User login

CCJM delivers practical clinical articles relevant to internists, cardiologists, endocrinologists, and other specialists, all written by known experts.

Copyright © 2019 Cleveland Clinic. All rights reserved. The information provided is for educational purposes only. Use of this website is subject to the disclaimer and privacy policy.

gambling

compulsive behaviors

ammunition

assault rifle

black jack

Boko Haram

bondage

child abuse

cocaine

Daech

drug paraphernalia

explosion

gun

human trafficking

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

slot machine

terrorism

terrorist

Texas hold 'em

UFC

substance abuse

abuseed

abuseer

abusees

abuseing

abusely

abuses

aeolus

aeolused

aeoluser

aeoluses

aeolusing

aeolusly

aeoluss

ahole

aholeed

aholeer

aholees

aholeing

aholely

aholes

alcohol

alcoholed

alcoholer

alcoholes

alcoholing

alcoholly

alcohols

allman

allmaned

allmaner

allmanes

allmaning

allmanly

allmans

alted

altes

alting

altly

alts

analed

analer

anales

analing

anally

analprobe

analprobeed

analprobeer

analprobees

analprobeing

analprobely

analprobes

anals

anilingus

anilingused

anilinguser

anilinguses

anilingusing

anilingusly

anilinguss

anus

anused

anuser

anuses

anusing

anusly

anuss

areola

areolaed

areolaer

areolaes

areolaing

areolaly

areolas

areole

areoleed

areoleer

areolees

areoleing

areolely

areoles

arian

arianed

arianer

arianes

arianing

arianly

arians

aryan

aryaned

aryaner

aryanes

aryaning

aryanly

aryans

asiaed

asiaer

asiaes

asiaing

asialy

asias

ass

ass hole

ass lick

ass licked

ass licker

ass lickes

ass licking

ass lickly

ass licks

assbang

assbanged

assbangeded

assbangeder

assbangedes

assbangeding

assbangedly

assbangeds

assbanger

assbanges

assbanging

assbangly

assbangs

assbangsed

assbangser

assbangses

assbangsing

assbangsly

assbangss

assed

asser

asses

assesed

asseser

asseses

assesing

assesly

assess

assfuck

assfucked

assfucker

assfuckered

assfuckerer

assfuckeres

assfuckering

assfuckerly

assfuckers

assfuckes

assfucking

assfuckly

assfucks

asshat

asshated

asshater

asshates

asshating

asshatly

asshats

assholeed

assholeer

assholees

assholeing

assholely

assholes

assholesed

assholeser

assholeses

assholesing

assholesly

assholess

assing

assly

assmaster

assmastered

assmasterer

assmasteres

assmastering

assmasterly

assmasters

assmunch

assmunched

assmuncher

assmunches

assmunching

assmunchly

assmunchs

asss

asswipe

asswipeed

asswipeer

asswipees

asswipeing

asswipely

asswipes

asswipesed

asswipeser

asswipeses

asswipesing

asswipesly

asswipess

azz

azzed

azzer

azzes

azzing

azzly

azzs

babeed

babeer

babees

babeing

babely

babes

babesed

babeser

babeses

babesing

babesly

babess

ballsac

ballsaced

ballsacer

ballsaces

ballsacing

ballsack

ballsacked

ballsacker

ballsackes

ballsacking

ballsackly

ballsacks

ballsacly

ballsacs

ballsed

ballser

ballses

ballsing

ballsly

ballss

barf

barfed

barfer

barfes

barfing

barfly

barfs

bastard

bastarded

bastarder

bastardes

bastarding

bastardly

bastards

bastardsed

bastardser

bastardses

bastardsing

bastardsly

bastardss

bawdy

bawdyed

bawdyer

bawdyes

bawdying

bawdyly

bawdys

beaner

beanered

beanerer

beaneres

beanering

beanerly

beaners

beardedclam

beardedclamed

beardedclamer

beardedclames

beardedclaming

beardedclamly

beardedclams

beastiality

beastialityed

beastialityer

beastialityes

beastialitying

beastialityly

beastialitys

beatch

beatched

beatcher

beatches

beatching

beatchly

beatchs

beater

beatered

beaterer

beateres

beatering

beaterly

beaters

beered

beerer

beeres

beering

beerly

beeyotch

beeyotched

beeyotcher

beeyotches

beeyotching

beeyotchly

beeyotchs

beotch

beotched

beotcher

beotches

beotching

beotchly

beotchs

biatch

biatched

biatcher

biatches

biatching

biatchly

biatchs

big tits

big titsed

big titser

big titses

big titsing

big titsly

big titss

bigtits

bigtitsed

bigtitser

bigtitses

bigtitsing

bigtitsly

bigtitss

bimbo

bimboed

bimboer

bimboes

bimboing

bimboly

bimbos

bisexualed

bisexualer

bisexuales

bisexualing

bisexually

bisexuals

bitch

bitched

bitcheded

bitcheder

bitchedes

bitcheding

bitchedly

bitcheds

bitcher

bitches

bitchesed

bitcheser

bitcheses

bitchesing

bitchesly

bitchess

bitching

bitchly

bitchs

bitchy

bitchyed

bitchyer

bitchyes

bitchying

bitchyly

bitchys

bleached

bleacher

bleaches

bleaching

bleachly

bleachs

blow job

blow jobed

blow jober

blow jobes

blow jobing

blow jobly

blow jobs

blowed

blower

blowes

blowing

blowjob

blowjobed

blowjober

blowjobes

blowjobing

blowjobly

blowjobs

blowjobsed

blowjobser

blowjobses

blowjobsing

blowjobsly

blowjobss

blowly

blows

boink

boinked

boinker

boinkes

boinking

boinkly

boinks

bollock

bollocked

bollocker

bollockes

bollocking

bollockly

bollocks

bollocksed

bollockser

bollockses

bollocksing

bollocksly

bollockss

bollok

bolloked

bolloker

bollokes

bolloking

bollokly

bolloks

boner

bonered

bonerer

boneres

bonering

bonerly

boners

bonersed

bonerser

bonerses

bonersing

bonersly

bonerss

bong

bonged

bonger

bonges

bonging

bongly

bongs

boob

boobed

boober

boobes

boobies

boobiesed

boobieser

boobieses

boobiesing

boobiesly

boobiess

boobing

boobly

boobs

boobsed

boobser

boobses

boobsing

boobsly

boobss

booby

boobyed

boobyer

boobyes

boobying

boobyly

boobys

booger

boogered

boogerer

boogeres

boogering

boogerly

boogers

bookie

bookieed

bookieer

bookiees

bookieing

bookiely

bookies

bootee

booteeed

booteeer

booteees

booteeing

booteely

bootees

bootie

bootieed

bootieer

bootiees

bootieing

bootiely

booties

booty

bootyed

bootyer

bootyes

bootying

bootyly

bootys

boozeed

boozeer

boozees

boozeing

boozely

boozer

boozered

boozerer

boozeres

boozering

boozerly

boozers

boozes

boozy

boozyed

boozyer

boozyes

boozying

boozyly

boozys

bosomed

bosomer

bosomes

bosoming

bosomly

bosoms

bosomy

bosomyed

bosomyer

bosomyes

bosomying

bosomyly

bosomys

bugger

buggered

buggerer

buggeres

buggering

buggerly

buggers

bukkake

bukkakeed

bukkakeer

bukkakees

bukkakeing

bukkakely

bukkakes

bull shit

bull shited

bull shiter

bull shites

bull shiting

bull shitly

bull shits

bullshit

bullshited

bullshiter

bullshites

bullshiting

bullshitly

bullshits

bullshitsed

bullshitser

bullshitses

bullshitsing

bullshitsly

bullshitss

bullshitted

bullshitteded

bullshitteder

bullshittedes

bullshitteding

bullshittedly

bullshitteds

bullturds

bullturdsed

bullturdser

bullturdses

bullturdsing

bullturdsly

bullturdss

bung

bunged

bunger

bunges

bunging

bungly

bungs

busty

bustyed

bustyer

bustyes

bustying

bustyly

bustys

butt

butt fuck

butt fucked

butt fucker

butt fuckes

butt fucking

butt fuckly

butt fucks

butted

buttes

buttfuck

buttfucked

buttfucker

buttfuckered

buttfuckerer

buttfuckeres

buttfuckering

buttfuckerly

buttfuckers

buttfuckes

buttfucking

buttfuckly

buttfucks

butting

buttly

buttplug

buttpluged

buttpluger

buttpluges

buttpluging

buttplugly

buttplugs

butts

caca

cacaed

cacaer

cacaes

cacaing

cacaly

cacas

cahone

cahoneed

cahoneer

cahonees

cahoneing

cahonely

cahones

cameltoe

cameltoeed

cameltoeer

cameltoees

cameltoeing

cameltoely

cameltoes

carpetmuncher

carpetmunchered

carpetmuncherer

carpetmuncheres

carpetmunchering

carpetmuncherly

carpetmunchers

cawk

cawked

cawker

cawkes

cawking

cawkly

cawks

chinc

chinced

chincer

chinces

chincing

chincly

chincs

chincsed

chincser

chincses

chincsing

chincsly

chincss

chink

chinked

chinker

chinkes

chinking

chinkly

chinks

chode

chodeed

chodeer

chodees

chodeing

chodely

chodes

chodesed

chodeser

chodeses

chodesing

chodesly

chodess

clit

clited

cliter

clites

cliting

clitly

clitoris

clitorised

clitoriser

clitorises

clitorising

clitorisly

clitoriss

clitorus

clitorused

clitoruser

clitoruses

clitorusing

clitorusly

clitoruss

clits

clitsed

clitser

clitses

clitsing

clitsly

clitss

clitty

clittyed

clittyer

clittyes

clittying

clittyly

clittys

cocain

cocaine

cocained

cocaineed

cocaineer

cocainees

cocaineing

cocainely

cocainer

cocaines

cocaining

cocainly

cocains

cock

cock sucker

cock suckered

cock suckerer

cock suckeres

cock suckering

cock suckerly

cock suckers

cockblock

cockblocked

cockblocker

cockblockes

cockblocking

cockblockly

cockblocks

cocked

cocker

cockes

cockholster

cockholstered

cockholsterer

cockholsteres

cockholstering

cockholsterly

cockholsters

cocking

cockknocker

cockknockered

cockknockerer

cockknockeres

cockknockering

cockknockerly

cockknockers

cockly

cocks

cocksed

cockser

cockses

cocksing

cocksly

cocksmoker

cocksmokered

cocksmokerer

cocksmokeres

cocksmokering

cocksmokerly

cocksmokers

cockss

cocksucker

cocksuckered

cocksuckerer

cocksuckeres

cocksuckering

cocksuckerly

cocksuckers

coital

coitaled

coitaler

coitales

coitaling

coitally

coitals

commie

commieed

commieer

commiees

commieing

commiely

commies

condomed

condomer

condomes

condoming

condomly

condoms

coon

cooned

cooner

coones

cooning

coonly

coons

coonsed

coonser

coonses

coonsing

coonsly

coonss

corksucker

corksuckered

corksuckerer

corksuckeres

corksuckering

corksuckerly

corksuckers

cracked

crackwhore

crackwhoreed

crackwhoreer

crackwhorees

crackwhoreing

crackwhorely

crackwhores

crap

craped

craper

crapes

craping

craply

crappy

crappyed

crappyer

crappyes

crappying

crappyly

crappys

cum

cumed

cumer

cumes

cuming

cumly

cummin

cummined

cumminer

cummines

cumming

cumminged

cumminger

cumminges

cumminging

cummingly

cummings

cummining

cumminly

cummins

cums

cumshot

cumshoted

cumshoter

cumshotes

cumshoting

cumshotly

cumshots

cumshotsed

cumshotser

cumshotses

cumshotsing

cumshotsly

cumshotss

cumslut

cumsluted

cumsluter

cumslutes

cumsluting

cumslutly

cumsluts

cumstain

cumstained

cumstainer

cumstaines

cumstaining

cumstainly

cumstains

cunilingus

cunilingused

cunilinguser

cunilinguses

cunilingusing

cunilingusly

cunilinguss

cunnilingus

cunnilingused

cunnilinguser

cunnilinguses

cunnilingusing

cunnilingusly

cunnilinguss

cunny

cunnyed

cunnyer

cunnyes

cunnying

cunnyly

cunnys

cunt

cunted

cunter

cuntes

cuntface

cuntfaceed

cuntfaceer

cuntfacees

cuntfaceing

cuntfacely

cuntfaces

cunthunter

cunthuntered

cunthunterer

cunthunteres

cunthuntering

cunthunterly

cunthunters

cunting

cuntlick

cuntlicked

cuntlicker

cuntlickered

cuntlickerer

cuntlickeres

cuntlickering

cuntlickerly

cuntlickers

cuntlickes

cuntlicking

cuntlickly

cuntlicks

cuntly

cunts

cuntsed

cuntser

cuntses

cuntsing

cuntsly

cuntss

dago

dagoed

dagoer

dagoes

dagoing

dagoly

dagos

dagosed

dagoser

dagoses

dagosing

dagosly

dagoss

dammit

dammited

dammiter

dammites

dammiting

dammitly

dammits

damn

damned

damneded

damneder

damnedes

damneding

damnedly

damneds

damner

damnes

damning

damnit

damnited

damniter

damnites

damniting

damnitly

damnits

damnly

damns

dick

dickbag

dickbaged

dickbager

dickbages

dickbaging

dickbagly

dickbags

dickdipper

dickdippered

dickdipperer

dickdipperes

dickdippering

dickdipperly

dickdippers

dicked

dicker

dickes

dickface

dickfaceed

dickfaceer

dickfacees

dickfaceing

dickfacely

dickfaces

dickflipper

dickflippered

dickflipperer

dickflipperes

dickflippering

dickflipperly

dickflippers

dickhead

dickheaded

dickheader

dickheades

dickheading

dickheadly

dickheads

dickheadsed

dickheadser

dickheadses

dickheadsing

dickheadsly

dickheadss

dicking

dickish

dickished

dickisher

dickishes

dickishing

dickishly

dickishs

dickly

dickripper

dickrippered

dickripperer

dickripperes

dickrippering

dickripperly

dickrippers

dicks

dicksipper

dicksippered

dicksipperer

dicksipperes

dicksippering

dicksipperly

dicksippers

dickweed

dickweeded

dickweeder

dickweedes

dickweeding

dickweedly

dickweeds

dickwhipper

dickwhippered

dickwhipperer

dickwhipperes

dickwhippering

dickwhipperly

dickwhippers

dickzipper

dickzippered

dickzipperer

dickzipperes

dickzippering

dickzipperly

dickzippers

diddle

diddleed

diddleer

diddlees

diddleing

diddlely

diddles

dike

dikeed

dikeer

dikees

dikeing

dikely

dikes

dildo

dildoed

dildoer

dildoes

dildoing

dildoly

dildos

dildosed

dildoser

dildoses

dildosing

dildosly

dildoss

diligaf

diligafed

diligafer

diligafes

diligafing

diligafly

diligafs

dillweed

dillweeded

dillweeder

dillweedes

dillweeding

dillweedly

dillweeds

dimwit

dimwited

dimwiter

dimwites

dimwiting

dimwitly

dimwits

dingle

dingleed

dingleer

dinglees

dingleing

dinglely

dingles

dipship

dipshiped

dipshiper

dipshipes

dipshiping

dipshiply

dipships

dizzyed

dizzyer

dizzyes

dizzying

dizzyly

dizzys

doggiestyleed

doggiestyleer

doggiestylees

doggiestyleing

doggiestylely

doggiestyles

doggystyleed

doggystyleer

doggystylees

doggystyleing

doggystylely

doggystyles

dong

donged

donger

donges

donging

dongly

dongs

doofus

doofused

doofuser

doofuses

doofusing

doofusly

doofuss

doosh

dooshed

doosher

dooshes

dooshing

dooshly

dooshs

dopeyed

dopeyer

dopeyes

dopeying

dopeyly

dopeys

douchebag

douchebaged

douchebager

douchebages

douchebaging

douchebagly

douchebags

douchebagsed

douchebagser

douchebagses

douchebagsing

douchebagsly

douchebagss

doucheed

doucheer

douchees

doucheing

douchely

douches

douchey

doucheyed

doucheyer

doucheyes

doucheying

doucheyly

doucheys

drunk

drunked

drunker

drunkes

drunking

drunkly

drunks

dumass

dumassed

dumasser

dumasses

dumassing

dumassly

dumasss

dumbass

dumbassed

dumbasser

dumbasses

dumbassesed

dumbasseser

dumbasseses

dumbassesing

dumbassesly

dumbassess

dumbassing

dumbassly

dumbasss

dummy

dummyed

dummyer

dummyes

dummying

dummyly

dummys

dyke

dykeed

dykeer

dykees

dykeing

dykely

dykes

dykesed

dykeser

dykeses

dykesing

dykesly

dykess

erotic

eroticed

eroticer

erotices

eroticing

eroticly

erotics

extacy

extacyed

extacyer

extacyes

extacying

extacyly

extacys

extasy

extasyed

extasyer

extasyes

extasying

extasyly

extasys

fack

facked

facker

fackes

facking

fackly

facks

fag

faged

fager

fages

fagg

fagged

faggeded

faggeder

faggedes

faggeding

faggedly

faggeds

fagger

fagges

fagging

faggit

faggited

faggiter

faggites

faggiting

faggitly

faggits

faggly

faggot

faggoted

faggoter

faggotes

faggoting

faggotly

faggots

faggs

faging

fagly

fagot

fagoted

fagoter

fagotes

fagoting

fagotly

fagots

fags

fagsed

fagser

fagses

fagsing

fagsly

fagss

faig

faiged

faiger

faiges

faiging

faigly

faigs

faigt

faigted

faigter

faigtes

faigting

faigtly

faigts

fannybandit

fannybandited

fannybanditer

fannybandites

fannybanditing

fannybanditly

fannybandits

farted

farter

fartes

farting

fartknocker

fartknockered

fartknockerer

fartknockeres

fartknockering

fartknockerly

fartknockers

fartly

farts

felch

felched

felcher

felchered

felcherer

felcheres

felchering

felcherly

felchers

felches

felching

felchinged

felchinger

felchinges

felchinging

felchingly

felchings

felchly

felchs

fellate

fellateed

fellateer

fellatees

fellateing

fellately

fellates

fellatio

fellatioed

fellatioer

fellatioes

fellatioing

fellatioly

fellatios

feltch

feltched

feltcher

feltchered

feltcherer

feltcheres

feltchering

feltcherly

feltchers

feltches

feltching

feltchly

feltchs

feom

feomed

feomer

feomes

feoming

feomly

feoms

fisted

fisteded

fisteder

fistedes

fisteding

fistedly

fisteds

fisting

fistinged

fistinger

fistinges

fistinging

fistingly

fistings

fisty

fistyed

fistyer

fistyes

fistying

fistyly

fistys

floozy

floozyed

floozyer

floozyes

floozying

floozyly

floozys

foad

foaded

foader

foades

foading

foadly

foads

fondleed

fondleer

fondlees

fondleing

fondlely

fondles

foobar

foobared

foobarer

foobares

foobaring

foobarly

foobars

freex

freexed

freexer

freexes

freexing

freexly

freexs

frigg

frigga

friggaed

friggaer

friggaes

friggaing

friggaly

friggas

frigged

frigger

frigges

frigging

friggly

friggs

fubar

fubared

fubarer

fubares

fubaring

fubarly

fubars

fuck

fuckass

fuckassed

fuckasser

fuckasses

fuckassing

fuckassly

fuckasss

fucked

fuckeded

fuckeder

fuckedes

fuckeding

fuckedly

fuckeds

fucker

fuckered

fuckerer

fuckeres

fuckering

fuckerly

fuckers

fuckes

fuckface

fuckfaceed

fuckfaceer

fuckfacees

fuckfaceing

fuckfacely

fuckfaces

fuckin

fuckined

fuckiner

fuckines

fucking

fuckinged

fuckinger

fuckinges

fuckinging

fuckingly

fuckings

fuckining

fuckinly

fuckins

fuckly

fucknugget

fucknuggeted

fucknuggeter

fucknuggetes

fucknuggeting

fucknuggetly

fucknuggets

fucknut

fucknuted

fucknuter

fucknutes

fucknuting

fucknutly

fucknuts

fuckoff

fuckoffed

fuckoffer

fuckoffes

fuckoffing

fuckoffly

fuckoffs

fucks

fucksed

fuckser

fuckses

fucksing

fucksly

fuckss

fucktard

fucktarded

fucktarder

fucktardes

fucktarding

fucktardly

fucktards

fuckup

fuckuped

fuckuper

fuckupes

fuckuping

fuckuply

fuckups

fuckwad

fuckwaded

fuckwader

fuckwades

fuckwading

fuckwadly

fuckwads

fuckwit

fuckwited

fuckwiter

fuckwites

fuckwiting

fuckwitly

fuckwits

fudgepacker

fudgepackered

fudgepackerer

fudgepackeres

fudgepackering

fudgepackerly

fudgepackers

fuk

fuked

fuker

fukes

fuking

fukly

fuks

fvck

fvcked

fvcker

fvckes

fvcking

fvckly

fvcks

fxck

fxcked

fxcker

fxckes

fxcking

fxckly

fxcks

gae

gaeed

gaeer

gaees

gaeing

gaely

gaes

gai

gaied

gaier

gaies

gaiing

gaily

gais

ganja

ganjaed

ganjaer

ganjaes

ganjaing

ganjaly

ganjas

gayed

gayer

gayes

gaying

gayly

gays

gaysed

gayser

gayses

gaysing

gaysly

gayss

gey

geyed

geyer

geyes

geying

geyly

geys

gfc

gfced

gfcer

gfces

gfcing

gfcly

gfcs

gfy

gfyed

gfyer

gfyes

gfying

gfyly

gfys

ghay

ghayed

ghayer

ghayes

ghaying

ghayly

ghays

ghey

gheyed

gheyer

gheyes

gheying

gheyly

gheys

gigolo

gigoloed

gigoloer

gigoloes

gigoloing

gigololy

gigolos

goatse

goatseed

goatseer

goatsees

goatseing

goatsely

goatses

godamn

godamned

godamner

godamnes

godamning

godamnit

godamnited

godamniter

godamnites

godamniting

godamnitly

godamnits

godamnly

godamns

goddam

goddamed

goddamer

goddames

goddaming

goddamly

goddammit

goddammited

goddammiter

goddammites

goddammiting

goddammitly

goddammits

goddamn

goddamned

goddamner

goddamnes

goddamning

goddamnly

goddamns

goddams

goldenshower

goldenshowered

goldenshowerer

goldenshoweres

goldenshowering

goldenshowerly

goldenshowers

gonad

gonaded

gonader

gonades

gonading

gonadly

gonads

gonadsed

gonadser

gonadses

gonadsing

gonadsly

gonadss

gook

gooked

gooker

gookes

gooking

gookly

gooks

gooksed

gookser

gookses

gooksing

gooksly

gookss

gringo

gringoed

gringoer

gringoes

gringoing

gringoly

gringos

gspot

gspoted

gspoter

gspotes

gspoting

gspotly

gspots

gtfo

gtfoed

gtfoer

gtfoes

gtfoing

gtfoly

gtfos

guido

guidoed

guidoer

guidoes

guidoing

guidoly

guidos

handjob

handjobed

handjober

handjobes

handjobing

handjobly

handjobs

hard on

hard oned

hard oner

hard ones

hard oning

hard only

hard ons

hardknight

hardknighted

hardknighter

hardknightes

hardknighting

hardknightly

hardknights

hebe

hebeed

hebeer

hebees

hebeing

hebely

hebes

heeb

heebed

heeber

heebes

heebing

heebly

heebs

hell

helled

heller

helles

helling

hellly

hells

hemp

hemped

hemper

hempes

hemping

hemply

hemps

heroined

heroiner

heroines

heroining

heroinly

heroins

herp

herped

herper

herpes

herpesed

herpeser

herpeses

herpesing

herpesly

herpess

herping

herply

herps

herpy

herpyed

herpyer

herpyes

herpying

herpyly

herpys

hitler

hitlered

hitlerer

hitleres

hitlering

hitlerly

hitlers

hived

hiver

hives

hiving

hivly

hivs

hobag

hobaged

hobager

hobages

hobaging

hobagly

hobags

homey

homeyed

homeyer

homeyes

homeying

homeyly

homeys

homo

homoed

homoer

homoes

homoey

homoeyed

homoeyer

homoeyes

homoeying

homoeyly

homoeys

homoing

homoly

homos

honky

honkyed

honkyer

honkyes

honkying

honkyly

honkys

hooch

hooched

hoocher

hooches

hooching

hoochly

hoochs

hookah

hookahed

hookaher

hookahes

hookahing

hookahly

hookahs

hooker

hookered

hookerer

hookeres

hookering

hookerly

hookers

hoor

hoored

hoorer

hoores

hooring

hoorly

hoors

hootch

hootched

hootcher

hootches

hootching

hootchly

hootchs

hooter

hootered

hooterer

hooteres

hootering

hooterly

hooters

hootersed

hooterser

hooterses

hootersing

hootersly

hooterss

horny

hornyed

hornyer

hornyes

hornying

hornyly

hornys

houstoned

houstoner

houstones

houstoning

houstonly

houstons

hump

humped

humpeded

humpeder

humpedes

humpeding

humpedly

humpeds

humper

humpes

humping

humpinged

humpinger

humpinges

humpinging

humpingly

humpings

humply

humps

husbanded

husbander

husbandes

husbanding

husbandly

husbands

hussy

hussyed

hussyer

hussyes

hussying

hussyly

hussys

hymened

hymener

hymenes

hymening

hymenly

hymens

inbred

inbreded

inbreder

inbredes

inbreding

inbredly

inbreds

incest

incested

incester

incestes

incesting

incestly

incests

injun

injuned

injuner

injunes

injuning

injunly

injuns

jackass

jackassed

jackasser

jackasses

jackassing

jackassly

jackasss

jackhole

jackholeed

jackholeer

jackholees

jackholeing

jackholely

jackholes

jackoff

jackoffed

jackoffer

jackoffes

jackoffing

jackoffly

jackoffs

jap

japed

japer

japes

japing

japly

japs

japsed

japser

japses

japsing

japsly

japss

jerkoff

jerkoffed

jerkoffer

jerkoffes

jerkoffing

jerkoffly

jerkoffs

jerks

jism

jismed

jismer

jismes

jisming

jismly

jisms

jiz

jized

jizer

jizes

jizing

jizly

jizm

jizmed

jizmer

jizmes

jizming

jizmly

jizms

jizs

jizz

jizzed

jizzeded

jizzeder

jizzedes

jizzeding

jizzedly

jizzeds

jizzer

jizzes

jizzing

jizzly

jizzs

junkie

junkieed

junkieer

junkiees

junkieing

junkiely

junkies

junky

junkyed

junkyer

junkyes

junkying

junkyly

junkys

kike

kikeed

kikeer

kikees

kikeing

kikely

kikes

kikesed

kikeser

kikeses

kikesing

kikesly

kikess

killed

killer

killes

killing

killly

kills

kinky

kinkyed

kinkyer

kinkyes

kinkying

kinkyly

kinkys

kkk

kkked

kkker

kkkes

kkking

kkkly

kkks

klan

klaned

klaner

klanes

klaning

klanly

klans

knobend

knobended

knobender

knobendes

knobending

knobendly

knobends

kooch

kooched

koocher

kooches

koochesed

koocheser

koocheses

koochesing

koochesly

koochess

kooching

koochly

koochs

kootch

kootched

kootcher

kootches

kootching

kootchly

kootchs

kraut

krauted

krauter

krautes

krauting

krautly

krauts

kyke

kykeed

kykeer

kykees

kykeing

kykely

kykes

lech

leched

lecher

leches

leching

lechly

lechs

leper

lepered

leperer

leperes

lepering

leperly

lepers

lesbiansed

lesbianser

lesbianses

lesbiansing

lesbiansly

lesbianss

lesbo

lesboed

lesboer

lesboes

lesboing

lesboly

lesbos

lesbosed

lesboser

lesboses

lesbosing

lesbosly

lesboss

lez

lezbianed

lezbianer

lezbianes

lezbianing

lezbianly

lezbians

lezbiansed

lezbianser

lezbianses

lezbiansing

lezbiansly

lezbianss

lezbo

lezboed

lezboer

lezboes

lezboing

lezboly

lezbos

lezbosed

lezboser

lezboses

lezbosing

lezbosly

lezboss

lezed

lezer

lezes

lezing

lezly

lezs

lezzie

lezzieed

lezzieer

lezziees

lezzieing

lezziely

lezzies

lezziesed

lezzieser

lezzieses

lezziesing

lezziesly

lezziess

lezzy

lezzyed

lezzyer

lezzyes

lezzying

lezzyly

lezzys

lmaoed

lmaoer

lmaoes

lmaoing

lmaoly

lmaos

lmfao

lmfaoed

lmfaoer

lmfaoes

lmfaoing

lmfaoly

lmfaos

loined

loiner

loines

loining

loinly

loins

loinsed

loinser

loinses

loinsing

loinsly

loinss

lubeed

lubeer

lubees

lubeing

lubely

lubes

lusty

lustyed

lustyer

lustyes

lustying

lustyly

lustys

massa

massaed

massaer

massaes

massaing

massaly

massas

masterbate

masterbateed

masterbateer

masterbatees

masterbateing

masterbately

masterbates

masterbating

masterbatinged

masterbatinger

masterbatinges

masterbatinging

masterbatingly

masterbatings

masterbation

masterbationed

masterbationer

masterbationes

masterbationing

masterbationly

masterbations

masturbate

masturbateed

masturbateer

masturbatees

masturbateing

masturbately

masturbates

masturbating

masturbatinged

masturbatinger

masturbatinges

masturbatinging

masturbatingly

masturbatings

masturbation

masturbationed

masturbationer

masturbationes

masturbationing

masturbationly

masturbations

methed

mether

methes

mething

methly

meths

militaryed

militaryer

militaryes

militarying

militaryly

militarys

mofo

mofoed

mofoer

mofoes

mofoing

mofoly

mofos

molest

molested

molester

molestes

molesting

molestly

molests

moolie

moolieed

moolieer

mooliees

moolieing

mooliely

moolies

moron

moroned

moroner

morones

moroning

moronly

morons

motherfucka

motherfuckaed

motherfuckaer

motherfuckaes

motherfuckaing

motherfuckaly

motherfuckas

motherfucker

motherfuckered

motherfuckerer

motherfuckeres

motherfuckering

motherfuckerly

motherfuckers

motherfucking

motherfuckinged

motherfuckinger

motherfuckinges

motherfuckinging

motherfuckingly

motherfuckings

mtherfucker

mtherfuckered

mtherfuckerer

mtherfuckeres

mtherfuckering

mtherfuckerly

mtherfuckers

mthrfucker

mthrfuckered

mthrfuckerer

mthrfuckeres

mthrfuckering

mthrfuckerly

mthrfuckers

mthrfucking

mthrfuckinged

mthrfuckinger

mthrfuckinges

mthrfuckinging

mthrfuckingly

mthrfuckings

muff

muffdiver

muffdivered

muffdiverer

muffdiveres

muffdivering

muffdiverly

muffdivers

muffed

muffer

muffes

muffing

muffly

muffs

murdered

murderer

murderes

murdering

murderly

murders

muthafuckaz

muthafuckazed

muthafuckazer

muthafuckazes

muthafuckazing

muthafuckazly

muthafuckazs

muthafucker

muthafuckered

muthafuckerer

muthafuckeres

muthafuckering

muthafuckerly

muthafuckers

mutherfucker

mutherfuckered

mutherfuckerer

mutherfuckeres

mutherfuckering

mutherfuckerly

mutherfuckers

mutherfucking

mutherfuckinged

mutherfuckinger

mutherfuckinges

mutherfuckinging

mutherfuckingly

mutherfuckings

muthrfucking

muthrfuckinged

muthrfuckinger

muthrfuckinges

muthrfuckinging

muthrfuckingly

muthrfuckings

nad

naded

nader

nades

nading

nadly

nads

nadsed

nadser

nadses

nadsing

nadsly

nadss

nakeded

nakeder

nakedes

nakeding

nakedly

nakeds

napalm

napalmed

napalmer

napalmes

napalming

napalmly

napalms

nappy

nappyed

nappyer

nappyes

nappying

nappyly

nappys

nazi

nazied

nazier

nazies

naziing

nazily

nazis

nazism

nazismed

nazismer

nazismes

nazisming

nazismly

nazisms

negro

negroed

negroer

negroes

negroing

negroly

negros

nigga

niggaed

niggaer

niggaes

niggah

niggahed

niggaher

niggahes

niggahing

niggahly

niggahs

niggaing

niggaly

niggas

niggased

niggaser

niggases

niggasing

niggasly

niggass

niggaz

niggazed

niggazer

niggazes

niggazing

niggazly

niggazs

nigger

niggered

niggerer

niggeres

niggering

niggerly

niggers

niggersed

niggerser

niggerses

niggersing

niggersly

niggerss

niggle

niggleed

niggleer

nigglees

niggleing

nigglely

niggles

niglet

nigleted

nigleter

nigletes

nigleting

nigletly

niglets

nimrod

nimroded

nimroder

nimrodes

nimroding

nimrodly

nimrods

ninny

ninnyed

ninnyer

ninnyes

ninnying

ninnyly

ninnys

nooky

nookyed

nookyer

nookyes

nookying

nookyly

nookys

nuccitelli

nuccitellied

nuccitellier

nuccitellies

nuccitelliing

nuccitellily

nuccitellis

nympho

nymphoed

nymphoer

nymphoes

nymphoing

nympholy

nymphos

opium

opiumed

opiumer

opiumes

opiuming

opiumly

opiums

orgies

orgiesed

orgieser

orgieses

orgiesing

orgiesly

orgiess

orgy

orgyed

orgyer

orgyes

orgying

orgyly

orgys

paddy

paddyed

paddyer

paddyes

paddying

paddyly

paddys

paki

pakied

pakier

pakies

pakiing

pakily

pakis

pantie

pantieed

pantieer

pantiees

pantieing

pantiely

panties

pantiesed

pantieser

pantieses

pantiesing

pantiesly

pantiess

panty

pantyed

pantyer

pantyes

pantying

pantyly

pantys

pastie

pastieed

pastieer

pastiees

pastieing

pastiely

pasties

pasty

pastyed

pastyer

pastyes

pastying

pastyly

pastys

pecker

peckered

peckerer

peckeres

peckering

peckerly

peckers

pedo

pedoed

pedoer

pedoes

pedoing

pedoly

pedophile

pedophileed

pedophileer

pedophilees

pedophileing

pedophilely

pedophiles

pedophilia

pedophiliac

pedophiliaced

pedophiliacer

pedophiliaces

pedophiliacing

pedophiliacly

pedophiliacs

pedophiliaed

pedophiliaer

pedophiliaes

pedophiliaing

pedophilialy

pedophilias

pedos

penial

penialed

penialer

peniales

penialing

penially

penials

penile

penileed

penileer

penilees

penileing

penilely

peniles

penis

penised

peniser

penises

penising

penisly

peniss

perversion

perversioned

perversioner

perversiones

perversioning

perversionly

perversions

peyote

peyoteed

peyoteer

peyotees

peyoteing

peyotely

peyotes

phuck

phucked

phucker

phuckes

phucking

phuckly

phucks

pillowbiter

pillowbitered

pillowbiterer

pillowbiteres

pillowbitering

pillowbiterly

pillowbiters

pimp

pimped

pimper

pimpes

pimping

pimply

pimps

pinko

pinkoed

pinkoer

pinkoes

pinkoing

pinkoly

pinkos

pissed

pisseded

pisseder

pissedes

pisseding

pissedly

pisseds

pisser

pisses

pissing

pissly

pissoff

pissoffed

pissoffer

pissoffes

pissoffing

pissoffly

pissoffs

pisss

polack

polacked

polacker

polackes

polacking

polackly

polacks

pollock

pollocked

pollocker

pollockes

pollocking

pollockly

pollocks

poon

pooned

pooner

poones

pooning

poonly

poons

poontang

poontanged

poontanger

poontanges

poontanging

poontangly

poontangs

porn

porned

porner

pornes

porning

pornly

porno

pornoed

pornoer

pornoes

pornography

pornographyed

pornographyer

pornographyes

pornographying

pornographyly

pornographys

pornoing

pornoly

pornos

porns

prick

pricked

pricker

prickes

pricking

prickly

pricks

prig

priged

priger

priges

priging

prigly

prigs

prostitute

prostituteed

prostituteer

prostitutees

prostituteing

prostitutely

prostitutes

prude

prudeed

prudeer

prudees

prudeing

prudely

prudes

punkass

punkassed

punkasser

punkasses

punkassing

punkassly

punkasss

punky

punkyed

punkyer

punkyes

punkying

punkyly

punkys

puss

pussed

pusser

pusses

pussies

pussiesed

pussieser

pussieses

pussiesing

pussiesly

pussiess

pussing

pussly

pusss

pussy

pussyed

pussyer

pussyes

pussying

pussyly

pussypounder

pussypoundered

pussypounderer

pussypounderes

pussypoundering

pussypounderly

pussypounders

pussys

puto

putoed

putoer

putoes

putoing

putoly

putos

queaf

queafed

queafer

queafes

queafing

queafly

queafs

queef

queefed

queefer

queefes

queefing

queefly

queefs

queer

queered

queerer

queeres

queering

queerly

queero

queeroed

queeroer

queeroes

queeroing

queeroly

queeros

queers

queersed

queerser

queerses

queersing

queersly

queerss

quicky

quickyed

quickyer

quickyes

quickying

quickyly

quickys

quim

quimed

quimer

quimes

quiming

quimly

quims

racy

racyed

racyer

racyes

racying

racyly

racys

rape

raped

rapeded

rapeder

rapedes

rapeding

rapedly

rapeds

rapeed

rapeer

rapees

rapeing

rapely

raper

rapered

raperer

raperes

rapering

raperly

rapers

rapes

rapist

rapisted

rapister

rapistes

rapisting

rapistly

rapists

raunch

raunched

rauncher

raunches

raunching

raunchly

raunchs

rectus

rectused

rectuser

rectuses

rectusing

rectusly

rectuss

reefer

reefered

reeferer

reeferes

reefering

reeferly

reefers

reetard

reetarded

reetarder

reetardes

reetarding

reetardly

reetards

reich

reiched

reicher

reiches

reiching

reichly

reichs

retard

retarded

retardeded

retardeder

retardedes

retardeding

retardedly

retardeds

retarder

retardes

retarding

retardly

retards

rimjob

rimjobed

rimjober

rimjobes

rimjobing

rimjobly

rimjobs

ritard

ritarded

ritarder

ritardes

ritarding

ritardly

ritards

rtard

rtarded

rtarder

rtardes

rtarding

rtardly

rtards

rum

rumed

rumer

rumes

ruming

rumly

rump

rumped

rumper

rumpes

rumping

rumply

rumprammer

rumprammered

rumprammerer

rumprammeres

rumprammering

rumprammerly

rumprammers

rumps

rums

ruski

ruskied

ruskier

ruskies

ruskiing

ruskily

ruskis

sadism

sadismed

sadismer

sadismes

sadisming

sadismly

sadisms

sadist

sadisted

sadister

sadistes

sadisting

sadistly

sadists

scag

scaged

scager

scages

scaging

scagly

scags

scantily

scantilyed

scantilyer

scantilyes

scantilying

scantilyly

scantilys

schlong

schlonged

schlonger

schlonges

schlonging

schlongly

schlongs

scrog

scroged

scroger

scroges

scroging

scrogly

scrogs

scrot

scrote

scroted

scroteed

scroteer

scrotees

scroteing

scrotely

scroter

scrotes

scroting

scrotly

scrots

scrotum

scrotumed

scrotumer

scrotumes

scrotuming

scrotumly

scrotums

scrud

scruded

scruder

scrudes

scruding

scrudly

scruds

scum

scumed

scumer

scumes

scuming

scumly

scums

seaman

seamaned

seamaner

seamanes

seamaning

seamanly

seamans

seamen

seamened

seamener

seamenes

seamening

seamenly

seamens

seduceed

seduceer

seducees

seduceing

seducely

seduces

semen

semened

semener

semenes

semening

semenly

semens

shamedame

shamedameed

shamedameer

shamedamees

shamedameing

shamedamely

shamedames

shit

shite

shiteater

shiteatered

shiteaterer

shiteateres

shiteatering

shiteaterly

shiteaters

shited

shiteed

shiteer

shitees

shiteing

shitely

shiter

shites

shitface

shitfaceed

shitfaceer

shitfacees

shitfaceing

shitfacely

shitfaces

shithead

shitheaded

shitheader

shitheades

shitheading

shitheadly

shitheads

shithole

shitholeed

shitholeer

shitholees

shitholeing

shitholely

shitholes

shithouse

shithouseed

shithouseer

shithousees

shithouseing

shithousely

shithouses

shiting

shitly

shits

shitsed

shitser

shitses

shitsing

shitsly

shitss

shitt

shitted

shitteded

shitteder

shittedes

shitteding

shittedly

shitteds

shitter

shittered

shitterer

shitteres

shittering

shitterly

shitters

shittes

shitting

shittly

shitts

shitty

shittyed

shittyer

shittyes

shittying

shittyly

shittys

shiz

shized

shizer

shizes

shizing

shizly

shizs

shooted

shooter

shootes

shooting

shootly

shoots

sissy

sissyed

sissyer

sissyes

sissying

sissyly

sissys

skag

skaged

skager

skages

skaging

skagly

skags

skank

skanked

skanker

skankes

skanking

skankly

skanks

slave

slaveed

slaveer

slavees

slaveing

slavely

slaves

sleaze

sleazeed

sleazeer

sleazees

sleazeing

sleazely

sleazes

sleazy

sleazyed

sleazyer

sleazyes

sleazying

sleazyly

sleazys

slut

slutdumper

slutdumpered

slutdumperer

slutdumperes

slutdumpering

slutdumperly

slutdumpers

sluted

sluter

slutes

sluting

slutkiss

slutkissed

slutkisser

slutkisses

slutkissing

slutkissly

slutkisss

slutly

sluts

slutsed

slutser

slutses

slutsing

slutsly

slutss

smegma

smegmaed

smegmaer

smegmaes

smegmaing

smegmaly

smegmas

smut

smuted

smuter

smutes

smuting

smutly

smuts

smutty

smuttyed

smuttyer

smuttyes

smuttying

smuttyly

smuttys

snatch

snatched

snatcher

snatches

snatching

snatchly

snatchs

sniper

snipered

sniperer

sniperes

snipering

sniperly

snipers

snort

snorted

snorter

snortes

snorting

snortly

snorts

snuff

snuffed

snuffer

snuffes

snuffing

snuffly

snuffs

sodom

sodomed

sodomer

sodomes

sodoming

sodomly

sodoms

spic

spiced

spicer

spices

spicing

spick

spicked

spicker

spickes

spicking

spickly

spicks

spicly

spics

spik

spoof

spoofed

spoofer

spoofes

spoofing

spoofly

spoofs

spooge

spoogeed

spoogeer

spoogees

spoogeing

spoogely

spooges

spunk

spunked

spunker

spunkes

spunking

spunkly

spunks

steamyed

steamyer

steamyes

steamying

steamyly

steamys

stfu

stfued

stfuer

stfues

stfuing

stfuly

stfus

stiffy

stiffyed

stiffyer

stiffyes

stiffying

stiffyly

stiffys

stoneded

stoneder

stonedes

stoneding

stonedly

stoneds

stupided

stupider

stupides

stupiding

stupidly

stupids

suckeded

suckeder

suckedes

suckeding

suckedly

suckeds

sucker

suckes

sucking

suckinged

suckinger

suckinges

suckinging

suckingly

suckings

suckly

sucks

sumofabiatch

sumofabiatched

sumofabiatcher

sumofabiatches

sumofabiatching

sumofabiatchly

sumofabiatchs

tard

tarded

tarder

tardes

tarding

tardly

tards

tawdry

tawdryed

tawdryer

tawdryes

tawdrying

tawdryly

tawdrys

teabagging

teabagginged

teabagginger

teabagginges

teabagginging

teabaggingly

teabaggings

terd

terded

terder

terdes

terding

terdly

terds

teste

testee

testeed

testeeed

testeeer

testeees

testeeing

testeely

testeer

testees

testeing

testely

testes

testesed

testeser

testeses

testesing

testesly

testess

testicle

testicleed

testicleer

testiclees

testicleing

testiclely

testicles

testis

testised

testiser

testises

testising

testisly

testiss

thrusted

thruster

thrustes

thrusting

thrustly

thrusts

thug

thuged

thuger

thuges

thuging

thugly

thugs

tinkle

tinkleed

tinkleer

tinklees

tinkleing

tinklely

tinkles

tit

tited

titer

tites

titfuck

titfucked

titfucker

titfuckes

titfucking

titfuckly

titfucks

titi

titied

titier

tities

titiing

titily

titing

titis

titly

tits

titsed

titser

titses

titsing

titsly

titss

tittiefucker

tittiefuckered

tittiefuckerer

tittiefuckeres

tittiefuckering

tittiefuckerly

tittiefuckers

titties

tittiesed

tittieser

tittieses

tittiesing

tittiesly

tittiess

titty

tittyed

tittyer

tittyes

tittyfuck

tittyfucked

tittyfucker

tittyfuckered

tittyfuckerer

tittyfuckeres

tittyfuckering

tittyfuckerly

tittyfuckers

tittyfuckes

tittyfucking

tittyfuckly

tittyfucks

tittying

tittyly

tittys

toke

tokeed

tokeer

tokees

tokeing

tokely

tokes

toots

tootsed

tootser

tootses

tootsing

tootsly

tootss

tramp

tramped

tramper

trampes

tramping

tramply

tramps

transsexualed

transsexualer

transsexuales

transsexualing

transsexually

transsexuals

trashy

trashyed

trashyer

trashyes

trashying

trashyly

trashys

tubgirl

tubgirled

tubgirler

tubgirles

tubgirling

tubgirlly

tubgirls

turd

turded

turder

turdes

turding

turdly

turds

tush

tushed

tusher

tushes

tushing

tushly

tushs

twat

twated

twater

twates

twating

twatly

twats

twatsed

twatser

twatses

twatsing

twatsly

twatss

undies

undiesed

undieser

undieses

undiesing

undiesly

undiess

unweded

unweder

unwedes

unweding

unwedly

unweds

uzi

uzied

uzier

uzies

uziing

uzily

uzis

vag

vaged

vager

vages

vaging

vagly

vags

valium

valiumed

valiumer

valiumes

valiuming

valiumly

valiums

venous

virgined

virginer

virgines

virgining

virginly

virgins

vixen

vixened

vixener

vixenes

vixening

vixenly

vixens

vodkaed

vodkaer

vodkaes

vodkaing

vodkaly

vodkas

voyeur

voyeured

voyeurer

voyeures

voyeuring

voyeurly

voyeurs

vulgar

vulgared

vulgarer

vulgares

vulgaring

vulgarly

vulgars

wang

wanged

wanger

wanges

wanging

wangly

wangs

wank

wanked

wanker

wankered

wankerer

wankeres

wankering

wankerly

wankers

wankes

wanking

wankly

wanks

wazoo

wazooed

wazooer

wazooes

wazooing

wazooly

wazoos

wedgie

wedgieed

wedgieer

wedgiees

wedgieing

wedgiely

wedgies

weeded

weeder

weedes

weeding

weedly

weeds

weenie

weenieed

weenieer

weeniees

weenieing

weeniely

weenies

weewee

weeweeed

weeweeer

weeweees

weeweeing

weeweely

weewees

weiner

weinered

weinerer

weineres

weinering

weinerly

weiners

weirdo

weirdoed

weirdoer

weirdoes

weirdoing

weirdoly

weirdos

wench

wenched

wencher

wenches

wenching

wenchly

wenchs

wetback

wetbacked

wetbacker

wetbackes

wetbacking

wetbackly

wetbacks

whitey

whiteyed

whiteyer

whiteyes

whiteying

whiteyly

whiteys

whiz

whized

whizer

whizes

whizing

whizly

whizs

whoralicious

whoralicioused

whoraliciouser

whoraliciouses

whoraliciousing

whoraliciously

whoraliciouss

whore

whorealicious

whorealicioused

whorealiciouser

whorealiciouses

whorealiciousing

whorealiciously

whorealiciouss

whored

whoreded

whoreder

whoredes

whoreding

whoredly

whoreds

whoreed

whoreer

whorees

whoreface

whorefaceed

whorefaceer

whorefacees

whorefaceing

whorefacely

whorefaces

whorehopper

whorehoppered

whorehopperer

whorehopperes

whorehoppering

whorehopperly

whorehoppers

whorehouse

whorehouseed

whorehouseer

whorehousees

whorehouseing

whorehousely

whorehouses

whoreing

whorely

whores

whoresed

whoreser

whoreses

whoresing

whoresly

whoress

whoring

whoringed

whoringer

whoringes

whoringing

whoringly

whorings

wigger

wiggered

wiggerer

wiggeres

wiggering

wiggerly

wiggers

woody

woodyed

woodyer

woodyes

woodying

woodyly

woodys

wop

woped

woper

wopes

woping

woply

wops

wtf

wtfed

wtfer

wtfes

wtfing

wtfly

wtfs

xxx

xxxed

xxxer

xxxes

xxxing

xxxly

xxxs

yeasty

yeastyed

yeastyer

yeastyes

yeastying

yeastyly

yeastys

yobbo

yobboed

yobboer

yobboes

yobboing

yobboly

yobbos

zoophile

zoophileed

zoophileer

zoophilees

zoophileing

zoophilely

zoophiles

anal

ass

ass lick

balls

ballsac

bisexual

bleach

causas

cheap

cost of miracles

cunt

display network stats

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gfc

humira AND expensive

illegal

madvocate

masturbation

nuccitelli

overdose

porn

shit

snort

texarkana

direct\-acting antivirals

assistance

ombitasvir

support path

harvoni

abbvie

direct-acting antivirals

paritaprevir

advocacy

ledipasvir

vpak

ritonavir with dasabuvir

program

gilead

greedy

financial

needy

fake-ovir

viekira pak

v pak

sofosbuvir

support

oasis

discount

dasabuvir

protest

ritonavir

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cleveland-clinic')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cleveland-clinic')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cleveland-clinic')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

A minimally invasive treatment for early GI cancers

The treatment of early esophageal, gastric, and colorectal cancer is changing.1 For many years, surgery was the mainstay of treatment for early-stage gastrointestinal cancer. Unfortunately, surgery leads to significant loss of function of the organ, resulting in increased morbidity and decreased quality of life.2

Endoscopic techniques, particularly endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), have been developed and are widely used in Japan, where gastrointestinal cancer is more common than in the West. This article reviews the indications, complications, and outcomes of ESD for early gastrointestinal neoplasms, so that readers will recognize the subset of patients who would benefit from ESD in a Western setting.

ENDOSCOPIC MUCOSAL RESECTION AND SUBMUCOSAL DISSECTION

Since the first therapeutic polypectomy was performed in Japan in 1974, several endoscopic techniques for tumor resection have been developed.3

EMR, one of the most successful and widely used techniques, involves elevating the lesion either with submucosal injection of a solution or with cap suction, and then removing it with a snare.4 Most lesions smaller than 20 mm can be removed in one piece (en bloc).5 Larger lesions are removed in multiple pieces (ie, piecemeal). Unfortunately, some fibrotic lesions, which are usually difficult to lift, cannot be completely removed by EMR.

ESD was first performed in the late 1990s with the aim of overcoming the limitations of EMR in resecting large or fibrotic tumors en bloc.6,7 Since then, ESD technique has been standardized and training centers have been created, especially in Asia, where it is widely used for treatment of early gastric cancer.3,8–10 Since 2012 it has been covered by the Japanese National Health Insurance for treatment of early gastric cancer, and since 2014 for treatment of colorectal malignant tumors measuring 2 to 5 cm.11

Adoption of ESD has been slow in Western countries, where many patients are still referred for surgery or undergo EMR for removal of superficial neoplasms. Reasons for this slow adoption are that gastric cancer is much less common in Western countries, and also that ESD demands a high level of technical skill, is difficult to learn, and is expensive.3,12,13 However, small groups of Western endoscopists have become interested and are advocating it, first studying it on their own and then training in a Japanese center and learning from experts performing the procedure.

Therefore, in a Western setting, ESD should be performed in specialized endoscopy centers and offered to selected patients.1

CANDIDATES SHOULD HAVE EARLY-STAGE, SUPERFICIAL TUMORS

Ideal candidates for endoscopic resection are patients who have early cancer with a negligible risk of lymph node metastasis, such as cancer limited to the mucosa (stage T1a).7 Therefore, to determine the best treatment for a patient with a newly diagnosed gastrointestinal neoplasm, it is mandatory to estimate the depth of invasion.

The depth of invasion is directly correlated with lymph node involvement, which is ultimately the main predictive factor for long-term adverse outcomes of gastrointestinal tumors.4,14–17 Accurate multidisciplinary preprocedure estimations are mandatory, as incorrect evaluations may result in inappropriate therapy and residual cancer.18

Other factors that have been used to predict lymph node involvement include tumor size, macroscopic appearance, histologic differentiation, and lymphatic and vascular involvement.19 Some of these factors can be assessed by special endoscopic techniques (chromoendoscopy and narrow-band imaging with magnifying endoscopy) that allow accurate real-time estimation of the depth of invasion of the lesion.5,17,20–27 Evaluation of microsurface and microvascular arrangements is especially useful for determining the feasibility of ESD in gastric tumors, evaluation of intracapillary loops is useful in esophageal lesions, and assessment of mucosal pit patterns is useful for colorectal lesions.21–29

Endoscopic ultrasonography is another tool that has been used to estimate the depth of the tumor. Although it can differentiate between definite intramucosal and definite submucosal invasive cancers, its ability to confirm minute submucosal invasion is limited. Its use as the sole tumor staging modality is not encouraged, and it should always be used in conjunction with endoscopic evaluation.18

Though the aforementioned factors help stratify patients, pathologic staging is the best predictor of lymph node metastasis. ESD provides adequate specimens for accurate pathologic evaluation, as it removes lesions en bloc.30

All patients found to have risk factors for lymph node metastasis on endoscopic, ultrasonographic, or pathologic analysis should be referred for surgical evaluation.9,19,31,32

ENDOSCOPIC SUBMUCOSAL DISSECTION

Before the procedure, the patient’s physicians need to do the following:

Determine the best type of intervention (EMR, ESD, ablation, surgery) for the specific lesion.3 A multidisciplinary approach is encouraged, with involvement of the internist, gastroenterologist, and surgeon.

Plan for anesthesia, additional consultations, pre- and postprocedural hospital admission, and need for special equipment.33

During the procedure

Define the lateral extent of the lesion using magnification chromoendoscopy or narrow-band imaging. In the stomach, a biopsy sample should be taken from the worst-looking segment and from normal-looking mucosa. Multiple biopsies should be avoided to prevent subsequent fibrosis.33 In the colon, biopsy should be avoided.34

Identify and circumferentially mark the target lesion. Cautery or argon plasma coagulation can be used for making markings at a distance of 5 to 10 mm from the edges.33 This is done to recognize the borders of the lesion, because they can become distorted after submucosal injection.14 This step is unnecessary in colorectal cases, as tumor margins can be adequately visualized after chromoendoscopy.16,35

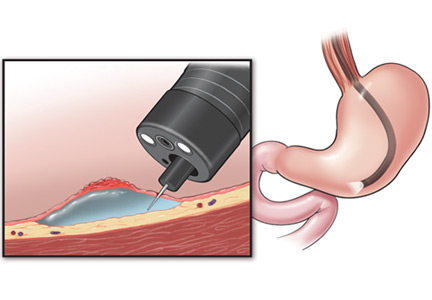

Lift the lesion by injecting saline, 0.5% hyaluronate, or glycerin to create a submucosal fluid cushion.19,33

Perform a circumferential incision lateral to the mucosal margins to allow for a normal tissue margin.33 Partial incision is performed for esophageal and colorectal ESD to avoid fluid leakage from the submucosal layer, achieving a sustained submucosal lift and safer dissection.16

Submucosal dissection. The submucosal layer is dissected with an electrocautery knife until the lesion is completely removed. Dissection should be done carefully to keep the submucosal plane.33 Hemoclips or hemostat forceps can be used to control visible bleeding. The resected specimen is then stretched and fixed to a board using small pins for further histopathologic evaluation.35

Postprocedural monitoring. All patients should be admitted for overnight observation. Those who undergo gastric ESD should receive high-dose acid suppression, and the next day they can be started on a liquid diet.19

STOMACH CANCER

Indications for ESD for stomach cancer in the East

The incidence of gastric cancer is higher in Japan and Korea, where widespread screening programs have led to early identification and early treatment of this disease.36

Pathology studies37 of samples from patients with gastric cancer identified the following as risk factors for lymph node metastasis, which would make ESD unsuitable:

- Undifferentiated type

- Tumors larger than 2 cm

- Lymphatic or venous involvement

- Submucosal invasion

- Ulcerative change.

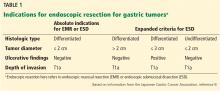

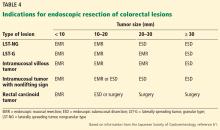

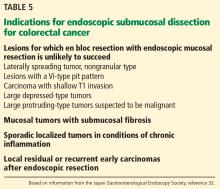

Based on these findings, the situations in which there was no risk of lymph node involvement (ie, when none of the above factors are present) were accepted as absolute indications for endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer.38 Further histologic studies identified a subset of patients with lesions with very low risk of lymph node metastasis, which outweighed the risk of surgery. Based on these findings, expanded criteria for gastric ESD were proposed,39,40 and the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines now include these expanded preoperative indications9,17 (Table 1).

The Japanese Gastric Cancer Association has proposed a treatment algorithm based on the histopathologic evaluation after resection (Figure 2).9

Outcomes

In the largest series of patients who underwent curative ESD for early gastric cancer, the 5-year survival rate was 92.6%, the 5-year disease-specific survival rate was 99.9%, and the 5-year relative survival rate was 105%.41

Similarly, in a Japanese population-based survival analysis, the relative 5-year survival rate for localized gastric cancer was 94.4%.42 Rates of en bloc resection and complete resection with ESD are higher than those with EMR, resulting in a lower risk of local recurrence in selected patients who undergo ESD.8,43,44

Although rare, local recurrence after curative gastric ESD has been reported.45 The annual incidence of local recurrence has been estimated to be 0.84%.46

ESD entails a shorter hospital stay and requires fewer resources than surgery, resulting in lower medical costs (Table 2).44 Additionally, as endoscopic resection is associated with less morbidity, fewer procedure-related adverse events, and fewer complications, ESD could be used as the standard treatment for early gastric cancer.47,48

The Western perspective on endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancer

Since the prevalence of gastric cancer in Western countries is significantly lower than in Japan and Korea, local data and experience are scarce. However, experts performing ESD in the West have adopted the indications of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends ESD for excision of most superficial gastric neoplasms, with EMR being preferred only in lesions smaller than 15 mm, Paris classification 0 or IIA.5,32

Patients with gastric lesions measuring 15 mm or larger should undergo high-quality endoscopy, preferably chromoendoscopy, to evaluate the mucosal patterns and determine the depth of invasion. If superficial involvement is confirmed, other imaging techniques are not routinely recommended.5 A surgery consult is also recommended.

ESOPHAGEAL CANCER

Indications for ESD for esophageal cancer in the East

Due to the success of ESD for early gastric cancer, this technique is now also used for superficial esophageal neoplasms.19,49 It should be done in a specialized center, as it is more technically difficult than gastric ESD: the esophageal lumen is narrow, the wall is thin, and the esophagus moves with respiration and heartbeat.50 A multidisciplinary approach including an endoscopist, a surgeon, and a pathologist is highly recommended for evaluation and treatment.

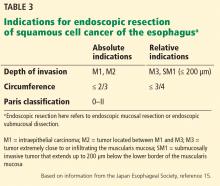

EMR is preferred for removal of mucosal cancer, in view of its safety profile and success rates. ESD can be considered in cases of lesions larger than 15 mm, poorly lifting tumors, and those with the possibility of submucosal invasion (Table 3).5,45,49,51

Circumference involvement is critical when determining eligible candidates, as a defect involving more than three-fourths of the esophageal circumference can lead to esophageal strictures.52 Controlled prospective studies have shown promising results from giving intralesional and oral steroids to prevent stricture after ESD, which could potentially overcome this size limitation.53,54

Outcomes for esophageal cancer

ESD has been shown to be safe and effective, achieving en bloc resection in 85% to 100% of patients.19,51 Its advantages over EMR include en bloc resection, complete resection, and high curative rates, resulting in higher recurrence-free survival.2,55,56 Although the incidence of complications such as bleeding, perforation, and stricture formation are higher with ESD, patients usually recover uneventfully.2,19,20

ESD in the esophagus: The Western perspective

As data on the efficacy of EMR vs ESD for the treatment of Barrett esophagus with adenocarcinoma are limited, EMR is the gold standard endoscopic technique for removal of visible esophageal dysplastic lesions.5,51,57 ESD can be considered for tumors larger than 15 mm, for poorly lifting lesions, and if there is suspicion of submucosal invasion.5