User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Lung volume reduction methods show similar results for emphysema

BARCELONA – For patients with emphysema who are suitable candidates for lung volume reduction surgery, in a randomized trial.

Among patients with emphysema amenable to surgery, there were similar improvements between the treatment groups at 12-month follow-up as assessed by the iBODE score, a composite disease severity measure incorporating body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity (incremental shuttle walk test), reported Sara Buttery, BSc, a research physiotherapist and PhD candidate at the National Heart and Lung Institute at Imperial College London.

“Until now there had been no direct comparison of the two to inform decision-making when a person seems to be suitable for either. Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction is a less invasive option and is thought to be ‘less risky’ but, until now, there has not been substantial research to support this,” she said at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Ms. Buttery and colleagues conducted a randomized, controlled, single-blinded superiority trial to see whether LVRS could be superior to BLVR with valves. They enrolled 88 patients (52% male) with a mean age of 64, and randomly assigned them to receive either LVRS (41 patients) or the less-invasive BLVR (47 patients).

As noted before, there were no significant differences in outcomes at 1 year, with similar degrees of improvement between the surgical techniques for both the composite iBODE score (–1.10 for LVRS vs. –0.82 for BLVR, nonsignificant), and for the individual components of the score.

In addition, the treatments were associated with similar reductions in gas trapping, with residual volume percentage predicted –36.1 with LVRS versus –30.5 with BLVR (nonsignificant).

One patient in each group died during the 12 months of follow-up. The death of the patient in the BLVR group was deemed to be treatment related; the death of the patient in the LVRS group was related to a noninfective exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Invited discussant Isabelle Opitz, MD, from University Hospital Zürich told Ms. Buttery: “I have to congratulate you for this very first randomized controlled trial comparing both procedures in a superiority design.”

She pointed out, however, that the number of patients lost to follow-up and crossover of some patients randomized to bronchoscopy raised questions about the powering of the study.

“We did a sensitivity analysis to have a look to see if there was any difference between the patients who did return and the ones who didn’t, and there was no difference at baseline between those patients.” Ms. Buttery said.

She noted that follow-up visits were hampered by the COVID-19 pandemic and the inability of many patients to come into the clinic.

Dr. Opitz also asked about COPD Assessment Test (CAT) scores that were included in the trial design but not reported in the presentation. Ms. Buttery said that the CAT results favored the LVRS group, and that the results would be included in a future economic analysis.

“The results from this first randomized controlled trial suggest that BLVR may be a good therapeutic option for those patients for whom either procedure is suitable,” said Alexander Mathioudakis, MD, PhD, from the University of Manchester (England), who was not involved with this study but commented on it in a press statement. “Lung volume reduction surgery is an invasive operation as it requires a small incision to be made in the chest, which is stitched up after the procedure. As such, it has risks associated with surgery and it takes longer to recover from than bronchoscopic lung volume reduction. On the other hand, endobronchial valves placement is also associated with side effects, such as pneumonia, or valve displacement. Therefore, both the safety and effectiveness of the two procedures need to be investigated further, in larger groups of patients, but the results from this trial are very encouraging.”

The study is supported by the U.K. National Institute of Health Research. Ms. Buttery, Dr. Opitz, and Dr. Mathioudakis reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BARCELONA – For patients with emphysema who are suitable candidates for lung volume reduction surgery, in a randomized trial.

Among patients with emphysema amenable to surgery, there were similar improvements between the treatment groups at 12-month follow-up as assessed by the iBODE score, a composite disease severity measure incorporating body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity (incremental shuttle walk test), reported Sara Buttery, BSc, a research physiotherapist and PhD candidate at the National Heart and Lung Institute at Imperial College London.

“Until now there had been no direct comparison of the two to inform decision-making when a person seems to be suitable for either. Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction is a less invasive option and is thought to be ‘less risky’ but, until now, there has not been substantial research to support this,” she said at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Ms. Buttery and colleagues conducted a randomized, controlled, single-blinded superiority trial to see whether LVRS could be superior to BLVR with valves. They enrolled 88 patients (52% male) with a mean age of 64, and randomly assigned them to receive either LVRS (41 patients) or the less-invasive BLVR (47 patients).

As noted before, there were no significant differences in outcomes at 1 year, with similar degrees of improvement between the surgical techniques for both the composite iBODE score (–1.10 for LVRS vs. –0.82 for BLVR, nonsignificant), and for the individual components of the score.

In addition, the treatments were associated with similar reductions in gas trapping, with residual volume percentage predicted –36.1 with LVRS versus –30.5 with BLVR (nonsignificant).

One patient in each group died during the 12 months of follow-up. The death of the patient in the BLVR group was deemed to be treatment related; the death of the patient in the LVRS group was related to a noninfective exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Invited discussant Isabelle Opitz, MD, from University Hospital Zürich told Ms. Buttery: “I have to congratulate you for this very first randomized controlled trial comparing both procedures in a superiority design.”

She pointed out, however, that the number of patients lost to follow-up and crossover of some patients randomized to bronchoscopy raised questions about the powering of the study.

“We did a sensitivity analysis to have a look to see if there was any difference between the patients who did return and the ones who didn’t, and there was no difference at baseline between those patients.” Ms. Buttery said.

She noted that follow-up visits were hampered by the COVID-19 pandemic and the inability of many patients to come into the clinic.

Dr. Opitz also asked about COPD Assessment Test (CAT) scores that were included in the trial design but not reported in the presentation. Ms. Buttery said that the CAT results favored the LVRS group, and that the results would be included in a future economic analysis.

“The results from this first randomized controlled trial suggest that BLVR may be a good therapeutic option for those patients for whom either procedure is suitable,” said Alexander Mathioudakis, MD, PhD, from the University of Manchester (England), who was not involved with this study but commented on it in a press statement. “Lung volume reduction surgery is an invasive operation as it requires a small incision to be made in the chest, which is stitched up after the procedure. As such, it has risks associated with surgery and it takes longer to recover from than bronchoscopic lung volume reduction. On the other hand, endobronchial valves placement is also associated with side effects, such as pneumonia, or valve displacement. Therefore, both the safety and effectiveness of the two procedures need to be investigated further, in larger groups of patients, but the results from this trial are very encouraging.”

The study is supported by the U.K. National Institute of Health Research. Ms. Buttery, Dr. Opitz, and Dr. Mathioudakis reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BARCELONA – For patients with emphysema who are suitable candidates for lung volume reduction surgery, in a randomized trial.

Among patients with emphysema amenable to surgery, there were similar improvements between the treatment groups at 12-month follow-up as assessed by the iBODE score, a composite disease severity measure incorporating body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity (incremental shuttle walk test), reported Sara Buttery, BSc, a research physiotherapist and PhD candidate at the National Heart and Lung Institute at Imperial College London.

“Until now there had been no direct comparison of the two to inform decision-making when a person seems to be suitable for either. Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction is a less invasive option and is thought to be ‘less risky’ but, until now, there has not been substantial research to support this,” she said at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Ms. Buttery and colleagues conducted a randomized, controlled, single-blinded superiority trial to see whether LVRS could be superior to BLVR with valves. They enrolled 88 patients (52% male) with a mean age of 64, and randomly assigned them to receive either LVRS (41 patients) or the less-invasive BLVR (47 patients).

As noted before, there were no significant differences in outcomes at 1 year, with similar degrees of improvement between the surgical techniques for both the composite iBODE score (–1.10 for LVRS vs. –0.82 for BLVR, nonsignificant), and for the individual components of the score.

In addition, the treatments were associated with similar reductions in gas trapping, with residual volume percentage predicted –36.1 with LVRS versus –30.5 with BLVR (nonsignificant).

One patient in each group died during the 12 months of follow-up. The death of the patient in the BLVR group was deemed to be treatment related; the death of the patient in the LVRS group was related to a noninfective exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Invited discussant Isabelle Opitz, MD, from University Hospital Zürich told Ms. Buttery: “I have to congratulate you for this very first randomized controlled trial comparing both procedures in a superiority design.”

She pointed out, however, that the number of patients lost to follow-up and crossover of some patients randomized to bronchoscopy raised questions about the powering of the study.

“We did a sensitivity analysis to have a look to see if there was any difference between the patients who did return and the ones who didn’t, and there was no difference at baseline between those patients.” Ms. Buttery said.

She noted that follow-up visits were hampered by the COVID-19 pandemic and the inability of many patients to come into the clinic.

Dr. Opitz also asked about COPD Assessment Test (CAT) scores that were included in the trial design but not reported in the presentation. Ms. Buttery said that the CAT results favored the LVRS group, and that the results would be included in a future economic analysis.

“The results from this first randomized controlled trial suggest that BLVR may be a good therapeutic option for those patients for whom either procedure is suitable,” said Alexander Mathioudakis, MD, PhD, from the University of Manchester (England), who was not involved with this study but commented on it in a press statement. “Lung volume reduction surgery is an invasive operation as it requires a small incision to be made in the chest, which is stitched up after the procedure. As such, it has risks associated with surgery and it takes longer to recover from than bronchoscopic lung volume reduction. On the other hand, endobronchial valves placement is also associated with side effects, such as pneumonia, or valve displacement. Therefore, both the safety and effectiveness of the two procedures need to be investigated further, in larger groups of patients, but the results from this trial are very encouraging.”

The study is supported by the U.K. National Institute of Health Research. Ms. Buttery, Dr. Opitz, and Dr. Mathioudakis reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ERS 2022 CONGRESS

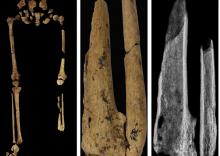

‘Dr. Caveman’ had a leg up on amputation

Monkey see, monkey do (advanced medical procedures)

We don’t tend to think too kindly of our prehistoric ancestors. We throw around the word “caveman” – hardly a term of endearment – and depictions of Paleolithic humans rarely flatter their subjects. In many ways, though, our conceptions are correct. Humans of the Stone Age lived short, often brutish lives, but civilization had to start somewhere, and our prehistoric ancestors were often far more capable than we give them credit for.

Case in point is a recent discovery from an archaeological dig in Borneo: A young adult who lived 31,000 years ago was discovered with the lower third of their left leg amputated. Save the clever retort about the person’s untimely death, because this individual did not die from the surgery. The amputation occurred when the individual was a child and the subject lived for several years after the operation.

Amputation is usually unnecessary given our current level of medical technology, but it’s actually quite an advanced procedure, and this example predates the previous first case of amputation by nearly 25,000 years. Not only did the surgeon need to cut at an appropriate place, they needed to understand blood loss, the risk of infection, and the need to preserve skin in order to seal the wound back up. That’s quite a lot for our Paleolithic doctor to know, and it’s even more impressive considering the, shall we say, limited tools they would have had available to perform the operation.

Rocks. They cut off the leg with a rock. And it worked.

This discovery also gives insight into the amputee’s society. Someone knew that amputation was the right move for this person, indicating that it had been done before. In addition, the individual would not have been able to spring back into action hunting mammoths right away, they would require care for the rest of their lives. And clearly the community provided, given the individual’s continued life post operation and their burial in a place of honor.

If only the American health care system was capable of such feats of compassion, but that would require the majority of politicians to be as clever as cavemen. We’re not hopeful on those odds.

The first step is admitting you have a crying baby. The second step is … a step

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

Crying baby.

Crying baby who?

Crying baby who … umm … doesn’t have a punchline. Let’s try this again.

A priest, a rabbi, and a crying baby walk into a bar and … nope, that’s not going to work.

Why did the crying baby cross the road? Ugh, never mind.

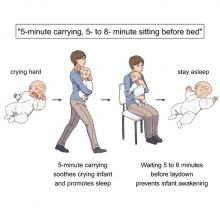

Clearly, crying babies are no laughing matter. What crying babies need is science. And the latest innovation – it’s fresh from a study conducted at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science in Saitama, Japan – in the science of crying babies is … walking. Researchers observed 21 unhappy infants and compared their responses to four strategies: being held by their walking mothers, held by their sitting mothers, lying in a motionless crib, or lying in a rocking cot.

The best strategy is for the mother – the experiment only involved mothers, but the results should apply to any caregiver – to pick up the crying baby, walk around for 5 minutes, sit for another 5-8 minutes, and then put the infant back to bed, the researchers said in a written statement.

The walking strategy, however, isn’t perfect. “Walking for 5 minutes promoted sleep, but only for crying infants. Surprisingly, this effect was absent when babies were already calm beforehand,” lead author Kumi O. Kuroda, MD, PhD, explained in a separate statement from the center.

It also doesn’t work on adults. We could not get a crying LOTME writer to fall asleep no matter how long his mother carried him around the office.

New way to detect Parkinson’s has already passed the sniff test

We humans aren’t generally known for our superpowers, but a woman from Scotland may just be the Smelling Superhero. Not only was she able to literally smell Parkinson’s disease (PD) on her husband 12 years before his diagnosis; she is also the reason that scientists have found a new way to test for PD.

Joy Milne, a retired nurse, told the BBC that her husband “had this musty rather unpleasant smell especially round his shoulders and the back of his neck and his skin had definitely changed.” She put two and two together after he had been diagnosed with PD and she came in contact with others with the same scent at a support group.

Researchers at the University of Manchester, working with Ms. Milne, have now created a skin test that uses mass spectroscopy to analyze a sample of the patient’s sebum in just 3 minutes and is 95% accurate. They tested 79 people with Parkinson’s and 71 without using this method and found “specific compounds unique to PD sebum samples when compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, we have identified two classes of lipids, namely, triacylglycerides and diglycerides, as components of human sebum that are significantly differentially expressed in PD,” they said in JACS Au.

This test could be available to general physicians within 2 years, which would provide new opportunities to the people who are waiting in line for neurologic consults. Ms. Milne’s husband passed away in 2015, but her courageous help and amazing nasal abilities may help millions down the line.

The power of flirting

It’s a common office stereotype: Women flirt with the boss to get ahead in the workplace, while men in power sexually harass women in subordinate positions. Nobody ever suspects the guys in the cubicles. A recent study takes a different look and paints a different picture.

The investigators conducted multiple online and lab experiments in how social sexual identity drives behavior in a workplace setting in relation to job placement. They found that it was most often men in lower-power positions who are insecure about their roles who initiate social sexual behavior, even though they know it’s offensive. Why? Power.

They randomly paired over 200 undergraduate students in a male/female fashion, placed them in subordinate and boss-like roles, and asked them to choose from a series of social sexual questions they wanted to ask their teammate. Male participants who were placed in subordinate positions to a female boss chose social sexual questions more often than did male bosses, female subordinates, and female bosses.

So what does this say about the threat of workplace harassment? The researchers found that men and women differ in their strategy for flirtation. For men, it’s a way to gain more power. But problems arise when they rationalize their behavior with a character trait like being a “big flirt.”

“When we take on that identity, it leads to certain behavioral patterns that reinforce the identity. And then, people use that identity as an excuse,” lead author Laura Kray of the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement from the school.

The researchers make a point to note that the study isn’t about whether flirting is good or bad, nor are they suggesting that people in powerful positions don’t sexually harass underlings. It’s meant to provide insight to improve corporate sexual harassment training. A comment or conversation held in jest could potentially be a warning sign for future behavior.

Monkey see, monkey do (advanced medical procedures)

We don’t tend to think too kindly of our prehistoric ancestors. We throw around the word “caveman” – hardly a term of endearment – and depictions of Paleolithic humans rarely flatter their subjects. In many ways, though, our conceptions are correct. Humans of the Stone Age lived short, often brutish lives, but civilization had to start somewhere, and our prehistoric ancestors were often far more capable than we give them credit for.

Case in point is a recent discovery from an archaeological dig in Borneo: A young adult who lived 31,000 years ago was discovered with the lower third of their left leg amputated. Save the clever retort about the person’s untimely death, because this individual did not die from the surgery. The amputation occurred when the individual was a child and the subject lived for several years after the operation.

Amputation is usually unnecessary given our current level of medical technology, but it’s actually quite an advanced procedure, and this example predates the previous first case of amputation by nearly 25,000 years. Not only did the surgeon need to cut at an appropriate place, they needed to understand blood loss, the risk of infection, and the need to preserve skin in order to seal the wound back up. That’s quite a lot for our Paleolithic doctor to know, and it’s even more impressive considering the, shall we say, limited tools they would have had available to perform the operation.

Rocks. They cut off the leg with a rock. And it worked.

This discovery also gives insight into the amputee’s society. Someone knew that amputation was the right move for this person, indicating that it had been done before. In addition, the individual would not have been able to spring back into action hunting mammoths right away, they would require care for the rest of their lives. And clearly the community provided, given the individual’s continued life post operation and their burial in a place of honor.

If only the American health care system was capable of such feats of compassion, but that would require the majority of politicians to be as clever as cavemen. We’re not hopeful on those odds.

The first step is admitting you have a crying baby. The second step is … a step

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

Crying baby.

Crying baby who?

Crying baby who … umm … doesn’t have a punchline. Let’s try this again.

A priest, a rabbi, and a crying baby walk into a bar and … nope, that’s not going to work.

Why did the crying baby cross the road? Ugh, never mind.

Clearly, crying babies are no laughing matter. What crying babies need is science. And the latest innovation – it’s fresh from a study conducted at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science in Saitama, Japan – in the science of crying babies is … walking. Researchers observed 21 unhappy infants and compared their responses to four strategies: being held by their walking mothers, held by their sitting mothers, lying in a motionless crib, or lying in a rocking cot.

The best strategy is for the mother – the experiment only involved mothers, but the results should apply to any caregiver – to pick up the crying baby, walk around for 5 minutes, sit for another 5-8 minutes, and then put the infant back to bed, the researchers said in a written statement.

The walking strategy, however, isn’t perfect. “Walking for 5 minutes promoted sleep, but only for crying infants. Surprisingly, this effect was absent when babies were already calm beforehand,” lead author Kumi O. Kuroda, MD, PhD, explained in a separate statement from the center.

It also doesn’t work on adults. We could not get a crying LOTME writer to fall asleep no matter how long his mother carried him around the office.

New way to detect Parkinson’s has already passed the sniff test

We humans aren’t generally known for our superpowers, but a woman from Scotland may just be the Smelling Superhero. Not only was she able to literally smell Parkinson’s disease (PD) on her husband 12 years before his diagnosis; she is also the reason that scientists have found a new way to test for PD.

Joy Milne, a retired nurse, told the BBC that her husband “had this musty rather unpleasant smell especially round his shoulders and the back of his neck and his skin had definitely changed.” She put two and two together after he had been diagnosed with PD and she came in contact with others with the same scent at a support group.

Researchers at the University of Manchester, working with Ms. Milne, have now created a skin test that uses mass spectroscopy to analyze a sample of the patient’s sebum in just 3 minutes and is 95% accurate. They tested 79 people with Parkinson’s and 71 without using this method and found “specific compounds unique to PD sebum samples when compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, we have identified two classes of lipids, namely, triacylglycerides and diglycerides, as components of human sebum that are significantly differentially expressed in PD,” they said in JACS Au.

This test could be available to general physicians within 2 years, which would provide new opportunities to the people who are waiting in line for neurologic consults. Ms. Milne’s husband passed away in 2015, but her courageous help and amazing nasal abilities may help millions down the line.

The power of flirting

It’s a common office stereotype: Women flirt with the boss to get ahead in the workplace, while men in power sexually harass women in subordinate positions. Nobody ever suspects the guys in the cubicles. A recent study takes a different look and paints a different picture.

The investigators conducted multiple online and lab experiments in how social sexual identity drives behavior in a workplace setting in relation to job placement. They found that it was most often men in lower-power positions who are insecure about their roles who initiate social sexual behavior, even though they know it’s offensive. Why? Power.

They randomly paired over 200 undergraduate students in a male/female fashion, placed them in subordinate and boss-like roles, and asked them to choose from a series of social sexual questions they wanted to ask their teammate. Male participants who were placed in subordinate positions to a female boss chose social sexual questions more often than did male bosses, female subordinates, and female bosses.

So what does this say about the threat of workplace harassment? The researchers found that men and women differ in their strategy for flirtation. For men, it’s a way to gain more power. But problems arise when they rationalize their behavior with a character trait like being a “big flirt.”

“When we take on that identity, it leads to certain behavioral patterns that reinforce the identity. And then, people use that identity as an excuse,” lead author Laura Kray of the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement from the school.

The researchers make a point to note that the study isn’t about whether flirting is good or bad, nor are they suggesting that people in powerful positions don’t sexually harass underlings. It’s meant to provide insight to improve corporate sexual harassment training. A comment or conversation held in jest could potentially be a warning sign for future behavior.

Monkey see, monkey do (advanced medical procedures)

We don’t tend to think too kindly of our prehistoric ancestors. We throw around the word “caveman” – hardly a term of endearment – and depictions of Paleolithic humans rarely flatter their subjects. In many ways, though, our conceptions are correct. Humans of the Stone Age lived short, often brutish lives, but civilization had to start somewhere, and our prehistoric ancestors were often far more capable than we give them credit for.

Case in point is a recent discovery from an archaeological dig in Borneo: A young adult who lived 31,000 years ago was discovered with the lower third of their left leg amputated. Save the clever retort about the person’s untimely death, because this individual did not die from the surgery. The amputation occurred when the individual was a child and the subject lived for several years after the operation.

Amputation is usually unnecessary given our current level of medical technology, but it’s actually quite an advanced procedure, and this example predates the previous first case of amputation by nearly 25,000 years. Not only did the surgeon need to cut at an appropriate place, they needed to understand blood loss, the risk of infection, and the need to preserve skin in order to seal the wound back up. That’s quite a lot for our Paleolithic doctor to know, and it’s even more impressive considering the, shall we say, limited tools they would have had available to perform the operation.

Rocks. They cut off the leg with a rock. And it worked.

This discovery also gives insight into the amputee’s society. Someone knew that amputation was the right move for this person, indicating that it had been done before. In addition, the individual would not have been able to spring back into action hunting mammoths right away, they would require care for the rest of their lives. And clearly the community provided, given the individual’s continued life post operation and their burial in a place of honor.

If only the American health care system was capable of such feats of compassion, but that would require the majority of politicians to be as clever as cavemen. We’re not hopeful on those odds.

The first step is admitting you have a crying baby. The second step is … a step

Knock, knock.

Who’s there?

Crying baby.

Crying baby who?

Crying baby who … umm … doesn’t have a punchline. Let’s try this again.

A priest, a rabbi, and a crying baby walk into a bar and … nope, that’s not going to work.

Why did the crying baby cross the road? Ugh, never mind.

Clearly, crying babies are no laughing matter. What crying babies need is science. And the latest innovation – it’s fresh from a study conducted at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science in Saitama, Japan – in the science of crying babies is … walking. Researchers observed 21 unhappy infants and compared their responses to four strategies: being held by their walking mothers, held by their sitting mothers, lying in a motionless crib, or lying in a rocking cot.

The best strategy is for the mother – the experiment only involved mothers, but the results should apply to any caregiver – to pick up the crying baby, walk around for 5 minutes, sit for another 5-8 minutes, and then put the infant back to bed, the researchers said in a written statement.

The walking strategy, however, isn’t perfect. “Walking for 5 minutes promoted sleep, but only for crying infants. Surprisingly, this effect was absent when babies were already calm beforehand,” lead author Kumi O. Kuroda, MD, PhD, explained in a separate statement from the center.

It also doesn’t work on adults. We could not get a crying LOTME writer to fall asleep no matter how long his mother carried him around the office.

New way to detect Parkinson’s has already passed the sniff test

We humans aren’t generally known for our superpowers, but a woman from Scotland may just be the Smelling Superhero. Not only was she able to literally smell Parkinson’s disease (PD) on her husband 12 years before his diagnosis; she is also the reason that scientists have found a new way to test for PD.

Joy Milne, a retired nurse, told the BBC that her husband “had this musty rather unpleasant smell especially round his shoulders and the back of his neck and his skin had definitely changed.” She put two and two together after he had been diagnosed with PD and she came in contact with others with the same scent at a support group.

Researchers at the University of Manchester, working with Ms. Milne, have now created a skin test that uses mass spectroscopy to analyze a sample of the patient’s sebum in just 3 minutes and is 95% accurate. They tested 79 people with Parkinson’s and 71 without using this method and found “specific compounds unique to PD sebum samples when compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, we have identified two classes of lipids, namely, triacylglycerides and diglycerides, as components of human sebum that are significantly differentially expressed in PD,” they said in JACS Au.

This test could be available to general physicians within 2 years, which would provide new opportunities to the people who are waiting in line for neurologic consults. Ms. Milne’s husband passed away in 2015, but her courageous help and amazing nasal abilities may help millions down the line.

The power of flirting

It’s a common office stereotype: Women flirt with the boss to get ahead in the workplace, while men in power sexually harass women in subordinate positions. Nobody ever suspects the guys in the cubicles. A recent study takes a different look and paints a different picture.

The investigators conducted multiple online and lab experiments in how social sexual identity drives behavior in a workplace setting in relation to job placement. They found that it was most often men in lower-power positions who are insecure about their roles who initiate social sexual behavior, even though they know it’s offensive. Why? Power.

They randomly paired over 200 undergraduate students in a male/female fashion, placed them in subordinate and boss-like roles, and asked them to choose from a series of social sexual questions they wanted to ask their teammate. Male participants who were placed in subordinate positions to a female boss chose social sexual questions more often than did male bosses, female subordinates, and female bosses.

So what does this say about the threat of workplace harassment? The researchers found that men and women differ in their strategy for flirtation. For men, it’s a way to gain more power. But problems arise when they rationalize their behavior with a character trait like being a “big flirt.”

“When we take on that identity, it leads to certain behavioral patterns that reinforce the identity. And then, people use that identity as an excuse,” lead author Laura Kray of the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement from the school.

The researchers make a point to note that the study isn’t about whether flirting is good or bad, nor are they suggesting that people in powerful positions don’t sexually harass underlings. It’s meant to provide insight to improve corporate sexual harassment training. A comment or conversation held in jest could potentially be a warning sign for future behavior.

In NSCLC, not all EGFR mutations are the same

In non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), . However, there is a range of different EGFR mutations, and different mutation combinations can lead to different tumor characteristics that might in turn affect response to therapy.

A new real-world analysis of 159 NSCLC patients found that a combination of a mutation of the TP53 tumor suppressor gene and the EGFR Ex20 mutation is associated with worse disease outcomes, compared to patients with the EGFR Ex20 mutation alone. But the news wasn’t all bad. The same group of patients also responded better to ICB (immune checkpoint blockade) therapy than did the broader population of EGFR Ex20 patients.

The EGFR Ex20 mutation occurs in about 4% of NSCLC cases, while TP53 is quite common: The new study found a frequency of 43.9%. “We first have to mention that the findings regarding TP53 do not reach statistical significance; however, the trend is very strong, and results might be hampered due to small sample sizes. We think it is [appropriate] to exhaust more treatment options for these patients, especially targeted approaches with newer drugs that specifically target exon 20 insertions, as these drugs were not applied in our cohort,” Anna Kron, Dr. rer. medic., said in an email exchange. Dr. Kron presented the results at a poster session in Paris at the ESMO Congress. She is a researcher at University Hospital of Cologne, Germany.

The ImmunoTarget study, published in 2019, examined over 500 NSCLC patients with a range of driver mutations including EGFR and found that they responded poorly to ICIs in comparison to KRAS mutations.

But Dr. Kron’s group was not convinced. “Ex20 mutations differ clinically from other tyrosine kinase mutations in EGFR. We set out this study to rechallenge the paradigm of impaired benefit from ICI in EGFR-mutated patients, as we consider these mutations not interchangeable with other EGFR mutations,” Dr. Kron said.

“We would postulate that in EGFR Exon 20 mutations, ICI and specific inhibitors should be part of the therapeutic course. In patients with co-occurring TP53 mutations, treatment escalation could be considered,” Dr. Kron said.

The study included 159 patients with advanced NSCLC with the EGFR exon 20 insertion, who were treated between 2014 and 2020 at German hospitals. Among the patients, 37.7% were female; mean age at diagnosis was 65.87 years; 50.3% had a smoking history and 38.4% did not (data were unavailable for the rest); and 9.4% of tumors were stage I, 4.4% stage II, 8.2% stage IIIA, 3.8% stage IIIB, and 74.2% stage IV.

Over a follow-up of 4.1 years, there was a trend toward longer survival among patients with TP53 wild type (OS, 20 versus 12 months; P = .092). Sixty-six patients who received ICI therapy had better OS compared with those who did not (22 versus 10 months; P = .018). Among patients with co-occurring TP53 mutations, receipt of ICI therapy was associated with longer OS (16 versus 8 months; P = .048). There was a trend toward patients with TP53 wild type treated with ICI faring better than those who didn’t receive ICI (27.0 months versus 11.0 months; P = .109).

The researchers are continuing to study patients with EGFR Ex20 to better understand the role of TP53 and ICI therapy in these patients.

The study received no funding. Dr. Kron has no relevant financial disclosures.

In non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), . However, there is a range of different EGFR mutations, and different mutation combinations can lead to different tumor characteristics that might in turn affect response to therapy.

A new real-world analysis of 159 NSCLC patients found that a combination of a mutation of the TP53 tumor suppressor gene and the EGFR Ex20 mutation is associated with worse disease outcomes, compared to patients with the EGFR Ex20 mutation alone. But the news wasn’t all bad. The same group of patients also responded better to ICB (immune checkpoint blockade) therapy than did the broader population of EGFR Ex20 patients.

The EGFR Ex20 mutation occurs in about 4% of NSCLC cases, while TP53 is quite common: The new study found a frequency of 43.9%. “We first have to mention that the findings regarding TP53 do not reach statistical significance; however, the trend is very strong, and results might be hampered due to small sample sizes. We think it is [appropriate] to exhaust more treatment options for these patients, especially targeted approaches with newer drugs that specifically target exon 20 insertions, as these drugs were not applied in our cohort,” Anna Kron, Dr. rer. medic., said in an email exchange. Dr. Kron presented the results at a poster session in Paris at the ESMO Congress. She is a researcher at University Hospital of Cologne, Germany.

The ImmunoTarget study, published in 2019, examined over 500 NSCLC patients with a range of driver mutations including EGFR and found that they responded poorly to ICIs in comparison to KRAS mutations.

But Dr. Kron’s group was not convinced. “Ex20 mutations differ clinically from other tyrosine kinase mutations in EGFR. We set out this study to rechallenge the paradigm of impaired benefit from ICI in EGFR-mutated patients, as we consider these mutations not interchangeable with other EGFR mutations,” Dr. Kron said.

“We would postulate that in EGFR Exon 20 mutations, ICI and specific inhibitors should be part of the therapeutic course. In patients with co-occurring TP53 mutations, treatment escalation could be considered,” Dr. Kron said.

The study included 159 patients with advanced NSCLC with the EGFR exon 20 insertion, who were treated between 2014 and 2020 at German hospitals. Among the patients, 37.7% were female; mean age at diagnosis was 65.87 years; 50.3% had a smoking history and 38.4% did not (data were unavailable for the rest); and 9.4% of tumors were stage I, 4.4% stage II, 8.2% stage IIIA, 3.8% stage IIIB, and 74.2% stage IV.

Over a follow-up of 4.1 years, there was a trend toward longer survival among patients with TP53 wild type (OS, 20 versus 12 months; P = .092). Sixty-six patients who received ICI therapy had better OS compared with those who did not (22 versus 10 months; P = .018). Among patients with co-occurring TP53 mutations, receipt of ICI therapy was associated with longer OS (16 versus 8 months; P = .048). There was a trend toward patients with TP53 wild type treated with ICI faring better than those who didn’t receive ICI (27.0 months versus 11.0 months; P = .109).

The researchers are continuing to study patients with EGFR Ex20 to better understand the role of TP53 and ICI therapy in these patients.

The study received no funding. Dr. Kron has no relevant financial disclosures.

In non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), . However, there is a range of different EGFR mutations, and different mutation combinations can lead to different tumor characteristics that might in turn affect response to therapy.

A new real-world analysis of 159 NSCLC patients found that a combination of a mutation of the TP53 tumor suppressor gene and the EGFR Ex20 mutation is associated with worse disease outcomes, compared to patients with the EGFR Ex20 mutation alone. But the news wasn’t all bad. The same group of patients also responded better to ICB (immune checkpoint blockade) therapy than did the broader population of EGFR Ex20 patients.

The EGFR Ex20 mutation occurs in about 4% of NSCLC cases, while TP53 is quite common: The new study found a frequency of 43.9%. “We first have to mention that the findings regarding TP53 do not reach statistical significance; however, the trend is very strong, and results might be hampered due to small sample sizes. We think it is [appropriate] to exhaust more treatment options for these patients, especially targeted approaches with newer drugs that specifically target exon 20 insertions, as these drugs were not applied in our cohort,” Anna Kron, Dr. rer. medic., said in an email exchange. Dr. Kron presented the results at a poster session in Paris at the ESMO Congress. She is a researcher at University Hospital of Cologne, Germany.

The ImmunoTarget study, published in 2019, examined over 500 NSCLC patients with a range of driver mutations including EGFR and found that they responded poorly to ICIs in comparison to KRAS mutations.

But Dr. Kron’s group was not convinced. “Ex20 mutations differ clinically from other tyrosine kinase mutations in EGFR. We set out this study to rechallenge the paradigm of impaired benefit from ICI in EGFR-mutated patients, as we consider these mutations not interchangeable with other EGFR mutations,” Dr. Kron said.

“We would postulate that in EGFR Exon 20 mutations, ICI and specific inhibitors should be part of the therapeutic course. In patients with co-occurring TP53 mutations, treatment escalation could be considered,” Dr. Kron said.

The study included 159 patients with advanced NSCLC with the EGFR exon 20 insertion, who were treated between 2014 and 2020 at German hospitals. Among the patients, 37.7% were female; mean age at diagnosis was 65.87 years; 50.3% had a smoking history and 38.4% did not (data were unavailable for the rest); and 9.4% of tumors were stage I, 4.4% stage II, 8.2% stage IIIA, 3.8% stage IIIB, and 74.2% stage IV.

Over a follow-up of 4.1 years, there was a trend toward longer survival among patients with TP53 wild type (OS, 20 versus 12 months; P = .092). Sixty-six patients who received ICI therapy had better OS compared with those who did not (22 versus 10 months; P = .018). Among patients with co-occurring TP53 mutations, receipt of ICI therapy was associated with longer OS (16 versus 8 months; P = .048). There was a trend toward patients with TP53 wild type treated with ICI faring better than those who didn’t receive ICI (27.0 months versus 11.0 months; P = .109).

The researchers are continuing to study patients with EGFR Ex20 to better understand the role of TP53 and ICI therapy in these patients.

The study received no funding. Dr. Kron has no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ESMO CONGRESS 2022

In early NSCLC, comorbidities linked to survival

Cardiometabolic and respiratory comorbidities are associated with worse survival in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and new research suggests a potential mechanism.

Prior studies had shown mixed results when it came to these comorbidities and survival, according to study coauthor author Geoffrey Liu, MD, who is an epidemiology researcher at the University of Toronto Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. The new work represents data from multiple continents, from various ethnicities and cultures.

“We found that comorbidities had much greater impact on earlier than later stages of lung cancer, consistent with this previous study,” said Dr. Liu in an email. The study was presented by Miguel Garcia-Pardo, who is a researcher at University of Toronto Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, during a poster session at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology.

“Deaths from [cardiometabolic] comorbidities were mainly from non–lung cancer competing causes, whereas the deaths from respiratory comorbidities were primarily driven by lung cancer specific survival, i.e., deaths from lung cancer itself. We conclude that Dr. Liu said.

Dr. Liu noted that controlling cardiometabolic risk factors like diabetes and hypertension is typically de-emphasized after diagnosis with early-stage lung cancer. The rationale is often that the lung cancer is a more acute concern than longer-term cardiometabolic risks. “The data from our analyses suggest a rethinking of this strategy. We need to pay more attention to controlling cardiovascular risk factors in early-stage lung cancer,” Dr. Liu said.

The findings also suggest that respiratory comorbidities should be managed more aggressively. That would allow more patients to undergo treatments like surgery and stereotactic radiation.

The Clinical Outcome Studies of the International Lung Cancer Consortium drew from two dozen studies conducted across five continents. It examined clinical, epidemiologic, genetic, and genomic factors and their potential influence on NSCLC outcomes. Cardiometabolic comorbidities included coronary artery disease, diabetes, vascular related diseases, and other heart diseases. Respiratory comorbidities included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma.

The analysis included 16,354 patients. Among patients with stage I NSCLC, there was an association between reduced overall survival (OS) and cardiometabolic comorbidity (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.17; P = .01) and respiratory comorbidity (aHR, 1.36; P < .001). For stage II/III patients, there was no significant association between OS and cardiometabolic comorbidities, but respiratory comorbidity was associated with worse OS (aHR, 1.15; P < .001). In stage 4, worse OS was associated with both cardiometabolic health comorbidity (aHR, 1.11; P = .03), but not respiratory comorbidity.

Among patients with stage IV NSCLC, there were no associations between overall survival or lung cancer–specific survival (LCSS) and respiratory or cardiometabolic risk factors. However, an examination of cause of death found a different pattern in patients with stage IB-IIIA disease: LCSS was worse among patients with respiratory comorbidities (aHR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.09-1.34). Among those with cardiovascular comorbidities, the risk of non-NSCLC mortality was higher (aHR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.15-1.63). The presence of respiratory comorbidity was associated with a reduced probability of undergoing surgical resection for both stage I (adjusted odds ratio, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.35-0.59) and stage II/III patients (aOR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.53-0.80).

There was an association between non-NSCLC mortality and cardiometabolic comorbidities in stage IA (aHR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.06-1.77) and in stages IB-IIIA (aHR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.03-1.71) NSCLC. There were also associations between NSCLC mortality and respiratory comorbidity among stage IA (aHR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.17-1.95) and stages IB-IIIA (aHR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.06-1.36) NSCLC. There were no associations between respiratory comorbidity and non-NSCLC mortality.

Respiratory comorbidity was associated with a lower chance of undergoing surgical resection in stage IA (aHR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.35-0.83) and stage IB-IIIA (aHR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.46-0.70) cancers. Cardiometabolic comorbidity was associated with a lower rate of surgical resection only in stage 1B-3A patients (aHR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56-0.96). Among those who underwent resection, stage IA patients were less likely to die of lung cancer (aHR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.28-0.52) but more likely to die of other causes (aHR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.07-1.78). Stage IB-IIIA patients who underwent resection were less likely to die of lung cancer (aHR, 0.37; 95%, 0.32-0.42), but there was no significant association with non–lung cancer mortality.

The study was funded by the Lusi Wong Family Fund and the Alan Brown Chair. Dr. Liu has no relevant financial disclosures.

Cardiometabolic and respiratory comorbidities are associated with worse survival in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and new research suggests a potential mechanism.

Prior studies had shown mixed results when it came to these comorbidities and survival, according to study coauthor author Geoffrey Liu, MD, who is an epidemiology researcher at the University of Toronto Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. The new work represents data from multiple continents, from various ethnicities and cultures.

“We found that comorbidities had much greater impact on earlier than later stages of lung cancer, consistent with this previous study,” said Dr. Liu in an email. The study was presented by Miguel Garcia-Pardo, who is a researcher at University of Toronto Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, during a poster session at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology.

“Deaths from [cardiometabolic] comorbidities were mainly from non–lung cancer competing causes, whereas the deaths from respiratory comorbidities were primarily driven by lung cancer specific survival, i.e., deaths from lung cancer itself. We conclude that Dr. Liu said.

Dr. Liu noted that controlling cardiometabolic risk factors like diabetes and hypertension is typically de-emphasized after diagnosis with early-stage lung cancer. The rationale is often that the lung cancer is a more acute concern than longer-term cardiometabolic risks. “The data from our analyses suggest a rethinking of this strategy. We need to pay more attention to controlling cardiovascular risk factors in early-stage lung cancer,” Dr. Liu said.

The findings also suggest that respiratory comorbidities should be managed more aggressively. That would allow more patients to undergo treatments like surgery and stereotactic radiation.

The Clinical Outcome Studies of the International Lung Cancer Consortium drew from two dozen studies conducted across five continents. It examined clinical, epidemiologic, genetic, and genomic factors and their potential influence on NSCLC outcomes. Cardiometabolic comorbidities included coronary artery disease, diabetes, vascular related diseases, and other heart diseases. Respiratory comorbidities included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma.

The analysis included 16,354 patients. Among patients with stage I NSCLC, there was an association between reduced overall survival (OS) and cardiometabolic comorbidity (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.17; P = .01) and respiratory comorbidity (aHR, 1.36; P < .001). For stage II/III patients, there was no significant association between OS and cardiometabolic comorbidities, but respiratory comorbidity was associated with worse OS (aHR, 1.15; P < .001). In stage 4, worse OS was associated with both cardiometabolic health comorbidity (aHR, 1.11; P = .03), but not respiratory comorbidity.

Among patients with stage IV NSCLC, there were no associations between overall survival or lung cancer–specific survival (LCSS) and respiratory or cardiometabolic risk factors. However, an examination of cause of death found a different pattern in patients with stage IB-IIIA disease: LCSS was worse among patients with respiratory comorbidities (aHR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.09-1.34). Among those with cardiovascular comorbidities, the risk of non-NSCLC mortality was higher (aHR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.15-1.63). The presence of respiratory comorbidity was associated with a reduced probability of undergoing surgical resection for both stage I (adjusted odds ratio, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.35-0.59) and stage II/III patients (aOR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.53-0.80).

There was an association between non-NSCLC mortality and cardiometabolic comorbidities in stage IA (aHR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.06-1.77) and in stages IB-IIIA (aHR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.03-1.71) NSCLC. There were also associations between NSCLC mortality and respiratory comorbidity among stage IA (aHR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.17-1.95) and stages IB-IIIA (aHR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.06-1.36) NSCLC. There were no associations between respiratory comorbidity and non-NSCLC mortality.

Respiratory comorbidity was associated with a lower chance of undergoing surgical resection in stage IA (aHR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.35-0.83) and stage IB-IIIA (aHR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.46-0.70) cancers. Cardiometabolic comorbidity was associated with a lower rate of surgical resection only in stage 1B-3A patients (aHR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56-0.96). Among those who underwent resection, stage IA patients were less likely to die of lung cancer (aHR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.28-0.52) but more likely to die of other causes (aHR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.07-1.78). Stage IB-IIIA patients who underwent resection were less likely to die of lung cancer (aHR, 0.37; 95%, 0.32-0.42), but there was no significant association with non–lung cancer mortality.

The study was funded by the Lusi Wong Family Fund and the Alan Brown Chair. Dr. Liu has no relevant financial disclosures.

Cardiometabolic and respiratory comorbidities are associated with worse survival in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and new research suggests a potential mechanism.

Prior studies had shown mixed results when it came to these comorbidities and survival, according to study coauthor author Geoffrey Liu, MD, who is an epidemiology researcher at the University of Toronto Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. The new work represents data from multiple continents, from various ethnicities and cultures.

“We found that comorbidities had much greater impact on earlier than later stages of lung cancer, consistent with this previous study,” said Dr. Liu in an email. The study was presented by Miguel Garcia-Pardo, who is a researcher at University of Toronto Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, during a poster session at the annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology.

“Deaths from [cardiometabolic] comorbidities were mainly from non–lung cancer competing causes, whereas the deaths from respiratory comorbidities were primarily driven by lung cancer specific survival, i.e., deaths from lung cancer itself. We conclude that Dr. Liu said.

Dr. Liu noted that controlling cardiometabolic risk factors like diabetes and hypertension is typically de-emphasized after diagnosis with early-stage lung cancer. The rationale is often that the lung cancer is a more acute concern than longer-term cardiometabolic risks. “The data from our analyses suggest a rethinking of this strategy. We need to pay more attention to controlling cardiovascular risk factors in early-stage lung cancer,” Dr. Liu said.

The findings also suggest that respiratory comorbidities should be managed more aggressively. That would allow more patients to undergo treatments like surgery and stereotactic radiation.

The Clinical Outcome Studies of the International Lung Cancer Consortium drew from two dozen studies conducted across five continents. It examined clinical, epidemiologic, genetic, and genomic factors and their potential influence on NSCLC outcomes. Cardiometabolic comorbidities included coronary artery disease, diabetes, vascular related diseases, and other heart diseases. Respiratory comorbidities included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma.

The analysis included 16,354 patients. Among patients with stage I NSCLC, there was an association between reduced overall survival (OS) and cardiometabolic comorbidity (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.17; P = .01) and respiratory comorbidity (aHR, 1.36; P < .001). For stage II/III patients, there was no significant association between OS and cardiometabolic comorbidities, but respiratory comorbidity was associated with worse OS (aHR, 1.15; P < .001). In stage 4, worse OS was associated with both cardiometabolic health comorbidity (aHR, 1.11; P = .03), but not respiratory comorbidity.

Among patients with stage IV NSCLC, there were no associations between overall survival or lung cancer–specific survival (LCSS) and respiratory or cardiometabolic risk factors. However, an examination of cause of death found a different pattern in patients with stage IB-IIIA disease: LCSS was worse among patients with respiratory comorbidities (aHR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.09-1.34). Among those with cardiovascular comorbidities, the risk of non-NSCLC mortality was higher (aHR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.15-1.63). The presence of respiratory comorbidity was associated with a reduced probability of undergoing surgical resection for both stage I (adjusted odds ratio, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.35-0.59) and stage II/III patients (aOR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.53-0.80).

There was an association between non-NSCLC mortality and cardiometabolic comorbidities in stage IA (aHR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.06-1.77) and in stages IB-IIIA (aHR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.03-1.71) NSCLC. There were also associations between NSCLC mortality and respiratory comorbidity among stage IA (aHR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.17-1.95) and stages IB-IIIA (aHR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.06-1.36) NSCLC. There were no associations between respiratory comorbidity and non-NSCLC mortality.

Respiratory comorbidity was associated with a lower chance of undergoing surgical resection in stage IA (aHR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.35-0.83) and stage IB-IIIA (aHR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.46-0.70) cancers. Cardiometabolic comorbidity was associated with a lower rate of surgical resection only in stage 1B-3A patients (aHR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56-0.96). Among those who underwent resection, stage IA patients were less likely to die of lung cancer (aHR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.28-0.52) but more likely to die of other causes (aHR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.07-1.78). Stage IB-IIIA patients who underwent resection were less likely to die of lung cancer (aHR, 0.37; 95%, 0.32-0.42), but there was no significant association with non–lung cancer mortality.

The study was funded by the Lusi Wong Family Fund and the Alan Brown Chair. Dr. Liu has no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ESMO CONGRESS 2022

‘Smoking gun–level’ evidence found linking air pollution with lung cancer

PARIS – Air pollution has been recognized as a risk factor for lung cancer for about 2 decades, and already present in normal lung cells to cause cancer.

Think of it as “smoking gun–level” evidence that may explain why many nonsmokers still develop non–small cell lung cancer, said Charles Swanton, PhD, from the Francis Crick Institute and Cancer Research UK Chief Clinician, London.

“What this work shows is that air pollution is directly causing lung cancer but through a slightly unexpected pathway,” he said at a briefing prior to his presentation of the data in a presidential symposium held earlier this month in Paris at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress 2022.

Importantly, he and his team also propose a mechanism for blocking the effects of air pollution with monoclonal antibodies directed against the inflammatory cytokine interleukein-1 beta.

Carcinogenesis explored

Lung cancer in never-smokers has a low mutational burden, with about 5- to 10-fold fewer mutations in a nonsmoker, compared with an ever smoker or current smoker, Dr. Swanton noted.

“The other thing to say about never-smokers is that they don’t have a clear environmental carcinogenic signature. So how do you square the circle? You’ve got the problem that you know that air pollution is associated with lung cancer – we don’t know if it causes it – but we also see that we’ve got no DNA mutations due to an environmental carcinogen,” he said during his symposium presentation.

The traditional model proposed to explain how carcinogens cause cancer holds that exposure to a carcinogen causes DNA mutations that lead to clonal expansion and tumor growth.

“But there are some major problems with this model,” Dr. Swanton said.

For example, normal skin contains a “patchwork of mutant clones,” but skin cancer is still uncommon, he said, and in studies in mice, 17 of 20 environmental carcinogens did not induce DNA mutations. He also noted that a common melanoma driver mutation, BRAF V600E, is not induced by exposure to a ultraviolet light.

“Any explanation for never-smoking lung cancer would have to fulfill three criteria: one, you have to explain why geographic variation exists; two, you have to prove causation; and three, you have to explain how cancers can be initiated without directly causing DNA mutations,” he said.

Normal lung tissues in nonsmoking adults can harbor pre-existing mutations, with the number of mutations increasing likely as a consequence of aging. In fact, more than 50% of normal lung biopsy tissues have been shown to harbor driver KRAS and/or EGFR mutations, Dr. Swanton said.

“In our research, these mutations alone only weakly potentiated cancer in laboratory models. However, when lung cells with these mutations were exposed to air pollutants, we saw more cancers and these occurred more quickly than when lung cells with these mutations were not exposed to pollutants, suggesting that air pollution promotes the initiation of lung cancer in cells harboring driver gene mutations. The next step is to discover why some lung cells with mutations become cancerous when exposed to pollutants while others don’t,” he said.

Geographical exposures

Looking at data on 447,932 participants in the UK Biobank, the investigators found that increasing exposure to ambient air particles smaller than 2.5 mcm (PM2.5) was significantly associated with seven cancer types, including lung cancer. They also saw an association between PM2.5 exposure levels and EGFR-mutated lung cancer incidence in the United Kingdom, South Korea, and Taiwan.

And crucially, as Dr. Swanton and associates showed in mouse models, exposure of lung cells bearing somatic EGFR and KRAS mutations to PM2.5 causes recruitment of macrophages that in turn secrete IL-1B, resulting in a transdifferentiation of EGFR-mutated cells into a cancer stem cell state, and tumor formation.

Importantly, pollution-induced tumor formation can be blocked by antibodies directed against IL-1B, Dr. Swanton said.

He pointed to a 2017 study in The Lancet suggesting that anti-inflammatory therapy with the anti–IL-1 antibody canakinumab (Ilaris) could reduce incident lung cancer and lung cancer deaths.

‘Elegant first demonstration’

“This is a very meaningful demonstration, from epidemiological data to preclinical models of the role of PM2.5 air pollutants in the promotion of lung cancer, and it provides us with very important insights into the mechanism through which nonsmokers can get lung cancer,” commented Suzette Delaloge, MD, from the cancer interception program at Institut Goustave Roussy in Villejuif, France, the invited discussant.

“But beyond that, it also has a great impact on our vision of carcinogenesis, with this very elegant first demonstration of the alternative nonmutagenic, carcinogenetic promotion hypothesis for fine particulate matter,” she said.

Questions still to be answered include whether PM2.5 pollutants could also be mutagenic, is the oncogenic pathway ubiquitous in tissue, which components of PM2.5 might drive the effect, how long of an exposure is required to promote lung cancer, and why and how persons without cancer develop specific driver mutations such as EGFR, she said.

“This research is intriguing and exciting as it means that we can ask whether, in the future, it will be possible to use lung scans to look for precancerous lesions in the lungs and try to reverse them with medicines such as interleukin-1B inhibitors,” said Tony Mok, MD, a lung cancer specialist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who was not involved in the study.

“We don’t yet know whether it will be possible to use highly sensitive EGFR profiling on blood or other samples to find nonsmokers who are predisposed to lung cancer and may benefit from lung scanning, so discussions are still very speculative,” he said in a statement.

The study was supported by Cancer Research UK, the Lung Cancer Research Foundations, Rosetrees Trust, the Mark Foundation for Cancer Research and the Ruth Strauss Foundation. Dr. Swanton disclosed grants/research support, honoraria, and stock ownership with multiple entities. Dr. Delaloge disclosed institutional financing and research funding from multiple companies. Dr. Mok disclosed stock ownership and honoraria with multiple companies.

PARIS – Air pollution has been recognized as a risk factor for lung cancer for about 2 decades, and already present in normal lung cells to cause cancer.

Think of it as “smoking gun–level” evidence that may explain why many nonsmokers still develop non–small cell lung cancer, said Charles Swanton, PhD, from the Francis Crick Institute and Cancer Research UK Chief Clinician, London.

“What this work shows is that air pollution is directly causing lung cancer but through a slightly unexpected pathway,” he said at a briefing prior to his presentation of the data in a presidential symposium held earlier this month in Paris at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress 2022.

Importantly, he and his team also propose a mechanism for blocking the effects of air pollution with monoclonal antibodies directed against the inflammatory cytokine interleukein-1 beta.

Carcinogenesis explored

Lung cancer in never-smokers has a low mutational burden, with about 5- to 10-fold fewer mutations in a nonsmoker, compared with an ever smoker or current smoker, Dr. Swanton noted.

“The other thing to say about never-smokers is that they don’t have a clear environmental carcinogenic signature. So how do you square the circle? You’ve got the problem that you know that air pollution is associated with lung cancer – we don’t know if it causes it – but we also see that we’ve got no DNA mutations due to an environmental carcinogen,” he said during his symposium presentation.

The traditional model proposed to explain how carcinogens cause cancer holds that exposure to a carcinogen causes DNA mutations that lead to clonal expansion and tumor growth.

“But there are some major problems with this model,” Dr. Swanton said.

For example, normal skin contains a “patchwork of mutant clones,” but skin cancer is still uncommon, he said, and in studies in mice, 17 of 20 environmental carcinogens did not induce DNA mutations. He also noted that a common melanoma driver mutation, BRAF V600E, is not induced by exposure to a ultraviolet light.

“Any explanation for never-smoking lung cancer would have to fulfill three criteria: one, you have to explain why geographic variation exists; two, you have to prove causation; and three, you have to explain how cancers can be initiated without directly causing DNA mutations,” he said.

Normal lung tissues in nonsmoking adults can harbor pre-existing mutations, with the number of mutations increasing likely as a consequence of aging. In fact, more than 50% of normal lung biopsy tissues have been shown to harbor driver KRAS and/or EGFR mutations, Dr. Swanton said.

“In our research, these mutations alone only weakly potentiated cancer in laboratory models. However, when lung cells with these mutations were exposed to air pollutants, we saw more cancers and these occurred more quickly than when lung cells with these mutations were not exposed to pollutants, suggesting that air pollution promotes the initiation of lung cancer in cells harboring driver gene mutations. The next step is to discover why some lung cells with mutations become cancerous when exposed to pollutants while others don’t,” he said.

Geographical exposures

Looking at data on 447,932 participants in the UK Biobank, the investigators found that increasing exposure to ambient air particles smaller than 2.5 mcm (PM2.5) was significantly associated with seven cancer types, including lung cancer. They also saw an association between PM2.5 exposure levels and EGFR-mutated lung cancer incidence in the United Kingdom, South Korea, and Taiwan.

And crucially, as Dr. Swanton and associates showed in mouse models, exposure of lung cells bearing somatic EGFR and KRAS mutations to PM2.5 causes recruitment of macrophages that in turn secrete IL-1B, resulting in a transdifferentiation of EGFR-mutated cells into a cancer stem cell state, and tumor formation.

Importantly, pollution-induced tumor formation can be blocked by antibodies directed against IL-1B, Dr. Swanton said.

He pointed to a 2017 study in The Lancet suggesting that anti-inflammatory therapy with the anti–IL-1 antibody canakinumab (Ilaris) could reduce incident lung cancer and lung cancer deaths.

‘Elegant first demonstration’

“This is a very meaningful demonstration, from epidemiological data to preclinical models of the role of PM2.5 air pollutants in the promotion of lung cancer, and it provides us with very important insights into the mechanism through which nonsmokers can get lung cancer,” commented Suzette Delaloge, MD, from the cancer interception program at Institut Goustave Roussy in Villejuif, France, the invited discussant.

“But beyond that, it also has a great impact on our vision of carcinogenesis, with this very elegant first demonstration of the alternative nonmutagenic, carcinogenetic promotion hypothesis for fine particulate matter,” she said.

Questions still to be answered include whether PM2.5 pollutants could also be mutagenic, is the oncogenic pathway ubiquitous in tissue, which components of PM2.5 might drive the effect, how long of an exposure is required to promote lung cancer, and why and how persons without cancer develop specific driver mutations such as EGFR, she said.

“This research is intriguing and exciting as it means that we can ask whether, in the future, it will be possible to use lung scans to look for precancerous lesions in the lungs and try to reverse them with medicines such as interleukin-1B inhibitors,” said Tony Mok, MD, a lung cancer specialist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who was not involved in the study.

“We don’t yet know whether it will be possible to use highly sensitive EGFR profiling on blood or other samples to find nonsmokers who are predisposed to lung cancer and may benefit from lung scanning, so discussions are still very speculative,” he said in a statement.

The study was supported by Cancer Research UK, the Lung Cancer Research Foundations, Rosetrees Trust, the Mark Foundation for Cancer Research and the Ruth Strauss Foundation. Dr. Swanton disclosed grants/research support, honoraria, and stock ownership with multiple entities. Dr. Delaloge disclosed institutional financing and research funding from multiple companies. Dr. Mok disclosed stock ownership and honoraria with multiple companies.

PARIS – Air pollution has been recognized as a risk factor for lung cancer for about 2 decades, and already present in normal lung cells to cause cancer.

Think of it as “smoking gun–level” evidence that may explain why many nonsmokers still develop non–small cell lung cancer, said Charles Swanton, PhD, from the Francis Crick Institute and Cancer Research UK Chief Clinician, London.

“What this work shows is that air pollution is directly causing lung cancer but through a slightly unexpected pathway,” he said at a briefing prior to his presentation of the data in a presidential symposium held earlier this month in Paris at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress 2022.

Importantly, he and his team also propose a mechanism for blocking the effects of air pollution with monoclonal antibodies directed against the inflammatory cytokine interleukein-1 beta.

Carcinogenesis explored

Lung cancer in never-smokers has a low mutational burden, with about 5- to 10-fold fewer mutations in a nonsmoker, compared with an ever smoker or current smoker, Dr. Swanton noted.

“The other thing to say about never-smokers is that they don’t have a clear environmental carcinogenic signature. So how do you square the circle? You’ve got the problem that you know that air pollution is associated with lung cancer – we don’t know if it causes it – but we also see that we’ve got no DNA mutations due to an environmental carcinogen,” he said during his symposium presentation.

The traditional model proposed to explain how carcinogens cause cancer holds that exposure to a carcinogen causes DNA mutations that lead to clonal expansion and tumor growth.

“But there are some major problems with this model,” Dr. Swanton said.

For example, normal skin contains a “patchwork of mutant clones,” but skin cancer is still uncommon, he said, and in studies in mice, 17 of 20 environmental carcinogens did not induce DNA mutations. He also noted that a common melanoma driver mutation, BRAF V600E, is not induced by exposure to a ultraviolet light.

“Any explanation for never-smoking lung cancer would have to fulfill three criteria: one, you have to explain why geographic variation exists; two, you have to prove causation; and three, you have to explain how cancers can be initiated without directly causing DNA mutations,” he said.

Normal lung tissues in nonsmoking adults can harbor pre-existing mutations, with the number of mutations increasing likely as a consequence of aging. In fact, more than 50% of normal lung biopsy tissues have been shown to harbor driver KRAS and/or EGFR mutations, Dr. Swanton said.

“In our research, these mutations alone only weakly potentiated cancer in laboratory models. However, when lung cells with these mutations were exposed to air pollutants, we saw more cancers and these occurred more quickly than when lung cells with these mutations were not exposed to pollutants, suggesting that air pollution promotes the initiation of lung cancer in cells harboring driver gene mutations. The next step is to discover why some lung cells with mutations become cancerous when exposed to pollutants while others don’t,” he said.

Geographical exposures

Looking at data on 447,932 participants in the UK Biobank, the investigators found that increasing exposure to ambient air particles smaller than 2.5 mcm (PM2.5) was significantly associated with seven cancer types, including lung cancer. They also saw an association between PM2.5 exposure levels and EGFR-mutated lung cancer incidence in the United Kingdom, South Korea, and Taiwan.

And crucially, as Dr. Swanton and associates showed in mouse models, exposure of lung cells bearing somatic EGFR and KRAS mutations to PM2.5 causes recruitment of macrophages that in turn secrete IL-1B, resulting in a transdifferentiation of EGFR-mutated cells into a cancer stem cell state, and tumor formation.

Importantly, pollution-induced tumor formation can be blocked by antibodies directed against IL-1B, Dr. Swanton said.

He pointed to a 2017 study in The Lancet suggesting that anti-inflammatory therapy with the anti–IL-1 antibody canakinumab (Ilaris) could reduce incident lung cancer and lung cancer deaths.

‘Elegant first demonstration’

“This is a very meaningful demonstration, from epidemiological data to preclinical models of the role of PM2.5 air pollutants in the promotion of lung cancer, and it provides us with very important insights into the mechanism through which nonsmokers can get lung cancer,” commented Suzette Delaloge, MD, from the cancer interception program at Institut Goustave Roussy in Villejuif, France, the invited discussant.

“But beyond that, it also has a great impact on our vision of carcinogenesis, with this very elegant first demonstration of the alternative nonmutagenic, carcinogenetic promotion hypothesis for fine particulate matter,” she said.

Questions still to be answered include whether PM2.5 pollutants could also be mutagenic, is the oncogenic pathway ubiquitous in tissue, which components of PM2.5 might drive the effect, how long of an exposure is required to promote lung cancer, and why and how persons without cancer develop specific driver mutations such as EGFR, she said.

“This research is intriguing and exciting as it means that we can ask whether, in the future, it will be possible to use lung scans to look for precancerous lesions in the lungs and try to reverse them with medicines such as interleukin-1B inhibitors,” said Tony Mok, MD, a lung cancer specialist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who was not involved in the study.

“We don’t yet know whether it will be possible to use highly sensitive EGFR profiling on blood or other samples to find nonsmokers who are predisposed to lung cancer and may benefit from lung scanning, so discussions are still very speculative,” he said in a statement.