User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

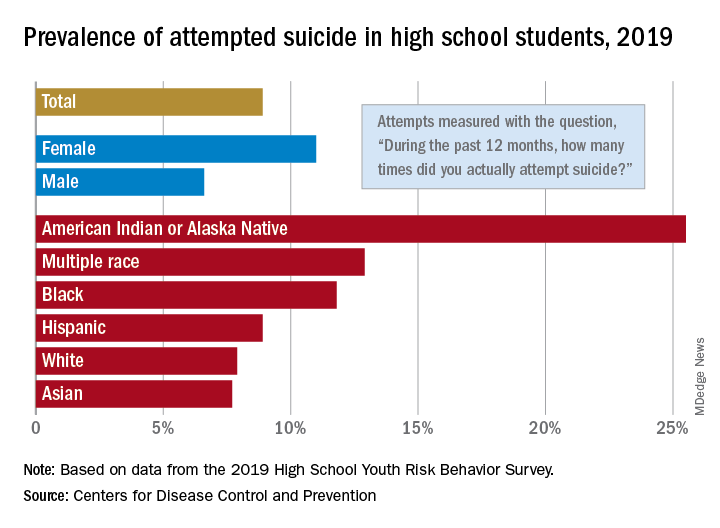

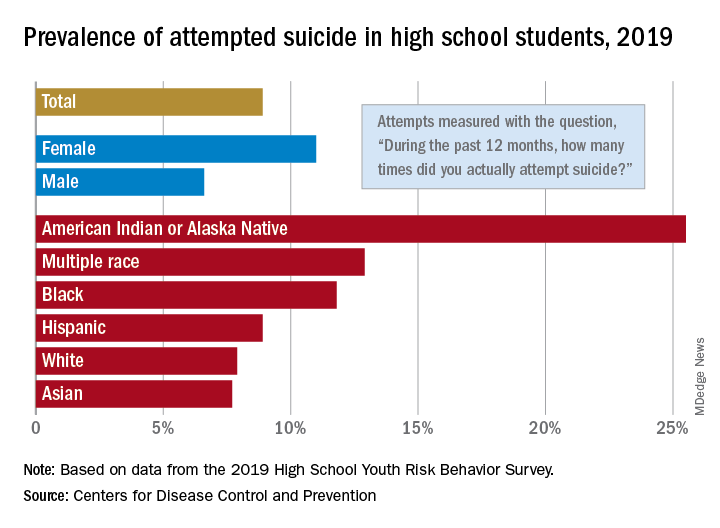

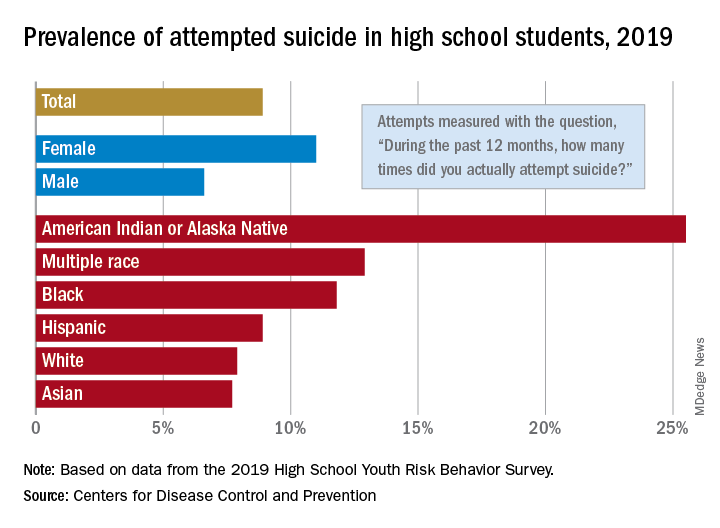

Attempted suicide in high school America, 2019

according to newly released data from the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

The prevalence of attempted suicide during the previous 12 months was 8.9% among the 13,677 students in grades 9-12 who took the survey last year, but the rate was 25.5% for American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) respondents, almost 2.9 times higher, the YRBS data show.

Respondents with multiple races in their backgrounds, at 12.9%, and African Americans, with a prevalence of 11.8%, also were above the high school average for suicide attempts, while Whites (7.9%) and Asians (7.7%) were under it and Hispanics equaled it, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

The number of AI/AN students was insufficient to examine differences by sex, but females in all of the other racial/ethnic groups were more likely than males to have attempted suicide: multiple race (17.8% vs. 7.3%), African American (15.2% vs. 8.5%), Hispanic (11.9% vs. 5.5%), White (9.4% vs. 6.4%), and Asian (8.4% vs. 7.1%), the CDC’s Division of Adolescent and School Health said.

Among all respondents, 11.0% of females had attempted suicide in the 12 months before the survey, a figure that is significantly higher than the 6.6% prevalence in males. Females also were significantly more likely than males to make a plan about how they would attempt suicide (19.9% vs. 11.3%) and to seriously consider an attempt (24.1% vs. 13.3%), CDC investigators said in a separate report.

Significant differences also were seen when looking at sexual identity. Suicide attempts were reported by 6.4% of heterosexuals, 16.1% of those who weren’t sure, and 23.4% of lesbians/gays/bisexuals (LGBs). For serious consideration of suicide, the respective numbers were 14.5%, 30.4%, and 46.8%, they reported (MMWR Supp. 2020 Aug 21;69[1]:47-55).

For nonheterosexuals, however, males were slightly more likely (23.8%) than females (23.6%) to have attempted suicide, but females were more likely to seriously consider it (49.0% vs. 40.4%) and to make a plan (42.4% vs. 33.0%), according to the YRBS data.

“Adolescence … represents a time for expanded identity development, with sexual identity development representing a complex, multidimensional, and often stressful process for youths,” the CDC investigators said in the MMWR. “To address the health differences in suicidal ideation and behaviors observed by student demographics and to decrease these outcomes overall, a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention, including programs, practices, and policies based on the best available evidence, is needed.”

according to newly released data from the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

The prevalence of attempted suicide during the previous 12 months was 8.9% among the 13,677 students in grades 9-12 who took the survey last year, but the rate was 25.5% for American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) respondents, almost 2.9 times higher, the YRBS data show.

Respondents with multiple races in their backgrounds, at 12.9%, and African Americans, with a prevalence of 11.8%, also were above the high school average for suicide attempts, while Whites (7.9%) and Asians (7.7%) were under it and Hispanics equaled it, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

The number of AI/AN students was insufficient to examine differences by sex, but females in all of the other racial/ethnic groups were more likely than males to have attempted suicide: multiple race (17.8% vs. 7.3%), African American (15.2% vs. 8.5%), Hispanic (11.9% vs. 5.5%), White (9.4% vs. 6.4%), and Asian (8.4% vs. 7.1%), the CDC’s Division of Adolescent and School Health said.

Among all respondents, 11.0% of females had attempted suicide in the 12 months before the survey, a figure that is significantly higher than the 6.6% prevalence in males. Females also were significantly more likely than males to make a plan about how they would attempt suicide (19.9% vs. 11.3%) and to seriously consider an attempt (24.1% vs. 13.3%), CDC investigators said in a separate report.

Significant differences also were seen when looking at sexual identity. Suicide attempts were reported by 6.4% of heterosexuals, 16.1% of those who weren’t sure, and 23.4% of lesbians/gays/bisexuals (LGBs). For serious consideration of suicide, the respective numbers were 14.5%, 30.4%, and 46.8%, they reported (MMWR Supp. 2020 Aug 21;69[1]:47-55).

For nonheterosexuals, however, males were slightly more likely (23.8%) than females (23.6%) to have attempted suicide, but females were more likely to seriously consider it (49.0% vs. 40.4%) and to make a plan (42.4% vs. 33.0%), according to the YRBS data.

“Adolescence … represents a time for expanded identity development, with sexual identity development representing a complex, multidimensional, and often stressful process for youths,” the CDC investigators said in the MMWR. “To address the health differences in suicidal ideation and behaviors observed by student demographics and to decrease these outcomes overall, a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention, including programs, practices, and policies based on the best available evidence, is needed.”

according to newly released data from the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

The prevalence of attempted suicide during the previous 12 months was 8.9% among the 13,677 students in grades 9-12 who took the survey last year, but the rate was 25.5% for American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) respondents, almost 2.9 times higher, the YRBS data show.

Respondents with multiple races in their backgrounds, at 12.9%, and African Americans, with a prevalence of 11.8%, also were above the high school average for suicide attempts, while Whites (7.9%) and Asians (7.7%) were under it and Hispanics equaled it, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

The number of AI/AN students was insufficient to examine differences by sex, but females in all of the other racial/ethnic groups were more likely than males to have attempted suicide: multiple race (17.8% vs. 7.3%), African American (15.2% vs. 8.5%), Hispanic (11.9% vs. 5.5%), White (9.4% vs. 6.4%), and Asian (8.4% vs. 7.1%), the CDC’s Division of Adolescent and School Health said.

Among all respondents, 11.0% of females had attempted suicide in the 12 months before the survey, a figure that is significantly higher than the 6.6% prevalence in males. Females also were significantly more likely than males to make a plan about how they would attempt suicide (19.9% vs. 11.3%) and to seriously consider an attempt (24.1% vs. 13.3%), CDC investigators said in a separate report.

Significant differences also were seen when looking at sexual identity. Suicide attempts were reported by 6.4% of heterosexuals, 16.1% of those who weren’t sure, and 23.4% of lesbians/gays/bisexuals (LGBs). For serious consideration of suicide, the respective numbers were 14.5%, 30.4%, and 46.8%, they reported (MMWR Supp. 2020 Aug 21;69[1]:47-55).

For nonheterosexuals, however, males were slightly more likely (23.8%) than females (23.6%) to have attempted suicide, but females were more likely to seriously consider it (49.0% vs. 40.4%) and to make a plan (42.4% vs. 33.0%), according to the YRBS data.

“Adolescence … represents a time for expanded identity development, with sexual identity development representing a complex, multidimensional, and often stressful process for youths,” the CDC investigators said in the MMWR. “To address the health differences in suicidal ideation and behaviors observed by student demographics and to decrease these outcomes overall, a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention, including programs, practices, and policies based on the best available evidence, is needed.”

Mitigating psychiatric disorder relapse in pregnancy during pandemic

In a previous column, I addressed some of the issues that quickly arose in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and their implications for reproductive psychiatry. These issues ranged from the importance of sustaining well-being in pregnant and postpartum women during the pandemic, to temporary restrictions that were in place during the early part of the pandemic with respect to performing infertility procedures, to the practical issues of limiting the number of people who could attend to women during labor and delivery in the hospital.

Five months later, we’ve learned a great deal about trying to sustain emotional well-being among pregnant women during COVID-19. There is a high rate of anxiety among women who are pregnant and women who have particularly young children around the various issues of juggling activities of daily living during the pandemic, including switching to remote work and homeschooling children. There is fear of contracting COVID-19 during pregnancy, the exact effects of which are still somewhat unknown. We have seen a shift to telemedicine for prenatal and postpartum obstetrics visits, and a change with respect to visitors and even in-home nurses that would help during the first weeks of life for some couples.

We wondered whether we would see a falloff in the numbers of women presenting to our clinic with questions about the reproductive safety of taking psychiatric medications during pregnancy. We were unclear as to whether women would defer plans to get pregnant given some of the uncertainties that have come with COVID-19. What we’ve seen, at least early on in the pandemic in Massachusetts, has been the opposite. More women during the first 4 months of the pandemic have been seen in our center compared with the same corresponding period over the last 5 years. The precise reasons for this are unclear, but one reason may be that shifting the practice of reproductive psychiatry and pregnancy planning for reproductive-age women to full virtual care has dropped the number of missed appointments to essentially zero. Women perhaps feel an urgency to have a plan for using psychiatric medication during pregnancy. They may also see the benefit of being able to have extended telemedicine consultations that frequently involve their partners, a practice we have always supported, but posed logistical challenges for some.

As our colleagues learned that we had shifted our clinical rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health, which we’ve been doing for 25 years, to a virtual format, we began offering a free 1-hour forum to discuss relevant issues around caring for psychiatrically ill women, with a focus on some of the issues that were particularly relevant during the pandemic. The most common reasons for consultation on our service are the appropriate, safest use of antidepressants and mood stabilizers during pregnancy, and that continues to be the case.

If there has been one guiding principle in treating perinatal depression during pregnancy, it has been our long-standing, laser-like focus on keeping women emotionally well during pregnancy, and to highlight the importance of this with women during consultations prior to and during pregnancy. Relapse of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy is one the strongest predictors of postpartum depression, and the impact of untreated depression during pregnancy has been described in the literature and over the years in this column. However, where we want to minimize, if possible, severe onset of illness requiring hospitalization or emergent attention considering it may make social distancing and some of the other mitigating factors vis-à-vis COVID-19 more challenging.

Despite the accumulated data over the last 2 decades on the reproductive safety of antidepressants, women continue to have questions about the safety of these medications during pregnancy. Studies show now that many women would prefer, if at all possible, to defer treatment with antidepressants, and so they come to us with questions about their reproductive safety, the potential of switching to nonpharmacologic interventions, and the use of alternative interventions that might be used to treat their underlying mood disorder.

Investigators at the University of British Columbia recently have tried to inform the field with still another look, not at reproductive safety per se, but at risk of relapse of depression if women discontinue those medicines during pregnancy.1 There is a timeliness to this investigation, which was a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that met a priori criteria for inclusion. Since some of our own group’s early work over 15 years ago on relapse of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy,2 which indicated a substantial difference in risk of relapse between women who continued versus who discontinued antidepressants, other investigators have showed the difference in risk for relapse is not as substantial, and that continuation of medication did not appear to mitigate risk for relapse. In fact, in the systematic review, the investigators demonstrated that as a group, maintaining medicine did not appear to confer particular benefit to patients relative to risk for relapse compared to discontinuation of antidepressants.

However, looking more closely, Bayrampour and colleagues note for women with histories of more severe recurrent, major depression, relapse did in fact appear to be greater in women who discontinued compared with those with cases of mild to moderate depression. It is noteworthy that in both our early and later work, and certainly dovetailing with our clinical practice, we have noted severity of illness does not appear to correlate with the actual decisions women ultimately make regarding what they will do with antidepressants. Specifically, some women with very severe illness histories will discontinue antidepressants regardless of their risk for relapse. Alternatively, women with mild to moderate illness will sometimes elect to stay on antidepressant therapy. With all the information that we have about fetal exposure to antidepressants on one hand, the “unknown unknowns” are an understandable concern to both patients and clinicians. Clinicians are faced with the dilemma of how to best counsel women on continuing or discontinuing antidepressants as they plan to conceive or during pregnancy and in the postpartum period.

The literature cited and clinical experience over the last 3 decades suggests rather strongly that there is a relatively low likelihood women with histories of severe recurrent disease will be able to successfully discontinue antidepressants in the absence of relapse. A greater question is, what is the best way to proceed for women who have been on maintenance therapy and had more moderate symptoms?

I am inspired by some of the more recent literature that has tried to elucidate the role of nonpharmacologic interventions such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) in an effort to mitigate risk for depressive relapse in pregnant women who are well with histories of depression. To date, data do not inform the question as to whether MBCT can be used to mitigate risk of depressive relapse in pregnant women who continue or discontinue antidepressants. That research question is actively being studied by several investigators, including ourselves.

Of particular interest is whether the addition of mindfulness practices such as MBCT in treatment could mitigate risk for depressive relapse in pregnant women who continue or discontinue antidepressant treatment, as that would certainly be a no-harm intervention that could mitigate risk even in a lower risk sample of patients. The question of how to “thread the needle” during the pandemic and best approach woman with a history of recurrent major depression on antidepressants is particularly timely and critical.

Regardless, we make clinical decisions collaboratively with patients based on their histories and individual wishes, and perhaps what we have learned over the last 5 months is the use of telemedicine does afford us the opportunity, regardless of the decisions that patients make, to more closely follow the clinical trajectory of women during pregnancy and the postpartum period so that regardless of treatment, we have an opportunity to intervene early when needed and to ascertain changes in clinical status early to mitigate the risk of frank relapse. From a reproductive psychiatric point of view, that is a silver lining with respect to the associated challenges that have come along with the pandemic.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

References

1. J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81(4):19r13134.

2. JAMA. 2006 Feb 1;295(5):499-507.

In a previous column, I addressed some of the issues that quickly arose in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and their implications for reproductive psychiatry. These issues ranged from the importance of sustaining well-being in pregnant and postpartum women during the pandemic, to temporary restrictions that were in place during the early part of the pandemic with respect to performing infertility procedures, to the practical issues of limiting the number of people who could attend to women during labor and delivery in the hospital.

Five months later, we’ve learned a great deal about trying to sustain emotional well-being among pregnant women during COVID-19. There is a high rate of anxiety among women who are pregnant and women who have particularly young children around the various issues of juggling activities of daily living during the pandemic, including switching to remote work and homeschooling children. There is fear of contracting COVID-19 during pregnancy, the exact effects of which are still somewhat unknown. We have seen a shift to telemedicine for prenatal and postpartum obstetrics visits, and a change with respect to visitors and even in-home nurses that would help during the first weeks of life for some couples.

We wondered whether we would see a falloff in the numbers of women presenting to our clinic with questions about the reproductive safety of taking psychiatric medications during pregnancy. We were unclear as to whether women would defer plans to get pregnant given some of the uncertainties that have come with COVID-19. What we’ve seen, at least early on in the pandemic in Massachusetts, has been the opposite. More women during the first 4 months of the pandemic have been seen in our center compared with the same corresponding period over the last 5 years. The precise reasons for this are unclear, but one reason may be that shifting the practice of reproductive psychiatry and pregnancy planning for reproductive-age women to full virtual care has dropped the number of missed appointments to essentially zero. Women perhaps feel an urgency to have a plan for using psychiatric medication during pregnancy. They may also see the benefit of being able to have extended telemedicine consultations that frequently involve their partners, a practice we have always supported, but posed logistical challenges for some.

As our colleagues learned that we had shifted our clinical rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health, which we’ve been doing for 25 years, to a virtual format, we began offering a free 1-hour forum to discuss relevant issues around caring for psychiatrically ill women, with a focus on some of the issues that were particularly relevant during the pandemic. The most common reasons for consultation on our service are the appropriate, safest use of antidepressants and mood stabilizers during pregnancy, and that continues to be the case.

If there has been one guiding principle in treating perinatal depression during pregnancy, it has been our long-standing, laser-like focus on keeping women emotionally well during pregnancy, and to highlight the importance of this with women during consultations prior to and during pregnancy. Relapse of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy is one the strongest predictors of postpartum depression, and the impact of untreated depression during pregnancy has been described in the literature and over the years in this column. However, where we want to minimize, if possible, severe onset of illness requiring hospitalization or emergent attention considering it may make social distancing and some of the other mitigating factors vis-à-vis COVID-19 more challenging.

Despite the accumulated data over the last 2 decades on the reproductive safety of antidepressants, women continue to have questions about the safety of these medications during pregnancy. Studies show now that many women would prefer, if at all possible, to defer treatment with antidepressants, and so they come to us with questions about their reproductive safety, the potential of switching to nonpharmacologic interventions, and the use of alternative interventions that might be used to treat their underlying mood disorder.

Investigators at the University of British Columbia recently have tried to inform the field with still another look, not at reproductive safety per se, but at risk of relapse of depression if women discontinue those medicines during pregnancy.1 There is a timeliness to this investigation, which was a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that met a priori criteria for inclusion. Since some of our own group’s early work over 15 years ago on relapse of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy,2 which indicated a substantial difference in risk of relapse between women who continued versus who discontinued antidepressants, other investigators have showed the difference in risk for relapse is not as substantial, and that continuation of medication did not appear to mitigate risk for relapse. In fact, in the systematic review, the investigators demonstrated that as a group, maintaining medicine did not appear to confer particular benefit to patients relative to risk for relapse compared to discontinuation of antidepressants.

However, looking more closely, Bayrampour and colleagues note for women with histories of more severe recurrent, major depression, relapse did in fact appear to be greater in women who discontinued compared with those with cases of mild to moderate depression. It is noteworthy that in both our early and later work, and certainly dovetailing with our clinical practice, we have noted severity of illness does not appear to correlate with the actual decisions women ultimately make regarding what they will do with antidepressants. Specifically, some women with very severe illness histories will discontinue antidepressants regardless of their risk for relapse. Alternatively, women with mild to moderate illness will sometimes elect to stay on antidepressant therapy. With all the information that we have about fetal exposure to antidepressants on one hand, the “unknown unknowns” are an understandable concern to both patients and clinicians. Clinicians are faced with the dilemma of how to best counsel women on continuing or discontinuing antidepressants as they plan to conceive or during pregnancy and in the postpartum period.

The literature cited and clinical experience over the last 3 decades suggests rather strongly that there is a relatively low likelihood women with histories of severe recurrent disease will be able to successfully discontinue antidepressants in the absence of relapse. A greater question is, what is the best way to proceed for women who have been on maintenance therapy and had more moderate symptoms?

I am inspired by some of the more recent literature that has tried to elucidate the role of nonpharmacologic interventions such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) in an effort to mitigate risk for depressive relapse in pregnant women who are well with histories of depression. To date, data do not inform the question as to whether MBCT can be used to mitigate risk of depressive relapse in pregnant women who continue or discontinue antidepressants. That research question is actively being studied by several investigators, including ourselves.

Of particular interest is whether the addition of mindfulness practices such as MBCT in treatment could mitigate risk for depressive relapse in pregnant women who continue or discontinue antidepressant treatment, as that would certainly be a no-harm intervention that could mitigate risk even in a lower risk sample of patients. The question of how to “thread the needle” during the pandemic and best approach woman with a history of recurrent major depression on antidepressants is particularly timely and critical.

Regardless, we make clinical decisions collaboratively with patients based on their histories and individual wishes, and perhaps what we have learned over the last 5 months is the use of telemedicine does afford us the opportunity, regardless of the decisions that patients make, to more closely follow the clinical trajectory of women during pregnancy and the postpartum period so that regardless of treatment, we have an opportunity to intervene early when needed and to ascertain changes in clinical status early to mitigate the risk of frank relapse. From a reproductive psychiatric point of view, that is a silver lining with respect to the associated challenges that have come along with the pandemic.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

References

1. J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81(4):19r13134.

2. JAMA. 2006 Feb 1;295(5):499-507.

In a previous column, I addressed some of the issues that quickly arose in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and their implications for reproductive psychiatry. These issues ranged from the importance of sustaining well-being in pregnant and postpartum women during the pandemic, to temporary restrictions that were in place during the early part of the pandemic with respect to performing infertility procedures, to the practical issues of limiting the number of people who could attend to women during labor and delivery in the hospital.

Five months later, we’ve learned a great deal about trying to sustain emotional well-being among pregnant women during COVID-19. There is a high rate of anxiety among women who are pregnant and women who have particularly young children around the various issues of juggling activities of daily living during the pandemic, including switching to remote work and homeschooling children. There is fear of contracting COVID-19 during pregnancy, the exact effects of which are still somewhat unknown. We have seen a shift to telemedicine for prenatal and postpartum obstetrics visits, and a change with respect to visitors and even in-home nurses that would help during the first weeks of life for some couples.

We wondered whether we would see a falloff in the numbers of women presenting to our clinic with questions about the reproductive safety of taking psychiatric medications during pregnancy. We were unclear as to whether women would defer plans to get pregnant given some of the uncertainties that have come with COVID-19. What we’ve seen, at least early on in the pandemic in Massachusetts, has been the opposite. More women during the first 4 months of the pandemic have been seen in our center compared with the same corresponding period over the last 5 years. The precise reasons for this are unclear, but one reason may be that shifting the practice of reproductive psychiatry and pregnancy planning for reproductive-age women to full virtual care has dropped the number of missed appointments to essentially zero. Women perhaps feel an urgency to have a plan for using psychiatric medication during pregnancy. They may also see the benefit of being able to have extended telemedicine consultations that frequently involve their partners, a practice we have always supported, but posed logistical challenges for some.

As our colleagues learned that we had shifted our clinical rounds at the Center for Women’s Mental Health, which we’ve been doing for 25 years, to a virtual format, we began offering a free 1-hour forum to discuss relevant issues around caring for psychiatrically ill women, with a focus on some of the issues that were particularly relevant during the pandemic. The most common reasons for consultation on our service are the appropriate, safest use of antidepressants and mood stabilizers during pregnancy, and that continues to be the case.

If there has been one guiding principle in treating perinatal depression during pregnancy, it has been our long-standing, laser-like focus on keeping women emotionally well during pregnancy, and to highlight the importance of this with women during consultations prior to and during pregnancy. Relapse of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy is one the strongest predictors of postpartum depression, and the impact of untreated depression during pregnancy has been described in the literature and over the years in this column. However, where we want to minimize, if possible, severe onset of illness requiring hospitalization or emergent attention considering it may make social distancing and some of the other mitigating factors vis-à-vis COVID-19 more challenging.

Despite the accumulated data over the last 2 decades on the reproductive safety of antidepressants, women continue to have questions about the safety of these medications during pregnancy. Studies show now that many women would prefer, if at all possible, to defer treatment with antidepressants, and so they come to us with questions about their reproductive safety, the potential of switching to nonpharmacologic interventions, and the use of alternative interventions that might be used to treat their underlying mood disorder.

Investigators at the University of British Columbia recently have tried to inform the field with still another look, not at reproductive safety per se, but at risk of relapse of depression if women discontinue those medicines during pregnancy.1 There is a timeliness to this investigation, which was a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that met a priori criteria for inclusion. Since some of our own group’s early work over 15 years ago on relapse of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy,2 which indicated a substantial difference in risk of relapse between women who continued versus who discontinued antidepressants, other investigators have showed the difference in risk for relapse is not as substantial, and that continuation of medication did not appear to mitigate risk for relapse. In fact, in the systematic review, the investigators demonstrated that as a group, maintaining medicine did not appear to confer particular benefit to patients relative to risk for relapse compared to discontinuation of antidepressants.

However, looking more closely, Bayrampour and colleagues note for women with histories of more severe recurrent, major depression, relapse did in fact appear to be greater in women who discontinued compared with those with cases of mild to moderate depression. It is noteworthy that in both our early and later work, and certainly dovetailing with our clinical practice, we have noted severity of illness does not appear to correlate with the actual decisions women ultimately make regarding what they will do with antidepressants. Specifically, some women with very severe illness histories will discontinue antidepressants regardless of their risk for relapse. Alternatively, women with mild to moderate illness will sometimes elect to stay on antidepressant therapy. With all the information that we have about fetal exposure to antidepressants on one hand, the “unknown unknowns” are an understandable concern to both patients and clinicians. Clinicians are faced with the dilemma of how to best counsel women on continuing or discontinuing antidepressants as they plan to conceive or during pregnancy and in the postpartum period.

The literature cited and clinical experience over the last 3 decades suggests rather strongly that there is a relatively low likelihood women with histories of severe recurrent disease will be able to successfully discontinue antidepressants in the absence of relapse. A greater question is, what is the best way to proceed for women who have been on maintenance therapy and had more moderate symptoms?

I am inspired by some of the more recent literature that has tried to elucidate the role of nonpharmacologic interventions such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) in an effort to mitigate risk for depressive relapse in pregnant women who are well with histories of depression. To date, data do not inform the question as to whether MBCT can be used to mitigate risk of depressive relapse in pregnant women who continue or discontinue antidepressants. That research question is actively being studied by several investigators, including ourselves.

Of particular interest is whether the addition of mindfulness practices such as MBCT in treatment could mitigate risk for depressive relapse in pregnant women who continue or discontinue antidepressant treatment, as that would certainly be a no-harm intervention that could mitigate risk even in a lower risk sample of patients. The question of how to “thread the needle” during the pandemic and best approach woman with a history of recurrent major depression on antidepressants is particularly timely and critical.

Regardless, we make clinical decisions collaboratively with patients based on their histories and individual wishes, and perhaps what we have learned over the last 5 months is the use of telemedicine does afford us the opportunity, regardless of the decisions that patients make, to more closely follow the clinical trajectory of women during pregnancy and the postpartum period so that regardless of treatment, we have an opportunity to intervene early when needed and to ascertain changes in clinical status early to mitigate the risk of frank relapse. From a reproductive psychiatric point of view, that is a silver lining with respect to the associated challenges that have come along with the pandemic.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at [email protected].

References

1. J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81(4):19r13134.

2. JAMA. 2006 Feb 1;295(5):499-507.

FDA approves point-of-care COVID-19 antigen test

The BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card (Abbott) is similar in some ways to a home pregnancy test. Clinicians read results on a card – one line for a negative result, two lines for positive.

A health care provider swabs a symptomatic patient’s nose, twirls the sample on a test card with a reagent, and waits approximately 15 minutes for results. No additional equipment is required.

Abbott expects the test to cost about $5.00, the company announced.

Office-based physicians, ED physicians, and school nurses could potentially use the product as a point-of-care test. The FDA granted the test emergency use authorization. It is approved for people suspected of having COVID-19 who are within 7 days of symptom onset.

“This new COVID-19 antigen test is an important addition to available tests because the results can be read in minutes, right off the testing card,” Jeff Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, wrote in a news release. “This means people will know if they have the virus in almost real time.”

“This fits into the testing landscape as a simple, inexpensive test that does not require additional equipment,” Marcus Lynch, PhD, assistant manager of the Health Care Horizon Scanning program at ECRI, told Medscape Medical News when asked to comment. ECRI is an independent, nonprofit organization that reviews and analyses COVID-19 therapeutics and diagnostics.

The test could help with early triage of patients who test positive, perhaps alerting physicians to the need to start COVID-19 therapy, added Lynch, who specializes in immunology and vaccine development. The test also could be useful in low-resource settings.

The FDA included a caveat: antigen tests are generally less sensitive than molecular assays. “Due to the potential for decreased sensitivity compared to molecular assays, negative results from an antigen test may need to be confirmed with a molecular test prior to making treatment decisions,” the agency noted.

Lynch agreed and said that when a patient tests negative, physicians still need to use their clinical judgment on the basis of symptoms and other factors. The test is not designed for population-based screening of asymptomatic people, he added.

Abbott announced plans to make up to 50 million tests available per month in the United States starting in October. The product comes with a free smartphone app that people can use to share results with an employer or with others as needed.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card (Abbott) is similar in some ways to a home pregnancy test. Clinicians read results on a card – one line for a negative result, two lines for positive.

A health care provider swabs a symptomatic patient’s nose, twirls the sample on a test card with a reagent, and waits approximately 15 minutes for results. No additional equipment is required.

Abbott expects the test to cost about $5.00, the company announced.

Office-based physicians, ED physicians, and school nurses could potentially use the product as a point-of-care test. The FDA granted the test emergency use authorization. It is approved for people suspected of having COVID-19 who are within 7 days of symptom onset.

“This new COVID-19 antigen test is an important addition to available tests because the results can be read in minutes, right off the testing card,” Jeff Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, wrote in a news release. “This means people will know if they have the virus in almost real time.”

“This fits into the testing landscape as a simple, inexpensive test that does not require additional equipment,” Marcus Lynch, PhD, assistant manager of the Health Care Horizon Scanning program at ECRI, told Medscape Medical News when asked to comment. ECRI is an independent, nonprofit organization that reviews and analyses COVID-19 therapeutics and diagnostics.

The test could help with early triage of patients who test positive, perhaps alerting physicians to the need to start COVID-19 therapy, added Lynch, who specializes in immunology and vaccine development. The test also could be useful in low-resource settings.

The FDA included a caveat: antigen tests are generally less sensitive than molecular assays. “Due to the potential for decreased sensitivity compared to molecular assays, negative results from an antigen test may need to be confirmed with a molecular test prior to making treatment decisions,” the agency noted.

Lynch agreed and said that when a patient tests negative, physicians still need to use their clinical judgment on the basis of symptoms and other factors. The test is not designed for population-based screening of asymptomatic people, he added.

Abbott announced plans to make up to 50 million tests available per month in the United States starting in October. The product comes with a free smartphone app that people can use to share results with an employer or with others as needed.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card (Abbott) is similar in some ways to a home pregnancy test. Clinicians read results on a card – one line for a negative result, two lines for positive.

A health care provider swabs a symptomatic patient’s nose, twirls the sample on a test card with a reagent, and waits approximately 15 minutes for results. No additional equipment is required.

Abbott expects the test to cost about $5.00, the company announced.

Office-based physicians, ED physicians, and school nurses could potentially use the product as a point-of-care test. The FDA granted the test emergency use authorization. It is approved for people suspected of having COVID-19 who are within 7 days of symptom onset.

“This new COVID-19 antigen test is an important addition to available tests because the results can be read in minutes, right off the testing card,” Jeff Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, wrote in a news release. “This means people will know if they have the virus in almost real time.”

“This fits into the testing landscape as a simple, inexpensive test that does not require additional equipment,” Marcus Lynch, PhD, assistant manager of the Health Care Horizon Scanning program at ECRI, told Medscape Medical News when asked to comment. ECRI is an independent, nonprofit organization that reviews and analyses COVID-19 therapeutics and diagnostics.

The test could help with early triage of patients who test positive, perhaps alerting physicians to the need to start COVID-19 therapy, added Lynch, who specializes in immunology and vaccine development. The test also could be useful in low-resource settings.

The FDA included a caveat: antigen tests are generally less sensitive than molecular assays. “Due to the potential for decreased sensitivity compared to molecular assays, negative results from an antigen test may need to be confirmed with a molecular test prior to making treatment decisions,” the agency noted.

Lynch agreed and said that when a patient tests negative, physicians still need to use their clinical judgment on the basis of symptoms and other factors. The test is not designed for population-based screening of asymptomatic people, he added.

Abbott announced plans to make up to 50 million tests available per month in the United States starting in October. The product comes with a free smartphone app that people can use to share results with an employer or with others as needed.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 vaccine supply will be limited at first, ACIP says

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) yesterday held its third meeting this summer to discuss the vaccines and plan how initial vaccines will be allocated, inasmuch as supplies will likely be limited at first. Vaccines are expected to be more available as production ramps up and as more than one vaccine become available, but vaccine allocation initially will need to take place in phases.

Considerations include first getting the vaccine to individuals who need it the most, such as healthcare personnel and essential workers, as well as those at higher risk for severe illness or death, including the elderly, those with underlying conditions, and certain racial and ethnic minorities. Other factors include storage requirements that might be difficult to meet in certain settings and the fact that both vaccines must be given in two doses.

Vaccine allocation models

The group presented two possible models for allocating initial vaccine supplies.

The first population model considers risk status within each age group on the basis of underlying health conditions and occupational group, with priority given to healthcare personnel (paid or unpaid) and essential workers. The model considers partial reopening and social distancing, expected vaccine efficacy, prevaccination immunity, mortality, and the direct and indirect benefits of vaccination.

In this model, COVID-19 infections and deaths were reduced when healthcare personnel, essential workers, or adults with underlying conditions were vaccinated. There were smaller differences between the groups with respect to the impact of vaccination. Declines in infections were “more modest” and declines in deaths were greater when adults aged 65 years and older were vaccinated in comparison with other age groups.

The second model focused on vaccination of nursing home healthcare personnel and residents. Vaccinating nursing home healthcare personnel reduced infections and deaths more than vaccinating nursing home residents.

In settings such as long-term care facilities and correction facilities, where people gather in groups, cases increase first among staff. The vaccine working group suggests that vaccinating staff may also benefit individuals living in those facilities.

The working group expects that from 15 to 45 million doses of vaccine will be available by the end of December, depending on which vaccine is approved by then or whether both are approved.

Supplies won’t be nearly enough to vaccinate everyone: There are approximately 17 to 20 million healthcare workers in the United States and 60 to 80 million essential workers who do not work in healthcare. More than 100 million adults have underlying medical conditions that put them at higher risk for hospitalization and death, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. And approximately 53 million adults are aged 65 years or older.

The group reviewed promising early data for two vaccines under development.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine, made by Moderna with support from two federal agencies, is moving into phase 3 clinical trials – enrollment into the COVID-19 Efficacy and Safety (COVE) study is ongoing, according to Jacqueline M. Miller, MD, senior vice president and therapeutic area head of infectious diseases. The study’s primary objective will be to determine whether two doses can prevent symptomatic COVID-19, according to an NIH news release.

A second mRNA vaccine, BNT 162b2, made by Pfizer and BioNTech, is entering phase 2/3 trials. Nearly 20% of people enrolled are Black or Hispanic persons, and 4% are Asian persons. The team is also trying to recruit Native American participants, Nicholas Kitchin, MD, senior director in Pfizer’s vaccine clinical research and development group, said in a presentation to the advisory committee.

‘Ultra-cold’ temperatures required for storage

Both vaccines require storage at lower temperatures than is usually needed for vaccines. One vaccine must be distributed and stored at -20° C, and the other must be stored, distributed, and handled at -70° C.

This issue stands out most to ACIP Chair Jose Romero, MD. He says the “ultra-cold” temperatures required for storage and transportation of the vaccines will be a “significant problem” for those in rural areas.

High-risk populations such as meat processors and agricultural workers “may have to wait until we have a more stable vaccine that can be transported and delivered more or less at room temperature,” Romero explained. He is the chief medical officer at the Arkansas Department of Health and is a professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, both in Little Rock.

The advisory committee will meet again on September 22. At that time, they’ll vote on an interim plan for prioritization of the first COVID-19 vaccine.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) yesterday held its third meeting this summer to discuss the vaccines and plan how initial vaccines will be allocated, inasmuch as supplies will likely be limited at first. Vaccines are expected to be more available as production ramps up and as more than one vaccine become available, but vaccine allocation initially will need to take place in phases.

Considerations include first getting the vaccine to individuals who need it the most, such as healthcare personnel and essential workers, as well as those at higher risk for severe illness or death, including the elderly, those with underlying conditions, and certain racial and ethnic minorities. Other factors include storage requirements that might be difficult to meet in certain settings and the fact that both vaccines must be given in two doses.

Vaccine allocation models

The group presented two possible models for allocating initial vaccine supplies.

The first population model considers risk status within each age group on the basis of underlying health conditions and occupational group, with priority given to healthcare personnel (paid or unpaid) and essential workers. The model considers partial reopening and social distancing, expected vaccine efficacy, prevaccination immunity, mortality, and the direct and indirect benefits of vaccination.

In this model, COVID-19 infections and deaths were reduced when healthcare personnel, essential workers, or adults with underlying conditions were vaccinated. There were smaller differences between the groups with respect to the impact of vaccination. Declines in infections were “more modest” and declines in deaths were greater when adults aged 65 years and older were vaccinated in comparison with other age groups.

The second model focused on vaccination of nursing home healthcare personnel and residents. Vaccinating nursing home healthcare personnel reduced infections and deaths more than vaccinating nursing home residents.

In settings such as long-term care facilities and correction facilities, where people gather in groups, cases increase first among staff. The vaccine working group suggests that vaccinating staff may also benefit individuals living in those facilities.

The working group expects that from 15 to 45 million doses of vaccine will be available by the end of December, depending on which vaccine is approved by then or whether both are approved.

Supplies won’t be nearly enough to vaccinate everyone: There are approximately 17 to 20 million healthcare workers in the United States and 60 to 80 million essential workers who do not work in healthcare. More than 100 million adults have underlying medical conditions that put them at higher risk for hospitalization and death, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. And approximately 53 million adults are aged 65 years or older.

The group reviewed promising early data for two vaccines under development.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine, made by Moderna with support from two federal agencies, is moving into phase 3 clinical trials – enrollment into the COVID-19 Efficacy and Safety (COVE) study is ongoing, according to Jacqueline M. Miller, MD, senior vice president and therapeutic area head of infectious diseases. The study’s primary objective will be to determine whether two doses can prevent symptomatic COVID-19, according to an NIH news release.

A second mRNA vaccine, BNT 162b2, made by Pfizer and BioNTech, is entering phase 2/3 trials. Nearly 20% of people enrolled are Black or Hispanic persons, and 4% are Asian persons. The team is also trying to recruit Native American participants, Nicholas Kitchin, MD, senior director in Pfizer’s vaccine clinical research and development group, said in a presentation to the advisory committee.

‘Ultra-cold’ temperatures required for storage

Both vaccines require storage at lower temperatures than is usually needed for vaccines. One vaccine must be distributed and stored at -20° C, and the other must be stored, distributed, and handled at -70° C.

This issue stands out most to ACIP Chair Jose Romero, MD. He says the “ultra-cold” temperatures required for storage and transportation of the vaccines will be a “significant problem” for those in rural areas.

High-risk populations such as meat processors and agricultural workers “may have to wait until we have a more stable vaccine that can be transported and delivered more or less at room temperature,” Romero explained. He is the chief medical officer at the Arkansas Department of Health and is a professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, both in Little Rock.

The advisory committee will meet again on September 22. At that time, they’ll vote on an interim plan for prioritization of the first COVID-19 vaccine.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) yesterday held its third meeting this summer to discuss the vaccines and plan how initial vaccines will be allocated, inasmuch as supplies will likely be limited at first. Vaccines are expected to be more available as production ramps up and as more than one vaccine become available, but vaccine allocation initially will need to take place in phases.

Considerations include first getting the vaccine to individuals who need it the most, such as healthcare personnel and essential workers, as well as those at higher risk for severe illness or death, including the elderly, those with underlying conditions, and certain racial and ethnic minorities. Other factors include storage requirements that might be difficult to meet in certain settings and the fact that both vaccines must be given in two doses.

Vaccine allocation models

The group presented two possible models for allocating initial vaccine supplies.

The first population model considers risk status within each age group on the basis of underlying health conditions and occupational group, with priority given to healthcare personnel (paid or unpaid) and essential workers. The model considers partial reopening and social distancing, expected vaccine efficacy, prevaccination immunity, mortality, and the direct and indirect benefits of vaccination.

In this model, COVID-19 infections and deaths were reduced when healthcare personnel, essential workers, or adults with underlying conditions were vaccinated. There were smaller differences between the groups with respect to the impact of vaccination. Declines in infections were “more modest” and declines in deaths were greater when adults aged 65 years and older were vaccinated in comparison with other age groups.

The second model focused on vaccination of nursing home healthcare personnel and residents. Vaccinating nursing home healthcare personnel reduced infections and deaths more than vaccinating nursing home residents.

In settings such as long-term care facilities and correction facilities, where people gather in groups, cases increase first among staff. The vaccine working group suggests that vaccinating staff may also benefit individuals living in those facilities.

The working group expects that from 15 to 45 million doses of vaccine will be available by the end of December, depending on which vaccine is approved by then or whether both are approved.

Supplies won’t be nearly enough to vaccinate everyone: There are approximately 17 to 20 million healthcare workers in the United States and 60 to 80 million essential workers who do not work in healthcare. More than 100 million adults have underlying medical conditions that put them at higher risk for hospitalization and death, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. And approximately 53 million adults are aged 65 years or older.

The group reviewed promising early data for two vaccines under development.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine, made by Moderna with support from two federal agencies, is moving into phase 3 clinical trials – enrollment into the COVID-19 Efficacy and Safety (COVE) study is ongoing, according to Jacqueline M. Miller, MD, senior vice president and therapeutic area head of infectious diseases. The study’s primary objective will be to determine whether two doses can prevent symptomatic COVID-19, according to an NIH news release.

A second mRNA vaccine, BNT 162b2, made by Pfizer and BioNTech, is entering phase 2/3 trials. Nearly 20% of people enrolled are Black or Hispanic persons, and 4% are Asian persons. The team is also trying to recruit Native American participants, Nicholas Kitchin, MD, senior director in Pfizer’s vaccine clinical research and development group, said in a presentation to the advisory committee.

‘Ultra-cold’ temperatures required for storage

Both vaccines require storage at lower temperatures than is usually needed for vaccines. One vaccine must be distributed and stored at -20° C, and the other must be stored, distributed, and handled at -70° C.

This issue stands out most to ACIP Chair Jose Romero, MD. He says the “ultra-cold” temperatures required for storage and transportation of the vaccines will be a “significant problem” for those in rural areas.

High-risk populations such as meat processors and agricultural workers “may have to wait until we have a more stable vaccine that can be transported and delivered more or less at room temperature,” Romero explained. He is the chief medical officer at the Arkansas Department of Health and is a professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, both in Little Rock.

The advisory committee will meet again on September 22. At that time, they’ll vote on an interim plan for prioritization of the first COVID-19 vaccine.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anorexia may stunt growth in teenage girls

Anorexia nervosa may stunt the growth and impact the future height of teenage girls, according to data from 255 adolescents.

Illness and malnutrition during critical child and adolescent growth periods may limit adult height, but the effect of anorexia nervosa (AN) on growth impairment and adult height has not been well studied, wrote Dalit Modan-Moses, MD, of Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Tel Aviv, and colleagues.

Individuals with AN lose an unhealthy amount of weight on purpose through dieting, sometimes along with excessive exercise, binge eating, and/or purging, and because the condition occurs mainly in adolescents, the subsequent malnutrition may impact growth and adult height, they said.

In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, the researchers reviewed data from 255 adolescent girls who were hospitalized for AN at an average age of 15 years. They measured the girls’ height at the time of hospital admission, discharge, and at adulthood. The participants were followed in an outpatient clinic after hospital discharge with biweekly visits for the first 2 months, monthly visits for the next 4 months, and every 3 months until they reached 18 years of age. The average body mass index of the patients at the time of admission was 16 kg/m2 and the average duration of illness was 2 years. Of the 225 patients, 174 had a diagnosis of restrictive type anorexia nervosa and 81 had binge-purge type.

The midparental target height was based on an average of the parents’ heights and subtracting 6.5 cm. The main outcome of adult height was significantly shorter than expected (P = .006) based on midparental target height. Although the patients’ heights increased significantly during hospitalization, from 158 cm to 159 cm (P < .001), “the change in height-SDS [standard deviation scores] was not significant and height-SDS at discharge remained significantly lower compared to the expected in a normal population,” the researchers noted.

Although premorbid height SDS in the study population were similar to normal adolescents, the height-SDS measurements at hospital admission, discharge, and adulthood were significantly lower than expected (–0.36, –0.34, and –0.29, respectively).

Independent predictors of height improvement from hospital admission to adulthood were patient age and bone age at the time of hospital admission, linear growth during hospitalization, and change in luteinizing hormone (LH) during hospitalization, based on a stepwise forward linear regression analysis.

The findings were limited by several factors including the inpatient study population, which may limit the generalizability to patients with less severe illness, as well as incomplete data on LH levels, which were undetectable in 19% of the patients, the researchers noted. However, the study is among the largest to describe growth in female AN patients and included data on linear growth and LH not described in other studies, they said.

“Our study is unique in presenting complete growth data (premorbid, admission, discharge, AH) as well as target height, laboratory results and bone age data in a large cohort of adolescent females with AN,” they wrote.

The findings not only support the need for early intervention in patients with AN and the need for long-term weight gain to achieve catch-up growth, but also may apply to management of malnutrition in adolescents with chronic diseases such as cystic fibrosis and inflammatory bowel disease, they concluded.

“Anorexia nervosa is a prevalent and severe disease with multiple short- and long-term complications. Still, despite the large body of research regarding this disease, data regarding growth patterns and final height of patients was incomplete and inconclusive, Dr. Modan-Moses said in an interview. The findings were not surprising, and were consistent with the results of a previous study the researchers conducted (Modan-Moses D et al. PLoS One. 2012 Sept 18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045504).

“Our first study was retrospective, and many pertinent parameters influencing growth were not available,” Dr. Modan-Moses noted. “The current study was designed to include a comprehensive evaluation including examination of the patients to document how far advanced in puberty they were, measuring height of parents in order to document the genetic height potential, bone age x-rays of the hand to determine the growth potential at the time of admission to hospitalization, and laboratory tests. This design enabled us to validate the results of our first study so that our findings are now more scientifically grounded,” she said.

“Our findings imply that in many cases there is a considerable delay in the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, so that by the time of diagnosis significant growth delay has already occurred. Our findings also imply that damage caused by this delay in diagnosis was in part irreversible, even with intensive treatment,” Dr. Modan-Moses emphasized. On a clinical level, the results highlight the “importance of careful monitoring of height and weight by pediatricians, and early detection and early initiation of treatment of anorexia nervosa in adolescents with long-term efforts to improve and accelerate weight gain in order to prevent complications,” she said. “Research is needed to better define factors affecting catch-up growth (that is improved growth with correction of the height deficit observed at the time of admission) and to determine accordingly optimal treatment plans,” Dr. Modan-Moses added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Modan-Moses D et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Aug 20. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa510.

Anorexia nervosa may stunt the growth and impact the future height of teenage girls, according to data from 255 adolescents.

Illness and malnutrition during critical child and adolescent growth periods may limit adult height, but the effect of anorexia nervosa (AN) on growth impairment and adult height has not been well studied, wrote Dalit Modan-Moses, MD, of Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Tel Aviv, and colleagues.

Individuals with AN lose an unhealthy amount of weight on purpose through dieting, sometimes along with excessive exercise, binge eating, and/or purging, and because the condition occurs mainly in adolescents, the subsequent malnutrition may impact growth and adult height, they said.

In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, the researchers reviewed data from 255 adolescent girls who were hospitalized for AN at an average age of 15 years. They measured the girls’ height at the time of hospital admission, discharge, and at adulthood. The participants were followed in an outpatient clinic after hospital discharge with biweekly visits for the first 2 months, monthly visits for the next 4 months, and every 3 months until they reached 18 years of age. The average body mass index of the patients at the time of admission was 16 kg/m2 and the average duration of illness was 2 years. Of the 225 patients, 174 had a diagnosis of restrictive type anorexia nervosa and 81 had binge-purge type.

The midparental target height was based on an average of the parents’ heights and subtracting 6.5 cm. The main outcome of adult height was significantly shorter than expected (P = .006) based on midparental target height. Although the patients’ heights increased significantly during hospitalization, from 158 cm to 159 cm (P < .001), “the change in height-SDS [standard deviation scores] was not significant and height-SDS at discharge remained significantly lower compared to the expected in a normal population,” the researchers noted.

Although premorbid height SDS in the study population were similar to normal adolescents, the height-SDS measurements at hospital admission, discharge, and adulthood were significantly lower than expected (–0.36, –0.34, and –0.29, respectively).

Independent predictors of height improvement from hospital admission to adulthood were patient age and bone age at the time of hospital admission, linear growth during hospitalization, and change in luteinizing hormone (LH) during hospitalization, based on a stepwise forward linear regression analysis.

The findings were limited by several factors including the inpatient study population, which may limit the generalizability to patients with less severe illness, as well as incomplete data on LH levels, which were undetectable in 19% of the patients, the researchers noted. However, the study is among the largest to describe growth in female AN patients and included data on linear growth and LH not described in other studies, they said.

“Our study is unique in presenting complete growth data (premorbid, admission, discharge, AH) as well as target height, laboratory results and bone age data in a large cohort of adolescent females with AN,” they wrote.

The findings not only support the need for early intervention in patients with AN and the need for long-term weight gain to achieve catch-up growth, but also may apply to management of malnutrition in adolescents with chronic diseases such as cystic fibrosis and inflammatory bowel disease, they concluded.

“Anorexia nervosa is a prevalent and severe disease with multiple short- and long-term complications. Still, despite the large body of research regarding this disease, data regarding growth patterns and final height of patients was incomplete and inconclusive, Dr. Modan-Moses said in an interview. The findings were not surprising, and were consistent with the results of a previous study the researchers conducted (Modan-Moses D et al. PLoS One. 2012 Sept 18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045504).

“Our first study was retrospective, and many pertinent parameters influencing growth were not available,” Dr. Modan-Moses noted. “The current study was designed to include a comprehensive evaluation including examination of the patients to document how far advanced in puberty they were, measuring height of parents in order to document the genetic height potential, bone age x-rays of the hand to determine the growth potential at the time of admission to hospitalization, and laboratory tests. This design enabled us to validate the results of our first study so that our findings are now more scientifically grounded,” she said.

“Our findings imply that in many cases there is a considerable delay in the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, so that by the time of diagnosis significant growth delay has already occurred. Our findings also imply that damage caused by this delay in diagnosis was in part irreversible, even with intensive treatment,” Dr. Modan-Moses emphasized. On a clinical level, the results highlight the “importance of careful monitoring of height and weight by pediatricians, and early detection and early initiation of treatment of anorexia nervosa in adolescents with long-term efforts to improve and accelerate weight gain in order to prevent complications,” she said. “Research is needed to better define factors affecting catch-up growth (that is improved growth with correction of the height deficit observed at the time of admission) and to determine accordingly optimal treatment plans,” Dr. Modan-Moses added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Modan-Moses D et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Aug 20. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa510.

Anorexia nervosa may stunt the growth and impact the future height of teenage girls, according to data from 255 adolescents.

Illness and malnutrition during critical child and adolescent growth periods may limit adult height, but the effect of anorexia nervosa (AN) on growth impairment and adult height has not been well studied, wrote Dalit Modan-Moses, MD, of Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Tel Aviv, and colleagues.

Individuals with AN lose an unhealthy amount of weight on purpose through dieting, sometimes along with excessive exercise, binge eating, and/or purging, and because the condition occurs mainly in adolescents, the subsequent malnutrition may impact growth and adult height, they said.

In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, the researchers reviewed data from 255 adolescent girls who were hospitalized for AN at an average age of 15 years. They measured the girls’ height at the time of hospital admission, discharge, and at adulthood. The participants were followed in an outpatient clinic after hospital discharge with biweekly visits for the first 2 months, monthly visits for the next 4 months, and every 3 months until they reached 18 years of age. The average body mass index of the patients at the time of admission was 16 kg/m2 and the average duration of illness was 2 years. Of the 225 patients, 174 had a diagnosis of restrictive type anorexia nervosa and 81 had binge-purge type.

The midparental target height was based on an average of the parents’ heights and subtracting 6.5 cm. The main outcome of adult height was significantly shorter than expected (P = .006) based on midparental target height. Although the patients’ heights increased significantly during hospitalization, from 158 cm to 159 cm (P < .001), “the change in height-SDS [standard deviation scores] was not significant and height-SDS at discharge remained significantly lower compared to the expected in a normal population,” the researchers noted.

Although premorbid height SDS in the study population were similar to normal adolescents, the height-SDS measurements at hospital admission, discharge, and adulthood were significantly lower than expected (–0.36, –0.34, and –0.29, respectively).

Independent predictors of height improvement from hospital admission to adulthood were patient age and bone age at the time of hospital admission, linear growth during hospitalization, and change in luteinizing hormone (LH) during hospitalization, based on a stepwise forward linear regression analysis.

The findings were limited by several factors including the inpatient study population, which may limit the generalizability to patients with less severe illness, as well as incomplete data on LH levels, which were undetectable in 19% of the patients, the researchers noted. However, the study is among the largest to describe growth in female AN patients and included data on linear growth and LH not described in other studies, they said.

“Our study is unique in presenting complete growth data (premorbid, admission, discharge, AH) as well as target height, laboratory results and bone age data in a large cohort of adolescent females with AN,” they wrote.

The findings not only support the need for early intervention in patients with AN and the need for long-term weight gain to achieve catch-up growth, but also may apply to management of malnutrition in adolescents with chronic diseases such as cystic fibrosis and inflammatory bowel disease, they concluded.

“Anorexia nervosa is a prevalent and severe disease with multiple short- and long-term complications. Still, despite the large body of research regarding this disease, data regarding growth patterns and final height of patients was incomplete and inconclusive, Dr. Modan-Moses said in an interview. The findings were not surprising, and were consistent with the results of a previous study the researchers conducted (Modan-Moses D et al. PLoS One. 2012 Sept 18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045504).

“Our first study was retrospective, and many pertinent parameters influencing growth were not available,” Dr. Modan-Moses noted. “The current study was designed to include a comprehensive evaluation including examination of the patients to document how far advanced in puberty they were, measuring height of parents in order to document the genetic height potential, bone age x-rays of the hand to determine the growth potential at the time of admission to hospitalization, and laboratory tests. This design enabled us to validate the results of our first study so that our findings are now more scientifically grounded,” she said.

“Our findings imply that in many cases there is a considerable delay in the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, so that by the time of diagnosis significant growth delay has already occurred. Our findings also imply that damage caused by this delay in diagnosis was in part irreversible, even with intensive treatment,” Dr. Modan-Moses emphasized. On a clinical level, the results highlight the “importance of careful monitoring of height and weight by pediatricians, and early detection and early initiation of treatment of anorexia nervosa in adolescents with long-term efforts to improve and accelerate weight gain in order to prevent complications,” she said. “Research is needed to better define factors affecting catch-up growth (that is improved growth with correction of the height deficit observed at the time of admission) and to determine accordingly optimal treatment plans,” Dr. Modan-Moses added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Modan-Moses D et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Aug 20. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa510.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM

Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in kids tied to local rates

As communities wrestle with the decision to send children back to school or opt for distance learning, a key question is how many children are likely to have asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections.

“The strong association between prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in children who are asymptomatic and contemporaneous weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population ... provides a simple means for institutions to estimate local pediatric asymptomatic prevalence from the publicly available Johns Hopkins University database,” researchers say in an article published online August 25 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Ana Marija Sola, BS, a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues examined the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among 33,041 children who underwent routine testing in April and May when hospitals resumed elective medical and surgical care. The hospitals performed reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction tests for SARS-CoV-2 RNA before surgery, clinic visits, or hospital admissions. Pediatric otolaryngologists reported the prevalence data through May 29 as part of a quality improvement project.

In all, 250 patients tested positive for the virus, for an overall prevalence of 0.65%. Across 25 geographic areas, the prevalence ranged from 0% to 2.2%. By region, prevalence was highest in the Northeast, at 0.90%, and the Midwest, at 0.87%; prevalence was lower in the West, at 0.59%, and the South, at 0.52%.

To get a sense of how those rates compared with overall rates in the same geographic areas, the researchers used the Johns Hopkins University confirmed cases database to calculate the average weekly incidence of COVID-19 for the entire population for each geographic area.