User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Low-dose aspirin linked to lower dementia risk in some

, according to a retrospective analysis of two large cohorts. The association with all-cause dementia was weak, but much more pronounced in subjects with coronary heart disease.

The results underscore that individuals with cardiovascular disease risk factors should be prescribed LDASA, and they should be encouraged to be compliant. The study differed from previous observational and randomized, controlled trials, which yielded mixed results. Many looked at individuals older than age 65. The pathological changes associated with dementia may occur up to 2 decades before symptom onset, and it appears that LDASA cannot counter cognitive decline after a diagnosis is made. “The use of LDASA at this age may be already too late,” said Thi Ngoc Mai Nguyen, a PhD student at Network Aging Research, Heidelberg University, Germany. She presented the results at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Previous studies also included individuals using LDASA to prevent cardiovascular disease, and they didn’t always adjust for these risk factors. The current work used two large databases, UK Biobank and ESTHER, with a follow-up time of over 10 years for both. “We were able to balance out the distribution of measured baseline covariates (to be) similar between LDASA users and nonusers, and thus, we were able to adjust for confounders more comprehensively,” said Ms. Nguyen.

Not yet a definitive answer

Although the findings are promising, Ms. Nguyen noted that the study is not the final word. “Residual confounding is possible, and causation cannot be tested. The only way to answer this is to have clinical trials with at least 10 years of follow-up,” said Ms. Nguyen. She plans to conduct similar studies in non-White populations, and also to examine whether LDASA can help preserve cognitive function in middle-age adults.

The study is interesting, said Claire Sexton, DPhil, who was asked to comment, but she suggested that it is not practice changing. “There is not evidence from the dementia science perspective that should go against whatever the recommendations are for cardiovascular risk,” said Dr. Sexton, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association. “I don’t think this study alone can provide a definitive answer on low-dose aspirin and its association with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, but it’s an important addition to the literature,” she added.

Meta-analysis data

The researchers examined two prospective cohort studies, and combined them into a meta-analysis. It included the ESTHER cohort from Saarland, Germany, with 5,258 individuals and 14.3 years of follow-up, and the UK Biobank cohort, with 305,394 individuals and 11.6 years of follow-up. Subjects selected for analysis were 55 years old or older.

The meta-analysis showed no significant association between LDASA use and reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but there was an association between LDASA use and all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 0.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-0.99).

There were no sex differences with respect to Alzheimer’s dementia, but in males, LDASA was associated with lower risk of vascular dementia (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.93) and all-cause dementia (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.83-0.92). However, in females, LDASA was tied to greater risk of both vascular dementia (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.24) and all-cause dementia (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.13).

The strongest association between LDASA and reduced dementia risk was found in subjects with coronary heart disease (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.59-0.80).

The researchers also used UK Biobank primary care data to analyze associations between longer use of LDASA and reduced dementia risk. Those who used LDASA for 0-5 years were at a higher than average risk of all-cause dementia (HR, 2.80; 95% CI, 2.48-3.16), Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.84-2.77), and vascular dementia (HR, 3.79; 95% CI, 3.17-4.53). Long-term LDASA users, defined as 10 years or longer, had a lower risk of all-cause dementia (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.47-0.56), Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.51-0.68), and vascular dementia (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.42-0.56).

Dr. Nguyen and Dr. Sexton have no relevant financial disclosures.

, according to a retrospective analysis of two large cohorts. The association with all-cause dementia was weak, but much more pronounced in subjects with coronary heart disease.

The results underscore that individuals with cardiovascular disease risk factors should be prescribed LDASA, and they should be encouraged to be compliant. The study differed from previous observational and randomized, controlled trials, which yielded mixed results. Many looked at individuals older than age 65. The pathological changes associated with dementia may occur up to 2 decades before symptom onset, and it appears that LDASA cannot counter cognitive decline after a diagnosis is made. “The use of LDASA at this age may be already too late,” said Thi Ngoc Mai Nguyen, a PhD student at Network Aging Research, Heidelberg University, Germany. She presented the results at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Previous studies also included individuals using LDASA to prevent cardiovascular disease, and they didn’t always adjust for these risk factors. The current work used two large databases, UK Biobank and ESTHER, with a follow-up time of over 10 years for both. “We were able to balance out the distribution of measured baseline covariates (to be) similar between LDASA users and nonusers, and thus, we were able to adjust for confounders more comprehensively,” said Ms. Nguyen.

Not yet a definitive answer

Although the findings are promising, Ms. Nguyen noted that the study is not the final word. “Residual confounding is possible, and causation cannot be tested. The only way to answer this is to have clinical trials with at least 10 years of follow-up,” said Ms. Nguyen. She plans to conduct similar studies in non-White populations, and also to examine whether LDASA can help preserve cognitive function in middle-age adults.

The study is interesting, said Claire Sexton, DPhil, who was asked to comment, but she suggested that it is not practice changing. “There is not evidence from the dementia science perspective that should go against whatever the recommendations are for cardiovascular risk,” said Dr. Sexton, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association. “I don’t think this study alone can provide a definitive answer on low-dose aspirin and its association with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, but it’s an important addition to the literature,” she added.

Meta-analysis data

The researchers examined two prospective cohort studies, and combined them into a meta-analysis. It included the ESTHER cohort from Saarland, Germany, with 5,258 individuals and 14.3 years of follow-up, and the UK Biobank cohort, with 305,394 individuals and 11.6 years of follow-up. Subjects selected for analysis were 55 years old or older.

The meta-analysis showed no significant association between LDASA use and reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but there was an association between LDASA use and all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 0.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-0.99).

There were no sex differences with respect to Alzheimer’s dementia, but in males, LDASA was associated with lower risk of vascular dementia (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.93) and all-cause dementia (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.83-0.92). However, in females, LDASA was tied to greater risk of both vascular dementia (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.24) and all-cause dementia (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.13).

The strongest association between LDASA and reduced dementia risk was found in subjects with coronary heart disease (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.59-0.80).

The researchers also used UK Biobank primary care data to analyze associations between longer use of LDASA and reduced dementia risk. Those who used LDASA for 0-5 years were at a higher than average risk of all-cause dementia (HR, 2.80; 95% CI, 2.48-3.16), Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.84-2.77), and vascular dementia (HR, 3.79; 95% CI, 3.17-4.53). Long-term LDASA users, defined as 10 years or longer, had a lower risk of all-cause dementia (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.47-0.56), Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.51-0.68), and vascular dementia (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.42-0.56).

Dr. Nguyen and Dr. Sexton have no relevant financial disclosures.

, according to a retrospective analysis of two large cohorts. The association with all-cause dementia was weak, but much more pronounced in subjects with coronary heart disease.

The results underscore that individuals with cardiovascular disease risk factors should be prescribed LDASA, and they should be encouraged to be compliant. The study differed from previous observational and randomized, controlled trials, which yielded mixed results. Many looked at individuals older than age 65. The pathological changes associated with dementia may occur up to 2 decades before symptom onset, and it appears that LDASA cannot counter cognitive decline after a diagnosis is made. “The use of LDASA at this age may be already too late,” said Thi Ngoc Mai Nguyen, a PhD student at Network Aging Research, Heidelberg University, Germany. She presented the results at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Previous studies also included individuals using LDASA to prevent cardiovascular disease, and they didn’t always adjust for these risk factors. The current work used two large databases, UK Biobank and ESTHER, with a follow-up time of over 10 years for both. “We were able to balance out the distribution of measured baseline covariates (to be) similar between LDASA users and nonusers, and thus, we were able to adjust for confounders more comprehensively,” said Ms. Nguyen.

Not yet a definitive answer

Although the findings are promising, Ms. Nguyen noted that the study is not the final word. “Residual confounding is possible, and causation cannot be tested. The only way to answer this is to have clinical trials with at least 10 years of follow-up,” said Ms. Nguyen. She plans to conduct similar studies in non-White populations, and also to examine whether LDASA can help preserve cognitive function in middle-age adults.

The study is interesting, said Claire Sexton, DPhil, who was asked to comment, but she suggested that it is not practice changing. “There is not evidence from the dementia science perspective that should go against whatever the recommendations are for cardiovascular risk,” said Dr. Sexton, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association. “I don’t think this study alone can provide a definitive answer on low-dose aspirin and its association with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, but it’s an important addition to the literature,” she added.

Meta-analysis data

The researchers examined two prospective cohort studies, and combined them into a meta-analysis. It included the ESTHER cohort from Saarland, Germany, with 5,258 individuals and 14.3 years of follow-up, and the UK Biobank cohort, with 305,394 individuals and 11.6 years of follow-up. Subjects selected for analysis were 55 years old or older.

The meta-analysis showed no significant association between LDASA use and reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but there was an association between LDASA use and all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 0.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-0.99).

There were no sex differences with respect to Alzheimer’s dementia, but in males, LDASA was associated with lower risk of vascular dementia (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.79-0.93) and all-cause dementia (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.83-0.92). However, in females, LDASA was tied to greater risk of both vascular dementia (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.24) and all-cause dementia (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.13).

The strongest association between LDASA and reduced dementia risk was found in subjects with coronary heart disease (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.59-0.80).

The researchers also used UK Biobank primary care data to analyze associations between longer use of LDASA and reduced dementia risk. Those who used LDASA for 0-5 years were at a higher than average risk of all-cause dementia (HR, 2.80; 95% CI, 2.48-3.16), Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.84-2.77), and vascular dementia (HR, 3.79; 95% CI, 3.17-4.53). Long-term LDASA users, defined as 10 years or longer, had a lower risk of all-cause dementia (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.47-0.56), Alzheimer’s disease (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.51-0.68), and vascular dementia (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.42-0.56).

Dr. Nguyen and Dr. Sexton have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AAIC 2021

COVID-19: Delta variant is raising the stakes

Empathetic conversations with unvaccinated people desperately needed

Like many colleagues, I have been working to change the minds and behaviors of acquaintances and patients who are opting to forgo a COVID vaccine. The large numbers of these unvaccinated Americans, combined with the surging Delta coronavirus variant, are endangering the health of us all.

When I spoke with the 22-year-old daughter of a family friend about what was holding her back, she told me that she would “never” get vaccinated. I shared my vaccination experience and told her that, except for a sore arm both times for a day, I felt no side effects. Likewise, I said, all of my adult family members are vaccinated, and everyone is fine. She was neither moved nor convinced.

Finally, I asked her whether she attended school (knowing that she was a college graduate), and she said “yes.” So I told her that all 50 states require children attending public schools to be vaccinated for diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, polio, and the chickenpox – with certain religious, philosophical, and medical exemptions. Her response was simple: “I didn’t know that. Anyway, my parents were in charge.” Suddenly, her thinking shifted. “You’re right,” she said. She got a COVID shot the next day. Success for me.

When I asked another acquaintance whether he’d been vaccinated, he said he’d heard people were getting very sick from the vaccine – and was going to wait. Another gentleman I spoke with said that, at age 45, he was healthy. Besides, he added, he “doesn’t get sick.” When I asked another acquaintance about her vaccination status, her retort was that this was none of my business. So far, I’m batting about .300.

But as a physician, I believe that we – and other health care providers – must continue to encourage the people in our lives to care for themselves and others by getting vaccinated. One concrete step advised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is to help people make an appointment for a shot. Some sites no longer require appointments, and New York City, for example, offers in-home vaccinations to all NYC residents.

Also, NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Aug. 3 the “Key to NYC Pass,” which he called a “first-in-the-nation approach” to vaccination. Under this new policy, vaccine-eligible people aged 12 and older in New York City will need to prove with a vaccination card, an app, or an Excelsior Pass that they have received at least one dose of vaccine before participating in indoor venues such as restaurants, bars, gyms, and movie theaters within the city. Mayor de Blasio said the new initiative, which is still being finalized, will be phased in starting the week of Aug. 16. I see this as a major public health measure that will keep people healthy – and get them vaccinated.

The medical community should support this move by the city of New York and encourage people to follow CDC guidance on wearing face coverings in public settings, especially schools. New research shows that physicians continue to be among the most trusted sources of vaccine-related information.

Another strategy we might use is to point to the longtime practices of surgeons. We could ask: Why do surgeons wear face masks in the operating room? For years, these coverings have been used to protect patients from the nasal and oral bacteria generated by operating room staff. Likewise, we can tell those who remain on the fence that, by wearing face masks, we are protecting others from all variants, but specifically from Delta – which the CDC now says can be transmitted by people who are fully vaccinated.

Why did the CDC lift face mask guidance for fully vaccinated people in indoor spaces in May? It was clear to me and other colleagues back then that this was not a good idea. Despite that guidance, I continued to wear a mask in public places and advised anyone who would listen to do the same.

The development of vaccines in the 20th and 21st centuries has saved millions of lives. The World Health Organization reports that 4 million to 5 million lives a year are saved by immunizations. In addition, research shows that, before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, vaccinations led to the eradication of smallpox and polio, and a 74% drop in measles-related deaths between 2004 and 2014.

Protecting the most vulnerable

With COVID cases surging, particularly in parts of the South and Midwest, I am concerned about children under age 12 who do not yet qualify for a vaccine. Certainly, unvaccinated parents could spread the virus to their young children, and unvaccinated children could transmit the illness to immediate and extended family. Now that the CDC has said that there is a risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated people in areas with high community transmission, should we worry about unvaccinated young children with vaccinated parents? I recently spoke with James C. Fagin, MD, a board-certified pediatrician and immunologist, to get his views on this issue.

Dr. Fagin, who is retired, said he is in complete agreement with the Food and Drug Administration when it comes to approving medications for children. However, given the seriousness of the pandemic and the need to get our children back to in-person learning, he would like to see the approval process safely expedited. Large numbers of unvaccinated people increase the pool for the Delta variant and could increase the likelihood of a new variant that is more resistant to the vaccines, said Dr. Fagin, former chief of academic pediatrics at North Shore University Hospital and a former faculty member in the allergy/immunology division of Cohen Children’s Medical Center, both in New York.

Meanwhile, I agree with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations that children, teachers, and school staff and other adults in school settings should wear masks regardless of vaccination status. Kids adjust well to masks – as my grandchildren and their friends have.

The bottom line is that we need to get as many people as possible vaccinated as soon as possible, and while doing so, we must continue to wear face coverings in public spaces. As clinicians, we have a special responsibility to do all that we can to change minds – and behaviors.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist who has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

Empathetic conversations with unvaccinated people desperately needed

Empathetic conversations with unvaccinated people desperately needed

Like many colleagues, I have been working to change the minds and behaviors of acquaintances and patients who are opting to forgo a COVID vaccine. The large numbers of these unvaccinated Americans, combined with the surging Delta coronavirus variant, are endangering the health of us all.

When I spoke with the 22-year-old daughter of a family friend about what was holding her back, she told me that she would “never” get vaccinated. I shared my vaccination experience and told her that, except for a sore arm both times for a day, I felt no side effects. Likewise, I said, all of my adult family members are vaccinated, and everyone is fine. She was neither moved nor convinced.

Finally, I asked her whether she attended school (knowing that she was a college graduate), and she said “yes.” So I told her that all 50 states require children attending public schools to be vaccinated for diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, polio, and the chickenpox – with certain religious, philosophical, and medical exemptions. Her response was simple: “I didn’t know that. Anyway, my parents were in charge.” Suddenly, her thinking shifted. “You’re right,” she said. She got a COVID shot the next day. Success for me.

When I asked another acquaintance whether he’d been vaccinated, he said he’d heard people were getting very sick from the vaccine – and was going to wait. Another gentleman I spoke with said that, at age 45, he was healthy. Besides, he added, he “doesn’t get sick.” When I asked another acquaintance about her vaccination status, her retort was that this was none of my business. So far, I’m batting about .300.

But as a physician, I believe that we – and other health care providers – must continue to encourage the people in our lives to care for themselves and others by getting vaccinated. One concrete step advised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is to help people make an appointment for a shot. Some sites no longer require appointments, and New York City, for example, offers in-home vaccinations to all NYC residents.

Also, NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Aug. 3 the “Key to NYC Pass,” which he called a “first-in-the-nation approach” to vaccination. Under this new policy, vaccine-eligible people aged 12 and older in New York City will need to prove with a vaccination card, an app, or an Excelsior Pass that they have received at least one dose of vaccine before participating in indoor venues such as restaurants, bars, gyms, and movie theaters within the city. Mayor de Blasio said the new initiative, which is still being finalized, will be phased in starting the week of Aug. 16. I see this as a major public health measure that will keep people healthy – and get them vaccinated.

The medical community should support this move by the city of New York and encourage people to follow CDC guidance on wearing face coverings in public settings, especially schools. New research shows that physicians continue to be among the most trusted sources of vaccine-related information.

Another strategy we might use is to point to the longtime practices of surgeons. We could ask: Why do surgeons wear face masks in the operating room? For years, these coverings have been used to protect patients from the nasal and oral bacteria generated by operating room staff. Likewise, we can tell those who remain on the fence that, by wearing face masks, we are protecting others from all variants, but specifically from Delta – which the CDC now says can be transmitted by people who are fully vaccinated.

Why did the CDC lift face mask guidance for fully vaccinated people in indoor spaces in May? It was clear to me and other colleagues back then that this was not a good idea. Despite that guidance, I continued to wear a mask in public places and advised anyone who would listen to do the same.

The development of vaccines in the 20th and 21st centuries has saved millions of lives. The World Health Organization reports that 4 million to 5 million lives a year are saved by immunizations. In addition, research shows that, before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, vaccinations led to the eradication of smallpox and polio, and a 74% drop in measles-related deaths between 2004 and 2014.

Protecting the most vulnerable

With COVID cases surging, particularly in parts of the South and Midwest, I am concerned about children under age 12 who do not yet qualify for a vaccine. Certainly, unvaccinated parents could spread the virus to their young children, and unvaccinated children could transmit the illness to immediate and extended family. Now that the CDC has said that there is a risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated people in areas with high community transmission, should we worry about unvaccinated young children with vaccinated parents? I recently spoke with James C. Fagin, MD, a board-certified pediatrician and immunologist, to get his views on this issue.

Dr. Fagin, who is retired, said he is in complete agreement with the Food and Drug Administration when it comes to approving medications for children. However, given the seriousness of the pandemic and the need to get our children back to in-person learning, he would like to see the approval process safely expedited. Large numbers of unvaccinated people increase the pool for the Delta variant and could increase the likelihood of a new variant that is more resistant to the vaccines, said Dr. Fagin, former chief of academic pediatrics at North Shore University Hospital and a former faculty member in the allergy/immunology division of Cohen Children’s Medical Center, both in New York.

Meanwhile, I agree with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations that children, teachers, and school staff and other adults in school settings should wear masks regardless of vaccination status. Kids adjust well to masks – as my grandchildren and their friends have.

The bottom line is that we need to get as many people as possible vaccinated as soon as possible, and while doing so, we must continue to wear face coverings in public spaces. As clinicians, we have a special responsibility to do all that we can to change minds – and behaviors.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist who has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

Like many colleagues, I have been working to change the minds and behaviors of acquaintances and patients who are opting to forgo a COVID vaccine. The large numbers of these unvaccinated Americans, combined with the surging Delta coronavirus variant, are endangering the health of us all.

When I spoke with the 22-year-old daughter of a family friend about what was holding her back, she told me that she would “never” get vaccinated. I shared my vaccination experience and told her that, except for a sore arm both times for a day, I felt no side effects. Likewise, I said, all of my adult family members are vaccinated, and everyone is fine. She was neither moved nor convinced.

Finally, I asked her whether she attended school (knowing that she was a college graduate), and she said “yes.” So I told her that all 50 states require children attending public schools to be vaccinated for diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, polio, and the chickenpox – with certain religious, philosophical, and medical exemptions. Her response was simple: “I didn’t know that. Anyway, my parents were in charge.” Suddenly, her thinking shifted. “You’re right,” she said. She got a COVID shot the next day. Success for me.

When I asked another acquaintance whether he’d been vaccinated, he said he’d heard people were getting very sick from the vaccine – and was going to wait. Another gentleman I spoke with said that, at age 45, he was healthy. Besides, he added, he “doesn’t get sick.” When I asked another acquaintance about her vaccination status, her retort was that this was none of my business. So far, I’m batting about .300.

But as a physician, I believe that we – and other health care providers – must continue to encourage the people in our lives to care for themselves and others by getting vaccinated. One concrete step advised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is to help people make an appointment for a shot. Some sites no longer require appointments, and New York City, for example, offers in-home vaccinations to all NYC residents.

Also, NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Aug. 3 the “Key to NYC Pass,” which he called a “first-in-the-nation approach” to vaccination. Under this new policy, vaccine-eligible people aged 12 and older in New York City will need to prove with a vaccination card, an app, or an Excelsior Pass that they have received at least one dose of vaccine before participating in indoor venues such as restaurants, bars, gyms, and movie theaters within the city. Mayor de Blasio said the new initiative, which is still being finalized, will be phased in starting the week of Aug. 16. I see this as a major public health measure that will keep people healthy – and get them vaccinated.

The medical community should support this move by the city of New York and encourage people to follow CDC guidance on wearing face coverings in public settings, especially schools. New research shows that physicians continue to be among the most trusted sources of vaccine-related information.

Another strategy we might use is to point to the longtime practices of surgeons. We could ask: Why do surgeons wear face masks in the operating room? For years, these coverings have been used to protect patients from the nasal and oral bacteria generated by operating room staff. Likewise, we can tell those who remain on the fence that, by wearing face masks, we are protecting others from all variants, but specifically from Delta – which the CDC now says can be transmitted by people who are fully vaccinated.

Why did the CDC lift face mask guidance for fully vaccinated people in indoor spaces in May? It was clear to me and other colleagues back then that this was not a good idea. Despite that guidance, I continued to wear a mask in public places and advised anyone who would listen to do the same.

The development of vaccines in the 20th and 21st centuries has saved millions of lives. The World Health Organization reports that 4 million to 5 million lives a year are saved by immunizations. In addition, research shows that, before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, vaccinations led to the eradication of smallpox and polio, and a 74% drop in measles-related deaths between 2004 and 2014.

Protecting the most vulnerable

With COVID cases surging, particularly in parts of the South and Midwest, I am concerned about children under age 12 who do not yet qualify for a vaccine. Certainly, unvaccinated parents could spread the virus to their young children, and unvaccinated children could transmit the illness to immediate and extended family. Now that the CDC has said that there is a risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated people in areas with high community transmission, should we worry about unvaccinated young children with vaccinated parents? I recently spoke with James C. Fagin, MD, a board-certified pediatrician and immunologist, to get his views on this issue.

Dr. Fagin, who is retired, said he is in complete agreement with the Food and Drug Administration when it comes to approving medications for children. However, given the seriousness of the pandemic and the need to get our children back to in-person learning, he would like to see the approval process safely expedited. Large numbers of unvaccinated people increase the pool for the Delta variant and could increase the likelihood of a new variant that is more resistant to the vaccines, said Dr. Fagin, former chief of academic pediatrics at North Shore University Hospital and a former faculty member in the allergy/immunology division of Cohen Children’s Medical Center, both in New York.

Meanwhile, I agree with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations that children, teachers, and school staff and other adults in school settings should wear masks regardless of vaccination status. Kids adjust well to masks – as my grandchildren and their friends have.

The bottom line is that we need to get as many people as possible vaccinated as soon as possible, and while doing so, we must continue to wear face coverings in public spaces. As clinicians, we have a special responsibility to do all that we can to change minds – and behaviors.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist who has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

Indoor masking needed in almost 70% of U.S. counties: CDC data

In announcing new guidance on July 27, the CDC said vaccinated people should wear face masks in indoor public places with “high” or “substantial” community transmission rates of COVID-19.

Data from the CDC shows that designation covers 69.3% of all counties in the United States – 52.2% (1,680 counties) with high community transmission rates and 17.1% (551 counties) with substantial rates.

A county has “high transmission” if it reports 100 or more weekly cases per 100,000 residents or a 10% or higher test positivity rate in the last 7 days, the CDC said. “Substantial transmission” means a county reports 50-99 weekly cases per 100,000 residents or has a positivity rate between 8% and 9.9% in the last 7 days.

About 23% of U.S. counties had moderate rates of community transmission, and 7.67% had low rates.

To find out the transmission rate in your county, go to the CDC COVID data tracker.

Smithsonian requiring masks again

The Smithsonian now requires all visitors over age 2, regardless of vaccination status, to wear face masks indoors and in all museum spaces.

The Smithsonian said in a news release that fully vaccinated visitors won’t have to wear masks at the National Zoo or outdoor gardens for museums.

The new rule goes into effect Aug. 6. It reverses a rule that said fully vaccinated visitors didn’t have to wear masks indoors beginning June 28.

Indoor face masks will be required throughout the District of Columbia beginning July 31., D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser.

House Republicans protest face mask policy

About 40 maskless Republican members of the U.S. House of Representatives filed onto the Senate floor on July 29 to protest a new rule requiring House members to wear face masks, the Hill reported.

Congress’s attending doctor said in a memo that the 435 members of the House, plus workers, must wear masks indoors, but not the 100 members of the Senate. The Senate is a smaller body and has had better mask compliance than the House.

Rep. Ronny Jackson (R-Tex.), told the Hill that Republicans wanted to show “what it was like on the floor of the Senate versus the floor of the House. Obviously, it’s vastly different.”

Among the group of Republicans who filed onto the Senate floor were Rep. Lauren Boebert of Colorado, Rep. Matt Gaetz and Rep. Byron Donalds of Florida, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, Rep. Chip Roy and Rep. Louie Gohmert of Texas, Rep. Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina, Rep. Warren Davidson of Ohio, and Rep. Andy Biggs of Arizona.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In announcing new guidance on July 27, the CDC said vaccinated people should wear face masks in indoor public places with “high” or “substantial” community transmission rates of COVID-19.

Data from the CDC shows that designation covers 69.3% of all counties in the United States – 52.2% (1,680 counties) with high community transmission rates and 17.1% (551 counties) with substantial rates.

A county has “high transmission” if it reports 100 or more weekly cases per 100,000 residents or a 10% or higher test positivity rate in the last 7 days, the CDC said. “Substantial transmission” means a county reports 50-99 weekly cases per 100,000 residents or has a positivity rate between 8% and 9.9% in the last 7 days.

About 23% of U.S. counties had moderate rates of community transmission, and 7.67% had low rates.

To find out the transmission rate in your county, go to the CDC COVID data tracker.

Smithsonian requiring masks again

The Smithsonian now requires all visitors over age 2, regardless of vaccination status, to wear face masks indoors and in all museum spaces.

The Smithsonian said in a news release that fully vaccinated visitors won’t have to wear masks at the National Zoo or outdoor gardens for museums.

The new rule goes into effect Aug. 6. It reverses a rule that said fully vaccinated visitors didn’t have to wear masks indoors beginning June 28.

Indoor face masks will be required throughout the District of Columbia beginning July 31., D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser.

House Republicans protest face mask policy

About 40 maskless Republican members of the U.S. House of Representatives filed onto the Senate floor on July 29 to protest a new rule requiring House members to wear face masks, the Hill reported.

Congress’s attending doctor said in a memo that the 435 members of the House, plus workers, must wear masks indoors, but not the 100 members of the Senate. The Senate is a smaller body and has had better mask compliance than the House.

Rep. Ronny Jackson (R-Tex.), told the Hill that Republicans wanted to show “what it was like on the floor of the Senate versus the floor of the House. Obviously, it’s vastly different.”

Among the group of Republicans who filed onto the Senate floor were Rep. Lauren Boebert of Colorado, Rep. Matt Gaetz and Rep. Byron Donalds of Florida, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, Rep. Chip Roy and Rep. Louie Gohmert of Texas, Rep. Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina, Rep. Warren Davidson of Ohio, and Rep. Andy Biggs of Arizona.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In announcing new guidance on July 27, the CDC said vaccinated people should wear face masks in indoor public places with “high” or “substantial” community transmission rates of COVID-19.

Data from the CDC shows that designation covers 69.3% of all counties in the United States – 52.2% (1,680 counties) with high community transmission rates and 17.1% (551 counties) with substantial rates.

A county has “high transmission” if it reports 100 or more weekly cases per 100,000 residents or a 10% or higher test positivity rate in the last 7 days, the CDC said. “Substantial transmission” means a county reports 50-99 weekly cases per 100,000 residents or has a positivity rate between 8% and 9.9% in the last 7 days.

About 23% of U.S. counties had moderate rates of community transmission, and 7.67% had low rates.

To find out the transmission rate in your county, go to the CDC COVID data tracker.

Smithsonian requiring masks again

The Smithsonian now requires all visitors over age 2, regardless of vaccination status, to wear face masks indoors and in all museum spaces.

The Smithsonian said in a news release that fully vaccinated visitors won’t have to wear masks at the National Zoo or outdoor gardens for museums.

The new rule goes into effect Aug. 6. It reverses a rule that said fully vaccinated visitors didn’t have to wear masks indoors beginning June 28.

Indoor face masks will be required throughout the District of Columbia beginning July 31., D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser.

House Republicans protest face mask policy

About 40 maskless Republican members of the U.S. House of Representatives filed onto the Senate floor on July 29 to protest a new rule requiring House members to wear face masks, the Hill reported.

Congress’s attending doctor said in a memo that the 435 members of the House, plus workers, must wear masks indoors, but not the 100 members of the Senate. The Senate is a smaller body and has had better mask compliance than the House.

Rep. Ronny Jackson (R-Tex.), told the Hill that Republicans wanted to show “what it was like on the floor of the Senate versus the floor of the House. Obviously, it’s vastly different.”

Among the group of Republicans who filed onto the Senate floor were Rep. Lauren Boebert of Colorado, Rep. Matt Gaetz and Rep. Byron Donalds of Florida, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, Rep. Chip Roy and Rep. Louie Gohmert of Texas, Rep. Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina, Rep. Warren Davidson of Ohio, and Rep. Andy Biggs of Arizona.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

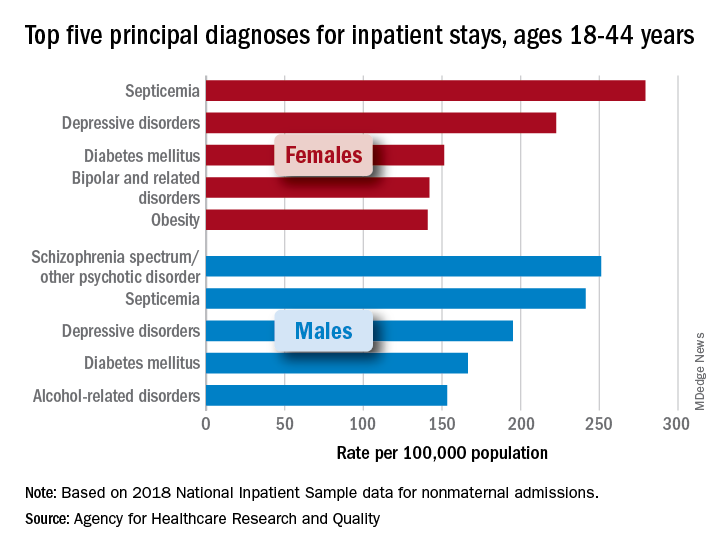

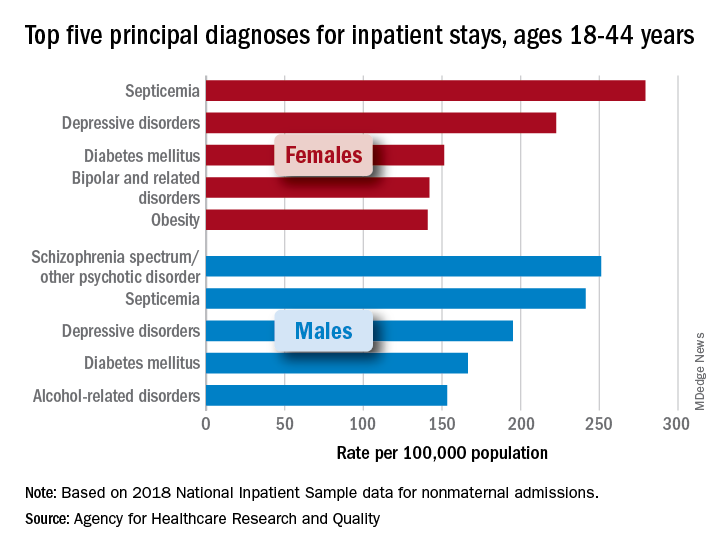

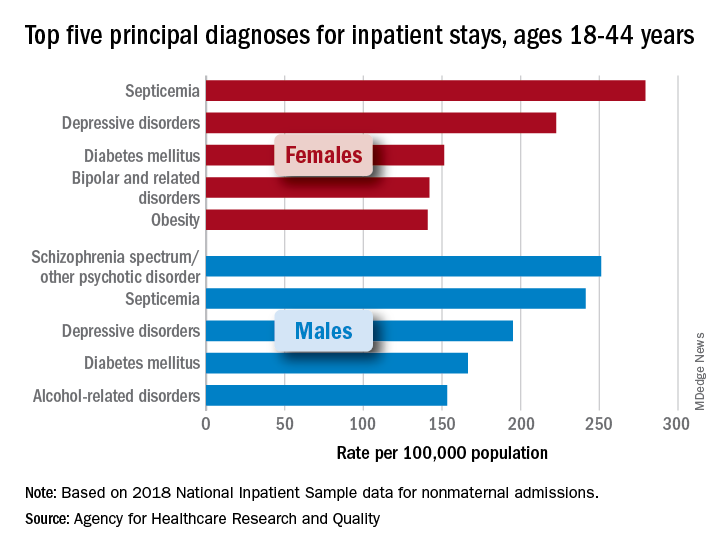

Mental illness admissions: 18-44 is the age of prevalence

More mental and/or substance use disorders are ranked among the top-five diagnoses for hospitalized men and women aged 18-44 years than for any other age group, according to a recent report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

aged 18-44, while depressive disorders were the third-most common (195.0 stays per 100,000) and alcohol-related disorders were fifth at 153.2 per 100,000, Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and Marc Roemer, MS, said in an AHRQ statistical brief.

Prevalence was somewhat lower in women aged 18-44 years, with two mental illnesses appearing among the top five nonmaternal diagnoses: Depressive disorders were second at 222.5 stays per 100,000 and bipolar and related disorders were fourth at 142.0 per 100,000. The leading primary diagnosis in women in 2018 was septicemia, which was the most common cause overall in the age group at a rate of 279.3 per 100,000, the investigators reported.

There were no mental and/or substance use disorders in the top five primary diagnoses for any of the other adult age groups – 45-64, 65-74, and ≥75 – included in the report. Septicemia was the leading diagnosis for men in all three groups and for women in two of three (45-64 and ≥75), with osteoarthritis first among women aged 65-74 years, they said.

There was one mental illness among the top-five diagnoses for children under age 18 years, as depressive disorders were the most common reason for stays in girls (176.6 per 100,000 population) and the fifth most common for boys (74.0 per 100,000), said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Mr. Roemer of AHRQ.

Septicemia was the leading nonmaternal, nonneonatal diagnosis for all inpatient stays and all ages in 2018 with a rate of 679.5 per 100,000, followed by heart failure (347.9), osteoarthritis (345.5), pneumonia not related to tuberculosis (226.8), and diabetes mellitus (207.8), based on data from the National Inpatient Sample.

Depressive disorders were most common mental health diagnosis in those admitted to hospitals and the 12th most common diagnosis overall; schizophrenia, in 16th place overall, was the only other mental illness among the top 20, the investigators said.

“This information can help establish national health priorities, initiatives, and action plans,” Dr. McDermott and Mr. Roemer wrote, and “at the hospital level, administrators can use diagnosis-related information to inform planning and resource allocation, such as optimizing subspecialty services or units for the care of high-priority conditions.”

More mental and/or substance use disorders are ranked among the top-five diagnoses for hospitalized men and women aged 18-44 years than for any other age group, according to a recent report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

aged 18-44, while depressive disorders were the third-most common (195.0 stays per 100,000) and alcohol-related disorders were fifth at 153.2 per 100,000, Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and Marc Roemer, MS, said in an AHRQ statistical brief.

Prevalence was somewhat lower in women aged 18-44 years, with two mental illnesses appearing among the top five nonmaternal diagnoses: Depressive disorders were second at 222.5 stays per 100,000 and bipolar and related disorders were fourth at 142.0 per 100,000. The leading primary diagnosis in women in 2018 was septicemia, which was the most common cause overall in the age group at a rate of 279.3 per 100,000, the investigators reported.

There were no mental and/or substance use disorders in the top five primary diagnoses for any of the other adult age groups – 45-64, 65-74, and ≥75 – included in the report. Septicemia was the leading diagnosis for men in all three groups and for women in two of three (45-64 and ≥75), with osteoarthritis first among women aged 65-74 years, they said.

There was one mental illness among the top-five diagnoses for children under age 18 years, as depressive disorders were the most common reason for stays in girls (176.6 per 100,000 population) and the fifth most common for boys (74.0 per 100,000), said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Mr. Roemer of AHRQ.

Septicemia was the leading nonmaternal, nonneonatal diagnosis for all inpatient stays and all ages in 2018 with a rate of 679.5 per 100,000, followed by heart failure (347.9), osteoarthritis (345.5), pneumonia not related to tuberculosis (226.8), and diabetes mellitus (207.8), based on data from the National Inpatient Sample.

Depressive disorders were most common mental health diagnosis in those admitted to hospitals and the 12th most common diagnosis overall; schizophrenia, in 16th place overall, was the only other mental illness among the top 20, the investigators said.

“This information can help establish national health priorities, initiatives, and action plans,” Dr. McDermott and Mr. Roemer wrote, and “at the hospital level, administrators can use diagnosis-related information to inform planning and resource allocation, such as optimizing subspecialty services or units for the care of high-priority conditions.”

More mental and/or substance use disorders are ranked among the top-five diagnoses for hospitalized men and women aged 18-44 years than for any other age group, according to a recent report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

aged 18-44, while depressive disorders were the third-most common (195.0 stays per 100,000) and alcohol-related disorders were fifth at 153.2 per 100,000, Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and Marc Roemer, MS, said in an AHRQ statistical brief.

Prevalence was somewhat lower in women aged 18-44 years, with two mental illnesses appearing among the top five nonmaternal diagnoses: Depressive disorders were second at 222.5 stays per 100,000 and bipolar and related disorders were fourth at 142.0 per 100,000. The leading primary diagnosis in women in 2018 was septicemia, which was the most common cause overall in the age group at a rate of 279.3 per 100,000, the investigators reported.

There were no mental and/or substance use disorders in the top five primary diagnoses for any of the other adult age groups – 45-64, 65-74, and ≥75 – included in the report. Septicemia was the leading diagnosis for men in all three groups and for women in two of three (45-64 and ≥75), with osteoarthritis first among women aged 65-74 years, they said.

There was one mental illness among the top-five diagnoses for children under age 18 years, as depressive disorders were the most common reason for stays in girls (176.6 per 100,000 population) and the fifth most common for boys (74.0 per 100,000), said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Mr. Roemer of AHRQ.

Septicemia was the leading nonmaternal, nonneonatal diagnosis for all inpatient stays and all ages in 2018 with a rate of 679.5 per 100,000, followed by heart failure (347.9), osteoarthritis (345.5), pneumonia not related to tuberculosis (226.8), and diabetes mellitus (207.8), based on data from the National Inpatient Sample.

Depressive disorders were most common mental health diagnosis in those admitted to hospitals and the 12th most common diagnosis overall; schizophrenia, in 16th place overall, was the only other mental illness among the top 20, the investigators said.

“This information can help establish national health priorities, initiatives, and action plans,” Dr. McDermott and Mr. Roemer wrote, and “at the hospital level, administrators can use diagnosis-related information to inform planning and resource allocation, such as optimizing subspecialty services or units for the care of high-priority conditions.”

Short sleep is linked to future dementia

, according to a new analysis of data from the Whitehall II cohort study.

Previous work had identified links between short sleep duration and dementia risk, but few studies examined sleep habits long before onset of dementia. Those that did produced inconsistent results, according to Séverine Sabia, PhD, who is a research associate at Inserm (France) and the University College London.

“One potential reason for these inconstancies is the large range of ages of the study populations, and the small number of participants within each sleep duration group. The novelty of our study is to examine this association among almost 8,000 participants with a follow-up of 30 years, using repeated measures of sleep duration starting in midlife to consider sleep duration at specific ages,” Dr. Sabia said in an interview. She presented the research at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Those previous studies found a U-shaped association between sleep duration and dementia risk, with lowest risk associated with 7-8 hours of sleep, but greater risk for shorter and longer durations. However, because the studies had follow-up periods shorter than 10 years, they are at greater risk of reverse causation bias. Longer follow-up studies tended to have small sample sizes or to focus on older adults.

The longer follow-up in the current study makes for a more compelling case, said Claire Sexton, DPhil, director of Scientific Programs & Outreach for the Alzheimer’s Association. Observations of short or long sleep closer to the onset of symptoms could just be a warning sign of dementia. “But looking at age 50, age 60 ... if you’re seeing those relationships, then it’s less likely that it is just purely prodromal,” said Dr. Sexton. But it still doesn’t necessarily confirm causation. “It could also be a risk factor,” Dr. Sexton added.

Multifactorial risk

Dr. Sabia also noted that the magnitude of risk was similar to that seen with smoking or obesity, and many factors play a role in dementia risk. “Even if the risk of dementia was 30% higher in those with persistent short sleep duration, in absolute terms, the percentage of those with persistent short duration who developed dementia was 8%, and 6% in those with persistent sleep duration of 7 hours. Dementia is a multifactorial disease, which means that several factors are likely to influence its onset. Sleep duration is one of them, but if a person has poor sleep and does not manage to increase it, there are other important prevention measures. It is important to keep a healthy lifestyle and cardiometabolic measures in the normal range. All together it is likely to be beneficial for brain health in later life,” she said.

Dr. Sexton agreed. “With sleep we’re still trying to tease apart what aspect of sleep is important. Is it the sleep duration? Is it the quality of sleep? Is it certain sleep stages?” she said.

Regardless of sleep’s potential influence on dementia risk, both Dr. Sexton and Dr. Sabia noted the importance of sleep for general health. “These types of problems are very prevalent, so it’s good for people to be aware of them. And then if they notice any problems with their sleep, or any changes, to go and see their health care provider, and to be discussing them, and then to be investigating the cause, and to see whether changes in sleep hygiene and treatments for insomnia could address these sleep problems,” said Dr. Sexton.

Decades of data

During the Whitehall II study, researchers assessed average sleep duration (“How many hours of sleep do you have on an average weeknight?”) six times over 30 years of follow-up. Dr. Sabia’s group extracted self-reported sleep duration data at ages 50, 60, and 70. Short sleep duration was defined as fewer than 5 hours, or 6 hours. Normal sleep duration was defined as 7 hours. Long duration was defined as 8 hours or more.

A questioner during the Q&A period noted that this grouping is a little unusual. Many studies define 7-8 hours as normal. Dr. Sabia answered that they were unable to examine periods of 9 hours or more due to the nature of the data, and the lowest associated risk was found at 7 hours.

The researchers analyzed data from 7,959 participants (33.0% women). At age 50, compared with 7 hours of sleep, 6 or few hours of sleep was associated with a higher risk of dementia over the ensuing 25 years of follow-up (hazard ratio [HR], 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01-1.48). The same was true at age 60 (15 years of follow-up HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.10-1.72). There was a trend at age 70 (8 years follow-up; HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.98-1.57). For 8 or more hours of sleep, there were trends toward increased risk at age 50 (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.98-1.60). Long sleep at age 60 and 70 was associated with heightened risk, but the confidence intervals were well outside statistical significance.

Twenty percent of participants had persistent short sleep over the course of follow-up, 37% had persistent normal sleep, and 7% had persistent long sleep. Seven percent of participants experienced a change from normal sleep to short sleep, 16% had a change from short sleep to normal sleep, and 13% had a change from normal sleep to long sleep.

Persistent short sleep between age 50 and 70 was associated with a 30% increased risk of dementia (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.00-1.69). There were no statistically significant associations between dementia risk and any of the changing sleep pattern groups.

Dr. Sabia and Dr. Sexton have no relevant financial disclosures.

, according to a new analysis of data from the Whitehall II cohort study.

Previous work had identified links between short sleep duration and dementia risk, but few studies examined sleep habits long before onset of dementia. Those that did produced inconsistent results, according to Séverine Sabia, PhD, who is a research associate at Inserm (France) and the University College London.

“One potential reason for these inconstancies is the large range of ages of the study populations, and the small number of participants within each sleep duration group. The novelty of our study is to examine this association among almost 8,000 participants with a follow-up of 30 years, using repeated measures of sleep duration starting in midlife to consider sleep duration at specific ages,” Dr. Sabia said in an interview. She presented the research at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Those previous studies found a U-shaped association between sleep duration and dementia risk, with lowest risk associated with 7-8 hours of sleep, but greater risk for shorter and longer durations. However, because the studies had follow-up periods shorter than 10 years, they are at greater risk of reverse causation bias. Longer follow-up studies tended to have small sample sizes or to focus on older adults.

The longer follow-up in the current study makes for a more compelling case, said Claire Sexton, DPhil, director of Scientific Programs & Outreach for the Alzheimer’s Association. Observations of short or long sleep closer to the onset of symptoms could just be a warning sign of dementia. “But looking at age 50, age 60 ... if you’re seeing those relationships, then it’s less likely that it is just purely prodromal,” said Dr. Sexton. But it still doesn’t necessarily confirm causation. “It could also be a risk factor,” Dr. Sexton added.

Multifactorial risk

Dr. Sabia also noted that the magnitude of risk was similar to that seen with smoking or obesity, and many factors play a role in dementia risk. “Even if the risk of dementia was 30% higher in those with persistent short sleep duration, in absolute terms, the percentage of those with persistent short duration who developed dementia was 8%, and 6% in those with persistent sleep duration of 7 hours. Dementia is a multifactorial disease, which means that several factors are likely to influence its onset. Sleep duration is one of them, but if a person has poor sleep and does not manage to increase it, there are other important prevention measures. It is important to keep a healthy lifestyle and cardiometabolic measures in the normal range. All together it is likely to be beneficial for brain health in later life,” she said.

Dr. Sexton agreed. “With sleep we’re still trying to tease apart what aspect of sleep is important. Is it the sleep duration? Is it the quality of sleep? Is it certain sleep stages?” she said.

Regardless of sleep’s potential influence on dementia risk, both Dr. Sexton and Dr. Sabia noted the importance of sleep for general health. “These types of problems are very prevalent, so it’s good for people to be aware of them. And then if they notice any problems with their sleep, or any changes, to go and see their health care provider, and to be discussing them, and then to be investigating the cause, and to see whether changes in sleep hygiene and treatments for insomnia could address these sleep problems,” said Dr. Sexton.

Decades of data

During the Whitehall II study, researchers assessed average sleep duration (“How many hours of sleep do you have on an average weeknight?”) six times over 30 years of follow-up. Dr. Sabia’s group extracted self-reported sleep duration data at ages 50, 60, and 70. Short sleep duration was defined as fewer than 5 hours, or 6 hours. Normal sleep duration was defined as 7 hours. Long duration was defined as 8 hours or more.

A questioner during the Q&A period noted that this grouping is a little unusual. Many studies define 7-8 hours as normal. Dr. Sabia answered that they were unable to examine periods of 9 hours or more due to the nature of the data, and the lowest associated risk was found at 7 hours.

The researchers analyzed data from 7,959 participants (33.0% women). At age 50, compared with 7 hours of sleep, 6 or few hours of sleep was associated with a higher risk of dementia over the ensuing 25 years of follow-up (hazard ratio [HR], 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01-1.48). The same was true at age 60 (15 years of follow-up HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.10-1.72). There was a trend at age 70 (8 years follow-up; HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.98-1.57). For 8 or more hours of sleep, there were trends toward increased risk at age 50 (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.98-1.60). Long sleep at age 60 and 70 was associated with heightened risk, but the confidence intervals were well outside statistical significance.

Twenty percent of participants had persistent short sleep over the course of follow-up, 37% had persistent normal sleep, and 7% had persistent long sleep. Seven percent of participants experienced a change from normal sleep to short sleep, 16% had a change from short sleep to normal sleep, and 13% had a change from normal sleep to long sleep.

Persistent short sleep between age 50 and 70 was associated with a 30% increased risk of dementia (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.00-1.69). There were no statistically significant associations between dementia risk and any of the changing sleep pattern groups.

Dr. Sabia and Dr. Sexton have no relevant financial disclosures.

, according to a new analysis of data from the Whitehall II cohort study.

Previous work had identified links between short sleep duration and dementia risk, but few studies examined sleep habits long before onset of dementia. Those that did produced inconsistent results, according to Séverine Sabia, PhD, who is a research associate at Inserm (France) and the University College London.

“One potential reason for these inconstancies is the large range of ages of the study populations, and the small number of participants within each sleep duration group. The novelty of our study is to examine this association among almost 8,000 participants with a follow-up of 30 years, using repeated measures of sleep duration starting in midlife to consider sleep duration at specific ages,” Dr. Sabia said in an interview. She presented the research at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Those previous studies found a U-shaped association between sleep duration and dementia risk, with lowest risk associated with 7-8 hours of sleep, but greater risk for shorter and longer durations. However, because the studies had follow-up periods shorter than 10 years, they are at greater risk of reverse causation bias. Longer follow-up studies tended to have small sample sizes or to focus on older adults.

The longer follow-up in the current study makes for a more compelling case, said Claire Sexton, DPhil, director of Scientific Programs & Outreach for the Alzheimer’s Association. Observations of short or long sleep closer to the onset of symptoms could just be a warning sign of dementia. “But looking at age 50, age 60 ... if you’re seeing those relationships, then it’s less likely that it is just purely prodromal,” said Dr. Sexton. But it still doesn’t necessarily confirm causation. “It could also be a risk factor,” Dr. Sexton added.

Multifactorial risk

Dr. Sabia also noted that the magnitude of risk was similar to that seen with smoking or obesity, and many factors play a role in dementia risk. “Even if the risk of dementia was 30% higher in those with persistent short sleep duration, in absolute terms, the percentage of those with persistent short duration who developed dementia was 8%, and 6% in those with persistent sleep duration of 7 hours. Dementia is a multifactorial disease, which means that several factors are likely to influence its onset. Sleep duration is one of them, but if a person has poor sleep and does not manage to increase it, there are other important prevention measures. It is important to keep a healthy lifestyle and cardiometabolic measures in the normal range. All together it is likely to be beneficial for brain health in later life,” she said.

Dr. Sexton agreed. “With sleep we’re still trying to tease apart what aspect of sleep is important. Is it the sleep duration? Is it the quality of sleep? Is it certain sleep stages?” she said.

Regardless of sleep’s potential influence on dementia risk, both Dr. Sexton and Dr. Sabia noted the importance of sleep for general health. “These types of problems are very prevalent, so it’s good for people to be aware of them. And then if they notice any problems with their sleep, or any changes, to go and see their health care provider, and to be discussing them, and then to be investigating the cause, and to see whether changes in sleep hygiene and treatments for insomnia could address these sleep problems,” said Dr. Sexton.

Decades of data

During the Whitehall II study, researchers assessed average sleep duration (“How many hours of sleep do you have on an average weeknight?”) six times over 30 years of follow-up. Dr. Sabia’s group extracted self-reported sleep duration data at ages 50, 60, and 70. Short sleep duration was defined as fewer than 5 hours, or 6 hours. Normal sleep duration was defined as 7 hours. Long duration was defined as 8 hours or more.

A questioner during the Q&A period noted that this grouping is a little unusual. Many studies define 7-8 hours as normal. Dr. Sabia answered that they were unable to examine periods of 9 hours or more due to the nature of the data, and the lowest associated risk was found at 7 hours.

The researchers analyzed data from 7,959 participants (33.0% women). At age 50, compared with 7 hours of sleep, 6 or few hours of sleep was associated with a higher risk of dementia over the ensuing 25 years of follow-up (hazard ratio [HR], 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01-1.48). The same was true at age 60 (15 years of follow-up HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.10-1.72). There was a trend at age 70 (8 years follow-up; HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.98-1.57). For 8 or more hours of sleep, there were trends toward increased risk at age 50 (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.98-1.60). Long sleep at age 60 and 70 was associated with heightened risk, but the confidence intervals were well outside statistical significance.

Twenty percent of participants had persistent short sleep over the course of follow-up, 37% had persistent normal sleep, and 7% had persistent long sleep. Seven percent of participants experienced a change from normal sleep to short sleep, 16% had a change from short sleep to normal sleep, and 13% had a change from normal sleep to long sleep.

Persistent short sleep between age 50 and 70 was associated with a 30% increased risk of dementia (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.00-1.69). There were no statistically significant associations between dementia risk and any of the changing sleep pattern groups.

Dr. Sabia and Dr. Sexton have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AAIC 2021

Bronchitis the leader at putting children in the hospital

About 7% (99,000) of the 1.47 million nonmaternal, nonneonatal hospital stays in children aged 0-17 years involved a primary diagnosis of acute bronchitis in 2018, representing the leading cause of admissions in boys (154.7 stays per 100,000 population) and the second-leading diagnosis in girls (113.1 stays per 100,000), Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and Marc Roemer, MS, said in a statistical brief.

Depressive disorders were the most common primary diagnosis in girls, with a rate of 176.7 stays per 100,000, and the second-leading diagnosis overall, although the rate was less than half that (74.0 per 100,000) in boys. Two other respiratory conditions, asthma and pneumonia, were among the top five for both girls and boys, as was epilepsy, they reported.

The combined rate for all diagnoses was slightly higher for boys, 2,051 per 100,000, compared with 1,922 for girls, they said based on data from the National Inpatient Sample.

“Identifying the most frequent primary conditions for which patients are admitted to the hospital is important to the implementation and improvement of health care delivery, quality initiatives, and health policy,” said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Mr. Roemer of the AHRQ.

About 7% (99,000) of the 1.47 million nonmaternal, nonneonatal hospital stays in children aged 0-17 years involved a primary diagnosis of acute bronchitis in 2018, representing the leading cause of admissions in boys (154.7 stays per 100,000 population) and the second-leading diagnosis in girls (113.1 stays per 100,000), Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and Marc Roemer, MS, said in a statistical brief.

Depressive disorders were the most common primary diagnosis in girls, with a rate of 176.7 stays per 100,000, and the second-leading diagnosis overall, although the rate was less than half that (74.0 per 100,000) in boys. Two other respiratory conditions, asthma and pneumonia, were among the top five for both girls and boys, as was epilepsy, they reported.

The combined rate for all diagnoses was slightly higher for boys, 2,051 per 100,000, compared with 1,922 for girls, they said based on data from the National Inpatient Sample.

“Identifying the most frequent primary conditions for which patients are admitted to the hospital is important to the implementation and improvement of health care delivery, quality initiatives, and health policy,” said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Mr. Roemer of the AHRQ.

About 7% (99,000) of the 1.47 million nonmaternal, nonneonatal hospital stays in children aged 0-17 years involved a primary diagnosis of acute bronchitis in 2018, representing the leading cause of admissions in boys (154.7 stays per 100,000 population) and the second-leading diagnosis in girls (113.1 stays per 100,000), Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and Marc Roemer, MS, said in a statistical brief.

Depressive disorders were the most common primary diagnosis in girls, with a rate of 176.7 stays per 100,000, and the second-leading diagnosis overall, although the rate was less than half that (74.0 per 100,000) in boys. Two other respiratory conditions, asthma and pneumonia, were among the top five for both girls and boys, as was epilepsy, they reported.

The combined rate for all diagnoses was slightly higher for boys, 2,051 per 100,000, compared with 1,922 for girls, they said based on data from the National Inpatient Sample.

“Identifying the most frequent primary conditions for which patients are admitted to the hospital is important to the implementation and improvement of health care delivery, quality initiatives, and health policy,” said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Mr. Roemer of the AHRQ.

COVID-19, hearings on Jan. 6 attack reignite interest in PTSD

After Sept. 11, 2001, and the subsequent long war in Iraq and Afghanistan, both mental health providers and the general public focused on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, after almost 20 years of war and the COVID-19 epidemic, attention waned away from military service members and PTSD.

COVID-19–related PTSD and the hearings on the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol have reignited interest in PTSD diagnosis and treatment. Testimony from police officers at the House select committee hearing about their experiences during the assault and PTSD was harrowing. One of the police officers had also served in Iraq, perhaps leading to “layered PTSD” – symptoms from war abroad and at home.

Thus, I thought a brief review of updates about diagnosis and treatment would be useful. Note: These are my opinions based on my extensive experience and do not represent the official opinion of my employer (MedStar Health).

PTSD was first classified as a disorder in 1980, based mainly on the experiences of military service members in Vietnam, as well as sexual assault victims and disaster survivors. Readers may look elsewhere for a fuller history of the disorder.

However, in brief, we have evolved from strict reliance on a variety of symptoms in the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) to a more global determination of the experience of trauma and related symptoms of distress. We still rely for diagnosis on trauma-related anxiety and depression symptoms, such as nightmare, flashbacks, numbness, and disassociation.

Treatment has evolved. Patients may benefit from treatment even if they do not meet all the PTSD criteria. As many of my colleagues who treat patients have said, “if it smells like PTSD, treat it like PTSD.”

What is the most effective treatment? The literature declares that evidence-based treatments include two selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Zoloft and Paxil) and several psychotherapies. The psychotherapies include cognitive-behavioral therapies, exposure therapy, and EMDR (eye movement desensitization reprocessing).

The problem is that many patients cannot tolerate these therapies. SSRIs do have side effects, the most distressing being sexual dysfunction. Many service members do not enter the psychotherapies, or they drop out of trials, because they cannot tolerate the reimagining of their trauma.

I now counsel patients about the “three buckets” of treatment. The first bucket is medication, which as a psychiatrist is what I focus on. The second bucket is psychotherapy as discussed above. The third bucket is “everything else.”

“Everything else” includes a variety of methods the patients can use to reduce symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms: exercising; deep breathing through the nose; doing yoga; doing meditation; playing or working with animals; gardening; and engaging in other activities that “self sooth.” I also recommend always doing “small acts of kindness” for others. I myself contribute to food banks and bring cookies or watermelons to the staff at my hospital.

Why is this approach useful? A menu of options gives control back to the patient. It provides activities that can reduce anxiety. Thinking about caring for others helps patients get out of their own “swamp of distress.”

We do live in very difficult times. We’re coping with COVID-19 Delta variant, attacks on the Capitol, and gun violence. I have not yet mentioned climate change, which is extremely frightening to many of us. So all providers need to be aware of all the strategies at our disposal to treat anxiety, depression, and PTSD.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center. She has no conflicts of interest.

After Sept. 11, 2001, and the subsequent long war in Iraq and Afghanistan, both mental health providers and the general public focused on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, after almost 20 years of war and the COVID-19 epidemic, attention waned away from military service members and PTSD.

COVID-19–related PTSD and the hearings on the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol have reignited interest in PTSD diagnosis and treatment. Testimony from police officers at the House select committee hearing about their experiences during the assault and PTSD was harrowing. One of the police officers had also served in Iraq, perhaps leading to “layered PTSD” – symptoms from war abroad and at home.

Thus, I thought a brief review of updates about diagnosis and treatment would be useful. Note: These are my opinions based on my extensive experience and do not represent the official opinion of my employer (MedStar Health).

PTSD was first classified as a disorder in 1980, based mainly on the experiences of military service members in Vietnam, as well as sexual assault victims and disaster survivors. Readers may look elsewhere for a fuller history of the disorder.

However, in brief, we have evolved from strict reliance on a variety of symptoms in the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) to a more global determination of the experience of trauma and related symptoms of distress. We still rely for diagnosis on trauma-related anxiety and depression symptoms, such as nightmare, flashbacks, numbness, and disassociation.

Treatment has evolved. Patients may benefit from treatment even if they do not meet all the PTSD criteria. As many of my colleagues who treat patients have said, “if it smells like PTSD, treat it like PTSD.”

What is the most effective treatment? The literature declares that evidence-based treatments include two selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Zoloft and Paxil) and several psychotherapies. The psychotherapies include cognitive-behavioral therapies, exposure therapy, and EMDR (eye movement desensitization reprocessing).

The problem is that many patients cannot tolerate these therapies. SSRIs do have side effects, the most distressing being sexual dysfunction. Many service members do not enter the psychotherapies, or they drop out of trials, because they cannot tolerate the reimagining of their trauma.

I now counsel patients about the “three buckets” of treatment. The first bucket is medication, which as a psychiatrist is what I focus on. The second bucket is psychotherapy as discussed above. The third bucket is “everything else.”

“Everything else” includes a variety of methods the patients can use to reduce symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms: exercising; deep breathing through the nose; doing yoga; doing meditation; playing or working with animals; gardening; and engaging in other activities that “self sooth.” I also recommend always doing “small acts of kindness” for others. I myself contribute to food banks and bring cookies or watermelons to the staff at my hospital.

Why is this approach useful? A menu of options gives control back to the patient. It provides activities that can reduce anxiety. Thinking about caring for others helps patients get out of their own “swamp of distress.”

We do live in very difficult times. We’re coping with COVID-19 Delta variant, attacks on the Capitol, and gun violence. I have not yet mentioned climate change, which is extremely frightening to many of us. So all providers need to be aware of all the strategies at our disposal to treat anxiety, depression, and PTSD.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center. She has no conflicts of interest.

After Sept. 11, 2001, and the subsequent long war in Iraq and Afghanistan, both mental health providers and the general public focused on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, after almost 20 years of war and the COVID-19 epidemic, attention waned away from military service members and PTSD.

COVID-19–related PTSD and the hearings on the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol have reignited interest in PTSD diagnosis and treatment. Testimony from police officers at the House select committee hearing about their experiences during the assault and PTSD was harrowing. One of the police officers had also served in Iraq, perhaps leading to “layered PTSD” – symptoms from war abroad and at home.