User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Are patient portals living up to the hype? Ask your mother-in-law!

While preparing to write this technology column, I received a great deal of insight from the unlikeliest of sources: my mother-in-law.

Now don’t get me wrong – she’s a truly lovely, intelligent, and capable woman. I have sought her advice often on many things and have always been impressed by her wisdom and pragmatism, but I’ve just never thought of asking her for her opinion on medicine or technology, as I considered her knowledge of both subjects to be limited.

This occasion changed my opinion. In fact, I believe that, as health care IT becomes more complex, people like my mother-in-law may be exactly who we should be looking to for answers.

A few weeks ago, my mother-in-law and I were discussing her recent trip to the doctor. When she mentioned some lab tests, I suggested that we log in to her patient portal to view the results. This elicited several questions and a declaration of frustration.

“Which portal?” she asked. “I have so many and can’t keep all of the websites and passwords straight! Why can’t all of my doctors use the same portal, and why do they all have different password requirements?”

As she spoke these words, I was immediately struck with an unfortunate reality of EHRs: We have done a brilliant job creating state-of-the-art digital castles and have filled them with the data needed to revolutionize care and improve population health – but we haven’t given our patients the keys to get inside.

We must ask ourselves if, in trying to construct fortresses of information around our patients, we have lost sight of the individuals in the center. I believe that we can answer this question and improve the benefits of patient portals, but we all must agree to a few simple steps to streamline the experience for everyone.

Make it easy

A study recently published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine surveyed several hospitals on their usage of patient portals. After determining whether or not the institutions had such portals, the authors then investigated to find out what, if any, guidance was provided to patients about how to use them.

Their findings are frustrating, though not surprising. While 89% of hospitals had some form of patient portal, only 65% of those “had links that were easily found, defined as links accessible within two clicks from the home page.”

Furthermore, even in cases where portals were easily found, good instructions on how to use them were missing. Those instructions that did exist centered on rules and restrictions and laying out “terms and conditions” and informing patients on “what not to do,” rather than explaining how to make the most of the experience.

According to the authors, “this focus on curtailing behavior, and the hurdles placed on finding and understanding guidance, suggest that some hospitals may be prioritizing reducing liability over improving the patient experience with portals.”

If we want our patients to use them, portals must be easy to access and intuitive to use. They also must provide value.

Make it meaningful

Patient portals have proliferated exponentially over the last 10 years, thanks to government incentive programs. One such program, known as “meaningful use,” is primarily responsible for this, as it made implementation of a patient portal one of its core requirements.

Sadly, in spite of its oft-reviled name, the meaningful use program never defined patient-friendly standards of usability for patient portals. As a result, current portals just aren’t very good. Patients like my mother-in-law find them to be too numerous, too unfriendly to use, and too limited, so they are not being used to their full potential.

In fact, many institutions may choose not to enable all of the available features in order to limit technical issues and reduce the burden on providers. In the study referenced above, only 63% of portals offered the ability for patients to communicate directly with their physicians, and only 43% offered the ability to refill prescriptions.

When enabled, these functions improve patient engagement and efficiency. Without them, patients are less likely to log on, and physicians are forced to rely on less-efficient telephone calls or traditional letters to communicate results to their patients.

Put the patient, not the portal, at the center

History has all but forgotten the attempts by tech giants such as Google and Microsoft to create personal health records. While these initially seemed like a wonderful concept, they sadly proved to be a total flop. Some patients embraced the idea, but security concerns and the lack of buy-in from EHR vendors significantly limited their uptake.

They may simply have been ahead of their time.

A decade later, wearable technology and telemedicine are ushering in a new era of patient-centric care. Individuals have been embracing a greater share of the responsibility for their own personal health information, yet most EHRs lack the ability to easily incorporate data acquired outside physicians’ offices.

It’s time for EHR vendors to go all in and change that. Instead of enslaving patients to the tyranny of fragmented health records, they should prioritize the creation of a robust, standardized, and portable health record that travels with the patient, not the other way around.

Have any other ideas on how to improve patient engagement? We’d love to hear about them and share them in a future column.

If you want to contribute but don’t have any ideas, we have a suggestion: Ask your mother-in-law. You may be surprised at what you learn!

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Follow him on twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health.

Reference

Lee JL et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Nov 12. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05528-z.

While preparing to write this technology column, I received a great deal of insight from the unlikeliest of sources: my mother-in-law.

Now don’t get me wrong – she’s a truly lovely, intelligent, and capable woman. I have sought her advice often on many things and have always been impressed by her wisdom and pragmatism, but I’ve just never thought of asking her for her opinion on medicine or technology, as I considered her knowledge of both subjects to be limited.

This occasion changed my opinion. In fact, I believe that, as health care IT becomes more complex, people like my mother-in-law may be exactly who we should be looking to for answers.

A few weeks ago, my mother-in-law and I were discussing her recent trip to the doctor. When she mentioned some lab tests, I suggested that we log in to her patient portal to view the results. This elicited several questions and a declaration of frustration.

“Which portal?” she asked. “I have so many and can’t keep all of the websites and passwords straight! Why can’t all of my doctors use the same portal, and why do they all have different password requirements?”

As she spoke these words, I was immediately struck with an unfortunate reality of EHRs: We have done a brilliant job creating state-of-the-art digital castles and have filled them with the data needed to revolutionize care and improve population health – but we haven’t given our patients the keys to get inside.

We must ask ourselves if, in trying to construct fortresses of information around our patients, we have lost sight of the individuals in the center. I believe that we can answer this question and improve the benefits of patient portals, but we all must agree to a few simple steps to streamline the experience for everyone.

Make it easy

A study recently published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine surveyed several hospitals on their usage of patient portals. After determining whether or not the institutions had such portals, the authors then investigated to find out what, if any, guidance was provided to patients about how to use them.

Their findings are frustrating, though not surprising. While 89% of hospitals had some form of patient portal, only 65% of those “had links that were easily found, defined as links accessible within two clicks from the home page.”

Furthermore, even in cases where portals were easily found, good instructions on how to use them were missing. Those instructions that did exist centered on rules and restrictions and laying out “terms and conditions” and informing patients on “what not to do,” rather than explaining how to make the most of the experience.

According to the authors, “this focus on curtailing behavior, and the hurdles placed on finding and understanding guidance, suggest that some hospitals may be prioritizing reducing liability over improving the patient experience with portals.”

If we want our patients to use them, portals must be easy to access and intuitive to use. They also must provide value.

Make it meaningful

Patient portals have proliferated exponentially over the last 10 years, thanks to government incentive programs. One such program, known as “meaningful use,” is primarily responsible for this, as it made implementation of a patient portal one of its core requirements.

Sadly, in spite of its oft-reviled name, the meaningful use program never defined patient-friendly standards of usability for patient portals. As a result, current portals just aren’t very good. Patients like my mother-in-law find them to be too numerous, too unfriendly to use, and too limited, so they are not being used to their full potential.

In fact, many institutions may choose not to enable all of the available features in order to limit technical issues and reduce the burden on providers. In the study referenced above, only 63% of portals offered the ability for patients to communicate directly with their physicians, and only 43% offered the ability to refill prescriptions.

When enabled, these functions improve patient engagement and efficiency. Without them, patients are less likely to log on, and physicians are forced to rely on less-efficient telephone calls or traditional letters to communicate results to their patients.

Put the patient, not the portal, at the center

History has all but forgotten the attempts by tech giants such as Google and Microsoft to create personal health records. While these initially seemed like a wonderful concept, they sadly proved to be a total flop. Some patients embraced the idea, but security concerns and the lack of buy-in from EHR vendors significantly limited their uptake.

They may simply have been ahead of their time.

A decade later, wearable technology and telemedicine are ushering in a new era of patient-centric care. Individuals have been embracing a greater share of the responsibility for their own personal health information, yet most EHRs lack the ability to easily incorporate data acquired outside physicians’ offices.

It’s time for EHR vendors to go all in and change that. Instead of enslaving patients to the tyranny of fragmented health records, they should prioritize the creation of a robust, standardized, and portable health record that travels with the patient, not the other way around.

Have any other ideas on how to improve patient engagement? We’d love to hear about them and share them in a future column.

If you want to contribute but don’t have any ideas, we have a suggestion: Ask your mother-in-law. You may be surprised at what you learn!

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Follow him on twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health.

Reference

Lee JL et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Nov 12. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05528-z.

While preparing to write this technology column, I received a great deal of insight from the unlikeliest of sources: my mother-in-law.

Now don’t get me wrong – she’s a truly lovely, intelligent, and capable woman. I have sought her advice often on many things and have always been impressed by her wisdom and pragmatism, but I’ve just never thought of asking her for her opinion on medicine or technology, as I considered her knowledge of both subjects to be limited.

This occasion changed my opinion. In fact, I believe that, as health care IT becomes more complex, people like my mother-in-law may be exactly who we should be looking to for answers.

A few weeks ago, my mother-in-law and I were discussing her recent trip to the doctor. When she mentioned some lab tests, I suggested that we log in to her patient portal to view the results. This elicited several questions and a declaration of frustration.

“Which portal?” she asked. “I have so many and can’t keep all of the websites and passwords straight! Why can’t all of my doctors use the same portal, and why do they all have different password requirements?”

As she spoke these words, I was immediately struck with an unfortunate reality of EHRs: We have done a brilliant job creating state-of-the-art digital castles and have filled them with the data needed to revolutionize care and improve population health – but we haven’t given our patients the keys to get inside.

We must ask ourselves if, in trying to construct fortresses of information around our patients, we have lost sight of the individuals in the center. I believe that we can answer this question and improve the benefits of patient portals, but we all must agree to a few simple steps to streamline the experience for everyone.

Make it easy

A study recently published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine surveyed several hospitals on their usage of patient portals. After determining whether or not the institutions had such portals, the authors then investigated to find out what, if any, guidance was provided to patients about how to use them.

Their findings are frustrating, though not surprising. While 89% of hospitals had some form of patient portal, only 65% of those “had links that were easily found, defined as links accessible within two clicks from the home page.”

Furthermore, even in cases where portals were easily found, good instructions on how to use them were missing. Those instructions that did exist centered on rules and restrictions and laying out “terms and conditions” and informing patients on “what not to do,” rather than explaining how to make the most of the experience.

According to the authors, “this focus on curtailing behavior, and the hurdles placed on finding and understanding guidance, suggest that some hospitals may be prioritizing reducing liability over improving the patient experience with portals.”

If we want our patients to use them, portals must be easy to access and intuitive to use. They also must provide value.

Make it meaningful

Patient portals have proliferated exponentially over the last 10 years, thanks to government incentive programs. One such program, known as “meaningful use,” is primarily responsible for this, as it made implementation of a patient portal one of its core requirements.

Sadly, in spite of its oft-reviled name, the meaningful use program never defined patient-friendly standards of usability for patient portals. As a result, current portals just aren’t very good. Patients like my mother-in-law find them to be too numerous, too unfriendly to use, and too limited, so they are not being used to their full potential.

In fact, many institutions may choose not to enable all of the available features in order to limit technical issues and reduce the burden on providers. In the study referenced above, only 63% of portals offered the ability for patients to communicate directly with their physicians, and only 43% offered the ability to refill prescriptions.

When enabled, these functions improve patient engagement and efficiency. Without them, patients are less likely to log on, and physicians are forced to rely on less-efficient telephone calls or traditional letters to communicate results to their patients.

Put the patient, not the portal, at the center

History has all but forgotten the attempts by tech giants such as Google and Microsoft to create personal health records. While these initially seemed like a wonderful concept, they sadly proved to be a total flop. Some patients embraced the idea, but security concerns and the lack of buy-in from EHR vendors significantly limited their uptake.

They may simply have been ahead of their time.

A decade later, wearable technology and telemedicine are ushering in a new era of patient-centric care. Individuals have been embracing a greater share of the responsibility for their own personal health information, yet most EHRs lack the ability to easily incorporate data acquired outside physicians’ offices.

It’s time for EHR vendors to go all in and change that. Instead of enslaving patients to the tyranny of fragmented health records, they should prioritize the creation of a robust, standardized, and portable health record that travels with the patient, not the other way around.

Have any other ideas on how to improve patient engagement? We’d love to hear about them and share them in a future column.

If you want to contribute but don’t have any ideas, we have a suggestion: Ask your mother-in-law. You may be surprised at what you learn!

Dr. Notte is a family physician and associate chief medical information officer for Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Follow him on twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health.

Reference

Lee JL et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Nov 12. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05528-z.

Diagnosing insomnia takes time

Give new patients 1 hour, expert advises

LAS VEGAS – Clinicians should spend 1 hour with patients who present with a chief complaint of insomnia, rather than rushing to a treatment after a 10- to 15-minute office visit, according to John W. Winkelman, MD, PhD.

“Why? Because sleep problems are usually multifactorial, involving psychiatric illness, sleep disorders, medical illness, medication, and poor sleep hygiene/stress,” he said at an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “There are usually many contributing problems, and sleep quality is only as strong as the weakest link. Maybe you don’t have an hour [to meet with new patients], but you need to give adequate time, otherwise you’re not going to do justice to the problem.”

“Ask, ‘what is it that bothers you most about your insomnia? Is it the time awake at night, your total sleep time, or how you feel during the day?’ Because we’re going to use different approaches based on that chief complaint of the insomnia,” said Dr. Winkelman, chief of the Massachusetts General Sleep Disorders Clinical Research Program in the department of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia [CBT-I], for instance, is very good at reducing time awake at night. It won’t increase total sleep time, but it reduces time awake at night dramatically.”

According to the DSM-5, insomnia disorder is marked by dissatisfaction with sleep quality or quantity associated with at least one of the following: difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and early morning awakening. “Just getting up to pee five times a night is not insomnia,” he said. “Just taking an hour and a half to fall asleep at the beginning of the night is not insomnia. There has to be distress or dysfunction related to the sleep disturbance, for a minimum of three times per week for 3 months.”

Most sleep problems are transient, but 25%-30% last more than 1 year. The differential diagnosis for chronic insomnia includes primary psychiatric disorders, medications, substances, restless legs syndrome, sleep schedule disorders, and obstructive sleep apnea.

“In general, we do not order sleep studies in people with insomnia unless we suspect sleep apnea; it’s just a waste of time,” said Dr. Winkelman, who is also a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Indications for polysomnography include loud snoring plus one of the following: daytime sleepiness, witnessed apneas, or refractory hypertension. Other indications include abnormal behaviors or movements during sleep, unexplained excessive daytime sleepiness, and refractory sleep complaints, especially repetitive brief awakenings.

Many common cognitive and behavioral issues can produce or worsen insomnia, including inconsistent bedtimes and wake times. “That irregular schedule wreaks havoc with sleep,” he said. “It messes up the circadian rhythm. Also, homeostatic drive needs to build up: We need to be awake 16 or more hours in order to be sleepy. If people are sleeping until noon on Sundays and then trying to go to bed at their usual time, 10 or 11 at night, they’ve only been awake 10 or 11 hours. That’s why they’re going to have problems falling asleep. Also, a lot of people doze off after dinner in front of the TV. That doesn’t help.”

Spending excessive time in bed can also trigger or worsen insomnia. Dr. Winkelman recommends that people restrict their access to bed to the number of hours it is reasonable to sleep. “I see a lot of people in their 70s and 80s spending 10 hours in bed,” he said. “It doesn’t sound that crazy, but there is no way they’re going to get 10 hours of sleep. It’s physically impossible, so they spend 2 or 3 hours awake at night.” Clock-watching is another no-no. “In the middle of the night you wake up, look at the clock, and say to yourself: ‘Oh my god, I’ve been awake for 3 hours. I have 4 hours left. I need 7 hours. That means I need to go to sleep now!’ ”

An estimated 30%-40% of people with chronic insomnia have a psychiatric disorder. That means “you have to be thorough in your evaluation and act as if you’re doing a structured interview,” Dr. Winkelman said. “Ask about obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, et cetera, so that you understand the complete myriad of psychiatric illnesses, because psychiatric illnesses run in gangs. Comorbidity is generally the rule.”

The first-line treatment for chronic insomnia disorder is CBT-I, a multicomponent approach that includes time-in-bed restriction, stimulus control, cognitive therapy, relaxation therapy, and sleep hygiene. According to Dr. Winkelman, the cornerstone of CBT-I is time-in-bed restriction. “Many people with insomnia are spending 8.5 hours in bed to get 6.5 hours of sleep,” he said. “What you do is restrict access to bed to 6.5 hours; you initially sleep deprive them. Over the first few weeks, they hate you. After a few weeks when they start sleeping well, you start gradually increasing time in bed, but they rarely get back to the 8.5 hours in bed they were spending beforehand.”

Online CBT-I programs such as Sleepio can also be effective for improving sleep latency and wake after sleep onset, but not for total sleep time (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74[1]:68-75). “Not everybody responds to CBT; 50% don’t respond at a couple of months,” he said. “These are the people you need to think about medication for.”

Medications commonly used for chronic insomnia include benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BzRAs) – temazepam, eszopiclone, triazolam, zolpidem, and zaleplon are Food and Drug Administration approved – melatonin agonists, orexin antagonists, sedating antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and dopaminergic antagonists. “Each of the agents in these categories has somewhat similar mechanisms of action, and similar efficacy and contraindications,” Dr. Winkelman said. “The best way to divide the benzodiazepine receptor agonists is based on half-life. How long do you want drug on receptor in somebody with insomnia? Probably not much longer than 8 hours. Nevertheless, some psychiatrists love clonazepam, which has a 40-hour half-life. The circumstances under which clonazepam should be used for insomnia are small, such as in people with a daytime anxiety disorder.”

Consider trying triazolam, zolpidem, and zaleplon for patients who have problems falling asleep, he said, while oxazepam and eszopiclone are sensible options for people who have difficulty falling and staying asleep. Clinical response to BzRAs is common, yet only about half of people who have insomnia remit with one of these agents.

Dr. Winkelman said that patients and physicians often ask him whether BzRAs and other agents used as sleep aids are addictive. Abuse is identified when recurrent use causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems; disability; and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, home, or school. “These are concerns with BzRAs. Misuse and abuse generally occur in younger people. Once you get to 35 years old, misuse rates get very low. In older people, rates of side effects go up.

“Tolerance, physiological and psychological dependence, and nonmedical diversion are also of concern,” he said. However, for the majority of people, BzRA hypnotics are effective and safe.

As for other agents, meta-analyses have demonstrated that melatonin 1-3 mg can help people fall asleep when it’s not being endogenously released. “That’s during the day,” he said. “That might be most relevant for jet lag and for people doing shift work.” Two orexin antagonists on the market for insomnia include suvorexant and lemborexant 10-20 mg. Advantages of these include little abuse liability and few side effects. “In one head-to-head polysomnography study in the elderly, lemborexant was superior to zolpidem 6.25 mg CR on both objective and subjective ability to fall asleep and stay asleep,” Dr. Winkelman said. (JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2[12]:e1918254).

Antidepressants are another treatment option, including mirtazapine 15-30 mg, trazodone 25-100 mg, and amitriptyline and doxepin (10-50 mg). Advantages include little abuse liability, while potential drawbacks include daytime sedation, weight gain, and anticholinergic side effects. Meanwhile, atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine 25-100 mg have long been known to be helpful for sleep. “Advantages are that they’re anxiolytic, they’re mood stabilizing, and there is little abuse liability,” Dr. Winkelman said. “Drawbacks are that they’re probably less effective than BzRAs, they cause daytime sedation, weight gain, risks of extrapyramidal symptoms and glucose and lipid abnormalities.”

Dr. Winkelman said that he uses “a fair amount” of the anticonvulsant gabapentin as a second- or third-line hypnotic agent. “I usually start with 300 mg [at bedtime],” he added. “Drawbacks are that it’s probably less effective than BzRAs; it affects cognition; and can cause daytime sedation, dizziness, and weight gain. There are also concerns about abuse.”

Dr. Winkelman reported that he has received grant/research support from Merck, the RLS Foundation, and Luitpold Pharmaceuticals. He is also a consultant for Advance Medical, Avadel Pharmaceuticals, and UpToDate and is a member of the speakers’ bureau for Luitpold.

Give new patients 1 hour, expert advises

Give new patients 1 hour, expert advises

LAS VEGAS – Clinicians should spend 1 hour with patients who present with a chief complaint of insomnia, rather than rushing to a treatment after a 10- to 15-minute office visit, according to John W. Winkelman, MD, PhD.

“Why? Because sleep problems are usually multifactorial, involving psychiatric illness, sleep disorders, medical illness, medication, and poor sleep hygiene/stress,” he said at an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “There are usually many contributing problems, and sleep quality is only as strong as the weakest link. Maybe you don’t have an hour [to meet with new patients], but you need to give adequate time, otherwise you’re not going to do justice to the problem.”

“Ask, ‘what is it that bothers you most about your insomnia? Is it the time awake at night, your total sleep time, or how you feel during the day?’ Because we’re going to use different approaches based on that chief complaint of the insomnia,” said Dr. Winkelman, chief of the Massachusetts General Sleep Disorders Clinical Research Program in the department of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia [CBT-I], for instance, is very good at reducing time awake at night. It won’t increase total sleep time, but it reduces time awake at night dramatically.”

According to the DSM-5, insomnia disorder is marked by dissatisfaction with sleep quality or quantity associated with at least one of the following: difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and early morning awakening. “Just getting up to pee five times a night is not insomnia,” he said. “Just taking an hour and a half to fall asleep at the beginning of the night is not insomnia. There has to be distress or dysfunction related to the sleep disturbance, for a minimum of three times per week for 3 months.”

Most sleep problems are transient, but 25%-30% last more than 1 year. The differential diagnosis for chronic insomnia includes primary psychiatric disorders, medications, substances, restless legs syndrome, sleep schedule disorders, and obstructive sleep apnea.

“In general, we do not order sleep studies in people with insomnia unless we suspect sleep apnea; it’s just a waste of time,” said Dr. Winkelman, who is also a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Indications for polysomnography include loud snoring plus one of the following: daytime sleepiness, witnessed apneas, or refractory hypertension. Other indications include abnormal behaviors or movements during sleep, unexplained excessive daytime sleepiness, and refractory sleep complaints, especially repetitive brief awakenings.

Many common cognitive and behavioral issues can produce or worsen insomnia, including inconsistent bedtimes and wake times. “That irregular schedule wreaks havoc with sleep,” he said. “It messes up the circadian rhythm. Also, homeostatic drive needs to build up: We need to be awake 16 or more hours in order to be sleepy. If people are sleeping until noon on Sundays and then trying to go to bed at their usual time, 10 or 11 at night, they’ve only been awake 10 or 11 hours. That’s why they’re going to have problems falling asleep. Also, a lot of people doze off after dinner in front of the TV. That doesn’t help.”

Spending excessive time in bed can also trigger or worsen insomnia. Dr. Winkelman recommends that people restrict their access to bed to the number of hours it is reasonable to sleep. “I see a lot of people in their 70s and 80s spending 10 hours in bed,” he said. “It doesn’t sound that crazy, but there is no way they’re going to get 10 hours of sleep. It’s physically impossible, so they spend 2 or 3 hours awake at night.” Clock-watching is another no-no. “In the middle of the night you wake up, look at the clock, and say to yourself: ‘Oh my god, I’ve been awake for 3 hours. I have 4 hours left. I need 7 hours. That means I need to go to sleep now!’ ”

An estimated 30%-40% of people with chronic insomnia have a psychiatric disorder. That means “you have to be thorough in your evaluation and act as if you’re doing a structured interview,” Dr. Winkelman said. “Ask about obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, et cetera, so that you understand the complete myriad of psychiatric illnesses, because psychiatric illnesses run in gangs. Comorbidity is generally the rule.”

The first-line treatment for chronic insomnia disorder is CBT-I, a multicomponent approach that includes time-in-bed restriction, stimulus control, cognitive therapy, relaxation therapy, and sleep hygiene. According to Dr. Winkelman, the cornerstone of CBT-I is time-in-bed restriction. “Many people with insomnia are spending 8.5 hours in bed to get 6.5 hours of sleep,” he said. “What you do is restrict access to bed to 6.5 hours; you initially sleep deprive them. Over the first few weeks, they hate you. After a few weeks when they start sleeping well, you start gradually increasing time in bed, but they rarely get back to the 8.5 hours in bed they were spending beforehand.”

Online CBT-I programs such as Sleepio can also be effective for improving sleep latency and wake after sleep onset, but not for total sleep time (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74[1]:68-75). “Not everybody responds to CBT; 50% don’t respond at a couple of months,” he said. “These are the people you need to think about medication for.”

Medications commonly used for chronic insomnia include benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BzRAs) – temazepam, eszopiclone, triazolam, zolpidem, and zaleplon are Food and Drug Administration approved – melatonin agonists, orexin antagonists, sedating antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and dopaminergic antagonists. “Each of the agents in these categories has somewhat similar mechanisms of action, and similar efficacy and contraindications,” Dr. Winkelman said. “The best way to divide the benzodiazepine receptor agonists is based on half-life. How long do you want drug on receptor in somebody with insomnia? Probably not much longer than 8 hours. Nevertheless, some psychiatrists love clonazepam, which has a 40-hour half-life. The circumstances under which clonazepam should be used for insomnia are small, such as in people with a daytime anxiety disorder.”

Consider trying triazolam, zolpidem, and zaleplon for patients who have problems falling asleep, he said, while oxazepam and eszopiclone are sensible options for people who have difficulty falling and staying asleep. Clinical response to BzRAs is common, yet only about half of people who have insomnia remit with one of these agents.

Dr. Winkelman said that patients and physicians often ask him whether BzRAs and other agents used as sleep aids are addictive. Abuse is identified when recurrent use causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems; disability; and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, home, or school. “These are concerns with BzRAs. Misuse and abuse generally occur in younger people. Once you get to 35 years old, misuse rates get very low. In older people, rates of side effects go up.

“Tolerance, physiological and psychological dependence, and nonmedical diversion are also of concern,” he said. However, for the majority of people, BzRA hypnotics are effective and safe.

As for other agents, meta-analyses have demonstrated that melatonin 1-3 mg can help people fall asleep when it’s not being endogenously released. “That’s during the day,” he said. “That might be most relevant for jet lag and for people doing shift work.” Two orexin antagonists on the market for insomnia include suvorexant and lemborexant 10-20 mg. Advantages of these include little abuse liability and few side effects. “In one head-to-head polysomnography study in the elderly, lemborexant was superior to zolpidem 6.25 mg CR on both objective and subjective ability to fall asleep and stay asleep,” Dr. Winkelman said. (JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2[12]:e1918254).

Antidepressants are another treatment option, including mirtazapine 15-30 mg, trazodone 25-100 mg, and amitriptyline and doxepin (10-50 mg). Advantages include little abuse liability, while potential drawbacks include daytime sedation, weight gain, and anticholinergic side effects. Meanwhile, atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine 25-100 mg have long been known to be helpful for sleep. “Advantages are that they’re anxiolytic, they’re mood stabilizing, and there is little abuse liability,” Dr. Winkelman said. “Drawbacks are that they’re probably less effective than BzRAs, they cause daytime sedation, weight gain, risks of extrapyramidal symptoms and glucose and lipid abnormalities.”

Dr. Winkelman said that he uses “a fair amount” of the anticonvulsant gabapentin as a second- or third-line hypnotic agent. “I usually start with 300 mg [at bedtime],” he added. “Drawbacks are that it’s probably less effective than BzRAs; it affects cognition; and can cause daytime sedation, dizziness, and weight gain. There are also concerns about abuse.”

Dr. Winkelman reported that he has received grant/research support from Merck, the RLS Foundation, and Luitpold Pharmaceuticals. He is also a consultant for Advance Medical, Avadel Pharmaceuticals, and UpToDate and is a member of the speakers’ bureau for Luitpold.

LAS VEGAS – Clinicians should spend 1 hour with patients who present with a chief complaint of insomnia, rather than rushing to a treatment after a 10- to 15-minute office visit, according to John W. Winkelman, MD, PhD.

“Why? Because sleep problems are usually multifactorial, involving psychiatric illness, sleep disorders, medical illness, medication, and poor sleep hygiene/stress,” he said at an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association. “There are usually many contributing problems, and sleep quality is only as strong as the weakest link. Maybe you don’t have an hour [to meet with new patients], but you need to give adequate time, otherwise you’re not going to do justice to the problem.”

“Ask, ‘what is it that bothers you most about your insomnia? Is it the time awake at night, your total sleep time, or how you feel during the day?’ Because we’re going to use different approaches based on that chief complaint of the insomnia,” said Dr. Winkelman, chief of the Massachusetts General Sleep Disorders Clinical Research Program in the department of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia [CBT-I], for instance, is very good at reducing time awake at night. It won’t increase total sleep time, but it reduces time awake at night dramatically.”

According to the DSM-5, insomnia disorder is marked by dissatisfaction with sleep quality or quantity associated with at least one of the following: difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and early morning awakening. “Just getting up to pee five times a night is not insomnia,” he said. “Just taking an hour and a half to fall asleep at the beginning of the night is not insomnia. There has to be distress or dysfunction related to the sleep disturbance, for a minimum of three times per week for 3 months.”

Most sleep problems are transient, but 25%-30% last more than 1 year. The differential diagnosis for chronic insomnia includes primary psychiatric disorders, medications, substances, restless legs syndrome, sleep schedule disorders, and obstructive sleep apnea.

“In general, we do not order sleep studies in people with insomnia unless we suspect sleep apnea; it’s just a waste of time,” said Dr. Winkelman, who is also a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Indications for polysomnography include loud snoring plus one of the following: daytime sleepiness, witnessed apneas, or refractory hypertension. Other indications include abnormal behaviors or movements during sleep, unexplained excessive daytime sleepiness, and refractory sleep complaints, especially repetitive brief awakenings.

Many common cognitive and behavioral issues can produce or worsen insomnia, including inconsistent bedtimes and wake times. “That irregular schedule wreaks havoc with sleep,” he said. “It messes up the circadian rhythm. Also, homeostatic drive needs to build up: We need to be awake 16 or more hours in order to be sleepy. If people are sleeping until noon on Sundays and then trying to go to bed at their usual time, 10 or 11 at night, they’ve only been awake 10 or 11 hours. That’s why they’re going to have problems falling asleep. Also, a lot of people doze off after dinner in front of the TV. That doesn’t help.”

Spending excessive time in bed can also trigger or worsen insomnia. Dr. Winkelman recommends that people restrict their access to bed to the number of hours it is reasonable to sleep. “I see a lot of people in their 70s and 80s spending 10 hours in bed,” he said. “It doesn’t sound that crazy, but there is no way they’re going to get 10 hours of sleep. It’s physically impossible, so they spend 2 or 3 hours awake at night.” Clock-watching is another no-no. “In the middle of the night you wake up, look at the clock, and say to yourself: ‘Oh my god, I’ve been awake for 3 hours. I have 4 hours left. I need 7 hours. That means I need to go to sleep now!’ ”

An estimated 30%-40% of people with chronic insomnia have a psychiatric disorder. That means “you have to be thorough in your evaluation and act as if you’re doing a structured interview,” Dr. Winkelman said. “Ask about obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, et cetera, so that you understand the complete myriad of psychiatric illnesses, because psychiatric illnesses run in gangs. Comorbidity is generally the rule.”

The first-line treatment for chronic insomnia disorder is CBT-I, a multicomponent approach that includes time-in-bed restriction, stimulus control, cognitive therapy, relaxation therapy, and sleep hygiene. According to Dr. Winkelman, the cornerstone of CBT-I is time-in-bed restriction. “Many people with insomnia are spending 8.5 hours in bed to get 6.5 hours of sleep,” he said. “What you do is restrict access to bed to 6.5 hours; you initially sleep deprive them. Over the first few weeks, they hate you. After a few weeks when they start sleeping well, you start gradually increasing time in bed, but they rarely get back to the 8.5 hours in bed they were spending beforehand.”

Online CBT-I programs such as Sleepio can also be effective for improving sleep latency and wake after sleep onset, but not for total sleep time (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74[1]:68-75). “Not everybody responds to CBT; 50% don’t respond at a couple of months,” he said. “These are the people you need to think about medication for.”

Medications commonly used for chronic insomnia include benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BzRAs) – temazepam, eszopiclone, triazolam, zolpidem, and zaleplon are Food and Drug Administration approved – melatonin agonists, orexin antagonists, sedating antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and dopaminergic antagonists. “Each of the agents in these categories has somewhat similar mechanisms of action, and similar efficacy and contraindications,” Dr. Winkelman said. “The best way to divide the benzodiazepine receptor agonists is based on half-life. How long do you want drug on receptor in somebody with insomnia? Probably not much longer than 8 hours. Nevertheless, some psychiatrists love clonazepam, which has a 40-hour half-life. The circumstances under which clonazepam should be used for insomnia are small, such as in people with a daytime anxiety disorder.”

Consider trying triazolam, zolpidem, and zaleplon for patients who have problems falling asleep, he said, while oxazepam and eszopiclone are sensible options for people who have difficulty falling and staying asleep. Clinical response to BzRAs is common, yet only about half of people who have insomnia remit with one of these agents.

Dr. Winkelman said that patients and physicians often ask him whether BzRAs and other agents used as sleep aids are addictive. Abuse is identified when recurrent use causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems; disability; and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, home, or school. “These are concerns with BzRAs. Misuse and abuse generally occur in younger people. Once you get to 35 years old, misuse rates get very low. In older people, rates of side effects go up.

“Tolerance, physiological and psychological dependence, and nonmedical diversion are also of concern,” he said. However, for the majority of people, BzRA hypnotics are effective and safe.

As for other agents, meta-analyses have demonstrated that melatonin 1-3 mg can help people fall asleep when it’s not being endogenously released. “That’s during the day,” he said. “That might be most relevant for jet lag and for people doing shift work.” Two orexin antagonists on the market for insomnia include suvorexant and lemborexant 10-20 mg. Advantages of these include little abuse liability and few side effects. “In one head-to-head polysomnography study in the elderly, lemborexant was superior to zolpidem 6.25 mg CR on both objective and subjective ability to fall asleep and stay asleep,” Dr. Winkelman said. (JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2[12]:e1918254).

Antidepressants are another treatment option, including mirtazapine 15-30 mg, trazodone 25-100 mg, and amitriptyline and doxepin (10-50 mg). Advantages include little abuse liability, while potential drawbacks include daytime sedation, weight gain, and anticholinergic side effects. Meanwhile, atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine 25-100 mg have long been known to be helpful for sleep. “Advantages are that they’re anxiolytic, they’re mood stabilizing, and there is little abuse liability,” Dr. Winkelman said. “Drawbacks are that they’re probably less effective than BzRAs, they cause daytime sedation, weight gain, risks of extrapyramidal symptoms and glucose and lipid abnormalities.”

Dr. Winkelman said that he uses “a fair amount” of the anticonvulsant gabapentin as a second- or third-line hypnotic agent. “I usually start with 300 mg [at bedtime],” he added. “Drawbacks are that it’s probably less effective than BzRAs; it affects cognition; and can cause daytime sedation, dizziness, and weight gain. There are also concerns about abuse.”

Dr. Winkelman reported that he has received grant/research support from Merck, the RLS Foundation, and Luitpold Pharmaceuticals. He is also a consultant for Advance Medical, Avadel Pharmaceuticals, and UpToDate and is a member of the speakers’ bureau for Luitpold.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NPA 2020

Supreme Court roundup: Latest health care decisions

The Trump administration can move forward with expanding a rule that makes it more difficult for immigrants to remain in the United States if they receive health care assistance, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 vote.

The Feb. 21 order allows the administration to broaden the so-called “public charge rule” while legal challenges against the expanded regulation continue in the lower courts. The Supreme Court’s decision, which lifts a preliminary injunction against the expansion, applies to enforcement only in Illinois, where a district court blocked the revised rule from moving forward in October 2019. The Supreme Court’s measure follows another 5-4 order in January, in which justices lifted a nationwide injunction against the revised rule.

Under the long-standing public charge rule, immigration officials can refuse to admit immigrants into the United States or can deny them permanent legal status if they are deemed likely to become a public charge. Previously, immigration officers considered cash aid, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or long-term institutionalized care, as potential public charge reasons for denial.

The revised regulation allows officials to consider previously excluded programs in their determination, including nonemergency Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and several housing programs. Use of these programs for more than 12 months in the aggregate during a 36-month period may result in a “public charge” designation and lead to green card denial.

Eight legal challenges were immediately filed against the rule changes, including a complaint issued by 14 states. At least five trial courts have since blocked the measure, while appeals courts have lifted some of the injunctions and upheld enforcement.

In its Jan. 27 order lifting the nationwide injunction, Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch wrote that nationwide injunctions are being overused by trial courts with negative consequences.

“The real problem here is the increasingly common practice of trial courts ordering relief that transcends the cases before them. Whether framed as injunctions of ‘nationwide,’ ‘universal,’ or ‘cosmic’ scope, these orders share the same basic flaw – they direct how the defendant must act toward persons who are not parties to the case,” he wrote. “It has become increasingly apparent that this court must, at some point, confront these important objections to this increasingly widespread practice. As the brief and furious history of the regulation before us illustrates, the routine issuance of universal injunctions is patently unworkable, sowing chaos for litigants, the government, courts, and all those affected by these conflicting decisions.”

In the court’s Feb. 21 order lifting the injunction in Illinois, justices gave no explanation for overturning the lower court’s injunction. However, Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor issued a sharply-worded dissent, criticizing her fellow justices for allowing the rule to proceed.

“In sum, the government’s only claimed hardship is that it must enforce an existing interpretation of an immigration rule in one state – just as it has done for the past 20 years – while an updated version of the rule takes effect in the remaining 49,” she wrote. “The government has not quantified or explained any burdens that would arise from this state of the world.”

ACA cases still in limbo

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court still has not decided whether it will hear Texas v. United States, a case that could effectively dismantle the Affordable Care Act.

The high court was expected to announce whether it would take the high-profile case at a private Feb. 21 conference, but the justices have released no update. The case was relisted for consideration at the court’s Feb. 28 conference.

Texas v. United States stems from a lawsuit by 20 Republican state attorneys general and governors that was filed after Congress zeroed out the ACA’s individual mandate penalty in 2017. The plaintiffs contend the now-valueless mandate is no longer constitutional and thus, the entire ACA should be struck down. Because the Trump administration declined to defend the law, a coalition of Democratic attorneys general and governors intervened in the case as defendants.

In 2018, a Texas district court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and declared the entire health care law invalid. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals partially affirmed the district court’s decision, ruling that the mandate was unconstitutional, but sending the case back to the lower court for more analysis on severability. The Democratic attorneys general and governors appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

If the Supreme Court agrees to hear the challenge, the court could fast-track the case and schedule arguments for the current term or wait until its next term, which starts in October 2020. If justices decline to hear the case, the challenge will remain with the district court for more analysis about the law’s severability.

Another ACA-related case – Maine Community Health Options v. U.S. – also remains in limbo. Justices heard the case, which was consolidated with two similar challenges, on Dec. 10, 2019, but still have not issued a decision.

The consolidated challenges center on whether the federal government owes insurers billions based on an Affordable Care Act provision intended to help health plans mitigate risk under the law. The ACA’s risk corridor program required the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services to collect funds from profitable insurers that offered qualified health plans under the exchanges and distribute the funds to insurers with excessive losses. Collections from profitable insurers under the program fell short in 2014, 2015, and 2016, while losses steadily grew, resulting in the HHS paying about 12 cents on the dollar in payments to insurers. More than 150 insurers now allege they were shortchanged and they want the Supreme Court to force the government to reimburse them to the tune of $12 billion.

The Department of Justice counters that the government is not required to pay the insurers because of appropriations measures passed by Congress in 2014 and in later years that limited the funding available to compensate insurers for their losses.

The federal government and insurers have each experienced wins and losses at the lower court level. Most recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided in favor of the government, ruling that while the ACA required the government to compensate the insurers for their losses, the appropriations measures repealed or suspended that requirement.

A Supreme Court decision in the case could come as soon as Feb. 26.

Court to hear women’s health cases

Two closely watched reproductive health cases will go before the court this spring.

On March 4, justices will hear oral arguments in June Medical Services v. Russo, regarding the constitutionality of a Louisiana law that requires physicians performing abortions to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. Doctors who perform abortions without admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles face fines and imprisonment, according to the state law, originally passed in 2014. Clinics that employ such doctors can also have their licenses revoked.

June Medical Services LLC, a women’s health clinic, sued over the law. A district court ruled in favor of the plaintiff, but the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and upheld Louisiana’s law. The clinic appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Louisiana officials argue the challenge should be dismissed, and the law allowed to proceed, because the plaintiffs lack standing.

The Supreme Court in 2016 heard a similar case – Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt – concerning a comparable law in Texas. In that case, justices struck down the measure as unconstitutional.

And on April 29, justices will hear arguments in Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania, a consolidated case about whether the Trump administration acted properly when it expanded exemptions under the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate. Entities that object to providing contraception on the basis of religious beliefs can opt out of complying with the mandate, according to the 2018 regulations. Additionally, nonprofit organizations and small businesses that have nonreligious moral convictions against the mandate can skip compliance. A number of states and entities sued over the new rules.

A federal appeals court temporarily barred the regulations from moving forward, ruling the plaintiffs were likely to succeed in proving the Trump administration did not follow appropriate procedures when it promulgated the new rules and that the regulations were not authorized under the ACA.

Justices will decide whether the parties have standing in the case, whether the Trump administration followed correct rule-making procedures, and if the regulations can stand.

The Trump administration can move forward with expanding a rule that makes it more difficult for immigrants to remain in the United States if they receive health care assistance, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 vote.

The Feb. 21 order allows the administration to broaden the so-called “public charge rule” while legal challenges against the expanded regulation continue in the lower courts. The Supreme Court’s decision, which lifts a preliminary injunction against the expansion, applies to enforcement only in Illinois, where a district court blocked the revised rule from moving forward in October 2019. The Supreme Court’s measure follows another 5-4 order in January, in which justices lifted a nationwide injunction against the revised rule.

Under the long-standing public charge rule, immigration officials can refuse to admit immigrants into the United States or can deny them permanent legal status if they are deemed likely to become a public charge. Previously, immigration officers considered cash aid, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or long-term institutionalized care, as potential public charge reasons for denial.

The revised regulation allows officials to consider previously excluded programs in their determination, including nonemergency Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and several housing programs. Use of these programs for more than 12 months in the aggregate during a 36-month period may result in a “public charge” designation and lead to green card denial.

Eight legal challenges were immediately filed against the rule changes, including a complaint issued by 14 states. At least five trial courts have since blocked the measure, while appeals courts have lifted some of the injunctions and upheld enforcement.

In its Jan. 27 order lifting the nationwide injunction, Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch wrote that nationwide injunctions are being overused by trial courts with negative consequences.

“The real problem here is the increasingly common practice of trial courts ordering relief that transcends the cases before them. Whether framed as injunctions of ‘nationwide,’ ‘universal,’ or ‘cosmic’ scope, these orders share the same basic flaw – they direct how the defendant must act toward persons who are not parties to the case,” he wrote. “It has become increasingly apparent that this court must, at some point, confront these important objections to this increasingly widespread practice. As the brief and furious history of the regulation before us illustrates, the routine issuance of universal injunctions is patently unworkable, sowing chaos for litigants, the government, courts, and all those affected by these conflicting decisions.”

In the court’s Feb. 21 order lifting the injunction in Illinois, justices gave no explanation for overturning the lower court’s injunction. However, Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor issued a sharply-worded dissent, criticizing her fellow justices for allowing the rule to proceed.

“In sum, the government’s only claimed hardship is that it must enforce an existing interpretation of an immigration rule in one state – just as it has done for the past 20 years – while an updated version of the rule takes effect in the remaining 49,” she wrote. “The government has not quantified or explained any burdens that would arise from this state of the world.”

ACA cases still in limbo

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court still has not decided whether it will hear Texas v. United States, a case that could effectively dismantle the Affordable Care Act.

The high court was expected to announce whether it would take the high-profile case at a private Feb. 21 conference, but the justices have released no update. The case was relisted for consideration at the court’s Feb. 28 conference.

Texas v. United States stems from a lawsuit by 20 Republican state attorneys general and governors that was filed after Congress zeroed out the ACA’s individual mandate penalty in 2017. The plaintiffs contend the now-valueless mandate is no longer constitutional and thus, the entire ACA should be struck down. Because the Trump administration declined to defend the law, a coalition of Democratic attorneys general and governors intervened in the case as defendants.

In 2018, a Texas district court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and declared the entire health care law invalid. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals partially affirmed the district court’s decision, ruling that the mandate was unconstitutional, but sending the case back to the lower court for more analysis on severability. The Democratic attorneys general and governors appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

If the Supreme Court agrees to hear the challenge, the court could fast-track the case and schedule arguments for the current term or wait until its next term, which starts in October 2020. If justices decline to hear the case, the challenge will remain with the district court for more analysis about the law’s severability.

Another ACA-related case – Maine Community Health Options v. U.S. – also remains in limbo. Justices heard the case, which was consolidated with two similar challenges, on Dec. 10, 2019, but still have not issued a decision.

The consolidated challenges center on whether the federal government owes insurers billions based on an Affordable Care Act provision intended to help health plans mitigate risk under the law. The ACA’s risk corridor program required the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services to collect funds from profitable insurers that offered qualified health plans under the exchanges and distribute the funds to insurers with excessive losses. Collections from profitable insurers under the program fell short in 2014, 2015, and 2016, while losses steadily grew, resulting in the HHS paying about 12 cents on the dollar in payments to insurers. More than 150 insurers now allege they were shortchanged and they want the Supreme Court to force the government to reimburse them to the tune of $12 billion.

The Department of Justice counters that the government is not required to pay the insurers because of appropriations measures passed by Congress in 2014 and in later years that limited the funding available to compensate insurers for their losses.

The federal government and insurers have each experienced wins and losses at the lower court level. Most recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided in favor of the government, ruling that while the ACA required the government to compensate the insurers for their losses, the appropriations measures repealed or suspended that requirement.

A Supreme Court decision in the case could come as soon as Feb. 26.

Court to hear women’s health cases

Two closely watched reproductive health cases will go before the court this spring.

On March 4, justices will hear oral arguments in June Medical Services v. Russo, regarding the constitutionality of a Louisiana law that requires physicians performing abortions to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. Doctors who perform abortions without admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles face fines and imprisonment, according to the state law, originally passed in 2014. Clinics that employ such doctors can also have their licenses revoked.

June Medical Services LLC, a women’s health clinic, sued over the law. A district court ruled in favor of the plaintiff, but the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and upheld Louisiana’s law. The clinic appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Louisiana officials argue the challenge should be dismissed, and the law allowed to proceed, because the plaintiffs lack standing.

The Supreme Court in 2016 heard a similar case – Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt – concerning a comparable law in Texas. In that case, justices struck down the measure as unconstitutional.

And on April 29, justices will hear arguments in Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania, a consolidated case about whether the Trump administration acted properly when it expanded exemptions under the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate. Entities that object to providing contraception on the basis of religious beliefs can opt out of complying with the mandate, according to the 2018 regulations. Additionally, nonprofit organizations and small businesses that have nonreligious moral convictions against the mandate can skip compliance. A number of states and entities sued over the new rules.

A federal appeals court temporarily barred the regulations from moving forward, ruling the plaintiffs were likely to succeed in proving the Trump administration did not follow appropriate procedures when it promulgated the new rules and that the regulations were not authorized under the ACA.

Justices will decide whether the parties have standing in the case, whether the Trump administration followed correct rule-making procedures, and if the regulations can stand.

The Trump administration can move forward with expanding a rule that makes it more difficult for immigrants to remain in the United States if they receive health care assistance, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 vote.

The Feb. 21 order allows the administration to broaden the so-called “public charge rule” while legal challenges against the expanded regulation continue in the lower courts. The Supreme Court’s decision, which lifts a preliminary injunction against the expansion, applies to enforcement only in Illinois, where a district court blocked the revised rule from moving forward in October 2019. The Supreme Court’s measure follows another 5-4 order in January, in which justices lifted a nationwide injunction against the revised rule.

Under the long-standing public charge rule, immigration officials can refuse to admit immigrants into the United States or can deny them permanent legal status if they are deemed likely to become a public charge. Previously, immigration officers considered cash aid, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or long-term institutionalized care, as potential public charge reasons for denial.

The revised regulation allows officials to consider previously excluded programs in their determination, including nonemergency Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and several housing programs. Use of these programs for more than 12 months in the aggregate during a 36-month period may result in a “public charge” designation and lead to green card denial.

Eight legal challenges were immediately filed against the rule changes, including a complaint issued by 14 states. At least five trial courts have since blocked the measure, while appeals courts have lifted some of the injunctions and upheld enforcement.

In its Jan. 27 order lifting the nationwide injunction, Associate Justice Neil M. Gorsuch wrote that nationwide injunctions are being overused by trial courts with negative consequences.

“The real problem here is the increasingly common practice of trial courts ordering relief that transcends the cases before them. Whether framed as injunctions of ‘nationwide,’ ‘universal,’ or ‘cosmic’ scope, these orders share the same basic flaw – they direct how the defendant must act toward persons who are not parties to the case,” he wrote. “It has become increasingly apparent that this court must, at some point, confront these important objections to this increasingly widespread practice. As the brief and furious history of the regulation before us illustrates, the routine issuance of universal injunctions is patently unworkable, sowing chaos for litigants, the government, courts, and all those affected by these conflicting decisions.”

In the court’s Feb. 21 order lifting the injunction in Illinois, justices gave no explanation for overturning the lower court’s injunction. However, Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor issued a sharply-worded dissent, criticizing her fellow justices for allowing the rule to proceed.

“In sum, the government’s only claimed hardship is that it must enforce an existing interpretation of an immigration rule in one state – just as it has done for the past 20 years – while an updated version of the rule takes effect in the remaining 49,” she wrote. “The government has not quantified or explained any burdens that would arise from this state of the world.”

ACA cases still in limbo

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court still has not decided whether it will hear Texas v. United States, a case that could effectively dismantle the Affordable Care Act.

The high court was expected to announce whether it would take the high-profile case at a private Feb. 21 conference, but the justices have released no update. The case was relisted for consideration at the court’s Feb. 28 conference.

Texas v. United States stems from a lawsuit by 20 Republican state attorneys general and governors that was filed after Congress zeroed out the ACA’s individual mandate penalty in 2017. The plaintiffs contend the now-valueless mandate is no longer constitutional and thus, the entire ACA should be struck down. Because the Trump administration declined to defend the law, a coalition of Democratic attorneys general and governors intervened in the case as defendants.

In 2018, a Texas district court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and declared the entire health care law invalid. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals partially affirmed the district court’s decision, ruling that the mandate was unconstitutional, but sending the case back to the lower court for more analysis on severability. The Democratic attorneys general and governors appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

If the Supreme Court agrees to hear the challenge, the court could fast-track the case and schedule arguments for the current term or wait until its next term, which starts in October 2020. If justices decline to hear the case, the challenge will remain with the district court for more analysis about the law’s severability.

Another ACA-related case – Maine Community Health Options v. U.S. – also remains in limbo. Justices heard the case, which was consolidated with two similar challenges, on Dec. 10, 2019, but still have not issued a decision.

The consolidated challenges center on whether the federal government owes insurers billions based on an Affordable Care Act provision intended to help health plans mitigate risk under the law. The ACA’s risk corridor program required the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services to collect funds from profitable insurers that offered qualified health plans under the exchanges and distribute the funds to insurers with excessive losses. Collections from profitable insurers under the program fell short in 2014, 2015, and 2016, while losses steadily grew, resulting in the HHS paying about 12 cents on the dollar in payments to insurers. More than 150 insurers now allege they were shortchanged and they want the Supreme Court to force the government to reimburse them to the tune of $12 billion.

The Department of Justice counters that the government is not required to pay the insurers because of appropriations measures passed by Congress in 2014 and in later years that limited the funding available to compensate insurers for their losses.

The federal government and insurers have each experienced wins and losses at the lower court level. Most recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decided in favor of the government, ruling that while the ACA required the government to compensate the insurers for their losses, the appropriations measures repealed or suspended that requirement.

A Supreme Court decision in the case could come as soon as Feb. 26.

Court to hear women’s health cases

Two closely watched reproductive health cases will go before the court this spring.

On March 4, justices will hear oral arguments in June Medical Services v. Russo, regarding the constitutionality of a Louisiana law that requires physicians performing abortions to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. Doctors who perform abortions without admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles face fines and imprisonment, according to the state law, originally passed in 2014. Clinics that employ such doctors can also have their licenses revoked.

June Medical Services LLC, a women’s health clinic, sued over the law. A district court ruled in favor of the plaintiff, but the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and upheld Louisiana’s law. The clinic appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Louisiana officials argue the challenge should be dismissed, and the law allowed to proceed, because the plaintiffs lack standing.

The Supreme Court in 2016 heard a similar case – Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt – concerning a comparable law in Texas. In that case, justices struck down the measure as unconstitutional.

And on April 29, justices will hear arguments in Little Sisters of the Poor v. Pennsylvania, a consolidated case about whether the Trump administration acted properly when it expanded exemptions under the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate. Entities that object to providing contraception on the basis of religious beliefs can opt out of complying with the mandate, according to the 2018 regulations. Additionally, nonprofit organizations and small businesses that have nonreligious moral convictions against the mandate can skip compliance. A number of states and entities sued over the new rules.

A federal appeals court temporarily barred the regulations from moving forward, ruling the plaintiffs were likely to succeed in proving the Trump administration did not follow appropriate procedures when it promulgated the new rules and that the regulations were not authorized under the ACA.

Justices will decide whether the parties have standing in the case, whether the Trump administration followed correct rule-making procedures, and if the regulations can stand.

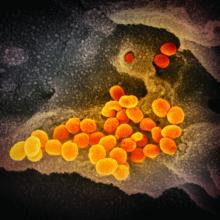

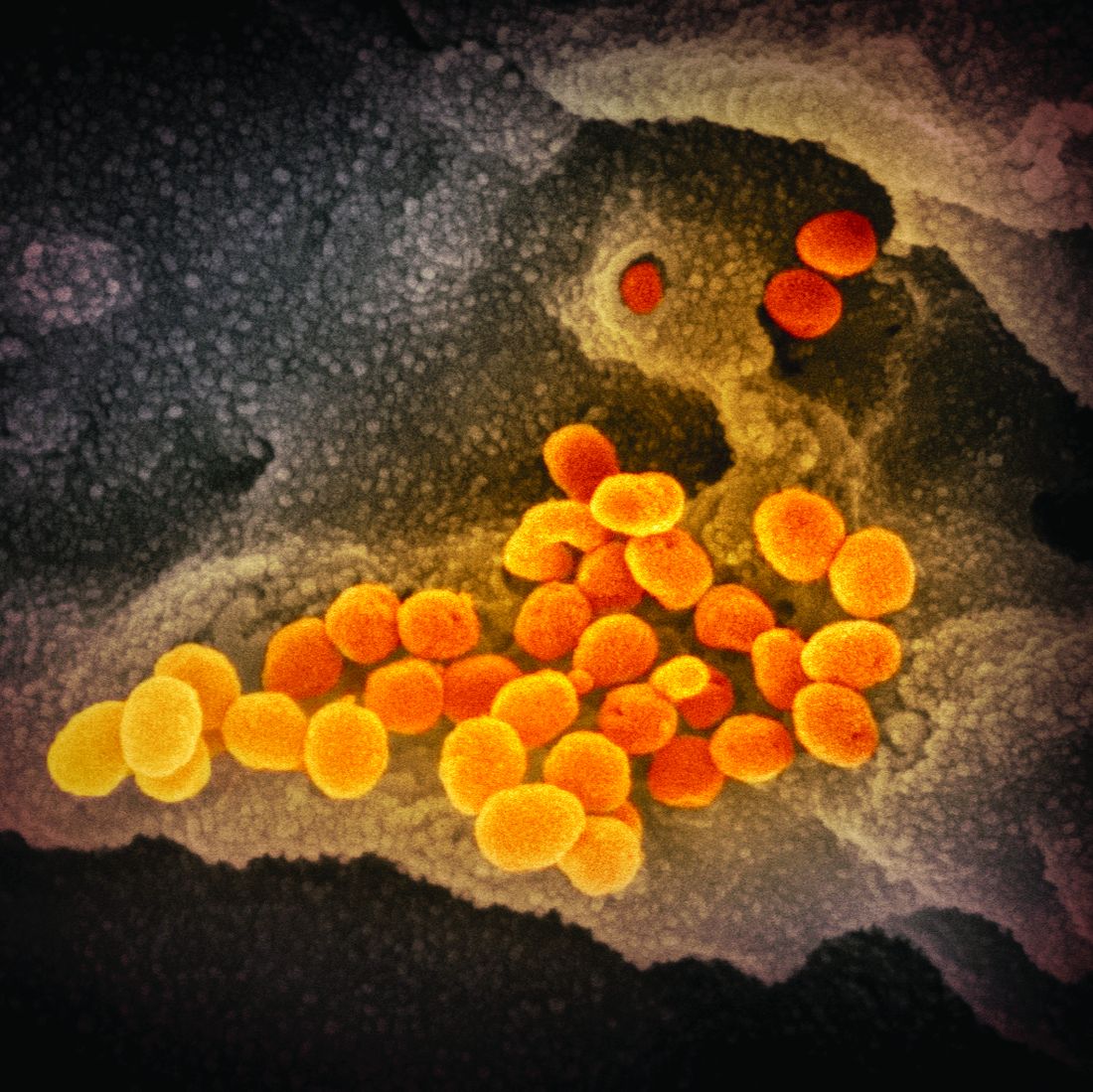

COVID-19: Time to ‘take the risk of scaring people’

It’s past time to call the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, a pandemic and “time to push people to prepare, and guide their prep,” according to risk communication experts.

Medical messaging about containing or stopping the spread of the virus is doing more harm than good, write Peter Sandman, PhD, and Jody Lanard, MD, both based in New York City, in a recent blog post.

“We are near-certain that the desperate-sounding last-ditch containment messaging of recent days is contributing to a massive global misperception,” they warn.

“The most crucial (and overdue) risk communication task … is to help people visualize their communities when ‘keeping it out’ – containment – is no longer relevant.”

That message is embraced by several experts who spoke to Medscape Medical News.

“I’m jealous of what [they] have written: It is so clear, so correct, and so practical,” said David Fisman, MD, MPH, professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto, Canada. “I think WHO [World Health Organization] is shying away from the P word,” he continued, referring to the organization’s continuing decision not to call the outbreak a pandemic.

“I fully support exactly what [Sandman and Lanard] are saying,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, MPH, professor of environmental health sciences and director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Sandman and Lanard write. “Hardly any officials are telling civil society and the general public how to get ready for this pandemic.”

Effective communication should inform people of what to expect now, they continue: “[T]he end of most quarantines, travel restrictions, contact tracing, and other measures designed to keep ‘them’ from infecting ‘us,’ and the switch to measures like canceling mass events designed to keep us from infecting each other.”

Among the new messages that should be delivered are things like:

- Stockpiling nonperishable food and prescription meds.

- Considering care of sick family members.

- Cross-training work personnel so one person’s absence won’t derail an organization’s ability to function.

“We hope that governments and healthcare institutions are using this time wisely,” Sandman and Lanard continue. “We know that ordinary citizens are not being asked to do so. In most countries … ordinary citizens have not been asked to prepare. Instead, they have been led to expect that their governments will keep the virus from their doors.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s past time to call the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, a pandemic and “time to push people to prepare, and guide their prep,” according to risk communication experts.

Medical messaging about containing or stopping the spread of the virus is doing more harm than good, write Peter Sandman, PhD, and Jody Lanard, MD, both based in New York City, in a recent blog post.

“We are near-certain that the desperate-sounding last-ditch containment messaging of recent days is contributing to a massive global misperception,” they warn.

“The most crucial (and overdue) risk communication task … is to help people visualize their communities when ‘keeping it out’ – containment – is no longer relevant.”

That message is embraced by several experts who spoke to Medscape Medical News.

“I’m jealous of what [they] have written: It is so clear, so correct, and so practical,” said David Fisman, MD, MPH, professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto, Canada. “I think WHO [World Health Organization] is shying away from the P word,” he continued, referring to the organization’s continuing decision not to call the outbreak a pandemic.

“I fully support exactly what [Sandman and Lanard] are saying,” said Michael Osterholm, PhD, MPH, professor of environmental health sciences and director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Sandman and Lanard write. “Hardly any officials are telling civil society and the general public how to get ready for this pandemic.”

Effective communication should inform people of what to expect now, they continue: “[T]he end of most quarantines, travel restrictions, contact tracing, and other measures designed to keep ‘them’ from infecting ‘us,’ and the switch to measures like canceling mass events designed to keep us from infecting each other.”

Among the new messages that should be delivered are things like:

- Stockpiling nonperishable food and prescription meds.

- Considering care of sick family members.

- Cross-training work personnel so one person’s absence won’t derail an organization’s ability to function.