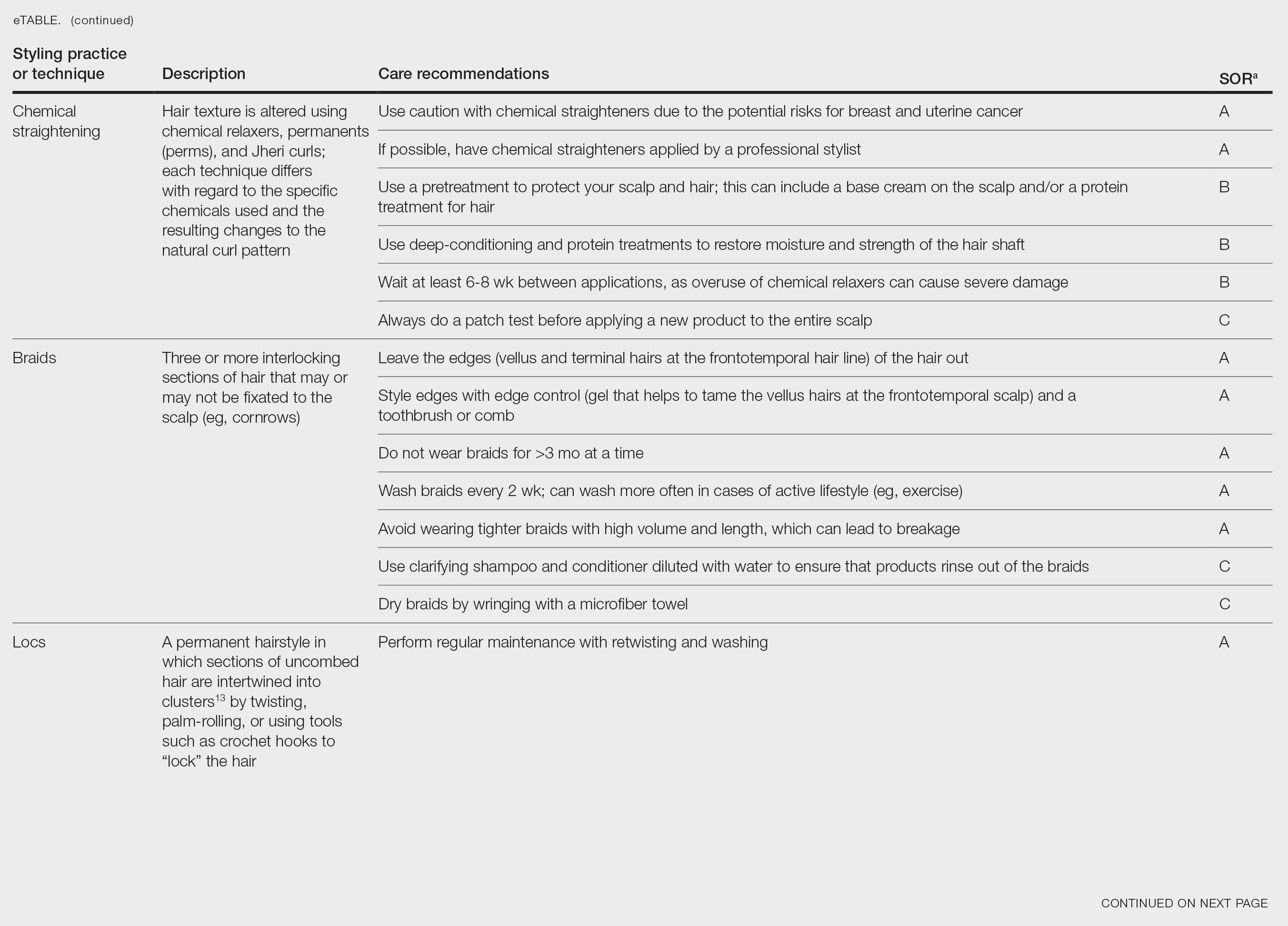

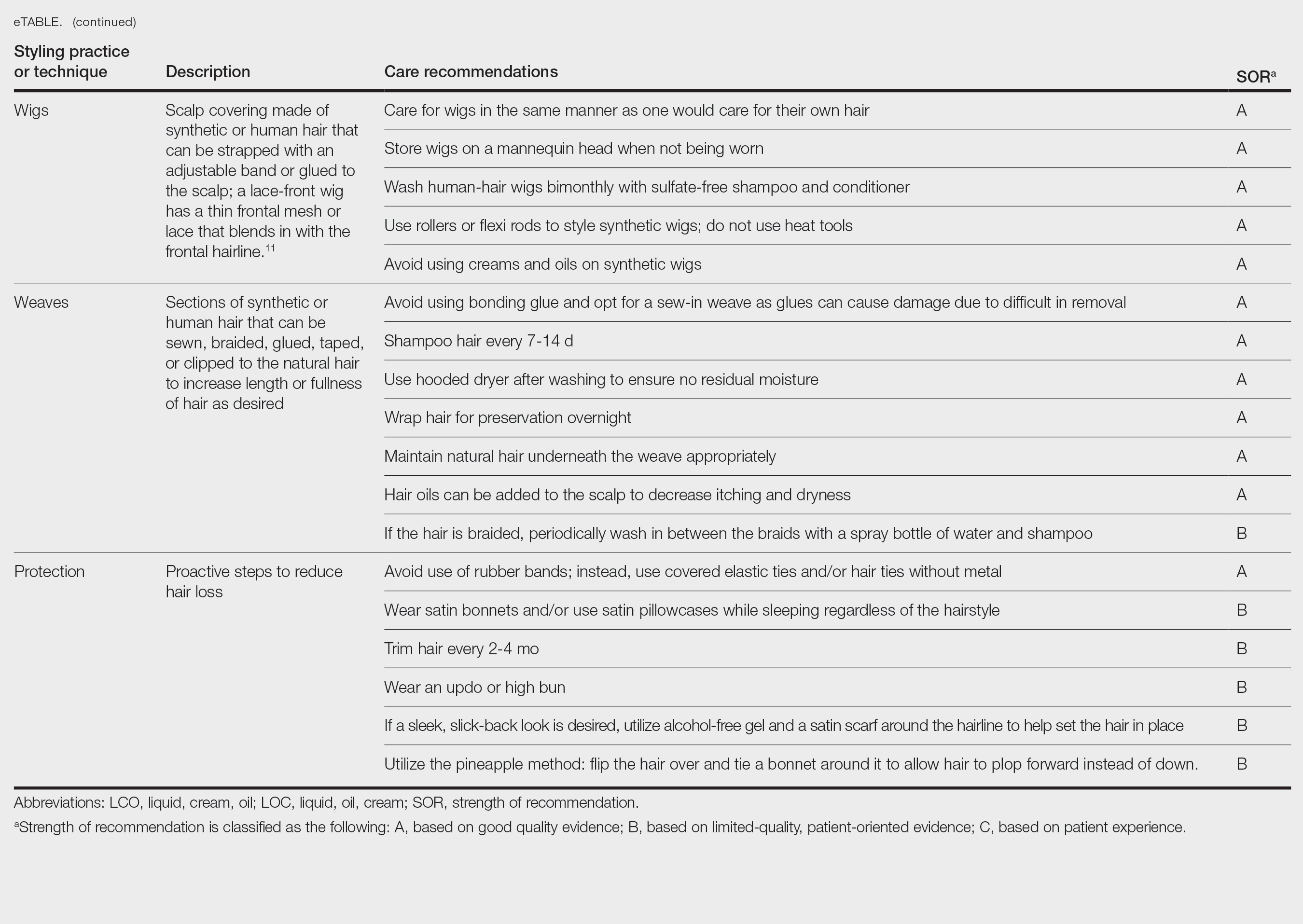

A description of each hair type and recommended styling practices with their levels of evidence can be found in the eTable.

Natural Hair—Natural hair is classified as hair that has not been chemically changed by perms, heat, or other straightening treatments.12,14 For natural hair, retaining the moisture of the hair shaft should be the main focus, as moisture loss leads to considerable dryness.14 Generally, it is recommended to wash natural hair once per week or every other week; however, this can change based on hair length and oil production on the scalp. Washing daily may be ideal for shorter hair and monthly for longer hair to help prevent product build-up that can have a drying effect.15 Avoid shampoos that are drying (eg, sulfate and silicone products). The co-washing method also can be utilized, which entails washing the hair with a conditioning cleanser instead of shampoo and conditioner. However, this technique is not meant to completely replace shampoo.16 In fact, a clarifying shampoo is recommended after co-washing 3 or 4 times.16 The use of a hot oil treatment twice per month can promote moisture retention and reduce split-end formation.17 For maintenance between washes, many utilize the liquid, oil, cream (LOC) or liquid, cream, oil (LCO) methods, which describe regimens that utilize water, an oil of choice, and cream such as shea butter to lock in moisture.18 This method can be used as often as needed for dry hair.

Due to the susceptibility of Afro-textured hair to tangle and knot, using a wide-tooth comb, detangling brush, or detangling conditioners is a grade B recommendation for care (eTable). Though not widely documented in the literature, many of our patients have had anecdotal success detangling their hair simply by pulling hair strands apart by hand or “finger detangling” as well as using wide-tooth combs. Although both hair types are healthier in their natural states, kinky hair (type 4A-4C) is extremely fragile and more difficult to manage than less kinky hair (type 3A-3C).18

Special care is needed when detangling due to strands being weaker when wet.19 Detangling should be performed in a retrograde fashion. Deep conditioning can aid in moisture retention and should be performed weekly or biweekly.17-20 Depending on the health of the hair, protein treatments can be considered on a monthly basis to help preserve the cuticle. Styling with braids, twists, or other protective styles can then be completed on an individual basis.

Thermal Straightening—A blowout involves straightening the hair after a wash with the use of a hair dryer.21 This common hair-styling method does not employ the use of chemicals beyond light hair oils and heat-protectant creams or sprays, typically resulting in a less kinky afro or semi-straight hair. Thermal straightening utilizes heat to temporarily straighten hair strands. Flat irons with heated metal plates then can be used after blow-drying the hair to fully straighten and smooth the strands. These processes combined commonly are known as a silk press.21-22

For thermally straightened hair, it is recommended to either wrap the hair around the scalp to keep it flat or pin curl the hair and cover with a bonnet to sleep. Safe straightening techniques with the use of a flat iron include setting the temperature no higher than 175 °F or a low/medium setting while also limiting use to once per week if possible.23 The number of passes of the flat iron also should be limited to 1 to 2 to reduce breakage. A heat-protectant cream or spray also can be applied to the hair before flat ironing to minimize damage. Applying heat protectant to the hair prior to styling will help minimize heat damage by distributing the heat along the hair fiber surface, avoiding water boiling in the hair shaft and the development of bubble hair leading to damage.24

Chemical Straightening—Similar to how relaxers, perms, and Jheri curl treatments chemically modify hair texture using distinct chemicals yielding different curl patterns, the Brazilian blowout similarly straightens hair using a hair dryer and chemicals applied to hair strands after washing.21-24 Relaxers utilize sodium or guanidine hydroxide for straightening, perms use ammonium thioglycolate for curling, and Jheri curl treatments employ thioglycolates or mercaptans for defined curls. However, these treatments generally are cautioned against due to potential hair damage and recent associations with uterine and breast cancer in Black women. Research has suggested that endocrine disrupters in these products, especially those marketed to Black women, contribute to hormone-related disease processes.25,26 One study found higher concentrations of alkylphenols, the fragrance marker diethyl phthalate, and parabens in relaxers27; however, more research is needed to determine specific chemicals associated with these cancers.

Braids and Locs—Braiding is a technique that involves interlocking 3 or more sections of hair that may or may not be fixated to the scalp like a cornrow,11 and one can utilize extensions or natural hair depending on the desired outcome. Intended for long-term wear (ie, weeks to months), braids minimize breakage and reduce daily styling needs. Two popular styles—cornrows and individual braids—differ in preparation and weaving techniques. Cornrows are an Afro-centric style involving uniform, tightly woven braids that are close to the scalp, creating distinct patterns. Conversely, individual braids weave separate hair sections, offering diverse styling possibilities. Braiding practices should exclude hairline edges—often termed baby hairs—to prevent traction alopecia. Minimal use of edge gel, which helps to tame the vellus hairs at the frontotemporal scalp, as well as mindful weave volume, weight, and length are recommended to avert breakage. Braids that cause pain are too tight, can damage hair, and may cause traction alopecia.11 Braids should not be worn for longer than 3 months at a time and require biweekly washing with diluted shampoo and conditioner. Proper drying by wringing the hair with a microfiber towel is essential to avoid frizz and mold formation.

Locs are a low-maintenance hairstyle considered permanent until cut.28 This style involves twisting, palm rolling, or using tools such as crochet hooks to “lock” the hair. Regular maintenance with retwisting and cleaning is vital for loc health. Increased weight and tight twisting of locs can cause damage to the scalp and hair strands; however, locs are known to increase hair volume over time, often due to the accumulation of hairs that would otherwise have been shed in the telogen phase.28

Wigs and Weaves—Wigs consist of synthetic or human hair that can be strapped to the head with an adjustable band or glued to the scalp depending on the desired style.29 Wigs are removed daily, which allows for quick access to hair for cleansing and moisturizing. In contrast, weaves typically are sewn into the natural hair, which may make it difficult to reach the scalp for cleansing, leading to dryness and product build-up.29 Notably, there is evidence of a relationship between long-term use of weaves and traction alopecia.30

Wigs can have a fully synthetic hair line or lace hair line and can range from very affordable to expensive. When applied correctly, both styles offer an easy way to cover and protect the natural hair by reducing the amount of physical trauma related to daily hair styling. A lace-front wig contains a frontal thin mesh or lace that camouflages the natural frontal hairline.29,30 A risk of lace-front wigs is that they can cause friction alopecia secondary to repeated use of adhesives and repeated friction against the hairline. Generally, wigs and weaves should be cared for as one would care for one’s own hair.

Hair Care in Black Children—Children’s hair care begins with washing the hair and scalp with shampoo, applying conditioner, and detangling as needed.31 After rinsing out the conditioner, a leave-in conditioner can assist with moisture retention and further detangling. The hair is then styled, either wet or dry. Recommendations for hair care practices in Black children include loose hairstyles that do not strain hair roots and nightly removal of root-securing accessories (eg, barrettes, elastic hairbeads). Frequent cornrow styling and friction on chemically straightened hair were identified by a survey as considerable traction alopecia risk factors.32 Thus, educating caregivers on appropriate hair-grooming practices for children is important.

Hair Protection—Proactive steps to reduce hair loss include wearing satin bonnets and/or using satin pillowcases while sleeping regardless of hairstyle. Although evidence is limited, it is thought that satin and silk allow the hair to retain its moisture and natural oils, preventing breakage and friction.33,34 Frequent hair trimming every 2 to 4 months can reduce breakage when doing thermal treatments.35,36 When prolonged or repetitive styles are used, it is encouraged to give the hair a break between styles to recover from the repeated stress. Wearing an intermittent updo or high bun—a hairstyle in which the hair is pulled upward—can prevent breakage by reducing heavy strain on the hair; however, it is important to avoid the use of rubber bands due to friction and risk for tangling of hair strands. Instead, the use of covered elastic ties and/or those without metal is preferred.11 Alternatively, if a polished and neat appearance with slicked-back hair is desired, the practice of tautly pulling the hair is not recommended. Instead, use of an alcohol-free gel is suggested along with a satin scarf wrapped around the hairline to facilitate the setting of the hair in place.11

A common practice to preserve curly hairstyles while sleeping is known as the pineapple method, which protects the hair and aids in preserving the freshness and style of the curls.37 It consists of a loosely tied high ponytail at the top of the head allowing the curls to fall forward. This minimizes frizz and prevents the curls from forming knots.

Conclusion

Hair care recommendations in Black women can be complex due to a wide range of personal care preferences and styling techniques in this population. While evidence in the literature is limited, it still is important for dermatologists to be familiar with the different hair care practices utilized by Black women so they can effectively counsel patients and improve hair health. Knowledge of optimal hair care practices can aid in the prevention of common hair disorders that disproportionately affect this patient population, such as traction alopecia and trichorrhexis nodosa or breakage.

- Hall RR, Francis S, Whitt-Glover M, et al. Hair care practices as a barrier to physical activity in African American women. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:310-314. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.1946

- Johnson T, Bankhead T. Hair it is: examining the experiences of Black women with natural hair. Open J Soc Sci. 2014;02:86-100. doi:10.4236/jss.2014.21010

- Byrd AD, Tharps LL. Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America. 2nd ed. St Martin’s Griffin; 2014.

- Mbilishaka AM, Clemons K, Hudlin M, et al. Don’t get it twisted: untangling the psychology of hair discrimination within Black communities. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2020;90:590-599. doi:10.1037 /ort0000468

- Khumalo NP. On the history of African hair care: more treasures await discovery. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;7:231. doi:10.1111/j.1473- 2165.2008.00396.x

- Johnson AM, Godsil RD, MacFarlane J, et al. The “good hair” study: explicit and implicit attitudes toward Black women’s hair. Perception Institute. February 2017. Accessed February 11, 2025. https://perception.org/publications/goodhairstudy/

- Haskin A, Aguh C. All hairstyles are not created equal: what the dermatologist needs to know about black hairstyling practices and the risk of traction alopecia (TA). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:606-611. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1162

- Roseborough IE, McMichael AJ. Hair care practices in African- American patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:103-108. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2009.04.007

- Menkart J Wolfram LJ Mao I. Caucasian hair, Negro hair and wool: similarities and differences. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1996;17:769-787.

- Crawford K, Hernandez C. A review of hair care products for black individuals. Cutis. 2014;93:289-293.

- Mayo TT, Callender VD. The art of prevention: it’s too tight-loosen up and let your hair down. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:174-179. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.019

- De Sá Dias TC, Baby AR, Kaneko TM, et al. Relaxing/straightening of Afro-ethnic hair: historical overview. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:2-5. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00294.x

- Loussouarn G, Garcel AL, Lozano I, et al. Worldwide diversity of hair curliness: a new method of assessment. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46 (suppl 1):2-6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03453.x

- Barba C, Mendez S, Marti M, et al. Water content of hair and nails. Thermochimica Acta. 2009;494:136-140. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2009.05.005

- Gray J. Hair care and hair care products. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:227-236. doi:10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00133-4

- Gavazzoni Dias MFR. Pro and contra of cleansing conditioners. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:131-134. doi:10.1159/000493588

- Gavazzoni Dias MFR. Hair cosmetics: an overview. Int J Trichology. 2015;7:2-15. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.153450

- Beal AC, Villarosa L, Abner A. The Black Parenting Book. 1999.

- Davis-Sivasothy A. The Science of Black Hair: A Comprehensive Guide to Textured Care. Saga Publishing; 2011.

- Robbins CR. The Physical Properties and Cosmetic Behavior of Hair. In: Robbins CR. Chemical and Physical Behavior of Human Hair. 3rd ed. Springer Nature; 1994:299-370. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-3898-8_8

- Weathersby C, McMichael A. Brazilian keratin hair treatment: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:144-148. doi:10.1111/jocd.12030

- Barreto T, Weffort F, Frattini S, et al. Straight to the point: what do we know so far on hair straightening? Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:265-271. doi:10.1159/000514367

- Dussaud A, Rana B, Lam HT. Progressive hair straightening using an automated flat iron: function of silicones. J Cosmet Sci. 2013;64:119-131.

- Zhou Y, Rigoletto R, Koelmel D, et al. The effect of various cosmetic pretreatments on protecting hair from thermal damage by hot flat ironing. J Cosmet Sci. 2011;62:265-282.

- Chang CJ, O’Brien KM, Keil AP, et al. Use of straighteners and other hair products and incident uterine cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114:1636-1645. doi:10.1093/jnci/djac165

- White AJ, Gregoire AM, Taylor KW, et al. Adolescent use of hair dyes, straighteners and perms in relation to breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:2255-2263. doi:10.1002/ijc.33413

- Helm JS, Nishioka M, Brody JG, et al. Measurement of endocrine disrupting and asthma-associated chemicals in hair products used by Black women. Environ Res. 2018;165:448-458.

- Asbeck S, Riley-Prescott C, Glaser E, et al. Afro-ethnic hairstyling trends, risks, and recommendations. Cosmetics. 2022;9:17. doi:10.3390 /cosmetics9010017

- Saed S, Ibrahim O, Bergfeld WF. Hair camouflage: a comprehensive review. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2016;2:122-127. doi:10.1016 /j.ijwd.2016.09.002

- Billero V, Miteva M. Traction alopecia: the root of the problem. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:149-159. doi:10.2147/CCID .S137296

- Jones NL, Heath CR. Hair at the intersection of dermatology and anthropology: a conversation on race and relationships. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38(suppl 2):158-160. doi:10.1111/pde.14721

- Rucker Wright D, Gathers R, Kapke A, et al. Hair care practices and their association with scalp and hair disorders in African American girls. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:253-262. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.037

- Carefoot H. Silk pillowcases for better hair and skin: what to know. The Washington Post. April 6, 2021. Accessed February 10, 2025. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/wellness/silk-pillowcases-hair-skin-benefits-myths/2021/04/05/a7dcad7c-866a-11eb-82bc-e58213caa38e_story.html

- Samrao A, McMichael A, Mirmirani P. Nocturnal traction: techniques used for hair style maintenance while sleeping may be a risk factor for traction alopecia. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:220-223. doi:10.1159/000513088

- Callender VD, McMichael AJ, Cohen GF. Medical and surgical therapies for alopecias in black women. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:164-176. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04017.x

- McMichael AJ. Hair breakage in normal and weathered hair: focus on the Black patient. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2007;12:6-9. doi:10.1038/sj.jidsymp.5650047

- Bosley RE, Daveluy S. A primer to natural hair care practices in black patients. Cutis. 2015;95:78-80,106.

Patients often ask dermatologists how to best care for their specific hair type; however, there are no formal recommendations that apply to the many different hair care practices utilized by Black patients, as hair types in this community can range from wavy to tightly coiled.1 Understanding the the history of hair care in those of African ancestry and various styling practices in this population is necessary to adequately counsel patients and gain trust in the doctor-patient relationship. In this article, we provide an overview of hair care recommendations based on common styling practices in Black women.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Black hair care, African American hair management, hair loss prevention, hair care practices, natural hair, natural-hair styles, alopecia, hairdressing, hair breakage, hair fragility, heat-stressed hair, traction alopecia, and natural hair care yielded 305 results; 107 duplicates were identified and removed, leaving 198 articles to be screened for eligibility (ie, English-language studies created in the past 15 years). Sixty-eight full-text articles were screened against the exclusion criteria, which included case reports and case series, articles not focused on Afro-textured hair, and cancer-related hair loss. Three additional fulltext articles were identified via resources from Wayne State University library (Detroit, Michigan) that were not available on PubMed. A total of 29 full-text articles were included in our review.

Background on Hair Care and Styling in African Populations

It is difficult to understand the history of hair in those of African ancestry in the United States.2 Prior to slavery, hair styling was considered a way of identification, classification, and communication as well as a medium through which to connect with the spiritual world in many parts of Africa. Hair-styling practices in Africa included elaborate cornrows, threading, and braiding with many accessories. Notable hair-styling products included natural butters, herbs, and powders to assist with moisture retention. Scarves also were used during this time for ceremonies or protection.3 During the mass enslavement of African populations and their transportation to the Americas by Europeans, slaveholders routinely cut off all the hair of both men and women in order to objectify and erase the culture of African hair styling passed down through generations.4,5 Hair texture then was weaponized to create a caste system in plantation life, in which Black slaves with straight hair textures were granted the “privilege” of domestic work, while those with kinky hair were relegated to arduous manual labor in the fields.4 Years later, during the 1800s, laws were enacted in the United States to prohibit Black women from wearing tightly coiled natural hair in public places.5 Over the next few centuries from the 1800s to the early 2000s, various hair-styling trends such as the use of hot combs, perms, afros, and Jheri curls developed as a means for Black individuals to conform to societal pressure to adopt more European features; however, as time progressed, afros, braids, locs, and natural hair would become more dominant as statements against these same societal pressures.5

The natural hair movement, which emerged in the United States in the 2000s, encouraged Black women to abandon the use of toxic chemical hair straighteners, cultivate healthier hair care practices, disrupt Eurocentric standards of wearing straightened hair, and facilitate self-definition of beauty ideals from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.4,5 It is estimated that between 30% and 70% of all Black women in the United States wear natural hair, including 79% of millennial Black women younger than 30 years6; however, several new trends such as wigs and weaves have grown in popularity since the early 2000s due to mainstream pop culture and improvements in creating natural hairlines.7,8

Key Features of Afro-Textured Hair

Individuals of African descent have the most diverse hair texture phenotypes, ranging from straight to tightly coiled.9 Although hair is chemically similar across various racial groups, differences are noted mainly in the shape of the hair shaft, with elliptical and curved shapes seen in Afrotextured hair. These differences yield more tightly curled strands than in other hair types; however, these features also contribute to fragility, as it creates points of weakness and decreases the tensile strength of the hair shaft.10 This inherent fragility leads to higher rates of hair breakage as well as lower moisture content and slower growth rates, which is why Afro-textured hair requires special care.9

Afro-textured hair generally falls into 2 main categories of the Andre Walker hair typing system: 4A-4C and 3A-3C.11 In the 4A-4C category, hair is described as coily or kinky. Common concerns related to this hair type include dryness and brittleness with increased susceptibility to breakage. The 3A-3C category is described as loose to corkscrew curls, with a common concern of dryness.11,12 Additionally, Loussouarn et al13 established a method to further define natural hair curliness using curve diameter and curl meters on glass plates to measure the curvature of hair strands. This method allows for assessing diversity and range of curliness within various races without relying on ethnic origin.13

Common Hair Care Practices

A description of each hair type and recommended styling practices with their levels of evidence can be found in the eTable.

Natural Hair—Natural hair is classified as hair that has not been chemically changed by perms, heat, or other straightening treatments.12,14 For natural hair, retaining the moisture of the hair shaft should be the main focus, as moisture loss leads to considerable dryness.14 Generally, it is recommended to wash natural hair once per week or every other week; however, this can change based on hair length and oil production on the scalp. Washing daily may be ideal for shorter hair and monthly for longer hair to help prevent product build-up that can have a drying effect.15 Avoid shampoos that are drying (eg, sulfate and silicone products). The co-washing method also can be utilized, which entails washing the hair with a conditioning cleanser instead of shampoo and conditioner. However, this technique is not meant to completely replace shampoo.16 In fact, a clarifying shampoo is recommended after co-washing 3 or 4 times.16 The use of a hot oil treatment twice per month can promote moisture retention and reduce split-end formation.17 For maintenance between washes, many utilize the liquid, oil, cream (LOC) or liquid, cream, oil (LCO) methods, which describe regimens that utilize water, an oil of choice, and cream such as shea butter to lock in moisture.18 This method can be used as often as needed for dry hair.

Due to the susceptibility of Afro-textured hair to tangle and knot, using a wide-tooth comb, detangling brush, or detangling conditioners is a grade B recommendation for care (eTable). Though not widely documented in the literature, many of our patients have had anecdotal success detangling their hair simply by pulling hair strands apart by hand or “finger detangling” as well as using wide-tooth combs. Although both hair types are healthier in their natural states, kinky hair (type 4A-4C) is extremely fragile and more difficult to manage than less kinky hair (type 3A-3C).18

Special care is needed when detangling due to strands being weaker when wet.19 Detangling should be performed in a retrograde fashion. Deep conditioning can aid in moisture retention and should be performed weekly or biweekly.17-20 Depending on the health of the hair, protein treatments can be considered on a monthly basis to help preserve the cuticle. Styling with braids, twists, or other protective styles can then be completed on an individual basis.

Thermal Straightening—A blowout involves straightening the hair after a wash with the use of a hair dryer.21 This common hair-styling method does not employ the use of chemicals beyond light hair oils and heat-protectant creams or sprays, typically resulting in a less kinky afro or semi-straight hair. Thermal straightening utilizes heat to temporarily straighten hair strands. Flat irons with heated metal plates then can be used after blow-drying the hair to fully straighten and smooth the strands. These processes combined commonly are known as a silk press.21-22

For thermally straightened hair, it is recommended to either wrap the hair around the scalp to keep it flat or pin curl the hair and cover with a bonnet to sleep. Safe straightening techniques with the use of a flat iron include setting the temperature no higher than 175 °F or a low/medium setting while also limiting use to once per week if possible.23 The number of passes of the flat iron also should be limited to 1 to 2 to reduce breakage. A heat-protectant cream or spray also can be applied to the hair before flat ironing to minimize damage. Applying heat protectant to the hair prior to styling will help minimize heat damage by distributing the heat along the hair fiber surface, avoiding water boiling in the hair shaft and the development of bubble hair leading to damage.24

Chemical Straightening—Similar to how relaxers, perms, and Jheri curl treatments chemically modify hair texture using distinct chemicals yielding different curl patterns, the Brazilian blowout similarly straightens hair using a hair dryer and chemicals applied to hair strands after washing.21-24 Relaxers utilize sodium or guanidine hydroxide for straightening, perms use ammonium thioglycolate for curling, and Jheri curl treatments employ thioglycolates or mercaptans for defined curls. However, these treatments generally are cautioned against due to potential hair damage and recent associations with uterine and breast cancer in Black women. Research has suggested that endocrine disrupters in these products, especially those marketed to Black women, contribute to hormone-related disease processes.25,26 One study found higher concentrations of alkylphenols, the fragrance marker diethyl phthalate, and parabens in relaxers27; however, more research is needed to determine specific chemicals associated with these cancers.

Braids and Locs—Braiding is a technique that involves interlocking 3 or more sections of hair that may or may not be fixated to the scalp like a cornrow,11 and one can utilize extensions or natural hair depending on the desired outcome. Intended for long-term wear (ie, weeks to months), braids minimize breakage and reduce daily styling needs. Two popular styles—cornrows and individual braids—differ in preparation and weaving techniques. Cornrows are an Afro-centric style involving uniform, tightly woven braids that are close to the scalp, creating distinct patterns. Conversely, individual braids weave separate hair sections, offering diverse styling possibilities. Braiding practices should exclude hairline edges—often termed baby hairs—to prevent traction alopecia. Minimal use of edge gel, which helps to tame the vellus hairs at the frontotemporal scalp, as well as mindful weave volume, weight, and length are recommended to avert breakage. Braids that cause pain are too tight, can damage hair, and may cause traction alopecia.11 Braids should not be worn for longer than 3 months at a time and require biweekly washing with diluted shampoo and conditioner. Proper drying by wringing the hair with a microfiber towel is essential to avoid frizz and mold formation.

Locs are a low-maintenance hairstyle considered permanent until cut.28 This style involves twisting, palm rolling, or using tools such as crochet hooks to “lock” the hair. Regular maintenance with retwisting and cleaning is vital for loc health. Increased weight and tight twisting of locs can cause damage to the scalp and hair strands; however, locs are known to increase hair volume over time, often due to the accumulation of hairs that would otherwise have been shed in the telogen phase.28

Wigs and Weaves—Wigs consist of synthetic or human hair that can be strapped to the head with an adjustable band or glued to the scalp depending on the desired style.29 Wigs are removed daily, which allows for quick access to hair for cleansing and moisturizing. In contrast, weaves typically are sewn into the natural hair, which may make it difficult to reach the scalp for cleansing, leading to dryness and product build-up.29 Notably, there is evidence of a relationship between long-term use of weaves and traction alopecia.30

Wigs can have a fully synthetic hair line or lace hair line and can range from very affordable to expensive. When applied correctly, both styles offer an easy way to cover and protect the natural hair by reducing the amount of physical trauma related to daily hair styling. A lace-front wig contains a frontal thin mesh or lace that camouflages the natural frontal hairline.29,30 A risk of lace-front wigs is that they can cause friction alopecia secondary to repeated use of adhesives and repeated friction against the hairline. Generally, wigs and weaves should be cared for as one would care for one’s own hair.

Hair Care in Black Children—Children’s hair care begins with washing the hair and scalp with shampoo, applying conditioner, and detangling as needed.31 After rinsing out the conditioner, a leave-in conditioner can assist with moisture retention and further detangling. The hair is then styled, either wet or dry. Recommendations for hair care practices in Black children include loose hairstyles that do not strain hair roots and nightly removal of root-securing accessories (eg, barrettes, elastic hairbeads). Frequent cornrow styling and friction on chemically straightened hair were identified by a survey as considerable traction alopecia risk factors.32 Thus, educating caregivers on appropriate hair-grooming practices for children is important.

Hair Protection—Proactive steps to reduce hair loss include wearing satin bonnets and/or using satin pillowcases while sleeping regardless of hairstyle. Although evidence is limited, it is thought that satin and silk allow the hair to retain its moisture and natural oils, preventing breakage and friction.33,34 Frequent hair trimming every 2 to 4 months can reduce breakage when doing thermal treatments.35,36 When prolonged or repetitive styles are used, it is encouraged to give the hair a break between styles to recover from the repeated stress. Wearing an intermittent updo or high bun—a hairstyle in which the hair is pulled upward—can prevent breakage by reducing heavy strain on the hair; however, it is important to avoid the use of rubber bands due to friction and risk for tangling of hair strands. Instead, the use of covered elastic ties and/or those without metal is preferred.11 Alternatively, if a polished and neat appearance with slicked-back hair is desired, the practice of tautly pulling the hair is not recommended. Instead, use of an alcohol-free gel is suggested along with a satin scarf wrapped around the hairline to facilitate the setting of the hair in place.11

A common practice to preserve curly hairstyles while sleeping is known as the pineapple method, which protects the hair and aids in preserving the freshness and style of the curls.37 It consists of a loosely tied high ponytail at the top of the head allowing the curls to fall forward. This minimizes frizz and prevents the curls from forming knots.

Conclusion

Hair care recommendations in Black women can be complex due to a wide range of personal care preferences and styling techniques in this population. While evidence in the literature is limited, it still is important for dermatologists to be familiar with the different hair care practices utilized by Black women so they can effectively counsel patients and improve hair health. Knowledge of optimal hair care practices can aid in the prevention of common hair disorders that disproportionately affect this patient population, such as traction alopecia and trichorrhexis nodosa or breakage.

Patients often ask dermatologists how to best care for their specific hair type; however, there are no formal recommendations that apply to the many different hair care practices utilized by Black patients, as hair types in this community can range from wavy to tightly coiled.1 Understanding the the history of hair care in those of African ancestry and various styling practices in this population is necessary to adequately counsel patients and gain trust in the doctor-patient relationship. In this article, we provide an overview of hair care recommendations based on common styling practices in Black women.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Black hair care, African American hair management, hair loss prevention, hair care practices, natural hair, natural-hair styles, alopecia, hairdressing, hair breakage, hair fragility, heat-stressed hair, traction alopecia, and natural hair care yielded 305 results; 107 duplicates were identified and removed, leaving 198 articles to be screened for eligibility (ie, English-language studies created in the past 15 years). Sixty-eight full-text articles were screened against the exclusion criteria, which included case reports and case series, articles not focused on Afro-textured hair, and cancer-related hair loss. Three additional fulltext articles were identified via resources from Wayne State University library (Detroit, Michigan) that were not available on PubMed. A total of 29 full-text articles were included in our review.

Background on Hair Care and Styling in African Populations

It is difficult to understand the history of hair in those of African ancestry in the United States.2 Prior to slavery, hair styling was considered a way of identification, classification, and communication as well as a medium through which to connect with the spiritual world in many parts of Africa. Hair-styling practices in Africa included elaborate cornrows, threading, and braiding with many accessories. Notable hair-styling products included natural butters, herbs, and powders to assist with moisture retention. Scarves also were used during this time for ceremonies or protection.3 During the mass enslavement of African populations and their transportation to the Americas by Europeans, slaveholders routinely cut off all the hair of both men and women in order to objectify and erase the culture of African hair styling passed down through generations.4,5 Hair texture then was weaponized to create a caste system in plantation life, in which Black slaves with straight hair textures were granted the “privilege” of domestic work, while those with kinky hair were relegated to arduous manual labor in the fields.4 Years later, during the 1800s, laws were enacted in the United States to prohibit Black women from wearing tightly coiled natural hair in public places.5 Over the next few centuries from the 1800s to the early 2000s, various hair-styling trends such as the use of hot combs, perms, afros, and Jheri curls developed as a means for Black individuals to conform to societal pressure to adopt more European features; however, as time progressed, afros, braids, locs, and natural hair would become more dominant as statements against these same societal pressures.5

The natural hair movement, which emerged in the United States in the 2000s, encouraged Black women to abandon the use of toxic chemical hair straighteners, cultivate healthier hair care practices, disrupt Eurocentric standards of wearing straightened hair, and facilitate self-definition of beauty ideals from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.4,5 It is estimated that between 30% and 70% of all Black women in the United States wear natural hair, including 79% of millennial Black women younger than 30 years6; however, several new trends such as wigs and weaves have grown in popularity since the early 2000s due to mainstream pop culture and improvements in creating natural hairlines.7,8

Key Features of Afro-Textured Hair

Individuals of African descent have the most diverse hair texture phenotypes, ranging from straight to tightly coiled.9 Although hair is chemically similar across various racial groups, differences are noted mainly in the shape of the hair shaft, with elliptical and curved shapes seen in Afrotextured hair. These differences yield more tightly curled strands than in other hair types; however, these features also contribute to fragility, as it creates points of weakness and decreases the tensile strength of the hair shaft.10 This inherent fragility leads to higher rates of hair breakage as well as lower moisture content and slower growth rates, which is why Afro-textured hair requires special care.9

Afro-textured hair generally falls into 2 main categories of the Andre Walker hair typing system: 4A-4C and 3A-3C.11 In the 4A-4C category, hair is described as coily or kinky. Common concerns related to this hair type include dryness and brittleness with increased susceptibility to breakage. The 3A-3C category is described as loose to corkscrew curls, with a common concern of dryness.11,12 Additionally, Loussouarn et al13 established a method to further define natural hair curliness using curve diameter and curl meters on glass plates to measure the curvature of hair strands. This method allows for assessing diversity and range of curliness within various races without relying on ethnic origin.13

Common Hair Care Practices

A description of each hair type and recommended styling practices with their levels of evidence can be found in the eTable.

Natural Hair—Natural hair is classified as hair that has not been chemically changed by perms, heat, or other straightening treatments.12,14 For natural hair, retaining the moisture of the hair shaft should be the main focus, as moisture loss leads to considerable dryness.14 Generally, it is recommended to wash natural hair once per week or every other week; however, this can change based on hair length and oil production on the scalp. Washing daily may be ideal for shorter hair and monthly for longer hair to help prevent product build-up that can have a drying effect.15 Avoid shampoos that are drying (eg, sulfate and silicone products). The co-washing method also can be utilized, which entails washing the hair with a conditioning cleanser instead of shampoo and conditioner. However, this technique is not meant to completely replace shampoo.16 In fact, a clarifying shampoo is recommended after co-washing 3 or 4 times.16 The use of a hot oil treatment twice per month can promote moisture retention and reduce split-end formation.17 For maintenance between washes, many utilize the liquid, oil, cream (LOC) or liquid, cream, oil (LCO) methods, which describe regimens that utilize water, an oil of choice, and cream such as shea butter to lock in moisture.18 This method can be used as often as needed for dry hair.

Due to the susceptibility of Afro-textured hair to tangle and knot, using a wide-tooth comb, detangling brush, or detangling conditioners is a grade B recommendation for care (eTable). Though not widely documented in the literature, many of our patients have had anecdotal success detangling their hair simply by pulling hair strands apart by hand or “finger detangling” as well as using wide-tooth combs. Although both hair types are healthier in their natural states, kinky hair (type 4A-4C) is extremely fragile and more difficult to manage than less kinky hair (type 3A-3C).18

Special care is needed when detangling due to strands being weaker when wet.19 Detangling should be performed in a retrograde fashion. Deep conditioning can aid in moisture retention and should be performed weekly or biweekly.17-20 Depending on the health of the hair, protein treatments can be considered on a monthly basis to help preserve the cuticle. Styling with braids, twists, or other protective styles can then be completed on an individual basis.

Thermal Straightening—A blowout involves straightening the hair after a wash with the use of a hair dryer.21 This common hair-styling method does not employ the use of chemicals beyond light hair oils and heat-protectant creams or sprays, typically resulting in a less kinky afro or semi-straight hair. Thermal straightening utilizes heat to temporarily straighten hair strands. Flat irons with heated metal plates then can be used after blow-drying the hair to fully straighten and smooth the strands. These processes combined commonly are known as a silk press.21-22

For thermally straightened hair, it is recommended to either wrap the hair around the scalp to keep it flat or pin curl the hair and cover with a bonnet to sleep. Safe straightening techniques with the use of a flat iron include setting the temperature no higher than 175 °F or a low/medium setting while also limiting use to once per week if possible.23 The number of passes of the flat iron also should be limited to 1 to 2 to reduce breakage. A heat-protectant cream or spray also can be applied to the hair before flat ironing to minimize damage. Applying heat protectant to the hair prior to styling will help minimize heat damage by distributing the heat along the hair fiber surface, avoiding water boiling in the hair shaft and the development of bubble hair leading to damage.24

Chemical Straightening—Similar to how relaxers, perms, and Jheri curl treatments chemically modify hair texture using distinct chemicals yielding different curl patterns, the Brazilian blowout similarly straightens hair using a hair dryer and chemicals applied to hair strands after washing.21-24 Relaxers utilize sodium or guanidine hydroxide for straightening, perms use ammonium thioglycolate for curling, and Jheri curl treatments employ thioglycolates or mercaptans for defined curls. However, these treatments generally are cautioned against due to potential hair damage and recent associations with uterine and breast cancer in Black women. Research has suggested that endocrine disrupters in these products, especially those marketed to Black women, contribute to hormone-related disease processes.25,26 One study found higher concentrations of alkylphenols, the fragrance marker diethyl phthalate, and parabens in relaxers27; however, more research is needed to determine specific chemicals associated with these cancers.

Braids and Locs—Braiding is a technique that involves interlocking 3 or more sections of hair that may or may not be fixated to the scalp like a cornrow,11 and one can utilize extensions or natural hair depending on the desired outcome. Intended for long-term wear (ie, weeks to months), braids minimize breakage and reduce daily styling needs. Two popular styles—cornrows and individual braids—differ in preparation and weaving techniques. Cornrows are an Afro-centric style involving uniform, tightly woven braids that are close to the scalp, creating distinct patterns. Conversely, individual braids weave separate hair sections, offering diverse styling possibilities. Braiding practices should exclude hairline edges—often termed baby hairs—to prevent traction alopecia. Minimal use of edge gel, which helps to tame the vellus hairs at the frontotemporal scalp, as well as mindful weave volume, weight, and length are recommended to avert breakage. Braids that cause pain are too tight, can damage hair, and may cause traction alopecia.11 Braids should not be worn for longer than 3 months at a time and require biweekly washing with diluted shampoo and conditioner. Proper drying by wringing the hair with a microfiber towel is essential to avoid frizz and mold formation.

Locs are a low-maintenance hairstyle considered permanent until cut.28 This style involves twisting, palm rolling, or using tools such as crochet hooks to “lock” the hair. Regular maintenance with retwisting and cleaning is vital for loc health. Increased weight and tight twisting of locs can cause damage to the scalp and hair strands; however, locs are known to increase hair volume over time, often due to the accumulation of hairs that would otherwise have been shed in the telogen phase.28

Wigs and Weaves—Wigs consist of synthetic or human hair that can be strapped to the head with an adjustable band or glued to the scalp depending on the desired style.29 Wigs are removed daily, which allows for quick access to hair for cleansing and moisturizing. In contrast, weaves typically are sewn into the natural hair, which may make it difficult to reach the scalp for cleansing, leading to dryness and product build-up.29 Notably, there is evidence of a relationship between long-term use of weaves and traction alopecia.30

Wigs can have a fully synthetic hair line or lace hair line and can range from very affordable to expensive. When applied correctly, both styles offer an easy way to cover and protect the natural hair by reducing the amount of physical trauma related to daily hair styling. A lace-front wig contains a frontal thin mesh or lace that camouflages the natural frontal hairline.29,30 A risk of lace-front wigs is that they can cause friction alopecia secondary to repeated use of adhesives and repeated friction against the hairline. Generally, wigs and weaves should be cared for as one would care for one’s own hair.

Hair Care in Black Children—Children’s hair care begins with washing the hair and scalp with shampoo, applying conditioner, and detangling as needed.31 After rinsing out the conditioner, a leave-in conditioner can assist with moisture retention and further detangling. The hair is then styled, either wet or dry. Recommendations for hair care practices in Black children include loose hairstyles that do not strain hair roots and nightly removal of root-securing accessories (eg, barrettes, elastic hairbeads). Frequent cornrow styling and friction on chemically straightened hair were identified by a survey as considerable traction alopecia risk factors.32 Thus, educating caregivers on appropriate hair-grooming practices for children is important.

Hair Protection—Proactive steps to reduce hair loss include wearing satin bonnets and/or using satin pillowcases while sleeping regardless of hairstyle. Although evidence is limited, it is thought that satin and silk allow the hair to retain its moisture and natural oils, preventing breakage and friction.33,34 Frequent hair trimming every 2 to 4 months can reduce breakage when doing thermal treatments.35,36 When prolonged or repetitive styles are used, it is encouraged to give the hair a break between styles to recover from the repeated stress. Wearing an intermittent updo or high bun—a hairstyle in which the hair is pulled upward—can prevent breakage by reducing heavy strain on the hair; however, it is important to avoid the use of rubber bands due to friction and risk for tangling of hair strands. Instead, the use of covered elastic ties and/or those without metal is preferred.11 Alternatively, if a polished and neat appearance with slicked-back hair is desired, the practice of tautly pulling the hair is not recommended. Instead, use of an alcohol-free gel is suggested along with a satin scarf wrapped around the hairline to facilitate the setting of the hair in place.11

A common practice to preserve curly hairstyles while sleeping is known as the pineapple method, which protects the hair and aids in preserving the freshness and style of the curls.37 It consists of a loosely tied high ponytail at the top of the head allowing the curls to fall forward. This minimizes frizz and prevents the curls from forming knots.

Conclusion

Hair care recommendations in Black women can be complex due to a wide range of personal care preferences and styling techniques in this population. While evidence in the literature is limited, it still is important for dermatologists to be familiar with the different hair care practices utilized by Black women so they can effectively counsel patients and improve hair health. Knowledge of optimal hair care practices can aid in the prevention of common hair disorders that disproportionately affect this patient population, such as traction alopecia and trichorrhexis nodosa or breakage.

- Hall RR, Francis S, Whitt-Glover M, et al. Hair care practices as a barrier to physical activity in African American women. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:310-314. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.1946

- Johnson T, Bankhead T. Hair it is: examining the experiences of Black women with natural hair. Open J Soc Sci. 2014;02:86-100. doi:10.4236/jss.2014.21010

- Byrd AD, Tharps LL. Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America. 2nd ed. St Martin’s Griffin; 2014.

- Mbilishaka AM, Clemons K, Hudlin M, et al. Don’t get it twisted: untangling the psychology of hair discrimination within Black communities. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2020;90:590-599. doi:10.1037 /ort0000468

- Khumalo NP. On the history of African hair care: more treasures await discovery. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;7:231. doi:10.1111/j.1473- 2165.2008.00396.x

- Johnson AM, Godsil RD, MacFarlane J, et al. The “good hair” study: explicit and implicit attitudes toward Black women’s hair. Perception Institute. February 2017. Accessed February 11, 2025. https://perception.org/publications/goodhairstudy/

- Haskin A, Aguh C. All hairstyles are not created equal: what the dermatologist needs to know about black hairstyling practices and the risk of traction alopecia (TA). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:606-611. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1162

- Roseborough IE, McMichael AJ. Hair care practices in African- American patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:103-108. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2009.04.007

- Menkart J Wolfram LJ Mao I. Caucasian hair, Negro hair and wool: similarities and differences. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1996;17:769-787.

- Crawford K, Hernandez C. A review of hair care products for black individuals. Cutis. 2014;93:289-293.

- Mayo TT, Callender VD. The art of prevention: it’s too tight-loosen up and let your hair down. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:174-179. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.019

- De Sá Dias TC, Baby AR, Kaneko TM, et al. Relaxing/straightening of Afro-ethnic hair: historical overview. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:2-5. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00294.x

- Loussouarn G, Garcel AL, Lozano I, et al. Worldwide diversity of hair curliness: a new method of assessment. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46 (suppl 1):2-6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03453.x

- Barba C, Mendez S, Marti M, et al. Water content of hair and nails. Thermochimica Acta. 2009;494:136-140. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2009.05.005

- Gray J. Hair care and hair care products. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:227-236. doi:10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00133-4

- Gavazzoni Dias MFR. Pro and contra of cleansing conditioners. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:131-134. doi:10.1159/000493588

- Gavazzoni Dias MFR. Hair cosmetics: an overview. Int J Trichology. 2015;7:2-15. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.153450

- Beal AC, Villarosa L, Abner A. The Black Parenting Book. 1999.

- Davis-Sivasothy A. The Science of Black Hair: A Comprehensive Guide to Textured Care. Saga Publishing; 2011.

- Robbins CR. The Physical Properties and Cosmetic Behavior of Hair. In: Robbins CR. Chemical and Physical Behavior of Human Hair. 3rd ed. Springer Nature; 1994:299-370. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-3898-8_8

- Weathersby C, McMichael A. Brazilian keratin hair treatment: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:144-148. doi:10.1111/jocd.12030

- Barreto T, Weffort F, Frattini S, et al. Straight to the point: what do we know so far on hair straightening? Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:265-271. doi:10.1159/000514367

- Dussaud A, Rana B, Lam HT. Progressive hair straightening using an automated flat iron: function of silicones. J Cosmet Sci. 2013;64:119-131.

- Zhou Y, Rigoletto R, Koelmel D, et al. The effect of various cosmetic pretreatments on protecting hair from thermal damage by hot flat ironing. J Cosmet Sci. 2011;62:265-282.

- Chang CJ, O’Brien KM, Keil AP, et al. Use of straighteners and other hair products and incident uterine cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114:1636-1645. doi:10.1093/jnci/djac165

- White AJ, Gregoire AM, Taylor KW, et al. Adolescent use of hair dyes, straighteners and perms in relation to breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:2255-2263. doi:10.1002/ijc.33413

- Helm JS, Nishioka M, Brody JG, et al. Measurement of endocrine disrupting and asthma-associated chemicals in hair products used by Black women. Environ Res. 2018;165:448-458.

- Asbeck S, Riley-Prescott C, Glaser E, et al. Afro-ethnic hairstyling trends, risks, and recommendations. Cosmetics. 2022;9:17. doi:10.3390 /cosmetics9010017

- Saed S, Ibrahim O, Bergfeld WF. Hair camouflage: a comprehensive review. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2016;2:122-127. doi:10.1016 /j.ijwd.2016.09.002

- Billero V, Miteva M. Traction alopecia: the root of the problem. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:149-159. doi:10.2147/CCID .S137296

- Jones NL, Heath CR. Hair at the intersection of dermatology and anthropology: a conversation on race and relationships. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38(suppl 2):158-160. doi:10.1111/pde.14721

- Rucker Wright D, Gathers R, Kapke A, et al. Hair care practices and their association with scalp and hair disorders in African American girls. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:253-262. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.037

- Carefoot H. Silk pillowcases for better hair and skin: what to know. The Washington Post. April 6, 2021. Accessed February 10, 2025. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/wellness/silk-pillowcases-hair-skin-benefits-myths/2021/04/05/a7dcad7c-866a-11eb-82bc-e58213caa38e_story.html

- Samrao A, McMichael A, Mirmirani P. Nocturnal traction: techniques used for hair style maintenance while sleeping may be a risk factor for traction alopecia. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:220-223. doi:10.1159/000513088

- Callender VD, McMichael AJ, Cohen GF. Medical and surgical therapies for alopecias in black women. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:164-176. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04017.x

- McMichael AJ. Hair breakage in normal and weathered hair: focus on the Black patient. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2007;12:6-9. doi:10.1038/sj.jidsymp.5650047

- Bosley RE, Daveluy S. A primer to natural hair care practices in black patients. Cutis. 2015;95:78-80,106.

- Hall RR, Francis S, Whitt-Glover M, et al. Hair care practices as a barrier to physical activity in African American women. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:310-314. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.1946

- Johnson T, Bankhead T. Hair it is: examining the experiences of Black women with natural hair. Open J Soc Sci. 2014;02:86-100. doi:10.4236/jss.2014.21010

- Byrd AD, Tharps LL. Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America. 2nd ed. St Martin’s Griffin; 2014.

- Mbilishaka AM, Clemons K, Hudlin M, et al. Don’t get it twisted: untangling the psychology of hair discrimination within Black communities. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2020;90:590-599. doi:10.1037 /ort0000468

- Khumalo NP. On the history of African hair care: more treasures await discovery. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;7:231. doi:10.1111/j.1473- 2165.2008.00396.x

- Johnson AM, Godsil RD, MacFarlane J, et al. The “good hair” study: explicit and implicit attitudes toward Black women’s hair. Perception Institute. February 2017. Accessed February 11, 2025. https://perception.org/publications/goodhairstudy/

- Haskin A, Aguh C. All hairstyles are not created equal: what the dermatologist needs to know about black hairstyling practices and the risk of traction alopecia (TA). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:606-611. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1162

- Roseborough IE, McMichael AJ. Hair care practices in African- American patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:103-108. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2009.04.007

- Menkart J Wolfram LJ Mao I. Caucasian hair, Negro hair and wool: similarities and differences. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1996;17:769-787.

- Crawford K, Hernandez C. A review of hair care products for black individuals. Cutis. 2014;93:289-293.

- Mayo TT, Callender VD. The art of prevention: it’s too tight-loosen up and let your hair down. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:174-179. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.01.019

- De Sá Dias TC, Baby AR, Kaneko TM, et al. Relaxing/straightening of Afro-ethnic hair: historical overview. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:2-5. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00294.x

- Loussouarn G, Garcel AL, Lozano I, et al. Worldwide diversity of hair curliness: a new method of assessment. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46 (suppl 1):2-6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03453.x

- Barba C, Mendez S, Marti M, et al. Water content of hair and nails. Thermochimica Acta. 2009;494:136-140. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2009.05.005

- Gray J. Hair care and hair care products. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:227-236. doi:10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00133-4

- Gavazzoni Dias MFR. Pro and contra of cleansing conditioners. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:131-134. doi:10.1159/000493588

- Gavazzoni Dias MFR. Hair cosmetics: an overview. Int J Trichology. 2015;7:2-15. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.153450

- Beal AC, Villarosa L, Abner A. The Black Parenting Book. 1999.

- Davis-Sivasothy A. The Science of Black Hair: A Comprehensive Guide to Textured Care. Saga Publishing; 2011.

- Robbins CR. The Physical Properties and Cosmetic Behavior of Hair. In: Robbins CR. Chemical and Physical Behavior of Human Hair. 3rd ed. Springer Nature; 1994:299-370. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-3898-8_8

- Weathersby C, McMichael A. Brazilian keratin hair treatment: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:144-148. doi:10.1111/jocd.12030

- Barreto T, Weffort F, Frattini S, et al. Straight to the point: what do we know so far on hair straightening? Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:265-271. doi:10.1159/000514367

- Dussaud A, Rana B, Lam HT. Progressive hair straightening using an automated flat iron: function of silicones. J Cosmet Sci. 2013;64:119-131.

- Zhou Y, Rigoletto R, Koelmel D, et al. The effect of various cosmetic pretreatments on protecting hair from thermal damage by hot flat ironing. J Cosmet Sci. 2011;62:265-282.

- Chang CJ, O’Brien KM, Keil AP, et al. Use of straighteners and other hair products and incident uterine cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114:1636-1645. doi:10.1093/jnci/djac165

- White AJ, Gregoire AM, Taylor KW, et al. Adolescent use of hair dyes, straighteners and perms in relation to breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:2255-2263. doi:10.1002/ijc.33413

- Helm JS, Nishioka M, Brody JG, et al. Measurement of endocrine disrupting and asthma-associated chemicals in hair products used by Black women. Environ Res. 2018;165:448-458.

- Asbeck S, Riley-Prescott C, Glaser E, et al. Afro-ethnic hairstyling trends, risks, and recommendations. Cosmetics. 2022;9:17. doi:10.3390 /cosmetics9010017

- Saed S, Ibrahim O, Bergfeld WF. Hair camouflage: a comprehensive review. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2016;2:122-127. doi:10.1016 /j.ijwd.2016.09.002

- Billero V, Miteva M. Traction alopecia: the root of the problem. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:149-159. doi:10.2147/CCID .S137296

- Jones NL, Heath CR. Hair at the intersection of dermatology and anthropology: a conversation on race and relationships. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38(suppl 2):158-160. doi:10.1111/pde.14721

- Rucker Wright D, Gathers R, Kapke A, et al. Hair care practices and their association with scalp and hair disorders in African American girls. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:253-262. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.037

- Carefoot H. Silk pillowcases for better hair and skin: what to know. The Washington Post. April 6, 2021. Accessed February 10, 2025. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/wellness/silk-pillowcases-hair-skin-benefits-myths/2021/04/05/a7dcad7c-866a-11eb-82bc-e58213caa38e_story.html

- Samrao A, McMichael A, Mirmirani P. Nocturnal traction: techniques used for hair style maintenance while sleeping may be a risk factor for traction alopecia. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:220-223. doi:10.1159/000513088

- Callender VD, McMichael AJ, Cohen GF. Medical and surgical therapies for alopecias in black women. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:164-176. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2004.04017.x

- McMichael AJ. Hair breakage in normal and weathered hair: focus on the Black patient. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2007;12:6-9. doi:10.1038/sj.jidsymp.5650047

- Bosley RE, Daveluy S. A primer to natural hair care practices in black patients. Cutis. 2015;95:78-80,106.

Historical Perspectives on Hair Care and Common Styling Practices in Black Women

Historical Perspectives on Hair Care and Common Styling Practices in Black Women

PRACTICE POINTS

- There is a dearth in understanding of hair care practices in Black women among health care professionals.

- Increased knowledge and cultural understanding of past and present hair care practices in Black women enhances patient care.